Abstract

The oxadi-π-methane rearrangement of 2,4-cyclohexadienones to bicyclic ketones was found to proceed with high enantioselectivity (92–97% ee) in the presence of catalytic amounts of a chiral Lewis acid (15 examples, 52–80% yield). A notable feature of the transformation is the fact that it proceeds on the singlet hypersurface and that no triplet intermediates are involved. Rapid racemic background reactions were therefore avoided, and the catalyst loading could be kept low (10 mol %). Computational studies suggest that the enantioselectivity is determined within a Lewis acid bound singlet intermediate via a conical intersection. The utility of the method was demonstrated by a concise synthesis of the natural product trans-chrysanthemic acid.

The construction of a complex molecular skeleton in a single step is arguably the most fascinating hallmark of photochemical transformations. The high energy content of a light-excited substrate enables the formation of bonds which are not accessible by thermal methods.1,2 Although photoredox catalysis has opened several new avenues for enantioselective synthesis via ground state intermediates,3,4 the control of competing enantiomorphic reaction pathways in the excited state continues to pose a formidable challenge. After seminal contributions to the field in the past decades of the 20th century,5,6 recent efforts toward catalytic enantioselective photochemical reactions in solution7−9 have mainly aimed at the formation of cyclobutanes by [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions.10−16 Our group has exploited chiral Lewis acids in this context,17−19 and we found that reversible coordination to an enone substrate I (Scheme 1) leads to a bathochromic shift of the allowed ππ* transition (absorption coefficient ε > 10 000 M–1 cm–1). Excitation of complex I·L.A.* at a long wavelength generates via a singlet intermediate (S1) the reactive ππ* triplet state (T1). Since intersystem crossing (ISC) from ππ* to ππ* is slow while ISC from nπ* to ππ* is fast,20 the catalyzed reaction is retarded.21 As a result, the uncatalyzed reaction initiated by direct irradiation of Ι via its nπ* state becomes competitive which in turn requires a high Lewis acid loading (50 mol %) to secure high enantioselectivities.

Scheme 1. Photochemical Reactivity Modes of Complexes between a Chiral Lewis Acid (L.A.*) and a Substrate.

When searching for enone reactions which would occur from the S1 state we came across a study by Griffith and Hart that dealt with the photochemical behavior of substituted 2,4-cyclohexadienones 1.22 It had been found that the typical triplet reaction observed for this substrate class was suppressed in polar media and that an oxadi-π-methane rearrangement23,24 occurred. In a later study by Uppili and Ramamurthy,25 the photochemical rearrangement of a single 2,4-cyclohexadienone was performed within a zeolite and an enantiomeric excess (ee) of up to 49% was achieved with (−)-ephedrine as a superstoichiometric (10 equiv) inductor at −55 °C. We hypothesized that complexation of substrates 1 with a chiral Lewis acid would lead to a complex 1·L.A.* which would upon direct excitation generate enantiomerically enriched products 2 via a singlet intermediate. We now report on our studies in this area which have led to the first catalytic enantioselective26 oxadi-π-methane rearrangement.27

Initial experiments were conducted with 2,4-cyclohexadienone 1a, the absorption properties of which were examined in the absence and in the presence of Lewis acids (Figure 1). Successive addition of BF3·OEt2 to a solution of the compound in dichloromethane (c = 2 mM) led to a shift of the ππ* band (λ = 310 nm, ε = 5380 M–1 cm–1). Due to coordination of BF3 to the oxygen lone pair, the nπ* absorption (shoulder at λ = 365 nm, ε = 335 M–1 cm–1) vanished. A new band appeared at λ = 360 nm which was assigned to the ππ* transition of the Lewis acid complex 1a·BF3. Assuming the complex formation to be complete upon addition of 2 equiv of the Lewis acid, the absorption coefficient was calculated as ε = 6920 M–1 cm–1. Isosbestic points at λ = 272 nm and at λ = 330 nm indicate that no other species contribute to the absorption spectra except for 1a and 1a·BF3. Similar spectra were obtained with EtAlCl2 as the Lewis acid (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

UV/vis spectra of 2,4-cyclohexadienone 1a in the absence and in the presence of different equivalents of BF3·OEt2 (c = 2 mM in CH2Cl2, rt).

In general, the absorption difference of complexed vs uncomplexed enones Δλ (in nm) increases if the original ππ* absorption of the chromophore occurs at higher wavelength. For 2,4-cyclohexadienone 1a, the absorption maximum of complex 1a·EtAlCl2 was at λ = 368 nm with Δλ = 58 nm. Compared with other enones, which absorb at a shorter wavelength, the shift was larger.18,19 Together with the expectation of a singlet reaction pathway, an enantioselective transformation even at low Lewis acid catalyst loading seemed therefore feasible.

The fact that the Lewis acid induced shift tailed into the visible region (Figure 1) invited a reaction with visible light. While irradiation of 1a at λ = 420 nm in the absence of a Lewis acid did not lead to a detectable conversion (for details, see Table S1), 10 mol % of BF3 as the Lewis acid induced the expected rearrangement. The product was formed as a 1:1 mixture of the two enantiomers 2a and ent-2a, i.e. as the racemate (Scheme 2). At λ = 420 nm, neither the product nor its BF3 complex shows a detectable absorption and secondary photochemical reactions are avoided (Figure S2).

Scheme 2. Lewis Acid Catalyzed Photochemical Rearrangement 1a → 2a and ent-2a.

Having established a catalytic protocol for the oxadi-π-methane rearrangement of substrate 1a, we started to screen potential chiral Lewis acids. The screening commenced with typical AlBr3-activated oxazaborolidines which we had previously used for enantioselective photochemical reactions.17−19 They are derived from bis(3,5-dimethylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidinyl-methanol and prepared by condensation with a boronic acid.19,28 However, it turned out that the enantioselectivities remained unsatisfactory (<50% ee) which forced us to consider variations of the aryl groups at the methanol carbon atom. Catalyst 3 (Table 1) with sterically bulky 3′,5′-dimethyl-2-biphenyl groups as aryl substituents both at the carbon and at the boron atom evolved from these experiments as the superior Lewis acid that promoted the reaction 1a → 2a at λ = 420 nm (10 mol %, – 75 °C in CH2Cl2) in a yield of 60% with 85% ee. Optimization of the irradiation conditions led to an improved performance if a light emitting diode (LED) with an emission maximum at λ = 437 nm was employed (Figures S4–S8). Product 2a was obtained in 68% yield with 92% ee. The absolute configuration of the product was established by vibrational circular dichroism (VCD),29 comparing experimental and calculated spectra (for details, see Figures S9, S10). The absolute configuration of the other products 2 was assigned based on analogy. The assignment is supported by the identical direction of the specific rotation for all compounds (dextrorotatory) and was later confirmed by a natural product synthesis (vide infra). It was possible to extend the method to a large variety of 3-alkyl substituted 2,4-cyclohexadienones (1b–1o) which had not been previously employed for the reaction (Table 1). The enantioselectivity remained consistently high (>90% ee) with yields varying between 52% and 86%. The reaction is compatible with functional groups as demonstrated for aryl (product 2g), alkenyl (2h), methoxy (2i, 2j), chloro (2k), acyloxy (2l), trifluoromethyl (2m), and protected amino (2n).

Table 1. Enantioselective Photochemical Rearrangement 1 → 2 Mediated by Chiral Lewis Acid 3.

Reactions were carried out on a 150 μmol scale at a concentration of c = 20 mM.

The reaction was carried out on a 750 μmol scale at a concentration of c = 100 mM and at a wavelength of λ = 425 nm for 24 h.

Phth = phthaloyl.

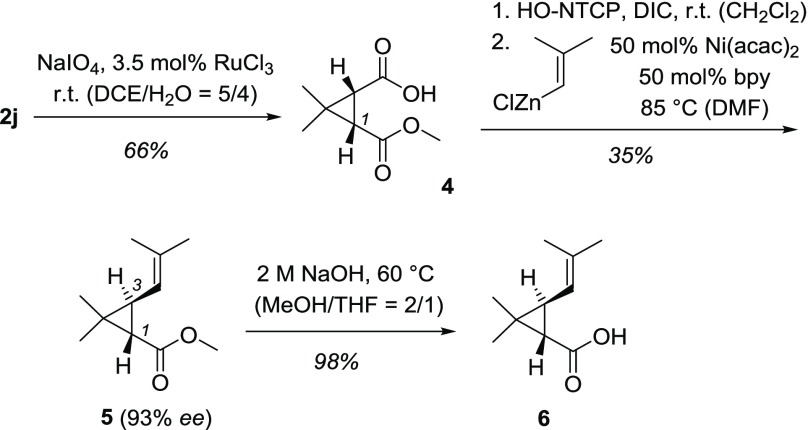

Products 2 display several sites for further functionalization and lend themselves to potential use in synthesis. The gem-dimethyl substituted cyclopropane ring is a notable feature in terpene natural products, and the monoterpene trans-chrysanthemic acid seemed to be a viable target (Scheme 3). Employing an oxidative cleavage protocol,30 we could successfully convert oxadi-π-methane rearrangement product 2j into acid 4 without loss of enantiopurity (93% ee). Since the projected Ni-catalyzed coupling step31 was known to proceed in low yield, we synthesized the starting material 2j on larger scale (100 mg) confirming that the photochemical reactions can be run successfully at a higher concentration (Table 1). After conversion to the N-tetrachlorophthaloyl (NTCP) derivative, the coupling31 was performed without isolation of the intermediate. The reaction produced the trans-compound 5 (d.r. > 95/5) with a consistent enantiopurity of 93% ee. The stereogenic center at C1 is retained in this operation while the stereogenic center at C3 is inverted. Saponification of the ester delivered acid 6 as the levorotatory enantiomer which is known to be (1S,3S)-configured.32 The synthesis consequently supports the previous assignment of the absolute configuration for photoproduct 2j.

Scheme 3. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of trans-Chrysanthemic Acid (6).

Acac = acetylacetone; bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine; DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane, DIC = N,N′-dicarbonyldiimide; DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide; Me = methyl; NTCP = N-tetrachlorophthaloyl; THF = tetrahydrofuran.

The reaction 1a → 2a was performed under otherwise unchanged conditions (Table 1) in the presence of up to 10 equiv of piperylene which is an established triplet quencher.33 There was no decrease in rate or yield for product 2a indicating that triplet intermediates are not involved in the reaction (for details, see Figures S11, S12). The hypothesis that the reaction proceeds via a singlet intermediate was further supported by quantum chemical calculations using density functional theory (DFT) as well as spin-flip linear-response time-dependent DFT (TDDFT)34,35 as implemented into Q-Chem 5.0.36 It was found that the Lewis acid complex 1a·BF3 reaches the first excited singlet state (S1) by an allowed ππ* transition. Remarkably, the preferred conformation of this intermediate is not planar but the gem-dimethylated carbon atom C6 bends out of the plane in which the remaining five carbon atoms reside (Figure 2). The C1–C5 distance has a value of 218 pm at the equilibrium geometry of the S1 state. Proceeding along the relaxation pathway, a sloped conical intersection is energetically accessible only 0.09 eV above the minimum structure, which predominantly leads to relaxation back to the ground state S0. At the optimized geometry of the conical intersection, the critical C1–C5 distance decreases to only 193 pm. Those molecules not returning to the electronic ground state enter the productive exit channel that proceeds via an intermediate zwitterion now with a C1–C5 bond length of 150 pm. Thereby, the conical intersection avoids the population of triplet states and secures a clean product formation with however low quantum yield. The C–C bond formation between carbon atoms C1 and C5 occurs via the trajectory predetermined by the bending of carbon atom C6. The reaction is completed by a typical 1,4-migration of the cyclopropyl group via TS1 to the cationic carbon atom, which proceeds via a small energy barrier of 0.15 eV leaving the complex of product rac-2a·BF3 as the final reaction product.

Figure 2.

Reaction mechanism of the photochemical rearrangement illustrated for substrate 1a.

The calculation also provides a plausible explanation for the observed enantioselectivity. Bending of carbon atom C6 out of the dienone plane in complex 1a·L.A. leads after C–C bond formation to two enantiomeric intermediates 7 and ent-7 which in turn deliver products 2a and ent-2a (Figure 3). Coordination of compound 1a to oxazaborolidine Lewis acids is assumed to occur as previously established for cyclic enones.37−39 In the presence of chiral Lewis acid 3, there is a preference for formation of intermediate 7 because the C6 carbon atom in complex 1a·3 will not move in the direction of the bulky 3′,5′-dimethyl-2-biphenyl substituent at the boron atom but will bend away from it. Product formation via intermediate 7 leads to enantiomer 2a by 1,4-migration. The importance of the hydrogen bond at carbon atom C2 to the oxygen atom of the catalyst was corroborated in the present study by the fact that a 2-methyl-substituted 2,4-cyclohexadienone did not react enantioselectively (Figure S13).

Figure 3.

Migration of carbon atom C5 in Lewis acid complex 1a·L.A. as the enantioselectivity-determining step leading to either enantiomer 7 or ent-7.

In summary, we have discovered an enantioselective photochemical rearrangement reaction that enables the rapid formation of structurally unique, multifunctional products. A remarkable feature of the transformation is the fact that Lewis acid coordination opens a reaction channel that allows the substrate to escape intersystem crossing via a conical intersection. In addition, the Lewis acid governs the absolute configuration of the product within a singlet intermediate. This mode of action promises to be a useful design element for enantioselective photocatalysis.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 665951 – ELICOS) is gratefully acknowledged. C.M. thanks the Fonds der chemischen Industrie for a Liebig fellowship and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for support through the Cluster of Excellence RESOLV (“Ruhr Explores SOLVation”, EXC 2033). We thank O. Ackermann and J. Kudermann for their help with the HPLC and GLC analyses.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.9b12068.

Experimental procedures, analytical data and NMR spectra for all new compounds, GLC and HPLC traces of chiral products, VCD data, Cartesian coordinates, including Figures S1–S13, Table S1 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Photochemistry of Organic Compounds: From Concepts to Practice; Klán P., Wirz J., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, U.K., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kärkäs M. D.; Porco J. A. Jr.; Stephenson C. R. J. Photochemical Approaches to Complex Chemotypes: Applications in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9683–9747. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visible Light Photocatalysis in Organic Chemistry; Stephenson C. R. J., Yoon T. P., MacMillan D. W. C., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silvi M.; Melchiorre P. Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature 2018, 554, 41–49. 10.1038/nature25175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y.; Yokoyama T.; Yamasaki N.; Tai A. An optical yield that increases with temperature in a photochemically induced enantiomeric isomerization. Nature 1989, 341, 225–226. 10.1038/341225a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y. Asymmetric Photochemical Reactions in Solution. Chem. Rev. 1992, 92, 741–770. 10.1021/cr00013a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbrook E. M.; Yoon T. P. Asymmetric Catalysis of Triplet-State Photoreactions. Photochemistry 2018, 46, 432–447. 10.1039/9781788013598-00432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Castro A. F.; Maestro M. C.; Alemán J. Asymmetric induction in photocatalysis – Discovering a new side to light-driven chemistry. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 1286–1294. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.02.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brimioulle R.; Lenhart D.; Maturi M. M.; Bach T. Enantioselective Catalysis of Photochemical Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3872–3890. 10.1002/anie.201411409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C.; Bauer A.; Bach T. Light-driven Enantioselective Organocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6640–6642. 10.1002/anie.200901603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J. N.; Skubi K. L.; Schultz D. M.; Yoon T. P. A Dual-Catalysis Approach to Enantioselective 2 + 2 Photocycloadditions Using Visible Light. Science 2014, 344, 392–396. 10.1126/science.1251511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallavoju N.; Selvakumar S.; Jockusch S.; Sibi M. P.; Sivaguru J. Enantioselective Organo-Photocatalysis Mediated by Atropisomeric Thiourea Derivatives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5604–5608. 10.1002/anie.201310940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum T. R.; Miller Z. D.; Bates D. M.; Guzei I. A.; Yoon T. P. Enantioselective photochemistry through Lewis acid–catalyzed triplet energy transfer. Science 2016, 354, 1391–1395. 10.1126/science.aai8228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tröster A.; Alonso R.; Bauer A.; Bach T. Enantioselective Intermolecular [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition Reactions of 2(1H)-Quinolones Induced by Visible Light Irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7808–7811. 10.1021/jacs.6b03221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Quinn T. R.; Harms K.; Webster R. D.; Zhang L.; Wiest O.; Meggers E. Direct Visible-Light-Excited Asymmetric Lewis Acid Catalysis of Intermolecular [2 + 2] Photocycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9120–9123. 10.1021/jacs.7b04363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Swords W. B.; Jung H.; Skubi K. L.; Kidd J. B.; Meyer G. J.; Baik M.-H.; Yoon T. P. Enantioselective Intermolecular Excited-State Photoreactions Using a Chiral Ir Triplet Sensitizer: Separating Association from Energy Transfer in Asymmetric Photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13625–13634. 10.1021/jacs.9b06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.; Herdtweck E.; Bach T. Enantioselective Lewis Acid Catalysis in Intramolecular [2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition Reactions of Coumarins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7782–7785. 10.1002/anie.201003619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimioulle R.; Bach T. Enantioselective Lewis Acid Catalysis of Intramolecular Enone [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition Reactions. Science 2013, 342, 840–843. 10.1126/science.1244809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplata S.; Bach T. Enantioselective Intermolecular [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition Reaction of Cyclic Enones and its Application in a Synthesis of (−)-Grandisol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3228–3231. 10.1021/jacs.8b01011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed M. A. Triplet state. Its radiative and nonradiative properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 1968, 1, 8–16. 10.1021/ar50001a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brimioulle R.; Bauer A.; Bach T. Enantioselective Lewis Acid Catalysis in Intramolecular [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition Reactions: A Mechanistic Comparison between Representative Coumarin and Enone Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5170–5176. 10.1021/jacs.5b01740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J.; Hart H. A New General Photochemical Reaction of 2,4-Cyclohexadienones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 5296–5298. 10.1021/ja01021a057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banwell M. G.; Bon D. J.-Y. D.. Applications of Di-π-Methane and Related Rearrangement Reactions in Chemical Synthesis. In Molecular Rearrangements in Organic Synthesis; Rojas C. M., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2015; pp 261–288. [Google Scholar]

- Riguet E.; Hoffmann N.. Di-π-methane, Oxa-di-π-methane, and Aza-di-π-methane Photoisomerization. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Knochel P., Molander G. A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2014; Vol. 5, pp 200–221. [Google Scholar]

- Uppili S.; Ramamurthy V. Enhanced Enantio- and Diastereoselectivities via Confinement: Photorearrangement of 2,4-Cyclohexadienones Included in Zeolites. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 87–90. 10.1021/ol010245w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a recent review on catalytic enantioselective rearrangement reactions, see:Wu H.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Recent Advances in Catalytic Enantioselective Rearrangement. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1964–1980. 10.1002/ejoc.201801799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For previous work on an enantioselective oxadi-π-methane rearrangement (up to 10% ee), see:Demuth M.; Raghavan P. R.; Carter C.; Nakano K.; Schaffner K. Photochemical High-yield Preparation of Tricyclo[3.3.0.02,8]octan-3-ones. Potential Synthons for Polycyclopentanoid Terpenes and Prostacyclin Analogs. Helv. Chim. Acta 1980, 63, 2434–2439. 10.1002/hlca.19800630836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J.; Shibata T.; Lee T. W. Asymmetric Diels–Alder Reactions Catalyzed by a Triflic Acid Activated Chiral Oxazaborolidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3808–3809. 10.1021/ja025848x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten C.; Golub T. P.; Kreienborg N. M. Absolute Configurations of Synthetic Molecular Scaffolds from Vibrational CD Spectroscopy. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 8797–8814. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D.; Zhang C. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Oxidative Cleavage of Olefins to Aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 4814–4818. 10.1021/jo010122p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. T.; Merchant R. R.; McClymont K. S.; Knouse K. W.; Qin T.; Malins L. R.; Vokits B.; Shaw S. A.; Bao D.-H.; Wei F.-L.; Zhou T.; Eastgate M. D.; Baran P. S. Decarboxylative alkenylation. Nature 2017, 545, 213–218. 10.1038/nature22307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley M. J.; Crombie L.; Simmonds D. J.; Whiting D. A. Absolute Configuration of the Pyrethrins. Configuration and Structure of (+)-Allethronyl (+)-trans-Chrysanthemate 6-Bromo-2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone by X-ray Methods. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1972, 1276–1277. 10.1039/c39720001276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G. S.; Saltiel J.; Lamola A. A.; Turro N. J.; Bradshaw J. S.; Cowan D. O.; Counsell R. C.; Vogt V.; Dalton C. Mechanisms of Photochemical Reactions in Solution. XXII. Photochemical cis-trans Isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3197–3217. 10.1021/ja01070a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y.; Head-Gordon M.; Krylov A. I. The spin–flip approach within time-dependent density functional theory: Theory and applications to diradicals. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4807–4818. 10.1063/1.1545679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dreuw A.; Head-Gordon M. Single-Reference ab Initio Methods for the Calculation of Excited States of Large Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 4009–4037. 10.1021/cr0505627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y.; Gan Z.; Epifanovsky E.; Gilbert A. T. B.; Wormit M.; Kussmann J.; Lange A. W.; Behn A.; Deng J.; Feng X.; Ghosh D.; Goldey M.; Horn P. R.; Jacobson L. D.; Kaliman I.; Khaliullin R. Z.; Kuś T.; Landau A.; Liu J.; Proynov E. I.; Rhee Y. M.; Richard R. M.; Rohrdanz M. A.; Steele R. P.; Sundstrom E. J.; Woodcock H. L.; Zimmerman P. M.; Zuev D.; Albrecht B.; Alguire E.; Austin B.; Beran G. J. O.; Bernard Y. A.; Berquist E.; Brandhorst K.; Bravaya K. B.; Brown S. T.; Casanova D.; Chang C.-M.; Chen Y.; Chien S. H.; Closser K. D.; Crittenden D. L.; Diedenhofen M.; DiStasio R. A.; Do H.; Dutoi A. D.; Edgar R. G.; Fatehi S.; Fusti-Molnar L.; Ghysels A.; Golubeva-Zadorozhnaya A.; Gomes J.; Hanson-Heine M. W. D.; Harbach P. H. P.; Hauser A. W.; Hohenstein E. G.; Holden Z. C.; Jagau T.-C.; Ji H.; Kaduk B.; Khistyaev K.; Kim J.; Kim J.; King R. A.; Klunzinger P.; Kosenkov D.; Kowalczyk T.; Krauter C. M.; Lao K. U.; Laurent A. D.; Lawler K. V.; Levchenko S. V.; Lin C. Y.; Liu F.; Livshits E.; Lochan R. C.; Luenser A.; Manohar P.; Manzer S. F.; Mao S.-P.; Mardirossian N.; Marenich A. V.; Maurer S. A.; Mayhall N. J.; Neuscamman E.; Oana C. M.; Olivares-Amaya R.; O’Neill D. P.; Parkhill J. A.; Perrine T. M.; Peverati R.; Prociuk A.; Rehn D. R.; Rosta E.; Russ N. J.; Sharada S. M.; Sharma S.; Small D. W.; Sodt A.; Stein T.; Stück D.; Su Y.-C.; Thom A. J. W.; Tsuchimochi T.; Vanovschi V.; Vogt L.; Vydrov O.; Wang T.; Watson M. A.; Wenzel J.; White A.; Williams C. F.; Yang J.; Yeganeh S.; Yost S. R.; You Z.-Q.; Zhang I. Y.; Zhang X.; Zhao Y.; Brooks B. R.; Chan G. K. L.; Chipman D. M.; Cramer C. J.; Goddard W. A.; Gordon M. S.; Hehre W. J.; Klamt A.; Schaefer H. F.; Schmidt M. W.; Sherrill C. D.; Truhlar D. G.; Warshel A.; Xu X.; Aspuru-Guzik A.; Baer R.; Bell A. T.; Besley N. A.; Chai J.-D.; Dreuw A.; Dunietz B. D.; Furlani T. R.; Gwaltney S. R.; Hsu C.-P.; Jung Y.; Kong J.; Lambrecht D. S.; Liang W.; Ochsenfeld C.; Rassolov V. A.; Slipchenko L. V.; Subotnik J. E.; Van Voorhis T.; Herbert J. M.; Krylov A. I.; Gill P. M. W.; Head-Gordon M. Advances in molecular quantum chemistry contained in the Q-Chem 4 program package. Mol. Phys. 2015, 113, 184–215. 10.1080/00268976.2014.952696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paddon-Row M. N.; Anderson C. D.; Houk K. N. Computational Evaluation of Enantioselective Diels–Alder Reactions Mediated by Corey’s Cationic Oxazaborolidine Catalysts. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 861–868. 10.1021/jo802323p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata K.; Fujimoto H. Quantum Chemical Study of Diels–Alder Reactions Catalyzed by Lewis Acid Activated Oxazaborolidines. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 3095–3103. 10.1021/jo400066h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplata S.; Bauer A.; Storch G.; Bach T. Intramolecular [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition of Cyclic Enones: Selectivity Control by Lewis Acids and Mechanistic Implications. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8135–8148. 10.1002/chem.201901304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.