Abstract

Background and aims:

Many inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients do not respond to medical therapy. Tofacitinib is a first in class, partially selective inhibitor of Janus kinase, recently approved for treating patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). We describe our experience with the use of tofacitinib for treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe IBD.

Methods:

This is a retrospective, observational study of the use of tofacitinib in IBD. Patients with medically resistant IBD were treated orally with 5 mg or 10 mg twice daily. Clinical response and adverse events were assessed at 8, 26, and 52 weeks. Objective response was assessed endoscopically, radiologically, and biochemically.

Results:

58 patients (53 UC, 4 Crohn’s, 1 pouchitis) completed at least 8 weeks of treatment with tofacitinib. 93% of the patients previously failed treatment with anti-TNF. At 8 weeks of treatment, 21 patients (36%) achieved a clinical response, and 19 (33%) achieved clinical remission. Steroid-free remission at 8 weeks was achieved in 15 (26%) patients. Of the 48 patients followed for 26 weeks, 21% had clinical, steroid-free remission. Of the 26 patients followed for 12 months, 27% were in clinical, steroid-free remission. Twelve episodes of systemic infections were noted, mostly while on concomitant steroids. One episode of zoster infection was noted during follow up.

Conclusions:

In this cohort of patients with moderate-to-severe, anti-TNF resistant IBD, tofacitinib induced clinical response in 69% of patients. 27% were in clinical, steroid-free remission by one year of treatment. Tofacitinib is an effective therapeutic option for this challenging patient population.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, tofacitinib, Jak inhibitors

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting 3.1 million Americans with an increasing incidence worldwide[1]. The pathogenesis of the disease is thought to involve a complex interaction between the immune system and genetic, environmental and microbial factors[2]. Until recently, the major treatment options have included 5-ASAs, immunomodulators, and biologic therapies that consist of antibodies that target tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), integrins, and anti IL23/12 antibodies[3]. However, despite these diverse treatment options, a large number of patients are not responsive or eventually lose response to therapy[4,5].

Tofacitinib is an oral, partially selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor. It is a small molecule that works intracellularly to inhibit JAK-dependent cytokine signaling. JAK1 and JAK3, which mediate the intracellular effects from several inflammatory cytokines, are the major targets of the drug in vivo and their inhibition results in modulation of the immune and inflammatory response[6]. Several inflammatory cytokines play a specific role in IBD pathogenesis by utilizing the JAK pathway. These include IFNα, IFNβ, IL-6, IL 7, IL 10, IL-12, IL-15, IL-21 and IL-23[7]. Tofacitinib has been FDA approved for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) since 2012. Three large clinical trials have demonstrated tofacitinib’s effectiveness in inducing (OCTAVE 1 and 2), and maintaining (OCTAVE Sustain) remission in patients with UC[8]. Tofacitinib was recently approved by the FDA and EMA for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe active UC. We report our experience with tofacitinib for medically resistant IBD.

Methods

Patients and Data collection

We performed a retrospective observational study describing the use of tofacitinib at the IBD Center at the University of Chicago. All adult patients with IBD treated with tofacitinib between December 2014 and July 2018 were included in the study. The diagnosis of CD or UC was established using standard clinical, endoscopic, and histologic criteria. All patients had completed at least 8 weeks of treatment of either 5 or 10 mg of tofacitinib given twice daily. All patients treated until May 30th 2018 received off-label tofacitinib. Patients treated after FDA approval received the drug as part of their standard of care management. In some cases, corticosteroids where given with the drug due to active symptoms. Later, it was tapered, according to the clinical response, at the treating physicians’ discretion.

Patients’ demographic, clinical, laboratory, radiographic, and endoscopic data were attained by a comprehensive review of their electronic medical records. The following baseline characteristics were recorded: patient features (age, gender, smoking status, and other medical history), disease features (age at diagnosis, duration of disease, disease location and phenotype according to Montreal classification, and prior treatment), tofacitinib treatment (induction and maintenance doses, duration of treatment, and concomitant therapy), biochemical inflammatory markers [(C-reactive protein (CRP), fecal calprotectin (FCP)], and endoscopic findings. Clinical response and adverse events were assessed at 8 weeks (induction), at 26 weeks (maintenance), 52 weeks, and at the last available follow-up. Objective outcomes were evaluated when possible from the patient’s medical record including CRP, FCP, imaging, and endoscopy. The study was approved by the institutional ethics review board. None of the patients participate in other tofacitinib clinical trial (including the OCTAVE program).

Outcomes

Response to treatment was determined as defined by the patient’s provider and the decision to continue therapy. Response was defined as symptomatic improvement but not resolution, and remission was defined as complete resolution of clinical symptoms. Endoscopic improvement was defined as decrease in the Mayo endoscopic subscore determined by the physician performing the procedure. The absence of significant improvement in symptoms, cessation of treatment with tofacitinib, or referral for surgery were defined as failure to response. A relapse was defined as a therapeutic failure developing after the initial response was achieved, or when the patient or provider decided to stop treatment. Adverse events which have previously been associated with tofacitinib treatment were retrospectively assessed. These include infections, changes in lipid profile, reduced creatinine clearance, elevation in liver enzymes and changes in hematological counts.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are provided using means and standard deviation for continues variables and proportions with 95% confidence interval for discrete variables. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of continues variables. Mann–Whitney U test was used as non-parametric test for the relevant comparisons. Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed for treatment failure-free survival. P-value < 0.05 was considered as a threshold of statistical significance. Prism version 7 was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 80 patients were prescribed with tofacitinib in our center thus far. Of those, 13 patients have not yet completed 8 weeks of treatment, and 9 were excluded due to other reasons (treatment was denied by insurance, decision was made to proceed to surgery, adherence, and lost to follow-up). Fifty-eight patients completed at least 8 weeks of treatment with tofacitinib during the 3 year study period. Of those, 49 patients were treated before the drug was ultimately approved by the FDA. Fifty-three patients (91%) had a diagnosis of UC, four (7%) had ileocolonic CD and one patient had resistant pouchitis after ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). The median follow-up time was 10.6 months (Interquartile Range 5.6–21.8 months). All patients but 4 had previously failed treatment with anti-TNF (93%) and 81% had failed anti-integrin. The patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Total number of patients | 58 |

|---|---|

| Disease | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 53 |

| E2 | 24 |

| E3 | 29 |

| Crohn’s disease | 4 |

| Pouchitis | 1 |

| Gender (M/F) | 36/22 |

| Age at induction, years {median (IQR)} | 39.7 (29–53) |

| Duration of disease, years {median (IQR)} | 10.4 (3.1–14.3) |

| Hemoglobin at induction, gr/dL {median (IQR)} | 13.55 (12.5–14.8) |

| LDL Cholesterol at induction, mg/dL {median (IQR)} | 100 (76–118.5) |

| Previous medications {number (%)} | |

| Anti TNF | 54 (93%) |

| Vedolizumab | 47 (81%) |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (79%) |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 23 (40%) |

| Ustekinumab | 2 (3%) |

| Concomitant medications {number (%)} | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 27 (47%) |

| Immunomodulators | 5 (9%) |

| Vedolizumab | 3 (5%) |

| Prednisone dose equivalent, mg {median (IQR)} | 15 (10–27.5) |

| Clinical follow-up duration, months {median (IQR)} | 10.6 (5.6–21.8) |

Clinical response and remission

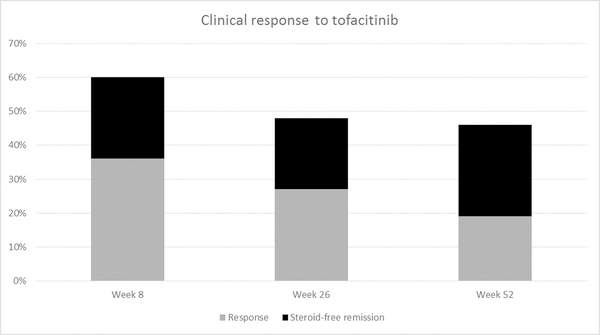

A total of 58 patients completed 8 weeks of treatment. Of them, 21 patients (36%) had a clinical response. 19 patients (33%) achieved clinical remission, of which 14 (24%) were also steroid-free.

Forty-eight patients were followed for at least 26 weeks. Of them, 13 patients (27%) had clinical response, and 12 (25%) were in clinical remission. All but two patients were also steroid-free this time point (21%). 24/25 patients (96%) in this group were already responsive at the end of induction.

A total of 26 patients completed 52 weeks of follow up. Five patients (19%) were clinically responsive to the drug. Seven patients (27%) were in clinical, steroid-free remission at this time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Response rates to tofacitinib

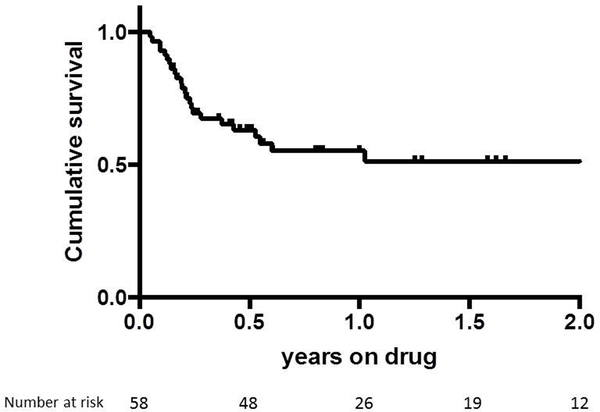

The proportion of patients still being maintained on tofacitinib at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months was 69%, 55%, and 51% respectively (Figure 2), demonstrating sustained efficacy of therapy in a majority of patients. Furthermore, patients receiving tofacitinib were able to reduce their corticosteroid doses from a median of 10 mg to a median 0 mg.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of failure-free response to tofacitinib

Twenty-six patients discontinued the drug secondary to poor response or adverse events and were subsequently treated surgically or medically. Fourteen patients with UC underwent total proctocolectomy and one patient with CD required fecal diversion to achieve remission (and was left with diverting ileostomy by the end of follow-up after 2 years). There was a washout period of at least 24 hours before surgery. The other patients who failed the drug were treated medically with anti-TNFα, anti-integrin, anti IL12/23 (without prior washout period), or experimental clinical trial drug.

Dose

The induction dose was 5 mg twice daily for 22 of the patients (38%), and 10 mg twice daily for 35 patients (60%). One patient received 11 mg daily of the extended release formulation. The initial dose of tofacitinib was not correlated with clinical response at 8 weeks (Table 2). 10 patients on 5 mg twice daily required dose escalation to 10 mg twice daily, and eight had a positive clinical response.

Table 2.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with and without response

| Response week 8 (40 patients) |

Non-response week 8 (18 patients) |

P - value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | UC - E2 | 18 (45%) | 6 (33%) | 0.57 |

| UC - E3 | 18 (45%) | 11 (61%) | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 4 (10%) | 1 (6%) | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 25/15 | 11/7 | 1 | |

| Age at induction {median (IQR)} | 41.5 (28.8–53) | 37.5 (31–46.8) | 0.77 | |

| Duration of disease {median (IQR)} | 10.66 (2.1–17.2) | 10.3 ± 8.2 | 0.44 | |

| Previous medications {number (%)} | Anti TNF | 39 (98%) | 15 (83%) | 0.08 |

| Vedolizumab | 33 (83%) | 14 (78%) | 0.72 | |

| Immunomodulators | 29 (73%) | 12 (67%) | 0.76 | |

| Objective active disease at induction | 22 (55%) | 11 (61%) | 0.57 | |

| Treatment dose | 5 mg | 19 (47%) | 4 (22%) | 0.08 |

| 10 mg | 21 (53%) | 14 (78%) | ||

| Concomitant steroids {number (%)} | 17 (43%) | 10 (56%) | 0.70 | |

| Prednisone dose equivalent, mg {median (IQR)} | 15 (10–20) | 10 (8.1–40) | 0.95 |

A trial of off-label short time (2–4 weeks), high dose treatment (15 mg twice daily) was done in seven patients with severe resistant disease and showed limited effect. Three patients had subsequent clinical improvement that was sustained with standard dose of 10 mg twice daily.

Predictors of response

Patients’ demographic characteristics, disease extent, previous medical therapy, and steroid exposure were not predictive of clinical response during induction or maintenance treatment. Drug dose at induction was not correlated with the clinical response at 8 weeks or during maintenance follow up. There was no significant difference between clinical response in UC and CD patients (data shown for week 8 response in Table 2).

Objective evaluation

Prior to tofacitinib initiation, all patients had active disease evaluated by endoscopy. During follow-up, endoscopic re-evaluation was performed in 13/58 patients at least 8 weeks after drug initiation. Mucosal healing (defined as Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0) was demonstrated in 2 patients and endoscopic improvement was noted in 5 others. Prior to therapy initiation, 25 patients had elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers (CRP and FCP); 8 of these patients had a demonstrable reduction of at least one third in these markers after being treated with tofacitinib.

Crohn’s disease

Four patients with CD were treated with tofacitinib with an inconsistent effect. One patient discontinued the treatment secondary to poor response. Three patients demonstrated clinical response with treatment. One patient, treated with concomitant thiopurine, achieved clinical remission that was sustained through week 140. At that point, however, his treatment was switched to ustekinumab due to active disease demonstrated on endoscopy. Clinical response was observed in one patient by week 10 (end of follow-up); and another patient achieved sustained clinical remission through week 26 accompanied by decrease in FCP.

Safety

Systemic infections were noted in 12 patients (20.1%). Seven of them were treated with immunosuppressive therapy in addition to tofacitinib at the time of infection (Table 3). Cellulitis was diagnosed in one patient, and upper respiratory tract infections were diagnosed in two patients. All 3 patients were treated with concomitant steroids. Tofacitinib was halted temporarily for 2 of the patients and was re-administered once infection was controlled. Four patients were diagnosed with a Clostridium difficile infection while on the drug. Three of them were on concomitant steroid therapy. Tofacitinib was temporarily halted at that time and the patients were treated with vancomycin. Three of the four patients continued to have clinically severe colitis; and two underwent total proctocolectomy. One patient was diagnosed with aspergillus sinusitis which required surgical debridement. The patient had a history of recurrent allergic fungal sinusitis that began prior to initiation of tofacitinib. One patient was diagnosed clinically with herpes zoster at an outside location. She was treated with valganciclovir for 14 days with complete resolution of her symptoms. Tofacitinib was later continued with no subsequent infectious events.

Table 3.

Adverse Events. List of individual adverse events experienced in the study (CMV = Cytomegalovirus, C. diff = Clostridium difficile, EBV = Epstein Barr Virus, URI = upper respiratory infection, E. Coli = Escherichia coli, Cr = creatinine, LDL = low-density lipoprotein)

| Infectious complications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient ID | Infection | Concomitant Therapy | Treatment Stopped | Treatment Re-started | |

| 1 | CMV colitis and C. diff Colitis | Prednisone 10 mg | Yes | No | |

| 2 | CMV colitis and C. diff Colitis | Prednisone 10 mg | Yes | No | |

| 3 | Aspergillus Sinusitis | Prednisone 5 mg | No | -- | |

| 4 | C. diff colitis | None | Yes | No | |

| 5 | GBS sepsis | Tacrolimus 1 mg | Yes | Yes | |

| 6 | C. diff colitis | Prednisone 10 mg | Yes | No | |

| 7 | Shingles | Prednisone 5 mg | Yes | Yes | |

| 8 | EBV | None | Yes | Yes | |

| 9 | Cellulitis | None | Yes | Yes | |

| 10 | Parainfluenza | Vedolizumab | Yes | No | |

| 11 | URI | Prednisone 10 mg | No | -- | |

| 12 | E. Coli gastroenteritis | Mesalamine 1.2 g | No | -- | |

| Laboratory Abnormalities | |||||

| Abnormality | Max Value | Concomitant Therapy | Treatment Stopped | Treatment Re-started | |

| 13 | Acute Kidney Injury | Cr 2.1 | Methotrexate, Mesalamine | No | -- |

| 14 | Hyperlipidemia | LDL 120 | Mesalamine, Entyvio | No | -- |

| 15 | Hyperlipidemia | LDL 143 | None | No | -- |

| 16 | Hyperlipidemia | LDL 113 | None | No | -- |

| Other Adverse Drug Events | |||||

| Abnormality | Concomitant Therapy | Treatment Stopped | Treatment Re-started | ||

| 17 | Cough, Dizziness, Parasthesias | Mesalamine | Yes | No | |

Three patients had an incline in their cholesterol level with maximal LDL of 143 mg/dL (increased from 115 mg/dL). None needed pharmacologic treatment, and tofacitinib was not stopped. No cardiovascular events were noted. One case of constitutional symptoms including headaches, dizziness, and cough resulted in drug discontinuation. Other than this patient, none of the adverse events led to permanent cessation of tofacitinib.

Discussion

Despite myriad new treatment options, management of patients with moderate to severe IBD remains a challenge. Our cohort included patients with moderate to severe IBD, of which the majority had previously failed to improve with at least two classes of biologic therapy. In this challenging patient population, a substantial percentage of patients responded to treatment with oral tofacitinib; after 8 weeks of treatment, clinical remission was achieved in 33% of patients. These rates are consistent with the rates reported in recent clinical trials. After a year of treatment, 42% of the patients remained in steroid-free clinical remission.

Phase 3 clinical trials have suggested a dose-response relationship with tofacitinib treatment during induction and maintenance. In our cohort, there was no statistically significant difference in clinical remission rates between patients receiving 5 mg and 10 mg for induction. However, there was an insignificant trend toward higher remission rates among the patients in the lower-dose group. This surprising finding may be explained by a selection bias to treat sicker patients with higher doses.

Almost all the patients in our cohort had previously failed treatment with anti-TNFs, and more than 80% had also failed anti-integrins. Treating these patients can be challenging, considering the limited treatment options in the arsenal for UC and the low efficacy rates of second line therapy after failure of the first biologic[9,10]. In out cohort, as has previously been demonstrated in clinical trials, previous failure of biologic therapy did not affect the efficacy of treatment. The majority of patients failing tofacitinib eventually underwent total proctocolectomy, further demonstrating the extreme refractoriness of this unique group of patients.

The JAK-STAT system plays a major part in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease[11]. Yet, tofacitinib had not been shown to be effective in the treatment of Crohn’s disease. A phase II clinical trial reported that tofacitinib treatment at a dose between 1 and 15 mg twice daily did not demonstrate a beneficial effect in induction or maintenance of clinical response compared to placebo. However, response and remission rates with placebo were higher than expected, and reductions in CRP and fecal calprotectin levels were observed with tofacitinib treatment, suggesting some level of biological activity[12,13]. However, our experience using tofacitinib in CD is limited to four patients with dissimilar results. Interestingly, another recent phase II clinical trial demonstrated the benefit of a selective JAK1 inhibitor, filgotinib, in CD[14].

The most commonly reported adverse event in the tofacitinib clinical trials were influenza-like symptoms, nasopharyngitis and increased levels of total cholesterol, and high and low density lipoprotein (HDL, LDL). Age above 65 years, corticosteroid dose above 7.5 mg, diabetes, and a tofacitinib dose of 10 mg vs. 5 mg, were independently linked to the risk of serious infection[15]. Specifically, higher rates of herpes zoster were observed among tofacitinib treated patients with RA and UC[16,17]. In these studies, age and prior anti-TNFα failure were found to be independent risk factors for herpes zoster among UC patients using tofacitinib. Among our cohort 12 patients (20%) experienced infectious complications during the entire follow-up period; most of them were on concomitant immunosuppressive therapy. One patient discontinued the drug due to an adverse event that was not infectious. We observed one case of HZ in a patient, who was not vaccinated, and the infection resolved completely with anti-viral therapy.

There are several limitations to our study. First, it is retrospective. Accordingly, the follow-up and decision-making processes were biased. In addition, a considerable portion of the patients who reached clinical remission did not have objective evidence of disease quiescence (e.g. endoscopic evaluation or biochemical markers). Nevertheless, steroid-free clinical response and discontinuation of medical therapy are both well-known, clinically relevant endpoints. These limitations are inherent in this type of real-world publication and come alongside its advantages. This is the first report on the effect of tofacitinib for induction and maintenance in moderate-to-severe IBD in a real-world tertiary center setting. Our cohort is a real-life patient population that includes participants with complicated, long standing, extremely resistant disease, and reflects real life follow-up and decision-making process. We demonstrate good efficacy and safety of this new oral option for our patients.

Footnotes

Disclosures: RW MAG, KEJ and PHS have no relevant disclosures. DTR is a consultant and has received grant support from Abbvie, Abgenomics, Allergan Inc, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co Inc., Medtronic, Napo Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Pfizer, Shire and Target Pharmaceuticals. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

References:

- 1.Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, Wheaton AG, Croft JB. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Adults Aged >/=18 Years - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(42):1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142(1):46–54 e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen BL, Sachar DB. Update on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents and other new drugs for inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ 2017;357:j2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106(4):644–659, quiz 660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amiot A, Serrero M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. One-year effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46(3):310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodge JA, Kawabata TT, Krishnaswami S, et al. The mechanism of action of tofacitinib - an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34(2):318–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham C, Dulai PS, Vermeire S, Sandborn WJ. Lessons Learned From Trials Targeting Cytokine Pathways in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017;152(2):374–388 e374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376(18):1723–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2012;142(2):257–265 e251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013;369(8):699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivera P, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. JAK inhibition in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017;13(7):693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, Vranic I, Wang W, Niezychowski W. A phase 2 study of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12(9):1485–1493.e1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panes J, Sandborn WJ, Schreiber S, et al. Tofacitinib for induction and maintenance therapy of Crohn’s disease: results of two phase IIb randomised placebo-controlled trials. Gut 2017;66(6):1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Petryka R, et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease treated with filgotinib (the FITZROY study): results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389(10066):266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Radominski SC, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Analysis of infections and all-cause mortality in phase II, phase III, and long-term extension studies of tofacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(11):2924–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winthrop KL, Yamanaka H, Valdez H, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(10):2675–2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winthrop KL, Melmed GY, Vermeire S, et al. Herpes Zoster Infection in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Receiving Tofacitinib. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]