Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved intracellular degradation system that plays a dual role in cell death; thus, therapies targeting autophagy in cancer are somewhat controversial. Ferroptosis is a new form of regulated cell death featured with the iron-dependent accumulation of lethal lipid ROS. This pathway is morphologically, biochemically and genetically distinct from other forms of cell death. Accumulating studies have revealed crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis at the molecular level. In this review, we summarize the mechanisms of ferroptosis and autophagy, and more importantly, their roles in the drug resistance of cancer. Numerous connections between ferroptosis and autophagy have been revealed, and a strong causal relationship exists wherein one process controls the other and can be utilized as potential therapeutic targets for cancer. The elucidation of when and how to modulate their crosstalk using therapeutic strategies depends on an understanding of the fine-tuned switch between ferroptosis and autophagy, and approaches designed to manipulate the intensity of autophagy might be the key.

Keywords: Autophagy, ferroptosis, crosstalk, cancer, drug resistance

Introduction

Resistance to chemotherapy and molecular targeted therapies is a major problem facing current cancer research, which severely limits the effectiveness of cancer therapies1. Programmed cell death (PCD) is the regulated cell death mediated by an intracellular program under physiological conditions and has fundamental functions in development, differentiation, and aging. As one of the most conventional PCD types, apoptosis is, therefore, the most obvious target of anti-tumor drugs. However, dysregulated apoptotic signaling allows cancer cells to escape this program and leads to the occurrence of drug resistance2,3, which seriously alters the prognosis of patients. The identification of mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer will provide us with the opportunity to develop rational therapeutic regimens to improve clinical outcomes. Successively discovered types of PCD, including autophagy, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis, have facilitated the search for new therapeutic modalities to overcome drug resistance in cancer.

Autophagy is a regulated process in which the cell disassembles unnecessary or dysfunctional organelles and proteins, thereby meeting the metabolic needs of the cell itself4,5. Autophagy presents an opposing, context-dependent role in cancer. The activation of autophagy suppresses the initiation of tumor growth in the early stages of cancer, while in established tumors, the recycling features of autophagy enable the survival and progression of tumors6,7. Thus, the therapeutic targeting of autophagy in cancer is somewhat controversial8.

Ferroptosis, the newly discovered form of regulated cell death, depends upon intracellular iron accumulation and subsequent lipid peroxidation9. In addition to the induction of tissue injury and protective effects on neurodegenerative diseases10–12, the activation of ferroptosis also exhibits a remarkable anticancer activity13.

Emerging studies have discovered that autophagy plays an essential role in the induction of ferroptosis14,15. The identification of the interrelationship between ferroptosis and autophagy will not only enable us to obtain a deeper mechanistic understanding of these two types of PCD but also provide new therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. This review provides an up to date overview of the mechanisms of ferroptosis and autophagy, and the possible pathways or compounds that mediate their crosstalk. Then, we discuss the potential utility of targeting this kind of crosstalk to reverse drug resistance in cancer, which is expected to be a promising therapeutic strategy in the future.

Autophagy overview

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process in eukaryotes. It helps the cell maintain homeostasis under stressful conditions by degrading and recycling unnecessary or dysfunctional organelles and proteins in a double-membraned vacuole known as autophagosomes6,16. Autophagy is enhanced in various physiological conditions, such as embryonic development, starvation, and aging. Also, accumulating evidence has suggested that treatments targeting autophagy represent a potential therapeutic strategy in many diseases, including tumors, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and infections, among others17. In general, autophagy plays an important role in cellular homeostasis, organism growth, and the occurrence of diseases18.

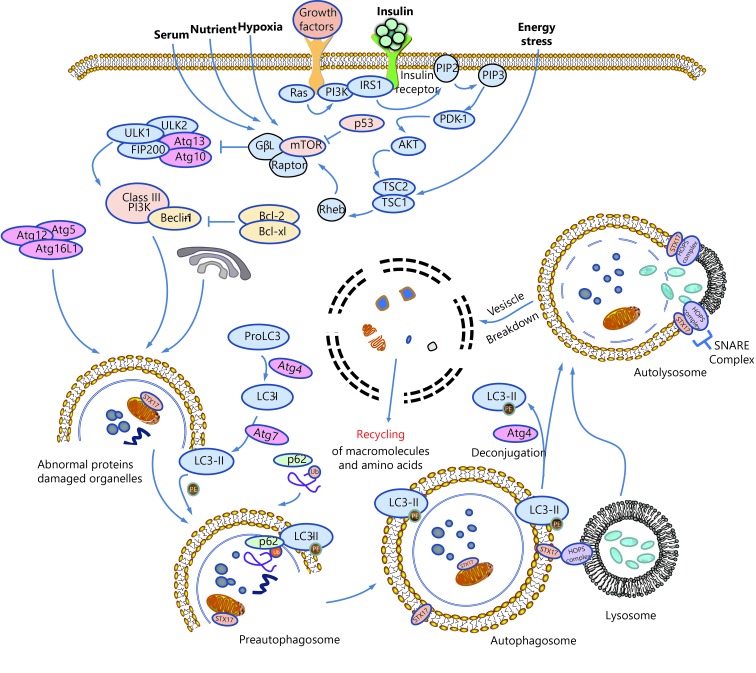

A schematic summarizing the process of autophagy is shown in Figure 1. Morphologically, during the process of autophagy, a preautophagosome first appears in the cytoplasm and gradually develops into an autophagosome, a double-membraned vacuole that contains denatured and necrotic organelles. The outer membrane of the autophagosome fuses with the lysosomal membrane, while the inner membrane and its encapsulated substances enter the lysosomal cavity and are degraded by activated lysosomal hydrolases. This kind of lysosome that fuses with intracellular components is called the autolysosome4.

1.

Schematic overview of autophagy.

Mechanism of autophagy

Autophagy is a continuous and dynamic process that is tightly controlled by autophagy-related genes (Atg). The formation of autophagosomes in mammalian cells consists of two ubiquitin-like modification processes involving autophagy-related protein Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg10, Atg12, and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3), among which Atg12-conjugation and LC3-modification play the most crucial roles. Atg12-conjugation is associated with the formation of preautophagosomes, while LC3-modification is essential for the formation of autophagosomes19. As shown in Figure 1, Atg12 is first activated by Atg7, transported to Atg10, and then combines with Atg5 to form preautophagosomes with the help of Atg16L. In the process of LC3-modification, proLC3 is first processed into LC3-I in the present of Atg4, activated by Atg7, transported to Atg3, and then processed into LC3-II, the membrane-bound form localized on preautophagosomes and autophagosomes. P62, also known as sequestosme1 (SQSTM1), is a ubiquitin-binding protein that is involved in both the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy20. In the process of autophagic turnover of protein aggregates, p62 binds to both polyubiquitinated proteins and LC3, promoting the formation of autophagosomes and the degradation of these proteins21.

The mTOR protein forms two distinct functional complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, and it functions as a negative regulator of autophagy. Under nutrient-rich conditions, mTORC1 suppresses autophagy by directly binding and phosphorylating ULK122. When the cell is stimulated by starvation or rapamycin, ULK1 undergoes rapid dephosphorylation, and activated ULK1 induces Atg13 phosphorylation and autophagy22,23.

PI3Ks and their lipid products are important modulators of phagosome maturation and autophagy24. Mammalian PI3Ks are divided into three classes. Class I PI3Ks inhibit autophagy mainly through the PI3K-Akt-TSCl/TSC2-mTOR pathway25,26. Details are presented in Figure 1. The formation of autophagosomes also depends on the activation of Class III PI3Ks and Beclin-127. According to a recent study, S14161, a pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, induces autophagy by enhancing the formation of Beclin-1/Vps34 complex, indicating that the Beclin-1 signaling pathway is also downstream of Class I PI3K28.

Autophagy and drug resistance in cancer

As previously stated, autophagy is a process of cellular self-degradation that plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis when cells are confronted with metabolic stress. Based on accumulating evidence, autophagy and drug resistance in cancer are closely linked29–31. On one hand, one of the most common mechanisms by which cancer cells develop drug resistance is due to apoptosis resistance32, while autophagy is capable of suppressing apoptosis induced by anti-tumor drugs and further promotes drug resistance29. Additionally, autophagy eliminates dysfunctional proteins and organelles, protecting cancer cells treated with cytotoxic agents30. On the other hand, autophagy also exerts anti-tumor effects through as yet uncharacterized mechanisms. Autophagy may reverse drug resistance in apoptosis-tolerant cancer cells by triggering autophagic cell death through a process termed autosis14,33.

The functional interaction between autophagy and apoptosis is regulated by complex networks between multiple pathways. Meanwhile, the mechanism by which cancer cells develop drug resistance involves various factors that have not been completely elucidated. Therefore, therapeutic targeting of autophagy in cancer is sometimes viewed as controversial and more studies are needed in the future.

Ferroptosis overview

In 2003, a new compound, erastin, was reported to selectively kill oncogenic RAS mutant tumor cell lines34. Unexpectedly, erastin-induced cell death does not present classic features of the apoptotic process, such as caspase3 activation, cell shrinkage, chromatin fragmentation, or the formation of apoptotic bodies34. Soon afterward, Yang35 and Yagoda36 found that such cell death is associated with increased levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and can be prevented by iron chelating agents. Meanwhile, Yang35 discovered that another compound, RAS-selective-lethal compound 3 (RSL3), was capable of activating a similar death pathway. In 2012, Dixon et al.9 officially named this form of cell death ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic cell death. Based on electron microscopy findings, the mitochondria shrink significantly and membrane density increases during the process of ferroptosis; these features are not observed in apoptosis and autophagy37.

Mechanism of ferroptosis

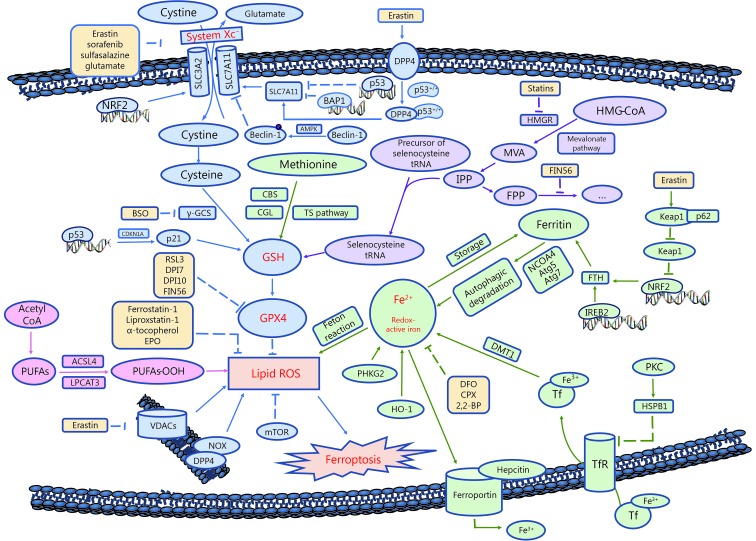

Ferroptosis is characterized by the overwhelming accumulation of lethal intracellular lipid ROS9. When the antioxidant capacity of cells decreases, lipid ROS accumulate within cells, which induces oxidative cell death, or ferroptosis38. Ferroptosis is pivotally controlled by the System Xc-/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis39. Meanwhile, metabolic pathways, such as lipid synthesis, iron metabolism, and the mevalonate pathway, also play important roles, as shown in Figure 2.

2.

Schematic overview of ferroptosis.

System Xc-

System Xc-, a heterodimer composed of SLC7A11 and SLC3A240, is a cystine/glutamate transporter that mediates the cellular uptake of cystine in exchange for intracellular glutamate41. Inhibition of System Xc- by erastin or its commonly known inhibitor, sulfasalazine (SAS), suppresses cystine uptake and glutathione (GSH) synthesis9. GPX4, the GSH-dependent lipid hydroperoxidase, catalyzes the degradation of hydrogen peroxide and inhibits the production of lipid ROS42. In conclusion, erastin and sulfasalazine decrease GPX4 activity by inhibiting System Xc-, thus reducing the cellular antioxidant capacity and inducing oxidative cell death.

GSH synthesis

GSH synthesis requires the participation of glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) (formerly known as γ–glutamyl cysteine synthetase, γ-GCS)43. Buthionine-(S, R)-sulfoximine (BSO) decreases GSH synthesis and triggers ferroptosis by inhibiting GCL44. Another important source of cysteine is the conversion of cystathionine to cysteine via the trans-sulfuration pathway, which partially compensates for the erastin-induced decrease in cystine uptake and cystine depletion45,46.

GPX4

Both erastin and RSL3 increase intracellular lipid ROS levels and induce ferroptosis. Unlike erastin, however, RSL3-induced cell death does not show changes in GSH levels. As shown in the 2014 study by Yang et al.44, GPX4 is the target protein of RSL3. Other compounds, such as DPI7 and DPI10, also act directly on GPX4 and suppress its activity. Furthermore, the mevalonate (MVA) pathway acts on GPX4 by regulating the maturity of selenocysteine tRNA. Selenocysteine is a component of the GPX4 active site, and its insertion into GPX4 requires a special transporter – selenocysteine tRNA47. Modulators of the MVA pathway, such as statins and FIN56, are proposed to positively regulate ferroptosis48,49.

PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cell membranes undergo a series of reactions to form lipid ROS43,49. In the presence of iron, lipid hydroperoxides generated by PUFAs produce toxic lipid free radicals. Moreover, these free radicals transfer protons near PUFAs, initiating a new round of lipid oxidation reactions and further inducing oxidative damage to the cell50. FA synthesis involves multiple metabolic pathways and regulators. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) are lipid metabolism-associated genes. ACSL4 acylates arachidonic acid (AA), while LPCAT3 catalyzes the insertion of acylated AA into membrane phospholipids. Studies found that the deletion of these two genes prevented RSL3-induced ferroptosis51, indicating that a substantial amount of membrane lipid PUFAs is required to induce ferroptosis.

Redox-active iron

The induction of ferroptosis requires the presence of iron. Both lipophilic iron chelators (e.g., ciclopirox olamine, and 2,2-BP) and membrane impermeable iron chelators (e.g., DFA) have been proven to inhibit ferroptosis43. Ferritin is the main intracellular protein that stores iron, and its related genes, ferritin light chain (FTL) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1), regulate iron storage52. Inhibition of the major transcription factor in iron metabolism – iron response element binding protein 2 (IREB2) – increases the expression of FTL and FTH1 and leads to the suppression of erastin-induced ferroptosis9. Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)54, transferrin (Tf) and transferrin receptor (TfR)53,54 are other sources of intracellular iron, while the iron transport protein, ferroportin-1 (FPN), removes iron out of from cells55. These proteins are all involved in regulating ferroptosis by modulating iron metabolism and transportation. See Figures 2 and 3 for additional details.

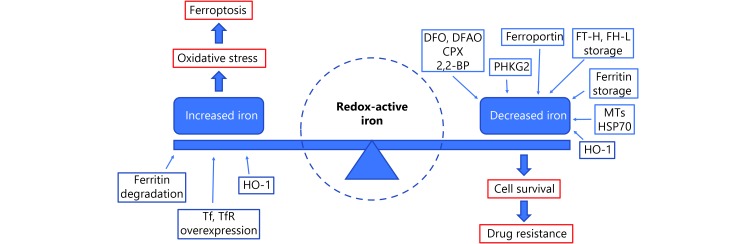

3.

The role of Redox-active iron in ferroptosis and drug resistance.

Ferroptosis and drug resistance in cancer

Iron metabolism

An article published in 1993 showed that drug-resistant cells expressed more TfR than drug-sensitive cells, and the downregulation of TfR reversed drug resistance in cancer56. For instance, TfR is expressed at significantly higher levels in CCRF-CEM and K562 leukemia cells than in normal cells57. The combination of anti-tumor drugs and TfR targeting strategies is highly effective in overcoming the resistance of K562 cells to DOX and VER58. A similar phenomenon also exists in endocrine therapy-resistant breast cancer cells, where TfR (CD71) expression is remarkably increased at both mRNA and protein levels59. Transferrin (Tf), the ligand for TfR, reduces the artemisinin (ART) IC50 in multidrug-resistant H69VP SCLC cells to near drug-sensitive levels60. Similarly, Ma et al.55,61 discovered that treating breast cancer cells with lapatinib in combination with siramesine, a lysosome disrupting agent, upregulated Tf and downregulated FPN, thus significantly increasing intracellular iron and inducing ferroptotic cell death. Based on these findings, strategies that target Tf might be a promising method to reverse drug resistance in tumors.

Ferritin is the major intracellular protein that stores iron, and its upregulation has been observed in multiple drug-resistant tumors62,63. Nuclear ferritins protect DNA from damage induced by DNA-alkylating chemotherapeutic drugs, while downregulation of ferritin sensitizes tumor cells to oxidative damage and increases drug sensitivity63,64. Furthermore, ovarian tumor initiated cells (TICs) express lower levels of FPN and higher levels of TfR1 and exhibit enhanced sensitivity to erastin. TICs are believed to represent a small pool of treatment-refractory cells that contribute to drug resistance and tumor recurrence. Thus, strategies targeting ferroptosis by modulating iron levels are expected to solve this clinical problem65. In general, we conclude from the results described above that available redox-active iron is the basis for ferroptosis and its upregulation is one of the most important causes for drug resistance in multiple cancers (see Figure 3 for details).

System Xc-

System Xc-, another protein important for ferroptosis induction, has increased expression in many drug-resistant cancer cells41,66–69. Various stress conditions, including amino acid deprivation, electrophilic agents, oxidative stress, and glucose starvation, activate System Xc- in an NRF2- and ATF4-dependent manner70,71. Moreover, System Xc- is also regulated by tumor suppressors p53 and BAP1 (BRCA1-associated protein1) through the repression of SLC7A11 expression72–74. Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor, has also been discovered to induce ferroptosis by blocking System Xc-9. As sorafenib is a clinically approved anti-cancer drug and an efficient ferroptosis inducer, the application of this compound to drug-resistant cancers is worth further study. In conclusion, because System Xc- is upregulated in cancer cells, inhibition of System Xc- expression is a promising therapeutic strategy to increase anti-tumor drug sensitivity.

NRF2 pathway

In addition to blocking System Xc-, sorafenib also prevents NRF2 degradation and enhances NRF2 nuclear accumulation by inactivating Kelch-like ECH-associated protein1 (Keap1)75. Nuclear NRF2 promotes the transcription of its downstream targets such as SLC7A11, G6PD, and FTH176. These genes are involved in lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism, and their transcriptional activation negatively regulates ferroptosis. Inhibition of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway significantly enhances the anti-cancer activity of erastin and sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells77. Activation of the NRF2-ARE (antioxidant response element) pathway is also observed in head and neck cancer cell lines that are resistant to cisplatin and artesunate, while inhibition of this pathway reverses ferroptosis resistance and increases drug sensitivity78,79.

Lipid ROS

GSH depletion results in the iron-dependent accumulation of lipid ROS, which is suppressed by antioxidants such as ferrostatin-1 and 6-NA9,80. Increased activity of GSH and GSH-S-transferase (GSTs) is observed in high-grade soft tissue sarcoma (STS) treated with doxorubicin81, as well as in rhabdomyosarcoma tumors resistant to DOX, topotecan and vincristine82. ROS is regarded as the executioner of death in cancer cells undergoing ferroptosis9, thus increasing the source of lipid ROS or reducing the antioxidant capacity of cancer cells is a promising approach to combat drug resistance.

Treatments targeting ferroptosis are expected to be a potential therapeutic strategy to reverse multiple drug resistance in cancers. The possible pathways involved are summarized in Table 1, and the currently known inducers and suppressors of ferroptosis are described in Table 2.

1.

Ferroptosis as a potential therapeutic target in various cancers

| Cancer type | Drug | Pathway (targets) | Ferroptosis component | Reference |

| Breast cancer | Tamoxifen | Transferrin receptor | Iron metabolism | 59 |

| Breast cancer | Faslodex | Transferrin receptor | Iron metabolism | 59 |

| Breast cancer | Artemisinin | Transferrin | Iron metabolism | 83 |

| Breast cancer | Doxorubicin | Ferritin | Iron metabolism | 64 |

| Breast cancer | Doxorubicin | Ferritin | Iron metabolism | 63 |

| Breast cancer | Cisplatin | Ferritin | Iron metabolism | 63 |

| Breast cancer | Siramesine and Lapatinib | Ferritin | Iron metabolism | 61 |

| Breast cancer | Ironomycin/AM5 | Ferritin | Iron metabolism | 84 |

| Breast cancer | Doxorubicin | Ferroportin-1 | Iron metabolism | 85 |

| Breast cancer | Siramesine and Lapatinib | Ferroportin-1 | Iron metabolism | 55 |

| Breast cancer | Etoposide | Iron chelator | Iron metabolism | 86 |

| Erythroleukemia | Doxorubicin | Transferrin | Iron metabolism | 87 |

| Promyelocytic leukemia | Doxorubicin | Transferrin | Iron metabolism | 86 |

| Leukemia | Doxorubicin | Transferrin receptor | Iron metabolism | 58 |

| Leukemia | Artemisinin | Transferrin receptor | Iron metabolism | 57 |

| Leukemia | Artemisinin | Transferrin receptor | Iron metabolism | 88 |

| Myeloma | Bortezomib | Ferritin | Iron metabolism | 62 |

| Ovarian cancer | Platinum | Ferroportin-1, transferrin receptor | Iron metabolism | 65 |

| Small-cell lung cancer | Artemisinin | Transferrin | Iron metabolism | 60 |

| Epidermoid carcinoma | Vinblastine | Iron chelator | Iron metabolism | 85 |

| Glioma | Carmustine | H-ferritin | Iron metabolism | 89 |

| Glioma | Temozolomide | System Xc- | System Xc- | 90 |

| Glioma | Sulfasalazine | System Xc- | System Xc- | 90 |

| Glioma | Temozolomide | AFT4--System Xc- | System Xc- | 71 |

| Glioma | Pseudolaric acid B | p53--System Xc- | System Xc- | 73 |

| Melanoma | Vemurafenib | System Xc- | System Xc- | 68 |

| Head and neck cancer | Cisplatin | System Xc- | System Xc- | 66 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Sorafenib | System Xc- | System Xc- | 91 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Gemcitabine | System Xc- | System Xc- | 41 |

| Head and neck cancer | Dihydroartemisinin | GPX4† | Lipid ROS and antioxidants | 92 |

| Head and neck cancer | Sulfasalazine | Lipid ROS | Lipid ROS and antioxidants | 93 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Sorafenib | Lipid ROS | Lipid ROS and antioxidants | 94 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Gemcitabine | Lipid ROS | Lipid ROS and antioxidants | 95 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Doxorubicin | GSH‡ | Lipid ROS and antioxidants | 96 |

| Small-cell lung cancer | Cisplatin | GSH‡ | Lipid ROS and antioxidants | 97 |

| Head and neck cancer | Artesunate | NRF2-ARE§ pathway | NRF2 pathway | 77 |

| Head and neck cancer | Cisplatin | NRF2-ARE§ pathway | NRF2 pathway | 78 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Sorafenib | p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway | NRF2 pathway | 76 |

| Ovarian cancer | Cisplatin | Unknown | Others | 67 |

| Head and neck cancer | Sulfasalazine | ALDHs¶ | Others | 98 |

| † GXP4: glutathione peroxidase 4; ‡ GSH: glutathione; § NRF2-ARE: nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2) like 2 - antioxidant response element; ¶ ALDHs: aldehyde dehydrogenases. | ||||

2.

Inducers and suppressors of ferroptosis

| Inducer | Suppressor | ||||||

| System Xc- inhibitor | GPXs inhibitor | GSH Sythesis inhibitor | Ferritinophagy activator | Others | Iron chelator | Antioxidant | |

¶ RSL3: RAS-selective-lethal compound 3; † BSO: buthionine-(S, R)-sulfoximine; ‡ FAC: ferric ammonium citrate; § DFOM: desferrioxamine mesylate; ∫CPX: 8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dimethylxanthine;

BHT: butylated hydroxytoluene; BHT: butylated hydroxytoluene;

HO-1: heme oxygenase-1. HO-1: heme oxygenase-1.

| |||||||

| Erastin9 | RSL3¶9 | Statins48 | DpdtC99 | Dihydroartemisinin92 | Deferoxamine35 | Ferrostatin-1100 | |

| Sulfasalazine9 | DPI79 | BSO†44 | FAC‡101 | Artemisinin87 | DFOM§35 | Liproxstatin-1100 | |

| Sorafenib91 | DPI109 | Altretamine35 | CN-A and PEITC95 | Dp44mT85 | α-tocopherol102 | ||

| Glutamate9 | FIN5649 | PEBP1103 | 2,2-BP9 | Erythropoietin104 | |||

| Lanperisone38 | ML16038 | Ardisiacripsin B103 | CPX∫105 | Trolox38 | |||

| SRS13-4538 | Acetaminophen35 | BHT

44 44

|

|||||

HO-1

106 106

|

Cycloheximide38 | ||||||

| Aminooxyacetic acid38 | |||||||

| β–mercaptoethanol107 | |||||||

| XJB-5-131108 | |||||||

| JP4-039108 | |||||||

| Zileuton35 | |||||||

| Baicalein107 | |||||||

Interaction between autophagy and ferroptosis

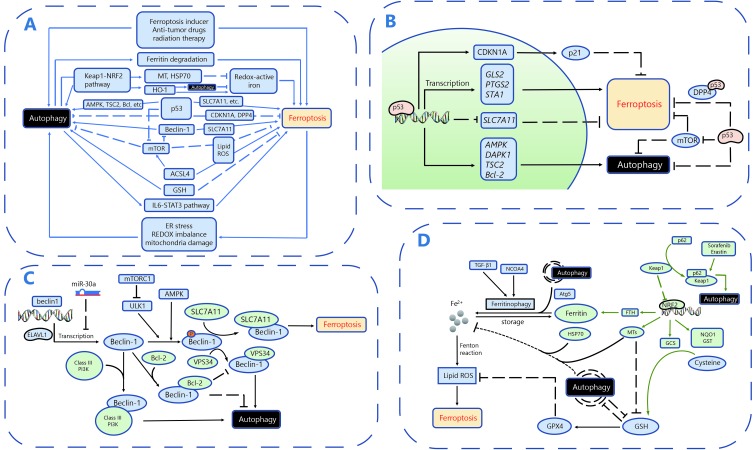

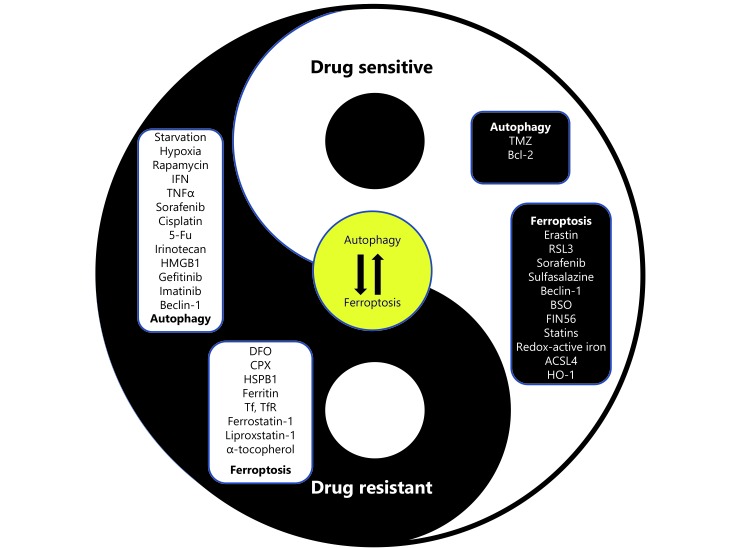

Accumulating studies have revealed the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis. In this section, we will review these published pathways and molecules to potentially improve our understanding and use of this potential strategy to conquer drug resistance in cancer. A schematic diagram summarizing the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis is shown in Figure 4.

4.

Crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy. A. Overall mechanisms involving crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis. B. The roles of p53 in the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis. C. The roles of Beclin-1 in the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis. D. Other critical molecules and pathways involved in the the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis.

Autophagy regulates ferroptosis by ferritin degradation

Ferroptosis has recently been described as an autophagic cell death process, and autophagy plays an essential role in the induction of ferroptosis by regulating cellular iron homeostasis and ROS generation15,109. Ferritin is the major intracellular protein that stores iron. Reactive iron (Fe2+) induces toxic Fenton-type oxidative reactions, while the unreactive state (Fe3+) stored in ferritin is less harmful52. Under ferroptosis-inducing conditions, such as erastin treatment, autophagy is activated, as confirmed by the conversion of LC3I to LC3II and GFP-LC3 puncta formation109. Autophagy promotes ferritin degradation and thus leads to the release of chelated iron in ferritin, a process known as ferritinophagy. An increase in the cellular labile iron pool induces oxidative stress and eventually results in the occurrence of ferroptosis109. Knockout or knockdown of Atg5 suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis by decreasing intracellular ferrous iron levels, further indicating that autophagy is essential for ferritin degradation and ferroptosis induction15. Quantitative proteomics identified nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Overexpression of NCOA4 increases ferritin degradation and promotes ferroptosis, whereas suppression of NCOA4 expression with multiple shRNAs followed by iron chelation exerts the opposite effect110. On the other hand, ferritin that is not completely saturated with iron helps to preserve a relatively low redox-active iron concentration in the lysosome. Therefore, autophagy of non-iron-saturated ferritin might decrease the sensitivity of the lysosome to oxidative stress, which protects the cell from oxidative injury111. Interestingly, ferroptosis and autophagy were recently shown to induce cell death independently and at different times after siramesine and lapatinib treatment in breast cancer cells61. However, researchers do observe increased ferritin degradation promoted by autophagy. Further studies are needed to better illustrate the cooperation between ferroptosis and autophagy in inducing cell death.

Regulators of ferroptosis are transported to the lysosome and perform their functions via an autophagic process

According to Sun et al.75,77, the Keap1-NRF2 pathway is activated by sorafenib treatment and the expression of its downstream genes, such as Metallothionein-1G (MT1G), is subsequently increased. Metallothioneins (MTs), a class of iron-binding proteins, suppress lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) and protect against various harmful conditions. The upregulation of MTs in combination with starvation-activated autophagy of MTs suppresses the toxicity of Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a powerful inducer of apoptosis/necrosis, and cycloheximide (CHX), the TNF sensitizer, in hepatoma cells112. Mechanistically, autophagic flux redirects cytoplasmic MTs to the lysosomal compartment where they chelate redox-active iron in the lysosome, thus protecting cells from TNF and CHX toxicity. Therefore, we hypothesize that both autophagy and ferroptosis are involved in drug resistance mediated by MTs. Chemotherapy treatment regulates the expression of MTs. MTs are then transferred to the lysosome through the autophagic process. Next, MTs chelate intralysosomal redox-active iron and protect cells from ferroptosis. Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) also stabilizes lysosomes under oxidative stress. Autophagy of HSP70 may well mediate the transformation of lysosomal redox-active iron into a non-redox-active form and suppress ferroptosis, similar to autophagy of MTs113.

Keap-NRF2 pathway

As mentioned above, activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway plays an important role in sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in HCC cells77. Meanwhile, the Keap1-NRF2-ARE pathway protects cells from oxidative stress in concert with autophagy114,115. Based on these findings, Keap1-NRF2 might serve as a crucial link between ferroptosis and autophagy.

ELAV1

The RNA-binding protein ELAVL1/HuR plays an important role in regulating ferroptosis in subjects with liver fibrosis116. Ferroptosis-inducing compounds increase levels of the ELAVL1 protein by inhibiting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Meanwhile, upregulated ELAVL1 promotes autophagosome generation and autophagic flux by binding to Beclin-1 mRNA and increasing its stability. The deletion of ELAVL1 increases Beclin-1 mRNA stability and prevents ELAVL1-induced ferroptosis, indicating that autophagy is required for the induction of ferroptosis. These results reveal a new mechanism underlying the relationship between ferroptosis and autophagy. Further investigations are required to determine whether ferritin degradation or activation of the Keap1-NRF2 pathway is involved in this process.

HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), one source of intracellular iron, promotes ferroptosis by inducing lipid peroxidation34. However, Zukor et al.117 found that HO-1 promotes mitochondrial macroautophagy and the trapping of redox-active iron, which might negatively regulate the induction of ferroptosis. Given these contradictory results, further studies are needed to explore the direct role of HO-1 in the interaction between autophagy and ferroptosis.

p53

P53, the best-characterized human tumor suppressor protein, regulates autophagy in a dual fashion. On the one hand, nuclear p53 stimulates autophagy by binding to the promoter region of genes encoding proautophagic modulators such as AMPK, DAPK-1, TSC2 and members of the Bcl-2 family118. In addition, p53 activation inhibits mTOR activity and subsequently promotes autophagy119. On the other hand, p53 in the cytoplasm blocks autophagy via hitherto uncharacterized mechanisms118. Interestingly, nuclear p53 was also recently shown to stimulate ferroptosis in a transcription-dependent manner, inhibiting cystine uptake and sensitizing cells to ferroptosis by repressing the expression of SLC7A11, the gene that encodes System Xc-120. In addition to SLC7A11, several other target genes of p53 have been reported to positively regulate ferroptosis, including GLS2, PTGS2, and STA1121. However, the stabilization of wild-type p53 was recently discovered to delay the onset of ferroptosis by upregulating the expression of its downstream target CDKN1A (encoding p21)122. Furthermore, p53 also inhibits ferroptosis in a transcription-independent manner by binding to the modulator of ferroptosis and lipid metabolism -- dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP4)123. Notably, p53 plays a dual regulatory role in both autophagy and ferroptosis, prompting us to question whether this role remains the same in the interaction between autophagy and ferroptosis.

Beclin-1

Beclin-1, the key protein involved in macroautophagy/autophagy, induces lipid peroxidation and promotes ferroptosis by blocking the activity of System Xc- through direct interaction with SLC7A11124. Specifically, activated AMPK phosphorylates Beclin-1 at Ser90/93/96, which is required for the formation of the Beclin-SLC7A11 complex125. Beclin-1 is well known to play essential roles in regulating autophagy and apoptosis. For example, Beclin-1 interacts with Class III PI3Ks to promote the formation of autophagosomes; the BH3 structure of the Beclin-1 protein binds to the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2/Bcl-xl to inhibit the occurrence of autophagy126. Different Beclin-1 complexes are involved in different pathways and exert different effects on cell death, such as pro-survival effects via autophagy or pro-death effects via ferroptosis. However, the underlying regulatory mechanisms are not yet well understood. Therefore, explorations of how the upstream signaling pathway regulates Beclin-1 to determine its preferred interaction with SLC7A11, Class III PI3Ks, or Bcl-2/Bcl-xl, will be very important.

GSH

GSH is a necessary cofactor for GPX4 and occupies a vital position in ferroptosis42. In addition, according to recent research, GSH depletion also induces autophagy, as reflected by increased LC3 expression, numbers of autophagic vacuoles and autophagic flux103. GSH depletion-dependent cell death has been prevented by selective ferroptosis inhibitors (e.g., Fer-1 and Lip-1), as well as autophagy inhibitors (e.g., Baf-A1 and 3-MA). Interestingly, autophagy significantly decreases intracellular GSH levels and vice versa127. Presumably, the mutual effects of GSH and autophagy may modulate the induction of ferroptosis.

ER stress

Inhibition of System Xc- by ferroptotic agents (e.g., erastin and sorafenib) induces the activation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response that is modulated by PERK-eIF2α (eukaryotic initiation factor 2α)-ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4) pathway128. On the contrary, another study also finds that ATF4 overexpression leads to System Xc- elevation and inhibits TMZ-induced autophagy71. The dual role of ATF4 in ferroptosis needs further illustration. The ferroptotic agent ART promotes the expression of ATF4-dependent genes, such as CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein)129. CHOP binds to the promoter of PUMA (p52 upregulated modulator of apoptosis) and increases the expression of this protein. PUMA interacts with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl, thereby possibly indirectly influencing the induction of autophagy by disassembling the Beclin-1/Bcl-2 complex.

ACSL4

Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), the enzyme involved in arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism, is involved in the mechanism responsible for increased breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Ulises et al.130 identified ACSL4 as a novel activator of the mTOR pathway by showing that it acts on both mTORC1 and mTORC2. ACSL-dependent modulation of phospholipids, particularly AA, were recently shown to be a critical determinant of sensitivity to ferroptosis131,132. Because mTOR protects against excess iron and ferroptosis133, we wondered whether it participates in the ACSL4-mediated modulation of ferroptosis sensitivity.

STAT3 pathway

STAT3 is a positive regulator of ferroptosis in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) by inducing the expression of cathepsin B134, but recent research showed that inhibition of STAT3/GPX4 signaling reactivated ferroptosis and sensitized osteosarcoma cells to cisplatin135. On the other hand, cytoplasmic STAT3 suppresses autophagy by binding to protein kinase B (PKB)136 while autophagy, in turn, promotes IL6-induced phosphorylation of STAT3 and its mitochondrial localization. The underlying roles of STAT3 in the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis are not yet clear and more work is needed.

Crosstalk of autophagy and ferroptosis in drug resistance in cancer

The interaction between autophagy and ferroptosis is illustrated above, and the role of these interactions in the response of cancer cells to anti-cancer drugs is briefly summarized.

Autophagy is a cellular catabolic pathway that is involved in lysosomal degradation and recycling of proteins and organelles and thereby is considered an important survival/protective mechanism for cancer cells in response to metabolic stress or anti-cancer drugs. Because multiple studies have shown that autophagy induces ferroptosis and ferroptosis is generally considered a death-inducing pathway, the intensity of autophagy activity may play a vital role in determining the destination of tumor cells treated with anti-cancer drugs.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated following ER stress induced by cellular nutrient depletion, alterations in the redox state, an imbalance in intracellular calcium levels, or dysfunction of posttranslation modifications, and is capable of inducing autophagy137. Combined with the results that inhibition of System Xc- by ferroptotic agents (e.g., erastin and sorafenib) induces the ER stress response138, we speculate that autophagy is first induced when cells are treated with anti-tumor drugs. Only when autophagy reaches a certain intensity will it trigger ferroptosis. Ferritin degradation, chelation of redox-active iron, lysosomal activity, p53 modulation, and the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway may be involved in the pathway downstream of autophagy that triggers ferroptosis.

Based on the aforementioned molecular connections between autophagy and ferroptosis, the hypothesis that ferroptosis regulates autophagy is reasonable. To our knowledge, direct evidence supporting this hypothesis is very limited. Indeed, iron deprivation has been shown to induce protective autophagy in multiple cell lines treated with anti-tumor drugs, and autophagy induction is reversed by iron supplementation using ferric ammonium citrate (FAC)139, indicating that ferroptosis may also regulate the occurrence of autophagy. During the process of ferroptosis, lysosome function is postulated to be impaired because of lipid peroxidation, thus suppressing autophagy. On the other hand, the intracellular balance of REDOX (e.g., GSH, GPX4, and lipid ROS) is disrupted during the ferroptotic process, which induces mitochondria damage and may well explain the subsequent onset of autophagy.

Autophagy of MTs prevents TNF- and CHX-induced oxidative stress and toxicity in HCC cells, while inhibition of autophagy via Atg7 knockout combined with Mt1a and/or Mt2a silencing abrogates this protective effect and restores the toxicity of TNF and CHX. Presumably, strategies targeting the autophagy of MTs have the potential to reverse drug resistance by promoting the ferroptotic pathway112. Sorafenib resistance in HCC is reported to be associated with the activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway, which plays vital roles in both ferroptosis and autophagy77,112. The knockdown of p62 or inhibition of NRF2 in HCC cells increases the anticancer activity of sorafenib, thus representing a promising strategy to reverse sorafenib resistance.

Conclusions

In this review, we summarize the mechanisms of ferroptosis and autophagy. The effects of most anti-cancer drugs are closely related to the occurrence and regulation of cell death. Autophagy plays an important role in maintaining cell homeostasis by removing excess, dysfunctional or damaged organelles, proteins or pathogens that accumulate in cells. Strategies targeting autophagy are predicted to be a promising modality, while strategies stimulating and inhibiting autophagy are currently under investigation. Ferroptosis consists of a complex set of biochemical reactions involving multiple signaling pathways and the regulation of different genes. The discovery of ferroptosis provides new insights into how tumor cells respond to anti-cancer drugs and provides new approaches to overcome drug resistance in cancer. Autophagy has recently been shown to play an essential role in the induction of ferroptosis. Here, conclusions from relevant studies have been presented and the crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy is summarized.

Most existing studies suggest that autophagy promotes drug resistance, while ferroptosis is generally considered to reverse drug resistance in cancer. Therefore, a remaining question is under what circumstances is the balance between ferroptosis and autophagy more biased to ferroptosis to combat drug resistance. More specifically, an unsolved issue is how the cancer cells ‘decide’ to respond to similar stimuli (anti-cancer drugs) by preferentially undergoing ferroptosis or autophagy. Here, we first propose the crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy as a novel and important target for the management of drug resistance in cancer (Figure 5). Autophagy also exerts its anti-tumor effects via hitherto uncharacterized mechanisms. Based on the data described above, autophagy may induce cell death and reverse drug resistance by promoting ferroptosis, at least in part by inducing ferritin degradation. Conversely, prolonged iron-mediated ROS generation can induce autophagy, which may function as a feedback loop to further induce ferroptosis until cell death occurs. Based on the currently available evidence, we suggest that treatments manipulating the intensity of autophagy to the point where ferroptosis is induced might be a potential therapeutic strategy. This fine-tuned switch depends on the fully delineated molecular mechanism.

5.

Fine-tune switch between autophagy and ferroptosis in drug resistance.

Additional studies are still needed to determine how ‘ferroptotic’ and ‘autophagic’ processes work alone or synergistically to improve the prognosis of patients with cancer. Actually, many other processes, such as p53-mediated pathways, fatty acid metabolism, iron metabolism, and mitochondrial membrane formation, require the participation of both autophagy and ferroptosis. Once the balance of autophagy and ferroptosis is shifted, the cell may be predisposed to drug resistance. However, the specific interaction between ferroptosis and autophagy is not clearly understood. Therefore, future studies are needed to further explore the underlying mechanisms and related signaling pathways.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81602471, 81672729, 81672729, 81874380 and 81672932), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants (Grant No. LY19H160055, LY19H160059), by Zheng Shu Medical Elite Scholarship Fund, by grant from sub-project of China National Program on Key Basic Research Project (973 Program) (Grant No. 2014CB744505), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. LR18H160001), Zhejiang Province Medical Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2017RC007), Talent Project of Zhejiang Association for Science and Technology (Grant No. 2017YCGC002), Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Project of TCM (Grant No. 2019ZZ016).

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

Contributor Information

Linbo Wang, Email: linbowang@zju.edu.cn.

Jichun Zhou, Email: jichun-zhou@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG Cancer drug resistance: An evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:714–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pommier Y, Sordet O, Antony S, Hayward RL, Kohn KW Apoptosis defects and chemotherapy resistance: Molecular interaction maps and networks. Oncogene. 2004;23:2934–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammad RM, Muqbil I, Lowe L, Yedjou C, Hsu HY, Lin LT, et al Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35:S78–103. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klionsky DJ, Emr SD Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 2000;290:1717–21. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, et al The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chude CI, Amaravadi RK Targeting autophagy in cancer: Update on clinical trials and novel inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1279. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozpolat B, Benbrook DM Targeting autophagy in cancer management-strategies and developments. Cancer Manag Res. 2015;7:291–9. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S34859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:528–42. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linkermann A, Skouta R, Himmerkus N, Mulay SR, Dewitz C, De Zen F, et al Synchronized renal tubular cell death involves ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16836–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415518111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie BS, Wang YQ, Lin Y, Mao Q, Feng JF, Gao GY, et al Inhibition of ferroptosis attenuates tissue damage and improves long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:465–75. doi: 10.1111/cns.2019.25.issue-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masaldan S, Bush AI, Devos D, Rolland AS, Moreau C Striking while the iron is hot: Iron metabolism and Ferroptosis in neurodegeneration. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:221–33. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu B, Chen XB, Ying MD, He QJ, Cao J, Yang B The role of ferroptosis in cancer development and treatment response. Front Pharmacol. 2018;8:992. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang R, Tang DL Autophagy and ferroptosis-what is the connection? Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:153–9. doi: 10.1007/s40139-017-0139-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou W, Xie YC, Song XX, Sun XF, Lotze MT, Zeh III HJ, et al Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 2016;12:1425–8. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1187366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klionsky DJ Autophagy revisited: A conversation with Christian de Duve. Autophagy. 2008;4:740–3. doi: 10.4161/auto.6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen GH, et al Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi AMK, Ryter SW, Levine B Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:651–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1205406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E LC3 conjugation system in mammalian autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2503–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korolchuk VI, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC A novel link between autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Autophagy. 2009;5:862–3. doi: 10.4161/auto.8840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim PK, Hailey DW, Mullen RT, Lippincott-Schwartz J Ubiquitin signals autophagic degradation of cytosolic proteins and peroxisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20567–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810611105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, et al ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thi EP, Reiner NE Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases and their roles in phagosome maturation. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:553–66. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins PT, Anderson KE, Davidson K, Stephens LR Signalling through Class I PI3Ks in mammalian cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:647–62. doi: 10.1042/BST0340647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilli M, Arko-Mensah J, Ponpuak M, Roberts E, Master S, Mandell MA, et al TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity. 2012;37:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao F, Lv YC, Zhang M, Xie W, Tan YL, Gong D, et al Apelin-13 impedes foam cell formation by activating Class III PI3K/Beclin-1-mediated autophagic pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;466:637–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang SY, Li J, Du YY, Xu YJ, Wang YL, Zhang ZB, et al The Class I PI3K inhibitor S14161 induces autophagy in malignant blood cells by modulating the Beclin 1/Vps34 complex. J Pharmacol Sci. 2017;134:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu YL, Jahangiri A, DeLay M, Aghi MK Tumor cell autophagy as an adaptive response mediating resistance to treatments such as antiangiogenic therapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4294–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N, Zhang M, et al Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: A promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e838. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida GJ Therapeutic strategies of drug repositioning targeting autophagy to induce cancer cell death: from pathophysiology to treatment. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:67. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0436-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gimenez-Bonafe P, Tortosa A, Perez-Tomas R Overcoming drug resistance by enhancing apoptosis of tumor cells. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:320–40. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Levine B Autosis and autophagic cell death: The dark side of autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:367–76. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:285–96. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang WS, Stockwell BR Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:234–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yagoda N, Von Rechenberg M, Zaganjor E, Bauer AJ, Yang WS, Fridman DJ, et al RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature. 2007;447:864–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brigelius-Flohé R, Kipp A Glutathione peroxidases in different stages of carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1555–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu HT, Guo PY, Xie XZ, Wang Y, Chen G Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death, and its relationships with tumourous diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:648–57. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.2017.21.issue-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conrad M, Friedmann Angeli JP Glutathione peroxidase 4(Gpx4) and ferroptosis: what’s so special about it? Mol Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e995047. doi: 10.4161/23723556.2014.995047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Y, Dai ZY, Barbacioru C, Sadée W Cystine-glutamate transporter SLC7A11 in cancer chemosensitivity and chemoresistance. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7446–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo M, Ling V, Wang YZ, Gout PW The xc- cystine/glutamate antiporter: a mediator of pancreatic cancer growth with a role in drug resistance. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:464–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maiorino M, Conrad M, Ursini F GPx4, lipid peroxidation, and cell death: discoveries, rediscoveries, and open issues. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;29:61–74. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao JY, Dixon SJ Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2195–209. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang WS, Sriramaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabil O, Vitvitsky V, Xie P, Banerjee R The quantitative significance of the transsulfuration enzymes for H2S production in murine tissues. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:363–72. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayano M, Yang WS, Corn CK, Pagano NC, Stockwell BR Loss of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CARS) induces the transsulfuration pathway and inhibits ferroptosis induced by cystine deprivation. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:270–8. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumaraswamy E, Carlson BA, Morgan F, Miyoshi K, Robinson GW, Su D, et al Selective removal of the selenocysteine tRNA[Ser]Sec Gene (Trsp) in mouse mammary epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1477–88. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1477-1488.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen JJ, Galluzzi L Fighting resilient cancers with iron. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:77–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimada K, Skouta R, Kaplan A, Yang WS, Hayano M, Dixon SJ, et al Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:497–503. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M, Shchepinov MS, Stockwell BR Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E4966–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603244113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, et al Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:1604–9. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torti FM, Torti S V Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood. 2002;99:3505–16. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bogdan AR, Miyazawa M, Hashimoto K, Tsuji Y Regulators of iron homeostasis: new players in metabolism, cell death, and disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:274–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao MH, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang XJ Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;59:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma S, Henson ES, Chen Y, Gibson SB Ferroptosis is induced following siramesine and lapatinib treatment of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2307. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barabas K, Faulk WP Transferrin receptors associate with drug resistance in cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:702–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Efferth T, Benakis A, Romero MR, Tomicic M, Rauh R, Steinbach D, et al Enhancement of cytotoxicity of artemisinins toward cancer cells by ferrous iron. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:998–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu J, Lu YH, Lee A, Pan XG, Yang XJ, Zhao XB, et al Reversal of multidrug resistance by transferrin-conjugated liposomes co-encapsulating doxorubicin and verapamil. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2007;10:350–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Habashy HO, Powe DG, Staka CM, Rakha EA, Ball G, Green AR, et al Transferrin receptor (CD71) is a marker of poor prognosis in breast cancer and can predict response to tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:283–93. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sadava D, Phillips T, Lin C, Kane SE Transferrin overcomes drug resistance to artemisinin in human small-cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2002;179:151–6. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma S, Dielschneider RF, Henson ES, Xiao W, Choquette TR, Blankstein AR, et al Ferroptosis and autophagy induced cell death occur independently after siramesine and lapatinib treatment in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campanella A, Santambrogio P, Fontana F, Frenquelli M, Cenci S, Marcatti M, et al Iron increases the susceptibility of multiple myeloma cells to bortezomib. Haematologica. 2013;98:971–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.074872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chekhun VF, Lukyanova NY, Burlaka AP, Bezdenezhnykh NA, Shpyleva SI, Tryndyak VP, et al Iron metabolism disturbances in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cells with acquired resistance to doxorubicin and cisplatin. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:1481–6. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shpyleva SI, Tryndyak VP, Kovalchuk O, Starlard-Davenport A, Chekhun VF, Beland FA, et al Role of ferritin alterations in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basuli D, Tesfay L, Deng Z, Paul B, Yamamoto Y, Ning G, et al Iron addiction: A novel therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:4089–99. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roh JL, Kim EH, Jang HJ, Park JY, Shin D Induction of ferroptotic cell death for overcoming cisplatin resistance of head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;381:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sato M, Kusumi R, Hamashima S, Kobayashi S, Sasaki S, Komiyama Y, et al The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system xc- and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin’s cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsoi J, Robert L, Paraiso K, Galvan C, Sheu KM, Lay J, et al Multi-stage differentiation defines melanoma subtypes with differential vulnerability to drug-induced iron-dependent oxidative stress. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:890–904.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Timmerman LA, Holton T, Yuneva M, Louie RJ, Padró M, Daemen A, et al Glutamine sensitivity analysis identifies the xCT antiporter as a common triple-negative breast tumor therapeutic target. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:450–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koppula P, Zhang YL, Zhuang L, Gan BY Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun. 2018;38:12. doi: 10.1186/s40880-018-0288-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen DS, Rauh M, Buchfelder M, Eyupoglu IY, Savaskan N The oxido-metabolic driver ATF4 enhances temozolamide chemo-resistance in human gliomas. Oncotarget. 2017;8:51164–76. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nemade H, Chaudhari U, Acharya A, Hescheler J, Hengstler JG, Papadopoulos S, et al Cell death mechanisms of the anti-cancer drug etoposide on human cardiomyocytes isolated from pluripotent stem cells. Arch Toxicol. 2018;92:1507–24. doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2170-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang ZQ, Ding Y, Wang XZ, Lu S, Wang CC, He C, et al Pseudolaric acid B triggers ferroptosis in glioma cells via activation of Nox4 and inhibition of xCT. Cancer Lett. 2018;428:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang YL, Shi JJ, Liu XG, Feng L, Gong ZH, Koppula P, et al BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:1181–92. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0178-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun XF, Niu XH, Chen RC, He WY, Chen D, Kang R, et al Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:488–500. doi: 10.1002/hep.28574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R, Zhang DD. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2019. (in Press)

- 77.Sun XF, Ou ZH, Chen RC, Niu XH, Chen D, Kang R, et al Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016;63:173–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roh JL, Kim EH, Jang H, Shin D Nrf2 inhibition reverses the resistance of cisplatin-resistant head and neck cancer cells to artesunate-induced ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2017;11:254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shin D, Kim EH, Lee J, Roh JL Nrf2 inhibition reverses resistance to GPX4 inhibitor-induced ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;129:454–62. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.10.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171:273–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hochwald SN, Rose DM, Brennan MF, Burt ME Elevation of glutathione and related enzyme activities in high-grade and metastatic extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:303–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02303579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seitz G, Bonin M, Fuchs J, Poths S, Ruck P, Warmann SW, et al Inhibition of glutathione-S-transferase as a treatment strategy for multidrug resistance in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:491–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Singh NP, Lai H Selective toxicity of dihydroartemisinin and holotransferrin toward human breast cancer cells. Life Sci. 2001;70:49–56. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mai TT, Hamaï A, Hienzsch A, Cañeque T, Müller S, Wicinski J, et al Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat Chem. 2017;9:1025–33. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yalovenko TM, Todor IM, Lukianova NY, Chekhun VF Hepcidin as a possible marker in determination of malignancy degree and sensitivity of breast cancer cells to cytostatic drugs. Exp Oncol. 2016;38:84–8. doi: 10.31768/2312-8852.2016.38(2):84-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Whitnall M, Howard J, Ponka P, Richardson DR A class of iron chelators with a wide spectrum of potent antitumor activity that overcomes resistance to chemotherapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14901–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fritzer M, Barabas K, Szüts V, Berczi A, Szekeres T, Faulk WP, et al Cytotoxicity of a transferrin-adriamycin conjugate to anthracycline-resistant cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:619–23. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ooko E, Saeed MEM, Kadioglu O, Sarvi S, Colak M, Elmasaoudi K, et al Artemisinin derivatives induce iron-dependent cell death (ferroptosis) in tumor cells. Phytomedicine. 2015;22:1045–54. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu XL, Madhankumar AB, Slagle-Webb B, Sheehan JM, Surguladze N, Connor JR Heavy chain ferritin siRNA delivered by cationic liposomes increases sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2240–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sehm T, Rauh M, Wiendieck K, Buchfelder M, Eyüpoglu IiY, Savaskan NE Temozolomide toxicity operates in a xCT/SLC7a11 dependent manner and is fostered by ferroptosis. Oncotarget. 2014;7:74630–47. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lachaier E, Louandre C, Godin C, Saidak Z, Baert M, Diouf M, et al Sorafenib induces ferroptosis in human cancer cell lines originating from different solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:6417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lin RY, Zhang ZH, Chen LF, Zhou YF, Zou P, Feng C, et al Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) induces ferroptosis and causes cell cycle arrest in head and neck carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;381:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim EH, Shin D, Lee J, Jung AR, Roh JL CISD2 inhibition overcomes resistance to sulfasalazine-induced ferroptotic cell death in head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:180–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Louandre C, Ezzoukhry Z, Godin C, Barbare JC, Mazière JC, Chauffert B, et al Iron-dependent cell death of hepatocellular carcinoma cells exposed to sorafenib. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1732–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.v133.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kasukabe T, Honma Y, Okabe-Kado J, Higuchi Y, Kato N, Kumakura S Combined treatment with cotylenin A and phenethyl isothiocyanate induces strong antitumor activity mainly through the induction of ferroptotic cell death in human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:968–76. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fanzani A, Poli M Iron, oxidative damage and ferroptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1718. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guo JP, Xu BF, Han Q, Zhou HX, Xia Y, Gong CW, et al Ferroptosis: A novel anti-tumor action for cisplatin. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:445–60. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Okazaki S, Shintani S, Hirata Y, Suina K, Semba T, Yamasaki J, et al Synthetic lethality of the ALDH3A1 inhibitor dyclonine and xCT inhibitors in glutathione deficiency-resistant cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9:33832–43. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huang TF, Sun YJ, Li YL, Wang TT, Fu Y, Li CP, et al Growth inhibition of a novel iron chelator, DpdtC, against hepatoma carcinoma cell lines partly attributed to ferritinophagy-mediated lysosomal ROS generation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:4928703. doi: 10.1155/2018/4928703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zilka O, Shah R, Li B, Friedmann Angeli JP, Griesser M, Conrad M, et al On the mechanism of cytoprotection by ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 and the role of lipid peroxidation in ferroptotic cell death. ACS Cent Sci. 2017;3:232–43. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang HB, Li Z, Niu JL, Xu YF, Ma L, Lu AL, et al Antiviral effects of ferric ammonium citrate. Cell Discov. 2018;4:14. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0013-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Probst L, Dächert J, Schenk B, Fulda S Lipoxygenase inhibitors protect acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from ferroptotic cell death. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;140:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.06.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sun Y, Zheng YF, Wang CX, Liu YZ Glutathione depletion induces ferroptosis, autophagy, and premature cell senescence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:753. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0794-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Katavetin P, Tungsanga K, Eiam-Ong S, Nangaku M Antioxidative effects of erythropoietin. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007;72:S10–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hao SH, Liang BS, Huang Q, Dong SM, Wu ZZ, He WM, et al Metabolic networks in ferroptosis. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:5405–11. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chang LC, Chiang SK, Chen SE, Yu YL, Chou RH, Chang WC Heme oxygenase-1 mediates BAY 11-7085 induced ferroptosis. Cancer Lett. 2018;416:124–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xie YC, Song XX, Sun XF, Huang J, Zhong MZ, Lotze MT, et al Identification of baicalein as a ferroptosis inhibitor by natural product library screening. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;473:775–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Krainz T, Gaschler MM, Lim C, Sacher JR, Stockwell BR, Wipf P A mitochondrial-targeted nitroxide is a potent inhibitor of ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2016;2:653–9. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gao MH, Monian P, Pan QH, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang XJ Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016;26:1021–32. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mancias JD, Wang XX, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 2014;508:105–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Persson HL, Nilsson KJ, Brunk UT Novel cellular defenses against iron and oxidation: ferritin and autophagocytosis preserve lysosomal stability in airway epithelium. Redox Rep. 2001;6:57–63. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ullio C, Brunk UT, Urani C, Melchioretto P, Bonelli G, Baccino FM, et al Autophagy of metallothioneins prevents TNF-induced oxidative stress and toxicity in hepatoma cells. Autophagy. 2015;11:2184–98. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1106662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kurz T, Brunk UT Autophagy of HSP70 and chelation of lysosomal iron in a non-redox-active form. Autophagy. 2009;5:93–5. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.1.7248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Inoue H, Kobayashi KI, Ndong M, Yamamoto Y, Katsumata SI, Suzuki K, et al Activation of Nrf2/Keap1 signaling and autophagy induction against oxidative stress in heart in iron deficiency. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79:1366–8. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1018125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.E. Habib, K. Linher-Melville, H.X. Lin, G. Singh Expression of xCT and activity of system xc- are regulated by NRF2 in human breast cancer cells in response to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2015;5:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang ZL, Yao Z, Wang L, Ding H, Shao JJ, Chen AP, et al Activation of ferritinophagy is required for the RNA-binding protein ELAVL1/HuR to regulate ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Autophagy. 2018;14:2083–103. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1503146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zukor H, Song W, Liberman A, Mui J, Vali H, Fillebeen C, et al HO-1-mediated macroautophagy: a mechanism for unregulated iron deposition in aging and degenerating neural tissues. J Neurochem. 2009;109:776–91. doi: 10.1111/jnc.2009.109.issue-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O, Malik SA, Kroemer G Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Feng ZH, Zhang HY, Levine AJ, Jin SK The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8204–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jiang L, Kon N, Li TY, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, et al Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gnanapradeepan K, Basu S, Barnoud T, Budina-Kolomets A, Kung CP, Murphy ME The p53 tumor suppressor in the control of metabolism and ferroptosis. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:124. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.A. Tarangelo, L. Magtanong, K.T. Bieging-Rolett, Y. Li, J. Ye, L.D. Attardi, S.J. Dixon p53 Suppresses Metabolic Stress-Induced Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22(569):575. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Xie YC, Zhu S, Song XX, Sun XF, Fan Y, Liu JB, et al The tumor suppressor p53 limits ferroptosis by blocking DPP4 activity. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1692–704. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kang R, Zhu S, Zeh HJ, Klionsky DJ, Tang DL BECN1 is a new driver of ferroptosis. Autophagy. 2018;14:2173–5. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1513758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Song XX, Zhu S, Chen P, Hou W, Wen QR, Liu J, et al AMPK-mediated BECN1 phosphorylation promotes ferroptosis by directly blocking system Xc- activity. Curr Biol. 2018;28:2388–2399.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–80. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Desideri E, Filomeni G, Ciriolo MR Glutathione participates in the modulation of starvation-induced autophagy in carcinoma cells. Autophagy. 2012;8:1769–81. doi: 10.4161/auto.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rahmani M, Davis EM, Crabtree TR, Habibi JR, Nguyen TK, Dent P, et al The kinase inhibitor sorafenib induces cell death through a process involving induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5499–513. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01080-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lee YS, Lee DH, Choudry HA, Bartlett DL, Lee YJ Ferroptosis-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress: crosstalk between ferroptosis and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:1073–6. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Orlando UD, Castillo AF, Dattilo MA, Solano AR, Maloberti PM, Podesta EJ Acyl-CoA synthetase-4, a new regulator of mTOR and a potential therapeutic target for enhanced estrogen receptor function in receptor-positive and -negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42632–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:91–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yuan H, Li XM, Zhang XY, Kang R, Tang DL Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Baba Y, Higa JK, Shimada BK, Horiuchi KM, Suhara T, Kobayashi M, et al Protective effects of the mechanistic target of rapamycin against excess iron and ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;314:H659–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00452.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gao H, Bai YS, Jia YY, Zhao YN, Kang R, Tang DL, et al Ferroptosis is a lysosomal cell death process. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503:1550–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liu Q, Wang KZ. The induction of ferroptosis by impairing STAT3/Nrf2/GPx4 signaling enhances the sensitivity of osteosarcoma cells to cisplatin. Cell Biol Int. 2019. (in Press)

- 136.Kang R, Tang DL, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ AGER/RAGE-mediated autophagy promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis and bioenergetics through the IL6-pSTAT3 pathway. Autophagy. 2012;8:989–91. doi: 10.4161/auto.20258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mahoney E, Byrd JC, Johnson AJ Autophagy and ER stress play an essential role in the mechanism of action and drug resistance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol. Autophagy. 2013;9:434–5. doi: 10.4161/auto.23027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, et al Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife. 2014;3:e02523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yang C, Ma X, Wang Z, Zeng X, Hu Z, Ye Z, et al Curcumin induces apoptosis and protective autophagy in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells through iron chelation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:431–9. doi: 10.2147/DDDT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]