Significance Statement

Most patients with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), the leading cause of pediatric ESKD, do not have mutations in any of the approximately 40 CAKUT-causing genes that have been identified to date. The authors studied a family with two siblings with CAKUT that appeared to be caused by an autosomal recessive mutation in an as-yet unidentified gene. Using whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing, they found that the affected children but not healthy family members had a homozygous deletion in the Cobalamin Synthetase W Domain–Containing Protein 1 (CBWD1) gene. They also demonstrated in mice that Cbwd1 protein was expressed in the ureteric bud cells, and that Cbwd1-deficient mice showed CAKUT. These findings suggest a role for CBWD1 in CAKUT etiology.

Keywords: CBWD1, CAKUT, kidney development, ureteric bud

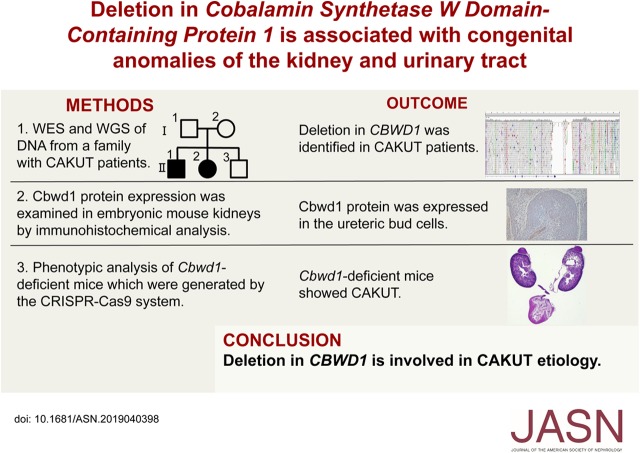

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Researchers have identified about 40 genes with mutations that result in the most common cause of CKD in children, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), but approximately 85% of patients with CAKUT lack mutations in these genes. The anomalies that comprise CAKUT are clinically heterogenous, and thought to be caused by disturbances at different points in kidney development. However, identification of novel CAKUT-causing genes remains difficult because of their variable expressivity, incomplete penetrance, and heterogeneity.

Methods

We investigated two generations of a family that included two siblings with CAKUT. Although the parents and another child were healthy, the two affected siblings presented the same manifestations, unilateral renal agenesis and contralateral renal hypoplasia. To search for a novel causative gene of CAKUT, we performed whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing of DNA from the family members. We also generated two lines of genetically modified mice with a gene deletion present only in the affected siblings, and performed immunohistochemical and phenotypic analyses of these mice.

Results

We found that the affected siblings, but not healthy family members, had a homozygous deletion in the Cobalamin Synthetase W Domain–Containing Protein 1 (CBWD1) gene. Whole-genome sequencing uncovered genomic breakpoints, which involved exon 1 of CBWD1, harboring the initiating codon. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed high expression of Cbwd1 in the nuclei of the ureteric bud cells in the developing kidneys. Cbwd1-deficient mice showed CAKUT phenotypes, including hydronephrosis, hydroureters, and duplicated ureters.

Conclusions

The identification of a deletion in CBWD1 gene in two siblings with CAKUT implies a role for CBWD1 in the etiology of some cases of CAKUT.

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) are the most common cause of ESKD in children.1–4 CAKUT are clinically heterogeneous. These disorders encompass a large variety of anatomic malformations that range from abnormal phenotypes of the renal parenchyma, such as renal agenesis and renal hypoplasia, to those of the collecting system, such as vesicoureteral reflux and duplicated ureter.5 The diverse manifestations of CAKUT are thought to be caused by disturbances at different points in kidney development.6,7

The kidney develops through a multistage process. After budding from the nephric duct, the ureteric bud cells invade the metanephric mesenchyme cells, followed by reciprocally inductive interactions between these two precursors.5 Metanephric mesenchyme differentiates into nephrons (glomerular, proximal tubular, and distal tubular epithelium), and further branching of the ureteric bud forms the kidney collecting system (collecting tubular and ureter epithelium). Our understanding of the mechanisms involved in nephrogenesis is mostly derived from mouse models.8,9

The pathogenesis of CAKUT is multifactorial. Genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors are known to be involved in its development. Several lines of evidence indicate that CAKUT can also be caused by mutations in single genes. The mutation is familial (autosomal dominant or recessive) or de novo. Approximately 40 genes causative of human CAKUT have been identified.5,10,11 However, approximately 85% of patients with CAKUT do not possess mutations in any of them.12,13 Therefore, it is likely that there are additional as-yet unidentified genes causative of CAKUT.

Despite the great advances of next-generation sequencing technology, identification of novel CAKUT-causing genes remains difficult because of their variable expressivity, incomplete penetrance, and heterogeneity.14,15 Therefore, it remains a challenge to identify new components of the pathogenesis of human CAKUT.

Here, we investigated two generations of a family, including two siblings with CAKUT, which resulted in identification of a homozygous deletion in Cobalamin Synthetase W Domain–Containing Protein 1 (CBWD1) only in the family members with CAKUT. We showed that Cbwd1 was localized in the ureteric bud. We also constructed Cbwd1-deficient mice showing anomalies of the urinary collecting system. Collectively, our results indicate a role for CBWD1 in CAKUT etiology.

Methods

This study was approved by the Central Ethics Board of Tokyo Women’s Medical University. All family members provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the institutional committees of the University of Tokyo (approval number P16–009) and were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA collected from family members was used for whole-exome sequencing (WES). DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A fragment library was constructed from the extracted DNA using the AB Library Builder System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Constructed libraries were subjected to whole-exome enrichment using a TargetSeq Target Enrichment Kit (Life Technologies). The prepared exome libraries were sequenced using the massively parallel deep sequencer 5500xl SOLiD System (Life Technologies) by the paired-end sequencing method. Data were analyzed using LifeScope software (Life Technologies) with mapping on the Human Genome Reference, GRCh37/hg19 (The Genome Reference Consortium; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genome/assembly/grc/index.shtml). All procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions. Obtained data were annotated and stringently filtered to exclude false variation calls using our previously described programs developed in house.16 Summary of sequence data are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Validating PCR for CBWD1 Deletion

Validating PCR reactions were performed using KOD FX Neo in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (TOYOBO Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All amplifications were performed for 40 cycles using 100 ng of genomic DNA with the indicated primers and annealing temperature as follows: paired primers of Chr9_177574_F, 5′-TGTAGTAGAAGCCAAAAGAACAGC-3′, and Chr9_179736_R, 5′-GCTTTTACGTTAGGAATGAC-3′, at 60°C; Chr9_163253_F, 5′-GTGTTCAGGTAAATAAAGTAAGAC-3′, and Chr9_164850_R, 5′-AGGTGGACAGCTTTAGACGC-3′, at 60°C.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization

Extracted genomic DNA was used as a template. Genomic copy number aberrations were analyzed using the SurePrint G3 Hmn CGH 60 k Oligo Microarray (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), in accordance with previous reports.17 Briefly, 250 ng each of target and reference DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes, AluI and RsaI. Cy-5 (target) or Cy-3 dUTP (reference) was incorporated using the Klenow fragment. The array was hybridized with labeled DNAs in the presence of Cot-1 DNA (Life Technologies) and blocking agents (Agilent Technologies) for 24 hours at 65°C, washed, and scanned on a scanner (Agilent Technologies). Data were extracted using Agilent Feature Extraction software version 10 with the default settings for aCGH analysis. Statistically significant aberrations were determined using the ADM-II algorithm in Agilent Genomic Workbench software version 6.5 (Agilent Technologies). Genomic locations were referenced according to Genome Reference, GRCh37/hg19.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

DNA libraries for whole-genome sequencing were constructed using TrueSeq Nano DNA Library Kit (Illumina), and sequenced using 150-bp paired-end reads on a NovaSeq6000 sequencer (Illumina). The average fold coverage was >30 (total number of bases ranging from 103.9 to 126.8 Gbp). After quality-based read trimming, sequence reads were aligned to the human reference genome GRCh37/hg19 using BWA-MEM,18 and then processed by various structural variation calling tools: BreakDancer,19 BreakSeq2,20 Pindel,21 CNVnator,22 and their integration method MetaSV.23

Read Depth–Based Copy Number Analyses using WES Data

The read depth of coverage for each exon in the RefSeq Genes was calculated and normalized using CalculateHsMetrics in Picard Tools (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Copy number states around the CBWD1 locus were assessed by comparing the normalized coverage values excluding large outliers in the present family members. EXCAVATOR2 (https://github.com/matheuscburger/Excavator2) was also used to confirm the exact copy number of the presumed hemizygous members. The window size was set to 1000 bases, and analysis was performed in the paired mode using II.3 as a normal control.

Immunohistochemistry

CBWD1 protein expression was examined in embryonic mouse kidneys (embryonic days 11.5–16.5), in neonatal mouse kidneys and in a kidney from an adult human donor. Approval for research on human subjects was obtained from the Central Ethics Board of Tokyo Women’s Medical University. The antibodies against the following proteins were used: CBWD1 (catalog number GTX120748; GeneTex, Irvine, CA), Cytokeratin 8 (catalog number ab53280; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and SIX2 (catalog number 11562–1-AP; Proteintech, Chicago, IL). Tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through serially gradated ethanol solutions and Tris-buffered saline. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes, followed by incubation with Protein Block (Genostaff, Tokyo, Japan) and avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The sections were incubated with anti-CBWD1, anti-Cytokeratin 8, and anti-SIX2 at 4°C overnight. They were then incubated with biotin-conjugated rabbit anti-rabbit Ig (Dako, Kyoto, Japan) for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by the addition of peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) for 5 minutes. Peroxidase activity was visualized by diaminobenzidine. The sections were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin (MUTO, Tokyo, Japan), dehydrated, and then mounted with Malinol (MUTO).

Generation of Cbwd1-Deficient Mice

We generated two lines of Cbwd1-deficient mice as follows. Cbwd1 gRNA vectors were constructed with pT7-sgRNA and pT7-hCas9 plasmids (gifts from Dr. M. Ikawa, Osaka University).24 After digestion of pT7-hCas9 with EcoRI, hCas9 mRNA was synthesized using an in vitro RNA transcription kit (mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit; Ambion, Austin, TX), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. A pair of oligonucleotides targeting Cbwd1 was annealed and inserted into the BbsI site of the pT7-sgRNA vector. The sequences of the gRNAs were as follows: 5′-GGCGGAAGAAGAGTACGCGG-3′ and 5′-ACAATTGTCACCGGGTACTT-3′. Both are located in exon 1 of Cbwd1 to generate Cbwd1-deficient mice. After the digestion of pT7-sgRNA with XbaI, gRNAs were synthesized using the MEGAshortscript kit (Ambion). We used C57BL/6N female mice (purchased from Clea-Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) to obtain C57BL/6N eggs, and performed in vitro fertilization with these eggs. In brief, Cas9 mRNA and gRNA were introduced into fertilized eggs by electroporation (Genome Editor electroporator; BEX Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), in accordance with previously reported protocols,25 after which we transferred the eggs to the oviducts of pseudopregnant females on the day when a vaginal plug was found. Founder mice harboring a mutant Cbwd1 allele were crossed with wild-type mice to obtain Cbwd1 heterozygous mice. After segregating the Cbwd1 mutant alleles, homozygous mice were used for additional analysis.

Results

Case Report

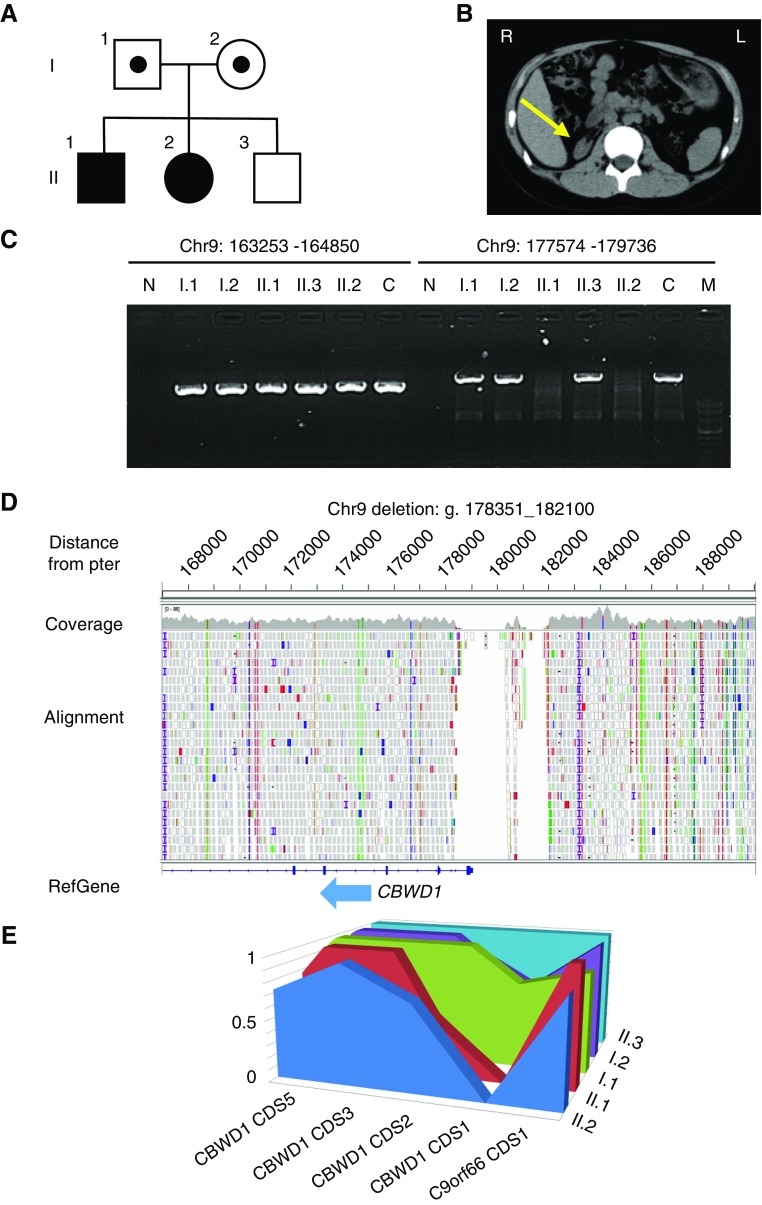

A kindred with CAKUT was referred to our institution for ESKD treatment (Figure 1A). The family consisted of nonconsanguineous parents (I.1 and I.2), two male siblings (II.1 and II.3), and one female sibling (II.2). Both the eldest male sibling and the female sibling presented with unilateral renal agenesis and contralateral renal hypoplasia (Figure 1B). Although CAKUT can appear as part of a systemic condition with extrarenal manifestations, the current cases were not accompanied by any other birth defects, such as coloboma, skeletal/digital, or genital anomalies or other clinical findings, including diabetes, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, or hyperuricemia. The other family members had no health problems, including in their kidneys. The renal function of the eldest son (II.1) gradually deteriorated such that at 6 years of age, he started chronic peritoneal dialysis, and at 10 years of age, he received a cadaveric kidney transplant. The female sibling (II.2) also demonstrated ESKD and received a living-related preemptive kidney transplant from her grandmother at 11 years of age.

Figure 1.

CBWD1 is identified as a candidate gene for CAKUT. (A) Pedigree of the family containing some members affected by CAKUT. Squares represent males, circles represent females, and shading indicates members with CAKUT. Carriers of genetic anomalies are indicated by a dot within the square or circle. (B) An arrow depicts hypoplasia of the right kidney on computed tomography images in Patient II.1. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis demonstrating genomic amplification of the coding region of CBWD1 exon 1. Validating PCRs using genomic DNAs from examined subjects indicated that a genomic segment between 177574 and 179736, which includes exon 1 of CBWD1 and harbors an initiating codon, was homozygously deleted in diseased siblings (II.1 and II.2) but not in the parents and the healthy sibling (II.3). Parents are I.1 (father) and I.2 (mother). A genomic segment between 163253 and 164850 at chromosome 9p was unaffected. (D) Whole-genome sequencing reads of an affected sibling (II.2) showing the 3.7 kb homozygous deletion (Chr9:178351_182100). A deletion at the CBWD1 locus involving the entirety of coding exon 1 was identified. (E) The relative normalized coverage of CBWD1 coding sequence (CDS) 1 of both parents (I.1 and I.2) was 0.69 and 0.59, compared with the coverage of the younger healthy brother (II.3). The coverage of the patients (II.1 and II.2) was zero. C, a nonrelated control individual; M, DNA Molecular Weight Marker VIII (Roche); N, negative control amplifying without template DNA.

Identification of CBWD1 as a Candidate Gene for CAKUT

Under the hypothesis that a gene harboring deleterious homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in autosomal recessive fashion may have caused CAKUT in this family, we performed WES using peripheral-blood DNA from all family members to identify candidate single-nucleotide variants and insertions and/or deletions. We did not find any single-nucleotide variants or insertions and/or deletions that existed only in the affected siblings including all 39 currently established causing genes for CAKUT (Supplemental Table 2).5 However, we identified a deletion in the affected siblings in the region of chromosome 9p24.3. The deletion seemed to span between at least Chr9:177574 and Chr9:179736 on GRCh37/hg19, which involved exon 1 of CBWD1, harboring an initiating codon. We designed primers to validate the deleted region and confirmed that this region was indeed homozygously deleted in the affected siblings but not in the parents and the healthy sibling (Figure 1C). Searching of the Database of Genomic Variants (http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home?ref=GRCh37/hg19) showed that a heterozygous deletion of this region was found in four out of 2538 individuals (0.16%) (accession number: gssvL128711).26 In this population, there were 2504 individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project, including 104 Japanese individuals. The deletion was not observed in this Japanese population. Because copy number variants (CNVs) might cause the disease,27,28 we also performed array-CGH analyses, which resulted in the detection of no obvious CNVs in the affected siblings (data not shown). This result suggested that any CNVs that might cause the disease could be less than detectable range or out of probing regions for the array-CGH we used.

We attempted to determine breakpoints of the deletion by performing long-range PCR and primer walking; however, we could not determine them because of the presence of highly repetitive sequences in this region. CBWD1 is located at 9p24.3:121038–179075 (GRCh37/hg19). This region is known to be segmentally quadruplicated and rearranged with transposition and translocation, which results in highly homologous sequences in two closely located segments at 9q21.11 and one segment at 2q13.29 For precise determination of the deleted regions, we carried out additional whole-genome sequencing for the affected sibling (II.2) and the parents (I.1 and I.2), which uncovered a homozygous deletion spanning from Chr9:178351 to Chr9:182100 involving the entire coding exon 1 of CBWD1 in the affected sibling (Figure 1D).

To analyze whether the parents had heterozygous deletion or not, we calculated normalized coverage values of coding sequences around CBWD1 using CollectHsMetrics (Picard), and found that the patients’ coverage was zero. Although the younger healthy brother’s coverage was 0.39, the parents’ coverage was 0.27 (69%) and 0.23 (59%), which were within the range fitting heterozygosity (Figure 1E, Supplemental Figure 1). We also analyzed the copy number profiles of the region containing a potential deletion in chromosome 9 using EXCAVATOR2.30 Heterozygous exon 1 deletion in the CBWD1 gene was also validated in the parents’ sample (Supplemental Figure 2).

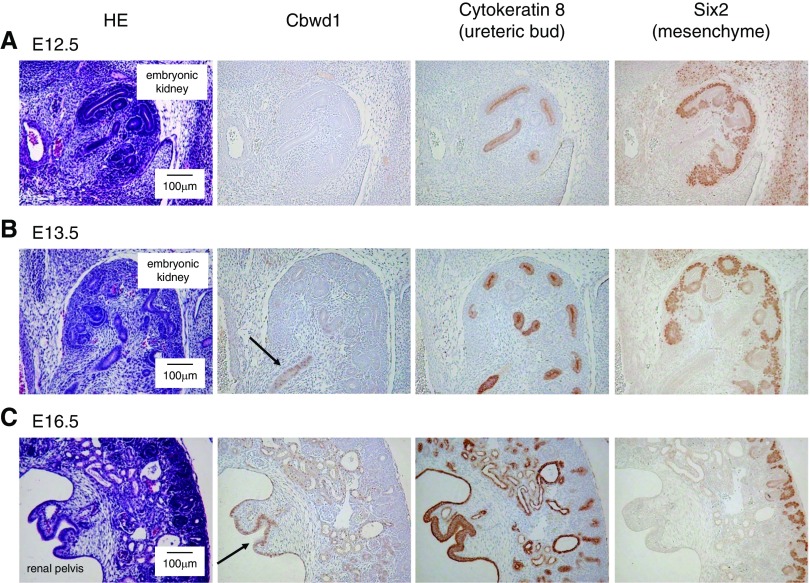

Expression Patterns of Cbwd1

To examine the significance of CBWD1 in the development of the genitourinary system, we first investigated the localization of CBWD1 by immunohistochemistry. Antibodies against CBWD1, SIX2, and Cytokeratin 8 were used for immunohistochemical staining of mouse embryonic kidneys. SIX2 and Cytokeratin 8 are known as markers of mesenchyme cells and the ureteric bud in the developing kidney, respectively.31,32 We found that Cbwd1 was present in kidneys at E13.5 but not at E11.5 or E12.5 (Figure 2, A and B, Supplemental Figure 3). Cbwd1 was primarily observed in the ureteric bud epithelial cells labeled with anti-Cytokeratin 8 in serial sections (Figure 2B). At E16.5, the staining became more intense in the ureteric bud (Figure 2C). In an adult human kidney specimen, CBWD1 was not observed (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Cbwd1 is expressed in the ureteric bud cells. (A–C) Serial sections of developing mouse kidneys at E12.5 (A), E13.5 (B), and E16.5 (C). The first section shows hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and the other sections show immunoperoxidase labeling for Cbwd1 (second section), SIX2 (third section), and Cytokeratin 8 (fourth section). Cbwd1 was detected in the nuclei of ureteric bud cells at E13.5 and at E16.5 (arrow).

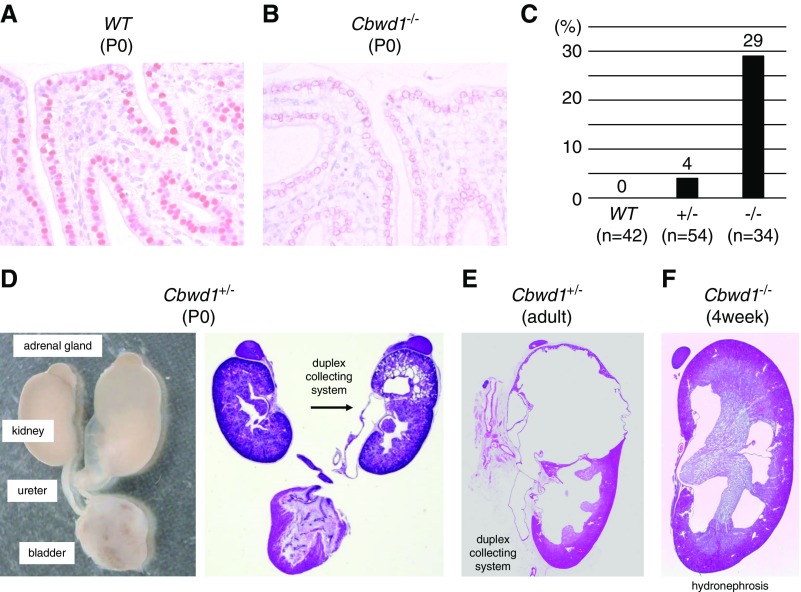

Kidney Defects in Cbwd1-Deficient Mice

To uncover the role of CBWD1 in the development of the urinary tract, we generated Cbwd1-deficient mice (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em1) by CRISPR-Cas9 gene targeting and examined their phenotypes. Homozygous mice were born at Mendelian frequency and did not suffer premature mortality (Supplemental Table 3). We determined the edited sequence (Supplemental Figure 5) and confirmed the loss of Cbwd1 in the nuclei of the ureteric bud cells (Figure 3, A and B). To characterize the CAKUT phenotypes of Cbwd1-deficient mice, we examined the morphology of 34 Cbwd1−/− mice, 54 Cbwd1+/− mice, and 42 wild-type mice. Overall, 29% of Cbwd1−/− mice and 4% of Cbwd1+/− mice had grossly identifiable CAKUT, whereas no abnormal phenotype was found in any of the wild-type mice (Figure 3C). CAKUT found in the Cbwd1-deficient mice were hydronephrosis, hydroureters, and duplicated ureters (Figure 3D). These phenotypes were considered to be associated with failed expression of Cbwd1 in the ureteric bud during the development of the urinary tract. Cbwd1+/− and Cbwd1−/− mice survived to adulthood, for which prospective dissection also identified CAKUT, including duplicated ureters and hydronephrosis (Figure 3, E and F). To rule out off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9, we also analyzed an independent line of Cbwd1-deficient mice (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em2) and confirmed similar results (Supplemental Figures 6–8, Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 3.

Cbwd1 mutants (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em1) show kidney and urinary tract defects. (A and B) Cbwd1 localization in the renal pelvis of neonatal (P0) mice. (A) Cbwd1 is localized in nuclei of the epithelium in wild-type mice. (B) Nuclear staining is lost in Cbwd1−/− mice. (C) Percentages of newborn mice with CAKUT. (D) Representative images of gross anatomy (left) and light microscopic histology of CAKUT found in a Cbwd1+/− pup at P0 (right). The left kidney presented with hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and duplicated ureter (arrow). (E) Hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and duplicated ureter observed in a Cbwd1+/− adult mouse. (F) Hydronephrosis found in a 4-week-old Cbwd1−/− mouse.

Discussion

We identified that a deletion in CBWD1 is involved in CAKUT etiology, as supported by several lines of evidence. First, we found a homozygous deletion in CBWD1 in patients with autosomal recessive CAKUT. Second, we showed that Cbwd1 was expressed in the kidney during development. Third, and most significantly, Cbwd1-deficient mice showed CAKUT phenotypes.

The function of CBWD1 was not known until now. Our results show that CBWD1 is associated with the development of the ureteric bud into the urinary tract. Some phenotypic differences were observed between the patients and the mouse model. Specifically, the patients with homozygous deletion involving CBWD1 showed renal agenesis; however, some Cbwd1-deficient mice showed duplicated ureters. Although these phenotypic differences may be attributable to species differences,33 both phenotypes could be interpreted as primary defects at the level of ureter budding. For example, the nephric duct–specific inactivation of Gata3, a transcription factor expressed in the ureteric bud, also results in a spectrum of urinary tract malformations including kidney agenesis and duplex systems and hydroureter.34 This kind of phenotypic variation is frequently observed in genetic studies of CAKUT.14 Many established CAKUT-causing genes encode transcription factors. Because Cbwd1 was also localized in the nuclei of the ureteric bud cells (Figure 3A), it may influence the transcription network in the developing kidney. However, the molecular mechanisms of CBWD1-mediated kidney development remain to be resolved.

The deletion detected in this study involved exon 1 of CBWD1 harboring the initiating codon. Deletion of the first coding exon usually results in a gross deletion of the affected transcripts. If there are multiple transcriptional variants, loss may be avoided depending on the variant using alternative first exons. By applying the public database GTEx Portal (https://gtexportal.org/home/documentationPage), we found that two types of transcriptional variants are mainly expressed in human tissues: [ENST00000356521.8] and [ENST00000382447.8]. Because the initiating codons of both variants are in the deleted region detected in this study, it can be said that the expression of the CBWD1 gene is almost lost in the patients’ tissues.

CBWD1 is located at 9p24.3:121038–179075 (GRCh37/hg19), which maps near the 9p telomere. The deletion 9p syndrome is clinically characterized by dysmorphic facial features, hypotonia, and mental retardation. Although abnormal external genitals are frequently seen (15 out of 36 cases),35 renal malformation is one of the rare features (one out of 13 cases).36 The patients in our study presented with CAKUT without other clinical manifestations and the parents were healthy. It is thought that these phenotypic differences between reported patients with the deletion 9p syndrome and the family in our study are attributable to cytogenetic differences. The deletion 9p syndrome is caused by constitutional monosomy of part of the short arm of chromosome 9. In addition, the deletion is large, varying from 800 kb to 12.4 Mb.37 In contrast, the deletion observed in our patients was homozygous and 3.7 kb in size.

In conclusion, our results implies a role for CBWD1 in CAKUT etiology. Cbwd1 is localized in the ureteric bud and promotes its development into the kidney collecting system.

Disclosures

None.

Funding

The study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [KAKENHI] 25870536, 15K21385, and 17K09689); by the Japanese Association of Dialysis Physicians, Japan (grant 2014-13); and by research funds from the Kawano Masanori Memorial Public Interest Incorporated Foundation for Promotion of Pediatrics, the Mother and Child Health Foundation, and the Takeda Science Foundation, Japan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kanda and Dr. Hattori designed the study. Dr. Kanda, Dr. Kaneko, Dr. Sugawara, Dr. Ishizuka, Dr. Miura, and Dr. Hattori treated the patients. Dr. Ohmuraya and Dr. Araki generated knockout mice. Dr. Akagawa, Dr. Yamamoto, and Dr. Furukawa performed genetic analyses. Dr. Kanda, Dr. Horita, and Dr. Yoshida performed mouse analyses and immunohistochemical experiments. Dr. Kanda wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Dr. Kanda, Dr. Ohmuraya, Dr. Akagawa, Dr. Harita, Dr. Oka, Dr. Furukawa, and Dr. Hattori contributed to manuscript review and editing. Dr. Kanda, Dr. Oka, and Dr. Hattori were involved in funding acquisition. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

We gratefully acknowledge the hospital staff for their help and support. We also thank Mitsuhiro Amemiya and Akira Saito (StaGen Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for help with processing of the next-generation sequencing data. We are also grateful to GenoStaff Co. for their support with the immunohistochemistry. Finally, we thank Jeremy Allen, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019040398/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Sequence performance data of the whole-exome sequence using SOLiD 5500 system.

Supplemental Table 2. The coverage of the WES for 39 currently established monogenic causing genes for CAKUT.

Supplemental Table 3. Genotype analysis of 4-week-old mice (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em1).

Supplemental Table 4. Genotype analysis of 4-week-old mice (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em2).

Supplemental Figure 1. Normalized coverage of the coding sequence around CBWD1.

Supplemental Figure 2. The copy number profiles of the parents in the region containing a potential deletion in chromosome 9 from EXCAVATOR2.

Supplemental Figure 3. Cbwd1 was not observed in E11.5 mouse kidneys.

Supplemental Figure 4. CBWD1 was not observed in an adult human kidney.

Supplemental Figure 5. DNA sequencing of the Cbwd1 locus from Cbwd1-deficient mice (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em1).

Supplemental Figure 6. DNA sequencing of the Cbwd1 locus from the Cbwd1 mutant (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em2).

Supplemental Figure 7. Percentages of newborn mice with CAKUT (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em2).

Supplemental Figure 8. CAKUT in Cbwd1 mutant mice (C57BL/6N-Cbwd1em2).

References

- 1.Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ: Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 27: 363–373, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivante A, Hildebrandt F: Exploring the genetic basis of early-onset chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 133–146, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hattori M, Sako M, Kaneko T, Ashida A, Matsunaga A, Igarashi T, et al.: End-stage renal disease in Japanese children: A nationwide survey during 2006-2011. Clin Exp Nephrol 19: 933–938, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JM, Stablein DM, Munoz R, Hebert D, McDonald RA: Contributions of the transplant registry: The 2006 annual report of the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS). Pediatr Transplant 11: 366–373, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaou N, Renkema KY, Bongers EM, Giles RH, Knoers NV: Genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors involved in CAKUT. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 720–731, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichikawa I, Kuwayama F, Pope JC 4th., Stephens FD, Miyazaki Y: Paradigm shift from classic anatomic theories to contemporary cell biological views of CAKUT. Kidney Int 61: 889–898, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schedl A: Renal abnormalities and their developmental origin. Nat Rev Genet 8: 791–802, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMahon AP: Development of the mammalian kidney. Curr Top Dev Biol 117: 31–64, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costantini F: Genetic controls and cellular behaviors in branching morphogenesis of the renal collecting system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 1: 693–713, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanna-Cherchi S, Sampogna RV, Papeta N, Burgess KE, Nees SN, Perry BJ, et al.: Mutations in DSTYK and dominant urinary tract malformations. N Engl J Med 369: 621–629, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vivante A, Kohl S, Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Hildebrandt F: Single-gene causes of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) in humans. Pediatr Nephrol 29: 695–704, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knüppel T, Charbit M, Dusek J, Ghiggeri GM, et al.: Prevalence of mutations in renal developmental genes in children with renal hypodysplasia: Results of the ESCAPE study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2864–2870, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Kohl S, Saisawat P, Vivante A, Hilger AC, et al.: Mutations in 12 known dominant disease-causing genes clarify many congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int 85: 1429–1433, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Ven AT, Vivante A, Hildebrandt F: Novel insights into the pathogenesis of monogenic congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 36–50, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Ven AT, Connaughton DM, Ityel H, Mann N, Nakayama M, Chen J, et al.: Whole-exome sequencing identifies causative mutations in families with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2348–2361, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa T, Kuboki Y, Tanji E, Yoshida S, Hatori T, Yamamoto M, et al.: Whole-exome sequencing uncovers frequent GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Sci Rep 1: 161, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett MT, Scheffer A, Ben-Dor A, Sampas N, Lipson D, Kincaid R, et al.: Comparative genomic hybridization using oligonucleotide microarrays and total genomic DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 17765–17770, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Durbin R: Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD, Larson DE, Kalicki JM, Pohl CS, et al.: BreakDancer: An algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods 6: 677–681, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abyzov A, Li S, Kim DR, Mohiyuddin M, Stütz AM, Parrish NF, et al.: Analysis of deletion breakpoints from 1,092 humans reveals details of mutation mechanisms. Nat Commun 6: 7256, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z: Pindel: A pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25: 2865–2871, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abyzov A, Urban AE, Snyder M, Gerstein M: CNVnator: An approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res 21: 974–984, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohiyuddin M, Mu JC, Li J, Bani Asadi N, Gerstein MB, Abyzov A, et al.: MetaSV: An accurate and integrative structural-variant caller for next generation sequencing. Bioinformatics 31: 2741–2744, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mashiko D, Fujihara Y, Satouh Y, Miyata H, Isotani A, Ikawa M: Generation of mutant mice by pronuclear injection of circular plasmid expressing Cas9 and single guided RNA. Sci Rep 3: 3355, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto M, Takemoto T: Electroporation enables the efficient mRNA delivery into the mouse zygotes and facilitates CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing. Sci Rep 5: 11315, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald JR, Ziman R, Yuen RK, Feuk L, Scherer SW: The Database of Genomic Variants: A curated collection of structural variation in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D986–D992, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber S, Landwehr C, Renkert M, Hoischen A, Wühl E, Denecke J, et al.: Mapping candidate regions and genes for congenital anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract (CAKUT) by array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 136–143, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanna-Cherchi S, Kiryluk K, Burgess KE, Bodria M, Sampson MG, Hadley D, et al.: Copy-number disorders are a common cause of congenital kidney malformations. Am J Hum Genet 91: 987–997, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin CL, Wong A, Gross A, Chung J, Fantes JA, Ledbetter DH: The evolutionary origin of human subtelomeric homologies--or where the ends begin. Am J Hum Genet 70: 972–984, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Aurizio R, Pippucci T, Tattini L, Giusti B, Pellegrini M, Magi A: Enhanced copy number variants detection from whole-exome sequencing data using EXCAVATOR2. Nucleic Acids Res 44: e154, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, Carroll TJ, Self M, Oliver G, et al.: Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell 3: 169–181, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue S, Inoue M, Fujimura S, Nishinakamura R: A mouse line expressing Sall1-driven inducible Cre recombinase in the kidney mesenchyme. Genesis 48: 207–212, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindström NO, McMahon JA, Guo J, Tran T, Guo Q, Rutledge E, et al.: Conserved and divergent features of human and mouse kidney organogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 785–805, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grote D, Boualia SK, Souabni A, Merkel C, Chi X, Costantini F, et al.: Gata3 acts downstream of beta-catenin signaling to prevent ectopic metanephric kidney induction. PLoS Genet 4: e1000316, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huret JL, Leonard C, Forestier B, Rethoré MO, Lejeune J: Eleven new cases of del(9p) and features from 80 cases. J Med Genet 25: 741–749, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swinkels ME, Simons A, Smeets DF, Vissers LE, Veltman JA, Pfundt R, et al.: Clinical and cytogenetic characterization of 13 Dutch patients with deletion 9p syndrome: Delineation of the critical region for a consensus phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 146A: 1430–1438, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hauge X, Raca G, Cooper S, May K, Spiro R, Adam M, et al.: Detailed characterization of, and clinical correlations in, 10 patients with distal deletions of chromosome 9p. Genet Med 10: 599–611, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.