Abstract

Eukaryotic RNases H2 have dual functions in initiating the removal of ribonucleoside monophosphates (rNMPs) incorporated by DNA polymerases during DNA synthesis and in cleaving the RNA moiety of RNA/DNA hybrids formed during transcription and retrotransposition. The other major cellular RNase H, RNase H1, shares the hybrid processing activity, but not all substrates. After RNase H2 incision at the rNMPs in DNA the Ribonucleotide Excision Repair (RER) pathway completes the removal, restoring dsDNA. The development of the RNase H2-RED (Ribonucleotide Excision Defective) mutant enzyme, which can process RNA/DNA hybrids but is unable to cleave rNMPs embedded in DNA has unlinked the two activities and illuminated the roles of RNase H2 in cellular metabolism. Studies mostly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, have shown both activities of RNase H2 are necessary to maintain genome integrity and that RNase H1 and H2 have overlapping as well as distinct RNA/DNA hybrid substrates. In mouse RNase H2-RED confirmed that rNMPs in DNA during embryogenesis induce lethality in a p53-dependent DNA damage response. In mammalian cell cultures, RNase H2-RED helped identifying DNA lesions produced by Top1 cleavage at rNMPs and led to determine that RNase H2 participates in the retrotransposition of LINE-1 elements. In this review, we summarize the studies and conclusions reached by utilization of RNase H2-RED enzyme in different model systems.

RNase H2: a short perspective

RNase H2 has emerged from obscurity to relative fame becoming the subject of intense studies in the last 10+ years. Its prominence is due in large part to the discovery that mutations in any of the genes encoding the three proteins that makeup the heterotrimeric enzyme could cause Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome (AGS). AGS is a rare neuroinflammatory disorder (Crow et al., 2006) that shows pathological similarities to in utero viral infections. Later, it was demonstrated that some RNase H2 mutations are also associated with SLE (Gunther et al., 2015; Ramantani et al., 2010). This important biomedical association between RNase H2 and autoimmune disorders was followed by another breakthrough a few years later when the Kunkel lab found that RNase H2 was essential for the removal of ribonucleotides that are incorporated during DNA synthesis by all replicases (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010a), a previously underappreciated fact.

Although RNase H2 was the first ribonuclease described to act on the RNA moiety of RNA/DNA hybrids (Stein and Hausen, 1969), its study lagged that of RNase H1, the other major cellular RNase H, because of difficulties in purifying and identifying the enzyme’s components. RNase H2 in eukaryotes is an heterotrimer while RNase H1 is a monomer (Cerritelli and Crouch, 2009). In eukaryotes, both enzymes can process RNA/DNA hybrids, which occur during endogenous retroviral transposition but are mostly found in cells in the form of R-loops (see Glossary).

R-loops have dual roles in promoting and impeding cellular processes. They can induce transcription-replication conflicts by forming a block that prevents the advance of the replication machinery leading to chromosome breakage and recombination (Crossley et al., 2019; Lang and Merrikh, 2018). Despite these potential conflict-induced damages, R-loops are found in 8–9000 genes. These genes are typically highly transcribed with their promoter region having more Cytidines on the transcribed strand and more Guanidines on the non-transcribed strand, a feature called GC skew, (Ginno et al., 2013; Sanz et al., 2016). Immunoglobulin isotype switching is an important physiological example of a positive role of R-loop-induced chromosome breakage and recombination in which the first isotype formed (IgM) can be switched to produce any of several possible isotypes (Muramatsu et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2003). Detection of R-loops often uses the S9.6 antibody which exhibits a strong preference for RNA/DNA hybrids (Sanz and Chédin, 2019) or expression of an inactive RNase H1 protein in cells (Wang et al., 2019). However, to correlate a biological process with the presence of R-loops, ectopic expression of RNase H1 has become a standard procedure (Sollier et al., 2014). Aguilera’s lab was the first to employ this technique in eukaryotes to demonstrate that defects in proteins interacting with nascent RNA led to increased recombination frequencies which were partially reduced by overexpressing Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase H1 (Huertas and Aguilera, 2003), concluding that R-loops were promoting recombination. For mammalian cells, various versions of a plasmid overexpressing mouse or human RNase H1 fused to GFP have been used to reduce R-loop levels (Skourti-Stathaki et al., 2011). We recently used mice which express high levels of mouse RNase H1 in B cells to decrease R-loops involved in class switch recombination (CSR) (Maul et al., 2017). The fact that overexpression of RNase H1 has effects on endogenous R-loops suggests that there is insufficient RNase H1 to interact with all the R-loops in cells or that endogenous R-loops are partially inaccessible to RNases H1 and H2 (Skourti-Stathaki and Proudfoot, 2014).

Only RNase H2 has the unique ability of cleaving at single ribonucleoside monophosphates (rNMPs) embedded in DNA (Eder and Walder, 1991; Eder et al., 1993). Eder et al., were the first to suggest a potential role for RNase H2 in removing ribonucleotides incorporated during DNA synthesis. Others (Arudchandran et al., 2000; Rydberg and Game, 2002) later postulated that the rNMP-cleavage activity of RNase H2 may have an important repair function in bacteria, yeast and human cells, although until the Kunkel lab’s elegant studies (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010b), it wasn’t clear that rNMPs could be incorporated in DNA at any significant rate, considering the high selectivity of replicative DNA polymerases (Kunkel, 2009) (see Glossary). However, given that the cellular concentrations of ribonucleoside triphosphates (rNTPs) are much higher than that of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs)(Kennedy et al., 2010; Nick McElhinny et al., 2010b) and that the discrimination against rNTPs by the cellular replicases is not perfect (Cerritelli and Crouch, 2016; Williams et al., 2016) (see Glossary), it is now established that all DNA polymerases incorporate rNMPs at a considerable frequency. RNase H2 initiates the removal of single rNMPs in duplex DNA by the Ribonucleotide Excision Repair (RER) pathway (Sparks et al., 2012) (see Glossary), and its absence results in accumulation of rNMPs in DNA with detrimental consequences for the cells.

Deletion of RNase H2 has various outcomes depending on the organism. In budding yeast, any of the genes that code for the components of the RNase H2 complex can be deleted individually and in combination with deletion of the RNH1 gene, with only a minor increase in sensitivity to genotoxic stress, but not loss of viability (Arudchandran et al., 2000). Since S. cerevisiae can tolerate the lack of RNase H activity, it has been a very useful model to study RNase H2 (and RNase H1) defects. Crow et al., (Crow et al., 2006) remarked that no patient had complete loss of RNase H2, indicating that the enzyme is essential. Later it was confirmed that in mouse, deletion of any of the three genes [Rnaseh2b (Reijns et al., 2012); Rnaseh2c (Hiller et al., 2012); Rnaseh2a (Uehara et al., 2018)] that make up the RNase H2 complex is embryonic lethal due to a p53-dependent DNA damage response. Although essential during development, human RNASEH2A (Benitez-Guijarro et al., 2018), RNASEH2B (Bartsch et al., 2017) and mouse Rnaseh2a (Tsukiashi et al., 2018) genes can be inactivated in cell lines and recently these mutants have been used to examine effects of loss of both RER and Hybrid removal on various processes. Similarly, cell lines derived from patients and recombinant enzymes with hypomorphic mutations in RNASEH2A, 2B or 2C have also been studied (Aden et al., 2019; Chon et al., 2009; Coffin et al., 2011; Gunther et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2015).

Sorting out functions of eukaryotic RNases H2

In bacteria, the two types of RNases H have more restricted substrates. Enzymes that cleave at RNA/DNA junctions are only weak processors of RNA/DNA hybrids (Chon et al., 2013; Chon et al., 2009; Ohtani et al., 2004). Conversely, the bacterial enzymes that hydrolyze RNA are unable to incise with less than a stretch of four rNMPs in DNA (Cerritelli and Crouch, 2009). In eukaryotes, RNases H2 and RNases H1 are both capable of cleaving RNA/DNA hybrids but only RNases H2 incises at one, two or three rNMPs in DNA. Therefore, phenotypes related to accumulation of rNMPs in DNA can be associated with RNase H2 defects, while for RNA/DNA hybrids the situation is more complex since these are potential substrates for both RNases H1 and H2 and, possibly, helicases such as Pif1 (Geronimo and Zakian, 2016).

We set out to produce RNases H2 that can process either rNMPs in DNA or RNA/DNA hybrids, but not both substrates with the expectation that these separation of function enzymes could help sorting out the contribution of each activity.

Design and construction of the RED mutant

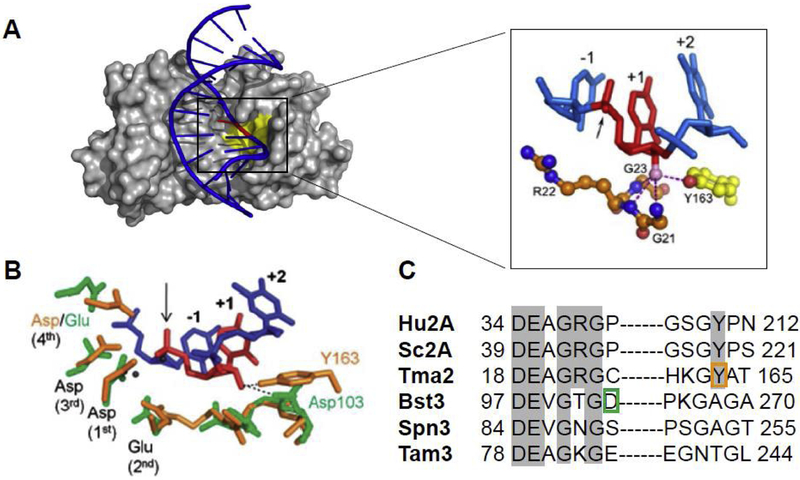

The RNase H Fold consists of a β-sheet comprising five β-strands whose conserved order is 3-2-1-4-5 flanked on either side by α-helices (Nowotny et al., 2005). The positions of the catalytic residues in the primary amino acid sequences differ between the two types of RNases H but the active centers are very similar (Chon et al., 2013). Apo-structures of RNases H are only modestly different from the enzymesubstrate complex indicating the nucleic acid needs to adjust to the contours of the protein. Some bacteria have a third type of RNase H, called RNase H3 (Tadokoro and Kanaya, 2009), whose overall structure resembles that of RNase H2, but its substrate specificity is like RNase H1 (Chon et al., 2006). RNase H3 requires a stretch of several rNMPs in DNA and, therefore is unable to incise at a single embedded rNMP. Together with the Nowotny lab, we determined the co-crystal structure of Thermotoga maritima RNase H2 (Tm-RNase H2) in complex with a duplex DNA containing a single rNMP (PDB:3O3G) (Rychlik et al., 2010). Dr. Chon had, as a graduate student in the Kanaya lab, solved the apo-structure of RNase H3 from Bacillus stearothermophilus (Bs-RNase H3) (Chon et al., 2006). The crystal structure of Bs-RNase H3 (PDB:2D0B) revealed similarities in the active site with Tm-RNase H2, but with some critical differences, which provided clues for developing an RNase H2 enzyme from S. cerevisiae that retained RNase H1-like activity but failed to incise at single rNMPs in DNA.

The Tm-RNase H2 co-crystal structure (PDB:3O3G) revealed a unique substrate-assisted catalysis that specifically recognized and utilized the RpD transition (Rychlik et al., 2010). Furthermore, there is a conserved tyrosine residue which plays a crucial role in the recognition and hydrolysis of the RpD structure. In addition to establishing hydrogen bond with the OH group of the ribose, the aromatic ring of the Tyr residue (Y163 in Fig. 1A and 1B) pushes the dNMP of the RpD sequence (position +2 in Fig. 1A and 1B) to position the phosphate group between the ribose and deoxyribose allowing it to directly participate in metal coordination and cleavage (arrow in between −1 and +1 in Fig. 1A and 1B). The bulky side chain of the Tyr residue would clash with the OH group of the RpR sequence and consequently catalysis would be disfavored, explaining the lack of RNA/DNA hybrid processing by this enzyme. The crystal structure of the eukaryotic RNase H2 revealed a slightly different position of the Tyr residue allowing it to be more permissive for RpR incision (Figiel et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Recognition of rNMP in dsDNA by RNase H2.

(A). Surface representation of Tm-RNase H2 with the catalytic center in yellow. The nucleic acid is shown in cartoon with DNA in blue and the single ribonucleotide in red. The close-up is a view of the interaction of the 2’-OH (pink sphere) with adjacent residues. The nucleotides are numbered relative to the scissile phosphate, which is indicate with an arrow. Cartoon adapted from Rychlik et al., 2010 (Rychlik et al., 2010). (B). Models of Bst-RNase H3 (in green) and Tm-RNase H2 (in orange) active sites interactions with substrates. Residues interacting with DpRpD and possible hydrogen bonds (dotted lines) are shown. The nucleotides are number as in A. Four catalytic residues (DEDD for Tm-RNase H2 and DEDE for Bst-RNase H3) are indicated in numerical order. Cartoon adapted from Chon et al., 2013 (Chon et al., 2013). (C). Sequence alignment of the active site and the region around the crucial Tyr residue is shown for human RNase H2A (Hu2A), S. cerevisiae Rnh201 (Sc2A), T. maritima RNase H2 (Tma2), B. stearothermophilus RNase H3 (Bst3), Streptococcus pneumoniae RNase H3 (Spn3) and Thermovibrio ammonificans HB-1 RNase h3 (Tam3). Amino acids important for catalysis are highlighted in grey. Residues interacting with the 2’-OH are boxed (Y in orange for Tma2 and D in green for Bst3).

To identify amino acids involved in RpD and RpR substrate interactions and catalysis, Chon et al., (Chon et al., 2013) superimposed the structure of Bs-RNase H3 on the structure of Tm-RNase H2 in complex with its single rNMP embedded in DNA substrate. They examined potential RpR contacts by replacing the duplex DNA with a single ribonucleotide of the Tm-RNase H2 co-crystal with the structure of the RNA/DNA hybrid co-crystalized with Hu-RNase H1 (PDB: 3PUF) (Nowotny et al., 2005). This modeling revealed that the position of the essential Tyr residue of Tm-RNase H2 was occupied by an Asp residue in Bs-RNase H3 (Fig. 1B). This Asp interacted with the OH groups of two consecutive ribose moieties. Additionally, a Glu residue in the active site formed hydrogen bonds with an adjacent OH group indicating that Bs-RNase H3 needs at least three consecutive ribose for catalysis, much like the RNase H1 enzyme (Nowotny et al., 2005). Subsequent studies (Figiel and Nowotny, 2014) confirmed the predicted alignment of the RNA/DNA substrate to the Bs-RNase H3 (Chon et al., 2013).

The key amino acids identified in the modeled structures of Tm-RNase H2 and Bs-RNase H3 by Chon et el., were modified in the catalytic subunit of S. cerevisiae RNase H2 (Sc-Rnh201). This model organism was chosen because RNase H2 is not required for viability and much was already known about properties of the budding yeast in the absence of RNases H (Arudchandran et al., 2000). In the sequence alignment (Fig. 1C), the position of the essential Tyr in Tm-RNase H2 (Tma2 in Fig. 1C) and Sc-Rnh201 (Sc2A in Fig. 1C) is occupied by an Ala residue in Bs-RNase H3 (Bst3 in Fig. 1C), but when the corresponding mutation Y219A was introduced in Sc-Rnh201, the enzyme became inactive losing both RpD and RpR activities. In the sequence alignment, the position of the critical Asp in Bs-RNase H3 is occupied by a Pro in Sc-Rnh201 and when the mutation P45D was introduced in Sc-Rnh201 in combination with Y219A the resulting mutant Sc-Rnh201-P45D-Y219A recovered about 40 % of the wild-type activity for RpR substrates, while still being inactive for RpD substrates. In this way, a separation of functions mutant was obtained that retains RNA/DNA hybrid activity but is unable to process rNMPs in DNA. This mutant was later called RNase H2-RED for Ribonucleotide Excision Defective, but in the literature has also been referred to as RNase H2-P45D-Y219A, Separation of Function (SoF) mutant, and as RNH201-hr for hybrid removal.

RNase H2-RED activity in vitro

Chon et al., reported that the in vitro activity of Sc-RNase H2-RED was less than 0.1 % of that of wild-type (WT) enzyme for single rNMPs embedded in a DNA oligonucleotide substrate (Chon et al., 2013 and Table 1), and that the activity increased with the length of the ribonucleotide patch. A contiguous stretch of six ribonucleotides attached to DNA and opposite to DNA, mimicking an Okazaki Fragment (OF) junction, was cleaved by the RED mutant with 3.1% efficiency as the WT Sc-RNase H2. A 12 mer-RNA opposite to a 12-mer DNA that resembled a short RNA/DNA hybrid was cleaved by Sc-RNase H2-RED 25% as well as by WT Sc-RNase H2. A long synthetic RNA/DNA hybrid was processed 40% as efficiently with respect to the WT enzyme. These in vitro data suggest that Sc-RNase H2-RED has hybrid processing activity although not as good as that of the wild-type counterpart and has essentially no RER incision activity.

Table 1.

Relatives activities of RNase H2 derivatives

| 1R | 6R | 12R | Poly-rA/poly-dT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-RNase H2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Sc-RNase H2-RED | <0.1 | 3.1a (<0.1)b | 25 | 40 |

| Mo-RNase H2-RED | 0.3 | ND | 26 | 130 |

| Sc-RNase H2-G42S | 2.2 | 5.1 | 4 | 8 |

| Mo-RNase H2-G37S | 17 | ND | 3.5 | 1.6 |

Efficiency for the cleavage at RpR

Efficiency for the cleavage at RpD

Sc (S. cerevisiae) and Mo (Mouse)

ND: not determined

Properties of Sc-RNase H2-RED mutant in vivo

To validate the in vitro data and to confirm that Sc-RNase H2-RED cannot process single rNMPs in vivo, Chon et al., (Chon et al., 2013) used a strain with a replicative polymerase mutant (pol2-M644G) that has a higher propensity than the WT counterpart to incorporate rNMPs in DNA (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010a) (see Glossary). In combination with deletion of RNH201, this strain has an elevated mutation rate associated with an increase in 2–5 bp deletions in short tandem repeats (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010a), which are produced by the processing of the ribonucleotides by Topoisomerase 1 (Top1) (Kim et al., 2011) (see Glossary). Strain pol2-M644G rnh201Δ transformed with a single copy plasmid expressing Sc-Rnh201-RED (called Rnh201-P45D-Y219A) driven by its own promoter had the same mutation rate and spectra as the parental strain deleted for RNH201. In contrast, the same vector expressing Rnh201-WT, fully rescued the phenotype. This demonstrated that Sc-RNase H2-RED is unable in vivo to process single rNMPs embedded in DNA.

To show that RNase H2-RED can process R-loops similarly to the WT enzyme, Chon et al., (Chon et al., 2013), chose a genetic background that depends on the removal of R-loops for viability. R-loop accumulation becomes particularly deleterious in highly transcribed genes, such as the ribosomal RNA (rDNA) genes. S. cerevisiae rnh1Δ rnh201Δ strains are viable but require Top1 to prevent transcription blocks of rDNA genes (El Hage et al., 2010) (see Glossary). PGAL-TOP1 rnh1Δ rnh201Δ strain is lethal in media containing glucose because the TOP1 gene under the control of the PGAL promoter is not transcribed. Chon et al., expressed the Sc-Rnh201-RED gene in the PGAL-TOP1 rnh1Δ rnh201Δ strain in glucose media and found that the RED mutant completely rescued the lethality of the parental strain, displaying full activity against in vivo R-loops (Chon et al., 2013).

R-loops can become barriers to the advancement of a replication fork thereby inducing fork stalling and collapse. Head-on collisions between progressing replisomes and co-transcriptional R-loops are especially harmful (García-Muse and Aguilera, 2016; Hamperl and Cimprich, 2016). The repair of R-loopmediated DNA damage and replication fork collapse requires the action of the Homologous Recombination (HR) system (Ait Saada et al., 2018). In S. cerevisiae, Sgs1 is an essential component of the HR repair processing of dsDNA breaks and replication fork re-establishment (Bernstein et al., 2009; Hegnauer et al., 2012) and consequently, the combined deletion of the SGS1 gene and any of the genes encoding RNase H2 subunits shows a synthetic sickness phenotype (Ooi et al., 2003). Sc-Rnh201-RED mutant was able to restore normal growth in the sgs1Δ rnh201-RED strain, confirming that in the absence of Sgs1 and RNase H2, R-loops induce DNA damage (Chon et al., 2013). Other studies (Allen-Soltero et al., 2014) found that deletion of TOP1 does not improve rnh203Δ sgs1Δ phenotypes, such as slow growth rates, gross chromosome rearrangements (GCR) and aberrant morphologies, indicative that the defects were not caused by Top1 processing of rNMPs in DNA. Thus, lack of resolution of RNA/DNA hybrids is the source of the synthetic sickness observed by loss of Sgs1 and RNase H2 activities. Collectively, these studies established that RNase H2-RED mutant behaves in vivo as in vitro, processing RNA/DNA hybrids but no single rNMPs embedded in DNA. They also indicated that RNase H1 share the ability to process R-loops formed during rDNA transcription but only RNase H2 is critical for removing R-loops related to Sgs1.

Use of RNase H2-RED in S. cerevisiae to parse defects in vivo

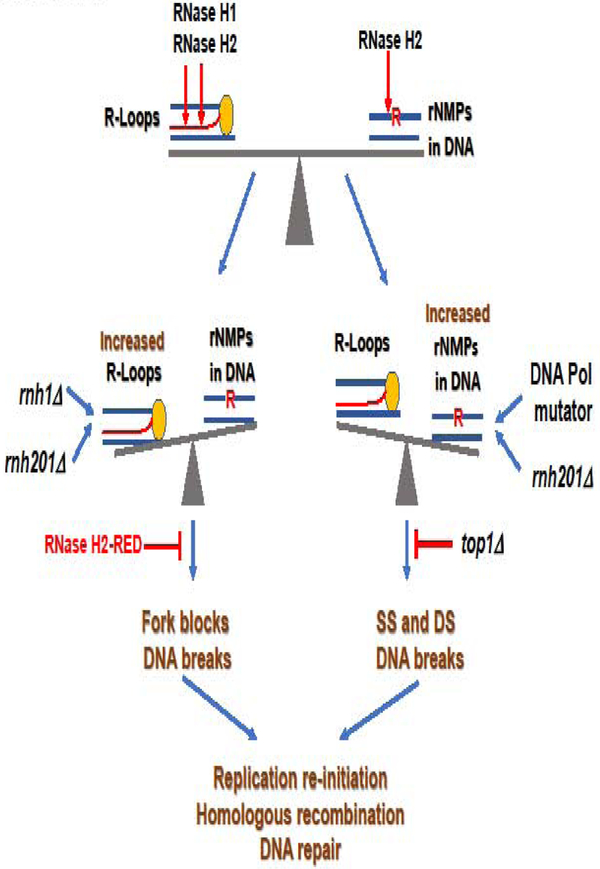

The absence of RNase H1 and RNase H2, individually and together, leads to different degrees of genomic instability in S. cerevisiae (Allen-Soltero et al., 2014; Potenski and Klein, 2014; Wahba et al., 2011). Although the phenotypes observe with individual mutations are small, the real defects may be masked by the compensatory effect of alternative pathways for resolution of R-loop or rNMP-induced DNA damage. Deletion of RNH203 combined with mutations in genes involved in DNA recombination and repair have synergistic effects on growth rate and GCR, suggesting that cells defective for RNase H2 suffer from DNA damage (Allen-Soltero et al., 2014). Yeast strains lacking both RNase H1 and RNase H2 have increased recombination rates and mutagenesis, but whether R-loops or single rNMPs embedded in genomic DNA are responsible for these phenotypes may be a matter of which substrate is more abundant and damaging in each genetic background. Accumulation of either R-loops or rNMPs in DNA have ultimately the same effects of inducing single-strand breaks (SSB) and double-strand breaks (DSB) in DNA, promoting recombination, stalling DNA replication and increasing DNA damage. The use of the RNase H2-RED mutant has helped in assigning specific defects to each substrate (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. R-Loops and rNMPs are kept in check by RNase H1 and RNase H2.

The coordinate work of RNase H1 and RNase H2 limits the presence of R-loops (top left, DNA in blue, RNA in red. The RNA is extruding from the RNA polymerase represented as a yellow oval) and rNMPs in DNA (top right, DNA in blue, single rNMP represented by a red “R”) to preserve genome stability (top). In the absence of RNase H1 and RNase H2, R-loops accumulate and block replication creating breaks and DNA damage, outweighing the defect that might cause rNMPs in DNA in the absence of RNase H2. The RNase H2-RED mutant would process these hybrids preserving genome integrity (middle left). When RNase H2 is missing in combination with replicases mutants that include rNMPs at higher frequency than the WT counterparts, especially leading strand Pol ε-M644G, the high density of unrepaired rNMPs in DNA would result in SSB and DSB in DNA upon Top1 processing, while R-loops would not accumulate significantly because RNase H1 is active. Deletion of TOP1 would prevent DNA damage (middle right). DNA damage created by increased R-loops or increased rNMPs in DNA induces replication re-initiation, HR and DNA repair to maintain genome integrity (bottom).

RNase H role in recombination

Several publications appeared to be in conflict about which RNase H substrate has a role in inducing DNA recombination (Conover et al., 2015; O’Connell et al., 2015) and using RNase H2-RED was instrumental in resolving the issue. It turned out that both RNase H2’s activities are important for preventing HR but, depending of the strain background and substrate abundance, one will take precedence over the other.

O’Connell et al., (O’Connell et al., 2015) studied mitotic recombination by detecting loss of heterozygosity (LOH; see Glossary), which is a useful tool to assess genome instability in S. cerevisiae and concluded that R-loops and not rNMPs were inducing recombination. They found that single deletion of the RNH1 gene had no effect on LOH. In contrast, the rnh201Δ strain showed an increase in recombination that was further elevated in double mutant rnh1Δ rnh201Δ. In a strain that carried the more restrictive pol2-M644L mutation, which codes for a Pol ε that incorporates fewer rNMPs in DNA than the WT Pol ε (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010a) (see Glossary) they observed a very small decrease in the LOH of the double mutant pol2-M644L rnh201Δ with respect to the single rnh201Δ mutation suggesting that rNMPs do not significantly contribute to recombination in these backgrounds. No rnh201-RED study was included in the O’Connell et al., manuscript.

In the same Genetics issue as the O’Connell paper, Conover et al., (Conover et al., 2015) measuring LOH in different yeast backgrounds concluded that rNMPs in DNA increased both HR and nonallelic homologous recombination. Diploid strains bearing mutants rnh201Δ top1Δ or pol2-M644G rnh201Δ top1Δ expressing the more rNMPs permissive Pol ε mutant (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010a) (see Glossary) showed reduced recombination rates compared to the TOP1 counterparts, suggesting that the processing of rNMPs by Top1 in the absence of RNase H2 was causing genomic instability (see Glossary). They described a direct correlation between the density of ribonucleotides embedded in DNA and the rate of Top1-dependent LOH for leading strand synthesis. However, double mutants pol1-L868M rnh201Δ and pol3-L612M rnh201Δ, which harbor lagging strand Pol mutants more permissive for rNMPs (Williams et al., 2015), had no more elevation of recombination rates than single mutant rnh201Δ (Conover et al., 2015), presumably because lagging strand Pol mutants incorporate rNMPs at a lower rate than the leading strand counterpart. No rnh201-RED mutation was used in this study.

To analyze these discrepancies, Cornelio et al., (Cornelio et al., 2017) used a yeast strain carrying the rnh201-RED mutation and found that the rate of LOH was between those for RNH201 and rnh201Δ, and that deletion of TOP1 further decreased the LOH of the rnh201-RED mutant, indicating a role for both R-loops and rNMPs in recombination. A double mutant strain rnh1Δ rnh201Δ showed a much higher LOH than single mutant rnh201Δ. In contrast rnh1Δ rnh201-RED had similar LOH to RNH1 rnh201-RED strain, suggesting that RNase H2-RED can act on R-loops processed by RNase H1 and or RNase H2. The recombination rate of the pol2-M644G rnh201-RED mutant strain was similarly high to that of the pol2-M644G rnh201Δ, signifying that in the situation of increase density of rNMPs in DNA, Top1-mediated processing of ribonucleotides becomes the main threat to genomic instability. However, when they used the Pol ε-M644L mutant that incorporates about 1/3 of the rNMPs of the WT counterpart, the LOH of the pol2-M644L rnh201-RED was similar to that of the pol2-M644L mutant. These elegant experiments, using the RNase H2-RED mutant, were able to confirm that both activities of RNase H2 prevent genome instability.

Using a different assay that also detects LOH, Zimmer and Koshland (Zimmer and Koshland, 2016) found a 14.9-fold increase in LOH of the rnh1Δ/Δ rnh201Δ/Δ double mutant diploid strain with respect to WT. Adding a single copy of the Rnh201-RED gene (rnh1Δ/Δ rnh201Δ/rnh201-RED) reduced the LOH to just a three-fold difference from WT LOH, leading to the conclusion that hybrids are the major cause of LOH in this strain (RNH201-RED was called RNH201-hr for “hybrid removal” in their publication). However, they noted that the RNase H2-RED mutant does not completely suppress LOH, suggesting a minor role for rNMPs embedded in DNA on the increased recombination observed in this genetic background. These data fit well with the idea that in cells defective for both RNases H, the accumulation of R-loops would outweigh the damage created by rNMPs (Fig. 2). Furthermore, they analyzed the distribution of LOH junctions in the chromosomal region where the reporter gene was located, and in strain rnh1Δ/Δ rnh201Δ/rnh201-RED they found the same hotspot as in the double mutant rnh1Δ/Δ rnh201Δ/Δ, leading to the conclusion that the hotspot corresponded to a region with R-loops processed by RNase H1. They confirmed this by examining the rnh1Δ/Δ RNH201/Δ mutant. The RNase H2-RED mutant helped identifying specific RNA/DNA hybrids that are targeted by RNase H1, but not RNase H2, which seems to have a more global general effect in reducing the prevalence of R-loops across the genome (Zimmer and Koshland, 2016). This is another example of each RNase H having unique hybrid targets, as in the case of sgs1Δ rnh201Δ where RNase H2-RED but not RNase H1 was able to correct the R-loopmediated DNA damage (Chon et al., 2013).

Does RNase H2 process Okazaki Fragments?

Epshtein et al., (Epshtein et al., 2016) determined recombination in haploid cells by examining intrachromosomal gene conversion in RNases H mutants (see Glossary Loss of Heterozygosity). They found that recombination rates were increased upon deletion of RNH201 (or RNH202) but not RNH1. Furthermore, the absence of RNase H1 in the rnh201Δ strain had no effect on gene conversion. However, deleting together TOP1 and RNH201 decreased the recombination rate, although not to the WT level, suggesting that the process is mediated at least in part by Top1 incisions at rNMPs in DNA. The embedded rNMPs were not incorporated by the leading strand replicase Pol ε, because increasing (pol2-M644G) or decreasing (pol2-M644L) the density of rNMPs in DNA had no effect on recombination rates. In addition, the rnh201-RED mutant showed lower recombination rate than the rnh201Δ strain. They proposed that recombination is initiated by DNA breaks that originate from replication stalling caused from stretches of ribonucleotides in lagging-strand DNA, perhaps the remains of OF processing, or from replication-transcription collisions induced by R-loops, which can be processed by RNase H2 (and RNase H2-RED), but not RNase H1. It would be interesting to determine whether lagging-strand Pol mutants with higher propensity to incorporate rNMPs in DNA have any effect in recombination rates in this strain. They suggested that the inability of RNase H2-RED mutant to totally reverse the recombination rate to WT levels might be due to reduced activity of the mutant RNase H2 against short hybrids. However, it also might be that the observed genomic instability could be caused by the compound effect of R-loops, single and multiple rNMPs in DNA.

Reijns et al., (Reijns et al., 2015) using a yeast strain that is deleted for RNH201 and that has a Pol α mutant that incorporates rNMPs at higher frequencies than WT Pol α (Williams et al., 2015) estimated that Pol contribute about 1.5% to the DNA of the mature genome in budding yeast. They also concluded that most of the mutations found in the yeast genome localized to OF junctions because of the poor fidelity of Pol α Previously it was thought that most, if not all, of the DNA synthesized by Pol α was removed by strand displacement synthesis (Stodola and Burgers, 2017). Reijns et al., (Reijns et al., 2015) concluded that RNase H2 is not involved in OF processing because a strain containing the RNase H2-RED mutant (called separation of function mutant), which could cleave at stretches of rNMPs in DNA such as the ones present at the OF junctions, had the same ribonucleotide content as the RNH201 deletion counterpart.

Top1 mediates the DNA damage of rNMPs in genomic DNA

Williams et al., (Williams et al., 2017) expressed the RNase H2-RED mutant in a pol2-M644G strain and found that as shown herein, in this genetic background of high rNMPs density, the most prominent defects are caused by mutagenic Top1-processing of ribonucleotides in DNA (Fig. 2). The phenotypes observed in pol2-M644G rnh201-RED and pol2-M644G rnh201Δ strains were very similar and included slow growth, S-phase check point activation and cell accumulation in S and G2 phase, as well as an increase in mutation rates associated with 2–5 bp deletions signature of Top1-processing of rNMPs embedded in DNA. Deletion of TOP1 in these backgrounds reversed all the deleterious effects.

Huang et al., (Huang et al., 2017) found that Rad52 and HR are essential to resolve the DSB formed by Top1-processing of rNMPs in DNA. Strains rnh201Δ and rnh201-RED both have increased Rad52 foci that could be reduced by inactivation of TOP1. Leading strand rNMP-permissive Pol ε induced lethality in combination with deletion of RAD52 and RER defects equally in strains pol2-M644G rad52Δ rnh201Δ and pol2-M644G rad52Δ rnh201-RED. Deletion of RAD51, also important for HR, but not as essential as RAD52 (Huang et al., 2017; Lazzaro et al., 2012), had detrimental effect in combination with pol2-M644G rnh201Δ or pol2-M644G rnh201-RED, inducing slow growth, S-phase check point activation and replicative stress, all of which could be diminished by inactivation of Top1. These data suggested that Top1-induced DSB occurred at rNMPs and become lethal in the absence of HR. The use of the RNase H2-RED mutant ruled out any involvement of R-loops in these processes.

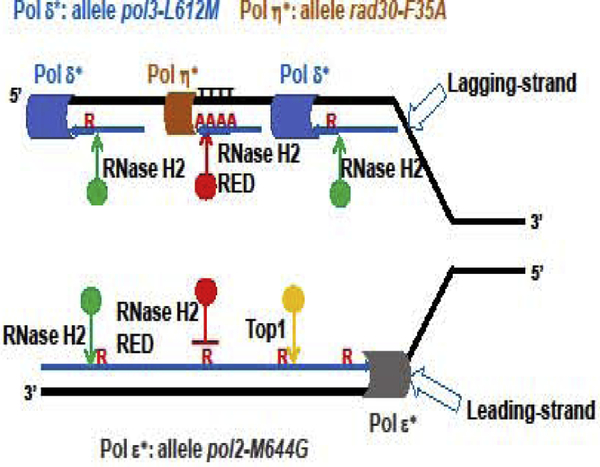

RNase H2 processing of rNMPs incorporated by translesion polymerases

In S. cerevisiae, Pol η is a specialized translesion polymerase (see Glossary) that prevents replication stress and genome instability. Pol η can bypass thymidine dimers (Gibbs et al., 2005) induced by UV radiation (Yang, 2011), and also participates in the replication of hard to copy DNA regions including common fragile sites, regions of mononucleotide repeats and low complexity A-T rich sequences (Fungtammasan et al., 2012), preventing replication stress and genome instability (Bergoglio et al., 2013). Donigan et al., (Donigan et al., 2015) found that the high frequency of incorporation of rNMPs by Pol η-F35A steric gate mutant increased the sensitive to UV radiation equaling the rate found when eliminating Pol η (rad30Δ) Deletion of the RNH201 gene had no effect on the UV-survival of the rad30Δ strain but improved the growth after UV treatment of the rad30-F35A mutant. The rad30-F35A rnh201-RED (called rnh201-P45D-Y219A) mutant exhibited UV sensitivities intermediate between those of rad30-F35A and rad30-F35A rnh201Δ strains. This suggested that the Pol η-F35A mutant incorporates single rNMPs and multiple runs of polyribonucleotide tracts in DNA at a high rate, which RNase H2 would cleave to initiate the RER process. An excess of nicks might overwhelm subsequent steps of the RER process, leaving some breaks unprocessed and inducing DNA damage and loss of viability. Although the rad30-F35A rnh201Δ strain had better UV survival than the rad30-F35A RNH201 strain, the large accumulation of ribonucleotides in DNA in the absence of RNase H2 increased mutagenesis. However, instead of the signature 2–5 bp deletions associated to Top1-proccesing rNMPs in leading strand DNA, rad30-F35A rnh201Δ strain had a very elevated rate of one base pair deletion at runs of template Ts. Remarkably, this striking new mutation pattern was abolished in the rad30-F35A rnh201-RED mutant strain, which showed the usual pattern of Top-induced 2–5 bp deletions in short tandem repeats (Sparks and Burgers, 2015). The use of the RNase H2-RED mutant in this background identified a new mutation pattern associated with a track of rNMPs in lagging strand DNA (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Removal of rNMPs inserted by DNA polymerases.

Representation of the replication fork, with template strand in black and newly synthesized strands in blue. The leading strand Pol ε (represented as a grey cylinder) processively copies the template strand. Allele pol2-M644G codes for a mutant enzyme that incorporates rNMPs at higher frequency than the WT Pol ε. These newly embedded rNMPs in DNA are nicked by WT RNase H2 (green circle), but not by the mutant RNase H2-RED (red circle), to initiate the RER process. In the absence of RNase H2, Top1 (yellow circle) can incise at the 3’-end of the rNMP inducing DNA breaks and mutagenesis. The bulk of lagging strand synthesis is carried out by Pol δ (blue cylinder) in OFs that need processing and maturation. Allele pol3-L612M codes for a mutant with higher propensity than WT Pol δ to incorporate rNMPs in DNA. RNase H2, but not RNase H2-RED, can initiate the removal of single rNMPs embedded in lagging strand DNA. In regions difficult to replicate, such as homo-polymeric tracks, especially runs of Ts in lagging-strand DNA template, the translesion polymerase Pol η (orange cylinder) replaces Pol δ and copies DNA with lower fidelity. The allele rad30-F35A codes for a Pol η mutant protein that incorporates rNMPs in DNA at a higher frequency than the WT Pol η. RNase H2-RED would incise in tracks of polyribonucleotide in DNA incorporated by the mutant Pol η to initiate their removal.

The recent work of Kreisel et al., (Kreisel et al., 2018) confirmed these findings. Using the HydEn-seq technique (Clausen et al., 2015) to identify rNMPs in genomic DNA incorporated by Pol η-F35A mutant in the absence of RNase H2, they determined that Pol η had the same strand-specificity as pol α and pol δ, the two replicases that synthesized lagging-strand DNA. Strikingly, the lagging strand specificity was not detected when the DNA was from the strain rad30-F35A rnh201-RED (called rnh201- P45D-Y219A), suggesting that the majority of rNMPs incorporated by Pol η-F35A were polyribonucleotide tracts that were removed by RNase H2-RED. They also confirmed that the 1 bp deletion signature of the rad30-F35A rnh201Δ strain is due to Pol η-F35A copying runs of Ts during lagging strand synthesis (Fig. 3).

Meroni et al., (Meroni et al., 2019) reported that under replicative stress induced by Hydroxyurea (HU; see Glossary), Pol η is recruited to stalled replication forks to restore DNA synthesis, although at the expense of low fidelity replication and higher rNMP incorporation in DNA. In cells lacking RNases H, Pol η activity, under low dNTPs levels induced by HU, becomes highly toxic to cells. The high sensitivity of rnh1Δ rnh201Δ strain to HU was reversed by deleting RAD30 or expressing Rnh201-RED and aggravated by the rad30-F35A mutant, which incorporates rNMPs at higher rate than WT Pol η (Donigan et al., 2015). The rnh1Δ rnh201–RED mutant grew as well as the WT strain in HU, suggesting that the Pol η-dependent lethality induced by HU in absence of RNases H is generated by polyribonucleotide tracts incorporated by Pol η during DNA replication or left out by defective processing of OF, provided that Pol η participates in lagging strand synthesis (Kreisel et al., 2018). It is also possible that R-loops stabilized in the absence of RNase H1 and RNase H2 could contribute to replicative stress and lethality of the rnh1Δ rnh201Δ strain in presence of HU. The RNase H2-RED can process all these substrates and restore growth.

Mammalian RNase H2-RED mutant

The mouse RNase H2 enzyme with the corresponding RED mutations, (RNase H2A-P40D-Y211A) showed in vitro activities similar to those of yeast counterpart against the same substrates (Uehara et al., 2018 and Table 1). Mouse RNase H2-RED had 0.3% of the WT activity for the cleavage of single rNMP embedded in a dsDNA oligonucleotide, 26% of the WT activity against a 12-mer RNA/DNA hybrid and notably 130% of the WT activity for the cleavage of a long synthetic hybrid. Chon et al., and Uehara et al., (Chon et al., 2013; Uehara et al., 2018) obtained the in vitro activity data using 32P-radiolabeled substrates, either internally (for the long synthetic hybrid) or at the 5’-end. However, Benitez-Guijarro et al., using a fluorometric assay found that Human RNase H2-RED (called SoF) had different cleavage pattern and much lower hybrid processing activity than WT (Benitez-Guijarro et al., 2018). Uehara et al., tried to resolve this issue by using an 18-mer RNA/DNA hybrid labeled at the 5’-end of the RNA strand with 32P and at the 3’-end with a fluorescent label (Figure S1 of Uehara et al., 2018). They found that the RNase H2-RED mutant exhibited different cleavage site preference than the WT enzyme, and that, due to the nature of detection, with 32P labeled substrates the hydrolysis products of intermediate sizes were observed, while fluorescent-labeled released products could be detected only if close to the 3’-end. Overall, they concluded that the activity of the RNase H2-RED mutant toward an 18-mer 32P-labeled RNA/DNA hybrid was 20% of that of the WT enzyme, in line with the activity observed for the yeast enzyme for short hybrids, while with the same substrate using the fluorometric assay only about 4% of the WT activity was obtained.

Mouse with RNase H2-RED mutation is embryonic lethal

The question of which of RNase H2’s activities is required for viability during mouse development was addressed by Uehara et al., (Uehara et al., 2018) by introducing the RNase H2-RED mutation (called Rnaseh2aRED) in the mouse genome. They found that homozygous Rnaseh2aRED/RED mice arrested embryonic development at the same stage as Rnaseh2a-KO, Rnaseh2b-null and Rnaseh2c-KO mice [Table 2; (Hiller et al., 2012; Reijns et al., 2012; Uehara et al., 2018)] due to the activation of the p53-mediated DNA damage response pathway. These findings support the conclusion that high levels of rNMPs in DNA induce lethality in both the RNase H2-null and RNase H2-RED mutants. Deletion of p53 extended the development of the Rnaseh2aRED/RED and null embryos, suggesting that in mouse, as in yeast, processing of rNMPs by Top1 might create SSB and DSB leading to irreversible DNA damage, at least during embryonic development when DNA synthesis occurs very rapidly (Kojima et al., 2014). By crossing the Rnaseh2aRED with a RNase H2 AGS-related mutant (Rnaseh2aG37S) that as a homozygote develops to birth (Pokatayev et al., 2016), Uehara et al., were able to estimate a threshold of rNMP tolerance in genomic DNA, above which p53 induces apoptotic cell death (Uehara et al., 2018). They also found that the Rnaseh2aRED mutant is dominant over the Rnaseh2aG37S counterpart because heterozygous mutant Rnaseh2aRED/G37S was early embryonic lethal while Rnaseh2aG37S/G37S and even Rnaseh2aG37S/− survived to birth (Table 2). RNase H2-G37S has residual rNMP cleavage activity that might be sufficient to maintain the number of ribonucleotides below the threshold of irreversible DNA damage (Table 1 and 2). Both mutant enzymes, RNase H2-RED and RNase H2-G37S, showed in vitro much lower binding affinity for their substrate than the WT enzyme. Uehara et al., suggested that RNase H2-RED and RNase H2-G37S compete for interaction with PCNA through the PCNA-interacting peptide (PIP) on the RNase H2B subunit (Chon et al., 2009). Binding of RNase H2-RED to PCNA might prevent the productive processing of rNMPs by the RNase H2-G37S enzyme. In these studies, the RNase H2-RED mutant was instrumental for clearly establishing that mouse embryonic lethality in the absence of RNase H2 is caused by accumulation of rNMPs in DNA. They also showed that competition between mutant enzymes might affect the symptoms of AGS patients having compound heterozygous mutations, which may not be revealed from examination of the recombinantly in vitro-expressed enzymes. Finally, the RNase H2-RED mutant uncovered the existence of a threshold of ribonucleotide accumulation in DNA above which a p53-dependent embryonic death occurs (Uehara et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Activities in embryo lysates (%) and viability

| 1R | Poly-rA/poly-dT | Viability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rnaseh2a+/+ | 100 | 100 | 100 % |

| Rnaseh2a+/RED | 43 | 102 | 100 % |

| Rnaseh2aRED/RED | <1 | 74 | Embryonic lethal |

| Rnaseh2aRED/G37S | 6.5 | 129 | Embryonic lethal |

| Rnaseh2aG37S/− | 6.4 | 32 | Perinatal lethal |

Ribonucleotides embedded in DNA are processed by Top1 in absence of RNase H2 also in mammals

Mammalian cell lines tolerate depletion of RNase H2 and, like yeast cells, have been instrumental to study the effect of selectively eliminating the rNMP processing activity using the RNase H2-RED mutant. RNase H2-RED helped in determining that rNMPs, not RNA/DNA hybrids, were the cause of the cytotoxicity of inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) in the absence of RNase H2 (Zimmermann et al., 2018). PARP1 inhibitors (PARPi) can trap PARP1 bound to DNA lesions (Lord and Ashworth, 2017; Pommier et al., 2016) and are commonly used in the therapy of BRCA1 and BRAC2 cancers that are defective in HR (Lord and Ashworth, 2017). Zimmermann et al., extended the list of PARP-interacting DNA lesions to include the defective processing of rNMPs in DNA in the absence of RNase H2. They described a CRISPR (clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats) screen to find genes that exhibit synthetic lethality with PARPi and identified loss of any of the three genes coding for the RNase H2 complex, along with genes involved in HR and DNA damage response and repair. They confirmed that RNase H2-null cells are hypersensitive to PARPis, such as olaparib and talazoparib, which increase the level of apoptosis in these cells. RNase H2-RED (called separation of function mutant) did not rescue the sensitivity to PARPi of RNASEH2AKO, indicating that the RER activity of RNase H2 protects cells against PARPi-induced cellular damage. The cytotoxicity was suggested to be mediated by Top1 because depletion of TOP1 in RNase H2 null cells decreased apoptosis induced by PARPi. They concluded that, like yeast cells (Huang et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2013), mammalian cells have an alternate mechanism of processing rNMPs in the absence of RER. Top1-initiated cleavage results in nicks in DNA and other lesions that required PARP. PARPi would trap these intermediates inducing replication arrest and cell damage. They extended their studies to determine that in a number of cancers, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Kipps et al., 2017) and prostate cancer (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network 2015) (Abeshouse et al., 2015) the deletion of tumor suppressor loci includes the collateral removal of RNASH2B, and they found that in these cases the cancer cells were very sensitive to PARPi, suggesting that PARPi should be used as therapy in all cancer defective for RER. In these studies, RNase H2-RED was important to uncover a possible therapeutic intervention in cancer cells lacking RNase H2.

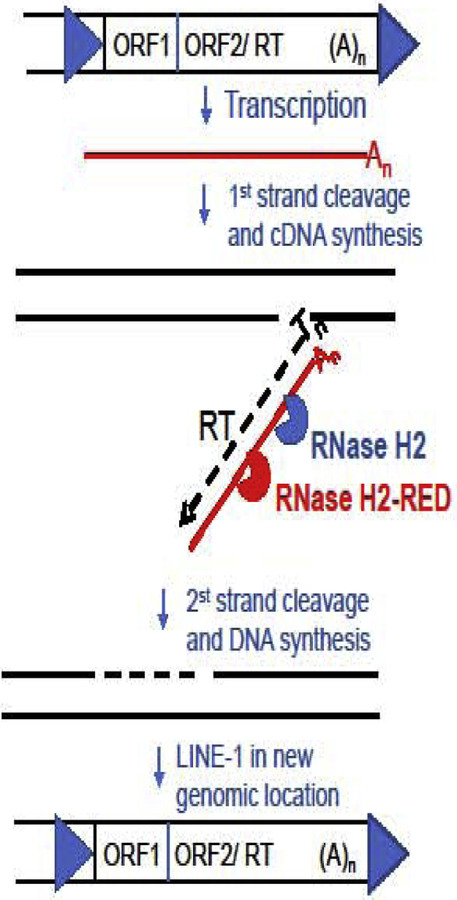

LINE-1 are processed by RNase H2

Retrotransposition of a LINE-1 element (see Glossary) has been proposed to be restricted by the functions of genes whose mutations cause AGS, such as TREX1, SAMHD1 and ADAR1 (Orecchini et al., 2016; Stetson et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2013), suggesting defects in any of these genes could lead to the accumulation of retrotansposition-induced mutations or production of nucleic acids that stimulate DNA- or RNA-sensing innate immune responses. Choi et al., (Choi et al., 2018) also reported that RNase H2 is involved in the restriction of LINE-1 retrotransposition, although Bartsch et al., (Bartsch et al., 2017) had previously found that RNase H2 was required for LINE-1 mobilization. Benitez-Guijarro et al., (Benitez-Guijarro et al., 2018) using the RNase H2-RED mutant provided very strong evidence that the RNA/DNA hydrolytic activity of RNase H2 is required for LINE-1 transposition. Retrotransposition was suppressed by depletion of RNASEH2A in HeLa and U2OS cell lines, but overexpression of the RNase H2-RED mutant (called SoF for separation of function) increased retrotransposition in RNASEH2-KO cell lines. Moreover, RNase H1 overexpression could partially complement the retrotransposition defects of RNase H2 null cell lines, a further confirmation that hybrid processing activity is required for retrotransposition (Benitez-Guijarro et al., 2018). In this work the RNase H2-RED mutant enzyme was instrumental in identifying the hybrid activity of RNase H2 as necessary for LINE-1 retrotransposition and to point out the RNA/DNA hybrids intermediates of retrotransposition as a possible source of immunostimulatory nucleic acid causing AGS when RNase H2 is defective (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. RNase H2 participates in the LINE-1 retrotransposition.

Retrotransposition competent LINE-1 elements consist of a promoter in their 5’-untranslated region (blue arrow in the top left) followed by ORF1, which codes for an RNA-binding protein and ORF2/RT which codes for a protein with both endonuclease and reverse transcriptase activity (Goodier, 2016). At the 3’-end of the element is a short 3’-UTR followed by a poly-A tail and a short repeat created during the insertion (blue arrow at the top right). The process of retrotransposition starts by transcription of the LINE-1 element into a mRNA (red line) including a poly-A tail (An). Then, LINE-1 mRNA is reverse transcribed, and the new cDNA is integrated in a new genomic location by the concerted work of ORF2/RT. The endonuclease recognizes and cleaves the bottom strand of a target sequence containing a run of Ts, which are used as primer for the RT to copy the LINE-1 mRNA and make a cDNA (black dotted line in middle panel), resulting in an RNA/DNA hybrid covalently attached to the genome. The following step requires the removal of the mRNA template and because LINE-1 does not code for an RNase H, it uses the cellular RNase H2 (blue). The RNase H2-RED mutant (red) can also participate in this hydrolysis. Subsequently, in a process not completely understood, after removal of the RNA, the top strand is cleaved and the newly cDNA is used as template for top strand synthesis, resulting in a new LINE-1 insertion.

Concluding Remarks

This review addresses the significant contributions that the RNase H2-RED mutant has made to illuminate the role of the two functions of RNase H2 in cellular metabolism of eukaryotic cells. In addition to elucidate that both RNase H2 activities are important in preserving genome integrity, RNase H2-RED also helped in other findings unrelated to rNMPs and RNA/DNA hybrids processing. In yeast, RNase H2-RED finally settled that RNase H2 is not involved in OF processing and that Pol α, the lagging strand replicase is the major contributor to DNA mutagenesis. Also, RNase H2-RED was instrumental in determining that translesion Pol η is involved in DNA synthesis of difficult to replicate regions in lagging strand. Perhaps most importantly, RNase H2-RED definitively proved that RER activity is essential during mammalian development and that in mammals, like in yeast, Top1 processing of rNMPs embedded in DNA leads to DNA damage. RNase H2-RED helped to answer the question of why there is redundancy between RNase H1 and RNase H2 in resolving RNA/DNA hybrids by showing that there are specific substrates for each enzyme for which the other has no access or cannot cleave. We are confident that RNase H2-RED still has many secrets to uncover. Because the two activities of RNase H2, initiation of RER and removal of RNA/DNA hybrids, are intimately related, both preventing replicative stress, mutagenesis and DNA damage, we believe that to have a full picture of the consequences of RNase H2 defects, the opposite mutant of RED, one that retains rNMP processing but lacks hybrids removal, namely RNase H2-HD (for Hybrid Defective) needs to be obtained and studied. Only with the complementary studies of RNase H2-RED and RNase H2-HD we will be able to have a more complete understanding of the functions of this fascinating enzyme crucial in all eukaryote cells.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

Glossary

- Hydroxyurea (HU) effect on replicative stress

HU induces replicative stress and checkpoint activation by inhibiting ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), a key enzyme in de novo path of dNTP synthesis which catalyzes the reduction of ribonucleotides into deoxyribonucleotides. HU decreases the levels of dNTPs available for DNA synthesis (Alvino et al., 2007).

- Long INterpersed Element class 1 (LINE-1) are processed by RNase H2

LINE-1 elements are a type of retrotransposon that comprise a large portion of the mammalian genome. Most of them are inactive but a small number can mobilize in the host genome (Beck et al., 2010; Brouha et al., 2003), with the risk of generating mutations that can lead to genetic disorders (García-Muse and Aguilera, 2016). The process of retrotransposition includes the degradation of the RNA component of the RNA/DNA hybrid created by reverse transcription of the LINE-1 RNA. Higher eukaryotic LINE-1 elements do not code for a RNase H enzyme and rely on the host RNase H2 to eliminate the RNA strand (Bartsch et al., 2017; Benitez-Guijarro et al., 2018) (see fig.4).

- Loss of Heterozygosity

Diploid cells can have different sequences on each of two homologous chromosomes, a condition termed heterozygosity. When one chromosome is used as a template to “repair” the other, loss of heterozygosity occurs by gene conversion (a recombination event). Physical loss of a region due to chromosome breakage also can result in loss of heterozygosity. Gene conversion restores homozygosity. Physical loss results in only one copy (hemizygosity).

- Replicative DNA polymerases

Nuclear DNA is replicated by three members of the B family of DNA polymerases (Pols), Pol α, Pol ε and Pol δ. Leading strand DNA is synthesized processively by Pol ε after primer synthesis by Pol α and lagging strand DNA is synthesized by Pol α and Pol δ in Okazaki Fragments (OF) that need processing and maturation (Nick McElhinny et al., 2008). Replicative Pols are highly selective for the base and sugar of the incoming dNTP due to their narrow active site and proofreading ability (Joyce, 1997; Kunkel, 2009). The “steric gate” a bulky amino acid in the catalytic center prevents the entrance of rNTPs (Brown and Suo, 2011). The frequency of utilization of rNTPs differs for each of the three replicative polymerases. Changing amino acids around the steric gate can lead to more or fewer rNTPs being able to access the active site. In S. cerevisiae the mutant Polε-M644L enzyme is less prone to incorporate rNMPs, while the Polε -M644G variant allows more frequent insertions of rNMPs; the difference in rNMP incorporation between these two polymerase is about 30-fold, which in the absence of RNase H2 would greatly affect the rNMP density in genomic DNA and their associated defects (Nick McElhinny et al., 2010a; Williams et al., 2015).

- Ribonucleotide Excision Repair (RER)

RER is initiated by RNase H2, which incises at the 5’-end of the rNMP creating a nick whose upstream free 3’OH end is subsequently extended by the OF maturation machinery, which includes displacement synthesis by Pol δ, flap removal by Fen1 or Dna2, and finally ligation by DNA ligase 1 (Sparks et al., 2012).

- R-loops

A three-stranded structure created when the RNA extruded from the RNA polymerase fails to engage with the post-transcriptional machinery and instead falls back and hybridizes to the template DNA strand, leaving the non-template strand in ssDNA form (Drolet et al., 1995; Huertas and Aguilera, 2003; Li and Manley, 2005).

- Topoisomerase 1 dual and opposing roles in preventing and inducing genomic instability

Topoisomerase 1 (Top1) releases torsional stress created during replication and transcription by the advancing polymerases (Pommier et al., 2016). To prevent supercoiling, Top1 introduces a cut in one of the DNA strands allowing unwinding before religating the nick. Negative torsion behind the RNA polymerase can facilitate R-loops formation, which would impede transcription and DNA replication (Wahba et al., 2011). In this way, Top1 preserves genome integrity by preventing R-loop establishment. However, if an rNMP remains in DNA when RER is defective, Top1 creates a 2’–3’ cyclic phosphate that cannot be religated, resulting in a ssDNA break (SSB) (cho and Jinks-Robertson, 2018). To repair this DNA damage, Top1 can nick the same strand upstream of the unligatable end inducing a signature 2–5 bp deletion in short tandem repeats (Sparks and Burgers, 2015), or nick at the opposite strand creating a dsDNA break (DSB) (Huang et al., 2017). During replication, Top1 incisions and related mutagenesis and DNA damage are mostly associated with processing of leading-strand DNA supercoiling (Williams et al., 2015). Therefore, in the absence of RNase H2, Top1 action at rNMPs embedded in DNA can cause genome instability.

- Translesion polymerases

Translesion DNA polymerases are specialized replicases that can copy template DNA containing a variety of lesions (Goodman and Woodgate, 2013). To accomplish that, they have spacious active sites to accommodate the bulky adducts that they encounter in damaged DNA (Ling et al., 2001; Yang and Woodgate, 2007). They also have “steric gate” amino acids that limit incorporation of rNMPs during DNA synthesis (Donigan et al., 2015). Most translesion Pols belong to the X and Y families of DNA polymerases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

References

- Abeshouse A, Ahn J, Akbani R, Ally A, Amin S, Andry Christopher D., Annala M, Aprikian A, Armenia J, Arora A, et al. (2015). The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell 163, 1011–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aden K, Bartsch K, Dahl J, Reijns MAM, Esser D, Sheibani-Tezerji R, Sinha A, Wottawa F, Ito G, Mishra N, et al. (2019). Epithelial RNase H2 Maintains Genome Integrity and Prevents Intestinal Tumorigenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology 156, 145–159.e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait Saada A, Lambert SAE, and Carr AM (2018). Preserving replication fork integrity and competence via the homologous recombination pathway. DNA Repair 71, 135–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen-Soltero S, Martinez SL, Putnam CD, and Kolodner RD (2014). A saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase H2 interaction network functions to suppress genome instability. Mol Cell Biol 34, 1521–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvino GM, Collingwood D, Murphy JM, Delrow J, Brewer BJ, and Raghuraman MK (2007). Replication in Hydroxyurea: It’s a Matter of Time. Mol Cell Biol 27, 6396–6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arudchandran A, Cerritelli S, Narimatsu S, Itaya M, Shin D-Y, Shimada Y, and Crouch R (2000). The absence of ribonuclease H1 or H2 alters the sensitivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to hydroxyurea, caffeine and ethyl methanesulphonate: implications for roles of RNases H in DNA replication and repair. Genes Cells 5, 789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch K, Knittler K, Borowski C, Rudnik S, Damme M, Aden K, Spehlmann ME, Frey N, Saftig P, Chalaris A, et al. (2017). Absence of RNase H2 triggers generation of immunogenic micronuclei removed by autophagy. Hum Mol Genet 26, 3960–3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CR, Collier P, Macfarlane C, Malig M, Kidd JM, Eichler EE, Badge RM, and Moran JV (2010). LINE-1 Retrotransposition Activity in Human Genomes. Cell 141, 1159–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez-Guijarro M, Lopez-Ruiz C, Tarnauskaitė Ž, Murina O, Mian Mohammad M, Williams TC, Fluteau A, Sanchez L, Vilar-Astasio R, Garcia-Canadas M, et al. (2018). RNase H2, mutated in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome, promotes LINE-1 retrotransposition. EMBO J. 37, e98506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergoglio V, Boyer A-S, Walsh E, Naim V, Legube G, Lee MYWT, Rey L, Rosselli F, Cazaux C, Eckert KA, et al. (2013). DNA synthesis by Pol η promotes fragile site stability by preventing under-replicated DNA in mitosis. J Cell Biol 201, 395–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KA, Shor E, Sunjevaric I, Fumasoni M, Burgess RC, Foiani M, Branzei D, and Rothstein R (2009). Sgs1 function in the repair of DNA replication intermediates is separable from its role in homologous recombinational repair. EMBO J 28, 915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouha B, Schustak J, Badge RM, Lutz-Prigge S, Farley AH, Moran JV, and Kazazian HH (2003). Hot L1s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 5280–5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA, and Suo Z (2011). Unlocking the Sugar “Steric Gate” of DNA Polymerases. Biochemistry 50, 1135–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli SM, and Crouch RJ (2009). Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J 276, 1494–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli SM, and Crouch RJ (2016). The Balancing Act of Ribonucleotides in DNA. Trends Biochem Sci 41, 434–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J-E, and Jinks-Robertson S (2018). Topoisomerase I and Genome Stability: The Good and the Bad. Methods Mol Biol 1703, 21–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Hwang S-Y, and Ahn K (2018). Interplay between RNASEH2 and MOV10 controls LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 1912–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon H, Matsumura H, Koga Y, Takano K, and Kanaya S (2006). Crystal Structure and Structurebased Mutational Analyses of RNase HIII from Bacillus stearothermophilus: A New Type 2 RNase H with TBP-like Substrate-binding Domain at the N Terminus. J Mol Biol 356, 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon H, Sparks JL, Rychlik M, Nowotny M, Burgers PM, Crouch RJ, and Cerritelli SM (2013). RNase H2 roles in genome integrity revealed by unlinking its activities. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 3130–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon H, Vassilev A, DePamphilis ML, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Burgers PM, Crouch RJ, and Cerritelli SM (2009). Contributions of the two accessory subunits, RNASEH2B and RNASEH2C, to the activity and properties of the human RNase H2 complex. Nucleic Acids Res 37, 96–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen AR, Lujan SA, Burkholder AB, Orebaugh CD, Williams JS, Clausen MF, Malc EP, Mieczkowski PA, Fargo DC, Smith DJ, et al. (2015). Tracking replication enzymology in vivo by genome-wide mapping of ribonucleotide incorporation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22, 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin SR, Hollis T, and Perrino FW (2011). Functional Consequences of the RNase H2A Subunit Mutations That Cause Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome. J Biol Chem 286, 16984–16991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover HN, Lujan SA, Chapman MJ, Cornelio DA, Sharif R, Williams JS, Clark AB, Camilo F, Kunkel TA, and Argueso JL (2015). Stimulation of Chromosomal Rearrangements by Ribonucleotides. Genetics 201, 951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelio DA, Sedam HN, Ferrarezi JA, Sampaio NM, and Argueso JL (2017). Both R-loop removal and ribonucleotide excision repair activities of RNase H2 contribute substantially to chromosome stability. DNA Repair (Amst) 52, 110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley MP, Bocek M, and Cimprich KA (2019). R-Loops as Cellular Regulators and Genomic Threats. Mol Cell 73, 398–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Leitch A, Hayward BE, Garner A, Parmar R, Griffith E, Ali M, Semple C, Aicardi J, Babul-Hirji R, et al. (2006). Mutations in genes encoding ribonuclease H2 subunits cause Aicardi-Goutières syndrome and mimic congenital viral brain infection. Nat Genet 38, 910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donigan KA, Cerritelli SM, McDonald JP, Vaisman A, Crouch RJ, and Woodgate R (2015). Unlocking the steric gate of DNA polymerase eta leads to increased genomic instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst) 35, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M, Phoenix P, Menzel R, Massé E, Liu LF, and Crouch RJ (1995). Overexpression of RNase H partially complements the growth defect of an Escherichia coli delta topA mutant: R-loop formation is a major problem in the absence of DNA topoisomerase I. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 92, 3526–3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder PS, and Walder JA (1991). Ribonuclease H from K562 human erythroleukemia cells. Purification, characterization, and substrate specificity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 266, 6472–6479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder PS, Walder RY, and Walder JA (1993). Substrate specificity of human RNase H1 and its role in excision repair of ribose residues misincorporated in DNA. Biochimie 75, 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hage A, French SL, Beyer AL, and Tollervey D (2010). Loss of Topoisomerase I leads to R-loop-mediated transcriptional blocks during ribosomal RNA synthesis. Genes Dev 24, 1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epshtein A, Potenski C, and Klein H (2016). Increased spontaneous recombination in RNase H2-deficient cells arises from multiple contiguous rNMPs and not from single rNMP residues incorporated by DNA polymerase epsilon. Microb Cell 3, 248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figiel M, Chon H, Cerritelli SM, Cybulska M, Crouch RJ, and Nowotny M (2011). The structural and biochemical characterization of human RNase H2 complex reveals the molecular basis for substrate recognition and Aicardi-Goutières syndrome defects. J Biol Chem 286, 10540–10550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figiel M, and Nowotny M (2014). Crystal structure of RNase H3-substrate complex reveals parallel evolution of RNA/DNA hybrid recognition. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 9285–9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fungtammasan A, Walsh E, Chiaromonte F, Eckert KA, and Makova KD (2012). A genome-wide analysis of common fragile sites: What features determine chromosomal instability in the human genome? Genome Res 22, 993–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Muse T, and Aguilera A (2016). Transcription–replication conflicts: how they occur and how they are resolved. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17, 553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimo CL, and Zakian VA (2016). Getting it done at the ends: Pif1 family DNA helicases and telomeres. DNA Repair 44, 151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs PEM, McDonald J, Woodgate R, and Lawrence CW (2005). The Relative Roles in Vivo of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pol η, Pol ζ, Rev1 Protein and Pol32 in the Bypass and Mutation Induction of an Abasic Site, T-T (6–4) Photoadduct and T-T cis-syn Cyclobutane Dimer. Genetics 169, 575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginno PA, Lim YW, Lott PL, Korf I, and Chedin F (2013). GC skew at the 5’ and 3’ ends of human genes links R-loop formation to epigenetic regulation and transcription termination. Genome Res 23, 1590–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodier JL (2016). Restricting retrotransposons: a review. Mobile DNA 7, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MF, and Woodgate R (2013). Translesion DNA Polymerases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther C, Kind B, Reijns MA, Berndt N, Martinez-Bueno M, Wolf C, Tungler V, Chara O, Lee YA, Hubner N, et al. (2015). Defective removal of ribonucleotides from DNA promotes systemic autoimmunity. J Clin Invest 125, 413–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamperl S, and Cimprich KA (2016). Conflict Resolution in the Genome: How Transcription and Replication Make It Work. Cell 167, 1455–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegnauer AM, Hustedt N, Shimada K, Pike BL, Vogel M, Amsler P, Rubin SM, van Leeuwen F, Guénolé A, van Attikum H, et al. (2012). An N-terminal acidic region of Sgs1 interacts with Rpa70 and recruits Rad53 kinase to stalled forks. EMBO J 31, 3768–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller B, Achleitner M, Glage S, Naumann R, Behrendt R, and Roers A (2012). Mammalian RNase H2 removes ribonucleotides from DNA to maintain genome integrity. J Exp Med 209, 1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SN, Williams JS, Arana ME, Kunkel TA, and Pommier Y (2017). Topoisomerase I-mediated cleavage at unrepaired ribonucleotides generates DNA double-strand breaks. EMBO J 36, 361–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas P, and Aguilera A (2003). Cotranscriptionally Formed DNA:RNA Hybrids Mediate Transcription Elongation Impairment and Transcription-Associated Recombination. Mol Cell 12, 711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce CM (1997). Choosing the right sugar: How polymerases select a nucleotide substrate. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 94, 1619–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy EM, Gavegnano C, Nguyen L, Slater R, Lucas A, Fromentin E, Schinazi RF, and Kim B (2010). Ribonucleoside Triphosphates as Substrate of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Reverse Transcriptase in Human Macrophages. J Biol Chem 285, 39380–39391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N, Huang S.-y.N., Williams JS, Li YC, Clark AB, Cho J-E, Kunkel TA, Pommier Y, and Jinks-Robertson S (2011). Mutagenic Processing of Ribonucleotides in DNA by Yeast Topoisomerase I. Science 332, 1561–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipps TJ, Stevenson FK, Wu CJ, Croce CM, Packham G, Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Gribben J, and Rai K (2017). Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3, 16096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima Y, Tam OH, and Tam PPL (2014). Timing of developmental events in the early mouse embryo. Sem Cell Dev Biol 34, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel K, Engqvist MKM, Kalm J, Thompson LJ, Boström M, Navarrete C, McDonald JP, Larsson E, Woodgate R, and Clausen AR (2018). DNA polymerase η contributes to genome-wide lagging strand synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res 47, 2425–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel TA (2009). Evolving Views of DNA Replication (In)Fidelity. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 74, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KS, and Merrikh H (2018). The Clash of Macromolecular Titans: Replication-Transcription Conflicts in Bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 72, 71–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro F, Novarina D, Amara F, Watt Danielle L., Stone Jana E., Costanzo V, Burgers Peter M., Kunkel Thomas A., Plevani P, and Muzi-Falconi M (2012). RNase H and Postreplication Repair Protect Cells from Ribonucleotides Incorporated in DNA. Mol Cell 45, 99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, and Manley JL (2005). Inactivation of the SR Protein Splicing Factor ASF/SF2 Results in Genomic Instability. Cell 122, 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YW, Sanz LA, Xu X, Hartono SR, and Chedin F (2015). Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation and RNA:DNA hybrid accumulation in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R, and Yang W (2001). Crystal Structure of a Y-Family DNA Polymerase in Action: A Mechanism for Error-Prone and Lesion-Bypass Replication. Cell 107, 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord CJ, and Ashworth A (2017). PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science 355, 1152–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul RW, Chon H, Sakhuja K, Cerritelli SM, Gugliotti LA, Gearhart PJ, and Crouch RJ (2017). R-Loop Depletion by Over-expressed RNase H1 in Mouse B Cells Increases Activation-Induced Deaminase Access to the Transcribed Strand without Altering Frequency of Isotype Switching. J Mol Biol 429, 3255–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meroni A, Nava GM, Bianco E, Grasso L, Galati E, Bosio MC, Delmastro D, Muzi-Falconi M, and Lazzaro F (2019). RNase H activities counteract a toxic effect of Polymerase η in cells replicating with depleted dNTP pools. Nucleic Acids Res 47, 4612–4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, and Honjo T (2000). Class Switch Recombination and Hypermutation Require Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase (AID), a Potential RNA Editing Enzyme. Cell 102, 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nick McElhinny SA, Gordenin DA, Stith CM, Burgers PMJ, and Kunkel TA (2008). Division of Labor at the Eukaryotic Replication Fork. Mol Cell 30, 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nick McElhinny SA, Kumar D, Clark AB, Watt DL, Watts BE, Lundström EB, Johansson E, Chabes A, Kunkel TA (2010a). Genome instability due to ribonucleotide incorporation into DNA. Nat Chem Biol 6,774–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nick McElhinny SA, Watts BE, Kumar D, Watt DL, Lundström E-B, Burgers PMJ, Johansson E, Chabes A, and Kunkel TA (2010b). Abundant ribonucleotide incorporation into DNA by yeast replicative polymerases. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 107, 4949–4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, and Yang W (2005). Crystal Structures of RNase H Bound to an RNA/DNA Hybrid: Substrate Specificity and Metal-Dependent Catalysis. Cell 121, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell K, Jinks-Robertson S, and Petes TD (2015). Elevated Genome-Wide Instability in Yeast Mutants Lacking RNase H Activity. Genetics 201, 963–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani N, Yanagawa H, Tomita M, and Itaya M (2004). Identification of the first archaeal Type 1 RNase H gene from Halobacterium sp. NRC-1: archaeal RNase HI can cleave an RNA–DNA junction. Biochem J 381, 795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi SL, Shoemaker DD, and Boeke JD (2003). DNA helicase gene interaction network defined using synthetic lethality analyzed by microarray. Nat Genet 35, 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orecchini E, Doria M, Antonioni A, Galardi S, Ciafrè SA, Frassinelli L, Mancone C, Montaldo C, Tripodi M, and Michienzi A (2016). ADAR1 restricts LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokatayev V, Hasin N, Chon H, Cerritelli SM, Sakhuja K, Ward JM, Morris HD, Yan N, and Crouch RJ (2016). RNase H2 catalytic core Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome-related mutant invokes cGAS-STING innate immune-sensing pathway in mice. J Exp Med 213, 329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y, O’Connor MJ, and de Bono J (2016). Laying a trap to kill cancer cells: PARP inhibitors and their mechanisms of action. Sci Transl Med 8, 362ps317–362ps317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenski CJ, and Klein HL (2014). How the misincorporation of ribonucleotides into genomic DNA can be both harmful and helpful to cells. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 10226–10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramantani G, Kohlhase J, Hertzberg C, Innes AM, Engel K, Hunger S, Borozdin W, Mah JK, Ungerath K, Walkenhorst H, et al. (2010). Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of lupus erythematosus in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 62, 1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijns MAM, Kemp H, Ding J, de Proce SM, Jackson AP, and Taylor MS (2015). Lagging-strand replication shapes the mutational landscape of the genome. Nature 518, 502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijns Martin A.M., Rabe B, Rigby Rachel E., Mill P, Astell Katy R., Lettice Laura A., Boyle S, Leitch A, Keighren M, Kilanowski F, et al. (2012). Enzymatic Removal of Ribonucleotides from DNA Is Essential for Mammalian Genome Integrity and Development. Cell 149, 1008–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik MP, Chon H, Cerritelli SM, Klimek P, Crouch RJ, and Nowotny M (2010). Crystal Structures of RNase H2 in Complex with Nucleic Acid Reveal the Mechanism of RNA-DNA Junction Recognition and Cleavage. Mol Cell 40, 658–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydberg B, and Game J (2002). Excision of misincorporated ribonucleotides in DNA by RNase H (type 2) and FEN-1 in cell-free extracts. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 99, 16654–16659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz LA, and Chédin F (2019). High-resolution, strand-specific R-loop mapping via S9.6-based DNA–RNA immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing. Nat Protoc 14, 1734–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz LA, Hartono SR, Lim YW, Steyaert S, Rajpurkar A, Ginno PA, Xu X, and Chedin F (2016). Prevalent, Dynamic, and Conserved R-Loop Structures Associate with Specific Epigenomic Signatures in Mammals. Mol Cell 63, 167–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skourti-Stathaki K, and Proudfoot NJ (2014). A double-edged sword: R loops as threats to genome integrity and powerful regulators of gene expression. Genes Dev 28, 1384–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skourti-Stathaki K, Proudfoot NJ, and Gromak N (2011). Human Senataxin Resolves RNA/DNA Hybrids Formed at Transcriptional Pause Sites to Promote Xrn2-Dependent Termination. Mol Cell 42, 794–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollier J, Stork CT, Garcia-Rubio ML, Paulsen RD, Aguilera A, and Cimprich KA (2014). Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair factors promote R-loop-induced genome instability. Mol Cell 56, 777–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks JL, and Burgers PM (2015). Error-free and mutagenic processing of topoisomerase 1-provoked damage at genomic ribonucleotides. EMBO J 34, 1259–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks JL, Chon H, Cerritelli SM, Kunkel TA, Johansson E, Crouch RJ, and Burgers PM (2012). RNase H2-initiated ribonucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell 47, 980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]