Abstract

Objective:

Continuing to smoke after a cancer diagnosis undermines prognosis. Yet, few trials have tested FDA-approved tobacco use medications in this population. Extended use varenicline may represent an effective treatment for cancer patients who smoke given barriers to cessation including a prolonged time-line for relapse.

Methods:

A placebo-controlled randomized trial tested 12 weeks of varenicline plus 12 weeks of placebo (standard; ST) vs. 24 weeks of varenicline (extended; ET) with 7 counseling sessions for treatment-seeking cancer patients who smoke (N=207). Primary outcomes were 7-day, biochemically-confirmed abstinence at weeks 24 and 52. Treatment adherence and side effects, adverse and serious adverse events, and blood pressure were assessed.

Results:

Point prevalence and continuous abstinence quit rates at weeks 24 and 52 were not significantly different across treatment arms (p’s>0.05). Adherence (43% of sample) significantly interacted with treatment arm for week 24 point prevalence (OR=2.31, [95% CI:1.15–4.63, p=0.02) and continuous (OR=5.82, [95% CI:2.66–12.71], p<.001) abstinence. For both outcomes, adherent participants who received ET reported higher abstinence (60.5%, 44.2%) vs. ST (44.7%, 27.7%), but differences in quit rates between arms were not significant for non-adherent participants (ET: 9.7%, 4.8%; ST: 12.7%, 10.9%). There were no significant differences between treatment arms on side effects, adverse and serious adverse events, and rates of high blood pressure (p’s>0.05).

Conclusions:

Compared to ST, ET varenicline does not increase patient risk and increases smoking cessation rates among patients who adhere to treatment. Studies are needed to identify effective methods to increase medication adherence to treat patient tobacco use effectively.

Keywords: adherence, cancer, extended treatment, smoking cessation, safety, varenicline

Introduction

The Surgeon General concluded that continued smoking by cancer patients is causally associated with all-cause and cancer-specific mortality.1 Unfortunately, upwards of 50% of cancer patients who smoked prior to their diagnosis, continue to do so.2 Consequently, leading cancer research and advocacy organizations have called for the improved treatment of tobacco use in the oncologic setting.3 Given the remarkable improvements in cancer care, leading to 14 million current cancer survivors,4 demonstrating the safety and efficacy of treatments for tobacco dependence in this population is a priority.

Few trials have evaluated smoking cessation interventions for cancer patients, which may contribute to the low rate of clinician treatment of patient tobacco use.5 Smoking cessation interventions for cancer patients may be successful if population-specific cessation barriers are targeted. First, continuing to smoke after a cancer diagnosis centrally linked to tobacco is a hallmark of tobacco dependence.6 While 35–54% of the general population of smokers report smoking their first cigarette within 30 minutes after waking,7,8 a measure of tobacco dependence,9 this rate among cancer patients is 69–81%.10–13 Second, smoking cessation interventions for cancer patients may need to address the psychological distress6,14 and cognitive impairment15–17 that often accompanies diagnosis and medical treatment and trigger smoking relapse. Lastly, smoking cessation treatments for cancer patients may need to consider the protracted time-line for smoking relapse among cancer patients.14 In the general population of smokers, the majority of smokers who achieve abstinence and relapse do so within 1–2 weeks.18 Studies with cancer patients show that the majority of relapse to smoking occurs 2–6 months following initial abstinence.19

Extended use varenicline20 could be well suited for cancer patients who smoke. Varenicline, mitigates the adverse psychological effects and withdrawal-related cognitive impairment associated with quitting smoking.21,22 We have shown in the general population that extending the use of transdermal nicotine to 24 weeks increases quit rates, vs. 8 weeks, and significantly reduces the probability of a smoking lapse and increases the likelihood that smokers recover to abstinence.23 While population and medication differences are important, extended duration varenicline may address cessation barriers among cancer patients.

A pilot study and an initial report describing 12-week open-label outcomes from this trial indicated that varenicline might be safe and efficacious for cancer patients.24,25 However, no study – with cancer patients or in the general population – has examined the efficacy and safety of extended varenicline treatment. This trial was designed to address this gap and determine if extended-use varenicline should be considered for treating tobacco use among cancer patients.

Methods

This placebo-controlled trial () randomized participants to 12 weeks of varenicline followed by 12 weeks of placebo (standard; ST) or 24 weeks of varenicline (extended; ET). All participants received 7 guideline-based smoking cessation counseling sessions over 24 weeks (4 in person; 3 by phone), which focused on developing cessation skills, relapse prevention, and the importance of treatment adherence.26 Assessments were done in person or by phone and compensation (up to $110) was provided. The protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (#815687) and informed consent was ascertained. The study statistician provided a randomization procedure (1:1) to the Penn Investigational Drug Service (IDS), which distributed pills. All personnel, except IDS, were blinded to assignment.

Participants

Using two cancer centers’ electronic medical records, patients were screened for tobacco use and contacted by telephone. An in-person intake visit confirmed eligibility. To be eligible, participants had to be ≥18 years of age, have a diagnosis of cancer or a recurrence within the past 5 years, report smoking ≥5 cigarettes per week, and self-report an interest in quitting smoking. Participants were excluded for daily use of nicotine products other than cigarettes, and unstable substance abuse/dependence in the last year. Additional inclusion and exclusion information can be found elsewhere.27

Procedures

The eligibility visit involved the completion of questionnaires, a medical history, and assessments of psychiatric history.28 Eligibility was confirmed by a physician and psychologist who reviewed the intake measures. If eligible, participants were scheduled for a pre-quit session (week 0) during which they received cessation counseling and initiated medication. For the first 12 weeks, all participants received open-label varenicline (Pfizer; Groton, CT) according to FDA approved labeling: Day 1-Day 3 (0.5mg once daily); Day 4–7 (0.5mg twice daily); and Day 8-Day 84 (1.0mg twice daily). All participants received smoking cessation counseling at weeks 1 (target quit date), 4, 8, 12, 14, and 18 by phone or in-person.29 At week 12, ST participants received 12 weeks of placebo pills and ET participants received 12 weeks of varenicline (1.0mg twice daily).

Measures

At the eligibility visit, demographic and smoking history data were assessed. A carbon monoxide (CO) breath sample was obtained and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTCD)30 was completed. Disease-related characteristics, including the Karnofsky Score and the ECOG Performance Status, were assessed.

A checklist and open-ended items assessed the incidence and severity of varenicline-related side effects29 at weeks 0, 1, 4, 8, 12, 14, 18, 24, 26, and 52 in-person or by telephone. Each symptom was rated from 0 (none) to 3 (severe). Blood pressure was assessed at weeks 0, 1, 4, 12, 24, and 52. A previously developed algorithm29 classified side effect reports as adverse (AEs) or Serious Adverse Events (SAEs).

Pill and counseling adherence was tracked. Counseling adherence was defined as completing ≥5/7 sessions (71%). The time-line follow-back method (TLFB)31 and collection of used blister packs tracked pill adherence.29 A pill adherence measure represented the proportion of total dose taken over the 24 weeks (adherence: ≥80% of 333 pills prescribed). We also collected a blood sample at week 4 among Penn participants who agreed to provide a blood sample and attended this session (N=76) to determine varenicline plasma levels.32

Smoking was assessed using TLFB and breath CO.23 The primary outcomes were 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at Weeks 24 and 52 and a CO <10ppm.33,34 Continuous abstinence (with CO) from Weeks 9–24 and 9–52 were secondary outcomes consistent with past varenicline trials.35 We examined time to relapse (in days) from the quit day (week 1) until a relapse (7 consecutive days of self-reported smoking) and smoking lapse and recovery;36 a smoking lapse was defined as any day between the quit date and the week 24 and 52 assessments on which participants smoked (even a puff); recovery was defined as any 24-hour period of self-reported abstinence post-lapse. The analyses focused on treatment arm effects on time to transition between smoking and abstinent days.23 We used intent-to-treat (ITT), meaning that participants lost to follow-up or failing to provide CO were considered smokers.

Analysis

The sample was characterized in terms of demographic, smoking, and disease characteristics. Variables listed in Table 1 (and clinical site) that differed between treatment arms (p<.05) were covariates in the analyses. Pill (self-report, varenicline levels) and counseling session adherence were characterized and compared across treatment arms.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample

| Characteristic | Standard (N=102) N(%) or M(SD) |

Extended (N=105) N(%) or M(SD) |

Total (N=207) N(%) or M(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Sex (% Female) | 46 (45.1%) | 59 (56.2%) | 105 (50.1%) |

| Race (% Minority) | 30 (29.4%) | 33 (31.4%) | 63 (30.4%) |

| Marital status (% Married) | 54 (52.9%) | 50 (47.6%) | 104 (50.2%) |

| Education (% GED or less) | 34 (33.3%) | 39 (37.1%) | 73 (35.3%) |

| Income (% < 20,000/year) | 28 (27.5%) | 16 (15.7%) | 44 (21.6%) |

| Employment (% Employed)* | 41 (40.2%) | 59 (56.2%) | 100 (48.3%) |

| Age | 60.0 (9.5) | 58.0 (9.4) | 58.5 (9.4) |

| Disease variables | |||

| Tumor type | |||

| Cancer stage | |||

| Karnofsky score | 91.7 (11.7) | 92.1 (10.9) | 91.9 (11.2) |

| ECOG score | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.25 (0.43) |

| Time since first diagnosis (Months) | 19.1 (20.7) | 20.0 (18.5) | 19.5 (19.6) |

| Smoking variables | |||

| Cigarettes per day | 13.2 (8.6) | 13.5 (7.9) | 13.4 (8.3) |

| Fagerström Nicotine Dependence | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.5 (2.1) |

| Carbon monoxide | 18.2 (11.3) | 19.7 (11.0) | 19.0 (11.1) |

| Age started smoking (Mean, SD) | 16.2 (5.1) | 16.8 (5.0) | 16.7 (5.1) |

| Years smoked (Mean, SD) | 40.9 (12.0) | 40.0 (10.7) | 40.4 (11.3) |

Note.

p<.05.

To examine treatment arm effects on smoking cessation outcomes at week 24 and 52, we used logistic regression. For time to relapse, we used linear regression. Multivariate time-to-event models determined whether treatment arm predicted transitions from abstinence to lapse and from lapse to recovery.23 Participants lost to follow-up on TLFB (for time to event analyses) were censored at that time (removed from the risk-set without registering an event). Safety data were assessed by examining treatment arm effects on mean and total (count) side effects using repeated-measures factorial ANOVA. We examined safety data collected at weeks 0 (pre-treatment), 4, 12, 18, and 24 to assess changes during the open-label phase and when the ST participants switched to placebo. Chi-square was used to compare the cumulative frequencies of adverse events and serious adverse events from Weeks 0–24 across treatment arms and the rates of high blood pressure at Weeks 0, 12, and 24. Analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) or STATA (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We used an alpha level of .05 for all statistical tests.

Results

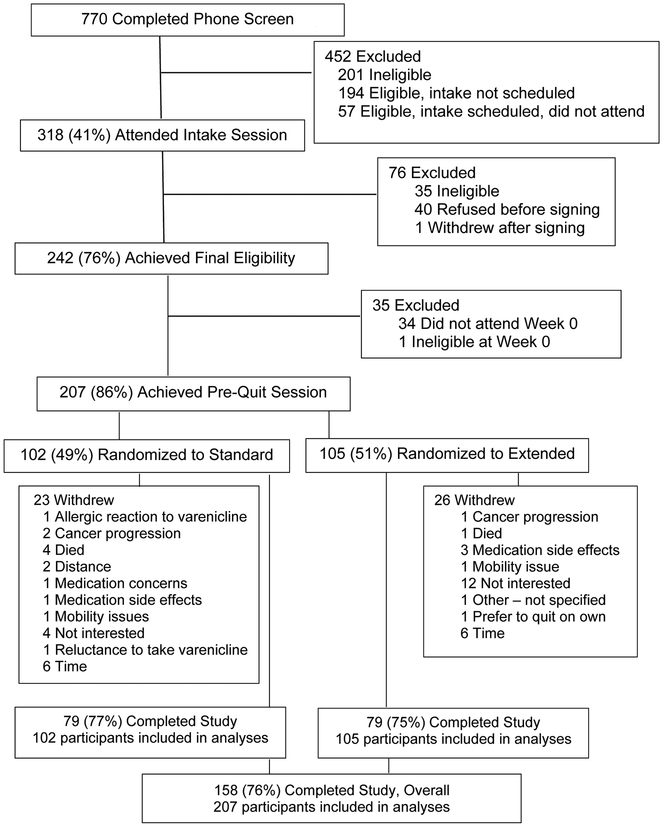

The trial recruited from May 2013 until June 2017. Screening and recruitment is shown in Figure 1; 207 participants were randomized and completed the Week 0 counseling session, and were considered ITT. Retention was 75% and did not differ across treatments (ST=7.5% vs. ET=72.4%; χ2[1]=0.47, p=0.52).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the entire sample and by treatment arms. A greater proportion of the ET participants were employed (56.2%), vs. ST (40.2%; χ2[1]=5.32, p=0.02), which was included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. The average number of counseling sessions completed was 5.2 (SD=2.1) and there was no difference between ST (M=5.4) and ET (M = 5.1) (F[1,206]=0.55, p=0.46); 66% of participants completed ≥5 counseling sessions and this rate did not differ between ST (69%) and ET (63%) (χ2[1]=0.77, p=0.46). The average number of pills taken was 185.6 (SD=125.5) and there was no difference between ST (M=188.5) and ET (M=182.6) (F[1,197]=0.11, p= 0.74); 46.1% of ST participants reported taking ≥80% of pills, vs. 41% of ET participants (χ2[1]=0.55, p=0.49). Overall plasma varenicline levels at week 4 were 7.27ng/mL (SD=3.6) and did not differ across ST (6.9ng/mL) and ET (7.6ng/mL) (F[1,75]=0.85, p=0.36). Based on the 4.0ng/mL varenicline cut-point,32 90% of the sample were adherent and this did not differ across ST (95%) and ET (85%) (χ2[1]=2.1, p=0.26). Using the pill count data, varenicline adherence was strongly associated with point prevalence and continuous abstinence at weeks 24 and 52 (p’s<.01). Thus, we assessed a treatment X varenicline adherence interaction as post hoc analysis; we did not include counseling adherence since it was collinear with medication adherence (r=0.82) and used pill count data since that is the measure most commonly used in the literature.37

Varenicline Efficacy

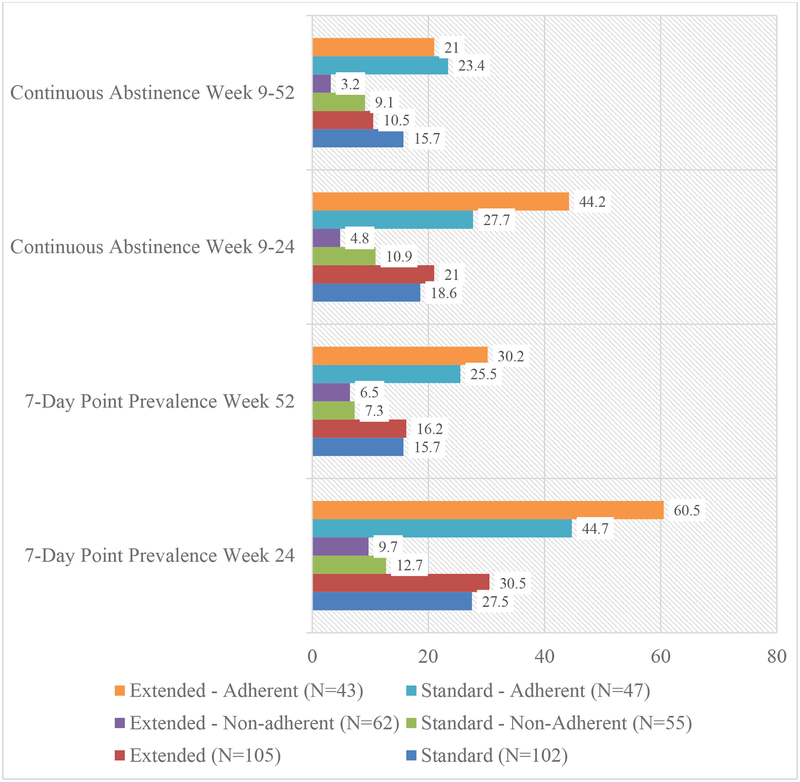

The 7-day point prevalence and continuous abstinence rates across treatments are shown in Figure 2. At week 24, the rates of point prevalence abstinence between ST (27.5%) and ET (30.5%) were not significantly different (OR=0.71 [95% CI:0.38–1.34], p=0.29). Likewise, at week 52, the rates of point prevalence abstinence between ST (15.7%) and ET (16.2%) were not significantly different (OR=0.92 [95% CI:0.43–1.96], p=0.83). The rates of continuous abstinence between ST (18.6%) and ET (21%) were not significantly different at week 24 (OR=0.78 [95% CI:0.39–1.57], p=0.39) or week 52 (10.5% vs. 15.7%; OR=1.61 [95% CI:0.70–3.70], p=0.26).

Figure 2.

Rates of 7-day point prevalence and continuous abstinence at weeks 24 and 52 across treatment arm and adherence groups based on pill count.

Figure 2 shows abstinence rates across treatment and adherence groups. At week 24, the interaction of treatment and adherence was significant for point prevalence abstinence (OR=2.31 [95% CI:1.15–4.63], p=.02). While there was little difference in week 24 point prevalence abstinence between ST and ET for non-adherent participants (9.7% vs. 12.7%), adherent participants in ET reported significantly higher point prevalence abstinence (60.5%) vs. adherent participants in ST (44.7%; p=.04). At week 52, the treatment X adherence interaction was significant (OR=2.21, [95% CI:1.00–4.95], p=.05). While adherent participants in ET (30.2%) reported higher point prevalence abstinence, vs. ST participants (25.5%), the comparison was not significant (p>.05). At week 24, the interaction for treatment and adherence was significant for continuous abstinence (OR=5.82 [95% CI:2.66–12.71], p<.001). While the difference in week 24 continuous abstinence between ST and ET for non-adherent participants was not significantly different (9.7% vs. 12.7%; p=0.33), adherent participants in ET reported a trend toward higher continuous abstinence (44.2%) vs. adherent participants in ST (27.7%; p=.07). At week 52, the interaction of treatment and adherence was not significant (OR=2.16, [95% CI:0.89–5.24], p=.09). There were no significant treatment effects on risk for relapse, lapse, or recovery (p’s>.05).

Varenicline Safety

Assessment of the change in mean side effect severity and the total frequency of side effects from week 0 (pre-treatment), through weeks 4, 12, 18, and 24 showed no significant time X treatment effects (p’s>.05). Likewise, there were no significant differences between treatments in the number of participants who reported AEs or SAEs between weeks 0 to 24 (p’s>.05) or in the frequency of hypertension assessed at weeks 0, 12, and 24 (p’s>.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Side effects, adverse events, and serious adverse events across treatment arm

| Variable | Standard | Extended | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=102) | (N=105) | (N=207) | |

| Participants with an Adverse Event | 27 (26.5%) | 25 (23.8%) | 52 (25.1%) |

| Participants with a Serious Adverse Event | 9 (8.8%) | 13 (12.4%) | 22 (10.6%) |

| Total Number of Adverse Events | 63 | 50 | 113 |

| Weakness | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Skin swelling, rash, or redness | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Depression | 21 | 20 | 41 |

| Respiratory infection | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Cancer recurrence | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Suicidality | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Nausea, abdominal pain | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Irritability | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Agitation | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Hostility | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| High cholesterol | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hemorrhoids | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Heart attack | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Headache | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Dizziness | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Gout (worsening) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pins and needles feeling | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Fainting | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Asthma attack | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Bronchitis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cholecytstosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cirrhosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bracial plexopathy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Blurred vision | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Arterial injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total Number of Serious Adverse Events | 25 | 18 | 43 |

| Dehydration, fluid build-up | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dysphagia and difficulty breathing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Facial edema | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Fever and swelling | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hernia | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Confusion | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Anxiety (panic) attack | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Constipation and bleeding | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| COPD | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Second cancer | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Chest pain | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Radiation burn infection | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Seizure | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Abdominal abscess | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cracked ribs | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Injury from fall | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Headaches | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Death | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Cancer progression | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Blood loss | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Anemia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bladder perforation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Enterocolotis infection | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pelvic infection | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Prostatic obstruction | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of High Blood Pressure Recordings | 8 | 7 | 15 |

Discussion

We tested whether providing cancer patients interested in quitting smoking with 24 weeks of varenicline improved cessation rates vs. 12 weeks of varenicline and was safe. Contrary to our hypothesis, the quit rates at weeks 24 and 52 were similar between the treatments. When considering varenicline adherence, however, ET yielded higher week 24 quit rates, vs. ST. Further, there was no indication that ET varenicline was unsafe, vs. ST.

We25 and others24 showed that 12 weeks of varenicline yields end-of-treatment quit rates for cancer patients that converge with the general population of smokers using varenicline. However, factors unique to cancer patients (e.g., high rates of emotional distress38, which can trigger smoking, and a protracted time-line for relapse) suggest that ET varenicline might be required to ensure long-term smoking cessation success. Contrary to our hypothesis, ET for 24 weeks did not affect week 24 and 52 quit rates. One potential explanation for this result is that participants in the ST arm continued to receive smoking cessation counseling after week 12 (69% completed ≥5 sessions); this was necessary to maintain the medication blind. The continued counseling could have prevented smoking relapse among participants in ST. Indeed, in post-hoc analyses, the rate at which the week 14 and 18 sessions were completed was strongly associated with a greater likelihood for cessation at weeks 24 and 52 (p’s<.05). The week 24 quit rates for both arms resemble the week 24 quit rates following only 12 weeks of varenicline treatment provided to the general population of smokers (i.e., 34–35%).35 The week 24 quit rates are also substantially higher than a previous smoking cessation trial with cancer patients that provided behavioral counseling and bupropion.11 However, it should be noted that the week 52 quit rates overall (~16%) were considerably lower than we have seen in the general population (e.g., 24%).35 Thus, while ET varenicline did not increase week 24 and week 52 quit rates vs. 12 weeks, ET through either medication or counseling may limit relapse, yield quit rates at week 24 that resemble those found among smokers in the general population, and yield higher quit rates seen in previous studies with cancer patients. Even so, the low week 52 quit rates indicate the need for additional intervention to reduce long-term relapse.

Second, based on pill count, <50% of the sample were adherent to varenicline and level of varenicline adherence was associated with quit rates and interacted with treatment to affect quit rates at week 24. These results converge with a growing literature that highlights the importance of adherence in determining varenicline efficacy37 and continues to underscore the need for interventions designed to address medication adherence within tobacco use treatment programs. We have shown previously that greater varenicline adherence among cancer patients may be associated with reductions in depressed mood and perceived satisfaction from smoking and an increase in the toxic effects of smoking, while cognition, craving, and side effects may also be important.27 These results can guide the development and evaluation of interventions targeting varenicline adherence to improve cessation in this population.

Lastly, the assessment of measures of side effects and adverse events indicates that ET varenicline does not undermine safety. Since cancer patients are at heightened risk for depression and may already be experiencing high rates of sleep problems or nausea, it was important to assess if ET varenicline exacerbated such side effects. The potential effectiveness of ET varenicline could be undercut if it worsened common symptoms experienced by cancer patients. The present results suggest that future efforts to improve smoking cessation outcomes with an intervention designed to increase medication adherence across 24 weeks of treatment would not risk increasing adverse events or side effects.

Limitations

This study should be considered in the context of limitations. First, the ITT sample represents only 27% of the screened sample, diminishing the generalizability of the results. Trials with clinical populations experiencing physical and psychiatric comorbidities are challenging to implement given the need to control for potential extraneous variables and patient demands. However, once patients were enrolled, the majority completed counseling and remained in the program. Second, compared to many varenicline trials conducted in the general population35, the present sample was small and statistical power was diminished, which may underlie null effects; given the challenges of recruiting this clinical population, we did not meet our accrual goal of 374. However, this is one of the largest smoking cessation trials conducted with cancer patients. Lastly, adherence to varenicline was low, even vs. the general population where it is typically 50–60%.39,40 With more than half the sample taking less than 80% of the prescribed medication, the therapeutic effect of varenicline was limited, which may have diminished long-term cessation. The complexity and intensity of ongoing medical care for patients may have posed particular challenges for treatment engagement and future studies are needed to develop and test novel approaches for increasing treatment adherence.

Implications

Nevertheless, this study enhances our understanding of tobacco cessation treatment for cancer patients and has implications for the broader population. This is only the second study to examine the use of varenicline for cancer patients and shows that 12 or 24 weeks of treatment, when combined with counseling across 24 weeks, can help õne-third of patients quit smoking without compromising safety. Further, this is the first study – with any population of smokers – to evaluate, using a placebo-controlled design, the benefits of ET varenicline and the results underscore the importance of medication adherence in maximizing the benefit of ET. Future studies are needed to identify effective methods to increase treatment adherence and improve long-term smoking cessation rates to help cancer patients benefit from smoking cessation treatment and enhance their prognosis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by R01 CA165001 and K24 DA045244. Pfizer provided medication and placebo.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Schnoll and Hitsman receive medication and placebo free from, and provide consultation to, Pfizer. Drs. Schnoll and Dr. Kalhan have consulted for GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Schnoll consults with Curaleaf.

References

- 1.Warren GW, Alberg AJ, Kraft AS, Cummings KM. The 2014 Surgeon General’s report: “The health consequences of smoking--50 years of progress”: a paradigm shift in cancer care. Cancer. 2014;120(13):1914–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Land SR, Toll B, Moinpour C, et al. Research priorities, measures, and recommendations for assessment of tobacco use in clinical cancer research. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1907–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toll BA, Brandon TH, Gritz ER, et al. Assessing tobacco use by cancer patients and facilitating cessation: an American Association for Cancer Research policy statement. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1941–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, et al. Practice patterns and perceptions of thoracic oncology providers on tobacco use and cessation in cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:543–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Moor JS, Elder K, Emmons KM. Smoking prevention and cessation interventions for cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:180–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huh J, Timberlake DS. Do smokers of specialty and conventional cigarettes differ in their dependence on nicotine? Addict Behav. 2009;34:204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messer K, Trinidad DR, Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation rates in the United States: a comparison of young adult and older smokers. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:317–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center Tobacco D, Baker TB, Piper ME, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9 Suppl 4:S555–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnoll RA, Rothman RL, Wielt DB, et al. A randomized pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus basic health education for smoking cessation among cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnoll RA, Martinez E, Tatum KL, et al. A bupropion smoking cessation clinical trial for cancer patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin D, et al. Predictors of long-term smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:261–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakefield M, Olver I, Whitford H, Rosenfeld E. Motivational interviewing as a smoking cessation intervention for patients with cancer: Randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2004;53:396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gritz ER, Vidrine DJ, Fingeret MC. Smoking cessation a critical component of medical management in chronic disease populations. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6 Suppl):S414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox LS, Africano NL, Tercyak KP, Taylor KL. Nicotine dependence treatment for patients with cancer. Cancer. 2003;98:632–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biegler KA, Chaoul MA, Cohen L. Cancer, cognitive impairment, and meditation. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirl WF. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of depression in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Jacobsen PB, Patel RD, McCaffrey JC, Oliver JA, Sutton SK, Brandon TH. Predictors of smoking relapse in patients with thoracic cancer or head and neck cancer.. Cancer. 2013. April 1;119(7):1420–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson F, Jepson C, Strasser AA, et al. Varenicline improves mood and cognition during smoking abstinence. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:144–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollema H, Hajos M, Seymour PA, et al. Preclinical pharmacology of the alpha4beta2 nAChR partial agonist varenicline related to effects on reward, mood and cognition. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:813–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, et al. Effectiveness of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park ER, Japuntich S, Temel J, et al. A smoking cessation intervention for thoracic surgery and oncology clinics: a pilot trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1059–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price S, Hitsman B, Veluz-Wilkins A, Blazekovic S et al. The use of varenicline to treat nicotine dependence among cancer patients. Psycho-oncology 2017;26:1526–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update US Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care. 2008;53:1217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford G, Weisbrot J, Bastian J, et al. Predictors of varenicline adherence among cancer patients treated for tobacco dependence and its association with smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998; 59 Suppl 20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerman C, Schnoll RA, Hawk LW, et al. Use of the nicotine metabolite ratio as a genetically informed biomarker of response to nicotine patch or varenicline for smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawford G, Jao N, Peng AR, et al. The association between self-reported varenicline adherence and varenicline blood levels in a sample of cancer patients receiving treatment for tobacco dependence. Addict Behav Rep. 2018;8:46–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SRNT. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387:2507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wileyto EP, Patterson F, Niaura R, et al. Recurrent event analysis of lapse and recovery in a smoking cessation clinical trial using bupropion. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:257–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pacek LR, McClernon FJ, Bosworth HB. Adherence to pharmacological smoking cessation interventions: A literature review and synthesis of correlates and barriers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Symeonides S, Ramessur R, Murray G, Sharpe M. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014. Oct;1:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker TB, Piper ME, Stein JH, et al. Effects of nicotine patch vs varenicline vs combination nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation at 26 weeks: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:371–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng AR, Morales M, Wileyto EP, et al. Measures and predictors of varenicline adherence in the treatment of nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2017;75:122–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]