Abstract

Immunotherapy is playing an increasingly important role in the treatment of tumors. Different from the traditional direct killing or excision therapies, immunotherapy depends on autologous immunity to kill tumor cells and tissues by activating or enhancing the body’s immune system. Large numbers of recent studies suggest that low-frequency HIFU can not only enhance the intensity of the body’s anti-cancer immune response, but also improve the efficiency of immunotherapy drug delivery to strengthen the effects of tumor immunotherapy. The focused ultrasound (FUS) destructs the tumor and simultaneously generates tumor debris and tumor-associated antigens, which enhances the immunogenicity of the tumor and stimulates the immune cells, inducing the body’s immune response. Microbubbles are clinically used as a contrast. As a matter of fact, the addition of microbubbles can reinforce the destructive effect of FUS on the tumor and activate a stronger immune response. The combined application of ultrasound and microbubbles can more effectively open the blood brain barrier (BBB), which is beneficial to improving the intake of immune cells or immunotherapy drugs and exerting a positive influence in the lesion area. Currently, microbubbles and nanoparticles are commonly used as gene and drug carriers. Using ultrasound, the immune-related gene or antigen delivery itself can enhance the immune response and improve the efficacy of the immunotherapy.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, low-frequency HIFU, biological effect, immune response, combination therapy

Introduction

Malignant tumors are one of the main diseases that seriously threaten human life. The therapeutic regimens commonly used in clinic include surgery excision, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. As several traditional treatment means, they can treat the primary cancers very well although their drawbacks, such as uncontrolled recurrence and metastasis, cannot be ignored in the practical application, so new cancer therapeutic methods need to be developed urgently1. Immunotherapy, a new type of cancer treatment, does not kill the cancer cells directly. By activating or enhancing the human immune system, the cancer immunotherapy eradicates the cancer cells or tissues depending on autoimmune function2. The target of this method aims at the autologous immune system instead of the cancer cells or tissues3. Cancer immunotherapy has received wide attention because of its great clinical application value4.

The functions of the immune system are mainly manifested in three aspects: defense, stabilization and immune surveillance. Once these functions are out of balance, immunopathological reactions occur5. Immunity of the body can be roughly divided into two kinds: specific immunity and non-specific immunity. Non-specific components need not be exposed beforehand and can respond immediately, effectively preventing the invasion of various pathogens. Specific immunity is developed in the lifetime of the body, and is specific to a certain pathogen6. Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most powerful antigen presenting cells and can efficiently absorb, process and present antigens. Immature DCs have strong migration ability. Mature DCs are at the center of initiation, regulation and maintenance of immune response, and can activate the initial T cells effectively7. An effective immune response includes three procedures8: (1) The DCs capture tumor antigens and process them inside acquiring “mature signals” to activate the immune response for the antigens. (2) DCs present antigenic information to the immature T cells in lymphoid tissue and make them activated, which initiates the specific immunity of the human body. If the DCs presenting antigens are activated by immature signals, the T cells will be induced to create tolerance and consequently resist the immune response. (3) The activated T cells infiltrate the cancer tissue, specifically recognize and kill cancer cells. However, tumor cells possess the nature of immune escape, which makes them avoid the recognition and attack from the immune system by multiple mechanisms, so it is very difficult to eradicate the tumor cells or tissues via the autoimmune system of the human body. Eradication of tumors by means of stimulating the autoimmune system is very promising for anticancer treatment9,10. Currently, tumor immunotherapy mainly includes the following types: enhancing a specific immune system11, tumor vaccine12,13, and adoptive cell transfer (ACT)14.

Ultrasound (US) is defined as a kind of mechanical wave with a frequency over 20 kHz and cannot be detected by the human ear. Aside from medical imaging, US also performed well in the treatment field15. In recent years, many studies indicate that US can be used to promote the anti-cancer immune response of the human body16,17. Focused ultrasound (FUS) can not only create thermal effects but also create mechanical effects or cavitation effects18. The mechanical effects or cavitation effects can increase the anti-cancer immune response of the host body19. Theoretically, these effects can be classified by various US parameters. Cavitation effect, as one of the main mechanical effects, usually occurs at low frequency, high intensity and low duty cycle20. The thermal effects of US often occur at high to moderate intensity and longer duty cycles, and they are generally used in combination with thermosensitive formulations21. Genes and antigens are delivered into the cancer cells or tissues adopting US, which can also activate the anti-cancer immune response20,22. The force exerted on the cell membrane when the microbubble is broken by US directly delivers the substance to the cell, evading each kind of natural barrier23. By this means, one can deliver the cancer antigen and the antigen-encoding gene to immune cells, and the gene that stimulates the immune response can be also delivered to the cancer cells24,25. In this paper, we focused on activation of the anti-tumor immune response using low-frequency high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU).

Low-frequency HIFU

Biological effect of low-frequency HIFU

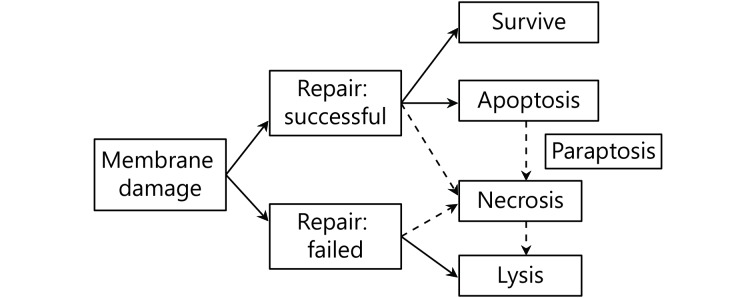

US is generally considered safe for imaging in vivo except for two side effects26-28: thermal and mechanical effects (including sonoporation). However, these two adverse factors for medical imaging are very important to treatment using US. Thermal effects depend on the absorption and accumulation of US energy. The intensity of US, irradiation time, and biological properties of tissue are the main three factors that determines the amount of heat29. The dose of US has a very strong relevance with thermal and mechanical effects. At a low intensity, the ratio of apoptosis to lysis is high, and with the increasing of intensity, lysis becomes predominant over apoptosis and directly causes cell to death. More effective induction of apoptosis is obtained if paused modulation is used with a longer pause than the irradiation time30,31. Accounting for the degree of membrane damage and the capacity of repairing the damage, the death of a cell can be divided into three modes, instant lysis, necrosis, and apoptosis32,33. Figure 1 shows the correlation between the degree of membrane damage caused by US and the corresponding cell death mode34,35. Although some of the damaged cells can successfully self-repair and eventually survive, the process of US irradiation will speed their apoptosis or necrosis36.

1.

Schematic presentation shows the correlation of membrane damage, repair or not, and mode of cell death.

Cavitation effect

The mutual effects between microbubbles and US can easily lead to the cavitation effect37. Microbubbles oscillate symmetrically and linearly at a low powered US field, which implies an opposite tendency of the expansion and compression of a microbubble38. According to the different dynamic behaviors of bubbles, cavitation effects of an US wave can be divided into stable cavitation and inertial cavitation39,40. If the sound intensity of US is weak, the cavitation nucleus is enlarged in the negative pressure stage of sound pressure, and then compressed and reduced in the positive pressure stage41. In other words, the bubble vibrates radially with the balanced radius of sound frequency, which is called steady state cavitation. When the bubbles are compressed under greater pressure to a certain degree, the density of mixed gas inside the bubbles will increase, and it is difficult for the bubbles to continue being compressed42. However, because of the inertial push from the surrounding fluid, the increasing speed of pressure on the bubble wall is still very fast, even surpassing the compression speed of gas inside the bubble. Under such a condition, bubbles will collapse, and the intensity is determined by the inertia of inward-pushing fluid43-45. That is defined as inertial cavitation. The cavitation effect induced by ultrasound-mediated microbubble destruction can directly damage tumor cells and cause obvious ultrastructural changes in tumor neovascularization, which can lead to mitochondrial swelling, myeloid degeneration, and cytoplasmic cavitation of endothelial cells promoting apoptosis46,47. If the cavitation effect is very strong, the walls of small tumor blood vessels can be damaged, which will activate endogenous or exogenous coagulation, and induce thrombosis in blood vessels leading to large-area capillary embolization, blocking the nutritional supply of cancerous tissue cells, and then causing the necrosis of local tumor cell48. Lethal cavitation effects can directly lead to lysis and death of tumor cell. All these provide a theoretical basis for the direct treatments of tumor with ultrasonic microbubbles49-51.

Medical application of low-frequency HIFU

Low-frequency HIFU is widely used clinically for drug delivery, fractured bone and cartilage, nerve stimulation, inflamed tendons, wound healing and ligaments repairing52,53. Compared with the thermal therapy of high-energy US, the non-thermal effects of low-frequency HIFU mainly display in the mechanical stimulation induced by microbubbles, microjets, cavitation and acoustic steaming54-57.In fact, low-frequency FUS can reach deep into the body, which allows precise local treatment and avoids possible disadvantageous side effects to surrounding healthy tissues58. In the nanomedicine field, US stimulus has shown great application prospects such as strengthening extravasation of nanoparticles through blood capillaries, increasing cell membrane permeation, inducing an anti-tumor immunity and so on59,60. Immunotherapy can be classified into active immunotherapy and passive immunotherapy61. Both these two disease treatment strategies can be reinforced by low-frequency HIFU62.

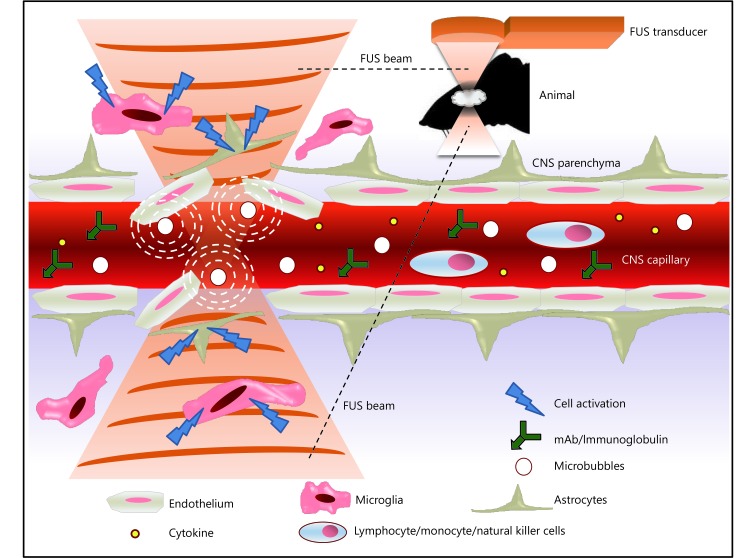

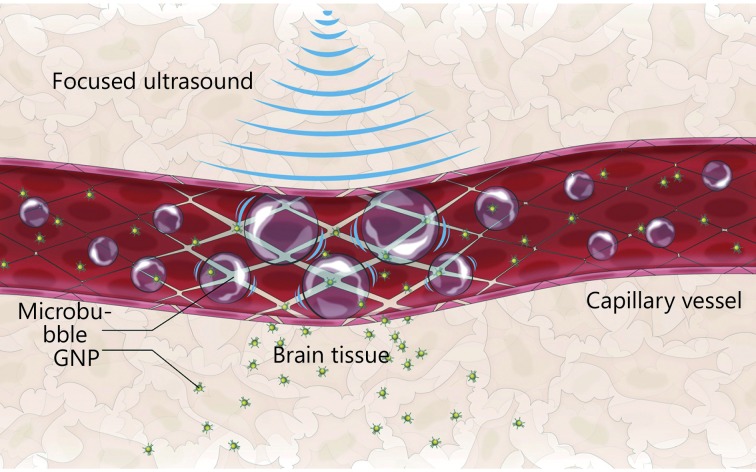

The blood brain barrier (BBB) is a protective barrier system between blood and brain tissue, which is composed of endothelial cells, basal membrane, and glial cell podocytes of brain capillaries63. The BBB allows nutrients needed by brain tissue to pass through, avoids causing brain damage by effectively preventing some foreign bodies and large molecules from passing through, and stopping harmful substances in the blood from invading the brain64. Because of the filtering effect, the BBB affects the deliver ability of drugs and antibodies to brain tissue in almost all intracranial neurological diseases, which limits many drugs and antibodies to low concentrations when entering the brain from the blood, making it difficult to apply the due effect65,66. Currently, there are three main strategies for delivering drugs to the brain67. One is to compound new small molecules that can reach the brain tissue, but only a few diseases can be treated with small molecules. The second is to deliver drugs to the brain by using invasive catheters, but a local puncture can easily damage brain tissue. Third, noninvasive and reversible opening of the BBB, and such an idea has attracted increasing attention. It has been one of the research focuses for scientists to open the BBB by combination of FUS and MB68. The mechanism can be explained as follows69,70: (1) US waves cause microbubbles to expand and collide in capillaries, and the larger microbubbles expand and fill the capillary lumens, leading to the mechanical dilation of blood vessels, which results in the opening of tight connections. (2) Pressure changes in capillaries induce biochemical reactions that trigger the opening of the BBB. (3) Microbubble vibration can reduce local blood flow and lead to transient ischemia, triggering the opening of the BBB. (4) US irradiation causes the burst of micro-bubbles, resulting in local high-speed turbulence and jet flow, and these mechanical effects also participate in the opening of the BBB71. Figure 2 shows the FUS-induced BBB opening and its potential effect in CNS immune modulation and immunotherapy72. So far, there have been many clinical reports about using low-frequency HIFU to open the BBB, such as the delivery of tumor-targeted drugs, gene vectors and analgesics73,74.

2.

Schematic showing FUS-induced BBB opening with its potential effect in CNS immune modulation and immunotherapy. Adapted from reference 72.

Low-frequency HIFU induced tumor immune response

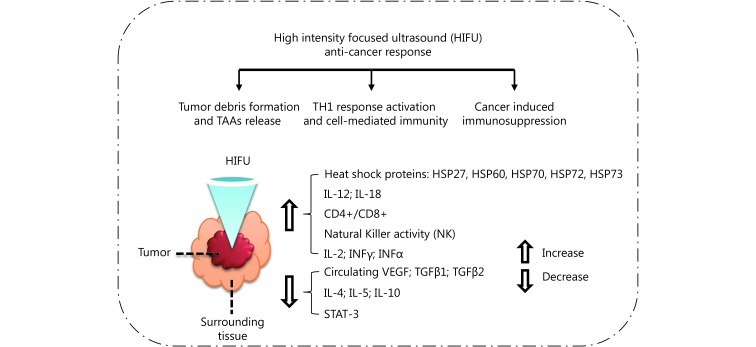

The primary mechanisms of low-frequency HIFU mediated immune response are as follow75,76: (1) After the irradiation of low-frequency HIFU, both the tumor debris and the released relating cancer antigens can work as a cancer vaccine, enhancing the immunogenicity. (2) The treatment of low-frequency HIFU on the tumor lesion can induce Th1 reaction, which leads to significant changes of cellular immunity, strengthening the activity of DC and cytotoxic lymphocytes. (3) The treatment of low-frequency HIFU can balance the immunosuppressive action induced by the tumor microenvironment. The three effectors above can effectively stimulate the anti-cancer immune response of the human body. Currently, there is abundant literature for preparing tumor lysates from tumor samples aiming to activate the anti-tumor response77. The tumor lysates are loaded on cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which will enhance the killing activity aiming to cancer cells. Many literatures have given the detection and analysis methods of related immune parameters, such as cytokine detection, chemokine detection and so on78.

Compared with high-frequency HIFU, low-frequency HIFU can reserve the antigens more efficiently, stimulate the DCs’ infiltration and maturity in situ, which triggers a stronger immune response79. In addition, the different scanning ways of low-frequency HIFU also affect the immunotherapy effect78. In diseased tissue, the sparse scanning mode can reserve antigens better, and be more effective than the intensive scanning mode59,80. Yang et al.81 discovered very early that FUS can stimulate the anti-cancer immune response. They treated neuroblastoma C1300 mice with HIFU, and the same cancer cells were inoculated again in the mice after the ablation of cancer tissue. Comparing with mice that were not inoculated for cancer cells in the initial stage or the mice that were not treated with HIFU, they found that the proliferation rate of the re-inoculated tumor cell after HIFU treatment is significantly decreased. Many subsequent studies also indicated that the tumor debris treated with FUS can induce the tumor specific immune response, so the tumor debris after FUS treatment can be taken as effective anti-tumor vaccine56,60,81-88. A summary of the HIFU anti-cancer response is displayed in Figure 389.

3.

Summary of HIFU-induced anti-cancer response, in which STAT means signal transducer and activator of transcription, and TAA means tumor-associated antigens. Adapted from reference 89.

Studies showed that the adoptive transfer of immune cells activated with low-frequency HIFU also has very good effect90. After treating H22 cancer-bearing mice with low-frequency HIFU for 14 days, the T cells were taken out and then adoptively transferred into other mice bearing H22 cancer91. The experimental data indicates that CD3+, CD4+, the ratio of CD4+/CD8+, CTL cytotoxicity, and the secretion of IFN-γ and IFN-α of the mice after low-frequency HIFU treatment all increase significantly. After transferring the activated T lymphocytes to the cancer-bearing mice, both the tumor infiltration T lymphocytes and IFN-γ secretory cells increased significantly. Table 1 shows the overview of recent clinical research on immune effects after the irradiation of FUS92-99.

1.

Overview of described immune effects after irradiation of FUS in clinical studies

| Year | Authors | Patient information | Ultrasound parameters | Key observations |

| 1998 | Maders-bacher et al. | 5 patients with clinically localized prostate cancer | Frequency: 4.0 MHz

Focal length: 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0 cm Acoustic intensity: 1,260−2,200 W/cm2 Exposure time: 4s on followed by 12s off for re-positioning. |

Consistent HSP-27 expression was observed at the border zone of thermonecrosis in vivo, with highest levels occurring at 2-3 h following transrectal HIFU |

| 2004 | Wu et al. | 16 patients with solid malignancies (osteosarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma | Frequency: 0.8 MHz

Focal length: 135 mm Acoustic intensity: 5,000−20,000 W/cm2 Exposure time: variable Therapeutic time: 2.5−8 h (median: 5.2 h) |

Both the circulating CD4+ lymphocytes and the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ increased in patients after receiving HIFU |

| 2004 | Kramer et al. | 6 patients with prostate cancer | Frequency: 4 MHz

Focal length: not provided Acoustic intensity: 1,260−2,000 W/cm2 Exposure: 4 s per location |

A significant upregulation of HSP-72 and HSP-73 at the border lesion after HIFU treatment in prostate cancer patients |

| 2007 | Wu et al. | 23 patients with biopsy-proven breast cancer | Frequency: 1.6 MHz

Focal length: 90 mm, Acoustic intensity: 5,000−15,000 W/cm2 Exposure time: 45-150 mins (median: 1.3 h) |

All tumors treated with HIFU stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen and HSP70. No tumors treated with HIFU stained positive for CD44v6, MMP9, or PCNA |

| 2008 | Zhou et al. | 15 patients with solid malignancies | Frequency: 0.8 MHz

Focal length: not provided Acoustic intensity: 5,000−20,000 W/cm2 Exposure time: 0.78-3.62 h (mean: 2.74 h) |

Patients exposed to complete or partial HIFU ablation experienced a reduction in serum immunosuppressive cytokine expression levels, with nonmetastatic patients experiencing lower expression levels as compared with metastatic patients. VEGF, TGF-β1, and TGF-β2 were significantly reduced following HIFU treatment |

| 2009 | Lu et al. | 48 female patients with biopsy-proven breast cancer | Frequency: 1.6 MHz

Focal length: not provided Acoustic intensity: 5,000−15,000 W/cm2 Exposure time: 45-150 mins (mean: 1.3 h) |

Neoplasms treated with HIFU expressed elevated NK cells as well as CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, and B lymphocytes in the ablated periphery TILs positive for granzyme, FasL, and perforin were also greater in response to HIFU as compared with untreated control tumors |

| 2009 | Xu et al. | 23 female patients with biopsy-proven breast cancer | Frequency: 1.6 MHz

Focal length: not provided Acoustic intensity: 5,000−15,000 W/cm2 Exposure time: 45-150 min total time |

A significant increase in infiltration and activation of macrophages and DCs in HIFU-treated tumors, compared to controls |

| 2013 | Wang et al. | 120 patients with uterine fibroids (subserosal, intramural myomas, infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss) | Frequency: 0.8 MHz

Focal length: not provided Acoustic intensity: 400 W/cm2 Exposure time: 24 h or 72 h |

120 patients were divided into two groups, HIFU group and myomectomy group. Serum levels of IL-6 and IL-10 increased after treatment in both groups. Peak IL-6 and IL-10 levels were significantly lower in the HIFU group than in the myomectomy group. In contrast, IL-2 level decreased significantly in the myomectomy group compared to the HIFU group at 24 h post-operation |

Combined treatment strategies

Immunotherapy assisted by microbubbles and low-frequency HIFU

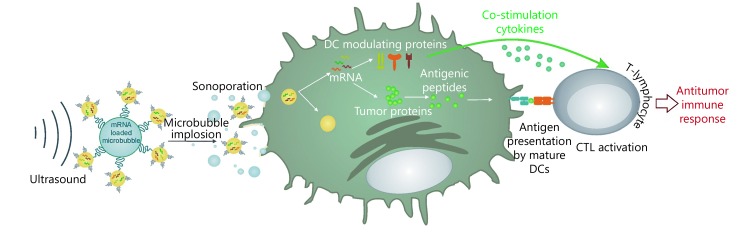

Cavitation effect is the important physical foundation of US-enhanced drug delivery and US-guided gene transfection100. One can deliver drugs or transfect genes by using the cavitation effect of US, and assist the tumor cellular immunotherapy101. Microbubbles are commonly used as gene or drug barriers. The US microbubble contrast agent can enhance the cavitation effect, improve drug delivery efficiency, and increase local drug concentration when the drug is loaded on the microbubbles102. The simplest method using microbubbles to deliver the active substance is co-injection103. Microbubbles and the active substance are mixed in some solution in vitro, and US irradiation promotes the delivery in vivo. However, the potential problem of co-injection is that the distribution of microbubbles and active substance in vivo is not exactly the same, which leads to the decrease of drug availability104. A better method is to conjugate the microbubbles with the active substance, and this method can ensure the same bio-distribution of two conjugating objects, improve the local concentration of the active substance, and decrease drug dosage105. The combination of targeted microbubbles and US afford a more complex and efficient delivery system. Such a therapeutic system possesses site specificity and cell specificity, which activates the immune system more efficiently104,106. Figure 4 shows the use of US with mRNA-loaded microbubbles, in which the mRNA-loaded microbubbles implode upon exposure to US and sonoporate the DCs107. As a result, both antigen and DC-modulating proteins are produced by DCs, which can lead to antigen presentation and T-cell activation. Many of the studies on microbubbles for drug and gene delivery have used commercially available US imaging contrast agents or similar bubbles equipped with targeting ligands on the surface or bubbles complexed with active substances108,109.

4.

Schematic of the use of US with mRNA-loaded microbubbles. Adapted from reference 107.

Even without any active agent, microbubbles still possess potential as immune response triggers110. In recent research, the effect of SonoVue microbubbles was examined in combination with focused US on solid CT-26 tumors in mice111. Intravenous injection of microbubbles came first, and then irradiation of US on the tumor followed immediately. Compared with results treated with only US, the combined therapeutic strategy distinctly decreased the tumor growth. Infiltration of immune cells increased in the tumor tissue, in which the CD8+CTL and CD4+non-Treg levels are included. As for the immune cells, microbubbles have also been commonly used to promote the permeability of the BBB under the irradiation of US112. And the natural killer cells moving through the BBB come at a much higher extent than if only US was used113,114.

Microbubbles, usually taken as carriers of delivering genes and antigens in immunotherapy, also have some disadvantages115,116. Firstly, the diameter of microbubbles is generally in the range 2−5 μm, the tumor tissue can be penetrated effectively without the irradiation of US. Secondly, the half-life period of microbubbles is relatively short in vivo, which is not beneficial to gene or drug delivery. One other potential problem is their complex preparation method, and much pretreatment is needed before use. The disadvantages above have limited the application of microbubbles in immunotherapy to a certain extent117.

Nanoparticles for low-frequency HIFU cancer immunotherapy

Nanoparticles have high surface area to volume ratio and advantageous delivery kinetics, and can be well used in clinical diagnosis and treatment including tumor immunotherapy according to their unique physical and chemical properties118. The size of nanoparticles are ranging from 1nm to 100nm119. The design of nanoparticles can be customized for a special application through modulating the properties of nanoparticles such as size, shape and charge120. According to the permeability and retention effect of nanoparticles, early researchers payed much attention to nanoparticle delivery on tumors, which could be further reinforced by conjugating tumor-targeting antibodies to the nanoparticles120-122. Nowadays these delivery methods are still commonly adopted in clinical application, and many research groups also put the natural bio-distribution of nanoparticle into use for cancer immunotherapy123.

The release of the drug can be triggered from different nanocarriers via the cavitation effects or radiation forces induced by US waves124. Nanoparticles have played an important role in ultrasound-mediated drug and gene delivery125,126. Compared with microbubbles, the major advantage of nanoparticles is that they can be made small enough to extravasate effectively from the leaky vasculature of some tumors, and the main disadvantages are their complex preparation, instability and toxicity127. Figure 5 shows the schematic of targeted gold nanoparticle (GNP) drug releasing and the enhancement of delivery through the BBB in US irradiation128.

5.

Schematic of the targeted GNP-drug release and the enhanced delivery through the BBB in US irradiation. Adapted from reference 128.

Many experimental results show that targeted US microbubbles can greatly improve the accuracy of tumor diagnosis, having the advantages of safety, efficiency, good targeting, and strong controllability in the treatment of tumors129. Although the application prospect of targeted microbubbles is exciting, there are still several points worth paying attention to: (1) Strengthening the binding ability between microbubbles and ligands, and reinforcing the binding strength between ligands and receptors are the basis for microbubbles to be targeted130. Although the antibiotin-biotin complex is currently the most effective targeted binding system, antibiotin is subject to endogenous biotin competition131. The main source is egg white or bacteria and other extrinsic proteins with immunogenicity, which may lead to a rejection reaction in clinical application. In addition, antibiotin is a kind of large molecular cation that is prone to form immune complexes in the renal basement membrane with high anion concentration in the body132. Therefore, a more ideal ligand connection method is needed133. (2) The construction of targeted microbubbles is tedious and time-consuming, and their stability and target seeking efficiency in vivo needs to be improved134. (3) The key technology of targeted microbubbles carrying drugs and genes needs to be improved135,136. It is necessary to better protect bioactive substances from shear flow or enzyme degradation during microbubble rupture before entering cells137. (4) In order to improve the targeting ability of microbubbles, researches on tumor immunity should be further improved138. (5) There are some dangers in the application of ultrasonic microbubbles139. The drug particles carried by microbubbles are easily ingested by the liver and spleen140. In this case, adverse reactions of different drugs may be relatively large141,142. In addition to microbubbles that may cause microembolism and toxicity in blood circulation, the potential risks caused by cavitation nuclei and cavitation effects should not be ignored143.

The advent of targeted US microbubbles is a revolution in the development of US medicine144. With the continuous improvement and optimization of construction technology, and the rapid development of related imaging technology, targeted US microbubbles will be increasingly accelerated into clinical applications, and drugs and gene therapy for tumors will certainly make gratifying progress145,146.

Low-frequency HIFU enhanced effect of checkpoint inhibitor therapy

Checkpoint blockade antibodies, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, have demonstrated high efficacy for some extracranial tumors147-150. Preclinical and anecdotal clinical evidence showed benefits from treatment of brain malignancies by using checkpoint blockade antibodies151. FUS has been used for delivery of antibodies to the brain to treat some diseases, thus, it can be arguably concluded that FUS also has the potential to promote the concentrations of immune-modulating antibodies at the desired site148,152-154. Besides the delivery of antibodies, the BBB can be opened with FUS to deliver larger vehicles for drugs and genes, such as liposomes, polymers, polymeric nanoparticles, and virus. The capability of targeted delivery of gene vectors opens up possibilities for altering immune stimuli within the diseased tissue155.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CI) immunotherapy is playing an important role in the treatment of cancer, but for a subgroup of patients, this treatment is ineffective or even a failure because of drug resistance156-158. To improve the CI therapy effect, many concerted efforts are conducted through the use of multiple CIs or use of CIs in combination with other anti-cancer agents. In 2017, the important first report on the efficacy of combining US with CI immunotherapy was published by Silvestrini et al159. Their work examined the impact of ablation coupled with aPD-1 and toll-like receptor agonist therapy (CpG). For the case of a single treated tumor, the growth rate of distal tumor is faster using combination therapy than that of aPD-1+CpG only, unless the drugs were administered before ablation. In this paper, an finding was that when two tumors were treated rather than one, abscopal effects were achieved such that the additional non-ablated tumor underwent regression, and survival was improved relative to drug-only treatment. In addition to suggesting the potential of local thermal ablation to affect the treatment of metastatic disease, this highlights the complexity of local treatment on immune effects in that they can be deleterious as well as complementary.

In 2019, Bulner et al.160 reported the use of “anti-vascular” ultrasound-stimulated microbubble (USMB) treatment in combination with anti-PD-1 CI therapy. Longitudinal growth studies along with acute experiments were conducted by using colorectal cancer cell line CT26 to assess ultrasound-induced anti-tumor immune responses. The results indicated that USMB+anti-PD-1 treatments significantly reinforced tumor growth inhibition and animal survival compared with monotherapies. The ability of anti-vascular USMBs increased the anti-tumor effects of CI therapy, but did not clearly support a T cell-dependent mechanism for the reinforcement.

Conclusion and perspectives

Tumor is a systemic disease. The ideal method of cancer treatment is to remove local tumors without damaging normal tissues, and to activate the whole body's anti-tumor immune response161. In recent years, many exciting research results have been achieved in the field of tumor immunotherapy, which bring great hope for the advanced or terminal cancer patient162. Due to the high degree of heterogeneity and specificity of the human immune system, current immunotherapy is not perfect yet, and cannot be commonly applied in clinical treatment163,164.

US has a good prospect in the treatment of diseases, especially in tumor ablation and drug delivery165. The use of US alone or the delivery of immune stimulants by US can induce an anti-tumor immune response166. The mechanical and cavitation effects produced by FUS can enhance the host's anti-tumor immune response, and deliver genes and antigens to cells to activate the anti-tumor immune response101. Compared with HIFU at high temperature aiming for ablating cancer tumor, low-frequency HIFU at low temperature can protect antigen more effectively, stimulate invasion and maturation of DCs in situ, and trigger stronger immune response167. Non-thermal effect of low-frequency HIFU can inhibit the growth and reproduction of cancer cells, damage DNA, and promote apoptosis. After the treatment with low-frequency HIFU, DCs could be recruited to aggregate into the damaged tumor areas, and mainly concentrated in the surrounding of the denatured areas168. The combination of low-frequency HIFU and immunotherapy has better results than immunotherapy alone169.

Many mechanisms of ultrasound-mediated immunotherapy have not been fully understood and need to be further studied78,170. First, many factors should be taken into consideration in tumor immunotherapy, such as the patient’s cancer type, genetic background, gender, age and so on. According to the action sites, indications and mechanism of different therapeutic drugs, appropriate drug combinations can be reasonably designed in the treatment of diseases. Secondly, low-frequency HIFU at a lower temperature can induce a stronger immune response171,172. However, the high-temperature HIFU is more effective for tumor ablation and curing primary diseases, so the advantages and disadvantages of tumor ablation and immunotherapy should be carefully weighed when using HIFU. In addition, as a carrier of genes or antigens in immunotherapy, microbubbles are also complicated to prepare with full consideration of the half-life and penetration efficiency of carriers162. It is undeniable that with the gradual thorough research on the mechanisms of immunotherapy, HIFU ablation, microbubble-mediated drug delivery and other mechanisms, the combined treatment of US and immunotherapy has a very broad prospect.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Development Fund of Hubei University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2019-21GP11) and the National College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Project (Grant No. 201810927021S). We thank Mrs. Jennifer Poston for editing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

References

- 1.Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 2011;480:480. doi: 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twal WO, Klatt SC, Harikrishnan K, Gerges E, Cooley MA, Trusk TC, et al Cellularized microcarriers as adhesive building blocks for fabrication of tubular tissue constructs. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:1470–81. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0883-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou BR, Rachev A, Shazly T The biaxial active mechanical properties of the porcine primary renal artery. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2015;48:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prim DA, Zhou BR, Hartstone-Rose A, Uline MJ, Shazly T, Eberth JF A mechanical argument for the differential performance of coronary artery grafts. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;54:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banchereau J, Steinman RM Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen DS, Mellman I Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321–30. doi: 10.1038/nature21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palucka K, Banchereau J Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells . Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:265–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran E, Turcotte S, Gros A, Robbins PF, Lu YC, Dudley ME, et al Cancer immunotherapy based on mutation-specific CD4+ T cells in a patient with epithelial cancer. Science. 2014;344:641–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1251102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curiel TJ Tregs and rethinking cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1167–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI31202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandler AD, Chihara H, Kobayashi G, Zhu XY, Miller MA, Scott DL, et al CpG oligonucleotides enhance the tumor antigen-specific immune response of a granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor-based vaccine strategy in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:394–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fifis T, Gamvrellis A, Crimeen-Irwin B, Pietersz GA, Li J, Mottram PL, et al Size-dependent immunogenicity: therapeutic and protective properties of nano-vaccines against tumors. J Immunol. 2004;173:3148–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu ZT, Ott PA, Wu CJ Towards personalized, tumour-specific, therapeutic vaccines for cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:168–82. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt K, Keller C, Kühl AA, Textor A, Seifert U, Blankenstein T, et al ERAP1-dependent antigen cross-presentation determines efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy in mice. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3243–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivaramakrishnan R, Incharoensakdi A Microalgae as feedstock for biodiesel production under ultrasound treatment–A review. Bioresour Technol. 2018;250:877–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahnken AH, Pereira PL, de Baère T Interventional oncologic approaches to liver metastases. Radiology. 2013;266:407–30. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quaia E, D'Onofrio M, Palumbo A, Rossi S, Bruni S, Cova M Comparison of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography versus baseline ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography in metastatic disease of the liver: diagnostic performance and confidence. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1599–609. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khokhlova VA, Bailey MR, Reed JA, Cunitz BW, Kaczkowski PJ, Crum LA Effects of nonlinear propagation, cavitation, and boiling in lesion formation by high intensity focused ultrasound in a gel phantom. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119:1834–48. doi: 10.1121/1.2161440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuzaki R, Shiina S, Tateishi R, Yoshida H, Goto E, Sugioka Y, et al Utility of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with Sonazoid in radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:759–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagterveld RM, Boels L, Mayer MJ, Witkamp GJ Visualization of acoustic cavitation effects on suspended calcite crystals. Ultrason Sonochem. 2011;18:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker KG, Robertson VJ, Duck FA A review of therapeutic ultrasound: biophysical effects. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1351–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unga J, Hashida M Ultrasound induced cancer immunotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;72:144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, et al Pericytes regulate the blood–brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468:557–61. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang TZ, Martin P, Fogarty B, Brown A, Schurman K, Phipps R, et al Exosome delivered anticancer drugs across the blood-brain barrier for brain cancer therapy in Danio rerio. Pharm Res. 2015;32:2003–14. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1593-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt SJ, Gade T, Soulen MC, Pickup S, Sehgal CM Antivascular ultrasound therapy: magnetic resonance imaging validation and activation of the immune response in murine melanoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:275–87. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowlkes JB Bioeffects of microsecond pulses of ultrasound—Launching a new era in diagnostic ultrasound safety. J Acoust Soc Am. 2017;141:3792. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang XM, Osborn T, Zhou BR, Meixner D, Kinnick RR, Bartholmai B, et al Lung ultrasound surface wave elastography: a pilot clinical study. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2017;64:1298–304. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2017.2707981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang XM, Zhou BR, Kalra S, Bartholmai B, Greenleaf J, Osborn T An ultrasound surface wave technique for assessing skin and lung diseases. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018;44:321–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubinsky TJ, Cuevas C, Dighe MK, Kolokythas O, Hwang JH High-intensity focused ultrasound: current potential and oncologic applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:191–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil PL, Terasaki M Coping with the inevitable: how cells repair a torn surface membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E124–9. doi: 10.1038/35074652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clay R, Bartholmai BJ, Zhou BR, Karwoski R, Peikert T, Osborn T, et al Assessment of interstitial lung disease using lung ultrasound surface wave elastography: a novel technique with clinicoradiologic correlates. J Thorac Imaging. 2019;34:313–9. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lejbkowicz F, Salzberg S Distinct sensitivity of normal and malignant cells to ultrasound in vitro . Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:1575–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s61575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sit AJ, Kazemi A, Zhou BR, Zhang XM Comparison of ocular biomechanical properties in normal and glaucomatous eyes using ultrasound surface wave elastography. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 2018;59:1218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feril Jr LB, Kondo T Biological effects of low intensity ultrasound: the mechanism involved, and its implications on therapy and on biosafety of ultrasound. J Radiat Res. 2004;45:479–89. doi: 10.1269/jrr.45.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou BR, Bartholmai BJ, Kalra S, Osborn TG, Zhang XM Lung US surface wave elastography in interstitial lung disease staging. Radiology. 2019;291:479–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Mahrouki AA, Karshafian R, Giles A, Czarnota GJ Bioeffects of ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles on endothelial cells: gene expression changes associated with radiation enhancement in vitro . Ultrasound Med Biol. 2012;38:1958–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapelon JY. High-intensity ultrasound therapy method and apparatus with controlled cavitation effect and reduced side lobes. United States Patent 5573497.

- 38.Datta S, Coussios CC, McAdory LE, Tan J, Porter T, de Courten-Myers G, et al Correlation of cavitation with ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yumita N, Nishigaki R, Umemura K, Umemura SI Hematoporphyrin as a sensitizer of cell-damaging effect of ultrasound. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1989;80:219–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb02295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal I, Sostaric JZ, Riesz P Sonodynamic therapy––a review of the synergistic effects of drugs and ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem. 2004;11:349–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cain CA, Fowlkes JB. Method and assembly for performing ultrasound surgery using cavitation: USA, 6413216. 2002-07-02.

- 42.Wu JR, Nyborg WL Ultrasound, cavitation bubbles and their interaction with cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1103–16. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dasgupta A, Liu MJ, Ojha T, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T Ultrasound-mediated drug delivery to the brain: principles, progress and prospects. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2016;20:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong YP, Wang ZG, Dong GF, Sun Y, Wang X, Rong Y, et al Low-intensity focused ultrasound mediated localized drug delivery for liver tumors in rabbits. Drug Deliv. 2016;23:2280–9. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.972528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen JL, Zhuo NQ, Xu SX, Song ZJ, Hu ZM, Hao J, et al Resveratrol delivery by ultrasound-mediated nanobubbles targeting nucleus pulposus cells. Nanomedicine. 2018;13:1433–46. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubanek J Neuromodulation with transcranial focused ultrasound. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44:E14. doi: 10.3171/2017.11.FOCUS17621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Cock I, Zagato E, Braeckmans K, Luan Y, de Jong N, de Smedt SC, et al Ultrasound and microbubble mediated drug delivery: acoustic pressure as determinant for uptake via membrane pores or endocytosis . J Control Release. 2015;197:20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maresca D, Lakshmanan A, Abedi M, Bar-Zion A, Farhadi A, Lu GJ, et al Biomolecular ultrasound and sonogenetics. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2018;9:229–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060817-084034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kokhuis TJA, Skachkov I, Naaijkens BA, Juffermans LJM, Kamp O, Kooiman K, et al Intravital microscopy of localized stem cell delivery using microbubbles and acoustic radiation force. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:220–7. doi: 10.1002/bit.25337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allen JS Acoustic fields and forces in drug delivery applications. J Acoust Soc Am. 2018;144:1750. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Browning RJ, Stride E Microbubble-mediated delivery for cancer therapy. Fluids. 2018;3:74. doi: 10.3390/fluids3040074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey MR, Khokhlova VA, Sapozhnikov OA, Kargl SG, Crum LA Physical mechanisms of the therapeutic effect of ultrasound (a review) Acoust Phys. 2003;49:369–88. doi: 10.1134/1.1591291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kubo K, Cheng YS, Zhou BR, An KN, Moran SL, Amadio PC, et al The quantitative evaluation of the relationship between the forces applied to the palm and carpal tunnel pressure. J Biomech. 2018;66:170–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ng GYF, Wong RYF Ultrasound phonophoresis of panax notoginseng improves the strength of repairing ligament: a rat model. Ultrasound Med BIol. 2008;34:1919–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fasel TR, Todd MD Chaotic insonification for health monitoring of an adhesively bonded composite stiffened panel. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2010;24:1420–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ymssp.2009.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang SJ, Lewallen DG, Bolander ME, Chao EYS, Ilstrup DM, Greenleaf JF Low intensity ultrasound treatment increases strength in a rat femoral fracture model. J Orthop Res. 1994;12:40–7. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stieglitz J, Madimenos F, Kaplan H, Gurven M Calcaneal quantitative ultrasound indicates reduced bone status among physically active adult forager-horticulturalists. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:663–71. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng YS, Zhou BR, Kubo K, An KN, Moran SL, Amadio PC, et al Comparison of two ways of altering carpal tunnel pressure with ultrasound surface wave elastography. J Biomech. 2018;74:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leinenga G, Langton C, Nisbet R, Götz J Ultrasound treatment of neurological diseases—current and emerging applications. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:161–71. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xin ZC, Lin GT, Lei HE, Lue TF, Guo YL Clinical applications of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and its potential role in urology. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5:255–66. doi: 10.21037/tau.2016.02.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farkona S, Diamandis EP, Blasutig IM Cancer immunotherapy: the beginning of the end of cancer? BMC Med. 2016;14:73. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tu JW, Zhang H, Yu JS, Liufu C, Chen ZY Ultrasound-mediated microbubble destruction: a new method in cancer immunotherapy. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:5763–75. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S171019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Groothuis DR The blood-brain and blood-tumor barriers: a review of strategies for increasing drug delivery. Neuro Oncol. 2000;2:45–59. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/2.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Tellingen O, Yetkin-Arik B, de Gooijer MC, Wesseling P, Wurdinger T, de Vries HE Overcoming the blood–brain tumor barrier for effective glioblastoma treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;19:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deeken JF, Löscher W The blood-brain barrier and cancer: transporters, treatment, and Trojan horses. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1663–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park J, Aryal M, Vykhodtseva N, Zhang YZ, McDannold N Evaluation of permeability, doxorubicin delivery, and drug retention in a rat brain tumor model after ultrasound-induced blood-tumor barrier disruption. J Control Release. 2017;250:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Osswald M, Blaes J, Liao YX, Solecki G, Gömmel M, Berghoff AS, et al Impact of blood–brain barrier integrity on tumor growth and therapy response in brain metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:6078–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arvanitis CD, Askoxylakis V, Guo YT, Datta M, Kloepper J, Ferraro GB, et al Mechanisms of enhanced drug delivery in brain metastases with focused ultrasound-induced blood–tumor barrier disruption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E8717–26. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807105115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lyle LT, Lockman PR, Adkins CE, Mohammad AS, Sechrest E, Hua E, et al Alterations in pericyte subpopulations are associated with elevated blood–tumor barrier permeability in experimental brain metastasis of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5287–99. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gril B, Paranjape AN, Woditschka S, Hua E, Dolan EL, Hanson J, et al Reactive astrocytic S1P3 signaling modulates the blood–tumor barrier in brain metastases. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2705. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05030-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang TT, Li W, Meng GM, Wang P, Liao WZ Strategies for transporting nanoparticles across the blood–brain barrier. Biomater Sci. 2016;4:219–29. doi: 10.1039/C5BM00383K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cummings J Lessons learned from Alzheimer disease: clinical trials with negative outcomes. Clin Transl Sci. 2018;11:147–52. doi: 10.1111/cts.12491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McDannold N, Zhang YZ, Vykhodtseva N The effects of oxygen on ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier disruption in mice. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:469–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen PY, Wei KC, Liu HL Neural immune modulation and immunotherapy assisted by focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2682–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1071749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ter Haar G Therapeutic applications of ultrasound. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;93:111–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu HL, Hsieh HY, Lu LA, Kang CW, Wu MF, Lin CY Low-pressure pulsed focused ultrasound with microbubbles promotes an anticancer immunological response. J Transl Med. 2012;10:221. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jiang YQ, Guo QM, Xu XP, Liang JC, He YY, An SH, et al Preparation of chaperone-antigen peptide vaccine derived from human gastric cancer stem cells and its immune function. Chin J Oncol. 2017;39:109–14. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bandyopadhyay S, Quinn TJ, Scandiuzzi L, Basu I, Partanen A, Tomé WA, et al Low-intensity focused ultrasound induces reversal of tumor-induced T cell tolerance and prevents immune escape. J Immunol. 2016;196:1964–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pan JB, Wang YQ, Zhang C, Wang XY, Wang HY, Wang JJ, et al Antigen-directed fabrication of a multifunctional nanovaccine with ultrahigh antigen loading efficiency for tumor photothermal-immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1704408. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang XM, Zhou BR, Miranda AF, Trost LW A novel noninvasive ultrasound vibro-elastography technique for assessing patients with erectile dysfunction and peyronie disease. Urology. 2018;116:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang R, Reilly CR, Rescorla FJ, Sanghvi NT, Fry FJ, Franklin Jr TD, et al Effects of high-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of experimental neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:246–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90321-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takahashi F, Akutagawa S, Fukumoto H, Tsukiyama S, Ohe Y, Takahashi K, et al Osteopontin induces angiogenesis of murine neuroblastoma cells in mice. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:707–12. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Repasky E Focused ultrasound: an effective technique for unleashing the power of immunotherapy in the tumor microenvironment? J Ther Ultrasound. 2015;3:O39. doi: 10.1186/2050-5736-3-S1-O39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rajendrakumar SK, Uthaman S, Cho CS, Park IK Nanoparticle-based phototriggered cancer immunotherapy and its domino effect in the tumor microenvironment. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:1869–87. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schilling S, Rahfeld JU, Lues I, Lemere CA Passive Aβ immunotherapy: current achievements and future perspectives. Molecules. 2018;23:1068. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang CP, Li Y, Du M, Chen ZY Recent advances in ultrasound-triggered therapy. J Drug Target. 2019;27:33–50. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1464012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sebio A, Wilky BA, Keedy VL, Jones RL The current landscape of early drug development for patients with sarcoma in the immunotherapy era. Future Oncol. 2018;14:1197–211. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang XM, Zhou BR, Osborn T, Bartholmai B, Kalra S Lung ultrasound surface wave elastography for assessing interstitial lung disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2019;66:1346–52. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2018.2872907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cirincione R, di Maggio FM, Forte GI, Minafra L, Bravatà V, Castiglia L, et al High-intensity focused ultrasound–and radiation therapy–induced immuno-modulation: comparison and potential opportunities. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:398–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rezayat E, Toostani IG A review on brain stimulation using low intensity focused ultrasound. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2016;7:187–94. doi: 10.15412/J.BCN.03070303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ran LF, Xie XP, Xia JZ, Xie FL, Fan YM, Wu F Specific antitumour immunity of HIFU-activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes after adoptive transfusion in tumour-bearing mice. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32:204–10. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2015.1112438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Madersbacher S, Gröbl M, Kramer G, Dirnhofer S, Steiner GE, Marberger M Regulation of heat shock protein 27 expression of prostatic cells in response to heat treatment. Prostate. 1998;37:174–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19981101)37:3<174::AID-PROS6>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu F, Wang ZB, Lu P, Xu ZL, Chen WZ, Zhu H, et al Activated anti-tumor immunity in cancer patients after high intensity focused ultrasound ablation. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:1217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kramer G, Steiner GE, Gröbl M, Hrachowitz K, Reithmayr F, Paucz L, et al Response to sublethal heat treatment of prostatic tumor cells and of prostatic tumor infiltrating T-cells. Prostate. 2004;58:109–20. doi: 10.1002/pros.10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wu F, Wang ZB, Cao YD, Zhou Q, Zhang Y, Xu ZL, et al Expression of tumor antigens and heat-shock protein 70 in breast cancer cells after high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1237–42. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhou Q, Zhu XQ, Zhang J, Xu ZL, Lu P, Wu F Changes in circulating immunosuppressive cytokine levels of cancer patients after high intensity focused ultrasound treatment. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lu P, Zhu XQ, Xu ZL, Zhou Q, Zhang J, Wu F Increased infiltration of activated tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after high intensity focused ultrasound ablation of human breast cancer. Surgery. 2009;145:286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xu ZL, Zhu XQ, Lu P, Zhou Q, Zhang J, Wu F Activation of tumor-infiltrating antigen presenting cells by high intensity focused ultrasound ablation of human breast cancer. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:50–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang XY, Qin J, Chen JY, Wang LF, Chen WZ, Tang LD The effect of high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment on immune function in patients with uterine fibroids. Int J Hyperthermia. 2013;29:225–33. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2013.775672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Matula T, Sapozhnikov OA, Ostrovsky L A, Brayman A A, Kucewicz J, MacConaghy B E, et al Ultrasound-based cell sorting with microbubbles: A feasibility study. J Acoust Soc Am. 2018;144:41. doi: 10.1121/1.5044405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen PY, Hsieh HY, Huang CY, Lin CY, Wei KC, Liu HL Focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening to enhance interleukin-12 delivery for brain tumor immunotherapy: a preclinical feasibility study. J Transl Med. 2015;13:93. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0451-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sawaguchi T, Demachi F, Murayama Y, Oitate R, Minakuchi S, Mochizuki T, et al. Active control of cell with microbubbles for cellular immunotherapy by acoustic force. In: Proceedings of the 2015 8th Biomedical Engineering International Conference. Pattaya, Thailand: IEEE; 2015.

- 103.Sontum P, Kvåle S, Healey AJ, Skurtveit R, Watanabe R, Matsumura M, et al Acoustic Cluster Therapy (ACT)–A novel concept for ultrasound mediated, targeted drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2015;495:1019–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Golombek SK, May JN, Theek B, Appold L, Drude N, Kiessling F, et al Tumor targeting via EPR: strategies to enhance patient responses . Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;130:17–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang H, Tu JW, Liao YY, Cai K, Li Y, Liufu C, et al Chitosan-conjugated lipid microbubble combined with ultrasound for efficient gene transfection. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2018;32:982–7. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2018.1482232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.de Cock I, Lajoinie G, Versluis M, de Smedt SC, Lentacker I Sonoprinting and the importance of microbubble loading for the ultrasound mediated cellular delivery of nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2016;83:294–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dewitte H, van Lint S, Heirman C, Thielemans K, de Smedt SC, Breckpot K, et al The potential of antigen and TriMix sonoporation using mRNA-loaded microbubbles for ultrasound-triggered cancer immunotherapy. J Control Release. 2014;194:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Min HS, Son S, You DG, Lee TW, Lee J, Lee S, et al Chemical gas-generating nanoparticles for tumor-targeted ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-triggered drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2016;108:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bez M, Kremen TJ, Tawackoli W, Avalos P, Sheyn D, Shapiro G, et al Ultrasound-mediated gene delivery enhances tendon allograft integration in mini-pig ligament reconstruction. Mol Ther. 2018;26:1746–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kodama T, Tomita Y, Koshiyama KI, Blomley MJK Transfection effect of microbubbles on cells in superposed ultrasound waves and behavior of cavitation bubble. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:905–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lin YT, Lin LZ, Cheng MW, Jin LF, Du LF, Han T, et al Effect of acoustic parameters on the cavitation behavior of SonoVue microbubbles induced by pulsed ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;35:176–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Burgess MT, Apostolakis I, Konofagou EE Power cavitation-guided blood-brain barrier opening with focused ultrasound and microbubbles. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:065009. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aab05c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maria NSS, Barnes SR, Weist MR, Colcher D, Raubitschek AA, Jacobs RE Low dose focused ultrasound induces enhanced tumor accumulation of natural killer cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang XM, Zhou BR, VanBuren WM, Burnett TL, Knudsen JM Transvaginal ultrasound vibro-elastography for measuring uterine viscoelasticity: a phantom study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45:617–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sierra C, Acosta C, Chen C, Wu SY, Karakatsani ME, Bernal M, et al Lipid microbubbles as a vehicle for targeted drug delivery using focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:1236–50. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16652630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ho YJ, Wang TC, Fan CH, Yeh CK Spatially uniform tumor treatment and drug penetration by regulating ultrasound with microbubbles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:17784–91. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b05508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Myhre O, Bjørgan M, Grant D, Hustvedt SO, Sontum PC, Dirven H Safety assessment in rats and dogs of Acoustic Cluster Therapy, a novel concept for ultrasound mediated, targeted drug delivery. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2016;4:e00274. doi: 10.1002/prp2.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yildirim A, Chattaraj R, Blum NT, Goodwin AP Understanding acoustic cavitation initiation by porous nanoparticles: toward nanoscale agents for ultrasound imaging and therapy. Chem Mater. 2016;28:5962–72. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b02634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gorick CM, Sheybani ND, Curley CT, Price RJ Listening in on the microbubble crowd: advanced acoustic monitoring for improved control of blood-brain barrier opening with focused ultrasound. Theranostics. 2018;8:2988–91. doi: 10.7150/thno.26025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen Q, Xu LG, Chen JW, Yang ZJ, Liang C, Yang Y, et al Tumor vasculature normalization by orally fed erlotinib to modulate the tumor microenvironment for enhanced cancer nanomedicine and immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2017;148:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lu KD, He CB, Guo NN, Chan C, Ni KY, Weichselbaum RR, et al Chlorin-based nanoscale metal–organic framework systemically rejects colorectal cancers via synergistic photodynamic therapy and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy . J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12502–10. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Day ES, Morton JG, West JL Nanoparticles for thermal cancer therapy. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:074001. doi: 10.1115/1.3156800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Paefgen V, Doleschel D, Kiessling F Evolution of contrast agents for ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-mediated drug delivery. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:197. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Singh MS, Bhaskar S Nanocarrier-based immunotherapy in cancer management and research. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2014;3:121–34. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S62471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu Q, Chen FQ, Hou L, Shen LM, Zhang XQ, Wang DG, et al Nanocarrier-mediated chemo-immunotherapy arrested cancer progression and induced tumor dormancy in desmoplastic melanoma. ACS Nano. 2018;12:7812–25. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Suzuki R, Namai E, Oda Y, Nishiie N, Otake S, Koshima R, et al Cancer gene therapy by IL-12 gene delivery using liposomal bubbles and tumoral ultrasound exposure. J Control Release. 2010;142:245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fontana F, Liu DF, Hirvonen J, Santos HA Delivery of therapeutics with nanoparticles: what's new in cancer immunotherapy? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2017;9:e1421. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Coluccia D, Figueiredo CA, Wu MY, Riemenschneider AN, Diaz R, Luck A, et al Enhancing glioblastoma treatment using cisplatin-gold-nanoparticle conjugates and targeted delivery with magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound. Nanomedicine. 2018;14:1137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2018.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Oerlemans C, Bult W, Bos M, Storm G, Nijsen JF, Hennink WE Polymeric micelles in anticancer therapy: targeting, imaging and triggered release. Pharm Res. 2010;27:2569–89. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0233-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lin CY, Liu TM, Chen CY, Huang YL, Huang WK, Sun CK, et al Quantitative and qualitative investigation into the impact of focused ultrasound with microbubbles on the triggered release of nanoparticles from vasculature in mouse tumors. J Control Release. 2010;146:291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zheng SG, Xu HX, Chen HR Nano/microparticles and ultrasound contrast agents. World J Radiol. 2013;5:468–71. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i12.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Riley RS, Day ES Gold nanoparticle-mediated photothermal therapy: applications and opportunities for multimodal cancer treatment. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2017;9:e1449. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Luo ZM, Jin K, Pang Q, Shen S, Yan ZQ, Jiang T, et al On-demand drug release from dual-targeting small nanoparticles triggered by high-intensity focused ultrasound enhanced glioblastoma-targeting therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:31612–25. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b10866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pediconi F, Napoli A, di Mare L, Vasselli F, Catalano C MRgFUS: from diagnosis to therapy. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:S118–20. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(12)70049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Thanou M, Gedroyc W MRI-guided focused ultrasound as a new method of drug delivery. J Drug Deliv. 2013;2013:616197. doi: 10.1155/2013/616197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hersh DS, Wadajkar AS, Roberts NB, Perez JG, Connolly NP, Frenkel V, et al Evolving drug delivery strategies to overcome the blood brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:1177–93. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151221150733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rapoport N. Drug-loaded perfluorocarbon nanodroplets for ultrasound-mediated drug delivery. In: Escoffre JM, Bouakaz A. Therapeutic Ultrasound. Cham: Springer; 2016; 221-41.

- 138.Wright M, Centelles M, Gedroyc W, Thanou M. Image guided focused ultrasound as a new method of targeted drug delivery. In: Thanou M. Theranostics and Image Guided Drug Delivery. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2018; 1-28.

- 139.Stavarache MA, Petersen N, Jurgens EM, Milstein ER, Rosenfeld ZB, Ballon DJ, et al Safe and stable noninvasive focal gene delivery to the mammalian brain following focused ultrasound. J Neurosurg. 2018;130:989–98. doi: 10.3171/2017.8.JNS17790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Coluccia D, Fandino J, Schwyzer L, O'Gorman R, Remonda L, Anon J, et al First noninvasive thermal ablation of a brain tumor with MR-guided focusedultrasound. J Ther Ultrasound. 2014;2:17. doi: 10.1186/2050-5736-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.O’Reilly MA, Hynynen K Ultrasound enhanced drug delivery to the brain and central nervous system. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:386–96. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2012.666709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Airan RD, Meyer RA, Ellens NPK, Rhodes KR, Farahani K, Pomper MG, et al Noninvasive targeted transcranial neuromodulation via focused ultrasound gated drug release from nanoemulsions . Nano Lett. 2017;17:652–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Song J, Pulkkinen A, Huang YX, Hynynen K Investigation of standing-wave formation in a human skull for a clinical prototype of a large-aperture, transcranial MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) phased array: an experimental and simulation study. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;59:435–44. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2174057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Jones RM, Deng LL, Leung K, McMahon D, O'Reilly MA, Hynynen K Three-dimensional transcranial microbubble imaging for guiding volumetric ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening. Theranostics. 2018;8:2909–26. doi: 10.7150/thno.24911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Khanna N, Gandhi D, Steven A, Frenkel V, Melhem ER Intracranial applications of MR imaging–guided focused ultrasound. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:426–31. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhang YR, Tan HY, Bertram EH, Aubry JF, Lopes MB, Roy J, et al Non-invasive, focal disconnection of brain circuitry using magnetic resonance-guided low-intensity focused ultrasound to deliver a neurotoxin. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:2261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Chen Q, Xu LG, Liang C, Wang C, Peng R, Liu Z Photothermal therapy with immune-adjuvant nanoparticles together with checkpoint blockade for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13193. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, et al Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Philips GK, Atkins M Therapeutic uses of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies. Int Immunol. 2015;27:39–46. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxu095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Shazly T, Rachev A, Lessner S, Argraves WS, Ferdous J, Zhou BR, et al On the uniaxial ring test of tissue engineered constructs. Exp Mech. 2015;55:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s11340-014-9910-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Qian JM, Yu JB, Kluger HM, Chiang VLS Timing and type of immune checkpoint therapy affect the early radiographic response of melanoma brain metastases to stereotactic radiosurgery. Cancer. 2016;122:3051–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Jindal V, Gupta S Expected paradigm shift in brain metastases therapy—Immune checkpoint inhibitors. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:7072–8. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0905-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tetzlaff MT, Nelson KC, Diab A, Staerkel GA, Nagarajan P, Torres-Cabala CA, et al Granulomatous/sarcoid-like lesions associated with checkpoint inhibitors: a marker of therapy response in a subset of melanoma patients. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:14. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0323-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zhou BR, Chen JJ, Kazemi A, Sit AJ, Zhang XM An ultrasound vibro-elastography technique for assessing papilledema. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45:2034–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Robin TP, Breeze RE, Smith DE, Rusthoven CG, Lewis KD, Gonzalez R, et al Immune checkpoint inhibitors and radiosurgery for newly diagnosed melanoma brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2018;140:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2930-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Schneider H, Downey J, Smith A, Zinselmeyer BH, Rush C, Brewer JM, et al Reversal of the TCR stop signal by CTLA-4. Science. 2006;313:1972–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1131078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kleinovink JW, Marijt KA, Schoonderwoerd MJA, van Hall T, Ossendorp F, Fransen MF PD-L1 expression on malignant cells is no prerequisite for checkpoint therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1294299. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1294299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Zhou BR, Zhang XM The effect of pleural fluid layers on lung surface wave speed measurement: Experimental and numerical studies on a sponge lung phantom. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;89:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Silvestrini MT, Ingham ES, Mahakian LM, Kheirolomoom A, Liu Y, Fite BZ, et al Priming is key to effective incorporation of image-guided thermal ablation into immunotherapy protocols. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e90521. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Bulner S, Prodeus A, Gariepy J, Hynynen K, Goertz DE Enhancing checkpoint inhibitor therapy with ultrasound stimulated microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45:500–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Escoffre JM, Deckers R, Bos C, Moonen C. Bubble-assisted ultrasound: application in immunotherapy and vaccination. In: Escoffre JM, Bouakaz A. Therapeutic Ultrasound. Cham: Springer; 2016; 243-61.

- 162.Giuntini F, Foglietta F, Marucco AM, Troia A, Dezhkunov NV, Pozzoli A, et al Insight into ultrasound-mediated reactive oxygen species generation by various metal-porphyrin complexes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;121:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Warnez M, Vlaisavljevich E, Xu Z, Johnsen E Damage mechanisms for ultrasound-induced cavitation in tissue. AIP Conf Proc. 2017;1821:080004. [Google Scholar]

- 164.Zhou BR, Zhang XM Lung mass density analysis using deep neural network and lung ultrasound surface wave elastography. Ultrasonics. 2018;89:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Miller DL Mechanisms for induction of pulmonary capillary hemorrhage by diagnostic ultrasound: review and consideration of acoustical radiation surface pressure. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:2743–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Slikkerveer J, Juffermans LJM, van Royen N, Appelman Y, Porter TR, Kamp O Therapeutic application of contrast ultrasound in ST elevation myocardial infarction: role in coronary thrombosis and microvascular obstruction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:45–53. doi: 10.1177/2048872617728559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Ciocca DR, Arrigo AP, Calderwood SK Heat shock proteins and heat shock factor 1 in carcinogenesis and tumor development: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87:19–48. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0918-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Arthanareeswaran VKA, Berndt-Paetz M, Ganzer R, Stolzenburg JU, Ravichandran-Chandra A, Glasow A, et al Harnessing macrophages in thermal and non-thermal ablative therapies for urologic cancers–Potential for immunotherapy. Laparosc Endosc Robot Surg. 2018;1:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lers.2018.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Cruz JM, Hauck M, Cardoso Pereira AP, Moraes MB, Martins CN, da Silva Paulitsch F, et al Effects of different therapeutic ultrasound waveforms on endothelial function in healthy volunteers: a randomized clinical trial. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:471–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Davda R, Prentice M, Sarova A, Nei W, Orczyk C, Arya M, et al Late toxicity and patient reported outcomes in patients treated with salvage radiation following primary high intensity focal ultrasound for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99:E226. [Google Scholar]

- 171.Gulick DW, Li T, Kleim JA, Towe BC Comparison of electrical and ultrasound neurostimulation in rat motor cortex. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:2824–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.08.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Fan CH, Lin YT, Ho YJ, Yeh CK Spatial-temporal cellular bioeffects from acoustic droplet vaporization. Theranostics. 2018;8:5731–43. doi: 10.7150/thno.28782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]