Abstract

Background:

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is preventable, it is increasing in prevalence, and it is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality. Importantly, residents of neighborhoods with high levels of disorder are more likely to develop T2D than those living in less disordered neighborhoods and neighborhood disorder may exacerbate genetic risk for T2D.

Method:

We use genetic, self-reported neighborhood, and health data from the Health and Retirement Study. We conducted weighted logistic regression analyses in which neighborhood disorder, polygenic scores for T2D, and their interaction predicted T2D.

Results:

Greater perceptions of neighborhood disorder (OR = 1.11, p < 0.001) and higher polygenic scores for T2D (OR = 1.42, p < 0.001) were each significantly and independently associated with an increased risk of T2D. Furthermore, living in a neighborhood perceived as having high levels of disorder exacerbated genetic risk for T2D (OR = 1.10, p = 0.001). This significant gene × environment interaction was observed after adjusting for years of schooling, age, gender, levels of physical activity, and obesity.

Conclusion:

Findings in the present study suggested that minimizing people’s exposure to vandalism, vacant buildings, trash, and circumstances viewed by residents as unsafe may reduce the burden of this prevalent chronic health condition, particularly for subgroups of the population who carry genetic liability for T2D.

Keywords: GENETICS, Neighborhood/place, DIABETES

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a leading risk factor for cardiovascular and cancer-related morbidity and mortality, is increasing in prevalence worldwide, and is preventable[1]. Many factors contribute to the development of T2D, including individual characteristics (e.g., physical activity, genetic risk[2]) and broad social factors (e.g., lack of outlets for physical activity[3]). Many individual behaviors are either supported or constrained by features of people’s neighborhoods, such as resources that support physical activity[4]. Some have therefore theorized that neighborhood features relate to residents’ health through people’s health behaviors[5].

Very little work has evaluated the extent to which neighborhood disorder relates to T2D through interactions with genetic risk. A number of genetic loci increase the risk of T2D, and the heritability of T2D ranges from 20–80%[6]. A growing literature indicates that T2D is the result of interactions between genotype and environment (GxE), where genetic risk for T2D is heightened by factors such as sedentary lifestyles and obesity[7]. We believe that these lifestyles are downstream of more fundamental social factors such as the places in which people live[8]. In the present study, we examined whether increased perceptions of neighborhoods disorder exacerbate genetic risk for T2D.

Neighborhoods and Diabetes

People living in neighborhoods perceived to be disordered (e.g., unsafe, vandalized) report more chronic health conditions including diabetes[9]. This relationship is posited to be established through a sense of fear[10] which results in a state of physiological vigilance[11] and unwillingness to engage in outdoor physical activity. Moreover, neighborhood disorder was found to completely explain the well-established association between neighborhood economic disadvantage and poorer health[9]. These findings suggest that efforts to improve neighborhood conditions may also reduce community-level burden of disease.

Findings from the Moving to Opportunities Study, one of the few examples of a randomized control study of neighborhoods and health, suggest that people who move out of high-poverty areas have reduced prevalence of diabetes and extreme obesity[12]. Findings such as these support the causal hypothesis of neighborhoods, or that neighborhood poverty is uniquely associated with an increased risk for cardiometabolic diseases. Coupled with research indicating that neighborhood disorder mediates the neighborhood poverty-T2D association, there is strong reason to believe that efforts to mitigate neighborhood disorder may help to slow the rapidly growing population of individuals affected by T2D and other chronic health conditions.

Diabetes and GxE

A diagnosis of T2D is thought to be a consequence of both genetic and environmental influences[6] and some argue that genetic influences only manifest in certain environments[7]. Evidence in support of this argument aligns with the social trigger GxE hypothesis which posits that adverse environmental features strengthen the genotype-outcome association[13]. For instance, although specific genetic variants explain only a small proportion of variance in the likelihood of developing T2D[6], those carrying these variants who also engage in sedentary behaviors are at an increased risk of disease[7]. This literature has established the importance of considering both genetic and environmental processes in the development of T2D, and the importance of moving beyond the candidate gene approach. Complex traits, including those with relevance in public health, are polygenic, or influenced by multiple genetic regions[14]. As such, GxE investigations would benefit from the inclusion of summary genetic scores that account for a greater portion of variance in the health outcome than can be observed with single genetic variants[15].

Recent research has investigated GxE occurring within the larger environments in which people live. For instance, youth are at increased risk of obesity, an outcome strongly associated with T2D[16], when they carry genetic variants for higher body mass index and attend schools with fewer resources to maintain a healthy weight[17]. It follows, then, that resources (or lack thereof) within neighborhoods may further interact with genetic risk for T2D. Despite current evidence for GxE in relation to cardiometabolic outcomes[17], however, existing reviews[18] demonstrate a paucity of research on potential interactions with neighborhood disorder (although see[19] for a GxE in relation to waking cortisol). Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to neighborhood disorder, not only through age-related declines in cognitive and physical health and functioning[20], but also because many chronic cardio-metabolic diseases become apparent in older adulthood. Given that incident T2D is increasing rapidly worldwide[1], it is critical to investigate whether modifiable features of neighborhoods contribute to this public health issue.

The Present Study

The goal of the present study is to examine whether perceptions of neighborhood disorder trigger or exacerbate genetic risk for T2D. This study adds to the growing body of research investigating GxE in the context of people’s larger environments which has already demonstrated interactions with school-level factors[17]. We will use a polygenic score (PGS) for T2D that summarizes genome-wide genetic risk, rather than focusing on any single genetic region. By conducting this research with a nationally representative sample of older adults, findings from this research may inform intervention efforts aimed at containing the population of individuals affected by T2D.

Method

Participants and Procedures

We used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) national survey, the purpose of which was to examine health and retirement among United States men and women over 50 years of age. Starting in 1992, participants’ economic, physical, mental, and cognitive well-being have been assessed every two years. The sample is refreshed every six years by adding people aged 51–56 to maintain representativeness of the population over 50. As part of the core HRS interviews, respondents reported any chronic health conditions they had. In 2006, HRS researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with a random half of households. During these interviews, Buccal swabs were used to collect DNA samples. In 2008, DNA was extracted from saliva samples from participants in the other half of HRS households. These samples have been combined and genotyped. HRS researchers also collected anthropometric data from participants, including height and weight. During these interviews, participants completed psychosocial questionnaires including items assessing neighborhood disorder. The questionnaire was administered again in 2010 (a follow-up from 2006) and 2012 (a follow-up from 2008), and the present study included the most recent responses to the items assessing T2D and neighborhood disorder. All participants signed separate consent forms prior to providing biological samples and all research procedures were approved by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board.

The PGSs used in the present analyses were constructed using data from non-Hispanic whites and may therefore not have the same predictive ability among those from other racial/ethnic groups[21–22]. As such, the analytic sample in the present study was restricted to those who self-reported non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity and who had T2D PGSs (n = 12,090). Of those 12,090 participants, 1527 did not complete additional waves of the HRS after genetic data were collected in 2006/2008, 1643 did not return the psychosocial questionnaire with items assessing neighborhood disorder, and 288 did not complete the core interview including questions about T2D. A smaller group of individuals did not respond to questions assessing T2D (n = 3), neighborhood disorder (n = 5), and physical activity (n = 26), resulting in an analytic sample of 8,588 respondents.

Measures

Diabetes.

As part of the core HRS interview, participants answered the question, ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes or high blood sugar?’ At the time the question was answered, HRS interviewers had knowledge regarding whether the respondents had reported having diabetes in previous waves of the survey. Respondents were coded as having diabetes (scored 1) if they currently or had previously reported having diabetes, and were coded as not having diabetes (scored 0) if they currently did not or disputed ever having had diabetes.

Neighborhood disorder.

Participants responded to four questions regarding neighborhood disorder[23]. Item responses, which ranged from 1–7, indicated the degree to which participants perceived vandalism, trash, and vacant buildings in their neighborhoods as well as the degree to which they believed people would feel safe walking in their neighborhoods alone. Items assessing vandalism, safety, and vacant buildings were reverse-coded and all responses were averaged so that higher scores indicated greater perceived neighborhood disorder (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Genetic data.

At the Center for Inherited Disease Research[24], DNA was genotyped using the Illumina HumanOmni2.5–4v1 array. Roughly 2.4 million SNPs were measured, of which roughly 1.9 million passed quality control procedures (see[25] for quality assurance/quality control procedures). At the University of Washington Genetics Coordinating Center, roughly 21 million SNPs were examined for allele status using Imputation to the 1000 Genomes Project[24].

In a meta-analysis of 12 genome-wide association studies including 34,840 cases and 114,981 controls of European descent, researchers identified 10 novel genome-wide significant loci for T2D, and provided a supplementary table listing all genome-wide significant single polymorphisms[26]. Based on this meta-analysis, HRS researchers constructed a T2D polygenic score among non-Hispanic whites[27]. In the construction of the scores, all genotyped SNPs were used (no imputed SNPs and no clumping or pruning based on linkage disequilibrium). Scores were constructed by summing the weighted beta estimates. Final T2D polygenic scores were standardized among non-Hispanic whites (mean =0, sd = 1). To adjust for potential population stratification, or that people from different racial/ethnic backgrounds may have differing genetic structures[28], the top five principal components[27] were included as covariates in statistical models.

Additional covariates.

HRS respondents indicated the number of days they had engaged in vigorous (e.g., running, cycling, swimming, digging with a shovel), moderate (e.g., gardening, cleaning the car, dancing, walking, stretching), or light (e.g., vacuuming, laundry) physical activity with the following scale: 1 = never, 2 = 1–3 times per month, 3 = one time per week, 4 = more than one time per week, and 5 = every day. In the present study, this information came from the RAND HRS file[29]. In the present study, the total number of days reported in each of these levels of physical activity were weighted so that vigorous activity (multiplied by 5; score ranged from 5–25) received greater weight than moderate activity, which received greater weight (multiplied by 3; score ranged from 3–15) than light activity (multiplied by 1; score ranged from 1–5). A summary physical activity variable was constructed that summed across the weighted number of days reported in each of these levels of physical activity (score ranged from 9–45).

Height and weight assessed in the face-to-face interviews were used to construct a measure of body mass index (BMI), calculated as the ratio of a person’s weight in kilograms to height in meters squared. Using this formula, participants were categorized as obese if this ratio were at or greater than 30. Participants reported the total number of years of schooling they had completed. We also included age and gender as covariates.

Statistical analyses.

We survey set the data to accommodate the complex survey design in HRS. We used the svy: suite of commands in Stata 13 to conduct logistic regressions examining T2D. Before testing the key hypothesis for GxE in the present study, potential rGE, or correlation between the polygenic score for T2D and perceptions of neighborhood disorder were assessed. To this aim, we evaluated two models, one in which perceptions of neighborhood disorder were regressed on the T2D polygenic score, and the other in which T2D polygenic scores were regressed on perceptions of neighborhood disorder. Both of these models were adjusted for age, gender, years of schooling, physical activity, obesity, and principle components.

In our first logistic model predicting T2D, we tested the hypotheses that higher polygenic scores for T2D and neighborhood disorder would each be related to increased odds of T2D, adjusting for age, gender, years of schooling, self-reported physical activity, obesity, and principle components. Model 2 additionally included an interaction term; we examined whether higher perceptions of neighborhood disorder would strengthen the hypothesized association between the T2D outcome and polygenic scores (GxE). In Model 3, interactions between all covariates (age, gender, years of schooling, physical activity, and obesity) and both predictors (perceptions of neighborhood disorder and polygenic scores for T2D) were included as covariates[30].

Results

About 19 percent of the weighted sample reported having been told by a doctor that he or she had T2D either at present or some point in the past. Roughly 41% of the sample was categorized as obese, with a BMI at or greater than 30. On a scale from 1–7, participants reported low levels of disorder (mean = 2.36, sd = 0.02). The weighted sample was fairly physically active and well-educated, with average scores of 24.02 on the summary measure of physical activity (sd = 0.11, on a scale from 9–45) and 13.88 years of schooling (sd = 0.07), on average. Participants were, on average, 66.53 years of age (sd = 0.11) and there were more women (53.58%) than men. Regression models evaluating potential rGE, or the possibility that polygenic scores for T2D and perceptions of neighborhood disorder are significantly associated with one another, yielded null results (p = 0.186, p = 0.186, respectively).

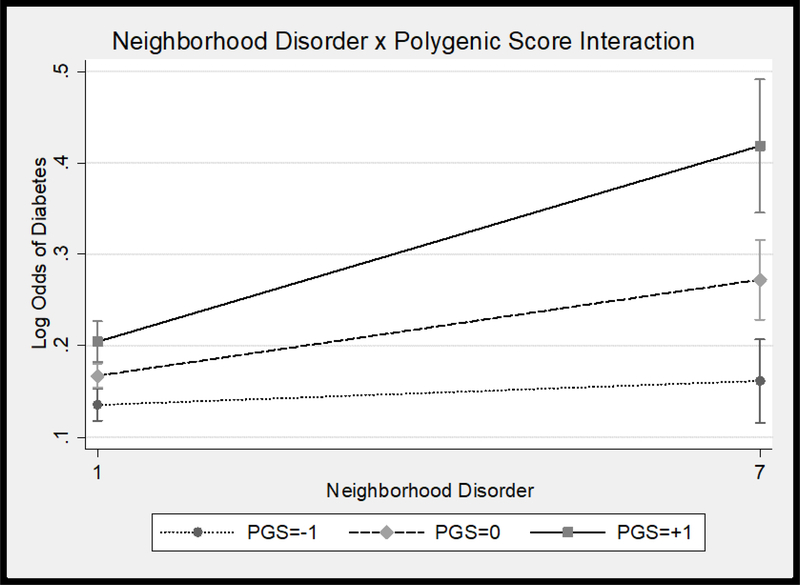

Results of logistic regression models predicting T2D are presented in Table 1. Model 1 results indicated that higher T2D polygenic scores and perceptions of neighborhoods disorder were significantly associated with greater odds of having T2D. Men, older adults, those categorized as obese, and those who engaged in less physical activity were more likely to have T2D than women, younger adults, those not categorized as obese, and those who were more physically active. We tested our primary hypothesis that higher neighborhood disorder would trigger genetic risk for T2D in Model 2. The interaction between neighborhood disorder and T2D polygenic scores was significant (see Figure 1); higher T2D polygenic scores were associated with greater risk of T2D, and this was even more so for those living in neighborhoods perceived as having higher levels of disorder. This interaction remained statistically significant in Model 3 when the covariate × T2D polygenic score and covariate × perceptions of neighborhood disorder interactions were added.

Table 1.

Main and interactive effects of T2D polygenic score and neighborhood disorder on T2D: Logistic regressions

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | 95% CI | OR | p | 95% CI | OR | p | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.04, 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.05, 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.14, 0.19 |

| Neighborhood Disorder | 1.11 | 0.001 | 1.05, 1.17 | 1.10 | 0.001 | 1.04, 1.16 | 1.12 | 0.016 | 1.02, 1.24 |

| T2D Polygenic Score | 1.42 | 0.001 | 1.29, 1.56 | 1.42 | 0.001 | 1.29, 1.56 | 1.23 | 0.010 | 1.05, 1.44 |

| Disorder × Polygenic Score | 1.09 | 0.001 | 1.03, 1.15 | 1.10 | 0.001 | 1.04, 1.16 | |||

| Physical Activity | 0.97 | 0.001 | 0.96, 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.001 | 0.96, 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.001 | 0.96, 0.97 |

| Years of Schooling | 1.00 | 0.547 | 0.99, 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.546 | 0.99, 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.453 | 0.99, 1.02 |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.001 | 1.01, 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.001 | 1.01, 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.001 | 1.01, 1.03 |

| Gender a | 0.70 | 0.001 | 0.61, 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.001 | 0.61, 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.001 | 0.61, 0.81 |

| Obese b | 2.82 | 0.001 | 2.43, 3.28 | 2.83 | 0.001 | 2.44, 3.29 | 2.82 | 0.001 | 2.43, 3.27 |

Men = 0, Women = 1;

0 = not obese, 1 = obese

Note. All ORs adjusted for principal components. Model 3 further adjusted for the covariate × perceived disorder and covariate × PGS interactions, with continuous variables mean centered for interpretation of main effects.p values < 0.001 listed as 0.001.

Figure 1.

Neighborhood disorder × T2D polygenic score interaction

Discussion

It has already been established that both individual- and neighborhood-level factors are related to the development of T2D[2]. Furthermore, researchers have posited that both genetic susceptibility and some exogenous ‘diabetogenic’ trigger are prerequisites in the development of Type I diabetes[31]. In support of our hypothesis, results from the present study suggest a similar triggering of the disease process with regards to T2D, and specifically indicates that exposure to neighborhood disorder may exacerbate individuals’ genetic predisposition for T2D.

That individual characteristics may moderate the association between neighborhood features and health is not a new concept. However, extant examples generally find that those with greater social ties[32] or higher individual socioeconomic status[33], both representing individual social characteristics, fare better in more adverse neighborhood environments. The novel finding in the present study is that an additional individual characteristic, people’s underlying genetic vulnerability to T2D, interacts with features of the neighborhood (i.e., perceptions of disorder).

Although evidence indicating the health-relevance of neighborhood features for residents’ health has been growing substantially in recent decades[5], efforts to make health salutary neighborhood change have been slower to progress[34]. Reasons for the apparent disconnect between the evidence base and policy change include lack of clarity regarding the specific neighborhood features that associate with residents’ health[34] as well as relatively small neighborhood effects sizes[35]. Results from the present study may inform solutions to these obstacles. First, we focused on a specific feature of residents’ neighborhoods, i.e., perceptions of disorder. Second, we showed that the strength of the association between neighborhood disorder and T2D depended on residents’ genotypes for SNPs related to T2D. This is important because it suggests that neighborhood effects may have been underestimated in previous investigations reporting only average neighborhood effects. Taken together, our findings suggest that minimizing residents’ exposure to neighborhood disorder may reduce incident T2D at community levels.

A clear limitation of the present study was the restricted sample. Given that the polygenic scores used in the present study were derived from individuals of European descent, the present analyses included only those self-reporting as non-Hispanic white. This restriction minimizes generalizability of the findings. Generalizability may be of particular concern in the present study for two reasons. First, non-Hispanic white individuals generally reside in less disordered neighborhoods compared to racial and ethnic minorities[36]. Indeed, the non-Hispanic white participants in the present study generally reported low levels of neighborhood disorder. Second, a related but distinct phenomenon is that which indicates people perceive more disorder in neighborhoods with a greater number of racial/ethnic, particularly Latino or black, residents[36]. It is therefore critical that future tests of these questions include racial/ethnic minorities, both in the construction of polygenic scores, and in the investigation of GxE.

In the present study, neighborhood disorder was reported by the respondents. One concern regarding self-reported neighborhood indicators involves common source bias, or that individuals who view their experiences through a negative lens may over-estimate levels of disorder in their neighborhoods. However, researchers have directly compared objectively assessed and self-reported levels of neighborhood disorder and have found that these assessments are highly correlated[37]. Moreover, given the intimate nature of the data, some have argued that the ideal informant regarding daily levels of disorder and other social processes within a neighborhood are the residents themselves[38]. Nevertheless, future research may benefit from the inclusion of measures of neighborhood disorder from outside raters. As stated elsewhere [39] this suggestion is in line with recommendations regarding the inclusion of multidimensional and multilevel characteristics of the built and social environment in order to properly understand the full contours of environmental moderation of genetic influences on health. Lastly, although we included years of schooling as a covariate in our models (which neither interacted with T2D polygenic scores nor perceptions of neighborhood disorder), future research may be strengthened with the inclusion of objective measures of neighborhood socioeconomic standing.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present analyses represent the first investigation of potential neighborhood GxE in relation to T2D, and suggest that one way by which neighborhoods establish their associations with T2D may be through a triggering of genetic risk. Findings support the notion that neighborhood improvement efforts, perhaps by reinvesting in community-building surveillance, building repairs, and other maintenance programs may assist in curbing an important current public health concern.

What is already known on this subject?

People who live in disordered neighborhoods, i.e., those with more trash and vandalism, generally have poor health. Exposure to neighborhood disorder is associated with an increased risk for Type II Diabetes, for example, which is a highly heritable health outcome. A large literature suggests individual differences in susceptibility, however, with neighborhood disorder related to worse health consequences for some than others.

What does this study add?

Results from the present study suggest that exposure to neighborhood disorder ‘triggers’ genetic risk for Type II Diabetes. Although living in a neighborhood perceived to have high levels of disorder increases peoples’ risk for Type II Diabetes, this is even more so for those genetically predisposed to the disease. This finding may help to explain individual differences in susceptibility to neighborhood disorder, and supports efforts for neighborhood improvement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was based upon work supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging training grant (T32-AG000037-37) and a National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging career development grant (1K99AG055699-01) to[JWR]. These sources of funding supported the data analysis and writing of this report. The data collection for the Health and Retirement Study is also supported by the National Institute on Aging (U01 AG009740).

Footnotes

Licence for Publication

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in JECH and any other BMJPGL products and sublicences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms).

Competing Interest: None declared.

Contributor Information

Jennifer W Robinette, Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, 3715 McClintock Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0191.

Jason D Boardman, Institute of Behavioral Science and Department of Sociology, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1440 15th Street, Boulder, CO, 80309.

Eileen Crimmins, Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, 3715 McClintock Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0191.

References

- 1.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care 2012;35;1364–1379. 10.2337/dc12-0413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaMont MJ, Blair SN, Church TS. Physical activity and diabetes prevention. J Appl Physiol 2005;99;1205–1213. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00193.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, et al. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood physical and social environments and incident Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). JAMA Intern Med 2015;175;1311–1320. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank LD, Schmid TL, Sallis JF, et al. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form. Am J Prev Med 2005;28;117–125. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diez Roux AV & Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010;1186;125–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al O. Genetic of type 2 diabetes. World J Diabetes 2013;4;114–123.doi: 10.4239/wjd.v4.i4.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeghate E, Schattner P, & Dunn E. An update on the etiology and epidemiology of diabetes mellitus. Ann NY Acad Sci 2006;1084;1–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1372.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooney SJ, Joshi J, Cerda M, et al. Neighborhood disorder and Physical activity among older adults: A longitudinal study. J Urban Health 2017;94;30–42. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0125-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross CE, Mirowski J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder and health. J Health Soc Behav 2001;42;258–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross CE, Jang SJ. Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: The buffering role of social times with neighbors. Am J Community Psychol 2000;28;401–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinette JW, Charles ST, Gruenewald TL. Neighborhood cohesion, neighborhood disorder, and cardiometabolic risk. Soc Sci Med 2017;198;70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and Diabetes – A randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med 2011;365;1509–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanahan MJ, Hofer SM. Social context in gene-environment interactions: retrospect and prospect. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60;65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle EA, Li YI, Pritchard JK. An expanded view of complex traits: From polygenic to omnigenic. Cell 2017;169;1177–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boardman JD, Domingue BW, Blalock CL, et al. Is the gene-environment interaction paradigm relevant to genome-wide studies? The case of education and body mass index. Demography 2014;51;119–139. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0259- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckel RH, Kahn SE, Ferrannini E, et al. Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: What can be unified and what needs to be individualized? Diabetes Care 2011;34;1424–1430. 10.2337/dc11-0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boardman JD, Roettger ME, Domingue BW, et al. Gene-environment interactions related to body mass: School policies and social context as environmental moderators. J Theor Polit 2012;24;370–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franks PW. Gene × environment interactions in Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rep 2011;11;552–561. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0224-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulon SM, Wilson DK, van Horn ML, et al. The association of neighborhood gene-environment susceptibility with cortisol and blood pressure in African-American adults. Ann Behav Med 2016;50;98–107. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9737-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass TA, Balfour JL. Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin AR, Gignoux CR, Walters RK, et al. Human demographic history impacts genetic risk prediction across diverse populations. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100;635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware EB, Schmitz LL, Faul JD, et al. Method of Construction Affects Polygenic Score Prediction of Common Human Traits. BiorXiv. 2017. doi: 10.1101/106062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendes de Leon CF, Cagney KA, Bienias JL, et al. Neighborhood social cohesion and disorder in relation to walking in community-dwelling older adults: A multilevel analysis. J Aging Health 2009;21;155–171. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Inherited Disease Research, Health and Retirement Study. (2012). Imputation report – 1000 Genomes project reference panel. Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/genetics/HRS_1000G_IMPUTE2_REPORT_AUG2012.pdf

- 25.Weir DR. 2012. Quality Control Report for Genotypic Data. Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/genetics/HRS_QC_REPORT_MAR2012.pdf

- 26.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nature Genet 2012;44;981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware E, Schmitz L, Gard A, et al. 2018. HRS Polygenic Scores – Release 2 2006–2012 Genetic Data. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novembre J, Stephens M. Interpreting principal component analyses of spatial population genetic variation. Nature Genet 2008;40;646–649. doi: 10.1038/ng.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bugliari D, Campbell N, Chan C, et al. RAND HRS Data Documentation (Version P). 2016; Retrieved from Health and Retirement Study website: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/rand/randhrsp/randhrs_P.pdf

- 30.Kelle M. Gene × environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: The problem and the (simple) solution. Biological Psychiatry 2014;75;18–24. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knip M, Veijola R, Virtanen SM, et al. Environmental triggers and determinants of type I diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54;S125–S136. 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.S125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klijs B, Mendes de Leon C, Kibele EUB, et al. Do social relations Buffer the effect of neighborhood deprivation on health-related quality of life? Results from the LifeLines Cohort Study. Health and Place 2017;44;43–51. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 2001;42;151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haymann J, Fischer A. Neighborhoods, health research, and its relevance to public policy In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55;111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood stigma and the perception of disorder. Focus 2005;24;7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elo IT, Mykyta L, Margolis R, et al. Perceptions of neighborhood disorder: The role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Socl Sci Quart 2009;90;1298–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00657.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raudenbush SW. The quantitative assessment of neighborhood social environments In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and Health New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boardman JD., Daw J., & Freese J. Defining the environment in gene–environment research: lessons from social epidemiology. Am J Pub Hlth 2013; 103(S1), S64–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]