Abstract

Objectives:

T cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of early systemic sclerosis. This study assessed the safety and efficacy of abatacept in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc).

Methods:

A 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with participants randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either abatacept 125 mg subcutaneous or matching placebo, stratified by duration of dcSSc. Escape therapy was allowed at six months for worsening disease. The co-primary end points were change in modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) and safety over 12 months. Treatment differences in longitudinal outcomes were assessed using linear mixed models, with outcomes censored after initiation of escape therapy. Baseline skin tissue was classified into intrinsic gene expression subsets.

Results:

Among 88 participants, the adjusted mean change in mRSS at 12 months was −6.24 units in the abatacept and −4.49 units in the placebo, with adjusted mean treatment difference of −1.75 units (p=0.28). Two secondary outcome measures (HAQ-DI and a composite measure) were clinically and statistically significant favoring abatacept. A larger proportion of placebo subjects required escape therapy relative to abatacept (36% vs. 16%). Decline in mRSS over 12 months was clinically and significantly higher in abatacept vs. placebo for the Inflammatory (p<0.001) and Normal-like skin gene expression subsets (p=0.03). 35 participants in the abatacept versus 40 in the placebo had adverse events (AEs), including two and one deaths, respectively.

Conclusions:

In this Phase 2 trial, abatacept was well tolerated, but change in mRSS was not statistically significant. Secondary outcome measures, including gene expression subsets, showed some evidence in favor of abatacept. These data should be confirmed in a Phase 3 trial.

Funding:

This trial was funded by Bristol Myers-Squibb. The biomarker data was funded by NIH/NIAID (Clinical Autoimmunity Center of Excellence).

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc, scleroderma) is an immune-mediated rheumatic disease characterized by fibrosis in the skin and internal organs, and by vasculopathy[1]. It has the highest case fatality of any rheumatic disease. One sub classification of this disease, diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc), has a 10-year mortality rate of 50%[1]. There are no licensed treatments for SSc; disease management is focused on organ-specific complications[2].

Published evidence supports the concept that T cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of dcSSc, including cutaneous disease and at least some of the visceral complications[3–5]. Skin biopsies obtained from dcSSc patients early in their disease demonstrate a perivascular, mononuclear cell infiltrate comprised of T cells and macrophages[3, 4]. The numbers of T cells have been found to correlated with the degree of skin thickening in the biopsy sites. T cells are the dominant population of lymphocytes in the skin, and are activated in SSc. The adaptive immune system gene expression signature is higher in the skin in early dcSSc than in established dcSSc[6]. Animal studies support the role of abatacept (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 immunoglobulin fusion protein [CTLA-4-Ig]) in the management of dcSSc, as it attenuates skin and lung fibrosis in models of scleroderma[7, 8]. In addition, a 24-week, placebo-controlled pilot study (N=10) showed that the abatacept was safe [9]. When incorporating the molecular gene expression data in skin, 4 of 5 participants with the Inflammatory subset improved on abatacept[9].

Based on these observations, we conducted a Phase 2 trial to evaluate weekly subcutaneous (SC) abatacept vs. placebo in dcSSc. The primary objectives were to assess safety and efficacy on skin thickening, as assessed by mRSS, in a 12-month double-blind study in patients with relatively early disease (≤ 36 months). We hypothesized baseline mRSS scores might be lower in patients with early disease duration (≤ 18 months) and higher in longer disease duration (>18 and ≤ 36 months) and that the impact of abatacept might differ by duration of disease. We stratified by disease duration to control for disease duration in the overall analysis, while allowing us to explore the ability of abatacept to prevent or reverse dcSSc progression in patients with early disease duration and to reverse established disease in patients with longer disease duration. In addition, our a priori hypothesis was that participants with Inflammatory gene signature will have a statistically significant decline in mRSS over 12 months.

Methods

Study Design

This was a Phase 2, investigator-initiated, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of abatacept in patients with dcSSc (clinicaltrials.gov ). dcSSc was defined as skin thickening, proximal as well as distal, to the elbows or knees with or without involvement of the face and neck at the time of study entry. Study participants were treated for 12 months on double-blind study medication, and were offered an additional six months of open-label SC abatacept therapy. The end-of-study event was a telephone call 30 days after the last dose of study drug to discuss any adverse events (AEs) that may have occurred. The Sponsor, Dinesh Khanna, MD, MSc, received an Investigational New Drug exemption from the Food and Drug Administration. Each participating site’s institutional review board or ethics committee approved the Study Protocol (available in the Protocol Section) before the research commenced. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Good Clinical Practice.

Study Participation Criteria

Key inclusion criteria were: (1) adult participant, age 18 years and older; (2) diagnosis of SSc, as defined using the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European Union League Against Rheumatism classification of SSc[10] and dcSSc, as defined by LeRoy and Medsger[11]; and (3) disease duration of ≤36 months (defined as time from the first non-Raynaud phenomenon manifestation). For disease duration of ≤18 months, an mRSS ≥10 and ≤35 units was required at the screening visit. For disease duration of >18 to ≤36 months, an mRSS of ≥15 and ≤45 units was required along with one of the following conditions which must have been observed at the screening visit, compared to the patient’s last visit in the previous one to six months: (1) increase of ≥3 mRSS units, (2) involvement of one new body area with increase of ≥2 mRSS units, (3) involvement of two new body areas with increase of ≥1 mRSS unit, and/or (4) presence of one or more tendon friction rubs.

Oral corticosteroids (≤10 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent) and NSAIDs were permitted if the patient was on a stable dose regimen for ≥2 weeks prior to and including the baseline visit, but no background immunomodulatory therapies were allowed. More details are available in the Study Protocol (available in the Protocol Section). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Randomization and Masking

Eligible participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either 125 mg SC abatacept or matching placebo (provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb), stratified by duration of dcSSc disease (≤18months vs. >18 to ≤36 months). The first injection was given at the research office and the subsequent study medications were injected weekly at home. The Data Coordinating Center (DCC) at the University of Michigan prepared the randomization schedule, using computer-generated block randomization with the random block sizes of 2 and 4 (known only by the DCC). The study staff (including the research pharmacists) and participants were blinded to the treatment assigned.

Procedures

Participants were seen at regular intervals throughout the 12-month study period. Study assessments and their timing are summarized in the Study Protocol (see Section 6 of the Protocol). Screening took place within 28 days before randomization. Eligible patients were assessed at baseline; at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 in clinic; and 30 days after the last dose by phone (for those who did not continue into the open-label period).

Escape therapy with immunomodulatory agents was permitted as add-on therapy to study medications, starting at month 6, due to worsening of the dcSSc (Protocol Page 28). The decision to initiate escape therapy was based on investigator discretion. No biologic agents were allowed as the escape therapy.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was change in mRSS at 12 months. The same assessor performed the mRSS measurement at each time point during the trial. Live demonstration and standardization of mRSS for the trial occurred during an investigator meeting prior to study initiation, where it was agreed to use the average score at each anatomical site[12]. Secondary outcome measures included: (1) change from baseline to months 1, 3, 6, and 9 in mRSS; (2) change from baseline to months 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 in 28-swollen and tender joint count; (3) change from baseline to months 3, 6 and 12 in patient global assessment for overall disease, physician global assessment for overall disease, PROMIS-29 v2 Profile, health assessment questionnaire-disability index (HAQ-DI), Scleroderma-HAQ-DI visual analogue scales (VAS) assessing pain, burden of digital ulcers, Raynaud’s, gastrointestinal involvement, breathing, and overall disease, and UCLA Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) 2.0; and (4) change from baseline to months 6 and 12 in FVC% predicted, and the American College of Rheumatology Combined Response Index in Systemic Sclerosis (ACR-CRISS, a composite end point that captures cardio-pulmonary-renal involvement and change in mRSS, HAQ-DI, patient global assessment, physician global assessment, and FVC% predicted).

The exploratory end points included: (1) change from baseline to months 3, 6 and 12 in interference with the patient’s physical functioning related to skin involvement and pain intensity due to SSc over the previous week on a 0–150 mm VAS; (2) proportion of participants with cardiac involvement, significant ILD, and new renal crisis at 12 months; (3) change from baseline in body mass index and digital ulcer burden at 12 months; and (4) change from baseline to months 6 and 12 in DLCO% predicted (corrected for hemoglobin) and FVC (in ml).

Safety end points were: (1) proportion of participants experiencing AEs; (2) incidence of AEs, serious AEs (SAEs), and AEs of special interest; (3) treatment discontinuation due to AEs; and (4) changes in clinical laboratory tests, vital signs, and physical examination results over time. The study was overseen by a Data and Safety Monitoring Committee that reviewed study conduct and safety outcomes approximately every six months.

RNA-sequencing, Read Alignment and Gene Expression Calculation

Skin biopsy (3 mm) of the involved forearm skin was performed at each site, at baseline and at months 3 and 6. Biopsies were stored in RNAlater® and skin biopsies were processed for RNA as previously reported[13]. Machine learning was used to classify biopsies into intrinsic gene expression subsets. RNA-seq data (RPKM) were normalized and baseline skin biopsies were classified into Inflammatory, Normal-like or Fibroproliferative intrinsic gene expression subsets[13]. For details on the methodology, see Supplementary Text 1.

Statistical Analysis

This study was sized based on practical considerations rather than a desired power for a pre-specified difference. We planned to screen 121 patients to randomize 86 participants. With this sample size, we calculated we could detect an effect size of at least 0.66 in the primary end point with 80% power, 5% two-sided Type I error and 15% drop-out (two-sample t test, East 5.4). This effect size translates into a treatment difference in change from baseline to month 12 in mRSS of 5.3, with an SD of 8 points[14]. Sample sizes to detect published minimal clinically important differences for endpoints used in diffuse systemic sclerosis are detailed in Supplementary Text 2; that provide context on the sample size needed for a confirmatory study.

The main analysis set for efficacy was the modified intention to treat (mITT) population, defined as all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication. We analysed the primary end point using a linear mixed model as described in Supplementary Text 2. Escape therapy after six months is an indication of treatment failure; therefore, we censored primary end point data after initiation of escape therapy. In an additional sensitivity analysis, we applied the same model using all mRSS values (i.e., no censoring after escape therapy). Adjusted least squares (LS) means, standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and two-sided p-values for between-treatment comparisons are provided. Safety outcomes are summarized by treatment group using descriptive statistics; no tests were performed.

Analyses of all secondary end points used the same approach as for the primary end point, except for the ACR-CRISS that used a non-parametric approach; these are detailed in the Supplementary Text 2. No adjustments for multiplicity were made, thus p-values for secondary and exploratory outcomes should be interpreted with caution. In addition, Supplementary Text 2 also provides the analysis approach for gene signature data. The full statistical analysis plan was finalized before unblinding. SAS version 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

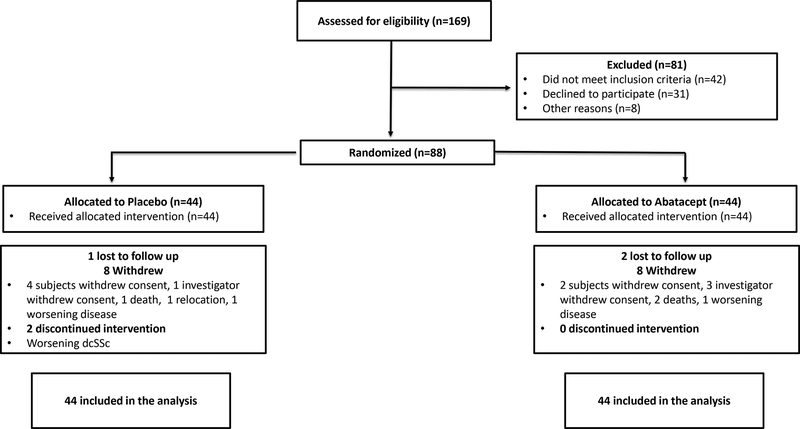

One hundred sixty-nine participants were screened for eligibility and 88 (44 in each treatment group) were randomized at 22 centers in the US, Canada and UK between September 22, 2014 and March 15, 2017 (Figure 1). Thirty-four (77%) and 35 (80%) completed the 12-month trial in the abatacept and placebo groups, respectively. At 12 months, 7 (16%) and 16 (36%) in the abatacept and placebo groups, respectively, had received escape therapy for worsening dcSSc (Supplementary Table 1). Eighty-eight participants were included in the mITT and safety analyses and 85 in the per-protocol analysis (43 in abatacept and 42 in placebo). Similar numbers of patients withdrew in each group. In the abatacept group, ten patients withdrew due to the following reasons: investigator withdrew consent (N=3), subject withdrew consent (N=2), lost to follow up (N=2), death (N=2), and worsening dcSSc (N=1). In the placebo group, nine patients withdrew due to following reasons: investigator withdrew consent (N=1), subject withdrew consent (N=4), lost to follow up (N=1), death (N=1), relocation (N=1), and worsening dcSSc (N=1). Compliance with the study drug was >98% (one participant in the placebo group had compliance <80%). Estimated study medication exposure was median (1st to 3rd quartile) 10.7 (5.2 to 11.1) months in the abatacept group and 10.6 (9.1 to 10.8) months in the placebo group. The demographic and baseline disease characteristics were balanced between the treatment groups (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Enrollment of Participants and Study Flow

Table 1 :

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics

| Overall (N=88) |

Placebo (N=44) |

Abatacept (N=44) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Years, mean (SD) | 49 (13) | 49 (13) | 50 (12) |

| Female, N (%) | 66 (75%) | 35 (80%) | 31 (70%) |

| White, N (%) | 72 (82%) | 37 (84%) | 35 (80%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino, N (%) | 76 (86%) | 36 (82%) | 40 (91%) |

| Disease Duration, Years*, mean (SD) | 1.59 (0.81) | 1.52 (0.79) | 1.66 (0.84) |

| Disease ≤18 Months, N (%) | 53 (60%) | 27 (61%) | 26 (59%) |

| mRSS, mean (SD) | 22.45 (7.65) | 21.57 (7.33) | 23.34 (7.95) |

| FVC% Predicted, mean (SD) | 85.4 (15.10) | 86.5 (16.60) | 84.2 (13.50) |

| DLCO% Predicted, Corrected for Hgb, mean (SD) | 78.0 (18.24) | 76.5 (18.44) | 79.6 (18.12) |

| Patient Global Assessment, mean (SD) [theoretical range 0–10] | 4.09 (2.38) | 4.31 (2.56) | 3.88 (2.21) |

| HAQ-DI, mean (SD) [theoretical range 0–3] | 1.05 (0.71) | 0.97 (0.70) | 1.14 (0.72) |

| Physician Global Assessment, mean (SD) [theoretical range 0–10] | 4.77 (1.67) | 4.76 (1.67) | 4.77 (1.67) |

| Tendon Friction Rubs, N (%) | 32 (36%) | 13 (30%) | 19 (43%) |

| Large Joint Contractures, N (%) | 63 (72%) | 32 (73%) | 31 (70%) |

| Swollen Joint Count, mean (SD) [theoretical range 0–28] | 3.75 (5.70) | 3.86 (5.85) | 3.64 (5.62) |

| Proportion of Participants with ≥ 1 Swollen Joint Count, N (%) | 42 (48%) | 21 (48%) | 21 (48%) |

| Use of Prednisone, N (%) | 12 (14%) | 5 (11%) | 7 (16%) |

| Prednisone dose in mg, mean (SD) | 7.9 (2.6) | 7.0 (2.7) | 8.6 (2.4) |

Disease onset was defined as first non-Raynaud’s sign or symptoms; mRSS=modified Rodnan skin score; FVC=Forced vital capacity, DLCO =Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide

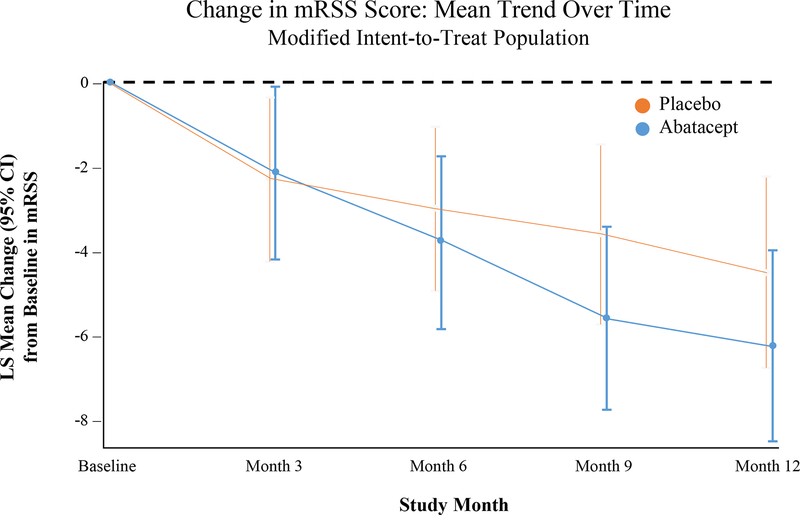

The primary outcome measure was not statistically significant – the LS mean change (SE) in mRSS was −6.24 (1.14) in the abatacept group and −4.49 (1.14) in the placebo group, with a treatment difference of −1.75 (95% CI −4.93, 1.43; Table 2 and Figure 2). Sensitivity analyses using the per-protocol population and incorporating all values after escape therapy in the mITT population provided comparable results (Table 2). There also were no statistically significant differences in the change in mRSS at months 1, 3, 6, and 9 (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2:

Results of changes from baseline to month 12 in primary and secondary efficacy end points

|

Efficacy

End Points (Change from Baseline to Month 12) |

Placebo (N=44) | Abatacept (N=44) | (Abatacept – Placebo) | P-value✢ |

| LS mean (SE) | LS mean difference (95%CI) | |||

| Primary analysis: mITT with values censored after escape therapy | −4.49 (1.14) | −6.24 (1.14) | −1.75 (−4.93, 1.43) | 0.28 |

| Sensitivity analysis 1: per protocol with values censored after escape therapy | −4.63 (1.15) | −6.25 (1.13) | −1.62 (−4.79, 1.55) | 0.31 |

| Sensitivity analysis 2: mITT with values not censored after escape therapy | −4.22 (1.04) | −6.64 (1.10) | −2.42 (−5.38, 0.54) | 0.11 |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Patient Global Assessment (0–10)* | −0.09 (0.46) | −0.31 (0.42) | −0.22 (−1.45, 1.01) | 0.73 |

| Physician Global Assessment (0–10)* | −0.35 (0.32) | −1.30 (0.29) | −0.95 (−1.80, −0.10) | 0.03 |

| FVC% Predicted | −4.13 (1.22) | −1.34 (1.24) | 2.79 (−0.69, 6.27) | 0.11 |

| FVC (ml) | −121.6 (46.39) | −36.39 (43.82) | 85.21 (−42.75, 213.16) | 0.19 |

| HAQ-DI (0–3)* | 0.11 (0.07) | −0.17 (0.07) | −0.28 (−0.47, −0.09) | 0.005 |

| S-HAQ-Overall VAS (0–150)* | 3.52 (6.05) | −7.42 (5.64) | −10.94 (−27.27, 5.38) | 0.19 |

| S-HAQ-Breathing VAS (0–150)* | 16.95 (5.85) | 9.30 (5.51) | −7.65 (−23.60, 8.30) | 0.34 |

| S-HAQ-Raynaud’s VAS (0–150)* | −3.64 (7.17) | 7.58 (6.60) | 11.22 (−8.04, 30.47) | 0.25 |

| S-HAQ-Digital Ulcers VAS (0–150)* | 8.67 (5.52) | −3.18 (5.13) | −11.85 (−26.70, 3.01) | 0.12 |

| S-HAQ-GI VAS (0–150)* | 8.01 (6.42) | 9.98 (6.00) | 1.96 (−15.40, 19.33) | 0.82 |

| Swollen Joint Count (0–28)* | −0.86 (0.60) | −0.11 (0.60) | 0.75 (−0.91, 2.41) | 0.37 |

| Tender Joint Count (0–28)* | −1.47 (0.91) | −0.71 (0.90) | 0.76 (−1.75, 3.27) | 0.55 |

| PROMIS-29 Physical Function | −0.17 (0.69) | −1.54 (0.65) | −1.36 (−3.23, 0.50) | 0.15 |

| PROMIS-29 Anxiety* | −1.09 (1.37) | −3.50 (1.31) | −2.41 (−6.15, 1.32) | 0.20 |

| PROMIS-29 Depression* | −0.41 (1.20) | −0.02 (1.13) | 0.39 (−2.86, 3.64) | 0.81 |

| PROMIS-29 Fatigue* | −0.98 (1.36) | −0.65 (1.29) | 0.33 (−3.37, 4.03) | 0.86 |

| PROMIS-29 Sleep Disturbance* | −0.21 (0.62) | −0.31 (0.57) | −0.10 (−1.76, 1.57) | 0.91 |

| PROMIS-29 Pain Interference* | −1.56 (1.22) | −4.10 (1.13) | −2.53 (−5.81, 0.74) | 0.13 |

| PROMIS-29 Social Roles* | −1.26 (1.14) | −1.11 (1.07) | 0.15 (−2.93, 3.24) | 0.92 |

| PROMIS-29 Pain Intensity (0–10)* | −0.18 (0.33) | −0.72 (0.32) | −0.54 (−1.44, 0.37) | 0.24 |

| UCLA GIT 2.0 Total Score (0.00–2.83)* | −0.05 (0.050) | 0.07 (0.047) | 0.12 (−0.01, 0.26) | 0.07 |

|

Placebo

(N=44) Median (IQR) |

Abatacept (N=44) Median (IQR) |

P-value** | ||

| ACR CRISS at 12 Months | 0.02 (0.75) | 0.72 (0.99) | 0.03** | |

LS = least squares; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval

For primary and sensitivity analyses, the estimates and p-values are from a linear mixed model with treatment group, month (3, 6, 9 and 12), treatment group x month interaction, and baseline mRSS as fixed effects and participant as a random effect.

For secondary analyses, the estimates and p-values are from a linear mixed model with treatment group, month, treatment group x month interaction, duration of dcSSc (≤18 vs >18 to ≤36 months), and baseline variable as fixed effects and participant as a random effect.

mITT population includes all of the randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication. Per protocol population includes mITT participants who did not experience a major protocol deviation, defined as eligibility criteria violations for which no exemption was granted, study drug compliance <80% and >120%, and receipt of escape medication prior to month 3.

P values should be interpreted with caution as they are not adjusted for multiplicity.

Higher score denotes worse symptom

van Elteren test, adjusting for duration of dcSSc. Five participants in each group had cardio-pulmonary-renal involvement and were given a probability score of 0.0. Multiple imputation was used to address missing follow-up data in mRSS, FVC% predicted, HAQ-DI and patient and physician global assessments, allowing calculation of the ACR-CRISS score.

Figure 2:

Change in the modified Rodnan skin score during 12-month period

There were statistically significant and clinically meaningful treatment differences in LS mean improvements at 12 months in HAQ-DI (−0.28, p=0.005, Table 2). There were no statistical differences in the swollen and tender joint counts between abatacept and placebo at 12 months (LS mean difference 0.75 [0.84], p=0.37 and 0.76 [1.28], respectively, p=0.55). In addition, there were statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in a new composite index, the ACR-CRISS, that favored abatacept. The median change in ACR-CRISS score was 0.68 (0.99) vs. 0.01 (0.75), p=0.03 at 12 months with proportion of patient who improved by ≥ 0.60, the clinically meaningful cutpoint[15] significantly higher in the abatacept group (62.8% vs. 37.2%, p=0.01 using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusting for duration of dcSSc). Other secondary outcomes are presented in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2.

In analyses of exploratory end points, the proportion of participants who decreased in mRSS by ≥5 units (a clinically important improvement)[16] was similar in abatacept and placebo (Supplementary Table 3). When the change in mRSS at 12 months was evaluated by disease duration (≤18 months vs. >18 to ≤36 months) in an ad hoc analysis, numerically greater treatment effects were seen in mRSS in early disease (≤18 months; n=53) than in later disease (>18 to ≤36 months; n=35). LS mean changes of mRSS in the abatacept group were −5.71 and −6.62 units in the early and later disease groups, while in the placebo group, they were −2.98 and −6.18 units. This resulted in LS mean (95% CI) treatment difference of −2.73 (−6.57, 1.11) in early disease (p=0.16) and −0.44 (−6.10, 1.11) in later disease (p=0.88).

A total of 23 (26%) participants required escape therapy for their worsening dcSSc, with a larger proportion requiring escape in the placebo group [16 (36%)] than in the abatacept group [7 (16%)]. The reasons for escape therapy included: worsening skin (8 in placebo and 4 in abatacept), worsening ILD (2 in placebo), polyarthritis (3 in placebo), and overall worsening disease (4 in placebo and 4 in abatacept). There was no increase in infections among those who were started on escape therapy and continued on abatacept (1 event; 0.4 person-year) vs. those who did not start escape therapy (27 events; 0.8 person-year). In comparison, participants on placebo who were started on escape therapy had 3 events (0.6/person-year) vs. 40 events (1.2/person-year) among those who did not start escape therapy.

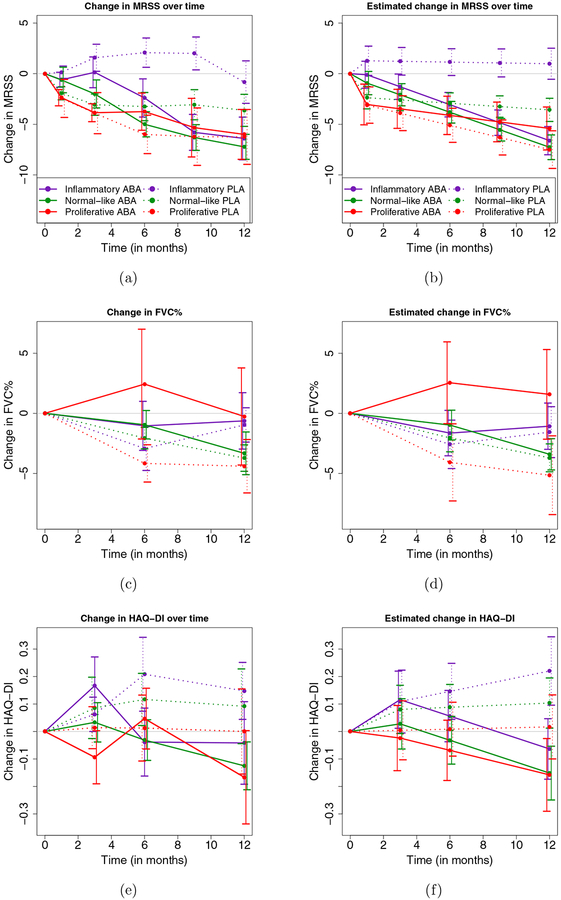

Gene expression in skin biopsies was analyzed in 84 patients at baseline (abatacept, N=43; placebo, N=41). No systemic biases were found related to collection site, time of biopsy, or the RNA-seq analysis. Intrinsic gene expression subset (e.g., Inflammatory, Normal-like, Fibroproliferative) was assigned using a machine learning classifier before the unblinding of the study. At baseline, 33 (39%) patients were classified as Inflammatory, 33 (39%) were classified as Normal-like, and 18 (21%) were classified as Fibroproliferative. Participants with earlier disease (disease duration ≤ 18 months) were more likely to be part of the inflammatory subset (21/33, 64%) or normal-like (23/33, 70%) than fibroproliferative (7/18, 39%). There were no significant differences between the distribution of intrinsic gene expression subsets at baseline in each treatment arm (Supplementary Table 4). LS mean change in mRSS over 12 months was significantly different between the abatacept and placebo for the Inflammatory (p<0.001) and Normal-like subgroups (p=0.03) (Supplementary Table 5 and Figure 3), but there was no difference in the Fibroproliferative subset (p=0.47). For FVC% predicted, the Fibroproliferative subset showed a numerical increase in FVC% in the abatacept arm (p=0.19) while all other groups showed decreases in FVC%. All gene expression subgroups showed numerical decreases in HAQ-DI in the abatacept arm that were not observed in the placebo arm.

Figure 3:

Observed average change (left panels) and estimated average change from baseline in MRSS, FVC% and HAQ-DI (right panels) in the Placebo and Abatacept group and in the three intrinsic gene expression subsets. In each plot, vertical bars represent +/− 1 standard error. Estimates are obtained from a linear mixed model fitted to the change from baseline in MRSS, FVC% and HAQ-DI, respectively, with predictors: MRSS, FVC% and HAQ-DI at baseline, respectively, month in the study, treatment group, interaction of treatment group and month and a subject-specific random effect.

Safety

Abatacept was found to be generally safe with no new safety signals, with lower numbers of participants experiencing AEs, infectious AEs, and SAEs compared to the placebo group (Table 3). More participants experienced SAEs in the placebo group (27%) vs. abatacept group (20%; Table 3). These included more non-infectious SAEs (23% vs. 16%) and the same number of infectious SAEs (5% each). In addition, more participants in the placebo group dropped out due to AEs (6 [14%] vs. 5 [11%] in abatacept). Renal crisis occurred in three participants (days 11, 25, and 46 after initiation of study medication) in the abatacept group vs. one participant in placebo group (day 56 after starting study medication). The number of participants with treatment emergent AEs by severity grade were similarly distributed among the two treatments, with a total of 36 (82%) in abatacept and 40 (91%) in placebo experiencing an AE (Supplementary Table 6). There were no cases of tuberculosis during the trial. No significant laboratory abnormalities were noted—one participant in each group had a hemoglobin decline of >2 gm/dL related to dcSSc (among participants with baseline values ≥ 8 gm/dL). There were 20 AEs of special interest in the abatacept group and 26 in the placebo group, including one injection site reaction in the abatacept group (Supplementary Table 7).

Table 3:

Adverse, infectious, and serious adverse events

| Placebo N=44 |

Abatacept N=44 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Participants with ≥ 1 AE | 40 (91%) | 35 (80%) |

| Participants with ≥ 1 infectious AE | 25 (57%) | 19 (43%) |

| Withdrawal because of an AE | 6 (14%) | 5 (11%) |

| Participants with ≥ 1 SAE | 12 (27%) | 9 (20%) |

| Participants with Specific SAEs | ||

| Infections and Infestations | ||

| Cellulitis | 1 | |

| Mastoiditis | 1 | |

| Paronychia | 1 [a] | |

| Pneumonia | 1 [b] | |

| Cardiac Disorders | ||

| Atrial flutter with conduction defects | 1 [b] | |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 [b] | |

| Myocardial infarction/acute coronary syndrome | 1 [c] | 1 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1 [b] | 1 [d] |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 [d] | |

| Gastrointestinal Disorders | ||

| Anemia | 1 | |

| Cholecystitis | 1 | |

| Dysphagia | 1 | 1 [e] |

| Erosive esophagitis | 1 | |

| Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia | 1 | |

| Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia with anemia | 1 | |

| Melena | 1 [f] | |

| Pseudo-obstruction | 1 [f] | |

| Neoplasm Disorders | ||

| Basal cell skin carcinoma | 1 | |

| Squamous cell skin carcinoma | 1 | |

| Respiratory Disorders | ||

| Respiratory failure | 1 [g] | |

| Renal Disorders | ||

| Scleroderma renal crisis | 1 | 3 [e] [g] |

| Vascular Disorders | ||

| Digital ischemia | 1 [a] | |

| Mental Disorders | ||

| Depression with suicidal ideation | 1 [c] |

indicate events that occurred in the same participant

Three deaths occurred in the study. One participant died due to cardiac arrest at 310 days after starting the study medication (placebo); this death was not considered related to the study medication. Two participants experienced scleroderma renal crisis leading to death in the abatacept group—one died at day 11 after randomization due to renal crisis (considered not related to the study medication) leading to respiratory failure (considered related to the study medication). The second participant was admitted due to gastrointestinal dysmotility and myositis at day 25 and then had renal crisis at day 46; both were considered not related to the study medication.

Discussion

In this Phase 2 trial, we showed that abatacept is well tolerated in early dcSSc. Although we did not achieve a statistically significant treatment difference in the primary efficacy end point – the change from baseline in mRSS at 12 months – there were clinically meaningful and statistically significant differences in HAQ-DI, a measure of function and ACR-CRISS. In addition, a larger proportion of participants required immunomodulatory escape therapy with placebo vs. abatacept, further supporting the favorable impact of abatacept. In addition, this is the first prospective trial showing the intrinsic gene expression subsets can predict clinical outcome measures with greater precision.

Skin involvement was chosen as the primary outcome measure, as it is an important concern for patients due to its relationship to disability caused by small and large joint contractures, pruritus, and allodynia[17]. Skin thickness, as assessed by mRSS, is a feasible, reliable, valid outcome measure and is sensitive to change[12]. In addition, mRSS is utilized by scleroderma physicians to assess for worsening and improvement of skin involvement[1]. In early disease, skin involvement is a surrogate for internal organ involvement and mortality[18, 19]. Due to this, mRSS has been incorporated as the primary end point in early SSc trials[20]. However, statistical negative results in this trial is similar to recent published[20] and presented[21] data from studies of anti-IL-6 receptor in the treatment of SSc. This occurred despite recruitment of a study population in this trial with early disease (mean disease duration of 1.59 years); 60% of patients were recruited within 18 months of diagnosis, and only 14% had been treated with background immunosuppressive therapy. There was a significant heterogeneity in mRSS trajectory over the 12-month study period (Supplementary Table 3) [22, 23], which is likely driven by the autoantibodies[24] and skin gene expression profile[25].

Abatacept therapy did produce a clinically meaningful and statistically significant difference over placebo in a validated measure of function, the HAQ-DI[26] and numerical improvements in other patient-reported outcome measures (although many did not achieve clinically meaningful thresholds). These changes are important, as they directly address the FDA mandate to assess how a patient feels, functions, and survives (FDA Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21). The efficacy of abatacept is also suggested by the lower proportion of participants who required escape therapy for worsening in dcSSc relative to placebo (26% vs 36%, respectively). These data should be interpreted with caution due to no adjustments for multiplicity.

In addition, there were statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in a new composite index, the ACR-CRISS[15], that favored abatacept. ACR-CRISS was designed to capture the global or holistic evaluation of the likelihood of improvement in early SSc. ACR-CRISS is based on a probability score of 0.0 (no improvement) to 1.0 (marked improvement with an improvement of ≥ 0.60 considered as clinically meaningful) and includes two steps. The first step assesses for worsening or incident cases of cardio-pulmonary-renal involvement and gives a score of 0.0. For those who do not meet Step 1, a probability score is calculated that incorporates changes in five physical or functional areas — mRSS (assessment of skin), FVC% predicted (assessment of lungs), HAQ-DI (measure of patient function), patient global assessment, and physician global assessment. The median change in ACR-CRISS score was 0.68 (0.99) vs. 0.01 (0.75), p=0.03 with proportion of patient who improved by ≥ 0.60 significantly higher in the abatacept group. These results are similar to recent data from a Phase 3 trial of tociluzimab[21] and highlights the importance of global assessment in a multisystem heterogeneous disease.

Participants on placebo had greater numbers of AEs, AEs leading to discontinuation and SAEs, highlighting the safety of abatacept in SSc. This was also true in those who were on abatacept and other immunomodulatory therapies—data supported by studies of other rheumatic diseases where abatacept has been used with immunosuppressive therapy[27, 28].

There were three deaths in the trial, two in the abatacept group and one in the placebo group. Both deaths in the abatacept group were related to scleroderma renal crisis, a dreaded complication in early SSc. There was one additional case of scleroderma renal crisis in the abatacept group that did not result in death. All three cases occurred early in the disease (11–46 days after randomization), while the one case in the placebo group occurred 56 days after randomization. Inhibition of Treg function prior to reduction in the numbers and activity of pathogenic effector T cells in abatacept-treated patients could account for early flares but eventual reduction in disease activity in SSc[29, 30], but data are needed to validate this hypothesis.

A prior pilot study of abatacept in SSc with molecular gene expression data in skin[9] found that four of five patients who improved on abatacept, as determined by change in mRSS, were in the Inflammatory subset while the other patient who improved was in the Normal-like subset. Improvement was accompanied by a decrease in gene expression for immune pathways, including the CD28 and CTLA4 receptors—the target of abatacept. In this trial, we were able to test and support our a priori hypothesis that the Inflammatory subset shows a significant decline in mRSS during abatacept therapy. The results are especially interesting and novel considering the likely mechanism of action for abatacept as a targeted immunomodulator. On this basis, it would be expected that cases showing the Inflammatory gene signature would be most likely to demonstrate treatment effect in the skin (Figure 3). The most striking difference for mRSS changes for both the actual and estimated plots is for the Inflammatory subset. There is marked divergence of the trajectory for MRSS change in the Inflammatory cases compared with the other intrinsic subsets, that reaches statistical significance, and no apparent impact for the Fibroproliferative subgroup (Supplementary Table 5). In contrast, for FVC change, which may reflect lung fibrosis[31], it is only the Fibroproliferative subset that showed trends that favored abatacept. This points towards different potential molecular pathology between the skin and lung in SSc and is consistent with impact of abatacept on different components of the disease biology at different sites. It is also notable that mRSS is improved by abatacept whereas for FVC the apparent impact in Fibroproliferative cases is to prevent decline. These data are consistent with results from the pilot study of abatacept [9] and extend these findings, for the first time, to a large placebo-controlled trial that shows intrinsic skin gene expression subsets may predict differential response to a targeted biological therapy. This has implication for stratification of cases according to intrinsic gene expression subsets to maximize the number of informative SSc cases in clinical trials, and potentially for future clinical practice.

Our study has many strengths. First, we included experienced sites and were able to recruit participants with early active disease. Second, despite a large proportion of participants who went on escape therapy (26%), we made every effort to continue follow-up of these participants in the trial and capture actual data. Third, we continued to build a body of evidence about the potential utility of ACR-CRISS as an alternative primary endpoint to the use of changes in skin thickness, given the number of negative SSc studies using mRSS as the primary endpoint. The ACR-CRISS is also supported by statistical significant results of the proof-of-concept trial of Lenabasum[32] (ACR CRISS was the primary outcome measure) and post-hoc and planned analyses in the Phase 2 and Phase 3 data with tociluzimab[21, 33] where mRSS has not been able to differentiate study medication vs. placebo in these trials. Last, one of the novel aspects of this study was the ascertainment of intrinsic gene expression-based subsets (Inflammatory, Fibroproliferative or Normal-like) at baseline that could be integrated into a subgroup analysis for potential treatment effect.

Study limitations include the lack of positive trials in early dcSSc that could provide guidance for the sample size calculation; and missing data, which we addressed using mixed models and multiple imputation—both valid under the missing at random assumption. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons and control the Type I error for secondary and exploratory endpoints; thus, we cannot make definitive statements about these outcomes and should be considered hypotheses generating. We considered both the clinical importance of abatacept effects, the totality of the study data, and the literature on other biologics in SSc in deriving conclusions for our study. We allowed background low dose prednisone (as done universally in trials of early SSc) at the study entry and 14% were taking low-dose prednisone at baseline visit. The impact of background prednisone on skin gene expression data is unknown (personal communication: Dr Michael Whitfield) and should be explored in future analyses. We have not reported the autoantibodies data and its relationship to outcome measures—we plan to perform these in a central laboratory in near future. Finally, although the participants are representative of other recent trials in early dcSSc, these may differ from patients seen in clinics[34].

In summary, abatacept was well tolerated, but change in mRSS was not statistically significant. Secondary outcome measures showed some evidence in favor of abatacept. A Phase 3 trial should be conducted before drawing definitive conclusions about the efficacy and safety of abatacept in dcSSc.

Supplementary Material

Role of the funding source

This was an investigator-initiated trial designed by the Sponsor (Dinesh Khanna, MD, MSc) and the steering committee. The industry funder, Bristol-Myer Squibb (BMS), had no role in collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the data. Mechanistic studies, including analysis of gene expression in skin biopsies, was funded by the NIH/NIAID through the University of Michigan Clinical Autoimmunity Center of Excellence. The data were stored at the University of Michigan DCC. The manuscript was drafted by Khanna and Spino with input from other co-authors and was reviewed by BMS and NIH/NIAID before final submission. No medical writer was involved in creating the manuscript.

Funding:

NIH/NIAID Clinical Autoimmunity Center of Excellence to the University of Michigan 5UM1AI110557

Dinesh Khanna, MD, MSc is supported by NIH/NIAMS K24 AR063120 and NIH/NIAMS R01 AR-07047.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Dr Khanna is a consultant to Actelion, Acceleron, Arena, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myer Squibb, CSL Behring, Corbus, Cytori, GSK, Genentech/Roche, Galapagos, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabi, and UCB; he has received grants as part of investigator-initiated trials (to the University of Michigan) from Bayer, Bristol-Myer Squibb, and Pfizer; and has stock options in Eicos Sciences, Inc and employment with Civi BioPharma, Inc. Dr. Chung is a consultant to Reata, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Eicos Sciences, Inc. Dr. Chung has also received grants from United Therapeutics. Dr. Molitor is a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim and Amgen. He has also received grants from Pfizer. Dr. Lafyatis is a consultant to PRISM Biolab, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Biocon, UCB, Formation, Sanofi, and Genentech/Roche. He has received grants from PRISM Biolab, Regeneron, Elpidera, and Kiniksa. Dr. Domsic is a consultant to Eicos Sciences Inc. and Boehringer-Ingelheim. Dr. Pope is a consultant for Actelion, Baxter, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Merck, and Roche. She has received research grants from Baxter, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Eicos Sciences Inc, Merck, Roche, and Seattle Genetics. Dr. Gordon has received grants from Corbus and Cumberland Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Schiopu has received research grants from Bristol-Myer Squibb and Bayer. Dr. Bernstein is a consultant to Genentech as a medical monitor for SLS III. She has also received grants for investigator-initiated research from Pfizer and ASPIRE Rheumatology program. Dr. Castelino is a consultant to Genentech and Boehringer. Dr. Allanore is a consultant to BMS, Genentech/Roche, Sanofi, Bayer, Actelion, and Inventiva. Dr. Allanore has also received grants from Genentech/Roche, Sanofi, and Inventiva. Dr. Matucci-Cerinic is a consultant and has received grants from Bristol-Myer Squibb. Dr. Fox is a consultant as a grant reviewer for Pfizer. He has also received research grants from Regeneron, Gilead, and Seattle Genetics. Drs. Spino, Johnson, Whitfield, Berrocal, Franks, Mehta, Steen, Simms, Gill, Kafaja, Frech, Hsu, Mayes, Young, Sandorfi, Park, Hant, Chatterjee, Ajam, Wang, Wood, Distler, Singer, Bush, and Furst report no conflict of interest pertinent to this manuscript.

Previous presentation: The trial was presented at the American College of Rheumatology Meeting in Chicago in 2018 and the EULAR meeting in Madrid in 2019.

References

- 1.Denton CP, Khanna D: Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390(10103):1685–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, Becker M, Kulak A, Allanore Y, Distler O, Clements P, Cutolo M, Czirjak L, Damjanov N, Del Galdo F, Denton CP, Distler JHW, Foeldvari I, Figelstone K, Frerix M, Furst DE, Guiducci S, Hunzelmann N, Khanna D, Matucci-Cerinic M, Herrick AL, van den Hoogen F, van Laar JM, Riemekasten G, Silver R, Smith V, Sulli A, Tarner I et al. : Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017, 76(8):1327–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalogerou A, Gelou E, Mountantonakis S, Settas L, Zafiriou E, Sakkas L: Early T cell activation in the skin from patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005, 64(8):1233–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roumm AD, Whiteside TL, Medsger TA Jr., Rodnan GP: Lymphocytes in the skin of patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Quantification, subtyping, and clinical correlations. Arthritis Rheum 1984, 27(6):645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischmajer R, Perlish JS, Reeves JR: Cellular infiltrates in scleroderma skin. Arthritis Rheum 1977, 20(4):975–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assassi S, Khanna D, Hinchcliff M, Steen VD, Hant F, Gordon JK, Shah AA, Ying J, Swindell WR, Zheng W, Zhu L, Shanmugam VK, Domsic RT, Castelino FV, Bernstein EJ, Frech TM: Cell Type Specific Gene Expression Analysis of Early Systemic Sclerosis Skin Shows a Prominent Activation Pattern of Innate and Adaptive Immune System in the Prospective Registry for Early Systemic Sclerosis (PRESS) Cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017, 69 (Suppl 10). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponsoye M, Frantz C, Ruzehaji N, Nicco C, Elhai M, Ruiz B, Cauvet A, Pezet S, Brandely ML, Batteux F, Allanore Y, Avouac J: Treatment with abatacept prevents experimental dermal fibrosis and induces regression of established inflammation-driven fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016, 75(12):2142–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boleto G, Guignabert C, Pezet S, Cauvet A, Sadoine J, Tu L, Nicco C, Gobeaux C, Batteux F, Allanore Y, Avouac J: T-cell costimulation blockade is effective in experimental digestive and lung tissue fibrosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2018, 20(1):197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakravarty EF, Martyanov V, Fiorentino D, Wood TA, Haddon DJ, Jarrell JA, Utz PJ, Genovese MC, Whitfield ML, Chung L: Gene expression changes reflect clinical response in a placebo-controlled randomized trial of abatacept in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015, 17:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, Matucci-Cerinic M, Naden RP, Medsger TA Jr., Carreira PE, Riemekasten G, Clements PJ, Denton CP, Distler O, Allanore Y, Furst DE, Gabrielli A, Mayes MD, van Laar JM, Seibold JR, Czirjak L, Steen VD, Inanc M, Kowal-Bielecka O, Muller-Ladner U, Valentini G, Veale DJ, Vonk MC, Walker UA, Chung L et al. : 2013. classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65(11):2737–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr.: Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2001, 28(7):1573–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanna D, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Allanore Y, Baron M, Czirjak L, Distler O, Foeldvari I, Kuwana M, Matucci-Cerinic M, Mayes M, Medsger T Jr., Merkel PA, Pope JE, Seibold JR, Steen V, Stevens W, Denton CP: Standardization of the modified Rodnan skin score for use in clinical trials of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017, 2(1):11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milano A, Pendergrass SA, Sargent JL, George LK, McCalmont TH, Connolly MK, Whitfield ML: Molecular subsets in the gene expression signatures of scleroderma skin. PLoS One 2008, 3(7):e2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanna D, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Korn JH, Ellman M, Rothfield N, Wigley FM, Moreland LW, Silver R, Kim YH, Steen VD, Firestein GS, Kavanaugh AF, Weisman M, Mayes MD, Collier D, Csuka ME, Simms R, Merkel PA, Medsger TA Jr., Sanders ME, Maranian P, Seibold JR, Relaxin I, the Scleroderma Clinical Trials C: Recombinant human relaxin in the treatment of systemic sclerosis with diffuse cutaneous involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2009, 60(4):1102–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna D, Berrocal VJ, Giannini EH, Seibold JR, Merkel PA, Mayes MD, Baron M, Clements PJ, Steen V, Assassi S, Schiopu E, Phillips K, Simms RW, Allanore Y, Denton CP, Distler O, Johnson SR, Matucci-Cerinic M, Pope JE, Proudman SM, Siegel J, Wong WK, Wells AU, Furst DE: The American College of Rheumatology Provisional Composite Response Index for Clinical Trials in Early Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016, 68(2):299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna D, Clements PJ, Volkmann ER, Wilhalme H, Tseng CH, Furst DE, Roth MD, Distler O, Tashkin DP: Minimal Clinically Important Differences for the Modified Rodnan Skin Score: Results from the Scleroderma Lung Studies (SLS-I and SLS-II). Arthritis Res Ther 2019, 21(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiese AB, Berrocal VJ, Furst DE, Seibold JR, Merkel PA, Mayes MD, Khanna D: Correlates and responsiveness to change of measures of skin and musculoskeletal disease in early diffuse systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014, 66(11):1731–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clements PJ, Hurwitz EL, Wong WK, Seibold JR, Mayes M, White B, Wigley F, Weisman M, Barr W, Moreland L, Medsger TA Jr., Steen VD, Martin RW, Collier D, Weinstein A, Lally E, Varga J, Weiner SR, Andrews B, Abeles M, Furst DE: Skin thickness score as a predictor and correlate of outcome in systemic sclerosis: high-dose versus low-dose penicillamine trial. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43(11):2445–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA Jr.: Skin thickness progression rate: a predictor of mortality and early internal organ involvement in diffuse scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis 2011, 70(1):104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna D, Denton CP, Jahreis A, van Laar JM, Frech TM, Anderson ME, Baron M, Chung L, Fierlbeck G, Lakshminarayanan S, Allanore Y, Pope JE, Riemekasten G, Steen V, Muller-Ladner U, Lafyatis R, Stifano G, Spotswood H, Chen-Harris H, Dziadek S, Morimoto A, Sornasse T, Siegel J, Furst DE: Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab in adults with systemic sclerosis (faSScinate): a phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387(10038):2630–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanna D, Lin C, Kuwana M, Allanore Y, Batalov A, Butrimiene I, Carreira PE, Cerinic MM, Distler O, Kaliterna DM, Mihai C, Mogensen M, Olesinska M, Pope JE, Riemekasten G, Rodriguez-Reyna TS, Santos MJ, van Laar J, Spotswood H, Siegel J, Jahreis A, Furst DE, Denton CP: Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab for the Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis: Results from a Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018, 69 (Suppl 10). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amjadi S, Maranian P, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Wong WK, Postlethwaite AE, Khanna PP, Khanna D, Investigators of the D-Penicillamine HRR, Oral Bovine Type ICCT: Course of the modified Rodnan skin thickness score in systemic sclerosis clinical trials: analysis of three large multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum 2009, 60(8):2490–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shand L, Lunt M, Nihtyanova S, Hoseini M, Silman A, Black CM, Denton CP: Relationship between change in skin score and disease outcome in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: application of a latent linear trajectory model. Arthritis Rheum 2007, 56(7):2422–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrick AL, Peytrignet S, Lunt M, Pan X, Hesselstrand R, Mouthon L, Silman AJ, Dinsdale G, Brown E, Czirjak L, Distler JHW, Distler O, Fligelstone K, Gregory WJ, Ochiel R, Vonk MC, Ancuta C, Ong VH, Farge D, Hudson M, Matucci-Cerinic M, Balbir-Gurman A, Midtvedt O, Jobanputra P, Jordan AC, Stevens W, Moinzadeh P, Hall FC, Agard C, Anderson ME et al. : Patterns and predictors of skin score change in early diffuse systemic sclerosis from the European Scleroderma Observational Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018, 77(4):563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stifano G, Sornasse T, Rice LM, Na L, Chen-Harris H, Khanna D, Jahreis A, Zhang Y, Siegel J, Lafyatis R: Skin Gene Expression Is Prognostic for the Trajectory of Skin Disease in Patients With Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018, 70(6):912–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna D, Furst DE, Hays RD, Park GS, Wong WK, Seibold JR, Mayes MD, White B, Wigley FF, Weisman M, Barr W, Moreland L, Medsger TA Jr., Steen VD, Martin RW, Collier D, Weinstein A, Lally EV, Varga J, Weiner SR, Andrews B, Abeles M, Clements PJ: Minimally important difference in diffuse systemic sclerosis: results from the D-penicillamine study. Ann Rheum Dis 2006, 65(10):1325–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langford CA, Monach PA, Specks U, Seo P, Cuthbertson D, McAlear CA, Ytterberg SR, Hoffman GS, Krischer JP, Merkel PA, Vasculitis Clinical Research C: An open-label trial of abatacept (CTLA4-IG) in non-severe relapsing granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). Ann Rheum Dis 2014, 73(7):1376–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, Chalmers A, D’Cruz D, Wallace DJ, Bae SC, Sigal L, Becker JC, Kelly S, Raghupathi K, Li T, Peng Y, Kinaszczuk M, Nash P: The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2010, 62(10):3077–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langdon K, Haleagrahara N: Regulatory T-cell dynamics with abatacept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Int Rev Immunol 2018, 37(4):206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frantz C, Auffray C, Avouac J, Allanore Y: Regulatory T Cells in Systemic Sclerosis. Front Immunol 2018, 9:2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sargent JL, Milano A, Bhattacharyya S, Varga J, Connolly MK, Chang HY, Whitfield ML: A TGFbeta-responsive gene signature is associated with a subset of diffuse scleroderma with increased disease severity. J Invest Dermatol 2010, 130(3):694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiera R, Hummers L, Chung L, Frech T, Domsic R, Hsu V, Furst DE, Gordon J, Mayes M, Simms R, Lee E, Dgetluck N, Constantine S, White B: OP0006 Safety and efficacy of lenabasum (JBT-101) in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis subjects treated for one year in an open-label extension of trial jbt101-ssc-001. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2018, 77(Suppl 2):52–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khanna D, Berrocal VJ, denton CP, Jahreis A, Spotswood H, Lin C, Siegel J, Furst DE: Evaluation of American College of Rheumatology Provisional Composite Response Index in Systemic Sclerosis (CRISS) in the Fasscinate Trial [abstract]. In., vol. 69 (Suppl 10). Arthritis Rheumatol.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villela R, Yuen SY, Pope JE, Baron M, Canadian Scleroderma Research g: Assessment of unmet needs and the lack of generalizability in the design of randomized controlled trials for scleroderma treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2008, 59(5):706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franks JM, Martyanov V, Cai G, Wang Y, Li Z, Wood TA, Whitfield ML: A Machine Learning Classifier for Assigning Individual Patients with Systemic Sclerosis to Intrinsic Molecular Subsets. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.