See Schöll and Maass (doi:10.1093/brain/awz399) for a scientific commentary on this article.

Betthauser et al. present the results of a retrospective analysis of cognitive trajectories in initially unimpaired adults stratified according to PET amyloid and tau status. Individuals with elevated levels of both pathophysiological beta-amyloid and tau show faster cognitive decline during late middle-age than those with one or no elevated biomarkers.

Differences in cognitive performance over time were investigated between neuroimaging biomarker groups for beta-amyloid and tau in initially cognitively unimpaired persons. The combination of pathologic beta-amyloid and tau was detrimental to cognitive decline in preclinical AD during late middle-age. Middle-age health factors likely do not influence AD-related preclinical cognitive decline.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, tau imaging, amyloid imaging, dementia: biomarkers, neurofibrillary tangles

Abstract

This study investigated differences in retrospective cognitive trajectories between amyloid and tau PET biomarker stratified groups in initially cognitively unimpaired participants sampled from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. One hundred and sixty-seven initially unimpaired individuals (baseline age 59 ± 6 years; 115 females) were stratified by elevated amyloid-β and tau status based on 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and 18F-MK-6240 PET imaging. Mixed effects models were used to determine if longitudinal cognitive trajectories based on a composite of cognitive tests including memory and executive function differed between biomarker groups. Secondary analyses investigated group differences for a variety of cross-sectional health and cognitive tests, and associations between 18F-MK-6240, 11C-PiB, and age. A significant group × age interaction was observed with post hoc comparisons indicating that the group with both elevated amyloid and tau pathophysiology were declining approximately three times faster in retrospective cognition compared to those with just one or no elevated biomarkers. This result was robust against various thresholds and medial temporal lobe regions defining elevated tau. Participants were relatively healthy and mostly did not differ between biomarker groups in health factors at the beginning or end of study, or most cognitive measures at study entry. Analyses investigating association between age, MK-6240 and PiB indicated weak associations between age and 18F-MK-6240 in tangle-associated regions, which were negligible after adjusting for 11C-PiB. Strong associations, particularly in entorhinal cortex, hippocampus and amygdala, were observed between 18F-MK-6240 and global 11C-PiB in regions associated with Braak neurofibrillary tangle stages I–VI. These results suggest that the combination of pathological amyloid and tau is detrimental to cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease during late middle-age. Within the Alzheimer’s disease continuum, middle-age health factors likely do not greatly influence preclinical cognitive decline. Future studies in a larger preclinical sample are needed to determine if and to what extent individual contributions of amyloid and tau affect cognitive decline. 18F-MK-6240 shows promise as a sensitive biomarker for detecting neurofibrillary tangles in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Introduction

Definitive adjudication of Alzheimer’s disease is reserved for post-mortem neuropathology based on the presence of neurofibrillary tangles composed of aggregated microtubule associated tau protein, and amyloid-β plaques (Montine et al., 2012). Pathology studies indicate these pathological features follow distinct ordered patterns wherein the spatial extent and maturity/structure of the proteins vary regionally and chronologically (Thal et al., 2002; Braak et al., 2006). In vivo Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers for pathological tau and amyloid-β are important for understanding disease mechanisms, disease chronology, and enabling accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease during life. Much of the current research is directed towards detecting and defining Alzheimer’s disease during the preclinical period of disease (i.e. ‘preclinical Alzheimer’s disease’) wherein overt clinical symptoms are not yet manifest, but pathophysiological changes are occurring (McKhann et al., 2011; Sperling et al., 2011; Dubois et al., 2016). The focus on preclinical Alzheimer’s disease is due in part to the repeated observation in biomarker and neuropathology studies that the preclinical period exists and can be protracted, potentially lasting two decades, and is warranted because of the failure of clinical treatment trials to show efficacy in modifying cognitive outcomes in dementia patients (van Dyck, 2018).

Neuroimaging biomarkers allow spatiotemporal characterization of pathological amyloid-β and tau during life. The importance of biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease research and characterization of the Alzheimer’s disease continuum is reflected in the previous (Sperling et al., 2011) and current research frameworks published by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) (Jack et al., 2018). Recent prospective and retrospective neuroimaging studies have demonstrated an interactive effect of amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles on longitudinal cognitive decline in cognitively unimpaired persons (Aschenbrenner et al., 2018; Knopman et al., 2019; Sperling et al., 2019), whereas other cross-sectional and longitudinal studies did not observe this interaction, and suggested main effects of tangles and plaques on cognition (Scholl et al., 2016; Lowe et al., 2019). These important studies were largely conducted in older adults that are likely to have comorbid contributions to cognitive decline due to their age (Vassilaki et al., 2015), and could have a survivor bias due to the age cognitively unimpaired inclusion criteria were applied (Tschanz et al., 2011; Weuve et al., 2015). There is a need to investigate the associations between amyloid-β, neurofibrillary tangles and cognition in younger individuals. In addition, these studies used flortaucipir (i.e. T807, AV-1451) for tau PET imaging, which is known to exhibit age-associated off-target binding in the brain (Gordon et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2018) with mechanisms and the spatial extent of non-tau flortaucipir binding yet to be fully characterized in vivo (Vermeiren et al., 2018). 18F-MK-6240 (Hostetler et al., 2016) is a PET ligand for imaging neurofibrillary tangles in vivo that has shown favourable imaging characteristics and spatial distributions consistent with neuropathological staging of Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary tangles in preliminary studies (Betthauser et al., 2018; Lohith et al., 2018; Pascoal et al., 2018). Studies evaluating MK-6240 in humans indicated high affinity to neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease, minimal off-target binding in the brain, and the presence of extra-axial signal in some cases. Clinical studies using MK-6240, particularly in preclinical and prodromal disease, are needed to assess the utility of this tracer for detecting neurofibrillary tangles, associations with other Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers and cognition, and to reproduce flortaucipir findings in similarly designed studies.

The primary goal of this study was to investigate potential differences in retrospective cognitive trajectories of 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and 18F-MK-6240 PET stratified biomarker groups in a late middle-aged cohort of initially cognitively unimpaired subjects [The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention; WRAP (Johnson et al., 2018)]. Secondarily, analyses were conducted to ascertain the relationships between age, MK-6240 and PiB in this mostly healthy preclinical sample.

Materials and methods

Participants

Study participants for this analysis were from the WRAP (Johnson et al., 2018), an ongoing longitudinal observational study designed to identify the earliest changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease consisting of 1561 (∼1100 currently active) initially non-demented, middle-aged (mean enrolment age 54 years) individuals enriched with parental history of Alzheimer’s disease (73% enrichment). WRAP participants undergo comprehensive medical, neuropsychological and lifestyle evaluations and questionnaires biennially, which have been previously described (Johnson et al., 2018). A subset of 167 WRAP participants were included in this study if they underwent one or more cognitive assessments, were clinically unimpaired (i.e. did not have mild cognitive impairment or dementia diagnoses; see below) at their first available cognitive composite assessment, and completed MK-6240, PiB and T1-weighted MRI scans. MRI data were reviewed by a neuroradiologist (H.A.R.) prior to PET imaging and individuals with evidence of major structural lesions or other incidental findings that could affect PET imaging were excluded. Prior to PET enrolment all participants were screened for major neurological or psychological disorders. As MK-6240 only recently became available, this imaging visit was the temporal anchoring point for analyses (i.e. PiB and MRI imaging data closest to the MK-6240 scan were selected for analysis; PiB 0.23 ± 0.35 years before MK-6240; MRI 0.23 ± 0.46 years before MK-6240; all PiB and MRI scans within 2 years of MK-6240 scan). Only retrospective cognitive assessments relative to MK-6240 imaging were included in this analysis (i.e. no cognitive data post-MK-6240 were included).

Participants’ written consent was obtained prior to study procedures according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved and conducted under the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board, and the Federal Drug Administration Investigational New Drug mechanism for PET imaging studies. No serious study related adverse events were reported for administration of PiB or MK-6240.

Neuropsychological assessment

As part of WRAP, participants complete a neuropsychological battery at their first visit, 2 or 4 years later for their second visit, and approximately every 2 years thereafter (Johnson et al., 2018). The primary cognitive outcome for analyses was a cognitive composite based on work by Donohue and colleagues (Donohue et al., 2014; Mormino et al., 2017; Jonaitis et al., 2019). This composite (three-test preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite: PACC-3) (Jonaitis et al., 2019) is computed by standardizing and then averaging three summary scores that include tests of memory and executive function: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (Schmidt, 1996), sum of learning trials; Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, Logical Memory II Delayed Recall (Wechsler, 1987); and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised, Digit Symbol (Wechsler, 1981).

Cognitive status determination

Participants received a research diagnosis after each visit as described previously (Johnson et al., 2018). Briefly, research diagnoses were made by a team of clinicians (physician dementia specialists, nurse practitioners, and neuropsychologists) blind to biomarker data (e.g. PET or CSF data). Those who met criteria for impairment reflecting a change from a prior normal level of function were assigned a research diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment when applicable (no participants in this analysis received a dementia diagnosis at the time of PET or prior) (Albert et al., 2011; McKhann et al., 2011). All other participants were cognitively unimpaired.

Structural and molecular neuroimaging

All participants underwent PET (Siemens EXACT HR+) and MRI (3 T GE Signa 750) imaging procedures at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Waisman Center Brain Imaging Lab. PET radiopharmaceuticals were synthesized and administered under the Federal Drug Administration Investigational New Drug mechanism. Detailed imaging methods including radiopharmaceutical production, acquisition protocols, and image reconstruction, processing and quantification of PiB and MK-6240 PET data (SPM12 and MATLAB) have been previously described (Johnson et al., 2014; Betthauser et al., 2018).

T1-weighted MRIs were bias corrected, tissue class segmented and spatially normalized to MNI152 standard space (SPM12; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Hippocampal volume was estimated using FSL FIRST and normalized by total intracranial volume (sum of grey matter, white matter, and CSF volumes from SPM segmentation). A measure of global atrophy was calculated as the ratio of CSF volume to the sum of the grey matter and white matter tissue volumes. Regions of interest for the PET analysis were generated by inverse warping MNI152 template regions of interest [Harvard-Oxford (Desikan et al., 2006) and Automated Anatomical Labeling (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002)] to subject space and restricting to grey matter probabilities >0.3. PET reference region masks were generated by smoothing bilateral binary regions of interest with a 6 mm Gaussian kernel (to simulate PET spatial resolution) and keeping voxels >0.7.

The PiB scan most proximal to the MK-6240 scan was used for this analysis. PiB distribution volume ratio (DVR) was estimated from a 70-min dynamic acquisition using reference Logan graphical analysis (t* = 35 min, k2 = 0.149 min−1, cerebellum grey matter reference region). A global cortical DVR average was calculated (Sprecher et al., 2015) for continuous analyses and used to dichotomize individuals as amyloid positive or negative (A+/−) using a previously defined global DVR threshold of >1.19 (Racine et al., 2016).

18F-MK-6240 standard uptake value ratios (SUVRs) were calculated from a 20-min dynamic acquisition (4 × 5-min frames) beginning 70 min after bolus injection using the inferior cerebellum grey matter as previously described (Betthauser et al., 2018). Elevated tau status (T+/−) for the primary analysis was established by setting the MK-6240 SUVR positivity threshold at 2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean of the A− group in the entorhinal cortex (entorhinal MK-6240 SUVR > 1.27). The entorhinal cortex was chosen for the primary analysis due to it being the first region involved in pathological staging of neurofibrillary tangles (Braak and Braak, 1991) and to investigate the potential for MK-6240 in this region to detect early tangle pathophysiology in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Partial volume correction was not performed because of a lack of observed atrophy and a lack of association between region of interest volume and MK-6240 SUVR in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus (Supplementary material, section 1).

Statistical methods

Four biomarker groups were established (A−T−, A−T+, A+T−, and A+T+) based on combinations of PET-based biomarker positivity. Dichotomous measures were used instead of continuous measures to test these relationships in the context of the NIA-AA research framework and because of power limitations related to model selection (continuous model would require a 3-way interaction), potential non-linear relationships between continuous measures of tau, amyloid and cognitive decline, and to reduce the influence of extreme points in the data. Participants’ cognitive trajectories were modelled using linear mixed-effects models including subject-specific random intercepts and age-related slopes that were allowed to correlate. The predictors of interest were biomarker group and its interaction with age (i.e. time) to investigate whether retrospective, longitudinal cognitive trajectories differed between biomarker groups. Covariates included sex, Wide Range Achievement Test-III Reading standard score (Wilkinson, 1993) (a proxy for educational quality) and the number of prior exposures to the battery. Following a significant interaction, pairwise differences in simple PACC-3 age slopes between the four groups were assessed using Tukey-adjusted post hoc tests. Sensitivity analyses of the main model were performed to investigate the influence of the T+/− threshold (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 SD above the mean MK-6240 SUVR in A− cases) and using the hippocampus for defining elevated tau (Supplementary material). Differences between biomarker group demographics and exploratory follow-up analyses comparing cognitive and health characteristics were assessed using tests appropriate for the distribution of each variable and included ANOVA, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), Kruskal-Wallis, χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. All significance tests were two-tailed. Unadjusted post hoc pairwise comparisons were reported if the group test was significant (P < 0.05). Analyses were conducted in MATLAB v2016a and 2018a (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) and R v3.5.3 (Lenth, 2019; Pinheiro et al., 2019; R Development Core Team, 2019).

Voxelwise associations between MK-6240 SUVR, global PiB DVR, and age were investigated using SPM12. Parametric MK-6240 SUVR images coregistered to T1 MRI were non-linearly transformed to MNI152 space using the transformation defined from T1 MRI segmentation and isotropically smoothed using an 8 mm Gaussian kernel. Voxelwise outcomes were corrected for familywise error using random field theory at an adjusted alpha of 0.05. For region of interest analyses, volume-weighted mean SUVR was calculated for composite regions representing Braak I–VI neurofibrillary tangle stages (Braak I: entorhinal cortex; Braak II: hippocampus; Braak III: temporal portion of fusiform gyrus; Braak IV: inferior and middle temporal gyri and insular cortex; Braak V: superior temporal, angular, supramarginal, and middle frontal gyri, planum temporale and the occipital portion of the fusiform gyrus; Braak VI: Heschl’s gyrus and intracalcarine cortex) (Braak et al., 2006) and additional exploratory neurofibrillary tangle targets (amygdala, posterior cingulate, precuneus, and lingual gyrus) and previously reported off-target binding regions for flortaucipir (Gordon et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2018) (caudate and putamen). The regions used to generate Braak composite regions were selected by matching Harvard-Oxford atlas regions of interest to slices and regions described in the work of Braak et al. (2006). Region of interest-level analyses investigated associations between MK-6240 SUVR, global PiB DVR and age by reporting the proportion of MK-6240 SUVR variance explained by both age and global PiB DVR (Pearson coefficient of determination, ) and the partial Pearson correlations between MK-6240 SUVR and age ( Age) partialling out PiB and between MK-6240 SUVR and global PiB DVR (

Age) partialling out PiB and between MK-6240 SUVR and global PiB DVR ( PiB) partialling out age. These outcomes are analogous to linear regression models with global PiB DVR and age predicting MK-6240 SUVR. Unadjusted Pearson correlations between MK-6240 and age (rAge) are also reported for comparisons to other tau imaging studies. To investigate potential MK-6240 SUVR-age association in amyloid negative cases (i.e. primary age-related tauopathy) further, Pearson correlations between age and MK-6240 SUVR were investigated using only amyloid-negative cases (n = 129, age range 50–80 years, mean ± SD = 66.7 ± 6.4 years).

PiB) partialling out age. These outcomes are analogous to linear regression models with global PiB DVR and age predicting MK-6240 SUVR. Unadjusted Pearson correlations between MK-6240 and age (rAge) are also reported for comparisons to other tau imaging studies. To investigate potential MK-6240 SUVR-age association in amyloid negative cases (i.e. primary age-related tauopathy) further, Pearson correlations between age and MK-6240 SUVR were investigated using only amyloid-negative cases (n = 129, age range 50–80 years, mean ± SD = 66.7 ± 6.4 years).

Data availability

Data from the WRAP and ADRC cohorts can be requested through an online submission process.

Results

Demographic features

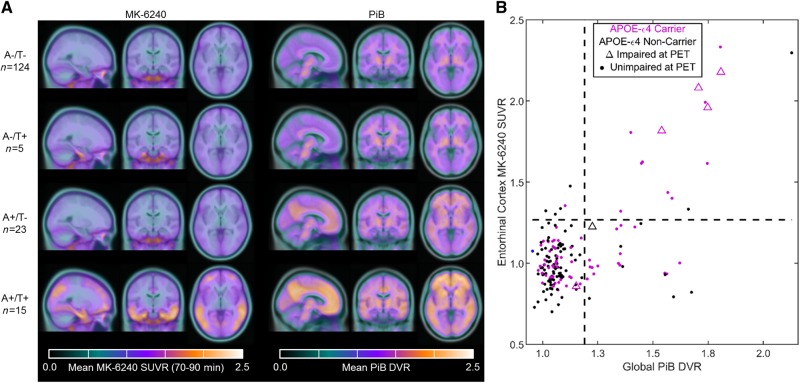

Demographic features of the study sample, including age, duration of retrospective follow-up and time between cognitive assessments and imaging procedures are provided in Table 1 with the MK-6240, PiB and MRI-based atrophy measures shown in Table 2. Group mean parametric images and quadrant analysis of entorhinal MK-6240 SUVR and global PiB DVR showing positivity thresholds are displayed in Fig. 1. At the time of PET scans, 74% (n = 124) were classified as A−T−, 3% (n = 5) as A−T+, 14% (n = 23) as A+T−, and 9% (n = 15) as A+T+. Participants were 67.5 ± 6.2 (mean ± SD) years old at the time of their MK-6240 scan, with PiB and MRI scans generally within 2 months (mean ± SD = 1.5 ± 4.2 months for PiB, P = 0.52; 2.8 ± 0.2 months for MRI, P = 0.97) of the MK-6240 scan. The average age at the cognitive assessment most proximal to PET imaging was 66.7 ± 6.3 years, with significant group differences (P = 0.02) observed between the A−T− and A+T− groups. Retrospective cognitive assessments spanned 7.8 ± 2.1 years (median of five assessments) with the most recent cognitive assessment occurring ∼8 months prior to the MK-6240 scan. Significant group differences were not observed for sex, race, parental history of dementia or Wide Range Achievement Test-III Reading standard score. Significant group differences (P < 0.001) were observed for APOE ε4. Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated the frequency of both the presence of APOE ε4 and homozygous carriers differed by group, such that each was highest for the A+T+ group, followed by the A+T− group and then A−T− and A−T+ groups. Eight participants received a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment during the study. Of these, two reverted to cognitively unimpaired after mild cognitive impairment status at a single time point (both A−T− and reverting after their second cognitive assessment), one (A+T−) was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment consistently over the last four cognitive assessments spanning 7.7 years, and the remaining subjects (one A−T−, four A+T+) were considered to have mild cognitive impairment only at their most recent cognitive assessment, which was the assessment most proximal to PET imaging.

Table 1.

Demographics of study sample

| Participant demographics | 1. A−T− (n = 124; 74%) a | 2. A−T+ (n = 5; 3%) | 3. A+T− (n = 23; 14%) a | 4. A+T+ (n = 15; 9%) | Group test P-value | Pairwise differences | Total (n = 167) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages and timing of cognitive assessments | |||||||

| Age at most recent cognitive assessment, year | 65.7 ± 6.4 | 72.0 ± 6.0 | 69.3 ± 4.9 | 69.9 ± 4.5 | 0.001 | 1 versus 3 | 66.7 ± 6.3 |

| Age at first cognitive assessment with PACC-3, yearsa | 58.2 ± 6.2 | 63.2 ± 6.7 | 60.7 ± 4.7 | 62.0 ± 4.4 | 0.02 | - | 59.0 ± 6.0 |

| Years of retrospective assessments, yearsa | 7.6 ± 2.1 | 8.8 ± 2.9 | 8.7 ± 1.7 | 7.9 ± 2.3 | 0.10 | - | 7.8 ± 2.1 |

| Number of retrospective assessmentsa, median [IQR] | 5 [5, 6] | 6 [5.75, 6] | 6 [5, 6] | 5 [5, 6] | 0.04 | - | 5 [5, 6] |

| Time between most recent cognitive assessment and imaging procedures | |||||||

| Years PiB, recent cognitive | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.82 | - | 0.7 ± 0.9 |

| Years MK-6240, recent cognitive | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.96 | - | 0.8 ± 0.9 |

| Years MRI, recent cognitive | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.95 | - | 0.6 ± 0.9 |

| Participant demographics | |||||||

| Female, % (n) | 67.7 (84) | 100 (5) | 60.9 (14) | 80.0 (12) | 0.27 | - | 68.9 (115) |

| Non-Caucasian, % (n) | 8.1 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.57 | - | 6.8 (11) |

| Family history of dementia, % (n) | 70.2 (87) | 100.0 (5) | 69.6 (16) | 93.3 (14) | 0.13 | - | 73.1 (122) |

| WRAT-III reading score, median [IQR] | 109 [103, 115] | 104 [99, 115] | 111 [106, 115] | 109 [105, 113] | 0.73 | - | 110 [103, 114] |

| APOE ε4 carriers, % (n) | 33.3 (41) | 20.0 (1) | 65.2 (15) | 86.7 (13) | <0.001 | 3 versus 1; 4 versus 1,2 | 42.5 (70) |

| Number of APOE-ε4 alleles, % (n) | |||||||

| Non-carriers | 66.7 (82) | 80.0 (4) | 36.4 (8) | 13.3 (2) | <0.001 | 3 versus 1; 4 versus 1,2 | 58.2 (96) |

| Heterozygous | 31.7 (39) | 20.0 (1) | 54.5 (12) | 66.7 (10) | 3 versus 1; 4 versus 1,2 | 37.6 (62) | |

| Homozygous | 1.6 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (2) | 20.0 (3) | 3 versus 1; 4 versus 1,2 | 4.2 (7) | |

Unless noted otherwise reported values represent the mean and standard deviation with group difference tested by analysis of variance. For group tests with P < 0.05, unadjusted pairwise post hoc differences are reported. Ordinal variables reported as median [IQR] were tested by Kruskal-Wallis for group differences. Categorical variables reported as % (n) of each category within each group and were tested by χ2 for group differences. A+/− and T+/− represent amyloid-β and tau tangle positivity groups ascertained by 11C-PiB and 18F-MK-6240 PET, respectively. ‘Most recent cognitive’ assessment refers to the cognitive assessment temporally proximal to imaging procedures.

IQR = interquartile range; WRAT-III = Wide Range Achievement Test – third edition.

Two participants (one A−T−, one A+T−) had only one cognitive assessment that was temporally proximal to imaging and therefore were not included in cross-sectional group statistics for variables with retrospective visits.

Table 2.

Summary and group comparisons of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers

| Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers | 1. A−T− (n = 124) | 2. A−T+ (n = 5) | 3. A+T− (n = 23) | 4. A+T+ (n = 15) | Group test P-value | Pairwise differences | Total (n = 167) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal volume, % ICV | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.03 | 1 versus 4 | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

| Global atrophy (CSF / brain volume) | 0.34 ± 0.08 | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.08 | - | 0.35 ± 0.08 |

| PiB global DVR | 1.05 ± 0.5 | 1.08 ± 0.04 | 1.38 ± 0.15 | 1.65 ± 0.20 | ≪0.001 | 3 versus 1,2 4 versus 1,2,3 | 1.15 ± 0.21 |

| MK-6240 SUVR (70–90 min) | |||||||

| Braak I | 0.98 ± 0.12 | 1.36 ± 0.07 | 1.01 ± 0.14 | 1.79 ± 0.34 | ≪0.001 | 2 versus 1,3,4; 4 versus 1,2,3 | 1.07 ± 0.28 |

| Braak II | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 1.02 ± 0.6 | 0.87 ± 0.11 | 1.43 ± 0.25 | ≪0.001 | 4 versus 1,2,3 | 0.92 ± 0.21 |

| Braak III | 1.09 ± 0.11 | 1.24 ± 0.11 | 1.12 ± 0.15 | 1.73 ± 0.58 | ≪0.001 | 4 versus 1,2,3 | 1.16 ± 0.27 |

| Braak IV | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | 1.06 ± 0.13 | 1.72 ± 0.71 | ≪0.001 | 4 versus 1,2,3 | 1.10 ± 0.30 |

| Braak V | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 1.03 ± 0.10 | 1.05 ± 0.10 | 1.58 ± 0.56 | ≪0.001 | 4 versus 1,2,3 | 1.09 ± 0.25 |

| Braak VI | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 1.01 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.22 | ≪0.001 | 4 versus 1,2,3 | 1.00 ± 0.13 |

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation with ANOVA tests for group comparisons. For group tests with P < 0.05, unadjusted pairwise post hoc differences are reported. Braak I through VI labels represent composite regions corresponding to Braak neurofibrillary tangle stages.

ICV = intracranial volume.

Figure 1.

Parametric MK-6240 and PiB images, and biomarker group stratification. Mean parametric MK-6240 SUVR (A, left) and PiB DVR (A, right) images for each biomarker group. Individuals that were A−T+ only had elevated MK-6240 SUVR in the entorhinal cortex, whereas the A+T+ group had elevated MK-6240 SUVR extending into the greater neocortex including regions associated with Braak neurofibrillary tangle stages I–IV. Individuals that were A+T− had lower PiB DVR throughout the cortex and subcortex compared to the A+T+ group. Quadrant plots indicating the observed relationship between global PiB DVR and MK-6240 SUVR in the entorhinal cortex are shown in B with positivity thresholds for each tracer indicated with dashed lines. Individuals generally required sufficient levels of global PiB to show elevated MK-6240 in the entorhinal cortex, suggesting detectable changes in PiB precede detectable changes in entorhinal MK-6240 in most cases. Individuals with mild cognitive impairment at PET (triangles) were more likely to be in the A+T+ group than any other group.

At the time of MK-6240, hippocampal volume adjusted for intracerebral volume (P = 0.03), but not global atrophy (P = 0.08), differed between the groups with post hoc comparisons indicating the A+T+ group had smaller hippocampi than the A−T− group (Table 2). By design, PET binding measures were significantly different between groups (P < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons of global PiB DVR indicated the A+T+ group differed from all other groups (A+T+ > than other groups) and the A+T− group differed from the A− groups (A+T− > A− groups). For entorhinal cortex (i.e. Braak I), MK-6240 SUVR differed between the A+T+ and all other groups (A+T+ > other groups), and between the A−T+ group and the T− groups (A−T+ > T− groups). For Braak II–VI neurofibrillary tangle composite regions, MK-6240 SUVR was significantly different between the A+T+ group and all other groups (A+T+ > other groups).

Biomarkers and longitudinal retrospective cognition

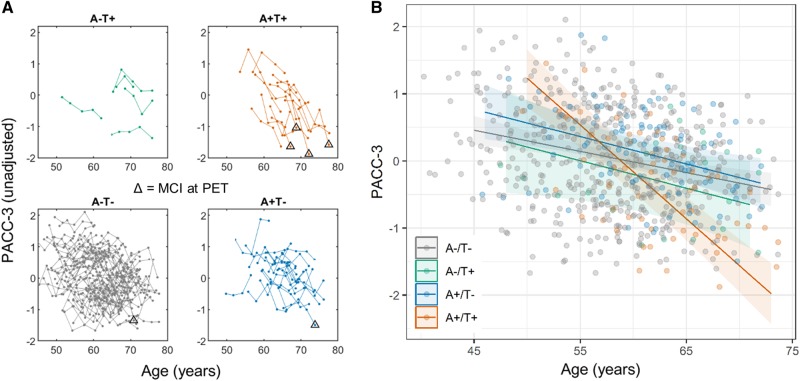

Potential differences in retrospective cognitive trajectories between PiB and MK-6240 stratified biomarker groups were investigated by plotting longitudinal PACC-3 performance versus age stratified by biomarker groups (Fig. 2A) and by linear mixed effects regression (Table 3). The mixed effects model indicated a significant group × age effect (i.e. PACC-3 trajectories differed over time between biomarker groups; Table 3). Tukey adjusted pairwise comparisons indicated that the A+T+ group had significantly different retrospective PACC-3 trajectories compared to all other groups, but that the other groups did not differ from one another. Comparison of the simple age-related PACC-3 slopes suggested the A+T+ group declined approximately three times faster than all other groups during the retrospective observation period, which is depicted in the plots of the simple PACC-3 age slopes for each biomarker group (Fig. 2B). Model diagnostics of the primary model suggested no significant departures of the residuals from normality. Plots of individual participants’ longitudinal PACC-3 performance (i.e. spaghetti plots) organized by biomarker group indicated that this group-level pattern of decline in the A+T+ group was visually apparent within individuals and existed several years prior to PET imaging and mild cognitive impairment diagnosis. These main findings were consistent using lower entorhinal cortex thresholds and using the hippocampus with various thresholds to define elevated tau status (Supplementary material, sections 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Observed and group-modelled cognitive performance by biomarker group. Observed longitudinal PACC-3 performance organized by biomarker groups (A). Triangles indicate individuals with mild cognitive impairment at their cognitive assessment most proximal to PET imaging. Individuals who had elevated global PiB DVR and entorhinal MK-6240 SUVR (top right) had more precipitous decline in scores over time several years prior to mild cognitive impairment diagnosis and prior to imaging. The difference in rates of cognitive decline between biomarker groups was characterized using linear mixed effects analysis (model outcomes given in Table 3). Panel B shows the group-level modelled PACC-3 simple slopes and confidence levels over the range of ages present in each group, with the individual observed PACC-3 performance displayed in the background (points). Results of the linear mixed effects model indicated a significant group × age interaction. Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons indicated that the A+T+ group (orange in plots) declined approximately three times faster on average during the retrospective observation period compared to all other groups.

Table 3.

Model statistics for primary analysis

| Primary model statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PACC-3 ˜ Covariates + Group + Age + Group × Age + random slope + random intercept | |||

| Variable | β | 95% CI | P |

| Covariates | |||

| Intercept | −3.44 | −4.60, −2.29 | 0.42 |

| Female | 0.45 | 0.25, 0.64 | <0.0001 |

| WRAT III | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| Practice | 0.07 | 0.03, 0.10 | 0.0020 |

| Predictors of interest | |||

| Age | −0.03 | −0.05, −0.02 | <0.0001 |

| Group | 0.24 | ||

| Group 2 | −0.14 | −0.74, 0.46 | |

| Group 3 | 0.22 | −0.06, 0.50 | |

| Group 4 | 0.39 | 0.04, 0.74 | |

| Age × Group | <0.0001 | ||

| Age × Group 2 | −0.01 | −0.05, 0.03 | |

| Age × Group 3 | −0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 | |

| Age × Group 4 | −0.11 | −0.13, −0.08 | |

| Age × Group details Simple PACC-3 slopes | |||

| Group | β (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Group 1: A−T− | −0.032 (0.008) | −0.047, −0.017 | |

| Group 2: A−T+ | −0.041 (0.021) | −0.082, −0.0001 | |

| Group 3: A+T− | −0.041 (0.012) | −0.064, −0.017 | |

| Group 4: A+T+ | −0.140 (0.015) | −0.168, −0.111 | |

| Group contrasts between PACC-3 slopes | |||

| Contrast | β (SE) | P a | |

| A−T− minus A−T+ | 0.009 (0.020) | 0.97 | |

| A−T− minus A+T− | 0.009 (0.011) | 0.83 | |

| A−T− minus A+T+ | 0.108 (0.014) | <0.0001 | |

| A−T+ minus A+T− | −0.0001 (0.022) | 1.00 | |

| A−T+ minus A+T+ | 0.099 (0.024) | 0.0002 | |

| A+T− minus A+T+ | 0.099 (0.016) | <0.0001 | |

Model statistics for primary analysis linear mixed effects model investigating the association between biomarker groups and retrospective cognition (i.e. PACC-3). Parameter estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values are shown for the main model covariates, age, group and the interaction of group × age (top half of table) with the A−T− group (i.e. group 1) as the contrast group. The significant group × age effect indicates group level differences in longitudinal retrospective PACC-3 trajectories. A breakdown of the details of the group × age interaction shows the estimate, standard error (SE) and 95% CI of the simple PACC-3 slopes for each biomarker group, and the Tukey adjusted post hoc comparisons of biomarker group slopes (bottom half of table).

WRAT-III = Wide Range Achievement Test – third edition.

Tukey-adjusted significance for family of four.

Post hoc analyses examining the individual untransformed scores that comprise the PACC-3 (i.e. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, sum of learning trials; Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, Logical Memory II Delayed Recall; and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised, Digit Symbol) gave similar results to the primary analysis with generally smaller P-values compared to the PACC-3 model (data not shown).

Biomarkers and cross-sectional cognition and health

At the beginning of the retrospective study period (i.e. study entry), there were no group differences in PACC-3, individual tests that comprise the PACC-3, the Mini-Mental Status Examination, the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (Jorm, 1994), self-reported memory problems or self-reported memory rating (Table 4, top). The median Center on Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score (Radloff, 1977) was 5 at the beginning and 4 at the end of study (i.e. the study sample was not depressed on average) with group differences observed at study entry, but not at the assessment most proximal to imaging. At the end of the retrospective period, group differences were observed for PACC-3 and two of its components (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, sum of learning trials; Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, Logical Memory II Delayed Recall), Mini-Mental Status Examination, self-reported memory rating, and the frequency of mild cognitive impairment diagnosis, but not for Digit Symbol from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised, the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly, the Center on Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, or self-reported memory problems (Table 4, bottom).

Table 4.

Group comparisons of cognitive outcomes at the beginning and end of the study period

| Cognitive assessment | 1. A−T− (n = 124)a | 2. A−T+ (n = 5) | 3. A+T− (n = 23)a | 4. A+T+ (n = 15) | Group test P-value | Pairwise differences | Total (n = 167) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive assessment at study entry | |||||||

| Age at First PACC-3, years | 58 ± 6 | 63 ± 7 | 61 ± 5 | 62 ± 4 | 0.02 | - | 59 ± 6 |

| CES-D, median [IQR] | 5 [2, 8.75] | 4 [2.25, 7.75] | 2 [0, 4] | 5 [2, 6.75] | 0.02 | - | 4 [2, 8] |

| PACC-3 (95% CI) | 0.07 (−0.04, 0.17) | −0.09 (−0.61, 0.43) | 0.31 (0.06, 0.56) | 0.08 (−0.22, 0.38) | 0.30 | - | - |

| PACC-3 Components (Covariates: sex, WRAT-III and age) | |||||||

| RAVLT Total (95% CI) | 50.5 (49.2, 51.8) | 49.0 (42.5, 55.4) | 51.7 (48.7, 54.8) | 49.7 (46.0, 53.4) | 0.80 | - | - |

| WMS-R LM DR (95% CI) | 26.5 (25.4, 27.6) | 25.1 (19.5, 30.7) | 28.3 (25.7, 31.0) | 27.2 (24.0, 30.4) | 0.59 | - | - |

| WAIS-R Digit Symbol (95% CI) | 57.7 (56.1, 59.2) | 56.7 (49.1, 64.3) | 61.3 (57.7, 64.9) | 58.1 (53.7, 62.5) | 0.34 | - | - |

| MMSE, median [IQR] | 30 [29, 30] | 29 [28, 30] | 30 [29, 30] | 29 [29, 30] | 0.38 | - | 30 [29,30] |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 0 |

| IQCODE, median [IQR] | 48 (10 na) [48, 48] | 48 [47.75, 50.25] | 48 (4 na) [48, 49] | 48 (1 na) [48, 48] | 0.84 | - | 48 [48, 48] |

| Self-reported memory problem % (n) | 0.29 | ||||||

| Yes | 25.2 (31) | 20.0 (1) | 18.2 (4) | 26.7 (4) | - | 24.2 (40) | |

| No | 50.4 (62) | 40.0 (2) | 77.3 (17) | 53.3 (8) | - | 53.9 (89) | |

| Don’t know | 24.4 (30) | 40.0 (2) | 4.5 (1) | 20.0 (3) | - | 21.8 (36) | |

| Memory Self Rating, median [IQR] | 5 [4, 6] | 4 [3, 5.5] | 5 [5, 6] | 5 [4, 5] | 0.38 | - | 5 [4, 6] |

| Most recent cognitive assessment (i.e. most proximal to PET) | |||||||

| Age at most recent cognitive assessment, years | 65.7 ± 6.4 | 72.0 ± 6.0 | 69.3 ± 4.9 | 69.9 ± 4.5 | 0.001 | 1 versus 3 | 66.7 ± 6.3 |

| CES-D median [IQR] | 4 (1 na) [1, 8] | 2 [0.75, 5.75] | 3 [1.25, 7] | 8 (2 na) [1, 12] | 0.44 | - | 4 (3 na) [1, 8] |

| PACC-3 (95% CI) | 0.02 (−0.10, 0.14) | −0.23 (−0.83, 0.37) | 0.16 (−0.11, 0.44) | −0.82 (−1.16, −0.47) | <0.001 | 4 versus 1,3 | - |

| PACC-3 Components (Covariate: sex, WRAT-III, age, practice) | |||||||

| RAVLT Total (95% CI) | 51.8 (50.4, 53.2) | 49.1 (42.1, 56.1) | 53.4 (50.1, 56.7) | 43.6 (39.6, 47.6) | 0.001 | 4 versus 1,3 | - |

| WMS-R LM DR (95% CI) | 27.0* (25.8, 28.2) | 24.0 (18.2, 29.8) | 27.9 (25.2, 30.6) | 20.4 (17.1, 23.7) | 0.002 | 4 versus 1,3 | - |

| WAIS-R Digit Symbol (95% CI) | 54.0 (52.3, 55.6) | 53.9 (45.5, 62.3) | 55.0 (51.1, 58.9) | 47.6 (42.8, 52.4) | 0.08 | - | - |

| MMSE, median [IQR] | 30 [29, 30] | 30 [29, 30] | 30 [29, 30] | 29 [27, 29.75] | 0.02 | 4 versus 1 | 30 [29, 30] |

| Mild cognitive impairment %(n) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (1) | 26.7 (4) | <0.001 | 4 versus 1,3 | 3.6 (6) |

| IQCODE, median [IQR] | 48 (4 na) [48, 49] | 48 [48, 48.5] | 48 (3 na) [48, 49.5] | 48 [48, 51] | 0.76 | - | 48 (7 na) [48,49] |

| Self-reported memory problem % (n) | 0.60 | ||||||

| Yes | 17.8 (22) | 40.0 (2) | 26.1 (6) | 26.7 (4) | - | 20.4 (34) | |

| No | 59.7 (74) | 60.0 (3) | 60.9 (14) | 46.7 (7) | - | 58.7 (98) | |

| Don’t know | 22.6 (28) | 0.0 (0) | 13.0 (3) | 26.7 (4) | - | 21.0 (35) | |

| Memory self rating, median [IQR] | 5 [4, 6] | 5 [3, 6.25] | 5 [5, 5.75] | 4 [3, 5.75] | 0.04 | 1 versus 4 | 5 [4, 6] |

Comparisons of cognitive assessment metrics between biomarker groups at the beginning of the retrospective study period (top half) and at the most recent assessment most proximal to imaging studies (bottom half). Unless noted otherwise reported values represent the mean ± SD with group differences tested by analysis of variance. For group tests with P < 0.05, unadjusted pairwise post hoc differences are reported. Ordinal variables are reported as median [IQR] with group differences tested by Kruskal-Wallis. Categorical variables are reported as % (n) of each category within each group and were tested for group differences by χ2. The PACC-3 and tests that comprise the PACC-3 were tested for group difference by analysis of covariance adjusted for age, sex, and Wide Range Achievement Test-III, (also number of exposures to PACC-3 battery for most recent assessment) and are reported as the adjusted mean (95% CI). A+/− and T+/− represent amyloid-β and tau tangles positivity groups ascertained by 11C-PiB and 18F-MK-6240 PET, respectively. CESD-D = Center on Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; IQCODE = Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; MMSE = Mini-Mental Status Examination; na = not available; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WAIS-R = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised; WMS-R LM DR= Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory II Delayed Recall.

Two participants (one A−T−, one A+T−) had only one cognitive assessment that was temporally proximal to imaging and therefore were not included in cross-sectional group statistics for the study entry time point.

On average, the study sample was overweight [i.e. 25 ≤ BMI < 30; body mass index (BMI) mean ± SD = 28.6 ± 5.8 at study entry, 28.9 ± 6.2 proximal to MK-6240 scan], in the middle to high normal range for cardiovascular health (total and non-HDL cholesterol) and insulin sensitivity (fasting glucose and insulin), and was not vitamin B12 deficient (Table 5). Weakly significant differences in health characteristics were observed for waist-to-hip ratio (adjusted for sex) at the end of the study period (P = 0.05; A+T− less than A−T−) and serum fasting insulin at the beginning of the study period (P = 0.02; A−T+ > both A−T− and A+T−). No other health characteristics (systolic blood pressure, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, total cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, fasting serum insulin, fasting glucose, highly sensitive c-reactive protein, and vitamin B12) differed significantly between the groups at either the beginning or end of the study period.

Table 5.

Health characteristics at the beginning and end of the study period

| Health assessment | 1. A−T− (n = 124) a | 2. A−T+ (n = 5) | 3. A+T− (n = 23) a | 4. A+T+ (n = 15) | Group test (P-Value) | Pairwise differences | Total (n=167) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health assessment at study entry | |||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 125 ± 15 | 131 ± 12 | 120 ± 13 | 130 ± 17 | 0.22 | - | 125 ± 15 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.7 ± 6.1 | 31.9 ± 3.9 | 27.3 ± 5.0 | 27.9 ± 4.3 | 0.40 | - | 28.6 ± 5.8 |

| Waist:hip ratio, sex covaried (95% CI) | 0.85 (0.84, 0.87) | 0.83 (0.76, 0.90) | 0.82 (0.79, 0.85) | 0.84 (0.80, 0.88) | 0.39 | - | - |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 200 ± 34 | 202 ± 41 | 199 ± 25 | 194 ± 31 | 0.91 | - | 200 ± 33 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 139 ± 33 | 147 ± 39 | 140 ± 22 | 134 ± 30 | 0.88 | - | 139 ± 32 |

| Insulin, mIU/l | 9.1 ± 6.8 | 17.8 ± 11.3 | 7.7 ± 4.3 (1 na) | 9.8 ± 3.8 | 0.02 | 2 versus 1,3 | 9.3 ± 6.6 (1 na) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl | 97.8 ± 16.9 | 98 ± 5 | 95 ± 8 | 96 ± 8 | 0.87 | - | 97.3 ± 15.0 |

| hs-CRP, mg/l | 2.6 ± 3.4 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 3.5 ± 8.8 (1 na) | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 0.37 | - | 2.6 ± 4.3 |

| Vitamin B12, ng/ml | 691 ± 276 (1 na) | 744 ± 124 | 767 ± 294 | 733 ± 275 (1 na) | 0.64 | - | 706 ± 274 (2 na) |

| Health assessment proximal to PET imaging | |||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 127 ± 15 (1 na) | 122 ± 13 | 127 ± 18 | 132 ± 18 | 0.58 | - | 127 ± 16 (1 na) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.3 ± 6.4 (2 na) | 31.4 ± 5.4 | 27.4 ± 5.9 | 27.2 ± 4.3 | 0.29 | - | 28.9 ± 6.2 (2 na) |

| Waist:hip ratio, sex covaried (95% CI) | 0.87 (0.86, 0.89) | 0.88 (0.82, 0.94) | 0.83 (0.80, 0.86) | 0.86 (0.83, 0.90) | 0.05 | 3 versus 1 | - |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 203 ± 40 (5 na) | 166 ± 30 | 200 ± 40 (1 na) | 192 ± 41 | 0.17 | - | 201 ± 40 (6 na) |

| Non-HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 141 ± 38 (5 na) | 116 ± 21 | 141 ± 36 (1 na) | 129 ± 32 | 0.32 | - | 139 ± 37 (6 na) |

| Insulin, mIU/l | 9.7 ± 7.3 (6 na) | 12.8 ± 6.8 | 8.0 ± 4.2 (1 na) | 8.9 ± 3.1 | 0.47 | - | 9.5 ± 6.6 (7 na) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl | 99.1 ± 14.2 (5 na) | 99.2 ± 17.7 | 94.8 ± 10.9 (1 na) | 95.7 ± 9.3 | 0.49 | - | 98.2 ± 13.5 (6 na) |

| hs-CRP, mg/l | 4.0 ± 14.8 (5 na) | 4.3 ± 5.3 | 4.1 ± 8.5 (1 na) | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.85 | - | 3.7 ± 13.1 (6 na) |

| Vitamin B12, ng/ml | 599 ± 363 (7 na) | 826 ± 562 (1 na) | 577 ± 236 (1 na) | 603 ± 261 | 0.61 | - | 602 ± 344 (9 na) |

Health features at study entry (top) and at the assessment most proximal to PET imaging (bottom). Unless noted otherwise, results are reported as mean ± SD with group differences tested by analysis of variance. For group tests with P < 0.05, unadjusted pairwise post hoc differences are reported. Waist:hip ratio was tested for group differences by analysis of covariance adjusted for sex with results reported as sex-adjusted mean (95% CI).

HDL = high-density lipoproteins; hs-CRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; na = not available.

Two participants (one A−T−, one A+T−) only had one health assessment that was temporally proximal to imaging and therefore were not included in cross-sectional group statistics for the study entry time point.

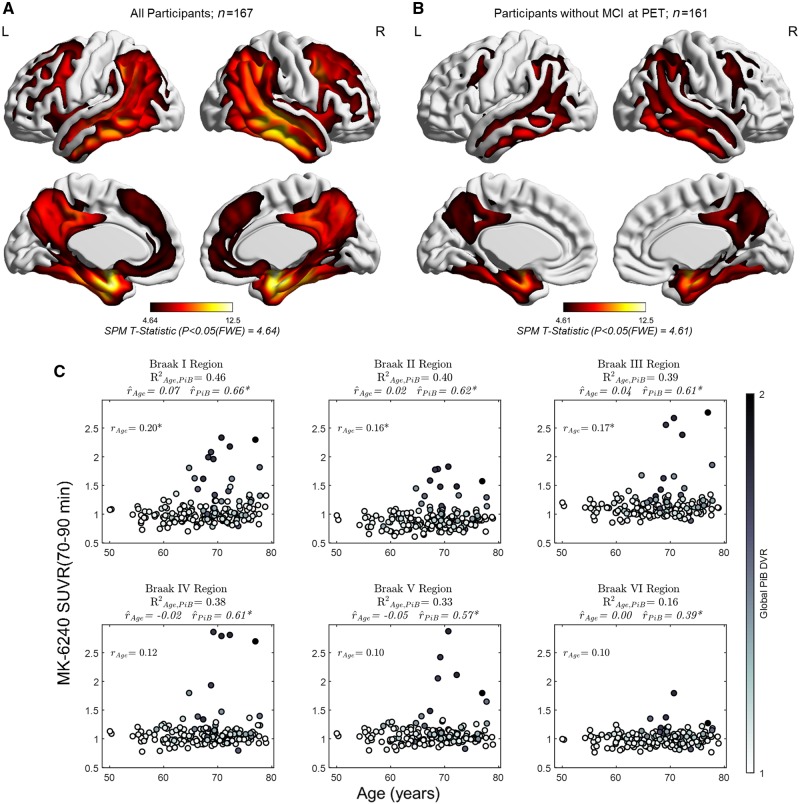

PET biomarkers and age

Voxelwise analyses examining the association between MK-6240 SUVR, global PiB DVR, and age indicated a significant positive association between MK-6240 and PiB (Fig. 3A) that spatially spanned regions associated with Braak neurofibrillary tangle stages I–V [P < 0.05 familywise error (FWE) corrected]. There were no significant voxelwise associations between MK-6240 and age or significant negative associations between MK-6240 and PiB after accounting for FWE (MK-6240 ∼ age + global PiB DVR + intercept). Sensitivity analysis of the voxelwise model including only persons unimpaired at the time of the MK-6240 scan (n = 161) restricted the spatial extent of the significant positive associations between MK-6240 and PiB (Fig. 3B), which was strongest for this subset in the medial temporal lobe at the level of the uncus, and extended into ventral and lateral temporal areas, the precuneus, posterior cingulate, inferior parietal cortex, and portions of the superior and middle frontal gyri.

Figure 3.

Associations between MK-6240, age and PiB. Surface rendered T-statistics of the positive association between MK-6240 and Global PiB DVR covaried for age for: (A) the entire study sample, and (B) in the subset without mild cognitive impairment at their PET scan. Images are thresholded such that t-statistics for voxels below the FWE-adjusted significance threshold are not shown. No negative associations with global PiB DVR or associations with age survived FWE correction (PFWE= 0.05) in the voxelwise analysis. Panel C shows the post hoc region of interest analyses in composite regions spanning Braak I–VI neurofibrillary tangle stages. The percentage of variance in MK-6240 explained by both global PiB DVR and age () is shown under the composite region name with the partial correlation between MK-6240 and age ( Age, global PiB DVR partialled out) and the partial correlation between MK-6240 and global PiB DVR (

Age, global PiB DVR partialled out) and the partial correlation between MK-6240 and global PiB DVR ( PiB, age partialled out) shown in the bottom of the title for each plot. The simple correlation between MK-6240 and age is shown in the top left corner of each plot. Region of interest analyses indicated small parametric associations with age, but these associations were mostly explained by global PiB DVR when partial correlations between MK-6240 and age and global PiB DVR were examined. The amount of variance in MK-6240 SUVR explained by PiB and age was highest in regions associated with early Braak neurofibrillary tangle staging, and decreased progressively in regions associated with later Braak stages. (C) *P < 0.05, unadjusted for multiple comparisons.

PiB, age partialled out) shown in the bottom of the title for each plot. The simple correlation between MK-6240 and age is shown in the top left corner of each plot. Region of interest analyses indicated small parametric associations with age, but these associations were mostly explained by global PiB DVR when partial correlations between MK-6240 and age and global PiB DVR were examined. The amount of variance in MK-6240 SUVR explained by PiB and age was highest in regions associated with early Braak neurofibrillary tangle staging, and decreased progressively in regions associated with later Braak stages. (C) *P < 0.05, unadjusted for multiple comparisons.

The region of interest-level analysis indicated the proportion of variance in MK-6240 SUVR explained by both global PiB DVR and age was highest in the Braak I region (entorhinal cortex; = 0.46) and decreased stepwise for composite regions representing later Braak neurofibrillary tangle stages (Fig. 3C; Braak II region = 0.40; Braak III region = 0.39; Braak IV region = 0.38; Braak V region = 0.33; Braak VI region = 0.16). Weak positive associations between MK-6240 SUVR and age were observed in regions associated with Braak neurofibrillary tangle staging (Braak I region rAge= 0.20; Braak II region rAge = 0.16; Braak III region rAge = 0.17; Braak IV region rAge = 0.12; Braak V region rAge = 0.10; Braak VI region rAge = 0.10), but partial associations between MK-6240 SUVR and age (partialling out global PiB DVR) were near zero (Braak I region  age = 0.07; Braak II region

age = 0.07; Braak II region  age = 0.02; Braak III region

age = 0.02; Braak III region  age = 0.04; Braak IV region

age = 0.04; Braak IV region  age = −0.02; Braak V region

age = −0.02; Braak V region  age = −0.05; Braak VI region

age = −0.05; Braak VI region  age = 0.00). Moderate to strong partial associations between MK-6240 SUVR and global PiB DVR (Braak I region

age = 0.00). Moderate to strong partial associations between MK-6240 SUVR and global PiB DVR (Braak I region  PiB = 0.66; Braak II region

PiB = 0.66; Braak II region  PiB = 0.62; Braak III region

PiB = 0.62; Braak III region  PiB = 0.61; Braak IV region

PiB = 0.61; Braak IV region  PiB = 0.61; Braak V region

PiB = 0.61; Braak V region  PiB = 0.57; Braak VI region

PiB = 0.57; Braak VI region  PiB = 0.39) were observed in neurofibrillary tangle-associated regions that decreased stepwise in regions associated with early to late neurofibrillary tangle stage. Similar results were observed in non-striatal exploratory regions (Supplementary Fig. 3). Striatal MK-6240 SUVR values were similar to values observed in the hippocampus of A− participants (mean MK-6240 SUVR: putamen = 0.92 ± 0.15; caudate = 0.76 ± 0.13), and differed between biomarker groups in the putamen (ANOVA, unadjusted P < 0.001; post hoc A+T+ > A−T− and A+T−) but not the caudate (ANOVA, unadjusted P = 0.06). In the striatum, the proportion of MK-6240 SUVR variability accounted for by both age and global PiB (caudate = 0.03; putamen = 0.12) and the partial association between PiB and MK-6240 SUVR (caudate

PiB = 0.39) were observed in neurofibrillary tangle-associated regions that decreased stepwise in regions associated with early to late neurofibrillary tangle stage. Similar results were observed in non-striatal exploratory regions (Supplementary Fig. 3). Striatal MK-6240 SUVR values were similar to values observed in the hippocampus of A− participants (mean MK-6240 SUVR: putamen = 0.92 ± 0.15; caudate = 0.76 ± 0.13), and differed between biomarker groups in the putamen (ANOVA, unadjusted P < 0.001; post hoc A+T+ > A−T− and A+T−) but not the caudate (ANOVA, unadjusted P = 0.06). In the striatum, the proportion of MK-6240 SUVR variability accounted for by both age and global PiB (caudate = 0.03; putamen = 0.12) and the partial association between PiB and MK-6240 SUVR (caudate  PiB = 0.17; putamen

PiB = 0.17; putamen  PiB = 0.25) were lower compared to neurofibrillary tangle-associated regions. A weak positive partial association was observed between MK-6240 SUVR and age in the putamen (

PiB = 0.25) were lower compared to neurofibrillary tangle-associated regions. A weak positive partial association was observed between MK-6240 SUVR and age in the putamen ( age = 0.20), but not the caudate (

age = 0.20), but not the caudate ( age = −0.02). In the A− group, minimal associations were observed between MK-6240 SUVR and age in all tested regions (R2 = 0.00 to 0.07; Supplementary Table 4).

age = −0.02). In the A− group, minimal associations were observed between MK-6240 SUVR and age in all tested regions (R2 = 0.00 to 0.07; Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This study investigated differences in retrospective cognitive trajectories between groups stratified on neurofibrillary tangles in the entorhinal cortex (MK-6240 PET) and cortical amyloid-β plaques (PiB PET) in late middle-aged, relatively healthy, initially cognitively unimpaired adults. The primary analysis indicated a significant group × age effect (i.e. cognitive trajectories differed between biomarker groups over time) such that individuals with evidence of both pathological amyloid-β and entorhinal tau exhibited steeper cognitive decline. This occurred during a period including ∼8 years leading up to PET imaging, beginning late in the fifth decade of life when all participants were cognitively unimpaired. Sensitivity analyses indicated these findings were robust when using the hippocampus and also with lower thresholds for T+ stratification in both the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. These results suggest the combination of PET measureable amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles accumulating in early neurofibrillary tangle stage regions are contributing to abnormal cognitive decline during late middle-age, several years prior to clinical impairment. This supports the construct of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease using PET biomarker stratification, and suggests that the period of measureable Alzheimer disease-related cognitive decline may begin earlier than previously proposed (Jack et al., 2013). These results also suggest that individuals with elevated amyloid-β burden (i.e. A+) comprise a group heterogeneous in cognitive trajectories wherein the differences are largely accounted for by neurofibrillary tangles, which has implications for studies investigating associations between amyloid-β and cognition where measures of tau pathophysiology are not available (Rowe et al., 2010; Pike et al., 2011).

The current work adds to the growing number of recent in vivo neuroimaging studies examining Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in cognitively unimpaired subjects (Scholl et al., 2016; Aschenbrenner et al., 2018; Knopman et al., 2019; Lowe et al., 2019; Sperling et al., 2019). This report is unique from these previous longitudinal studies in that participants are generally younger at their biomarker visits, the period of cognitive assessment is longer and extends into mid-life, and categorical biomarker groupings are used instead of continuous measures of amyloid-β and tau pathophysiology. Additionally, one study (Sperling et al., 2019) used a prospective design whereas all other longitudinal studies had cognitive data mostly precedent of neuroimaging. Comparisons of these studies may be precluded by a potential survivor effect in the previous reports due to applying cognitively unimpaired inclusion criteria to older adults, which would omit persons that have already succumbed to Alzheimer disease-induced cognitive impairment earlier in life. Despite study differences, the primary outcomes are mostly consistent across studies in that initially cognitively unimpaired persons with both elevated biomarkers for pathological amyloid-β and tau decline faster than those with just one or no elevated biomarkers. Considering the range in ages represented when comparing the previous studies with the present study may suggest that the joint contribution of amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles to accelerated cognitive decline is independent of age. Other studies using flortaucipir with different study designs (demographic difference, older sample, longitudinal and cross-sectional outcomes, and different statistical models) have suggested main effects of tau and amyloid on cognition without observing an interaction, which might suggest primary age-related tauopathy affecting cognition (Scholl et al., 2016; Lowe et al., 2019). This was not observed in the present study, even when using lower thresholds for stratifying elevated tau, likely because of infrequent observations of individuals with elevated tau and low levels of amyloid, and a lack of power to detect such an effect. In addition, there were no significant MK-6240 age-effects in A− cases suggesting primary age-related tauopathy was not measurable by MK-6240 in this younger sample. Further studies with larger samples of preclinical participants with more diverse representation are needed to assess to what extent these results are generalizable.

A primary goal of the WRAP study is to identify midlife features that contribute to later cognitive decline (Johnson et al., 2018). This work demonstrates that while individuals can have considerably different pathological amyloid and tangle burden, these groups were mostly similar in health characteristics at the beginning and end of the study period, and in cognitive features at the beginning of the study period. The absence of group differences does not necessarily mean that these features do not modify rates of cognitive decline. A recent study of a WRAP subsample that overlaps with the present study suggested that hypertension and obesity influence cognition in the presence of amyloid pathophysiology (Clark et al., 2018b). Combining the results of the present study with this previous work suggests that while the key drivers of preclinical cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease are likely amyloid and tau pathophysiology, other modifiable factors such as hypertension and obesity may moderate the effects of pathological amyloid and tau on cognition. Analyses investigating the moderating effects of lifestyle and health factors, including cerebrovascular, and the effects of pathological amyloid-β and tau on cognitive performance will be investigated in future WRAP studies.

The state (e.g. cleavage, phosphorylation, conformation, etc.) of amyloid-β and tau proteins has implications for PET and CSF biomarker affinity, sensitivity and biological inference (Mathis et al., 2017), which are relevant to the NIA-AA framework and the Alzheimer disease biomarker cascade model. The biomarker cascade model suggests that detectable pathological amyloid-β precedes detectable pathological tau, and that these processes occur primarily during the preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease (Jack et al., 2013). In support of the biomarker cascade model, the continuous distributions of amyloid and tau biomarkers suggested that individuals generally required higher levels of amyloid to exhibit higher levels of tau biomarkers. Notably, all A−T+ participants in this study had elevated MK-6240 only in the entorhinal cortex and generally did not show evidence of elevated MK-6240 in the hippocampus or elsewhere in the brain. Albeit cross-sectional, the prevalence of these biomarker-defined groups along with the spatial extent of imaging apparent tangle pathophysiology give further support that PET measureable amyloid-β plaque accumulation generally precedes even early stages (i.e. Braak I–II) of PET detectable tangle formation, although exceptions were present in this study. Group level comparisons also indicated that the group with elevated pathological amyloid-β and tau had a higher amyloid burden compared to individuals with only elevated amyloid-β suggesting that amyloid plaques are continuing to aggregate during the period tau aggregates are accumulating, which is consistent with the biomarker cascade model. Further studies are needed to ascertain whether PET measured tau pathophysiology in the entorhinal cortex is a suitable measure of disease or if other regions should be used for this purpose.

Because of limited sample size of elevated Alzheimer disease biomarker groups, we chose not to categorize neurodegeneration. Instead, group differences in hippocampal volume and global atrophy at the time of PET imaging were investigated to ascertain whether MRI appreciable neurodegeneration may be present in this mostly preclinical sample. Biomarker groups did not differ in global atrophy, but the A−T− group was statistically different from the A+T+ group in hippocampal volume. These findings give some evidence that neurodegeneration happens either concomitantly with or after PET measured pathophysiological amyloid-β and tau, but continued longitudinal observation with more subjects is needed to investigate this more directly in future analyses of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

A secondary goal of this study was to investigate MK-6240 in the contexts of age and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. In agreement with our previous findings of a smaller sample that included dementia cases (Betthauser et al., 2018), MK-6240 binding mostly follows the spatial hierarchy described by Braak and Braak (1991). In some T+ cases, unilateral patterns were observed, as were some cases where tangle pathophysiology appeared to ‘jump’ over a Braak stage, but these cases were infrequent. Regional and voxelwise analyses showed that a small age association exists with MK-6240 and age in neurofibrillary tangle-associated regions, but this association is mostly explained by PiB. In addition, there was no association between age and MK-6240 in A− persons. This may indicate that the observed MK-6240 binding is disease dependent, rather than an age-dependent phenomena such as primary age-related tauopathy or off-target binding. Pertaining to off-target binding, MK-6240 showed minimal to no association with age in the basal ganglia, and MK-6240 SUVRs in the basal ganglia were similar to SUVRs of A− subjects in tangle-associated regions and considerably lower than MK-6240 SUVRs in neurofibrillary tangle-associated regions of A+ individuals. In contrast, flortaucipir has been shown to have a partial correlation of 0.45 when partialling out amyloid-β, (Gordon et al., 2016) a simple age association of nearly 0.6 (Choi et al., 2018), and basal ganglia SUVR values in the same range or higher than SUVR values observed in amyloid-positive individuals (Johnson et al., 2015; Baker et al., 2019). Despite differences in apparent off-target binding, the main conclusions of studies using flortaucipir to investigate associations between tau, amyloid-β, age and cognition are mostly consistent with this MK-6240 study. However, the mechanisms and sites of off-target tau tracer binding, and the potential confounds they introduce for measuring tau pathophysiology should be understood before strong conclusions are made attributing imaging findings to pathological tau. In addition, imaging to post-mortem studies for various tau PET radioligands are needed to understand the detection limits of these tracers and PET imaging in relation to highly sensitive neuropathological methods in the context of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and primary age-related tauopathy.

In this study we chose to use categorical biomarker groups rather than continuous measures of amyloid-β and tau pathophysiology. This was done in part to minimize the influence of negative cases (∼75% of the sample) on model residuals that would occur with continuous analysis, mitigate potential nonlinear effects between amyloid, tau, and cognitive trajectories, and to test the NIA-AA Research Framework in the context of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Defining cut-offs for biomarker abnormality can be problematic in the absence of imaging to post-mortem correlates wherein the underlying pathology is known. As pathology data are not yet available for MK-6240, we chose to generate a threshold for elevated MK-6240 based on evidence from pathology and other Alzheimer’s disease biomarker studies that cognitively unimpaired, amyloid negative persons typically do not have elevated pathological tau (Clark et al., 2018a; Kern et al., 2018). We chose to interpret T+ groups as having evidence of elevated tangle pathophysiology, and used the distinction of T+/− for practicality in presentation. Importantly, main model outcomes related to longitudinal cognitive decline were highly consistent when using lower thresholds and the hippocampus to define T+ status. Compared to using continuous measures of AD pathophysiology, categorical biomarker variables allow for similar analyses to be performed with fewer predictors and fewer interactions in linear models, and the results are less prone to being driven by extreme points in the data (e.g. individuals with floridly high amyloid-β or tangle burden). It is notable that even with the methodology applied in this study, the results are highly consistent with other neuroimaging studies (Aschenbrenner et al., 2018; Knopman et al., 2019; Sperling et al., 2019), and the frequencies of individuals in pathophysiological amyloid and tau biomarker groups are consistent with CSF studies in similar populations (Kern et al., 2018) and a CSF study with an overlapping sample of participants (Clark et al., 2018a). Future work will investigate to what extent these findings are consistent with fluid biomarkers in WRAP in cases that have both imaging and fluid biomarkers available.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that the combination of pathological amyloid-β and tau is a key driver of accelerated longitudinal cognitive decline occurring during late middle-age in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Further, the results suggest that Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive decline occurring during late middle-age is not greatly influenced by potential comorbid diseases such as vascular disease. Follow-up studies in larger preclinical samples are needed to determine if amyloid or tau individually can impact longitudinal preclinical cognitive decline. MK-6240 appears to be sensitive to detect neurofibrillary tangles present in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants and their families, and the many study teams at the University of Wisconsin that make this work possible. Additionally we would like to acknowledge Cerveau Technologies for providing MK-6240 standard and precursor.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Alzheimer's Association for financial support of this work under the following grants: NIH R01 AG021155, R01 AG027161, NIH P50 AG033514, NIH U54 HD090256, AARF-19-614533.

Competing interests

18F-MK-6240 precursor and reference standard used in this study were provided by Cerveau Technologies. S.C.J. is PI for a separate ongoing study using MK-6240 sponsored by Cerveau Technologies and served as a consultant to Roche Diagnostics. H.A.R. is a consultant for GE HealthCare and has equity interest in ImageMoverMD. All other authors have no relevant disclosures.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- A+/− =

elevated or non-elevated global PiB DVR

- DVR =

distribution volume ratio

- PACC-3 =

three-test preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite

- PiB =

11C-Pittsburgh compound B

- SUVR =

standard uptake value ratio

- T+/− =

elevated or non-elevated entorhinal 18F-MK-6240 SUVR

- WRAP =

Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention

See Schöll and Maass (doi:10.1093/brain/awz399) for a scientific commentary on this article.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7: 270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrenner AJ, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC, Hassenstab JJ. Influence of tau PET, amyloid PET, and hippocampal volume on cognition in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2018; 91: e859–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SL, Harrison TM, Maass A, La Joie R, Jagust W. Effect of off-target binding on (18)F-Flortaucipir variability in healthy controls across the lifespan. J Nucl Med 2019; 60: 1444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betthauser TJ, Cody KA, Zammit MD, Murali D, Converse AK, Barnhart TE, et al. In vivo characterization and quantification of neurofibrillary tau PET radioligand (18)F-MK-6240 in humans from Alzheimer disease dementia to young controls. J Nucl Med 2018; 60: 93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 2006; 112: 389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991; 82: 239–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Cho H, Ahn SJ, Lee JH, Ryu YH, Lee MS, et al. Off-target (18)F-AV-1451 binding in the basal ganglia correlates with age-related iron accumulation. J Nucl Med 2018; 59: 117–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LR, Berman SE, Norton D, Koscik RL, Jonaitis E, Blennow K, et al. Age-accelerated cognitive decline in asymptomatic adults with CSF beta-amyloid. Neurology 2018a; 90: e1306–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LR, Koscik RL, Allison SL, Berman SE, Norton D, Carlsson CM, et al. Hypertension and obesity moderate the relationship between beta-amyloid and cognitive decline in midlife. Alzheimers Dement 2018b; 15: 418–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006; 31: 968–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, Rentz DM, Raman R, Thomas RG, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 961–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 12: 292–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon BA, Friedrichsen K, Brier M, Blazey T, Su Y, Christensen J, et al. The relationship between cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer pathology and positron emission tomography tau imaging. Brain 2016; 139 (Pt 8): 2249–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler ED, Walji AM, Zeng Z, Miller P, Bennacef I, Salinas C, et al. Preclinical characterization of 18F-MK-6240, a promising PET tracer for in vivo quantification of human neurofibrillary tangles. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018; 14: 535–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 207–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2015; 79(1): 110–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, Oh JM, Harding S, Xu G, et al. Amyloid burden and neural function in people at risk for Alzheimer's Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2014; 35: 576–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Clark LR, Mueller KD, Berman SE, et al. The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention: A review of findings and current directions. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2018; 10: 130–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonaitis EM, Koscik RL, Clark LR, Ma Y, Betthauser TJ, Berman SE, et al. Measuring longitudinal cognition: individual tests versus composites. Alzheimers Dementia 2019; 11: 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med 1994; 24: 145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern S, Zetterberg H, Kern J, Zettergren A, Waern M, Hoglund K, et al. Prevalence of preclinical Alzheimer disease: comparison of current classification systems. Neurology 2018; 90: e1682–e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Lundt ES, Therneau TM, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, Kantarci K, et al. Entorhinal cortex tau, amyloid-beta, cortical thickness and memory performance in non-demented subjects. Brain 2019; 142: 1148–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R. Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means [R package emmeans version 1.4.2] [Internet]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network [cited 2019 Nov 26]; 2019. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html

- Lohith TG, Bennacef I, Vandenberghe R, Vandenbulcke M, Salinas CA, Declercq R, et al. Brain imaging of Alzheimer dementia patients and elderly controls with (18)F-MK-6240, a PET tracer targeting neurofibrillary tangles. J Nucl Med 2018; 60: 107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe VJ, Bruinsma TJ, Wiste HJ, Min HK, Weigand SD, Fang P, et al. Cross-sectional associations of tau-PET signal with cognition in cognitively unimpaired adults. Neurology 2019; 93: e29–e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis CA, Lopresti BJ, Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE. Small-molecule PET tracers for imaging proteinopathies. Semin Nucl Med 2017; 47: 553–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7: 263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012; 123: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino EC, Papp KV, Rentz DM, Donohue MC, Amariglio R, Quiroz YT, et al. Early and late change on the preclinical Alzheimer's cognitive composite in clinically normal older individuals with elevated amyloid-β. Alzheimers Dement 2017; 13: 1004–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal TA, Shin M, Kang MS, Chamoun M, Chartrand D, Mathotaarachchi S, et al. In vivo quantification of neurofibrillary tangles with [(18)F]MK-6240. Alzheimers Res Ther 2018; 10: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KE, Ellis KA, Villemagne VL, Good N, Chetelat G, Ames D, et al. Cognition and beta-amyloid in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: data from the AIBL study. Neuropsychologia 2011; 49: 2384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D R Core Team. Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models [R package nlme version 3.1-142] [Internet]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network [cited 2019 Nov 26]; 2019. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/index.html

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Racine AM, Clark LR, Berman SE, Koscik RL, Mueller KD, Norton D, et al. Associations between performance on an abbreviated CogState battery, other measures of cognitive function, and biomarkers in people at risk for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 54: 1395–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977; 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, Bourgeat P, Pike KE, Jones G, et al. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging 2010; 31: 1275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. Rey auditory verbal learning test: A handbook. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scholl M, Lockhart SN, Schonhaut DR, O'Neil JP, Janabi M, Ossenkoppele R, et al. PET imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron 2016; 89: 971–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7: 280–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Mormino EC, Schultz AP, Betensky RA,, Papp KV, Amariglio RE, et al. The impact of amyloid-beta and tau on prospective cognitive decline in older individuals. Ann Neurol 2019; 85: 181–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher KE, Bendlin BB, Racine AM, Okonkwo OC, Christian BT, Koscik RL, et al. Amyloid burden is associated with self-reported sleep in nondemented late middle-aged adults. Neurobiol Aging 2015; 36: 2568–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002; 58: 1791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschanz JT, Corcoran CD, Schwartz S, Treiber K, Green RC, Norton MC, et al. Progression of cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric symptom domains in a population cohort with Alzheimer dementia: the Cache County Dementia Progression study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011; 19: 532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]