INTRODUCTION

Numerous health organizations and researchers support including e-cigarettes in smokefree legislation due to the potential risks associated with exposing non-users to chemicals in exhaled aerosol and renormalizing smoking.1,2 Another potential risk of indoor e-cigarette use is setting off smoke detectors. E-cigarette users exhale an aerosol of particulates and chemicals3–5, which can trigger both ionization and photoelectric-based smoke detectors. National fire surveillance systems collect reports of smoke detector false alarms. However, there is no reportable code for e-cigarettes (personal correspondence, Lawrence McKenna, PhD, U.S. Fire Administration). Therefore, the extent to which e-cigarette use is setting off smoke detectors remains unclear. However, recent media reports suggest this is an emerging issue, as e-cigarette use has been setting off smoke detectors in a variety of environments, including airports, high schools, and university dorms.6–10 Additionally, social media posts also describe e-cigarette use triggering smoke alarms (Supplement 1). Little is known about public perceptions of e-cigarettes setting off smoke detectors.

METHODS

We recruited a convenience sample of adults (≥18 years) through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to complete an online questionnaire in March of 2017. Screening questions and quotas were used to ensure half of the sample were current smokers. We asked participants “Do you think that using an e-cigarette indoors can set off a smoke alarm?” Participants were next asked the same question about combustible cigarettes. Chi-square tests were used to assess differences in responses by product and e-cigarette use status.

RESULTS

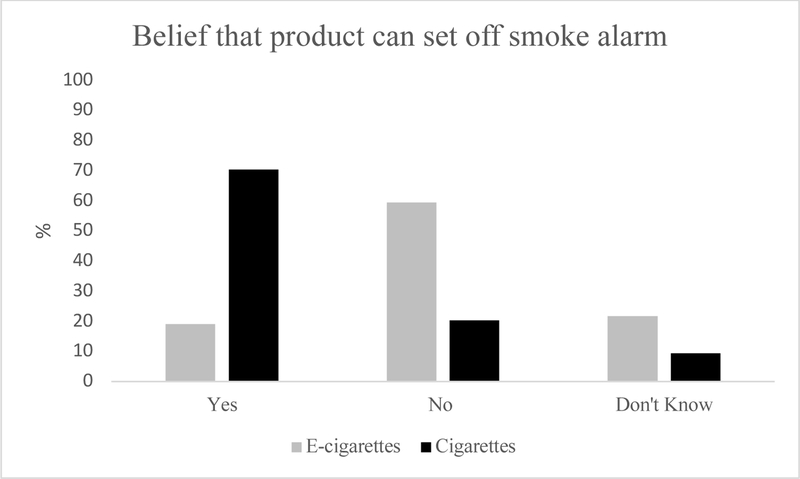

All participants (n=843) resided in the US, a majority were male (56%), 81% identified as White, 41% were ≤ 29 years of age, and 51% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Forty-nine percent of participants were current smokers and 36% reported current e-cigarette use. While 70% of participants believed indoor cigarette smoking could set off a smoke detector, <20% believed indoor e-cigarette use could (p<0.001; Figure 1). Among current e-cigarette users, 20% believed that e-cigarettes could set off a smoke detector, compared to 19% of non-e-cigarette users (p=0.758).

Figure 1.

Percent of participants believing that e-cigarette and cigarette use indoors can set off a smoke detector.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to assess perceptions of e-cigarette use setting off smoke detectors. Belief that e-cigarette use can set off smoke detectors was found to be low among both e-cigarette users and non-users. Such low beliefs may be encouraging e-cigarette use in indoor environments where use is prohibited (e.g., airports, high schools), potentially exposing non-users to exhaled aerosol. These findings suggest that educational campaigns are needed to inform the public that indoor e-cigarette use can trigger smoke detectors. While we are aware of one leading e-cigarette brand website (blu) acknowledging the risk of setting off a smoke detector in the past year, additional efforts are needed.11 Further, to help understand the scope of this problem, a reportable code for e-cigarettes should be created to track false alarms caused by e-cigarettes.

This study was limited by the use of a convenience, non-representative sample. In addition to protecting non-smokers from secondhand aerosol, including e-cigarettes in smokefree laws may help reduce smoke detector false alarms, unnecessary evacuations, and wasting of financial and fire-related resources associated with e-cigarettes setting off smoke detectors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31DA045424. Additional support provided by the UNC Lineberger Cancer Control Education Program (T25 CA057726). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ribisl KM, Seidenberg AB, Orlan EN Recommendations for U.S. Public Policies Regulating Electronic Cigarettes. J Policy Anal Manage. 2016;35(2):479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Ribisl KM, et al. Electronic cigarettes: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(16):1418–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez E, Ballbe M, Sureda X, Fu M, Salto E, Martinez-Sanchez JM. Particulate Matter from Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Cigarettes: a Systematic Review and Observational Study. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2(4):423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schober W, Szendrei K, Matzen W, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) impairs indoor air quality and increases FeNO levels of e-cigarette consumers. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217(6):628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melstrom P, Koszowski B, Thanner MH, et al. Measuring PM2.5, Ultrafine Particles, Nicotine Air and Wipe Samples Following the Use of Electronic Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(9):1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.1938 News. Connecticut High School Evacuates Students into the Cold After E-cig Using Teens Set Off Fire Alarm. http://1938news.com/connecticut-high-school-evacuates-students-into-the-cold-after-e-cig-using-teens-set-off-fire-alarm/. Published December 10, 2014. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- 7.Christie S. Stansted Airport ‘chaos’ after passenger sets off fire alarm by smoking e-cigarette in a toilet. The Sun. February 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.KXAN. E-cig forces evacuation at Austin airport. http://kxan.com/2016/03/14/e-cig-forces-evacuation-at-austin-airport/. Published March 14, 2016. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- 9.WNCN Staff. E-cigarette sets off alarms at Middle Creek High School. http://wncn.com/2016/01/27/e-cigarette-sets-off-alarms-at-middle-creek-high-school/. Published 2016. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- 10.Romeo T. E-cigarettes setting off fire alarms in dorms. The Stute. April 17, 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.blu. Do e-cigarettes set off fire alarms?Available:https://www.blu.com/en/US/explore/explore-vaping/vaping-locations-regulations/do-ecigarettes-set-off-fire-alarms.Accessed May 31,2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.