Abstract

BACKGROUND

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a rare and aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with a varied presentation and no pathognomonic findings. Early diagnosis is critical to altering the disease course as early treatment with chemoimmunotherapy is required to prevent a rapidly fatal outcome. Strategies including improved awareness of this clinical entity through publication of cases with unique presentations are essential to prompt consideration of IVLBCL early in the disease workup. Here, we present a case of IVLBCL presenting with altered mental status and systemic organ dysfunction.

CASE SUMMARY

A 61-year-old male patient presented with flu-like symptoms and a high fever. He experienced rapid clinical deterioration with liver, kidney failure, and shock despite rapid antibiotic administration and supportive care. A broad infectious workup was negative. Intracranial imaging revealed nonspecific changes to the corpus callosum suspicious for vasculitis. Renal biopsy was non-diagnostic. After further progression of his symptoms, the family elected to withdraw care and the patient died shortly thereafter. Post-mortem analysis revealed clear multi-organ involvement by IVLBCL, prompting re-examination of the ante-mortem renal biopsy that also identified IVLBCL involvement.

CONCLUSION

IVLBCL is a rare disease. Communication with specialties and early biopsy is critical to establishing the diagnosis and initiating therapy.

Keywords: Intravascular lymphoma, Altered mental status, Case report

Core tip: Early diagnosis is critical to altering the disease course of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL). A triad of B symptoms, organ dysfunction, and an elevated lactate dehydrogenase should prompt consideration of IVLBCL and early biopsy of affected tissues for rapid diagnosis and treatment. Close communication with pathology in cases of suspected IVLBCL is critical in evaluating for this rare and evasive diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The disease is diagnosed by pathologic examination of affected tissue with involvement of neoplastic lymphocytes limited to predominantly small vessel vasculature[1]. The clinical course is often aggressive and the variability in case presentation leads to a diagnostic delay that may impact survival for an otherwise potentially treatable malignancy. Disseminating clinical presentations of IVLBCL is critical to increase awareness of this disease entity to improve rates of early diagnosis. Here we present a case of IVLBCL presenting with fever and mental status changes, and later found to have a markedly elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and multiple organ dysfunction including the kidney and central nervous system that was ultimately diagnosed by post-mortem analysis.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 61-year-old man presented to his local emergency department (ED) with flu-like symptoms and confusion.

History of present illness

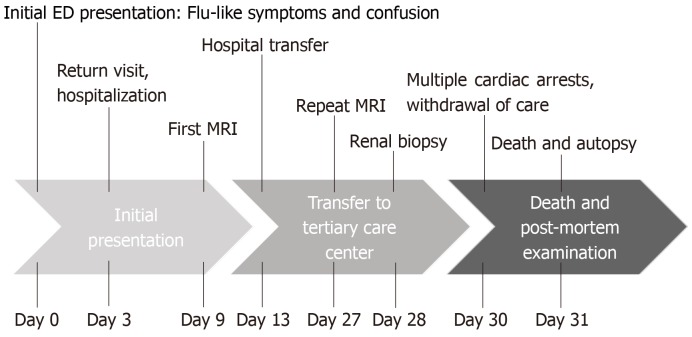

He was diagnosed with pneumonia and received a prescription for doxycycline. Three days later, he returned to the ED with worsening dyspnea, fever to 103 F, hypoxia, and an acute kidney injury with an elevated serum creatinine of 2.22 mg/dL. He was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and admitted to the hospital. The timeline of the case is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Case timeline. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; ED: Emergency department.

History of past illness

His past medical history is notable for alcohol abuse, pulmonary embolism, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Personal and family history

His family history was noncontributory.

Physical examination upon admission

On physical exam, he was oriented to person only and appeared fatigued. His cardiopulmonary exam was unremarkable and there was no lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory examinations

A broad infectious workup including cultures of blood, sputum, and cerebrospinal fluid was initiated. Relevant laboratory information is presented in Table 1, with notable findings of significantly elevated ferritin and LDH.

Table 1.

Laboratory testing results

| Laboratory findings | Values (at transfer) | Reference |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.57 | 0.73-1.18 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.4 | 3.5-5.0 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.9 | 6.4-8.3 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 10.3 | 3.5-8.0 |

| ALT (U/L) | 13 | 0-55 |

| AST (U/L) | 50 | 5.0-34 |

| Bilirubin total (mg/dL) | 0.9 | 0-1.4 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 53 | 40-150 |

| LDH (U/L) | 1519 | 125-220 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 19.7 | 0-1.0 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 2105 | 22-275 |

| WBC (K/μL) | 5.2 | 3.8-10.5 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8 | 13.6-17.2 |

| Platelets (K/μL) | 119 | 160-370 |

Values reported at time of transfer to the tertiary care center. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; WBC: White blood cell count; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Imaging examinations

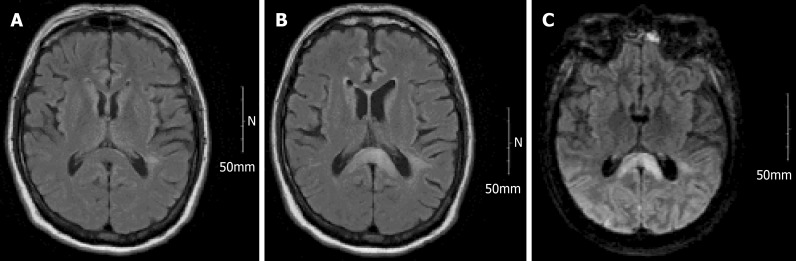

Computed tomography imaging was negative for a pulmonary embolism or infection. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed T2 imaging findings of splenium enhancement within the corpus callosum, also known as the “boomerang sign” (Figure 2). He then developed daily fevers and worsening hematologic parameters including a mild decline in his platelet count, hemoglobin, and white blood cell count. In conjunction with altered mental status, fevers, and new pancytopenia, he was transferred to a tertiary care hospital for further evaluation.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging brain findings. Evolution of central nervous system changes highlighting the corpus callosum involvement and parenchymal abnormalities related to intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. A: Normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) taken August 21, 2017; B: MRI brain 3 m later at presentation revealing splenium enhancement also known as the “boomerang sign[8]”; C: MRI taken 18 d following the MRI shown in B with continued evolution of splenium enhancement as well as progressive parenchymal enhancement posteriorly.

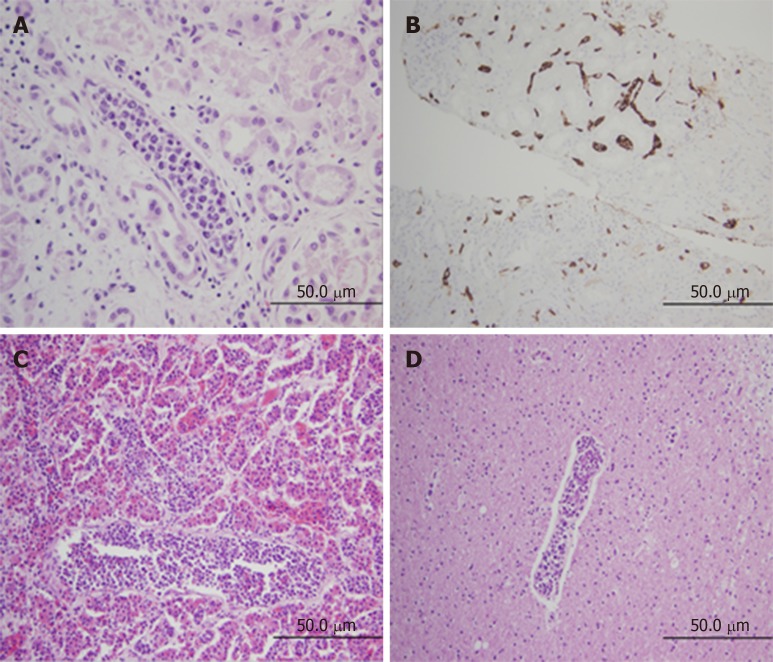

At the time of hospital transfer, he remained persistently febrile up to 40.5 °C with ongoing delirium and mental status changes. He remained on broad spectrum antibiotics, but an extensive infectious work-up was negative. His renal function continued to decline, which prompted initiation of hemodialysis and a renal biopsy. The biopsy revealed findings of diffuse interstitial fibrosis, interstitial inflammation, and acute tubular injury but failed to determine a clear etiology. He underwent a repeat brain MRI, which revealed progressive evolution of changes within white matter structures and the splenium of the corpus callosum with associated vascular changes now suspicious for vasculitis (Figure 2). The rheumatology consultants recommended continued steroids, which had been started empirically for adrenal insufficiency, and hematology evaluation for potential hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. He underwent a bone marrow biopsy that was notable for mild hypercellularity but otherwise negative for dysplasia or malignancy, notably immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for CD20 was not performed. Unfortunately, within a few days of this hospital transfer, the patient suffered multiple cardiac arrests and was transitioned to comfort-based care, and he subsequently died. A post-mortem autopsy was requested which established a diagnosis of IVLBCL as the primary cause of death with extensive multi-organ involvement including but not limited to the brain, kidneys, liver, spleen, and lungs. Diagnosis was confirmed based on microscopic findings revealing extensive parenchymal infiltration and lymphovascular involvement in multiple organs by atypical large lymphoid cells with IHC staining positive for CD20 and negative for CD3, consistent with a B-cell leukemia/lymphoma (Figure 3). No dominant tumor mass or lymphadenopathy was found, consistent with a diagnosis of IVLBCL.

Figure 3.

Histopathologic analysis. A: Post-mortem renal parenchyma high power view demonstrating lymphovascular cells distending the lumen of a vessel lined by epithelial cells (original magnification 40×); B: Immunohistochemical stain from an ante-mortem renal biopsy for CD20+ highlighting lymphocytes restricted to vascular spaces (original magnification 20×); C: Post-mortem pituitary section revealing extensive lymphocyte involvement of lymphovascular spaces (original magnification 20×); D: Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma within cerebral vessels with focal sludging (original magnification 20×).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

IVLBCL.

TREATMENT

Diagnosis made post-mortem, no treatment provided.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Patient died from complications of IVLBCL.

DISCUSSION

Intravascular B-cell lymphoma is recognized by the World Health Organization as a distinct sub-type of mature B cell lymphoma[2]. This disease is diagnosed by pathologic confirmation of neoplastic lymphocytes confined to the lumina of small vessels, predominantly capillaries[1]. IHC stains are typically positive for CD20 and occasionally CD5. The body of clinical literature available on this disease is limited to case reports and retrospective cohort studies, which reflects the rarity of this disease that has an estimated incidence of 1 case per 1 million individuals[3]. IVLBCL is a disease of older adults, with a median age of diagnosis in the late 60’s[4]. Patients in Asian countries frequently present with more bone marrow involvement and B symptoms compared to a Western cohort[1,4]. Importantly, Western populations may present with more central nervous system (CNS) involvement or with a cutaneous variation associated with an improved prognosis[1,5].

As presentations can be subtle and variable, commonly including nonspecific B-symptoms and laboratory abnormalities such as an elevated LDH, the disease is often under-recognized until much later in a disease course, often posthumously. Despite the aggressive nature of this disease, prompt diagnosis is key, as responses can be achieved with standard chemo-immunotherapy regimens, including rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP)[4]. The presence of an elevated LDH and fever often forms a cornerstone to diagnosis as described by Masaki et al[6], where a case series of 16 patients demonstrated that all cases had either fever or an LDH twice the upper limit of normal and only 2 patients lacked the LDH criteria. In this study, the authors suggest that these findings in an elderly patient should prompt consideration of IVLBCL and emphasized that further evaluation including biopsies of affected organs with attention to organ vasculature should be aggressively pursued, as tissue biopsy is almost universally required to establish the diagnosis[6]. In our case, the results from the post-mortem examination confirming IVLBCL prompted testing of the ante-mortem renal biopsy (initially reported as negative) which demonstrated the presence of CD20+ atypical lymphocytes within the vasculature and would have provided the diagnosis. The bone marrow biopsy specimen was not reexamined for CD20+ lymphocytes. Nevertheless, the retrospective IHC analysis on the renal specimen supports the role for IHC staining in cases of diagnostic uncertainty where clear signs of lymphoma or an alternative diagnosis are not evident. On further review with pathology, we determined that closer communication between the specialties including relevant laboratory testing and clinical status might have led to further testing for IVLBCL and potentially yielding an earlier diagnosis and subsequent treatment[6].

CNS presentation and involvement represents a specific challenge, as there are no clear pathognomonic radiographic findings associated with IVLBCL[7]. In our case, we note the combination of mental status changes and MRI abnormalities including the “boomerang” sign noted above. Although the boomerang sign has not been previously correlated with cases of lymphoma[8,9], the limited differential diagnosis of this radiographic finding would have warranted early consideration for brain biopsy.

Diagnostic accuracy is improved when biopsies are performed on affected organs. Reports on the diagnostic utility of random skin biopsies as a less invasive alternative demonstrated a lack of sensitivity sufficient to recommend this approach[10,11]. The use of positron emission tomography-imaging in aiding the diagnosis of IVBCL is limited to case reports[12,13]. However, many of these reports note abnormalities leading to additional diagnostic studies that establish a diagnosis of IVLBCL[14,15]. In general, positron emission tomography-imaging alone cannot establish the diagnosis of IVLBCL, further emphasizing importance of early recognition using clinical and laboratory findings and early consideration for diagnostic biopsy.

CONCLUSION

IVLBCL is a rare variant of aggressive mature B-cell lymphoma without clear pathognomonic findings by labs or imaging. The clinical variability in presentation of IVLBCL leads to diagnostic delay, which can profoundly affect survival outcomes for a disease responsive to standard chemoimmunotherapy. Tissue diagnosis should be pursued early in the disease course if IVLBCL is considered in the differential diagnosis. Communication amongst specialties, especially discussion of relevant clinical findings when interpreting pathologic testing, is critical to making a correct diagnosis of a rare disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient and his family for their contributions to this report.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The subject involved in this case report died from complications of his disease and therefore was unable to provide informed consent. A letter was mailed to his next-of-kin describing our intent to submit his case as an anonymous case report, and contact information was provided should the next-of-kin have concerns with publication. We received no such notice.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Peer-review started: March 8, 2019

First decision: April 18, 2019

Article in press: November 17, 2019

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Piccaluga PP S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

Contributor Information

Christopher Robert D’Angelo, Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology/Oncology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, United States.

Kimberly Ku, Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology/Oncology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, United States.

Jessica Gulliver, Department of Pathology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, United States.

Julie Chang, Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology/Oncology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, United States. jc2@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Facchetti F, Mazzucchelli L, Yoshino T, Murase T, Pileri SA, Doglioni C, Zucca E, Cavalli F, Nakamura S. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3168–3173. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuckerman D, Seliem R, Hochberg E. Intravascular lymphoma: the oncologist's "great imitator". Oncologist. 2006;11:496–502. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-5-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murase T, Yamaguchi M, Suzuki R, Okamoto M, Sato Y, Tamaru J, Kojima M, Miura I, Mori N, Yoshino T, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL): a clinicopathologic study of 96 cases with special reference to the immunophenotypic heterogeneity of CD5. Blood. 2007;109:478–485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-021253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brett FM, Chen D, Loftus T, Langan Y, Looby S, Hutchinson S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting clinically as rapidly progressive dementia. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187:319–322. doi: 10.1007/s11845-017-1653-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masaki Y, Dong L, Nakajima A, Iwao H, Miki M, Kurose N, Kinoshita E, Nojima T, Sawaki T, Kawanami T, Tanaka M, Shimoyama K, Kim C, Fukutoku M, Kawabata H, Fukushima T, Hirose Y, Takiguchi T, Konda S, Sugai S, Umehara H. Intravascular large B cell lymphoma: proposed of the strategy for early diagnosis and treatment of patients with rapid deteriorating condition. Int J Hematol. 2009;89:600–610. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nizamutdinov D, Patel NP, Huang JH, Fonkem E. Intravascular Lymphoma in the CNS: Options for Treatment. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017;19:35. doi: 10.1007/s11940-017-0471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malhotra HS, Garg RK, Vidhate MR, Sharma PK. Boomerang sign: Clinical significance of transient lesion in splenium of corpus callosum. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:151–157. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.95005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitsiori A, Nguyen D, Karentzos A, Delavelle J, Vargas MI. The corpus callosum: white matter or terra incognita. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:5–18. doi: 10.1259/bjr/21946513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arai T, Kato Y, Funaki M, Shimamura S, Yokogawa N, Sugii S, Tsuboi R. Three Cases of Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma Detected in a Biopsy of Skin Lesions. Dermatology. 2016;232:185–188. doi: 10.1159/000437363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asada N, Odawara J, Kimura S, Aoki T, Yamakura M, Takeuchi M, Seki R, Tanaka A, Matsue K. Use of random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1525–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(11)61097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino A, Kawada E, Ukita T, Itoh K, Sakamoto H, Fujita K, Mantani N, Kogure T, Tamura J. Usefulness of FDG-PET to diagnose intravascular lymphomatosis presenting as fever of unknown origin. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:236–239. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiiba M, Izutsu K, Ishihara M. Early detection of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma by (18)FDG-PET/CT with diffuse FDG uptake in the lung without respiratory symptoms or chest CT abnormalities. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol. 2014;2:65–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu L, Chen Y. The role of 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT in the detection of fever of unknown origin. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:3524–3529. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colavolpe C, Ebbo M, Trousse D, Khibri H, Franques J, Chetaille B, Coso D, Ouvrier MJ, Gastaud L, Guedj E, Schleinitz N. FDG-PET/CT is a pivotal imaging modality to diagnose rare intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: case report and review of literature. Hematol Oncol. 2015;33:99–109. doi: 10.1002/hon.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]