Abstract

Background.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have pro-tolerogenic effects in renal transplantation, but they induce long-term Treg-dependent graft acceptance only when infused before transplantation. When given posttransplant, MSCs home to the graft where they promote engraftment syndrome and do not induce Tregs. Unfortunately, pretransplant MSC administration is unfeasible in deceased-donor kidney transplantation.

Methods.

To make MSCs a therapeutic option also for deceased organ recipients, we tested whether MSC infusion at the time of transplant (day 0) or posttransplant (day 2) together with inhibition of complement receptors prevents engraftment syndrome and allows their homing to secondary lymphoid organs for promoting tolerance. We analyzed intragraft and splenic MSC localization, graft survival and alloimmune response in mice recipients of kidney allografts and syngeneic MSCs given on day 0 or on posttransplant day 2. C3aR or C5aR antagonists were administered to mice in combination with the cells or were used together to treat MSCs before infusion.

Results.

Syngeneic MSCs given at day 0 homed to the spleen, increased Treg numbers and induced long-term graft acceptance. Posttransplant MSC infusion, combined with a short course of C3aR or C5aR antagonist or administration of MSCs pretreated with C3aR and C5aR antagonists prevented intragraft recruitment of MSCs and graft inflammation, inhibited anti-donor T-cell reactivity, but failed to induce Tregs, resulting in mild prolongation of graft survival.

Conclusion.

These data support testing the safety/efficacy profile of administering MSCs on the day of transplant in deceased-donor transplant recipients and indicate that complement is crucial for MSC recruitment into the kidney allograft.

Introduction

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs), a population of undifferentiated multipotent adult stem cells, can regulate the activity of a range of effector cells involved in the innate1 and adaptive immune responses, including macrophages,2-4 NK cells,5,6 dendritic cells7,8 and T lymphocytes.9 MSCs are therefore attractive candidates for cell therapy in organ transplantation to induce immunological tolerance and prevent or minimize the need for lifelong, potentially toxic, immunosuppressive drugs.

In animal models of heart,10-12 liver,13 islet14-16, kidney17-19 and composite tissue20 transplantation, MSCs promoted donor-specific tolerance through the generation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells. In human recipients of kidney transplants from living donors, bone marrow-derived MSC infusion is feasible and safe, promotes a pro-tolerogenic environment21-23 and allows to prevent acute rejection with lower than conventional doses of anti-rejection therapy.23-26

Despite these promising results, the optimal timing of cell administration in relation to transplantation remains unclear. The available evidence indicates that MSC immunomodulatory properties depend on the microenvironment these cells encounter in the organ where they are recruited,27 which dictates whether MSCs acquire an anti-inflammatory28 or a pro-inflammatory29 phenotype. In a previous study in humans, we documented that systemic infusion of bone marrow (BM)-derived autologous MSCs 7 days postkidney transplantation was associated with a transient impairment of graft function associated with intragraft recruitment and activation of MSCs, followed by neutrophil infiltration and complement C3 deposition.21 This clinical manifestation was similar to the “engraftment syndrome” described in kidney transplant patients given a combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation to induce tolerance, and characterized histologically by endothelial injury and modest cellular infiltrate.30 We subsequently embarked on a series of ad hoc translational studies in a mouse model of kidney transplantation designed to identify the ideal timing for MSC infusion. MSCs infused on day −1 pretransplant mainly localized in the spleen and induced significant prolongation of graft survival through a Treg-dependent mechanism.18 Conversely, when injected on day +2 after transplant, a higher number of MSCs localized in the graft, leading to neutrophil infiltration and complement deposition, with no benefit in graft survival.18,21

These experimental findings, together with the preliminary clinical results suggest that MSCs, when given to promote tolerance in human transplantation, should be administered before transplant. This approach, however, is not feasible in deceased-donor kidney transplantation because transplant surgery takes place a few hours after a donor organ becomes available. Since MSCs infused in transplant patients are either autologous or obtained from third party healthy individuals, it would be possible to infuse previously collected and stored cells on the day of transplant or soon after transplant.

To make MSC therapy applicable to deceased-donor kidney transplant recipients, here we tested two alternative strategies in a murine kidney transplant model: i) infusion of MSCs on the day of transplant and ii) constrain MSCs infused posttransplant from localizing into the graft. If effective, both strategies would be of the utmost importance for the clinical implementation of MSC therapy in kidney transplants from deceased donors, which account for over half of the donor pool.31

Based on evidence that human MSCs express complement protein receptors,32 that complement components act as chemoattractants for these cells,32,33 and that MSCs given posttransplant co-localized with complement deposits,18 we tested the hypothesis that antagonizing complement receptors on MSCs given on day +2 posttransplant prevents their recruitment into the graft, avoids MSC-induced graft inflammation, reorients MSC homing to recipient spleen and prolongs long-term graft survival.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods for kidney transplantation, MSC isolation, detection of infused MSC in recipient organs, flow cytometry analysis, immunohistochemistry and immune assays can be found in the Supplementary methods section.

Mice

Eight-to-ten-week-old female C57BL/6 (BL6, H-2b) and BALB/c (H-2d) mice were obtained from Charles River (Calco, Italy). BL6 mice were used as either BM donors or as recipients of kidney allografts from BALB/c donors. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in conformity with the Institutional Guidelines in compliance with national (D.L. n.26 march 4, 2014, G.U., number 61, March 14, 2014) and International Law and Policies (EEC Council Directive 2010/63/EU, 9/22/2010; Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Academy Press, 1996). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Experimental groups

All recipient BL6 mice were sensitized toward donor antigens through the injection of donor BALB/c splenocytes (1×106, i.v.) seven days prior to receiving a BALB/c kidney allograft.34 Recipient sensitization resulted in increased anti-donor reactive T cells and in acute graft rejection in all transplanted mice.20 To evaluate whether intragraft localization of MSCs involves C3aR and/or C5aR activation, we studied recipient BL6 mice given PKH26-labelled MSCs (1×105, i.v.) alone 2 days after kidney transplantation (MSCs day2, n=3) or together with a short course of the C3a receptor antagonist (MSCs day2 + C3aR-A, n=3) or the C5a receptor peptide antagonist (MSCs day2 + C5aR-A, n=3). C3aR-A (SB 290157, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was administered thrice over 24 hours, that is, 2 hours before MSC infusion (i.p.), together with MSCs (i.v.) and then 12 hours later (i.p.) at the dose of 15 mg/kg per injection.35,36 Similarly, C5aR-A [Ac-Phe-cyclo(Orn-Pro-dCha-Trp-Arg) from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ)] was administered to recipient mice following the same protocol of C3aR-A at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg per injection.35 Additional mice were given MSC preexposed in vitro to C3aR-A and C5aR-A (n=3) or to vehicle (n=3) at day 2 after transplantation. For these experiments, MSC were preexposed to 100 μg/mL C3aR-A and to 3.5 μg/mL C5aRA or vehicle during the last two days of culture MSC. Cells were then labelled with PKH26, preincubated for an additional hour with C3aR-A/C5aR-A or vehicle and then i.v. injected. Peri-transplant (2 hours after transplantation) PKH26-MSCs were administered to an additional group of BL6 recipients (MSCs day0, n=3). Naive BL6 mice (n=3) given only the PKH26+ MSC infusion and BL6 transplanted mice left untreated (n=3) or given C3aR-A and C5aRA (n=4) but no MSCs were used as controls. All mice were euthanized 24 hours after cell infusion (or 3 days after transplant for mice not given MSC infusion). Additional groups of animals with the same dose and timing of MSC infusion, as well as the same combination with individual C3a and C5a receptor antagonists, were considered to assess the impact of anaphylatoxin receptor blockade on kidney graft survival (n=7-8 mice per group) and on T cell alloreactivity and Treg generation (n=4 mice in each group sacrificed 4 days after transplantation).

C3aR antagonist is a non-peptide antagonist of C3aR that competitively blocks C3a binding with an IC50 value of 200 nM.37 C5aR antagonist is a macrocyclic hexapeptidomimetic compound that acts as a non-competitive antagonist of complement C5a receptor.38

Statistical analyses

Survival data were compared using the log-rank test. All other data were analysed by ANOVA. Differences with a P value <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Mouse MSCs expressC3a and C5a receptors

MSCs derived from BL6 bone marrow and depleted of CD11b+/CD45+ cells were analysed for the expression of C3aR and C5aR at the gene and protein level. C3aR and C5aR mRNA levels were 200-fold (mean ± SD arbitrary units: 203±127) and 4-fold higher (mean ± SD arbitrary units: 3.5±1.7), respectively, in MSCs compared to splenocytes from naïve BL6 mice (arbitrary units as 2−ΔΔCt versus BL6 spleen cells taken as calibrator=1). More than 90% of MSCs expressed C3aR and 80% expressed C5aR on their surface (Figure 1A-B).

Figure 1. C3aR and C5aR expression on MSCs.

Representative overlay histograms of flow cytometric analysis of C3aR and C5aR expression on BL6 bone marrow–derived MSCs (A). Mean percentages of positive MSC are reported in the figure (B). Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) over isotype (after subtracting MFI of isotype antibody) for C3aR and C5aR expression on MSC. (Data are mean ± SD of n = 4 MSC preparations.)

Inhibition of C3aR or C5aR prevents the increased intragraft recruitment of MSC infused posttransplant

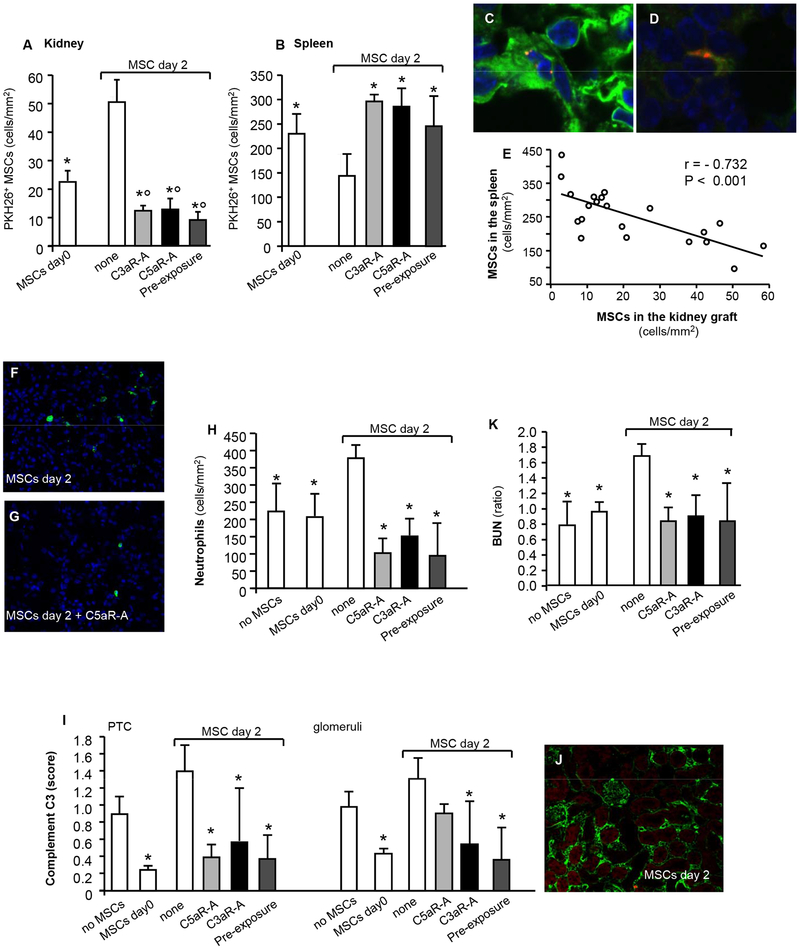

When infused into naïve non-transplanted mice, MSC preferentially homed into the spleen, while administration on day +2 after kidney transplant results into a significant recruitment of cells into the graft (Figure 2A-B). PKH26 positivity was detected either as cell fragments or as whole cells (Figure 2C-D). When cells were infused on the day of transplantation, the numbers of MSCs in the kidney grafts was lower, whilst the numbers in the spleen were higher compared to animals given MSCs 2 days posttransplant (Figure 2A-B).

Figure 2. MSCs homing to the kidneys and spleen of recipient mice and impact on early graft function and inflammation.

Number (mean ± SD) of PKH26+ MSCs in kidney grafts (A) and spleens (B) from mice given MSCs the day of transplantation (2 hrs after surgery) or MSCs 2 days after transplantation in combination with either C3aR-A or C5aR-A or preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A and euthanized 24 hrs after cell infusion, (n = 3 mice per group). Representative images of a PKH26+ MSC in the kidney (C) and in the spleen (D), original magnification 600X. Linear regression analysis of MSC numbers in the kidney grafts (cells/mm2) versus the MSCs in the spleen (cells/mm2) from the above mice and including naïve untransplanted mice (n = 3) given MSCs (MSCs in the kidney: 3.6 ± 1.4 cells/mm2; MSCs in the spleen 375 ± 58 cells/mm2) or mice given MSC preexposed to vehicle for C3aR-A and C5aR-A (see Figure S2) (E). Representative immunohistochemistry images of neutrophils (F–G) and complement C3 (J) staining in kidney graft tissues from mice given MSCs alone on day 2 (F–J) or together with C5aR-A (G) (original magnification 400X). Number of graft infiltrating neutrophils (cells/mm2) (H), intragraft complement C3b deposition in kidney allografts (semiquantitative scores on peritubular capillaries and glomeruli) (I) and kidney graft function (as ratio between BUN levels 24 hrs after versus before MSC infusion) (K) from mice given peri-transplant MSCs or given MSCs 2 days after transplantation in combination with either C3aR-A or C5aR-A or preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A. Data are mean ± SD; *P < 0.05 versus MSC day 2; °P < 0.05 versus MSC day 0. BUN: blood urea nitrogen, PTC: peritubular capillaries.

To evaluate the effect of C3aR or C5aR on intragraft recruitment of MSC infused on day 2 posttransplant, sensitized recipient mice were administered a short-course of C3aR-A or C5aR-A at the time of MSC infusion or administered MSC preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A. Both C3aR-A and C5aR-A significantly – and to a similar extent – reduced intragraft recruitment of MSCs and increased homing into the spleen on MSCs infused on day 2 after transplant compared to mice given posttransplant MSCs alone (Figure 2A-B). Similarly, a low number of MSC preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A migrated into the graft and they preferentially localized into the spleen when administered on day +2 (Figure 2A-B). Considering the data collectively, the number of MSCs localizing in the spleen inversely correlated with cell numbers in the grafts (Figure 2E).

These findings indicate that the administration of MSCs either on the day of transplantation or 2 days posttransplantation after preexposure to or together with C3aR-A or C5aR-A prevents intragraft recruitment of MSCs, and instead orients them to home to the spleen.

Inhibition of MSC graft recruitment is associated with reduced graft inflammation

We then evaluated whether limiting MSC recruitment to the graft prevented MSC-induced neutrophil infiltration and complement deposition.

Immunohistochemistry showed that kidney grafts harvested 24 hours after MSC infusion from mice given MSCs at day +2 had significant neutrophils infiltrates (Figure 2F-H) and complement C3b deposition, especially in the peritubular capillaries (Figure 2I-J) compared to mice not given MSCs. MSC administration on day 0 significantly reduced both neutrophil infiltration and complement deposition (Figure 2F-J).

The number of intragraft neutrophils (Figure 2F-H) and the score of complement C3 deposits (Figure 2I-J) in kidney grafts from mice given MSCs at day 2 combined with or preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A were comparable to those of mice given MSCs on the day of transplant and significantly reduced compared to the day2 group (Figure 2F-J). Accordingly, mice given MSCs posttransplant preexposed to or combined with C3aR-A or C5aR-A did not develop acute graft dysfunction, similar to MSC injection at day 0, and in contrast to mice injected with MSCs posttransplant without antagonists (Figure 2K).

Together these findings indicate that decreased intragraft MSC localization is associated with decreased graft inflammation and preserved renal allograft function.

Kidney graft survival

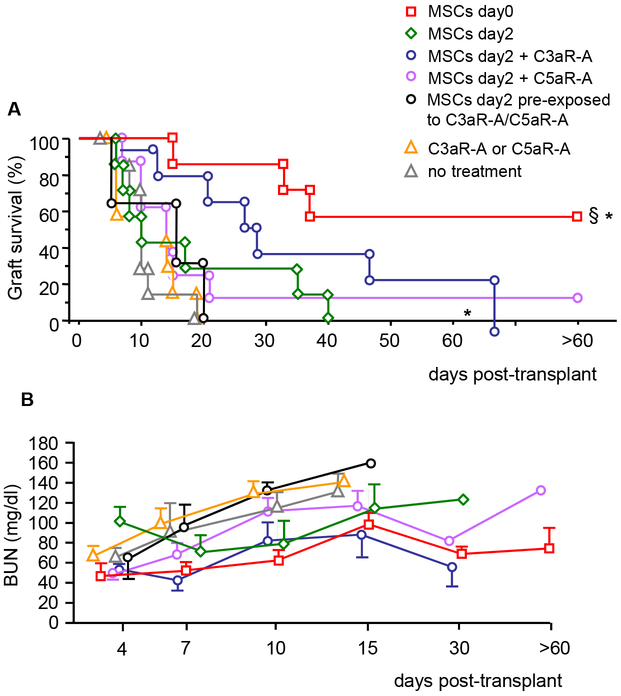

We next assessed whether preferential homing into the spleen of MSCs administered on day 0 or on day +2 in combination with C3aR and C5aR antagonists was associated with prolongation of graft survival.

Untreated BL6 kidney transplant recipients rejected BALB/c allografts by day 20 posttransplant and MSCs infusion on day +2 posttransplant did not prolong graft survival significantly. In contrast, MSCs given on the day of transplantation significantly prolonged graft survival, similarly to our previously published data with pretransplant (day −1) MSCs infusion (Figure S1). More than half of the recipient mice showed indefinite graft survival (>60 days) with mildly impaired kidney graft function (Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3. Kidney allograft survival in mice given MSC infusion alone or combined with C3aR and C5aR antagonists.

BALB/c kidney allograft survival (A) and function (B, as BUN levels) in BL6 mice given syngeneic BM-MSC infusion (5 × 105; i.v.) on the day of transplantation (MSCs day 0, n = 7) or 2 days posttransplant either alone (MSCs day2, n = 7) or combined with C3aR-A (3 injections of 15 mg/kg; MSCs day2 + C3aR-A, n = 7) or C5aR-A (3 injections of 0.5 mg/kg; MSCs day2 + C5aR-A, n = 8) or given MSC preexposed in vitro to C3aR-A/C5aR-A (n = 3). Mice left untreated (no treatment, n = 7) or given only C3aR-A and C5aR-A treatment (C3aR-A or C5aR-A, n = 6) were considered as control groups. *P < 0.05 versus C3aR-A or C5aR-A alone control group, §P < 0.05 versus MSCs day 2.

BL6 mice given C3aR-A or C5aR-A treatment alone invariably rejected the kidney allograft within 20 days from transplantation (C3aR-A: 6, 8, 10 days; C5aR-A: 10, 10, 11, 19 days) (Figure 3A) with progressively deteriorating kidney graft function (Figure 3B) and were then considered as a single control group. Posttransplant administration of MSCs with C3aR-A or C5aR-A resulted in slight prolongation of graft survival that was significantly prolonged in the C3AR-A group compared to untreated controls or to mice receiving complement receptor antagonists alone. (Figure 3A). Mice given posttransplant MSC preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A rejected their graft within 20 days posttransplant (Figure 3A-B). Only recipient mice given MSC the day of transplant achieved long-term graft acceptance (Figure 3A). Histological analysis of kidney graft from long-term surviving mice (n=3, graft survival >60 days) showed histological picture of moderate chronic allograft injury (data not shown).

These studies indicate that MSCs given posttransplant were remarkably less potent in inducing indefinite graft survival compared to MSCs given on the day of transplantation.

Anti-donor T cell alloreactivity and Treg expansion in MSC infused mice

In order to investigate the mechanisms underlying the failure of posttransplant MSC infusion combined with anaphylatoxin receptor antagonism to prolong graft survival despite their homing to the secondary lymphoid organ, we studied ex vivo anti-donor T cell alloreactivity as well as Treg numbers from sensitized mice sacrificed 4 days after transplantation.

Administration of MSCs on day 0 resulted in a significantly reduced frequency of IFNγ-producing cells in response to donor BALB/c alloantigens compared to mice not given MSC or given the receptor antagonists alone (Figure 4A). The frequency of anti-donor IFNγ-producing cells in mice given posttransplant MSCs alone or combined with the short course of C3aR-A and C5aR-A administration was significantly reduced compared to control mice, as well (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Ex vivo antidonor alloreactivity, Treg expansion, and suppressive function in MSC-infused mice.

Frequency of BALB/c reactive IFNγ-producing splenocytes (A), percentage of CD25+Foxp3+ cells among splenic CD4+ T cells (B), percentage of Helios negative Tregs (D), and ratios between Treg and CD44highCD62L− effector memory (TEM) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (F) from BL6 mice given syngeneic BM-derived MSCs after the day of transplantation (MSCs day 0) or from BL6 recipients given MSCs 2 days posttransplant either alone (MSCs day 2, none) or with C3aR-A or C5aR-A treatment. All mice were transplanted with a BALB/c kidney allograft at day 0 and were sacrificed 4 days after transplant. Transplanted mice not given an MSC infusion (no MSCs) or given C3aRA and C5aRA (MSC + RAs) and sacrificed 4 days posttransplant or naïve untransplanted BL6 mice (n = 6) were considered controls. (C) Representative dot plots of Foxp3+CD25+ on CD4+ T cells and representative histograms of Helios expression by Tregs (E) from kidney transplant mice given MSCs at day 0 or MSC at day 2 in combination with C3aR-A, respectively. (G) Frequency of IFNγ-producing CD4+CD25− T cells isolated from naïve untransplanted BL6 mice alone (first white column on the left) or in the presence of CD4+CD25+ T cells (at ratios of 2:10 CD4+CD25+ T cells:CD4+CD25− T cells) isolated from mice given syngeneic BM-derived MSCs the day of transplantation (MSCs day 0) or from BL6 recipients given MSCs 2 days posttransplant, either alone (MSCs day 2, none) or with C3aR-A or C5aR-A treatment and euthanized 4 days after transplant and from mice of control groups. Percentages in spot images in panel A represent the area covered by spots. Data are mean ± SD; §P < 0.05 versus CD4+CD25− T cells alone, °P < 0.05 compared with all the other groups, *P < 0.05 versus MSCs day 0.

MSC infusion on the day of transplantation was associated with a marked increase in the percentage of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Tregs, which was significantly higher than in mice receiving the cells posttransplant with or without C3aR-A/C5aR-A or in those not given MSCs or in naive mice (Figure 4B-C). More than 80% of Tregs expanded in mice given MSC at day 0 did not express Helios, a percentage significantly higher than that of Tregs found in the other experimental groups (Figure 4D-F). Accordingly, the ratios between Tregs and CD44highCD62L− effector memory CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in mice given MSCs on the day of transplantation compared to those from mice given MSCs posttransplant, with or without C3aR-A or C5aR-A (Figure 4G). The increase in Treg levels and in the ratio Tregs/CD8+TEM in mice given MSC at day 0 compared to other groups were confirmed also when considering total counts of Tregs and TEM cells (Figure S3). When assayed in their capability to suppress, Treg obtained from naive mice or from mice not given MSCs, or given MSCs on the day of transplant or after transplant +/− complement receptor antagonists similarly inhibited IFNγ spot production by CD4+CD25− effector T cells (Figure 4H).

These findings indicate that MSCs reduce anti-donor T cell alloreactivity when given either posttransplant or on the day of the transplant, but Treg induction occurs only when cells are given at day 0, suggesting that MSCs are less potent in promoting immunoregulation when alloimmune T cell response has started. We excluded that timing of MSC exposure to alloimmune environment (4-day exposure in mice given MSC at day 0 and 2-day exposure in mice that received MSC on day 2) accounted for difference in the Treg levels since, in-vitro, MSC added to a MLR culture (CD4+T cells form BL6 mice as responders against BALB/c splenocytes as stimulators) at day 2 (1:10 MSC: CD4+ T cells) and left for the 72 hours failed to induce Tregs at the same extent as MSC added at day 0 and left for the same time (data not shown). In addition, we previously demonstrated10 that 1-2 days was a time long enough for MSC to induce Treg expansion into naïve mice. Indeed, splenocytes from MSC-infused naïve mice killed 1-2 days after MSC infusion were able to induce tolerance toward a kidney allograft when transferred into BL6 mice the day before Balb/c kidney transplantation10.

Discussion

The unique immunomodulatory properties of MSCs make them one of the most promising tolerance-promoting cell therapies in solid organ transplantation. The current evidence indicates that, when given before transplantation, autologous BM-derived MSCs are safe, promote donor-specific immunomodulation in living-donor kidney transplant recipients,21,22,39 and induce long-term kidney allograft acceptance in mice.18 However, when given after transplantation MSCs are recruited into the graft, where they promote graft inflammation.18,21 Intragraft recruitment of MSCs given posttransplantation prevents their localization in the spleen and fails to induce Treg expansion in mice.18 Ischemia-reperfusion injury is a potent stimulus for the production and activation of complement components that leads to the generation of C3a and C5a.40-42 Herein, we hypothesized that these chemotaxins play a major role in the recruitment of MSCs into the graft. With the final goal of extending MSC therapy to kidney transplant recipients of deceased donor kidneys, we tested here the efficacy or peri-transplant MSC infusion or that of posttransplant infusion in combination with C3aR-A and C5aR-A administration in a murine model of allogeneic kidney transplantation, as a strategy to prevent MSC migration to the graft and to relocate them to lymphoid organs. To exclude any possible effect of the short course of complement receptor antagonists on graft inflammation we also pretreated MSC with C3aR-A and C5aR-A before infusion. Our data show that posttransplant MSC infusion combined with or preexposed to C3aR-A or C5aR-A: a) prevented MSC recruitment within the kidney graft and reduce MSC-induced inflammation; b) effectively re-located MSCs to the spleen with significant inhibition of alloreactive T cells; c) at variance with MSC injection on day 0, it did not increase Tregs to any appreciable extent, which translated into a modest prolongation of kidney allograft survival. In contrast, MSCs given on the day of transplant localized in the spleen, inhibited T cell alloresponse and induced Tregs, and eventually promoted indefinite graft acceptance. These data provide a strong rationale for clinical studies testing the safety/efficacy profile of MSC administration on the transplant day in recipients of organs from deceased organs.

After intravenous injection, MSCs engraft predominantly in the lungs,43 whereas less than one percent of them move to other organs, such as the liver and spleen within 24 to 48 hours postinfusion.38 These organs have a microvasculature that permits non-specific entrapment and sequestration of cells. However, in the presence of injury, systemically infused MSCs have a propensity to migrate into damaged tissues, as documented in the ischemic brain44 or kidney,45,46 infarcted myocardium,47 and injured liver.48

Amongst other molecules,46,49,50 bioactive peptides such as C3a and C5a, generated by the activation of the complement cascade, have been implicated in the migration of MSCs toward sites of tissue injury. Human MSCs express functional receptors for C3a and C5a and both anaphylatoxins cause a potent chemotactic MSC response in-vitro.32,33 Here we found that, like human MSCs,32 murine MSCs express both C3aR and C5aR.

The short-term administration of C3aR-A or C5aR-A posttransplant, together with MSCs, as well as the administration of MSC preexposed to C3aR-A and C5aR-A reduced the number of MSCs localized in the kidney allografts, even though cell recruitment was not completely abolished, supporting the hypothesis that different factors orchestrate MSC homing to the injured graft.

The reduction of intragraft MSC recruitment through C3aR or C5aR antagonism decreased graft inflammation and prevented early renal graft dysfunction, further confirming that MSCs localizing in the injured allograft acquire a pro-inflammatory phenotype.18 Findings that posttransplant injection of MSCs preexposed to complement receptor antagonists was associated with reduced graft inflammation comparably to mice given C3aR-A and C5aR-A administration exclude any possible anti-inflammatory effect of systemic complement receptor antagonists.

Preventing intragraft recruitment of MSCs by C3aR-A or C5aR-A treatment resulted in their relocation to the spleen. Data by others show that MSC homing to secondary lymphoid organs is important for their immunomodulatory effects in experimental models of GVHD,51 enterocolitis52 and ischemic acute kidney injury.53 However, our results indicate that, in a kidney transplant model, the re-direction into the spleen of MSCs injected posttransplant through pharmacological inhibition of C3aR or C5aR, failed to promote Tregs and to prolong graft survival. In contrast, long-term graft acceptance can be achieved by administering MSCs on the day of transplantation.

Since our recipient mice were sensitized toward the donor antigen prior to transplantation and this led to the expansion of donor-reactive T cells, we first tested the hypothesis that donor-sensitized T cells re-stimulated by the kidney graft alloantigens are less amenable to MSC-induced immunosuppression. Our ex vivo data show that MSCs reduced T cell alloreactivity in sensitized mice both when given at day 0 or day 2 after transplantation, consistent with previous studies demonstrating that MSC inhibit memory T-cell reactivation.54,55 Despite being capable of reducing T-cell alloreactivity, MSCs given posttransplant failed to induce Foxp3+ Treg, while MSCs given on the day of transplantation induced a significant increase in Helios-negative56 Treg frequency, as well as in the ratio between Tregs/effector memory CD8+ T cells.

Our in vivo data are in line with the in vitro findings by Carrion et al who showed that MSCs suppress the proliferation, activation and differentiation of TH1 and TH17 cells and increase the percentage of Treg when added at the start of the polarization process.57 However, when added to mature and already differentiated TH1 and TH17 cells, MSCs still suppressed their proliferation but did not promote their conversion into Tregs.57 Collectively, these data suggest the idea that alloreactive Teff cells are resistant to Treg polarization by MSCs.

The main factors that have been identified as crucial for the induction of Foxp3 expression during naïve T-cell activation are TGFβ and IL-2.58 Experiments utilizing IL-2 neutralization and IL-2-deficient T cells demonstrated that IL-2 is required in vitro for the TGFβ- mediated induction of Foxp3 transcriptional activity.59 Since Foxp3 Tregs do not produce IL-2, Teff cells generating this cytokine in an antigen-dependent fashion are necessary for Treg survival.60,61 However, Teff cells progressively lose the capacity to produce IL-2 upon full effector differentiation.62,63 This raised the possibility that, under certain conditions such as infection64,65, unrestrained differentiation of Teff results in the withdrawal of IL-2 support for Tregs.66

MSCs constitutively produce TGFβ67, but not IL-2, so it could be possible to speculate that during T cell activation in the presence of MSCs they mediate CD4+ T cell polarization toward a regulatory phenotype in synergy with IL-2 released by effector CD4+ T cells at an intermediate state of activation. At a later stage, MSCs still retain the capability to suppress proliferation of fully differentiated Teff cells, but lose Treg generating properties due to lower IL-2 availability.

Our study has some limitation. We cannot exclude that the cells mainly responsible for Treg generation following MSC infusion are recipient phagocytes which, by being engulfed with apoptotic MSC, are reprogrammed into anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory cells, a mechanism proposed recently by several studies.68-71 Future studies will assess whether timing of MSC infusion may influence this mechanism, as well.

We did not formally evaluate the pathway of complement activation that leads to the production of C3a and C5a, but previous studies showed that all the three pathways (classical, alternative, and MBL) are active after ischemia/reperfusion in the graft.44 Finally, although unlikely, it is possible that homing of MSCs to lymph nodes versus the spleen differently affects their capability to induce Treg, a hypothesis that has not been carefully tested by our studies.

To summarize, both the present data and previously published results32,33 indicate that complement C3a and C5a are crucial mediators of MSC recruitment into the graft, and antagonizing their receptors allows MSCs to home to the secondary lymphoid organs. However, even with C3aR-A or C5aR-A treatment, posttransplant administration of MSCs critically impairs their capability to promote Treg development. For the full realization of tolerance-generating potential, MSC infusion in solid organ transplant recipients must be performed before or on the day of transplantation. Peri-transplant infusion would be applicable to deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Given that third-party MSC share the capability of autologous cells to generate Treg and prolong graft survival19,66-69 off-the-shelf third-party MSC can represent the ideal cell therapy in transplantation in terms of availability, standardization, quality control and cost reduction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study has been partially supported by grants from Fondazione ART per la Ricerca sui Trapianti (Milan, Italy). PC is supported by NIH grant R01 AI132949 and by the GOFARR Fundand.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BM

Bone marrow

- C3aR

C3a receptor

- C3aR-A

C3aR antagonist

- C5aR

C5a receptor

- C5aR-A

C5aR antagonist

- GVHD

Graft-versus-host Disease

- IFNγ

Interferon gamma

- MSC

Mesenchymal stromal cells

- T-eff

Effector T cells

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor-beta

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(5):383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: a novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(12):1445–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemeth K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15(1):42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiyama K, Chen C, Wang D, et al. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-induced immunoregulation involves FAS-ligand-/FAS-mediated T cell apoptosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(5):544–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107(4):1484–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24(1):74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.English K, Barry FP, Mahon BP. Murine mesenchymal stem cells suppress dendritic cell migration, maturation and antigen presentation. Immunol Lett. 2008;115(1):50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang B, Liu R, Shi D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells induce mature dendritic cells into a novel Jagged-2-dependent regulatory dendritic cell population. Blood. 2009;113(1):46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddad R, Saldanha-Araujo F. Mechanisms of T-cell immunosuppression by mesenchymal stromal cells: what do we know so far? Biomed Res Int. 2014:216806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casiraghi F, Azzollini N, Cassis P, et al. Pretransplant infusion of mesenchymal stem cells prolongs the survival of a semiallogeneic heart transplant through the generation of regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):3933–3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge W, Jiang J, Baroja ML, et al. Infusion of mesenchymal stem cells and rapamycin synergize to attenuate alloimmune responses and promote cardiac allograft tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(8):1760–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eggenhofer E, Renner P, Soeder Y, et al. Features of synergism between mesenchymal stem cells and immunosuppressive drugs in a murine heart transplantation model. Transpl Immunol. 2011;25(2–3):141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Zhang A, Ye Z, Xie H, Zheng S. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit acute rejection of rat liver allografts in association with regulatory T-cell expansion. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(10):4352–4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding Y, Xu D, Feng G, Bushell A, Muschel RJ, Wood KJ. Mesenchymal stem cells prevent the rejection of fully allogenic islet grafts by the immunosuppressive activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9. Diabetes. 2009;58(8):1797–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YH, Wee YM, Choi MY, Lim DG, Kim SC, Han DJ. Interleukin (IL)-10 induced by CD11b(+) cells and IL-10-activated regulatory T cells play a role in immune modulation of mesenchymal stem cells in rat islet allografts. Mol Med. 2011;17(7–8):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu DM, Yu XF, Zhang D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells differentially mediate regulatory T cells and conventional effector T cells to protect fully allogeneic islet grafts in mice. Diabetologia. 2012;55(4):1091–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge W, Jiang J, Arp J, Liu W, Garcia B, Wang H. Regulatory T-cell generation and kidney allograft tolerance induced by mesenchymal stem cells associated with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression. Transplantation. 2010;90(12):1312–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casiraghi F, Azzollini N, Todeschini M, et al. Localization of mesenchymal stromal cells dictates their immune or proinflammatory effects in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(9):2373–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Y, Zhou S, Liu H, et al. Indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxgenase Transfected Mesenchymal Stem Cells Induce Kidney Allograft Tolerance by Increasing the Production and Function of Regulatory T Cells. Transplantation. 2015;99(9):1829–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plock JA, Schnider JT, Schweizer R, et al. The Influence of Timing and Frequency of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy on Immunomodulation Outcomes After Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101(1):e1–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perico N, Casiraghi F, Introna M, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney transplantation: a pilot study of safety and clinical feasibility. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(2):412–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perico N, Casiraghi F, Gotti E, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney transplantation: pretransplant infusion protects from graft dysfunction while fostering immunoregulation. Transpl Int. 2013;26(9):867–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casiraghi F, Perico N, Cortinovis M, Remuzzi G. Mesenchymal stromal cells in renal transplantation: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(4):241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan J, Wu W, Xu X, et al. Induction therapy with autologous mesenchymal stem cells in living-related kidney transplants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1169–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng Y, Ke M, Xu L, et al. Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with low-dose tacrolimus prevent acute rejection after renal transplantation: a clinical pilot study. Transplantation. 2013;95(1):161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinders MEJ, van Kooten C, Rabelink TJ, de Fijter JW. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy for Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation. 2018;102(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Chen X, Cao W, Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(11):1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(2):141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(4):392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farris AB, Taheri D, Kawai T, et al. Acute renal endothelial injury during marrow recovery in a cohort of combined kidney and bone marrow allografts. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(7): 1464–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU. Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: a critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(3):450–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schraufstatter IU, Discipio RG, Zhao M, Khaldoyanidi SK. C3a and C5a are chemotactic factors for human mesenchymal stem cells, which cause prolonged ERK1/2 phosphorylation. J Immunol. 2009;182(6):3827–3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hengartner NE, Fiedler J, Schrezenmeier H, Huber-Lang M, Brenner RE. Crucial role of IL1beta and C3a in the in vitro-response of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to inflammatory mediators of polytrauma. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0116772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Zhu L, Quan D, et al. Pattern of liver, kidney, heart, and intestine allograft rejection in different mouse strain combinations. Transplantation. 1996;62(9):1267–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cravedi P, Leventhal J, Lakhani P, Ward SC, Donovan MJ, Heeger PS. Immune cell-derived C3a and C5a costimulate human T cell alloimmunity. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(10):2530–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Locatelli M, Buelli S, Pezzotta A, et al. Shiga toxin promotes podocyte injury in experimental hemolytic uremic syndrome via activation of the alternative pathway of complement. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(8):1786–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ames RS, Lee D, Foley JJ, et al. Identification of a Selective Nonpeptide Antagonist of the Anaphylatoxin C3a Receptor That Demonstrates Antiinflammatory Activity in Animal Models. J Immunol. 2001;166(10):6341–6348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lillegard KE, Loeks-Johnson AC, Opacich JW, et al. Differential Effects of Complement Activation Products C3a and C5a on Cardiovascular Function in Hypertensive Pregnant Rats J Pharm Exper Ther. 2014;351(2):344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinders ME, de Fijter JW, Roelofs H, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of allograft rejection after renal transplantation: results of a phase I study. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(2):107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nauser CL, Farrar CA, Sacks SH. Complement Recognition Pathways in Renal Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(9):2571–2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delpech PO, Thuillier R, SaintYves T, et al. Inhibition of complement improves graft outcome in a pig model of kidney autotransplantation. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cravedi P, Heeger PS. Complement as a multifaceted modulator of kidney transplant injury. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2348–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang SK, Shin IS, Ko MS, Jo JY, Ra JC. Journey of mesenchymal stem cells for homing: strategies to enhance efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:342968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Deng Y, Zhou GQ. SDF-1alpha/CXCR4-mediated migration of systemically transplanted bone marrow stromal cells towards ischemic brain lesion in a rat model. Brain Res. 2008;1195:104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wise AF, Ricardo SD. Mesenchymal stem cells in kidney inflammation and repair. Nephrology (Carlton). 2012;17(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrera MB, Bussolati B, Bruno S, et al. Exogenous mesenchymal stem cells localize to the kidney by means of CD44 following acute tubular injury. Kidney Int. 2007;72:430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong F, Harvey J, Finan A, Weber K, Agarwal U, Penn MS. Myocardial CXCR4 expression is required for mesenchymal stem cell mediated repair following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126(3):314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Q, Zhou X, Shi Y, et al. In vivo tracking and comparison of the therapeutic effects of MSCs and HSCs for liver injury. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao Z, Zhang G, Wang F, et al. Protective effects of mesenchymal stem cells with CXCR4 up-regulation in a rat renal transplantation model. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gheisari Y, Azadmanesh K, Ahmadbeigi N, et al. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells to overexpress CXCR4 and CXCR7 does not improve the homing and therapeutic potentials of these cells in experimental acute kidney injury. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(16):2969–2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, Jiang Y, Jiang X, et al. CCR7 guides migration of mesenchymal stem cell to secondary lymphoid organs: a novel approach to separate GvHD from GvL effect. Stem Cells. 2014;32(7):1890–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parekkadan B, Upadhyay R, Dunham J, et al. Bone marrow stromal cell transplants prevent experimental enterocolitis and require host CD11b+ splenocytes. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):966–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu J, Zhang L, Wang N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate ischemic acute kidney injury by inducing regulatory T cells through splenocyte interactions. Kidney Int. 2013;84(3):521–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101(9):3722–3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karlsson H, Samarasinghe S, Ball LM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells exert differential effects on alloantigen and virus-specific T-cell responses. Blood. 2008;112(3):532–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3433–3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carrion F, Nova E, Luz P, Apablaza F, Figueroa F. Opposing effect of mesenchymal stem cells on Th1 and Th17 cell polarization according to the state of CD4+ T cell activation. Immunol Lett. 2011;135(1–2):10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Natural and adaptive foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity. 2009;30(5):626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng Y, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 in control of the regulatory T cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(5):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(11):1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bayer AL, Yu A, Adeegbe D, Malek TR. Essential role for interleukin-2 for CD4(+)CD25(+) T regulatory cell development during the neonatal period. J Exp Med. 2005;201(5):769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amado IF, Berges J, Luther RJ, et al. IL-2 coordinates IL-2-producing and regulatory T cell interplay. J Exp Med. 2013;210(12):2707–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(4):247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oldenhove G, Bouladoux N, Wohlfert EA, et al. Decrease of Foxp3+ Treg cell number and acquisition of effector cell phenotype during lethal infection. Immunity. 2009;31(5):772–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benson A, Murray S, Divakar P, et al. Microbial infection-induced expansion of effector T cells overcomes the suppressive effects of regulatory T cells via an IL-2 deprivation mechanism. J Immunol. 2012;188(2):800–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liston A, Gray DH. Homeostatic control of regulatory T cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.English K, Ryan JM, Tobin L, Murphy MJ, Barry FP, Mahon BP. Cell contact, prostaglandin E(2) and transforming growth factor beta 1 play non-redundant roles in human mesenchymal stem cell induction of CD4+CD25(High) forkhead box P3+ regulatory T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156(1):149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonçalves F da C, Luk F, Korevaar SS, et al. Membrane particles generated from mesenchymal stromal cells modulate immune responses by selective targeting of proinflammatory monocytes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Melief SM, Schrama E, Brugman MH, et al. Multipotent stromal cells induce human regulatory T cells through a novel pathway involving skewing of monocytes toward anti-inflammatory macrophages. Stem Cells. 2013;31(9):1980–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Witte SFH, Luk F, Sierra Parraga JM, Gargesha M, Merino A, Korevaar SS, Shankar AS, O’Flynn L, Elliman SJ, Roy D, et al. Immunomodulation By Therapeutic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSC) Is Triggered Through Phagocytosis of MSC By Monocytic Cells. Stem Cells. 2018;36(4):602–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galleu A, Riffo-Vasquez Y, Trento C, et al. Apoptosis in mesenchymal stromal cells induces in vivo recipient-mediated immunomodulation. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(416). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuo YR, Chen CC, Goto S, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a swine hemi-facial allotransplantation model. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y, Zhang A, Ye Z, Xie H, Zheng S. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit acute rejection of rat liver allografts in association with regulatory T-cell expansion. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(10):4352–4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuo YR, Goto S, Shih HS, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells prolong composite tissue allotransplant survival in a swine model. Transplantation. 2009;87(12):1769–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuo YR, Chen CC, Shih HS, et al. Prolongation of composite tissue allotransplant survival by treatment with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells is correlated with T-cell regulation in a swine hind-limb model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.