Abstract

Background

Commercial genetic testing for Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) has rapidly expanded, but the inability to accurately predict whether a rare variant is pathogenic has limited its clinical benefit. Novel missense variants are routinely reported as “Variant of Unknown Significance (VUS)” and cannot be used to screen family members at-risk for sudden cardiac death. Better approaches to determine pathogenicity of VUS are needed.

Objective

To rapidly determine the pathogenicity of a CACNA1C variant reported by commercial genetic testing as a VUS using a patient-independent induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) model.

Methods

Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, CACNA1C-p.N639T was introduced into a previously-established hiPSC from an unrelated healthy volunteer, thereby generating a patient-independent hiPSC model. Three independent heterozygous N639T hiPSC lines were generated and differentiated into cardiomyocytes (CM). Electrophysiological properties of N639T hiPSC-CM were compared to those of isogenic and population control hiPSC-CM by measuring the extracellular field potential (EFP) of 96-well hiPSC-CM monolayers, and by patch-clamp.

Results

Significant EFP prolongation was observed only in optically-stimulated but not in spontaneously-beating N639T hiPSC-CM. Patch clamp studies revealed that N639T prolonged the ventricular action potential by slowing voltage-dependent inactivation of Cav1.2 currents. Heterologous expression studies confirmed the effect of N639T on Cav1.2 inactivation.

Conclusion

The patient-independent hiPSC model enabled rapid generation of functional data to support reclassification of a CACNA1C VUS to “likely pathogenic”, thereby establishing a novel LQTS type 8 mutation. Furthermore, our results indicate the importance of controlling beating rates to evaluate functional significance of LQTS VUS in high-throughput hiPSC-CM assays.

Keywords: human induced pluripotent stem cells, long QT type 8, extracellular field potential, action potential, L-type Ca current

Introduction

Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a major cause for sudden death in the young.1 Most cases of LQTS are caused by mutations in genes encoding cardiac ion channels or their regulatory proteins.2 Currently, expert consensus guidelines predicate diagnosis upon clinical criteria and/or the presence of an unequivocally pathogenic mutation.3 Unfortunately, clinical experience with routine genetic testing has exposed difficulties to correctly classify genetic variants as disease-causing. The designation of a genetic variant as pathogenic is currently based on the 2015 criteria from the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG), combining data from population frequency analyses, in-silico models, and functional studies with cosegregation, allelic, and de novo data.4 The increasing use of genetic testing in clinical care has led to a large increase in variants classified as “of Unknown Significance” (VUS).5

Heterologous expression studies are commonly used for ascertaining the functional relevance of genetic variants identified in LQTS patients.6 However, their efficacy is limited because effects on the ventricular action potential cannot be evaluated due to the non-cardiomyocyte physiology of the cellular expression systems, at times leading to mis-classification of variants.7 The human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology has enabled the field to generate human cardiomyocytes in culture, and several groups have used hiPSC to model genotype-positive LQTS.8 A recent study suggests using patient-derived hiPSC also to evaluate pathogenicity of VUS in LQTS.9 However, using patient-derived hiPSC is slow and costly because it requires access to patient cells, generation of new hiPSC lines, as well as genome editing to correct the VUS.

Here, we report a cheaper and more rapid hiPSC approach for evaluating LQTS VUS - the patient-independent hiPSC model: We utilized genomic editing of a previously-established normal hiPSC line to investigate a novel heterozygous CACNA1C variant – N639T – found in a female proband with a prolonged QT interval. Mutations in CACNA1C, the gene encoding the L-type Ca channel CaV1.2, are among the rare causes of LQTS. A major commercial genetic testing laboratory, in agreement with the current ACMG interpretation criteria,4 reported N639T as a “VUS”. We found that cardiomyocytes (CM) derived from N639T hiPSC exhibit prolonged ventricular repolarization, likely caused by an impaired voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2. Our results not only establish N639T as a novel LQT8 mutation, but also demonstrate the utility of the patient-independent hiPSC model for rapidly establishing the pathogenicity of LQTS genetic variants.

Methods

For an expanded Methods section, see the Supplemental Data.

Generation and characterization of a patient-independent hiPSC model

Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, heterozygous CACNA1C-p.N639T was introduced into a previously-established and validated normal hiPSC line10 and differentiated into cardiomyocytes (CM) as described.10 Electrophysiological properties of N639T hiPSC-CM were characterized by measuring extracellular field potentials (EFP) in 96-well hiPSC-CM monolayers,10 and by standard patch-clamp.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism v7 was utilized for testing statistical differences with Mann-Whitney test, Welch’s t-test, and ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean±SEM. Analyses were conducted in a blinded fashion.

Results

Clinical evaluation of LQTS proband and kindred

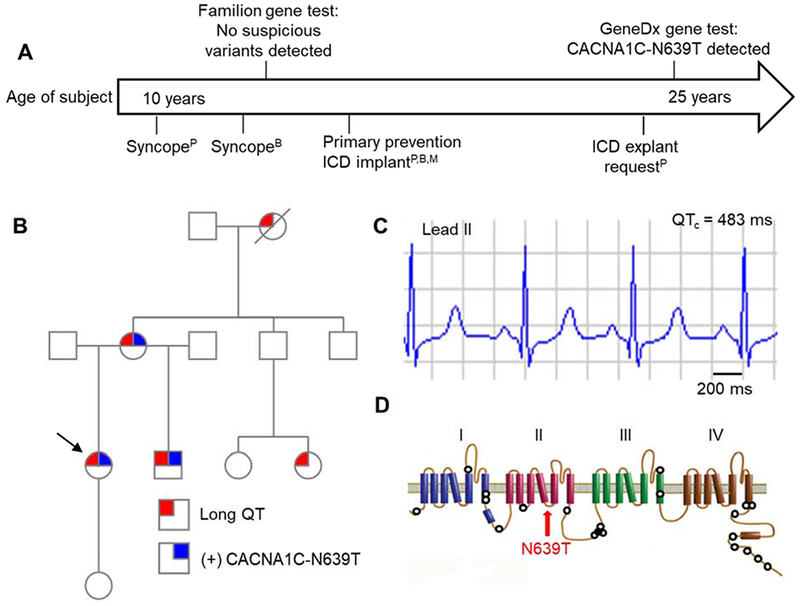

The proband presented at age 10 following 2 sudden, unprovoked, syncopal episodes that occurred while at rest. She had multiple ECG’s with a QTc >480 ms and she met clinical diagnostic criteria for LQTS. Subsequently, her mother and brother were both found to be phenotype positive for LQTS. In 2007, sequencing of KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A demonstrated no suspicious variants. The family pedigree and clinical presentation are summarized in Fig. 1A–C. In 2016, commercial genetic testing with a LQTS gene panel identified a heterozygous missense mutation in CACNA1C (c.A1916C; p.N639T) and reported as a VUS. Her mother and brother also carry the VUS. (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, her mother was born with syndactyly that was surgically corrected during early childhood; this is a typical manifestation of Timothy Syndrome, LQTS type 8 due to CACNA1C mutations. Although all 3 affected individuals exhibited LQTS-like phenotype with one carrier showing syndactyly, the level of probability was insufficient to qualify the variant as being associated with LQTS in this family: The LOD score was only 0.3, calculated using only individuals with known genotypes and assuming a dominant model and a disease frequency of 1 in 2000. LOD scores of 3 or higher are considered highly suggestive.11

Figure 1. CACNA1C VUS in kindred with prolonged QT.

(A) Timeline of clinical events for proband (P), brother (B), and mother (M). Time-scale relative to proband’s age at the time of event. (B) Family pedigree. Arrow denotes proband, circles denote female, squares denote male; diagonal line denotes decedent. (C) Lead II from 12-lead ECG obtained from proband. QT rate-corrected with Bazett formula (QTc). (D) Protein topology map of CaV1.2 encoded by CACNA1C. Hollow circles represent mutation sites previously reported to prolong QT interval. Red arrow indicates localization of N639T. No LQTS mutations have previously been reported in this region.

The CACNA1C-N639T variant localizes intracellularly between the 4th and 5th transmembrane segments of domain II (Fig. 1D). This residue is conserved across CaV1.2 channels (encoded by CACNA1C) as well as CaV2.1. Variation at this site has not been reported in clinical genomic repositories, such as ClinVar and gnomAD. However, the relatively conservative mutation/amino acid change and solvent accessible location of residue 639 when mapped to the rabbit CaV1.1 structure12 do not suggest strong rearrangements in structure. Furthermore, in silico modeling using SIFT, PolyPhen-2, PredictSNP, GPS, and PhosphoPredict suggested no obvious impact on protein function. Hence, CACNA1C-N639T was classified as a VUS (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of CACNA1C-N639T.

American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) classification guidelines4 were implemented using the online Genetic Variant Interpretation Tool23. Due to the in vitro functional evidence in this study, the classification of N639T changed from Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) to Likely Pathogenic.

| ACMG Criterion | Description | Before this study | After this study |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM2 | Absent from controls in large sequencing projects (e.g. gnomAD) | Yes | Yes |

| PP4 | Patient’s phenotype or family history is highly specific for a disease with a single genetic etiology (e.g. Timothy Syndrome) | Yes | Yes |

| BP4 | Multiple lines of computational evidence suggest no impact on gene or gene product | Yes | Yes |

| PS3 | Well-established in vitro or in vivo functional studies supportive of a damaging effect on the gene or gene product | No | Yes |

| Classification | VUS | Likely pathogenic | |

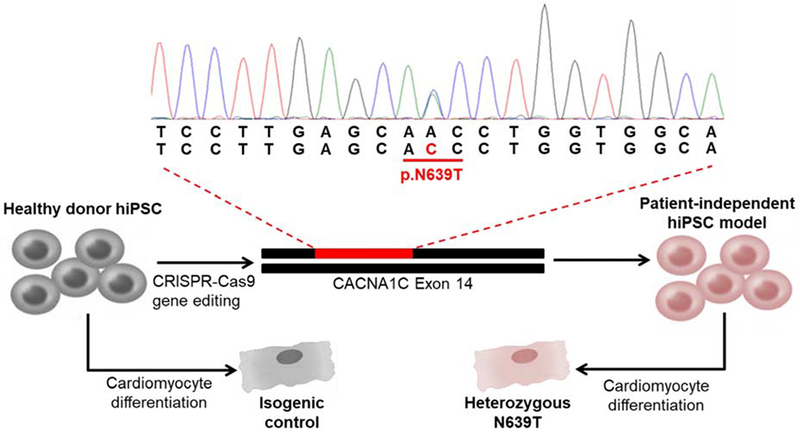

Generation of a patient-independent CACNA1C-N639T hiPSC model

To test the functional significance of CACNA1C-N639T, we used CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing to introduce the heterozygous variant into a previously established and characterized healthy hiPSC line (Fig. 2),13 thereby generating a patient-independent hiPSC model. The healthy hiPSC line, which had been generated from a male volunteer, served as the isogenic control. A second hiPSC line generated from a healthy female donor13 was used as population control. Sanger sequencing confirmed the generation of 3 independent hiPSC lines heterozygous for the mutant N639T allele (supplemental Fig. 1), which were designated as L1, L2 and L3.

Figure 2. Generation of the patient-independent hiPSC-CM model.

Unrelated healthy donor human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) that had been previously generated and characterized were used as starting material. Using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, the c.C1916A variant was introduced into CACNA1C and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This heterozygous missense mutation results in an amino acid substitution from asparagine to threonine at position 639 (pN639T). hiPSC lines were then differentiated to generate N639T mutant CM and isogenic control CM.

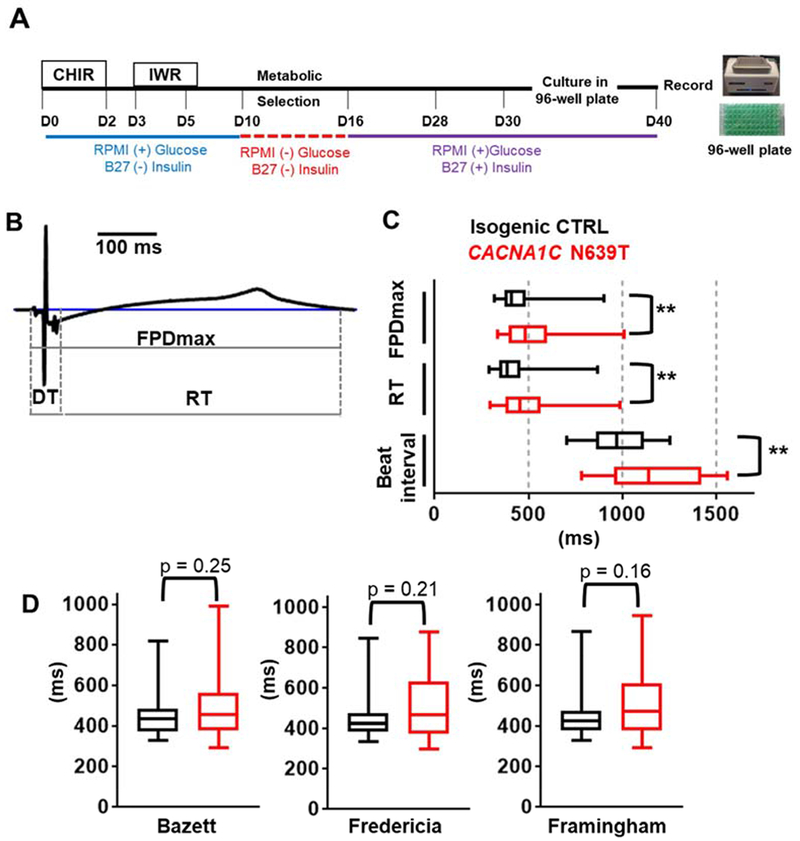

Measurement of extracellular field potentials

To study the effect of N639T on cellular cardiac electrophysiology, CM were generated using a standard small molecule method14 and hiPSC-CM monolayers plated in a 96-well commercial extracellular field potential (EFP) system (CardioExcyte96, Fig. 3A). EFPs were recorded from spontaneously-beating hiPSC-CM monolayers 10 days after plating (L1, hiPSC-CM day 40). The following time-based parameters were analyzed (Fig. 3B): Depolarization Time (DT), Repolarization Time (RT), and Maximum Field Potential Duration (FPDmax). There was no significant difference in DT between N639T and isogenic control (median N639T 28.4 ms, CTRL 27.7 ms, p = 0.85). Both RT and FPDmax measurements were significantly prolonged in N639T compared to isogenic control (Fig. 3C). However, the spontaneous beating rate was significantly slower in N639T hiPSC-CM monolayers (longer RR interval, Fig. 3C). Since AP duration and hence FPDmax are rate-dependent, we attempted to rate-correct the FPDmax values using QT rate-correction formulae established in human electrocardiography (Bazett, Fridericia, and Framingham). After rate-correction, the difference in FPDmax between control and N639T hiPSC-CM monolayers was no longer statistically significant.

Figure 3. EFP measurements in spontaneously-beating hiPSC-CM monolayers.

(A) Timeline and experimental reagents for generating human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM). At day 30, hiPSC-CM were plated on 96-well plates and EFP recorded at hiPSC-CM day 40. (B) Representative EFP waveform of spontaneously-beating isogenic control (CTRL) hiPSC-CM. Starting from isoelectric baseline, measurements were obtained for the depolarization time (DT), repolarization time (RT), and maximum field potential duration (FPDmax, defined as the time-point when the EFP waveform returned to isoelectric baseline). (C) Comparison of time-based parameters between N639T and isogenic CTRL hiPSC-CM. N = 48 (CTRL) and 42 (N639T, L1) wells, **p<0.01 (D) Rate-correction of FPDmax using Bazett, Fredericia, and Framingham formulae. Values are plotted as median, interquartile range (box), and range (error bars). All p-values obtained using Mann-Whitney test.

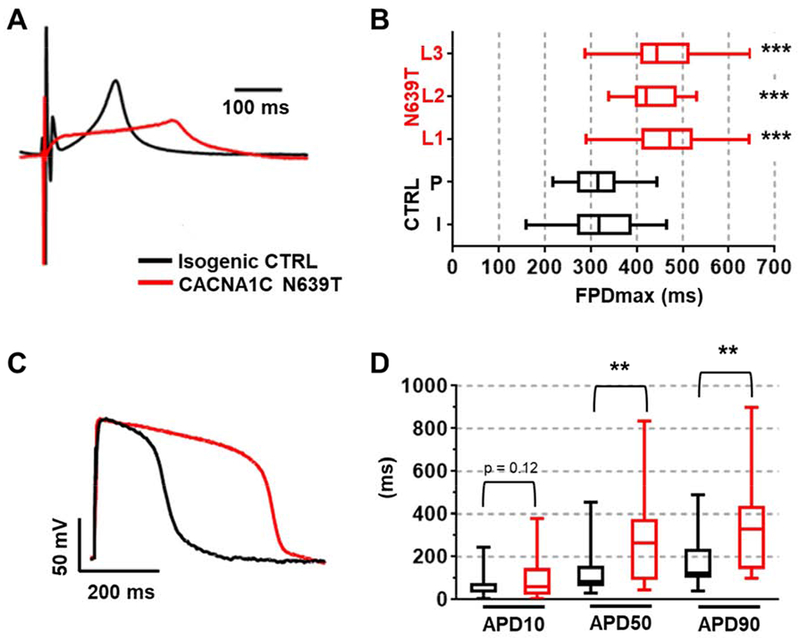

Given that clinical QT-rate correction formulae have not been validated for hiPSC-CM monolayers, we next used the optical stimulation feature of the CardioExcyte96 system to control the beating rate. To enable optical pacing, hiPSC-CM were transduced with AAV1 expressing blue-light activated channelrhodopsin prior to 96-well plating.15 AAV1 titers were optimized to achieve >80% infection rate (supplemental Fig. 2), enabling optical pacing of all virally-transduced wells. Optical pacing significantly reduced the DT (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. 3), likely due to the near-simultaneous activation of hiPSC-CM across the whole monolayer. Since the long QT phenotype is more pronounced at slow heart rates, we used a pacing rate of 60 beats/min (1 Hz) to assess the effect of N639T on FPDmax. Approximately 50% of wells across all groups could be successfully paced at 1 Hz, with intrinsic rates being too high in the remainder. Average FPDmax values were similar in all three N639T mutant lines, and significantly prolonged compared to both the isogenic control line and the population control line (Fig. 4 A&B). Optical pacing also significantly reduced the range of FPDmax values (compare Fig. 3D and Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results indicate that the N639T variant significantly prolongs ventricular repolarization of hiPSC-CM monolayers.

Figure 4. EFP and AP measurements in paced hiPSC-CM.

Representative EFP waveforms (A) and median values (B) for isogenic CTRL and CACNA1C-N639T hiPSC-CM optically paced at 1 Hz. Two control lines: isogenic (I, n=34 wells) and population (P, n=41 wells). Three independently generated heterozygote variant lines: N639T L1 (n=75), N639T L2 (n=13), N639T L3 (n=16). No significant difference between median values for isogenic and population controls (p=0.99). No significant difference between variant lines 1 & 2 (p=0.56), 1 & 3 (p=0.99), and 2 & 3 (p=0.91). ***p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney test compared to both isogenic and population control. (C) Representative AP waveforms of single N639T (L1) and isogenic CTRL hiPSC-CM. (D) AP measurements at 10%, 50%, 90% repolarization (APD10, APD50, APD90). CTRL (n=19) & N639T (n=15), **p < 0.01 by Mann-Whitney test. Range indicated by error bars, interquartile values indicated by box.

Action potential (AP) and L-type Ca current measurements

We next compared AP and Ca currents of single N639T hiPSC-CM (line 1) with that of isogenic control (CTRL) hiPSC-CM (Fig.4C). APs were measured in current clamp mode. Average resting membrane potential was −78 mV in both groups, with no significant differences in cell capacitance, peak amplitude, or time to peak (Supplemental table 1). However, repolarization of N639T hiPSC-CM was prolonged, resulting in significantly longer AP duration at 50% and 90% repolarization compared to CTRL (Fig. 4D).

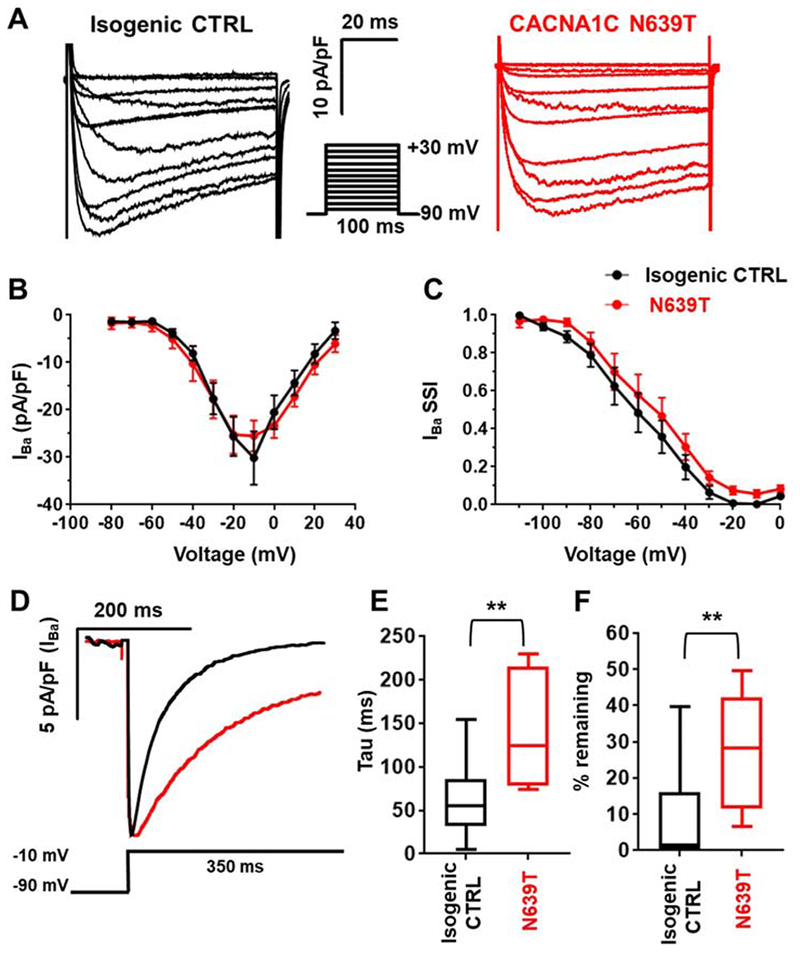

Since LQT8 mutations typically prolong the AP by slowing voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 channels, we examined the L-type Ca current using standard voltage clamp protocols (Fig. 5A).16 Barium was used as a charge carrier to avoid confounding effects due to Ca-dependent inactivation of the channel.16 Maximum CaV1.2 current density and steady-state inactivation were not significantly altered by N639T (Fig. 5B+C). Slope factor and V1/2 were not significantly different between groups (CTRL slope factor 7.4, V1/2 −60 mV; N639T 7.3, −55 mV, p > 0.05); however, CaV1.2 currents inactivated significantly slower in N639T compared to CTRL, resulting in significantly larger currents remaining at the end of the depolarization step (Fig. 5C&D). This result indicates that the CACNA1C-N639T mutation slows CaV1.2 voltage-dependent inactivation, which will result in a net increase in CaV1.2 currents and therefore can explain the AP & EFP prolongation found in N639T hiPSC-CM.

Figure 5. Characterization of CaV1.2 currents in single hiPSC-CM.

(A) Representative current records in response to a step membrane depolarization using Ba2+ as a charge carrier (IBa). (B) Current-voltage relationship for isogenic CTRL (n=12) and N639T (L1, n=10). No significant difference between the two lines was detected (p=0.83, Welch’s t test). (C) Steady-state inactivation curves of isogenic CTRL (n=12) and N639T (L1, n=12). No significant difference between the two lines was detected (p=0.66, Welch’s t test). (D) Representative IBa records in response to a long step depolarization. The declining phase of the trace was fitted by a single-exponential function to calculate inactivation time constant. (E) Time constant of IBa inactivation. (F) %IBa remaining after 350-ms depolarization to −10 mV. CTRL (n=10), N639T (n=8). Range indicated by error bars, interquartile values indicated by box, **p<0.01 by Mann-Whitney test.

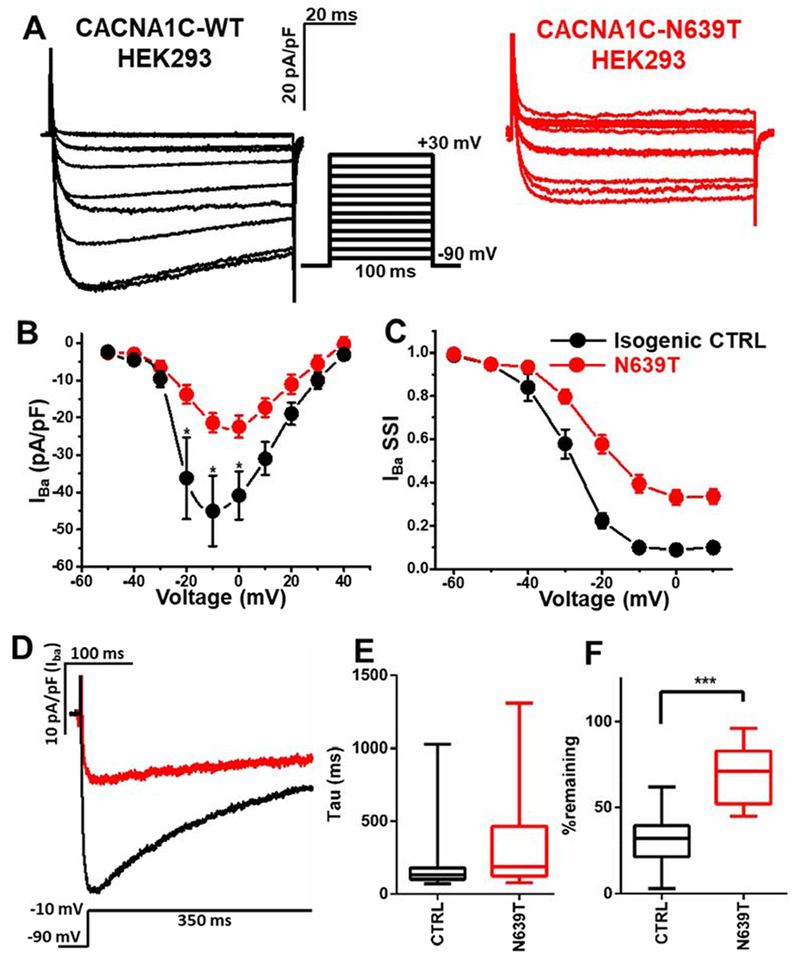

Finally, we studied CACNA1C-N639T using a heterologous expression system. HEK293 cells were transfected using a 1:1:1:1 ratio of the following plasmids 1) Wildtype or N639T pCMV:CACNA1C; 2) pCMV-CACNB2B, 3) pcDNA3.1-CACNA2D1, and 4) pIRES2-EGFPT. Green fluorescent cells were studied 2 days after transfection using voltage-clamp (Fig. 6). Unlike in hiPSC-CM, N639T significantly reduced peak CaV1.2 currents in HEK293 cells (Fig. 6A&B), which could indicate a loss of function that is not consistent with QT prolongation. However, similar to the hiPSC model, N639T HEK293 cells exhibited a significant decrease in the rate of voltage-dependent inactivation (Fig. 6D–F), which would indicate a gain of function. Given that peak CaV1.2 currents were not affected in our human cardiomyocyte model heterozygous for N639T (Fig. 5), we interpret the HEK293 data as supporting the hypothesis that impaired voltage dependent inactivation is the likely molecular mechanism responsible for the QT prolongation of patients carrying the N639T mutation. Adding in the ACMG PS3 criterion (“Well established in vitro or in vivo functional studies support a damaging effect on the gene or gene product”) results in reclassification of N639T from a VUS to likely pathogenic (Table 1).

Figure 6. Characterization of CaV1.2 currents in HEK293 cells.

(A) Representative current records in response to a step membrane depolarization using Ba2+ as a charge carrier (IBa). (B) Current-voltage relationship for control (CTRL, n=17) and N639T (n=14). Peak current density was significantly smaller in N639 group compared to control group (p<0.01, t-test). (C) Steady-state inactivation of CTRL (n=17) and N639T (n=16). V0.5=−30.3±1.5 mV for CTRL vs. −24.5±1.2 mV for N639T (p<0.01). k=4.2±0.3 mV for CTRL vs. 5.2±0.6 mV for N639T (p=0.2). (D) Representative IBa records in response to a long step depolarization. The declining phase of the trace was fitted by a single-exponential function to calculate inactivation time constant. (E) Average time constant of IBa inactivation. (F) %IBa remaining after 350-ms depolarization. CTRL (n=17), N639T (n=17). Range indicated by error bars, interquartile values indicated by box, ***p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney test.

Discussion

Here, we report using a patient-independent hiPSC model to assess the pathogenicity of a novel LQTS gene variant, CACNA1C-N639T, discovered through clinical genetic testing and classified as a VUS. Non-invasive high-throughput recordings indicated that N639T significantly prolongs cardiac repolarization, which was confirmed by single cell action potential data. Our findings of impaired voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 provide a plausible mechanism for QT prolongation. Using ACMG guidelines for the interpretation of sequencing variants,4 the functional data provided by our patient-independent hiPSC-CM model results in reclassification of N639T from a VUS to a likely pathogenic variant (Table 1). According to clinical practice standards for genetic testing, the reclassification of N639T to a likely pathogenic variant now supports its use for targeted genotyping to screen the remaining family members.

Using a patient-independent hiPSC model to rapidly establish VUS pathogenicity

Prior studies of gene variants in inherited arrhythmia syndromes commonly use patient-derived stem cells differentiated into CM and then test them for electrophysiological abnormalities (reviewed in17). A recent report proposed the use of patient-derived hiPSC for also for the evaluation of LQTS VUS,9 but this approach is costly and slow, as explained in detail below. Here, we report a faster and cheaper approach – the patient-independent hiPSC model: We started with a well-characterized hiPSC line previously generated from a healthy volunteer and used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to introduce the genetic variant into hiPSC, ultimately modeling the proband’s electrophysiological phenotype in hiPSC-CM alongside an isogenic control. Ours is the first study using CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce a heterozygous LQTS VUS into isogenic hiPSC, a technique previously validated in hiPSC-CM studies by us13 and others18 using established pathogenic mutations that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The patient-independent hiPSC model has significant advantages over the use of patient-derived hiPSC for testing the pathogenicity of a rare ion channel variant:

(1) Because established and well-characterized hiPSC lines can be used to generate the new patient-independent hiPSC model, no new iPSC lines must be generated and therefore no patient-derived materials are needed. Hence, our approach can also be used for post-mortem evaluation of genetic variants identified during a molecular autopsy.

(2) To demonstrate causality of the genetic variant in patient-derived hiPSC, genomic editing has to be performed to correct the variant and generate isogenic controls for comparison.19 Our approach obviates this second step, resulting in further time and cost savings.

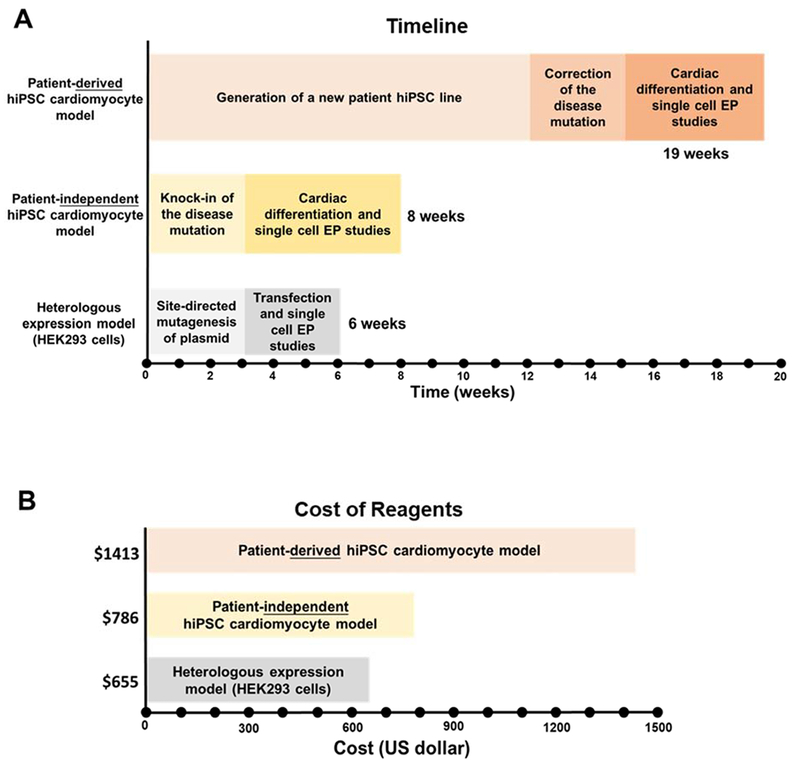

The differences in time and cost of the two hiPSC approaches are summarized in supplemental table 2 and Fig. 7. If patient specimens are available when a VUS is reported on genetic testing, the generation and characterization of a patient-specific hiPSC model requires a minimum of 19 weeks (Fig. 7A). If not, scheduling a patient to obtain a skin biopsy or blood draw will add weeks or even months. In contrast, the generation and characterization of a patient-independent model can be accomplished in 8 weeks based on our experience reported here (Fig. 7A). Cost of reagents to generate and study the patient-derived hiPSC model is also twice more than that of a patient-independent hiPSC model (Fig. 7B). Inclusion of personnel and labor cost would further increases the cost differential. Hence, the patient independent hiPSC models provides significant savings in both money and time compared to the classic patient-derived hiPSC model. Heterologous expression systems, on the other hand, are thought to be even cheaper and faster to develop. But as illustrated in Fig. 7 and supplemental table 2, the time and cost of generating a HEK293 cell model is only modestly less than that of our patient-independent hiPSC model. Moreover, as we demonstrate here, heterologous expression studies may not provide a definitive answer regarding the pathogenicity of the VUS, since N639T-mutant CaV1.2 channels expressed in HEK293 cells exhibited features of both gain of function (impaired voltage-dependent inactivation) and loss of function (reduced peak currents), with the net effect on ventricular repolarization unclear.

Figure 7. Comparison of time (A) and reagent cost (B) to generate and characterize patient-specific hiPSC, patient-independent hiPSC and heterologous expression models.

Listed are estimated minimum times required by a research laboratory experienced in the three approaches. The costs of reagents are based on actual costs to our laboratory based in the United States. The E8 stem cell culture media was prepared in-house, which resulted in significant savings compared to purchasing it commercially.

One limitation of the patient-independent hiPSC model is that a negative result does not prove that a VUS is benign, because the phenotype may not be evident in the different genetic background of an unrelated donor hiPSC line. In this situation, developing a patient-specific hiPSC model with gene-editing to correct the VUS would be essential to determine whether the variant is benign.20

Optical stimulation uncovers repolarization phenotype of N639T hiPSC-CM monolayers

We discovered that N639T hiPSC-CM exhibited a significantly slower spontaneous beating rate (Fig. 3), likely as a result of the AP prolongation and impaired CaV1.2 inactivation (Figs. 4&5). Given the heart rate dependence of ventricular repolarization in humans,21 this finding complicates analysis of EFP duration in the hiPSC-monolayers. Although electrical stimulation has been used to control beating rates of hiPSC-monolayers, the electrical stimulus generates recording artifacts that makes EFP analysis difficult.15 In contrast, optical stimulation is non-toxic, can be carried out continuously in cell culture, and provides a greater degree of temporal and spatial precision of modulation.22 Optical pacing enabled simultaneous CM activation without conduction delay and provided more uniform EFP signals (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. 3), which facilitated FPD analysis and effectively uncovered the repolarization defect caused by N639T.

How does the novel N639T variant compare to previously published LQT8 mutants?

A number of mutation sites in CaV1.2 have been implicated in QT prolongation (supplemental table 2 and Fig. 1D). N639T is unique in its transmembrane segment location, on the amphipathic helix of the S4-5 linker in domain II. CaV1.2 variants previously characterized by in vitro patch clamp (n=15) suggests function-altering mutations most commonly affect current density, activation, and inactivation of the channel; however, nearly all of these studies were performed on heterologous expression models rather than cardiomyocytes. Here, we report that CaV1.2 currents from N639T hiPSC-CM exhibit significantly reduced voltage-dependent inactivation compared to isogenic control hiPSC-CM. Although less severe, the functional defect is analogous to that observed in hiPSC-CM expressing the classic LQT8 mutation (G406R), which also exhibit impaired voltage-dependent CaV1.2 inactivation. Uncovering the specific mechanism resulting in the N639T gain-of-function will require further investigation. However, we speculate that given the conservativeness of the chemical change from N to T, the mechanism could possibly involve an aberrant phosphorylation of the mutant threonine residue.

In summary, we provided functional data to support the reclassification of a CACNA1C VUS to “likely pathogenic”, thereby allowing its use for clinical screening. Furthermore, our results support using unrelated donor hiPSC as a patient-independent hiPSC model to rapidly evaluate the functional significance of VUS identified in LQTS patients. Using high-throughput EFP measurements or traditional patch clamp approaches, functional data can be provided to the health care provider as early as 8 weeks after the VUS is found on genetic testing. Finally, our results demonstrate the importance of controlling beating rates of hiPSC-CM to evaluate effects of LQTS gene variants on cardiac repolarization in high-throughput assays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of funding:

The work was supported in part by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R35HL144980, R01HL124935, U01 HL131911) and the Leducq Foundation (18CVD05). N.V.C. was supported by a PhRMA Foundation Medical Student Grant. S.S.P. was supported by NIGMS T32 GM07347 through the Vanderbilt Medical-Scientist Training Program and NHLBI F30 HL131179. D.J.B. was supported by NINDS T32 NS00749,NHLBI F32 HL140874 and PhRMA Foundation Postdoctoral Award. M.B.S. was supported by K23 HL127704. A.M.G. was supported by F32 HL137385. B.M.K. was supported by R00HL135442.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are no relationships with industry. The authors declare no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tester DJ and Ackerman MJ. Sudden infant death syndrome: how significant are the cardiac channelopathies? Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knollmann BC and Roden DM. A genetic framework for improving arrhythmia therapy. Nature. 2008;451:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, Cho Y, Behr ER, Berul C, Blom N, Brugada J, Chiang CE, Huikuri H, Kannankeril P, Krahn A, Leenhardt A, Moss A, Schwartz PJ, Shimizu W, Tomaselli G and Tracy C. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2013;10:1932–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL and Committee ALQA. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackerman MJ. Genetic purgatory and the cardiac channelopathies: Exposing the variants of uncertain/unknown significance issue. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steffensen AB, Refaat MM, David JP, Mujezinovic A, Calloe K, Wojciak J, Nussbaum RL, Scheinman MM and Schmitt N. High incidence of functional ion-channel abnormalities in a consecutive Long QT cohort with novel missense genetic variants of unknown significance. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang T, Chun YW, Stroud DM, Mosley JD, Knollmann BC, Hong C and Roden DM. Screening for Acute IKr Block Is Insufficient to Detect Torsades de Pointes Liability: Role of Late Sodium Current. Circulation. 2014;130:224–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinnecker D, Goedel A, Dorn T, Dirschinger RJ, Moretti A and Laugwitz KL. Modeling long-QT syndromes with iPS cells. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2013;6:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg P, Oikonomopoulos A, Chen H, Li Y, Lam CK, Sallam K, Perez M, Lux RL, Sanguinetti MC and Wu JC. Genome Editing of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Decipher Cardiac Channelopathy Variant. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;72:62–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Kim K, Parikh S, Cadar AG, Bersell KR, He H, Pinto JR, Kryshtal DO and Knollmann BC. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked mutation in troponin T causes myofibrillar disarray and pro-arrhythmic action potential changes in human iPSC cardiomyocytes. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2018;114:320–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lander E and Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Yan Z, Li Z, Qian X, Lu S, Dong M, Zhou Q and Yan N. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Ca(v)1.1 at 3.6 A resolution. Nature. 2016;537:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Kim K, Parikh S, Cadar AG, Bersell KR, He H, Pinto JR, Kryshtal DO and Knollmann BC. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked mutation in troponin T causes myofibrillar disarray and pro-arrhythmic action potential changes in human iPSC cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;114:320–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ and Palecek SP. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nature protocols. 2013;8:162–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapp H, Bruegmann T, Malan D, Friedrichs S, Kilgus C, Heidsieck A and Sasse P. Frequency-dependent drug screening using optogenetic stimulation of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, Pasca AM, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer J and Dolmetsch RE. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011;471:230–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knollmann BC. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: boutique science or valuable arrhythmia model? Circulation research. 2013;112:969–76; discussion 976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lv W, Qiao L, Petrenko N, Li W, Owens AT, McDermott-Roe C and Musunuru K. Functional Annotation of TNNT2 Variants of Uncertain Significance With Genome-Edited Cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 2018;138:2852–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musunuru K, Sheikh F, Gupta RM, Houser SR, Maher KO, Milan DJ, Terzic A, Wu JC, American Heart Association Council on Functional G, Translational B, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Y, Council on C and Stroke N. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Cardiovascular Disease Modeling and Precision Medicine: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma N, Zhang J, Itzhaki I, Zhang SL, Chen H, Haddad F, Kitani T, Wilson KD, Tian L, Shrestha R, Wu H, Lam CK, Sayed N and Wu JC. Determining the Pathogenicity of a Genomic Variant of Uncertain Significance Using CRISPR/Cas9 and Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Circulation. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, Bengtson JR and Levy D. An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham Heart Study). The American journal of cardiology. 1992;70:797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle PM, Karathanos TV and Trayanova NA. Cardiac Optogenetics: 2018. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:155–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinberger J, Maloney KA, Pollin TI and Jeng LJ. An openly available online tool for implementing the ACMG/AMP standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. Genet Med. 2016;18:1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.