Abstract

The solar wind is a magnetized plasma and as such exhibits collective plasma behavior associated with its characteristic spatial and temporal scales. The characteristic length scales include the size of the heliosphere, the collisional mean free paths of all species, their inertial lengths, their gyration radii, and their Debye lengths. The characteristic timescales include the expansion time, the collision times, and the periods associated with gyration, waves, and oscillations. We review the past and present research into the multi-scale nature of the solar wind based on in-situ spacecraft measurements and plasma theory. We emphasize that couplings of processes across scales are important for the global dynamics and thermodynamics of the solar wind. We describe methods to measure in-situ properties of particles and fields. We then discuss the role of expansion effects, non-equilibrium distribution functions, collisions, waves, turbulence, and kinetic microinstabilities for the multi-scale plasma evolution.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s41116-019-0021-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Solar wind, Spacecraft measurements, Coulomb collisions, Plasma waves and turbulence, Kinetic instabilities

Introduction

The solar wind is a continuous magnetized plasma outflow that emanates from the solar corona. This extension of the Sun’s outer atmosphere propagates through interplanetary space. Its existence was first conjectured based on its interaction with planetary bodies in the solar system. Although the connection between solar activity and disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic field had been established in the nineteenth century (Sabine 1851, 1852; Hodgson 1859; Stewart 1861), the connection of these events with “corpuscular radiation” was not made until the early twentieth century (Birkeland 1914; Chapman 1917). The arguably first appearance of the notion of a continuous “swarm of ions proceeding from the Sun” in the literature dates back to a footnote by Eddington (1910) as an explanation for the observed shape of cometary tails. Later, Hoffmeister (1943) summarized multiple comet observations and suggested that some form of solar corpuscular radiation is responsible for the observed lag of comet ion tails with respect to the heliocentric radius vector (for the link between solar activity and comet tails, see also Ahnert 1943). Biermann (1951) revisited the relation between comet tails and solar corpuscular radiation by quantifying the momentum transfer from the solar wind to cometary ions. He especially noted that the solar radiation pressure is insufficient to explain the observed structures (Milne 1926) and that the corpuscular radiation is more variable than the electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun. The origin of the solar corpuscular radiation, however, remained unclear until Parker (1958) showed that a hot solar corona cannot maintain a hydrostatic equilibrium. Instead, the pressure-gradient force overcomes gravity and leads to a radial acceleration of the coronal plasma to supersonic velocities, which Parker called “solar wind” in contrast to a subsonic “solar breeze” (Chamberlain 1961), which was later found to be unstable (Velli 1994). Soon after this prediction, the solar wind was measured in situ by spacecraft (Gringauz et al. 1960; Neugebauer and Snyder 1962). For the last four decades, the solar wind has been monitored almost continuously in situ. Parker’s underlying concept is the mainstream paradigm for the acceleration of the solar wind, but many questions remain unresolved. For example, we still have not identified the mechanisms that heat the solar corona to temperatures orders of magnitude higher than the photospheric temperature, albeit this discovery was made some 80 years ago (Grotrian 1939; Edlén 1943). As we discuss the observed features of the solar wind in this review, we will encounter further deficiencies in our understanding that require more detailed analyses beyond Parker’s model. In this process, we will find many observational facts that models of coronal heating and solar-wind acceleration must explain in order to achieve a realistic and consistent description of the physics of the solar wind.

In the first section of this review, we lay out the various characteristic length and timescales in the solar wind and motivate our thesis that this multi-scale nature defines the evolution of the solar wind. We then introduce the observed large-scale, global features and the microphysical, kinetic features of the solar wind as well as the mathematical basis to describe the related processes.

The characteristic scales in the solar wind

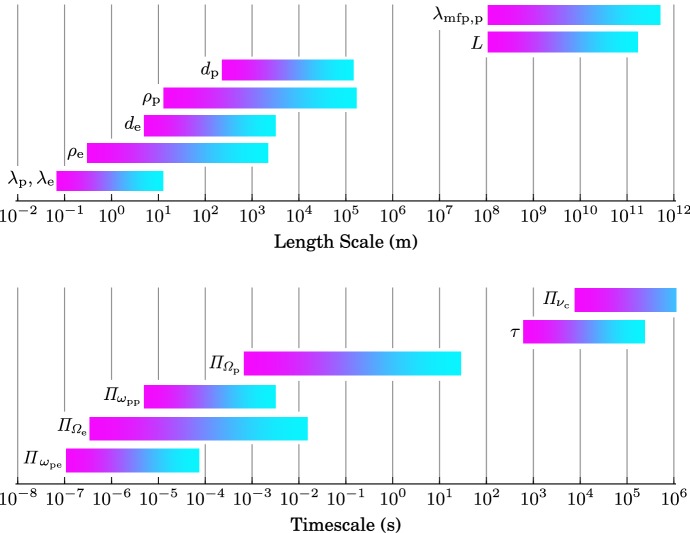

Table 1 lists typical values for the characteristic plasma parameters and scales in the solar wind at 1 au and in the upper solar corona that we introduce and define in this section. It is important to remember that all of these quantities vary widely in time and may differ significantly between thermal and superthermal particle populations. We illustrate the broad range of the characteristic length scales and timescales in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

The multiple characteristic plasma parameters (top), length scales (middle), and timescales (bottom) in the solar wind

| Symbol | Solar wind | (Upper) Corona | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| , | Proton and electron number density | ||

| , | Proton and electron temperature | ||

| B | 1 G | Magnetic field strength | |

| 3 au | 100 Mm | Proton collisional mean free path | |

| L | 1 au | 100 Mm | Characteristic size of the system |

| 140 km | 230 m | Proton inertial length | |

| 160 km | 13 m | Proton gyration radius | |

| 3 km | 5 m | Electron inertial length | |

| 2 km | 30 cm | Electron gyration radius | |

| , | 12 m | 7 cm | Proton and electron Debye lengths |

| 120 d | 2 h | Proton collision time | |

| 2.4 d | 10 min | Expansion time | |

| 26 s | Proton gyration period | ||

| Proton plasma period | |||

| 14 ms | 360 ns | Electron gyration period | |

| 110 ns | Electron plasma period |

This table shows typical parameters in the solar wind at 1 au and in the upper solar corona ( 100 Mm above photosphere). For each angular frequency , the associated timescale is given by

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the characteristic length scales (top) and timescales (bottom) in the solar wind. The bar lengths represent the typical range for each scale given in Table 1. The magenta end of each bar indicates the typical coronal value, and the cyan end of each bar indicates the typical value at 1 au

The solar wind expands to a heliocentric distance of about 90 au, where it transitions to a subsonic flow by crossing the solar-wind termination shock (Stone et al. 2005; Burlaga et al. 2008). Although we do not expound upon the physics of the outer heliosphere and the interaction of the solar wind with the interstellar medium, this is the largest spatial scale in the supersonic solar wind. Considering the inner heliosphere (i.e., the spherical volume centered around the Sun within Earth’s orbit), we identify the characteristic size of the system as . For a typical radial solar-wind flow speed in the range of 300 km/s to 800 km/s (Lopez and Freeman 1986), we find an expansion time of

| 1 |

for the solar wind from the Sun to 1 au. The Sun’s siderial rotation period at its equator,

| 2 |

introduces another characteristic global timescale.

In addition to the outer size of the system, a plasma has multiple characteristic scales due to the interactions of its free charges with electric and magnetic fields. In a homogeneous and constant magnetic field , a plasma particle with charge and mass (where j denotes the particle species) experiences a continuous deflection of its trajectory due to the Lorentz force. The frequency associated with this helical motion is given by the gyro-frequency1 (also called the cyclotron frequency)

| 3 |

where c is the speed of light in vacuum. The timescale for one closed loop around the magnetic field is then given by the gyro-period . In the solar wind at 1 au, and , where the index represents protons and the index represents electrons. On the other hand, in the upper corona (about 100 Mm above the photosphere), where the magnetic field is much stronger than in the solar wind, and . Aside from protons, -particles (i.e., fully ionized helium atoms) are also dynamically important in the solar wind since they account for of the mass density.

We define the perpendicular thermal speed as

| 4 |

and the parallel thermal speed as

| 5 |

where () is the temperature of particle species j in the direction perpendicular (parallel) to and is the Boltzmann constant. We define the concept of temperatures perpendicular and parallel to in Eqs. (38) and (39). Assuming a thermal distribution of particles with a perpendicular thermal speed , the characteristic size of the gyration orbit is given by the gyro-radius

| 6 |

At 1 au, solar-wind gyro-radii are typically and . In the upper corona, the gyro-radii are smaller: and .

The plasma frequency

| 7 |

where is the background number density of species j, corresponds to the characteristic timescale for electrostatic interactions in the plasma: . In the solar wind at 1 au, and . These timescales are even shorter in the corona: and . A reduction of the local electron number density (e.g., through a spatial displacement of a number of electrons with respect to the ions) leads to an oscillation of the electrons with respect to the ions, in which the electrostatic force due to the displaced charge serves as the restoring force. This plasma oscillation occurs with a frequency . In addition, light waves cannot propagate at frequencies in a plasma as the free plasma charges shield the wave’s electromagnetic fields so that the wave amplitude drops off exponentially with distance when the wave frequency is . The exponential decay length associated with this shielding is given by the skin-depth .

More generally, we define the skin-depth (also called the inertial length) of species j as

| 8 |

where

| 9 |

is the Alfvén speed of species j. In the solar wind at 1 au, and . In the upper corona, on the other hand, and . In processes that occur on length scales greater than and timescales greater than , protons exhibit a magnetized behavior, which means that their trajectory is closely tied to the magnetic field lines, following a quasi-helical gyration pattern with the frequency given in Eq. (3). Likewise, electrons exhibit magnetized behavior in processes that occur on length scales greater than and timescales greater than .

An important length scale associated with electrostatic effects is the Debye length

| 10 |

where is the (scalar, isotropic) temperature of species j. We note that through much of the heliosphere, which makes the Debye length unique among the scales we discuss. The total Debye length

| 11 |

is the characteristic exponential decay length for a time-independent global electrostatic potential in a plasma. In the solar wind at 1 au, , while the plasma in the upper corona exhibits . Collective plasma processes (i.e., particles behaving as if they only interact with a smooth macroscopic electromagnetic field rather than with individual moving charges) become important if the number of particles within a sphere of radius is large,

| 12 |

and if

| 13 |

Equations (12) and (13) guarantee that electrostatic single-particle effects are shielded by neighboring charges from the surrounding plasma (known as Debye shielding). If one or both of these conditions are not fulfilled, common plasma-physics methods do not apply and a material is merely an ionized gas rather than a plasma. The solar wind, however, satisfies both of these conditions and, therefore, is a plasma.

In addition to these collective plasma length scales and timescales, collisional effects are associated with their own characteristic scales, which depend on the type of collisional interaction under consideration (e.g., temperature equilibration or isotropization) and on different combinations of plasma parameters. We discuss these effects and the associated timescales in Sect. 3.

Comparing the coronal electron Debye length as the smallest plasma length scale of the solar wind with the size of the system reveals that the solar wind covers over twelve orders of magnitude in its characteristic length scales (neglecting length scales associated with collisions, which can be even greater than L). Similarly, comparing the corona’s electron plasma period with the solar wind’s expansion time reveals that the solar wind also covers over twelve orders of magnitude in its characteristic timescales (again neglecting timescales associated with collisions, which can be even greater than ). These ratios demonstrate the intrinsically multi-scale nature of the solar wind. The broad range of scales also illustrates the difficulty in treating the solar wind and all related physics processes numerically since complete numerical simulations would need to resolve this entire range of scales.

This review describes plasma processes that depend upon or modify the multi-scale nature of the solar wind. As a truly Living Review, its first edition is limited to small-scale processes that affect the large-scale evolution of the plasma. In a later major update, we will describe how large-scale processes affect the small-scale structure of the plasma such as expansion effects on particle properties, wave reflection and the creation of turbulence, streaming interactions, mixing from different solar sources in co-rotating interaction regions, and magnetic focusing effects, as well as the impact of these processes on global solar-wind modeling. Although every plasma process is conceivably a multi-scale process, we, by practical necessity, only address the physics processes we consider most relevant to the multi-scale evolution of the solar wind. The most prominent processes not covered in this review include detailed discussions of reconnection (Pontin 2011; Gosling 2012; Paschmann et al. 2013), shock waves (Balogh et al. 1995; Chashei and Shishov 1997; Lepping 2000; Rice and Zank 2003), the physics of the outer heliosphere (pick-up ions, energetic neutral atoms, etc., Zank et al. 1995; Gloeckler and Geiss 1998; Zank 1999; Richardson et al. 2004; McComas et al. 2012; Zank et al. 2018), interplanetary dust (Krüger et al. 2007; Mann et al. 2010), interactions with planetary bodies (Grard et al. 1991; Kivelson and Bagenal 2007; Gardini et al. 2011; Bagenal 2013), eruptive events such as coronal mass ejections (Zurbuchen and Richardson 2006; Howard and Tappin 2009; Webb and Howard 2012), solar energetic particles (Ryan et al. 2000; Mikić and Lee 2006; Klein and Dalla 2017), and (anomalous) cosmic rays (Heber et al. 2006; Potgieter 2008; Giacalone et al. 2012; Potgieter 2013). We also limit our discussion of minor-ion physics.

Global structure of the solar wind

At heliocentric distances greater than a few solar radii , the solar wind’s expansion is, to first order, radial, which creates large-scale radial gradients in most of the plasma parameters. For this discussion of the global structure, we concentrate only on long-term averages of the plasma quantities and neglect their frequent—and, as we will see later, sometimes comparable to order unity—variations. Figure 2 illustrates these average quantities as functions of distance in the inner heliosphere and demonstrates the resulting profiles for the characteristic length scales and timescales. Beyond a distance of about , the average radial velocity stays approximately constant. Continuity under steady-state conditions requires that

| 14 |

where is the bulk velocity of species j. In spherical coordinates and under the assumption that , the average density then decreases . In the acceleration region and in regions of super-radial expansion connected to coronal holes, continuity requires steeper gradients closer to the Sun as confirmed by white-light polarization measurements (Cranmer and van Ballegooijen 2005). In addition, the deceleration of streaming -particles leads to a small deviation from the density profile (Verscharen et al. 2015).

Fig. 2.

Characteristic average quantities, length scales, and timescales as functions of distance from the Sun in the inner heliosphere for typical fast-solar-wind conditions. We calculate these scales based on typical radial profiles of the solar-wind magnetic-field strength, density, and velocity (shown in the top panel). The profiles for the magnetic field and the density are taken from Smith et al. (2012) for a radial polar flux tube. The radial velocity profile then follows from flux conservation, . The electron temperature is taken from a fit to measurements at (Cranmer et al. 1999) and then connected to a power-law with a power index corresponding to the radial temperature profiles observed with Helios in the fast solar wind (Štverák et al. 2015). We take for simplicity

To first order, the average magnetic field follows the Parker spiral in the plane of the ecliptic (Parker 1958; Levy 1976; Behannon 1978; Mariani et al. 1978, 1979) as a result of the frozen-in condition of ideal magnetohydrodynamics (MHD; see Sect. 1.4.2) and the rotation of the Sun. We define

| 15 |

where B is the magnetic field, as the ratio between the thermal pressure of species j and the magnetic pressure. In the solar corona, , so that the magnetic field constraints the plasma to co-rotate with the Sun. However, the magnetic field’s torque on the plasma decreases with distance from the Sun until the plasma outflow dominates the evolution of the magnetic field and convects the field into interplanetary space (Weber and Davis 1967). In the Parker model, the Parker angle between the direction of the magnetic field and the radial direction increases with distance r from the Sun,

| 16 |

where and are the azimuthal and radial components of the magnetic field, is the angular speed of the Sun’s rotation, is the polar angle, and is the effective co-rotation radius. In our sign and coordinate convention, if since the Sun rotates in the -direction, which differs from Parker’s (1958) original choice. The radius is an auxiliary quantity to describe the heliospheric distance beyond which the solar wind behaves as if it were co-rotating for (Hollweg and Lee 1989). Observations indicate that in the fast wind and in the slow wind (Bruno and Bavassano 1997). The Parker angle increases from at to about at . This trend continues into the outer heliosphere as shown by observations (Thomas and Smith 1980; Forsyth et al. 2002). The magnitude of the Parker field decreases with distance as

| 17 |

which is in the limit at small r and in the limit at large r. We note that the original Parker model is not completely torque-free, although a torque-free treatment leads to only minor modifications (Verscharen et al. 2015). Further details about the heliospheric magnetic field can be found in the review by Owens and Forsyth (2013).

Categorization of solar wind

Traditionally, the solar wind has been categorized into three groups (Srivastava and Schwenn 2000):

fast wind with bulk velocities between about 500 km/s and 800 km/s,

slow wind with bulk velocities between about 300 km/s and 500 km/s, and

variable/eruptive events such as coronal mass ejections with speeds from a few hundreds up to 2000 km/s.

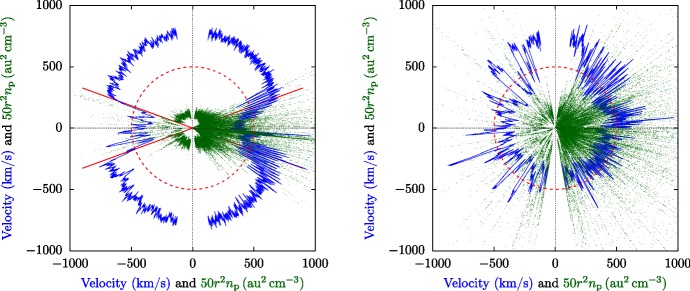

Measurements from the Ulysses spacecraft during solar minimum dramatically demonstrate that the fast wind emerges predominantly from polar coronal holes and the slow wind from the streamer belt at the solar equator (Phillips et al. 1995; McComas et al. 1998b, 2000, 2003; Ebert et al. 2009). The left-hand panel in Fig. 3 illustrates the clear sector boundary between fast and slow wind during solar minimum. During solar maximum, however, fast and slow wind emerge from neighboring patches everywhere in the corona. The right-hand panel in Fig. 3 shows that the occurrence of fast and slow wind streams does not strongly correlate with heliographic latitude during solar maximum. On average, fast polar wind exhibits both a lower density and less variation in density than slow wind. The association of different wind streams with different source regions suggests that the magnetic-field configuration in the corona plays a crucial role in determining the properties of the wind streams. In addition to the differences in speed and density, fast and slow wind exhibit further distinguishing marks. Fast wind, relative to slow wind, generally is more steady, is more Alfvénic (i.e., it exhibits a higher correlation or anti-correlation between fluctuations in vector velocity and vector magnetic field; see Sect. 4 and Tu and Marsch 1995), and has a higher proton temperature (Neugebauer 1976; Wilson et al. 2018). Importantly for its multi-scale evolution, fast wind is also less collisional (both in terms of the local collisional relaxation times and the cumulative time for collisions to act) than slow wind (Marsch et al. 1982b; Marsch and Goldstein 1983; Livi et al. 1986; Kasper et al. 2008; Bourouaine et al. 2011; Ďurovcová et al. 2017), which allows for more kinetic non-equilibrium features to survive the thermalizing action of Coulomb collisions. Fast wind, therefore, exhibits more non-Maxwellian structure in its distribution functions (Marsch 2006, 2018) as we discuss in the next section.

Fig. 3.

Ulysses/SWOOP observations of the solar-wind proton radial velocity and density at different heliographic latitudes. The distance from the center in each of these polar plots indicates the velocity (blue) and density (green). The polar angle represents the heliographic latitude. Since these measurements were taken at varying distances from the Sun, we compensate for the density’s radial decrease by multiplying with . The red circle represents and . The straight red lines indicate the sector boundaries at latitude. Left panel: Ulysses’ first polar orbit during solar minimum (1990-12-20 through 1997-12-15). Right panel: Ulysses’ second polar orbit during solar maximum (1997-12-15 through 2004-02-22). After McComas et al. (2000) and McComas et al. (2008)

The elemental composition and the heavy-ion charge states also differ between fast and slow wind (Bame et al. 1975; Ogilvie and Coplan 1995; von Steiger et al. 1995; Bochsler 2000; von Steiger et al. 2000; Aellig et al. 2001b; Zurbuchen et al. 2002; Kasper et al. 2007, 2012; Lepri et al. 2013). Elements with a low first ionization potential (FIP) such as magnesium, silicon, and iron exhibit enhanced abundances in the solar corona and in the solar wind with respect to their photospheric abundances (Gloeckler and Geiss 1989; Raymond 1999; Laming 2015). Conversely, elements with a high FIP such as oxygen, neon, and helium have much lower enhancements or even depletions with respect to their photospheric abundances. This FIP fractionation bias also varies with wind speed and is generally smaller in fast wind than in slow wind (Zurbuchen et al. 1999; Bochsler 2007). Since the elemental composition of a plasma parcel does not change as it propagates through the heliosphere unless it mixes with neighboring parcels, composition measurements are a reliable method to distinguish solar-wind source regions. Moreover, studies of heavy ions constrain proposed models of solar-wind acceleration and heating. For instance, proposed acceleration and heating scenarios must explain the observed preferential heating of minor ions. In the solar wind, most heavy ion species i exhibit (Tracy et al. 2015; Heidrich-Meisner et al. 2016; Tracy et al. 2016).

Lately, the traditional classification of wind streams by speed has experienced some major criticism (e.g., Maruca et al. 2013; Xu and Borovsky 2015; Camporeale et al. 2017). Speed alone does not fully classify the properties of the wind, and there is a smooth transition in the distribution of wind speeds. At times, fast solar wind shows properties traditionally associated with slow wind and vice versa, such as collisionality, Alfvénicity, FIP-bias, anisotropy, beam structures, etc. Although these atypical behaviors suggest a false dichotomy between fast and slow wind, we retain the traditional nomenclature, albeit defining “fast wind” as wind with the typical fast-wind properties and “slow wind” as wind with the typical slow-wind properties under consideration instead of relying on the flow speeds alone. Nevertheless, we expressly caution the reader against assuming wind speed alone as a reasonable indication of wind type.

Kinetic properties of the solar wind

Kinetic plasma physics describes the statistical properties of a plasma by means of the particle velocity distribution functions for each plasma species j. We define and normalize the distribution function so that

| 18 |

represents the number of particles of species j in the phase-space volume centered on the phase-space coordinates at time t. The distribution function relates to the bulk properties (i.e., density, bulk velocity, temperature,...) through its velocity moments as described in Sect. 1.4.1. A continuous definition of is appropriate when Eq. (12) is fulfilled.

The central equation in kinetic physics is the Boltzmann equation,

| 19 |

where is the acceleration of a j-particle due to macroscopic forces, and the right-hand side describes the temporal change in due to particle collisions, which are mediated by microscopic electric forces among individual particles (see also Sect. 3.2 of this review; Lifshitz and Pitaevskii 1981). We use the term macroscopic fields to indicate that these are locally averaged to remove the rapidly fluctuating Coulomb electric fields due to individual charges, which are responsible for Coulomb collisions. The applicability of this mean-field approach is a key quality of a plasma and distinguishes it from other types of ionized gases, in which Eq. (12) is not fulfilled. Without the collision term, the Boltzmann equation represents a fluid continuity equation for the density in phase space. It is thus related to Liouville’s theorem and describes the conservation of the phase-space density along trajectories in the absence of collisions.2 In this case, and when using only macroscopic electromagnetic forces in the acceleration term, we obtain the Vlasov equation,

| 20 |

which is the fundamental equation of collisionless kinetic plasma physics. These macroscopic electric and magnetic fields obey Maxwell’s equations,

| 21 |

| 22 |

| 23 |

and

| 24 |

where the charge density and the current density are given by integrals over the distribution functions as

| 25 |

and

| 26 |

Equations (20) through (26) form a closed set of integro-differential equations in six-dimensional phase space and time that fully describe the evolution of collisionless plasma.

Fluid moments and fluid equations

Although the distribution functions contain all of the microphysical properties of the plasma, it is often sufficient to rely on a reduced set of macrophysical parameters that only depend on time and three-dimensional configuration space (versus time and six-dimensional phase space). These parameters are called bulk parameters and correspond to the velocity moments as integrals over the full velocity space of the distribution function. Certain velocity moments represent named fluid bulk parameters. For instance, the zeroth velocity moment corresponds to the number density

| 27 |

Using , the first velocity moment corresponds to the bulk velocity

| 28 |

while the second moment represents the pressure tensor

| 29 |

The third moment corresponds to the heat-flux tensor

| 30 |

For many applications in magnetized-plasma physics, it is useful to choose the coordinate system to be aligned with the direction of the magnetic field and to define the pressure components with respect to the direction of the magnetic field. In this coordinate system, Equation (30) reduces through contraction to the perpendicular heat-flux vector

| 31 |

and the parallel heat-flux vector

| 32 |

where is the three-dimensional unit matrix. We define the double-dot and triple-dot products in a similar way to the usual dot product as

| 33 |

Although higher moments do not give rise to named bulk parameters like these four, the moment hierarchy can be continued to infinity by multiplying the integrand with further powers of velocity.

Taking velocity moments of the full Vlasov equation and exploiting the definitions of the lowest moments above leads to the multi-fluid plasma equations (Barakat and Schunk 1982; Marsch 2006). The zeroth and first moments of the Vlasov equation are the continuity equation,

| 34 |

and the momentum equation,

| 35 |

We define the perpendicular pressure and the parallel pressure as

| 36 |

and

| 37 |

respectively, which are related to the temperatures in the directions perpendicular and parallel to through

| 38 |

and

| 39 |

We write the perpendicular energy equation as

| 40 |

and the parallel energy equation as

| 41 |

where

| 42 |

is the stress tensor,

| 43 |

The hierarchy of moments of the Vlasov equation continues to infinity, and similar fluid equations exist for the stress tensor, the heat-flux tensor, and all higher-order moments. However, this gives rise to a closure problem since the nth moment of the Vlasov equation always includes the st moment of the distribution function. For example, the continuity equation, which is the zeroth moment of the Vlasov equation, includes the bulk velocity, which corresponds to the first moment of . The st moment of the distribution function, in turn, requires the st moment of the Vlasov equation as a description of its dynamical evolution. Every fluid model is, therefore, fundamentally susceptible to a closure problem since the solution of an infinite chain of non-degenerate equations is formally impossible. For most practical purposes, the moment hierarchy is thus truncated by expressing a higher-order moment of through lower moments of only. Closing the moment hierarchy introduces limitations on the physics of the problem at hand and deviations in the solutions to the multi-fluid system of equations from the solutions to the full Vlasov equation. For example, a typical closure of the moment hierarchy is the assumption of an isotropic and adiabatic pressure, i.e., and , where is the adiabatic exponent. This closure of the momentum equation neglects heat flux and small velocity-space structure in . Therefore, any finite closure is only applicable if the physics of the problem at hand justifies the neglect of higher-order velocity moments of . We note, for example, that collisions are such a process that can produce conditions under which higher-order moments are negligible (see Sect. 3).

Assuming only slow changes of the magnetic field compared to and that , the second velocity moment of the Vlasov equation (20) leads to the useful double-adiabatic energy equations (Chew et al. 1956; Whang 1971; Sharma et al. 2006; Chandran et al. 2011),

| 44 |

and

| 45 |

If we neglect heat flux by setting the right-hand sides of Eqs. (44) and (45) to zero, we obtain the conservation laws for the double-adiabatic invariants, which are also referred to as the Chew–Goldberger–Low (CGL) invariants (Chew et al. 1956)

| 46 |

Magnetohydrodynamics

Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) is a single-fluid description that results from summing the fluid equations of all species and defining the moments of the single magnetofluid as the mass density

| 47 |

the bulk velocity

| 48 |

and the total scalar pressure

| 49 |

under the assumption that is isotropic and diagonal. This procedure leads to the MHD continuity equation,

| 50 |

and the MHD momentum equation,

| 51 |

The electric-field term from Eq. (35) vanishes under the quasi-neutrality assumption that from Eq. (25) is negligible, which is justified on scales . Faraday’s law describes the evolution of the magnetic field as

| 52 |

The electric field follows from the electron momentum equation (35) as the generalized Ohm’s law,

| 53 |

where

| 54 |

is the ion contribution to the current density. The terms on the right-hand side of Eq. (53) represent the contributions from electron inertia, the electron pressure gradient (i.e., the ambipolar electric field), the Hall term, and the ion convection term, respectively. Under the assumptions of quasi-neutrality in a proton–electron plasma and the negligibility of terms of order , we find

| 55 |

If we furthermore assume small or moderate and consider processes occurring on scales (Chiuderi and Velli 2015), we can neglect the contributions of the electron pressure gradient and the Hall term to . We then find the common expression for Ohm’s law in MHD:

| 56 |

Equations (52) and (56) describe Alfvén’s frozen-in theorem, stating that magnetofluid bulk motion across field lines is forbidden, since otherwise the infinite resistivity of the magnetofluid would lead to infinite eddy currents. Instead, the magnetic flux through a co-moving surface is conserved.3 The assumptions leading to Eq. (56) are fulfilled for processes on time scales much greater than and as well as on spatial scales much greater than and . In this limit, the displacement current in Ampère’s law is also negligible, which allows us to write the current density in Eq. (51) in terms of the magnetic field:

| 57 |

The MHD equations are often closed with the adiabatic closure relation,

| 58 |

where is the adiabatic exponent. The MHD equations are intrinsically scale-free and, therefore, only valid for processes that do not occur on any of the characteristic plasma scales of the system introduced in Sect. 1.1. Thus, MHD only applies to large-scale phenomena that occur

on length scales ,

on length scales , and

on timescales

for all j.

Standard distributions in solar-wind physics

Although solar-wind measurements often reveal irregular plasma distribution functions (see Sects. 1.4.4, 1.4.5, as well as Marsch 2012), it is sometimes helpful to invoke closed analytical expressions for the distribution functions in a plasma. In the following description, we use the cylindrical coordinate system in velocity space introduced in Sect. 1.4.1 with its symmetry axis to be parallel to .

A gas in thermodynamic equilibrium has a Maxwellian velocity distribution,

| 59 |

where

| 60 |

is the (isotropic) thermal speed of species j. Equation (59) has a thermodynamic justification in equilibrium statistical mechanics based on the Gibbs distribution (Landau and Lifshitz 1969). An empirically motivated extension of the Maxwellian distribution is the so-called bi-Maxwellian distribution, which introduces temperature anisotropies with respect to the background magnetic field yet follows the Maxwellian behavior on any one-dimensional cut at constant or constant in velocity space:

| 61 |

where and are the thermal speeds defined in Eqs. (4) and (5). Advanced methods in thermodynamics such as non-extensive statistical mechanics lead to the -distribution (Tsallis 1988; Livadiotis and McComas 2013; Livadiotis 2017),

| 62 |

where is the -function (Abramowitz and Stegun 1972) and . We note that for . The -distribution is characterized by having tails that are more pronounced for smaller (i.e., the kurtosis of the distribution increases as decreases). Analogous to the bi-Maxwellian is the bi--distribution,

| 63 |

In the following sections, we will encounter observed distribution functions and recognize some of the uses and limitations of these analytical expressions.

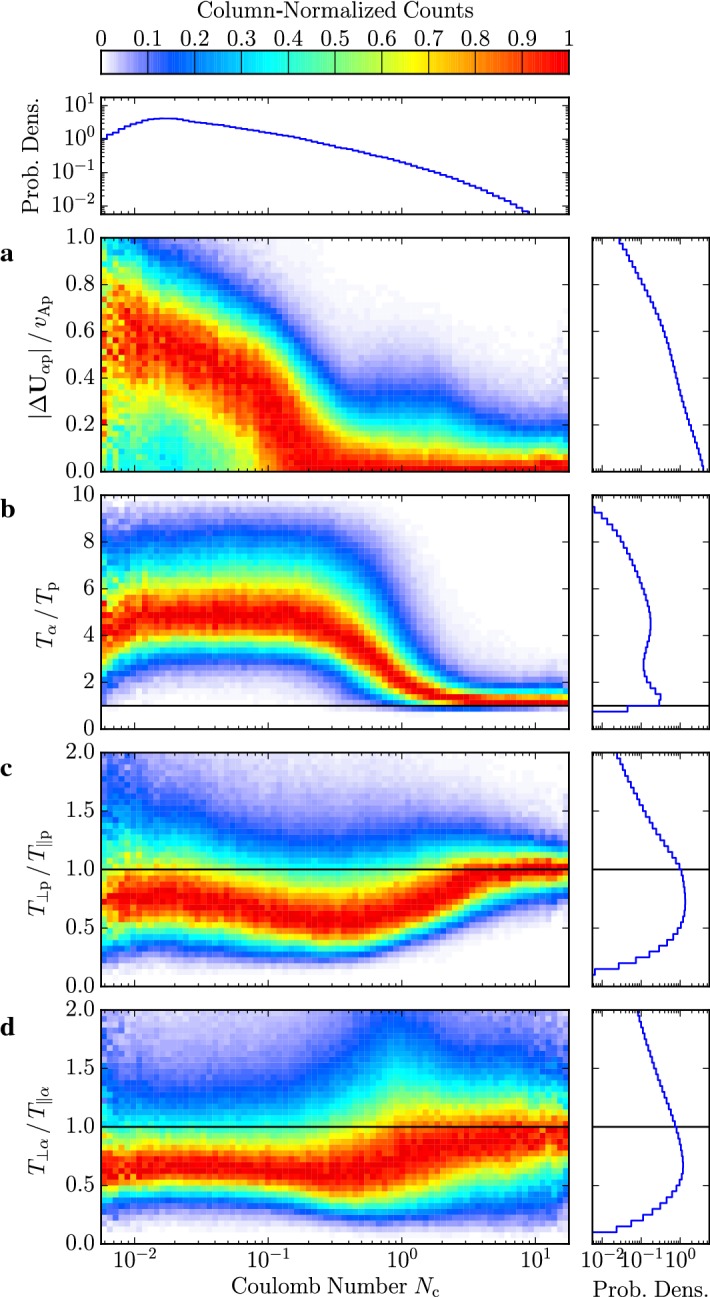

Ion properties

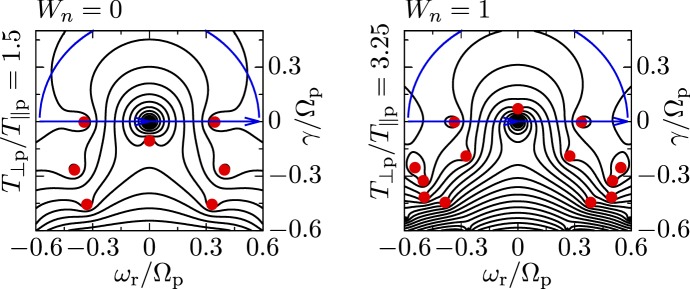

In-situ spacecraft instrumentation has been measuring ion and electron velocity distributions for decades (see Sect. 2.2). Figure 4 summarizes some of the observed features in ion and electron distribution functions schematically.

Fig. 4.

Illustration of ion (left) and electron (right) kinetic features in the solar wind. We show cuts through the distribution function along the direction of the magnetic field. We normalize the distribution functions to the maxima of the proton and electron distribution functions, respectively. We normalize the parallel velocity to the thermal speed of the proton and electron core components, and , respectively. We note that . The gray curves show the underlying core distribution alone. The distributions are shown in the reference frames in which the core distribution is at rest

These observations show that proton distributions often deviate from the Maxwellian equilibrium distribution given by Eq. (59). For instance, proton distributions often display a field-aligned beam: a second proton component streaming faster than the proton core component along the direction of the magnetic field with a relative speed (Asbridge et al. 1974; Feldman et al. 1974b; Marsch et al. 1982b; Goldstein et al. 2000; Tu et al. 2004; Alterman et al. 2018). In Fig. 4 (left), the proton beam is shown in green as an extension of the distribution function toward greater . Protons also show temperature anisotropies with respect to the magnetic field (Hundhausen et al. 1967a, b; Marsch et al. 1981; Kasper et al. 2002; Marsch et al. 2004; Hellinger et al. 2006; Bale et al. 2009; Maruca et al. 2012), which manifest in unequal diagonal elements of in Eq. (29). Figure 5 shows isosurfaces of based on measurements from the Helios spacecraft. The background magnetic field is vertically aligned, and the color-coding represents the distance of the isosurfaces from the center-of-mass velocity. A standard Maxwellian distribution would be a monochromatic sphere in these diagrams. Instead, we see that the proton distribution is anisotropic. The example on the left-hand side shows an extension of the isosurface along the magnetic-field direction, which indicates the proton-beam component. Almost always, the proton beam is directed away from the Sun and along the magnetic-field axis.4 This observation suggests that the beam represents a preferentially accelerated proton component. The existence of this beam thus puts a major observational constraint on potential mechanisms for solar-wind heating and acceleration, which must generate this almost ubiquitous feature in . In the example on the right-hand side of Fig. 5, the isosurface is spread out in the directions perpendicular to the magnetic field, which indicates that . Although the plasma also exhibits periods with , the predominance of cases with in the fast wind in the inner heliosphere (Matteini et al. 2007) suggests an ongoing heating mechanism in the solar wind that counter-acts the double-adiabatic expansion quantified in Eqs. (44) and (45). The double-adiabatic expansion alone would create in the inner heliosphere when we neglect the action of heat flux and collisions on protons. Therefore, only heating mechanisms that explain the observed anisotropies with in the solar wind (and possibly also in the corona; see Kohl et al. 2006) are successful candidates for a complete description of the physics of the solar wind.

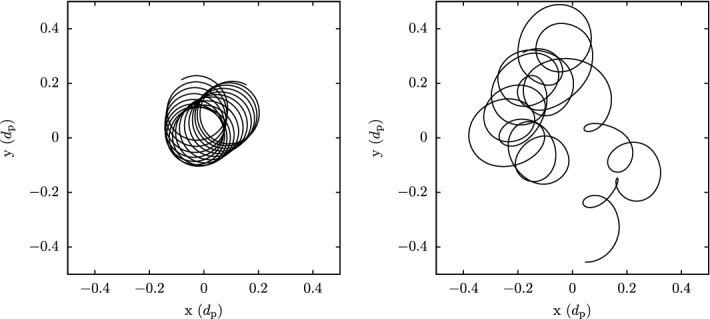

Fig. 5.

Interpolated isosurfaces in velocity space of two proton distribution functions measured by Helios 2. The arrow indicates the direction of the local magnetic field. The color-coding represents the distance of the isosurface from the center-of-mass velocity. Left: measurement from 1976-02-04 at 10:21:43 UTC. The center-of-mass velocity is 478 km/s. The elongation along the magnetic-field direction represents the proton beam. Right: measurement from 1976-04-16 at 07:50:54 UTC. The center-of-mass velocity is 768 km/s. The oblate structure of the distribution function represents a temperature anisotropy with . These distribution functions are available as animations in the online supplementary material

The colors on the isosurfaces in Fig. 5 illustrate that the bulk velocity of the proton distribution function differs significantly from the center-of-mass velocity. This is mostly due to the -particles in the solar wind (Ogilvie 1975; Asbridge et al. 1976; Marsch et al. 1982a; Neugebauer et al. 1994, 1996; Steinberg et al. 1996; Reisenfeld et al. 2001; Berger et al. 2011; Gershman et al. 2012; Bourouaine et al. 2013). Although their number density is small (), their mass density corresponds to about 20% of the proton mass density. We often observe the -particles, like the proton beam, to drift with respect to the proton core along the magnetic-field direction and away from the Sun with a typical drift speed . In Fig. 4 (left), the -particles are shown as a separate shifted distribution in red, centered around the -particle drift speed.

The solar wind also exhibits anisothermal behavior; i.e., not all plasma species have equal temperatures (Formisano et al. 1970; Feldman et al. 1974a; Bochsler et al. 1985; Cohen et al. 1996; von Steiger and Zurbuchen 2002, 2006). The -particles often show (Kasper et al. 2007, 2008, 2012). Electrons are typically colder than protons in the fast solar wind but hotter than protons in the slow solar wind (Montgomery et al. 1968; Hundhausen 1970; Newbury et al. 1998). As stated in Sect. 1.2, heavy-ion-to-proton temperature ratios are typically greater than the corresponding heavy-ion-to-proton mass ratios for almost all observable ions in the solar wind. Like the other kinetic features, solar-wind heating and acceleration models are only fully successful if they explain the observed anisothermal behavior.

All of these non-equilibrium features (temperature anisotropies, beams, drifts, and anisothermal behavior) are less pronounced in the slow solar wind than in the fast wind, which is typically attributed to the greater collisional relaxation rates and the longer expansion times in the slow wind (see Sect. 3.3). These non-equilibrium features reflect the multi-scale nature of the solar wind, since they are driven by a combination of large-scale expansion effects, local kinetic processes, and the feedback of small-scale processes on the large-scale evolution.

Electron properties

Although the mass of an electron is much less than the mass of a proton (), and the electrons’ contribution to the total solar-wind momentum flux is insignificant, electrons do affect the large-scale evolution of the solar wind (Montgomery 1972; Salem et al. 2003). As the most abundant particle species, they guarantee quasi-neutrality: and at length scales and timescales . Due to their small mass, they are highly mobile and have a much greater thermal speed than the protons, leading to their subsonic behavior (i.e., ). Their momentum balance in Eq. (35) is dominated by their pressure gradient and electromagnetic forces. Through these contributions, the electrons create an ambipolar electrostatic field in the expanding solar wind. This field is the central underlying acceleration mechanism of exospheric models (see Sect. 3.1; Lemaire and Scherer 1973; Maksimovic et al. 2001). Parker’s (1958) solar-wind model does not explicitly invoke an ambipolar electrostatic field. Nevertheless, the electron contribution to the pressure gradient in Parker’s MHD equation of motion is equivalent to the ambipolar electric field that follows from Eq. (35) for electrons in the limit (Velli 1994, 2001).

Although electrons typically have greater collisional relaxation rates than ions, they exhibit a number of characteristic kinetic non-equilibrium features, which, as for the ions, are more pronounced in the fast solar wind. Most notably, the electron distribution often consists of three distinct components (Feldman et al. 1975; Pilipp et al. 1987a, b; Hammond et al. 1996; Maksimovic et al. 1997; Fitzenreiter et al. 1998):

a thermal core, which mostly follows a Maxwellian distribution and has a thermal energy of —blue in Fig. 4 (right);

a non-thermal halo, which mostly follows a -distribution, manifests as enhanced high-energy tails in the electron distribution, and has a thermal energy of —green in Fig. 4 (right); and

a strahl,5 which is a field-aligned beam of electrons and usually travels in the anti-Sunward direction with a bulk energy —red in Fig. 4 (right).

The core typically includes of the electrons. It sometimes displays a temperature anisotropy (Serbu 1972; Phillips et al. 1989b; Štverák et al. 2008) and a relative drift with respect to the center-of-mass frame (Bale et al. 2013). A recent study suggests that a bi-self-similar distribution, which forms through inelastic particle scattering, potentially describes the core distribution better than a bi-Maxwellian distribution (Wilson et al. 2019).

The strahl probably results from a more isotropic distribution of superthermal electrons in the corona that has been focused by the mirror force in the nascent solar wind (Owens et al. 2008), explaining the anti-Sunward bulk velocity of the strahl in the solar-wind rest frame. As with the ion beams, a Sunward or bi-directional electron strahl can occur when the magnetic-field configuration changes during the plasma’s passage from the Sun (Gosling et al. 1987; Owens et al. 2017). Figure 6 shows an example of an electron velocity distribution function measured in the solar wind. This distribution exhibits a significant strahl at but shows no clear halo component. We reiterate our paradigm that all successful solar-wind acceleration and heating scenarios must account for the observed kinetic structure of the solar wind, including these features in the electron distributions. At highest energies , a nearly isotropic superhalo of electrons exists; however, its number density is very small compared to the densities of the other electron species ( at 1 au), and its origin remains poorly understood (Lin 1998; Wang et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2015; Tao et al. 2016).

Fig. 6.

Electron velocity distribution function measured by Helios 2 in the fast solar wind at a heliocentric distance of on 1976-04-18 at 23:38:35 UTC. Left: isocontours of the distribution in a field-aligned coordinate system. Right: a cut through the distribution function along the magnetic-field direction. The red dashed curve shows a Maxwellian fit to the core of the distribution function. The strahl is clearly visible as an enhancement in the distribution function at

Observations of the superthermal electrons (i.e., strahl and halo) reveal that remains largely constant with heliocentric distance, where is the strahl density and is the halo density. Conversely, decreases with distance from the Sun while increases (Maksimovic et al. 2005; Štverák et al. 2009; Graham et al. 2017). Various processes have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, most of which involve the scattering of strahl electrons into the halo (Vocks et al. 2005; Gary and Saito 2007; Pagel et al. 2007; Saito and Gary 2007; Owens et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2012; Gurgiolo et al. 2012; Landi et al. 2012; Verscharen et al. 2019a).

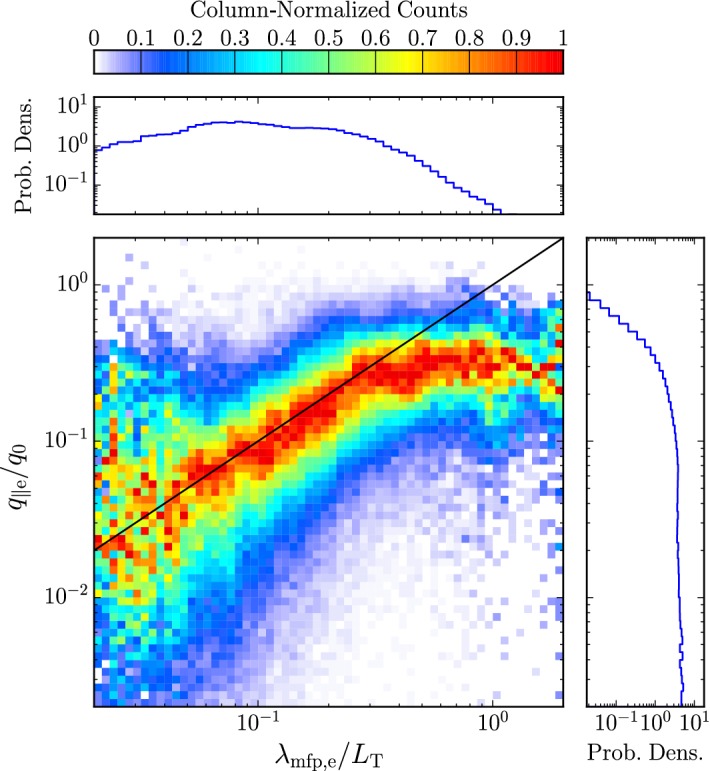

Locally, electrons often show isothermal behavior (i.e., having a polytropic index of one) due to their large field-parallel mobility. Globally, their non-thermal distribution functions carry a large heat flux according to Eq. (30) into the heliosphere (Feldman et al. 1976; Scime et al. 1995). Observations of large-scale electron temperature profiles suggest that the electron heat flux, rather than local heating, dominates their temperature evolution (Pilipp et al. 1990; Štverák et al. 2015). These energetic considerations also reveal that a combination of processes regulate the heat flux of the distribution. Collisions and collective kinetic processes such as microinstabilities are the prime candidates for explaining electron heat-flux regulation (see Sects. 3.3.2, 6.1.2; Scime et al. 1994, 1999, 2001; Bale et al. 2013; Lacombe et al. 2014).

Open questions and problems

The major outstanding science questions in solar-wind physics require a detailed understanding of the interplay between the multi-scale nature and the observed kinetic features of the solar wind. This theme applies to the coronal and solar-wind heating problem as well as the overall energetics of the inner heliosphere. We remind ourselves that any answer to the heating problem must be consistent with multiple detailed observational constraints as we have seen in the previous sections.

The observed temperature profiles and overall particle energetics of ions and electrons are consequences of the complex interactions of global heat flux, Coulomb collisions (Sect. 3), local wave action (Sect. 4), turbulent heating (Sect. 5), microinstabilities (Sect. 6), and double-adiabatic expansion (Mihalov and Wolfe 1978; Feldman et al. 1979; Gazis and Lazarus 1982; Marsch et al. 1983, 1989; Pilipp et al. 1990; McComas et al. 1992; Gazis et al. 1994; Issautier et al. 1998; Maksimovic et al. 2000; Matteini et al. 2007; Cranmer et al. 2009; Hellinger et al. 2011; Le Chat et al. 2011; Hellinger et al. 2013; Štverák et al. 2015). We still lack a detailed physics-based understanding of the majority of these processes, and the quantification of these processes and their role for the overall energetics of the solar wind remains one of the most outstanding science problems in space research.

Observed temperature profiles (including anisotropies) are some of the central messengers about the overall solar-wind energetics, apart from velocity profiles. Figure 7 illustrates the radial evolution of the proton and electron temperatures in the directions perpendicular and parallel to the magnetic field and separated by fast and slow wind. We also show the expected temperature profiles under the assumption that the evolution follows the double-adiabatic (CGL) expansion according to Eqs. (44) and (45) only. All of the measured temperature profiles deviate from the CGL profiles to some degree, and this trend continues at greater heliocentric distances (Cranmer et al. 2009). Explaining these deviations lies at the heart of the challenge to explain coronal and solar-wind heating and acceleration.

Fig. 7.

Temperature profiles in the inner heliosphere for fast (left) and slow (right) wind. We show radial power-law fits to proton-temperature measurements separated by fast () and slow () solar-wind conditions from Hellinger et al. (2013). Likewise, we show radial power-law fits to electron-temperature measurements separated by fast () and slow () solar-wind conditions from Štverák et al. (2015). The thin-dashed lines indicate the CGL temperature profiles according to Eqs. (44) and (45), where we set the right-hand sides of both equations to zero and determine the magnetic field through Eqs. (16) and (17) using , , , and

We intend this review to give an overview over the relevant multi-scale processes in the solar wind. In the near future, data from the Parker Solar Probe (Fox et al. 2016) and Solar Orbiter (Müller et al. 2013) spacecraft will provide us with detailed observations of the local and global properties of the solar wind at different distances from the Sun. These groundbreaking observations will help us to quantify the roles of the multi-scale processes described in this review.

Section 2 describes the methods to measure solar-wind particles and fields in situ. In Sect. 3, we discuss the effects of collisions on the multi-scale evolution of the solar wind. Section 4 introduces waves, and Sect. 5 introduces turbulence as mechanisms that affect the local and global plasma behavior. We describe the role of kinetic microinstabilities and parametric instabilities in Sect. 6. In Sect. 7, we summarize this review and consider future developments in the study of the multi-scale evolution of the solar wind.

In-situ observations of space plasmas

Observations of space plasmas can be roughly divided into two categories: remote and in-situ. Remote observations include both measurements of the plasma’s own emissions (e.g., radio waves, visible light, and X-ray photons) as well as measurements of the effects that the plasma has on emissions from other sources (e.g., Faraday rotation and absorption lines). In this way, regions such as the chromosphere that are inaccessible to spacecraft can still be studied. Additionally, imaging instruments such as coronagraphs provide information on the global structure of space plasma. Nevertheless, due to limited spectral and angular resolution, these instruments cannot provide information on all of the small-scale processes at work within the plasma. Remote observations also only offer limited information on three-dimensional phenomena. If the observed plasma is optically thick (e.g., the photosphere in visible light), its interior cannot be probed; if it is optically thin (e.g., the corona in EUV), remote observations suffer from the effects of line-of-sight integration.

In contrast, in-situ observations provide detailed information on microkinetic processes in space plasmas. Spacecraft carry in-situ instruments into the plasma to directly detect its particles and fields and thereby to provide small-scale observations of localized phenomena. Although an in-situ instrument only detects the plasma in its immediate vicinity, statistical studies of ensembles of measurements have provided remarkable insights into how small-scale processes affect the plasma’s large-scale evolution.

This section briefly overviews both the capabilities and the limitations of instruments used to observe the solar wind in situ. Although a full treatment of the subject is beyond the scope of this review, a basic understanding of these instruments is essential for the proper scientific analysis of their measurements. Section 2.1 highlights some significant heliospheric missions. Two sections are dedicated to in-situ observations of thermal ions and electrons: Sect. 2.2 overviews the instrumentation, and Sect. 2.3 addresses the analysis of particle data. Sections 2.4 and 2.5 respectively discuss the in-situ observation of the solar wind’s magnetic and electric fields. Section 2.6 presents a short description of multi-spacecraft techniques.

Overview of in-situ solar-wind missions

In-situ plasma instruments were among the first to be flown on spacecraft. Gringauz et al. (1960) used data from Luna 1, Luna 2, and Luna 3, which at the the time were known as the Cosmic Rockets, to report the first detection of super-sonic solar-wind ions as predicted by Parker (1958). These observations were soon confirmed by Neugebauer and Snyder (1962), who used in-situ measurements from Mariner 2 en route to Venus.

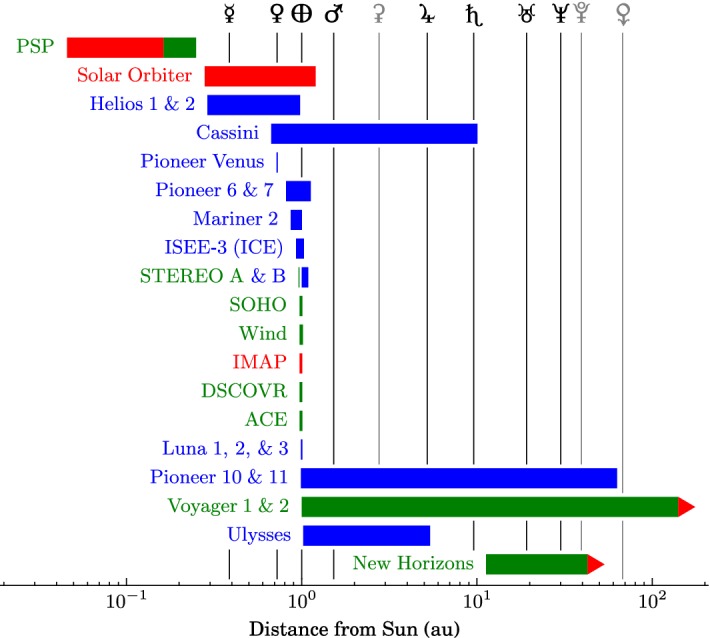

Since then, numerous spacecraft have carried in-situ instruments throughout the heliosphere to observe the solar wind’s particles and fields. Table 2 lists a selection of these missions grouped as completed, active, and future missions. The column “Radial Coverage” lists the ranges of heliocentric distance for which in-situ data are available, which are presented graphically in Fig. 8. Currently, Voyager 1 (Kohlhase and Penzo 1977) is the most distant spacecraft from the Sun—a superlative that it will continue to hold for the foreseeable future. Helios 2 (Porsche 1977) held for several decades the record for closest approach to the Sun, but, in late 2018, Parker Solar Probe (Fox et al. 2016) achieved a substantially closer perihelion.

Table 2.

Select heliospheric missions: completed, active, and future

| Mission | Years active | Radial coverage (au) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luna 1, 2, and 3 | 1959–1959 | 1.0 | NSSDC; Johnson (1979) |

| Mariner 2 | 1962–1962 | 0.866–1.003 | COHOWeb |

| Pioneer 6 | 1965–1971 | 0.814–0.984 | COHOWeb |

| Pioneer 7 | 1966–1968 | 1.010–1.126 | COHOWeb |

| Pioneer 10 | 1972–1995 | 0.99–63.04 | CDAWeb (PIONEER10_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Pioneer 11 | 1973–1992 | 1.00–36.26 | CDAWeb (PIONEER11_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Pioneer Venus | 1978–1992 | 0.72–0.73 | CDAWeb (PIONEERVENUS_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| ISEE-3 (ICE) | 1978–1990 | 0.93–1.03 | CDAWeb (ISEE-3_MAG_1MIN_MAGNETIC_FIELD) |

| Helios 1 | 1974–1981 | 0.31–0.98 | CDAWeb (HELIOS1_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Helios 2 | 1976–1980 | 0.29–0.98 | CDAWeb (HELIOS2_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Ulysses | 1990–2009 | 1.02–5.41 | CDAWeb (UY_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Cassini | 1997–2017 | 0.67–10.07 | COHOWeb; OMNIWeb Plus (helio1day) |

| STEREO B | 2006–2014 | 1.00–1.09 | CDAWeb (STB_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Voyager 1 | 1977– | 1.01–140.71 | CDAWeb (VOYAGER1_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Voyager 2 | 1977– | 1.00–118.91 | CDAWeb (VOYAGER2_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| Wind | 1994– | 0.972–1.017 | CDAWeb (WI_OR_PRE) |

| SOHO | 1995– | 0.972–1.011 | CDAWeb (SO_OR_PRE) |

| ACE | 1997– | 0.973–1.010 | CDAWeb (AC_OR_SSC) |

| New Horizons | 2006– | 11.268–42.775 | CDAWeb (NEW_HORIZONS_SWAP_VALIDSUM) |

| STEREO A | 2006– | 0.96–0.97 | CDAWeb (STA_COHO1HR_MERGED_MAG_PLASMA) |

| DSCOVR | 2015– | 0.973–1.007 | CDAWeb (DSCOVR_ORBIT_PRE) |

| PSP | 2018– | 0.0459–0.25 | Fox et al. (2016) |

| Solar Orbiter | 2020 | 0.28–1.2 | Müller et al. (2013) |

| IMAP | 2024 | 0.973–1.007 | NASA Release 18-046 |

Year of launch to final year (with non-fill data) in cited dataset

Incomplete for some missions due to data gaps

Exact range not available

Distance still increasing; values on 2018-01-01 (Voyager 1), 2018-10-26 (Voyager 2), or 2018-10-31 (New Horizons)

Anticipated radial coverage

Perihelion of first three orbits: 0.163 au

Anticipated launch date

https://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Solar_Orbiter, accessed 2019-09-10

Approximate radial coverage of the first Lagrangian point of the Earth–Sun system

Fig. 8.

Radial coverage of select heliospheric missions based on Table 2. Colors indicate the status of each mission: completed (blue), active (green), and future (red). The colored bar for each mission does not reflect any data gaps that may be present in its dataset(s). Mixed coloring has been used for PSP to reflect that, while the mission is active, final radial coverage has not yet been achieved. Red arrows indicate that the radial coverages of Voyager 1 and 2 and New Horizons are still increasing. Vertical lines indicate the semi-major axes of the eight planets (black) and the dwarf planets Ceres, Pluto, and Eris (gray)

Thermal-particle instruments

Thermal particles constitute the most abundant but lowest-energy particles in solar-wind plasma. Although no formal definition exists, the term commonly refers to particles whose energies are within several (“a few”) thermal widths of the plasma’s bulk velocity. We define these as protons with energies and electrons with energies under typical solar-wind conditions at 1 au. We note, however, that most thermal-particle instruments cover a wider range of energies.

Although particle moments such as density, bulk velocity, and temperature are useful quantities for characterizing the plasma, these parameters generally cannot be measured directly. Instead, thermal-particle instruments measure particle spectra, which give the distribution of particle energies in various directions. These spectra must then be analyzed to derive values for the particle moments (see Sect. 2.3).

This section focuses on the basic design and operation of three types of thermal-particle instruments: Faraday cups, electrostatic analyzers (ESAs), and mass spectrometers. Since particle acceleration beyond thermal energies is outside of the scope of this review, we do not address instruments for measuring higher-energy particles.

Some other techniques and instruments exist for measuring thermal particles in solar-wind plasma, but we omit extensive discussion of these since they generally provide limited information about the phase-space structure of particle distributions. For example, an electric-field instrument can be used to infer some electron properties (especially density; see Sect. 2.5). Likewise Langmuir probes provide some electron moments (Mott-Smith and Langmuir 1926). A series of bias voltages is applied to a Langmuir probe relative either to the spacecraft or to another Langmuir probe. The electron density and temperature can then be inferred from measurements of current at each bias voltage. The Cassini spacecraft included a spherical Langmuir probe (Gurnett et al. 2004) along with other plasma instruments (Young et al. 2004).

Faraday cups

Faraday cups rank among the earliest instruments for studying space plasmas. Historically noteworthy examples include the charged-particle traps on Luna 1, Luna 2, and Luna 3 (Gringauz et al. 1960) and the Solar Plasma Experiment on Mariner 2 (Neugebauer and Snyder 1962), which provided the first in-situ observations of the solar wind’s supersonic ions. Since then, Faraday cups on Pioneer 6 and Pioneer 7 (Lazarus et al. 1966, 1968), Voyager 1 and 2 (Bridge et al. 1977), Wind (Ogilvie et al. 1995), and DSCOVR (Aellig et al. 2001a) have continued to observe solar-wind particles.

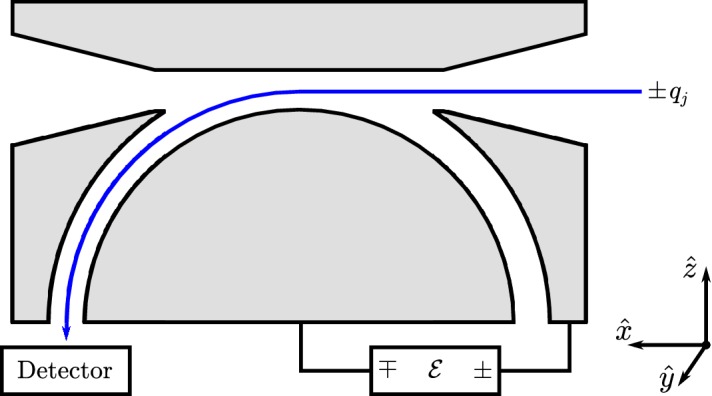

As depicted in Fig. 9, a Faraday cup consists of a grounded metal structure with an aperture. A typical Faraday cup has a somewhat “squat” geometry with a wide aperture so that it accepts incoming particles from a wide range of directions. For example, the full-width half-maximum field of view of each of the Wind/SWE Faraday cups is about . At the back of the cup is a metal collector plate, which receives the current I of the inflowing charged particles.

Fig. 9.

Simplified cross-sectional diagram of a Faraday cup for observing ions. The cup’s aperture is on the right, its collector plate is on the left, and its three grids are indicated by dashed lines. A square-wave voltage, , is applied to the middle grid, which is known as the modulator. Blue arrows indicate inflowing j-ions. Depending on , the normal component of the ion’s velocity, it is either always accepted by the modulator (high speed), always rejected (low speed), or only accepted when the modulator’s voltage is low (intermediate speed). The accepted ions produce a current at the collector plate, which the detection system amplifies, demodulates, and integrates to measure, in effect, the current from only the intermediate-speed ions according to Eq. (66)

Figure 9 shows three of the fine mess grids that are placed between a Faraday cup’s aperture and collector. The inner and outer grids are electrically grounded. A voltage is applied to the middle grid, known as the modulator, to restrict the ability of particles to reach the collector. We define to indicate the direction into the Faraday cup so that is the cup’s look direction. Consider a j-particle of mass and charge that enters the cup with a velocity . For a modulator voltage , the particle can only reach the collector if the normal component of its velocity, , is greater than the cutoff speed

| 64 |

When and have opposite signs, the modulator places no restriction on the particle’s ability to reach the collector.

Typically, the modulator is not kept at a constant voltage but rather alternated between two voltages:

| 65 |

where is the offset and is the peak-to-peak amplitude. In this configuration, the detector circuit is designed to use synchronous detection to measure the difference in the collector current between the two states:

| 66 |

Essentially, is the current from particles whose velocities are sufficient for them to reach the collector when the modulator voltage is low but not when it is high. This method suppresses contributions to the collector current that do not vary with the modulator voltage. These contributions include the signal from any particle species with a charge opposite that of the modulator since, per Eq. (64), the modulator does not restrict the inflow of such particles. This method also mitigates the effects of photoelectrons, which are liberated from the collector by solar UV photons and whose signal can exceed that of solar-wind particles by orders of magnitude (Bridge et al. 1960).

A set of and values defines a voltage window. By measuring the differential current for a series of these, a Faraday cup produces an energy distribution of solar-wind particles. The size and number of voltage windows determine the spectral resolution and range, which, for many Faraday cups, can be adjusted in flight to accommodate changing plasma conditions. Since a Faraday cup is simply measuring current, its detector electronics often exhibit little degradation with time. For example, Kasper et al. (2006) demonstrate that the absolute gain of each of the Wind/SWE Faraday cups (Ogilvie et al. 1995) drifts per decade.

Various approaches exist to use Faraday cups to measure the direction of inflowing particles, which is necessary for inferring parameters such as bulk velocity and temperature anisotropy. The Voyager/PLS investigation (Bridge et al. 1977) and the BMSW solar-wind monitor on SPECTR-R (Šafránková et al. 2008) include multiple Faraday cups pointed in different directions. DSCOVR/PlasMag (Aellig et al. 2001a) has only a single Faraday cup but multiple collector plates: a split collector. Each collector is off-axis from the aperture and thus has a slightly different field of view. Pioneer 6, Pioneer 7 (Lazarus et al. 1966, 1968), and Wind (Ogilvie et al. 1995) are spinning spacecraft, so their Faraday cups make measurements in various directions as the spacecraft rotate.

A Faraday cup’s response function is a mathematical model for what the instrument measures under different plasma conditions: i.e., an expression for as a function of the particle distribution functions. For simplicity, we initially consider only one particle species j and assume that the distribution function is, during the measurement cycle, a function of only. The number density of j-particles in a phase-space volume centered on is

| 67 |

The current that the Faraday cup measures from the particles in this volume is

| 68 |

where are the spherical coordinates of , and is the Faraday cup’s effective collecting area as a function of particle-inflow direction.6 If the modulator voltage spans the voltage window , then the contribution of all j-particles to the measured differential current is

| 69 |

Since a Faraday cup cannot distinguish current from different types of particles, the measured current is

| 70 |

where the sum is carried out over all particle species in the plasma.

Equations (69) and (70) provide the general form of the response function of a Faraday cup. Section 2.3 overviews the process of inverting the response function to determine the particle moments from a measured particle spectrum.

Electrostatic analyzers

Like Faraday cups, electrostatic analyzers (ESAs) have a long history of use in the observation of thermal particles in the solar wind. Though ESAs are substantially more complex than Faraday cups, they enable much more direct and detailed studies of distribution functions (see Sect. 2.3.1). Additionally, they can be combined with mass spectrometers (see Sect. 2.2.3) to directly probe the ion composition of the plasma.

Figure 10 shows a simplified cross-section of the common top-hat design for an ESA (Carlson et al. 1983). Such a device consists of two hemispherical shells that are nested concentrically so as to leave a narrow gap between them. Particles enter via a hole in the top of the larger hemisphere and are then subjected to the electric field that is created by maintaining a DC voltage between the two hemispheres. The value of and the curvature and spacing of the hemispheres define an energy-per-charge range for an incoming particle to reach the detectors at the base of the hemispheres. If an incoming particle has a kinetic energy K and charge , it can only reach the detectors if the ratio falls within that range. To generate a particle spectrum, is swept through a series of values. The range of particle energies is set by the range of values, which, on most ESAs, can be adjusted in flight. Nevertheless, the width of an ESA’s energy window is fixed geometrically by the spacing between its collimator plates. In contrast, the width of a Faraday cups’ energy window is adjustable in flight since it is set by a voltage range according to Eq. (65).

Fig. 10.

Simplified cross-sectional diagram of a top-hat style electrostatic analyzer (ESA). The aperture is shown on the upper left and right, and can provide up to of coverage of azimuth . In contrast, only particles within a limited range of elevation are able to pass through the curved collimator plates and reach the detector. A DC voltage is sustained between the plates and sets the sign and value of the target energy per charge for incoming particles. The spacing between the collimator plates defines the width of the energy windows

An ESA’s detectors are typically arranged around the base of the hemispheres. While Faraday cups detect incoming particles by measuring their net current, an ESA’s detectors usually count particle cascades generated by the strikes from individual particles. Such detectors would be impractical for a Faraday cup because they would be overwhelmed by solar UV photons. On a top-hat ESA, the tight spacing of the deflectors and a low-albedo coating7 on their surfaces ensure that very few photons reach the detectors. Each of the detectors is typically some type of electron multiplier, which uses an electrostatic potential in such a way that a strike by a single charged particle produces a cascade of electrons, which can then be registered. Channel electron multipliers (CEMs) were used for ACE/SWEPAM (McComas et al. 1998a), while micro-channel plates (MCPs) were used for Wind/3DP (Lin et al. 1995) and STEREO/IMPACT/SWEA (Sauvaud et al. 2008). Both CEM and MCP detectors require more complex calibration than is needed for a Faraday cup. For example, after each particle strike, an electron multiplier experiences a dead time, during which the electron cascade is in progress and the detector cannot respond to another particle. Furthermore, electron multipliers (and MCPs in particular) often exhibit significant degradation in their efficiency with time.

A typical top-hat ESA has a fan-beam field of view. The size and number of detectors define its azimuthal resolution and coverage, and ESAs can be designed with up to of -coverage. In contrast, most ESAs only sample particles over a limited range of elevation , and a number of strategies have been employed to provide -coverage. The ESAs in the Helios plasma investigation (Schwenn et al. 1975; Rosenbauer et al. 1977) and in Wind/3DP (Lin et al. 1995) were designed to rely on spacecraft spin to sweep their fan beams. Although the Cassini spacecraft was three-axis stabilized, its CAPS instrument suite was mounted on an actuator, which a motor rotated through about of azimuth every 3 min (Young et al. 2004). The MAVEN spacecraft is likewise three-axis stabilized, but its SWIA instrument (Halekas et al. 2015) incorporated a second set of electrostatic deflectors to effectively steer its fan beam by adjusting the path of ions entering the top hat. Finally, the unique design of MESSENGER/FIPS (Andrews et al. 2007) moved beyond the top hat to give that instrument wide -coverage (versus a fan beam) but reduced aperture size.

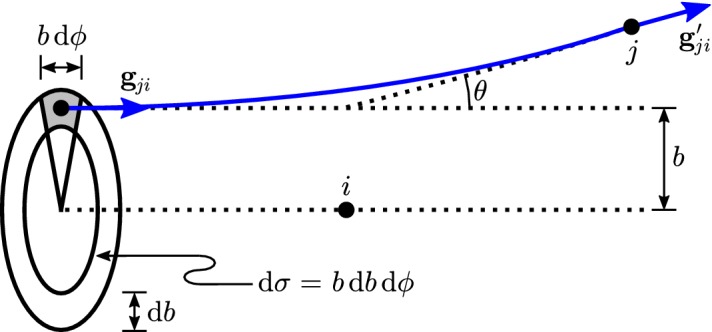

For any given value of , each ESA detector essentially has its own effective collecting area , which depends on the energy and direction of incoming j-particles. The number of j-particles detected from an infinitesimal volume of phase-space during a time interval is

| 71 |

where is the number density of j-particles in . Substituting Eq. (67) and converting to spherical coordinates gives

| 72 |

where has been parameterized in energy and direction rather than vector velocity. The total number of j-particles detected in is

| 73 |

Formally, the integrals in Eq. (73) are carried out over all energies and directions (i.e., all of phase space) but most ESAs are designed so that a given detector is only sensitive to particles from a relatively narrow range of energies and directions. Consequently, the detector’s effective collecting area is often approximated as

| 74 |

where is the nominal collecting area, is the look direction, and set the field of view, and and set the energy range of j-particles. Using Eq. (74) and assuming that , , and are small relative to variations in , we approximate Eq. (73) as

| 75 |

where

| 76 |

is known as the geometric factor. ESAs are often designed and operated in such a way that G is approximately constant.

If an ESA does not have any mass-spectrometry capability (see Sect. 2.2.3), then each of its detectors measures the count of all particles of any species that reach it. Thus, the measured quantity is

| 77 |

where the sum is carried out over all particle species j.

Equations (73) and (77) specify the response function of a top-hat ESA. A particle spectrum from such an instrument consists of a set of measured -values made over various -values and in various directions. Section 2.3 describes how the response function can be used to extract information about particle distribution functions from a measured spectrum.

Mass spectrometers

As noted above, neither a Faraday cup nor an ESA can, on its own, directly distinguish among different ion species: they simply measure the current and counts, respectively, of the incoming particles. A limited composition analysis, though, is still possible because the voltage needed for either type of instrument to detect a j-particle of speed v is proportional to . Though relative drift is often observed among different particle species in the solar wind, it generally remains far less than the bulk speed (see Sect. 1.4.4). Thus, in a particle spectrum, the signals from different particle species appear shifted by their mass-to-charge ratios. By separately analyzing these signals (see Sect. 2.3), values can be inferred for the moments of the various particle species.

This strategy does have significant limitations. First, it provides no mechanism for distinguishing ions with the same mass-to-charge ratio (e.g., and ). Second, even when particle species have distinct mass-to-charge ratios, ambiguity can still arise from the overlap of their spectral signal. For example, the mass-to-charge ratios of protons and -particles differ enough that values for their moments can often be derived for both species from Faraday-cup (e.g., Kasper 2002, Chapter 4) and ESA (e.g., Marsch et al. 1982b) spectra. Nevertheless, the -particle signal can suffer confusion with minor ions (e.g., Bame et al. 1975), and, especially at low Mach numbers, the proton and -particle signals can almost completely overlap (e.g., Maruca 2012, Sect. 3.3).

A mass spectrometer is required to achieve the most accurate measurements of solar-wind composition (see also the more complete review by Gloeckler 1990). As opposed to being a separate instrument, a mass spectrometer is typically incorporated into an ESA as its detector system and is used to measure the speed of each particle. The ESA ensures that only particles within a known, narrow range of energy per charge pass through. As each particle enters the mass spectrometer, an electric field accelerates it by a known amount. The particle then triggers a start signal by liberating electrons from a thin foil,8 which are detected via an MCP. Next, the particle travels a known distance to another foil.9 The particle triggers a stop signal by passing through this latter foil before finally reaching the detector. The time between the start and stop signals is the particle’s time of flight, a measurement of which allows the particle’s speed through the mass spectrometer to be inferred.

Several different designs have been developed for mass spectrometers for heliophysics. In a time-of-flight versus energy (TOF/E) mass spectrometer, such as Ulysses/SWICS (Gloeckler et al. 1992), ACE/SWICS (Gloeckler et al. 1998, Sect. 3.1), and STEREO/IMPACT/PLASTIC (Galvin et al. 2008), solid-state detectors (SSDs) are used to ultimately detect each ion. Unlike an electron multiplier, an SSD is able to measure the energy of individual charged particles. Therefore, a TOF/E instrument measures each ion’s initial energy per charge, speed through the instrument, and residual energy at the detector. Together, these quantities provide sufficient information to determine the ion’s mass, charge, and initial speed. In contrast, a high-mass-resolution spectrometer (HMRS) such as ACE/SWIMS (Gloeckler et al. 1998, Sect. 3.2) does not need to measure the ions’ residual energy and can simply use MCP detectors. An HMRS exploits the fact that passing through the start foil tends to decrease an ion’s charge state to either 0 or . The particle then passes through a known but non-uniform electric field, which deflects the singly ionized particle to the detectors. The electric field causes the time of flight to be mass dependent, so each particle’s mass can be inferred.

Analyzing thermal-particle measurements

A particle spectrum, whether measured by a Faraday cup or an ESA, must be processed in order to extract information about the observed particles. This involves inverting the instrument’s response function—Eqs. (69) and (70) for a Faraday cup, and Eqs. (73) and (77) for an ESA—so that particle moments or phase-space densities can be derived from measured current or counts. This section briefly describes three methods for achieving this: distribution-function imaging, moments analysis, and fitting of model distribution functions.

Distribution-function imaging