Abstract

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), also known as extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a granulomatous, non-IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction of the alveoli and distal bronchioles presenting as an acute, subacute or chronic condition. It is most commonly associated with exposure to extrinsic allergens (eg, avian dust, mould and tobacco) and medications including antiarrhythmics (eg, amiodarone), cytotoxics (eg, methotrexate) and antiepileptics (eg, carbamazepine). Individuals diagnosed with this condition can present with severe hypoxia and respiratory failure. The fundamental principle of management is to remove the causative allergen. Evidence implicating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a causative agent is limited, and this case report describes a rare clinical presentation of HP associated with sertraline, how it was diagnosed and subsequently treated. It is anticipated that raising awareness of this interaction will assist multidisciplinary teams, managing patients diagnosed with HP, to be more cognisant of sertraline as being an aetiological factor for this condition.

Keywords: interstitial lung disease, respiratory medicine, psychiatry (drugs and medicines), adult intensive care, Unwanted effects / adverse reactions

Background

This case report describes the clinical presentation of a severe hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) associated with a frequently prescribed selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (sertraline), its diagnosis and subsequent management. It is anticipated that raising awareness of this interaction will assist multidisciplinary teams managing patients diagnosed with HP, to be more cognisant of sertraline as being an aetiological factor for this disease.

Case presentation

On 31 July 2018, a 47-year-old Caucasian female (78 kg) presented to the Accident and Emergency (A&E) department with shortness of breath, right-sided pleuritic chest pain and a productive cough. Her medical history revealed she suffered from severe depression and gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder, was a non-smoker and had no known drug allergies. She had been diagnosed with HP in March 2016, no aetiological cause had been found and she had responded to oral steroids. Her current medications included lansoprazole 30 mg once daily (OD) and sertraline 200 mg OD, which was initiated by her general practitioner in June 2015 at 100 mg OD and had been increased to 200 mg OD 2 weeks prior to admission after worsening of her depression.

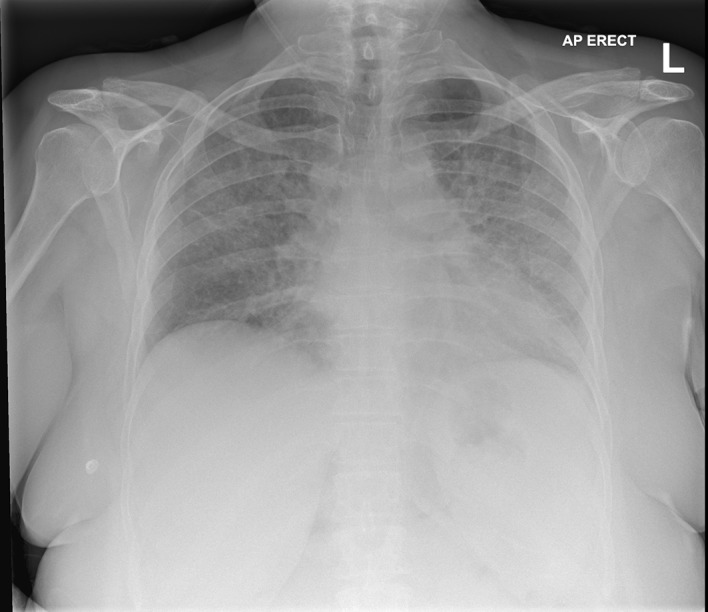

Clinical examination in A&E revealed signs of systemic infection (tachycardia, hypotension and fever, hypoxia (SpO2=96% on 28%)) a red blanching rash on her abdomen, and a high national early warning score of 10. Clinical examination revealed bilateral reduction in air entry with crepitations on auscultation, investigations demonstrated raised inflammatory markers on the haematological screen (table 1) and diffuse interstitial infiltrates on a chest radiograph (CXR, figure 1). Due to her clinical presentation, a preliminary diagnosis of community acquired pneumonia was made and benzylpenicillin (1.2 g) and clarithromycin (500 mg) were administered and the patient subsequently admitted to the respiratory ward.

Table 1.

Blood results 2016 and 2018 on admission, mid-admission and on discharge

| Range | 2016 | 2018 | |||

| On admission (baseline) | Mid-admission | On discharge | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 115–160 | 131 | 134 | 89 | 114 |

| Mean cell volume (fL) | 79–99 | 98.7 | 99.8 | 101 | 99.7 |

| White cell count (109/L) | 4–11 | 3.6 | 20.1 | 11.8 | 6.7 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 150–450 | 218 | 226 | 163 | 296 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 1.7–7.5 | 3.8 | 2.81 | 9.34 | 4.05 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 133–146 | 135 | 134 | 137 | 137 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.5–5.3 | 4.1 | 4 | 3.9 | 4.4 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 2.5–7.8 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 3.5 |

| Alanine transaminase (AT U/L) | <41 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 39 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35–50 | 42 | 38 | 30 | 44 |

| Alk phosphatase (AP U/L) | 20–130 | 93 | 91 | 84 | 75 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | <21 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 6 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | <1 | 11 | 85 | 79 | 7 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | – | 9 | 7.2 | 8.9 | 4.9 |

| Corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 2.2–2.6 | 2.21 | 2.27 | 2.1 | 2.43 |

| Magnesium (mmol/L) | 0.7–0.8 | 0.8 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.8 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 0.8–1.5 | 0.9 | 1.13 | 0.54 | 1.75 |

| INR | 0.85–1.25 | 1.1 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.05 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | >90 | 90 | 77 | >90 | 74 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 44–133 | 70 | 71 | 44 | 73 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; INR, International Normalised Ratio.

Figure 1.

On admission to Accident and Emergency (31 July 2018). AP, alk phosphatase.

Over the next 3 days, her respiratory condition continued to decline, on 2 August 2018, an arterial blood gas demonstrated a pO2 7 kPa breathing 60% O2 (table 2), a CT pulmonary angiogram was completed and though a pulmonary embolus was excluded, it clearly demonstrated ground glass changes in her lung parenchyma consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome. It was assumed this was due to a recurrence of her HP, and she was admitted to the critical care unit (CCU). Serological tests for HP and other interstitial lung diseases (ILD) were all completed at this stage (total IgE, IgA, G&M, avian precipitins (budgerigar and pigeon), Aspergillus precipitins, aspergillus IgE, anti-GBM, ANCA, antinuclear antibodies) and nothing abnormal was detected from these investigations.

Table 2.

Arterial blood gases throughout admission

| Parameters/week | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9* | 10 |

| SaO2 (%) | >88 | 96 | 94 | 80 | 88 | 94 | 95 | 88 | 91 | 96 | 98 |

|

PaO2

(kpa) |

12–15 | 7.71 | 7.11 | 13.6 | 8 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 10.45 | 9.95 |

| pH | 7.36–7.44 | 7.46 | 7.32 | 7.38 | 7.36 | 7.3 | 7.36 | 7.23 | 7.18 | 6 | 7.36 |

|

PCO2

(kpa) |

4.5–6.1 | 4.48 | 7.45 | 8.1 | 10 | 10 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 10 | 5.09 |

| HCO3−(mmol/L) | 21–28 | 24.9 | 22.6 | 25.4 | 40 | 30.9 | 35.5 | 37 | 35.2 | 33.7 | 27 |

|

PEEP

(cmH2O) |

>10 | – | 26 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 25 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| FiO2 (%) | 21% | – | 0.85 | 0.4 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.3 | 0.28 |

*Sertraline stopped.

PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

She initially required continuous positive airway pressure, but despite high dose methylprednisolone, she required intubating and ventilating on 13 August 2018. She required prolonged ventilation and a surgical tracheostomy was placed on 12 September. Her conscious level throughout this period was three out of fifteen on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS); however, as she began to regain consciousness, she progressively developed hypoactive delirium (as per Confusion Assessment Method score) and was consequently prescribed quetiapine 25 mg twice daily.

Investigations

On the CCU, several investigations were undertaken to determine the cause of her condition.

Chest radiograph

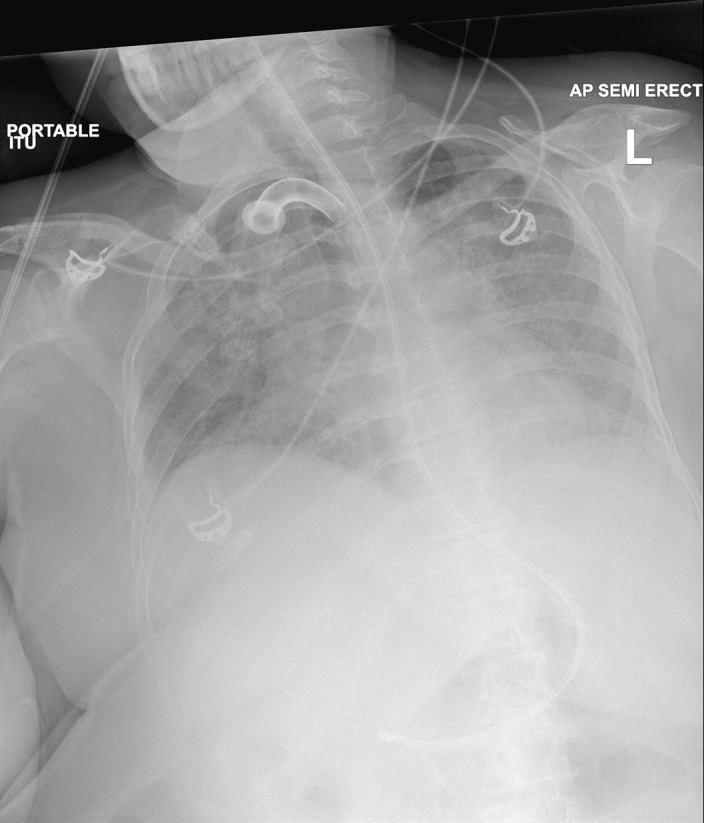

Following admission onto the CCU, a CXR was taken to assess the aetiology of the patient’s deterioration. When compared with the CXR taken on presentation in the A&E department (figure 1), the results revealed diffuse worsening of interstitial infiltrates with new lobar pneumonia (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Admission to critical care (2 August 2018).

A CTPA was undertaken to exclude pulmonary embolism, lung mass or endobronchial lesions. The results of this investigation excluded these conditions.

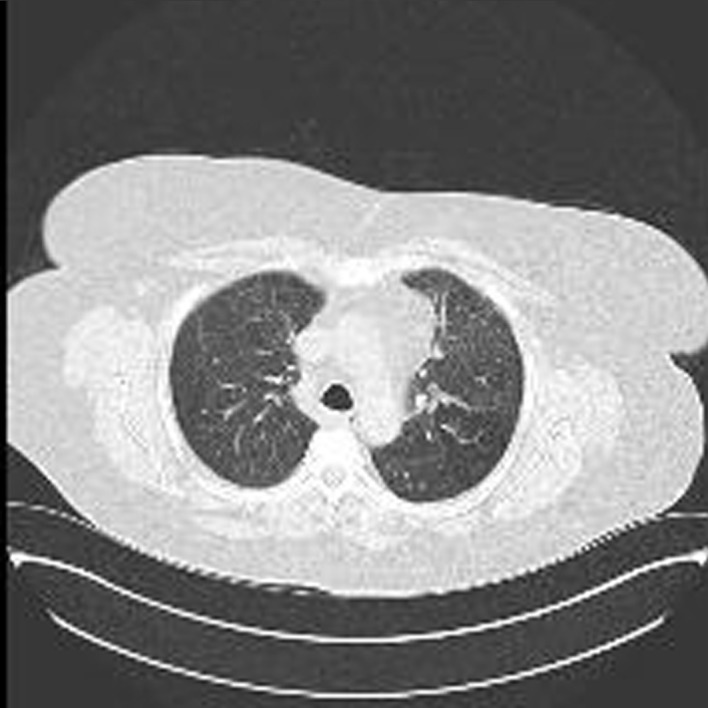

High-resolution CT

The high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest scan to specifically assess the lung parenchyma revealed extensive and diffuse ground-glass changes bilaterally (2 August 2018) (figure 3). This had progressed since previous CT scans with greater involvement of the left apex and right-lower lobe with small bilateral pleural effusions and infrequent enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes which were reactive in nature. Mild calcification of the left anterior descending artery was seen. The heart appeared enlarged and an echocardiogram was arranged.

Figure 3.

High-resolution CT scan (2 August 2018).

Microbiology and serology tests

Acid-fast bacillus stain to rule out Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative. Hepatitis, HIV, mycoplasma and cytomegalovirus serology were negative. Urinary antigen screening for legionella was negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening was negative for adenovirus and influenza but detected Pneumocystis, requiring treatment with cotrimoxazole. A precipitin serology result for heteropolysaccharide galactomannan to rule out invasive aspergillosis was negative. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to exclude sarcoidosis a vasculitis screen and Henoch-Schönlein purpura auto immune screen were also negative as were antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Six months prior to admission, the total immunoglobulin (IgE) was 47.40kU/L which had increased on admission to 74.00kU/L, though neither result was significantly raised (<114 kU/L). Serology testings for exposure to avian contact (budgerigar serum proteins, feathers and droppings were <2.0 mgA/L and pigeon proteins 3.1 mg A/L [<40 mg/A/L]) were insignificant.

Differential diagnosis

Though interstitial pulmonary fibrosis was initially considered due to the gradual onset of non-specific symptoms and increased dyspnoea, the presence of a productive cough, fever and the crepitations heard on auscultation directed the admitting team to a diagnosis of community acquired pneumonia. The progressive hypoxia that developed over the following days prompted a CTPA and chest HRCT and the diagnosis of HP became clear following these. In addition, caspofungin was prescribed for suspected invasive aspergillus infection but later stopped.

After exhausting all other possible causes of HP and ILD with extensive allergen and autoimmune testing, the possibility of this being an adverse drug reaction was considered and assessed. Sertraline was identified as a possible cause of HP following a literature review that included some limited case reports of an association with HP.1–5

Treatment

Throughout her 2-month stay in Critical Care, there had only been marginal improvement in her respiratory function despite aggressive antibiotic and steroid treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

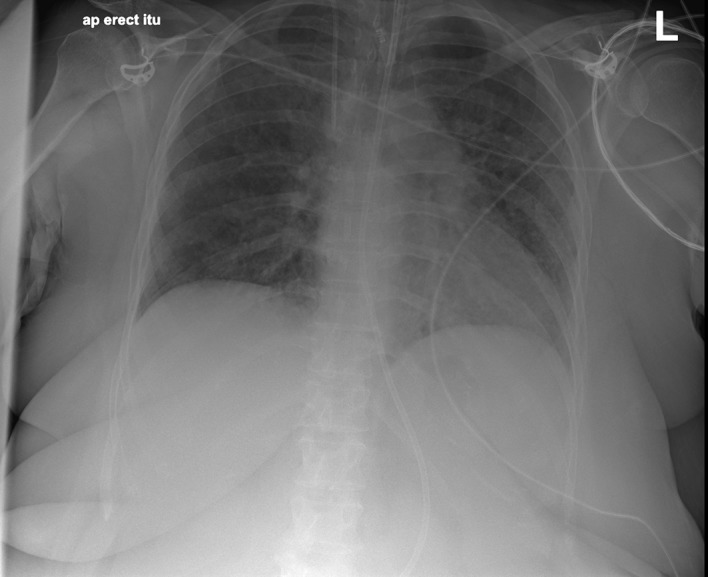

At a morning ward round one of the authors (GV) suggested sertraline as a cause of HP and after a literature review, the sertraline was stopped (26 September 2018), following consultation with the psychiatry team. This resulted in a remarkably prompt improvement of respiratory function. Respiratory rate, FiO2, PaCO2 and oxygen saturations (>90%) all started to improve within a few days. She was weaned from the ventilator and her tracheostomy removed on 2 October 2018, discharged from Critical Care to the ward on 3 October and home on 8th October 2018. A chest X-ray (figure 4) and a chest HRCT (figure 5) a few days before discharge demonstrated almost complete resolution of the pulmonary infiltrates. An adverse drug reaction (‘yellow card’) was reported to the Medicines and Healthcare Product Regulatory Agency (MHRA).6

Figure 4.

On discharge (4 October 2018).

Figure 5.

High-resolution CT (4 October 2018).

Discussion

This case report highlights the link between HP and sertraline. HP is a complex, rare and underdiagnosed immune-mediated pulmonary syndrome usually associated with exposure to inhaled extrinsic allergen(s) producing a severe exaggerated granulomatous inflammatory response within the alveoli of the lung parenchyma (interstitium, bronchioli and alveoli).7 During the inflammatory response, proinflammatory mediators such as thromboxane-A2 derived cytokines (TNF-α, IL-12 and IFN-ϒ) are released.8 An American study highlighted that HP was prevalent in 1.39–2.06 cases per 100 000 people with most individuals being female (52%–60%) and 25–55 years old.9

There is limited evidence to suggest medication as a cause of HP, as it is usually associated with an extrinsic inhaled allergen (table 3); however, the literature indicates that a cause is unable to be found in 30%–60% of reported cases.8 ILD is listed as a rare adverse reaction associated with sertraline (>1/10 000 to <1/1000) in the summary of product characteristics (SPC),10 and the MHRA has documented 359 respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders, five of which have been allergic alveolitis, ILD and pulmonary fibrosis; however, these statistics are likely to be an under-reported representation.6

Table 3.

Causative factors related to HP9

| Avian dust | Water |

| Mould | Maple bark dust |

| Paint catalyst | Redwood bark dust |

| Sugar cane dust | Beer brewing |

| Hay dust | Cork dust |

| Mushrooms | Plastic residue |

| Rat or gerbil urine | Epoxy resin |

| Tobacco | Enzyme detergents |

| Heating and cooling systems | Wheat mould |

HP, hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Mechanism of action SSRI in lung disease

There are several non-specific pathways in which SSRIs can precipitate bronchioles and capillary alveoli injury by oxidation, cytotoxic mechanisms and immune-response mediation.11 12 Accumulation of medication may be due to genetic factors such as P450 cytochrome and Mucin-5B (MUC5B) promoter polymorphisms that may predispose an individual to lung parenchyma injury with SSRIs.12 However, MUC5B is not routinely analysed in practice.

Supporting literature

There are reported cases of sertraline associated lung disease (pulmonary fibrosis, ILD and bronchiectasis), though specific reports of sertraline and HP is limited. One case report highlighted a 49-year-old woman who developed acute eosinophilic pneumonia with sertraline and successively improved after withdrawal of the causative agent.12 A 33-year-old Asian male taking sertraline (50 mg/day) and risperidone (2 mg/day) developed pulmonary fibrosis due to eosinophilic pneumonia, confirmed via a lung biopsy, had returned to baseline function after withdrawal of the medications.5

A case series of 296 patients, from a single elderly care (>70 years old) practice in America, demonstrated an positive correlation between the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the development of ILD and bronchiectasis (OR=8.79)13 but not HP. However, only one of these patients was taking sertraline. Patients included in the study were double the age of the patient reported in case and therefore may have exhibited different physiological, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics.

A 92-year-old woman receiving a SSRI (venlafaxine 75 mg daily) for depression, developed severe breathlessness and poor mobility with no improvement to oxygen saturation after receiving furosemide. When the venlafaxine was withdrawn her symptoms were restored to baseline level.14 Venlafaxine3 and paroxetine4 associated lung disease has also been discussed by other studies and an association between fluoxetine and ILD has been noted in animal studies.2

In conclusion, this case report highlights the importance of recognising drug-induced respiratory conditions, particularly in a critical care setting.

Learning points.

Recognise the clinical signs and symptoms of patients presenting with hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Understand pathophysiology of hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Consider sertraline and related selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a possible cause for hypersensitivity pneumonitis particularly in an intensive care setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the radiology department at Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospital for helping with the imaging particulary Duncan Smith and doctor Adele Lemieux-Morris for interpreting the imaging.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The value of white cell count in range column has been corrected from "4 November" to "4-11" in table 1. The value of PaO2 in range column has also been corrected from "15 December" to "12-15" in table 2.

Contributors: GV: contribution to the design and conception of work as well as data collection and analysis and writing of report. Responsible for pharmaceutical care issues throughout admission. JB: responsible for critical care management throughout patient’s admission. Contributed to revising the draft documentation. Provided final approval of the version published. MI: contribution to documentation and psychiatric management of patient throughout admission. Provided final approval of the version published. EG-C: overseeing GV on case report. Contributed to revising the draft documentation and critical care management throughout admission. Provided final approval of the version published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Turner RC, Nelson JE, Roberts BT, et al. Venlafaxine-Associated interstitial pneumonitis. Pharmacotherapy 2005;25:626–9. 10.1592/phco.25.4.626.61029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Capelozzi MA, Leick-Maldonado EA, Parra ER, et al. Morphological and functional determinants of fluoxetine (Prozac)-induced pulmonary disease in an experimental model. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2007;156:171–8. 10.1016/j.resp.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferreira PG, Costa S, Dias N, et al. Simultaneous interstitial pneumonitis and cardiomyopathy induced by venlafaxine. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia 2014;40:313–8. 10.1590/S1806-37132014000300015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xue-Fen C, Peng S, Li J, et al. Ijcep.com, 2018. Available: http://www.ijcep.com/files/ijcep0018676.pdf [Accessed 29 Nov 2018].

- 5. Thornton C, Maher TM, Hansell D, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis associated with psychotropic drug therapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2009;3 10.1186/1752-1947-3-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk Yellow Card Scheme - MHRA, 2018. Available: https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/idap/ [Accessed 28 Nov 2018].

- 7. Baur X, Fischer A, Budnik LT. Spotlight on the diagnosis of extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis). J Occup Med Toxicol 2015;10 10.1186/s12995-015-0057-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nogueira R, Melo N, Novais E, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: antigen diversity and disease implications. Pulmonology 2019;25 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selman M, Pardo A, King TE. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:314–24. 10.1164/rccm.201203-0513CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Medicines.org.uk Sertraline 50mg film-coated Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (eMC) [Internet], 2018. Available: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3501/smpc [Accessed 14 Oct 2018].

- 11. Nassri AB, Harford P. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia secondary to sertraline use. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:A1661. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Riario Sforza GG, Marinou A. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a complex lung disease. Clin Mol Allergy 2017;15 10.1186/s12948-017-0062-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenberg T, Lattimer R, Montgomery P, et al. The relationship of SSRI and SNRI usage with interstitial lung disease and bronchiectasis in an elderly population: a case-control study. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:1977–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kornum JB, Christensen S, Grijota M, et al. The incidence of interstitial lung disease 1995–2005: a Danish nationwide population-based study. BMC Pulm Med 2008;8:24 10.1186/1471-2466-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]