We evaluated the performance of a fourth-generation antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) assay for detecting HIV-1 infection on dried blood spots (DBS) both in a conventional laboratory environment and in an epidemiological survey corresponding to a real-life situation. Although a 2-log loss of sensitivity compared to that with plasma was observed when using DBS in an analytical analysis, the median delay of positivity between DBS and crude serum during the early phase postacute infection was 7 days.

KEYWORDS: DBS, human immunodeficiency virus

ABSTRACT

We evaluated the performance of a fourth-generation antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) assay for detecting HIV-1 infection on dried blood spots (DBS) both in a conventional laboratory environment and in an epidemiological survey corresponding to a real-life situation. Although a 2-log loss of sensitivity compared to that with plasma was observed when using DBS in an analytical analysis, the median delay of positivity between DBS and crude serum during the early phase postacute infection was 7 days. The performance of the fourth-generation assay on DBS was approximately similar to that of a third-generation (antibody only) assay using crude serum samples. Among 2,646 participants of a cross-sectional study in a population of men having sex with men, 428 DBS were found reactive, but negative results were obtained from 5 DBS collected from individuals who self-reported a positive HIV status, confirmed by detection of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in their DBS. The data generated allowed us to estimate a sensitivity of 98.8% of the fourth-generation assay/DBS strategy in a high-risk population, even including a broad majority of individuals on ARV treatment among those HIV positive. Our study brings additional proofs that DBS testing using a fourth-generation immunoassay is a reliable strategy able to provide alternative approaches for both individual HIV testing and surveillance of various populations.

INTRODUCTION

Dried blood samples collected on filter paper (DBS) have been used as alternative specimens to serum/plasma collection either to increase access to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing at the individual level or to perform seroepidemiological studies at the population level (1–4). This alternative has been used also for a wide range of infectious diseases, including detection of antibodies, antigens, or nucleic acids, particularly in resource-limited countries and hard-to-reach populations (2, 5–10). DBS have several advantages over sample collection by phlebotomy. It is an easy and inexpensive means of collecting samples using a finger or heel prick and spotting whole blood directly onto filter paper. DBS can be stored for a short period of time before shipping at ambient temperature from peripheral sites to a central laboratory.

Fourth-generation antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) immunoassays are now considered the gold standard for HIV screening due to improved detection during the early phase of infection (11–15). Although several studies have already analyzed the performance of such assays using DBS (16–20), we wanted to characterize further the sensitivity in the context of an HIV surveillance program among men who have sex with men (MSM), the Prevagay study. Indeed, two main situations may limit the sensitivity in a high-risk population. The first is the situation of acute or recent infection, when only a low antibody titer or a low antibody avidity is present (15). The second is the situation of individuals who have been treated efficiently, particularly early after infection, and remain with an undetectable virus load for many years (21–24). In this case, the lack of antigenic stimulation leads to a regular decrease of antibody level that might alter the performance of detection when using DBS. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to analyze the sensitivity of a fourth-generation Ag/Ab assay for a selection of informative sample specimens in a conventional laboratory environment and, in addition, within a large cross-sectional survey in which the biological results obtained on DBS were compared to those from questionnaires, including the self-reported HIV status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted to evaluate with different approaches the sensitivity of the Bio-Rad fourth-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay; Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) using DBS. Any run of the assay was performed strictly according to the recommendations of the manufacturer using 75 μl of either serum samples or eluates from DBS. The results were expressed using the ratio absorbance/cutoff value.

Analytical performance comparing plasma versus DBS.

We used EDTA-whole blood samples from 10 unselected HIV-1-positive individuals received in the laboratory for viral load (VL) quantification. From each blood sample, 20 μl of blood was spotted onto a filter paper card (903 GEHC grade; GE Healthcare) and left to dry overnight at room temperature, whereas the rest of the sample was centrifuged to collect the plasma.

The DBS were cut out the next day with a punch to obtain a 6-mm-diameter circle, which was placed in 150 μl of 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer containing 10% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-BSA-TW) and then incubated overnight at 4°C. For each sample, both the plasma and the DBS eluate were diluted in PBS-BSA-TW (10-fold dilutions from 10−1 to 10−6). Each dilution was directly transferred to ELISA microplates (75 μl per well), and the subsequent steps were carried out in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Performance using samples from HIV-1 patients under antiretroviral treatment.

Ninety-one consecutive EDTA-whole blood samples received in the laboratory for VL quantification from HIV-1-positive individuals under antiretroviral treatment (ART) were used. The duration of infection, the duration of treatment, and the duration of undetectable VL were highly variable among this set of patients. VL was undetectable (<1.6 log copies/ml) for 74 of them (81.3%) and ranged between 1.61 and 5.20 log copies/ml for the others. DBS were prepared with 20 μl of each blood sample as described above. The eluates were obtained as described above, and 75 μl of each was directly transferred to ELISA microplates, the subsequent steps being carried out in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Performance using sequential sera from panels of seroconverters.

Twelve HIV-1 seroconversion panels from Boston Biomedica, Inc. (BBI, West Bridgewater, MA, USA) were used (PRB 917, 923, 932, 936, 937, 941, 943, 944, 945, 947, 949, and 952), including 44 samples. Starting from the first sample positive for p24 antigen (p24 Ag), there were 2 to 5 samples per panel ranging from 2 to 23 days after detection of p24 antigenemia. The panel samples were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 with washed group O red blood cells from HIV-negative donors, and 20 μl of each reconstituted blood sample was immediately spotted onto filter paper cards and left to dry overnight at room temperature. The eluates were obtained as described above, and 75 μl of each was directly transferred to ELISA microplates, the subsequent steps being carried out in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. The results were compared to those obtained with the crude serum samples using the same fourth-generation ELISA (Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay) and the third-generation antibody only assay from the same manufacturer (Genscreen HIV 1/2) (11).

Prevagay study.

The Prevagay 2015 survey is an anonymous cross-sectional study conducted in five French metropolitan cities (Lille, Lyon, Montpellier, Nice, and Paris) among MSM attending commercial gay venues. The methodology and characteristics of study participants were described previously (25, 26). In brief, 247 interventions were performed between September and December 2015 in 26 bars/clubs without sex, 15 backrooms/sex clubs, and 19 saunas. MSM were eligible for the survey if they were at least 18 years old, had had sex with men in the previous 12 months, could read and speak French, agreed to both perform finger-prick blood self-sampling and answer a questionnaire of approximately 60 items using electronic tablets. Questionnaire data provided information on demographics and behavioral characteristics and included self-reported HIV status, history of testing, and antiretroviral treatment. Sample collection consisted in 8 drops of whole blood spotted on a filter paper card (903 GEHC grade; GE Healthcare). DBS cards were dried at room temperature and then kept in individual zipped plastic bags. Next, DBS were stored at room temperature before being sent to the National Reference Center for HIV in Tours on a weekly basis. Participants were informed that they would not receive the results of the test, but each one was strongly encouraged by the trained field workers carrying out the intervention to have a screening test in a voluntary counseling and testing center (VCTC). All participants received flyers with addresses and opening hours of nearby VCTCs.

The eluates were obtained as described above, and 75 μl of each was directly transferred to Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo microplates, the subsequent steps being carried out in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

HIV-positive specimens were confirmed by a combination of an assay for recent infection, serotyping, and Western blotting (HIV Blot 2.2; MP Diagnostics, Singapore) as previously described (27–29). Briefly, for Western blotting, one DBS was cut out as described above, placed in 1 ml of PBS-BSA-TW buffer, and then incubated overnight at 4°C. The DBS eluate was directly transferred to Western blot strips, and the subsequent steps were carried out in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. Additional analyses included detection of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS; Acquity UPLC–Acquity TQD) as previously described (30) with a slightly modified extraction for the adaptation to DBS (31). The method allowed us to detect all ARVs available in France.

The research ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes) from Paris Ile de France VI (Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpétrière) and the institutional review board of the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (ANSM, Paris) approved the study.

RESULTS

Analytical performance comparing plasma versus DBS.

Results from the comparative testing of ten plasma samples and their corresponding DBS eluates, both undiluted and serially diluted, are shown in Fig. 1. A 2-log difference between DBS and plasma was observed for most of the samples. However, due to the high sensitivity of the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay, the DBS eluates were still positive at dilutions of 10−2 or 10−3 for eight of them and at 10−1 or 10−4 for the two others.

FIG 1.

Reactivity of the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay with DBS compared to that with plasma. An absorbance/cutoff ratio of ≥1.0 designates a reactive sample. A 2-log difference between DBS and plasma was observed for the majority of samples.

Performance using samples from HIV-1-positive individuals under antiretroviral treatment.

All 91 DBS from ARV-treated HIV-1-positive patients provided a positive result. Among them, 85 were strongly positive at saturation of absorbance measurement as shown in Fig. 2. The absorbance/cutoff ratio was between 5.8 and 10.9 for the six others, still clearly above the threshold.

FIG 2.

Performance of the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay with DBS from HIV-infected individuals on ARV treatment (left) and in the Prevagay study (right). Dots indicate the distribution of signals, where an absorbance/cutoff ratio of ≥1.0 designates a reactive sample. On the left, 91 DBS from ARV-treated HIV-infected individuals provided a positive result, including 85 DBS with strong signals above the saturation signal (≥12.0). On the right, 428 DBS were reactive among 2,646 participants of the Prevagay study. In addition, 5 DBS with a negative test but from individuals reporting an HIV-positive status are represented, including 2 samples just below the threshold.

Performance using sequential sera from panels of seroconverters.

Performance at detecting HIV-1 infection during the first weeks postexposure was evaluated by comparing results from sera and simulated DBS of sequential samples collected in seroconverters. Among the 12 panels tested, the fourth-generation ELISA was positive on the first p24 Ag-positive sample in 10 cases when using the standard procedure with the crude serum sample. Although the signals were lower when using DBS, the assay was positive at the same time as with the crude serum sample in 3 of the 12 cases (PRB923, PRB936, and PRB947) (Fig. 3) and provided a result in the gray zone for a fourth (PRB949). The delay of positivity between DBS and crude serum for the remaining 8 samples was between 2 (PRB945) and 12 days (PRB944), with a median of 7 days. To provide additional data on the characteristics of our DBS procedure, we compared the performance of the fourth-generation assay using DBS to that of a third-generation assay (detection of antibody only) using crude serum samples. The fourth-generation DBS assay was positive earlier than the third-generation ELISA using crude serum samples in 4 cases (PRB917, PRB923, PRB936, and PRB943), was positive at the same time in two cases (PRB937 and PRB947), and became positive with a delay ranging from 2 to 7 days (median, 3 days) in the remaining 6 cases.

FIG 3.

Performance of the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay with DBS in the context of acute infection. Sequential sera from 12 seroconversion panels (PRB 917 to PRB 952) were tested, with 2 to 5 samples per panel ranging from 2 to 23 days after detection of p24 antigenemia (day 0). We compared the performance of the fourth-generation assay by using DBS or crude serum (4th Gen Ag/Ab DBS and 4th Gen Ag/Ab, respectively) to that of a third-generation assay using crude serum samples (3rd Gen Ab). An absorbance/cutoff ratio of ≥1.0 designates a reactive sample. The time scale is in days.

Prevagay study.

The study recruited 2,646 participants from whom DBS were collected (25, 26). The fourth-generation assay was reactive for 428 of them (16.2%), including 372 specimens from participants who reported that they were HIV positive, 38 from participants who reported that they were seronegative, and 18 from individuals who reported that they were unaware of their HIV status (n = 11) or were no longer sure of being seronegative (n = 7). Among the 428 reactive samples, 374 (87.4%) were strongly positive, at saturation of absorbance measurement. The distribution of the absorbance/cutoff ratios of the positive specimens is shown in Fig. 2. All the reactive samples were confirmed HIV-1 positive by serotyping and/or Western blotting.

Surprisingly, 12 DBS from individuals who self-reported that they were HIV positive were nonreactive with the fourth-generation assay. These 12 cases were further analyzed by additional assays to identify the reason for the discrepancy (Table 1).

-

•

They were tested via a second blood spot by the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay, confirming the first negative result. The ratio absorbance/cutoff value was in the same range as in the two runs for all 12 cases, including two cases (11538 and 12712) for which the ratio was just below the threshold (Table 1).

-

•

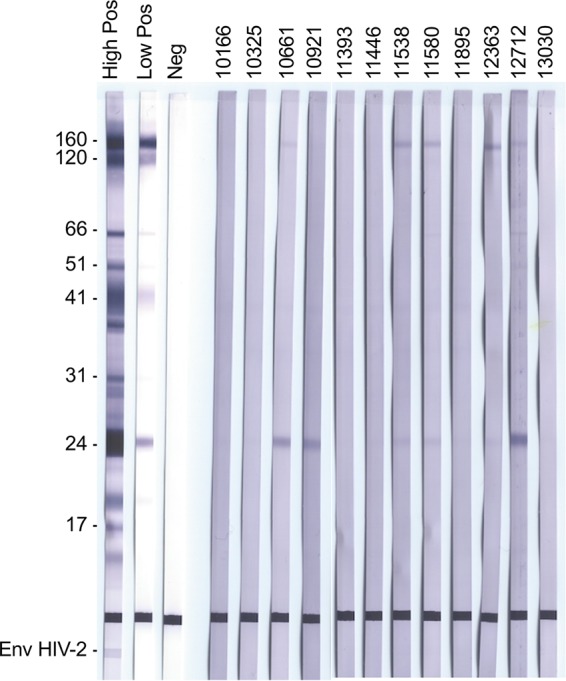

They were tested by Western blotting, which showed a weak reactivity against two major HIV antigens, gp160 and p24, for five specimens, strongly suggesting that the corresponding individuals were truly HIV positive (Fig. 4). One DBS (10921) exhibited weak reactivity against p24 only, and six DBS were nonreactive.

-

•

The presence of ARV was detected in five DBS, which were those weakly reactive by Western blotting (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive analysis of 12 nonreactive DBS with the fourth-generation assay from individuals who self-reported HIV positivity

| DBS no. | Genscreen HIV Ag-Ab ratioa

|

Assay resultb

|

Conclusion for HIVc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First run | Second run | Western blotting | ARV | ||

| 10166 | 0.43 | 0.03 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 10325 | 0.59 | 0.04 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 10661 | 0.66 | 0.32 | gp120, p24 | ABC-TDF-DTG | Pos |

| 10921 | 0.00 | 0.00 | p24 | Neg | Ind |

| 11393 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 11446 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 11538 | 0.85 | 0.82 | gp120, p24 | FTC-RPV | Pos |

| 11580 | 0.47 | 0.50 | gp120, p24 | FTC-TDF-RPV | Pos |

| 11895 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 12363 | 0.24 | 0.18 | gp120, p24 | DRV-RTV | Pos |

| 12712 | 0.94 | 0.77 | gp120, 66/51, p24 | FTC-TDF | Pos |

| 13030 | 0.00 | 0.06 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

Ratio of absorbance/cutoff value.

Neg, negative; ABC, abacavir; DRV, darunavir; DTG, dolutegravir; FTC, emtricitabine; RPV, rilpivirine; RTV, ritonavir; TDF, tenofovir.

Neg, negative; Pos, positive; Ind, indeterminate.

FIG 4.

Western blots for the twelve DBS from individuals who self-reported that they were HIV positive. High Pos, high-positive control; Low Pos, low-positive control; Neg, negative control.

Based on the entire set of data, we considered that five of the twelve samples, i.e., those five reactive by Western blotting and positive for the presence of ARV drugs, were issued from HIV-infected patients. These 5 cases included the 2 DBS that were negative in the fourth-generation assay but reacting just below the threshold (Table 1). We considered that six DBS that were nonreactive by Western blotting and in which ARVs were not detected were not from HIV-infected patients, suggesting some limitations of data collected through self-reports. One specimen remained indeterminate, as it was weakly reactive for the antibody to p24 but without detectable ARV.

Taken together, the data suggest that 428 of 433 HIV-1-positive individuals were detected by the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay during the Prevagay study, leading to an estimated sensitivity of 98.8% for our DBS strategy.

DISCUSSION

DBS have become a popular method in a variety of micro-blood-sampling techniques in the life sciences sector (2, 5, 6). They have gained a significant role in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, especially in the HIV/AIDS field, where they have been used either for diagnosis and monitoring at the individual level or to perform surveillance studies at the population level (3, 4, 19, 20). Since the mid-1980s, extraordinary progress in improving the sensitivity of serological assays for HIV infection has been made continuously, and the fourth-generation assays are now recommended for HIV screening (12–15). However, the amount of virological markers, particularly, antibodies, that can be eluted from DBS is much lower than that contained in the volume of plasma that is required for standard procedures, leading to an obvious risk of loss of sensitivity of the assays. Indeed, there are two major situations in which a low antibody amount may lead to a false-negative result when using DBS. The first one corresponds to acute or recent infections when the antibody response is just emerging (11, 12). The second one, much less recognized, is that of patients treated efficiently, particularly, early after infection, for whom the lack of antigenic stimulation leads to a regular decrease, even a vanishing, of anti-HIV antibodies (21–24). In the present study, we wanted to better characterize the sensitivity of the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab combo assay, taking into account these limitations, particularly, by capitalizing on a large cross-sectional survey in which the biological results obtained from DBS with this assay were compared to the self-reported HIV status.

In a first analytical evaluation of the performance through the comparison of dilutions of plasma samples and of the corresponding DBS eluates, we estimated a 2-log loss of sensitivity when using DBS. However, due to the high sensitivity of the fourth-generation assay, antibodies to HIV-1 were still detectable in most of the eluates, even at dilution of ≤10−2, suggesting that the loss of sensitivity using DBS would not be a major limitation. This was confirmed by the analysis of DBS prepared with simulated whole blood reconstituted with sequential sera from panels of seroconverters. Indeed, the assay on DBS was positive in the same earliest sample as with the standard procedure for 3 of 12 seroconversion panels, and the median delay of positivity between DBS and crude serum was 7 days for the other cases. This is less than the 10- to 15-day reactivity interval observed between fourth-generation Ag/Ab immunoassays and rapid tests (32), which are recommended for HIV screening in resource-limited countries and hard-to-reach populations. Our data are in accordance with a previous report by Kania et al., who showed that two fourth-generation Ag/Ab immunoassays performed on dried serum spots detected 87% of seroconverters (17), although their study was cross-sectional and did not allow as precise of a characterization of the delay in detection as ours. In addition, we found that the performance of the fourth-generation assay on DBS was approximately similar to that of a third-generation (antibody only) assay using crude serum samples, since one-half of the seroconversion panels were detected earlier or in the same sample, the remaining panels were detected with a median delay of only 3 days. Our data are also largely in accordance with those from Luo et al., who analyzed seroconversion panels and demonstrated that although the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab assay on DBS detected fewer infections than on crude plasma, it detected more infections than the third-generation assay in plasma (18).

The sensitivity of the Genscreen Ultra HIV Ag-Ab assay on DBS was evaluated with samples from 91 ARV-treated HIV-1-positive patients. All were found positive, providing some confidence on the performance of the procedure if used for seroepidemiological surveys in high-risk populations where a high percentage of individuals might be under treatment. It was the case for the Prevagay 2015 survey, whose one aim was to assess HIV prevalence among MSM attending gay venues in five French cities. Paired biological results and self-administered questionnaires were available for 2,646 participants, allowing us to compare the results of the DBS assay with the self-reported HIV status in a real-life situation. The estimated HIV prevalence in this population was 16.1% (95% confidence interval [CI 95%], 12.5 to 20.4) (25).

Among 428 reactive DBS, 372 were from participants who reported that they were HIV positive, providing concordant results, and 56 were from participants who reported that they were seronegative, no longer sure of being seronegative, or unaware of their HIV status. However, DBS from 12 individuals who self-reported that they were HIV positive were nonreactive with the fourth-generation assay, justifying further analyses to unravel the data. Since the reliability of self-reported status may be questionable, these 12 cases were further analyzed using two complementary approaches: detection of antibodies to HIV by Western blotting and detection of ARVs as indirect witnesses of known HIV infection. When performed on DBS, Western blotting can be considered as sensitive as ELISA on crude plasma (33, 34). Indeed, Western blotting was performed with one punch of dried blood, containing approximately 7 μl of plasma (18), which was directly eluted in 1 ml of dilution buffer. Therefore, the volume of serum or plasma was almost equivalent to that recommended in the standard Western blotting procedure in which a 1:100 dilution is used, whereas the ELISA procedure requires undiluted serum or plasma.

Among these 12 cases, 5 were confirmed HIV-1 positive by the presence of antibodies to at least two HIV antigens (gp120 and p24), and one was indeterminate due to the sole presence of antibodies to p24. Interestingly, two to three ARV drugs were detected in each of the 5 Western blot-positive DBS, confirming that these 5 individuals were HIV positive. A treatment initiation shortly after primary infection followed by several months or years with undetectable viremia might explain this result, as previously reported (21–24). However, although these 5 patients declared that they had been infected for several years, we did not have information concerning the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis nor the delay between diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Therefore, there were 6 to 7 participants who self-reported a positive HIV status albeit they were probably seronegative. Similarly, to illustrate the limitations of self-reports, two to three ARV molecules were detected in DBS from 23 of the 56 participants who reported that they were seronegative (or no longer sure of being seronegative or unaware of their HIV status), suggesting that they were HIV infected and treated but did not respond fairly to the questionnaire or that the environmental conditions to fill the questionnaire were not confidential enough. Alternatively, detecting ARVs in DBS could be the result of a preexposure prophylaxis in some individuals.

The data generated in the Prevagay 2015 study allowed us to evaluate the clinical performance of HIV screening on DBS with a fourth-generation immunoassay, leading to an estimated sensitivity of 98.8%. Although the self-report can be considered nonoptimal for comparison in our study, a similar sensitivity, 99.1%, was observed in a recent study in which corresponding plasma and DBS were tested in parallel with the Architect HIV Ab/Ag assay (19).

In conclusion, our data provide additional proof that DBS testing using a fourth-generation immunoassay is a reliable strategy able to provide alternative approaches for both individual testing and surveillance of various populations. There is an urgent need to improve access to HIV diagnosis, both in resource-limited settings and difficult-to-reach high-risk populations in high-income countries. The minimal invasiveness of sampling and the ease of handling, storing, and transporting DBS offer additional opportunities to reach the first 90% of the 90-90-90 UNAIDS target. This strategy can be applied to highly diverse contexts, including, for instance, the testing of self-collected DBS delivered through the postal service (35, 36).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by grants from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche sur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales (ANRS, Paris, France) and Santé Publique France (SPF, Saint-Maurice, France).

The 2015 Prevagay working group was composed of A. Velter, A. Alexandre, F. Barin, S. Chevaliez, D. Friboulet, M. Jauffret Roustide, F. Lot, N. Lydié, G. Peytavin, O. Robineau, L. Saboni, C. Sauvage, and C. Sommen.

We thank Lucie Léon, Yann the Strat, Laurence Meyer, and Josiane Warzawski for their helpful advice. We thank all those who agreed to participate in the Prevagay 2015 study. We also thank the employees of the association ENIPSE who carried out the study (Sébastien Cambau, Jérôme Derrien, Sylvain Guillet, Loïc Jourdan, Cyril Kaminski, Vivien Lugaz, Cedric Péjou, Erika Thomas Des Chenes, Florian Therond, and Richard De Wever) and the associations that supported the study throughout, including AIDES (Vincent Coquelin), Act Up (Hugues Fisher), Le 190 (Michel Oyahon), and Sidaction (Sandrine Fournier). We also thank Kevin Babaud, Céline Desouche, and Damien Thierry for their excellent technical assistance, and Pascal Chaud, Agnès Lepoutre, Philippe Malfait, Bakhao Ndiaye, Cyril Rousseau, Christine Saura, Yassoungo Silue, and Stephanie Vandentorren from regional units of Santé Publique France for their region implication. We also thank all the institutions that agreed to participate and all the associations who facilitated the study.

Data collection was carried out by Brulé Ville & Associé (BVA).

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS/WHO. 2009. Guidelines for using HIV testing technologies in surveillance. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland: www.who.int/hiv/pub/surveillance/hiv_testing_technologies/en/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snijdewind IJM, van Kampen JJA, Fraaij PLA, van der Ende ME, Osterhaus A, Gruters RA. 2012. Current and future applications of dried blood spots in viral disease management. Antiviral Res 93:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamers RL, Smit PW, Stevens W, Schuurman R, Rinke de Wit TF. 2009. Dried fluid spots for HIV type-1 viral load and resistance genotyping: a systematic review. Antivir Ther 14:619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smit PW, Sollis KA, Fiscus S, Ford N, Vitoria M, Essajee S, Barnett D, Cheng B, Crowe SM, Denny T, Landay A, Stevens W, Habiyambere V, Perriens JH, Peeling RW. 2014. Systematic review of the use of dried blood spots for monitoring HIV viral load and for early infant diagnosis. PLoS One 9:e86461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker SP, Cubitt WD. 1999. The use of the dried blood spot sample in epidemiological studies. J Clin Pathol 52:633–639. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.9.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meesters RJ, Hooff GP. 2013. State-of-the-art dried blood spot analysis: an overview of recent advances and future trends. Bioanalysis 5:2187–2208. doi: 10.4155/bio.13.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villa E, Cartolari R, Bellentani S, Rivasi P, Casolo G, Manenti F. 1981. Hepatitis B virus markers on dried blood spots. A new tool for epidemiological research. J Clin Pathol 34:809–812. doi: 10.1136/jcp.34.7.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendy M, Kirk GD, van der Sande M, Jeng-Barry A, Lesi OA, Hainaut P, Sam O, McConkey S, Whittle H. 2005. Hepatitis B surface antigenaemia and alpha-foetoprotein detection from dried blood spots: applications to field-based studies and to clinical care in hepatitis B virus endemic areas. J Viral Hepat 12:642–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuaillon E, Mondain A-M, Meroueh F, Ottomani L, Picot M-C, Nagot N, Van de Perre P, Ducos J. 2010. Dried blood spot for hepatitis C virus serology and molecular testing. Hepatology 51:752–758. doi: 10.1002/hep.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soulier A, Poiteau L, Rosa I, Hezode C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Pawlotsky JM, Chevaliez S. 2016. Dried blood spots: a tool to ensure broad access to hepatitis C screening, diagnosis, and treatment monitoring. J Infect Dis 213:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ly TD, Laperche S, Brennan C, Vallari A, Ebel A, Hunt J, Martin L, Daghfal D, Schochetman G, Devare S. 2004. Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of six HIV combined p24 antigen and antibody assays. J Virol Methods 122:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Dragavon J, Thomas KK, Brennan CA, Devare SG, Wood RW, Golden MR. 2009. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin Infect Dis 49:444–453. doi: 10.1086/600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Branson BM. 2010. The future of HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 55:S102–S105. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbca44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone M, Bainbridge J, Sanchez AM, Keating SM, Pappas A, Rountree W, Todd C, Bakkour S, Manak M, Peel SA, Coombs RW, Ramos EM, Shriver MK, Contestable P, Nair SV, Wilson DH, Stengelin M, Murphy G, Hewlett I, Denny TN, Busch MP. 2018. Comparison of detection limits of fourth- and fifth-generation combination HIV antigen-antibody, p24 antigen and viral load assays on diverse HIV isolates. J Clin Microbiol 56:e02045-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02045-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parekh BS, Ou CY, Fonjungo PN, Kalou MB, Rottinghaus E, Puren A, Alexander H, Hurlston Cox M, Nkengasong JN. 2018. Diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 32:e00064-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00064-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakshmi V, Sudha T, Bhanurekha M, Dandona L. 2007. Evaluation of the Murex HIV Ag/Ab combination assay when used with dried blood spots. Clin Microbiol Infect 13:1134–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kania D, Nguyen Truong T, Montoya A, Nagot N, van de Perre P, Tuaillon E. 2015. Performances of fourth generation HIV antigen/antibody assays on filter paper for detection of early HIV infections. J Clin Virol 62:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo W, Davis G, Li L, Kathleen Shriver M, Mei J, Styer LM, Parker MM, Smith A, Paz-Bailey G, Ethridge S, Wesolowski L, Michele Owen S, Masciotra S. 2017. Evaluation of dried blood spots protocols with the Bio-Rad GS HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA and Geenius HIV 1/2 supplemental assay. J Clin Virol 91:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mössner BK, Staugaard B, Jensen J, Lillevang ST, Christensen PB, Holm DK. 2016. Dried blood spots, valid screening for viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus in real life. World J Gastroenterol 22:7604–7612. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i33.7604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vázquez-Morón S, Ryan P, Ardizone-Jiménez B, Martín D, Troya J, Cuevas G, Valencia J, Jimenez-Sousa MA, Avellón A, Resino S. 2018. Evaluation of dried blood spot samples for screening of hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus in a real-world setting. Sci Rep 8:1858. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hare CB, Pappalardo BL, Busch MP, Karlsson AC, Phelps BH, Alexander SS, Bentsen C, Ramstead CA, Nixon DF, Levy JA, Hecht FM. 2006. Seroreversion in subjects receiving antiretroviral therapy during acute/early HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 42:700–708. doi: 10.1086/500215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaillon A, Le Vu S, Brunet S, Gras G, Bastides F, Bernard L, Meyer L, Barin F. 2012. Decreased specificity of an assay for recent infection in HIV-1-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral treatment. Clin Vaccine Immunol 19:1248–1253. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00120-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Souza MS, Pinyakorn S, Akapirat S, Pattanachaiwit S, Fletcher JL, Chomchey N, Kroon ED, Ubolyam S, Michael NL, Robb ML, Phanuphak P, Kim JH, Phanuphak N, Ananworanich J, RV254/SEARCH010 Study Group. 2016. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy during acute HIV-1 infection leads to a high rate of nonreactive HIV serology. Clin Infect Dis 63:555–561. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefic K, Novelli S, Mahjoub N, Seng R, Molina JM, Cheneau C, Barin F, Chaix ML, Meyer ML, Delaugerre C, French National Agency for Research on AIDS and Viral Hepatitis (ANRS) Primo study group. 2018. Nonreactive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 rapid tests after sustained viral suppression following antiretroviral therapy initiation during primary infection. J Infect Dis 217:1793–1797. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velter A, Sauvage C, Saboni L, Sommen C, Alexandre A, Lydié N, Peytavin G, Barin F, Lot F, Prevagay Group 2015. 2017. High prevalence estimate among men who have sex with men attending gay venues in five French cities – PREVAGAY 2015. Bull Epidemiol Hebd (Paris) 18:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sommen C, Saboni L, Sauvage C, Alexandre A, Lot F, Barin F, Velter A. 2018. Time location sampling in men who have sex with men in the HIV context: the importance of taking into account sampling weights and frequency of venue attendance. Epidemiol Infect 146:913–919. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818000675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barin F, Plantier JC, Brand D, Brunet S, Moreau A, Liandier B, Thierry D, Cazein F, Lot F, Semaille C, Desenclos JC. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus serotyping on dried blood spots as a screening tool for the surveillance of the AIDS epidemic. J Med Virol 78:S13–S18. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semaille C, Barin F, Cazein F, Pillonel J, Lot F, Brand D, Plantier JC, Bernillon P, Le Vu S, Pinget R, Desenclos JC. 2007. Monitoring the dynamics of the HIV epidemic using assays for recent infection and serotyping among new HIV diagnoses: experience after 2 years in France. J Infect Dis 196:377–383. doi: 10.1086/519387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velter A, Barin F, Bouyssou A, Guinard J, Leon L, Le Vu S, Pillonel J, Spire B, Semaille C. 2013. HIV prevalence and sexual risk behaviors associated with awareness of HIV status among men who have sex with men in Paris, France. AIDS Behav 17:1266–1278. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung BH, Rezk NL, Bridges AS, Corbett AH, Kashuba A. 2007. Simultaneous determination of 17 antiretroviral drugs in human plasma for quantitative analysis with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr 21:1095–1104. doi: 10.1002/bmc.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Vu S, Velter A, Meyer L, Peytavin G, Guinard J, Pillonel J, Barin F, Semaille C. 2012. Biomarker-based HIV incidence in a community sample of men who have sex with men in Paris, France. PLoS One 7:e39872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaney KP, Hanson DL, Masciotra S, Ethridge SF, Wesolowski L, Michele Owen S. 2017. Time until emergence of HIV test reactivity following infection with HIV-1: implications for interpreting test results and retesting after exposure. Clin Infect Dis 64:53–59. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan TJ, San Antonio-Gaddy M, Richardson-Moore A, Styer LM, Bigelow-Saulsbery D, Parker MM. 2013. Expansion of HIV screening to non-clinical venues is aided by the use of dried blood spots for Western blot confirmation. J Clin Virol 58S:e123–e126. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manak MM, Hack HR, Shutt AL, Danboise BA, Jagodzinski LL, Peel SA. 2018. Stability of human immunodeficiency virus serological markers in samples collected as HemaSpot and Whatman 903 dried blood spots. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00933-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00933-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takano M, Iwahashi K, Satoh I, Araki J, Kinami T, Ikushima Y, Fukuhara T, Obinata H, Nakayama Y, Kikuchi Y, Oka S, and the HIV Check Study group. 2018. Assessment of HIV prevalence among MSM in Tokyo using self-collected dried blood spots delivered through the postal service. BMC Infect Dis 18:627. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3491-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lydié N, Saboni L, Gautier A, Brouard C, Chevaliez S, Barin F, Larsen C, Lot F, Rahib D. 2018. Innovative approach for enhancing testing of HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C in the general population: protocol for an acceptability and feasibility study (BaroTest 2016). JMIR Res Protoc 7:e180. doi: 10.2196/resprot.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]