Summary

Despite encouraging clinical results with immune checkpoint inhibitors and other types of immunotherapies, the rate of failure is still very high. The development of proper animal models which could be applied to the screening of effective preclinical antitumor drugs targeting human tumor antigens, such as mesothelin, is a great need. Mesothelin (MSLN) is a 40 kDa cell-surface glycoprotein which is highly expressed in a variety of human cancers, and has great value as a target for antibody-based therapies. The present study reports the establishment of an immunocompetent transgenic mouse expressing human MSLN (hMSLN) only in thyroid gland by utilizing an expression vector containing a thyroid peroxidase (TPO) promoter. These mice do not reject genetically modified tumor cells expressing hMSLN on the cell membrane, and tolerate high doses of hMSLN-targeted immunotoxin. Employing this TPO-MSLN mouse model, we find that combination treatment of LMB-100 and anti-CTLA-4 induces complete tumor regression in 91% of the mice burdened with 66C14-M tumor cells. The combination therapy provides a significant survival benefit compared with both LMB-100 and anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy. In addition, The cured mice reject tumor cells when rechallenged, indicating the development of long-term antitumor immunity. This novel TPO-MSLN mouse model can serve as an important animal tool to better predict tumor responses to any immunomodulatory therapies that target MSLN.

Keywords: TPO-MSLN mouse model, Mesothelin, Immunotoxins, Checkpoint modulators, Immunotherapy

One of the advantages of cancer immunotherapy over traditional chemo/radiotherapies is that the former reshapes the conditions in which the immune system targets cancer cells and has the potential to enable durable and complete tumor regression. However, despite strong preclinical effects in animal studies, over 80% of promising monoclonal antibody-based therapies fail to work in patients.1,2

The vast discrepancy between preclinical animal experiments and clinical trials may be due to the numerous intrinsic differences of animal models with humans. Traditionally, anticancer studies use immunodeficient mice to establish tumor models with human gene expression, and this greatly limits studies of tumor immunology and immunotherapy.3 Immunocompetent syngeneic mouse models allow exploration of the interactions between tumor cells and a fully competent immune system, however the major drawback is absence of human targets.4, 5 To overcome these challenges, the establishment of an animal model that maintains immune competence and allows tumor cells expressing human proteins to grow is needed. Such models should be more efficient in screening antibody-based drugs for clinical trials.

Mesothelin (MSLN) is a 40 kDa tumor-differentiation antigen, which is highly expressed in a variety of human cancers, including lung adenocarcinomas, malignant mesothelioma, ovarian, pancreatic, stomach, and colon cancers and pediatric acute myeloid leukemia.6–14 Under normal conditions, this cell-surface glycoprotein is only expressed in nonvital mesothelial cells, and this makes it an attractive target for cancer immunotherapy.15 In patients with triple negative breast cancer, higher expression of MSLN has been correlated with poorer prognosis.13,16 The overexpression of MSLN in lung adenocarcinoma is reported to be a marker of tumor aggressiveness and is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and overall survival.17 Since MSLN was described by our lab in the 1990s, different MSLN targeting immunotherapies have been developed, which include but are not limited to anti-MSLN immunotoxins,18,21 antibody-drug conjugate (ADC),22,23 chimeric monoclonal antibody,24 vaccine25,26 and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy.27,28 Some of these have been evaluated in clinical trials.6,15

The majority of studies utilized established tumor models with human MSLN (hMSLN) expression in immunocompromised mice,17,29–31 which preclude study of interactions of the tumor with an intact host immune system. In addition, the differences in MSLN expression patterns between transgenic mice and humans would lead to a poor prediction of toxicity in preclinical models.

To study the role of anti-CTLA-4 in the anti-tumor activity of recombinant immunotoxins, we previously generated a BALB/c transgenic mouse expressing the full-length hMSLN gene under a CAG promoter and showed CTLA-4 blockade in combination with anti-MSLN immunotoxin injected locally into tumors synergistically eradicated murine cancer by promoting anticancer immunity.32 However, the transgenic mice we used in that study were found to express hMSLN transgene in some vital organs, like pancreas, where MSLN is not expressed in wild-type mice or humans.32 This limited our ability to test systemically administered therapeutic doses of immunotoxin to these mice. We found that most mice died when given 3 IV doses of 50 μg of LMB-100 but none of the non-transgenic mice were killed by this dose. To overcome this hurdle, we generated a transgenic mouse expressing hMSLN only in thyroid gland by utilizing an expression vector containing a thyroid peroxidase (TPO) promoter33 and tested these mice using the combination therapy of an immunotoxin with checkpoint inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Establishment of BALB/c Transgenic Mice Expressing hMSLN Under TPO-MSLN

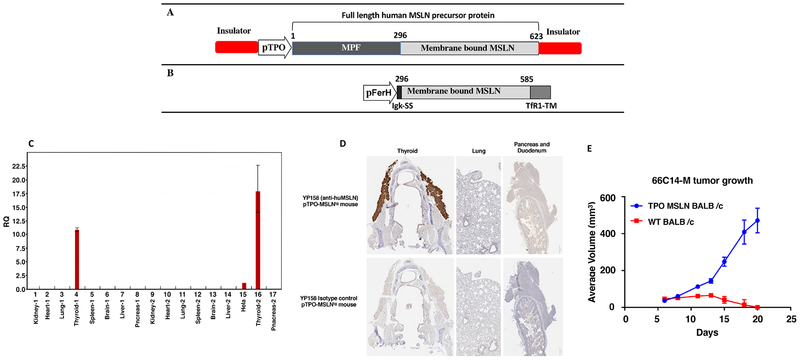

To establish transgenic mice expressing hMSLN under TPO promoter, a cDNA that consists of a full-length MSLN cDNA (Accession Number: NM_005823) under the control of a TPO promoter was produced. The pro-nuclei of fertilized oocytes from WT BALB/c mice were microinjected with a plasmid DNA containing full-length hMSLN precursor sequence under a TPO promoter (Fig. 1A). Founder lines carrying hMSLN transgene were identified by Southern blot analysis. A mouse line with expression of hMSLN transgene was further characterized by qRT-PCR and IHC analysis.

Figure 1.

Generation and characterization of TPO-MSLN transgenic mouse. A. Diagram for the plasmid construct used to generate MSLN BALB/c mice. B. Diagram for the plasmid construct used to generate 66C14-M cancer cell line. C. qRT-PCR analysis of various tissues from TPO-MSLN transgenic mice. MSLN is selectively expressed in thyroid gland of the transgenic mouse. D. Immnohistological staining for hMSLN in tissues from TPO-MSLN mice. E. Growth of 66C14-M cells in BALB/c TPO-MSLN transgenic mice. BALB/c (n=4) and TPO-MSLN-Tg mice were inoculated with 1 × 106 66C14-M cells at their right breast pad; average tumor growth curves show tumors grow in TPO-MSLN mice but were rejected in WT BALB/c mice.

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

The 66Cl4 luc tumor cell line was provided by Dr. C. L. Jorcyk (Boise State University, Boise, ID). The cell line 66Cl4 luc-M expressing a chimeric human mesothelin (Fig 1B) was described in an earlier publication.34 Tumor cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with L-glutamine, HEPES (Gibco Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA), 10% FBS (HyClone, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. For 66Cl4-M cells, 3 mg/mL puromycin (Gibco Life Technology) was added to maintain MSLN expression.32

Cytotoxicity Assay

hMSLN-targeted immunotoxin LMB-10034 and inactivated LMB-100 (LMB-100-I) were manufactured by Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Immunotoxin LMB-92 (BM306-Fab-LO10R) targeting B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) was produced in our laboratory [T.K. Bera and I. Pastan, unpublished data]. 66C14-M cells were seeded at 5000 cells/well in 96-well plates and cultured overnight. The medium was replaced with fresh medium containing different concentrations of LMB-100, LMB-100-I or LMB-92 the next day. Normal medium and medium with 0.1 mg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were respectively used as the blank and positive controls. Cells were incubated for another 3 days before the viability was assessed by the WST-8 cell counting kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan).

Mouse Experiments

All mouse experiments were approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol number: LMB-014). 0.5×106 66C14-M tumor cells expressing hMSLN were injected into the peritoneal cavity (IP) of BALB/c TPO-MSLN female mice (6–14 weeks) on day 1. Dosage information and administration route of each treatment with different immunotoxins or checkpoint modulators are listed in the figure legends. Generally, the treatment started with the administration of immunotoxin (e.g. LMB-100, LMB-100-I or LMB-92) followed by a checkpoint modulator anti-CTLA-4 (Clone 9D9, Absolute Antibody, Oxford). Each control group was treated with either PBS or LMB-100 buffer (Roche). Tumor formation was measured by detecting the luminescence signal acquired from an IVIS system (IVIS® Lumina Series III, Perkin Elmer, location?) twice a week starting from day 4. For IVIS imaging, mice were injected IP with 100 μl luciferase (15mg/ml; VivoGlo™ Luciferin, Promega, Madison, WI) and were anesthetized by isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL). The luminescent images were acquired 10 minutes later. All images were analyzed by Living Image software (Perkin Elmer. Waltham, MA). Mice that did not develop a luciferase signal were excluded from the study. Luminescent intensity (LI) of photons emitted from tumor in each mouse was quantified. Mice weights were monitored 3 times per week. Mice were euthanized if they lost 15% of their original weight, or become hypoactive/hypothermic, or had luminescent intensities (LI) that were higher than 1×1010. All mice were followed for at least 2 months. The day of euthanasia was used to calculate survival.

For the rechallenge experiment, cured mice were injected IP with either 66C14 or 66C14-M cells (0.5×106) 2 months after the first tumor inoculation and about 45 days after the mice achieved complete remission. Normal TPO-MSLN mice inoculated with a simililar number of specific tumor cells were used as a control.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses and graphing were performed with Graphpad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to compare survival of mice. Parametric analysis was carried out by using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by a Tukey post-hoc multiple comparisons. Non-parametric analysis was performed by using Mann-Whitney U-test with Bonferroni correction. The critical value was set at α=0.05.

RESULTS

TPO-MSLN Transgenic Mice with Selective Expression of Transgene in Thyroid Gland

To express hMSLN in mice, a cDNA was produced that consisted of full-length MSLN (Accession Number: NM_005823) under the control of TPO promoter.33 Pronuclear fertilized oocytes of WT BALB/c mice were microinjected with the plasmid DNA containing full-length hMSLN precursor sequence (Fig. 1A). The progeny mice were screened by Southern blot analysis and the positive mice were set aside for mating to get a founder line with germline transmission. The founder line with positive germline transmission was maintained for three generations to ensure stable transgene integration and then tested for MSLN expression by qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. As shown in Figure 1C, the MSLN transgene is selectively expressed in the thyroid gland of a transgenic mouse and there is no detectable expression of MSLN in other tissues indicating that the transgene expression is tightly control by the TPO promoter. We also tested the MSLN expression by immunohistochemistry to validate the RNA expression analysis. As shown in Figure 1D, intense specific staining is observed with anti-hMSLN antibody (YP158) in thyroid follicular cells within the thyroid gland of the TPO-transgenic mice. There is minimal background staining observed with isotype control antibody in other tissues validating the expression is thyroid gland specific.

Syngeneic Tumor Model with 66C14-M Cells in TPO-MSLN Mice

To determine whether 66C14-M cells can form tumors in the TPO-MSLN mice, one million cells were implanted in the right breast pad of four TPO-MSLN mice and four WT BALB/c mice as a control. As shown in Figure 1E, 66C14-M cells formed tumors in all TPO-transgenic mice and continued to grow with time. Tumors also formed in WT BALB/c mice after injection, however tumor signal was only detectable for a few days and had disappeared completely in all four mice 20 days after cell injection. This result indicates that TPO-MSLN mice tolerate transgene expressing tumor cells.

Evalution of Antitumor Efficacy of LMB-100 in TPO-MSLN Mice

To establish a safe dose of immunotoxin that can be given to these mice, we administered five doses of 3 mg/kg LMB-100 QOD by either IP or IV injection. As shown in Supplemental Figure S1, (Supplemental Digital Content 1) all three mice in both treatment group tolerated the dose with minimum weight loss during treatment and recovered completely after the treatment was stopped.

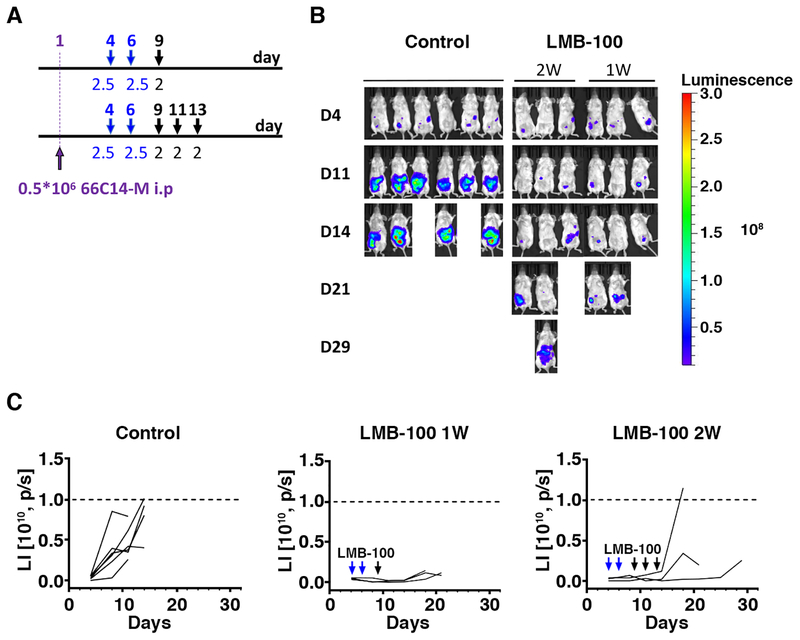

The TPO-MSLN murine model was then used to determine the antitumor efficacy of anti-MSLN immunotoxins. The treatment scheme is shown in Figure 2A. Mice bearing 66C14-M tumors were treated with LMB-100 alone (2–2.5mg/kg, 1–2 weeks) or with dilution buffer administered IP. As shown in Figure 2B and 2C, the tumor burden measured by LI at D11 in mice treated with LMB-100 was significantly lower than that in mice treated with dilution buffer (P<0.01) but none of the mice from either treatment group achieved complete remission (CR) indicating LMB-100 as a single agent has modest activity in this model. In addition, it appears that 2W LMB-100 treated mice have a higher tumor signal but longer survive time than mice with only 1W treatment, but these differences were statistically not significant.

Figure 2.

Antitumor activity of LMB-100 in a xenograft model using TPO-MSLN transgenic mice. A. Treatment scheme of the experiment. Mice were inoculated IP with 0.5 × 106 66C14-M tumor cell at day 1 and were treated IP with 2–2.5 mg/kg LMB-100. Days of injections were marked by arrows. B. Tumor growth as indicated by luminescence images after treatment with either IP 2–2.5 mg/kg LMB-100 for either one week (days 4, 6 and 9, n=3) or two weeks (days 4, 6, 9, 11 and 13, n=3). Control mice were treated with PBS (n=5); C. Tumor growth in individual mouse as measured by luminescence intensity (LI) changes over the course of treatment and observation.

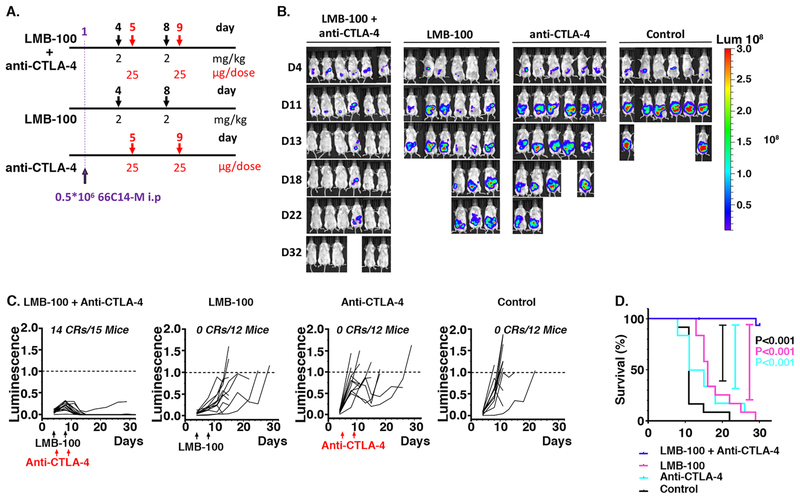

Combination of LMB-100 and Anti-CTLA-4 Causes Complete Tumor Regression

To test whether checkpoint modulators could synergize with LMB-100 to induce better antitumor effects, the combination therapy of anti-CTLA-4 and LMB-100 was tested in the 66C14-M TPO-MSLN mouse model. LMB-100 (2mg/kg) was injected IP in tumor bearing mice at days 4 and 8 post-tumor inoculation and 1 day after LMB-100 treatment, anti–CTLA-4 (IgG2a, 25μg/dose) was injected IP (days 5 and 9). The treatment scheme is shown in Figure 3A. All mice treated with placebo and mice treated with a monotherapy (either LMB-100 or anti-CTLA-4) reached their experimental endpoint before day 29 (Fig. 3B). The combination treatment induced robust tumor regression and durable cures in mice bearing 66C14-M tumors. Fourteen out of 15 (93%) mice achieved tumor CR in “LMB-100 + anti-CTLA-4” group within 11 days post-treatment (Fig. 3C). The tumors, which achieved CR, did not relapse within 60 days. As indicated in Supplemental Figure S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 2), the body weights of mice receiving combination treatment were decreased immediately after two rounds of combination treatment at day 11, but then recovered with cessation of the treatment. The 60 day survival rate of mice receiving combination treatment was significantly higher than mice receiving either LMB-100 or anti-CTLA4 monotherapy (P<0.0001, P<0.0001), as shown in Figure 3D.

Figure 3.

Antitumor effect of the combination therapy with LMB-100 and anti–CTLA-4. A. Treatment scheme of the experiment. B. Tumor growth as indicated by luminescence images after treatment with either IP 2 mg/kg LMB-100 (days 4 and 8, n=12) or IP 25 μg/dose anti-CTLA-4 (days 5 and 9, n=12) or both (n=15). Control mice were treated with PBS (n=12); C. Individual bioluminescence intensities of mice in different treatment groups over the course of the treatment and observation (p/s/cm2/sr). Arrows mark the days of injection. The number of mice in complete remission and total mice per group are listed on each graph. D. Long-term survival of mice is described in A-C, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test showed statistical significance ****p < 0.0001.

Cured Mice from the Combination Therapy Reject the Rechallenged Tumor Cells

To investigate whether combination treatment generated long-term antitumor immunity, mice cured by combination treatment were then inoculated with either 66C14-M or 66C14 cells about 45 days after they achieved complete regressions. As indicated in Figure 4, mice with CR rejected tumor cells in the rechallenge experiment, indicating development of effective immunological antitumor memory. Most importantly, both 66C14-M (Fig. 4B) and 66C14 (Fig. 4C) cells were rejected in the rechallenge assay, indicating the induced antitumor immunity was against shared tumor antigens on 66C14 cells.

Figure 4.

Re-challenge experiment. A. Experimental scheme, cured mice were re-challenged with IP 0.5×106 66C14 cells 60 days from the first tumor inoculation or with IP 0.5×106 66C14-M cells 62 days from the first tumor inoculation; B. Tumor burden of 66C14-M challenged mice measured by luminescence intensity over the course of observation; C. Cured mice were re-challenged with IP 0.5×106 66C14 60 days from the first tumor inoculation; tumor burden measured by luminescence intensity over the course of the treatment and observation.

Active MSLN Targeted Toxin is Needed for the Effective Combination Treatment with Anti-CTLA-4

To determine whether MSLN-targeted cell killing of LMB-100 was required for generating tumor CR through the synergy with anti-CTLA-4, we repeated the antitumor experiment with LMB-100-I and LMB-92. LMB-100-I is an inactive form of LMB-100 that lacks glutamic acid in position 553 and the furin cleavage site is replaced with a glycine-serine linker.34 LMB-92 is an immunotoxin designed with the same toxin moiety (LO10R) as LMB-100, but targets human BCMA, which is not expressed on mouse 66C14-M cells. As shown in Supplemental Figure S3 (Supplemental Digital Content 3), The IC50 of LMB-100 to 66C14-M is 19 ng/ml, whereas the IC50 of LMB-92 and LMB-100-I are >1000 ng/ml.

We combined either LMB-92 (2mg/kg IP, days 4 and 8) or LMB-100-I (2mg/kg, IP, days 4 and 8) with anti-CTLA-4 (25μg/dose, IP, days 5 and 9) to treat 66C14-M tumor bearing mice.

As shown in Table 1, only one out of eight mice in the “LMB-92 + anti-CTLA-4” group and one out of seven mice in the “LMB-100-I + anti-CTLA-4” group reached CR. This CR rate is much lower than the combined treatment with “LMB-100 + anti-CTLA-4” (20 CRs/22 Mice). The survival rate of mice in “LMB-100 + anti-CTLA-4” group was significantly higher than in “LMB-100-I + anti-CTLA-4” and “LMB-92 + anti-CTLA-4” groups (PLMB-100-I<0.05, PLMB-92<0.0001), indicating both tumor cell targeting and killing by immunotoxin are required for the synergestic activity of anti-CTLA-4 in generating antitumor immunity.

Table 1.

Summary of mice that reach CR in each experiment

| Treatment | Mice reach CR | Total Mice |

|---|---|---|

| 2mg/kg LMB-100 | 0 | 12 |

| 25μg/dose anti-CTLA-4 | 3 | 19 |

| 2mg/kg LMB-100 + 25μg/dose anti-CTLA-4 | 20 | 22 |

| 2mg/kg LMB-100-I + 25μg/dose anti-CTLA-4 | 1 | 7 |

| 2mg/kg LMB-92 + 25μg/dose anti-CTLA-4 | 1 | 8 |

In summary, we found the total survival rate in the “LMB-100 + anti-CTLA-4” combination treatment group was much higher than in the control groups.

DISCUSSION

The present study describes a new transgenic BALB/c mouse model with hMSLN selectively expressed in the thyroid gland, making it tolerant to high doses of hMSLN-targeted anticancer therapies. LMB-100 targets human mesothelin but does not react with mouse mesothelin. To enable us to test LMB-100 in mice we needed to transfect mouse breast cancer cell line 66Cl4-luc with human mesothelin, but these cells would not grow in mice with a normal immune system, because human mesothelin is foreign to mice and the tumors are rejected. To make mice tolerant to human mesothelin we chose to express human mesothelin in the thyroid gland, which if damaged, would result in hypothyroidism that can be treated with thyroid hormone. We found that LMB-100 treatment did not affect thyroid function and did not investigate why. The transgenic mice used in our previous study expressed hMSLN in some vital organs including pancreas that prevented administration of high doses of LMB-100 to those mice35. This TPO-MSLN mouse strain has an intact immune system, but it will not reject genetically modified tumor cells with hMSLN expression on the cell membrane. These features make a good model to test novel immunotherapies targeting MSLN.

A mouse breast cancer cell line (66C14) of BALB/c origin that expresses hMSLN showed high tumorgenicity when cells were inoculated IP into the TPO-MSLN transgenic mice. The administration of a MSLN-targeted immunotoxin, LMB-100, at a dose as high as 3 mg/kg, either though IP or IV (Supplemental Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1), was well tolerated; whereas in our previous model a therapeutic dose of immunotoxin could only be reached by administering them through intratumoral injection.35

Traditionally, the antitumor effects of immunotoxin were believed to be realized by suppressing protein synthesis after immunotoxin internalization into the target cells. Since most of our previous studies on immunotoxin were conducted in immune deficient mice, the regulatory roles of immune system on immunotoxin-mediated antitumor activity were not appreciated. In an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, T cells present an exhausted phenotype as a result of exposure to high level checkpoint modulating signals, such as CTLA-4 and PD-1. This could be one of the factors that inhibit the activity of immunotoxin monotherapy to generate sufficient antitumor effect in the treatment of solid tumors. Similarly, despite the clinical success of checkpoint inhibitor (e.g. anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1) monotherapies, only a small proportion of patients could benefit from this therapy. One of the reasons may be the insufficient immunogenic cell death to expose enough antigens for cross-priming of cytotoxic T cells. Combining immunotoxin treatment together with removing checkpoint suppression may be potentially useful in generating sufficient immunogenic cell death to augment the antitumor efficiency in immune therapies.32,35

By employing our newly established transgenic BALB/c mouse, we were able to evaluate whether immunotoxin treatment would have additional antitumor activity by affecting the immune system. Our results showed that over 90% of mice achieved complete tumor rejection after a combination treatment of LMB-100 and anti-CTLA-4 and 100% of the long-term survivors rejected tumors after rechallenging with the same cells. However, monotherapy of either LMB-100 or anti-CTLA-4 only generate 0% or 16% tumor CR, respectively. We further confirmed that both tumor cell targeting and cell killing by immunotoxin are required in the antitumor activity in vivo. A possible hypothesis is that cell killing by LMB-100 increases presentation of tumor antigens and thus primes tumors to CTLA-4 blockade.

To summarize, we report here the development of an immunocompetent transgenic mouse model with selective expression of hMSLN in thyroid gland. This TPO-MSLN mouse has a good tolerance to genetically modified breast cancer cells that express hMSLN. Since hMSLN is not expressed in vital organs (like heart) of this mouse model, the safe dose of hMSLN-targeted immunotoxin (LMB-100) was greatly increased to a value as high as 3 mg/kg dose when compared with our previous MSLN transgenic mouse model, making it a promising animal tool in testing novel hMSLN-targeted anticancer immune therapies. By employing this TPO-MSLN mouse model that bears 66C14-M tumor with hMSLN expression, we found an enhanced immunogenic antitumor effect of a combination treatment with LMB-100 together with anti-CTLA-4 (with tumor CR rate as high as 91%). We suggest that this TPO-MSLN mouse model serves as an important preclinical animal tool to better guide the development of novel antitumor immune therapies.

Supplementary Material

Toxicity of LMB-100 in TPO-MSLN Mice. Individual body weight change over the course of treatment with 60 μg/dose LMB-100 in mice without tumor inoculation, the LMB-100 was administrated IP or IV.

Individual body weight of mice from the combination therapy of LMB-100 and anti–CTLA-4 or control groups.

WST-8 cytotoxicity assays in 66C14-M cells after 3 day incubation with either LMB-100, LMB-100-I or LMB-92.

Support:

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (Project ZO1 BC008753)

Footnotes

References

- 1.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, et al. , Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrowsmith J, Miller P. Trial watch: phase II and phase III attrition rates 2011–2012. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton CL, Houghton PJ. Establishment of human tumor xenografts in immunodeficient mice. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldin A, Venditti JM, Kline I, et al. Evaluation of antileukemic agents employing advanced leukemia L1210 in mice. II. Cancer Res. 1960;20:382–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suggitt M, Bibby MC. 50 years of preclinical anticancer drug screening: empirical to target-driven approaches. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:971–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastan I, Hassan R. Discovery of mesothelin and exploiting it as a target for immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2014:74:2907–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morello A, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Mesothelin-targeted CARs: driving T cells to solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordonez NG. Application of mesothelin immunostaining in tumor diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang K, Pai LH, Pass H, et al. Monoclonal antibody K1 reacts with epithelial mesothelioma but not with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan R, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I, et al. Localization of mesothelin in epithelial ovarian cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005;13:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Ryu B, et al. Mesothelin is overexpressed in the vast majority of ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas: Identification of a new pancreatic cancer marker by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE). Clin Cancer Res 2001;7: 3862–3868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan R, Laszik ZG, Lerner M, et al. Mesothelin is overexpressed in pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinomas but not in normal pancreas and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;124:838–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tozbikian G, Brogi E, Kadota K, et al. Mesothelin expression in triple negative breast carcinomas correlates significantly with basal-like phenotype, distant metastases and decreased survival. Plos One. 2014;9:e114900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinbach D, Onda M, Voigt A, et al. Mesothelin, a possible target for immunotherapy, is expressed in primary AML cells. Eur J Haematol 2007;79:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan R, Thomas A, Alewine C, et al. Mesothelin immunotherapy for cancer: ready for prime time? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4171–4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YR, Xian RR, Ziober A, et al. Mesothelin expression is associated with poor outcomes in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147:675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kachala SS, Bograd AJ, Villena-Vargas J, et al. Mesothelin overexpression is a marker of tumor aggressiveness and is associated with reduced recurrence-free and overall survival in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1020–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chowdhury PS, Viner JL, Beers R, et al. Isolation of a high-affinity stable single-chain Fv specific for mesothelin from DNA-immunized mice by phage display and construction of a recombinant immunotoxin with anti-tumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:669–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chowdhury PS, Pastan I. Improving antibody affinity by mimicking somatic hypermutation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollevoet K, Mason-Osann E, Liu XF, et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of the low-immunogenic antimesothelin immunotoxin RG7787 in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2040–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassan R, Alewine C, Pastan I. New life for immunotoxin cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res 2016;22:1055–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagemann UB, Hagelin EM, Wickstroem K, et al. A novel high energy alpha pharmaceutical: In vitro and in vivo potency of a mesothelin-targeted thorium-227 conjugate (TTC) in a model of bone disease. Cancer Res. 2016;76(Suppl 14). Abstract 591. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weekes CD, Lamberts LE, Borad MJ, et al. Phase I study of DMOT4039A, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting mesothelin, in patients with unresectable pancreatic or platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regino C, Sato N, Shin IS, et al. , A preclinical evaluation of mesothelin-specific tumor imaging using 111In-CHX-A “-MORAb-009, a chimeric monoclonal antibody. J Nucl Med. (Mtg Abstract) 2010;51: (Suppl 2) 416. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaffee EM, Hruban RH, Biedrzycki B, et al. Novel allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic cancer: A phase I trial of safety and immune activation. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas AM, Santarsiero LM, Lutz ER. et al. Mesothelin-specific CD8(+) T cell responses provide evidence of in vivo cross-priming by antigen-presenting cells in vaccinated pancreatic cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2004;200:297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adusumilli PS, Zauderer M, Rusch V, et al. A phase I clinical trial of malignant pleural disease treated with regionally delivered autologous mesothelin-targeted CAR T cells: safety and efficacy - a preliminary report. Mol Ther. (Mtg Abstract) 2018;26:158–159. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morello A, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Mesothelin-targeted CARs: driving T cells to solid tumors. Cancer Discov 2016;6:133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M, Bharadwai U, Zhang R, et al. Mesothelin is a malignant factor and therapeutic vaccine target for pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:286–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Servais EL, Colovos C, Rodriquez L, et al. , Mesothelin overexpression promotes mesothelioma cell invasion and MMP-9 secretion in an orthotopic mouse model and in epithelioid pleural mesothelioma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2478–2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imamura O, Okada H, Takashima Y, et al. siRNA-mediated Erc gene silencing suppresses tumor growth in Tsc2 mutant renal carcinoma model. Cancer Lett. 2008;268:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leshem Y, King EM, Mazor R, et al. SS1P immunotoxin induces markers of immunogenic cell death and enhances the effect of the CTLA-4 blockade in AE17M mouse mesothelioma tumors. Toxins (Basel), 2018;10, E470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusakabe T, Kawaguchi A, Kawaguchi R, et al. Thyrocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2004;39:212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Douglas CM, Collier RJ. Exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: substitution of glutamic acid 553 with aspartic acid drastically reduces toxicity and enzymatic activity. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4967–4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leshem Y, O’Brien J, Liu X, et al. Combining local immunotoxins targeting mesothelin with CTLA-4 blockade synergistically eradicates murine cancer by promoting anticancer immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Toxicity of LMB-100 in TPO-MSLN Mice. Individual body weight change over the course of treatment with 60 μg/dose LMB-100 in mice without tumor inoculation, the LMB-100 was administrated IP or IV.

Individual body weight of mice from the combination therapy of LMB-100 and anti–CTLA-4 or control groups.

WST-8 cytotoxicity assays in 66C14-M cells after 3 day incubation with either LMB-100, LMB-100-I or LMB-92.