Abstract

The kidneys play an important role in the long-term regulation of blood pressure by control of salt and water balance in the body through various systems including the endocannabinoid system. The endocannabinoid system consists of the two major cannabinoid receptor agonists, anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG), their hydrolyzing enzymes, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), and the cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2. AEA can be converted into 12- and 15(S)-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid ethanolamides by 12-LOX and 15-LOX, respectively and can form epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-(EET-EAs) (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, 14,15- ) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid- (HETE) ethanolamides. Furthermore, the EET-EAs produce a secondary metabolism by microsomal epoxide hydrolase to form the corresponding dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-EAs (DiHETE-EA). Reference material was not available for DiHETE-EA. These metabolites were synthesized by incubation of the corresponding EET-EAs with mouse liver cytosol containing epoxide hydrolases. Presented is a solid phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) for the extraction and quantitation of AEA, 2-AG, their metabolites, Oleoylethanolamide (OEA), and Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), and the in vivo formation of the dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-EAs in kidney after a single intravenous bolus administration of 20 mg/kg of anandamide in C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice.

Keywords: Endocannabinoids, HPLC-MS/MS, mass spectrometry, solid phase extraction, AEA, AEA metabolites

1. Introduction

The endocannabinoid system consists of the two major cannabinoid receptor agonists, anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG), their hydrolyzing enzymes, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), and the cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2. Anandamide (N-arachidonylethanolamine), the N-acyl ethanolamide of arachidonic acid (AA), was first identified in porcine brain [1]. Though AEA concentrations are highest in the brain and liver, the kidney has also been noted for its high concentrations of AEA [2, 3]. AEA exhibits physiological effects such as antinociception, inflammation, and analgesia, however its function in the kidney is still being investigated [4-6]. It has been demonstrated that AEA increases renal blood flow and decreases glomerular filtration rate [7]. Furthermore, methanandamide, a methylated analog of AEA, increased urine volume and decreased mean arterial pressure after intrarenal medullary infusion in anesthetized rats, suggesting that renal AEA can regulate body volume homeostasis and blood pressure [8]. 2-AG has been established as an endogenous, peripheral ligand of the cannabinoid receptors [9]. Its function in the kidney is less characterized but was shown to elicit dose-dependent hypotension when injected intravenously into ICR mice, and a metabolically stable analogue of 2-AG caused prolonged hypotension and bradycardia in ICR mice [10]. The kidney is also unique in its high basal activities of the endocannabinoid metabolizing enzymes FAAH and MAGL. FAAH is a membrane-bound amidase that hydrolyzes AEA to arachidonic acid (AA) and ethanolamine and is known to be the primary enzyme that terminates AEA’s in vivo activity [4, 11]. 2-AG is hydrolyzed by MAGL to form AA and glycerol [12]. The administration of isopropyl dodecyl fluorophosphates (IDFP), a dual inhibitor of FAAH and MAGL, into the renal medulla of mice stimulated diuresis and natriuresis, increased medullary blood flow [13]. The infusion of a selective FAAH inhibitor, PF-3845, into the renal medulla also stimulated diuresis and natriuresis and lowered mean arterial pressure [13, 14]. In addition to hydrolysis, AEA and 2-AG can also be subjected to oxidative metabolism by several fatty acid oxygenases, including COX-2, lipoxygenases (LOX), and cytochrome p450 enzymes. The inducible form of cyclooxygenase, COX-2, is constitutively expressed in the kidney and was demonstrated to metabolize AEA to the N-ethanolamide analogs of prostaglandins, termed prostamides, and also metabolizes 2-AG, followed by prostaglandin synthases, to prostaglandin glycerol esters [15-17]. We have previously shown that infusion of prostamide E2 (PE2) into the mouse renal medulla stimulated urine formation and excretion of sodium and potassium [18].

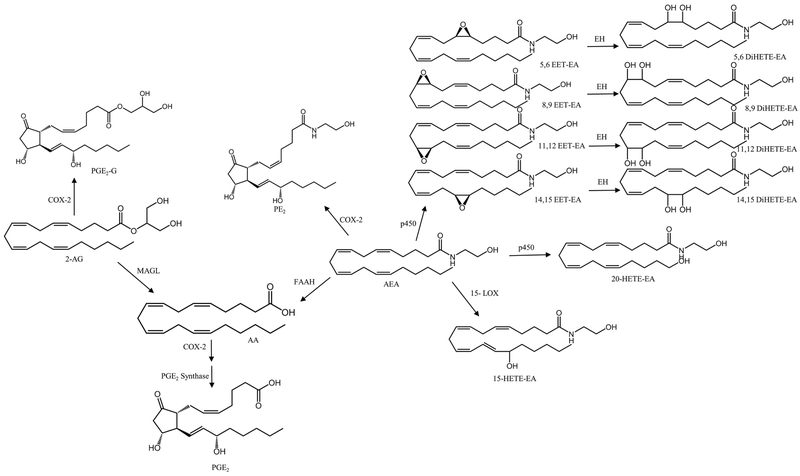

AEA can be converted into 12- and 15(S)-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid ethanolamides by 12-LOX and 15-LOX, respectively [19]. Snider et al demonstrated the metabolism of AEA by cytochrome p450s to form epoxyeicosatrienoic acid- (EET) (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, 14,15- ) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid- (HETE) ethanolamides. Furthermore, the EET-EAs underwent secondary metabolism by microsomal epoxide hydrolase to form the corresponding dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-EAs (DiHETE-EA) [20]. Though the in vivo formation and biological significance of these pathways remains to be determined, anandamide’s metabolism by p450s may provide compounds that contribute to renal hemodynamics. A summary of the metabolism of AEA and 2-AG is shown in Figure 1. Two other AEA-related lipid ethanolamides, palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) and oleoylethanolamide (OEA) also have high concentrations in the kidney. However, their roles and mechanisms of action in the kidney are not fully understood.

Figure 1.

Metabolism of 2-arachidonylglycerol and anandamide.

The development of a sensitive and reproducible method to detect and quantitate physiologic concentrations of the endocannabinoids and their metabolites is important to evaluate their role in the regulation of renal functions. Extraction of endocannabinoids and related lipids widely differ among published analytical methods including liquid-liquid extraction, solid-phase extraction (SPE), magnetic liquid microextraction-chemical derivatization, salting-out assisted liquid-liquid extraction, protein precipitation, and column switching [21, 22]. The two most commonly published sample preparation methods are liquid-liquid extraction and SPE. Liquid-liquid extraction using chloroform/methanol is commonly used, but this method can be time consuming and require large volumes of solvents. In addition, many of these methods are followed by sample clean-up using solid phase extraction. SPE methods often report poor extraction efficiency in complex matrixes, recovery or large solvent volumes that can be difficult to dry down which increases sample preparation time [23-25] . Therefore, an efficient SPE method for the extraction of the lipids is desired.

Since FAAH knockout mice (KO) are known to contain significantly higher concentrations of AEA compared to wild-type mice [2, 26], this study investigated the in vivo formation of the EET-EAs and DiHETE-EAs in C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice. Presented is the in vivo formation of the dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-EAs in kidney after a single intravenous bolus administration of 20 mg/kg of anandamide in C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice. A solid phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) for the extraction and quantitation of AEA, 2-AG and their metabolites AA, PE2, PGE2, PGD2, PGE2-G, 20-HETE-EA, 15-HETE-EA, 5,6-EET-EA, 8,9- EET-EA, 11,12-EET-EA, 14,15- EET-EA and their corresponding DiHETE-EAs was developed and used to analyze mouse kidney tissue specimens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

This study used kindey tissue obtained from 2- to 4-month-old male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and FAAH KO mice (homozygous gene knockout) from a colony maintained at Virginia Commonwealth University on a C57BL/6 background. All mice used in experiments weighed 25-35 g; were housed 4-5 per cage at a temperature of 20-22 °C in a humidity-controlled (50-55%) facility with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle and received ad libitum food and water. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University and were in concordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Reagents

The primary reference materials for AEA, PEA, OEA, PE2, PGE2, PGD2, AA, 2-AG, PGE2-G, 20-HETE-EA, 15-HETE-EA, 5,6-EET-EA, 8,9- EET-EA, 11,12- EET-EA, 14,15- EET-EA and their internal standards (ISTD); AEA-d8, PEA-d4, OEA-d4, PE2-d4, PGE2-d4, PGD2-d4, AA-d8, 2-AG-d5, and PGE2-G-d5 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Acetonitrile, ammonium acetate, ammonium hydroxide, Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), formic acid, ethyl acetate, isopropanol, magnesium chloride (MgCl2), methylene chloride, HPLC grade methanol, potassium chloride (KCl), Tris–HCl Buffer, pH 7.5 and water were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL). Phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF) was obtained from Cayman Chemical. Clean Up® C18 solid phase extraction (SPE) columns were purchased from United Chemical Technologies (Bristol, PA). Medical grade nitrogen was purchased from National Welders Supply Company (Richmond, VA).

2.3. Synthesis of dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-ethanolamides

The DiHETE-EAs metabolites, 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15- dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid ethanolamides, were not commercially available. These metabolites were formed by incubation of the corresponding EET-EAs with mouse liver cytosol containing epoxide hydrolases. Mouse liver cytosol containing epoxide hydrolases was isolated and prepared as previously described [27]. In brief, the mice were deeply anesthetized by 3% isoflurane-containing oxygen and humanely sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The peritoneal cavity was then opened and the liver perfused in situ with cold DPBS. The liver was removed and fat and debris were trimmed away. The collected livers were weighed and 1.12 g to 1.33 g aliquots were homogenized with 8 mL sucrose in a cold homogenization tube fitted with a drill-driven Teflon pestle. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at 8,000 g at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and re-centrifuged for 15 min at 18,500 g. The supernatant was then transferred to an ultracentrifuge tube and centrifuged for 45 min at 205,000 g. The lipid layer was removed and the cytosolic fraction was decanted and saved frozen until use. Using the same principles as a previously published method, the EET-EAs epoxides were enzymatically hydrated to their corresponding dihydroxy metabolites [28]. Briefly, reaction mixtures contained 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), and liver cytosol (0.2 mg/mL) were initiated by addition of 1 μg of the correct EET-EA and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Reaction products and complete conversion of the epoxides were confirmed by analysis by the presented method HPLC-MS/MS method. The expected DiHETE-EAs were detected in the reaction products and the EET-EAs were not detected in any of the reaction products. The formed DiHETE-EAs were used as standards for the method validation. PE2-d4 was used for the internal standard for all EET-EAs and Di-HETE-EAs due to lack of deuterated standards.

2.4. In vivo formation of EET-EAs and DiHETE-EAs from anandamide administration in mouse

C57BL/6J mice and FAAH KO were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of thiobutabarbital (Inactin™, 75 mg/kg, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and ketamine (Ketathesia™, 100 mg/kg, Harry Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH). Animals were placed on surgical table that was thermally controlled at 37 °C. After confirmation of anesthesia by observing negative response to mechanical toe pressing, a tracheotomy was performed to facilitate breathing by inserting polyethylene tubing (PE-60) into the trachea. The left carotid artery was cannulated with PE-10 tubing filled with heparin sodium dissolved in saline (Fisher BioReagents, 0.005 mg/mL, 50 IU/mL) attached to a pressure transducer connected to a data acquisition system (Windaq, DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH) for continuous mean arterial pressure measurement. The right jugular vein was catheterized similarly. After a 1 hr equilibration period, animals received a 20 mg/kg intravenous bolus administration of anandamide in the right jugular vein. Thirty minutes after administration of anandamide mice were euthanized by exsanguination and cervical dislocation. The kidneys were removed and kept at −70 °C until processing. Kidneys from naïve C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice were collected and used as controls.

2.5. Sample Preparation and Extraction

Mouse kidney tissue specimens were weighted and homogenized in 2 mL ice cold methanol containing 1 mM PMSF and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 4000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and diluted to 25% methanol with DI water. A seven point calibration curve at 0.1-10 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 1-100 ng of AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 10-1,000 ng of 2-AG; 100-10,000 ng of AA were prepared in water. 10 μL of ISTD solution that contained 10 ng AEA-d8, PEA-d4, OEA-d4, PGE2-d4, PGD2-d4, 5 ng PE2-d4, PGE2-G-d5, 200 ng 2-AG-d5, and 1000 ng AA-d8 were added to 1.0 mL, quality control (QC) samples including a negative control and a double negative control that did not contain ISTD or 200 mg aliquots of tissue homogenates. Samples were mixed using a vortex mixer for 30 sec. Clean Up® C18 SPE columns were conditioned with 3 mL methanol followed by 3 mL DI water. The samples were added to the columns and aspirated, followed by 3 mL DI water and 2 mL hexane. Columns were dried under vacuum for 5 minutes. All analytes were eluted with 1 mL 78:20:2 dichloromethane:isopropanol:ammonium hydroxide followed by 1 mL ethyl acetate. The eluate was dried under nitrogen, reconstituted in 50 μL of 60:40 water: acetonitrile and transferred to auto-sampler vials for high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) analysis.

2.6. Instrumental Analysis

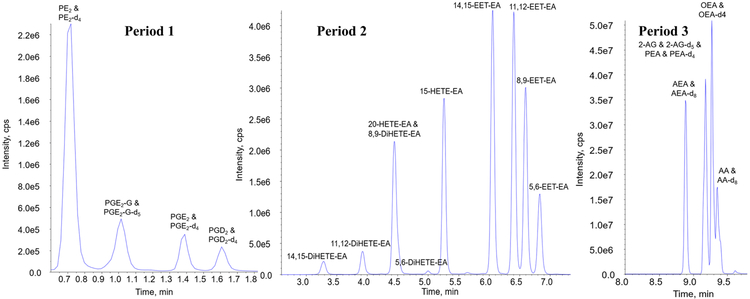

The HPLC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Sciex 6500+ QTRAP system with an IonDrive Turbo V source for TurbolonSpray® (Ontario, Canada) attached to a Shimadzu Nexera X2 UPLC system (Kyoto, Japan) controlled by Analyst software (Ontario, Canada). Chromatographic separation was performed on a Discovery® HS C18 Column 15 cm x 2.1 mm, 3 μm (Supelco: Bellefonte, PA) held at 40°C. The sample injection volume was 10 μL with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of A: water with 1 g/L ammonium acetate and 0.1% formic acid and B: acetonitrile. The mobile phase gradient started with 40% B, at 2.5 to 6.0 minutes the mobile phase increased to 60% B and was held for 2.1 minutes. At 8.1 to 9 minutes the mobile phase increased to 100% B and was held for 3.1 minutes. At 12.1 minutes the mobile phase was return to 40% B. The total run time was 14 minutes. The chromatographic separation of all the analytes is presented in Figure 2. The run was separated into 3 periods to ensure the greatest sensitivity for each analyte. Samples were acquired using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The HPLC-MS/MS parameters for the method including retention times (min), deprotonation potentials (V), transition ions (m/z) and corresponding collision energies (V) for all of the compounds is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

HPLC-MS/MS total ion chromatogram of AEA, 2-AG, their metabolites, OEA, and PEA

Table 1.

HPLC-MS/MS parameters for analytes and internal standards

| Compound | Transition ions (m/z) |

Dwell (msec) |

DP (V) |

CE (V) |

CXP (V) |

Retention time (min) |

Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE2 | 396.2 > 378.2 | 100 | 25 | 8 | 10.5 | 0.72 | 1 |

| 396.2 > 360.2 | 100 | 25 | 13 | 10.5 | 0.72 | ||

| PE2-d4 | 400.2 > 382.2 | 100 | 25 | 9 | 10.5 | 0.71 | |

| 400.2 > 364.2 | 100 | 25 | 13 | 10.5 | 0.71 | ||

| PGE2-G | 444.3 > 409.3 | 100 | 25 | 11 | 10.5 | 1.02 | 1 |

| 444.3 > 391.3 | 100 | 25 | 17 | 10.5 | 1.02 | ||

| PGE2-G-d5 | 449.3 > 396.3 | 100 | 25 | 17 | 10.5 | 1.00 | |

| PGE2 | 351.0 > 271.0 | 100 | −40 | −23 | −6.0 | 1.41 | 1 |

| 351.0 > 315.0 | 100 | −40 | −15 | −6.0 | 1.41 | ||

| PGE2-d4 | 355.0 > 275.0 | 100 | −40 | −22 | −6.0 | 1.38 | |

| 355.0 > 319.0 | 100 | −40 | −15 | −6.0 | 1.38 | ||

| PGD2 | 351.0 > 271.0 | 100 | −40 | −23 | −6.0 | 1.63 | 1 |

| 351.0 > 315.0 | 100 | −40 | −15 | −6.0 | 1.65 | ||

| PGD2-d4 | 355.0 > 275.0 | 100 | −40 | −22 | −6.0 | 1.61 | |

| 355.0 > 319.0 | 100 | −40 | −15 | −6.0 | 1.61 | ||

| 15(S)-HETE-EA | 346.2 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 5.28 | 2 |

| 346.2 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 5.28 | ||

| 20-HETE-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 4.44 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 4.44 | ||

| 5,6-EET-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 6.85 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 6.85 | ||

| 8,9-EET-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 6.65 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 6.65 | ||

| 11,12-EET-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 6.41 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 6.41 | ||

| 14,15-EET-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 6.09 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 6.09 | ||

| 5,6-DiHETE-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 4.99 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 4.99 | ||

| 8,9-DiHETE-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 4.48 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 4.48 | ||

| 11,12-DiHETE-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 3.91 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 3.91 | ||

| 14,15-DiHETE-EA | 364.0 > 62.0 | 100 | 40 | 35 | 10 | 3.28 | 2 |

| 364.0 > 91.0 | 100 | 40 | 38 | 10 | 3.28 | ||

| AA | 303.2 > 259.2 | 20 | −50 | −25 | 10 | 9.37 | 3 |

| 303.2 > 59.1 | 20 | −50 | −60 | 10 | 9.37 | ||

| AA-d8 | 311.2 > 267.2 | 20 | −50 | −25 | 10 | 9.35 | |

| 311.2 > 59.1 | 20 | −50 | −60 | 10 | 9.35 | ||

| AEA | 348.2 > 62.2 | 20 | 26 | 13 | 10 | 9.01 | 3 |

| 348.2 > 91.2 | 20 | 26 | 60 | 10 | 9.01 | ||

| AEA-d8 | 356.2 > 62.2 | 20 | 26 | 13 | 10 | 9.01 | |

| 2-AG | 379.3 > 287.3 | 20 | 60 | 25 | 10 | 9.16 | 3 |

| 378.3 > 269.3 | 20 | 60 | 29 | 10 | 9.16 | ||

| 2-AG-d5 | 384.3 > 287.3 | 20 | 60 | 25 | 10 | 9.16 | |

| 387.3 > 269.4 | 20 | 60 | 29 | 10 | 9.16 | ||

| PEA | 300.0 > 62.0 | 20 | 31 | 28 | 10 | 9.21 | 3 |

| 300.0 > 283.0 | 20 | 31 | 19 | 10 | 9.21 | ||

| PEA-d4 | 304.0 > 62.0 | 20 | 31 | 28 | 10 | 9.20 | |

| OEA | 326.0 > 62.0 | 20 | 40 | 30 | 10 | 9.29 | 3 |

| 326.0 > 309.0 | 20 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 9.29 | ||

| OEA-d4 | 330.0 > 66.0 | 20 | 40 | 30 | 10 | 9.28 |

Deprotonation Potential = DP, Collision Energy = CE, Collision Exit Potential = CXP

3. Method Validation Procedure

The evaluation of the assay was conducted over five days. Sample batches were analyzed as recommended for biomedical assay validation for linearity, lower limit of quantitation (LOQ), bias, precision, carryover, matrix interferences, and ion suppression. Validation sample batches contained calibrators, analyte-free controls (negative control) with internal standard (ISTD) added and a double negative control containing neither the analytes nor the ISTDs. Aliquots of QC samples were analyzed in triplicate each day. QC samples were prepared with the following target values: limit of quantitation quality control (LOQC), 0.1 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 1 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 10 ng for 2-AG; 100 ng for AA ; low control (LQC), 0.3 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 3 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 30 ng for 2-AG; 300 ng of AA; medium control (MQC), 3 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 30 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 300 ng for 2-AG; 3000 ng for AA ; high control (HQC),7.5 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 75 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 750 ng for 2-AG; 7,500 ng for AA. All QC samples were stored at −20 °C until testing.

3.1. Linearity, Limit of Quantitation

Linearity of the assay was verified from seven-point calibration curves prepared in the blank surrogate matrix, water, at the following concentrations: 0.1-10 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 1-100 ng of AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 10-1000 ng of 2-AG; 100-10,000 ng of AA. A linear regression of the ratio of peak area counts of the compound to that of the ISTDs versus corresponding concentration ratios was used to construct the calibration curves. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was administratively set at 0.1 ng of PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs, except 5,6-DiHETE-EA which was set at 0.2 ng; 1 ng of AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 10 ng of 2-AG; 100 ng of AA. LOQC samples were used to verify that the LOQ was within ± 20% of the target value and had a response at least ten times greater than the signal to noise ratio of the blank.

3.2. Accuracy and Precision

Accuracy and precision were determined from the prepared QC samples (LQC, MQC, and HQC). QC samples were analyzed in triplicate each run over five different analytical runs. Accuracy was expressed as a percentage error (RE %) and acceptable bias did not exceed ± 20% at each concentration. Two types of precision were assessed during the validation: intra-day and inter-day. The largest calculated within-run % coefficient of variation (CV) for each concentration over the five validation runs was used to assess intra-day precision. Inter-day precision was calculated for each concentration over the five validation runs by using the combined data from all replicates of each concentration. The coefficient of variation (% CV) was calculated and ensured it did not exceed ± 20% at each concentration.

3.3. Carryover

Sample carryover of all of the compounds was evaluated in each of the five validation batches using two different procedures. First, immediately following the injection of the highest calibrator a negative control (analyte-free) was injected. Second, an injection of HQC was immediately followed by injection of the LQC. This procedure was routinely applied each time the high calibrator, HQC and LQC samples were analyzed. Lack of carryover was confirmed when none of the compounds were detected in the negative control at −25% or less of LOQ and the LQC samples did not demonstrated a quantified bias of more than 20%.

3.4. Matrix Effects and Absolute Recovery

Matrix effects, the percentage of ion suppression or enhancement, and absolute recovery of the assay was determined using the post-extraction addition method. The matrix effects for all the compounds of interest were evaluated in water at the high and low QC concentrations. Matrix effects for the non-endogenous ISTDs were also evaluated in kidney. Water samples in duplicate and ten lots of mouse kidney homogenates were prepared by extracting the matrix by the presented method and then fortifying them with the compound of interest. These post extracted samples along with unextracted samples prepared in triplicate in mobile phase were analyzed. The percentage of ion suppression or enhancement was calculated by taking the average peak areas of the post extracted samples and dividing it by the average peak area of the unextracted samples and multiplying by 100. The absolute recoveries for the for all the compounds of interest were evaluated in water at the high and low QC concentrations. The absolute recoveries for the non-endogenous ISTDs were also evaluated in kidney. Water samples in duplicate and ten lots of mouse kidney homogenates were prepared by fortifying them with the compounds of interest and then extracting the matrix by the presented method. These extracted samples along with the post-extracted samples were analyzed. The absolute recovery was calculated by taking the average peak areas of the extracted samples and dividing it by the average peak area of the post extracted samples and multiplying by 100. These calculations were done for all analytes.

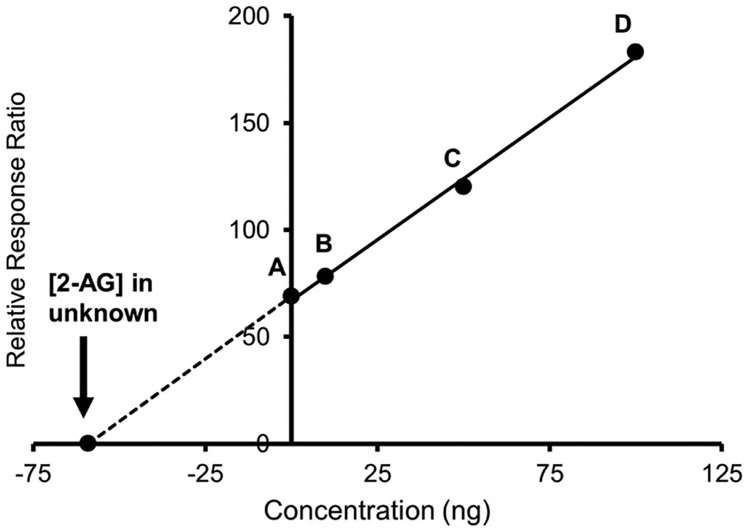

3.5. Method of Standard Addition

Additional testing by the method of standard addition [29] was used to quantify the endogenous concentration of all compounds in the C57BL/6J mice kidney homogenate to account for possible matrix effects. Using the method of direct analysis the endogenous concentrations of all the compounds were determined by analyzing kidney controls in triplicate over five different analytical runs and the mean concentrations were designated as the “expected” concentrations. The concentrations of the prepared four-point standard addition curves bracketed the expected concentrations of the kidney samples without exceeding the upper limit of quantitation of the assay. Fresh C57BL/6J mice kidney samples were pooled and homogenized. Standard addition samples were prepared as followed in triplicate: the first addition sample was fortified at a concentrations of 0.1 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 1 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 10 ng for 2-AG; 100 ng for AA; the second addition sample at concentrations of 0.5 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 5 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 50 ng for 2-AG; 500 ng for AA; the third addition sample was fortified at concentrations of 1 ng for PE2, PGE2-G, and all HETE-EAs, EET-EAs, and DiHETE-EAs; 10 ng for AEA, PEA, OEA, PGE2, PGD2; 100 ng for 2-AG; 1000 ng for AA. These samples were then extracted and analyzed as described herein with a freshly prepared calibration curve, QC samples and the kidney homogenate samples in triplicate with no addition of the endogenous compounds. The concentrations of the endogenous compounds determined by linear regression for both direct analysis and the method of standard addition.

4. Results

4.1. Method Validation

4.1.1. Linearity and LOQ

The mean calibration over five days for of all of the compounds in water yielded linear regression correlation coefficients (r2) of 0.9955 or better. The LLOQ samples were within ± 20% of the target value and had a response at least ten times greater than the signal to noise ratio of analyte-free samples. except for 5,6-DiHETE-EA where the LLOQ was not consistently determined due to low and inconsistent signal.

4.1.2. Bias and Precision

The bias and precision results for the LLOQ, LQC, MQC, and HQC can be found in Table 2. The results were within the acceptable criteria and did not exceed ± 20% of the target value, except for 5,6-DiHETE-EA where the LLOQ was not consistently determined due to low and inconsistent signal. The intra-day and inter-day precision were determined to range from 1% to 15% CV for all compounds.

Table 2.

Accuracy & Precision

| Compound | % Bias (Precision (% CV)) Intra-day (n=3) |

% Bias (Precision (% CV)) Inter-day (n=15) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLOQ | LQC | MQC | HQC | LLOQ | LQC | MQC | HQC | |

| PE2 | 13 (9) | 14 (10) | 7 (5) | −12 (9) | 3 (8) | 0 (9) | 0 (5) | 1 (8) |

| PGE2-G | −7 (14) | 11 (10) | 15 (8) | 6 (6) | −2 (8) | −1 (8) | 3 (9) | 2 (5) |

| PGE2 | 5 (9) | 15 (7) | 18 (4) | 10 (9) | 4 (6) | 7 (7) | 5 (7) | 3 (6) |

| PGD2 | 10 (14) | 13 (11) | 7 (5) | −4 (10) | 6 (8) | 5 (8) | 2 (5) | −1 (6) |

| 20-HETE-EA & 8,9-EET-EA | 10 (17) | −16 (14) | −20 (11) | 15 (10) | 0 (11) | −4 (12) | −8 (11) | 5 (11) |

| 15-HETE-EA | 17 (18) | −18 (8) | −18 (7) | 13 (8) | 5 (13) | −6 (14) | −7 (13) | 2 (10) |

| 5,6-EET-EA | −15 (15) | −18 (18) | −10 (10) | 13 (11) | 1 (12) | −9 (12) | −5 (11) | 3 (9) |

| 8,9-EET-EA | 14 (17) | −15 (16) | −9 (10) | 17 (14) | 6 (9) | −2 (13) | −2 (10) | 7 (12) |

| 11,12-EET-EA | −17 (5) | 15 (10) | −7 (11) | 17 (15) | 1 (13) | 1 (12) | −2 (9) | 3 (14) |

| 14,15-EET-EA | 17 (19) | −9 (8) | −16 (8) | 12 (9) | 2 (14) | −8 (5) | −2 (13) | 4 (8) |

| 5,6-DiHETE-EA | N/A | −18 (12) | 18 (13) | 12 (8) | N/A | 2 (13) | −2 (14) | 3 (10) |

| 11,12-DiHETE-EA | 12 (19) | −12 (10) | 16 (10) | 11 (7) | 0 (13) | −1 (10) | 0 (12) | 8 (6) |

| 14,15-DiHETE-EA | 10 (17) | −6 (13) | −12 (9) | 14 (5) | 3 (11) | −2 (9) | −1 (10) | 4 (7) |

| AA | 17 (6) | 20 (6) | −13 (7) | −18 (5) | −4 (15) | 11 (8) | −7 (9) | −6 (11) |

| AEA | 15 (11) | −14 (8) | −13 (9) | 4 (6) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| 2-AG | −13 (13) | 13 (6) | 10 (13) | 9 (8) | −1 (9) | 2 (10) | −3 (9) | 2 (7) |

| PEA | 11 (11) | 9 (15) | 12 (9) | −10(14) | 8 (9) | 0 (9) | 4 (8) | −5 (11) |

| OEA | 15 (10) | −17 (5) | 14 (11) | 9 (7) | 4 (9) | 1 (12) | 5 (9) | 4 (5) |

N/A, not applicable

4.1.3. Carryover

Lack of carryover was confirmed as none of the analytes were detected in the negative control after analysis of the highest calibrator. Lack of carryover was also confirmed for as the analyses of the LQC samples did not demonstrate a quantitated bias of more than 20% after analyses of the HQC.

4.1.4. Matrix Effects and Absolute Recovery

Ten different mouse kidneys were extracted and fortified with ISTD post-extraction. The matrix effect results are presented in Table 3a. The matrix effects and absolute recovery for all of the analytes in water are presented in Table 3b. Matrix effects ranged from −66% to −10% at the LQC and from −25% to −6% at the HQC. Recoveries at the LQC ranged from 16% to 66%, and from 27% to 77% at the HQC. The ion suppression observed was most likely due to the high matrix/analyte ratio. Matrix effects were less then ±20% for all the ISTD at their assessed concentrations in the water matrix. The kidney matrix produced greater ion suppression of the ISTD, however this was not unexpected as it is a more complex matrix. The recoveries were low for some compounds and matrix effects were noted especially in the kidney homogenate extracts. The concentrations from these samples were reproducible and the matrix effects were adjusted for by the use of the deuterated ISTDs.

Table 3a.

Matrix Effect in Water and Kidney Homogenate

| Water | Kidney | |

|---|---|---|

| ISTD (n=3) | Matrix Effect (%) |

Matrix Effect (%) |

| PE2-d4 | −4 | −4 |

| PGE2-G-d5 | 1 | 18 |

| PGE2-d4 | −3 | 12 |

| PGD2-d4 | −5 | 17 |

| AA-d8 | −2 | −63 |

| AEA-d8 | −4 | −25 |

| 2-AG-d5 | 0 | −34 |

| PEA-d4 | −18 | −50 |

| OEA-d4 | −18 | −46 |

Table 3b.

Recovery & Matrix Effect in Water

| Compound (n=3) | LQC | HQC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery (%) |

Matrix Effect (%) |

Recovery (%) |

Matrix Effect (%) |

|

| PE2 | 66 | −12 | 77 | −8 |

| PGE2-G | 60 | −11 | 62 | −9 |

| PGE2 | 16 | −16 | 35 | −8 |

| PGD2 | 22 | −13 | 38 | −9 |

| 20-HETE-EA & 8,9-EET-EA | 48 | −20 | 67 | −11 |

| 15-HETE-EA | 51 | −17 | 70 | −12 |

| 5,6-EET-EA | 37 | −18 | 60 | −11 |

| 8,9-EET-EA | 43 | −20 | 65 | −11 |

| 11,12-EET-EA | 44 | −21 | 67 | −12 |

| 14,15-EET-EA | 47 | −19 | 72 | −11 |

| 5,6-DiHETE-EA | 49 | −66 | 66 | −10 |

| 11,12-DiHETE-EA | 58 | −19 | 71 | −8 |

| 14,15-DiHETE-EA | 56 | −13 | 72 | −11 |

| AA | 67 | −28 | 69 | −6 |

| AEA | 34 | −37 | 48 | −10 |

| 2-AG | 33 | −42 | 51 | −11 |

| PEA | 17 | −29 | 27 | −25 |

| OEA | 31 | −60 | 33 | −11 |

4.1.5. Method of Standard Addition

The calculated concentrations of all of the compounds by direct analysis using the calibration curve and the standard addition curves are presented in Table 4. The concentrations for all the detectable compounds found in the C57BL/6J mice kidney homogenate samples were within ± 20% of their expected concentrations, except for OEA with a bias of −23%. The results demonstrate the matrix effects observed above did not have an impact on the analysis of the endogenous compounds using calibration curves generated in a non-matching matrix.

Table 4.

Method of standard addition

| Compound (n=3) | Direct analysis conc. (ng/g) |

Standard addition conc. (ng/g) |

% Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE2 | ND | ND | N/A |

| PGE2-G | ND | ND | N/A |

| PGE2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | −6 |

| PGD2 | ND | ND | N/A |

| 20-HETE-EA &8,9-HETE-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 15-HETE-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 5,6-EET-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 8,9-EET-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 11,12-EET-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 14,15-EET-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 5,6-DiHETE-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 11,12-DiHETE-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| 14,15-DiHETE-EA | ND | ND | N/A |

| AA | 1318 | 1217 | −8 |

| AEA | 1.0 | 0.9 | −10 |

| 2-AG | 69 | 60 | −13 |

| PEA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 |

| OEA | 0.83 | 0.64 | −23 |

ND = None Detected, N/A, not applicable

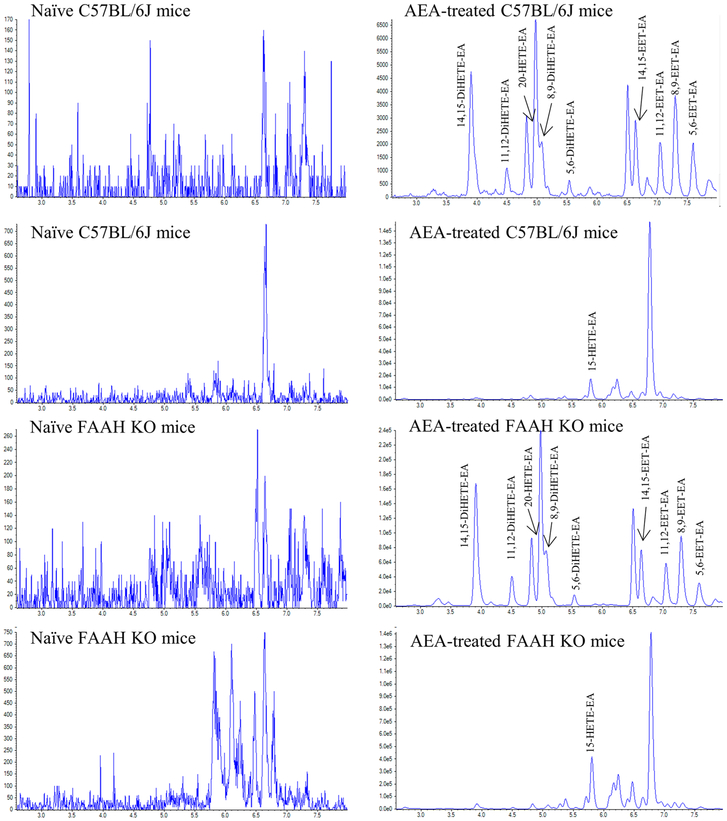

4.2. Formation of HETE-EAs and Di-HETE-EAs in vivo

Kidney tissue from naïve C57BL/6J mice, naïve FAAH KO mice, and from C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice treated with an intravenous bolus of 20 mg/kg AEA was extracted and analyzed as described above. Representative chromatograms of Period 2 of the HPLC-MS/MS method showing the HETE-EAs and DiHETE-EAs are presented in Figure 3. The DiHETE-EAs were detected in tissue from AEA-treated C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice (Figs. 3B and 3D) but not in the untreated C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice. The determined concentrations in the FAAH KO mice were between 13% and 34% greater than those found in the C57BL/6J mice, Table 5.

Figure 3.

Extracted ion chromatograms of Period 2 of kidney tissue extract from naïve and AEA-treated C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice

Table 5.

Kidney tissue concentrations (ng/g) in naïve C57BL/6J, AEA-treated C57BL/6J, naïve FAAH KO, and AEA-treated FAAH KO mice

| Compound | C57BL/6J | C57BL/6J + AEA |

FAAH KO | FAAH KO +AEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-HETE-EA & 8,9-EET-EA | ND | 2.0 | ND | 52 |

| 15-HETE-EA | ND | 3.0 | ND | 68 |

| 5,6-EET-EA | ND | 1.9 | ND | 24 |

| 8,9-EET-EA | ND | 1.5 | ND | 24 |

| 11,12-EET-EA | ND | 0.9 | ND | 13 |

| 14,15-EET-EA | ND | 1.0 | ND | 15 |

| 5,6-DiHETE-EA | ND | 3.9 | ND | 130 |

| 11,12-DiHETE-EA | ND | 1.2 | ND | 37 |

| 14,15-DiHETE-EA | ND | 4.6 | ND | 156 |

ND = None Detected

5. Discussion

The presented HPLC-MS/MS method demonstrated acceptable reliability and reproducibility for the detection and quantification of AEA, 2-AG, their metabolites, PEA and OEA in kidney specimens using a solid phase extraction method. Accuracy as well as intra-day and inter-day precision of the assay were determined not to exceed CVs of ± 20% over the dynamic range of the assay demonstrating the robustness of the assay. Additionally, the assay was free of interfering peaks from the water matrix used to prepare the calibrators and the kidney extracts were free of interfering peaks from the kidney matrix. The method was free from analyte carryover. Deuterated ISTDs were used when available to help reduce quantification issues that may occur due to the matrix effects. The comparison of the direct analysis of the non-matching matrix calibration curve as compared to the standard addition curve demonstrated that minimal effects due to the kidney matrix were observed in the resulting concentrations.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first reported in vivo formation of the HETE-EAs, EET-EAs and Di-HETE-EAs in C57BL/6J and FAAH KO mice. It was possible by administration of 20 mg/kg of anandamide. Even though the in vivo formation and biological significance of these compounds remain to be determined, they may contribute to renal hemodynamics. Since the DiHETE-EAs metabolites were commercially unavailable they were formed using mouse liver cytosol containing epoxide hydrolases. As a result of the lack of the ability to metabolize AEA by FAAH, the FAAH KO mice produced greater concentrations of the AEA metabolites than C57BL/6J mice.

5. Conclusions

An HPLC-MS/MS method with a simple solid phase extraction sample preparation was developed and validated for the simultaneous determination of the endocannabinoids AEA, 2-AG, their metabolites, PEA and OEA in kidney tissue. The dihydroxy derivatives of the EET-EAs were synthesized by microsomal epoxide hydrolase incubations and the first reported in vivo formation of the metabolites in mouse kidney was demonstrated by administration of anandamide. The presented method was shown to be reliable and robust for the detection and quantitation of endocannabinoids and their metabolites in kidney tissue and can be utilized to evaluate their role in the regulation of renal functions.

Figure 4.

Example of quantification by method standard addition approach using 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG). A = zero point 2-AG concentration; B = kidney fortified with 10 ng 2-AG; C = kidney fortified with 50 ng 2-AG; D = kidney fortified with 100 ng 2-AG. Equation of straight line y = 1.1498x + 67.912, r2= 0.9997

Highlights.

An UPLC-MS/MS method using SPE for determination of endocannabinoids

Synthesis of dihydroxy derivatives of the EET-EAs by microsomal epoxide hydrolase

First reported in vivo formation of the AEA metabolites HETE-EAs, EET-EAs and DiHETE-EAs

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders [DK102539], National Institute on Health Center for Drug Abuse [P30DA033934] and National Institute on Drug Abuse [T32DA007027-42].

Abbreviations

- 15(S)-HETE-EA

15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid ethanolamide

- 2-AG

2-Arachiodonylglycerol

- 20-HETE-EA

20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid ethanolamide

- AA

Arachidonic acid

- AEA

N- arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide)

- DiHETE-EA

Dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid ethanolamide

- EET-EA

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid ethanolamide

- OEA

Oleoylethanolamide

- PE2

Prostaglandin E2- ethanolamide (prostamide E2)

- PEA

Palmitoylethanolamide

- PGD2

Prostaglandin D2

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- PGE2-G

Prostaglandin E2- glyceryl ester

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest with this work.

References

- [1].Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R, Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor, Science, 258 (1992) 1946–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Long JZ, LaCava M, Jin X, Cravatt BF, An anatomical and temporal portrait of physiological substrates for fatty acid amide hydrolase, J Lipid Res, 52 (2011) 337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Koga D, Santa T, Fukushima T, Homma H, Imai K, Liquid chromatographic-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mass spectrometric determination of anandamide and its analogs in rat brain and peripheral tissues, J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl, 690 (1997) 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH, Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98 (2001) 9371–9376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schlosburg JE, Kinsey SG, Lichtman AH, Targeting fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) to treat pain and inflammation, AAPS J, 11 (2009) 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pacher P, Batkai S, Kunos G, The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy, Pharmacol Rev, 58 (2006) 389–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Koura Y, Ichihara A, Tada Y, Kaneshiro Y, Okada H, Temm CJ, Hayashi M, Saruta T, Anandamide decreases glomerular filtration rate through predominant vasodilation of efferent arterioles in rat kidneys, J Am Soc Nephrol, 15 (2004) 1488–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li J, Wang DH, Differential mechanisms mediating depressor and diuretic effects of anandamide, J Hypertens, 24 (2006) 2271–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Ligumsky M, Kaminski NE, Schatz AR, Gopher A, Almog S, Martin BR, Compton DR, et al. , Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors, Biochem Pharmacol, 50 (1995) 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jarai Z, Wagner JA, Goparaju SK, Wang L, Razdan RK, Sugiura T, Zimmer AM, Bonner TI, Zimmer A, Kunos G, Cardiovascular effects of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol in anesthetized mice, Hypertension, 35 (2000) 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Giang DK, Cravatt BF, Molecular characterization of human and mouse fatty acid amide hydrolases, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 94 (1997) 2238–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Blankman JL, Simon GM, Cravatt BF, A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol, Chem Biol, 14 (2007) 1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ahmad A, Daneva Z, Li G, Dempsey SK, Li N, Poklis JL, Lichtman A, Li PL, Ritter JK, Stimulation of diuresis and natriuresis by renomedullary infusion of a dual inhibitor of fatty acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase, Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 313 (2017) F1068–F1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ahmad A, Dempsey SK, Daneva Z, Li N, Poklis JL, Li PL, Ritter JK, Modulation of mean arterial pressure and diuresis by renomedullary infusion of a selective inhibitor of fatty acid amide hydrolase, Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 315 (2018) F967–F976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Harris RC, McKanna JA, Akai Y, Jacobson HR, Dubois RN, Breyer MD, Cyclooxygenase-2 is associated with the macula densa of rat kidney and increases with salt restriction, J Clin Invest, 94 (1994) 2504–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yu M, Ives D, Ramesha CS, Synthesis of prostaglandin E2 ethanolamide from anandamide by cyclooxygenase-2, J Biol Chem, 272 (1997) 21181–21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kozak KR, Crews BC, Ray JL, Tai HH, Morrow JD, Mamett LJ, Metabolism of prostaglandin glycerol esters and prostaglandin ethanolamides in vitro and in vivo, J Biol Chem, 276 (2001) 36993–36998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ritter JK, Li C, Xia M, Poklis JL, Lichtman AH, Abdullah RA, Dewey WL, Li PL, Production and actions of the anandamide metabolite prostamide E2 in the renal medulla, J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 342 (2012) 770–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hampson AJ, Hill WA, Zan-Phillips M, Makriyannis A, Leung E, Eglen RM, Bornheim LM, Anandamide hydroxylation by brain lipoxygenase:metabolite structures and potencies at the cannabinoid receptor, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1259 (1995) 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Snider NT, Kornilov AM, Kent UM, Hollenberg PF, Anandamide metabolism by human liver and kidney microsomal cytochrome p450 enzymes to form hydroxyeicosatetraenoic and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid ethanolamides, J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 321 (2007) 590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zoerner AA, Gutzki F-M, Batkai S, May M, Rakers C, Engeli S, Jordan J, Tsikas D, Quantification of endocannabinoids in biological systems by chromatography and mass spectrometry: A comprehensive review from an analytical and biological perspective, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1811 (2011) 706–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Marchioni C, de Souza ID, Acquaro VRJ, de Souza Crippa JA, Tumas V, Queiroz MEC, Recent advances in LC-MS/MS methods to determine endocannabinoids in biological samples: Application in neurodegenerative diseases, Anal Chim Acta, 1044 (2018) 12–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Garst C, Fulmer M, Thewke D, Brown S, Optimized extraction of 2-arachidonyl glycerol and anandamide from aortic tissue and plasma for quantification by LC-MS/MS, Eur J Lipid Sci Technol, 118 (2016) 814–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marczylo TH, Lam PMW, Nallendran V, Taylor AH, Konje JC, A solid-phase method for the extraction and measurement of anandamide from multiple human biomatrices, Analytical Biochemistry, 384 (2009) 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gouveia-Figueira S, Nording ML. Validation of a tandem mass spectrometry method using combined extraction of 37 oxylipins and 14 endocannabinoid-related compounds including prostamides from biological matrices, Prostaglandins OtherLipid Mediat, 121 (2015) 110–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Weber A, Ni J, Ling KH, Acheampong A, Tang-Liu DD, Burk R, Cravatt BF, Woodward D, Formation of prostamides from anandamide in FAAH knockout mice analyzed by HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry, J Lipid Res, 45 (2004) 757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kessler FK, Ritter JK, Induction of a rat liver benzo[a]pyrene-trans-7,8-dihydrodiol glucuronidating activity by oltipraz and beta-naphthoflavone, Carcinogenesis, 18 (1997) 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zeldin DC, Kobayashi J, Falck JR, Winder BS, Hammock BD, Snapper JR, Capdevila JH, Regio- and enantiofacial selectivity of epoxyeicosatrienoic acid hydration by cytosolic epoxide hydrolase, J Biol Chem, 268 (1993) 6402–6407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Novak J, Janak J, Comments on the standard addition method used in quantitative gas chromatographic analysis, J Chromatogr, 28 (1967) 392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]