Abstract

This paper examines patterns and trends in racial inequality in poverty and affluence over the 1959 to 2015 period. Analyzing data from decennial censuses and the American Community Survey, I find that that disparities have generally narrowed over the period. Nevertheless, considerable disparities remain, with whites least likely to be poor and Asians most likely to be affluent on the one hand, and blacks and American Indians much more likely to be poor and less likely to be affluent on the other—and Hispanics somewhat in between. Sociodemographic characteristics, such as education, family structure, and nativity explain some of the disparities—and an increasing proportion over the 1959 to 2015 period, indicative of the growing importance of disparities in human capital, the immigrant incorporation process, and the interaction between economic conditions and cultural shifts in attitudes towards marriage in explaining racial inequality in poverty and affluence. There also are still significant portions of the gaps that remain unexplained, especially for blacks and American Indians. The presence of this unexplained gap indicates that other factors are still at work in producing these disparities, though their effects have declined over time.

Keywords: poverty, affluence, race and ethnicity, inequality

Few topics have received as much attention in recent years as the prevalence and nature of racial inequality in the United States. Racial inequality in policing and punishment, for example, was the impetus of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013. The production and enormous success of the movie The Black Panther, released in 2018, highlighted previous inequality in representation in the movies and media. One of the reasons that these issues continue to resonate is that the material circumstances of the U.S. population historically varied–and continue to vary–by race and ethnicity. For example, in 1959, the first year of the official times series, over half of all blacks were poor, compared to fewer than 1 in 5 of whites. Poverty rates decreased for both groups during the economic boom of the 1960s, but since the early 1970s poverty has mainly fluctuated with the economic cycle, and considerable disparities remain, such that by 2015, 24 percent of blacks and 9 percent of non-Hispanic whites were poor (U.S. Census Bureau 2016a).

There is considerable variation in the incidence of poverty across other racial and ethnic groups as well. Poverty rates among American Indians are about as high as among African Americans, poverty rates among Hispanics are only modestly lower, while the poverty rate among Asians more closely resembles that of whites (U.S. Census Bureau 2016a). It is likely that a variety of factors help explain patterns across these different groups, including the prevalence of racial discrimination, a legacy of past inequality, the immigration process (principally for Asians and Hispanics), differences in human capital and other sociodemographic characteristics, and social and spatial isolation (Iceland 2017).

Notably, while racial and ethnic disparities in poverty have been documented for some time, there has been considerably less analogous research on racial gaps in the prevalence of affluence, and how these gaps have changed over time. Understanding patterns of affluence are important because, as Richard Reeves (2017) has argued, affluent Americans have considerable control over many kinds of resources, not the least being community amenities and institutions, such as local public schools. Understanding patterns of affluence is all the more important given the growth of income inequality in the United States. Such inequality has been associated stagnant or declining living standards for those at the bottom of the income distribution along with large gains for those at the top (Piketty 2014). Many thus argue we are living in an “age of extremes” (Massey 1996). While we know that the poverty rates of many minority groups have been stagnant in recent years, we know relatively little about the extent to which these groups are part of the affluent class, and how this might have changed over time. Are patterns of poverty and affluence symmetrical, such that groups with higher poverty rates consistency have lower rates of affluence? There is reason to believe that this is not necessarily so, as studies have documented differences in income inequality within groups (Kochhar and Cilluffo 2018).

This paper further investigates the extent to which individual and family-level characteristics help explain racial and ethnic differences in poverty and affluence, and how the influence of these characteristics might have changed over the 1959 to 2015 period. While other data would be needed to examine all of the deep structural roots of racial disparities in poverty and affluence, the analysis here will help ascertain the role of important sociodemographic correlates of poverty—such as educational attainment, family structure, and nativity—in explaining racial disparities. This will provide important information on whether, for example, educational disparities help drive differences among some groups, such as between whites and Hispanics, and whether the significance of these factors have grown or diminished over time. The study will also shed light on whether the factors have a symmetrical effect on poverty and affluence.

In short, this paper is guided by the following questions:

What patterns and trends in poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity do we see over the 1959 to 2015 period?

How has the relatively likelihood of poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity changed?

To what extent do family- and individual-level characteristics help explain differences in the prevalence in poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity, and how have these associations changed over time?

To answer these questions, this study relies on data from the 1960 to 2000 decennial censuses and the 2010 and 2015 American Community Surveys. I calculate rates of poverty and affluence for whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians. I then investigate, using logistic regressions, the relative likelihood of poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity, and finally, with a decomposition analysis, the extent to which individual- and family-level characteristics explain disparities at different points in time. In doing so, this study helps shed light on the evolving nature of racial and ethnic inequality in poverty and affluence in the United States in this era of profound demographic and economic change.

Background

Overall trends in poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity

Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of poverty have been widely documented. Using the official U.S. poverty measure, in 2015, for example, the poverty rate of non-Hispanic whites was 9 percent, compared to 11 percent among Asians, 21 percent among Hispanics, 24 percent among blacks, and 26 percent among American Indians (U.S. Census Bureau 2016a, 2016c). There has been a modest narrowing of poverty differentials over time, as the non-Hispanic white poverty rate has inched up since the 1970s, while those of blacks, Hispanics, and Asians are a little lower—though among all groups there are considerable fluctuations in poverty with the economic cycle (U.S. Census Bureau 2016a).

Less has been written about the prevalence of affluence, and indeed there is no official government measure of affluence in the United States, nor a standard way to measure it in the literature. It is not uncommon for studies to examine people at different percentiles of the income distribution (Piketty and Saez 2003; Murray 2012; Reeves 2017). Others have used absolute measures of affluence which are based on an unchanging benchmark over time, much like the official poverty measure (Rank and Hirscl 2001; Danziger and Gottschalk 1995; Rothwell and Massey 2010). Danziger and Gottschalk (1995) document a significant increase in affluence over time.

The few studies that have looked at patterns of affluence by race and ethnicity find considerable disparities. Among these, Rank and Hirschl (2001), using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), take a life course approach to examine the probability of experience a year of affluence (defined as family incomes at least 10 times the poverty threshold) among whites and blacks. They find that only about 13 percent of blacks will experience at least one year of affluence over their lifetime, compared to 55 percent of whites. Their subsequent work confirmed that there was considerable differential in the likelihood of affluence by race (Hirschl and Rank 2015).

Explanations for differences in poverty and affluence

There are a number of broad explanations of racial disparities in poverty and affluence. Among these are racial discrimination, the legacy of historical inequalities, differences in human, social, and cultural capital, immigration-related process (such as immigrant selection and generational incorporation), social and spatial isolation, and culture factors, among others (e.g., Alba and Nee 2003; Bourdieu 1977; Charles and Guryan 2008; Loury 1977, 2002; Iceland 2017; Massey 2007; Massey and Denton 1993; Patterson and Fosse 2015; Wilson 1987). This analysis does not attempt to measure the impact of all of these; to do so would be beyond the scope possible with the data available and in the space of a journal article. Instead, using census data over a long period of time, I examine some of the important, more proximate, socio-demographic correlates of poverty, including education, family structure, and nativity status, among others. These have been shown to have significant associations with poverty, usually causally so, or at least as both a cause and reflection of poverty. Some of these also shed light on the broader perspectives described above, including human capital and immigration-related perspectives. These analyses will provide information on the extent to which these characteristics explain racial disparities, and the changes in their roles over time.

Below I begin with a discussion of the association between individual- and family-level factors and poverty and affluence. I then describe how they might help explain racial and ethnical differences in poverty and affluence over time. This is followed with a review of the previous empirical literature on these relationships, and I end the background section by detailing this study’s contribution to the literature.

The association of individual- and family-level characteristics with poverty and affluence

Among the most important individual- and family-level factors that may help explain racial and ethnic differentials in poverty and affluence are education, family structure, and nativity. I discuss these and additional factors in turn.

Education, a common marker of human capital, is strongly associated with poverty and affluence. Education helps people be more productive, and as such, more desirable to employers. Of secondary importance, attaining an educational degree also serves as a credential—a signal that an individual is meritorious and capable (Becker 1994). Indicative of the importance of education, 5 percent of the population 25 and older with a BA or greater was poor in 2015, compared to 26 percent among those without a high school degree (Proctor, Semega, and Kollar 2016).

Family structure is strongly associated with poverty (less work has been done on its association with affluence). For example, the poverty rate among married-couple families was 5 percent in 2015, compared to 28 percent among female-headed families (U.S. Census Bureau 2016b). Families with two adults are more likely two have two earners to help make ends meet. Single parents often face the challenge of finding and paying for childcare. Other factors may also help explain the higher poverty rates among single parents, such as lower average levels of education among these parents.

Nativity is also strongly associated with socioeconomic status. Immigrants tend to have higher rates of poverty than the native born, even within racial/ethnic groups (Proctor, Semega, and Kollar 2016). Higher poverty rates among the foreign born stem from a variety of factors, as the foreign-born often have lower levels of education than the native-born, they might be less likely to translate their academic credentials into good jobs, they are more likely to have limited English language proficiency, and they may have less knowledge about job market and/or lack productive social capital (Hoynes, Page, and Stevens 2006; Iceland 2013; Alba and Nee 2003).

Other individual- and family-related factors also help to explain poverty and affluence, and these are included as control variables in the analysis. For example, age is negatively associated with poverty, as earnings generally increase across the life course until retirement (Rank and Hirschl 2001). Poverty rates also are higher in the South and nonmetropolitan areas than in other areas (Thiede, Lichter, and Slack 2018). Women are more likely to experience poverty, and less likely to experience affluence, than men, for a variety of reasons, including lower levels of workforce attachment and discrimination in the labor market (Blau, Ferber, and Winkler 1998; England 2010; Rank and Hirschl 2001).

How individual and family-level factors might help explain racial and ethnic differentials in poverty and affluence

Education might help explain racial and ethnic differential in poverty and affluence because education levels vary by race and ethnicity. Asians are the mostly likely to have a B.A. or higher degree, followed by whites, blacks, and Hispanics and American Indians (the last two groups have similar levels) (U.S. Census Bureau 2016c). Low levels of education among blacks and American Indians reflect historical inequalities, as well the poor quality of many schools in neighborhoods with a high proportion of blacks and American Indians—exacerbated by racial residential segregation (Massey and Denton 1993; Snipp 1992; Snipp and Hirschman 2004).

One reason for high levels of education among Asians is the Asian immigrants are a very selective group, in that they have higher average levels of education than both people in their countries of origin and native-born Americans in the United States (Sakamoto and Kim 2013; Lee and Zhou 2014). One reason for this selectivity is that a relatively high proportion of immigrants from Asia are admitted into the U.S. on the basis of their occupational skills. In contrast, a higher proportion of Hispanics enter because they already have kin living in the United States. Immigrants who enter via the occupational skills provisions have much higher levels of education on average that those who enter on the basis of the family reunification provisions, and in part as a result of this, Hispanic immigrants are much less positively selected on education (Chiswick 1986; Feliciano 2005).

The association between family structure and poverty/affluence also likely helps explain racial disparities, given differences in marriage rates across groups: they are lowest among blacks, followed by American Indians, Hispanics, whites, and Asians, and differences generally widened over time (Raley, Sweeney, and Wandra 2015). These difference in household living arrangements could reflect racial and ethnic differences in either the average value placed on marriage (a cultural argument) and/or the relative economic security of men and women (an economic argument). Research suggests that blacks and Hispanics are more supportive of single parenthood than whites and Asians, perhaps reflecting the greater occurrence of single parenthood among the former two groups (Goldscheider and Kaufman 2006; Trent and South 1992). On the economic side, Black and Hispanic men have relatively low earnings compared to white and Asian men (Sakamoto et al. 2000; Snipp and Cheung 2016). This study cannot distinguish between the cultural and economic argument, but can nevertheless shed light on how differences in family structure more generally affect disparities in poverty and affluence. An important caveat here is that family structure might not only affect poverty, but also be affected by it. In this way, past and current disparities in income by race and ethnicity contribute to differences in family structure, which in turn can further exacerbate poverty and affluence gaps.

The possible role of nativity in explaining racial and ethnic gaps is straight forward, and has been discussed at length in the literature (e.g., Sakamoto, Goyette, and Kim 2009; Duncan, Hotz, and Trejo 2006; Iceland 2017; Perlmann 2005; Snipp and Hirschman 2004). A significant percentage of Asians and Hispanics are immigrants, and immigrants tend to have lower socioeconomic outcomes than the native-born for reasons described above, so nativity might contribute to differentials in poverty and affluence among these groups.

Among other factors included in this analysis that might help explain racial and ethnic differentials in poverty and affluence, age is negatively associated with poverty and the age structure of racial groups differs—whites are the oldest group, followed by Asians, blacks and American Indians, Hispanics, and multiracial individuals (Gao 2016). Since poverty rates also are higher in the South and nonmetropolitan areas than in other areas, to the extent that racial/ethnic groups are differentially distributed across these areas can affect disparities. American Indians, for example, are over-represented in nonmetropolitan areas (Snipp and Sandefur 1988).

It is possible that racial and ethnic groups might experience different “returns” to the individual- and family-level factors that are examined in this analysis. For example, non-Hispanic whites might receive a greater return to education than non-Hispanic blacks. The decomposition method used here focuses on whether group attributes help explain differences in poverty and affluence, but in the Results section I also speak more briefly to the issue of whether differences in returns are important in explaining broad patterns of change.

Finally, it is important to note that disparities in poverty and affluence might be explained by factors not captured in the decennial census and ACS data. These unobserved factors could include, among others: discrimination, neighborhood conditions arising out racial and ethnic segregation (such as the variation in school quality across neighborhood and physical conditions such as environmental hazards), social capital, and culture and cultural capital. To the extent that disparities in these unobserved factors might have changed, we will see a change in the unaccounted for differences in poverty and affluence by race in the analyses.

Previous Empirical Findings

There are a number of studies that have focused on the effect of individual and family-level factors on racial and ethnic disparities in income and poverty, and especially with regards to average or median earnings (e.g., Farley 1996; Hirschman and Wong 1984; Sakamoto, Wu and Tzeng 2000; Sandefur and Scott 1983; Snipp and Cheung 2016). Among the most recent, Snipp and Cheung (2016) find that some racial and ethnic gaps in earnings have declined, especially between many Asian groups and whites. Asians are in fact often advantaged, but this can be explained mainly by education and regional clustering. Other studies provide mixed findings on the extent of Asian advantage/disadvantage in earnings, with some showing no disadvantage, but others with many controls showing a small disadvantage. Generally speaking, on the one hand, nativity helps explain some of the Asian disadvantage in earnings, but Asians also have higher earnings because they have higher levels of education (Kim and Sakamoto 2010; Zeng and Xie 2004; see also Sakamoto, Goyette, and Kim 2009).

Snipp and Cheung (2016) find only a slight narrowing of gap in earnings between white and African American men, though observed characteristics play a larger role in explaining the gap over time. They attribute some of the unobserved gap to discrimination. The small narrowing of the gap and an increased role of observable characteristics is consistent with other studies, though there is some debate about the magnitude of the decline in black-white earnings and wage inequality (Couch and Daly 2002; Farley 1984; Hirschman and Wong 1984; Sakamoto, Wu, and Tzeng 2000; Western and Pettit 2005). Differences in family structure have also been found to contribute to the black-white gap in poverty (Lichter, Qian, and Crowly 2005; Thiede, Kim, and Slack 2017). However, the general association between family structure and poverty has weakened over time, as single parents are more likely to be employed than they used to (Cancian and Reed 2008; Danziger and Gottschalk 1995; Iceland 2003; Sawhill 2006).

Snipp and Cheung (2016) also find no convergence in the earnings between Hispanics and whites (see also Sakamoto, Wu, and Tzeng 2000), with education playing an important role in explaining part of the gap. This is consistent with other studies showing that Hispanics remain disadvantaged relative to whites in terms of earnings and other socioeconomic outcomes; nativity and lower levels of educational also explain at least some, but not all of the Hispanic-white earnings gap (Dávila, Mora, and Hales 2008; see Duncan and Trejo 2014).

Finally, the gap between whites and American Indians has decreased only slightly. Among American Indians, low levels of education are an important factor explaining high levels of poverty, as is spatial isolation in areas without many good jobs. A relatively high proportion of American Indian children live in single parent families as well (Snipp and Sandefur 1988; Sarche and Spicer 2008; Sandefur and Liebler 1997; Snipp 2005).

Contributions of this study

This study contributes to the above literature in several ways. First, while general patterns and trends in poverty by race and ethnicity have been well documented, the analyses provide a careful accounting of the extent to which racial and ethnic gaps in poverty have narrowed, and some of group characteristics that help explain these gaps over a long period of time (more on this point below). Second, even less is known about patterns and trends in affluence. Some studies have indicated important differentials (e.g., Rank and Hirschl 2001), but none that I am aware of have tracked trends in affluence by race and ethnicity—and is done so here for the 1959 to 2015 period. As such, this analysis examines who occupies both tails of the income distribution. Doing so is timely given substantial increases in inequality since the 1970s, the accompanying hollowing out of the middle class, and the importance of understanding racial inequalities among both the most vulnerable members of society along with those who have substantial political, economic, and social power (Reeves 2017).

Finally, using decomposition analyses, I examine the role of several individual- and family-level characteristics in explaining racial and ethnic differences in poverty and affluence. Many of these, such as education, family structure, and nativity, are thought to play important roles for different groups-- and their roles have likely have changed over time as the composition of racial and ethnic groups themselves have changed. No previous study has examined the effect of these factors at both the low and high ends of the income spectrum, so it is unknown whether they have similar effect on both. Thus, these analyses will yield a deeper understanding of racial and ethnic disparities in poverty and affluence from 1959 to 2015—a period of dramatic change in the social, economic, and demographic composition of the United States.

Data and Methods

Data

The data for these analyses come from the 1960 to 2000 decennial censuses and the 2010 and 2015 American Community Survey (ACS), compiled and harmonized as part of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS-USA) (Ruggles et al. 2015). The analysis begins with the 1960 census (which collects information on respondents’ incomes in the previous calendar year), as 1959 marks the beginning of the official poverty time series. In addition, using the absolute measure of affluence described below, only a very small proportion of people were affluent in 1949 (2 percent), and this is all more the case for minority groups (1 percent or less for all groups), which also were demographically a small proportion of the total population in 1949 before growing considerable in subsequent decades. The sample includes people in the poverty universe, which excludes people living in institutionalized group quarters and unrelated individuals under the age of 15.

While I examine change over the entire 1959 to 2015 period, some of the analyses focus on changes between 1959 and 1979, and 1980 to the present. There are conceptual and practical reasons for this choice. Conceptually, the 1960s saw the passage of major Civil Rights legislation, with increased implementation into the 1970s, such as in the form of expanded school busing. The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 saw the beginning of conservative retrenchment in several areas, including cuts in many government programs, as well as the acceleration of income inequality that began in the 1970s (Danziger and Gottschalk 1995; Gottschalk and Danziger 2005). One important practical reason to split the analyses into these two time periods is the greater consistency in racial and ethnic groups definitions beginning in 1980, especially for Asians and Hispanics, as described in more detail below. Using a different cutoff year, such as 1989, would not affect the paper’s conclusions. Racial/ethnic gaps narrowed throughout the period, and the change in the role of, say, family structure in explaining black-white poverty differences, would be evident when using 1979 or 1989 as a midpoint year.

Measuring Poverty and Affluence

I use the official poverty measure in this analysis. Briefly, the official poverty measure has two components: poverty thresholds and the definition of family income that is compared to these thresholds. The thresholds remain the same over time, updated only for inflation. The thresholds vary by family size and number of children. In 2015, the poverty threshold for a family with two parents and two children was $24,036 (Proctor, Semega, and Kollar 2016). A family and its members are considered poor if their income falls below the poverty threshold for a family of that size and composition.

Affluence is defined as family income-to-poverty ratios higher than five times the poverty threshold. For a family of two adults and two children, then, the threshold for affluence was $120,180 in 2015. While any threshold for poverty or affluence is inevitably somewhat arbitrary, this measure is reasonable in a couple of respects. In 2015, this dollar figure would place these families at a little below the 80th percentile of income ($133,525) (U.S. Census Bureau 2016d), which is close to Reeve’s (2017) definition of the upper middle class. Secondly, if we were to choose a threshold much higher, only a very small percentage of the population would be affluent in the early years of this study, given overall increases in standards of living.

I also conducted the analyses with alternative measures of poverty and affluence. While these produce different point estimates of poverty and affluence, all of these yielded conclusions on racial and ethnic differentials similar to those presented here. Among the measures I used were relative poverty and affluence, defined as families with incomes in the bottom and top decile of the income distribution in each given year. Using the top decile as a measure of affluence is common in the literature (e.g., Piketty and Saez 2003). Since relative poverty measures are sometimes based on some fraction of income below the national median (as opposed to a bottom decile or quintile), I also conducted additional analyses with a relative poverty measure with a poverty threshold equal to one half the median household income in each year, as well as a relative affluence measure with an affluence threshold equal to twice the median household income in each year. These do not change the conclusions, and the results are shown in appendix tables and briefly discussed in the Sensitivity Analysis section below.

Race and ethnicity

I calculate poverty and affluence among the following mutually exclusive and exhaustive racial and ethnic groups: non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, non-Hispanic American Indians, non-Hispanic other races, and Hispanics. There are a few data limitations when extending the analysis back to 1960 because of changes in the way data on race and ethnicity were collected by the U.S. Census Bureau. The categories for whites and blacks did not change much, so trends for these groups are the most reliable. In 1960 and 1970, there were response categories for only specific Asian groups, including Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Hawaiian (Korean was first used in 1970). In 1980 and thereafter, additional Asian groups were identified, plus a residual category for “other” Asian. Beginning in 2000, Pacific Islanders had a separate response category; to enhance comparability, I include all people who identify as Asian or Pacific Islander as Asian. Data on Hispanic origin were collected in a question that specifically asks respondents if they are of Hispanic origin or not (separate from the race question). This question was asked in a fairly consistent fashion beginning in 1980. In 1960 and 1970, the IPUMS imputes Hispanic origin using eight criteria based on Hispanic birthplace, parental birthplace, grandparental birthplace, Spanish surname, and/or family relationship to a person with one of these characteristics (Gratton and Gutmann 2000).

With regard to other groups, the response category for American Indians did not change much over time. However, in recent decades, more people have reported being American Indian than would be expected given recorded patterns of fertility, mortality, and migration, indicating that it has become more common to assert an American Indian racial identity than in the past (Liebler and Ortyl 2014; Snipp 1997). So patterns and trends in poverty and affluence among American Indians should be viewed with some caution. The “other race” category in the analysis needs to viewed with caution as well, as the Census Bureau used different procedures over time to classify respondents as “other race.” In addition, beginning in 2000, individuals could mark as many races as they pleased; these individuals are categorized as “other race” in the analysis. While people of “other” race are included in the accounting of the complete distribution of the poor and affluent populations, I do not focus on this group in many of the analyses.

I also conducted additional analyses where race groups are defined without reference to Hispanic origin (e.g., people who identified as white were categorized as such regardless of how they responded to the Hispanic origin question). The results of these analyses differed modestly in that racial and ethnic disparities narrowed by more using this approach than what is shown, mainly because whites who are Hispanic have a lower socioeconomic profile than non-Hispanic whites. Thus, the decline in disparities described below are more conservative estimates than the alternative approach.

The analyses focuses on differences poverty and affluence across panethnic racial and ethnic groups over time to because data are missing on a number of subgroups in earlier years, and some of the ethnic groups (e.g., Dominicans) were quite small through most of the study period. However, I include results on the largest Asian and Hispanic ethnic groups for 2015 in Appendix Tables A1 and A2 to show the extent to which differences in the likelihood of poverty and affluence reported for the panethnic groups are generalizable to subgroups. These results are described briefly in the results section.

Individual and Family Level Variables

I include a number of individual and family characteristics in the analysis, including gender, age, education, family structure, nativity, region, metropolitan status. Specifically, I compute four educational categories for the family householder: less than high school, high school only, some college, and Bachelor’s degree or more. Family structure is measure with variables for female-headed family, married-couple family, and other family type (such as a person living alone or with housemates). Variables are included for family size and number of children of the family householder. People are classified into four regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West. There is a dummy variable for whether a person lives in a metropolitan area. The analyses include age of the family householder, and a square term, as the association of age with poverty and affluence may be non-linear (e.g., a decline in affluence among the elderly).

Analytical Strategy

The analysis proceeds as follows. I begin with a descriptive look at patterns and trends in poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity from 1959 to 2015. These analyses will answer the first research question: How have patterns of poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity changed over time? This will be followed by logistic regressions to see how the likelihood of poverty and affluence across groups has changed over time including the sociodemographic characteristics described above. This analysis answers the second question posed: How has the relatively likelihood of poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity changed? These regressions will also show the relationship between the various control variables and poverty and affluence, which will be helpful for understanding results from the subsequent decomposition analysis.

Finally, to answer the third research question (to what extent do family- and individual-level characteristics help explain differences in the prevalence in poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity, and how have these associations changed over time?) I conduct a decomposition analysis using a variant of the well-known Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression (Blinder 1973; Oaxaca 1973) developed by Fairlie (2005) and Bauer and Sinning (2008) for nonlinear regression models. This decomposition method allows us to estimate the role of group characteristics in explaining differences in poverty and affluence by race in a given period versus what remains unexplained The analyses focus on three time periods: 1959, 1979, and 2015. The decomposition can be written as:

where is the difference in the average probability of the outcome (poverty and affluence) between groups A and B, EβA (YiA|XiA) refers to the conditional expectation of YiA and EβA (YiB|XiB) to the conditional expectation of YiB evaluated at the parameter vector βA (Bauer and Sinning 2006). Thus, the first two terms on the right-hand side of the equation provide an estimate of the impact of differences in the endowments (characteristics) of groups A and B on differences in the outcomes, while the last two terms reveal the effect of differences in coefficients on differences in the outcomes, which are treated as differences that cannot be explained by differences in the characteristics themselves. The contribution of specific characteristics is computed by using the Fairlie command in Stata (Fairlie 2005; Fairlie and Robb 2007).

This decomposition approach shares the same potential issue of the original Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition in that results might be sensitive to the choice of the reference group. That is, in the equation above, Group A coefficients (i.e., from models that include only members of Group A) are applied to Group B means in the first two terms, and Group B means are used in the second two terms. An alternative would be to apply Group B coefficients (i.e., from models that include only members from Group B) to Group A means and use Group A means in the latter two terms. A more common approach, and the one used in the following analyses, is to use pooled regression coefficients (from a weighted sample that includes individuals of the two groups being compared) and apply them to means of both groups (Neumark 1988; Oaxaca and Ransom 1994; Fairlie and Robb 2007). In sensitivity analyses, I find that using different reference group coefficients sometimes affects the magnitude of the effect of endowments, but it does not change this study’s conclusions. This issue is discussed in further detail at the end of the results section.

Results

Descriptive findings

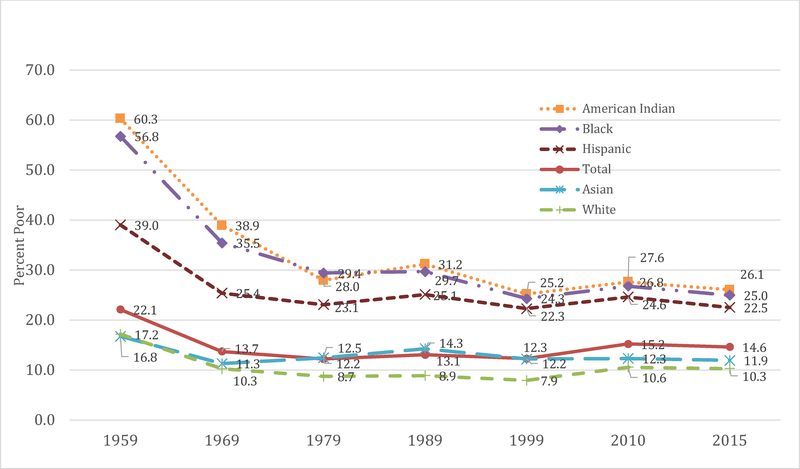

Figures 1 shows trends in poverty by race and ethnicity over the 1959 to 2015 period. The trends in Figure 1 are fairly widely known: poverty fell for all groups in the 1960s, but then fluctuated with the business cycle thereafter. Non-Hispanic whites have the lowest poverty rate (10.3 percent in 2015), followed by Asians (11.9 percent), Hispanics (22.5 percent), blacks (25.0 percent), and American Indians (26.1 percent).1 Disparities in poverty tend to be larger in 1959 than in 2015, with significant narrowing of gaps during the 1960s. However, some narrowing has occurred in recent decades as well. For example, since 1980, the poverty rate for non-Hispanic whites drifted up from 8.7 percent to 10.3 percent in 2015. In contrast, the poverty rates for all other groups are lower in 2015 than 1980, though sometimes only slightly so.

Figure 1.

Percent Poor by Race/Ethnicity and Year: 1959–2015

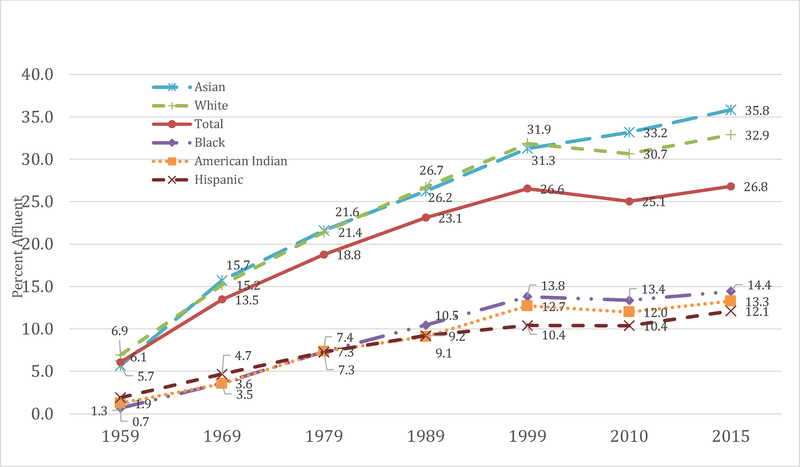

Figure 2 shows the percentage of the population that is affluent, by race and ethnicity, where families with incomes over five times the poverty line are considered affluent. Reflecting general increases in living standards, affluence rose for the total population and among all racial and ethnic groups. In 2015, Asians had the highest rate of affluence (35.8 percent), followed by whites (32.9 percent), blacks (14.4 percent), American Indians (13.3 percent), and Hispanics (12.1 percent). Thus, racial and ethnic disparities are large. The absolute gap in percentage of each group that is affluent rose over the period, though the relative differences narrowed substantially. For example, the absolute gap in affluence between whites and blacks was 18.5 percentage points in 2015, up from 6.2 percentage points in 1959. However, whites were 2.3 times more likely to be affluent than blacks in 2015, down from 9.9 times more likely in 1959, and even down modestly from 2.9 times more likely in 1979. Also of note, the gap between the percentage of Asians who were affluent compared with the percentage of whites who are affluent has grown since 2000, signifying a greater Asian advantage over this period.

Figure 2.

Percent Affluent, Defined as Family Income Five Times the Poverty Line or Greater, by Race/Ethnicity and Year: 1959–2015

Multivariate Analysis

I examine the association between race/ethnicity and poverty and affluence over time with a series of logistic regressions. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the independent variables in models. Overall, we see that the mean age of all groups increased over time, with whites having the oldest mean age. Education also increased among all groups. There was a decline in married-couple families for all groups over time, though there are some substantial differences in family structure across groups, with Asians the most likely to be living in married-couple families, followed by whites. Families became smaller over time, and there are substantial differences in the percent foreign-born across groups, with Asians having the highest percentage. The percentage of all groups living in metropolitan areas and in the South generally increased, though there are also some group differences by geography.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, 1959–2015

| 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Asian | American Indian | Hispanic | White | Black | Asian | American Indian | Hispanic | White | Black | Asian | American Indian | Hispanic | |

| Age | 44.78 | 43.99 | 43.60 | 44.50 | 40.66 | 45.01 | 43.32 | 42.16 | 41.21 | 40.20 | 50.69 | 47.68 | 46.82 | 48.61 | 43.96 |

| Male | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.30 |

| High school | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| Some college | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.21 |

| BA+ | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| Family structure | |||||||||||||||

| Married couple family | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 0.64 |

| Female-headed family | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.21 |

| Other family type | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.15 |

| Family size | 4.08 | 5.36 | 4.45 | 5.89 | 5.39 | 3.35 | 4.12 | 4.08 | 4.31 | 4.38 | 2.96 | 3.25 | 3.60 | 3.67 | 4.02 |

| Number of own children | 1.99 | 2.81 | 2.22 | 3.36 | 3.06 | 1.45 | 2.10 | 1.84 | 2.22 | 2.27 | 1.07 | 1.35 | 1.28 | 1.41 | 1.75 |

| Foreign born | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.53 |

| In metro area | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.48 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.45 | 0.91 |

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Midwest | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| South | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.37 |

| West | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.40 |

| N (in 000s) | 7451.0 | 906.4 | 41.3 | 30.0 | 279.4 | 1758.8 | 253.3 | 35.1 | 14.0 | 144.2 | 2025.3 | 286.4 | 155.3 | 278.5 | 429.6 |

Source: 1960 and 1980 decennial censuses and 2015 American Community Survey. Note: number of own children, educational attainment, foreign-born status, and age refer to the characteristics of the family householder.

Table 2 shows logistic regression results for the association between race/ethnicity and poverty in 1959, 1979, and 2015. It shows that all groups are more likely to be poor than whites in just about all years, with and without controls. In 2015, for example, that odds of being poor for blacks was 3.16 times that of whites when no controls are in the model. The odds were 1.31, 3.02, and 2.57, and 1.90 for Asians, American Indians, and Hispanics, respectively. The odds of being poor relative to whites generally declined over the period, though the declines for some groups were uneven. For example, the odds of being poor for blacks was 6.33 times that of whites in 1959, dropping to 4.36 in 1979, and finally to 3.16 times in 2015 when no controls are included. Among American Indians there was a continuous decline as well, though among Asians and Hispanics there was an increase between 1959 and 1979, followed by a decline. As noted before, the changes for Asians and Hispanics between 1959 and 1979 should be viewed with some caution, given changes in the definitions of these groups in this period.

Table 2.

Logistic Regressions for Poverty (Odds Ratios)

| 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (White is omitted category) | ||||||

| Black | 6.33* | 4.29* | 4.36* | 2.31* | 3.16* | 1.71* |

| Asian | 0.97* | 1.55* | 1.49* | 2.01* | 1.31* | 1.46* |

| American Indian | 7.33* | 3.97* | 4.06* | 2.40* | 3.02* | 1.96* |

| Hispanic | 3.09* | 2.79* | 3.14* | 1.99* | 2.57* | 1.25* |

| Other race | 2.16* | 2.17* | 2.42* | 2.05* | 1.90* | 1.39* |

| Age | 0.87* | 0.87* | 0.91* | |||

| Age squared | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| Male | 0.90* | 0.84* | 0.84* | |||

| Educational Attainment (less than high school is omitted category) | ||||||

| High school | 0.44* | 0.41* | 0.45* | |||

| Some college | 0.35* | 0.35* | 0.30* | |||

| BA+ | 0.18* | 0.21* | 0.12* | |||

| Family structure (married couple is omitted category) | ||||||

| Female headed family | 3.52* | 4.62* | 3.98* | |||

| Other family | 4.22* | 4.32* | 4.19* | |||

| Family size | 0.90* | 0.88* | 0.82* | |||

| Number of own children | 1.51* | 1.45* | 1.53* | |||

| Foreign born | 0.96* | 1.13* | 1.30* | |||

| In metro area | 0.39* | 0.61* | 0.78* | |||

| Region (northeast is omitted category) | ||||||

| Midwest | 1.27* | 0.89* | 1.04* | |||

| South | 2.32* | 1.15* | 1.12* | |||

| West | 1.15* | 0.93* | 1.06* | |||

| N | 8,711,101 | 8,711,101 | 2,207,680 | 2,207,680 | 2,794,855 | 2,794,855 |

| −2 Log L | 170,562,727 | 138,179,678 | 154,894,357 | 130,571,024 | 218,264,603 | 180,999,272 |

p<.001

The control variables help explain some of the differences in the likelihood of poverty by race and ethnicity, but certainly not all. For example, the odds of being poor among blacks relative to whites falls from 3.16 with no controls to 1.71 with controls in 2015. For Hispanics it also drops, from 2.57 to 1.25, and for American Indians, from 3.02 to 1.96. These declines indicate that the observed variables in the model, such as education, age, and family structure, help explain some of the gap in poverty. As has been mentioned earlier, a caveat is that these are not meant to be wholly causal models. Some of the these variables can reflect poverty/affluence.

The control variables are associated with poverty in expected ways. Age has a negative association with poverty, men are less likely to be poor, as are people with higher levels of education. People living in female-headed families and other family types are substantially more likely to be poor than people in married couple families. Family size has a negative association with poverty, though more children are positively associated with poverty. Foreign-born people are more likely to be poor than the native-born in 1979 and 2015, and people living in metro areas are less likely to be poor. There are some regional differences in poverty, though the odds of being poor in the South relative to the Northeast declined over time.

Table 3 show results for affluence. Many of the patterns in this table are the same, but with a couple of important differences. In 1959, racial and ethnic differences were generally quite stark, as the odds ratios for blacks, Asians, American Indians, and Hispanics to be affluent relative to whites were only 0.09, 0.81, 0.17, and 0.26, respectively (without controls). The odds increased for all groups in 1979 (though the increase for Hispanics was slight), and there were further small increases for most groups in 2015, except for Hispanics, where the odds ratio remained at 0.29. In 2015, substantial disparities remain for most groups.

Table 3.

Logistic Regressions for Affluence (Odds Ratios)

| 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (White is omitted category) | ||||||

| Black | 0.09* | 0.17* | 0.29* | 0.54* | 0.34* | 0.56* |

| Asian | 0.81* | 0.76* | 1.01* | 0.83* | 1.10* | 1.03* |

| American Indian | 0.17* | 0.47* | 0.29* | 0.56* | 0.33* | 0.60* |

| Hispanic | 0.26* | 0.51* | 0.29* | 0.54* | 0.29* | 0.59* |

| Other race | 0.41* | 0.67* | 0.59* | 0.64* | 0.69* | 0.87* |

| Age | 1.30* | 1.31* | 1.20* | |||

| Age squared | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| Male | 1.13* | 1.18* | 1.10* | |||

| Educational Attainment (less than high school is omitted category) | ||||||

| High school | 2.30* | 2.09* | 2.50* | |||

| Some college | 4.20* | 3.16* | 4.12* | |||

| BA+ | 10.28* | 7.00* | 13.20* | |||

| Family structure (married couple is omitted category) | ||||||

| Female headed family | 0.45* | 0.30* | 0.25* | |||

| Other family | 0.40* | 0.33* | 0.26* | |||

| Family size | 0.89* | 0.87* | 0.85* | |||

| Number of own children | 0.68* | 0.63* | 0.77* | |||

| Foreign born | 0.92* | 0.92* | 0.72* | |||

| In metro area | 2.04* | 1.96* | 1.77* | |||

| Region (northeast is omitted category) | ||||||

| Midwest | 0.99* | 1.20* | 0.69* | |||

| South | 0.80* | 0.4* | 0.71* | |||

| West | 1.04* | 1.16* | 0.85* | |||

| N | 8,711,101 | 8,711,101 | 2,207,680 | 2,207,680 | 2,794,855 | 2,794,855 |

| −2 Log L | 78,016,677 | 63,044,487 | 208,104,400 | 168,845,818 | 330,654,999 | 264,502,063 |

p<.001

One striking exception is that Asians reached parity with whites over the period. In 1979, with the odds of affluence for Asians was 1.01 times that of whites in models without controls. However, once controls were included in the model, the Asian advantage disappeared, and Asians were less likely to be affluent than whites (odds of 0.83), holding other characteristics constant. By 2015, however, the odds for Asians being affluent relative to whites increased to 1.10 times without controls, and differences were slight but associated with advantage (1.03) in models with the control variables. The control variables themselves are associated with affluence in expected ways, as the ones that were positively associated with poverty are for the most part negatively associated with affluence. Education stands out as having a very large association with affluence.

As described in the Data and Methods section, the analyses focus on differences in poverty and affluence across panethnic groups because of missing or sparse data for a number of groups in the earlier years of the study period. However, I include results for specific ethnic groups in 2015 in Appendix Tables A1 and A2 to show the extent to which results for panethnic groups are generalizable to specific ethnic groups. Table A1, which focuses on Asians, indicates that three of the five largest Asian groups (Japanese, Filipinos, and Asian Indians) were less likely to poor than non-Hispanic whites in models without controls, though all except Filipinos were more likely to be poor once controls are included, mirroring the panethnic pattern. With regards to affluence, all specific groups except the Vietnamese were more likely to be affluent than whites in models without controls, and three of the groups remained more likely to be affluence in models with controls (Chinese, American Indians, and Japanese). Thus, there is clearly some variation across groups, though general conclusions derived from the panethnic models apply to most of the largest specific ethnic groups.

According to Table A2, most of the conclusions about Hispanic poverty and affluence apply to the largest specific ethnic groups, with a couple of exceptions. All groups are more likely to be poor than whites in models with controls (except “other Central American”), and most are less likely to be affluent, with the exception of Cubans.

Decomposition analysis

Finally, the decomposition analysis examines whether there are particular individual- and family-level characteristics that explain groups differences in poverty and affluence, and how their effects have changed over time. Table 4 shows results for poverty. The first three rows confirm the descriptive statistics that poverty gaps between various minority groups and whites have generally narrowed over time. Figures in the next row indicate that over the course of the 1959 to 2015 period, the observed characteristics generally explain an increasing share of the poverty gap across groups. For example, the characteristics explains two thirds (67 percent) of the poverty gap between whites and blacks in 2015, up from about half (49 percent) in 1959. The decline in the proportion of the racial and ethnic disparities that cannot be explained by the variables in the models indicates that such unobservable factors play a smaller role than they used to. This could result if factors such as discrimination, neighborhood conditions, and other unobserved causes of disparities have become less important over time, while factors such as differences in human capital, family formation patterns, and factors associated with immigration have become more important.

Table 4.

Decompositions of Differences in Poverty, by Race and Year

| Black | Asian | American Indian | Hispanic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | |

| Whites % poor | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Minority group % poor | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| Difference | −0.40 | −0.21 | −0.15 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.43 | −0.19 | −0.14 | −0.22 | −0.14 | −0.11 |

| Total % explained | 49% | 57% | 67% | NA | 4% | 91% | 42% | 45% | 53% | 31% | 57% | 92% |

| % explained by each | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0% | 4% | 16% | NA | 21% | 84% | 1% | 7% | 10% | 0% | 11% | 23% |

| Male | 0% | 0% | 0% | NA | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education | 11% | 13% | 15% | NA | −19% | −24% | 8% | 11% | 21% | 15% | 24% | 46% |

| Family structure | 12% | 32% | 34% | NA | −15% | −79% | 5% | 10% | 12% | 4% | 6% | −3% |

| Foreign born | 0% | 0% | 2% | NA | 34% | 127% | 0% | 0% | −2% | 1% | 9% | 22% |

| Family size | 15% | 9% | 2% | NA | 19% | 12% | 15% | 8% | 5% | 23% | 15% | 8% |

| # of children | 0% | 0% | 0% | NA | −1% | −1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| In metro area | −2% | −4% | −3% | NA | −32% | −29% | 11% | 7% | 5% | −14% | −9% | −6% |

| Region | 13% | 4% | 2% | NA | −2% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 3% | 2% | 1% | 2% |

Notes: all differences are statistically significant except for # of children for Asians in 1959 and for Hispanics in 2015, and region for Asians in 2015. NA: Not Applicable-- the differences in poverty are too small to be meaningfully explained.

With regard to the black-white poverty gap, differences in family structure, age, and educational attainment play the largest roles in explaining the gap (34, 16, and 15 percent, respectively in 2015), and the roles of each also increased over time. Among Asians, the gap in poverty was very small in 1959, such that the effect of any particular characteristics in explaining the difference would look very large (because the denominator in the calculation is the difference)—so these are not presented in the table. In 2015, observed characteristics explain 91 percent of the white-Asian poverty gap, with nativity explaining the largest portion (more than the entire net gap), followed by age. The table shows that family structure, living in metropolitan areas, and educational attainment are protective—if Asians more resembled whites in these characteristics, then the white-Asian poverty gap would have been even larger.

Among Hispanics, the percent the poverty gap explained by the observed characteristics was 92 percent in 2015 (up from just 31 percent in 1959), with education (46 percent), age (23 percent), and nativity (22 percent) explaining most of the white-Hispanic poverty gap. Thus, Hispanics resemble Asians in that immigration-related factors play an important role, but unlike Asians, education is not protective; rather, it contributes to their relatively high levels of poverty.

With regards to the American Indian-white poverty gap, observed characteristics explained 53 percent of the gap in poverty in 2015 (up from 42 percent in 1959), with, as for black-white gaps, differences in educational attainment, family structure, and age playing the largest roles (explaining 21, 12, and 10 percent of the gap, respectively).

In terms of the role of different factors across groups, we see that family structure played the largest role among blacks. Nativity and age were important among Asians and Hispanics. In addition, education also stood out as being particularly important for Hispanics, and multiple factors were important among American Indians.

Table 5 shows decomposition results when using affluence as the outcome. The patterns are in some ways similar to poverty: observed characteristics tend to explain a greater proportion of the affluence gaps over time, with some exceptions. Among blacks, family structure plays the most prominent role (explaining 32 percent of the gap in 2015), followed by education (25 percent). Interestingly, while the effect of family structure on poverty among African American did not change much between 1979 and 2015, its effect on affluence grew, as the negative association between single parenthood and affluence grew stronger over the period—perhaps due to increasing assortative mating (McLanahan 2004). Among American Indians, education plays the largest role (33 percent in 2015), followed by family size (18 percent), family structure (15 percent) and metropolitan status (12 percent). With regards to metropolitan status, this is a function of people in nonmetropolitan areas considerably less likely to be affluent, and American Indians over-represented in nonmetropolitan areas.

Table 5.

Decompositions of Differences in Affluence, by Race and Year

| Black | Asian | American Indian | Hispanic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | 1959 | 1979 | 2015 | |

| Whites % affluent | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.34 |

| Minority group % affluent | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Difference | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| Total % explained | 58% | 72% | 67% | NA | NA | 98% | 80% | 74% | 73% | 70% | 72% | 80% |

| % explained by each | ||||||||||||

| Age | −17% | −9% | −4% | NA | NA | 27% | −20% | −5% | −6% | −8% | −5% | 2% |

| Male | 0% | 0% | 0% | NA | NA | −2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education | 49% | 34% | 25% | NA | NA | 214% | 52% | 28% | 33% | 44% | 35% | 43% |

| Family structure | 3% | 13% | 32% | NA | NA | 82% | 0% | −1% | 15% | −4% | −6% | 4% |

| Foreign born | 0% | 0% | 1% | NA | NA | −129% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 4% | 13% |

| Family size | 18% | 32% | 11% | NA | NA | −207% | 36% | 42% | 18% | 38% | 45% | 21% |

| # of children | 0% | 0% | 0% | NA | NA | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| In metro area | 2% | 0% | −2% | NA | NA | 76% | 13% | 10% | 12% | −1% | −2% | −2% |

| Region | 4% | 2% | 4% | NA | NA | 37% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 1% |

Notes: all differences are statistically significant except for foreign born for blacks in 1979 and for American Indians in 1979; number of children for all groups in 2015. NA: Not Applicable-- the differences in affluence are too small to be meaningfully explained.

Education and nativity continue to play important roles among Asians and Hispanics. In particular, among Hispanics education plays the largest role (explaining 43 percent of the gap in 2015), followed by family size (21 percent) and nativity (13 percent). Among Asians, gaps again are small, so the decomposition shows relatively large effects of individual characteristics, especially in 1959 and 1979, when the results measured in percentage terms are not very useful. In 2015, Asians were advantaged over whites, with education, family structure, and metropolitan status contributing to their advantage, and family size and nativity working in the opposite direction.2

Generally speaking, education tends to play a larger role in explaining racial differences in affluence than poverty, indicative of the particularly strong association between human capital and upward mobility. Conversely, nativity tends to be more important for understanding racial disparities in poverty than affluence.

Sensitivity Analyses

The Use of Alternative Poverty and Affluence Measures

I also conducted additional analyses with a relative poverty measure with a poverty threshold equal to one half the median household income in each year, as well as a relative affluence measure with an affluence threshold equal to twice the median household income in each year. These results are shown in Appendix Tables A3 and A4, respectively. The results are similar to those shown in main decomposition tables for poverty and affluence (Tables 4 and 5). For example, in Appendix Table A3 we see that the difference in relative poverty between whites and blacks declined over the period, and characteristics explained a larger proportion of the difference in 2015 than 1959. The role of family structure increased from 1959 to 1979 and remained stable thereafter. Among Hispanics, the total difference explained by various characteristics also increased over time, and education in particular played a large role. The white-Asian difference in poverty is quite small in all years—to small to meaningfully decompose in 1979 and 2015.

With regards to relative affluence, we again see many similarities. The role of family structure in explaining white-black differences increased steadily over the time period, the Asian-white gap in affluence grew (signifying higher rates of affluence among Asians than whites over time), and education playing an important protective factor. Conversely, education once again plays an important role in the white-Hispanic gap in relative affluence. Among American Indians and whites, several factors remain important in explaining differences.

The Use of Alternative Reference Groups in the Decompositions

As described in the Data and Methods section, results of decompositions can be sensitive to the reference group chosen (i.e., whether one uses regression coefficients from models that contain members of Group A vs. Group B). The decomposition results shown above use regression coefficients from models that pool whites and the minority group members of interest. This section reviews results when using coefficients from models that contain whites only versus those that contain minority group members only.

Overall, the conclusions of this study remain the same regardless of the reference group chosen. Specifically, using a coefficients from a model including only one particular group (e.g., white vs. the minority group) does not consistently produce higher or lower estimates of the role of characteristics in explaining racial and ethnic differences. For example, using pooled regressions of blacks and whites produced an estimate that characteristics explained 67 percent of the white-black gap in poverty (shown in Table 4). Using whites as a reference group (i.e., models that include only whites) produced a modestly lower estimate of 57 percent (Appendix Table A5), while using blacks as the reference group produced an estimate of 67 percent (Appendix Table A6). Using pooled regressions produced an estimate that characteristics explained 67 percent of the white-black gap in affluence (shown in Table 5). Using whites as a reference group produced a similar estimate of 64 percent (Appendix Table A7), while using blacks as the reference group produced a lower estimate of 55 percent (Appendix Table A8). All of these figures are larger than the respective 1959 estimates, as also shown in the tables, supporting the conclusion that an increasing proportion of the black-white difference in poverty and affluence are explained by these observed characteristics, regardless of the reference group.

One of the reasons that the choice of the reference group has only a modest effect on results is that the independent variables, with some exceptions, tend to have similar associations with poverty and affluence across the racial and ethnic groups (and more so over time). For example, while the odds that a person in a female-headed family is affluent compared to a person in married-couple family in 2015 was 0.25 for the entire pooled sample (Table 4), the odds for regressions that include, in turn, only non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, non-Hispanic American Indians, and Hispanics, were 0.24, 0.24, 0.41, 0.19, and 0.24, respectively—a modest band of variability. Similarly, the odds that a person in family where the householder has a BA or more is affluent compared to a person in family where the householder does not have a high school diploma in 2015 was 13.20 for the entire pooled sample. In samples stratified by race, these odds were 11.92, 12.02, 13.40, 9.26, and 15.34 for non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, non-Hispanic American Indians, and Hispanics, respectively. These difference are not trivial, but on the whole modest, as they are not great enough to affect the conclusions from the decomposition analysis.

Perhaps the most notable variation in the decomposition results when using different reference groups, is in Asian-white decomposition, where the role of nativity is consistently larger (in both the poor and affluent models) when using coefficients from models with Asians only than in models with whites only or the pooled equations. The reason for this is that association between nativity and poverty and affluence is stronger among Asians than for whites (or whites and Asians pooled). This is suggestive of a strong pattern of generational economic upward mobility among Asians. Among Hispanics, nativity actually plays a smaller role in the poverty decomposition when using coefficients from the Hispanic sample only than the pooled sample, though there is little difference in results by reference group when looking at the role of nativity in explaining affluence.

Conclusions

The goal of this analysis has been to document racial disparities in poverty and affluence from 1959 to 2015 and shed some light on the dynamics of these differences over the period. While trends in poverty have been fairly well documented, we know less about trends in affluence for all of the groups included here—whites, blacks, Asians, Hispanics, and American Indians. I examined changes in the relative likelihood of poverty and affluence by race and ethnicity and then used a decomposition analysis to examine the relative contribution of important sociodemographic correlates of poverty and affluence, including education, family structure, and nativity, and how their effects have changed over time.

The analyses indicate that racial disparities in poverty and affluence are generally large. However, disparities between minority groups and whites generally declined over the period. For example, poverty declined for all groups, but moderately more for minority groups than whites. Similarly, affluence increased substantially for all groups—indicative of rising living standards—but in relative terms more for minority groups than whites.

There is variation across groups. Blacks and American Indians tended to be the most disadvantaged groups, though the magnitude of disadvantage declined over the period, and there was only a little decline in the affluence gap after 1979. Hispanics were less likely to be poor than blacks and American Indians, but about as equally likely to be affluent. The white-Hispanic gap in poverty and affluence actually increased from 1959 to 1979, before declining slightly thereafter. Finally, while Asians continue to be more likely to be poor than whites, they reached parity with whites in affluence in 1979 and surpassed whites by 2015.

A key contribution of this paper lay in the results of the decomposition analyses, which examined which factors in particular were most important in explaining disparities. While a number of previous studies have documented differences in socioeconomic attainment between groups (e.g., Sakamoto and Kim 2013, Snipp and Cheung 2016), they have not focused on the changing roles of groups characteristics in explaining change over time. The findings of this analysis indicates that the effect of these factors varied by group. Among Hispanics and Asians, education and nativity consistently were important factors. For Hispanics, education was particularly important for explaining disparities (explaining between 43 and 46 percent of the poverty and affluence gaps, respectively, in 2015), and we find that its role increased over time, especially with regards to poverty—a finding not widely appreciated in the literature. Among Asians, education was a “protective” factor—if Asians more resembled whites in terms of education, the disparities in poverty would have been larger. Nativity was important for both groups, though more so in explaining poverty differentials than those in affluence (another findings not as widely appreciated in the literature)—suggesting that being foreign born is associated with greater labor market challenges among low skill workers than those at the upper end—many who may have been admitted into the United States on the basis of their skills.

Thus, the analysis supports the notion that the effects of human capital differentials and the immigrant incorporation process are very important for understanding disparities among Hispanics and Asians (Sakamoto and Kim 2013; Lee and Zhou 2014; Chiswick 1986; Feliciano 2005). Highly selective immigration from Asia likely helps explain good socioeconomic outcomes of Asians in the United States, combined with the large emphasis these immigrant parents place on schooling for their children (Hsin and Xie 2014; Lee and Zhou 2014; Jiménez and Horowitz 2013). While Asian immigrants are positively selected on education, the same is not the case for Hispanics, especially immigrants from Mexico (Chiswick 1986; Feliciano 2005). The undocumented status of many Latin American immigrants also slows the economic incorporation process, as such immigrants do not have access to many opportunities in the formal labor market, which would likely have a particularly strong effect on the likelihood of becoming affluent (Brown 2007; Bean et al. 2015; Perlmann 2005). So to the extent to which immigration levels remain high and the selectivity patterns hold, we should continue to see divergent outcomes among Asians and Hispanics, even as generational progress slowly serves to narrow the gap between whites and Hispanics.

The decomposition analysis also showed that the effect of family structure grew in importance and became the most significant factor among blacks—not only for poverty, but also for affluence, explaining about a third of the disparity in poverty and affluence in 2015. While the impact of family structure on poverty grew mainly between 1959 and 1979, and remained stable thereafter, the effect of family structure on affluence increased further after 1979—a factor not appreciated in the existing literature on disparities in poverty and affluence, and indicative of the importance of comparing the factors that affect each of these outcomes. The patterns are likely a result of the slightly weakening correlation between family structure and poverty in recent decades, as indicated by the decline in poverty among female-householder families (U.S. Census Bureau 2016b; Cancian and Reed 2008; Baker 2015), though the strengthening correlation between family structure and affluence. The latter likely results from the increase in assortative mating by education, and the “diverging destinies” between families with well-educated two-parent families and others, and their contributions to racial inequality (McLanahan 2004; McLanahan and Percheski 2008). The fact that family structure plays an important role is indicative of the importance of the interaction between changing economic conditions that have hindered the prospects of less-skilled men and increased opportunities for women, as well as changes in cultural attitudes that have reduced the stigma on single parenthood—both factors may have affected blacks and Hispanics more so than whites and Asians (Cherlin 2004, 2009; Smock and Greenland 2010; Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001; Goldscheider and Kaufman 2006; Trent and South 1992; Sakamoto et al. 2000; Snipp and Cheung 2016). The continued increase in single-parenthood among white families (Murray 2012), however, could over time narrow the contribution of family structure to racial and ethnic disparities in poverty and affluence in the future.

Among American Indians, no single factors plays a dominant role—several are important, including education (generally the most important), family structure, and, depending on the outcome, family size, age, or metropolitan status. Thus, it appears that cumulative disadvantages are important for American Indians, who are more likely to have lower levels of human capital, live in single parent families, and have a younger age structure and live in nonmetropolitan areas than other groups.

Finally, the implications of the existence of an unexplained gap for most groups—and its decline over time—are not clear cut, but suggestive. The presence of an unexplained difference is sometimes attributed to discrimination (e.g., Cancio, Evans, and Maume 1996; Snipp and Cheung 2016), since discrimination typically is not observed in survey data. However, it should be emphasized that there are other unobserved factors in the census data used, including neighborhood conditions, social capital, and cultural capital—all influenced by race-related factors, such as racial and ethnic segregation—that can also play a role. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that these types of factors played a smaller role in explaining racial and ethnic disparities in poverty and affluence over time. Instead, observed characteristics, such as educational attainment (a key indicator of human capital), nativity (indicative of the importance of the immigrant incorporation process), and family structure (indicative of the interaction between economic conditions and culture) played a larger role.

This study has a few limitations. The use of cross-sectional decennial and ACS data precludes making strong causal inferences about the effect of the variables of interest, such as family structure, on poverty. Family structure can be both a cause and reflection of poverty. Thus, this study mainly sheds light on the factors associated with poverty, and how differences in these characteristics across racial and ethnic groups might reflect and contribute to differences in the prevalence of poverty and affluence. This study is also limited to the indictors available in the decennial and ACS files. Ideally we would have a broader array of variables, such as wealth, or experiences of discrimination to further probe inequalities, but these are unavailable. As noted earlier, the definitions of some of the racial and ethnic groups studied also varied over time, especially among Asians and Hispanics prior to 1980, so conclusions that extend to before then need to be made with caution.

In summary, the findings suggest that there were moderate steps toward racial equality in poverty and affluence over the 1959 to 2015 period, consistent with notion that there has been a decline in the significance of race in shaping life chances (Sakamoto, Wu, and Tzeng 2000; Wilson 1980). However, despite some narrowing of the racial gap and the general parity between whites and Asians, other large disparities remain, especially for blacks and American Indians. There are likely many causes for continued disparities among these groups, including racial discrimination in the labor market, which serves to reduce employment and wages. The increase in incarceration in the late 20th century also served to reduce human capital and wages among black men in particular, and these show up in higher poverty rates and lower rates in affluence among black families (Western and Pettit 2005). The legacy of historical inequalities may also play a role, as there is a fair amount of intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status in the United States (Duncan and Brooks-Gunn 1997; Isaacs, Sawhill, and Haskins 2008; Solon 1999). Differences in social and cultural capital, social and spatial isolation, and culture factors, may also help explain some of the differences (Loury 1977, 2002; Massey 2007; Massey and Denton 1993; Patterson and Fosse 2015; Wilson 1987). Thus, while gaps between groups have narrowed, considerable differences remain.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Population Research Institute Center Grant, R24HD041025.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1.

Logistic Regressions of Poverty and Affluence among Detailed Asian Ethnic Groups, 2015

| Poverty | Affluence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (White is omitted category) | ||||

| Black | 3.17* | 1.71* | 0.34* | 0.56* |

| American Indian | 3.02* | 1.95* | 0.33* | 0.60* |

| Chinese | 1.75* | 1.94* | 1.28* | 1.13* |

| Japanese | 0.84* | 1.07* | 1.59* | 1.23* |

| Filipino | 0.59* | 0.76* | 1.08* | 0.96* |

| Asian Indian | 0.77* | 1.28* | 1.93* | 1.40* |

| Korean | 1.44* | 1.77* | 1.05* | 0.78* |

| Vietnamese | 1.66* | 1.37* | 0.58* | 0.84* |

| Other Asian | 2.06* | 1.61* | 0.53* | 0.73* |

| Hispanic | 2.57* | 1.25* | 0.29* | 0.59* |

| Other race | 1.90* | 1.39* | 0.69* | 0.87* |

| Age | 0.91* | 1.20* | ||

| Age squared | 1.00* | 1.00* | ||

| Male | 0.84* | 1.10* | ||

| Educational Attainment (less than high school is omitted category) | ||||

| High school | 0.45* | 2.49* | ||

| Some college | 0.30* | 4.11* | ||

| BA+ | 0.12* | 13.10* | ||

| Family structure (married couple is omitted category) | ||||

| Female headed family | 3.98* | 0.25* | ||

| Other family | 4.18* | 0.26* | ||

| Family size | 0.82* | 0.86* | ||

| Number of own children | 1.52* | 0.77* | ||

| Foreign born | 1.30* | 0.71* | ||

| In metro area | 0.78* | 1.77** | ||

| Region (northeast is omitted category) | ||||

| Midwest | 1.04* | 0.69* | ||

| South | 1.12* | 0.71* | ||

| West | 1.07* | 0.85* | ||

| N | 2,795,040 | 2,795,040 | 2,795,040 | 2,795,040 |