Abstract

The Na+/iodide (I−) symporter (NIS), a glycoprotein expressed at the basolateral plasma membrane of thyroid follicular cells, mediates I− accumulation for thyroid hormonogenesis and radioiodide therapy for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. However, differentiated thyroid tumors often exhibit lower I− transport than normal thyroid tissue (or even undetectable I− transport). Paradoxically, the majority of differentiated thyroid cancers show intracellular NIS expression, suggesting abnormal targeting to the plasma membrane. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the mechanisms that regulate NIS plasma membrane transport would have multiple implications for radioiodide therapy. In this study, we show that the intracellularly facing carboxy-terminus of NIS is required for the transport of the protein to the plasma membrane. Moreover, the carboxy-terminus contains dominant basolateral information. Using internal deletions and site-directed mutagenesis at the carboxy-terminus, we identified a highly conserved monoleucine-based sorting motif that determines NIS basolateral expression. Furthermore, in clathrin adaptor protein (AP)-1B–deficient cells, NIS sorting to the basolateral plasma membrane is compromised, causing the protein to also be expressed at the apical plasma membrane. Computer simulations suggest that the AP-1B subunit σ1 recognizes the monoleucine-based sorting motif in NIS carboxy-terminus. Although the mechanisms by which NIS is intracellularly retained in thyroid cancer remain elusive, our findings may open up avenues for identifying molecular targets that can be used to treat radioiodide-refractory thyroid tumors that express NIS intracellularly.

The ability of thyroid follicular cells to concentrate iodide (I−), an essential constituent of thyroid hormones, relies on functional expression of the Na+/I− symporter (NIS) at the basolateral plasma membrane (1). NIS-mediated active I− transport is electrogenic and uses as its driving force the Na+ gradient generated by the Na+/K+ ATPase to simultaneously transport one I− and two Na+ into the cells (2). The experimentally tested NIS secondary structure model predicts a hydrophobic 13-transmembrane segment glycoprotein with an extracellularly facing amino-terminus and a large intracellularly facing carboxy-terminus (3). NIS is N-glycosylated at three asparagine residues: N225 (third extracellular loop) and N489 and N502 (sixth extracellular loop) (3, 4). Underscoring the significance of NIS for thyroid physiology, naturally occurring loss-of-function variants of the SLC5A5 gene, which encodes NIS, a 643-amino acid protein, cause dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism due to impaired I− accumulation in thyroid follicular cells (5).

The ability of thyroid cells to accumulate I− constitutes the molecular basis for diagnosis and treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer (6). Retrospective studies demonstrated that radioiodide accumulation in tumor cells is the best indicator of disease-free survival (7–9). However, differentiated thyroid tumors often exhibit reduced (or even undetectable) I− transport compared with normal thyroid tissue and are diagnosed as cold nodules on thyroid scintigraphy. Complete loss of I− accumulation—causing thyroid tumors to become refractory to radioiodide therapy—is associated with poor prognosis; patients with thyroid cancer metastases that accumulate I− show a survival rate at 10 years of ∼56%, whereas the survival is drastically reduced to ∼10% in patients with radioiodide refractory metastases (8). Paradoxically, immunohistochemical analysis showed that most cold thyroid nodules express lower, normal, and even higher NIS levels compared with adjacent normal tissue, but NIS is mainly located in intracellular compartments, indicating that it is not properly targeted to the plasma membrane (10–16). Significantly, loss-of-function NIS variants have not been identified either in benign cold thyroid nodules or in thyroid cancer (13, 17), demonstrating that the intracellular retention of NIS is not caused by structural defects. Therefore, considering that radioiodide therapy efficiency is ultimately dependent on functional NIS plasma membrane expression in tumor cells (18), understanding the mechanisms that regulate NIS targeting to the cell surface has important implications for thyroid cancer treatment.

Despite their clinical relevance, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying NIS plasma membrane expression. The elucidation of these mechanisms could lead to therapeutic interventions to increase radioiodide therapy efficiency. Recently, Darrouzet et al. (19) reported a systematic evaluation of potential NIS intracellularly located short linear motifs presumably involved in the transport of the protein to the plasma membrane. These authors identified an internal noncanonical PDZ-binding motif comprising residues 118 to 121, located in the intracellular loop 2, which plays a crucial role in NIS plasma membrane expression, as its disruption by the substitution L121A leads to complete retention of the NIS mutant in the endoplasmic reticulum. Significantly, although also located in intracellular loop 2, but not within the mentioned noncanonical PDZ-binding motif, R124—an extensively characterized residue after the identification of R124H NIS in patients with impaired I− accumulation in the thyroid tissue—is critical for the local folding required for NIS sorting through the endoplasmic reticulum quality-control system (20). Moreover, functional characterization of the dyshormonogenic congenital hypothyroidism-causing loss-of-function NIS variant S509Rfs*6, reported in the literature as S515X NIS, revealed that the segment between positions S509 and L643, which includes transmembrane segment 13 and the carboxy-terminus, contains crucial information for NIS plasma membrane expression (21).

In this study, we investigated the role of the carboxy-terminus in NIS transport to the plasma membrane in nonpolarized and polarized epithelial cells. Our results indicate that the segment between I546 and K618 contains determinants required for NIS exit from the endoplasmic reticulum and its subsequent transport to the plasma membrane in nonpolarized epithelial cells. Moreover, our findings show that the segment between E578 and L583 constitutes a conserved monoleucine-based sorting motif essential for NIS transport to the basolateral plasma membrane in polarized epithelial cells. Further, the epithelial-specific clathrin adaptor protein (AP)-1B is required for NIS sorting exclusively to the basolateral surface.

Materials and Methods

Expression vectors and site-directed mutagenesis

Amino-terminus hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged human and rat NIS cDNAs cloned in the expression vector pcDNA3.1 minus were as described (22). Carboxy-terminus NIS deletion mutants E578_K618del and G634_Q639del NIS (19) were subcloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1 minus. Large deletion mutants were generated by inverse PCR with two inverted tail-to-tail primers to amplify the entire plasmid except for the region to be deleted using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore, Temecula, CA). Point mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis with oligonucleotides carrying the desired mutation using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore) (23). All constructs were sequenced to verify specific nucleotide substitutions (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea).

Cell culture and transfections

Type II Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Caplan (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT). μ1B knocked-down type II MDCK cells were kindly provided by Dr. Enrique Rodriguez-Boulan (Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY) (24). MDCK cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The thyroid cell lines Fischer rat thyroid cell line 5 (FRTL-5) (American Type Culture Collection CRL-1468) and Fischer rat thyroid (FRT) epithelial cells, kindly provided by Dr. Pilar Santisteban (Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas Alberto Sols, Madrid, Spain), were cultured in DMEM/Ham F-12 medium supplemented with 5% calf serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mIU/mL bovine TSH (National Hormone and Peptide Program), 10 μg/mL bovine insulin, and 5 μg/mL bovine transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (25, 26). Cell lines were transiently transfected at the ratio of 4 µg plasmid/10-cm dish using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (27). Stable polyclonal cell populations expressing wild-type (WT) and mutant NIS proteins were selected and propagated in media containing 1 g/L G418 (Sigma-Aldrich). For polarized culture, stably transfected cells were plated on 12-mm Transwell polyester 0.4-μm pore size filter units (Corning, Corning, NY) at a density of 250,000 cells/insert and cultured for 7 to 9 (MDCK) or 4 to 5 (FRT) days to differentiate into fully polarized epithelial monolayers with differential apical and basolateral plasma membrane domains (28).

Steady-state I− transport assays

Cells were incubated in Hanks balanced salt solution containing 10 μM I− supplemented with 50 μCi/μmol 125I− (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for 30 minutes at 37°C (29). NIS-specific I− uptake was assessed in the presence of 40 μM perchlorate. Accumulated radioiodide was extracted with ice-cold ethanol and then quantified in a Triathler Gamma Counter (Hidex, Turku, Finland). The amount of DNA was determined by the diphenylamine method after trichloroacetic acid precipitation (30). I− uptake was expressed as picomoles of I− per microgram DNA and standardized by NIS expression, as analyzed by flow cytometry under permeabilized conditions.

Flow cytometry

Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5 μg/mL rabbit monoclonal anti–HA-Tag (catalog number 3724; RRID: AB_1549585; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) (31) antibody in PBS containing 0.2% human serum albumin (32). For analysis under permeabilized conditions, an additional 0.2% saponin was added. After washing, cells were incubated with 1 μg/mL Alexa 488–conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (catalog number A-11008; RRID: AB_143165; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (33). The fluorescence of ∼5 × 104 events/tube was assayed in a BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). The relative plasma membrane expression of WT or mutant NIS was calculated as the ratio (plotted as percentage) of the median fluorescence intensity of the protein expression assessed under nonpermeabilized (plasma membrane) and permeabilized (total) conditions.

Immunofluorescence

Cells seeded onto glass coverslips were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and stained with 1 μg/mL rabbit monoclonal anti–HA-Tag (catalog number 3724; RRID: AB_1549585; Cell Signaling Technology) (31), 0.2 µg/mL rat monoclonal anti-HA (catalog number 3F10; RRID: AB_2314622; Roche) (34), 0.5 μg/mL rabbit monoclonal anti–E-cadherin (catalog number 3195, RRID: AB_2291471; Cell Signaling Technology) (35), 0.5 μg/mL rabbit monoclonal anti–β-catenin (catalog number 9582; RRID: AB_823447; Cell Signaling Technology) (36), or 2 μg/mL mouse monoclonal anti-SEKDEL epitope (catalog number sc-58774; RRID: AB_784161; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (37) antibodies in PBS containing 0.2% human serum albumin and 0.1% Triton X-100 (38). Secondary staining was performed with 2 μg/mL anti-rabbit or rat Alexa 488–conjugated and anti-mouse Alexa 598–conjugated antibodies (catalog number A-11008, RRID: AB_143165; catalog number A-11006, RRID: AB_141373; and catalog number A-11032, RRID: AB_141672; Molecular Probes) (33, 39, 40). Nuclear DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes). Coverslips were mounted with FluorSave Reagent (EMD Millipore), and images were acquired on an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). Percentage distribution of NIS mutants at the apical and basolateral plasma membrane was quantified in a minimum of three representative orthographic projections using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), as previously reported (41)

Deglycosylation assays and immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysates were deglycosylated with endo-β-acetylglucosaminidase H (Endo H; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in 50 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.5) (42). SDS-PAGE, electrotransference to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotting were performed as previously described (43). Membranes were blocked and incubated with 0.25 μg/mL affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-human NIS antibody (44). After washing, membranes were further incubated with 0.07 μg/mL goat anti-rabbit IRDye 680RD secondary antibody (catalog number 926-68071; RRID: AB_10956166; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) (45). Membranes were visualized and quantified by the Odyssey IR Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Structural modeling and bioinformatic analyses

Short linear motifs were predicted using the Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource (http://elm.eu.org). The NIS homology model used was based on the crystal structure of the Vibrio parahaemolyticus sodium/galactose cotransporter (46). Monoleucine-based sorting motif NIS-containing nonapeptide P576 to D584 complexed with the AP-1 σ1-subunit (Protein Data Bank identification 4P6Z) (47) was modeled using MODELER software (48). Molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the Amber molecular dynamics package and force field in explicit water as reported (49). The interaction of NIS peptides complexed with the AP-1 σ1-subunit was simulated for 20 ns without restraints. Trajectory data analyses were performed with the CPPTRAJ program of the AmberTools package (50). Molecular mechanics-generalized Born/surface area calculations were performed to estimate binding energy using data derived from molecular dynamics trajectories with the MMPBSA.py script of the AmberTools package (51). Images were prepared using Visual Molecular Dynamics software (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistical tests were performed using Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Multiple-group analysis was conducted by one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons post hoc test. Comparisons between two groups were made using paired Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

The NIS carboxy-terminus contains structural determinants required for plasma membrane expression

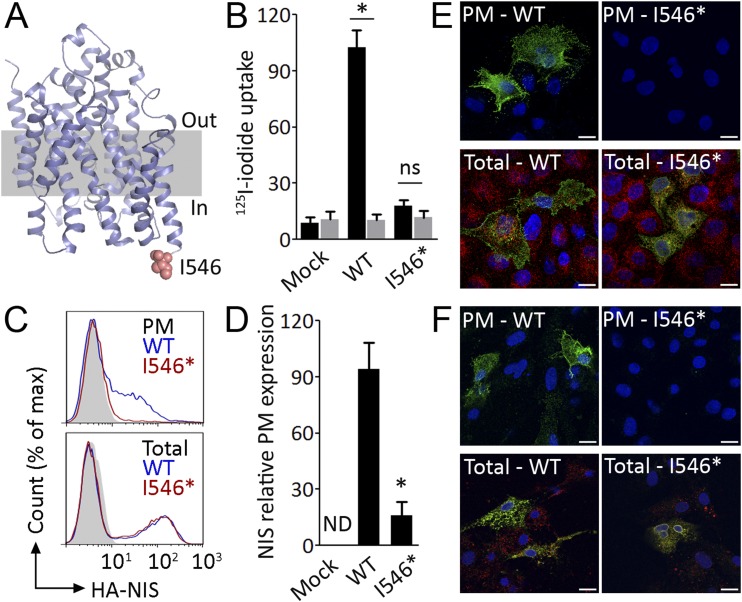

Based on our homology model (46), the intracellularly facing NIS carboxy-terminus comprises residues I546 to L643 (Fig. 1A). Thereafter, to ascertain the role of the carboxy-terminus in NIS transport to the plasma membrane, we generated a human NIS deletion mutant missing the entire carboxy-terminus (I546* NIS) and investigated its expression and function in stably transfected nonpolarized MDCK cells, which do not express NIS endogenously (52). Significantly, I546* NIS-expressing cells exhibited undetectable I− transport in contrast to those expressing full-length WT human NIS (Fig. 1B). Competitive inhibition with perchlorate confirmed that I− transport was mediated by NIS (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Deletion of the carboxy-terminus reduces NIS plasma membrane expression. (A) NIS homology model highlighting the beginning of the carboxy-terminus at position I546 (pink). (B) Steady-state I− uptake in nonpolarized MDCK cells permanently expressing empty vector (Mock) or WT or I546* NIS. Cells were incubated with 10 μM I− in the absence (black bars) or presence (gray bars) of 40 μM perchlorate. Results are expressed in pmol of I−/μg of DNA ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test). (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis (histogram) of WT or I546* NIS expression in nonpolarized MDCK cells under nonpermeabilized [plasma membrane (PM)] and permeabilized (total) conditions. Mock-transfected cells are represented in solid gray. (D) Relative WT or I546* NIS expression at the PM assessed by flow cytometry under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions. Data are mean ± SEM of a minimum of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test). Representative immunofluorescence analysis of WT or I546* NIS (green) expression in nonpolarized (E) MDCK and (F) FRTL-5 cells under nonpermeabilized (top panels) and permeabilized (bottom panels) conditions. Colocalization of WT or I546* NIS (green) with the endogenous endoplasmic reticulum marker KDEL (red) was assayed under permeabilized conditions. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 µm. ND, nondetected; ns, nonsignificant.

Flow cytometry analysis using an anti-HA antibody directed against an engineered HA-Tag at the extracellular amino terminus of human NIS, in nonpermeabilized cells, showed that the levels of I546* NIS at the plasma membrane were markedly lower than those of WT NIS (Fig. 1C, top panel, and 1D). By contrast, flow cytometry analysis under permeabilized conditions showed similar expression levels for both proteins (Fig. 1C, bottom panel). Additionally, immunofluorescence staining performed under nonpermeabilized conditions to ascertain NIS expression at the plasma membrane only showed immunoreactivity in cells expressing WT NIS (Fig. 1E, top panel), indicating that most I546* NIS was intracellularly located, whereas WT NIS was expressed mostly at the plasma membrane. Moreover, colocalization experiments with the endogenous endoplasmic reticulum marker retention signal KDEL revealed that I546* NIS was retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1E, bottom panel). In a complementary manner, we validated our observations in the highly differentiated nonpolarized rat thyroid cell line FRTL-5 transiently transfected to express WT or I546* NIS. Immunofluorescence analysis under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions showed that I546* NIS is mostly retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1F). Hence, the carboxy-terminus may anchor NIS-interacting proteins required for NIS transport to the plasma membrane.

The segment between amino acids 546 and 618 is required for NIS exit from the endoplasmic reticulum

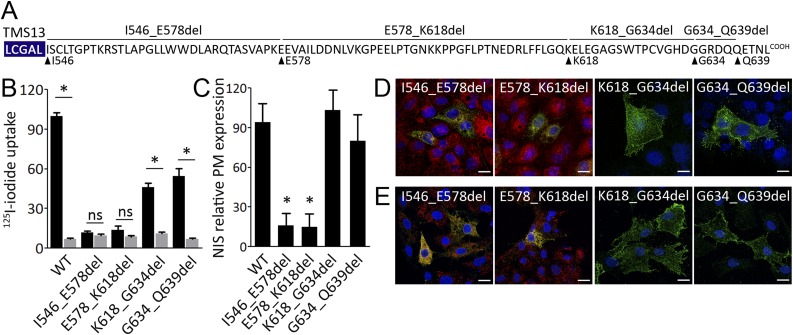

Given the role of the carboxy-terminus in NIS transport to the plasma membrane, we generated several NIS mutants missing regions of the carboxy-terminus (I546_E578del, E578_K618del, K618_G634del, and G634_Q639del NIS) to determine the segments of the carboxy-terminus required for the transport of the protein to the cell surface (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Deletion of the proximal carboxy-terminus causes NIS to be retained intracellularly. (A) Scheme of NIS carboxy-terminus sequence indicating internal deletion mutants. The blue box indicates the last sequence of NIS transmembrane segment (TMS) 13. (B) I− uptake in nonpolarized MDCK cells stably expressing WT, I546_E578del, E578_K618del, K618_G634del, or G634_Q639del NIS. Results are expressed in pmol of I−/μg of DNA ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test). (C) Relative WT or mutant NIS expression at the plasma membrane (PM) assessed by flow cytometry under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test). Representative immunofluorescence analysis of mutant NIS protein expression in nonpolarized (D) MDCK and (E) FRTL-5 cells. (D and E, right panels) Immunostaining of K618_G634del and G634_Q639del NIS (green) was assessed under nonpermeabilized conditions. (D and E, left panels) Coimmunostaining of I546_E578del and E578_K618del NIS (green) with endoplasmic reticulum marker KDEL (red) was assessed under permeabilized conditions. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 µm. ns, nonsignificant.

Perchlorate-sensitive I− transport was undetectable in nonpolarized MDCK cells permanently expressing I546_E578del or E578_K618del NIS in contrast to those expressing WT NIS (Fig. 2B), whereas cells stably expressing the NIS mutants K618_G634del or G634_Q639del accumulated I− (Fig. 2B). Moreover, flow cytometry analysis under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions revealed that I546_E578del and E578_K618del NIS are properly expressed but barely detectable at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2C). Consistently with mutant NIS-mediated I− transport, K618_G634del and G634_Q639del NIS were expressed at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2C). Further, immunofluorescence analysis under nonpermeabilized conditions did not show immunoreactivity in cells expressing I546_E578del and E578_K618del NIS (data not shown), indicating that the mutants were intracellularly retained, whereas K618_G634del and G634_Q639del NIS were expressed at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2D, top panel). Colocalization experiments with the endogenous endomembrane compartment marker KDEL revealed that the NIS mutants I546_E578del and E578_K618del are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 2D, bottom panel). Complementarily, similar results were obtained in transiently transfected FRTL-5 thyroid cells (Fig. 2E). Hence, the carboxy-terminus segment between residues I546 and K618 is required for NIS exit from the endoplasmic reticulum and subsequent transport to the plasma membrane. Significantly, in silico analysis did not reveal putative short linear sequences involved in the export of plasma membrane proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum in the I546 to K618 segment (53). However, we found a putative di-acidic [D/E]x[D/E] endoplasmic reticulum export motif (E619 to E621) in the distal carboxy-terminus dispensable for the exit of the protein from the endoplasmic reticulum (54). Therefore, short linear endoplasmic reticulum-export motifs underlying NIS export from the endoplasmic reticulum remain unknown.

Amino acids 618 to 634 are dispensable for NIS transport to the basolateral plasma membrane

As previously mentioned, NIS expression in thyroid follicular cells is restricted to the basolateral plasma membrane, as I− required for thyroid hormone biosynthesis is accumulated from the bloodstream into thyroid cells. Therefore, we hypothesized that NIS carboxy-terminus might contain dominant basolateral sorting signals recognized by thyrocytes sorting machinery. As highly differentiated polarized thyroid epithelial cell lines are not available, MDCK cells, a well-established model epithelial cell line for studying mechanisms of polarized sorting of plasma membrane proteins (28), have been widely used to study the polarity of thyroid proteins. Indeed, polarized MDCK cell monolayers recapitulate the polarized expression of various proteins in thyrocytes, including the basolateral expression of NIS and the apical expression of thyroid peroxidase and sodium-dependent monocarboxylate transport (52, 55). Significantly, polarized MDCK cell monolayers were crucial to uncover that the environmental pollutant perchlorate is actively accumulated by NIS (56).

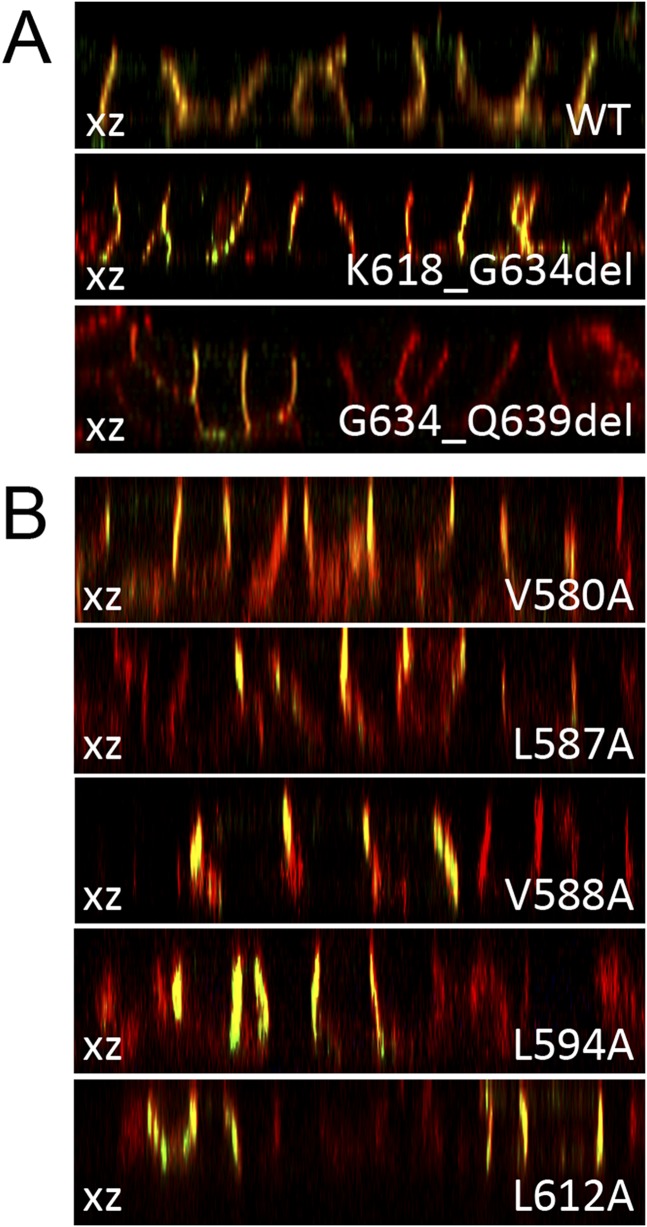

Hence, to assess the role of NIS carboxy-terminus in polarized transport to the basolateral plasma membrane, we grew monolayers of MDCK cells stably expressing the NIS mutants K618_G634del and G634_Q639del onto permeable supports to allow full polarization. We visualized the localization of NIS mutants by confocal microscopy, using E-cadherin as an endogenous basolateral marker. As previously reported (52), WT NIS is mostly expressed in the basolateral plasma membrane (basolateral expression: 95 ± 5%; apical expression: 5 ± 4%) (Fig. 3A). Because the NIS mutants K618_G634del and G634_Q639del were also mostly basolaterally expressed (Fig. 3A), we conclude that the distal carboxy-terminus (K618 to Q639) is dispensable for NIS basolateral expression.

Figure 3.

Amino acids 618 to 634 are dispensable for NIS transport to the basolateral plasma membrane. (A and B) Representative confocal microscopy analysis presented as orthographic projection (xz axis) of the expression of NIS mutants (green) in polarized MDCK cells under permeabilized conditions. Endogenous E-cadherin (red) was used as a basolateral marker.

Darrouzet et al. (19) reported that several conserved sorting motifs, located between amino acids E578 and K618, are not required for NIS transport to the plasma membrane in nonpolarized epithelial embryonic kidney 293T cells. To investigate whether these putative sorting motifs participate in the basolateral targeting of NIS, we generated MDCK cells stably expressing NIS mutants V580A, L587A, V588A, L594A, or L612A, which disrupt sorting motifs (19). All of these NIS mutants, however, were mostly expressed at the basolateral plasma membrane (Fig. 3B).

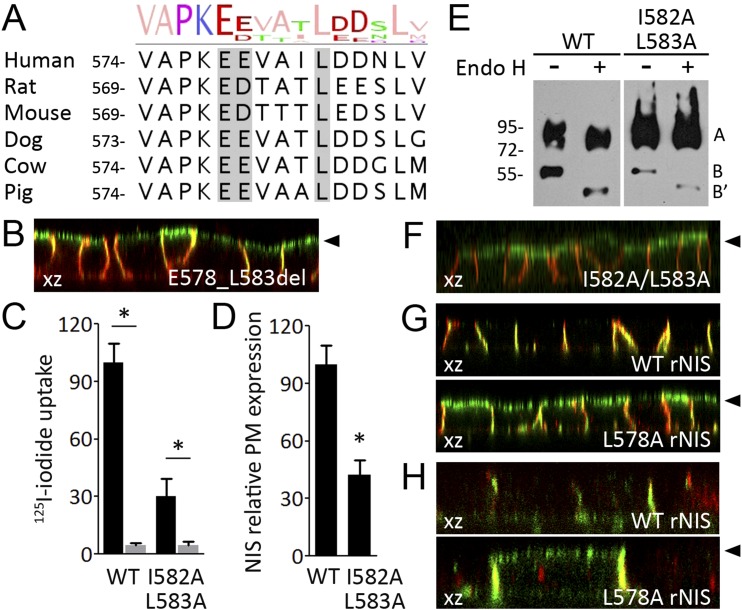

A conserved carboxy-terminus–located monoleucine-based sorting motif determines NIS basolateral expression

Although ectopic NIS expression in polarized MDCK cells is targeted to the basolateral plasma membrane, the rat NIS mutant missing the last 43 amino acids of the carboxy-terminus (T575* NIS) is dominantly expressed in the apical plasma membrane of polarized MDCK cells (56). This finding suggests that the region between amino acids T575 and L618 of the rat NIS carboxy-terminus (rat NIS has 618 amino acids) contains essential determinants for basolateral sorting. Therefore, considering that the segment between amino acids V580 (the residue equivalent to T575 in human NIS) and K618 would be critical for human NIS basolateral sorting, our subsequent studies focused on elucidating the role of these amino acids. In silico analysis revealed that canonical basolateral sorting motifs are not present between amino acids V580 and K618 of the human NIS carboxy-terminus. However, visual inspection of the sequence revealed a highly conserved putative basolateral sorting motif consisting of an acidic cluster followed by a single leucine (EExxxL) between amino acids 578 and 583 of human NIS (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, basolateral sorting motifs containing a monoleucine determinant assisted by an amino-terminal cluster of acidic amino acids (EDDxxxxxL or EExxxL) have been reported as critical for basolateral sorting of other proteins, such as stem cell factor (also named mast cell growth factor), colony-stimulating factor-1, basigin (also named CD147), and the epidermal growth factor receptor ligands amphiregulin and betacellulin (57–60). Hence, we generated MDCK cells stably expressing the human NIS mutant missing the segment between residues E578 and L583 (E578_L583del NIS) and assessed its expression in polarized cells. Significantly, deletion of the segment E578-L583 causes NIS to be expressed predominantly at the apical plasma membrane (basolateral expression: 40 ± 5%; apical expression: 67 ± 5%) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

A conserved monoleucine-based sorting motif determines NIS basolateral expression in polarized MDCK cells. (A) Alignment of multiple NIS sequences showing the degree of conservation. The conserved monoleucine-based basolateral sorting motif is indicated in solid gray. (B) Representative confocal microscopy analysis presented as orthographic projection of E578_L583del NIS (green) and endogenous E-cadherin (red) expression in polarized MDCK cells under permeabilized conditions. (C) Steady-state I− uptake in MDCK cells permanently expressing WT or I582A/L583A NIS. Results are expressed in pmol of I−/μg of DNA ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test). (D) Relative WT and I582A/L583A NIS expression at the plasma membrane (PM) assessed by flow cytometry under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test). (E) Representative immunoblot analysis of Endo H–treated whole-cell lysates from MDCK cells stably expressing WT or I582A/L583A NIS probed with anti-human NIS antibody. The broad appearance of the NIS polypeptides is typical of highly hydrophobic membrane proteins. Labels indicate the relative electrophoretic mobilities of the corresponding NIS polypeptides (row A: Endo H–resistant, fully glycosylated; rows B and B’: Endo H–sensitive, partially glycosylated before and after Endo H digestion) depending on glycosylation status. (F and G) Representative confocal microscopy analysis presented as orthographic projection (xz axis) of I582A/L583A human NIS or WT and L578A rat NIS (green) and endogenous E-cadherin (red) expression in polarized MDCK cells under permeabilized conditions. Filled arrowheads indicate the position of the apical membrane. (H) Representative confocal microscopy analysis presented as orthographic projection (xz axis) of WT and L578A rat NIS (green) and endogenous β-catenin (red) expression in polarized FRT cells under permeabilized conditions. Filled arrowheads indicate the position of the apical membrane.

Using site-directed mutagenesis, I582 and L583 were replaced with alanine residues (I582A/L583A NIS). Significantly, I582A/L583A NIS-expressing nonpolarized MDCK cells exhibited lower perchlorate-sensitive I− transport than those expressing WT NIS (Fig. 4C). Consistently, flow cytometry analysis, under nonpermeabilized and permeabilized conditions, revealed that the levels of I582A/L583A NIS at the plasma membrane were significantly lower than those of WT NIS (Fig. 4D). Together, these findings indicate that the functional defect resulting from these NIS mutations severely decreases the expression of the protein at the plasma membrane and consequently reduces I− accumulation. On Western blots, the fully glycosylated NIS polypeptide (90 to 100 kDa) was detected in I582A/L583A NIS-expressing cells, indicating that this mutant protein was fully processed (Fig. 4E). Consistent with this observation, most of the I582A/L583A polypeptide was resistant to Endo H (Fig. 4E), indicating that I582A/L583A is retained beyond the medial Golgi, where newly synthesized membrane proteins are sorted to different subcellular compartments. Moreover, under polarized conditions, most of the double-mutant I582A/L583A NIS protein was targeted to the apical plasma membrane (basolateral expression: 17 ± 10%; apical expression: 85 ± 2%) (Fig. 4F).

To extend our findings, we generated MDCK cells stably expressing WT rat NIS or the rat NIS L578A mutant to disrupt the monoleucine motif (EDxxxL) located between residues 573 and 578 (Fig. 4A). As expected, WT rat NIS was targeted to the basolateral plasma membrane (basolateral expression: 98 ± 2%; apical expression: 2 ± 1%) (Fig. 4G, top panel), whereas, in sharp contrast, L578A rat NIS was predominantly targeted apically (basolateral expression: 31 ± 5%; apical expression: 69 ± 6%) (Fig. 4G, bottom panel). Complementarily, we validated our observations in FRT cells that, although they do not express NIS endogenously, constitute the only thyroid follicular cell line that forms polarized epithelial monolayers when cultured onto permeable supports (26). In polarized FRT cells, WT rat NIS was mostly detected at the basolateral plasma membrane (basolateral expression: 93 ± 9%; apical expression: 8 ± 7%), whereas L587A rat NIS was detected on the apical and basolateral plasma membrane compartments (basolateral expression: 60 ± 5%; apical expression: 35 ± 3%) (Fig. 4H). Altogether, these results indicate that the monoleucine-based sorting motif, which is highly conserved across species, is critical for NIS basolateral expression.

The epithelial-specific clathrin adaptor AP-1B is required for NIS basolateral sorting

Linear peptide sorting motifs that target proteins to the basolateral plasma membrane (i.e., tyrosine-based or dileucine-based sorting motifs) are generally recognized by cytoplasmic adaptor proteins. Most commonly heterotetrameric clathrin AP complexes, particularly the AP-1A and AP-1B hemicomplex γ-σ1, recognize basolateral [D/E]xxxL[L/I] leucine-based consensus motifs (61). AP-1B expression is epithelial cell–specific and differs from the ubiquitous AP-1A by the medium subunit μ1B (24). AP-1B is localized in recycling endosomes and plays a major role in biosynthetic and recycling sorting of plasma membrane proteins to the basolateral plasma membrane domain (24). Therefore, to analyze the role of AP-1B in NIS transport to the basolateral plasma membrane, we assayed NIS expression in polarized μ1B-knocked down MDCK cells, which exhibit defective sorting of several basolateral markers to the apical domain (24), permanently expressing human NIS. Human NIS was detected predominantly at the apical plasma membrane compartment in polarized μ1B knocked-down MDCK cells (basolateral expression: 32 ± 7%; apical expression: 65 ± 7%) (Fig. 5A), in sharp contrast to the basolateral expression observed in MDCK cells (Fig. 3A). These results demonstrated that AP-1B is required for NIS sorting exclusively to the basolateral plasma membrane.

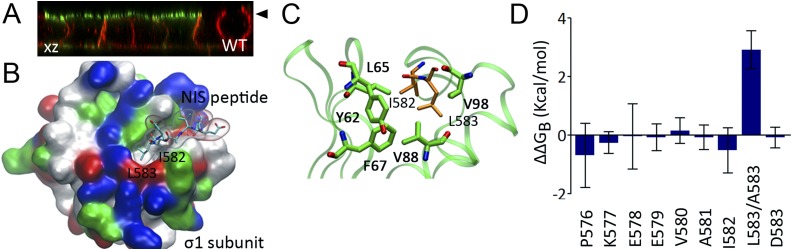

Figure 5.

The epithelial-specific clathrin adaptor AP-1B is required for NIS basolateral sorting. (A) Representative confocal microscopy analysis presented as orthographic projection (xz axis) of WT NIS (green) and endogenous E-cadherin (red) expression in polarized μ1B knocked-down MDCK cells. Filled arrowhead indicates the position of the apical membrane. (B) NIS monoleucine-based basolateral sorting motif bound to the AP-1 σ1-subunit presented in molecular surface colored by residue type. NIS peptide residues I582 and L583 are labeled. (C) Close-up of the hydrophobic monoleucine binding pocket of AP-1 σ1-subunit (green). Hydrophobic residues forming the monoleucine-binding site are labeled. (D) Per amino-acid residue contribution to the difference in binding free energy values (∆∆GB, Kcal/mol) between WT and L583A NIS nanopeptides complexed to the AP-1 σ1-subunit.

We performed computer simulations to gain structural insights into the interaction between the monoleucine motif-containing human NIS nonapeptide P576 to D584 and the leucine-based recognition pocket of AP-1 σ1-subunit (Fig. 5B). We built the corresponding complex using as template the crystal structure of AP-1 σ1-subunit bound to an HIV-1 viral protein u nonapeptide containing a leucine-based sorting motif (ExxxLV) (47). Molecular dynamics simulations show that the AP-1 σ1-subunit forms stable complexes with the NIS nanopeptide. As expected (47, 62), NIS peptide residues I582 and L583 were embedded into a hydrophobic groove formed by AP-1 σ1-subunit residues Y62, L65, F67, V88, and V98 (Fig. 5C). To determine the difference in affinity between WT and L583A NIS nanopeptides, we calculated the difference between the binding free energies of the peptides and the AP1 σ1-subunit (∆∆GB). The results show that the L583A mutant reduces the binding free energy by 2.9 ± 0.6 Kcal/mol (Fig. 5D), corresponding to an ∼20-fold reduction in the binding affinity, thus underscoring the role of L583 in the sorting motif. Our results suggest that the carboxy-terminus–located monoleucine-based sorting motif is recognized by the AP-1B adaptor complex and required for basolateral sorting of NIS in MDCK cells, a well-established model for studying the polarity of thyroid proteins.

Discussion

The ability of radioiodide therapy to ablate thyroid cancer ultimately depends on functional NIS expression at the plasma membrane of thyroid tumor cells. Although thyroid tumors often exhibit less I− transport than normal thyroid tissue, most differentiated thyroid tumors maintain different levels of NIS compared with the surrounding normal tissue (10–16). Surprisingly, NIS expression in tumor cells is mainly intracellular, indicating abnormalities in the transport of the protein to the plasma membrane. Therefore, from a therapeutic perspective, deepening our understanding of the mechanisms that regulate NIS transport to the plasma membrane must be a priority in the effort to improve NIS-mediated radioiodide therapy for thyroid cancer. Indeed, the development of strategies for enhancing this process, rather than stimulating NIS gene transcription, would be highly desirable, as defective transport of NIS to the plasma membrane plays a major role in making thyroid cancer refractory to radioiodide treatment. Importantly, therapeutic interventions allowing more NIS molecules to reach the plasma membrane of tumor cells would dramatically improve the efficacy of radioiodide therapy, thus making it possible to use lower doses of radioiodide, minimizing side effects (63), or to use radioiodide as an adjuvant to kinase inhibitors targeting oncogene-activated signaling pathways to recover NIS gene transcription (64).

In this study, we provide evidence on the significance of the carboxy-terminus of NIS for the expression of the protein at the plasma membrane in epithelial cells. We showed that the NIS mutant missing the entire carboxy-terminus does not mediate I− transport in nonpolarized MDCK due to its retention in the endoplasmic reticulum, not by lower mutant NIS protein expression. In nonpolarized MDCK cells, the carboxy-terminus segment between residues I546 and K618 contains unknown structural determinants required for NIS exit from the endoplasmic reticulum and subsequent transport to the plasma membrane. Moreover, the distal carboxy-terminus segment between amino acids K618 and Q639 is dispensable for NIS transport to the plasma membrane. Recently, Darrouzet et al. (19) reported the presence of a putative PDZ-binding motif [S/T]xΦCOOH located at the carboxy-terminal edge of the protein. However, it seems unlikely that the PDZ-binding motif is involved in NIS expression at the plasma membrane, as the addition of a carboxy-terminal epitope tag, which masks the carboxylate group required for the recognition of the PDZ motif, does not have any major effect on NIS cell surface expression (65, 66).

In thyroid follicular cells, it is physiologically essential for I− accumulation from the bloodstream into the epithelial cells that NIS be expressed at the basolateral plasma membrane. Therefore, the amino acid sequence of NIS must contain basolateral sorting determinants recognized by the sorting machinery of the thyroid follicular cell. In this study, we report the identification of a highly conserved monoleucine-based sorting motif located in the carboxy-terminus necessary for NIS basolateral sorting in polarized MDCK cells. Moreover, we uncovered the role of the adaptor protein AP-1B for NIS sorting to the basolateral plasma membrane, as we evidenced an aberrant apical delivery of NIS in polarized μ1B knocked-down MDCK cells. Unfortunately, because of technical limitations, we were unable to provide biochemical data demonstrating a physical interaction between NIS and the AP-1B adaptor, as yeast three-hybrid technique would have been required (24). However, we carried out computer simulations that suggest potential direct recognition of the monoleucine-based basolateral sorting motif by the AP-1 σ1 subunit. Taken together, our results are consistent with the idea that the adaptor protein AP-1B participates in the recognition of the monoleucine motif and NIS sorting from recycling endosomes to the basolateral plasma membrane.

Although NIS was initially thought to be a thyroid-specific protein, functional NIS protein expression was reported in several other tissues (i.e., salivary glands, stomach, small intestine, lactating breast, kidney, placenta, and ovary) (67). Considering different tissue-specific I−-handling requirements, NIS expression in different tissues also displays different basolateral-to-apical expression patterns. Therefore, uncharacterized factors other than the NIS sequence may regulate NIS sorting to the plasma membrane, such as posttranslational modifications or differential tissue expression of specific adaptor proteins that decode common sorting signals. Significantly, the absence of epithelial-specific AP-1B adaptor in renal proximal tubule epithelial cells determines that many cognate basolateral plasma membrane proteins are sorted to the apical membrane, thus optimizing the reabsorption of nutrients (68). We demonstrated that disruption of the carboxy-terminal monoleucine-based sorting motif causes NIS to be missorted to the apical plasma membrane in AP-1B–expressing polarized epithelial cells, indicating that this motif constitutes a sorting signal required for exclusively basolateral NIS expression. Moreover, NIS contains recessive apical sorting information that is overridden by a dominant monoleucine-based basolateral sorting motif in AP-1B–expressing polarized epithelial cells. Currently, a great deal remains unknown about sorting motifs and adaptor proteins involved in polarized transport of NIS to the apical brush border of small intestine enterocytes (69). The rat NIS mutant L578A, apically expressed in polarized monolayers of AP-1B–expressing epithelial cells, could constitute a starting point to reveal NIS apical sorting signals.

Whereas cell polarity is crucial for thyroid hormone biosynthesis, thyroid cancer cells undergo loss of polarization during their epithelial-mesenchymal transition (70). In nonpolarized cells (i.e., fibroblasts) the sorting of plasma membrane proteins from the trans-Golgi network to the plasma membrane also requires sorting motifs and adaptor proteins (71). Indeed, the NIS mutant I582A/L583A, which disrupts the monoleucine-based sorting motif, is mainly intracellularly retained after being sorted out of the medial Golgi in nonpolarized MDCK cells. Therefore, sorting motifs involved in basolateral protein delivery in polarized cells might also affect plasma membrane expression in nonpolarized cells. Therefore, the identification of the mechanism involved in NIS basolateral expression may be linked to the intracellular retention of the protein in thyroid cancer. Future work will determine whether AP-1B–dependent NIS monoleucine-based sorting motif recognition is deregulated in thyroid cancer and whether this has an impact on the plasma membrane expression of the protein.

As the carboxy-terminus is critical for NIS transport to the plasma membrane, we consider it clinically relevant to further investigate proteins that interact with the NIS carboxy-terminus, for which altered expression in thyroid cancer may cause NIS sorting defects. To date, the pituitary tumor-transforming gene binding factor (PBF) has been reported as the only NIS-interacting protein involved in NIS intracellular retention in thyroid tissue. Ectopic PBF overexpression resulted in reduced I− accumulation caused by NIS redistribution from the plasma membrane into clathrin-coated CD63-positive late endosomes (72). Proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase Src-mediated PBF phosphorylation is required for the physical interaction of PBF with NIS, as abrogation of Src kinase activity restores I− accumulation in thyroid cancer cell lines stably transfected with NIS (73). Moreover, Amit et al. (74) suggested that a functional defect in the glycosylphosphatidylinositol transamidase complex causes partially glycosylated NIS molecules to be retained in the endoplasmic reticulum, likely due to a deficiency in an unidentified glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein necessary for proper NIS export from the endoplasmic reticulum. Although the molecular mechanisms that determine NIS intracellular retention in thyroid cancer remain elusive, our findings highlighting the relevance of the carboxy-terminus for NIS expression at the plasma membrane open avenues to identify molecular targets to treat radioiodide-refractory thyroid tumors (75), particularly those showing intracellular NIS expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Caplan and Dr. Enrique Rodriguez-Boulan for providing WT and μ1B-knocked down type II MDCK cells, respectively, and Dr. Pilar Santisteban for providing FRT thyroid epithelial cells. We also thank Dr. Carlos Mas and Dr. Pilar Crespo from the Centro de Micro y Nanoscopía de Córdoba (CEMINCO-CONICET)–Universidad Nacional de Córdoba for imaging technical assistance. Lastly, we thank all of the members of our laboratories for providing technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Financial Support: M.M. was supported by international travelling fellowships from The Company of Biologists–Journal of Cell Science and the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. This work was supported by fellowships from Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (to M.M., C.P.M., and V.P.) and research grants from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT-2014-0726, PICT-2015-3839, and PICT-2015-3705 to J.P.N.), Instituto Nacional del Cáncer–Ministerio de Salud de la República Argentina, Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología–Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (30820150100222CB to J.P.N.), Latin American Thyroid Society and American Thyroid Association–Thyroid Cancer Survivors’ Association (2015-033 to J.P.N.), and National Institutes of Health Grant DK-41544 (to N.C.).

Author Contributions: M.M. performed experimental work and analyzed the data. C.P.M. and M.A.M. performed and analyzed computer simulations. V.P., R.C.G., and E.D. provided critical technical support. T.P., A.M.M.-R., and N.C. contributed with critical reagents and provided research training. N.C. and J.P.N. conceived the project. J.P.N. supervised the study, performed initial experimental work, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. M.M., C.P.M., V.P., R.C.G., E.D., T.P., A.M.M.-R., M.A.M., N.C., and J.P.N. participated in writing the manuscript and approved the final version.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AP

adaptor protein

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- Endo H

endo-β-acetylglucosaminidase H

- FRT

Fischer rat thyroid

- FRTL-5

Fischer rat thyroid cell line 5

- HA

hemagglutinin

- I−

iodide

- MDCK

Madin-Darby canine kidney

- NIS

Na+/iodide symporter

- PBF

pituitary tumor-transforming gene binding factor

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1. Nicola JP, Carrasco N, Amzel LM. Physiological sodium concentrations enhance the iodide affinity of the Na+/I- symporter. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ravera S, Quick M, Nicola JP, Carrasco N, Amzel LM. Beyond non-integer Hill coefficients: A novel approach to analyzing binding data, applied to Na+-driven transporters. J Gen Physiol. 2015;145(6):555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levy O, De la Vieja A, Ginter CS, Riedel C, Dai G, Carrasco N. N-linked glycosylation of the thyroid Na+/I- symporter (NIS). Implications for its secondary structure model. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(35):22657–22663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li W, Nicola JP, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. Asn441 plays a key role in folding and function of the Na+/I- symporter (NIS). FASEB J. 2013;27(8):3229–3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin M, Nicola JP. Congenital iodide transport defect: Recent advances and future perspectives. J Clin Mol Endocrinol. 2016;1:9. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reiners C, Hänscheid H, Luster M, Lassmann M, Verburg FA. Radioiodine for remnant ablation and therapy of metastatic disease [published correction appears in Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012;8(3):130]. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(10):589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mazzaferri EL. Thyroid remnant 131I ablation for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 1997;7(2):265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, Leboulleux S, Hartl D, Travagli JP, Caillou B, Ricard M, Lumbroso JD, De Vathaire F, Schlumberger M. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):2892–2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med. 1994;97(5):418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dohán O, Baloch Z, Bánrévi Z, Livolsi V, Carrasco N. Rapid communication: predominant intracellular overexpression of the Na(+)/I(-) symporter (NIS) in a large sampling of thyroid cancer cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(6):2697–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kollecker I, von Wasielewski R, Langner C, Müller JA, Spitzweg C, Kreipe H, Brabant G. Subcellular distribution of the sodium iodide symporter in benign and malignant thyroid tissues. Thyroid. 2012;22(5):529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wapnir IL, van de Rijn M, Nowels K, Amenta PS, Walton K, Montgomery K, Greco RS, Dohán O, Carrasco N. Immunohistochemical profile of the sodium/iodide symporter in thyroid, breast, and other carcinomas using high density tissue microarrays and conventional sections. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1880–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neumann S, Schuchardt K, Reske A, Reske A, Emmrich P, Paschke R. Lack of correlation for sodium iodide symporter mRNA and protein expression and analysis of sodium iodide symporter promoter methylation in benign cold thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 2004;14(2):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saito T, Endo T, Kawaguchi A, Ikeda M, Katoh R, Kawaoi A, Muramatsu A, Onaya T. Increased expression of the sodium/iodide symporter in papillary thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(7):1296–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tonacchera M, Viacava P, Agretti P, de Marco G, Perri A, di Cosmo C, de Servi M, Miccoli P, Lippi F, Naccarato AG, Pinchera A, Chiovato L, Vitti P. Benign nonfunctioning thyroid adenomas are characterized by a defective targeting to cell membrane or a reduced expression of the sodium iodide symporter protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(1):352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trouttet-Masson S, Selmi-Ruby S, Bernier-Valentin F, Porra V, Berger-Dutrieux N, Decaussin M, Peix JL, Perrin A, Bournaud C, Orgiazzi J, Borson-Chazot F, Franc B, Rousset B. Evidence for transcriptional and posttranscriptional alterations of the sodium/iodide symporter expression in hypofunctioning benign and malignant thyroid tumors. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Russo D, Manole D, Arturi F, Suarez HG, Schlumberger M, Filetti S, Derwahl M. Absence of sodium/iodide symporter gene mutations in differentiated human thyroid carcinomas. Thyroid. 2001;11(1):37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schlumberger M, Lacroix L, Russo D, Filetti S, Bidart JM. Defects in iodide metabolism in thyroid cancer and implications for the follow-up and treatment of patients. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(3):260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Darrouzet E, Graslin F, Marcellin D, Tcheremisinova I, Marchetti C, Salleron L, Pognonec P, Pourcher T. A systematic evaluation of sorting motifs in the sodium-iodide symporter (NIS). Biochem J. 2016;473(7):919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paroder V, Nicola JP, Ginter CS, Carrasco N. The iodide-transport-defect-causing mutation R124H: a δ-amino group at position 124 is critical for maturation and trafficking of the Na+/I- symporter. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 15):3305–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pohlenz J, Duprez L, Weiss RE, Vassart G, Refetoff S, Costagliola S. Failure of membrane targeting causes the functional defect of two mutant sodium iodide symporters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2366–2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paroder-Belenitsky M, Maestas MJ, Dohán O, Nicola JP, Reyna-Neyra A, Follenzi A, Dadachova E, Eskandari S, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. Mechanism of anion selectivity and stoichiometry of the Na+/I- symporter (NIS). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(44):17933–17938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peyret V, Nazar M, Martín M, Quintar AA, Fernandez EA, Geysels RC, Fuziwara CS, Montesinos MM, Maldonado CA, Santisteban P, Kimura ET, Pellizas CG, Nicola JP, Masini-Repiso AM. Functional toll-like receptor 4 overexpression in papillary thyroid cancer by MAPK/ERK-induced ETS1 transcriptional activity. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(5):833–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gravotta D, Deora A, Perret E, Oyanadel C, Soza A, Schreiner R, Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Boulan E. AP1B sorts basolateral proteins in recycling and biosynthetic routes of MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(5):1564–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rossich LE, Thomasz L, Nicola JP, Nazar M, Salvarredi LA, Pisarev M, Masini-Repiso AM, Christophe-Hobertus C, Christophe D, Juvenal GJ. Effects of 2-iodohexadecanal in the physiology of thyroid cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;437:292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koumarianou P, Goméz-López G, Santisteban P. Pax8 controls thyroid follicular polarity through cadherin-16. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(1):219–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nazar M, Nicola JP, Vélez ML, Pellizas CG, Masini-Repiso AM. Thyroid peroxidase gene expression is induced by lipopolysaccharide involving nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65 subunit phosphorylation. Endocrinology. 2012;153(12):6114–6125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G, Müsch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(3):233–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fozzatti L, Vélez ML, Lucero AM, Nicola JP, Mascanfroni ID, Macció DR, Pellizas CG, Roth GA, Masini-Repiso AM. Endogenous thyrocyte-produced nitric oxide inhibits iodide uptake and thyroid-specific gene expression in FRTL-5 thyroid cells. J Endocrinol. 2007;192(3):627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Serrano-Nascimento C, Nicola JP, Teixeira SS, Poyares LL, Lellis-Santos C, Bordin S, Masini-Repiso AM, Nunes MT. Excess iodide downregulates Na(+)/I(-) symporter gene transcription through activation of PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;426:73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.RRID:AB_1549585.

- 32. Nicola JP, Peyret V, Nazar M, Romero JM, Lucero AM, Montesinos MM, Bocco JL, Pellizas CG, Masini-Repiso AM. S-Nitrosylation of NF-κB p65 inhibits TSH-induced Na(+)/I(-) symporter expression. Endocrinology. 2015;156(12):4741–4754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.RRID:AB_143165.

- 34.RRID:AB_2314622.

- 35.RRID:AB_2291471.

- 36.RRID:AB_823447.

- 37.RRID:AB_784161.

- 38. Peinetti N, Scalerandi MV, Cuello Rubio MM, Leimgruber C, Nicola JP, Torres AI, Quintar AA, Maldonado CA. The response of prostate smooth muscle cells to testosterone is determined by the subcellular distribution of the androgen receptor. Endocrinology. 2018;159(2):945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.RRID:AB_141373.

- 40.RRID:AB_141672.

- 41. Wolff SC, Qi AD, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. Charged residues in the C-terminus of the P2Y1 receptor constitute a basolateral-sorting signal. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 14):2512–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nicola JP, Reyna-Neyra A, Saenger P, Rodriguez-Buritica DF, Gamez Godoy JD, Muzumdar R, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. Sodium/iodide symporter mutant V270E causes stunted growth but no cognitive deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(10):E1353–E1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Montesinos MM, Nicola JP, Nazar M, Peyret V, Lucero AM, Pellizas CG, Masini-Repiso AM. Nitric oxide-repressed Forkhead factor FoxE1 expression is involved in the inhibition of TSH-induced thyroid peroxidase levels. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;420:105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tazebay UH, Wapnir IL, Levy O, Dohan O, Zuckier LS, Zhao QH, Deng HF, Amenta PS, Fineberg S, Pestell RG, Carrasco N. The mammary gland iodide transporter is expressed during lactation and in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.RRID:AB_10956166.

- 46. Ferrandino G, Nicola JP, Sánchez YE, Echeverria I, Liu Y, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. Na+ coordination at the Na2 site of the Na+/I- symporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(37):E5379–E5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jia X, Weber E, Tokarev A, Lewinski M, Rizk M, Suarez M, Guatelli J, Xiong Y. Structural basis of HIV-1 Vpu-mediated BST2 antagonism via hijacking of the clathrin adaptor protein complex 1. eLife. 2014;3:e02362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen MY, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arcon JP, Defelipe LA, Modenutti CP, López ED, Alvarez-Garcia D, Barril X, Turjanski AG, Martí MA. Molecular dynamics in mixed solvents reveals protein-ligand interactions, improves docking, and allows accurate binding free energy predictions. J Chem Inf Model. 2017;57(4):846–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roe DR, Cheatham TE III. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9(7):3084–3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miller BR III, McGee TD Jr, Swails JM, Homeyer N, Gohlke H, Roitberg AE. MMPBSA.py: An efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3314–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang X, Riedel C, Carrasco N, Arvan P. Polarized trafficking of thyrocyte proteins in MDCK cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;188(1-2):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barlowe C. Signals for COPII-dependent export from the ER: what’s the ticket out? Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(6):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang X, Dong C, Wu QJ, Balch WE, Wu G. Di-acidic motifs in the membrane-distal C termini modulate the transport of angiotensin II receptors from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(23):20525–20535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Paroder V, Spencer SR, Paroder M, Arango D, Schwartz S Jr, Mariadason JM, Augenlicht LH, Eskandari S, Carrasco N. Na(+)/monocarboxylate transport (SMCT) protein expression correlates with survival in colon cancer: molecular characterization of SMCT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(19):7270–7275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dohán O, Portulano C, Basquin C, Reyna-Neyra A, Amzel LM, Carrasco N. The Na+/I symporter (NIS) mediates electroneutral active transport of the environmental pollutant perchlorate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(51):20250–20255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Deora AA, Gravotta D, Kreitzer G, Hu J, Bok D, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The basolateral targeting signal of CD147 (EMMPRIN) consists of a single leucine and is not recognized by retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(9):4148–4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wehrle-Haller B, Imhof BA. Stem cell factor presentation to c-Kit. Identification of a basolateral targeting domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(16):12667–12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gephart JD, Singh B, Higginbotham JN, Franklin JL, Gonzalez A, Fölsch H, Coffey RJ. Identification of a novel mono-leucine basolateral sorting motif within the cytoplasmic domain of amphiregulin. Traffic. 2011;12(12):1793–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Singh B, Bogatcheva G, Starchenko A, Sinnaeve J, Lapierre LA, Williams JA, Goldenring JR, Coffey RJ. Induction of lateral lumens through disruption of a monoleucine-based basolateral-sorting motif in betacellulin. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(18):3444–3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bonifacino JS. Adaptor proteins involved in polarized sorting. J Cell Biol. 2014;204(1):7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kelly BT, McCoy AJ, Späte K, Miller SE, Evans PR, Höning S, Owen DJ. A structural explanation for the binding of endocytic dileucine motifs by the AP2 complex. Nature. 2008;456(7224):976–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Reiners C, Luster M. Radiotherapy: radioiodine in thyroid cancer-how to minimize side effects. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(8):432–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Spitzweg C, Bible KC, Hofbauer LC, Morris JC. Advanced radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer: the sodium iodide symporter and other emerging therapeutic targets. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(10):830–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huc-Brandt S, Marcellin D, Graslin F, Averseng O, Bellanger L, Hivin P, Quemeneur E, Basquin C, Navarro V, Pourcher T, Darrouzet E. Characterisation of the purified human sodium/iodide symporter reveals that the protein is mainly present in a dimeric form and permits the detailed study of a native C-terminal fragment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(1):65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dayem M, Basquin C, Navarro V, Carrier P, Marsault R, Chang P, Huc S, Darrouzet E, Lindenthal S, Pourcher T. Comparison of expressed human and mouse sodium/iodide symporters reveals differences in transport properties and subcellular localization. J Endocrinol. 2008;197(1):95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. De la Vieja A, Santisteban P. Role of iodide metabolism in physiology and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(4):R225–R245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schreiner R, Frindt G, Diaz F, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Perez Bay AE, Palmer LG, Marshansky V, Brown D, Philp NJ, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The absence of a clathrin adapter confers unique polarity essential to proximal tubule function. Kidney Int. 2010;78(4):382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nicola JP, Carrasco N, Masini-Repiso AM. Dietary I(-) absorption: expression and regulation of the Na(+)/I(-) symporter in the intestine. Vitam Horm. 2015;98:1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Rodríguez I, De la Vieja A, Costamagna E, Carrasco N, Nistal M, Santisteban P. The BRAFV600E oncogene induces transforming growth factor beta secretion leading to sodium iodide symporter repression and increased malignancy in thyroid cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(21):8317–8325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Traub LM, Kornfeld S. The trans-Golgi network: a late secretory sorting station. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(4):527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Smith VE, Read ML, Turnell AS, Watkins RJ, Watkinson JC, Lewy GD, Fong JC, James SR, Eggo MC, Boelaert K, Franklyn JA, McCabe CJ. A novel mechanism of sodium iodide symporter repression in differentiated thyroid cancer. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 18):3393–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Smith VE, Sharma N, Watkins RJ, Read ML, Ryan GA, Kwan PP, Martin A, Watkinson JC, Boelaert K, Franklyn JA, McCabe CJ. Manipulation of PBF/PTTG1IP phosphorylation status; a potential new therapeutic strategy for improving radioiodine uptake in thyroid and other tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(7):2876–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Amit M, Na’ara S, Francis D, Matanis W, Zolotov S, Eisenhaber B, Eisenhaber F, Weiler Sagie M, Malkin L, Billan S, Charas T, Gil Z. Post-translational regulation of radioactive iodine therapy response in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(12):djx092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nicola JP, Masini-Repiso AM. Emerging therapeutics for radioiodide-refractory thyroid cancer. J Anal Oncol. 2016;5(2):75–86. [Google Scholar]