Abstract

Although there is general consensus that altered brain structure and function underpins addictive disorders, clinicians working in addiction treatment rarely incorporate neuroscience-informed approaches into their practice. We recently launched the Neuroscience Interest Group within the International Society of Addiction Medicine (ISAM-NIG) to promote initiatives to bridge this gap. This article summarizes the ISAM-NIG key priorities and strategies to achieve implementation of addiction neuroscience knowledge and tools for the assessment and treatment of substance use disorders. We cover two assessment areas: cognitive assessment and neuroimaging, and two interventional areas: cognitive training/remediation and neuromodulation, where we identify key challenges and proposed solutions. We reason that incorporating cognitive assessment into clinical settings requires the identification of constructs that predict meaningful clinical outcomes. Other requirements are the development of measures that are easily-administered, reliable, and ecologically-valid. Translation of neuroimaging techniques requires the development of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and testing the cost-effectiveness of these biomarkers in individualized prediction algorithms for relapse prevention and treatment selection. Integration of cognitive assessments with neuroimaging can provide multilevel targets including neural, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes for neuroscience-informed interventions. Application of neuroscience-informed interventions including cognitive training/remediation and neuromodulation requires clear pathways to design treatments based on multilevel targets, additional evidence from randomized trials and subsequent clinical implementation, including evaluation of cost-effectiveness. We propose to address these challenges by promoting international collaboration between researchers and clinicians, developing harmonized protocols and data management systems, and prioritizing multi-site research that focuses on improving clinical outcomes.

Keywords: neuroscience, addiction medicine, treatment, substance use disorder, fMRI, neuromodulation, neuropsychological assessment, cognitive rehabilitation

Introduction

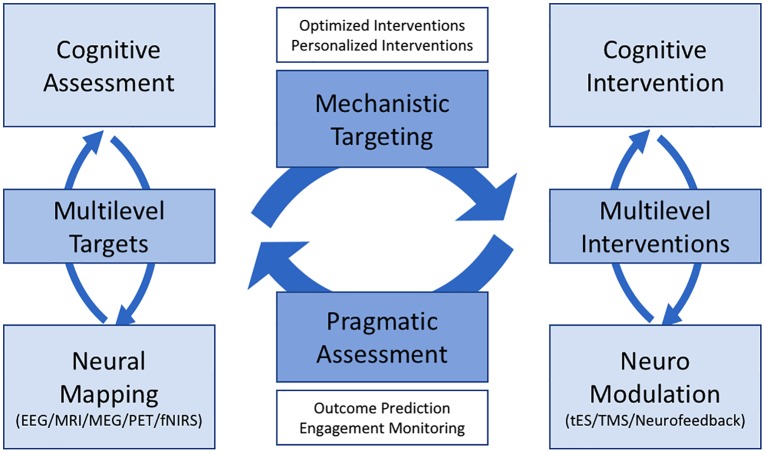

The past two decades have seen significant advances in our understanding of the neuroscience of addiction and its implications for practice [reviewed in (1–3)]. However, despite such insights, there is a substantial lag in translating these findings into everyday practice, with few clinicians incorporating neuroscience-informed interventions in their routine practice (4). We recently launched the Neuroscience Interest Group within the International Society of Addiction Medicine (ISAM-NIG) to promote initiatives to bridge this gap between knowledge and practice. This article introduces the ISAM-NIG key priorities and strategies to achieve implementation of addiction neuroscience knowledge and tools in the assessment and treatment of substance use disorders (SUD). We cover four broad areas: (1) cognitive assessment, (2) neuroimaging, (3) cognitive training and remediation, and (4) neuromodulation. Cognitive assessment and neuroimaging provide multilevel biomarkers (neural circuits, cognitive processes, and behaviors) to be targeted with cognitive and neuromodulation interventions. Cognitive training/remediation and neuromodulation provide neuroscience-informed interventions to ameliorate neural, cognitive, and related behavioral alterations and potentially improve clinical outcomes in people with SUD. In the following sections, we review the current knowledge and challenges in each of these areas and provide ISAM-NIG recommendations to link knowledge and practice. Our goal is for researchers and clinicians to work collaboratively to address these challenges and recommendations. Cutting across the four areas, we focus on cognitive and neural systems that predict meaningful clinical outcomes for people with SUD and opportunities for harmonized assessment and intervention protocols.

Cognitive Assessment

Neuropsychological studies consistently demonstrate that many people with SUD exhibit mild to moderately severe cognitive deficits in processing speed, selective, and sustained attention, episodic memory, executive functions (EF: working memory, response inhibition, shifting and higher-order functions such as reasoning, problem-solving, and planning), decision-making and social cognition (5–10). Furthermore, neurobiologically-informed theories and expert consensus have identified additional cognitive changes not typically assessed by traditional neuropsychological measures, namely, negative affectivity and reward-related processes (e.g., reward expectancy, valuation and learning, and habits-compulsivity) (11–13).

Cognitive deficits in SUD have moderate longevity, and although there is abstinence-related recovery (14–16), these deficits may significantly complicate treatment efforts during the first 3 to 6 months after discontinuation of drug use. Thus, one of the most critical implications of cognitive deficits for SUD is their potential negative impact on treatment retention and adherence, in addition to clinical outcomes such as craving, relapse, and quality of life. A systematic review of prospective cognitive studies measuring treatment retention and relapse across different SUD suggested that measures of processing speed and accuracy during attention and reasoning tasks (MicroCog test battery) were the only consistent predictors of treatment retention, whereas tests of decision-making (Iowa and Cambridge Gambling Tasks) were the only consistent predictors of relapse (1). A later review that focused on substance-specific cognitive predictors of relapse found that long-term episodic memory and higher-order EF (including problem-solving, planning, and decision-making) predicted alcohol relapse, whereas attention and higher-order EF predicted stimulant relapse, while only higher-order EF predicted opioid relapse (8). Working memory and response inhibition have also been associated with increased risk of relapse among cannabis and stimulant users (8, 17, 18). Additionally, variation in response inhibition has been shown to predict poorer recovery of quality of life during SUD treatment (19). Therefore, consistent evidence suggests that processing speed, attention, and reasoning are critical targets for current SUD treatments, whereas higher-order EF and decision-making are critical for maintaining abstinence. Response inhibition deficits seem to be specifically associated with relapse prediction in cannabis and stimulant users and also predict quality of life (a key non-drug-related clinical outcome) (20).

Practical Considerations: Characteristics and Needs of the SUD Treatment Workforce

The workforce in the SUD specialist treatment sector is diverse, encompassing medical specialists, allied health professionals, generalist health workers, and peer and volunteer workers (21). For instance, in the Australian context, multiple workforce surveys over the past decade suggest that around half the workforce have attained a tertiary level Bachelor (undergraduate) degree or greater (21–24). Similarly, US and European data has shown that education qualifications in the SUD workforce are lower than in other health services (25). Because the administration and interpretation of many cognitive tests are restricted to individuals with specialist qualifications, this limits their adoption in the sector. In addition, when screening does occur in SUD treatment settings, its primary function is to identify individuals requiring referral to specialist service providers (i.e., neuropsychology, neurology, etc.) for more comprehensive assessment and intervention, rather than to inform individual treatment plans.

Two fields in particular have driven progress in cognitive assessment practice for generalist workers: dementia, with an increasing emphasis on screening in primary care (26, 27), and schizophrenia, where cognitive impairment is an established predictor of functional outcome (28) necessitating the development of a standardized assessment battery specifically for this disorder. In the selection of domain-specific tests for the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) standard battery, a particular emphasis was placed on test practicality and tolerability, as well as psychometric quality. Pragmatic issues of administration time, scoring time and complexity, and test difficulty and unpleasantness (such as item repetition) for the client should be considered (28). These domains and issues are particularly relevant for the SUD workforce as well. The dementia screening literature has also emphasized these pragmatic issues, leading to a greater awareness and access to general cognitive screening tools.

Routine Cognitive Assessments in Clinical Practice

To date, the majority of the published literature on routine cognitive screening in SUD contexts has focused on three tests commonly used in dementia screening (29–34): the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (35), Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE) (36), and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (37). Due to their development for application in dementia contexts, these screening tools placed a heavy emphasis on memory, attention, language and visuospatial functioning (34). Multiple studies have demonstrated superior sensitivity of the MoCA and the ACE scales compared to the MMSE (34, 38). It is possible that this arises from the MoCA and ACE including at least some items assessing EF (letter fluency and trails) which are absent in the MMSE. Indeed, this may demonstrate an important limitation of adopting existing screening tools designed for dementia in the context of SUD treatment. It can be argued that cognitive screening is most beneficial in SUD contexts when focused on SUD-relevant domains, rather than the identification of general cognitive deficits. Therefore, current neuroscience-based frameworks emphasise the importance of assessing EF, incentive salience, and decision-making in SUD (13, 28, 39, 40). As such, there is much to be gained by applying a process similar to the MATRICS effort (28, 39, 40) in the SUD field to identify a ‘gold-standard’ set of practical and sensitive cognitive tests that can be routinely used in clinical practice.

Cognitive Assessment Approaches in SUD Research

The most commonly used cognitive assessment approach in SUD research has been the "flexible test battery". This approach combines different types of tests to measure selected cognitive domains (e.g., attention, EF). Attention, memory, EF, and decision-making are the most commonly assessed domains, although there is a considerable discrepancy in the tests selected to assess these constructs (41). Even within specific tests, different studies have used several different versions; for example, at least four different versions of the Stroop test have been employed in the SUD literature (1). Another commonly used approach is the "fixed test battery", which involves a comprehensive suite of tests that have been jointly standardized and provide a general profile of cognitive impairment. The Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) (42), the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) (43), the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) – Screening Module (44) and the MicroCog™ (45) are examples of fixed test batteries utilized in SUD research (30, 46–48), although these too have limited assessment of EF. Another limitation of these assessment modules is the lack of construct validity, as they were not originally designed to measure SUD-related cognitive deficits. As a result, they overemphasize assessment of cognitive domains that are relatively irrelevant in the context of SUD and neglect other domains that are pivotal (e.g., decision-making). A common limitation of flexible and fixed batteries is their reliance on face-to-face testing, normally involving a researcher or clinician, and their duration, which is typically around 60-90 min.

To address this gap, a number of semi-automated tests of cognitive performance have been developed, including the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (ANAM, developed by the U.S. Department of Defence), Immediate Post-concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing battery (ImPACT), and CogState brief battery, have been used more widely, although validation studies to date suggest they may not yet have sufficient psychometric evidence to support clinical use (49–53). Research specifically in addictions has begun to develop and validate cognitive tests that can be delivered in client/participants’ homes or via smartphone devices (54) (scienceofbehaviorchange.org, 2019). Evaluations of the reliability, validity, and feasibility of mobile cognitive assessment in individuals with SUD have been scarce, but promising (55–57).

Cognitive assessment via smartphone applications and web-based computing is a rapidly developing field, following many of the procedures and traditions of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) (56). The flexibility and rapidity of assessment offered by mobile applications makes it particularly suited to questions assessing change in cognitive performance over various time scales (within hours to over months). For example, cognitive performance can be assessed in event-based (i.e., participants-initiated assessment entries), time-based and randomly prompted procedures that were not previously feasible, and or valid, in laboratory testing. While the benefits of mobile testing to longitudinal research, particularly large-scale clinical trials, appear obvious (57), the rapidity and frequency of deployment also provide opportunities to test questions of much shorter delays between drug use behavior and cognition. For example, recent studies have examined if daily within-individual variability in cognitive performance, principally response inhibition, was associated with variable likelihood for binge alcohol consumption (58). Similarly, influencing the immediate dynamic relationship between cognition and drug use has also been used for intervention purposes. Web and smartphone platforms have been used to administer cognitive-task based interventions, such as cognitive bias modification (CBM) training (59–61), where cognitive performance is routinely measured as a central element of interventions that span several weeks. The outcomes of these trials show that mobile cognitive-task based interventions are feasible but not efficacious as in a stand-alone context (58, 61). However, the combination of cognitive bias modification (approach bias re-training) and normative feedback significantly reduces weekly alcohol consumption in excessive drinkers (59).

Summary of Evidence and Future Directions

A substantial proportion of people with SUD have cognitive deficits. Alcohol, stimulants and opioid users have overlapping deficits in EF and decision-making. Alcohol users have additional deficits in learning and memory and psychomotor speed. Heavy cannabis users have specific deficits in episodic memory and attention. Cognitive assessments of speed/attention, EF and decision-making are meaningfully associated with addiction treatment outcomes such as treatment retention, relapse and quality of life (1). In addition, there is growing evidence that motivational and affective domains are also implicated in SUD pathophysiology and clinical symptoms (8). For example, both reward expectancy and valuation and negative affect have been proposed to explain SUD chronicity (13). However, to date, there have been no studies linking these "novel domains" with clinical outcomes. Thus, it is important to explore the predictive validity of non-traditional cognitive-motivational and cognitive-affective domains in relation to treatment response. While flexible and fixed test batteries are the most common assessment approaches, data comparability is alarmingly low and future studies should aim to apply harmonized methods (41). Remote monitoring and mobile cognitive assessment remain in a nascent stage for SUD research and clinical care. It is too early to make accurate cost-benefit assessments of different mobile methodologies. Yet, their potential to provide more cost-effective assessment with larger and more representative samples and in greater proximity to drug use behavior justifies continued investment into their development.

Challenges for Implementation Into Practice

One of the main challenges for the cognitive assessment of people with SUD is the disparity of tests applied across sites and studies, and the lack of a common ontology and harmonized assessment approach (13, 62). Furthermore, harmonization efforts must accommodate clinicians’ needs, including brevity, simplicity, and automated scoring and interpretation (10). Mobile cognitive testing is a highly promising approach, although its reliability and validity are influenced by a number of key factors. Test compliance, or lack thereof, seems to be problematic. A recent meta-analysis suggested that the compliance rate for EMA (the standard paradigm to administer mobile cognitive testing) with SUD samples was below the recommended rate of 80% (63). Designs including participant-initiated event-based assessments were associated with test compliance issues, whereas duration and frequency of assessment were not. While the latter finding suggests that extensive cognitive assessment may be feasible with mobile methods, caution is advised with regard to the scope and depth of the data that can be obtained with these brief assessments and the validity of data sets collected (64). Remote methods for assessing confounds such as task distraction, malingering, and "cheating" are not well established or validated. As the capability of smartphones, for example, increases, so will the potential to minimize or control for such variables. Face-recognition and fingerprint technology has been proposed for ensuring identity compliance, although this presents ethical issues regarding confidential and de-identified data collection from samples that engage in illicit drug use (65).

ISAM-NIG Recommendations for Cognitive Assessment

As the authors of this ISAM-NIG roadmap, we give the following recommendations for future work:

Selecting theoretically and clinically relevant constructs: We recommend prioritizing constructs that are theoretically implicated in current neurobiological models of SUD [reviewed in (66)] and meaningfully related to SUD treatment response and clinical outcomes [e.g., (1, 67, 68)]. These include attention/processing speed, response inhibition, and higher-order EF/decision-making. Episodic and working memory assessments can be particularly indicated in the case of alcohol and cannabis users (8).

Selecting measures with well-established clinical validity in the SUD population: We recommend using measures with demonstrated predictive and ecological validity (i.e., their scores predict individual variation in meaningful clinical outcomes such as treatment response, craving, drug use/relapse, and quality of life), in addition to reliability. Unfortunately, few such measures are currently available. The MicroCog test battery and Continuous Performance Test (sustained attention/response inhibition) are highly reliable and excellent predictors of treatment response (1). Delay discounting paradigms and gambling tasks have excellent predictive and ecological validity, but the latter have been criticized for low reliability and construct validity (69). Because the ultimate goal is to incorporate cognitive assessment into clinical practice, we recommend conducting a Delphi consensus study including both cognitive assessment researchers and SUD clinicians to identify a minimum battery of measures with adequate psychometric properties AND clinical significance.

Adopting harmonized cognitive assessment protocols: We recommend continuing work towards developing a harmonized Cognitive Assessment of Addiction (CAA) battery. This battery should be (1) theoretically grounded in current addiction neuroscience frameworks; (2) brief and easy to administer, to meet the needs and qualifications of the SUD workforce; (3) portable and repeatable, capitalizing when possible on emerging remote monitoring techniques; (4) clinically meaningful in individual-level predictive models, i.e., able to identify risk of cognition-related premature treatment cessation or relapse, cognitive phenotypes relevant for predicting response to different treatment approaches, or changes in cognitive status relevant to treatment progression. The CAA should also address challenges specific to international research collaboration, including culturally-sensitive contents and appropriate translation of instructions.

Neuroimaging

The development of functional imaging techniques such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), has allowed the high-resolution mapping of the brain in-vivo, in people with SUD. This body of work has provided increasing evidence that SUD is associated with alterations in the anatomy and the functional brain pathways ascribed to reward, learning, and EF. Importantly, emerging evidence suggests that neuroimaging versus subjective measures in SUD may predict with greater precision addiction-relevant cognitive processes (e.g., attentional biases) and treatment outcomes (e.g., abstinence) (70–72).

Neuroimaging Methods and Techniques Applied to SUD

Functional imaging techniques allowed exploration of whether brain dysfunction is implicated in SUD in humans. These create images of brain function by relying on proxies, including metabolic properties of the brain (e.g., oxygen in PET and fMRI, glucose levels in PET) (73). The application of functional imaging has been crucial to reveal the impact of SUD on human brain function in areas ascribed to cognitive processes (e.g., EF, decision-making) and positive and negative emotions (see "Cognitive assessment approaches in SUD research" in the COGNITIVE ASSESSMENT section).

PET studies have also provided early evidence on the neurobiology of SUD (74–77). PET imaging relies on the movement of injected radioactive material to identify whether the metabolic activity of brain regions is related to cognitive functions (73). PET’s invasiveness and high financial costs have resulted in a limited number of studies using it, and its low temporal and spatial resolutions (i.e., 20–40 min required for image generation, with a spatial resolution up to 5 mm3) prevented the identification of subtle brain activity alterations in SUD samples (73).

The development of fMRI provided a way to overcome these limitations. Unlike PET, fMRI is non-invasive, promoting feasibility in unpacking the neural correlates of SUD (73). Specifically, fMRI generates information about brain activity by exploiting the magnetic properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood (73). Further, fMRI provides information on the brain’s functional activity with higher temporal and spatial resolutions than those of PET, i.e., within seconds and millimeters, respectively (73). These methodological advantages have allowed many studies to map the neural pathways implicated in SUD, while providing information on brain function within a high spatial and temporal resolution. However, a well-described limitation of fMRI analyses is the difficulty to control for multiple tests (i.e., statistical thresholds) and related false positive errors (78). The neuroimaging community has started to implement several strategies to address this limitation (79), but the use of liberal thresholds has probably inflated false positive rates in earlier studies.

Using multi-modal imaging techniques is warranted to further unpack the neural mechanisms of SUD and abstinence. For instance, integrating structural MRI (sMRI) data with Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Imaging, an MRI imaging technique that allows investigation of metabolites in the brain, may provide insight into the biochemical changes associated with volumetric alterations in SUD. Further, conducting brief, repeated task-free fMRI studies during treatment/abstinence could provide a better understanding of the impact of clinical changes on intrinsic brain architecture. An advantage of resting-state functional imaging data is the possibility of investigating patterns of brain function without restrictive "forces" on brain function placed by a specific task. Finally, studying SUD with modalities such as Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) may reveal alteration in white matter pathways that connect brain regions that are volumetrically altered. This approach may inform the pathophysiology of volumetric alterations in SUD-relevant brain circuits.

Brain Systems Implicated in Addiction: Insights From Theory

Table 1 overviews key neurobehavioral pathways implicated by prominent neuroscientific theories of addiction and a growing body of work. These include neurobehavioral systems implicated in positive valence, negative valence, interoception, and EF (80–86). Abstinence may recover and mitigate such brain alterations and related cognitive functions, e.g., increase in response inhibition capacity, lower stress and drug reactivity, learning new responses to drugs and related stimuli. This notion is yet to be tested using robust neuroimaging methods that, in conjunction with treatment-relevant clinical and cognitive measures, measure and track the integrity of specific neural pathways during abstinence (see examples in Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Overview of addiction-related neurocognitive constructs and related brain circuits, tasks, and interventions.

| Positive affect, Response (13), (80), (82), (84) | Positive affect, Anticipation (13), (83), (84) | Negative affect (13), (80), (82), | Learning/habit (13), (83), (84) | Cognitive control (13), (82), (83), (84) | Interoception (83), (86) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain circuit | Medial OFC, ventral striatum | Medial OFC, sgACC (subgenual) | Amygdala | Lateral OFC, Dorsal striatum (Caudate, putamen), Hippocampus | DLPFC, dACC (dorsal), IFG | Insula, posterior cingulate |

| fMRI tasks | Monetary incentive delay (reward receipt) (87), probabilistic reward task (88), activity incentive Delay task (98) | Monetary Incentive delay (reward anticipation) (87), cue-reactivity (90), attentional bias (89) | Cue reactivity (90) during withdrawal, negative or stress cue reactivity | Instrumental reward-gain and loss-avoidance task (89) | Stop Signal (91), Go-no go (92), Stroop (93), PASAT-M (97) | heartbeat counting task (94), visceral interoceptive attention task (95) |

| Cognitive | Reward receipt, response to reward, reward satiation | Motivation, saliency valuation, reward anticipation, drive expectancy, approach/attentional bias | Acute/sustained threat | Stimulus-response conditioned habits, compulsivity, learning reward/loss contingencies | Loss of cognitive control, disinhibition, performance monitoring, action/response selection, low distress tolerance | "Momentary mapping of the body’s internal landscape" (96) during craving and withdrawal |

| Behavior | Experience of reward with drug use, response to substance-free reward | Increased: attention/salience of drugs and related stimuli, reward when anticipating drug use. | Experience of withdrawal, stress, anxiety, anhedonia | Drug use as: repetitive, compulsive drive, conditioned response to seek positive affect & avoid/mitigate negative affect, learnt association with people, situations, places | Drug use even when known as harmful and in response to affective distress | Heightened/lowered awareness to drug-related physical & psychological states; increase distance between cue and behavioral response. |

| Intervention strategies | Decrease reward value of drug (e.g., methadone or nicotine patches), suppression of mPFC with low frequency rTMS or cTBS; increase reward value of drug-free activities (e.g., behavioral activation, physical activity) | Cognitive bias modification, reappraisal training for drug cues, exposure therapy, motivational interviewing, contingency management | Strategies to address negative affect (e.g., behavioral activation and cognitive reappraisal training), medication that counter stress response, rtfMRI neurofeedback on Insula or sgACC | Strategies that weaken conditioned drug behaviors, memory reconsolidation | Strengthen inhibitory/executive control, inhibitory control training (e.g., Go-No-Go), working memory training, goal management training, stimulating DLPFC with anodal tDCS or high frequency rTMS | Mindfulness-based therapies, physical exercise |

Columns reflect key neurocognitive constructs for addiction research. Identified constructs also map onto the three domains of the Addiction Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) (11) framework: Positive affect (response and anticipation), Negative affect, and Cognitive control map directly onto the three domains of ANA (i.e., Incentive salience, Negative affectivity and Executive function). Learning/habit is part of Incentive salience (reward learning); Interoception is at the interface of the three ANA domains. Rows reflect functional neuroimaging methods (e.g., fMRI tasks), cognitive/behavioral assessments, and examples of neuroscience informed intervention strategies aligned with each of the identified constructs.

ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; cTBS, continuous theta burst stimulation; DLPFC, dorsolateral PFC; IFG, Inferior Frontal Gyrus; mPFC, medial PFC; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex; rtfMRI, real-time functional MRI; rTMS, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

The neurobiology of abstinence has been posited to entail two core processes (99). The first is the restored integrity of brain function, as drug levels in the central nervous system and bloodstream clear out with abstinence. The second is the retraining of neural pathways implicated in cognitive changes that enable abstinence. These include awareness/monitoring of internal psychological/physiological states (e.g., insula), withdrawal and craving (e.g., amygdala); EF (e.g., dorsal prefrontal regions); monitoring conflict between short-term goals (e.g., pleasure from using drugs, ventral striatum) versus long-term goals (e.g., abstinence and improved quality of life; anterior cingulate cortex); motivation to use drugs (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex); and learning new responses to drug-related and other stimuli (e.g., lateral prefrontal and dorsal striatal regions) (99).

Summary of Neuroimaging Evidence in SUD

Most neuroimaging studies to date have mapped dysfunctional neural pathways in SUD. There is a significant lack of work that tracks abstinence-related brain changes over time. This evidence gap prevents neuroimaging studies from informing the identification of treatment targets and clinical practice. It is unclear if abstinence (i) leads to recovery of SUD-related brain dysfunction (i.e., return to pre-drug onset level, or comparable levels to non-drug using controls), (ii) engages additional pathways implicated in abstinence-related cognitive, clinical, and behavioral changes, and (iii) is predicted by specific brain measures assessed pre-treatment. Emerging (but mixed) evidence from standard behavioral (e.g., CBT, Motivational Interview, Contingency Management) and pharmacological treatments that directly affect the central nervous system provides preliminary support for these notions, as reviewed in detail in previous work [see (100–102)]. This section provides an overview of early neuroimaging evidence for brain changes related to abstinence and novel interventions (i.e., cognitive training approaches and mindfulness-based therapies).

Neuroimaging Evidence in Abstinence

Abstinence may "reverse" brain dysfunction and volume loss associated with SUD. Studies have observed increased or normalized volumes in global and prefrontal brain regions related to abstinence in people with alcohol use disorder (103) and cocaine and opiate use disorders (104). PET and DTI studies of alcohol and cocaine users showed recovery of brain dysfunction and white matter integrity following heterogeneous abstinence durations, e.g., from about a month (105, 106), to several months (107, 108) and several years (109, 110). Results from fMRI tasks of response inhibition in abstinent users also showed that reduced brain function typically associated with drug use, was "restored" and increased in prefrontal and cerebellar pathways in former versus current cigarette smokers (> 12 month abstinent) (111, 112), and in former cannabis users (> 28 day abstinent) versus non-users (113).

Emerging (but mixed) evidence showed that abstinence duration was associated with improved integrity (functional and structure) of cortical and prefrontal pathways (109, 111, 114). Additionally, abstinence related neuroadaptations have been associated with substance use levels [e.g., cocaine dose (115)], and performance was improved during cognitive tasks relevant to addiction [e.g., processing speed, memory, EF-shifting (104, 115)]. Thus, abstinence-related brain changes may in part drive treatment relevant outcomes.

Neuroimaging Predictors of Abstinence

Several neuroimaging studies have examined whether (structural and functional) brain integrity in SUD predicts abstinence, with promising results. Studies of brain structure in people with nicotine and alcohol use disorders reported that increased volume and white matter integrity in prefrontal regions, followed by parietal and subcortical areas, most consistently segregated abstainers versus relapsers (116–119). Studies have examined brain function using fMRI tasks that engage cognitive domains relevant to treatment response (cue reactivity, attentional bias, error-related activity, reward, and emotion processing) (71, 72, 111, 116, 117, 120–124). These studies provided evidence that the function of fronto-striatal regions in particular, followed by other regions (e.g., cingulate, temporal, insular cortices) discriminated responders versus non-responders, relapsers versus non-relapsers in cigarette smokers and people with methamphetamine, cocaine and alcohol use disorders (71, 72, 111, 116, 117, 120, 121, 123, 124). Also, the activity of fronto-striatal pathways have been shown to predict alcohol dosage at 6 month follow-up (122). Studies that used other functional imaging techniques such as spectroscopy and PET imaging consistently reported that frontal blood flow and metabolites (i.e., in prefrontal, insular, and cerebellar areas) and the density of dopamine receptors (i.e., in the dorsal striatum) predicted treatment outcome in alcohol users (125, 126) and relapse in methamphetamine users (127).

Impact of Cognitive Training Strategies

Novel training strategies that target core cognitive dysfunctions in SUD have shown promise to restore cognitive alterations and help maintain abstinence (128). One example includes cognitive bias modification strategies that reduce attentional biases towards substance related cues [see study in tobacco smokers (129)]. Such strategies may target top-down and bottom-up brain pathways (130) implicated in addiction (131). These include increasing the activity of top-down EF regions that enhance inhibitory control and behavioral monitoring (e.g., dorsal anterior cingulate, lateral orbitofrontal cortex), and decreasing reactivity of bottom-up pathways implicated in reactivity to drug stimuli, and craving (e.g., amygdala).

Early neuroimaging evidence has examined the neuroadaptations that occur pre-to-post-cognitive bias modification training. These findings are revised and discussed in the COGNITIVE TRAINING AND REMEDIATION section below. There is a paucity of neuroimaging research on other cognitive training and remediation approaches, despite promising evidence of neuroplasticity-related changes after cognitive remediation in brain injury (132).

Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness-based interventions are being increasingly used for the treatment of SUD (133). Although mindfulness does not use standard cognitive training/remediation approaches, it has shown to improve SUD-relevant cognitive processes such as attention and EF (134) as well as substance use outcomes (i.e., reduced craving, withdrawal) (135). Mindfulness-based interventions engage two key cognitive processes (i) focused attention, which consists of paying attention to a specific stimulus while letting go of distractions (e.g., focus on breathing, while experiencing craving) and (ii) open monitoring, which refers to the being aware of internal and external stimuli (e.g., acknowledging the experience of stress, craving, and withdrawal, or environmental triggers) with a non-judgmental attitude and acceptance.

The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions has been ascribed to improved function of prefrontal, parietal, and insula regions that are implicated in EF and autonomic regulation (133, 136), and down-regulation of reactivity in striatal/amygdala regions implicated in reward, stress, and habitual substance use (136). Only a handful of neuroimaging studies have examined brain changes that occur with mindfulness-based interventions in SUD. This includes a fMRI study in tobacco smokers that showed a 10-session mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (MORE) versus placebo intervention, decreased activity of the ventral striatum, and medial prefrontal regions during a craving task and an emotion regulation task (137). Most evidence on mindfulness and SUD consists of behavioral studies that showed robust effects on cognition, substance use, and craving. Given the widespread use of mindfulness-based interventions in clinical settings, we advocate the conduct of active placebo-controlled neuroimaging studies that map the neurobiology of mindfulness in SUD.

Challenges for Implementation Into Practice

Overall, there is a paucity of neuroimaging studies of treatment and abstinence in SUD. The study methods are very heterogeneous which precludes their systematic integration. First, there was significant heterogeneity in treatments, with distinct durations and hypothesized neurobehavioral and pharmacological mechanisms of action, and distinct treatment responses across different individuals, SUD and related psychiatric comorbidities. Second, control groups varied substantially (e.g., placebo, active control treatment, no control group) and brain changes related to abstinence were compared to different types of controls (e.g., pretreatment baseline in the same group, control group of non-substance users, separate SUD group also assessed post-treatment). Third, repeated measures study designs had varying data testing points (e.g., before, during and at varying times post-treatment) that precluded the integration of the study findings and mapping treatment-related, trajectories of brain changes with abstinence/recovery. More systematic evidence is needed to provide sufficient power to measure brain pathways relevant to treatment response and to inform clinically-relevant treatment endpoints. In order to address this gap, the ISAM-NIG Neuroimaging stream recommends the conduct of harmonized, multi-site, neuroimaging studies with systematic testing protocols of relevance for clinical practice. It is hoped that the ISAM-NIG Neuroimaging approach will generate results that can be readily integrated and that increase the power to detect abstinence-related neuroadaptations.

On one hand, the integration of neuroimaging testing into clinical practice can be challenging. MRI scanners are extremely expensive to buy, setup, and run safely, and the acquisition of high-quality brain images requires extensive specialized technical expertise. On the other hand, the availability of MRI scans in many hospitals, universities, and medical institutions, may provide ideal settings to integrate neuroimaging and clinical expertise. MRI scans can be feasible in that they are non-invasive, safe, and can be relatively quick (e.g., anatomical and resting-state brain scans can take <10 min, and some fMRI tasks can last between 10 and 15 min). Outstanding challenges to address remain funding sources, the lack of integration in the theoretical frameworks between basic research, clinical science, and clinical practice. Discipline-specific specialized language and practices can also create barriers. We advocate using team science to develop a harmonized interdisciplinary framework, so that all stakeholders, including clinicians, neuropsychologists, social workers and neuroscientists interact to inform commonly-agreed testing batteries and most profitable directions for future work.

The present review has focused on neuroimaging data mainly acquired through fMRI, allowing for visualization of the brain networks involved in certain conditions (e.g., abstinence vs. relapse). However, it should be noted that the coarse temporal resolution of such techniques (1–2 s) impedes determination of the temporal activation sequence (in the order of the ms), allowing the specific brain activation patterns to be correlated with the various cognitive stages involved in the investigated processes [e.g., (138)]. Other tools, such as cognitive event-related potentials (ERPs) in particular, might be more suitable for this purpose (139). Nowadays, different studies reveal that specific ERP components tagging specific cognitive functions (mainly cue reactivity and inhibition) may be used as neurophysiological biomarkers for addiction treatment outcome prediction (140). Such data may be of great value to clinicians for the identification of cognitive processes that should be rehabilitated on a patient-by-patient basis through cognitive training and/or brain stimulation. However, despite technical facilities (cheap tool easily implementable in each clinical care unit), several decades of research, and clinical relevance, ERPs like other neuroimaging modalities have yet to be implemented in the clinical management of SUD.

ISAM NIG Recommendations for Neuroimaging

We aim to map how advanced multimodal neuroimaging tools—coordinated with relevant clinical and cognitive measures agreed upon with a large multidisciplinary team of experts in the field—can be used to track the neurobiological mechanisms of addiction treatment. As the authors of this ISAM-NIG roadmap, we give the following recommendations for future work:

Neuroimaging testing should be harmonized with clinical and cognitive tools mapping overlapping systems (see example in Table 1 ).

Neuroimaging testing should be feasible and rely on short and robust imaging protocols that recruit specific brain pathways implicated in relevant clinical and cognitive features of addiction (e.g., craving, attentional bias, cognitive control).

Neuroimaging protocols may also incorporate neuroimaging measures of brain integrity other than those included in the harmonized protocols when focused on discovery science (e.g., new fMRI tasks that target novel cognitive constructs, new neuroimaging techniques that test distinct properties of brain integrity). This would mitigate the risks that complete harmonization around existing neuroimaging measures and neurobiological models of addiction would stifle new knowledge. We cannot exclude that current neuroimaging techniques and theories of addiction may not be an accurate/valid representation of brain changes that occur with SUD treatment.

Imaging testing batteries should be amenable to repeated testing so that changes over time can be tracked (i) prospectively, to examine if baseline imaging measures predict follow up outcomes assessed 1+ times at the end of treatment, (ii) longitudinally, to track individual trajectories of brain and behavioral change before, during and after treatment, (iii) using rigorous double-blind randomized controlled studies to map treatment-specific effects in distinct substance and behavioral addictions.

Multi-site neuroimaging studies using shared protocols will be necessary to gain sufficient power to track heterogeneity of treatment responses between individuals SUD, to validate the protocols and test their reliability. There are excellent examples of successful international collaborations that are already in place in this area, such as ENIGMA-Addiction (141). We aim to leverage these existing collaboration initiatives to increase neuroimaging methods reliability and validity and studies sample size and representativity, and to expand them by incorporating more clinical researchers and clinicians.

As treatments often consist of individual and combined interventions, the distinct and cumulative effects on brain changes should be examined. In addition, investigating moderating roles of age and sex differences on these abstinence-related neuroadaptations is critical. Indeed, younger and older people with SUD may show lower and greater vulnerability to aberrant neurobiology (142). People with different ages and sex may show distinct neuroplastic changes with abstinence and these are largely unknown (99, 143, 144).

Brain indices from neuroimaging testing should be examined in relation to treatment response variables, whether measured as categories (e.g., responders vs. non-responders, relapsers vs. non-relapsers) or as discrete measures of addiction (severity of addiction symptom scores, number of relapses, duration of abstinence, amount of substance used) and related mental health, cognitive and quality of life outcomes (e.g., stress, mood, socio-occupational functioning).

Cognitive Training and Remediation

Despite recent advances in psychological and pharmacological interventions for SUD, relapse remains the norm. A recent meta-analysis of 21 treatment outcome studies conducted between 2000–2015 found that fewer than 10% of treatment seekers were in remission (i.e., did not meet SUD diagnostic criteria for the past 6 months) in any given year following SUD treatment (145). The past decade has seen a proliferation of cognitive training (CT) intervention trials aimed at remediating or reversing substance-related cognitive deficits (146). However, their implementation into clinical practice is almost non-existent, despite promising results and now having more flexible, precise, engaging and convenient modes of delivery (i.e., computer, web and mobile application-based approaches). Gathering more data in this still-developing area is essential to facilitate translation. Even the most widely tested training interventions, such as cognitive bias modification, need more data to fully appraise their benefit for addiction treatment (147). This section summarizes recent advances in CT, identifies limitations in the evidence base, and highlights priorities and directions for future research to bridge the gap between science and practice. Current CT approaches can be broadly divided into: general cognitive remediation, working memory training (WMT), inhibitory control (or response inhibition) training (ICT), and cognitive bias modification (CBM).

Cognitive Remediation

In SUD, general cognitive remediation approaches such as cognitive enhancement therapy (CET) and cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) aim to reduce substance use (148–150) and craving (151) by targeting EF and self-regulation. Cognitive remediation has been shown to improve cognition in domains of working memory (WM), verbal memory, verbal learning, attention, and processing speed (151–154). Positive outcomes have also been shown to be associated with increased neuroplasticity in emotion regulation-related fronto-limbic networks in individuals with schizophrenia and co-morbid SUD (155). A recent study delivered 12 two-hour group sessions of clinician-guided CRT and computerized CT (Lumosity) (156) over 4 weeks to a sample of female residents completing residential rehabilitation and found significant improvements in EF, response inhibition, self-control, and quality of life relative to treatment as usual (TAU) (157). Similar research has reported comparable improvements in cognitive functioning following CRT (150, 151) and CET (148), and improved cognitive functioning has been associated with reduced substance use at 3- and 6-month follow-ups (148, 150). Importantly, CET and CRT also demonstrate preliminary efficacy for SUD patients with cognitive impairments (e.g., schizophrenia, past head injury) (148, 157). However, their duration, intensity, and high cognitive demand—coupled with a current paucity of large-scale, methodologically rigorous clinical trials—may currently preclude their widespread implementation in clinical settings.

Another manualized therapist-assisted group intervention is Goal Management Training (GMT), which trains EF and sustained attention and emphasizes the transfer of these skills to goal-related tasks and projects in everyday life. When combined with mindfulness meditation, GMT has been found to significantly improve WM, response inhibition and decision-making in alcohol and stimulant outpatients relative to TAU (158) and more recently also in polysubstance users in a therapeutic community (159). A meta-analysis of GMT more broadly concluded that it provides small to moderate improvements in EF which are consistently maintained at 1–6 month follow-ups (160). As such, GMT is likely to be an effective candidate cognitive remediation approach for SUD treatment; however, substantially more research is needed to validate this assertion, particularly regarding the translation of cognitive improvements into improved substance use outcomes.

Working Memory Training (WMT)

The most widely researched EF training intervention, WMT (e.g., Cogmed, PSSCogRehab) (161, 162) requires participants to repeatedly manipulate and recall sequences of shapes and numbers through computerized tasks that become increasingly difficult over time (i.e., they are adaptive to the individual’s performance). WMT aims to extend WM capacity, so individuals can better integrate, manipulate, and prioritize important information, with the aim of supporting more adaptive decision-making that leads to reduced substance use (163). Relative to many other approaches, WMT is intensive, typically requiring 19–25 days of training and as such, retention is often poor (164). While WMT has been shown to lead to improvements in near-transfer effects (i.e., improved performance on similar WM tasks), there is limited evidence supporting far-transfer effects of WMT on other measures of EF and importantly, on substance-related outcomes (165). Reduced alcohol consumption 1 month after training was reported following WMT in heavy drinkers (163), but most studies have failed to demonstrate or even measure changes in substance use (165). For example, non-treatment seekers with alcohol use disorder who were trained with Cogmed showed improved verbal memory but no clinically significant reductions in alcohol consumption or problem severity (166). While a study of treatment-seekers improved WM and capacity to plan for the future (i.e., episodic future thinking) on a delay discounting task, there was no measurement of substance use outcomes (167). Similarly, studies of methadone maintenance (168) and cannabis (169) have found no evidence of far-transfer effects (e.g., delay discounting), although Rass et al. (168) showed WMT-related reductions in street drug use among methadone users. Other forms of WMT (e.g., n-back training) have reported similar near-transfer but not substance-use-related findings with methamphetamine patients (170) and a mixed group of substance use patients (alcohol, cannabis, cocaine) (164). As such, the greatest limitation in the WMT literature is the failure to consistently examine substance use outcomes and therefore there is insufficient evidence at this time to support the utility of WMT as an effective adjunctive treatment for SUD.

Inhibitory Control Training (ICT)

Since deficits in inhibitory control are associated with increased drug use (171–174), ICT aims to bolster inhibitory control through the repeated practice of tasks [e.g., go/no-go (GNG), stop-signal task]. Such tasks require individuals to repeatedly inhibit prepotent motor responses to salient stimuli (172). In a seminal study, a beer-GNG task which trained heavily drinking students to inhibit responses to "beer" stimuli resulted in significantly reduced weekly alcohol intake relative to students trained towards "beer" stimuli (175). A recent RCT of 120 heavily drinking students found that a single session of either ICT or approach bias modification (ApBM, described below) led to significant reductions in alcohol consumption relative to matched controls (176). Similarly, Kilwein et al. (177) found that a single session of ICT (GNG) reduced alcohol consumption and alcohol approach tendencies in a small sample (n = 23) of heavily drinking men (177). Despite these promising findings, each of the aforementioned ICT studies used community samples, and it has not yet been established whether these results will generalise to treatment seekers.

Two meta-analyses recently concluded that ICT leads to small but robust reductions in alcohol consumption immediately after training (178, 179). Di Lemma and Field (176) reported reduced alcohol consumption in a bogus taste test after a single session of ICT or cue-avoidance training (approach bias modification). Others have observed reduced alcohol consumption 1 and 2 weeks after ICT (163, 177, 180). These findings highlight the promise of ICT though there remains a paucity of research assessing long-term drinking outcomes outside of laboratory settings. Future studies of ICT with clinical populations should consider testing multi-session approaches akin to WMT. To date, few studies have trialled multi-session ICT: One found it to be ineffective (58) for heavily drinking individuals, while another found that 2 weeks of ICT resulted in modest reductions of alcohol consumption among individuals with AUDs, compared to WMT or a control condition (181).

Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM)

CBM aims to directly interrupt and modify automatic processes in response to appetitive cues. Attentional bias modification (AtBM) aims to modify the preferential allocation of attentional resources to drug cues by repeatedly shifting attention to neutral or positive (non-drug) cues and away from drug-related cues. Despite several null findings (182), significant effects have included the reduction of alcohol consumption in non-treatment seeking heavy or social drinkers (183, 184). Among treatment seekers, five sessions of AtBM have been shown to significantly delay time to relapse (but not relapse rates) relative to controls who received sham training (185). Similarly, six sessions significantly reduced alcohol relapse rates at a one-year follow-up relative to a sham training condition in a sample of treatment seekers with AUD (186). Among methadone maintenance patients, AtBM reduced attentional bias to heroin-related words, temptations to use, and number of lapses relative to TAU (187). However, among individuals with cocaine use disorder, it failed to reduce attentional bias, craving, and cocaine use (188). Likewise, 12 sessions of AtBM vs. sham training during residential treatment for methamphetamine use disorder failed to reduce craving and preferences for methamphetamine images (189). A systematic review of alcohol, nicotine, and opioid AtBM studies concluded that despite numerous negative findings in the literature, eight out of 10 multiple-session studies resulted in reduced addiction symptoms (particularly for alcohol), but without concomitant reductions in attentional bias (190).

Approach bias modification (ApBM), which uses the Approach Avoidance Task, requires an avoidance response to drug cues (pushing a joystick, shrinking image size) and an approach response (pulling a joystick, enlarging image size) to non-drug cues. Several trials have examined alcohol ApBM, with evidence that short-term abstinence is increased by up to 30% with four consecutive training sessions during inpatient withdrawal (32) and by 8%–13% at 12-month follow-up (186, 191, 192). Alcohol ApBM has demonstrated relatively consistent, moderate reductions in drinking behavior when delivered to clinical populations (193), and it was even added to the German guidelines for the treatment of AUD (194).

Early neuroimaging evidence has examined the neuroadaptations that occur pre-to-post-cognitive bias modification training. This work has focused on two samples of abstinent alcoholics undergoing an fMRI cue-reactivity task (alcohol versus soft drink stimuli) (61, 195). Participants showed higher baseline reactivity to alcohol cues within the amygdala/nucleus accumbens and the medial prefrontal cortex, respectively (61, 195). The same samples, following a 3-week implicit avoidance task (versus placebo), showed reduced amygdala and medial prefrontal reactivity (61, 195). Notably, these brain changes were associated with reduced craving and approach bias to alcohol stimuli (61, 195) but not abstinence 12 months later. While preliminary, these findings suggest that neuroadaptations associated with cognitive bias modification have clinical relevance and warrant replication in larger SUD samples using robust, active placebo-controlled designs.

To date, only one study has been published that trialled ApBM in an illicit drug-using sample of non-treatment-seeking adults with cannabis use disorder (N = 33). Relative to sham-training, four sessions resulted in blunted cannabis cue-induced craving (196) but not less cannabis use. Overall, evidence suggests that ApBM is associated with reduced approach bias and reduced consumption behaviors for alcohol, smoking, and unhealthy foods (197). Recently, six sessions of ApBM delivered to 1,405 alcohol-dependent patients significantly reduced alcohol relapse rates at a 1-year follow-up relative to a sham-training condition (186). However, as these reductions were also observed following AtBM and a combined AtBM and ApBM condition, the authors concluded that all active CBM training conditions had a small but robust long-term effect on relapse rates.

Finally, a meta-analysis of alcohol and smoking CBM studies (both AtBM and ApBM) showed a small but significant effect on clinical outcomes for alcohol (but not smoking), but a lack of evidence that reduced approach bias led to improved outcomes (198). This assertion was challenged by Wiers et al. (193) who noted that the review conflated proof-of-principle lab-studies and clinical RCTs and different samples (e.g., treatment-seeking alcohol dependent individuals vs non-clinical student populations). Importantly, these populations likely have differences in motivation/awareness for receiving an intervention to reduce alcohol use, which could explain inconsistencies in the reported effectiveness of CBM across populations (193).

Summary of Evidence and Future Directions

Currently CBM, particularly ApBM, appears one of the most promising approaches for individuals seeking treatment for AUDs; however, its effectiveness for other drugs (aside from tobacco) is yet to be established. The most extensively trialled CT approach is WMT, which has shown promising results in alcohol and stimulants users. However, its high cognitive demand, training intensity, and apparent lack of far-transfer effects limit its application to clinical populations. ICT holds much promise for reducing alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers, but requires testing in treatment-seekers. Finally, more intensive group-based approaches such as CRT/CET and GMT may improve EF and quality of life; however, their impact on substance use outcomes remains largely untested. Synergistic approaches now warrant exploration. Indeed, a study that combined WMT and AtBM (199) has shown promising feasibility and improved EF, though substance use outcomes were not assessed. It may also prove fruitful to adopt staggered CT approaches, capitalizing on the brain,s capacity to repair itself (neuroplasticity) during withdrawal, early and later abstinence by strengthening cognitive control (e.g., using ICT) and dampening cue-reactivity (e.g., using CBM), prior to engaging in more intensive and cognitively demanding but ecologically valid group training for more extensive remediation (e.g., using GMT).

Challenges for Implementation Into Practice

While there may be logistical challenges to the adoption of CT in clinical practice (e.g., cost, lack of time, training requirements, etc.), the main impediment to implementing CT in clinical practice is the absence of robust evidence for treatment success of any one particular approach. This is largely due to the vast heterogeneity of studies, particularly regarding differences in treatment settings, samples (clinical vs. non-clinical populations), cognitive intervention approaches, number and duration of training sessions, targeted mechanisms, targeted drugs of concern and varying primary outcome measures. Similarly, the absence of brief, ecologically valid, easily-administered measures of cognition precludes the identification of candidates who are most likely to benefit from CT (e.g., individuals with the poorest WM or the strongest attentional bias). As such, the evidence base for CT remains hampered by (1) the marked lack of studies on clinical populations, (2) the counter-intuitive neglect of assessing relevant substance use outcomes, (3) the lack of adequately-powered RCTs, (4) the limitations of research designs, (5) lack of attention to individual-level trajectories of cognitive improvements in relation to substance use and quality of life outcomes (precision medicine approach), and (6) a simple focus on direct relations between cognitive deficits and outcomes without considering person and environmental mediators and moderators of this relation (14). Despite positive signals from proof-of-concept studies and pilot RCTs, they require replication and testing with suitable control conditions in order to demonstrate their applicability in clinical settings. These limitations highlight the need for a harmonization approach that promotes greater standardization in cognitive training protocols and assessment of its effectiveness (i.e., routine assessment of substance use outcomes). Since the software and manuals of some of the most promising interventions (e.g., CBM, GMT) are well-developed and reproducible, we should advance towards optimized shared protocols that can promote international collaborations and multi-site studies. These recommendations will elucidate what works, for whom and under what conditions (i.e., identifying neurocognitive phenotypes). This knowledge will then guide the adoption of CT to improve outcomes for people seeking treatment for SUD.

ISAM-NIG Recommendations for Cognitive Training and Remediation

As the authors of this ISAM-NIG roadmap, we give the following recommendations for future work:

The a priori publishing of research protocols: To improve the consistency of cognitive training trials we encourage the publishing of research methodologies and protocols. This will permit replication studies to aid the consolidation of a disparate evidence base and help determine the optimal training duration and frequency to be implemented in real world clinical settings.

Adopting consistent training paradigms and tailored, context-relevant stimuli: A challenge for CBM research is the absence of consensus on optimal sham training conditions (e.g., matched stimuli with different push-pull contingencies) and optimal approach stimuli (e.g., whether to use neutral stimuli or healthier alternatives such as non-alcoholic beverages) (200). In the context of both CBM and ICT, utilizing personalized/tailored stimuli may increase engagement and effectiveness. For avoidance or "no-go" stimuli this might involve only using beverage types/brands that are regularly consumed by an individual, or images of illicit drug use and paraphernalia reflecting their preferred route of administration. Similarly, approach or "go" stimuli could encompass positive motivational images representing an individual’s personal goals, values, and aspirations (family, employment, hobbies, etc.), which are drawn on heavily in most psychosocial interventions. Furthermore, co-design with consumers and end-users is a fundamental step to developing interventions that will be implemented successfully in practice.

Ensuring targeted constructs are measured in cognitive training trials: Future research protocols must adopt pre- and post-intervention measures that will elucidate changes in targeted mechanisms, thereby integrating neuroscience into addiction treatment. Importantly, these protocols should enable moderation and mediation analyses using psychophysiological measures (e.g., EEG, skin-conductance) in order to address issues regarding the notorious lack of reliability of traditional measures (e.g., the implicit association task and the approach avoidance task) (192, 201, 202) and thereby more accurately identify individuals most likely to benefit from adjunctive approaches.

Adopting and standardizing SUD-related outcome measurement: Future research needs to test cognitive interventions in real-world clinical settings and assess meaningful SUD clinical outcomes (i.e., reduced substance use, reduced cue-craving). Clear evidence of reduced harm and consumption is likely to appeal to both clinicians and individuals under their care, thus driving this improved addiction treatment effort.

Neuromodulation

The exponential growth in our understanding of the neural circuits involved in drug addiction over the last 20 years (3, 203–205) has been accompanied by the introduction of non-invasive brain stimulation technologies (NIBS) capable of modulating brain circuits externally (outside of the skull), such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial electrical stimulation (tES). Technical advances in NIBS has increased hopes to find clinical applications for NIBS in addiction medicine (206). New FDA approval of NIBS technologies in depressive and obsessive-compulsive disorders, which have overlapping brain circuits with SUD, has raised these expectations to a higher level. There are other emerging areas of NIBS for addiction medicine, such as focused ultrasound stimulation (FUS) and transcranial nerve stimulation (tNS). Furthermore, other technologies exist that target neural circuits noninvasively that can be classified as "neuromodulation", such as fMRI- or EEG-neurofeedback (NF), whereby individuals can change their own brain activity in real time using a brain-computer interface. However, this section will primarily focus on tES/TMS/NF. We will review potential targets, ideal scenarios, and complexities in the field of neuromodulation for addiction treatment and then conclude with a few recommendations for future research.

Potential Targets for Neuromodulation

Targets in the field of neuromodulation should be defined across multiple levels, from behavior, cognitive process, and neural circuit. The NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) have provided a research framework for mental health disorders that include these levels of targets for neuroscience-informed interventions including neuromodulation. While this framework was not specifically designed for addiction science, it is still a helpful resource. In RDoC terminologies, three main domains are more frequently considered for addiction medicine: positive valence, negative valence, and cognitive systems with a predominant focus on EF (13, 207). Within the positive valence domain, non-drug and drug-related reward processing (drug craving) are the most favorable multi-level targets for addiction treatment. Within the negative valence domain, acute or chronic withdrawal/negative reinforcement, anhedonia, and negative mood/anxiety comorbidities should be considered. EF with a broad definition has also potential to be targeted in neuromodulation (208). For more details, please see Table 1 .

Brain Stimulation Studies in SUD

There is a trend of reporting positive results in tDCS and rTMS trials in SUD that is being reflected in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. In a meta-analysis published in 2013 on 17 eligible trials, Jansen, et al., reported that rTMS and tDCS on DLPFC could decrease drug craving (209). A meta-analysis of 10 rTMS studies identified a beneficial effect of high-frequency rTMS on craving associated with nicotine use disorder but not alcohol (210). Another meta-analysis published in 2018 by Song, et al., including 48 tDCS and rTMS studies targeting the DLPFC, reported positive overall effects on reducing drug craving and consumption with larger effect for multi-session interventions compared to single-session interventions (211). A recent meta-analysis with 15 studies using tDCS among nicotine dependents reported positive effect on craving and consumption (212). However, there is a large variation in methodological details (mainly ignored in meta-analyses) that makes it hard to find trials replicating previous findings using same stimulation protocols. Some of these methodological variations are being introduced below with few examples.

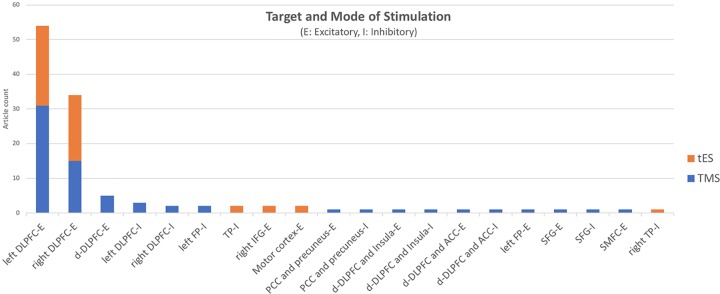

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of published tES/TMS studies based on their target areas. Most but not all published tES/TMS studies (90%) have targeted the DLPFC in order to indirectly target other areas within the EF network or other limbic/paralimbic areas through their connections to the DLPFC. As an example, Terraneo et al. showed that applying 15-Hz stimulation to the left DLPFC can reduce self-reported craving [visual analogue scale (VAS)] and cocaine use (urinalysis) among patients with cocaine use disorder randomized to receive active or sham repetitive TMS (rTMS) (213). In another study, Yang et al. showed that electrical stimulation over the DLPFC helps lower cigarette craving in nicotine-dependent individuals (214). Participant smokers underwent 1 session of real and sham transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in a cross-over setting with 30 min duration and 1-mA intensity. There are studies targeting other areas than the DLPFC within the frontal cortex, such as inferior frontal gyrus, ventromedial prefrontal, or middle frontal cortices. As an example, Kearney-Ramos et al. demonstrated that applying continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) as a type of TMS to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex could attenuate the cue-related functional connectivity (215). In another study, Ceccanti et al. found out that deep TMS (dTMS) on the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) decreased craving and alcohol intake in people with alcohol use disorder. There are also studies targeting motor cortex and temporoparietal areas which have shown that tDCS reduces behavior in tobacco users. To conclude (as shown in Figure 1 ), the distribution of international resources across all these circuit/process/behavior targets provides interesting explorative results to date. Ignoring these methodological variations could result in positive results in meta-analysis reports. However, considering these methodological details would make it hard to introduce a stimulation protocol with enough evidence for clinical use. There is a critical need in the international NIBS research community to focus on one or two main targets to explore any potentially replicable effects that could determine suitable avenues for clinical application.

Figure 1.

Brain areas targeted with inhibitory (i) and excitatory (e) protocols in 96 tES/TMS studies among people with substance use disorder (as of May 1, 2019) (ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; FP, frontal pole; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; SMFC, superior medial frontal cortex; tES, transcranial electrical stimulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; TP, temporoparietal).

Application of other areas of NIBS such as FUS, tNS in addiction medicine is limited to a few case reports. Beyond NIBS, invasive brain stimulation technologies like deep brain stimulation (DBS) are only just emerging as approaches in addiction medicine with only a few case reports or pilot trials in the literature. Consequently, the lack of robust evidence for invasive neuromodulation precludes any judgment regarding its clinical utility.

Challenges for Implementation Into Practice

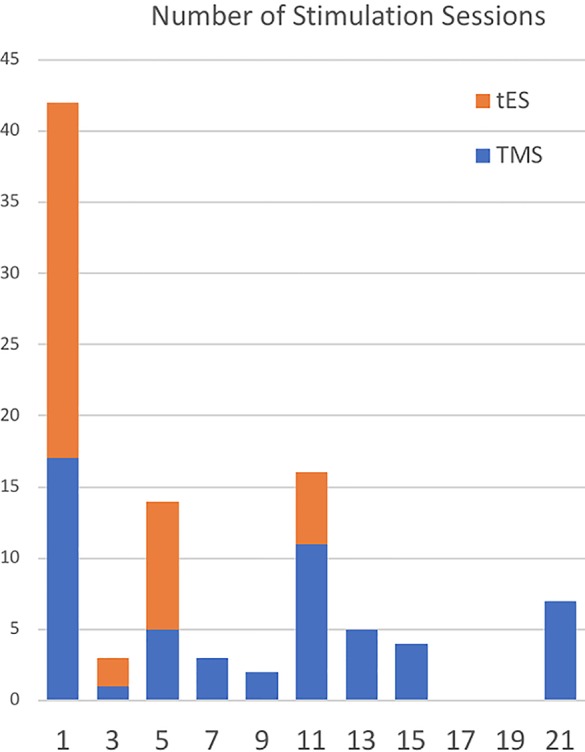

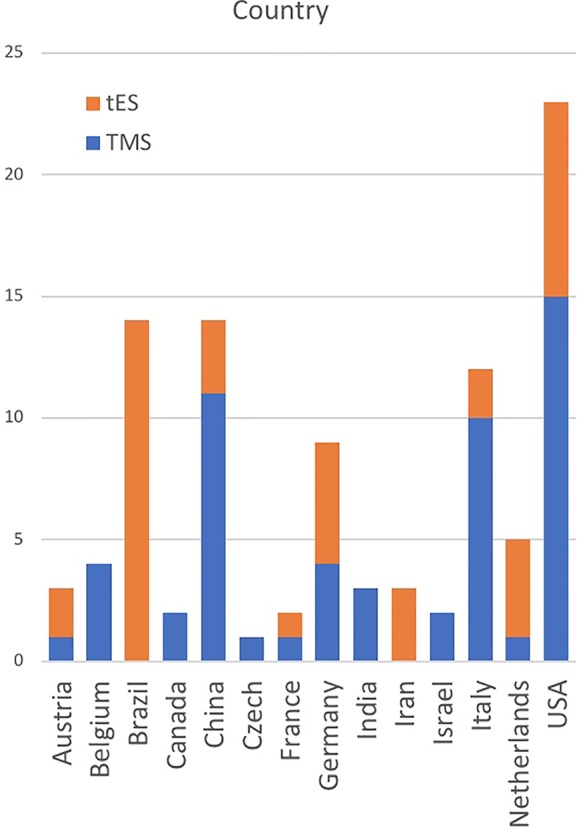

There are 96 original tES/TMS publications in addiction medicine as of May 1, 2019 mainly reporting positive results with one to over 20 sessions of stimulation ( Figure 2 ). Large space of methodological parameters to select from, small sample sizes, and lack of replication across different labs make it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding its effectiveness. Published tES/TMS evidence for addiction treatment has been generated by labs in 14 countries so far ( Figure 3 ). To focus these efforts, there is a need for an international roadmap to harmonize the current activities in the field across the world using methodologically rigorous designs. We hope ISAM-NIG along with other international collaborative networks like International Network of tES/TMS Trials for Addiction Medicine (INTAM) can serve to develop and navigate this roadmap. The ISAM-NIG neuromodulation roadmap should also align with ISAM-NIG roadmaps in other areas like brain imaging, cognitive assessments or cognitive training, and this publication is the first attempt at this initiative. These domains of clinical addiction neuroscience can then work hand-in-hand to create tangible outcomes in daily clinical practice. The challenges for implementing neuromodulation studies into practice are summarized below:

Figure 2.

Number of sessions in 96 TMS/tES studies among people with substance use disorder. Around half of the published studies in the field have used just a single session of intervention (as of May 1, 2019). tES, transcranial electrical stimulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Figure 3.

International contribution to the published evidence with tES/TMS in people with substance use disorder. Contribution of 14 different countries (as of May 1, 2019) in the filed confirms the importance of international partnership to improve quality of research in the field. tES, transcranial electrical stimulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

How to move beyond single session interventions: 44% of the tES/TMS studies have recruited a single session of intervention to investigate potential effects to then move forward to multiple session studies ( Figure 2 ). By comparison, most of the medications, we use in daily clinical practice in psychiatry today probably do not show significant effects with a single dose. Even adding a sensitive biomarker like a human brain mapping measure using fMRI will not be sufficient for a “no-go” or “fast-fail” decision. In a recent trial with NIMH fast-fail framework, 8 weeks of medication was being considered as the minimum dosage of intervention (216). Meanwhile, running multi-session trials is costly and decisions between the wide range of available parameters to apply and measure are complex.

How to narrow down key brain targets and relevant SUD-relevant cognitive processes/behaviors: There is a wide range of potential targets for neuromodulation. There is not a consensus on a framework that specifically defines (i) key neuromodulation targets, (ii) their relevant substance use, cognitive, and clinical outcomes, as different brain pathways are ascribed to heterogeneous neurobehavioral processes ( Table 1 ), (iii) measurement instruments of desired outcomes with highest psychometric properties.

How to find the best target population/timing for intervention/contextual treatment: Timing of neuromodulation intervention [before treatment, before initiating abstinence, during early abstinence (detoxification), after early abstinence (maintenance)] and contextual treatment (pharmacotherapies, psychosocial interventions, cue exposure, cognitive remediation, etc.) in parallel to neuromodulation are important areas for future explorations with specific considerations in different SUDs.

How to optimize the large parameter space within each NIBS technology at the individual level: There is a new effort to optimize the stimulation parameter for each individual subject based on their subjective responses or objective biomarkers in closed-loop stimulation. Bayesian optimization protocols have introduced an interesting area with initial positive response with transcranial alternating current (tACS) stimulation (217). Additionally, personalized brain treatment targets can be identified using neurofeedback machine learning approaches that discriminate distinct patterns of brain function within each individual, instead of a priori brain regions (or their connectivity) across various individuals (218).

Neurofeedback Studies in SUD

Real-time neurofeedback allows online voluntary regulation of brain activity and has shown promise to enhance ascribed cognitive processes in health and psychopathology (219–221). Participants can monitor their brain function in real time through a brain computer interface (BCI), typically showing a thermometer representing the "temperature" of which increases/decreases in real time, to reflect changes in the level of brain function. Neurofeedback aids participants to voluntarily change brain function online using distinct cognitive strategies (e.g., focus on and away from drug-related stimuli). Neurofeedback has been most consistently tested in ADHD and other psychopathologies, with very early evidence being available in SUD.

Neurofeedback is a promising tool that enables mapping of the causal mechanisms of SUD. As core brain dysfunction is identified within a SUD, neurofeedback can be used as a personalized intervention to enhance and recover underlying dysfunctional neurocognitive pathways. Neurofeedback can source and target brain activity using distinct brain imaging techniques including EEG and fMRI (222).

EEG-based neurofeedback allows individuals to modulate the intensity of brain oscillations at specific frequencies (e.g., alpha, beta, theta, alpha-theta, theta-alpha). These protocols have often been used in conjunction with sensorimotor rhythm training (223) to improve efficacy in SUD. EEG-based neurofeedback studies have targeted brain function in varying SUD groups including alcohol, opioid, and stimulant use disorders [see detailed review here (224)]. This body of work led to mixed evidence of effects (and lack of) on abstinence in the week and months following neurofeedback training, as well as reduced disinhibition, craving, and severity of dependence symptoms. A paucity of studies has shown that these effects were stronger when EEG neurofeedback was used in conjunction with existing standard psychological, pharmacological, and rehabilitation treatments.