Abstract

Luminescent lanthanides provide a promising alternative to organic chromophores for cellular bioimaging and bioassay applications; efficacy is closely governed by their respective quantum yields. Conventionally utilized quantum-yield measurements for lanthanides are laborious and not amenable to rapid relative comparison of compound performance. Here, we introduce a high-throughput optical imaging method to determine and directly compare relative quantum yield using Cherenkov-radiation-mediated excitation of luminescent lanthanide complexes.

The sharp emission bands and long-lived nature of the f-f-based luminescence of lanthanides provide opportunities to develop optical light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), lasers, and probes for bioimaging and bioassay applications.1–4 The latter requires the development of hydrophilic, bifunctional coordination complexes with robust optical properties including a high quantum yield (Q.Y.).4–6 This poses a specific challenge, as the efficient sensitization of lanthanide luminescence requires the incorporation of a small chromophore, commonly referred to as an antenna, for efficient energy transfer to excited f-states: the synthesis of high-quantum-yield lanthanide complexes suitable for bioimaging applications is of ongoing interest and represents a considerable challenge.7–19 Small chemical modifications to the antenna and chelate structure can result in large changes in the corresponding lanthanide complex quantum yield.9,12,20 A significant impediment to selection and development of suitable bifunctional lanthanide complex systems is the rapid determination of effective, lanthanide-based quantum yields (ΦLn).21–23 Lower-quality monochromators or lack of long pass filters can result in codetection of an artifact arising from the second order of the excitation light, which can coincide with lanthanide-based emission peaks.7 We identified a need for complementary methods that evaluate and directly compare lanthanide complex quantum yields rapidly and relative to one another. We hypothesized that such a method could accelerate the development and selection of improved, lanthanide-based probes suitable for in vitro and in vivo imaging applications.

Recently, we have established Cherenkov radiation emitted by positron-emission tomography (PET) isotopes as a reliable in situ excitation source for discrete luminescent lanthanide complexes (Figure 1).24 The emission of Cherenkov radiation in water exhibits high relative intensity below 400 nm, which decreases (Figure 1, bottom) with a 1/λ2 dependence.25–27 This renders Cherenkov luminescence (CL) ideal for the antenna-mediated sensitization of lanthanide luminescence and direct detection using a state-of-the-art small animal bioimaging scanner. After establishing that [Tb(L1)]− with a ΦLn of 0.47 is efficiently excited with CL, we sought to further increase ΦLn to enhance CL-mediated excitation efficiency. We investigated ways to directly compare the performance of compounds of a rationally designed Tb(III) complex library by streamlining relative ΦLn measurements to enable measurements using a well-plate type assay.

Figure 1.

Top: Jablonski diagram illustrating excitation of the 5D4 state of Tb(III) via excitation of the ligand-based antenna.13,19 Bottom: Comparison of relative, calculated and wavelength-dependent Cherenkov-radiation emission of photons in water from 18F (blue), antenna absorbance (red), and characteristic emission of Tb(III) complexes (green) with distinct emission bands for 5D4−7FJ radiative transitions (J = 0–6).

Here, we show that CL-mediated excitation and subsequent, simultaneous top-down imaging of a library of terbium complexes directly compares lanthanide-emission-based relative quantum yields. Lanthanide-based emission is uniquely suited for this method because of the efficient shielding of the 4f orbitals, resulting in no ligand field effects on luminescence emission; only the relative intensity of peak emissions varies, whereas the emitted wavelength value remains constant and can be detected directly (Figures 1 and S24) using luminescence imaging.

A library of macrocycle-based terbium complexes with quantum yields (ΦLn) from 0.01 to 0.65 was produced by varying: (1) number of inner-sphere water ligands (q),28 (2) triplet energy of the antenna,29,30 and (3) Tb(III) ion-to-antenna distance.31,32 Ligands were synthesized by stepwise alkylation of cyclen, using either a bis- or tris-acetate functionalized scaffold (Figure 2 and Table 1). Ligands L1–L4 incorporate methyl picolinate as the sensitizing antenna (λex = 282 nm).33 Functionalized methyl picolinates are efficient sensitizers for Tb complexes and [Tb(L1)]− forms a q = 0 complex with a ΦLn of 0.47;34 thus, we concluded that modulation of the picolinate-based ligand environment could produce Tb complexes with a range of ΦLn.

Figure 2.

Tb(III) complexes explored in this work with varying quantum yields based on inner-sphere hydration, energy of the triplet state, and distance of the metal ion to the antenna chromophore.

Table 1.

Tb(III) Complex Photophysical Characterization Including Gradient-Based Q.Y. (ΦLn) and CL-Based Q.Y. (CR-ΦLn), Molar Absorptivity (ε), and Inner-Sphere Hydration Number (q)36

| complex | ΦLna | CL-ΦLn | ε/M−1·cm−1b | qa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Tb(L1)]− | 0.47 | 0.47 | 53 500 | 0.02 |

| [Tb(L2)] | 0.33 | 0.27 | 31 700 | 1.20 |

| [Tb(L3)] | 0.18 | 0.22 | 107 900 | 1.10 |

| [Tb(L4)] | 0.50 | 0.44 | 55 700 | 0.00 |

| [Tb(L5)]− | 0.65 | 0.78 | 47 565 | 0.00 |

| [Tb(L6)] | 0.05 | 0.06 | 15 100 | 0.97 |

| [Tb(L7)] | 0.03 | 0.06 | 34900 | 0.90 |

| [Tb(DOTA)]− | 0.01 | 0.04 | 18 300 | 0.91 |

Measured in DBPS buffered solutions at pH 6.5–7 with estimated relative error of 15% (Supporting Information).

At 275 nm.

[Tb(L2)] was synthesized as the monohydrated analogue of [Tb(L1)]−, as inner-sphere water ligands can result in deexcitation from the 5D4 state in a nonradiative fashion, effectively lowering ΦLn.35 [Tb(L3)] incorporates two picolinate substituents, enhancing molar absorptivity for a possible increase in ΦLn relative to [Tb(L1)]−. [Tb(L4)] incorporates a noncoordinating primary amine, which can result in luminescence quenching by N–H oscillation. Similarly, [Tb(L5)]− employs a methyl picolinate antenna with a primary amine in the para position. [Tb(L6)] and [Tb(L7)] were synthesized by coupling of boc-protected amino acids tyrosine and tryptophan to [4,7,10-Tris(tertbutoxycarbonylmethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraaza-1-cyclododecyl]acetic acid. The long antenna–Tb distance lowers the efficiency of energy transfer to the lanthanide, producing a low effective ΦLn with enhanced, ligand-based fluorescence ΦLn. The [Tb(DOTA)]− was used as nonantenna bearing reference complex.

We determined inner-sphere hydration number q using Horrocks’ equations36 and employed the established gradient-based method to determine ΦLn,37–39 with [Tb(L1)]− (ΦLn =0.47) as the internal reference.

Quantum-yield measurements produce the most consistent values at concentrations where absorbance remained below 0.1 to minimize errors based on inner filter effects but were affected by the second order emission in our setup, which overlaps with the Tb 5D4−7F5 (545 nm) transition under λex = 282 nm (Figures S1 and S2). Quantum-yield values calculated with this method incur a relative error of 10–15%, rendering comparison of compounds with a similar ΦLn especially difficult.

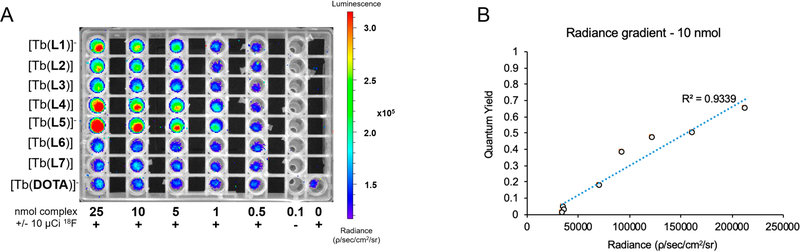

We proposed an imaging-based quantification method of ΦLn using CL to enable the direct, simultaneous side-by-side comparison of ΦLn of an array of compounds. To probe our hypothesis, we prepared a dilution series (0.5–25 nmol as quantified and adjusted by ICP-OES, in DPBS) of all complexes. Subsequently, a 10 μCi aliquot of Na18F was added to each dilution, and all samples were placed on the scanner platform of a small animal fluorescence imager. Images were acquired with blocked excitation and open emission collection from 500 to 875 nm. Radiance was quantified using region of interest (ROI) analysis. Cherenkov-only radiance was subtracted to calculate radiance arising exclusively from Tb-based emission. Luminescence images reveal the relationship of detected radiance (Figure 3A) with quantum yield (Figure 3B) and allow for assessment of relative ΦLn. A reliable relationship between quantum yield and observed radiance was established at 5 nmol and above (Figures 3B and S19−S23).

Figure 3.

(A) Images of plate containing all eight Tb complexes, with 10 μCi Na18F per sample. Cherenkov-only-based emission is shown in bottom-right corner well. (B) Quantum yield determined with the conventional gradient method using standard fluorimeter results plotted against radiance emission for 10 nmol of complex solution with of 10 μCi 18F.

To calculate the relative ΦLn of any compound X at 282 nm, based on the CL-mediated-emission radiance measurements, we first calculated the absorbance cross section (σx) at wavelengths of 220–400 nm as well as the corresponding cross section integral. The 220–400 nm wavelength range was selected as the antenna moieties employed here absorb predominantly within this spectral window. As Cherenkov radiation is emitted as a continuum and not just at one select wavelength, the detected emission must be scaled by the relative absorbance cross section of each antenna to give the scaling factor AX, as calculated by eq 1.

| (1) |

With the scaling factor AX in hand, the relative quantum yield based on radiance values obtained from the imaging experiment can be calculated using eq 2

| (2) |

where radiance (Rad) values are obtained from measurements of 5, 10, or 25 nmol of complex, and AX is calculated from the absorbance measurements at known compound concentrations using a conventional UV–vis spectrophotometer. The 0.1, 0.5, and 1 nmol samples do not provide discernible radiance signals to produce a strong correlation (Figures S22−24). Each CL ΦLn was determined with 10 nmol of complex and calculated for 282 nm. The absorbance cross-section and corresponding integral as well as AX for compounds studied here are provided in Table S4; the calculated, CL-based relative ΦLn value is provided in Table 1.

On the basis of CL-assisted ΦLn measurements, we were able to determine and rationalize observed relative differences in optical behavior among the compounds studied. For instance, although [Tb(L3)] was synthesized with the intent to mimic a high ΦLn (0.56) bis-picolinate q = 0 complex prepared by Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al.,40 measurements revealed ΦLn =0.18. Estimation of inner-sphere hydration showed q = 1, further confirming the coordination of only one of the two methyl picolinate antennae present. This results in efficient energy transfer from only one of the two antennae, with the second antenna likely undergoing ligand-based fluorescence or phosphorescence without subsequent energy transfer to terbium. CL-assisted imaging also reveals high-radiance emission for compounds [Tb(L4)] and [Tb(L5)]−. Both compounds incorporate amines bearing N–H oscillators, which have been proposed to promote radiationless deexcitation and decrease effective lanthanide-based luminescence.35 However, [Tb(L4)] and [Tb(L5)]− do not show a significant decrease of ΦLn. The pendant amine in [Tb(L4)] is likely not able to interact with the Tb metal center because of the encumbered, q = 0 coordination sphere and therefore does not impart a quenching effect. [Tb(L5)]− surprisingly exhibits the highest relative quantum yield. Measurement of the triplet excited state energy of the ligand reveals a blue-shift by 1330 cm−1, which limits efficiency of energy back-transfer to the antenna (Figures 1A and S3−S4, Table S1).41 A recent report by Junker et al.19 details that fast energy transfer rates from T1 to the lanthanide excited state can further enhance efficiency of the energy transfer from T1 states of antennas, which is another plausible explanation for the high relative quantum yield of [Tb(L5)]−.

On the basis of the CL-imaging-assisted quantum-yield screen, [Tb(L5)]− emerges as a suitable scaffold for developing improved, high-ΦLn Tb-based imaging probes. As expected, complexes [Tb(L6)] and [Tb(L7)] produced lower quantum yields reflected by diminished radiance emission. These results align with expectations, as the rate of energy transfer decays exponentially with Tb–antenna distance,42 promoting antenna-based fluorescence and phosphorescence processes instead. We note that the preferentially formed solution structures will govern the relative antenna-to lanthanide distance.

A direct comparison with quantum yields obtained using conventional methods shows good agreement (Table 1). Notably, CL efficiently quantifies ΦLn values above 0.05 and is especially efficient in revealing differences among complexes with ΦLn > 0.2. The direct visualization of lanthanide-based radiance efficiency allows for a rapid ΦLn screening and evaluation of a given compound library with respect to a known reference complex, in this case [Tb(L1)]−. We note that CL-based ΦLn quantification does not rely on one specific internal reference; rather, references may be used interchangeably. Furthermore, the consistent and high relative intensity of Cherenkov radiation at wavelengths suitable for lanthanide antenna excitation ascertains uniform excitation properties across various antenna types as long as the absorption cross sections are considered following eqs 1 and 2. The high-throughput nature of the presented method provides an approach to rapidly screen emission properties of lanthanide complexes comparable to multiwell fluorescence plate readers. For instance, this method also has the potential to simultaneously and rapidly evaluate the impact of various analytes and quenchers on the relative quantum yields of complexes with one single imaging experiment.

As with every method, drawbacks exist; hence, this method is not a stand-alone but complementary approach to other, more conventionally used measurements. The intrinsic background produced Cherenkov-radiation emission, even at long wavelengths, making accurate quantum-yield determination of complexes with ΦLn < 0.05 especially difficult. Additionally, the widespread application of CL-based ΦLn determination is further limited by the need for a top-down-emission imaging setup that allows quantitation of emission over an extended time frame (such as a small animal imager employed in this work), dependence of in situ excitation with a radioactive isotope, and a well-established reference compound.

In conclusion, we have established a new method to determine relative lanthanide-based quantum yield via Cherenkov-mediated excitation and subsequent, plate-based imaging. A library of Tb(III) complexes with relative quantum yields ΦLn from 0.01 to 0.65 was synthesized to establish the relationship among CL efficiency, radiance-based emission, and ΦLn. We show that CL-based determination of ΦLn is especially well-suited as a high-throughput method for the direct comparison for high-quantum-yield terbium(III) complexes, where differences may be difficult to discern using conventional methods of determining ΦLn. This method can be expanded to determine the relative quantum yield of complexes incorporating other lanthanides, provided the emission is within the detection window of the scanner (500–875 nm, Figure S24). Although 18F is especially well-suited as a CL source because of the large relative number of photons produced and the short half-life, reducing cost and radiation contamination impediment, other Cherenkov-emitting isotopes may be used interchangeably if appropriate references for intrinsic emission are established.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nikki A. Thiele and Justin Wilson are warmly acknowledged for providing ethyl 4-amino-6-(chloromethyl)picolinate for the synthesis of L5. Peter Smith-Jones is thanked for providing Na18 F.

Funding

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via a Pathway to Independence Award (NHLBI R00HL125728) and Stony Brook University for startup funds.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01786.

Chemical synthesis and characterization of terbium complexes, sample measurements, photophysical characterization, processing, and quantification (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Heffern MC; Matosziuk LM; Meade TJ Lanthanide probes for bioresponsive imaging. Chem. Rev 2014, 114 (8), 4496–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dwek RA; Richards RE; Morallee KG; Nieboer E; Williams RJ; Xavier AV The lanthanide cations as probes in biological systems. Eur. J. Biochem 1971, 21 (2), 204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Moore EG; Samuel APS; Raymond KN From Antenna to Assay: Lessons Learned in Lanthanide Luminescence. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42 (4), 542–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Petoud S; Cohen SM; Bünzli J-CG; Raymond KN Stable lanthanide luminescence agents highly emissive in aqueous solution: multidentate 2-hydroxyisophthalamide complexes of Sm3+, Eu3+, Tb3+, Dy3+. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125 (44), 13324–13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Montgomery CP; Murray BS; New EJ; Pal R; Parker D Cell-Penetrating Metal Complex Optical Probes: Targeted and Responsive Systems Based on Lanthanide Luminescence. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42 (7), 925–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pandya S; Yu J; Parker D Engineering emissive europium and terbium complexes for molecular imaging and sensing. Dalton Trans 2006, No. 23, 2757–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Monteiro JHSK; Dutra JDL; Freire RO; Formiga ALB; Mazali IO; de Bettencourt-Dias A; Sigoli FA Estimating the Individual Spectroscopic Properties of Three Unique EuIII Sites in a Coordination Polymer. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57 (24), 15421–15429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Walton JW; Carr R; Evans NH; Funk AM; Kenwright AM; Parker D; Yufit DS; Botta M; De Pinto S; Wong K-L Isostructural Series of Nine-Coordinate Chiral Lanthanide Complexes Based on Triazacyclononane. Inorg. Chem 2012, 51 (15), 8042–8056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Shuvaev S; Starck M; Parker D Responsive, Water-Soluble Europium (III) Luminescent Probes. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23 (42), 9974–9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Butler SJ; Delbianco M; Lamarque L; McMahon BK; Neil ER; Pal R; Parker D; Walton JW; Zwier JM EuroTracker® dyes: design, synthesis, structure and photophysical properties of very bright europium complexes and their use in bioassays and cellular optical imaging. Dalton Trans 2015, 44 (11), 4791–4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Butler SJ; Lamarque L; Pal R; Parker D EuroTracker dyes: highly emissive europium complexes as alternative organelle stains for live cell imaging. Chem. Sci 2014, 5 (5), 1750–1756. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Walton JW; Bourdolle A; Butler SJ; Soulie M; Delbianco M; McMahon BK; Pal R; Puschmann H; Zwier JM; Lamarque L; Maury O; Andraud C; Parker D Very bright europium complexes that stain cellular mitochondria. Chem. Commun 2013, 49 (16), 1600–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Junker AKR; Hill LR; Thompson AL; Faulkner S; Sørensen TJ Shining light on the antenna chromophore in lanthanide based dyes. Dalton Trans 2018, 47 (14), 4794–4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jauregui M; Perry WS; Allain C; Vidler LR; Willis MC; Kenwright AM; Snaith JS; Stasiuk GJ; Lowe MP; Faulkner S Changing the local coordination environment in mono and bi-nuclear lanthanide complexes through “click” chemistry. Dalton Trans 2009, No. 32, 6283–6285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Faulkner S; Pope SJ; Burton-Pye BP Lanthanide complexes for luminescence imaging applications. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev 2005, 40 (1), 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bui AT; Roux A; Grichine A; Duperray A; Andraud C; Maury O Twisted Charge-Transfer Antennae for Ultra-Bright Terbium (III) and Dysprosium (III) Bioprobes. Chem. - Eur. J 2018, 24 (14), 3408–3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hamon N; Galland M; Le Fur M; Roux A; Duperray A; Grichine A; Andraud C; Le Guennic B; Beyler M; Maury O; et al. Combining a pyclen framework with conjugated antenna for the design of europium and samarium luminescent bioprobes. Chem. Commun 2018, 54 (48), 6173–6176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Liao Z; Tropiano M; Mantulnikovs K; Faulkner S; Vosch T; Just Sørensen T Spectrally resolved confocal microscopy using lanthanide centred near-IR emission. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (12), 2372–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Junker AKR; Sørensen TJ Shining light on the excited state energy cascade in kinetically inert Ln (iii) complexes of a coumarin-appended DO3A ligand. Dalton Trans 2019, 48 (3), 964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kovacs D; Phipps D; Orthaber A; Borbas KE Highly luminescent lanthanide complexes sensitised by tertiary amide-linked carbostyril antennae. Dalton Trans 2018, 47 (31), 10702–10714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Parker D; Dickins RS; Puschmann H; Crossland C; Howard JAK Being Excited by Lanthanide Coordination Complexes: Aqua Species, Chirality, Excited-State Chemistry, and Exchange Dynamics. Chem. Rev 2002, 102 (6), 1977–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Andres J; Borbas KE Expanding the Versatility of Dipicolinate-Based Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes: A Fast Method for Antenna Testing. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54 (17), 8174–8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).De Sa G; Malta O; de Mello Donegá C; Simas A; Longo R; Santa-Cruz P; da Silva E Jr Spectroscopic properties and design of highly luminescent lanthanide coordination complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev 2000, 196 (1), 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Cosby AG; Ahn SH; Boros E Cherenkov Radiation-Mediated In Situ Excitation of Discrete Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57 (47), 15496–15499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bernhard Y; Collin B; Decréau RA Inter/intramolecular Cherenkov radiation energy transfer (CRET) from a fluorophore with a built-in radionuclide. Chem. Commun 2014, 50 (51), 6711–6713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Dothager RS; Goiffon RJ; Jackson E; Harpstrite S; Piwnica-Worms D Cerenkov radiation energy transfer (CRET) imaging: a novel method for optical imaging of PET isotopes in biological systems. PLoS One 2010, 5 (10), No. e13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ruggiero A; Holland JP; Lewis JS; Grimm J Cerenkov luminescence imaging of medical isotopes. J. Nucl. Med 2010, 51 (7), 1123–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Supkowski RM; Horrocks WD Displacement of inner-sphere water molecules from Eu3+ analogues of Gd3+ MRI contrast agents by carbonate and phosphate anions: dissociation constants from luminescence data in the rapid-exchange limit. Inorg. Chem 1999, 38 (24), 5616–5619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Soulié M; Latzko F; Bourrier E; Placide V; Butler SJ; Pal R; Walton JW; Baldeck PL; Le Guennic B; Andraud C; et al. Comparative Analysis of Conjugated Alkynyl Chromophore–Triazacyclononane Ligands for Sensitized Emission of Europium and Terbium. Chem. - Eur. J 2014, 20 (28), 8636–8646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Beeby A; Faulkner S; Parker D; Williams JG Sensitised luminescence from phenanthridine appended lanthanide complexes: analysis of triplet mediated energy transfer processes in terbium, europium and neodymium complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2001, 8, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Liu Z; He W; Guo Z Metal coordination in photo-luminescent sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42 (4), 1568–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Junker AKR; Sørensen TJ Illuminating the Intermolecular vs. Intramolecular Excited State Energy Transfer Quenching by Europium (III) Ions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2019, 2019 (9), 1201–1206. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Regueiro-Figueroa M. n.; Bensenane B; Ruscsák E; Esteban-Gómez D; Charbonnière L. c. J.; Tircsó G; Tóth I; Blas A. s. d.; Rodríguez-Blas T; Platas-Iglesias C Lanthanide dota-like complexes containing a picolinate pendant: structural entry for the design of LnIII-based luminescent probes. Inorg. Chem 2011, 50 (9), 4125–4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).O’Malley WI; Abdelkader EH; Aulsebrook ML; Rubbiani R; Loh C-T; Grace MR; Spiccia L; Gasser G; Otting G; Tuck KL; Graham B Luminescent Alkyne-Bearing Terbium(III) Complexes and Their Application to Bioorthogonal Protein Labeling. Inorg. Chem 2016, 55 (4), 1674–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Horrocks WD; Sudnick DR Lanthanide ion luminescence probes of the structure of biological macromolecules. Acc. Chem. Res 1981, 14 (12), 384–392. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Beeby A; Clarkson IM; Dickins RS; Faulkner S; Parker D; Royle L; de Sousa AS; Williams JAG; Woods M Nonradiative deactivation of the excited states of europium, terbium and ytterbium complexes by proximate energy-matched OH, NH and CH oscillators: an improved luminescence method for establishing solution hydration states. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 2, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Chauvin AS; Gumy F; Imbert D; Bünzli JCG Europium and terbium tris (dipicolinates) as secondary standards for quantum yield determination. Spectrosc. Lett 2004, 37 (5), 517–532. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Brouwer AM Standards for photoluminescence quantum yield measurements in solution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem 2011, 83 (12), 2213–2228. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Würth C; Grabolle M; Pauli J; Spieles M; Resch-Genger U Relative and absolute determination of fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples. Nat. Protoc 2013, 8, 1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Rodríguez-Rodríguez A; Esteban-Gómez D; De Blas A; Rodríguez-Blas T; Fekete M; Botta M; Tripier R. l.; Platas-Iglesias C Lanthanide (III) complexes with ligands derived from a cyclen framework containing pyridinecarboxylate pendants. The effect of steric hindrance on the hydration number. Inorg. Chem 2012, 51(4), 2509–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Parker D; Williams JG Getting excited about lanthanide complexation chemistry. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 1996, 18, 3613–3628. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lazarides T; Sykes D; Faulkner S; Barbieri A; Ward MD On the Mechanism of d–f Energy Transfer in RuII/LnIII and OsII/LnIII Dyads: Dexter-Type Energy Transfer Over a Distance of 20 Å. Chem. - Eur. J 2008, 14 (30), 9389–9399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.