Abstract

HIV continues to significantly impact the health of communities, particularly affecting racially and ethnically diverse men who have sex with men and transgender women. In response, health departments often fund a number of community organizations to provide each of these subgroups with comprehensive and culturally responsive services. To this point, evaluators have focused on individual interventions, but have largely overlooked the complex environment in which these interventions are implemented, including other programs funded to do similar work. The Evaluation Center was funded by the City of Chicago in 2015 to conduct a city-wide evaluation of all HIV prevention programming. This article will describe our novel approach to adapt the principles and methods of the Empowerment Evaluation approach, to effectively engage with 20 city-funded prevention programs to collect and synthesize multi-site evaluation data, and ultimately build capacity at these organizations to foster a learning-focused community.

Keywords: empowerment evaluation, HIV prevention, multi-site evaluation, capacity building, LGBTQ

INTRODUCTION

HIV continues to have a substantial impact on the health of communities in the US, with an estimated 40,234 new diagnoses in 2014, bringing the total number of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the US to 972,166 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). The HIV epidemic has disproportionately affected large metropolitan areas (population of more than 500,000); HIV prevalence in these areas is more than twice that in small metropolitan areas (population of 50,000–499,999), and 3 times higher than in non-metropolitan areas (population <50,000) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Further highlighting these disparities, HIV incidence rates in small metropolitan (9.0/100,000) and non-metropolitan areas (5.5/100,000) are dwarfed by rates in larger cities like Miami (42.8/100,000), New Orleans (36.9/100,000), New York City (22.4/100,000), Chicago (18.7/100,000), and San Francisco (17.4/100,000) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015).

Within these large metropolitan communities, certain racial/ethnic, gender, and behavioral subpopulations are disproportionately affected by high rates of HIV infection. Specifically, Black men who have sex with men (MSM) comprised over 28% of all new HIV diagnoses in the US in 2014, the most of any subpopulations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). White and Latino MSM made up 22% and 19% of all incident cases, respectively. Black/African American women made up the largest portion of diagnoses among all non-MSM subgroups at approximately 12% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). In 2013 it was estimated that 22% of all transgender women in the US were living with HIV, meaning the odds of being HIV-positive in this population are 48 times greater than among individuals in the general population (Baral et al., 2013). Additionally, transgender women had new diagnosis rates of more than 3 times the national average at testing events reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). While strides have been made to reduce HIV transmission rates in the US, these subpopulations in urban environments remain at elevated risk due in part to challenges in adapting and tailoring intervention to be culturally competent, (i.e., activities that are respectful and responsive to the health beliefs and practices—and cultural and linguistic needs—of diverse population groups1)(Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010).

Over the past several decades, many new and innovative ways to combat the HIV epidemic have been developed and implemented. Behavioral interventions focus on increasing an individual’s knowledge, improving their ability to perceive risk, and motivating them to avoid risky behaviors. These can be delivered in a variety of ways, including one-on-one counseling sessions focused on goal setting (Lightfoot, Rotheram-Borus, & Tevendale, 2007; Richardson et al., 2004), small group meetings to teach skills and strategies about safer sex negotiation (Kalichman et al., 2001; O’Donnell, O’Donnell, San Doval, Duran, & Labes, 1998), and peer-led campaigns seeking to foster community conversations, increase awareness, and encourage safer sex norms (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999; Kelly, 2004). These types of interventions have been rigorously evaluated and shown to be efficacious in decreasing high-risk sexual behaviors (e.g., multiple sex partners, sex with anonymous partners) and increasing preventive behaviors (e.g., condom use, antiretroviral [ARV] adherence) (Herbst et al., 2005). In order to help providers choose which HIV prevention intervention is best suited for their target population, the CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project has compiled an extensive list of EBIs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). These are identified through an ongoing systematic review of the evidence in the field on specific interventions, and continue to serve a key role in the planning of prevention activities across the US.

In parallel with behavioral interventions, biomedical interventions such as Treatment as Prevention (TasP) for people living with HIV (PLWH) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-negative individuals, can significantly reduce the risk of HIV transmission and infection. TasP refers to a method of preventing HIV transmission by prescribing ARVs to PLWH to reduce their viral load to undetectable levels, and proper adherence to a TasP regimen has been shown to reduce the rate of transmission by 96% (Baeten et al., 2012; Cohen et al., 2016). Recent findings suggest that individuals with undetectable viral loads, and who adhere to treatment, are considered to have a transmission risk of effectively zero (Rodger et al., 2016). Likewise, oral PrEP – when taken daily as prescribed – has been shown to decrease the risk of contracting HIV through sex by at least 86% (Grant et al., 2010; McCormack et al., 2016). Despite the demonstrated efficacy of these biomedical interventions, uptake remains low, particularly within communities most affected by HIV; this indicates a need to integrate biomedical and behavioral interventions to achieve maximum effectiveness.

The combined efficacy of biomedical and behavioral interventions, targeted to HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals, can be observed in reductions in HIV transmission. New diagnoses have slowly declined over the past two decades, despite a growing population of PLWH. Due to this, government agencies have structured funding opportunities to enable the delivery of both types of interventions to effectively combat the spread of HIV. For example, several National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding opportunities (e.g., PA-17–106, PS-12–1201) in recent years have called for merging or coordinating behavioral and biomedical approaches. In line with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, many funding opportunities specify that interventions must be targeted to reach populations that are disproportionately affected by HIV (e.g., Black MSM, Black transgender women) (White House, 2015). Given structural barriers, these populations are often hard for traditional service systems to engage. Thus, to successfully engage them in care, coordination of prevention activities, often facilitated by local health departments, is crucial to ensuring all populations have access to culturally relevant programming. However, the implementation of these interventions is often relegated to individual organizations who tend to work independently from other funded entities. Therefore, evaluations of HIV prevention interventions are rarely able to account for other activities within a jurisdiction, highlighting the need for a holistic, community-level approach to evaluate HIV prevention initiatives.

Chicago, like other urban areas, is disproportionately affected by HIV; new HIV diagnosis rates are almost 3 times that of the national average (Chicago Department of Public Health, 2015). In response to this epidemic, the city funds and supports both biomedical and behavioral interventions, targeted at the populations most at risk for HIV infection, specifically racial/ethnic (e.g., Black and Latinx), sexual (e.g., MSM) and gender (e.g., transwomen) minority individuals. The Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) funds a wide variety of delegate agencies – community-based agencies unaffiliated with CDPH – to implement and evaluate this programming. The evaluation of programming is key, given the increasingly limited funds available for public health activities and the increased focus by national agencies on collecting evidence of effectiveness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). However, most HIV prevention agencies in Chicago, as well as those across the US, typically have scarce resources and little to no capacity to conduct program evaluation activities (Kegeles & Rebchook, 2005). In the context of a multisite initiative funded by CDPH, this case study aims to describe the implementation of a novel empowerment evaluation (EE) approach to evaluate the portfolio of HIV prevention activities in the city. EE is an evaluation framework designed to help communities monitor and evaluate their own performance (D. Fetterman & Wandersman, 2007; D. M. Fetterman, Kaftarian, & Wandersman, 2015; D. M. Fetterman & Wandersman, 2004). In partnership with an external university-based evaluation team, CPDH evaluated 20 HIV prevention interventions in 15 delegate agencies to effectively align internal decision making about program implementation with the broader goals associated with capacity building and self-determination.

Our analysis of this citywide, multisite evaluation initiative of HIV prevention services will compare and contrast our EE implementation to cases in which this approach has been used to evaluate single agencies, programs, or projects. We will also highlight the utility of a citywide, multisite evaluation to more accurately measure the effects that the current portfolio of prevention interventions has on combatting HIV at the community level, and challenges to conducting this type of evaluation. Specifically, this case study will describe activities central to conducting an EE, such as (1) the intensity of communication with sites, (2) the provision of technical assistance to develop evaluation materials, and (3) the collection and analysis of outcome data to assess improved program performance across and within sites. We will measure the success of our approach by describing our fidelity to the 10 EE principles highlighted by Fetterman and Wandersman (2005) (see Table 2). Furthermore, in consideration of evaluator resources, agency resources, agency-specific outcomes, and citywide knowledge generated, we will describe the advantages and disadvantages of our tailored EE approach in this context. We will present conclusions in the form of best practices for how to evaluate single- and multisite projects, specifically focused on what works/does not work for which type of site (and type of intervention), as well as what settings are most appropriate for this EE approach.

Table 2.

Theories of Empowerment Evaluation

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Empowerment | Helping individuals develop skills and abilities to help them gain control, obtain needed resources, and understand one’s environment so that they can become independent problem solvers and decision making. |

| Self-Determination | Helping program staff members and participants implement an evaluation, and thus chart their own course. This includes them being able to: 1. Identify needs 2. Establish goals 3. Create action plan 4. Identify resources 5. Make rationale choices 6. Pursue objectives 7. Evaluate results 8. Reassess based on findings 9. Continue to pursue foals |

| Capacity Building | Improving an organization’s ability to conduct an evaluation by fostering stakeholder motivation, skill, and knowledge. |

| Process Use | The more engaged individuals are in conducting their own evaluation, the more likely they are to find the results credible and act on any resulting recommendations. |

| Action and Use | In order to rigorously evaluate a program, stakeholder must close the gap between what interventions are supposed to do and what they are actually doing. |

METHODS

Case Study Environment

In November 2014, CDPH released a request for proposals (RFP) for HIV prevention projects that reflected key aspects of the CDC’s Funding Opportunity Announcement for Comprehensive High-Impact HIV Prevention Projects for Community-Based Organizations (PS15–1502). The health department requested proposals under five broad categories: A (HIV testing), B (Prevention for people who inject drugs), C (Prevention with positives), D (Prevention with negatives), and E (Evaluation). The evaluator, funded under Category E, was tasked with working directly with organizations funded under categories C and D, each of which had subcategories of funding:

C1: Prevention with Positives – CDC-Supported High-Impact Prevention (HIP) Behavioral Interventions

C2: Prevention with Positives – Innovative or Locally Developed Interventions

D1: Prevention with Negatives – PrEP Demonstration Projects

D2: Prevention with Negatives – Comprehensive Services Demonstration Projects

D3: Prevention with Negatives – Behavioral Interventions

The role of the university-based external evaluator included reviewing and refining logic models, developing an evaluation plan, and creating data collection tools for program monitoring, as well as conducting an overarching citywide process, implementation, and outcome evaluation of HIV prevention activities. To our knowledge, the approach of a department of public health engaging a single external evaluator to conduct a citywide HIV prevention evaluation is the first of its kind. Its implementation reflects the changing paradigm of public health funding to involve an evaluator in HIV intervention development, a model that has been successfully employed by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for more than a decade.

The intervention sites were housed in community-based organizations (CBOs), community health centers (CHC), and hospitals. Sites were given a choice, based on their funding category, to either implement an EBI or develop an innovative ‘homegrown’ intervention based on their experience working with the target population. EBIs, while shown to produce improved client outcomes, often are considered too stripped down to be culturally relevant to specific subpopulations (Veniegas, Kao, Rosales, & Arellanes, 2009). In response, there has been an increased focus on adapting these EBIs to specific community contexts (Kalichman, Hudd, & Diberto, 2010), with some EBIs being phased out entirely (e.g., Comprehensive Risk Counseling and Services [CRCS]). This contrasts with homegrown interventions, which are tailored specifically for the target populations, often resulting in more culturally relevant interventions (Eke, Mezoff, Duncan, & Sogolow, 2006). However, given the novelty and adaptation of these interventions, they also tend to lack rigorous evidence about producing improved client outcomes. Due to these factors, further evaluation of both types of interventions is necessary to ensure achievement of favorable client outcomes. Ultimately, CDPH-funded sites were split between these two intervention types, with 10 implementing an EBI and 10 implementing a homegrown intervention.

Evaluation Approach

Program evaluators at Northwestern University (NU) and AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC) were funded as the Center for the Evaluation of HIV Prevention Programs in Chicago (hereafter referred to as “Evaluation Center”) through the CDPH RFP. The evaluation team used an EE approach when working with CDPH delegate agencies. The Evaluation Center selected this approach primarily because the overarching goal for this partnership was to place the client or grantee, not the evaluator, in charge of conducting site-specific evaluation. Stakeholder ownership of a project increases the likelihood that evaluation activities will be integrated into the day-to-day operations of the organization (Patton, 2002). If achieved, this cultivates far greater and more sustainable influence, as these processes can be applied to current and future programming offered by an organization. EE enables organizations to continuously gather evidence about their intervention processes and outcomes, allowing for constant reflection and program improvement, which is preferable to a more traditional evaluation’s point-in-time evidence and recommendations. See Table 2 for an in depth description of the five theories of EE.

Traditionally, evaluators use one of the two major approaches to EE to guide their work with clients: the 3-Step Approach or the 10-Step Getting-To-Outcomes Approach. See Table 1 for a description of these approaches. However, to simultaneously work with 20 projects with vastly different expertise in evaluation and experience working with evaluators and researchers, the Evaluation Center developed a new approach to implement EE. In this approach, Evaluation Center staff attempted to adhere closely to the theories and principles of EE identified by (D. M. Fetterman & Wandersman, 2004), while also allowing for the flexibility to work with each site as they implemented their evaluation plan, which required different amounts of evaluation technical assistance from the evaluation team. The resulting approach that would be used with each site centered on the creation and implementation of six types of evaluation materials: 1) logic model, 2) data collection tool, 3) outcome measurement alignment grid, 4) data collection spreadsheet, 5) fidelity assessment tools, and 6) program manual, as well as the administration of consistent technical assistance. This will be described in further detail in the next section.

Table 1.

Principles of Empowerment Evaluation

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Improvement | EE improves program performance through helping initiatives expand on their successes and review and revise areas that need more attention. |

| Community Ownership | EE facilitates community ownership, which maintains use and sustainability of initiatives. |

| Inclusion | EE includes diversity, participation, and involvement from all levels of an initiative. |

| Democratic Participation | EE promotes decision making that is transparent and just. |

| Social Justice | EE devotes itself to focusing on social inequalities. |

| Community Knowledge | EE recognizes and appreciates community knowledge. |

| Evidence-Based Strategies | EE recognizes and uses scholarly knowledge in addition to community knowledge. |

| Capacity Building | EE reinforces stakeholders’ ability to evaluate their programs and to strengthen program planning and implementation. |

| Organizational Learning | EE allows organizations to learn how to improve themselves from their own successes and mistakes; data is also used to assess new practices and influence decision making when implementing programs. |

| Accountability | EE operates within existing policies and measures of accountability; empowerment evaluation also focuses on whether or not the initiative accomplished its goals. |

Description of Evaluation Activities

Project Launch

Delegate agencies received funding from CDPH on January 1st, 2015 and were expected to begin programming and engagement with the Evaluation Center on that day. However, most sites did not launch their interventions until later in Year One, with one launching in Year Two. The Evaluation Center initiated engagement with the delegate agencies by hosting a launch meeting on February 13th, 2015, where CDPH introduced the overall project and explained the roles and responsibilities of the Evaluation Center. The Evaluation Center used this time to introduce themselves to the project teams and explain their overarching evaluation plan. Following the launch meeting, the Evaluation Center identified two individuals from each agency – a field-level staff member and a director-level staff member – to serve as contact persons for evaluation activities throughout the project. Most of these individuals had little to no experience in program evaluation. Once these individuals were identified, in-person site visits were scheduled during the first quarter of Year One with each delegate agency. These hour-long visits were designed to benefit both the delegate agencies and the Evaluation Center. The Evaluation Center team was able to meet the project staff in person, tour the space in which the intervention would be conducted, and assess their readiness for evaluation activities. Delegate agencies learned about the evaluation materials they were required to develop, overarching evaluation activities, and the planned operations of the Evaluation Center throughout the course of the project.

Site-Specific Technical Assistance Activities

After the initial site visit, recurring conference calls were scheduled with each delegate agency to serve as check-ins to discuss intervention implementation; the status of drafting, revising, and finalizing evaluation materials; and, later in the project, the collection and analysis of outcome data. As sites progressed through this process, the frequency of these conference calls reduced based on the sites’ completion of evaluation materials and their diminishing need for technical assistance from the Evaluation Center.

Check-in calls were often broken into two sections. First, delegate agencies would provide updates on the implementation of their projects, highlighting any issues they were encountering and working with the Evaluation Center to identify solutions. Second, the Evaluation Center would discuss outstanding evaluation materials and review the timeline for their completion. At the end of each meeting, the Evaluation Center would identify post-meeting action items to be completed by the next meeting. While processes to complete materials varied from site to site, typically the Evaluation Center would explain the concept of the evaluation materials and then would provide examples of completed tools for similar projects. The agency would draft the materials based on their intervention and would share it with the Evaluation Center team, who would provide detailed feedback either in person or over the phone. Based on this feedback, sites would make additional revisions until everyone agreed that the materials were quality and ready to be finalized.

Overarching Technical Assistance Activities

In addition to one-on-one feedback given while drafting and revising evaluation materials, the Evaluation Center hosted a series of webinars for sites that addressed common concerns across the sites (e.g., study recruitment and retention, data collection and entry). These webinars were broadcast publically and were shared with sites for reference at a later date. Presenters were a combination of Evaluation Center and delegate agency staff with experience and expertise in the topic areas, with the goal to provide a dual perspective on the problems and solutions. These webinars were designed to increase evaluation knowledge and capacity within delegate agencies and their staff, and all received positive reviews from attendees in anonymous post-webinar surveys.

Outcome Evaluation Activities

The final key area in which the Evaluation Center engaged with the delegate agencies was the collection, sharing, analysis, and use of program outcome data. The NU institutional review board (IRB) deemed these activities to be not human subjects research, as the purpose of the data was for evaluation. However, all Evaluation Center staff were required to complete CITI Training modules in human subjects research and the data manager developed a one-page list of protected health information (PHI) guidelines for sites, which included NU requirements for accepting completely de-identified data. Using the data collection tools created by the sites, the Evaluation Center coached field staff through the process of collecting quality data from program clients. While three sites were able to use data reporting tools (e.g., REDCap {Research Electronic Data Capture}) to enter and share data, most sites did not have these resources. For sites that did not, the Evaluation Center created specialized Excel spreadsheets to enter and share their outcome data (See Figure 1). Due to limited staff capacity, the Evaluation Center spent extensive time tailoring these spreadsheets to minimize the likelihood of data entry errors, which were frequent during the first few data shares. Time and resources were spent educating delegate agency staff, via both a webinar and a guide developed by the Evaluation Center, on what constitutes protected health information (PHI) so that deidentified data could be shared. While most sites agreed to share this data with the Evaluation Center up front, one site requested a data use agreement to be signed before sharing data, so the Evaluation Center worked to facilitate that process. Starting on a monthly basis, agencies shared their updated spreadsheets, or their most recent data export from REDCap, containing inception to present information. The Evaluation Center data manager would check these data for errors and give feedback to sites. Eventually, as sites shared higher quality data, these shares were reduced to a quarterly basis to reduce time burden on project staff.

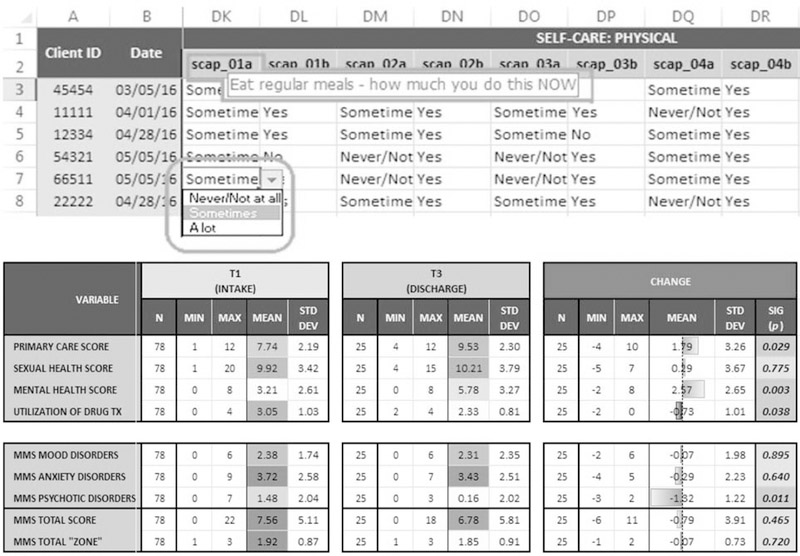

Figure 1.

Example data entry spreadsheet.

In addition to overarching outcome analyses that will be explored in future articles, the Evaluation Center provided sites with immediate feedback on their program performance. One way the Evaluation Center accomplished this was by building basic formulas and visualizations into the site data collection spreadsheets (See Figure 1). This allowed for real-time analysis and feedback to sites about their program’s success in achieving proposed outcomes. Additionally, beginning in Year Three of the funding cycle, the Evaluation Center began creating comprehensive outcome data reports that used data visualization techniques to highlight program performance (See Figure 2). These visually appealing reports were provided to sites and were used to make programmatic decisions, call out potential data collection and entry issues, and to begin conversations surrounding dissemination of results.

Figure 2.

Example outcome data report.

RESULTS

Applying the 10 Principles of Empowerment Evaluation

As mentioned previously, the Evaluation Center placed an emphasis on applying each of the 10 principles to the evaluation approach to ensure fidelity to EE, given the deviation from the traditional approach. The following section will outline how the Evaluation Center was able to utilize and highlight each principle within our work with delegate agencies. Descriptions of each principle can be found in Table 2.

Improvement

The Evaluation Center viewed the entire project as an opportunity for continuous improvement within delegate agencies, CDPH, and the Evaluation Center itself. For delegate agencies, this entailed improving evaluation capacity through individual and overarching technical assistance, as well as improving interventions by using process and outcome data to make programmatic changes. For example, one agency had difficulty collecting and sharing quality data early in the project, but after extensive technical assistance from the Evaluation Center, they improved their processes significantly. This resulted in a clean, analyzable dataset that was presented to a supervisor and resulted in the receipt of additional funding to scale up the program.

At the request of CDPH, the Evaluation Center used these outcome data, along with their experience working with the agencies, to inform how CDPH interacted with delegate agencies to extend beyond their traditional role of contract manager and scope reviewer to supporting program integration into agency systems. Similarly, CDPH used preliminary findings presented by the Evaluation Center to structure future funding announcements to maximize their effectiveness. The Evaluation Center sought to use this project to improve its understanding of the landscape of HIV prevention in Chicago, as well as its ability to effectively engage with agencies with different levels of experience.

Community Ownership

As mentioned, the Evaluation Center placed community ownership central to this approach from the beginning. This principle was achieved by facilitating the process for program field staff and project management to take control of the entire evaluation. For example, the Evaluation Center reviewed sites’ logic models and made recommendations for improvement, but ultimately the final decision was always the agencies’. Additionally, the sites were completely in charge of data collection and entry, with the Evaluation Center simply reviewing their work and sharing best practices to improve data quality. There were multiple occasions that the Evaluation Center would have liked to standardize logic models and data collections tools across projects, but instead supported decisions on how to ask questions in a way that was understandable and appropriate to their community. By serving as evaluation coaches, the Evaluation Center allowed sites to gain meaningful experience and truly own their evaluation.

Inclusion

The Evaluation Center worked hard to ensure both field-level staff and director-level staff were engaged in all evaluation activities by stressing the importance of having both types of individuals involved at the launch meeting. Field staff and program directors represent very different skill sets and experiences, so ensuring individuals from each level were included led to the development of quality, culturally relevant evaluation materials that could be integrated into the day-to-day activities of the program. By including field staff, who work most closely with the clients, data collection tools were tailored to the specific subpopulation(s) being served. By involving program directors, recommendations made based on findings were more likely to be implemented by the organization. In instances when there was staff turnover at a delegate agency, which was particularly common among field staff, a replacement was immediately identified, rather than relying on the project director as the sole contact.

Democratic Participation

In all activities, the Evaluation Center attempted to facilitate an open dialogue with the sites and ensure the final decisions were based on input from all individuals. While the Evaluation Center steered individuals towards best practices of crafting survey questions and creating measures, the site was fully involved in all decision making. One specific example is a site that asked an extensive amount of questions, and the Evaluation Center recommended they pare down the survey. However, the Evaluation Center avoided taking control of the decision making, and allowed the site to take the lead in identifying questions that were most important to them. While they finished the process with an extremely large questionnaire, their staff were happy and bought into the importance of collecting and sharing these data. Had the Evaluation Center made an executive decision to cut the instrument without including the site, the relationship could have been strained and the site likely would have felt less inclined to spend time collecting and sharing quality data. By remaining in an evaluation coaching role and guiding them in a particular direction, the Evaluation Center was able to be a part of the decision making without discouraging their participation.

Social Justice

A key factor in the use of this evaluation approach was emphasizing inclusivity and ensuring broad access to an intervention, particularly by marginalized populations identified by the delegate agency teams. Through their role as an evaluation coach, the Evaluation Center team was able to have targeted discussions and host a webinar on how to improve and diversify recruitment to reach subgroups to increase the ability of the resulting evaluation to truly measure improvements among the population being served. By helping improve programming and increasing the ability of agency stakeholders to plan and implement programming in the future, the Evaluation Center played an active role in working toward social justice for marginalized populations and communities disproportionally affected by HIV. Specifically, this evaluation partnership serves primarily sexual and gender minority individuals, as well as Black and Latinx communities.

Community Knowledge

While the Evaluation Center team had substantial experience working with PLWH and populations at risk for HIV (MSM, transwomen, etc.), delegate agencies were still seen as the community experts due to their close connection with the target populations. For example, while Evaluation Center staff offered feedback on how to structure survey questions to accurately capture outcomes, delegate agencies made the final edits to ensure the data collection tools were culturally appropriate and used terms that were understandable by the community. Furthermore, sites were encouraged to work closely with the populations they served to help improve the process. For example, one agency consistently worked with a group of clients to help lead intervention and evaluation development. They consulted with this group on all programmatic materials, from program activities to data collection instruments, before sending it to the Evaluation Center to finalize.

Evidence-Based Strategies

While half of the delegate agencies adapted and implemented EBIs to serve their clients, the focus of this project was adapting evidence based strategies to demonstrate how these projects operated in each organization’s context. For both the EBI adaptation and homegrown intervention development processes, the Evaluation Center attempted to inform all activities and decisions by providing access to the literature. For example, one site was implementing an EBI designed for HIV-negative individuals, but wanted to adapt it for PLWH because they saw the need in their community. Accordingly, the Evaluation Center helped them navigate the adaptation process to ensure there was fidelity to the core principles of the EBI, while also utilizing the staff knowledge of the community and the specific needs of PLWH. In another instance, an agency chose to implement a homegrown intervention, but wanted to pull heavily from what was shown to be effective in different contexts. In this case, the Evaluation Center helped them document the process of integrating multiple successful interventions into a streamlined curriculum.

The Evaluation Center also promoted the use of evidence-based strategies by ensuring the evidence collected throughout this evaluation was rigorous. To achieve this, they offered validated measures and other previously used data collection tools to inform their work developing their own surveys. Through the previously mentioned feedback loop, the Evaluation Center was able to ensure all materials were based in evidence and were adapted in appropriate ways.

Capacity Building

The principle of capacity building was extremely important to CDPH, as they hoped that funding an evaluator would not only facilitate collection of quality data to assess program success but also create a community of organizations dedicated to learning and improvement. Accordingly, the Evaluation Center ensured interactions with sites would enhance the stakeholders’ ability to conduct evaluation and improve their process for planning and implementing interventions. This included the technical assistance provided to individual sites to develop evaluation materials, as well as overarching technical assistance that included developing and disseminating webinars. To further show their dedication to this principle, the Evaluation Center focused one element of their overarching evaluation plan on measuring change in capacity via the Evaluation Capacity Survey. The Evaluation Center used the results from this survey to inform future activities, and further place a focus on building capacity at the organizations.

Organizational Learning

This approach sought to help organizations learn from their experiences, build on successes, and make mid-course corrections. For example, once quality outcome data were submitted to the Evaluation Center, the team created data visualization reports intended to start conversations about interpreting and using these data to improve programming. Some of these reports were able to highlight outcomes not achieving significant improvement. As mentioned previously, the adapted EE model used by the Evaluation Center placed an emphasis on helping agencies learn to deliberately link program activities to intended outcomes. Together this allowed sites to attempt to change specific programmatic activities to try to address these shortcomings. Additionally, with each discussion about evaluation materials and programmatic changes, the Evaluation Center attempted to steer the discussions to lessons learned and how the sites could use these same processes in the day-to-day operations of their organizations to evaluate and improve all programming. Another key example of organizational learning is our work with CDPH. Through monthly and quarterly meetings with various stakeholders, we were able to share information about the project to help their team learn about how to better structure their funding and monitoring mechanisms moving forward.

The Evaluation Center has also put a focus on working with sites to disseminate findings from these projects to extend organizational learning beyond the individual agencies. This has included assisting sites in drafting abstracts and presenting posters at conferences about the lessons learned from developing and/or implementing a specific intervention to their target population. These processes, combined with the site specific and overarching technical assistance activities and our collaboration with CDPH, created a community of learning across the project teams. This will allow for future organizational learning to occur as well, given the value of communicating programmatic success and challenges and engaging in conversation with diverse audiences present at conferences, meetings, and webinars.

Accountability

Prior CDPH funding initiatives only required delegate agencies to report information about achievement of project scopes (e.g., number of clients served, number of events held); data on achievement of proposed intervention outcomes were not reported to CDPH. However, this project marked the start of focusing on outcomes and mutual accountability from all parties. This approach helped make this transition possible, as the Evaluation Center focused on encouraging sites to think logically about their program activities. This helped sites understand the importance of measuring and reporting outcomes, rather than scopes alone. Similarly, the Evaluation Center’s work with CDPH helped them better understand the transition sites had to undertake, which pushed them to be more proactive in providing technical assistance to their delegate agencies.

DISCUSSION

This citywide, multisite evaluation initiative of 20 HIV prevention interventions serves as a case study of how an EE approach can be used in innovative ways as cities and funding entities put a greater emphasis on the need for demonstrable outcomes from their programming. By developing a new model for EE, the Evaluation Center was able to effectively work with each site simultaneously, despite limited staff capacity, by empowering delegate agencies to conduct their own evaluations. With the focus of discussion and activities on developing and using key evaluation materials, this model allowed sites to progress at their own pace based on their internal organizational capacity. Because of this, the Evaluation Center was able to offer tailored evaluation assistance to each site in an efficient manner. The remainder of this section will offer lessons learned from this project to compare and contrast EE’s usage in a multisite setting with its more traditional usage in evaluating a single agency, program, or project. It will also highlight the utility of EE to evaluate the entire portfolio of a multisite evaluation at both the city and site level.

Evaluation Successes

There were several advantages to using an EE approach in this multisite setting. The most notable of which allowed the Evaluation Center to tailor the intensity of engagement with sites, which allowed for a relatively small evaluation team to simultaneously plan and implement evaluations for 20 separate interventions. The model allowed sites with more expertise to create and/or adapt evaluation materials quickly, which gave Evaluation Center staff the chance to refine their feedback processes before sites that required additional assistance drafted these material. Additionally, given that the Evaluation Center helped sites troubleshoot areas such as recruitment and retention, our constant communication with all project teams allowed us to serve as a hub of best practices and share them – with permission – across sites, which in turn improved the quality of the evaluation being conducted at each site.

Evaluation Challenges

Evaluation Center staff also encountered several challenges while using an EE approach to work with 20 sites. While EE allows program staff to take the lead on the creation of an evaluation plan and data collection tools, the model used by the Evaluation Center emphasized this even more so, resulting in gaps in communication with certain sites during which little evaluation progress was made. Additionally, in the context of HIV prevention organizations, some sites had extremely limited evaluation expertise and research capacity, which resulted in long delays in creating and implementing evaluation materials, and occasional delays in sharing outcome data. While these delays ultimately did not hinder the success of the evaluation, they did slow the feedback and recommendation loop established by this model. Likewise, the aforementioned delays in launching the intervention reduced the amount of evaluation data that could be collected during the funding cycle, given the static nature of government funded project timelines. The Evaluation Center addressed these two issues by (1) reducing the frequency of shares to reduce burden, while still allowing for ample data sharing and feedback, and (2) making direct recommendations to the funder to account for delays in startup time by offering in additional technical assistance up front. Despite the fact that EE allowed Evaluation Center staff to allocate additional time and resources to sites based on need, a more hands-on approach could have been more effective.

Compounding some of these challenges was a high turnover rate of staff working for these organizations, meaning that Evaluation Center staff had to consistently re-engage with sites to bring the new contact person up to speed on the evaluation’s progress. Therefore future multisite evaluation initiatives like this will need to consider how to effectively account for staff turnover. Finally, while not standardizing data collection tools across sites gave the community ownership of the data collected, it presented challenges in conducting multisite analyses, as sites collected data on similar constructs using very different questions. This was in part due to lack of sufficient time before project launch for Evaluation Center staff to find a balance between community ownership and standardization. Future funders should consider funding evaluators before the project teams, or give time before interventions are set to launch, to allow for this planning to take place.

Utility of the Model

The efficacy of this EE model to produce (1) meaningful gains in site evaluation capacity and (2) multilevel outcome data that can be used to inform the current portfolio of HIV prevention activities in Chicago will be explored in future articles. However, this case study highlights the potential to tailor the EE approach to effectively engage a large number of entities in evaluation activities and the benefit these activities would have for the agency, program, and community. The Evaluation Center, despite a relatively small staff, was able to successfully engage with almost all delegate agencies throughout the entire three-year project. The Evaluation Center was able to assist all sites in the creation of each evaluation material and expose each intervention’s project staff to evaluation, which can be built upon in future funding cycles. Future manuscripts and reports will explore the findings from the site specific and overarching evaluation activities to further demonstrate the success of this project.

Best Practices

In order to maximize engagement from delegate agencies, it was crucial to identify ‘evaluation champions’ (i.e., the directors or field-level staff we interacted with) at the organizations to ensure that all field-level staff were dedicated to collecting quality data, and director-level staff were dedicated to prioritizing these activities. Having these champions at the organization helped speed up the process of creating and finalizing evaluation materials, which meant quality outcome data could be shared earlier in the project. As mentioned previously, staff turnover was high at these organizations, so occasionally the champions at the field staff level would leave the project. To mitigate the effects of this challenge, the Evaluation Center suggests putting a greater emphasis on identifying multiple champions at different levels in the organization, with the goal of fostering a lasting evaluation culture so that evaluation activities become part of the day-to-day operation of the organization.

For projects like this to be successful, it is vital for evaluators to gain active support from the funding agency. As select sites consistently questioned the necessity of complying with evaluation requirements, the Evaluation Center leveraged their relationship with CDPH to communicate the importance of engagement in these activities and the benefit these activities would have for the agency, program and community. Future groups should work closely with the funding agency to make sure the value of evaluation is integrated into programming from the outset. Additionally, this work should also focus on how the funder and evaluator can work together to make it easier for agencies and programs to fully participate in evaluation activities. Doing so could increase the buy-in of the delegate agencies which will lead to further organizational learning and a greater likelihood that they will use the process and outcome evaluation findings to improve and scale their programming.

CONCLUSIONS

As traditional and non-traditional funding entities increase their focus on outcomes rather than scopes, and designate funding in their announcements for external evaluators, the field of evaluation should continue to explore new ways to simultaneously engage multiple clients. The Evaluation Center’s experience using an adapted EE model to conduct single site and overarching evaluations with HIV prevention organizations and CDPH shows promise as an approach to achieving this goal. At the very least, this case study shows the ability to tailor an EE approach to successfully engage 20 separate project teams in evaluation activities at the same time. Future articles and analyses put forth by the Evaluation Center will explore the findings of the multifaceted overarching process, implementation, and outcome evaluations that were conducted while working with the sites. They will address topics such as the ability of this EE model to significantly increase delegate agency’s evaluation capacity, identify barriers and facilitators to successful program implementation and evaluation, and how outcome data collected by the sites can be used on a micro and macro level to assess the success of an entire funding opportunity. The lessons learned about advantages and disadvantages of this approach can be used to inform future evaluators about whether or not EE is an appropriate methodology for their specific multisite evaluation context, as well as how to adapt current models to maximize resources and effectively engage different types of sites. A recent methodology book is designed to help practitioners use the most appropriate stakeholder involvement approach for the task at hand (D. M. Fetterman, Rodriguez-Campos, & Zukowski, 2018).

Table 3.

Empowerment Evaluation Approaches

| 3-Step Approach | 10-Step Getting To Outcomes (GTO) |

|---|---|

| Mission: The group must have a shared vision on the values and purpose of the initiative in order to effectively plan and self-assess in the future. | 1. Use qualitative and quantitative data to assess the needs of the community the initiative wants to serve. |

| 2. Develop a consensus on the goals, the target population, and the intended outcomes of the initiative, ending in the creation of short and long term objectives. | |

| 3. Become knowledgeable on best practices through relevant literature reviews, which will inform the initiative at hand. | |

| 4. Assess the relevancy of the initiative to the target population, by consulting community leaders. | |

| Taking Stock: The group must prioritize specific activities required to accomplish the goals of the initiative at hand. | 5. Evaluate whether or not the organization has the capacity (including staffing, funding, expertise, and community connections) to effectively implement the proposed initiative. |

| 6. Plan the implementation of the initiative. Make sure to answer who will carry out the program, what objectives need to be completed, when, where, how, and why the chosen objectives will be completed, and what the effects will be of community participation in the initiative. | |

| 7. Ask if the initiative has remained true to its goals and if the initiative has been carried out with quality. This is done through describing what was done, how it was done, who was served, and changes that occurred along the way. | |

| Planning for the Future: After taking stock, the group must develop goals, strategies, and evidence that are related to the activities chosen in the taking stock step. | 8. Strategize how the efficacy of the program, in terms of meeting its goals and producing desired outcomes, will be measured. |

| 9. Use the existing findings of the initiative to educate ongoing decision making and quality improvement. | |

| 10. Evaluate the sustainability of the initiative by asking if the initial problem still exists and if future funding is needed to develop more data. |

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was supported by a grant from the Chicago Department of Public Health (RFP # DA-41–3350-11–2014-003).

Footnotes

SAMHSA.gov definition

References

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, … Partners Pr, E. P. S. T. (2012). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med, 367(5), 399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, & Beyrer C (2013). Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis, 13(3), 214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M Jr., & Holleran Steiker LK (2010). Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 6, 213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Community-level HIV intervention in 5 cities: final outcome data from the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. Am J Public Health, 89(3), 336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Improving the Use of Program Evaluation for Maximum Health Impact: Guidelines and Recommendations. Atlanta, GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/eval/materials/finalcdcevaluationrecommendations_formatted_120412.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report, 27, 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention. Atlanta GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Chicago Department of Public Health. (2015). HIV/STI Surveillance Report. Chicago Illinois: City of Chicago; Retrieved from https://www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/cdph/HIV_STI/HIV_STISurveillanceReport2015_revised.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, … Team HS (2016). Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N Engl J Med, 375(9), 830–839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke AN, Mezoff JS, Duncan T, & Sogolow ED (2006). Reputationally strong HIV prevention programs: lessons from the front line. AIDS Educ Prev, 18(2), 163–175. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman D, & Wandersman A (2007). Empowerment evaluation - Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(2), 179–198. doi: 10.1177/1098214007301350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman DM, Kaftarian S, & Wandersman A (2015). Empowerment Evaluation: Knowledge and Tools for Self-assessment, Evaluation Capacity Building, and Accountability.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman DM, Rodriguez-Campos L, & Zukowski AP (2018). Collaborative, Participatory, and Empowerment Evaluation: Stakeholder Involvement Approaches. New York, New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman DM, & Wandersman A (2004). Empowerment Evaluation Principles in Practice. New York, New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, … iPrEx Study, T. (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med, 363(27), 2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, Deluca JB, Zohrabyan L, Stall RD, … Team HAPRS (2005). A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 39(2), 228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Hudd K, & Diberto G (2010). Operational fidelity to an evidence-based HIV prevention intervention for people living with HIV/AIDS. J Prim Prev, 31(4), 235–245. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0217-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, … Graham J (2001). Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. Am J Prev Med, 21(2), 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, & Rebchook GM (2005). Challenges and facilitators to building program evaluation capacity among community-based organizations. AIDS Educ Prev, 17(4), 284–299. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.4.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA (2004). Popular opinion leaders and HIV prevention peer education: resolving discrepant findings, and implications for the development of effective community programmes. AIDS Care, 16(2), 139–150. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001640986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, & Tevendale H (2007). An HIV-preventive intervention for youth living with HIV. Behav Modif, 31(3), 345–363. doi: 10.1177/0145445506293787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, … Gill ON (2016). Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet, 387(10013), 53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CR, O’Donnell L, San Doval A, Duran R, & Labes K (1998). Reductions in STD infections subsequent to an STD clinic visit. Using video-based patient education to supplement provider interactions. Sex Transm Dis, 25(3), 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative research and evalution mentods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, Stoyanoff S, Bolan R, Weiss J, … Marks G (2004). Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: a multi-clinic assessment. AIDS, 18(8), 1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, van Lunzen J, … Group PS (2016). Sexual Activity Without Condoms and Risk of HIV Transmission in Serodifferent Couples When the HIV-Positive Partner Is Using Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. JAMA, 316(2), 171–181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veniegas RC, Kao UH, Rosales R, & Arellanes M (2009). HIV prevention technology transfer: challenges and strategies in the real world. Am J Public Health, 99 Suppl 1, S124–130. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House. (2015). National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States:updated to 2020. Washington, DC: Retrieved from https://aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf.References. [Google Scholar]