1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune syndrome with pleiotropic clinical manifestations, characterized by the synthesis of autoantibodies, and the development of significant immune dysregulation, and organ damage. While life expectancy in SLE has improved due to the advancement of immunosuppressive therapies and improved treatments for infections and renal disease, mortality rates remain approximately 3-fold higher than in the general population.1 Of the many causes of mortality in SLE, accelerated atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is recognized as one of the most prevalent.2 SLE patients showed a higher prevalence of CAD and atherosclerosis compared to controls, which could not be predicted by traditional risk factors alone.3 As CVD-inflicted mortality accounts for more than one-third of all deaths in SLE patients4, it is clear that CVD continues to be a significant threat to SLE patients.

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is the smallest lipoprotein and is well-known to exhibit various atheroprotective effects independent of cholesterol mobilization, including its anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and anti-apoptotic abilities.5 Thus, the low levels of HDL had been associated with an increased risk of CVD. SLE patients with accelerated atherosclerosis exhibit decreased levels of HDL and the development of dysfunctional HDL.6–8 Such evidence suggests that HDL is likely a novel target for minimizing the risk of CVD in SLE patients, and several studies have recently proposed and investigated HDL-targeted therapies as a potential therapeutic intervention SLE patients with CVD. In this review, we will discuss the quantitative and qualitative roles of HDL in both normal and SLE conditions, as well as the potential of HDL-targeted therapeutic interventions.

2. Structure and Composition of High-Density Lipoproteins

HDL is constantly remodeled in the bloodstream through interactions with other lipoproteins, enzymes, and contact with target cells, resulting in significant particle heterogeneity. HDL consists of a core of hydrophobic lipids, including cholesteryl esters and triglycerides, and a surface monolayer containing phospholipid, free cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) is the most abundant protein associated with HDL, comprising 70% of the total HDL protein content.9 ApoA-I is a 28.1 kDa, highly α-helical and amphipathic scaffold protein consisting of 243 amino acids that interact with lipids to ultimately define the size and shape of HDL species.9

In addition to proteins, lipid species are another key component of the overall structure of HDL. Recent lipidome analysis from Kontush et al. revealed that more than half of the total HDL mass is accounted for by lipid components, the majority being phospholipids – accounting for 40–60% of the total lipid mass.10 Of these phospholipids, phosphatidylcholines are the largest population, making up 33 – 45% of total lipid mass, and play critical roles in particle stability, cholesterol efflux, and molecular interactions with HDL-associated enzymes.10

HDL can be classified into different sub-populations using various techniques. An overview of HDL classification is summarized in Table 1, based on the publication of Rosenson et al.11 Briefly, the use of density gradient ultracentrifugation and nondenaturing gradient gel electrophoresis can distinguish HDL sub-populations on the basis of density and size, respectively; from smallest to largest, HDL3c, HDL3b, HDL3a, HDL2a, and HDL2b.11 ApoA-I containing HDL sub-populations can also be defined on the basis of size and charge: pre-β-1 HDL (very small, discoidal HDL with apoA-I and phospholipid), α-4 HDL (very small, discoidal HDL with apoA-I, phospholipid, and free cholesterol), α-3 HDL (small, spherical HDL with apoA-I, apoA-II phospholipid, free cholesterol, cholesteryl ester, and triglyceride), α-2 HDL (medium-sized, spherical HDL with same constituents as α-3 HDL), and α-1 HDL (very large, spherical HDL with same constituents as α-3 HDL but nearly no apoA-II).11 Using more sophisticated techniques, such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), 26 different HDL sub-populations have been identified, but due to limited measurement precision they are simply described as small, medium, and large.11 Recently, an NMR-based clinical analyzer called the Vantera® was developed to measure total HDL particle number in clinical laboratory settings.12

Table 1.

Classification of HDL

| Separation | Analytical Method | Very Small | Small | Medium | Large | Very Large | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | Ultracentrifugation | Classification | HDL3 | HDL2 | |||

| Range (F1.2) | 0 - 3.5 | 3.5 - 9 | |||||

| Density gradient ultracentrifugation | Classification | HDL3c | HDL3b | HDL3a | HDL2a | HDL2b | |

| Range (g/mL) | 1.154 - 1.170 | 1.129 - 1.154 | 1.110 - 1.129 | 1.088 - 1.110 | 1.063 - 1.087 | ||

| Size | Nondenaturing gradient gel electrophoresis | Classification | HDL3c | HDL3b | HDL3a | HDL2a | HDL2b |

| Range (nm) | 7.2 - 7.8 | 7.8 - 8.2 | 8.2 - 8.8 | 8.8 - 9.7 | 9.7 - 12.9 | ||

| 2-D gel electrophoresis | Classification | pre-β-1 | α-4 | α-3 | α-2 | α-1 | |

| Range (nm) | 5.0 - 6.0 | 7.0 −7.5 | 8.5 −8.5 | 9.0 - 9.4 | 10.8 - 11.2 | ||

| NMR | Classification | Small | Medium | Large | |||

| Range (nm) | 7.3 −8.2 | 8.2 −9.4 | 9.4 - 14 | ||||

3. Changes in HDL Composition in SLE Patients

3.1. Dyslipoproteinemia

Many SLE patients have increased levels of VLDL and LDL and decreased levels of HDL, considered as the “lupus lipoprotein pattern”. Low HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) is one of the most prevalent dyslipidemia indicators observed in SLE patients, including pediatric populations.13–18 In a multiethnic U.S. cohort study containing 546 SLE patients, 81% had low HDL-C levels (< 35 mg/dL).17 A recent Egyptian study reported 45% of 221 SLE patients presented low HDL-C level (< 40 mg/dL).18 In some instances, no significant differences in HDL-C levels were found between SLE and controls, which may be explained by differences in patient population.8 Nevertheless, other HDL-related abnormalities were identified in those studies such as reduced PON-1 activies.8 It is noteworthy that HDL-C, which is routinely determined in clinical laboratories, is usually considered synonymous to HDL particle level. However, it has been increasingly recognized that the HDL-C may not be an approriate surrogate of HDL levels since the cholesterol content of HDL does not correlate perfectly with the number of HDL particles.12 Alternatively, some studies determined HDL levels by measuring apoA-1 concentrations by immunochemistry methods, and lower apoA-1 levels were found in SLE patients relative to healthy subjects.13 Recently, direct measurement of HDL particle numbers has been made possible in clinical labs by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods.12 Chung et al. found that SLE patients had lower numbers of HDL particles compared to healthy volunteers with NMR method.19 Patients with active disease have lower HDL levels20–23, while use of prednisone and hydroxychloroquine correlates with higher HDL-C. 22,24 In contrast, simvastatin and atorvastatin have not been found to modify HDL-C levels in SLE patients.25,26

3.2. Changes in HDL Size Distribution in SLE patients

Lupus patients have been found to have a different distribution of HDL sub-fractions and HDL sizes compared to healthy controls (Table 2). However, it should be noticed that these studies are inconsistent and yet remained to be controversial due to the dynamic changes of HDL in inflammatory states which is further discussed in detail in a subsequent section. Hua et al. reported that small HDL is less prevalent in SLE patients, while the overall HDL size is increased in SLE patients compared to healthy controls.27 Similarly, Chung et al. reported that SLE patients have a lesser proportion of large HDL; however, the overall sizes of HDL were no different between SLE and healthy individuals.19 Other studies have also reported no significant differences in HDL size between SLE patients and healthy controls.16 Juárez-Rojas et al. reported that SLE patients tend to have lower proportions of HDL2b and higher proportions of HDL3b and HDL3c.28 Similar results were reported by Formiga et al., where SLE patients had higher levels of HDL3-C and lower levels of HDL2-C.29 Since the negative correlation between large HDL levels, positive correlation between small HDL levels and cardiovascular risks have been frequently reported in non-SLE population,30 low levels of large HDL may also be associated with enhanced proatherogenic responses in SLE patients.

Table 2.

Changes in lipoprotein profile and HDL composition in SLE patients

| Author (Year) | Subjects | HDL changes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delgado Alves (2002) | 32 lupus patients with 20 matched control | PON1 activity ↓, HDL2 ↓, HDL3 ↓ | 35 |

| McMahon (2006) | 154 women with SLE | Pro-inflammatory HDL ↑ | 38 |

| Juárez-Rojas (2008) | 30 women with uncomplicated SLE, and 18 matched controls | Cholesteryl ester ↓ Triglycerides ↑ ApoA-1 ↓ HDL size ↓ HDL2b ↓ HDL3b, HDL3 ↑ |

28 |

| Batuca (2009) | 77 lupus patients | PON1 activity ↓ | 34 |

| Smith (2014) | SLE patients and healthy control | Oxidized ApoA-1 ↑ | 39 |

| Marsillach (2015) | 54 SLE patients and 25 matched healthy controls | PON3 ↓ | 62 |

| Gaal (2016) | 51 SLE patients with 49 matched healthy controls | SAA combination ↑ PON1 arylesterase activity ↓ |

16 |

| Han (2016) | 18 subjects with SLE | SAA combination ↑ | 33 |

| Kiss (2017) | 37 SLE patients | ApoA-1 ↓ PON1 activity ↓ |

8 |

3.3. Proteomic and Lipidomic Changes in SLE HDL Composition

HDL in SLE also has abnormal proteomic features, with changes in apoA-I being the most noteworthy. In the study of Machado et al., female adolescents with SLE had higher HDL-C/apoA-I ratio compared to healthy controls, indicating the HDL particles in those SLE patients had a lesser amount of apoA-I.31 Juárez-Rojas et al. reported less apoA-I and more apoE content in HDL particles isolated from women with SLE but without other known conditions affecting lipoprotein profiles such as diabetes, infection and lipid-regulating drugs.28 However, in another study comparing 51 SLE patients with 49 healthy controls, SLE subjects were found to have higher apoA-I/HDL ratio, although the overall serum apoA-I level was lower.16 Similar to proteomic alterations, the lipidome of HDL is also compromised in the SLE setting. Juárez-Rojas et al. found that HDL isolated from SLE patients had less cholesteryl ester and more triglyceride compared to healthy controls.28 Moreover, lipid peroxidation is enhanced in SLE patients due to enhanced oxidative stress that promotes a significant increase in the production of oxidized lipids.32 Further, Gaal et al. and Han et al. found that SLE patients display significantly increased levels of serum amyloid A (SAA) compared to healthy subjects.16,33 Additionally, multiple studies confirmed a significant reduction in paraoxonase- (PON) 1 and PON-3 activity in SLE patients.8,16,34,35 The abnormal lipoprotein profiles in SLE patients are summarized in Table 2.

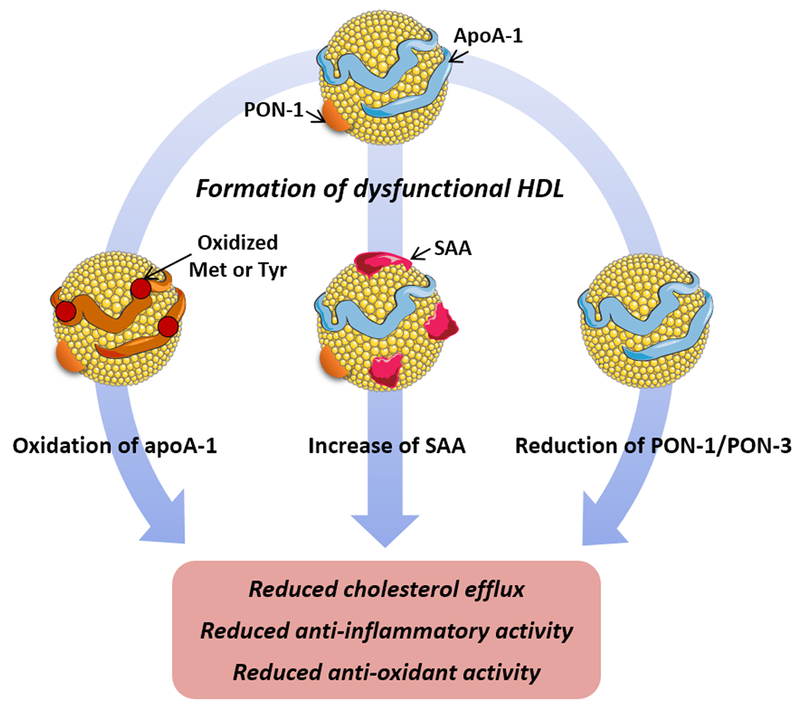

3.4. Pro-inflammatory HDL

HDL exerts anti-inflammatory functions in healthy subjects. However, during inflammatory states, the composition of HDL is altered, and the function of HDL is compromised. This can lead to the transformation of HDL into a dysfunctional, pro-inflammatory particle with reduced cholesterol efflux capacity and unable to perform its normal anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative functions (Figure 1).36 Compared to normal HDL, pro-inflammatory HDL (piHDL) is characterized by increased SAA content, decreased apoA-I levels and increase apoA-I oxidation, and decreased PON activity.16 Increased SAA content of HDL results in its displacement of apoA-I, thus, reducing the atheroprotective properties of HDL.37 McMahon et al. reported that 44.7% of SLE patients have increased levels of piHDL in comparison to only 4.1% of controls and 20.1% of rheumatoid arthritis patients.38 Their subsequent study identified piHDL to be associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) and plaque by carotid ultrasound, suggesting that dysfunctional piHDL significantly contributes to the development of subclinical atherosclerosis in SLE.6

Figure 1.

Formation of dysfunctional HDL or proinflammatory (piHDL) in SLE. In SLE, multiple HDL proteomic changes occur leading to the impairment of HDL’s function. Oxidation of apoA-I methionine and tyrosine residues by chemical and enzymatic pathways leads to reduced HDL’s ability to efflux cholesterol outside the cell and neutralize oxidized lipids. Increased levels of serum amyloid A (SAA) caused displacement of apoA-I on HDL and reduced cholesterol efflux and anti-inflammatory activity. Reduced levels and activity of HDL associated PON-1 lead to the reduced anti-oxidant activity of HDL. Abbreviations: ApoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I; Met, methionine; Tyr, tyrosine; PON, paraoxonase.

3.5. Oxidized HDL

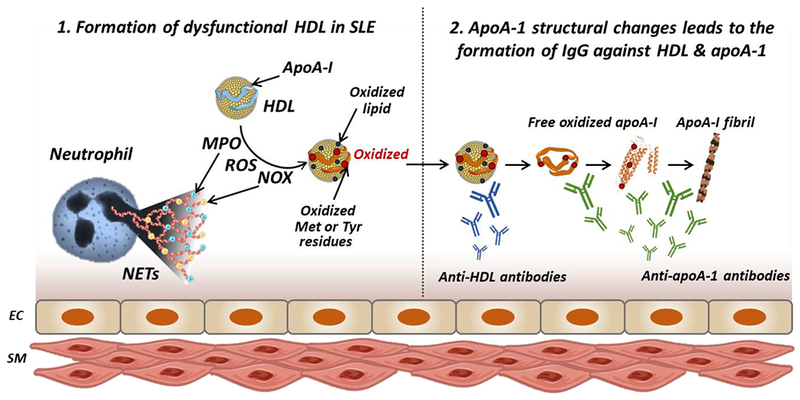

HDL also undergoes structural changes in SLE due to oxidation, and it has been found that SLE patients have higher oxidized HDL (Figure 1).39 Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is the main oxidant enzyme responsible for the oxidation of HDL. MPO-catalyzed oxidation converts normal tyrosine on apoA-I to 3-chlorotyrosine or 3-nitrotyrosine, leading to oxidized HDL.40 MPO also oxidizes three methionine residues of apoA-I, methionine (Met)-86, Met-112, and Met-148, contributing significantly to enhancing levels of oxidized apoA-I.41 In SLE patients, a high concentration of serum MPO is reported, implying a link between increased HDL oxidation and increased MPO in this disease. Recent studies found associations between HDL oxidation and elevated formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).39 Under normal conditions, NETs play an important antimicrobial role, however, in SLE, NETs are dysregulated. It was reported that the degradation of NETs is hindered in SLE patients, resulting in aberrant elevation of NETs and infiltration of netting neutrophils in tissues. 42 Carlucci et al. demonstrated that SLE patients present higher levels of low-density granulocytes (LDGs), which are one subset of neutrophils with enhanced NET formation capacity.43 The increased LDGs levels are found to be associated with the impaired cholesterol efflux capacity of HDL isolated from lupus patients.43 It has been proposed that enhanced levels of NETs enhances the oxidant potential in SLE and leads to the externalization to the extracellular space of oxidant enzymes such as MPO, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and NADPH oxidase (NOX), ultimately promoting oxidation of HDL (Figure 2). 43,44 Data from SLE patients showed that MPO and NOX from NETs promote 3-chlorotyrosine modification, and NOS and NOX promote 3-nitrotyrosine modification on HDL, while inhibition of NETs decreased the oxidation of HDL. These observations support the notion that NETs play a major role in the oxidation of HDL in SLE.39

Figure 2.

Formation of dysfunctional HDL and autoantibodies against HDL and apoA-I in SLE. In SLE, abnormal elevation of NETs is observed leading to endothelial cell damage. In presence of NETs increased levels of MPO, NOS, NOX, and ROS are observed causing oxidation of HDL and apoA-I. Oxidation of apoA-I and HDL induces the formation of anti-HDL and anti-apoA-I autoantibodies. Furthermore, oxidation of apoA-I at Met148 leads to conformational changes of apoA-I promoting protein misfolding, dissociation of misfolded apoA-I from HDL and formation of apoA-I amyloid fibrils. This aggregated apoA-I in more immunogenic leading to further increase in anti-apoA-I autoantibody titers. Abbreviations: ApoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I; EC, endothelial cell; SM, smooth muscle cell; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NOX, NADPH oxidase; Met, methionine; Tyr, tyrosine.

In addition to MPO, lipid peroxidation products also mediate the oxidation of HDL. Studies showed that oxidized phospholipids could covalently react with apoA-I at various sites, forming lipid-protein adducts.45 It was also found that lipid hydroperoxide could chemically react with apoA-I and apoA-II, leading to the oxidation of Met residues to methionine sulfoxide.46 Since clinical studies have shown that lipid peroxidation is enhanced in SLE patients, this may also contribute to the increased oxidation of apoA-I and HDL in this disease.47

4. Functional Changes in HDL in SLE Patients

4.1. Impaired Cholesterol Efflux Capacity

Removal of excess cholesterol from macrophages in the artery wall is recognized to be the key process of HDL for protection against atherosclerosis and improvement of cardiovascular outcomes. This process, known as reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), allows translocating excess cholesterol and other lipids from lipid-laden macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions to the liver for elimination. The first and most crucial step in RCT is to efflux cholesterol from macrophages to HDL. HDL isolated from SLE patients displays a 15% decrease in cholesterol efflux ability compared to healthy control HDL.39Decreased cholesterol efflux capacity of HDL purified from the SLE patients has been found to signfiicantly correlate with increased noncalcified coronary plaque burden.43 Multiple studies propose that the reason for decreased cholesterol efflux ability of HDL in SLE is due to increased levels of SAA. As mentioned earlier, increased levels of SAA promote dysfunctional piHDL with diminished ability to remove cholesterol from macrophages and traffic cholesteryl ester to liver.48

Oxidation of HDL can also contribute to its reduced cholesterol efflux capacity in SLE. HDL containing oxidized apoA-I has reduced the ability to efflux cholesterol.49,50 Furthermore, when Met-148 is oxidized in apoA-I, HDL loses the ability to interact with lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), an enzyme responsible for the conversion to cholesterol ester, which is a key step in RCT.51 Thus, the oxidation of apoA-I could be a key reason for the impaired process of cholesterol efflux in SLE.

4.2. Reduced Anti-inflammatory Function

In recent years, it has become widely accepted that HDL can directly inhibit the inflammation processes that lead to the development of atherosclerosis.52 Although the complex anti-inflammatory mechanisms of HDL have not been fully elucidated, it is suggested that several signaling pathways play a role in this process. First, HDL can inhibit toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways through activation of the transcriptional repressor, activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3). Activated ATF3 is translocated into the nucleus and inhibits the promotion of TLR-induced inflammatory cytokines.53 HDL can also inhibit nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-activated cell adhesion molecule expression, thus preventing vascular inflammation.54

In contrast to the anti-inflammatory response promoted by healthy HDL, HDL purified from SLE patients induces a pro-inflammatory response. Smith et al. reported that HDL in SLE fails to inhibit cytokine induction driven by TLR pathways.55 In comparison to macrophages exposed to healthy HDL, macrophages treated with SLE HDL induced activation of NF-κB and increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-6. In addition, macrophages treated with SLE HDL had significantly repressed ATF3 activation compared to control HDL or untreated group, suggesting that HDL from SLE cannot inhibit TLR pathways via ATF3 activation.

The oxidation of HDL in SLE promotes the binding of HDL to lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX1R), preventing ATF3 nuclear translocation and leading to increased synthesis of inflammatory cytokines.56 Lupus HDL was also found to be able to directly upregulate monocyte platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) and increase chemotaxis and TNF-α release.57 Another study associated the loss of anti-inflammatory function of HDL in SLE to the increased SAA content in HDL particles. In normal conditions, HDL can inhibit inflammatory responses by disrupting lipid rafts and sequestering plasma membrane cholesterol, however, it is suggested that the SAA binding on the surface of HDL impedes the interaction between HDL and cell membrane, decreasing the anti-inflammatory role of HDL.33

4.3. Reduced Antioxidant Capacity

In both the general population and in individuals with SLE, increased levels of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) is a well-recognized risk factor for CVD.58 Under normal conditions, HDL prevents LDL oxidation by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS). The increased levels of oxidized HDL and oxidized apoA-I in SLE reduce the ability of HDL particles to scavenge ROS. In addition, piHDL in SLE may promote LDL oxidation. Elevated levels of oxLDL increase recruitment and adherence of monocytes to activated endothelial cells by increasing expression of adhesion molecules and proinflammatory cytokines.59 These monocytes then transmigrate to the arterial intima, taking up oxLDL and eventually maturing to form foam cells.

PON enzymes also play a critical role in the antioxidant functions of HDL. Among the PON enzymes, PON-1 is the major antioxidant in HDL and prevents LDL from oxidation, thereby eliminating biologically active oxLDL.60 SLE patients have reduced PON-1 activity8,16,34,35,61 and this correlates with the loss in antioxidative function of HDL.16 While the reasons for the loss in PON-1 activity are not fully understood, levels of various autoantibodies inversely correlate with PON-1 activity. These include IgG against apoA-I7,16,34, HDL34,35, and β2-glycoprotein I35, suggesting that autoantibodies may contribute to the decreased activity of PON-1. In addition to PON-1, PON-3, another member of the PON enzymes, is decreased in SLE patients with subclinical atherosclerosis, potentially promoting the loss of antioxidant ability of HDL in SLE (Figure 1).62

5. Formation of Autoantibodies in SLE

The production of autoantibodies is the key manifestation of SLE. In patients affected by autoimmune disorders, highly reactive IgG antibodies against human apoA-I are detected and can bind to both lipid-free apoA-I as well as apoA-I on HDL particles.34 It was reported that 32.5% of SLE individuals tested positively for the presence of anti-apoA-I autoantibodies in association with decreased levels of HDL.63 Similar studies have confirmed the presence of anti-apoA-I and its association with higher disease activity in SLE patients.34,64,65 In comparison, only 1% of healthy individuals and 20% of acute coronary syndrome patients without an autoimmune disorder have detectable levels of anti-apoA-I.66 Presence of anti-apoA-I is described to reduce the activity of PON, leading to increased LDL oxidation.34,35 Likewise, in lupus-prone murine models, anti-apoA-I was associated with decreased levels of HDL-C and PON-1 activity.34

We hypothesize that increased levels of anti-apoA-I in SLE patients correlates with increased lipid-free apoA-I and oxidized free apoA-I. Lipid-free apoA-I can exist in plasma via several pathways, either due to de novo synthesis or dissociation from HDL due to displacement by elevated levels of SAA. In addition, oxidation of apoA-I at the Met-148 position leads to conformational changes in the protein.67 Oxidation of apoA-I favors protein misfolding from the native α-helical structure to β-sheets, facilitating dissociation of apoA-I from HDL particles and initiating apoA-I amyloid fibril formation.41 Thus, in SLE plasma and in the oxidative microenvironment associated with NETs and atherosclerosis, the levels of structurally modified apoA-I are likely to be elevated, leading to higher levels of lipid-free misfolded protein (Figure 2). Indeed, HDL isolated from SLE patients, the median levels of 3-nitrotyrosine and 3-chlorotyrosine were 1.9- and 120.9-fold higher than those from healthy controls.39 The misfolded and oxidized apoA-I protein is likely more immunogenic, thus, leading to higher titers of anti-apoA-I in SLE.

Anti-HDL antibodies have been recently reported in SLE patients. The differences between anti-HDL antibodies and anti-apoA-I antibodies remain unclear.34,63 To measure antibody titers in serum, ELISA plates are most commonly coated with lipid-free apoA-I. However, in some instances, the entire HDL particle is used in the assay. It is possible that HDL used in the assay is partially oxidized and antibodies present in SLE patients serum recognize either oxidized or partially misfolded apoA-I that remains to be lipid-bound in HDL particles.68 A few studies have reported significantly elevated levels of anti-HDL in SLE compared to both healthy subjects or patients with the primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).69,70 High anti-HDL titers were associated with increased SLE disease activity markers and decreased PON activity, which could lead to loss of antioxidant and atheroprotective functions of HDL and promotion of atherosclerosis development.8,34,62

6. Applications of HDL therapeutics

Reconstituted HDL (rHDL), nanoparticles prepared from apoA-I or apoA-I mimetic peptides following reconstitution with phospholipids, have been extensively studied as an anti-atherosclerosis therapeutics since 1984.71 Infusions of rHDL have shown to increase levels of circulating HDL, improve plasma cholesterol efflux capacity, inhibit synthesis of proinflammatory mediators, and improve endothelial function leading to increased overall atheroprotection in animal models and in clinical trials.72 As of today, six different rHDL products have been tested in clinical trials, including SRC-rHDL, CSL-111, ETC-216, ETC-642, CER-001 and CSL-112. Two products, ETC-216 and CSL-111, were shown to reduce plaque burden in CVD patients as assessed by intravascular ultrasound.73,74 CSL-112, a newer formulation of CSL-111, exhibited improved clinical safety and cholesterol efflux capacity in healthy volunteers compared to CSL-111.75 A 17,400 patients phase 3 study to explore the ability of CSL-112 to reduce major adverse cardiovascular events in CVD patients is currently ongoing.76

HDL therapy has also presented beneficial effects on inflammatory disorders such as sepsis. It can neutralize endotoxin from bacteria, regulate the inflammatory response in macrophages, and inhibit endothelial cell activation in sepsis.77 As a result, infusion of CSL-111 suppressed proinflammatory cytokine production, sepsis-induced hypotension, and reduced the severity of clinical symptoms.78 Similarly, L-4F, an apoA-I mimetic peptide, demonstrated a beneficial effect in studies of various animal sepsis models by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokine production, reducing sepsis-induced hypotension, protecting against organ damage, and increasing survival rate.79,80 Charles-Schoeman et al. have proposed a possible therapy with apoA-I mimetic peptides in collagen-induced arthritis, a rodent model of rheumatoid arthritis.81 Rats treated with combination therapy of apoA-I mimetic peptides, D-4F, and pravastatin showed significantly improved clinical severity score and less erosive disease compared to both non-combination and control groups. Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were notably reduced with combination therapy as well as improving anti-inflammatory properties of HDL.

6.1. Use of apoA-I mimetic peptides and rHDL in SLE animal models

To date, very few studies have tested the putative benefit of HDL treatment in SLE animal models. A study by Woo et al. showed significant improvements in SLE manifestations in a murine lupus model associated with accelerated atherosclerosis via treatment of apoA-I mimetic peptide, L-4F, alone or with pravastatin.82 Notably, treatment with L-4F alone or with pravastatin significantly reduced IgG anti-dsDNA, IgG anti-oxidized phospholipids, proteinuria, glomerulonephritis, and osteopenia. L-4F also improved the anti-inflammatory functions of plasma HDL while reducing pro-inflammatory effects of LDL. In a more recent study from Black et al., increased levels of apoA-I resulted in suppression of lymphocyte activation, IgG anti-dsDNA autoantibodies, interferon- γ (IFNγ)-secreting CD4+ Th1 cells, and follicular T helper cells, along with improved glomerulonephritis in normocholesterolemic murine SLE.83 Smith et al. investigated whether rHDL can reverse the proinflammatory effects of lupus HDL by using ETC-642, an HDL mimetic composed of apoA-I mimetic peptide (ESP24218) and phospholipid complex administered in vivo to the NZM2328 lupus mouse model.56 Indeed, macrophages exposed to a 1:4 SLE HDL: ETC-642 ratio significantly suppressed TNF-α, IL-6, and NF-kB activation while promoting ATF3 nuclear translocation, suggesting that rHDL can successfully mimic the effects of healthy HDL. The therapy led to significant increases in Atf-3 expression and lowered IL-6 levels in serum, indicating that rHDL can also decrease cytokine synthesis.

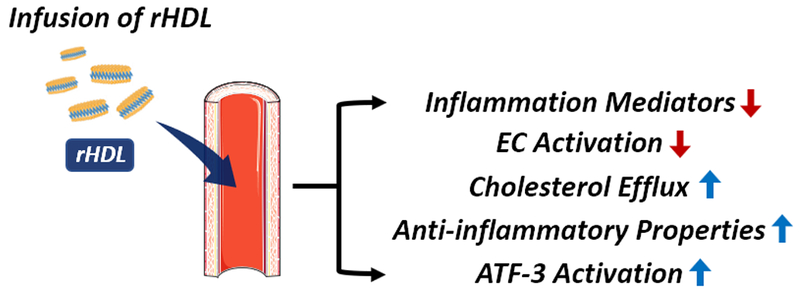

6.2. Future directions for rHDL therapy in SLE with CVD

Underscoring the fact that dysfunctional HDL may promote CVD in SLE, HDL therapy may serve as the potential therapeutic because it can restore both the quantity and quality of HDL. It is worth noting that rHDL and naked apoA-I mimetic peptides used in previous studies have not been optimized for CVD prevention and treatment trials in SLE, as they primarily focused on maximizing the efficacy of cholesterol efflux. Therefore, the potential benefit of rHDL therapy for CVD prevention and treatment in SLE patients remains unclear. An advantage of rHDL therapy is that it can be further customized to be more disease-specific. We have recently discovered that the lipid component of HDL can significantly alter cholesterol efflux capacity and anti-inflammatory properties of HDL.84 Therefore, further investigations to understand the protective roles of rHDL in SLE with CVD are required and will advise optimization of the rHDL composition. Administration of optimized rHDL in SLE models would likely increase the level of pre-β-HDL and may restore the anti-inflammatory functions of HDL, reduce piHDL and oxLDL. Improved and restored HDL may then exert its diverse protective mechanisms including the reduction of inflammatory mediators and activation of endothelial cells, all whilst improving cholesterol efflux capacity (Figure 3). In addition, prevention of autoantibody recognition may be possible in rHDL therapy via altering protein/peptide composition. These observations suggest that HDL mimetics may serve as an effective strategy with low toxicity potential for reducing CVD risk and, potentially, disease activity in SLE.

Figure 3.

Reconstituted HDL (rHDL) as a putative therapeutic strategy in SLE patients at risk for CVD. Infusion of rHDL in SLE may increase the level of preβ-HDL, reduce the presence of inflammatory mediators and activation of endothelial cells, enhance anti-inflammatory properties, ATF-3 activation, and facilitate cholesterol efflux capacity.

7. Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by AHA 13SDG17230049, University of Michigan College of Pharmacy Upjohn Award, Mcubed, NIH R01 GM113832, R01 HL134569, the Intramural Research Program at NIAMS (ZIA AR041199) and by the Lupus Research Institute. Minzhi Yu was supported by AHA 19PRE34400017. Emily E. Morin was supported by the Cellular Biotechnology Training Program (T32 GM008353) and Translational Cardiovascular Research and Entrepreneurship Training Grant (T32 HL125242).

Footnotes

There are no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

8. References

- 1.Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Tom BDM, Ibañez D & Farewell VT Changing patterns in mortality and disease outcomes for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol 35, 2152–8 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernatsky S et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 2550–2557 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal S, Elliott JR & Manzi S Atherosclerosis risk factors in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep 11, 241–247 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerang K, Gilboe I-M, Steinar Thelle D & Gran JT Mortality and years of potential life loss in systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort study. Lupus 23, 1546–1552 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besler C, Lüscher TF & Landmesser U Molecular mechanisms of vascular effects of High-density lipoprotein: alterations in cardiovascular disease. EMBO Mol. Med 4, 251–68 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon M et al. Dysfunctional proinflammatory high-density lipoproteins confer increased risk of atherosclerosis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 2428–2437 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava R, Yu S, Parks BW, Black LL & Kabarowski JH Autoimmune-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and paraoxonase 1 activity in systemic lupus erythematosus-prone gld mice. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 201–211 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiss E et al. Reduced paraoxonase1 activity is a risk for atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1108, 83–91 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontush A et al. Structure of HDL: particle subclasses and molecular components. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol 224, 3–51 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kontush A, Lhomme M & Chapman MJ Unraveling the complexities of the HDL lipidome. J. Lipid Res 54, 2950–63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenson RS et al. HDL measures, particle heterogeneity, proposed nomenclature, and relation to atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. Clin. Chem 57, 392–410 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matyus SP et al. HDL particle number measured on the Vantera®, the first clinical NMR analyzer. Clin. Biochem 48, 148–155 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lilleby V et al. Body composition, lipid and lipoprotein levels in childhood‐onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand. J. Rheumatol 36, 40–47 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soep JB, Mietus-Snyder M, Malloy MJ, Witztum JL & Von Scheven E Assessment of atherosclerotic risk factors and endothelial function in children and young adults with pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) (2004). doi: 10.1002/art.20392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan J, Li LI, Wang Z, Song W & Zhang Z Dyslipidemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Association with disease activity and B-type natriuretic peptide levels. Biomed. reports 4, 68–72 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal K et al. High-density lipopoprotein antioxidant capacity, subpopulation distribution and paraoxonase-1 activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lipids Health Dis. 15, 60 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toloza SMA et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA): XXIII. Baseline predictors of vascular events. Arthritis Rheum. (2004). doi: 10.1002/art.20622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gamal SM et al. Immunological profile and dyslipidemia in Egyptian Systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Egypt. Rheumatol (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.ejr.2016.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung CP et al. Lipoprotein subclasses and particle size determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 27, 1227–1233 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wijaya LK, Kasjmir YI, Sukmana N, Subekti I & Prihartono J The proportion of dyslipidemia in systemic lupus erythematosus patient and distribution of correlated factors. Acta Med Indones (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashef S, Ghaedian MM, Rajaee A & Ghaderi A Dyslipoproteinemia during the active course of systemic lupus erythematosus in association with anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies. Rheumatol. Int 27, 235–41 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarkissian T, Beyenne J, Feldman B, Adeli K & Silverman E The complex nature of the interaction between disease activity and therapy on the lipid profile in patients with pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. (2006). doi: 10.1002/art.21748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardoso CR, Signorelli FV, Papi JA & Salles GF Prevalence and factors associated with dyslipoproteinemias in Brazilian systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Rheumatol Int 28, 323–327 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durcan L et al. Longitudinal evaluation of lipoprotein variables in systemic lupus erythematosus reveals adverse changes with disease activity and prednisone and more favorable profiles with hydroxychloroquine therapy. J. Rheumatol (2016). doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schanberg LE et al. Use of atorvastatin in systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Arthritis Rheum. (2012). doi: 10.1002/art.30645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petri MA, Kiani AN, Post W, Christopher-Stine L & Magder LS Lupus Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (LAPS). Ann. Rheum. Dis (2011). doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.136762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua X et al. Dyslipidaemia and lipoprotein pattern in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and SLE-related cardiovascular disease. Scand J Rheumatol 38, 184–189 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juárez-Rojas J et al. High-density lipoproteins are abnormal in young women with uncomplicated systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 17, 981–987 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Formiga F et al. Lipid and lipoprotein levels in premenopausal systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus 10, 359–363 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kontush A HDL particle number and size as predictors of cardiovascular disease. Front. Pharmacol 6, 218 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machado D et al. Lipid profile among girls with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol. Int 37, 43–48 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah D, Mahajan N, Sah S, Nath SK & Paudyal B Oxidative stress and its biomarkers in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Biomed. Sci 21, 1–13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han CY et al. Serum amyloid A impairs the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. J Clin Invest 126, 796 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batuca JR et al. Anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory properties of high-density lipoprotein are affected by specific antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 48, 26–31 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delgado Alves J et al. Antibodies to high-density lipoprotein and β2-glycoprotein I are inversely correlated with paraoxonase activity in systemic lupus erythematosus and primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 2686–94 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.G HB, Rao VS & Kakkar VV Friend Turns Foe: Transformation of Anti-Inflammatory HDL to Proinflammatory HDL during Acute-Phase Response. Cholesterol 2011, 274629 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Lenten BJ et al. High-density lipoprotein loses its anti-inflammatory properties during acute influenza a infection. Circulation 103, 2283–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMahon M et al. Proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein as a biomarker for atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 2541–2549 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CK et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap-derived enzymes oxidize high-density lipoprotein: an additional proatherogenic mechanism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 66, 2532–2544 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heinecke JW The role of myeloperoxidase in HDL oxidation and atherogenesis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 9, 249–251 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan GKL et al. Myeloperoxidase-mediated Methionine Oxidation Promotes an Amyloidogenic Outcome for Apolipoprotein A-I. J. Biol. Chem 290, 10958–71 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leffler J et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps that are not degraded in systemic lupus erythematosus activate complement exacerbating the disease. J Immunol 188, 3522–3531 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlucci PM et al. Neutrophil subsets and their gene signature associate with vascular inflammation and coronary atherosclerosis in lupus. JCI Insight 3, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vivekanandan-Giri A et al. High density lipoprotein is targeted for oxidation by myeloperoxidase in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72, 1725–1731 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szapacs ME, Kim HYH, Porter NA & Liebler DC Identification of proteins adducted by lipid peroxidation products in plasma and modifications of apolipoprotein A1 with a novel biotinylated phospholipid probe. J. Proteome Res 7, 4237–4246 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hahn BH, Grossman J, Ansell BJ, Skaggs BJ & McMahon M Altered lipoprotein metabolism in chronic inflammatory states: proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein and accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther 10, 213 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang X & Chen F The effect of lipid peroxides and superoxide dismutase on systemic lupus erythematosus: a preliminary study. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 63, 39–44 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Artl A et al. Impaired capacity of acute-phase high density lipoprotein particles to deliver cholesteryl ester to the human HUH-7 hepatoma cell line. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 34, 370–81 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bergt C et al. The myeloperoxidase product hypochlorous acid oxidizes HDL in the human artery wall and impairs ABCA1-dependent cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 13032–13037 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shao B et al. Myeloperoxidase impairs ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux through methionine oxidation and site-specific tyrosine chlorination of apolipoprotein A-I. J. Biol. Chem 281, 9001–9004 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shao B, Cavigiolio G, Brot N, Oda MN & Heinecke JW Methionine oxidation impairs reverse cholesterol transport by apolipoprotein A-I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 12224–9 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saemann MD et al. The versatility of HDL: a crucial anti-inflammatory regulator. Eur J Clin Invest 40, 1131–1143 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Nardo D et al. High-density lipoprotein mediates anti-inflammatory reprogramming of macrophages via the transcriptional regulator ATF3. Nat. Immunol 15, 152–60 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin K et al. Apolipoprotein A-I inhibits CD40 proinflammatory signaling via ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated modulation of lipid raft in macrophages. J Atheroscler Thromb 19, 823–836 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parra S et al. Complement system and small HDL particles are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in SLE patients. Atherosclerosis 225, 224–230 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith CK et al. Lupus high-density lipoprotein induces proinflammatory responses in macrophages by binding lectin-like oxidised low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 and failing to promote activating transcription factor 3 activity. Ann. Rheum. Dis annrheumdis-2016–209683 (2016). doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skaggs BJ, Hahn BH, Sahakian L, Grossman J & McMahon M Dysfunctional, pro-inflammatory HDL directly upregulates monocyte PDGFRbeta, chemotaxis and TNFalpha production. Clin Immunol 137, 147–156 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frostegård J et al. Lipid peroxidation is enhanced in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and is associated with arterial and renal disease manifestations. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 192–200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansson GK & Libby P The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6, 508–519 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hahn BBH et al. Altered lipoprotein metabolism in chronic inflammatory states: proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein and accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther 10, 213 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tripi LM et al. Relationship of serum paraoxonase 1 activity and paraoxonase 1 genotype to risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 54, 1928–1939 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marsillach J et al. Paraoxonase-3 is depleted from the high-density lipoproteins of autoimmune disease patients with subclinical atherosclerosis. J Proteome Res 14, 2046–2054 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dinu ARR et al. Frequency of antibodies to the cholesterol transport protein apolipoprotein A1 in patients with SLE. Lupus 7, 355–360 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Neill SG et al. Antibodies to apolipoprotein A-I, high-density lipoprotein, and C-reactive protein are associated with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 845–854 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shoenfeld Y et al. Autoantibodies against protective molecules--C1q, C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P, mannose-binding lectin, and apolipoprotein A1: prevalence in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1108, 227–39 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vuilleumier N et al. Presence of autoantibodies to apolipoprotein A-1 in patients with acute coronary syndrome further links autoimmunity to cardiovascular disease. J. Autoimmun 23, 353–360 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Townsend D et al. Heparin and Methionine Oxidation Promote the Formation of Apolipoprotein A-I Amyloid Comprising α-Helical and β-Sheet Structures. Biochemistry 56, 1632–1644 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN & Bobryshev YV ApoA1 and ApoA1-specific self-antibodies in cardiovascular disease. Lab. Investig 96, 708–718 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Delgado Alves J, Kumar S & Isenberg DA Cross-reactivity between anti-cardiolipin, anti-high-density lipoprotein and anti-apolipoprotein A-I IgG antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology 42, 893–899 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Batuca JR, Ames PR, Isenberg DA & Alves JD Antibodies toward high-density lipoprotein components inhibit paraoxonase activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1108, 137–146 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orekhov AN et al. ARTIFICIAL HDL AS AN ANTI-ATHEROSCLEROTIC DRUG. Lancet 324, 1149–1150 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krause BR & Remaley AT Reconstituted HDL for the acute treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Curr. Opin. Lipidol 24, 480–486 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tardif J-C et al. Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297, 1675–82 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nissen SE et al. Effect of Recombinant ApoA-I Milano on Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes. JAMA 290, 2292 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tricoci P et al. Infusion of Reconstituted High‐Density Lipoprotein, CSL112, in Patients With Atherosclerosis: Safety and Pharmacokinetic Results From a Phase 2a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc 4, e002171 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Identifier: , Study to Investigate CSL112 in Subjects With Acute Coronary Syndrome (AEGIS-II); March 21, 2018. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03473223. (Accessed: 17th December 2018)

- 77.Morin EE, Guo L, Schwendeman A & Li XA HDL in sepsis - risk factor and therapeutic approach. Front. Pharmacol 6, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pajkrt D et al. Antiinflammatory effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein during human endotoxemia. J. Exp. Med 184, 1601–8 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Z et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide treatment inhibits inflammatory responses and improves survival in septic rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 297, H866–H873 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moreira RS et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide 4F attenuates kidney injury, heart injury, and endothelial dysfunction in sepsis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 307, R514–24 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Charles-Schoeman C et al. Treatment with an apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic peptide in combination with pravastatin inhibits collagen-induced arthritis. Clin. Immunol 127, 234–244 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woo JM et al. Treatment with apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic peptide reduces lupus-like manifestations in a murine lupus model of accelerated atherosclerosis. Arthritis Res. Ther 12, R93 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Black LL et al. Cholesterol-Independent Suppression of Lymphocyte Activation, Autoimmunity, and Glomerulonephritis by Apolipoprotein A-I in Normocholesterolemic Lupus-Prone Mice. J. Immunol 195, 4685–4698 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schwendeman A et al. The effect of phospholipid composition of reconstituted HDL on its cholesterol efflux and anti-inflammatory properties. J. Lipid Res 56, 1727–37 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]