Abstract

Conventions play a fundamental, yet contested, role in social reasoning from childhood to adulthood. Conventions about how to eat, dress, speak, or play are often said to be alterable, contingent on authorities or consensus, specific to contexts, and—thereby—distinct from moral concerns. This view of conventional norms has faced two puzzles. Children and adults judge that (a) some conventions should not be adopted and (b) some violations of conventions would be wrong even if the conventions were removed. The puzzles derive, in part, from the notion of “pure” conventions: conventions detached from non-conventional concerns. This paper proposes and examines a novel solution to the two puzzles, termed the constraint view. According to the constraint view, children and adults deem conventions as alterable within constraints imposed by non-conventional concerns. The present research focused on constraints imposed by concerns with agents to whom the norms apply and concerns with others affected by the norms. Findings from four studies with preschoolers and adults supported the constraint view. Participants evaluated actions and norms based on concerns with effects on agents and others, deeming conventions to be alterable insofar as the altered norms did not negatively impact agents or others. The constraint view offers a new framework for research on how children and adults integrate conventional and non-conventional concerns in evaluation of norms and acts.

Keywords: conventions, social domains, moral cognition, moral development

Social conventions serve to coordinate social interactions, but some conventions do so better than others (Lewis, 1969; Turiel, 1983). It does not matter whether a basketball team wears red or blue jerseys, but cooperation would suffer if both teams wore the same color (Miller & Bersoff, 1988). In a British secondary school, the dress code prohibited boys from wearing shorts even on days that were uncomfortably hot (Morris, 2017; the boys protested the dress code by wearing skirts instead of pants). In other contexts, conventions about attire or forms of address are perceived to discriminate based on race, or in other ways violate the rights or welfare of others (Ehrlich, Meyerhoff, & Holmes, 2014; Higginbotham, 1990).

In research on the development and psychology of morality, conventions are often said to be arbitrary, alterable, contingent on consensus or authorities, and context-specific (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 1983, 2015). By conventions, we mean shared, evaluative expectations for how to act that are alterable in the sense that alternative conventions could coordinate the interactions equally well (Lewis, 1969; Turiel, 1983). Children and adults are often said to distinguish conventions from moral concerns, which individuals treat as unalterable, independent of authorities, and applicable across contexts (Nucci & Gingo, 2011; Smetana, Jambon, & Ball, 2014; Turiel & Dahl, 2019).

The moral-conventional distinction has a contested history (Dahl & Killen, 2018; Gabennesch, 1990; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Kelly, Stich, Haley, Eng, & Fessler, 2007; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Kohlberg, 1971; Nichols, 2002; Royzman, Leeman, & Baron, 2009; Shweder, Mahapatra, & Miller, 1987; Turiel, 2002; Turiel & Dahl, 2019). In particular, prior theorizing about the moral-conventional distinction has faced two empirical puzzles: (a) If conventions are arbitrary and contingent on consensus or authorities, why do people think that some conventions should not be adopted? (b) If conventions are context-specific and contingent on consensus or authority, why do people think that some violations of conventions would be wrong if authorities removed those conventions? These two puzzles have led some scholars to critique, or even reject, the moral-conventional distinction (e.g., Gabennesch, 1990; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Kelly et al., 2007; Machery, 2018; Nichols, 2002; Shweder et al., 1987).

This paper proposes and tests a solution to the two puzzles of conventionality: the constraint view. According to the constraint view, individuals view conventions as alterable within the constraints of non-conventional concerns. Specifically, the present research tests the prediction that children and adults view social norms about dressing, eating, speaking, and playing as alterable insofar as the alterations are not detrimental to agents or others.i From this perspective, there are no “pure” conventions. Although conventional concerns are conceptually distinct from moral and other concerns, no norms pertain exclusively to conventional concerns. The subsequent sections argue that prior research and theory about the moral-conventional distinction lead to the two puzzles of conventionality. We then elaborate on the constraint view, before introducing four studies with preschoolers and adults designed to test key predictions of the constraint view.

The Moral-Conventional Distinction: Developmental and Cultural Variability

People distinguish conventional concerns from moral and other concerns from an early age and across the world (for reviews, see Killen & Smetana, 2015; Smetana et al., 2014). By three years of age, children distinguish violations of norms about speaking, eating, or dressing from violations of norms against hitting or stealing along several dimensions (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana, 1985; Smetana et al., 2012). When asked why it is wrong to wear a bathing suit to school, or violate other norms for dressing, eating, or speaking, children and adults commonly reason about demands of institutions or authorities (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Miller & Bersoff, 1988; Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana, 1985; Turiel, 2008b). Consistent with their justifications, children typically think that the actions would be acceptable if permitted by teachers or another relevant authority (Laupa, 1991; for reviews, see Killen & Smetana, 2015; Smetana et al., 2014; Turiel, 2015).

In contrast, when asked why it is wrong to hit or steal from others, children and adults typically reason in terms of welfare or rights (Dahl, Gingo, Uttich, & Turiel, 2018; Dahl & Turiel, 2019; Nucci & Weber, 1995; Turiel, 2008b). Accordingly, individuals deem that hitting or stealing would be wrong even if teachers or other authorities gave permission. Many religious children and adolescents think that not even gods could make hitting or stealing okay (Nucci & Turiel, 1993; Srinivasan, Kaplan, & Dahl, 2019). Children and adults also distinguish conventional concerns from concerns with agents’ own welfare. When asked why it is wrong to engage in dangerous behaviors, like touching a hot stove, children often reason about agent welfare (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Nucci, Guerra, & Lee, 1991; Tisak, 1993; Tisak & Turiel, 1984).

Reasoning and judgments based on conventional concerns vary across development. From toddlerhood to school age, children become increasingly likely to distinguish norms about dressing and eating from norms about harming or stealing along several dimensions, such as generalization, contingency on authority commands, and assignment of punishment (Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Smetana et al., 2012). With age, children become more likely to make these distinctions for unfamiliar social events (Davidson, Turiel, & Black, 1983). There are also developmental changes in acceptance and rejection of norms based on consensus or authority during later childhood and adolescence, although scholars have disagreed about the nature of these changes (Kohlberg, 1971; Midgette, Noh, Lee, & Nucci, 2016; Turiel, 1983; Yau & Smetana, 2003).

Conventional considerations also vary across cultures in content, perceived alterability, and priority (Haidt, Koller, & Dias, 1993; Midgette et al., 2016; Nucci, Camino, & Sapiro, 1996; Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, & Park, 1997). First, the content of norms for dressing, eating, or communicating vary across communities and contexts. Some schools require school uniforms, others do not (Meadmore & Symes, 1996). The “thumbs up” gesture signals approval in the United States, but contempt in other countries (Archer, 1997; Ekman & Friesen, 1972; Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013). Several studies have found cultural variability in perceived alterability and generalizability of norms about eating or clothing (Nisan, 1987; Nucci, Camino, et al., 1996; Shweder et al., 1987). Lastly, people from different communities differ in when they prioritize compliance to authorities over personal preferences or concerns with others’ welfare and rights (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Nucci, Camino, et al., 1996; Shweder et al., 1997; Turiel & Wainryb, 2000).

Developmental and cultural variability in judgments and reasoning about conventional concerns have generated recurrent debates about the moral-conventional distinction over the past century. (The Supplementary Online Materials [SOM] provide a historical overview.ii) Some have asserted that developmental and cultural variability in reasoning about conventions invalidates the moral-conventional distinction (e.g., Haidt & Graham, 2007; Machery, 2018; Shweder et al., 1987). The next section outlines the current debates, which lead us to two hitherto unresolved puzzles about conventionality.

Current Theoretical Controversies about the Moral-Conventional Distinction

Social Domain Theory: Domain Distinctions and Coordination

Current debates about the moral-conventional distinction center on a framework known as Social Domain Theory. Social Domain Theory proposes that children and adults have evaluative concepts that fall into moral, conventional, and other domains (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Smetana, 2013; Turiel, 2015). Turiel (1983) defined the conventional domain in terms of social organization, tradition, authorities, and consensus; in contrast, he defined the moral domain in terms of others’ welfare, rights, justice, and fairness (Turiel, 1983, pp. 34–35).

Although the proposed moral-conventional distinction was fundamentally a distinction among concepts (e.g., welfare vs. authority commands), social domain researchers have also used the terms “moral” and “conventional” to categorize concrete norms and events. For instance, Weston and Turiel write that children “distinguish between moral norms (e.g., those pertaining to the inflicting of harm on people or stealing) and conventional norms (e.g., those pertaining to forms of address, modes of greeting, or table manners)” (Weston & Turiel, 1980, p. 418; see also Dahl & Kim, 2014; Machery, 2018; Smetana et al., 2014; Turiel, 1983; Turiel, Killen, & Helwig, 1987). Reflecting the same terminology, Turiel and colleagues (1987) refer to the “conventional nature” of “forms of address, customs, table manners” (p. 214). The classification of norms as conventional has been based on whether interviews about those norms tend to elicit conventional responses (Turiel et al., 1987, p. 171). For instance, dress codes were classified as conventional norms because when researchers asked why violating dress codes was wrong, children and adults tended to reference conventional considerations.

Within Social Domain Theory, many norms and events are neither purely moral nor purely conventional. Events that elicited considerations from multiple domains were termed mixed-domain events (Turiel, 1983, 1989; Turiel & Dahl, 2019; Turiel et al., 1987). A central claim of Social Domain Theory is that domain-mixtures prompt individuals to coordinate competing considerations (Dahl et al., 2018; Nucci, Creane, & Powers, 2015; Nucci, Turiel, & Roded, 2017; Turiel, Hildebrandt, & Wainryb, 1991). This balancing can lead individuals to subordinate one domain to another or to strive to coordinate the competing considerations. The focus of research on cross-domain coordination has been on how individuals balanced existing conventions against non-conventional concerns (Nucci & Gingo, 2011; see SOM for further discussion). In contrast, there has been minimal theorizing and research on how individuals evaluate those conventions in the first place. Consequently, as discussed below, theorizing about cross-domain coordination has not explained how individuals judge that some potential conventions about how to dress, eat, or speak are inherently bad and should not be adopted.

Critiques of the Moral-Conventional Distinction

The classification of norms or events as moral or conventional has sparked controversy. Some researchers have found that judgments about harm were influenced by authority commands (Kelly et al., 2007; Rhodes & Chalik, 2013). Other critics have claimed that people sometimes treat seemingly harmless acts of dressing, eating, speaking, or playing as moral violations (Gabennesch, 1990; Haidt et al., 1993; Nichols, 2002; Nisan, 1987; Shweder et al., 1987). Both critiques rely on the assumption that Social Domain Theory classifies all harm events as moral and all dressing, eating, speaking, and playing events as conventional. Furthermore, critics often assume that Social Domain Theory views these two categories of events — moral and conventional — as exhaustive of all social events about which people make judgments of right and wrong (e.g., Machery, 2018).

Social domain scholars have replied that critics have misconstrued both the responses of participants and the claims of Social Domain Theory (Helwig, Tisak, & Turiel, 1990; Turiel et al., 1987; Turiel & Smetana, 1998). For instance, some behaviors presumed to be harmless by researchers were in fact perceived to be harmful by participants (Jacobson, 2012; Turiel et al., 1987). In one paper, Nichols (2002) termed spitting in one’s napkin before dining “harmless,” even though participants actually perceived spitting as having negative effects on other diners (e.g., by disgusting them; see Royzman et al., 2009). Similarly, violations of existing dress codes can offend others through symbolic meanings, which is sometimes called a “second-order” moral event (Helwig & Prencipe, 1999; Turiel, 1983; see also Gray, Young, & Waytz, 2012). A famous example second-order moral event involves a person wearing a bikini to a funeral. Given the clothing conventions in most Western countries, wearing a bikini to a funeral would likely be hurtful to others attending the funeral, even if bikinis were customary at funerals elsewhere (for an extended discussion, see Turiel, 1989).

Social domain researchers have also noted that many critics have studied responses to mixed-domain events, rather than purely moral or conventional events (Helwig et al., 1990; Turiel, 1989; Turiel et al., 1987). As noted, Social Domain Theory classifies situations that elicit reasoning from multiple domains as mixed-domain events, not as purely moral or conventional events. As mixed-domain events do exist, the mere presence of perceived harm does not make an event moral, nor do concerns with authority commands make an event conventional. Mixed-domain situations require coordination between competing concerns with welfare, fairness, and authority commands, sometimes leading individuals to prioritize authority commands over concerns with welfare (Dahl et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2007; Nucci et al., 2017; Turiel & Dahl, 2019; Wainryb, 1991). Hence, Social Domain Theory hypothesizes that judgments and reasoning about mixed-domain events will look very different from judgments and reasoning about purely moral or conventional events (Turiel et al., 1991). For instance, when concerns with welfare are pitted against authority commands, as when soldiers are ordered to kill, judgments and reasoning about harmful actions may incorporate conventional concerns about commands from authorities. These domain-mixtures, however, do not undermine the moral-conventional distinction; in fact, the very notion of domain-mixtures is premised on a distinction between moral and conventional concepts (for further discussion, see Turiel, 1989; Turiel et al., 1987).

Two Persisting Puzzles and the Notion of Pure Conventions

Yet, prior debates about the moral-conventional distinction leave two fundamental puzzles about conventionality unresolved. First, (a) if conventions are arbitrary and contingent on consensus or authorities, why do people sometimes judge that some conventions should not be adopted? In many studies, a notable proportion of individuals disapprove of certain norms for dressing, speaking, eating, or playing (Midgette et al., 2016; Shweder et al., 1987; Turiel & Wainryb, 2000; Weston & Turiel, 1980). For instance, Weston and Turiel (1980) found that over one fourth of children said it would be wrong to have a rule allowing children to take their clothes off at school.

Second, (b) if conventions are context-specific and contingent on consensus or authority, why do people think that some violations of conventions would be wrong even if an authority removed the convention? In some child and adult samples, up to 60% of participants say that violations of norms for dressing, speaking, or eating would be wrong even if there were no rule against these acts (Davidson et al., 1983; Hollos, Leis, & Turiel, 1986; Nisan, 1987; Nucci, Camino, et al., 1996; Shweder et al., 1987; Smetana, 1981, 1985; Smetana & Asquith, 1994; Song, Smetana, & Kim, 1987; Weston & Turiel, 1980). In one study of children from Brazil, about half of lower-class participants said children in a different school or country should wear a uniform even if their school had no such requirement (Nucci, Camino, et al., 1996; see also Haidt et al., 1993; Nisan, 1987; Shweder et al., 1987; Song et al., 1987; Turiel, 1983)

Neither puzzle can be explained by appeals to second-order moral considerations or cross-domain coordination. Both second-order moral considerations and domain coordination presume that a convention already exists: If no convention exists, there would be no violation to cause a second-order moral event nor a conventional norm to be coordinated. Hence, second-order reasoning or coordination cannot explain how individuals reason about whether a new convention should be adopted, or whether an act would be wrong in the absence of a convention.

The two puzzles derive, in part, from the notion of “pure” conventions (see Turiel et al., 1987, p. 167). By pure conventions, we mean conventions that are infinitely alterable (e.g., any dress code would be acceptable) and that it would be permissible to violate if a convention did not exist (e.g., any form of dress should be acceptable unless it were prohibited by a convention). In other words, pure conventions would be norms about which people reason in exclusively conventional terms of authorities or consensus. Past theorizing has not always been explicit on whether there are purely conventional norms or events. Still, scholars have come sufficiently close to implying pure conventions to warrant a discussion. For instance, Turiel (2008b) writes that “there are many situations that are specific to one or the other domain” (p. 137). Similarly, Sutherland and Cimpian (2015) suggest that linguistic norms should be pure conventions: “The words of a language are arbitrary social conventions. […] There is no inherent reason why particular words refer to particular objects” (p. 228).

Purely conventional events are contrasted with events that are specific to other domains and events that pertain to multiple domains. For example, traffic rules have not been considered purely conventional: “A good example of minimal conventionality in a moral and/or prudential situation is uniformity in driving on automobile on a designated side of the road […]. This is different only in a superficial way from the uniformity required by the moral prescription, for instance, that one should not kill innocent children” (Turiel, 1983, p. 115). By implication, prototypical, or pure, conventions would appear to have no direct bearing on the welfare of others.

However, the assumption—explicit or implicit—of pure conventions is difficult to reconcile with data. There is no indication that children or adults view any social norms as infinitely alterable or wholly detached from the welfare of agents or others. As noted by social domain theorists, conventions serve to “coordinate the actions of individuals participating in a social system” (Turiel, 1978, p. 51). Insofar as they serve human purposes, social conventions are cultural tools to achieve human goals (Tomasello, 2016); the achievement of such goals promotes the welfare or rights of at least some people. The norms of wearing team uniforms make basketball easier to play and watch, and adherence to shared group norms promotes group cohesion (Killen, Lee-Kim, McGlothlin, & Stangor, 2002; Killen, Rutland, Abrams, Mulvey, & Hitti, 2013). There is also a second way in which all social norms pertain to rights and welfare:In accepting a social norm for how to dress, speak, eat, or play, individuals relinquish some of their freedom. By accepting the convention of wearing red jerseys, a player loses the option of wearing pink jerseys, even if pink is the player’s favorite color. In this way, accepting any social norm involves a trade-off between any benefits of having the norm and the benefits of being free from that norm. Since any adopted norm, including prototypical conventions, has a bearing on the goals and freedoms of individuals, there are no pure conventions detached from non-conventional concerns with welfare and rights.

In the next section, we propose to abandon the notion of pure conventions in favor of what we will call the constraint view of conventionality. The constraint view offers an explanation for the two puzzles of conventionality. According to this view, the rule about driving on the designated side of the road does not differ fundamentally from so-called prototypical conventions about using knives and forks when eating or wearing a uniform when playing on a sports team. Each is a social norm selected from a constrained set of acceptable norms for solving a problem of social coordination.

The Constraint View of Conventionality

In his classic analysis of conventions, Lewis (1969) proposes that conventions are solutions to social coordination problems. In a coordination problem, “agents have a common interest in all doing the same one of several alternative actions” (Lewis, 1969, p. 24). It does not matter for the basketball team whether the team wears red or white jerseys, but it matters greatly whether all members of the team wear the same color. Conventions provide a way of solving such problems through shared expectations, be it about which jersey color to wear or which title to use when addressing a doctor. By adopting a shared norm, individuals can know which of the possible actions to choose, solving the coordination problem.

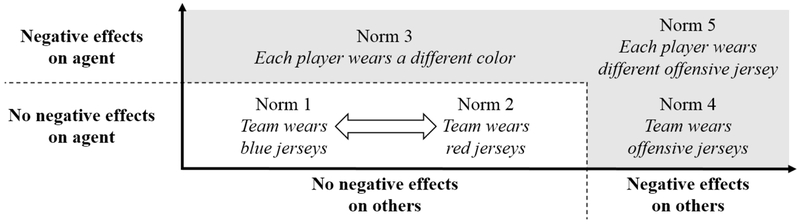

According to the constraint view, the range of acceptable norms for dressing, eating, or speaking is generally constrained by non-conventional considerations. Although multiple norms offer acceptable solutions to some coordination problem (all players wear red jerseys, or wear white jerseys, etc.), other possible norms are deemed unacceptable (e.g., all players wear different colors). The concerns that render some conventions unacceptable are what we call constraints on conventionality. Specifically, this paper is focused on constraints imposed by concerns for agents and others (Figure 1): If the jerseys left agents cold or if the jerseys were offensive to spectators, the constraint view predicts that people would negatively evaluate both the norms and norm-following.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the constraint view. Assume that there are five possible norms (e.g., about basketball team jerseys). Norms 3 and 5 have negative effects on the agent (e.g., does not solve the coordination problem efficiently), Norms 4 and 5 have negative effects on others (e.g., causes psychological harm), and Norms 2 and 3 are equivalent solutions to the coordination problem. The arbitrary choice between Norms 1 and 2 constitutes the conventional element of the decision. The dashed line indicates the constraints on this conventional element. For decisions deemed to be under personal jurisdiction (e.g., which ice cream flavor to pick), the introduction of any norm may be perceived as negatively affecting agents (Nucci, Killen, & Smetana, 1996). For other decisions (e.g., whether to use unprovoked violence against persons), there may be only one permissible norm. The latter norms would have no conventional element.

While the constraint view has not been directly examined in past research, preliminary support can be gleaned from several literatures. Linguistic conventions provide a strong example, since they can seem entirely arbitrary (Sutherland & Cimpian, 2015). Still, there appear to be many constraints on the range of acceptable linguistic conventions (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Grice, 1989; Sutherland & Cimpian, 2015). For instance, it would seem inconvenient for a community of speakers to let the most common words in their language be as long as the longest word in that language (“pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis” in English, Oxford Dictionaries, 2019). Typically, more frequent words are shorter than less frequent words in most languages (Piantadosi, 2014). Linguistic conventions can also have implications for the welfare of others, as when gendered language demeans more than half of the population by implying that some positions are meant for men (e.g., “chairman” instead of “chairperson,” Ehrlich et al., 2014).

Beyond linguistic conventions, the range of acceptable conventions for behavior is also constrained by concerns for agents’ welfare. In their research with children from Brazil, Nucci et al. (1996) reported that half of lower-class children said it would be wrong to eat chicken with your hands, even if there was no norm against doing so. When asked why eating with your hands would be wrong, children frequently expressed health concerns. (Nucci and colleagues noted that participants came from a region in the midst of a cholera epidemic.) While many children and adults accept alternative customs for how to eat, they also disapprove of intentionally spilling food, in part because of concerns with agents’ welfare (Dahl, 2016; Dahl & Kim, 2014).

In other cases, possible conventions are perceived to affect persons other than the agents following the norms. Before the 1960s, judges in the United States could address African American women by their first name even though the judges addressed White women by their title and last name. Then, in 1963, an African American woman named Mary Hamilton refused to answer a judge unless the judge addressed her by “Miss Hamilton” instead of “Mary” (Domonoske, 2017). As the judge continued addressing her as “Mary,” Hamilton was jailed for refusing to answer the judge. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately sided with Hamilton, deciding that courts could not address African American and White witnesses differently (Domonoske, 2017; Higginbotham, 1990).

These reports exemplify how children and adults evaluate possible conventions, and acts regulated by conventions, based on concerns with agents and others. The constraint view offers a systematic account of such findings and generates new predictions. The norms regulating eating, dressing, speaking, or playing have a conventional element insofar as there are two or more possible norms that offer acceptable solutions to a coordination problem (Lewis, 1969). The choice between these (near-)equivalent norms is arbitrary and often determined by authorities, consensus, or traditions. Yet, the constraint view also asserts that there are no pure conventions devoid of constraints. For any coordination problem, individuals will perceive certain possible norms to negatively impact agents or others, and accordingly view those norms as wrong.

The constraint view maintains the conceptual distinction between conventional considerations (about authorities, consensus, and tradition) and moral considerations (about welfare, rights, fairness, and justice) (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 1983, 2015). Conventional and moral considerations remain conceptually distinct even when they are applied to the same event (Dahl & Waltzer, 2018; Turiel, 1989; Turiel & Dahl, 2019). As discussed above, when conventional considerations (e.g., authority commands) and moral concerns (e.g., welfare) conflict, individuals strive to coordinate these competing considerations (e.g., Nucci et al., 2015). By analogy, bird counting employs both biological knowledge (what is a bird?) and mathematical knowledge (how to count?), but concepts of birds and numbers are nevertheless distinct (Gelman, 2010).

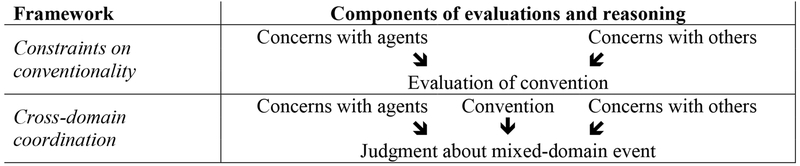

The constraint view accounts for findings not accounted for by prior theorizing about cross-domain coordination. To see the contrast between the constraint view and cross-domain coordination, consider the philosophical distinction between evaluating a norm and evaluating a practice regulated by that norm (Rawls, 1955). Some have criticized the basketball rule that awards three points to shots made from a greater distance, arguing that the rule makes basketball boring for spectators (Zucker, 2018). Still, those same individuals appeal to the 3-point rule to insist that their team be awarded three points for long-distance shots. As stated by Rawls: “…reasons might properly be given in arguing that the game of chess, or baseball, […] should be changed in various respects, but a player in a game cannot properly appeal to such considerations as reasons for his making one move rather than another” (Rawls, 1955, p. 16). The constraint view offers a framework for explaining why individuals evaluate potential conventions for eating, dressing, playing, or speaking. In contrast, theories about cross-domain coordination explain how participants balance adopted conventions against moral and other non-conventional concerns (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The figure represents the relation between the constraint view and cross-domain coordination. Theorizing about cross-domain coordination (bottom) aims to explain how an individual balances existing conventional norms against non-conventional considerations, e.g., about agents and others. In contrast, the constraint view (top) offers an explanation of how an individual forms evaluations regarding the (possible or actual) conventions by themselves.

Overview of the Present Research

Four studies tested key hypotheses of the constraint view. The studies were designed around activities commonly said to be regulated by conventions, such as speaking, dressing, eating, and playing (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Machery, 2018; Smetana et al., 2014; Turiel, 1983; Turiel et al., 1987; Weston & Turiel, 1980). For each of these areas, the constraint view predicts that individuals would typically accept alternative norms (conventional element) insofar as the new norm did not adversely affect agents or others (non-conventional element). While this paper focused on constraints imposed by concerns for agents and others, the constraint view also asserts that other (e.g., religious) concerns may also constrain the range of acceptable conventions (see General Discussion). The descriptions of the four studies avoid referring to the stimulus norms and events as “conventional,” as it was an empirical matter whether participants would deem various rules to be acceptable solutions to some coordination problem (see General Discussion). Across the four studies, a wide variety of events were included to test the generality of the constraints imposed by concerns with agents and others.

Although we hypothesized that the findings would support the constraint view, the findings could also invalidate the constraint view in two ways. It could turn out that individuals would not view the social norms as alterable (challenging the moral-conventional distinction), even if the norm alterations did not adversely affect agents or others. It could also turn out that individuals would view the social norms as infinitely alterable (evidencing pure conventions), such that individuals would accept any norm for a given activity irrespective of how the norm affected agents and others.

Study 1 investigated adult evaluations of everyday practices commonly thought to be regulated by social conventions, such as eating, dressing, and speaking. The first hypothesis was that participants’ evaluations of everyday acts of eating, dressing, and speaking would often reflect concerns with agents and others (H1.1, Table 1). The second hypothesis was that these concerns would constrain evaluations, such that acts that elicited more concerns with agents or others would more often be viewed as wrong in the absence of a shared norm (H1.2). To develop ecologically valid situations and evaluation questions for Study 1, a preparatory investigation elicited adults’ own descriptions and evaluations of events in their everyday lives. Study 2 examined the constraints on alterability of conventions by interviewing adults about rules prescribing acts that varied in their impact on agents and others (H2.1 - H2.3). Study 3 sought to corroborate the Study 2 findings with a separate sample of adults using stimuli adapted for children (H3.1 - H3.3). Using the stimuli from Study 3, Study 4 investigated whether children impose constraints on the alterability of such rules by three to five years of age (H3.1 - H3.3). By this age, most children distinguish conventional considerations from moral and other evaluative considerations (Smetana et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Overview of Hypotheses

| Sample | Agents | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||

| Adults | Adults | H1.1: Evaluations of eating/dressing/speaking reflect concerns with agents and others |

| H1.2: Concerns with agents and others constrain alterability of those evaluations | ||

| Study 2 | ||

| Adults | Adults | H2.1: Most accept alternative rules that do not negatively impact agents and others |

| H2.2: Most reject alternative rules that negatively impact agents and others | ||

| H2.3: Justifications for why a rule was not okay reference effects on agents or others | ||

| Study 3 | ||

| Adults | Children | H3.1: Most accept alternative rules that do not negatively impact agents and others |

| H3.2: Most reject alternative rules that negatively impact agents and others | ||

| H3.3: Justifications for why a rule was not okay reference effects on agents or others | ||

| Study 4 | ||

| Adults | Children | H4.1: Most accept alternative rules that do not negatively impact agents and others |

| H4.2: Most reject alternative rules that negatively impact agents and others | ||

| H4.3: Justifications for why a rule was not okay reference effects on agents or others |

Note. The table shows the hypotheses for each study. The leftmost column shows the participants used for each study and the next column shows the agents depicted in the situations presented to participants.

Study 1

Method

Participants.

Forty-eight undergraduate students were recruited from a participation pool at a public research university in the Western United States. Participants received course credit.

Materials.

To develop ecologically valid stimuli for Study 1, a preparatory study was conducted. Undergraduate participants (N = 50) were asked to describe nine situations from their everyday lives involving eating, dressing, and addressing others in which they thought someone had done something they should not have done. The students were also asked to provide one word or phrase that captured their opinion about the act. After reviewing the events obtained in the preparatory study, we selected six situations involving eating (being loud in a restaurant, chewing with mouth open), dressing (wearing sweats when working at a hotel front desk, being barefoot at school), and addressing others (laughing at another student, writing email to faculty member without greeting or signature). These situations were chosen because they were representative of the elicited events and because they were comprehensible without extensive background information.

Participants in the preparatory study generated a total of 755 act descriptions. After pooling synonyms (e.g., “rude” and “disrespectful”), the 10 most common descriptors were: disrespectful, inconsiderate, gross, weird, offensive, hurtful, mean, childish, wasteful, and dangerous. These adjectives were used to create a questionnaire for Study 1, in which participants indicated whether they thought the adjective described the protagonist’s action on a scale from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5). The SOM provide complete descriptions of the scenarios for Studies 1-4 and the adjective checklist for Study 1.

Procedures.

Participants in Study 1 were interviewed individually in a separate room. All participants responded to all six stories, presented in counterbalanced order. After reading each story to the participant, the interviewer asked the participant to complete the adjective questionnaire on a paper form. The questionnaire also asked participants to “choose one word or phrase to capture your opinion about the person’s action” and to rate the person’s action on a scale from −5 (extremely bad) to +5 (extremely good) (action ratings). If the participant indicated a negative evaluation of the action, the interviewer posed two questions to which the participant responded verbally. First, the interviewer asked, “Do you think it was okay for [agent] to [do the act]?” Second, to assess whether participants viewed the underlying norm as changeable, the interviewer asked participants, “What if most people [did the act] and saw nothing wrong with it? Would it still be [participants’ evaluative term] to [do the act] then?”

Coding and data analysis.

Research assistants entered participants’ questionnaire and interview responses into a spreadsheet. Coders blind to the research hypotheses coded participants’ own evaluative terms for whether it indicated a negative evaluation of the agent’s action. Interrater agreement, assessed on 20% of responses, was: Cohen’s κ = .85. Data were analyzed using Principal Component Analysis and Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs, Hox, 2010). All GLMMs included random effects of participants and fixed effects of scenario type. Models analyzing dichotomous data used binomial error distributions and logistic link functions; remaining models used Gaussian error distributions and identify link functions. Hypotheses were tested using likelihood ratio tests for change in model deviance (D) and Wald tests for individual regression coefficients. The raw data for all four studies are available at https://osf.io/nxy5j/?view_only=f3f169328ff946f1907155fbbf7d7c48.

Results

Dimensions of evaluations.

The Principal Component (PC) Analysis on questionnaire responses supported the hypothesis about two evaluative dimensions (impact on agents and impact on others). Variables were standardized before the analysis. The first two PCs accounted for 39% of the variance (PC1: 23%, PC2: 16%). Six items loaded most strongly onto the first component: childish, disrespectful, hurtful, inconsiderate, mean, and offensive (loadings: .38-.44). This dimension appeared to represent perceptions of how the actions affected others. Four items loaded most strongly onto the second component: dangerous, gross, wasteful, and weird (loadings: .43-,50) (In the preparatory story, verbal explanations indicated that participants used “weird” in the sense of “irrational” or contrary to the agent’s interests; Dahl & Schmidt, 2018). This second dimension appeared to represent perceptions of how the actions affected the agent.

To create composite scores for these two dimensions, separate PC analyses were conducted for the six items loading most strongly onto PCI and the four items loading most strongly onto PC2. The first PC of each of these analyses was used as a composite score (composite others, 39% of variance; composite agent, 36% of variance). The two composite scores were slightly positively correlated, LMM: D(1) = 44.74, p < .001, Pearson’s r = .14. Both composite scores were negatively related to action ratings; composite others: D(1) = 48,38, p < .001, r = −.59, composite agent. D(1) = 13.99, p < .001, r = −.21, when entered separately. (When both composites were entered simultaneously as predictors of action ratings, composite others remained significant, D(1) = 36,48, p < .001, whereas composite agent was no longer significant, D(1) = 1.89, p = .17.)

Alterability of evaluations.

Most participants initially described the action negatively (93%). When participants described the act negatively, they also tended to say the act was “not okay” (66%). However, participants also indicated that their negative evaluations were contingent on existing social arrangements. When asked whether they would still view the act negatively if most people approved of the practice, participants maintained their negative evaluations in 52% of cases.

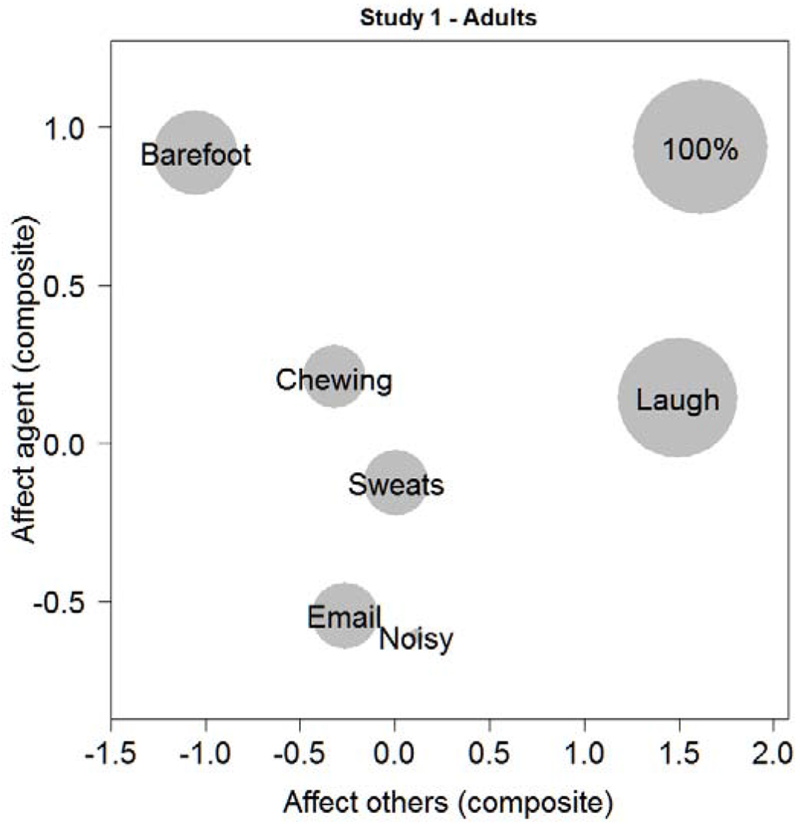

The propensity to view the act negatively if the act was a common practice varied greatly by situation (range: 10% - 89%), binomial GLMM: D(5) = 65.02, p < .001. As shown by Figure 3, this variability was associated with the average ratings for each situation on the affect others and affect agent components. Models were fitted predicting whether participants would still view the act negatively if it were common practice from the average situational ratings on the two components. These analyses revealed a significant effect of both the affect others component, D(1) = 22.52, p < .001, and the affect agent component, D(1) = 27.78, p < .001: The higher the average score on the affect others or affect agent components, the more likely participants were to say that the act would still be wrong even if it were common practice.

Figure 3.

Alterability of evaluations. The radius of each circle is proportional to the percentage of participants who said they would still negatively evaluate the act even if most people saw nothing wrong with the act. For comparison, the circle in the upper right corner indicates 100%.

Discussion

Study 1 used situations derived from college students’ own experiences involving eating, dressing, and speaking. These contexts were chosen because they are often said to be regulated by social conventions. As hypothesized, participants’ evaluations reflected concerns with how the actions affected agents and others (H1.1, Table 1). Moreover, participants’ judgments were often contingent on existing practice. While participants nearly always provided a negative evaluation of the act at first, they maintained those negative evaluations only about half of the time when imagining that the act was common practice. Actions varied considerably in how likely participants were to judge them as acceptable if they were common practice. Actions that elicited more evaluations reflecting concerns with agents or others were more likely to be viewed negatively even if everyone else had accepted the action (H1.2). This provided initial evidence that perceptions of consequences for agents and others constrain the alterability of rules in areas often considered regulated by conventions.

To further examine constraints on alterability of social rules with conventional elements, Study 2 manipulated whether altered rules negatively affected agents (affect agents variants) or others (<affect others variants). Study 2 also included an alteration of a rule that was not expected to negatively affect agents or others (alternative variants). The overall hypotheses were that most participants would accept alternative rules that did not negatively impact agents and others (H2.1), but reject alternative rules that would negatively impact agents (affect agents) or others (affect others) (H2.2). Although Study 1 indicated that participants made evaluations beyond determinations of okay and not okay (e.g., inconsiderate, rude), Studies 2–4 relied on judgments of okay and not okay in order to make findings comparable to past research on children’s and adults’ judgments about conventions. It was also hypothesized that participants’ justifications for why a rule was not okay would typically reference agents in the affect agent scenarios and other people in the affect others scenarios (H2.3).

Study 2

Method

Participants.

Sixty-six undergraduate students (Mage = 19.6 years, 82% female, 17% male, 2% other) were recruited from a research participation pool at a public research university in the Western United States. Participants received course credit for their participation.

Materials.

Four initial situations were created involving violations of a social rule that did not have intrinsic negative consequences for the welfare of agents or others (default situation): wearing a jersey when playing basketball, saying please when asking for something, obeying a sign not to walk in a given area, and adhering to a teacher request to remain seated. For each of these situations, three variants were created. One variant, termed alternative, was created so as to be functionally similar to the initial variant and not impose additional negative consequences on agents or others (e.g., the team wears a blue jersey instead of a red jersey). One variant, termed affect agents, differed from the default and alternative variants by imposing negative consequences on agents (e.g., the team wears the same colored jersey as the competing team). The fourth variant, termed affect others, imposed negative consequences on others (e.g., the team wears jerseys with racist symbols).

Procedures.

Participants were interviewed individually in a separate room. The interviewer read the scenarios and questions, and participants responded verbally. All participants were presented with all three variants of all four situations. Interviews were video recorded for coding purposes. The order of situations and the order of variants within each situation were counterbalanced. For each situation, participants were first told about a protagonist in a context where the original rule applied (e.g., “Mary plays on a basketball team. Mary learns that all her teammates think they should wear red jerseys”). Then, participants were asked to imagine each of the three variants. The three variants were introduced by the statement “Imagine that Mary is in a different society and learns that her team thinks they should, followed by a statement about the variant rule (e.g., alternative: “wear blue jerseys”, affect agent: “wear the same jersey as the other team,” affect others: “wear jerseys with white supremacist symbols”). After each variant, the interviewer asked participants whether it was okay to follow the rule (e.g., “is it okay for Mary to wear [jersey prescribed by rule]”?), whether having the rule was okay (e.g., “is it okay to have a rule that the team should wear [jersey prescribed by rule]?”), and how good or bad the rule was on a scale from −5 (“Extremely bad rule”) to +5 (“Extremely good rule”). When participants said having the rule was not okay, they were asked for justifications (e.g., “Why is it not okay to have the rule that the team should wear [jersey prescribed by rule]?”).

Coding and data analysis.

Coders blind to the research hypotheses classified participant responses by reviewing the video recordings. When participants said that the rule was not okay, research assistants coded whether participants referenced effects on agents or effects on others. Interrater agreement, based on 15% of the data, was: Cohen’s κ = .82. Data were analyzed using GLMMs. Hypotheses were tested using likelihood ratio tests and Wald tests.

Results.

Was it okay to have the rule?

Judgments about whether the rule was okay varied significantly across variants, D(2) = 297.06, p < .001. In most cases, most participants thought the alternative variants were okay (65% of cases), while they rarely thought the affect agents variants (28%) or the affect others variants were okay (2%), all Wald tests: χ2(1) > 44,34, p < .001. The effect of variants on judgments about the rule was significant for each of the four situations when analyzed separately, Ds(2) > 25.27,ps < .001.

Why was it not okay to have the rule?

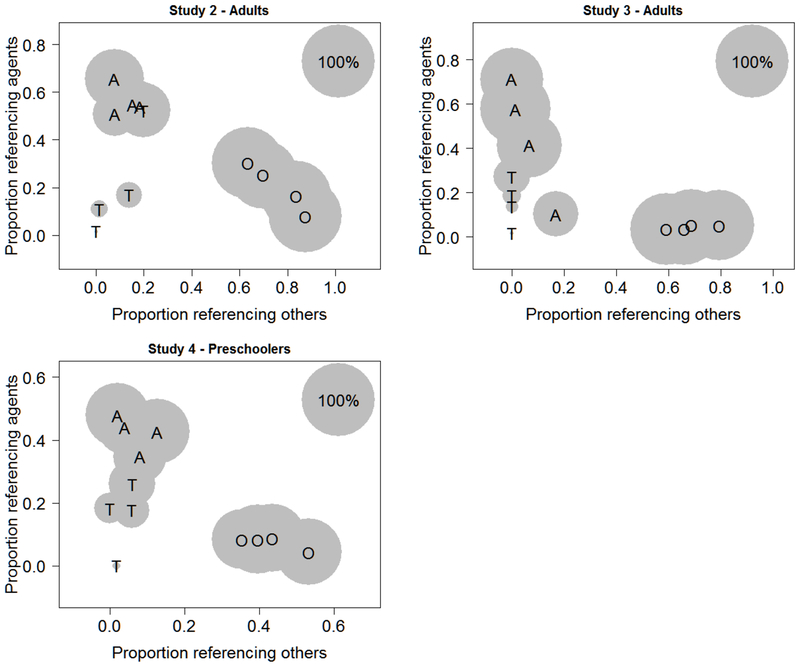

Participants’ references to effects on agents varied significantly by scenario variant, D(2) = 67.73, p < .001 (Figure 4). Among participants who said the rule was not okay, references to effects on agents were more common in the affect agents variants (79%) than in the alternative variants (60%), which in turn differed from the affect others variants (20%), Wald tests: χ2(1) > 10.76, p < .001. There was also a significant effect of variant on references to effects on others, D(2) = 191.57, p < .001. References to effects on others were more common in the affect others variants (79%) than in the alternative (26%) and affect agents (18%) variants, Wald tests: χ2(1) > 59.75, p< .001. In contrast, the probability of referencing effects on others did not differ significantly between the alternative and affect agents variants, Wald test: χ2(1) = 1.51, p =.22.

Figure 4.

Acceptability of rules (Studies 2–4). The radius of each circle is proportional to the percentage of participants who said the rule was not okay (T = alternative variants, A = affect agents variants, O = affect others variants). The location of the center of the circle represents the proportion of participants who referenced effects on agents (y-axis) and effects on others (x-axis) when explaining why the rule was not okay.

How good/bad was the rule?

Participants’ ratings of rules also differed significantly by variant, D(2) = 469,37, p < .001. Participants rated the alternative variants more positively (M = 0.26) than the affect agents variants (M = −2.16), which in turn were evaluated more positively than the affect others variants (M= −4.41), Wald tests: χ2(1) > 154.38, p < .001.

Was it okay to follow the rule?

Judgments about conformity differed by variant, D(2) = 378.131, p< .001. Participants were more likely to judge rule-following as okay in the alternative variants (80%) and affect agent variants (79%) than in the affect others variants (14%), Wald tests: χ2(1) > 160.84, p < .001.

Discussion

Study 2 supported the hypothesis that concerns with agents and others constrain the range of acceptable social rules. While most participants found a functionally similar alternative rule acceptable, participants negatively evaluated rules they perceived as detrimental to agents or other people. Participants viewed rules detrimental to other people especially negatively, as evidenced by severity judgments and their frequent judgments that it was not acceptable to follow these rules. Participant justifications supported the study hypotheses: When explaining why the affect agents rules were not okay, participants typically referenced how following the rules could affect the interests or welfare of agents following the rule (e.g., “It’s unnecessary,” “They could hurt themselves”). These justifications were also common when explaining why the alternative rules were not okay (although most participants said the alternative rules were okay, a minority said they were not okay). In contrast, when explaining why the affect agents rules were not okay, participants typically referenced how following the rules would negatively impact others (e.g., “They are bothering others,” “You shouldn’t harm other people”).

Study 3 had two goals. First, it sought to corroborate the findings from Study 2 with new situations. Second, it sought to develop and validate stimuli that were appropriate for preschool-age children, to be used in Study 4. The moral-conventional distinction has been particularly central in the developmental literature (see e.g., Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 2015). Hence, it was important to examine whether concerns with agents and others also constrained evaluations of conventions at three to five years of age, by which age most children distinguish conventional and moral concepts. It was hypothesized that most participants in Study 3 would accept alternative rule variants (H3.1), reject affect agents and affect others variants (H3.2), and reference agents (in affect agent variants) and others (in affect others variants) when explaining why the rule was not okay (H3.3).

Study 3

Method

Participants.

Sixty undergraduate students (Mage = 20.0 years, 77% female, 22% male, 2% other) were recruited from a research participation pool at a public research university in the Western United States. Participants received course credit for their participation. Two additional participants were interviewed, but their data were removed because of a recording failure or because the person was not fluent in English.

Materials.

Four situations were created that involved rules for children in a preschool: Not wearing a bathing suit, not playing with toys during lunch time, not playing with new toys, and not talking during lunch. The rules were said to be endorsed by the teachers at the preschool. For each scenario, three variants were created: an alternative variant that was functionally similar and did not add negative consequences on agents or others (e.g., that children should wear a bathing suit to school), an affect agents variant in which rule following would negatively impact agents (e.g., that children should wear a bathing suit to school when it is really cold), and an affect others variant in which rule following would negatively impact others (e.g., that children should take clothes from other kids).

Procedures.

Procedures were largely the same as in Study 2. Participants were interviewed individually in a separate room. The interviewer read the scenarios and questions, and participants responded verbally. Interviews were video recorded for coding purposes. The order of presentation for situations and variants was counterbalanced. After presenting each variant, the interviewer asked participants whether it was okay to follow the rule, and whether it was okay for the teachers to require adherence to the rule. If participants said it was not okay for the teachers to require adherence, the interviewer asked why it was not okay for teachers to require adherence. The interview also included a simplified rating scale for how good or bad the rule was, adapted for preschool participants. If participants said it was okay for the teachers to require adherence to the rule, the interviewer asked if it was “pretty good” or “really, really good” that the teachers required adherence. If participants said it was not okay for the teachers to require adherence, the interviewer asked if the teachers’ request was “pretty bad” or “really, really bad.”

Coding and data analysis.

Coders blind to the research hypotheses classified participant responses by reviewing the video recordings. When participants said that the rule was not okay, research assistants coded whether participants referenced effects on agents or effects on others. Interrater agreement, calculated on 20% of the data, was: Cohen’s κ = .81. Ratings were converted to a numeric scale from −2 (“really, really bad”) to +2 (“really, really good”). The distribution of the rating data deviated substantially from a normal distribution. Hence, averages for each participant for each scenario (<alternative, affect agents, affect others) were analyzed using Friedman tests. The remaining data were analyzed using GLMMs, and hypotheses were tested using likelihood ratio tests and Wald tests.

Results

Was it okay to have the rule?

Judgments about whether the rule was okay varied significantly between variants, D(2) = 389.23, p < .001. Participants were more likely to say the rule was okay for the alternative variants (75%) than for the affect agents (15%) and affect others (2%) variants, all Wald tests: χ2(1) = 22.76, p < .001. The effect of variants on judgments about the rule was significant for each of the four situations when analyzed separately, Ds(2) > 43.06, ps < .001.

Why was it not okay to have the rule?

When explaining why the rule was not okay, participants’ references to effects on agents varied significantly by scenario variant, D(2) = 168.55, p < .001 (Figure 4). Such references were more common in response to the alternative variants (62%) than in response to the affect agents variants (53%), both of which differed from the affect others variants (4%), all Wald tests: χ2(1) > 6.69, p < .001. References to effects on others also varied significantly by scenario type, D(2) = 247.02, p < .001, being more common in the affect others variants (68%) than in the affect agents (6%) and alternative (0%) variants, Wald tests: χ2(1) > 97.81, p < .001. The latter two variants did not differ significantly, χ2(1) = 0.02, p = .89.

How good/bad was the rule?

Ratings of rules varied significantly by scenario variant, Friedman rank sum test: χ2(2) = 105.72, p < .001. Paired Wilcoxon tests revealed that average ratings of the alternative rule (M = 0.71) were significantly higher than average ratings of the affect agent rule (M = −1.28), which was significantly higher than the affect others rule (M = −1.85), Wilcoxon tests: Vs > 990, ps < .001.

Was it okay to follow the rule?

Propensity to say it was okay to follow the rule varied significantly between scenario variants, D(2) = 534.53, p < .001. Participants were far more likely to say it was okay to follow the rule in the alternative scenarios (97%) than in the affect agents (58%) and affect others (9%) scenarios, all Wald tests: χ2(1) > 67.52, p < .001.

Discussion

The findings from Study 3 were consistent with the findings from Study 2: Participants’ concerns with agents and others constrained what they considered acceptable rule changes. Most participants accepted an alternative rule that did not impose negative consequences on agents and others, but few accepted rules that negatively impacted agents or others. Concerns with such consequences were also evident in their justifications for why a given rule was not acceptable, as well as their evaluations of adherence to the rules.

Study 4 examined children’s evaluations of rules at three to five years of age, by which age children distinguish conventional considerations from moral and prudential considerations (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Smetana et al., 2014, 2012). As for Studies 2 and 3, it was hypothesized that most children in Study 4 would accept alternative rule variants (H4.1), reject affect agents and affect others variants (H4.2), and reference agents (in affect agent variants) and others (in affect others variants) when explaining why the rule was not okay (H4.3).

Study 4

Method

Participants.

Fifty-six children (Mage = 4.3 years, range: 3.0 - 5.6 years, 55% female,45% male) were recruited from preschools in the areas surrounding the university from which adult samples were recruited. Three additional children were interviewed, but their data were removed due to parent or teacher interference.

Materials, procedures, coding, and data analysis.

The scenarios and questions were identical to those used in Study 3. Participants were interviewed one at a time in a separate location in the child’s preschool. The interviewer read the scenarios and questions, and children provided verbal responses. The interviewer recorded children’s responses to the judgment and rating questions by hand. In addition, interviews were video recorded for the purposes of coding justifications. Video data for seven children were not available, and hence no justification data could be coded for these children. To facilitate comprehension, each scenario was accompanied by illustrations displayed in a laptop computer. Procedures, coding, and data analyses were as in Study 3, except that child age was added as a fixed predictor in the GLMMs. Interrater agreement, assessed on 20% of the data, was Cohen’s κ = .90.

Results

Was it okay to have the rule?

Children’s judgments about whether the rule was okay varied significantly between variants, D(2) = 162,48, p < .001 (Figure 4). Children were more likely to say the rule was okay for the alternative variants (58%) than for the affect agent (19%) and affect others (10%) variants, all Wald tests: χ2(1) > 8.17, p< .005. There was no significant effect of child age, D(1) = 2.39, p = .12. The effect of variants on judgments about the rule was significant for each of the four situations when analyzed separately, Ds(2) > 9,92, ps < .004.

Why was it not okay to have the rule?

When explaining why the rule was not okay, participants’ references to effects on agents varied significantly by scenario variant, D(2) = 101.38, p < .001. There was no significant difference in such references between affect agents (54%) and alternative variants (39%), χ2(1) = 3,39, p = .066. Both these conditions elicited more frequent references to effects on agents than the affect others variants (8%), Wald tests: χ2(1) > 34.45, p < .001. In addition, older children were more likely than younger children to reference effects on agents, D(1) = 5.23, p = .022. References to effects on others also varied by scenario variant, D(2) = 98.47, p < .001, being more common in the affect others variants (49%) than in the affect agents (9%) and alternative (9%) variants, χ2(1) > 30.54 p < .001. The latter two variants did not differ significantly, χ2(1) = 0.23, p = .63. In addition, older children were more likely than younger children to reference effects on others D(1) = 6.05, p = .014.

How good/bad was the rule?

Ratings of rules varied significantly by scenario variant, Friedman rank sum test: χ2(2) = 67.12, p < .001. Paired Wilcoxon tests revealed that average ratings of the alternative rule (M = 0.28) were significantly higher than average ratings of the affect agent rule (M = −1.03), which was significantly higher than the affect others rule (M = −1.44), Wilcoxon tests: Vs > 528, ps < .008. Average rule ratings were not significantly correlated with child age, Spearman’s r = −.17, S = 34253, p = 0.21.

Was it okay to follow the rule?

Propensity to say it was okay to follow the rule varied significantly between scenario variants, D(2) = 189.20, p < .001. Participants were more likely to say it was okay to follow the rule in the alternative variants (62%) than in the affect agent (19%) and affect others (8%) variants, all Wald tests: χ2(1) > 12.15, p < .001. The effect of age was not significant, D(1) = 1.01, p = .32.

Discussion

Study 4 provided evidence that preschoolers viewed social rules about dressing, speaking, eating, and playing as alterable within constraints imposed by concerns for agents and others. Preschoolers’ responses were largely similar to adult responses in Study 3. Children were far more accepting of the alternative rule variants than the affect agents and affect others rule variants, and explained their negative evaluations of rule variants by referencing consequences to agents (<alternative, affect agents variants) and others (affect others variant). Such references were more common among older than among younger children. Also like adults, preschoolers were far more likely to say it would be okay to follow the rules in the alternative variants than in the affect agents and affect others variants.

General Discussion

The present research addressed two puzzles of conventionality. If children and adults view conventions as arbitrary, alterable, and contingent on authorities or consensus, why do they judge that (a) some conventions should not be adopted and (b) some violations of conventions would be wrong even if the convention was removed? The constraint view proposes that evaluations and reasoning about social norms are generally constrained. It was hypothesized that, even for “conventional” issues such as eating, playing, dressing, or speaking, participants would typically reject norms and acts perceived to negatively affect agents or others.

The four studies yielded findings consistent with the constraint view. In evaluating social norms and acts regulated by those norms, children and adults employed concerns for agents to whom the rules applied and for other affected persons. They largely found alternative and functionally similar social norms acceptable. In contrast, when a proposed norm threatened the interests of agents or others, participants gave more negative evaluations of the rules and of adherence to those rules. Participant justifications further revealed that children and adults applied concerns with agents and others when evaluating the different scenarios.

The findings from one of the scenarios in Study 2 provide a clear illustration of this pattern of judgments and reasoning. When asked about different rules for the jerseys of a basketball team, nearly all participants found it acceptable for the team to wear either red or blue jerseys. However, most participants rejected the rule that the team should wear the same colored jersey as the other team, which would hinder cooperation among team members. Furthermore, nearly all participants rejected the rule that the team should wear jerseys with offensive symbols. In short, the choice of conventions for team jerseys was arbitrary within constraints imposed by concerns for the team players as well as other people possibly affected (e.g., offended by the jerseys).

Corroborating this pattern, Study 1 took a bottom-up approach to evaluations about acts of dressing, eating, and addressing others. These activities are often said to be regulated by social conventions. Using situations and evaluative adjectives derived from adults’ own narratives, Study 1 revealed that concerns with agents and moral concerns with others constituted two major dimensions of adult evaluations of how we dress, eat, and address others. Furthermore, the study suggested – consistent with Studies 2–4 – that such concerns imposed constraints on the alterability of social rules.

While supporting the constraint view, the findings run counter to other theoretical predictions. First, participants viewed social norms about dressing, eating, or speaking as alterable, which runs counter to any claim that children or adults confuse conventions with morality. Second, participants did not view these norms as infinitely alterable, which runs counter to any claim that norms about dressing, eating, or speaking are “pure” conventions. The norm manipulation, contrasting alternative, affect agent, and affect others variants, was significant for each of the norms examined in Studies 2–4.

This research yields new insights about how children and adults reason about conventionality, but does not undermine the distinction between conventional and non-conventional concerns. Like numerous past findings, the present findings indicated that children and adults frequently view social rules for how to dress, eat, play, and address others as alterable and contingent on existing rules or authority commands (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 2015; Turiel & Dahl, 2019). The present research documents how conventional considerations about authority commands, consensus, and tradition are integrated with non-conventional concerns about agents and others. For any coordination problem, some possible rules will be viewed as unacceptable for moral or other reasons; in many situations, this still leaves several possible and functionally similar rules (Lewis, 1969). It was in this sense we proposed that there are no pure conventions, insofar as the acceptance of any social rule is constrained by non-conventional concerns. Since the present research, like any empirical investigation, only examined a finite number of social norms, it cannot prove definitively that there are no pure conventions. However, none of the norms examined here, which included several prototypical “conventions,” were generally considered pure. We contend that his finding, along with the evidence reviewed in the Introduction, renders the notion of pure conventions difficult to entertain.

The constraint view also helps resolve disagreements about events that have been treated inconsistently in past research. Acts of intentional mess-making, such as spilling food, has sometimes been classified as conventional events and other times been classified as pragmatic events, insofar as they have intrinsic consequences for material order (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Dahl & Turiel, 2019; Smetana, 1989). How much material disorder people accept is likely constrained by how such disorder affects individuals. Individuals who are more easily disgusted may be less accepting of disorder, since they perceive more negative consequences of disgusting disorder (Nichols, 2002). Within the constraints of such welfare consequences, there are likely several norms for material order that household members would find acceptable. For instance, a family may adopt either the convention that children’s toys should be put away before every meal or the convention that toys should only be put away at the end of the day. The choice between these possible norms may be settled by consensus, tradition, or authority.

The finding that conventional considerations were constrained may be particularly surprising since the present study sampled participants from the Western United States. Many scholars have suggested that communities that are more politically conservative or traditionally organized would impose tighter constraints on conventions (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Nucci, 2001; Nucci, Camino, et al., 1996). The constraint view offers a framework for examining cultural and individual differences in evaluations of changes to conventions. It implies that variability in the perceived functions of some convention will predict variability in judgments about alterability of that convention. Consider dress codes at schools. As noted in the Introduction, Nucci, Camino, and colleagues (1996) found that many Brazilian children from working backgrounds thought that individuals should wear school uniforms even if the schools did not require uniforms. In contrast, middle-class children typically thought that it would be okay to refrain from wearing a school uniform if there was no dress code. Based on the constraint view, we hypothesize that working-class children, more than middle-class children, believed that the lack of school uniforms would be detrimental to the students in the school. Indeed, many people hold that school uniforms promote student discipline and learning (Nucci, Camino, et al., 1996; Oppenheimer, 2017). Even so, the working-class children likely deemed other aspects of the dress code, such as the color of uniforms, as conventional matters to be decided by school authorities.

This paper focused on how perceived effects of agents and others constrained conventions. Additional factors can also constrain the range of acceptable conventions. Particular cultural and historical contexts may render some conventions ineligible. When the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) controlled large areas in the Middle East, the International Society for Infant Studies changed its name to the International Congress for Infant Studies, making its acronym ICIS instead of ISIS (Hu, 2018). Religious rules can also conflict with proposed conventions. In 2011, the Iranian women’s soccer team was disqualified from a game because the players wore hijabs, as prescribed by their religious beliefs but in violation of the dress code of the international soccer association (FIFA, Ahmed, 2018). For the players, religious considerations constrained the range of dress codes they would find acceptable.

Even when rules are viewed as near-equivalent, there are often costs to switching from an existing rule to an alternative rule. The imperial system used in the United States and the International System of Units (S.I., or “metric” system) provide comparable solutions to the problem of recording, storing, and communicating measurements. While some argue that SI would be preferable to the imperial system, others note that a switch to the SI in the United States would be prohibitively expensive (Clayton, 2016). Indeed, Sweden encountered enormous logistical difficulties when switching from left-side driving to right-side driving in 1967 in order to align its traffic rules with the rest of continental Europe (Savage, 2018).

Some Implications for Debates on the Moral-Conventional Distinction

The constraint view adds clarity to a controversial area of research. The Introduction reviewed recurring debates about the moral-conventional distinction. This paper points to lessons for moving beyond these debates. The first lesson is that the moral-conventional distinction is, fundamentally, a distinction between psychological concerns, not between concrete norms or events. Children and adults categorically distinguish moral concerns with welfare, rights, justice and fairness from conventional concerns with authorities, consensus, and tradition. The second is to recognize that there may be no “purely” conventional norms or events, in the sense that any social norm pertains to welfare, rights, fairness, or justice. Norms for dressing, speaking, playing, and eating are adopted to promote some human aim and simultaneously limit the freedom of individuals.

The proposal that there are no purely conventional norms does not preclude use of the term “convention.” In the Introduction, we defined “convention” as shared, evaluative expectations for how to act that are alterable in the sense that there are alternative conventions that could have coordinated the interactions equally well (Lewis, 1969; Turiel, 1983). This usage of the term convention is compatible with the fact that individuals apply moral and other non-conventional considerations when evaluating conventions and conventional violations. Thus, we may call dress codes “conventions” whenever there are two or more acceptable conventions for how to dress in a given context. At the same time, the range of acceptable conventions is not infinite but constrained by non-conventional concerns.

The constraint view complements prior research and theory on domain-mixture and cross-domain coordination (Nucci et al., 2015; Turiel, 1983, 1989; Turiel & Dahl, 2019). In prior work, scholars have used the notions of domain-mixture and domain coordination to explain how individuals grapple with conflicts between existing conventions and moral concerns. The constraint view provides a framework for explaining reasoning and judgments about the conventions themselves. For instance, prior work has discussed how individuals coordinate conflicting concerns with authority commands and welfare; the constraint view seeks to explain how people evaluate those authority commands in the first place, prior to the conflict. That said, one framework is a seamless extension of the other and there may be no need to draw a sharp boundary between them.

Conclusion and Future Directions

This research opens several areas of research on how individuals impose constraints on the changeability of conventions. One limitation of this study was that we only recruited participants from a region in the Western United States, and our adult sample consisted of undergraduate students. Sampling from a wider range of populations would likely yield greater diversity of views on the changeability of social rules. Conflicts arise when individuals perceive different constraints, as when they do not share the same religious beliefs or informational assumptions about how different rules would impact agents or others (Wainryb, 1991). Debates about same-sex marriage tend to occur among people with differing religious beliefs (e.g., some believe that God prohibits same-sex marriage) and differing beliefs about how same sex-marriage would affect couples who marry and their children (Ball, 2015; Totenberg, 2015). These differing beliefs lead individuals to operate with different constraints on social rules regarding marriage (Turiel et al., 1991).

Another limitation is the reliance on judgments about hypothetical rules and events. It would be valuable to adapt the current framework for studying how children and adults, negotiate rule conflicts or proposed rule changes in real time (Hardecker, Schmidt, & Tomasello, 2017; Köymen et al., 2014). This would allow for assessments of arguments, emotional reactions, and behavioral reactions as individuals navigate negotiations between any differences in the constraints they perceive on the changeability of social rules.

This paper proposed and evaluated a new framework, the constraint view, for explaining reasoning and judgments about social conventions. The findings from four studies with preschoolers and adults supported the central contentions of the constraint view: Individuals viewed social norms—including prototypical conventions—as alterable within the constraints of concerns about the interests of agents and others. Other factors, like religious beliefs, can also impose constraints on the alterability of conventions. These constraints leave multiple acceptable solutions to social coordination problems. Conventions established by consensus, tradition, or authorities enable members of a social unit to select the same solution to their joint coordination problem (Lewis, 1969; Turiel, 1983). Once adopted, conventions affect the welfare of individuals and the functioning of social groups, and their violations elicit negative reactions from children and adults (Hardecker, Schmidt, Roden, & Tomasello, 2016; Rakoczy, Warneken, & Tomasello, 2008; Turiel, 2008b).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03HD087590). We thank Haden Dover, Erica Leverett, and other members of the Early Social Interaction Lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz for helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none