Abstract

3-Nitrobenzanthrone (3-NBA) is a suspected human carcinogen present in diesel exhaust. It requires metabolic activation via nitroreduction in order to form DNA adducts and promote mutagenesis. We have determined that human aldo-keto reductases (AKR1C1–1C3) and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) contribute equally to the nitroreduction of 3-NBA in lung epithelial cell lines and collectively represent 50% of the nitroreductase activity. The genes encoding these enzymes are induced by the transcription factor NF-E2 p45-related factor 2 (NRF2), which raises the possibility that NRF2 activation exacerbates 3-NBA toxification. Since A549 cells possess constitutively active NRF2, we examined the effect of heterozygous (NRF2-Het) and homozygous NRF2 knockout (NRF2-KO) by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing on the activation of 3-NBA. To evaluate whether NRF2-mediated gene induction increases 3-NBA activation, we examined the effects of NRF2 activators in immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC3-KT). Changes in AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 expression by NRF2 knockout or use of NRF2 activators were confirmed by qPCR, immunoblots, and enzyme activity assays. We observed decreases in 3-NBA activation in the A549 NRF2 KO cell lines (53% reduction in A549 NRF2-Het cells and 82% reduction in A549 NRF2-KO cells) and 40–60% increases in 3-NBA bioactivation due to NRF2 activators in HBEC3-KT cells. Together, our data suggest that activation of the transcription factor NRF2 exacerbates carcinogen metabolism following exposure to diesel exhaust which may lead to an increase in 3-NBA-derived DNA adducts.

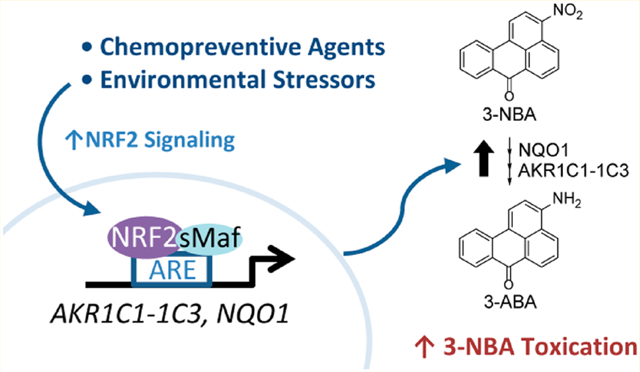

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

3-Nitrobenzanthrone (3-nitro-7H-benz[de]anthracen-7-one, 3-NBA) is the most mutagenic compound identified to date and is a suspected human carcinogen present in diesel engine exhaust and in airborne particulate matter.1,2 Inhalation of 3-NBA and other nitrated-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (NO2-PAHs) may increase the risk of lung cancer in individuals exposed to diesel exhaust and urban air pollution.3–5 NO2-PAHs such as 3-NBA require metabolic activation before they can exert their mutagenic and tumorigenic effects.6 Cytosolic nitroreductases catalyze a 6-electron reduction of the nitro group that allows formation of the hydroxylamino and amine products which go on to contribute to stable DNA adduct formation and mutagenesis.7–9

Identification of genes involved in the metabolic activation of representative NO2-PAHs is required to identify susceptible individuals that may carry genetic variants or epigenetic modification of those genes. We recently demonstrated that aldo-keto reductase 1C1, 1C2, and 1C3 (AKR1C1–1C3) display 3-NBA nitroreductase activity (Figure 1). This is the second recorded observation that AKR1C isoforms, which are primilarily recognized as ketosteroid reductases and/or hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases, exhibit reductase activity toward nitroaromatic compounds in an oxygen-independent manner.10,11 In both of these cases, AKR1C family members could compete with the widely recognized nitroreductase NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). We found that the catalytic efficiencies of NQO1, AKR1C1, and AKR1C3 are equivalent for the reduction of 3-NBA and that these enzymes contribute equally in the reduction of 3-NBA in human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro.10 Notably, AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 genes contain antioxidant response element (ARE) sequences within their promoters. Of these genes, AKR1C1–1C3 are consistently among the most upregulated genes by nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 (NRF2, encoded by NFE2L2) signaling in humans.12–14

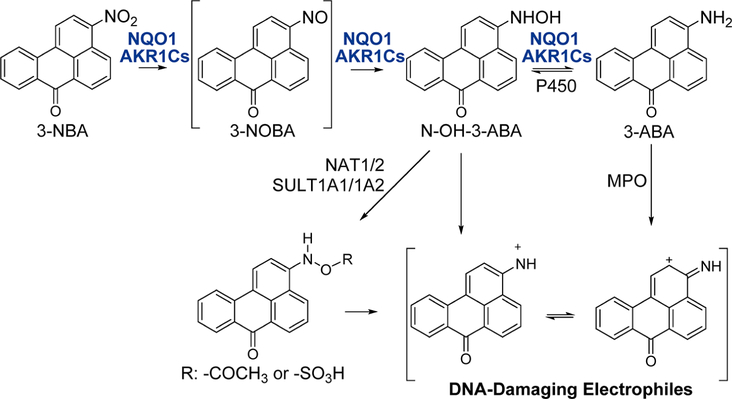

Figure 1.

Metabolic activation pathways of 3-NBA via AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 lead to DNA adduct formation. Metabolic activation of 3-NBA involves a six-electron reduction of the nitro-group involving sequential formation of the nitroso-, hydroxylamino-, and amine products catalyzed by NQO1 and AKR1C1–1C3, modified from ref 10. The hydroxylamino intermediate, N-hydroxy-3-aminobenzanthrone (N-OH-3-ABA) is intercepted by sulfonation or acetylation which creates an excellent leaving group for attack of the intermediate nitrenium or carbenium ion by DNA bases. The final product, 3-aminobenzanthrone (3-ABA), can also be activated by peroxidases to yield either a nitrenium or carbenium ion which contributes to DNA adduct formation. Abbreviations used: NQO1, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1; AKR1Cs, aldo-keto reductases 1C1–1C3; NAT1/2, N,O-acetyltransferase isozymes; SULT1A1/1A2, sulfotransferases 1A1 and 1A2; P450, cytochrome P450; MPO, myeloperoxidase.

NRF2 is a master regulator of stress response genes, and its activation increases the antioxidant capacity of the cell under stressed conditions.15–17 Under basal conditions, NRF2 is recruited to KEAP1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1), which in turn targets NRF2 for ubiquitination and rapid proteasomal degradation.18 Electrophiles and reactive oxygen species modify key cysteine residues in KEAP1 which prevents ubiquitination of NRF2.19,20 Newly synthesized NRF2 can thus evade ubiquitination, translocate to the nucleus, and bind to its heterodimeric partner small-Maf on ARE sequences of stress responsive genes.15,21,22 Remarkably, AKR1C1–1C3 genes are induced 4.8–39-fold in human cell lines following activation of NRF2, whereas NQO1 is induced 1.2–4.8-fold.13,14

NRF2 activators, such as the isothiocyanate R-sulforaphane (SFN) and synthetic triterpenoids such as 1[2-Cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oyl]imidazole (CDDO-Im), are currently in development as chemopreventive agents given their ability to induce genes for phase II detoxifying enzymes.23,24 However, if a subset of the ARE-gene battery contributes to metabolic activation of NO2-PAHs in humans, NRF2 activation may exacerbate their toxication, rather than their detoxication. Herein we aimed to determine whether NRF2 activation could affect 3-NBA bioactivation via upregulation of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 in two human lung epithelial cell lines.

The adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial (A549) cell line was employed in this study because NRF2 is constitutively active (i.e., derepressed), which results in high levels of expression of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1.25,26 We were able to manipulate expression of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 in A549 cells with heterozygous and homozygous genetic knockout of NRF2 via CRISPR-Cas9 in order to determine the effect of dysregulation of NRF2 on the toxication of 3-NBA. We also utilized NRF2 activators to upregulate AKR1C1-1C3 and NQO1 in immortalized human bronchial epithelial (HBEC3-KT) cells and examine their downstream effects on 3-NBA metabolism. HBEC3-KT are considered the best model for normal HBEC cells as they do not form colonies in soft agar or tumors in nude mice.27 To our knowledge, this is the first time that the effects of NRF2 activators have been determined in immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells. If pharmacological activators of NRF2 increase toxication of 3-NBA in HBEC3-KT cells, this may identify a subset of xenobiotics (i.e., diesel exhaust, NO2-PAHs) as especially dangerous since they will evade chemopreventive strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Caution: 3-NBA and its derivatives are potent mutagens and suspected carcinogens. They should be handled in accordance with NIH Guidelines for the Use of Chemical Carcinogens.

Chemicals and Reagents.

3-NBA and 3-ABA were synthesized as described previously.28,29 The purity and identity of these compounds were verified by UV spectroscopy, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and high-field 1H NMR spectroscopy. All other chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available, and all solvents were of HPLC grade. (S)-(+)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthol (S-tetralol), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), dithiothreitol (DTT), 1-acenaphthenol, dicoumarol (Dic), menadione, and D-glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) were purchased from Millipore-Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) from Leuconostoc mesenteroides was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ). 1-(2-Cyano-3,12,28-trioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-yl)-1H-imidazole (CDDO-Im) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, U.K.) and R-sulforaphane (SFN) was purchased from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN).

Cell Culture.

The adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cell line A549 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA; ATCC #CCL-185) and cultured in Kaighn’s Modification of Ham’s F-12 Medium (F-12K) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. A549 cells were passaged every 4 days at a dilution of 1:7. Human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC3-KT) were a kind gift from Dr. John Minna at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and have been immortalized via the overexpression of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4) and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT). HBEC3-KT cells were maintained in Keratinocyte-SFM supplemented with human recombinant Epidermal Growth Factor and Bovine Pituitary Extract. HBEC3-KT cells were passaged every 5 days at a dilution of 1:4. All cells were cultured in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C in 100 mm culture plates. Cultured cells with a passage number of 5–20 were used in the experiments to reduce selection of subclones. Cells were routinely authenticated by short-terminal repeat DNA analysis and were mycoplasma-free (DNA Diagnostics Center Medical, Fairfield, OH).

Development of NRF2 Knockout A549 Cell Lines.

A549 cells with homozygous knockout (A549 NRF2-KO) and heterozygous knockout (A549 NRF2-Het) of the endogenous NFE2L2 gene, which encodes NRF2, were created by transfecting A549 cells with pLentiCRISPR-v2 (a gift from Dr. Feng Zhang, Addgene plasmid #52961) containing a guide RNA (gRNA) directed against the gene sequence for the Neh2 domain within the NFE2L2 locus (5′-TGGAGGCAAGATATAGATCT-3′), which encodes amino acids that bind KEAP1. NRF2 homozygous and heterozygous knockout clones were those in which the Cas9-mediated cleavage was repaired out-of-frame. After 2 days of puromycin selection, cells were clonally selected by serial dilution, and positive clones were identified as previously described.30 Control cells, referred to as A549 wildtype (A549 wt), are the pooled population of surviving cells transfected with an empty pLentiCRISPRv2 vector treated with puromycin. These cell lines were authenticated by short terminal repeat profiling and verified to be mycoplasma-free prior to use in this study.

Quantification of mRNA Expression by RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and samples were treated with RNasefree DNase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA yield and purity were then measured spectrophotometrically at 260 nm using a Nanodrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the High Capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Resulting cDNA samples were analyzed using QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in the Chromo4 System (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Oligonucleotide primers specific to human AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, NQO1, and GAPDH are described in Supporting Information, Table S1 and have been previously validated.31

The conditions for the real-time PCR were as follows: 95 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, X°C (annealing temperature) for 30 s and 72 °C (extension temperature) for 30 s (where X = 57 °C for AKR1C1; 58 °C for GAPDH; 59 °C for NQO1; and 61 °C for AKR1C2 and AKR1C3). Data analyses were based on quantifying fg levels for each transcript using standard curves constructed with full-length standards (2 500 000 to 0.025 fg) as previously described by us.31 The RT-PCR method for each transcript was linear (r = 0.995) over a dynamic range (109) as determined by plotting the log10 fluorescence intensity vs the number of cycles. Full-length standards (2 500 000 to 0.025 fg) were generated for AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, and NQO1 from their appropriate cDNA plasmids (pcDNA3-AKR1C1, pcDNA3-AKR1C2, pcDNA3-AKR1C3, pkk233–2-NQO1). PCR product standards (2 500 000 to 0.025 fg) were generated for GAPDH with the following: forward primer, 5′-TCCTCCTGTTCGACAGTCAG-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-CACAGACACCCCATCCTATC-3′. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and amounts of the target cDNA (femtograms) were corrected by amplicon length so that copy number of each gene was determined. The resulting values were subsequently normalized and reported as a ratio of copy number of “target gene”:GAPDH.

Immunoblotting.

Nuclear and cytosolic extracts were prepared with Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (NE-PER) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Nuclear and cytosolic proteins (25 μg) were resolved electrophoretically using 10% (w/v) SDS polyacrylamide gels. Gels were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T). Blots were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies used in this study were as follows: murine anti-human NRF2 (ab62352; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.); rabbit monoclonal anti-human AKR1C1/1C2 (ab179448; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.); murine monoclonal anti-human AKR1C3 (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO); murine monoclonal anti-human NQO1, a kind gift from Professor David Ross (University of Colorado); murine monoclonal anti-human Lamin-A (sc7148; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX); and murine monoclonal α-Tubulin (NB100–690; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO). Blots were washed in PBS-T and incubated with species-appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:1500 dilution) in 5% nonfat milk in PBS-T buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Protein–antibody complexes were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Biotechnology, Waltham, MA) and imaged with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Band intensity was quantified by Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Lamin-A was used as a loading control for nuclear fractions while α-Tubulin used as a loading control for cytosolic proteins.

NQO1 Activity Assay.

NQO1 activity was quantified as described previously.32 A549 wt, NRF2-Het, and NRF2-KO cell lines were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and cultured overnight. After 24 h, the medium was decanted, and the cells were incubated with 75 μL of lysis solution (0.8% (w/v) digitonin in 2 mM of EDTA) for 15 min at 37 °C. Portions (20 μL) from each well were transferred to another 96-well plate for protein quantification with a BCA Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The remainder was assayed for NQO1 activity as follows. First, the reaction mixture cocktail was prepared to contain: 1 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 26.7 mg of bovine serum albumin, 270 μL of 1.5% Tween-20, 202 μL of 1 mM FAD+, 270 μL of 150 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 24 μL of 50 mM NADP+, 80 units of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 12 mg of MTT, 40 μL of 50 mM menadione (added immediately before use), and Milli-Q water in a final volume of 40 mL. An aliquot of the reaction mixture (200 μL) was added to each well and incubated for 5 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of 0.3 mM dicoumarol solution (in 0.5% DMSO and 5 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4). Absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a Synergy 2 multimode plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). To control for nonspecific quinone reductase activity, matched blanks for each treatment group were included by adding 50 μL of 0.3 mM dicoumarol solution prior to the addition of the reaction mix. The average absorbance values from these wells were subtracted from the experimental wells.

NQO1 activity assays were performed in HBEC3-KT cells essentially as described for A549 cells with the following modifications: HBEC3-KT cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and were cultured overnight. NRF2 activators (2.5–100 nM CDDO-Im and 0.625–10 μM SFN) or vehicle control (0.05% DMSO) were applied in fresh media and incubated for 48 h prior to measuring NQO1 activity.

Detection of 3-ABA Formation in Cell Culture.

The fluorescence of 3-ABA was used to measure the nitroreduction of nonfluorescent 3-NBA in cell culture as published previously.10 To assess the contribution of NRF2 signaling in the metabolic activation of 3-NBA, experiments were conducted in various A549 cell lines (A549 wt, A549 NRF2-Het, and A549 NRF2-KO). Assays for 3-ABA formation in A549 cell lines were performed in 96-well plates 24 h (±2 h) after seeding of 1 × 104 A549 cells per well. After allowing 24 h for cells to attach, they were treated with 3-NBA in 0.1% DMSO in phenol red-free DMEM/F-12 (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12). Formation of 3-ABA was measured (λex 520 nm, λem 650 nm) with a Synergy 2 multidetection microplate reader (Biotek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT) and quantified by using calibration curves constructed with 3-ABA in phenol red-free DMEM/F-12 media.

Measurement of 3-ABA formation in HBEC3-KT cells was performed in 96-well plates by plating 2 × 104 cells which were allowed to recover for 24 h to allow them to attach, before they were treated with NRF2 activators (2.5–100 nM CDDO-Im or 0.625–10 μM SFN) or vehicle control (0.05% DMSO) for 48 h. Media was then replaced with fresh phenol red-free K-SFM containing 1.25–10 μM 3-NBA in 0.1% DMSO. Formation of 3-ABA (pmol) was quantified by using calibration curves constructed with 3-ABA in phenol red-free K-SFM.

Cell Proliferation and Imaging.

Cell proliferation measurements were conducted through label-free high contrast brightfield counting on a Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) every 24 h. Images were captured at 4× in the brightfield channel. Two high-contrast brightfield images were captured at each time point: an in-focus image for reference and a defocused image for cell counting. Image preprocessing was employed to enhance contrast to reduce each cell to a single bright spot. To this end, the defocused image was processed with a black background and a 20 μm rolling ball subtraction. This resulted in a dark image with bright spots delineating cells. Gen5 software (Version 3.04, BioTek, Winooski, VT) applied masks to identify each cell for counting. Cell counts were normalized to area and expressed as number of cells per mm2.

MTT Assay For Cell Viability.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays were performed in 96-well plates to assess cell metabolic activity as a measurement of cell viability. A549 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 per well in a 96-well plates, and following a 24 h attachment period, they were exposed to low and high doses of 3-NBA (1.25 μM and 10 μM, respectively). After incubation for 24 h, the medium was removed, and 110 μL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) diluted in F12K media was added directly to the wells and the plates incubated for 4 h at 37 °C at 5% CO2. MTT assays with HBEC3-KT cells were performed under the same conditions as described for the 3-ABA formation assay. Briefly, 2 × 104 cells were plated in 96-well plates and were allowed to recover for 24 h to allow cell attachment. HBEC3-KT cells were then treated with NRF2 activators (50 nM CDDO-Im and 5 μM SFN) or vehicle control (0.05% DMSO) for 48 h. Media was then replaced with fresh phenol red-free K-SFM containing 1.25 and 10 μM 3-NBA in 0.1% DMSO. After 24 h, the media was removed, and 110 μL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT (Millipore Sigma) diluted in K-SFM media was added directly to the wells and the plates incubated for 4 h at 37 °C at 5% CO2.

Upon completion of the 4 h incubation, the MTT solution was removed, and remaining cells were solubilized in 200 μL of DMSO. Formation of the purple formazan was assessed spectrophotometrically using a Synergy 2 (BioTek) plate reader at 570 nm. Viability is expressed as a percentage of the vehicle control. Results were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA to compare cell viability within each 3-NBA dose by NRF2 knockout or induction status.

SYTOX Green Cytotoxicity Assay.

Cell death was quantified to assess cytotoxicity due to 3-NBA treatment. A549 cells were plated as described above and were exposed to low and high doses of 3-NBA (1.25 μM and 10 μM, respectively). After exposure to 3-NBA for 24 h, cells were stained with 0.1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to stain living and dead cells (total cell count) and 100 nM SYTOX Green Nuclear Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). SYTOX Green is impermeable to living cells and stains dead cells with a compromised membrane. Images were captured at 4× in the DAPI and GFP channels with a Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). Image preprocessing was employed to obtain the best possible enhancement of contrast, as described above with a black background and a 20 μm rolling ball. Gen5 software applied masks to identify each cell for counting. Cell counts were normalized to area and expressed as number of cells per mm2. The percentage of dead cells was calculated as Results were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA to compare cell death within each 3-NBA dose by NRF2 knockout or induction status.

RESULTS

Effect of NRF2 Gene Editing on Expression of ARE-Regulated Genes in A549 Cells.

To investigate the role of NRF2-KEAP1 signaling on 3-NBA activation, we first examined the expression of the ARE-regulated AKR1C and NQO1 genes in A549 cells by qPCR (Figure 2). To manipulate NRF2 signaling in A549 cells, genetic knockout was required; A549 cells with homozygous knockout (A549 NRF2-KO) and heterozygous knockout (A549 NRF2-Het) of the endogenous NFE2L2 gene were used for this study. As expected, wildtype A549 cells expressed high levels of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 due to constitutive activation of NRF2 caused by somatic mutation in KEAP1 and epigenetic alteration by methylation in the KEAP1 promoter.25,26,33 Consequently, wildtype A549 cells exhibited high constitutive NRF2 activity, and expression of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 in all A549 cell line variants were unresponsive to NRF2 activators such as SFN and CDDO-Im (Figure S1).

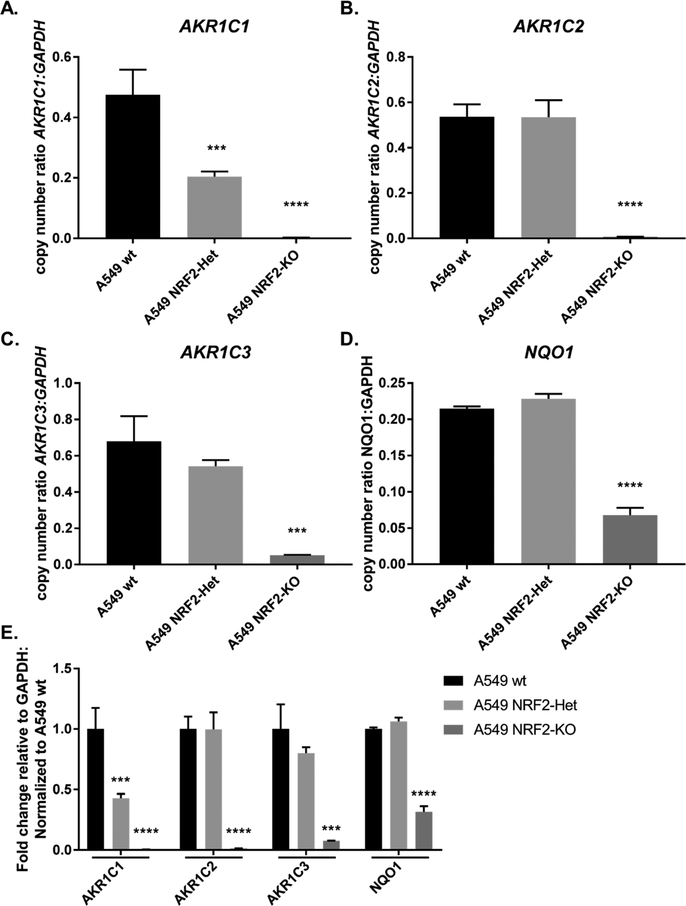

Figure 2.

Heterozygous and homozygous knockdown of NRF2 in A549 cells have differential effects on AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 expression. Gene expression of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 were quantified in three cell line variants of A549 (A549 wt, A549 NRF2-Het, A549 NRF2-KO) and expressed as copy number normalized to GAPDH (A–D) or fold-change relative to A549 wt (E). Bar graphs show mean copy number ± SD of n = 3/group for AKR1C1 (A), AKR1C2 (B), AKR1C3 (C), and NQO1 (D). Absolute expression levels of each gene were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to assess the difference in gene expression due to NRF2 signaling across cell lines. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the A549 wt cell line (*p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.001; **** p ≤ 0.0001).

We found that NRF2 activity is required for basal expression of AKR1C1–1C3 as the corresponding mRNA transcripts were essentially absent from the NRF2-KO cells (Figure 2A–C). The absolute mRNA level of each gene was expressed as copy number normalized to GAPDH which revealed that AKR1C1, AKR1C2, and AKR1C3 were expressed at similar levels in A549 wt cells (Figure 2A–C, E). These three isoforms experienced different sensitivities to NRF2 knockout. AKR1C1 transcript levels experienced a 57% reduction in the heterozygous knockout and a 99.5% reduction in the homozygous NRF2 knockout cell line. AKR1C2 transcript levels were virtually unchanged (0.3% decrease) in the heterozygous knockout and reduced by 98.7% in the homozygous NRF2 knockout. Finally, AKR1C3 transcript levels experienced a 20% reduction in the heterozygous knockout and a 92.4% reduction in the homozygous NRF2 knockout. By contrast, NQO1 mRNA levels decreased by 68.3% in NRF2-KO cells relative to the A549 wt control and seemed relatively unaffected in NRF2-Het cells (Figure 2D,E).

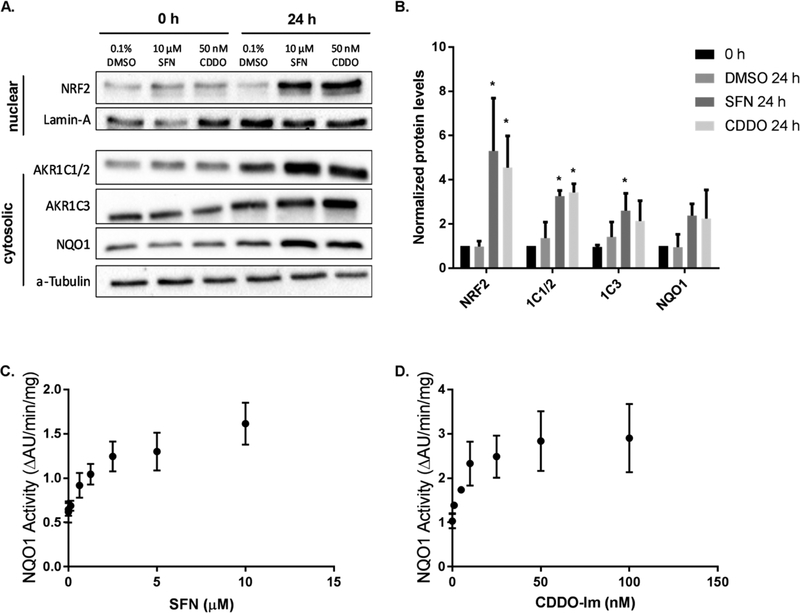

When these three cell lines (A549 NRF2-KO, A549 NRF2-Het, and A549 wt) were assayed by Western blot, we confirmed complete knockout of NRF2 in the nuclear fraction in the NRF2-KO cells and a partial knockdown in the NRF2-Het cells (Figure 3A,B). A slight decrease in the molecular weight of NRF2 in the NRF2-Het cells was observed which is likely due to a deletion of the DLG region of the NFE2L2 gene targeted by the CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA that was repaired inframe. We also verified that NRF2 activators did not increase NRF2 localization to the nucleus in A549 NRF2-KO, A549 NRF2-Het, and A549 wt cell lines to ensure NRF2 levels were stable and could not be induced by environmental stimuli (Figure S2).

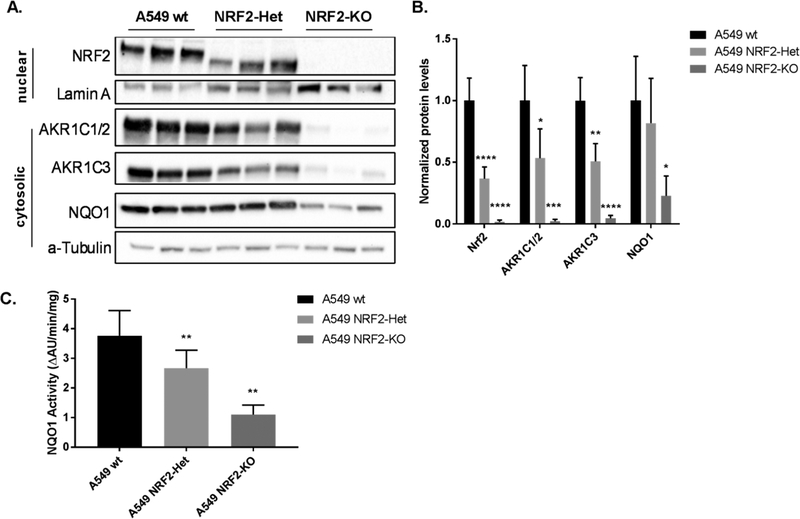

Figure 3.

Heterozygous and homozygous knockdown of NRF2 in A549 cells have differential effects on AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 protein levels. Protein samples from cell line variants of A549 (A549 wt, A549 NRF2-Het, A549 NRF2-KO) were collected in three independent experiments and were quantified by immunoblot analysis (A). Band intensities of cytosolic proteins were normalized to α-Tubulin, and band intensities of nuclear protein were normalized to Lamin A. Bar graphs show mean normalized intensities ± SD of n = 3/group (B). The AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 family members were collectively referred to as AKR1C1/2 because immunoblot techniques were not able to differentiate between them. A NQO1 activity assay was conducted in the three A549 cell lines (C). Bar graphs show mean ± SD of n = 3/group. Reduction of NRF2, AKR1C1–1C3, and NQO1 protein levels or enzyme activity due to NRF2 knockout were statistically significant when tested by a one-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001; **** p ≤ 0.0001). wt A549 cells were used as a reference for statistical analysis for each protein.

AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 protein levels were investigated to ensure changes in mRNA transcription were functional. AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 (Swiss Prot: Q04828/P52895) protein sequences are 98% identical, and the antibody used (ab179448) recognizes both isoforms (labeled AKR1C1/2). The band corresponding to AKR1C1/2 was difficult to detect in NRF2-KO cells, which is in agreement with mRNA measurements (Figure 3A). The abundance of AKR1C1/2 protein was also reduced in NRF2-Het cells, compared to the A549 wt cells. It is impossible to determine whether both isoforms are present or their relative protein levels based on this antibody, but we would expect that AKR1C1 protein levels are reduced to a greater extent than AKR1C2 based on qPCR results. Protein levels of AKR1C3 were visualized using a specific antibody against AKR1C3 and were in accordance with qPCR results. NQO1 protein levels were reduced by 60–68% in the NRF2-KO cells, but no significant difference was observed between the A549 NRF2-Het and A549 wt cell lines (Figure 3A,B).

We also conducted Prochaska assays to measure NQO1 enzyme activity as a readout of NRF2 signaling.32 Enzyme activity measurements differed slightly from immunoblot results, and we found a 29% reduction of NQO1 activity in NRF2-Het cells compared with A549 wt cells, which suggests that the partial NRF2 knockout leads to slightly reduced NQO1 activity levels. We also observed a 70% reduction of NQO1 activity in the NRF2-KO cell lines compared to A549 wt cells, indicating a dose–response relationship between NRF2 signaling and NQO1 activity where each functional copy of NRF2 contributes to approximately 30% of NQO1 enzyme activity (Figure 3C). It is likely that the enzymatic activity assay was more sensitive to slight decreases in NQO1 protein levels as compared with the immunoblot assays.

Effect of NRF2 Gene Editing on Activation of 3-NBA.

Given that heterozygous and homozygous knockout of NRF2 drastically reduced mRNA and protein levels of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1, we next examined the effect of these phenotypes on 3-NBA activation. We used a 96-well plate assay to monitor 3-ABA formation in vitro with low and high doses of 3-NBA (1.25 μM and 10 μM 3-NBA, respectively). Maximal differences in 3-ABA formation across cell line were observed by 8 h following treatment. Cells were lysed following 3-ABA measurements for protein quantification with a BCA Assay Kit. Protein and cell count normalization was necessary given the differences in proliferation between each cell line. We noticed that A549 wt cells had a significant growth advantage over the NRF2 heterozygous and homozygous cell lines (Figure S3). This has been observed previously, and we accounted for these differences with protein normalization.34,35 BCA results also confirmed that average protein levels of A549 NRF2-KO cells were approximately 35% lower than that of A549 wt cells 24 h after plating 1 × 104 cells (data not shown).

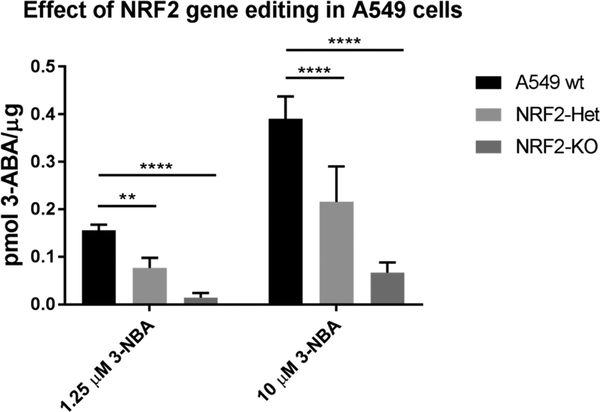

Heterozygous NRF2 knockout led to 53% ± 8.2% and 52% ± 15.7% decreases in total 3-ABA formation in A549 NRF2-Het cells following exposure to a low dose (1.25 μM) and high dose (10 μM) of 3-NBA, respectively (Figure 4). Meanwhile, homozygous NRF2 knockout led to 80% ± 5.5% and 78% ± 9.0% decreases in total 3-ABA formation in A549 NRF2-KO cells following exposure to a low dose (1.25 μM) and high dose (10 μM) of 3-NBA, respectively. The effect of reduced NRF2 signaling is consistent regardless of the 3-NBA dose received. In this regard, we tested four doses between 1.25 and 10 μM 3-NBA, data not shown. It is likely that basal levels of NQO1 activity contribute to 3-ABA formation in the NRF2-KO cell line because 29% of total NQO1 activity remained in this cell line despite complete loss of NRF2 and AKR1C1–1C3 protein levels (Figure 3C).

Figure 4.

Reduction in NRF2 signaling leads to decreased formation of 3-ABA in A549 cell line variants in a dose-dependent manner. The intrinsic fluorescence of 3-ABA (λex 520 nm, λem 650 nm) was used to detect the final reduction product 3-ABA after 8 h of exposure to 1.25 or 10 μM 3-NBA. Values are expressed as mean ± SD and data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to assess the difference in 3-ABA formation due to NRF2 signaling within each 3-NBA treatment group. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the A549 wt cell line (**p ≤ 0.01; **** p ≤ 0.0001). wt A549 cells were used as a reference for statistical analysis. Experiments were repeated four independent times (n = 4).

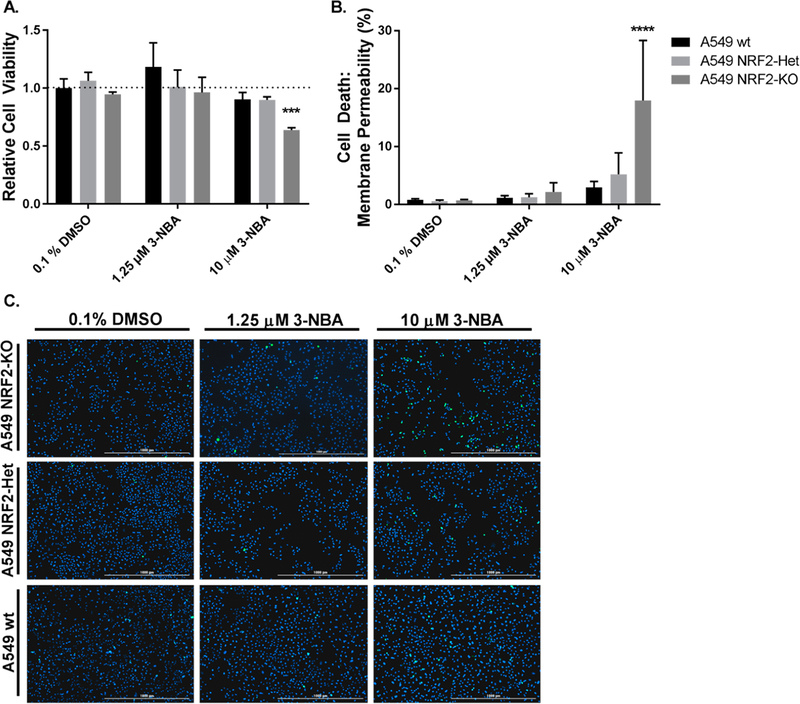

Effect of NRF2 Knockout on 3-NBA-Mediated Cytotoxicity in A549 Cells.

Given that NRF2 signaling increases the antioxidant capacity of the cell and plays a critical role in the cellular defense against oxidative and electrophilic stressors, we examined the effect of NRF2 signaling on cell viability and death following 3-NBA exposure. We assessed cell viability following a 24 h exposure period to 3-NBA under the same conditions described above for the assay of 3-ABA formation. A549 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 per well in 96-well plates and were exposed to low and high doses of 3-NBA (1.25 μM and 10 μM, respectively) after a 24 h attachment period. We found that 3-NBA treatment in the A549 wt cells had limited effects on cell viability. We also found that cell viability was unaffected in A549 NRF2-Het cells following exposure to both 1.25 and 10 μM 3-NBA, indicating that intermediate levels of NRF2 were sufficient to protect against electrophilic and oxidative stress that may be mediated by this carcinogen. However, we found that cell viability was significantly reduced by 40% in A549 NRF2-KO following exposure to 10 μM 3-NBA (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Effect of NRF2 signaling on cell viability and cytotoxicity in A549 cells. MTT-based cell viability was assayed using A549 cell variants (A549 wt, A549 NRF2-Het, A549 NRF2-KO) exposed to 1.25 μM and 10 μM 3-NBA (A). Bar graphs show mean ± SD from three independent experiments. To measure cytotoxicity, A549 wt, NRF2-Het, and NRF2-KO cells were treated with 1.25 μM and 10 μM 3-NBA and stained with SYTOX Green and Hoechst at 24 h (B,C). Cell death was expressed as a percentage of the total cell count. Bar graphs show mean ± SD of n = 3/group. Data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to assess the difference in viability or cell death within each 3-NBA treatment group due to NRF2 knockout status. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the vehicle treatment (0.1% DMSO) in A549 wt cells (*** p ≤ 0.001; **** p ≤ 0.001).

Cell death was also measured to assess cytotoxicity. A549 cells were plated as described above and were exposed to low and high doses of 3-NBA (1.25 μM and 10 μM, respectively). After a 24 h exposure period to 3-NBA, cells were stained with Hoechst and SYTOX Green to estimate total and dead cell counts. We found that 3-NBA treatment in the A549 wt cells had a limited effect on cell death. The only significant finding observed was an increase in cell death after exposure to 10 μM 3-NBA in the NRF2-KO cells, which is in agreement with cell viability studies (Figure 5B,C).

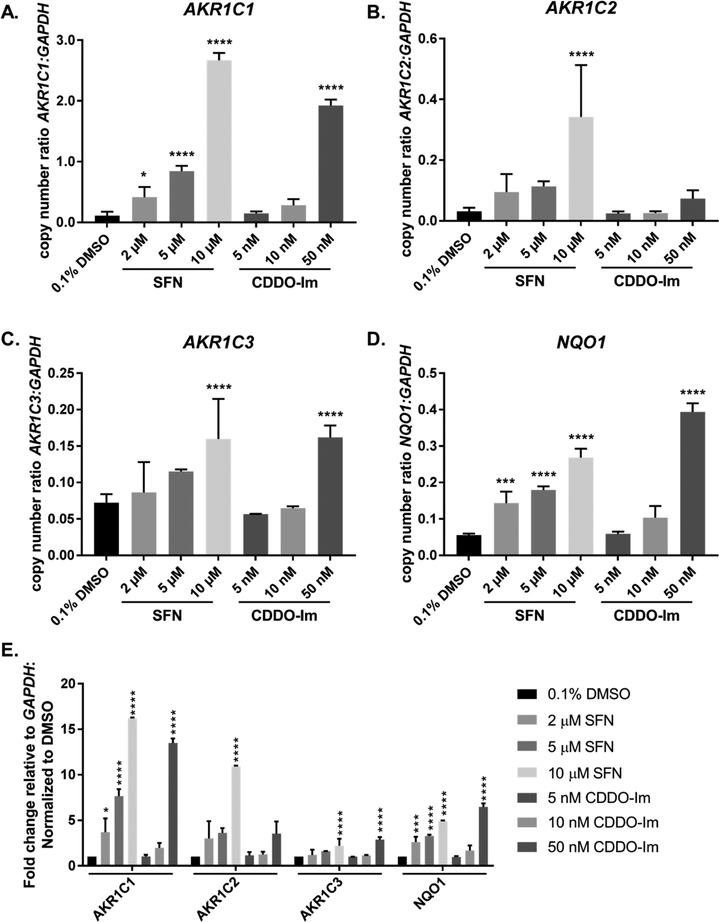

Effect of NRF2 Activation on Expression of ARE-Regulated Genes in HBEC3-KT Cells.

We next characterized two widely studied activators of NRF2, SFN and CDDO-Im, for their ability to induce AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 at the mRNA and protein level in immortalized HBEC3-KT cells. Previous studies have reported that AKR1C1–1C3 are subject to greater fold changes (4.8–39-fold increases) following NRF2 activation than NQO1 (1.2–4.8-fold increases) in immortalized human keratinocytes and human breast epithelial cells.13,14 However, the effects of NRF2 activators in immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells have yet to be determined.

We first conducted time courses to optimize treatment conditions for HBEC3-KT cells and NRF2 activators. We tested AKR1C1 and NQO1 transcript levels at various time points up to 48 h following treatment with 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im (data not shown). Maximal induction of our chosen ARE-driven genes was observed after 16 h of incubation with both activators. Dose–response curves were constructed with seven concentrations of each activator: 1–100 μM SFN and 5–5000 nM CDDO-Im, using 0.1% DMSO as a vehicle control. A bell-shaped dose–response curve was observed with SFN suggesting that this agent is cytotoxic and a bimodal distribution was observed with CDDO-Im. We show results from 2–10 μM SFN and 5–50 nM CDDO-Im treatments because the greatest changes in gene transcription were observed at 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im (Figure 6A–E).

Figure 6.

Effect of NRF2 activators on AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 expression in HBEC3-KT cells. HBEC3-KT cells were exposed to multiple doses of SFN treatment (2–10 μM) and CDDO-Im (5–50 nM) for 16 h. Quantitative RT-PCR was utilized to quantify mRNA levels of AKR1C1–1C3 (A–C, E) and NQO1 (D, E) expressed as copy number normalized to human GAPDH. Bar graphs show mean copy number ± SD of three independent experiments. To assess the effect of NRF2 activators on the absolute expression level of each gene, a one-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed. Symbols indicate a statistically significant difference in gene expression from cells treated with 0.1% DMSO as vehicle control (* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001; **** p ≤ 0.0001).

These data show that AKR1C1 was the most inducible gene upon NRF2 activation at both the absolute levels (copy number normalized to GAPDH) and relative levels (normalized to vehicle control, 0.1% DMSO) in HBEC3-KT (Figure 6A,E). The changes in gene expression were statistically significant across all treatment groups (2–10 μM SFN and 5–50 nM CDDO-Im). AKR1C1 was subject to a 16.2-fold increase with 10 μM SFN and a 13.5-fold increase with 50 nM CDDO-Im (Figure 6A,E). AKR1C2 also was subject to large fold increases with NRF2 activators, 11.1-fold and 2.2-fold increases were observed with 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im, respectively (Figure 6B,E). Despite AKR1C3 being highly responsive to NRF2 activators in other human cell lines (up to 27-fold increase), AKR1C3 transcripts were only induced 2.2-fold following treatement with 10 μM SFN and 2.9-fold following treatment with 50 nM CDDO-Im in HBEC3-KT cells (Figure 6C,E).13,14

By contrast NQO1 expression was less sensitive to NRF2 activators compared with AKR1C1–1C3. The mRNA for NQO1 showed approximately 4.9-fold and 6.5-fold increases with SFN and CDDO-Im, respectively (Figure 6D,E). These increases were statistically significant. Interestingly, basal and induced levels of NQO1 were much lower than AKR1C1 (Figure 6A,D). Copy number of NQO1 was approximately only 50% of that of AKR1C1 under noninduced conditions and only 10% following 10 μM SFN treatment.

We next measured AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 protein expression and NQO1 enzyme activity in HBEC3-KT cells following treatment with SFN and CDDO-Im to validate changes in gene expression at the functional level. For immunoblot analysis, HBEC3-KT cells were treated with doses of NRF2 activators which corresponded to maximal changes in transcript level (10 μM SFN, 50 nM CDDO-Im). Time courses (0–48 h) were conducted which determined that maximal levels of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 proteins were achieved 24 h after treatment with SFN or CDDO-Im and remained stable until 48 h (data not shown). Both 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im led to upregulation of NRF2 within the nucleus, as expected (Figure 7A). Consistent with the mRNA induction studies, the immunoblot shows that both activators increased AKR1C1/2, AKR1C3, and NQO1 protein levels in the cytosol (Figure 7A). AKR1C1/2 levels were 2.5-fold and 2.6-fold higher following treatment with 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im, respectively; AKR1C3 levels were 2.2-fold and 1.8-fold higher from 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im treatment, respectively; and NQO1 levels were 2.3-fold and 2.2-fold higher from 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im treatment, respectively. NQO1 enzyme activity measurements were in accordance with the immunoblot results and we found that 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im led to a 2.1-fold and 2.2-fold increase in NQO1 activity, respectively (Figure 7C–D). This is much lower than the 4.9 to 6.5-fold increases observed at the qPCR level.

Figure 7.

Protein levels of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 are increased by NRF2 activators. HBEC3-KT cells were exposed to the doses of NRF2 activators that led to maximal upregulation at the mRNA level: 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im. Immunoblots confirmed that AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 were upregulated in the cytosol, while NRF2 levels increased in the nucleus (A). Blots are representative of three independent experiments which were quantified through densitometry normalized to loading control (B). Relative levels of each protein were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to assess the difference in gene expression due to NRF2 activators. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the A549 wt cell line (*p ≤ 0.05). NQO1 enzyme activity assays revealed a dose–response relationship as SFN (C) or CDDO-Im (D) concentrations were increased. Plots of NQO1 activity are mean ± SD for each treatment (n = 4).

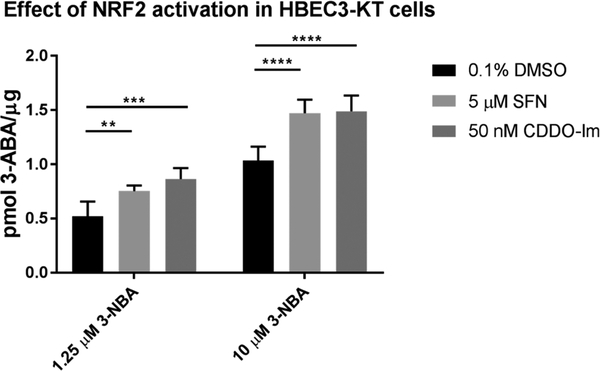

Effect of NRF2 Activation on 3-NBA Toxication.

After optimizing the induction of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 following NRF2 activator treatment, we monitored 3-ABA formation in vitro with low and high doses of 3-NBA (1.25 μM and 10 μM 3-NBA, respectively). Experiments were conducted under the same conditions as the Prochaska assay because they were optimized to produce the highest enzyme activity. Maximal changes in 3-ABA formation were observed by 16 h following treatment with 5 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im and were normalized to protein. Athough 3-NBA metabolites are electrophilic, treatment with 3-NBA did not activate NRF2 and did not cause a significant upregulation of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 during this period (Figure S4).

Following 48 h induction with 5 μM SFN, 3-ABA formation was increased by 44% (±10.1%) and 40% (±14.5%) following exposure to a low dose (1.25 μM) and high dose (10 μM) of 3-NBA, respectively (Figure 8). Meanwhile, induction with 50 nM CDDO-Im led to 60% (±19.0%) and 42% (±15.1%) increases in total 3-ABA formation following exposure to a low dose (1.25 μM) and high dose (10 μM) of 3-NBA, respectively. Increases in 3-ABA formation were consistent across multiple doses of 3-NBA: we tested four doses between 1.25–10 μM 3-NBA, data not shown.

Figure 8.

NRF2 activators increased formation of 3-ABA in HBEC3-KT cells. Determination of the metabolic activation of 3-NBA to 3-ABA in HBEC3-KT due to 5 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im. Cells were exposed to NRF2 activators for 48 h prior to 3-NBA exposure. The intrinsic fluorescence of 3-ABA (λex 520 nm, λem 650 nm) was used to detect the final reduction product, 3-ABA following 16 h of exposure to 1.25 or 10 μM 3-NBA. Values are expressed as mean ± SD, and data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to assess the difference in 3-ABA formation due to NRF2 induction within each 3-NBA treatment group. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from cells treated with 0.1% DMSO as vehicle control during the 48 h induction period (*** p ≤ 0.001; **** p ≤ 0.0001). Experiments were repeated four independent times (n = 4).

The formation of 3-ABA reported as pmol/μg protein levels are not directly comparable between the A549 and HBEC3-KT cell lines (Figure 4 vs Figure 8). The A549 data were collected at an earlier time point so that measured fluorescence was linear with time and within the range of the calibration curve constructed with an authentic 3-ABA standard. By contrast HBEC3-KT cells were plated at a much greater density and required more time to attach to the plates. When data were normalized as pmol 3-ABA formed per hour per cell number, A549 wt cells formed 48–57% more 3-ABA than HBEC3-KT cells treated with vehicle control (Figure S5).

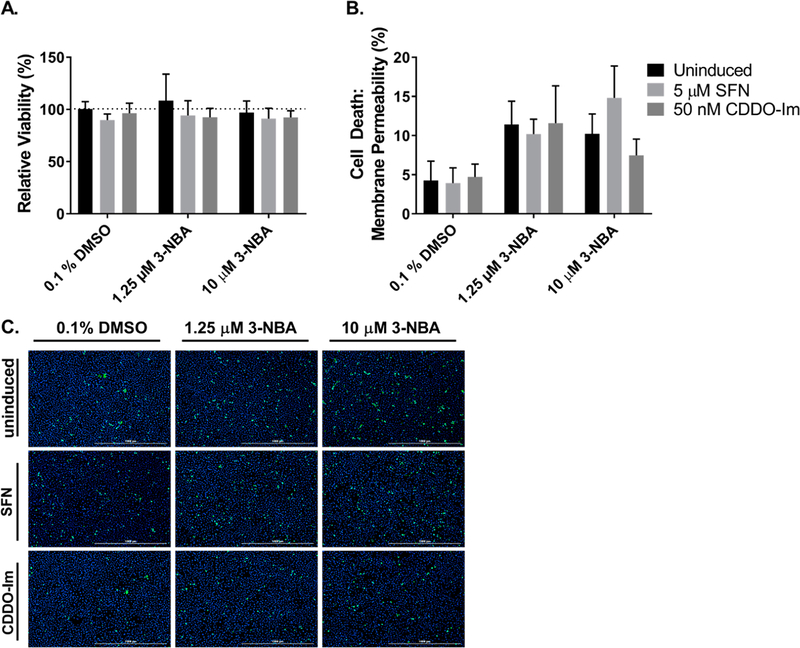

Effect of Nrf2 Activators on 3-NBA-Mediated Cytotoxicity in HBEC3-KT Cells.

Given that 3-NBA metabolites are electrophilic and can redox-cycle to generate oxidative stress, we wanted to examine whether increased NRF2 signaling had a protective effect during 3-NBA exposures in HBEC3-KT cells. Cell viability was assessed by the reduction of MTT under the same conditions as described for the assays of 3-ABA formation. Small reductions in cell viability were observed due to 1.25 μM and 10 μM of 3-NBA treatment, but these were not statistically significant. We observed that pretreatments with 5 μM SFN or 50 nM CDDO-Im had no beneficial effect in the context of 3-NBA exposures (Figure 9A). Cytotoxicity experiments were also conducted under the same conditions described above by staining cells with SYTOX Green and Hoechst after 24 h exposure to 1.25 μM and 10 μM of 3-NBA. Percentage of cell death was compared across treatments in the presence and absence of NRF2 activation by SFN and CDDO-Im. Exposure to 1.25 μM and 10 μM of 3-NBA increased cell death compared with vehicle control (0.1% DMSO), but no significant differences in cell death were observed in HBEC3-KT due to NRF2 activator treatment within each 3-NBA exposure group (Figure 9B,C).

Figure 9.

NRF2 induction did not have expected cytoprotective effects for 3-NBA exposures in HBEC3-KT cells. MTT-based cell viability was assessed in HBEC3-KT cells that underwent a 48 h exposure to NRF2 activators or vehicle control prior to exposure to 1.25 μM and 10 μM 3-NBA (A). Bar graphs show mean ± SD from three independent experiments. To measure cytotoxicity, HBEC3-KT cells underwent a 48 h exposure to NRF2 activators or vehicle control and then were treated with 1.25 μM and 10 μM 3-NBA for 24 h. Cells were stained with SYTOX Green and Hoechst at 24 h (B,C). Cell death was expressed as a percentage (# dead cells/# total cells × 100%). Bar graphs show mean ± SD of n = 3/group (B). Data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with a posthoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to assess the difference in viability or cell death within each 3-NBA treatment group due to NRF2 activator treatment. We did not observe statistically significant differences from the vehicle treatment (0.1% DMSO).

DISCUSSION

Among the human genes regulated by NRF2, AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 are consistently the most overexpressed in response to pharmacological activators of NRF2 and by activation of NRF2 by KEAP1 knockdown.13,14 The metabolic activation of 3-NBA requires nitroreduction by these enzymes in human lung cells where 34% of 3-NBA nitroreduction is attributed to AKR1C1–1C3 and up to 40% is attributed to NQO1.10 Given the importance of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 nitroreductase activity, we sought to determine the role of NRF2-KEAP1 signaling on 3-NBA toxication in vitro as measured by 3-ABA formation, cell viability, and cytotoxicity in two human lung cell lines: A549 cells that harbor somatic mutations in KEAP1 and epigenetic silencing of its promoter which lead to high consititutive NRF2 expression33 and HBEC3-KT cells with wildtype KEAP1 that are sensitive to NRF2 activators.

We first quantified the expression of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1 in A549 cells that possessed heterozygous or homozygous knockout of NRF2. We found that AKR1C1–1C3 were most sensitive to NRF2 knockout and that NRF2 signaling was essential for their transcription. Both mRNA and protein levels of AKR1C1–1C3 were difficult to detectin the A549 NRF2-KO cell line. By contrast 30% of NQO1 transcript levels and enzyme activity remained in the absence of NRF2 suggesting that other transcription factors may control its constitutive expression (e.g., AP-1 or AP-2).36 This observation differs from Nrf 2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts which lack measurable Nqo1 mRNA or protein levels, suggesting that the murine models may not accurately predict NRF2 regulation of NQO1 in humans.37 We observed discrepancies in the mRNA and protein levels of AKR1C2–1C3 and NQO1 in NRF2-Het cell lines in which mRNA levels were not significantly reduced while we were able to detect decreases at the protein and enzyme activity levels. This could be due to differences in mRNA transcript and protein stability, or we could be measuring mRNA splice variants that are not translated to functional protein.

We found decreases of 52–53% and 72–80% in 3-NBA activation due to heterozygous and homozygous NRF2 knockout, respectively. Homozygous knockout of NRF2 was deleterious in the context of high exposures to 3-NBA, and we observed decreased viability and increased cell death following exposure to 10 μM 3-NBA. This is expected given that the NRF2-KEAP1 axis plays a pivotal role in regulating the redox status of cells. However, it was surprising that no differences in viability and cell death were observed between A549 wt and NRF2-Het cells following exposure to 3-NBA. This finding is significant because it indicates that constitutively elevated NRF2 activity in “wildtype” A549 cells did not offer any more protection from 3-NBA compared to intermediate levels of NRF2 in the heterozygous knockout.

We also evaluated 3-NBA activation in HBEC3-KT cells in the presence of NRF2 activators (SFN, CDDO-Im) to better understand how pharmacological activation of NRF2 may affect 3-NBA toxication. Interestingly, AKR1C1 expression gave the largest response to NRF2 activation, indicating that it is an excellent biomarker of NRF2 activity in this cell line (16.1-fold increase and 13.5-fold increase for 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im, respectively). AKR1C3 fold changes were quite modest by comparsion (2.2-fold increase and 2.8-fold increase for 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im, respectively). By contrast, NQO1 transcripts changed by 4.9-fold and 6.5-fold in response to 10 μM SFN and 50 nM CDDO-Im. Functional increases in protein level ranged from 1.8-fold to 2.6-fold for AKR1C1–1C3 and 2.2-fold for NQO1. It is well appreciated that mRNA transcript levels do not always accurately predict protein levels,38,39 but these changes in protein were sufficient to increase total 3-NBA bioactivation by 40–60%. Our studies showed that 3-NBA activation could be exacerbated with NRF2 activators.

Although increased bioactivation of 3-NBA is expected to be deleterious since this would lead to DNA adduct formation, we predicted that NRF2 activators would decrease cytotoxicity in HBEC3-KT cells exposed to 3-NBA given that 3-NBA promotes oxidative stress.40,41 Indeed, such activators have been previously shown to ameliorate losses in viability due to oxidative stress.42 We found that NRF2 activators did not change cell viability or cytotoxicity following exposure to 3-NBA. This suggests that either basal levels of NRF2 were sufficient to protect against cytotoxic effects of 3-NBA in human bronchial epithelial cells, or that 3-NBA did not generate sufficient levels of oxidative stress to perturb HBEC3-KT cells.

The majority of data in the field suggests that NRF2 activation may reduce cancer incidence and tumor burden which has led to the development of NRF2 activators as chemopreventive agents.43 SFN has been successfully used to protect against chemical-induced carcinogenesis in multiple organs in mice.44,45 Conversely, lungs of NRF2 knockout mice show increased DNA adducts from benzo[a]pyrene and diesel exhaust exposure.46,47 However, these data are difficult to evaluate in the context of 3-NBA metabolism in humans because none of the murine Akr1c genes are orthologs of the human genes and their nitroreductase activity has not yet been evaluated.48 Numerous microarray analyses of Nrf2-target genes have been reported, but clear evidence that Nrf2 regulates Akr1c family members in the mouse does not exist. Other key components of the ARE-gene battery differ in humans: glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are highly upregulated in mice but are not upregulated by NRF2 induction in humans, which could have profound effects on detoxication of xenobiotics.14,49

In a randomized clinical trial in China (NCT 01437501), a broccoli sprout beverage enriched in SFN is being evaluated for its ability to cause a sustained detoxication of airborne pollutants and reduce the incidence of environmental lung cancer.43 This study is promising because it revealed an increase in benzene and acrolein mercapturic acid conjugates in the treated group, which would be consistent with the upregulation of glutathione synthesis genes and enhanced detoxication of these airborne carcinogens. However, enhanced detoxification was not observed for all carcinogens measured and this trial did not measure biomarkers of diesel exhaust exposure and effect, such as 1-aminopyrene-Hb adducts.50

More work is required to quantify DNA adducts in humans following exposure to NRF2 activators and NO2-PAHs. 3-ABA formation was used as a readout of total 3-NBA toxication in this study, but multiple metabolites promote DNA adduct formation. The hydroxylamino-intermediate, N-hydroxy-3-aminobenzanthrone (N-OH-3-ABA) can be intercepted by sulfonation or acetylation, creating a good leaving group to form the intermediate nitrenium or carbenium ion which binds DNA.7–9,51 3-ABA can also be oxidized back to N-OH-3-ABA or can be directly activated by peroxidases to yield either a nitrenium or carbenium ion which contributes to DNA adduct formation.52 Thus, end-point measurements of 3-ABA formation may provide an underestimate of 3-NBA activation driven by NRF2 signaling and a future direction would be to measure the 3-NBA-derived DNA adduct levels.

Our work highlights the possibility that NRF2 activation may have deleterious consequences with respect to carcinogen metabolism: NRF2 upregulates the antioxidant capacity of the cell and is protective against compounds that require Phase II conjugation for detoxication, but it may also drive toxication of a subset of NO2-PAH carcinogens that are not detoxified by Phase II enzymes. Notably, 3-NBA metabolites do not form glutathione conjugates, rather they undergo sulfonation or acetylation which promotes DNA adduct formation.7 This raises questions about whether the use of NRF2-targeted chemoprevention therapies may enhance the metabolic activation of specific environmental carcinogens.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This publication was made possible by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) Foundation Pharmacology/Toxicology Pre-Doctoral Fellowship and T32-ES-019851 (to J.R.M.) and by P30-ES013508 and R01-ES029294 (to T.M.P.) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH, DHHS. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS or NIH. We thank the Medical Research Council for funding (grant MR/N009851/1, awarded to J.D.H. and T.M.P.) and Cancer Research UK (grant C52419/A22869, awarded to L.D.L.V.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00399.

We report the primers utilized in qPCR experiments; additional studies which verified that NRF2 levels were unaltered in A549 cell line variants in the presence of NRF2 activators; and studies which demonstrated that 3-NBA exposures failed to induce upregulation of AKR1C1–1C3 and NQO1. (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Enya T, Suzuki H, Watanabe T, Hirayama T, and Hisamatsu Y (1997) 3-Nitrobenzanthrone, a Powerful Bacterial Mutagen and Suspected Human Carcinogen Found in Diesel Exhaust and Airborne Particulates. Environ. Sci. Technol 31 (10), 2772–2776. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Takamura-Enya T, Suzuki H, and Hisamatsu Y (2006) Mutagenic activities and physicochemical properties of selected nitrobenzanthrones. Mutagenesis 21 (6), 399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Attfield MD, Schleiff PL, Lubin JH, Blair A, Stewart PA, Vermeulen R, Coble JB, and Silverman DT (2012) The Diesel Exhaust in Miners study: a cohort mortality study with emphasis on lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 104 (11), 869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Garshick E, Schenker MB, Munoz A, Segal M, Smith TJ, Woskie SR, Hammond SK, and Speizer FE (1987) A case-control study of lung cancer and diesel exhaust exposure in railroad workers. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis 135 (6), 1242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Silverman DT, Samanic CM, Lubin JH, Blair AE, Stewart PA, Vermeulen R, Coble JB, Rothman N, Schleiff PL, Travis WD, Ziegler RG, Wacholder S, and Attfield MD (2012) The Diesel Exhaust in Miners study: a nested case-control study of lung cancer and diesel exhaust. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 104 (11), 855–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Baan RA, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Guha N, Loomis D, and Straif K (2012) Carcinogenicity of diesel-engine and gasoline-engine exhausts and some nitroarenes. Lancet Oncol. 13 (7), 663–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Arlt VM, Glatt H, Muckel E, Pabel U, Sorg BL, Schmeiser HH, and Phillips DH (2002) Metabolic activation of the environmental contaminant 3-nitrobenzanthrone by human acetyltransferases and sulfotransferase. Carcinogenesis 23 (11), 1937–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Arlt VM, Stiborova M, Hewer A, Schmeiser HH, and Phillips DH (2003) Human enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of the environmental contaminant 3-nitrobenzanthrone: evidence for reductive activation by human NADPH:cytochrome p450 reductase. Cancer Res. 63 (11), 2752–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Arlt VM, Sorg BL, Osborne M, Hewer A, Seidel A, Schmeiser HH, and Phillips DH (2003) DNA adduct formation by the ubiquitous environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its metabolites in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 300 (1), 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Murray JR, Mesaros CA, Arlt VM, Seidel A, Blair IA, and Penning TM (2018) Role of Human Aldo-Keto Reductases in the Metabolic Activation of the Carcinogenic Air Pollutant 3-Nitrobenzanthrone. Chem. Res. Toxicol 31 (11), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Guise CP, Abbattista MR, Singleton RS, Holford SD, Connolly J, Dachs GU, Fox SB, Pollock R, Harvey J, Guilford P, Donate F, Wilson WR, and Patterson AV (2010) The bioreductive prodrug PR-104A is activated under aerobic conditions by human aldo-keto reductase 1C3. Cancer Res. 70 (4), 1573–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Burczynski ME, Harvey RG, and Penning TM (1998) Expression and characterization of four recombinant human dihydrodiol dehydrogenase isoforms: oxidation of trans-7, 8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene to the activated o-quinone metabolite benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-dione. Biochemistry 37 (19), 6781–6790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Agyeman AS, Chaerkady R, Shaw PG, Davidson NE, Visvanathan K, Pandey A, and Kensler TW (2012) Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling of KEAP1 disrupted and sulforaphane-treated human breast epithelial cells reveals common expression profiles. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 132 (1), 175–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).MacLeod AK, McMahon M, Plummer SM, Higgins LG, Penning TM, Igarashi K, and Hayes JD (2009) Characterization of the cancer chemopreventive NRF2-dependent gene battery in human keratinocytes: demonstration that the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway, and not the BACH1-NRF2 pathway, controls cytoprotection against electrophiles as well as redox-cycling compounds. Carcinogenesis 30 (9), 1571–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Itoh K, Igarashi K, Hayashi N, Nishizawa M, and Yamamoto M (1995) Cloning and characterization of a novel erythroid cell derived CNC family transcription factor heterodimerizing with the small Maf family proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol 15, 4184–4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Itoh K, Tong KI, and Yamamoto M (2004) Molecular mechanism activating Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in regulation of adaptive response to electrophiles. Free Radical Biol. Med 36, 1208–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Tebay LE, Robertson H, Durant ST, Vitale SR, Penning TM, Dinkova-Kostova AT, and Hayes JD (2015) Mechanisms of activation of the transcription factor Nrf2 by redox stressors, nutrient cues, and energy status and the pathways through which it attenuates degenerative disease. Free Radic Biol. Med 88 (Pt B), 108–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T, Igarashi K, and Yamamoto M (2004) Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell. Biol 24 (16), 7130–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wakabayashi N, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Kang MI, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, and Talalay P (2004) Protection against electrophile and oxidant stress by induction of the phase 2 response: fate of cysteines of the Keap1 sensor modified by inducers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 101 (7), 2040–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, Wakabayashi J, Maher J, Motohashi H, and Yamamoto M (2008) Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 in determining Nrf2 activity. Mol. Cell. Biol 28 (8), 2758–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, Yamamoto M, and Nabeshima Y (1997) An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 236 (2), 313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tong KI, Katoh Y, Kusunoki H, Itoh K, Tanaka T, and Yamamoto M (2006) Keap1 recruits Neh2 through binding to ETGE and DLG motifs: characterization of the two-site molecular recognition model. Molecular and cellular biology 26 (8), 2887–2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kensler TW, and Wakabayashi N (2010) Nrf2: friend or foe for chemoprevention? Carcinogenesis 31 (1), 90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yates MS, Tauchi M, Katsuoka F, Flanders KC, Liby KT, Honda T, Gribble GW, Johnson DA, Johnson JA, Burton NC, Guilarte TR, Yamamoto M, Sporn MB, and Kensler TW (2007) Pharmacodynamic characterization of chemopreventive triterpenoids as exceptionally potent inducers of Nrf2-regulated genes. Mol. Cancer Ther 6 (1), 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Singh A, Misra V, Thimmulappa RK, Lee H, Ames S, Hoque MO, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Sidransky D, Gabrielson E, Brock MV, and Biswal S (2006) Dysfunctional KEAP1–NRF2 Interaction in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS Medicine 3 (10), e420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wang X-J, Sun Z, Villeneuve NF, Zhang S, Zhao F, Li Y, Chen W, Yi X, Zheng W, Wondrak GT, Wong P, and Zhang DD (2008) Nrf2 enhances resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, the dark side of Nrf2. Carcinogenesis 29 (6), 1235–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ramirez RD, Sheridan S, Girard L, Sato M, Kim Y, Pollack J, Peyton M, Zou Y, Kurie JM, Dimaio JM, Milchgrub S, Smith AL, Souza RF, Gilbey L, Zhang X, Gandia K, Vaughan MB, Wright WE, Gazdar AF, Shay JW, and Minna JD (2004) Immortalization of human bronchial epithelial cells in the absence of viral oncoproteins. Cancer Res. 64 (24), 9027–9034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Arlt VM, Glatt H, Muckel E, Pabel U, Sorg BL, Seidel A, Frank H, Schmeiser HH, and Phillips DH (2003) Activation of 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its metabolites by human acetyltransferases, sulfotransferases and cytochrome P450 expressed in Chinese hamster V79 cells. Int. J. Cancer 105 (5), 583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Schmeiser HH, Furstenberger G, Takamura-Enya T, Phillips DH, and Arlt VM (2009) The genotoxic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its reactive metabolite N-hydroxy-3-amino-benzanthrone lack initiating and complete carcinogenic activity in NMRI mouse skin. Cancer Lett. 284 (1), 21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Torrente L, Sanchez C, Moreno R, Chowdhry S, Cabello P, Isono K, Koseki H, Honda T, Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT, and de la Vega L (2017) Crosstalk between NRF2 and HIPK2 shapes cytoprotective responses. Oncogene 36 (44), 6204–6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bauman DR, Steckelbroeck S, Peehl DM, and Penning TM (2006) Transcript Profiling of the Androgen Signal in Normal Prostate, Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, and Prostate Cancer. Endocrinology 147 (12), 5806–5816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Fahey JW, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Stephenson KK, and Talalay P (2004) The ″Prochaska″ microtiter plate bioassay for inducers of NQO1. Methods Enzymol. 382, 243–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wang R, An J, Ji F, Jiao H, Sun H, and Zhou D (2008) Hypermethylation of the Keap1 gene in human lung cancer cell lines and lung cancer tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 373 (1), 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Homma S, Ishii Y, Morishima Y, Yamadori T, Matsuno Y, Haraguchi N, Kikuchi N, Satoh H, Sakamoto T, Hizawa N, Itoh K, and Yamamoto M (2009) Nrf2 enhances cell proliferation and resistance to anticancer drugs in human lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 15 (10), 3423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhang B, Xie C, Zhong J, Chen H, Zhang H, and Wang X (2014) A549 cell proliferation inhibited by RNAi mediated silencing of the Nrf2 gene. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng 24 (6), 3905–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Joseph P, and Jaiswal AK (1994) NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 (DT diaphorase) specifically prevents the formation of benzo[a]pyrene quinone-DNA adducts generated by cytochrome P4501A1 and P450 reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 91 (18), 8413–8417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Nioi P, McMahon M, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, and Hayes JD (2003) Identification of a novel Nrf2-regulated antioxidant response element (ARE) in the mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene: reassessment of the ARE consensus sequence. Biochem. J 374 (Pt 2), 337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Liu Y, Beyer A, and Aebersold R (2016) On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell 165 (3), 535–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Vogel C, and Marcotte EM (2012) Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet 13 (4), 227–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Nagy E, Adachi S, Takamura-Enya T, Zeisig M, and Moller L (2007) DNA adduct formation and oxidative stress from the carcinogenic urban air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its isomer 2-nitrobenzanthrone, in vitro and in vivo. Mutagenesis 22 (2), 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Murata M, Tezuka T, Ohnishi S, Takamura-Enya T, Hisamatsu Y, and Kawanishi S (2006) Carcinogenic 3-nitrobenzanthrone induces oxidative damage to isolated and cellular DNA. Free Radical Biol. Med 40 (7), 1242–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sohel MMH, Amin A, Prastowo S, Linares-Otoya L, Hoelker M, Schellander K, and Tesfaye D (2018) Sulforaphane protects granulosa cells against oxidative stress via activation of NRF2-ARE pathway. Cell Tissue Res. 374 (3), 629–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Egner PA, Chen JG, Zarth AT, Ng DK, Wang JB, Kensler KH, Jacobson LP, Muñoz A, Johnson JL, Groopman JD, Fahey JW, Talalay P, Zhu J, Chen TY, Qian GS, Carmella SG, Hecht SS, and Kensler TW (2014) Rapid and sustainable detoxication of airborne pollutants by broccoli sprout beverage: results of a randomized clinical trial in China. Cancer Prev. Res 7, 813–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Dinkova-Kostova AT, Fahey JW, Kostov RV, and Kensler TW (2017) KEAP1 and Done? Targeting the NRF2 Pathway with Sulforaphane. Trends in food science & technology 69 (Pt B), 257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Fahey JW, Haristoy X, Dolan PM, Kensler TW, Scholtus I, Stephenson KK, Talalay P, and Lozniewski A (2002) Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo[a]-pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99(11), 7610–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Aoki Y, Hashimoto AH, Amanuma K, Matsumoto M, Hiyoshi K, Takano H, Masumura K-i., Itoh K, Nohmi T, and Yamamoto M (2007) Enhanced spontaneous and benzo[a]pyrene-induced mutations in the lung of Nrf2-deficient gpt delta mice. Cancer Res. 67, 5643–5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Aoki Y, Sato H, Nishimura N, Takahashi i S., Itoh K, and Yamamoto M (2001) Accelerated DNA adduct formation in the lung of the Nrf2 knockout mouse exposed to diesel exhaust. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 173, 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Velica P, Davies NJ, Rocha PP, Schrewe H, Ride JP, and Bunce CM (2009) Lack of functional and expression homology between human and mouse aldo-keto reductase 1C enzymes: implications for modelling human cancers. Mol. Cancer 8, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Zhang Y, Gonzalez V, and Xu MJ (2002) Expression and regulation of glutathione S-transferase P1–1 in cultured human epidermal cells. J. Dermatol. Sci 30 (3), 205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).van Bekkum YM, Scheepers PT, van den Broek PH, Velders DD, Noordhoek J, and Bos RP (1997) Determination of hemoglobin adducts following oral administration of 1-nitropyrene to rats using gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., Biomed. Appl 701, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Bieler CA, Wiessler M, Erdinger L, Suzuki H, Enya T, and Schmeiser HH (1999) DNA adduct formation from the mutagenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Mutat. Res., Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen 439 (2), 307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Arlt VM, Hewer A, Sorg BL, Schmeiser HH, Phillips DH, and Stiborova M (2004) 3-aminobenzanthrone, a human metabolite of the environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone, forms DNA adducts after metabolic activation by human and rat liver microsomes: evidence for activation by cytochrome P450 1A1 and P450 1A2. Chem. Res. Toxicol 17 (8), 1092–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.