Abstract

There is a rapidly increasing interest in organic thin film thermoelectrics. However, the power factor of one molecule thick organic film, the self-assembled monolayer (SAM), has not yet been determined. This study describes the experimental determination of the power factor in SAMs and its length dependence at an atomic level. As a proof-of-concept, SAMs composed of n-alkanethiolates and oligophenylenethiolates of different lengths are focused. These SAMs were electrically and thermoelectrically characterized on an identical junction platform using a liquid metal top-electrode, allowing the straightforward estimation of the power factor of the monolayers. The results show that the power factor of the alkyl SAMs ranged from 2.0 × 10–8 to 8.0 × 10–12 μW m–1 K–2 and exhibited significant negative length dependence, whereas the conductivity and thermopower of the conjugated SAMs are the two opposing factors that balance the power factor upon an increase in molecular length, exhibiting a maximum power factor of 3.6 × 10–8 μW m–1 K–2. Once correction factors about the ratio of effective contact area to geometrical contact area are considered, the values of power factors can be increased by several orders of magnitude. With a newly derived parametric semiempirical model describing the length dependence of the power factor, it is investigated that one molecule thick films thinner than 10 nm composed of thiophene units can yield power factors rivaling those of famed organic thermoelectric materials based on poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/polystyrenesulfonate (PEDOT/PSS) and polyaniline/graphene/double-walled carbon nanotube. Furthermore, how the transition of the transport regime from tunneling to hopping as molecules become long affects power factors is examined.

Short abstract

A combined experimental−simulation investigation of thermoelectric performance for one molecule thick films allows access to connecting a molecular-level structure with a thermoelectric power factor.

Introduction

The study of organic thin film thermoelectrics is important from both a fundamental and practical point of view. In terms of the fundamental aspect, it helps to unravel the mechanism of charge transport across an ensemble of molecules.1−8 In terms of the practical aspect, it holds the promise of developing flexible, lightweight, solution-processable, and low-cost thermoelectric generators or Peltier devices under moderate temperature gradients.9−14 Recently, significant efforts have been devoted to enhance the power factor (PF)—a measure of how much electricity a material can generate at once at a given temperature—of organic thin films. PF is defined as κ × S2 where κ (S/cm) is the electrical conductivity and S (μV/K) is the Seebeck coefficient. As examples, the PF of DMSO-mixed poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/polystyrenesulfonate (PEDOT/PSS) has been reported as 469 μW m–1 K–2,15 and an organic thin film composed of polyaniline (PANI), graphene, and double-walled carbon nanotube (DWCN) has been shown to have a PF of 1825 μW m–1 K–2,16 rivaling the values of conventional thermoelectric inorganic semiconductors. Despite the recent advances in the field of organic thin film thermoelectrics, it is still unclear how atomic-detail structural modifications in active organic components affect the PF of the thermoelectric devices in many cases. This is primarily because of uncertainties that arise from the complicated (supra)molecular structures of active components and organic–electrode interfaces.

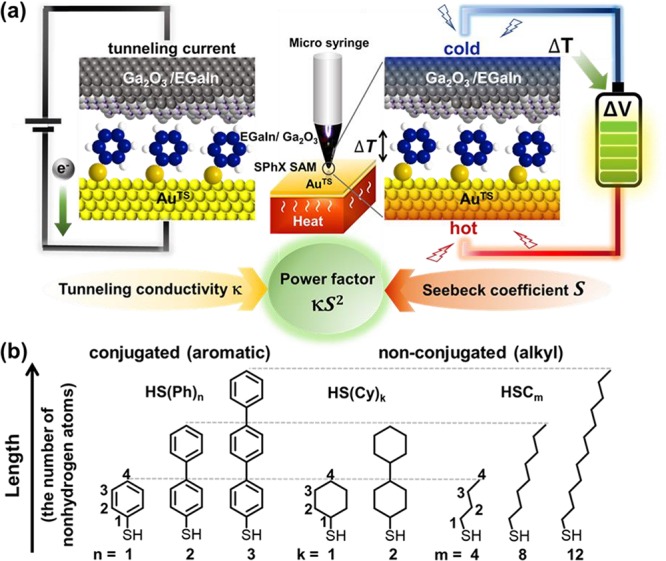

Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) are one molecule thick two-dimensional (2D) organic nanomaterials17 and have been used for a number of applications, yet their PF never has been experimentally determined.1−3,5,7,8,13 Here we measure the PF of SAMs and examine the length dependence of PF at the atomic level. SAMs were formed on the template-stripped gold (AuTS),18 and these were incorporated into large-area junctions using the conical tips of eutectic gallium–indium covered with conductive native oxide (denoted as Ga2O3/EGaIn; Figure 1a),8,19 and the length dependences of the tunneling conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, and PF were investigated. As a proof-of-concept, structurally simple molecules of oligophenylenethiolates (S(Ph)n; n = 1, 2, 3), n-alkanethiolates (SCm; m = 4, 8, 12), and cyclohexanethiolates (S(Cy)k; k = 1, 2) were focused (Figure 1b). We revealed that both the conductivity and thermopower of the alkyl SAMs decreased with the increasing molecular length, thereby leading to a significant decrease in PF from 2.0 × 10–8 to 8.0 × 10–12 μW m–1 K–2. On the other hand, the conductivity of the conjugated SAMs was found to decrease with the increasing length, whereas the thermopower increased. This trade-off led to a nonlinear length dependence of the PF ranging from 2.6 × 10–8 to 3.6 × 10–8 μW m–1 K–2. Once the ratio of effective contact area to geometrical contact area was considered, the values of PF could be increased by several orders of magnitude. We further derived a parametric semiempirical model that describes the length dependence of PF in monolayers. Simulation of PF using this model suggests that one molecule thick organic films (< ∼ 10 nm)—with taking the form of SAMs—composed of thiophene units that exhibit a negative tunneling decay coefficient (i.e., an increase in conductivity with increasing the length) can yield PFs rivaling those of renowned organic thermoelectric materials based on PEDOT/PSS and PANI/graphene/DWCN. Further study allows access to how the transition of transport regime from tunneling to hopping as molecules become long affect power factors. Our study demonstrates that the SAM-based junctions not only can be a useful nanoscale platform to draw inferences on atomic-detail structure-power factor relations but also have the potential as a ultrathin organic thermoelectric generator over low-grade heat.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic describing the structure of the large-area tunneling and thermoelectric junction we used. (b) Molecules we used in this study and the numbering of non-hydrogen atoms from sulfur to the most distal atom to define the length of the molecule.

Results and Discussion

The length dependences of tunneling current density (J, A/cm2) and thermopower (S, μV/K) in SAM-based junctions can be described using the following models. The simplified Simmons model20−22 in eq 1 is widely used to explain the length dependence of J:

| 1 |

where β (Å–1, per carbon (nC–1), or phenylene (nPh–1)) is the conductance decay constant, J0 (A/cm2) is the charge injection current density, and d (Å or the number of carbon (m in SCm) or phenylene (n in S(Ph)n) is the width of the tunneling barrier usually taken from the molecular length. Likewise, the length dependence of thermopower can be described using eq 2:3,8,23

| 2 |

where SSAM is the thermopower of SAM, S0 (μV/K) is the thermopower corresponding to the molecule–electrode interfaces, and βS (μV·(K·Å)−1, μV·(K·nC)−1, or μV·(K–1·nPh)−1) is the rate of change of S as the value of d varies.

Figure 1b shows the molecules we used to form SAMs. These molecules were chosen for the following reasons. (i) Fabrication procedures of S(Ph)n and SCm SAMs, their on-surface (supra)molecular and electronic structures, and the electrical characteristics have been established.4,24−27 (ii) The thermopower of S(Ph)n SAMs has been widely examined in separate junction platforms, and thus, they could be used as standard molecules in thermopower measurements.3,4,8 (iii) The tunneling conductance and Seebeck coefficient of these SAMs can be measured on the identical junction platform, an EGaIn-based large-area junction. (iv) Comparison of S(Ph)n SAMs with the analogous SCm and S(Cy)k SAMs with the same anchoring group and a similar thickness (defined as the total number of non-hydrogen atoms from the sulfur to the most distal atom as shown in Figure 1b) makes it possible to determine the effect that the conjugation in the backbone of the SAM has on the PF. (v) The addition of phenylene units into the benzenethiolate leads to an increase in the vertical conjugation length of the backbone, which leads to an increase and decrease in the Seebeck coefficient and the electrical conductance, respectively.3,4,8,24 Therefore, this structural design allows an investigation into how such a trade-off between the conductance and thermopower affects the PF.

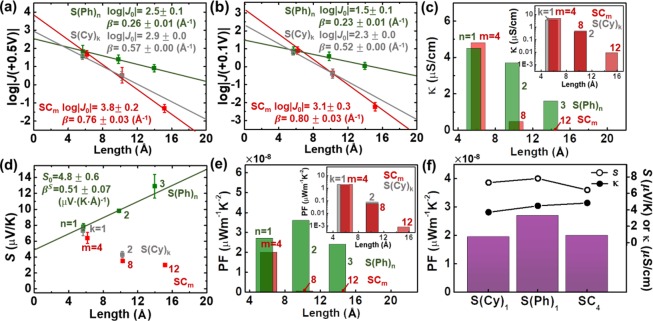

The SAMs were synthesized, and large-area molecular junctions were constructed following the previously reported procedures in the literature (see the Supporting Information for details; in our experiments, no unexpected or unusually high safety hazards were encountered).4,8,22,28 The SAMs were characterized with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and confirmed the formation of monolayers by analyzing the S 2p high resolution spectra29,30 (see the Supporting Information for details). In a typical experiment, a sufficient amount of J–V traces in the voltage range of 0–0.5 V was collected, and then histograms of log|J| were plotted, from which the mean (log|J|mean) and standard deviation (σlog|J|) values were extracted. Figures S1–S8 in the Supporting Information summarize the log|J|−V traces and log|J| histograms. The length dependence of log|J| is shown in Figure 2a. For S(Ph)n, the values of β and J0 were 0.26 ± 0.01 Å–1 and 102.5±0.1 A/cm2, respectively, and those for SCm were 0.76 ± 0.03 Å–1 and 103.8±0.2 A/cm2. These values were consistent with the literature values (see Figure S9 in the Supporting Information).24,25 For the shortest molecules of each series (SPh1, S(Cy)1, and SC4), values of log|J| were indistinguishable (see Figure 2a), and this observation was consistent with the literature result.26 For S(Cy)k, the values of β and J0 were 0.57 ± 0.00 Å–1 and 102.9±0.0 A/cm2, respectively. The β of S(Cy)k was slightly lower than that of SCm. This difference in β is perhaps due to the difference in conformational order and/or the difference in hyperconjugation between S(Cy)k and SCm. According to previous studies,31,32 the hyperconjugation between Au–S and the hydrocarbon backbone of molecules depends on the conformational order of molecules in SAMs and can affect the electrical properties. Further study is needed to confirm this hypothesis. Note that while we could synthesize S(Cy)2 SAM following the method reported in the literature,33 the synthesis of pure HS(Cy)3 was difficult. To obtain the tunneling conductivity (κ, S/cm), the following equation was used: κ = J /E where E is the electric field (V/m).34 This equation is valid when the J–E relationship is linear (i.e., in the Ohmic regime). Hence, the J value in the low bias regime (|J| at +0.1 V; Figure 2b) was used to determine the value of E. The value of E was also determined (i) by assuming that the distance between two electrodes in junctions is equal to the length of the fully extended molecule (d, Å) used to form the SAM for the sake of simplicity and (ii) by calculating the vertical distance (d·cos θ) between the electrodes considering the cant angle (θ) of the molecules as shown in Figure S14 in the Supporting Information. The observed trends of E, κ, and PF values determined using the two different methods were similar (see Tables S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information). For the following discussion, the results determined by the first method are used.

Figure 2.

Plots of (a) log|J(+0.5 V)|, (b) log|J(+0.1 V)|, (c) conductivity (κ, μS/cm), (d) Seebeck coefficient (S, μV/K), and (e) power factor (PF, μW m–1 K–2) as a function of the molecular length (d, Å). Insets in panels c and e show the κ and PF values of SCm and S(Cy)k in semi-log10 scale, respectively. (f) Comparisons of κ, S, and PF for the short molecules of similar thickness (SC4, S(Cy)1, and S(Ph)1).

Values of SSAM were estimated following a previously reported procedure.4,8 Briefly, thermovoltage (ΔV, μV) histograms were measured at the temperature gradients of ΔT = 4, 8, and 12 K, respectively, and the mean (ΔVmean) and standard deviation (σΔV) of ΔV were extracted from the histograms via single Gaussian fitting curves. Figures S10–S12 in the Supporting Information summarize the ΔV histograms at different ΔT. According to the definition of S = −ΔV/ΔT, the slope in the plot of ΔV as a function of ΔT was used to determine the Seebeck coefficient of junctions (Sjunction), which was converted to SSAM following a previously reported procedure (see the Supporting Information for details).

Table 1 summarizes the result of our junction measurements. We observed that, as the length of molecule increased, κ decreased for both S(Ph)n and SCm (Figure 2c). However, S decreased and increased with an increase in length for SCm and S(Ph)n, respectively (Figure 2d). Note that a recent study35 has revealed that the decrease rate of S as the molecular length increases is different for short and long n-alkanethiolates, which accounts for the nonlinear S trend of SCm observed in Figure 3d. Because of the apparent decrease in both the κ and S values, the PF of the SCm SAMs exhibited substantially negative length dependence (the inset in Figure 2e). By contrast, the κ and S values decreased and increased, respectively, upon the change in the molecular length for S(Ph)n, making them opposing factors that balance out the PF and, interestingly, lead to nonlinear length dependence of the PF (Figure 2e). Thus, the variation in the molecular length for S(Ph)n (and not for SCm) could be a strategy by which to optimize the PF. Indeed, while the PFs of S(Ph)n SAMs ranged from 2.6 × 10–8 to 3.6 × 10–8 μW m–1 K–2, the maximum value was observed for S(Ph)n with n = 2. The trends of κ, S, and PF for S(Cy)k were nearly identical to SCm. Among the short molecules with similar lengths, SC4, S(Ph)1 and S(Cy)1, S(Ph)1 exhibited a PF ≈ 1.4 times higher than the PFs of the other molecules (Table 1 and Figure 2f). The reason for this is mainly due to the difference in S rather than κ. Whereas the enhancement in the PF as a result of the conjugation in the backbone was not huge in the shortest molecules tested, the effect of conjugation had a huge impact on the long molecules. For example, the PF of the S(Ph)3 was approximately 3 orders of magnitude (∼3250 times) higher than that of the SC12.

Table 1. Summary of Tunneling Conductivity (κ), Seebeck Coefficient (S), and Power Factor (PF) of the SAMs Composed of the Molecules Shown in Figure 1a.

| molecule | κ (μS/cm) | S (μV/K) | PF (μW m–1 K–2) | corrected PFa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC4 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 2.0 × 10–8 | 2.0 × 10–5 – 2.0 × 10–2 |

| SC8 | 4.7 × 10–1 | 3.5 | 5.7 × 10–10 | 5.7 × 10–7 – 5.7 × 10–4 |

| SC12 | 8.9 × 10–3 | 3.0 | 8.0 × 10–12 | 8.0 × 10–9 – 8.0 × 10–6 |

| S(Ph)1 | 4.5 | 7.8 | 2.7 × 10–8 | 2.7 × 10–5 – 2.7 × 10–2 |

| S(Ph)2 | 3.7 | 9.8 | 3.6 × 10–8 | 3.6 × 10–5 – 3.6 × 10–2 |

| S(Ph)3 | 1.6 | 12.9 | 2.6 × 10–8 | 2.6 × 10–5 – 2.6 × 10–2 |

| S(Cy)1 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 2.0 × 10–8 | 2.0 × 10–5 – 2.0 × 10–2 |

| S(Cy)2 | 4.2 × 10–1 | 4.3 | 7.7 × 10–10 | 7.7 × 10–7 – 7.7 × 10–4 |

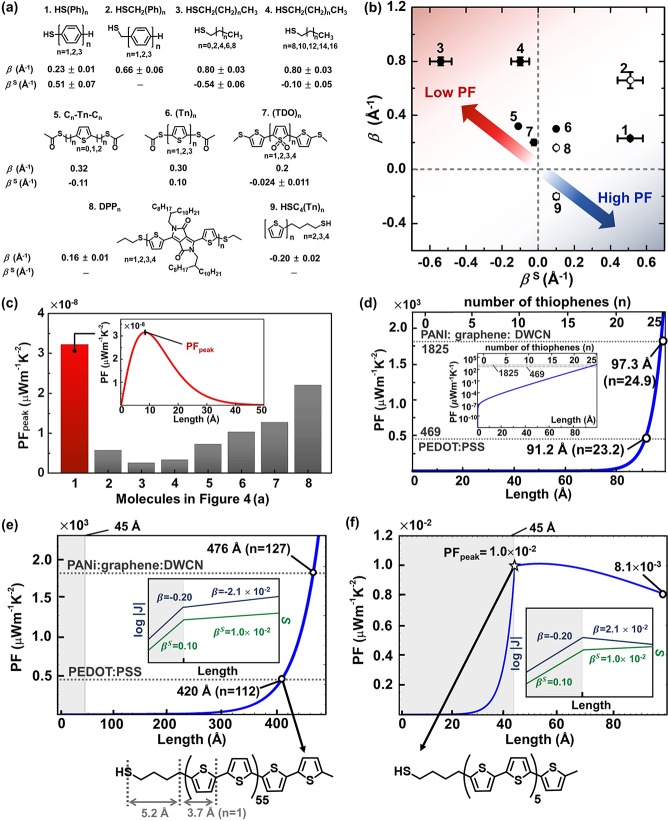

Figure 3.

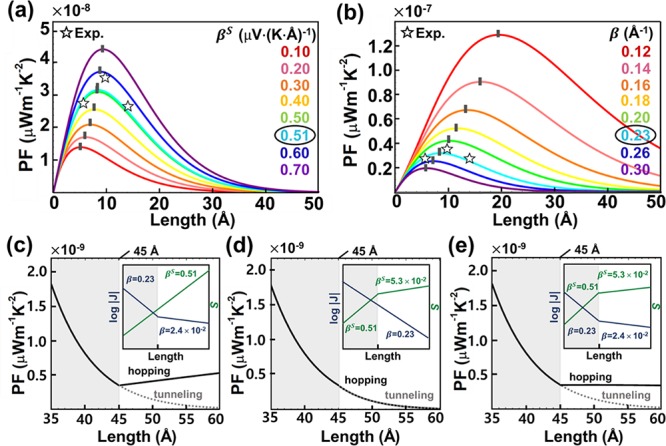

Simulation of PF trends using eq 3 for S(Ph)n SAMs. (a) Trends of PF as a function of molecular length and βS. (b) Trends of PF as a function of molecular length and β. Inflection points correspond to peak values of PF (PFpeak). The numbers in circles correspond to the experimental values. Star symbols are the experimental data points. (c–e) Plots of PF against molecular length for the three different cases: (c) β is lowered at 45 Å (gray-white boundary) due to the transition of transport regime from tunneling to hopping, whereas βS remains constant; (d) βS is lowered, whereas β remains constant after the transition; (e) both β and βS are lowered. The insets show the changes in β and βS for each case. Noncorrected PF values are used for simulations.

The surface of EGaIn tip is rough, and thus the effective contact area that participates indeed in charge tunneling largely differs from the geometrical contact area, as determined by optical microscopy. Separate studies25,36,37 estimated the ratio of the effective contact area to the geometrical contact area to be ∼10–3 to ∼10–6 in EGaIn-based junctions. Taking these values into account, corrected PFs were obtained; for example, the corrected PFs for S(Ph)3 were found to be in the range of 2.6 × 10–5 – 2.6 × 10–2 μW m–1 K–2 (Table 1).

The use of the same junction testbed for tunneling and thermopower measurements allowed the combination of the length dependence models of J and S (eqs 1 and 2). Consequently, a parametric semiempirical formula was derived to address the length dependence of the PF in one molecule thick organic films:

| 3 |

For the series of molecules based on the same top- and bottom-interfaces, J0 and S0 became constant at the EGaIn junction. This enabled the simulation of the correlations between the PF and molecular length (Å or the number of methylene or phenylene units), β, and βS using eq 3. For simulation, we focused on conjugated molecules, S(Ph)n. As shown in Figure 3a,b, the experimental and simulated data were consistent for S(Ph)n validating eq 3 and confirming that PF increases as β and βS decrease and increase, respectively. The simulations confirm that the length dependence of PF is nonlinear, as evidenced by the Gaussian shape of PF trends and the presence of inflection points (peak values of PF; PFpeak) in Figure 3a,b, and that the PF can be optimized by varying the molecular length in conjugated SAMs.

When molecules composing SAMs become long, the charge transport regime can be transitioned from tunneling to hopping.38−41Table S11 in the Supporting Information summarizes previous studies that examined the molecular length at which such a transition occurs. The transition can affect the values of β and/or βS; hopping usually leads to the reduction in the magnitude of |β| and |βS|.39,40,42−44 Therefore, in addition to the simulation based on pure tunneling in Figure 3a,b, we considered two further cases where the transition affects (i) either β and/or βS, and (ii) both of them. According to the literature survey (Table S11 and S12 in the Supporting Information), the averaged molecular length where hopping dominates the transport was ∼45 Å, and the values of β and/or βS were reduced by a factor of ∼9.6 when the transition occurred.39−48 On the basis of this information, we considered the effect of hopping in long molecules on PF for simulation. The change in β had a significant effect on PF (Figure 3c,e), whereas the change in βS did not result in a large difference in PF compared to pure tunneling (Figure 3d). This finding indicates the more pronounced contribution of β to PF than that of βS in oligophenylenes. Note that the degree of structural disorder may be significantly increased as the length of molecule increases.49 Our model does not account for such an increase in the degree of structural disorder, if any.

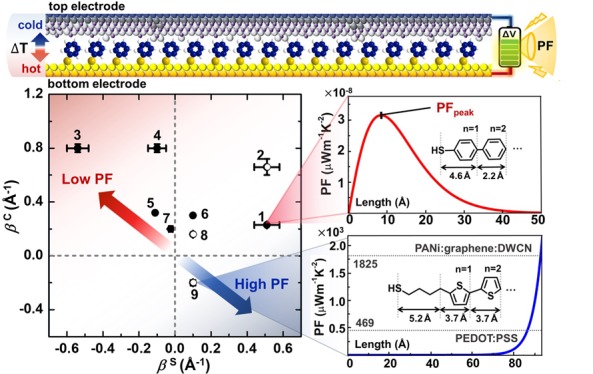

Using eq 3, we further examined the PF of one molecule thick organic films that have the conjugated or nonconjugated backbones: phenylene (1, 2(24)), n-alkane (3, 4),35 thiophene (5–6,507,51952), and diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP; 8)53 in Figure 4a. β for these molecules has been experimentally determined in the literature, and we used these values for simulating PF values. While β for various types of molecules has been reported in the literature, few studies have reported βS values. Note that these values were mostly determined in the tunneling regime. For the molecules 2, 8, and 9, we assumed that the βS of 2 is the same as 1, and the βS of 8 and 9 are the same as 6. This assumption is plausible considering the structural similarity in the repeating units (Figure 4a). For the sake of simplicity, we also assumed that J0 and SC for the molecules 2–9 are the same as those for molecules 1; that is, the PF is measured in the same junction platform, allowing direct comparison of PF values between the molecules. Because there is a difference in βS between short and long n-alkanethiolates,35 short (3) and long (4) n-alkanethiolates were separately considered.

Figure 4.

(a) Molecules we tested (1) in this study and reported in the previous studies (2–9) in which the values of β and/or βS have been reported. (b) Plot of β against βS for the molecules shown in (a). The open circle indicates the molecules whose βS is not reported in the literature. We assumed the βS of 2 is the same as 1, and the βS values of 8 and 9 are the same as 6. This assumption is plausible given similarity in the structure of repeating units. (c) Peak values of PF (PFpeak) of molecules estimated with eq 3 in the main text. The inset shows an exemplary plot describing the Gaussian curve relationship between PF and molecular length for the molecules 1. (d) The trend of PF as a function of molecular length for molecules 9. Dotted lines indicate the literature values corresponding to highly efficient organic thermoelectric materials (PEDOT/PSS and PANI/graphene/DWCN where DWCN is double-walled carbon nanotube). The inset shows the same PF graph in semi-log10 scale. The value of n indicates the number of thiophene units in compound 9. (e–f) Plots of PF against molecular length for the two different cases: (e) both β and βS are lowered with the same sign (see the inset). (f) β is lowered with inversion of the sign, and βS is lowered with same sign. Noncorrected PF values are used.

In our comparison, the magnitude and sign of β played a critical role in determining the size of PF. Figure 4b presents the plot of β and βS for the molecules shown in Figure 4a. Equation 3 indicates that more positive βS and more negative β lead to higher PF (Figure 4b). The molecules with positive β values showed Gaussian shapes in PF trend as shown in the inset in Figure 4c; the molecules 3 and 1 have the lowest (2.5 × 10–9 μW m–1 K–2) and highest (3.2 × 10–8 μW m–1 K–2) PFpeak values, respectively (Figure 4c). The molecules 9 exhibit negative β, in which conductivity increases with increasing the molecular length.52 This negative sign of β yielded the trend of PF’s length dependence that was completely different from those for the molecules with the positive β: the PF increased with increasing the length for the molecules 9 (Figure 4d). Notably, we observed that PF begins to exponentially increase at the point of d = ∼ 70 Å. Interestingly, our simulation enabled us to propose the number of thiophene units in the molecules 9 to rival the PF values of PEDOT/PSS15 and hybrid materials (PANI/graphene/DWCN, where DWCN is the double-walled carbon nanotube)16 exhibiting great thermoelectric performances. This simulation was based on the assumption that the values of β and βS are linearly extrapolated to systems beyond short oligomers. When the molecules 9 become longer (up to 23 and 25 thiophene units, which correspond to the one molecule thick films of ∼9.1 and ∼9.7 nm, respectively), the PF values can reach the values of the PEDOT/PSS and the hybrid materials.

As described in oligophenylenes (Figure 3c–e), we could take into account the occurrence of the transport regime transition from tunneling to hopping in long oligothiophenes. Our simulation showed that, if hopping dominates in both thermopower and conductance while the sign of β and βS does not change, the exponential increase in PF can be still observed, although the PF values equivalent to those of the PEDOT:PSS and the hybrid materials can be achieved by a factor of ∼5 longer molecules (420 and 476 Å) than those predicted in pure tunnelling (Figure 4e). If the transition also causes the inversion of sign in β, the trend of exponential increase with length is no longer valid, and a peak value (PFpeak = 1.0 × 10–2) is observed at the boundary of the transition (Figure 4f). This finding implies that the length dependence of conductance has a more pronounced effect on PF than the length dependence of thermopower. Further study will be needed to confirm this prediction. The simulation results for the cases where one of β and βS changes due to the transition of transport regime are summarized in Figures S16 and S17 in the Supporting Information. Exponential increase of PF was observed unless the sign of β did not change; however, if the sign of β was inversed, the length dependence of PF almost disappeared.

Although this work is fundamental in nature, thermoelectric performance of SAM-based devices warrants further investigation, considering that organic thin film thermoelectric materials have recently received an increased amount of attention for use in micro-thermoelectric generators (μ-TEGs) suitable for converting low-grade waste heat into electricity.11,14,15,54 In this regard, determination of the dimensionless figure of merit (ZT = (κS2/λ)T) of a SAM-based junction can be insightful. By taking the thermal conductivity value (λ = 3.6 × 104 μW m–1 K–1 for SC12) experimentally determined in recent studies (see the Supporting Information for details),55−57 the ZT value estimated for the SC12 SAM as an exemplary case was 6.6 × 10–14 for the noncorrected PF at T = 295 K, and the corrected PF ranged from 6.6 × 10–11 to 6.6 × 10–8. Note that the ZT value of SAM-based junction cannot be straightforwardly compared with that of other organic semiconductors unless the operating temperature is the same.

Conclusion

In this work, the PFs of one molecule thick organic films, SAMs, were experimentally determined for the first time. Statistically robust values for the tunneling conductivity and Seebeck coefficient at identical junctions were measured, which allowed reliable PF values to be estimated for SAMs. We derived a useful parametric semiempirical equation to investigate the effects of β and βS on the length dependence of PF. Our simulation using this equation proposes that ultrathin organic films (e.g., less than 10 nm) can yield PF values that rival conventional high-performance organic materials. Given that recent studies58−60 show the thermal conductance across single molecules does not depend on the length of molecule, our work reveals the potential of ultrathin organic films as active materials for thermoelectric generators. Moreover, this work offers an unprecedented opportunity to harness SAM-based junctions as a nanoscale platform for establishing structure–PF relationships at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019R1A2C2011003; NRF-2019R1A6A1A11044070). S.P. acknowledges the support of the Korea University Graduate School Junior Fellowship and the POSCO TJ Park Doctoral Fellowship.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.9b01042.

Materials and characterization, synthesis and characterization of molecules, SAM preparation, electrical measurements, determination of electric field, tunneling conductivity and power factor, thermoelectric junction measurements, and supplementary figures and tables (PDF)

Author Contributions

† S.P. and S.K. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cui L.; Miao R.; Jiang C.; Meyhofer E.; Reddy P. Perspective: Thermal and Thermoelectric Transport in Molecular Junctions. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 092201. 10.1063/1.4976982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A.; Balachandran J.; Sadat S.; Gavini V.; Dunietz B. D.; Jang S.-Y.; Reddy P. Effect of Length and Contact Chemistry on the Electronic Structure and Thermoelectric Properties of Molecular Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8838–8841. 10.1021/ja202178k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Kang H.; Yoon H. J. Structure-Thermopower Relationships in Molecular Thermoelectrics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 14419–14446. 10.1039/C9TA03358K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.; Park S.; Kang H.; Cho S. J.; Song H.; Yoon H. J. Tunneling and Thermoelectric Characteristics of N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Based Large-Area Molecular Junctions. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 8780–8783. 10.1039/C9CC01585J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon-Garcia L.; Evangeli C.; Rubio-Bollinger G.; Agrait N. Thermopower Measurements in Molecular Junctions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4285–4306. 10.1039/C6CS00141F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubnova O.; Crispin X. Towards Polymer-Based Organic Thermoelectric Generators. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9345–9362. 10.1039/c2ee22777k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S.; Wu Q.; Sadeghi H.; Lambert C. J. Thermoelectric Properties of Oligoglycine Molecular Wires. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 3567–3573. 10.1039/C8NR08878K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Yoon H. J. New Approach for Large-Area Thermoelectric Junctions with a Liquid Eutectic Gallium-Indium Electrode. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7715–7718. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ B.; Glaudell A.; Urban J. J.; Chabinyc M. L.; Segalman R. A. Organic Thermoelectric Materials for Energy Harvesting and Temperature Control. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16050. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Qiu L.; Tang L.; Geng H.; Wang H.; Zhang F.; Huang D.; Xu W.; Yue P.; Guan Y. S.; Jiao F.; Sun Y.; Tang D.; Di C. A.; Yi Y.; Zhu D. Flexible n-Type High-Performance Thermoelectric Thin Films of Poly(Nickel-Ethylenetetrathiolate) Prepared by an Electrochemical Method. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3351–3358. 10.1002/adma.201505922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Sun Y.; Xu W.; Zhu D. Thermoelectric Materials: Organic Thermoelectric Materials: Emerging Green Energy Materials Converting Heat to Electricity Directly and Efficiently. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6829–6851. 10.1002/adma.201305371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk J.-H.; Fang H.; Yazawa K.; Shakouri A. Flexible Thermoelectric Materials and Device Optimization for Wearable Energy Harvesting. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 10362–10374. 10.1039/C5TC01644D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Miao R.; Wang K.; Thompson D.; Zotti L. A.; Cuevas J. C.; Meyhofer E.; Reddy P. Peltier Cooling in Molecular Junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 122–127. 10.1038/s41565-017-0020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubnova O.; Khan Z. U.; Malti A.; Braun S.; Fahlman M.; Berggren M.; Crispin X. Optimization of the Thermoelectric Figure of Merit in the Conducting Polymer Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene). Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 429–433. 10.1038/nmat3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G. H.; Shao L.; Zhang K.; Pipe K. P. Engineered Doping of Organic Semiconductors for Enhanced Thermoelectric Efficiency. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 719–723. 10.1038/nmat3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho C.; Stevens B.; Hsu J.-H.; Bureau R.; Hagen D. A.; Regev O.; Yu C.; Grunlan J. C. Completely Organic Multilayer Thin Film with Thermoelectric Power Factor Rivaling Inorganic Tellurides. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2996–3001. 10.1002/adma.201405738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love J. C.; Estroff L. A.; Kriebel J. K.; Nuzzo R. G.; Whitesides G. M. Self-Assembled Monolayers of Thiolates on Metals as a Form of Nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1103–1169. 10.1021/cr0300789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss E. A.; Kaufman G. K.; Kriebel J. K.; Li Z.; Schalek R.; Whitesides G. M. Si/SiO2-Templated Formation of Ultraflat Metal Surfaces on Glass, Polymer, and Solder Supports: Their Use as Substrates for Self-Assembled Monolayers. Langmuir 2007, 23, 9686–9694. 10.1021/la701919r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiechi R. C.; Weiss E. A.; Dickey M. D.; Whitesides G. M. Eutectic Gallium-Indium (EGaIn): A Moldable Liquid Metal for Electrical Characterization of Self-Assembled Monolayers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 142–144. 10.1002/anie.200703642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons J. G. Electric Tunnel Effect between Dissimilar Electrodes Separated by a Thin Insulating Film. J. Appl. Phys. 1963, 34, 2581–2590. 10.1063/1.1729774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H. J.; Bowers C. M.; Baghbanzadeh M.; Whitesides G. M. The Rate of Charge Tunneling Is Insensitive to Polar Terminal Groups in Self-Assembled Monolayers in AgTS-S(CH2)nM(CH2)mT//Ga2O3/EGaIn Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16–19. 10.1021/ja409771u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.; Kong G. D.; Yoon H. J. Deconvolution of Tunneling Current in Large-Area Junctions Formed with Mixed Self-Assembled Monolayers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 4578–4583. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b01997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quek S. Y.; Choi H. J.; Louie S. G.; Neaton J. B. Thermopower of Amine-Gold-Linked Aromatic Molecular Junctions from First Principles. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 551–557. 10.1021/nn102604g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. M.; Rappoport D.; Baghbanzadeh M.; Simeone F. C.; Liao K.-C.; Semenov S. N.; Żaba T.; Cyganik P.; Aspuru-Guzik A.; Whitesides G. M. Tunneling across SAMs Containing Oligophenyl Groups. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 11331–11337. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b01253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone F. C.; Yoon H. J.; Thuo M. M.; Barber J. R.; Smith B.; Whitesides G. M. Defining the Value of Injection Current and Effective Electrical Contact Area for EGaln-Based Molecular Tunneling Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18131–18144. 10.1021/ja408652h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H. J.; Shapiro N. D.; Park K. M.; Thuo M. M.; Soh S.; Whitesides G. M. The Rate of Charge Tunneling through Self-Assembled Monolayers Is Insensitive to Many Functional Group Substitutions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4658–4661. 10.1002/anie.201201448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon S. E.; Kim M.; Yoon H. J. Maskless Arbitrary Writing of Molecular Tunnel Junctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 40556–40563. 10.1021/acsami.7b14347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G. D.; Jin J.; Thuo M. M.; Song H.; Joung J. F.; Park S.; Yoon H. J. Elucidating the Role of Molecule-Electrode Interfacial Defects in Charge Tunneling Characteristics of Large-Area Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12303–12307. 10.1021/jacs.8b08146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; Yuan L.; Cao L.; Nijhuis C. A. Controlling Leakage Currents: The Role of the Binding Group and Purity of the Precursors for Self-Assembled Monolayers in the Performance of Molecular Diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1982–1991. 10.1021/ja411116n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G. D.; Yoon H. J. Influence of Air-Oxidation on Rectification in Thiol-Based Molecular Monolayers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, G115–G121. 10.1149/2.0091609jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Wang Z.; Oyola-Reynoso S.; Thuo M. M. Properties of Self-Assembled Monolayers Revealed Via Inverse Tensiometry. Langmuir 2017, 33, 13451–13467. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Chang B.; Oyola-Reynoso S.; Wang Z.; Thuo M. Quantifying Gauche Defects and Phase Evolution in Self-Assembled Monolayers through Sessile Drops. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2072–2084. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waske P. A.; Meyerbröker N.; Eck W.; Zharnikov M. Self-Assembled Monolayers of Cyclic Aliphatic Thiols and Their Reaction toward Electron Irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 13559–13568. 10.1021/jp210768y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann B.; Kuhn H. Tunneling through Fatty Acid Salt Monolayers. J. Appl. Phys. 1971, 42, 4398–4405. 10.1063/1.1659785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Cho N.; Yoon H. J. Two Different Length-Dependence Regimes in Thermoelectric Large-Area Junctions of n-Alkanethiolates. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 5973–5890. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b02461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. P.; Roemer M.; Yuan L.; Du W.; Thompson D.; del Barco E.; Nijhuis C. A. Molecular Diodes with Rectification Ratios Exceeding 105 Driven by Electrostatic Interactions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 797–803. 10.1038/nnano.2017.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda Ocampo O. E.; Gordiichuk P.; Catarci S.; Gautier D. A.; Herrmann A.; Chiechi R. C. Mechanism of Orientation-Dependent Asymmetric Charge Transport in Tunneling Junctions Comprising Photosystem I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8419–8427. 10.1021/jacs.5b01241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L.; Choi S. H.; Frisbie C. D. Probing Hopping Conduction in Conjugated Molecular Wires Connected to Metal Electrodes. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 631–645. 10.1021/cm102402t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q.; Liu K.; Zhang H.; Du Z.; Wang X.; Wang F. From Tunneling to Hopping: A Comprehensive Investigation of Charge Transport Mechanism in Molecular Junctions Based on Oligo (p-Phenylene Ethynylene)s. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3861–3868. 10.1021/nn9012687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Kim B.; Frisbie C. D. Electrical Resistance of Long Conjugated Molecular Wires. Science 2008, 320, 1482–1486. 10.1126/science.1156538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Risko C.; Delgado M. C. R.; Kim B.; Brédas J.-L.; Frisbie C. D. Transition from Tunneling to Hopping Transport in Long, Conjugated Oligo-Imine Wires Connected to Metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4358–4368. 10.1021/ja910547c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Huang C.; Gulcur M.; Batsanov A. S.; Baghernejad M.; Hong W.; Bryce M. R.; Wandlowski T. Oligo (Aryleneethynylene)s with Terminal Pyridyl Groups: Synthesis and Length Dependence of the Tunneling-to-Hopping Transition of Single-Molecule Conductances. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 4340–4347. 10.1021/cm4029484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Frisbie C. D. Enhanced Hopping Conductivity in Low Band Gap Donor- Acceptor Molecular Wires up to 20 nm in Length. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16191–16201. 10.1021/ja1060142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Xiang L.; Palma J. L.; Asai Y.; Tao N. Thermoelectric Effect and Its Dependence on Molecular Length and Sequence in Single DNA Molecules. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11294. 10.1038/ncomms11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines T.; Diez-Perez I.; Hihath J.; Liu H.; Wang Z.-S.; Zhao J.; Zhou G.; Mullen K.; Tao N. Transition from Tunneling to Hopping in Single Molecular Junctions by Measuring Length and Temperature Dependence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11658–11664. 10.1021/ja1040946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis W. B.; Svec W. A.; Ratner M. A.; Wasielewski M. R. Molecular-Wire Behaviour in p-Phenylenevinylene Oligomers. Nature 1998, 396, 60. 10.1038/23912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada R.; Kumazawa H.; Tanaka S.; Tada H. Electrical Resistance of Long Oligothiophene Molecules. Appl. Phys. Express 2009, 2, 025002. 10.1143/APEX.2.025002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. E.; Odoh S. O.; Ghosh S.; Gagliardi L.; Cramer C. J.; Frisbie C. D. Length-Dependent Nanotransport and Charge Hopping Bottlenecks in Long Thiophene-Containing Π-Conjugated Molecular Wires. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15732–15741. 10.1021/jacs.5b07400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youm S. G.; Hwang E.; Chavez C. A.; Li X.; Chatterjee S.; Lusker K. L.; Lu L.; Strzalka J.; Ankner J. F.; Losovyj Y.; Garno J. C.; Nesterov E. E. Polythiophene Thin Films by Surface-Initiated Polymerization: Mechanistic and Structural Studies. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 4787–4804. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. B.; Mai C.-K.; Kotiuga M.; Neaton J. B.; Bazan G. C.; Segalman R. A. Controlling the Thermoelectric Properties of Thiophene-Derived Single-Molecule Junctions. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 7229–7235. 10.1021/cm504254n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dell E. J.; Capozzi B.; Xia J.; Venkataraman L.; Campos L. M. Molecular Length Dictates the Nature of Charge Carriers in Single-Molecule Junctions of Oxidized Oligothiophenes. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 209. 10.1038/nchem.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Soni S.; Krijger T. L.; Gordiichuk P.; Qiu X.; Ye G.; Jonkman H. T.; Herrmann A.; Zojer K.; Zojer E.; Chiechi R. C. Tunneling Probability Increases with Distance in Junctions Comprising Self-Assembled Monolayers of Oligothiophenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15048–15055. 10.1021/jacs.8b09793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y.; Ray S.; Fung E.-D.; Borges A.; Garner M. H.; Steigerwald M. L.; Solomon G. C.; Patil S.; Venkataraman L. Resonant Transport in Single Diketopyrrolopyrrole Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13167–13170. 10.1021/jacs.8b06964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Sheng P.; Di C.; Jiao F.; Xu W.; Qiu D.; Zhu D. Organic Thermoelectric Materials and Devices Based on p- and n-Type Poly(Metal 1,1,2,2-Ethenetetrathiolate)s. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 932–937. 10.1002/adma.201104305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losego M. D.; Grady M. E.; Sottos N. R.; Cahill D. G.; Braun P. V. Effects of Chemical Bonding on Heat Transport across Interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 502–506. 10.1038/nmat3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien P. J.; Shenogin S.; Liu J.; Chow P. K.; Laurencin D.; Mutin P. H.; Yamaguchi M.; Keblinski P.; Ramanath G. Bonding-Induced Thermal Conductance Enhancement at Inorganic Heterointerfaces Using Nanomolecular Monolayers. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 118–122. 10.1038/nmat3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Segalman R. A.; Majumdar A. Room Temperature Thermal Conductance of Alkanedithiol Self-Assembled Monolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 173113. 10.1063/1.2358856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Hur S.; Akbar Z. A.; Klockner J. C.; Jeong W.; Pauly F.; Jang S.-Y.; Reddy P.; Meyhofer E. Thermal Conductance of Single-Molecule Junctions. Nature 2019, 572, 628–633. 10.1038/s41586-019-1420-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosso N.; Sadeghi H.; Gemma A.; Sangtarash S.; Drechsler U.; Lambert C.; Gotsmann B. Thermal Transport through Single-Molecule Junctions. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 7614–7622. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil S. Measuring heat flow through a single molecule. Chem. Eng. News 2019, 97 (42), 5.October 28. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.