Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs) are classically immunologically cold tumors that have failed to demonstrate a significant response to immunotherapeutic strategies. This feature is attributed to both the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) and limited immune cell access due to the surrounding stromal barrier, a histological hallmark of PDACs. In this issue of the JCI, Sharma et al. employ a broad glutamine antagonist, 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON), to target a metabolic program that underlies both PDAC growth and hyaluronan production. Their findings describe an approach to converting the PDAC TME into a hot TME, thereby empowering immunotherapeutic strategies such as anti-PD1 therapy.

The tumor microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas

Immunotherapy has changed the treatment paradigm for a number of previously deadly cancers, including metastatic non–small cell lung cancers and melanomas. However, current immunotherapies have had little success against other cancers, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs). PDACs are stereotypically known to be “immunologically cold” tumors, in which the presence of immune cells and their activity are limited by the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). The relative lack of effector T cells in the pancreatic TME is largely attributed to the presence of a barrier, termed stromal desmoplasia, surrounding the PDAC cells. Importantly, this histopathological hallmark of PDACs can also serve as a potential therapeutic target toward enhancing both drug delivery and immune responses.

Hyaluronan, a nonsulphated glycosaminoglycan in the extracellular matrix, is secreted by PDAC cells (1), and its high deposition within the pancreatic TME is associated with poor prognosis (2). Efforts to target hyaluronan directly, however, have been met with mixed responses. Mouse model studies have shown that enzymatic degradation of hyaluronan by administering a pegylated human recombinant PH20 hyaluronidase (PEGPH20) improves intratumoral vascularity and, subsequently, drug delivery and efficacy (3, 4). While one early phase clinical trial showed that adding PEGPH20 to gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel (one standard of care regimen for PDAC) improves responses to therapy (5), another showed that combining PEGPH20 with FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy (the other standard of care for PDAC) is less effective than chemotherapy alone (6). These observations indicate the complexity of targeting the stroma, consistent with its known role in restraining PDAC growth (7, 8).

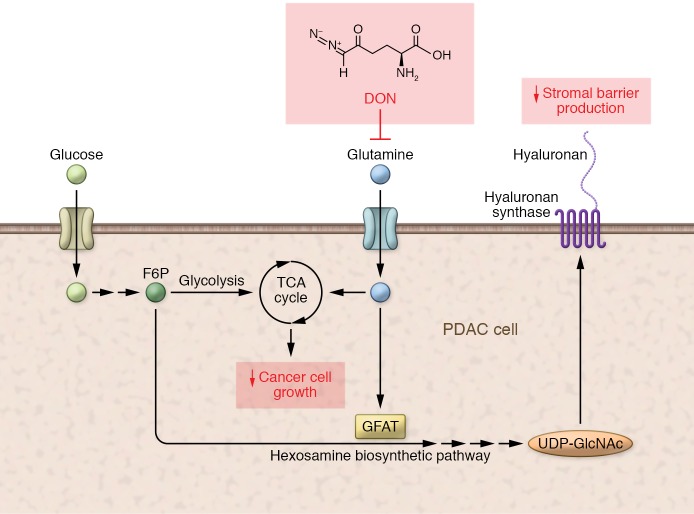

In this issue of the JCI, Sharma et al. took an alternative approach to targeting the stroma and instead targeted a metabolic underpinning shared by both hyaluronan synthesis and pancreatic cell growth. Based on the well-studied role of glutamine as a key input substrate for glycolysis and hyaluronan synthesis, the authors targeted cancer cells via the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP). Sharma et al. utilized a broad glutamine antagonist, 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON), to test their hypothesis that targeting this point of metabolic convergence would yield augmented antitumor effects against PDACs (ref. 9 and Figure 1).

Figure 1. Targeting a point of convergence in metabolic pathways in PDAC.

Glutamine is involved as a substrate for the anaerobic metabolic processes whereby the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle uses glucose to enable effective PDAC cell growth. Glutamine is also a substrate for the rate-limiting enzyme GFAT, which is part of the HBP that acts via uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) and leads to hyaluronan synthesis. Thus, glutamine antagonism with DON may reduce both cancer growth and stromal barrier production.

Therapeutic effects of glutamine antagonism in PDAC models

Sharma and colleagues used mouse models of chronic pancreatitis (caerulein induced) and PDAC (Kras-Tp53 driven, KPC mice), and human pancreatic cancer samples from a deidentified tissue microarray and The Cancer Genome Atlas, to confirm that markers relevant to the HBP were highly represented in PDAC cells. The authors then inhibited the HBP rate-limiting enzyme glutamine fructose-6 phosphate (F6P) amidotransferase 1 (GFAT1) with siRNA in human PDAC cell lines. Notably, self-renewal gene expression and clonogenicity decreased. Furthermore, treatment of KPCs with DON led to reduced viability, invasiveness, and migration potential. Consistent with these in vitro findings, in vivo treatment of xenograft and KPC-fibroblast coimplanted orthotopic syngeneic mouse models with DON led to significantly decreased tumor growth, Ki67 positivity, and metastatic spread. The authors then observed that the antitumor effects of DON were indeed associated with features of active extracellular matrix remodeling, including decreased hyaluronan and collagen I, changes in metalloproteases, lower IL-27 in KPC mice, lower IL-6, and higher IFN-γ production by fibroblasts. Thus, the authors rigorously demonstrated the therapeutic utility of DON through multiple models (9).

Importantly, Sharma et al. investigated the effects of DON on the immune TME. They employed both single-stain immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry to demonstrate DON-associated tumor infiltrating CD68+ monocytes and CD8+ T cells. They also evaluated survival and tumor volume in the orthotopic mouse model using both wild-type and CD8-knockout mice and showed that the antitumor effects conferred by DON are dependent on CD8+ T cells. However, caution should be taken in interpreting DON’s effects on the immune TME, especially within the CD68+ population, due to the lack of subtyping of these cells and analysis of their functional states in this study. The authors then further interrogated the immune-activating effects of DON by testing the in vivo response of KPC tumors to anti-PD1 therapy. It is well known that both human and KPC PDACs fail to respond to anti-PD1 therapy alone. Surprisingly, this study showed that DON induces susceptibility to anti-PD1 therapy, generating superior efficacy in combination over monotherapy (9).

Translational implications and future considerations

This study by Sharma et al. provides a number of new insights into the PDAC TME. First, it highlights a metabolic program that can be pharmacologically inhibited to disrupt tumor proliferation, metastasis, and stromal composition. Second, it implies that glutamine antagonism can in fact induce a marked change in the antitumor immunologic response, effectively converting the “cold” into a “hot” TME, and can elicit significant responses to anti-PD1 therapy (9). The immunologic phenomenon is particularly intriguing, since leveraging the immune system to treat PDACs remains a difficult task. Similar to what Sharma et al. observed, another recent study has shown that breaking down the stromal barrier with PEGPH20 is associated with increased memory T cell infiltration and improved survival when combined with a GM-CSF–secreting pancreatic tumor vaccine (10). Thus, these observations provide important proof of concept and excite possible translational efforts.

To realize the translatability of the authors’ findings, there are at least two major caveats to address: targeting a physiologically relevant pathway and developing a viable drug. As studies recognize, the tumor-restraining function of the stroma is an important therapeutic target. Thus, targeting a signaling pathway responsible for both carcinogenesis and stromal barrier functions is theoretically attractive. In fact, this approach has previously been investigated in the form of Hedgehog inhibitors. However, despite the well-established role of aberrantly activated Hedgehog signaling in pancreatic carcinogenesis (11) and stromal development (12) and despite the successful preclinical assessment of Hedgehog inhibition approaches (13), clinical trials have failed to demonstrate benefit (14). This example suggests that predicting the clinical outcome is difficult when perturbing a pathway involved in carcinogenesis and stromal barrier functions as well as in stromal development for normal physiologic benefit. Another critical question is whether a clinically applicable glutamine antagonist could be developed. While the authors discuss DON as the candidate drug for future trials, prior trials with DON have been challenged by significant toxicities (15); the rate of mucositis, which is a highly morbid adverse effect, was greater than 80% in multiple trials when used at low daily dosing with which efficacy was observed. Thus, alternative formulations or candidate drugs must be explored. For example, the use of DON prodrugs with more preferable tissue distribution and therapeutic index has recently been proposed (15).

In summary, this study by Sharma et al. demonstrates the therapeutic effect of DON on suppressing PDAC growth that occurs through the attraction of CD8+ T cells into the TME (9). Concurrent anti-PD1 therapy may further activate these T cells. Thus, these results suggest the unique opportunity to convert PDACs from a cold to a hot immunological state. Finally, future drug development and translational efforts to target this “integrated metabolic node” will be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

WJH is the recipient of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award and an American Association of Cancer Research Incyte Immuno-Oncology Research Fellowship.

Version 1. 12/03/2019

Electronic publication

Version 2. 01/02/2020

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: EMJ receives research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Aduro Biotech, is on the advisory board for Genocea Biosciences, and has the potential to receive royalties from Aduro Biotech.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(1):71–73. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI133685.

See the related article at Targeting tumor-intrinsic hexosamine biosynthesis sensitizes pancreatic cancer to anti-PD1 therapy.

Contributor Information

Won Jin Ho, Email: who10@jhmi.edu.

Elizabeth M. Jaffee, Email: ejaffee@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Mahlbacher V, Sewing A, Elsässer HP, Kern HF. Hyaluronan is a secretory product of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;58(1):28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whatcott CJ, et al. Desmoplasia in primary tumors and metastatic lesions of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(15):3561–3568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobetz MA, et al. Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62(1):112–120. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingorani SR, et al. HALO 202: randomized phase II study of PEGPH20 plus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine versus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine in patients with untreated, metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):359–366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramanathan RK, et al. Phase IB/II randomized study of FOLFIRINOX plus pegylated recombinant human hyaluronidase versus FOLFIRINOX alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: SWOG S1313. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(13):1062–1069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhim AD, et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):735–747. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JJ, et al. Stromal response to Hedgehog signaling restrains pancreatic cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(30):E3091–E3100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411679111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma NS, et al. Targeting tumor-intrinsic hexosamine biosynthesis sensitizes pancreatic cancer to anti-PD1 therapy. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(1):451–465. doi: 10.1172/JCI127515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair AB, et al. Dissecting the stromal signaling and regulation of myeloid cells and memory effector T cells in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(17):5351–5363. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thayer SP, et al. Hedgehog is an early and late mediator of pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Nature. 2003;425(6960):851–856. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey JM, et al. Sonic hedgehog promotes desmoplasia in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(19):5995–6004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldmann G, et al. Blockade of hedgehog signaling inhibits pancreatic cancer invasion and metastases: a new paradigm for combination therapy in solid cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67(5):2187–2196. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Jesus-Acosta A, et al. A phase II study of vismodegib, a hedgehog (Hh) pathway inhibitor, combined with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) in patients (pts) with untreated metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(3_suppl):257. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.3_suppl.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemberg KM, Vornov JJ, Rais R, Slusher BS. We’re not “DON” yet: optimal dosing and prodrug delivery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(9):1824–1832. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]