Abstract

Objective

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with unstable interpersonal relationships, affective instability, and physical health problems. In individuals with BPD, intense affective reactions to interpersonal stressors may contribute to the increased prevalence of health problems.

Methods

BPD (N=81) and depressed participants (DD; N=50) completed six daily ambulatory assessment prompts over 28 days. At each prompt, participants reported interpersonal stressors (disagreements, rejections, feeling let down), negative affect, and health problems in four domains (gastrointestinal, respiratory, aches, depressive symptoms). In multilevel moderated mediation models, we examined the indirect effects of interpersonal stressors on health problems via negative affect, by group.

Results

Interpersonal stressors were positively associated with negative affect in both groups (βs>.12, ps<.001), but more so for participants with BPD (βDay=.05, p<.001). Negative affect was positively associated with health problems across all domains (βsMoment/Day>.01, ps<.046), but associations were larger at the day level for respiratory symptoms in BPD (β=.02, p=.025) and for depressive symptoms in DD (β=.04, p<.001). Negative affect mediated the association of interpersonal stressors and health problems in both groups, with larger effects for the DD group for depressive problems (β=.02, p=.092) and for the BPD group for the other three domains (βs>.02, ps<.090).

Conclusions

Interpersonal stressors may contribute to increased physical health problems via an inability to regulate affective responses to such events. This pathway may be stronger in several health domains for those with BPD and may contribute to an elevated risk of morbidity and mortality in this disorder, suggesting a target for intervention to reduce these risks.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, Depression, Health problems, Interpersonal stressors, Negative affect, Ambulatory Assessment

Introduction

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a serious mental health condition that is distinguished by marked affective instability, impulsivity, and impairments in interpersonal functioning (1). Beyond functional impairments, BPD is also associated with increased mortality rates and vastly decreased life expectancies that are estimated to be up to 22 years shorter than those for the general population (2). These decreased life expectancies could, in part, be explained by the high prevalence of physical health problems (HP) that has been observed for those with BPD (e.g., 3). However, factors that drive these elevated levels of HP are largely unclear. In an attempt to fill this gap, the present study sought to examine factors associated with the manifestation of HP in BPD.

Previous studies addressing physical health in BPD samples have mostly examined the degree of association between different forms of HP and BPD status. Data from the second wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found that BPD was associated with substantial overall physical disability (4) and with specific conditions, including cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disease (5). Data from the McLean Study of Adult Development likewise found that non-remission from BPD was associated with greater probability for any physical illness and for chronic conditions, such as back pain and diabetes (e.g., 6). Moreover, cross-sectional studies have reported positive associations between BPD and poor self- and observer-rated overall physical health (e.g., 7) and chronic pain (e.g., 8).

Despite the substantial evidence supporting an association between BPD and poor physical health, only three studies have addressed potential underlying factors and only one of these studies has used a longitudinal design. In this latter study, BPD symptom severity, physical symptoms, and emotion dysregulation were measured at three time-points over 8 months, and BPD severity at wave 1 predicted physical health at wave 3 via emotion dysregulation at wave 2 (9). Two other studies adopted cross-sectional designs and included mixed patient samples in which they measured BPD features. In a chronic pain patient sample, affective instability indirectly accounted for the association between BPD features and pain (10). In a sample of rehabilitation patients, negative affect (NA) mediated the association between BPD features and pain experienced in the past month (11). Overall, these studies point toward a mediating role of dysregulated affect (which comprises both affective instability and high levels of NA) in the association between BPD and poor physical health.

While providing initial insight into the role of emotion dysregulation for HP in BPD, these studies are limited by the fact that only one study included participants with a formal BPD diagnosis and that associations were established mostly at a cross-sectional level. The temporal relationship of NA and HP in BPD thus remains largely unclear- especially considering a more micro-level time-scale than the eight-month time frame that was included in the single longitudinal study (9). Additionally, by focusing only on BPD symptoms and not accounting for other types of psychopathology, it remains unclear whether the observed effects have any specificity for BPD or whether they are a marker of psychopathology in general. Extending this work, we sought to examine how the association between NA and HP unfolds over time by assessing these constructs in the daily lives of individuals with BPD. Additionally, we further sought to examine the extent to which this association is specific to those with BPD, or whether it also applies to individuals with other types of psychopathology, specifically mood disorders.

Further extending previous studies, which focused only on the role of emotion dysregulation, the present study considered another potentially important contributor to HP in BPD: interpersonal stressors (IS). Numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies from social psychology have demonstrated the importance of IS for physical health, showing that social support and good relationship quality are highly predictive of good physical health (for reviews, see 12, 13), whereas relationship conflict is associated with poorer health (e.g., 14). Since BPD is characterized by unstable relationships and a large range of interpersonal difficulties (1), it seems likely that IS contribute to the high prevalence of HP in this group.

The present study

We assessed the impact of NA and IS, both of which have been associated with HP in previous studies (9–14), on HP in BPD. Previous research points to an interactive association between NA and BPD on HP, but has largely left unexamined other factors that may be involved (e.g. IS) and has provided little insight regarding the temporal relationship of these constructs. Moreover, nothing is known about whether these associations have any specificity for the BPD population. There is a need for this research, as understanding which factors contribute to the comorbidity of BPD and HP would provide an avenue for addressing this comorbidity and, potentially, improving not only mental but also physical health in this group. Such understanding would likely apply not only to BPD, but also, possibly, to any disorder that involved interpersonal difficulties and/or emotion dysregulation. However, understanding how IS and NA may contribute to HP is particularly relevant for those with BPD, because empirical studies show that both are highly prevalent in the daily lives of those with BPD (15) and have been described as core features of BPD and focal points for existing treatments (1).

We assessed NA, IS, and HP in the daily lives of individuals with BPD, using Ambulatory Assessment (AA). In AA studies, participants carry a handheld device, which prompts them to report on current variables multiple times daily while they are going about their daily lives in their natural environments. AA methodologies allow researchers to examine the contextual factors and micro-level processes that might contribute to broader epidemiological differences.

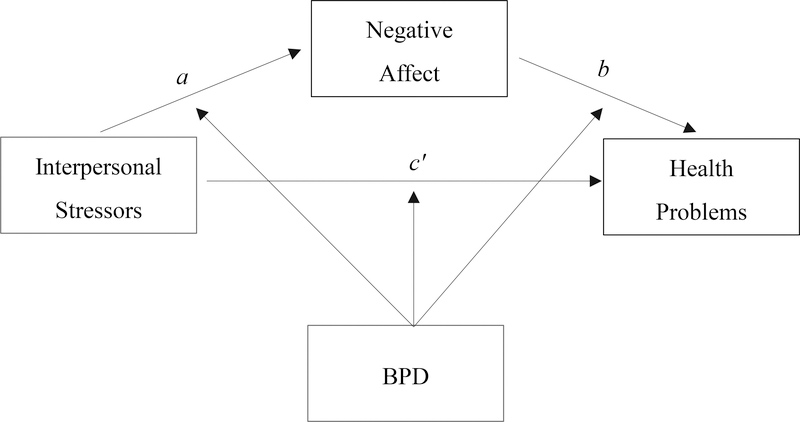

We hypothesized that IS would be associated with HP and expected NA to mediate this association (see Figure 1). The hypothesis that IS would be associated with HP is supported by myriad studies that show an association between relationship quality and physical health (12–14) and between NA and HP (e.g., 16). Thus, IS↔HP associations and NA↔HP associations have been established in previous work.

Figure 1.

Proposed mediation model including group (borderline versus depressed) as a moderating variable.

Conceptualizing NA as a mediator for the IS↔HP association was based on two lines of previous research. First, a number of previous AA studies have shown that IS are associated with increased NA in the moment and prospectively in BPD (15, 17). Thus, outside the association of each of these constructs with HP, they are closely related to each other. Second, findings have pointed to NA as a mediator of the association between BPD features and physical health (9) as well as pain (10, 11). This speaks toward a central role of dysregulated NA for HP in BPD. We therefore hypothesized that IS would increase NA in the moment, and that the resulting high levels of NA would manifest themselves in HP.

As is clear from our review, physical HP encompass a wide variety of specific health complaints. To capture different types of HP, we assessed four domains of momentary HP, modelled after the physical symptom checklist by Larsen and Kasimatis (18). We included the domains gastrointestinal, respiratory, and depression-related symptoms (e.g. fatigue), as well as aches, and expected the afore-described mediation model to hold for all four health domains.

In addition to a BPD group, we included a depressed control group (DD) to examine whether the postulated effects were specific to BPD, thus further extending previous work. Those with depression have also been found to be at greater risk for various HP (19), to have a decreased life expectancy (2), and to experience high levels of NA and IS in daily life (20). This renders depressed individuals an appropriate comparison group for examining the specificity, versus potential trans-diagnosticity, of an IS↔NA↔HP association.

We expected the proposed mediation model to be moderated by diagnostic group, such that the mediation would be significantly stronger for BPD individuals than for depressed individuals for the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and ache domains. This hypothesis was based on theories of BPD that underline the central role of emotion dysregulation in the disorder and empirical evidence suggesting a mediating role of NA for HP (1, 9–11). Specifically, BPD individuals should show a stronger association between IS and NA, and NA should in turn be more predictive of HP in the moment because of the pronounced difficulties with regulating NA in BPD. With regard to the depression-related symptoms that are included in the symptom checklist (e.g. fatigue, problems concentrating), we expected stronger effects for the DD group due to the clear overlap with major depression as operationalized in the DSM (1).

Method

Participants

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the University of Missouri Campus IRB and all participants provided written, informed consent prior to in-person participation. A total of 131 participants (17 male, 12.9%; age 18 to 65) were recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinics in Columbia, Missouri, USA, for a study assessing affective instability in BPD (21). Based on fulfillment of the DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD on the Structured Interview for DSM–IV Personality (SIDP-IV, 22), a total of 80 participants (6 male, 4.6%) were recruited for the BPD group. The DD group comprised 51 participants (11 male, 8.4%) meeting criteria for current major depressive disorder and/or dysthymia according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I (SCID-I, 23) and did not meet criteria for BPD. General exclusion criteria were a current psychotic disorder, history of severe head trauma or neurological dysfunction, intellectual disability, or current substance dependence. Extensively trained clinical psychology graduate students conducted the diagnostic interviews and all interviews were audio recorded. For a random subset of 20 participants, a second rater listened to the audio-recordings and provided independent diagnostic ratings. The interrater reliabilities were high for both a diagnosis of BPD (κ = .90) and a current mood disorder (κ = 1.00). In the BPD group, 50 individuals (62.5%) met criteria for a current comorbid mood disorder. Specifically, 25 individuals (31.3%) endorsed current major depression, 14 (17.5%) current dysthymia, and 18 (25%) current bipolar disorder. Details on comorbid conditions, ethnicity, marital status, and annual income of participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data and descriptive statistics for the main study variables health problems, negative affect, and interpersonal problems by Group (N =131).

|

BPD (n = 80) |

DD (n = 51) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/M | %/SD | n/M | %/SD | |

| Age | 32.1 | 11.7 | 34.5 | 12.0 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 74 | 92.5% | 40 | 78.4% |

| Male | 6 | 7.5% | 11 | 21.6% |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African-American | 5 | 6.3% | 4 | 7.8% |

| Hispanic | 3 | 3.8% | 2 | 3.9% |

| Caucasian | 67 | 83.3% | 44 | 86.3% |

| Native American | 0 | 0% | 1 | 2.0% |

| Asian-American | 2 | 2.5% | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 1 | 1.3% | 0 | 0% |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single, Never Married | 41 | 51.3% | 23 | 45.1% |

| Married | 13 | 16.3% | 13 | 25.5% |

| Cohabitating | 9 | 11.3% | 6 | 11.8% |

| Divorced or Separated | 17 | 21.3% | 9 | 17.7% |

| Annual Income | ||||

| $0 to $25,000 | 57 | 71.3% | 35 | 68.6% |

| $25,001 to $50,000 | 12 | 15.0% | 10 | 19.6% |

| $50,001 to $75,000 | 5 | 6.3% | 3 | 5.9% |

| $75,001 to $100,000 | 4 | 5.0% | 1 | 1.9% |

| Above $100,000 | 2 | 2.5% | 2 | 3.9% |

| Currently Employeda | 39 | 48.8% | 24 | 47.1% |

| Current Axis-I Comorbidity | ||||

| Any mood disorderb | 50 | 62.5% | 51 | 100% |

| Any anxiety disorder | 63 | 78.8% | 34 | 66.7% |

| Any eating disorder | 18 | 22.5% | 3 | 5.9% |

| Any substance use disorder | 14 | 17.5% | 3 | 5.9% |

| Current Axis-II Comorbidity | ||||

| Any PD other than Borderline | 74 | 92.5% | 20 | 39.2% |

| Narcissistic PD | 8 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Histrionic PD | 7 | 8.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Antisocial PDc | 18 | 22.5% | 2 | 3.9% |

| Schizotypal PD | 2 | 2.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Schizoid PD | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Paranoid PD | 11 | 13.8% | 1 | 2.0% |

| Avoidant PD | 28 | 35.0% | 16 | 31.4% |

| Dependent PD | 8 | 10.0% | 2 | 3.9% |

| Obsessive Compulsive PD | 19 | 23.8% | 6 | 11.8% |

| Ever hospitalized | 46 | 57.5% | 18 | 35.3% |

| Number of hospitalizations | 4.9 | 7.8 | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| Currently in outpatient treatment | 75 | 93.8% | 48 | 94.1% |

| Months ever in outpatient treatment | 36.9 | 57.8 | 35.0 | 42.4 |

| Health problemsd | ||||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Ache symptoms | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Depression symptoms | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Total health problems | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Negative affectd | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| Interpersonal problemsd | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

Note. BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; DD = Depressive Disorder.

Employment information was unavailable for 2 individuals in the DD group and 1 individual in the BPD group.

There were 3 BPD individuals with unavailable Axis I and II diagnostic data, with the exception that 2 of these individuals did provide data for the mood disorder category.

For Antisocial PD, only Criterion A was assessed. Health problems and interpersonal problems means represent the average number of problems that were endorsed at any given prompt.

Values represent sample averages and standard deviations after aggregating ambulatory assessment reports to the person level.

Procedure and Measures

During an initial orientation session, participants were instructed in the use of a handheld computer (Palm Zire 31®), which was used to collect momentary data, and completed a number of self-report trait measures not pertinent to the current investigation. Participants carried the handheld computer for approximately 28 days and were prompted to enter data at six random time-points throughout their wake-time (see 21 for further details). Participants completed an average of 143.7 (Range=72–183) prompts each (NBPD=144.0, NDD=143.2), which resulted in an excellent average compliance rate of 85.5% (Range=43%−100%).

Momentary affect assessment

At each random prompt, momentary NA was assessed using the negative affect scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Extended version (PANAS-X, 24). The 21 items were rated on a five point Likert-type scale (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely) and averaged to form an overall index of NA. Additionally, we created daily averages within each person and a person average. Reliability estimates indicated excellent reliability for average person ratings across measurements (RKF=.98) and detecting momentary levels of NA within a given assessment (R1R=.91) (25).

Interpersonal stressors

At each random prompt, participants indicated whether they had had a disagreement, felt rejected, or felt let down by another person since they were last prompted. We chose these variables because they closely reflect the constructs of relationship conflict and lack of social support that have previously been found to be associated with HP in non-clinical samples (12–14). Participants could choose between different interaction partners (romantic partner, boss, co-worker, roommate, friend, parent, sibling, child, family member). To create an overall index for IS, we created a single dichotomous variable that indicated whether any rejection, disagreement, or instance of feeling let down (independent of the interaction partner) had taken place. Thus, if any of the three events occurred, this variable was 1 and if none occurred it was 0. The momentary variable was then aggregated into a variable indicating the proportion of prompts at which IS occurred within each day. Lastly, these day means were aggregated by person to obtain a variable indicating the proportion of days on which IS occurred. Participants in the BPD group reported a total of 2,979 occasions where at least one IS occurred (26% of prompts in the BPD group), and DD participants reported 1,621 such occasions (22% of prompts in the DD group). The groups did not differ significantly in the amount of IS reported, t(129)=1.06, p=.291.

Health problems

At each prompt, individuals reported momentary HP on four dimensions (gastrointestinal-, respiratory-, depression-related symptoms, and aches) on the Physical Symptom Checklist (18), which was originally designed to assess HP in daily diary studies and adapted to the AA context. To reduce participant burden, we asked participants to indicate the presence or absence of only two to three items for each domain. The items included nausea, stomachache, and feeling dizzy (gastrointestinal)1, cold and allergy symptoms (respiratory), headache and muscle ache (aches), and problems concentrating and fatigue (depression). For each of the four domains, we created a variable ranging from 0 to 2 (and 0 to 3 in the case of gastrointestinal symptoms), indicating how many symptoms were endorsed at any given occasion. Following Shrout and Lane (25), the reliabilities of individuals’ average health ratings across the diary period were excellent (all RKFs>.98). The reliabilities for random single occasion measurements were excellent for respiratory symptoms (R1R=.95), adequate for depressive symptoms (R1R=.70) and aches (R1R=.74), and fair for gastrointestinal symptoms (R1R=.51). Reliabilities at the day level were adequate for all four scales (depressive R1R=.73, gastrointestinal R1R=.62, ache R1R=.72, respiratory R1R=.64).2

Data analysis

To test the proposed moderated mediation model of IS predicting momentary HP via NA, and BPD group membership moderating this process, we employed multivariate multilevel models (MMLM). The models comprised two parts, one in which NA was the dependent variable, predicted by IS (a path)3 and another part in which HP were the dependent variable, predicted by NA (b path) and IS (c’ path). We ran four MMLMs, one for each of the HP domains.4

Momentary NA was regressed on momentary (day-centered) IS, and the model additionally adjusted for daily (person-centered), and person-average (group-centered) IS to disaggregate the multiple levels of clustering within measures. IS were interacted with group (dummy-coded for BPD vs. DD) at all levels. Likewise, momentary HP were regressed on momentary IS and NA, and again daily-, and person-level IS and NA were adjusted for. IS and NA were interacted with group at all levels.

We modelled random intercepts and momentary slopes (momentary IS when both NA and HP were dependent variables, and momentary NA when HP was the dependent variable) for each person. All models included the following covariates: six dummy-variables coding weekday, a dummy-variable for weekend (5PM Friday through 5PM Sunday), study day (continuous, 0 through 27), time elapsed since the participant awoke (continuous), and a dummy-variable coding whether the participant reported taking any over-the-counter medication for physical symptoms since the last report. Analyses were performed using the MIXED procedure in SAS 9.4 and bootstrapped confidence intervals were calculated for the indirect effects using the indtest macro (26).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Participants provided a total of 18,820 prompts. At any given moment, participants reported an average of 2.09 HP out of the possible nine (bSD=1.98; wSD=1.17). Across the approximately 28 days, participants reported at least one HP on an average of 24.8 days (SD=5.8; 89.9%). There was substantial variability of endorsement across subscales, with depression symptoms endorsed most frequently, and respiratory symptoms least frequently. Means and SDs across the study period are presented in Table 1.

Effect of IS on NA (a-path)

Results for the a-path of the mediation model, that is, the effects of IS and group on NA, are presented in Table 2. The effects were almost identical for the four different HP dimensions, so they are only presented once (for depressive problems). Interpersonal stressors were positively associated with NA at the momentary-, day-, and person-level. The effect of day-level IS was significantly stronger for the BPD than the DD group, but there was no group difference in this effect at the momentary- or person-level.

Table 2.

Interpersonal stressors, group, and their interaction predicting momentary negative effect in a multilevel-model; effects represent the a-path of the mediation model.

| Predictor | Est. | βa | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Momentary IS | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Day-level IS | 0.73 | 0.19 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Person-level IS | 1.78 | 0.47 | 0.23 | <.001 |

| Group | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | .782 |

| Group×momentary IS | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 | .353 |

| Group×day-level IS | −0.19 | −0.05 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Group×person-level IS | −0.76 | −0.20 | 0.44 | .083 |

Note. Est.=Estimate, IS=interpersonal stressors. Group was coded 0 for borderline personality disorder and 1 for depressive disorder. Results reported are those corresponding to the multivariate multilevel model where the depressive HP domain was the parallel dependent variable to negative affect. Parameter estimates and significance levels for the IS→NA portion of the model remain virtually unchanged for models in which the other HP domains were the parallel dependent variable.

βs were estimated by between-person standardizing variables so that effects could be interpreted on an average between-person partial-r metric.

Effect of NA on HP (b-path)

The effects of NA on HP (b-path) are presented in Table 3. Note that the table only displays the main effects for NA in the BPD group, which was coded as the baseline of the group-dummy predictor. NA was significantly positively associated with HP at both momentary and day levels for all four HP domains. At the person level, BPD individuals who reported higher average levels of NA across the study period tended to also report more depressive and aching symptoms at any given moment, but not more respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. With regard to group differences, BPD individuals exhibited a significantly stronger positive association between daily NA and respiratory symptoms, while DD individuals displayed a stronger positive association between daily NA and depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Interpersonal stressors, negative affect, and group predicting momentary HP in a multilevel-model; effects of negative effect on HP represent the b-path in the mediation model and effects of interpersonal problems on HP represent the c’-path in the mediation model,.

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Respiratory Symptoms | Aches | Depressive Symptoms | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Est. | β | SE | p | Est. | β | SE | p | Est. | β | SE | p | Est. | β | SE | p |

| Group | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.08 | .433 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | .438 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.09 | .826 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 | .653 |

| NAm | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .046 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| NAd | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .006 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.01 | <.001 |

| NAp | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.22 | .812 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.15 | .853 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 0.15 | .005 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.18 | .032 |

| Group×NAm | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.06 | .210 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | .182 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | .824 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | .060 |

| Group×NAd | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | .984 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 | .025 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .855 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Group×NAp | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.42 | .934 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.29 | .782 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.29 | .976 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.33 | .780 |

| ISm | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .944 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .064 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .024 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .048 |

| ISd | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .018 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .152 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| ISp | 0.92 | 0.16 | 0.49 | .116 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.34 | .651 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.38 | .958 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.41 | .841 |

| Group×ISm | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | .776 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | .256 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | .928 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .318 |

| Group×ISd | −0.14 | −0.03 | 0.05 | .003 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | .229 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | .156 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.04 | .123 |

| Group×ISp | −0.74 | −0.16 | 0.78 | .390 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.52 | .976 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.64 | .853 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.66 | .929 |

Note. Est.=Estimate, IS=interpersonal stressor, Group=0 for borderline personality disorder and Group=1 for depressive disorder, NA=Negative Affect. Subscriptm=momentary predictor, subscriptd=day level predictor, and subscriptp= person-level predictor.

βs were estimated by between-person standardizing variables so that effects could be interpreted on an average between-person partial-r metric.

Effect of IS on HP (c’-path)

Effects for the c’-path are presented in Table 3, again noting that the table displays the main effects for IS in the BPD group. When predicting gastrointestinal symptoms, IS (independent of NA) showed a significant positive effect at the day level for the BPD group and this effect was significantly stronger than in the DD group. In addition to this, there were a number of other significant associations between IS and HP, but these did not differ significantly between groups as non-significant IS×group interactions indicated. Specifically, day-level IS showed a significant positive association with respiratory symptoms, momentary IS showed a positive association with aches, and momentary, as well as day-level IS were positively associated with depressive symptoms. Overall, there were no significant effects or group differences at the person level.

Moderated Mediation

Consistent with the model depicted in Figure 1, we estimated the indirect effects of IS on HP through NA. We did this for each group at the momentary, day, and person-level. Table 4 displays the unstandardized indirect effect estimates and 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals for each of the four health domains. Significant indirect effects of IS on HP (via NA) were present at the momentary and day levels for gastrointestinal, aching, and depressive health symptoms in both groups. Regarding respiratory symptoms, indirect effects of IS were significant for the BPD group at the day level. Indirect effects of IS at the person level were observed for aching and depressive symptoms for the BPD group.

Table 4.

Indirect effect estimates for BPD and DD individuals by HP domain.

| HP | BPD | DD | Group Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | |

| Gastro-Intestinal | Moment | .09 | [.06,.11] | .06 | [.03,.09] | .03 | [−.01,.07] |

| Day | .13 | [.11,.16] | .10 | [.07,.13] | .03 | [.00,.07] | |

| Person | −.09 | [−.86,.67] | −.09 | [−.91,.69] | −.00 | [−1.07,1.10] | |

| Respiratory | Moment | .01 | [−.00,.01] | −.00 | [−.01,.01] | .01 | [−.00,.02] |

| Day | .02 | [.01,.03] | −.00 | [−.02,.01] | .02 | [.01,.04] | |

| Person | −.05 | [−.60,.50] | .06 | [−.46,.61] | −.11 | [−.86,.63] | |

| Aches | Moment | .04 | [.03,.06] | .03 | [.02,.05] | .01 | [−.02,.03] |

| Day | .08 | [.06,.10] | .06 | [.04,.09] | .02 | [−.01,.05] | |

| Person | .80 | [.26,1.43] | .43 | [−.03,1.13] | .37 | [−.51,1.17] | |

| Depressive | Moment | .06 | [.05,.08] | .08 | [.05,.10] | −.01 | [−.04,.02] |

| Day | .15 | [.13,.17] | .17 | [.14,.20] | −.02 | [−.06,.01] | |

| Person | .69 | [.07,1.40] | .49 | [−.06,1.31] | .20 | [−.79,1.12] | |

Note. BPD=Borderline Personality Disorder group, DD=depressive disorder group, Est.=Estimate. Significant estimates are marked in bold (i.e. the 95% confidence interval did not include zero).

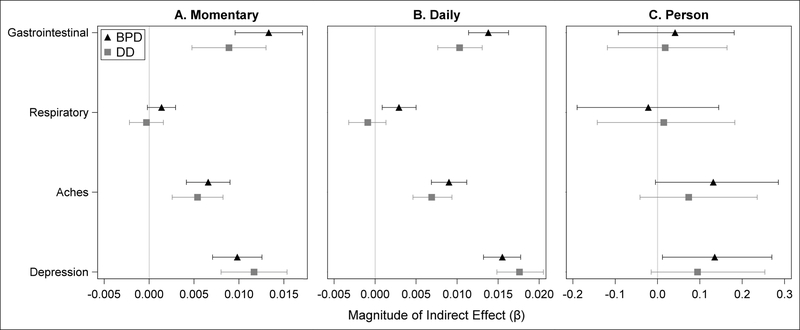

To test whether group membership moderated these indirect effects of IS on HP, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations of the estimated indirect effect parameters for each group and constructed a probability distribution of the estimated difference in the indirect effects. For the momentary and daily level, the indirect effects were larger in the BPD group for gastrointestinal, respiratory, and aching symptoms, while they were larger in the DD group for depressive symptoms. However, only at the daily level did any of these conditional indirect effect group differences reach statistical significance, such that the effect of daily IS on daily NA and then gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms was stronger for the BPD group. The effect of daily IS on daily NA and then aching symptoms was marginally stronger for the BPD group, and on daily NA and then depressive symptoms was marginally stronger for the DD group, but neither reached conventional levels of significance. Figure 2 presents a plot of the between-person standardized indirect effects to facilitate comparisons across domains, diagnostic groups, and levels of analysis.

Figure 2.

Standardized indirect effect estimates of the association between IS and HP via NA. Within domain, borderline (BPD) and depressed (DD) effects are compared at A) momentary, B) day, and C) person levels. Error bars represent 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Discussion

The current investigation sought to further understand the associations between IS and HP via the experience of NA, and their temporal relationship in particular. We examined differences in these associations between a group of individuals with BPD and a depressed comparison group, because both groups are characterized by interpersonal stress, elevated NA, and HP (5, 6, 11, 17, 19, 20), seeking to determine whether there is specificity in the IS↔NA↔HP association for BPD.

In general, we found evidence that IS are associated with higher levels of NA and, thereby, contribute to higher levels of HP at both momentary and daily levels of experience for BPD and DD individuals. It is noteworthy that the momentary and everyday nature of HP assessed here differ from those previously examined in cross-sectional studies, which focused more macroscopically on chronic conditions or serious illnesses (4–9, 11). In this way, the present study adds to the existing literature because it demonstrates that individuals with BPD, and DD, are not only prone to serious and chronic illness, but also experience a substantial amount of everyday HP. In fact, participants in both groups reported an average of approximately two HP at any given assessment. While these may be relatively minor in isolation, the accumulation of such symptoms over time may create meaningful reductions in functioning and potentially contribute to the more severe health issues that have been observed in cross-sectional studies.

The finding that we only observed consistent group differences at the day level, which diverges from our initial focus on momentary fluctuations, suggests that there may be an accumulative process over time that was not present to the same degree in DD participants. That is, while DD participants may have felt negative physical effects in the moment of interpersonal problems and NA, they may have been able to move on and return to more normal functioning more quickly than BPD individuals, for whom these effects tended to affect the whole day. This is consistent with conceptualizations of emotion dysregulation in BPD, which posit that BPD individuals experience a slow return to baseline after experiencing NA (15), and tentatively suggests the same might be true for physical health symptoms.

Despite the generally consistent findings, there are a number of limitations associated with the current study. Across all analyses, effect size estimates for individual and indirect paths (especially for respiratory problems) were generally small to very small, with the sizes smaller at lower levels of analysis. While these estimates individually range from 0.1 to 1.0% of the total variance across levels, we would argue that they still index substantively meaningful patterns. Standardization in clustered designs often overlooks the relative proportions of variance that are observed across levels, which implicitly obscures the fact that much of the variance is at the momentary level (34–50%; see supplementary material, Table S3). At this level, even small amounts of total systematic variability can be meaningful when instead put in the context of unique moment-to-moment variance (e.g., standardized effects would be multipled by a factor of 2–3 in the current analyses). Individuals experience myriad changing contexts in daily life (e.g., at home/work, with others or alone, using substances) that are not accounted for in our models, which will increase unexplained variability and reduce overall effect sizes.

Moreover, the observed effects are limited in their causal interpretation. The presented results are from analyses that used self-reports all collected at the same assessment, so we lack temporal ordering and resolution regarding the proposed process. Both IS and NA were assessed in terms of their experience since the last prompt, while health problems were assessed currently. Given their respective wording, it is feasible that health problems represent a consequent, but we did not assess when the specific experiences started. We were able to establish a more refined time-sequence of events in followup lagged analyses, such that IS was associated with HP at the following time-point, as mediated by NA (15; see supplementary material, Tables S1–S2 and Figures S1–S2), but even this does not preclude a separate confounding cause of both IS and NA (e.g., substance use) as correlated, as opposed to ordered, mechanisms.

An additional limitation is that we cannot say whether IS, via increases in NA, led to an actual increase in HP, or whether IS and NA simply rendered participants more likely to report preexisting HP. That is, participants could either have reported HP that was already present but less noticeable when participants were in a good mood, or reported HP may have been a physical consequence of IS, via elevated NA levels. Ultimately, we cannot distinguish these possibilities with the present data as it would require more objective measurement of HP, in order to examine biological changes in response to elevated IS and NA. Future studies should consider assessing HP via portable physical sensors, saliva samples, or other means that can capture aspects of HP in the moment.

A further possible limitation is the co-occurrence of depressive disorders in the BPD group, which may have contributed to the effects observed for this group. Individuals with BPD are typically affected by a high number of co-occuring conditions and depression is one of the most frequent. Thus, recruiting a sample of BPD individuals without comorbidity is not only almost impossible but also likely to reflect a very untypically healthy sample. We would argue that by including a depressed control group, the stronger effects we observed for the BPD group should reflect pathology that goes even beyond what depressive symptoms in the BPD group potentially added. Moreover, we did not have information about participants’ overall physical health, including possible chronic conditions. Since chronic illness is prevalent in BPD (4–8) it is possible that some HP occurred within the broader context of a chronic illness and that these differ from minor HP outside of chronic disease. Future studies should address chronic illnesses and assess their influence on everyday HP. Finally, the predominantly female sample limits our ability to generalize the current findings to men with BPD or depression.

Implications

In the current investigation we found evidence consistent with a pathway of IS contributing to momentary and daily HP through NA in individuals with BPD and depression. These findings go beyond previous evidence on cross-sectional assocations between health conditions and BPD (4–9, 11) and also extend previously daily-life studies by including IS and assessing the temporal dimension of the IS↔NA↔HP association. We observed relatively transdiagnostic patterns, but additional specificity for BPD individuals regarding gastrointestinal and respiratory problems.

Our results can be used to inform both prevention and intervention efforts, perhaps by implementing affective/behavioral awareness strategies and regulation tactics that address NA that is associated with the experience of IS. If successful, these efforts might alleviate not only NA, but also downstream HP that entail a high burden on health care systems (e.g., 6) and likely contribute to the high mortality rates and decreased life expectancies for these groups (2, 3). In that regard, future studies should also go beyond looking at mere levels of NA and assess momentary regulatory efforts and how different regulation strategies may help to protect against HP manifestation.

Moreover, it seems highly likely that the IS↔NA↔HP relationship we observed herein for BPD and depression would also apply to other mental health conditions that are strongly characterized by NA and IS. In this case, addressing interpersonal functioning in therapeutic settings could be beneficial not only for mental but also for physical health, thus rendering changes in physical health an important treatment outcome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors identify no conflicts of interest. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health research grants R21 MH069472 (Trull), P60 AA11998 (Trull/Andrew C. Heath), T32 AA013526 (Sher), T32 AA007459, (Monti).

Abbreviations

- BPD

Borderline personality disorder

- HP

Health problems

- NA

Negative affect

- IS

Interpersonal stressors

- AA

Ambulatory assessment

- DD

Depressive disorder

Footnotes

Note that “nausea” and “upset stomach” were combined into a single item in the original article. We separate them in the current checklist, which led to three items instead of two. Additionally, we initially questioned the face-validity of the “dizziness” item as a gastrointestinal symptom. However, factor and reliability analyses of the current dataset indicated that it contributed consistently to an overarching factor with the other two items.

We conducted two multilevel factor analyses to alternatively examine if the health problem items were better characterized by a single overarching factor. A confirmatory approach with the items loading onto the corresponding four factors at both the within- and between-person levels fit the data adequately (χ2(42)=447.11, RMSEA=.02, CFI=.89, SRMRwithin=.03, SRMRbetween=.07, Scaling Correction Factor=2.26) whereas a single global factor fit the data less well (χ2(54)=698.25, RMSEA=.03, CFI=.82, SRMRwithin=.04, SRMRbetween=.08, Scaling Correction Factor=2.66), particularly when using the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 test (χ2(12)=208.56, p<.001). Moreover, estimating the reliability of the measure aggregating across the nine items as opposed to splitting them into their component subscales resulted in approximately equal (RKF=.99) or lower (R1R=.65) reliability despite the expected reduction in error variance when aggregating across more than three times as many items (c.f. Spearman-Brown formula).

This arm of the mediation model represents a partial reproduction of an analysis we report elsewhere (25). In the current article, we combine across the different negative affect ratings to create an overall index instead of separating the ratings into three respective subscales (hostility, fear, sadness). We do so because the additional level of detail based on specific negative affect type did not lead to differential patterns of results in terms of the effects on HP reports or the estimated indirect effects. In addition, we include feelings of being let down in the interpersonal problems composite.

We note that given the relatively skewed distribution of NA and the count nature of HP, normality assumptions when treating each as dependent variables are likely violated. In the initial modeling stages we log transformed each and also separately modeled each using a Poisson distribution to examine the impact of such violations. However, visual and descriptive results suggested that NA was not extremely skewed and that HP were experienced with sufficient frequency (~50%) to approximate a normal distribution. In each case, the rescaled coefficient estimates and patterns of significance from the MMLMs remained consistent with those reported in the main results using a multivariate normal distribution.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:153–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fok M, Hotopf M, Stewart R, Hatch S, Hayes R, Moran P. Personality disorder and self-rated health: a population-based cross-sectional survey. J Pers Disord. 2014;28:319–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Gabalawy R, Katz LY, Sareen J. Comorbidity and associated severity of borderline personality disorder and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:641–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruitt PJ, Boudreaux MJ, Jackson JJ, Oltmanns TF. Borderline Personality Pathology and Physical Health: The Role of Employment. PD:TRT. 2016;9:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Chronic pain syndromes and borderline personality. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9:10–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gratz KL, Weiss NH, McDermott MJ, Dilillo D, Messman-Moore T, Tull MT. Emotion dysregulation mediates the relation between borderline personality disorder symptoms and later physical health symptoms. J Pers Disord. 2017;31:433–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds CJ, Carpenter RW, Tragesser SL. Accounting for the Association Between BPD Features and Chronic Pain Complaints in a Pain Patient Sample: The Role of Emotion Dysregulation Factors. PD:TRT. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tragesser SL, Bruns D, Disorbio JM. Borderline personality disorder features and pain: the mediating role of negative affect in a pain patient sample. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakey B, Orehek E. Relational regulation theory: a new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol Rev. 2011;118:482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadler G, Snyder KA, Horn AB, Shrout PE, Bolger NP. Close relationships and health in daily life: A review and empirical data on intimacy and somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hepp J, Lane SP, Wycoff AM, Carpenter RW, Trull TJ. Interpersonal stressors and negative affect in individuals with borderline personality disorder and community adults in daily life: A replication and extension. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127:183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berenson KR, Downey G, Rafaeli E, Coifman KG, Paquin NL. The rejection–rage contingency in borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen RJ, Kasimatis M. Day-to-Day Physical Symptoms: Individual Differences in the Occurrence, Duration, and Emotional Concomitants of Minor Daily Illnesses. J Pers. 1991;59:387–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.aan het Rot M, Hogenelst K, Schoevers RA. Mood disorders in everyday life: A systematic review of experience sampling and ecological momentary assessment studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:510–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trull TJ, Solhan MB, Tragesser SL, Jahng S, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, Watson D. Affective instability: Measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. Iowa City: University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders - patient ed. (SCID-I/P, version 2) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrout P, Lane SP. Psychometrics In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. p. 302–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2006;11:142–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.