Significance

The telomerase enzyme is recruited to chromosome ends by telomeric protein TPP1 to replenish DNA that is lost during DNA replication. Although telomerase is not expressed in most of our cells, its presence is key to the continued division of stem cells and is exploited by a majority of cancers for their growth. Here, we used chimeras of mouse and human telomerase to define the regions necessary for interacting with TPP1. We then employed a multilayered, site-directed mutagenesis screen to reveal finer details of the surface that human telomerase uses to bind TPP1. Combining our data with the previously mapped interaction surface on TPP1, we present a functionally validated structural model for the human telomerase–TPP1 interaction.

Keywords: telomerase, telomeres, TPP1, telomerase processivity, telomerase recruitment

Abstract

Telomerase catalyzes telomeric DNA synthesis at chromosome ends to allow for continued cell division. The telomeric protein TPP1 is essential for enhancing the processivity of telomerase and recruiting the enzyme to telomeres. The telomerase interaction surface on human TPP1 has been mapped to 2 regions of the N-terminal oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding (OB) domain, namely the TPP1 glutamate (E) and leucine (L)-rich (TEL) patch and the N terminus of TPP1-oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding (NOB) region. To map the telomerase side of the interface, we exploited the predicted structural similarities for human and Tetrahymena thermophila telomerase as well as the species specificity of human and mouse telomerase for their cognate TPP1 partners. We show that swapping in the telomerase essential N-terminal (TEN) and insertions in fingers domain (IFD)-TRAP regions of the human telomerase catalytic protein subunit TERT into the mouse TERT backbone is sufficient to bias the species specificity toward human TPP1. Employing a structural homology-based mutagenesis screen focused on surface residues of the TEN and IFD regions, we identified TERT residues that are critical for contacting TPP1 but dispensable for other aspects of telomerase structure or function. We present a functionally validated structural model for how human telomerase engages TPP1 at telomeres, setting the stage for a high-resolution structure of this interface.

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that catalyzes the synthesis of telomeric DNA at chromosome ends using an internal RNA template (1, 2). The telomerase enzyme includes TERT and telomerase RNA (TR), the catalytic protein subunit and template-encompassing RNA subunit, respectively (2–4). Telomerase counters telomere shortening, enabling germline and somatic stem cells to uphold continued division. Although normal nondividing somatic cells completely lack telomerase expression, illicit activation of telomerase is a hallmark of an overwhelming majority of cancers (5). Telomerase has been pursued aggressively for anticancer drug discovery, but the lack of a high-resolution structure of the human enzyme has impeded the development of structure-guided therapeutic interventions.

Telomerase recruitment to telomeres is facilitated by TPP1 (6, 7), 1 of 6 members of the shelterin complex (consisting of TRF1, TRF2, Rap1, TIN2, POT1, and TPP1) that primarily serves to protect chromosome ends from being recognized as damaged DNA (8). A cluster of conserved residues on the surface of the N-terminal oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding (OB) domain of human TPP1 (hTPP1), coined the TPP1 glutamate (E) and leucine (L)-rich (TEL) patch, is critical for stimulating telomerase repeat addition processivity (referred to as processivity here onward) in vitro and for recruiting telomerase to telomeres for telomere-length maintenance (9–11) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Recently, we discovered that mutations in the extreme N terminus of the TPP1-oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding (NOB) region phenotypically mimic mutations in the TEL patch (12) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Interestingly, the NOB region is relatively well conserved across human and other mammals but not in mouse. This difference contributes to the species specificity of the telomerase–TPP1 interaction for human vs. mouse, evidenced by the fact that, although human TERT (hTERT) and mouse TERT (mTERT) share 62% sequence identity, their associated telomerases are preferably stimulated by their cognate TPP1 partners (12, 13). Mutations in both the TEL patch and NOB region are associated with telomeropathies. An in-frame deletion of K170, which is surrounded by residues identified as part of the TEL patch, causes telomerase recruitment defects in 2 unrelated individuals suffering from either aplastic anemia or Hoyeraal–Hreidarsson syndrome (14–16) (yellow in SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Similarly, mutations V94I and L95Q in the NOB region of hTPP1 have recently been associated with individuals presenting dyskeratosis congenita-like symptoms (17). Together, the NOB and TEL patch constitute an expansive surface on hTPP1 that is important for interacting with telomerase.

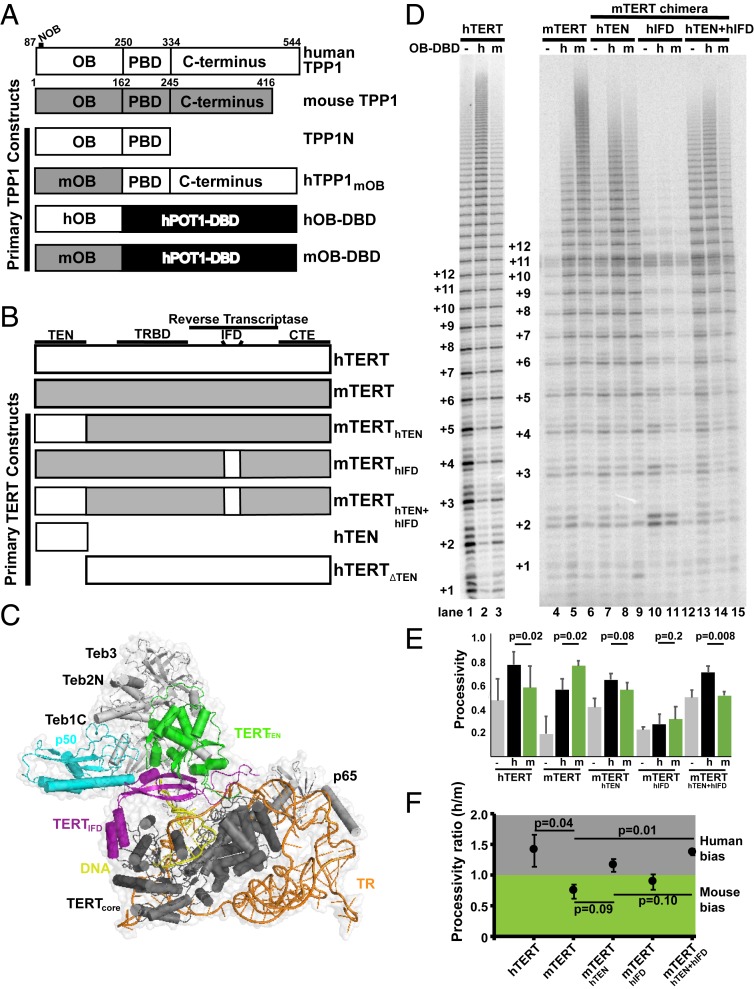

Fig. 1.

Telomerase reconstituted from mTERT containing hTEN and hIFD-TRAP regions is preferentially stimulated by hTPP1. (A) Schematic for human (white) and mouse (gray) TPP1 and their constructs. The OB domain, POT1-binding domain (PBD), and C terminus are marked with amino acid boundary numbers. Construct hTPP1mOB is a chimera of hTPP1 that contains the mOB domain swapped for the human sequence. OB-DBD chimeras consist of the hOB or mOB region of TPP1 linked to the human POT1 DNA binding domain (DBD). (B) Domain organization of hTERT (white), mTERT (gray), and engineered hybrid/deletion proteins. Landmarks of TERT include the TEN domain, telomerase RNA-binding domain (TRBD), reverse transcriptase domain, IFD, and CTE (or thumb domain). (C) T. thermophila telomerase cryo-electron microscopy structure at 4.8-Å resolution (Protein Data Bank ID code 6D6V) with TERT shown in 3 parts to denote the TEN domain (green), the IFD (purple), and core (dark gray); TR (orange), the DNA substrate (yellow), the putative TPP1 ortholog p50 (blue), and p65 and modeled components of the TEB1-3 heterotrimer (light gray) are shown. (D) Direct primer extension assay to assess species-specific stimulation of the chimeric telomerases. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were transfected to express hTR and FLAG-hTERT (lanes 1 to 3), FLAG-mTERT (lanes 4 to 6), FLAG-mTERThTEN (lanes 7 to 9), FLAG-mTERThIFD (lanes 10 to 12), or FLAG-mTERThTEN+hIFD (lanes 13 to 15). Extension reactions were performed with cellular extracts and 1 μM a5 primer for 20 min at 30 °C and included 500 nM hOB-DBD (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, and 14), 500 nM mOB-DBD (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15), or a protein buffer control (lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, and 13). (E) Quantitation of telomerase processivity data, of which D is representative. Processivity was calculated from the signal of bands corresponding to 9 or more telomeric repeats over signal for bands with 3 or more repeats. The data represent the mean and SD of 3 or 4 separate experiments evaluated by Student’s t test for significance. (F) Quantitation of species-specific stimulation of telomerase processivity by the TPP1 OB domain shown as a ratio of telomerase processivity in the presence of hOB-DBD vs. mOB-DBD (derived from data shown in E). Ratios greater than 1.0 show a bias toward hTPP1; those less than 1.0 show a bias toward mTPP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

While much knowledge has been gleaned regarding the hTERT–hTPP1 interface from the hTPP1 side, less is known about residues on telomerase that are responsible for interacting with TPP1. At least 3 elements within TERT, namely the telomerase essential N-terminal (TEN) domain (10, 11, 13, 18), the insertions in fingers domain (IFD) (19–21), and the C-terminal extension (CTE) (11), have been implicated in telomerase recruitment (Fig. 1B). Recent studies have shown that the major role of the CTE is in RNA template association and retention of the single-stranded DNA 3′ end in the active site, suggesting that this region is probably not directly responsible for binding TPP1 (22, 23). The TEN and IFD regions are signature elements of TERT orthologs that appear to be structurally conserved among ciliate, yeast (budding and fission yeast), and animal homologs (19, 24, 25). Mutations in the Dissociates Activities of Telomerase region of the TEN domain that render telomerase catalytically active in vitro, but unable to function in cultured cells, provided initial clues as to the importance of the TEN domain for telomerase recruitment to telomeres (26). Follow-up studies pinpointed residues important for mediating TPP1 effects, including a charge swap experiment that implied a direct interaction between K78 of the TEN domain of hTERT and E215 of the TEL patch of hTPP1 (13, 18). The importance of the IFD in telomerase recruitment is consistent with observations that telomeropathy-associated mutations in this region reduce telomerase recruitment to telomeres and stimulation of telomerase processivity by POT1-TPP1 (21, 27). However, a rigorous structure-function analysis akin to the screen that led to the discovery of the TEL patch of TPP1 has not been performed on telomerase largely due to its size and macromolecular complexity.

The recently solved 8-Å cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of human telomerase indicates that the TEN and IFD regions in hTERT are juxtaposed (28) as originally suggested in the 9-Å structure of Tetrahymena thermophila telomerase (hereafter referred to as Tetrahymena telomerase) (29) (Fig. 1C). However, the current structural analysis of the human enzyme is missing the POT1-TPP1 subcomplex as well as high-resolution data that are needed to understand how human telomerase is recruited to telomeres. Critical insights into both the ciliate and human telomerase–telomere engagement mechanism have been gleaned from the recent 4.8-Å structure of Tetrahymena telomerase (23) (Fig. 1C). The ciliate holoenzyme structure includes the N-terminal OB fold of p50, a protein that seems to be the Tetrahymena ortholog of TPP1. Similar to other reverse transcriptase proteins, including that from Tribolium casteneum (30), the Tetrahymena telomerase TERT IFD consists of 2 bracing α-helices that contact each other and the core of the enzyme. In the Tetrahymena telomerase structure, an elongated β-sheet domain called “IFD-TRAP” lies between these helices and seems conserved among TERT homologs except T. casteneum TERT (23). Overall, the IFD forms an L-shaped structure in which the central β-sheet coalesces with the TEN domain to form a solitary docking site for p50 (23) (Fig. 1C).

For mapping the TPP1 interaction surface on telomerase, we exploited the putative structural homology between ciliate and human telomerase and our prior success in exploiting species-specific differences to discover hTERT binding residues within hTPP1 (12). Our studies demonstrate that the TEN and IFD-TRAP regions of human telomerase and specific amino acids therein are critical elements for telomerase recruitment to telomeres. These results set the stage for high-resolution structure determination of the human telomerase–TPP1 interface.

Results

Both the hTEN Domain and hIFD-TRAP Contribute to Species Specificity and Activation of Telomerase by hTPP1.

Applying a site-directed mutagenesis approach to map the interaction surface of TPP1 and TERT was practical for the small, structurally defined N-terminal OB domain of TPP1, but a similar approach is arduous for a protein the size of TERT. To simplify this task, we exploited the species specificity of human and mouse telomerase for their respective TPP1 partners. Based on the Tetrahymena telomerase cryo-EM structure, we hypothesized that the TEN and IFD regions of hTERT are involved in binding the OB domain of hTPP1. To test this, we first engineered TERT mouse–human chimeras in which the hTEN and/or hIFD were incorporated into the mTERT backbone (Fig. 1 B and C). We then examined the species-specific bias of the resulting recombinant telomerases for TPP1 using the telomerase primer extension assay (Fig. 1 D–F). To produce recombinant telomerase, constructs for expression of human (h), mouse (m), and human–mouse hybrid TERT were cotransfected with an expression plasmid encoding hTR in human human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells as described previously (31). The human TR was used in place of the mouse sequence to allow comparison of mTERT with hTERT without complications from species-specific TR features and to overcome the inherently low in vitro activity of mouse telomerase (mTERT + mTR) (12, 13, 32). The recombinant extracts produced robust basal activity as observed when standardized for FLAG-TERT expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C). Instead of employing hPOT1-hTPP1N to examine processivity stimulation, we used a fusion protein termed OB–DNA-binding domain (DBD) as reported previously (12). OB-DBD contains the (mouse or human) TPP1 OB domain (which binds telomerase) attached to the human POT1 DBD (which binds the primer) using a short linker (Fig. 1A). This enabled us to specifically test the degree of processivity stimulation by the mouse TPP1 or hTPP1 OB domains instead of measuring unrelated species-specific properties of the POT1-TPP1 heterodimer (which could differ in parameters such as POT1-DNA and POT1-TPP1 affinity). OB-DBD, but not OB alone, DBD alone, or a mixture of OB and DBD, stimulates telomerase processivity, consistent with the DBD in the fusion acting to tether telomerase (via interaction with the OB domain) to the DNA end to facilitate enhanced processivity (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and E).

In primer extension assays, processivity of the enzyme reconstituted with mTERT + hTR was preferentially stimulated by mouse OB-DBD (mOB-DBD) compared with human OB-DBD (hOB-DBD), which we describe as an h/m processivity ratio of 0.74 ± 0.11; the reverse specificity was observed for the enzyme reconstituted with hTERT + hTR, with an h/m processivity ratio of 1.40 ± 0.27 (Fig. 1D, lanes 1 to 6; quantitation is in Fig. 1 E and F) (12). The enzyme reconstituted with a TERT variant in which hTEN was swapped for mTEN in mTERT (mTERThTEN) showed a biased species specificity toward hOB-DBD while still allowing for robust stimulation by mOB-DBD as suggested by an h/m processivity ratio of 1.16 0.10 (Fig. 1D, lanes 7 to 9; quantitation is in Fig. 1 E and F).

We next asked how the IFD region influences species specificity. We limited IFD analysis to the IFD-TRAP region so as to not perturb presumed structural contacts between the IFD bracketing α-helices or their contacts with the TERT core. However, switching in the hIFD-TRAP into mTERT (mTERThIFD) yielded an active enzyme with processivity that was poorly stimulated by either hOB-DBD or mOB-DBD (Fig. 1D, lanes 10 to 12; quantitation is in Fig. 1 E and F). This result is consistent with this domain swap compromising the structural integrity of the TPP1 docking site on TERT. Most impressively, telomerase reconstituted from mTERT that was substituted with both the human TEN domain and IFD-TRAP region (mTERThTEN+hIFD) exhibited a switch in specificity toward human over mouse TPP1 (h/m processivity ratio of 1.38 ± 0.05), which is similar to that of the hTERT-containing enzyme and strikingly different from mTERT-containing enzyme (P value of 0.01) (Fig. 1F). Our result suggests that both the TEN and the IFD-TRAP regions of hTERT are important for binding hTPP1.

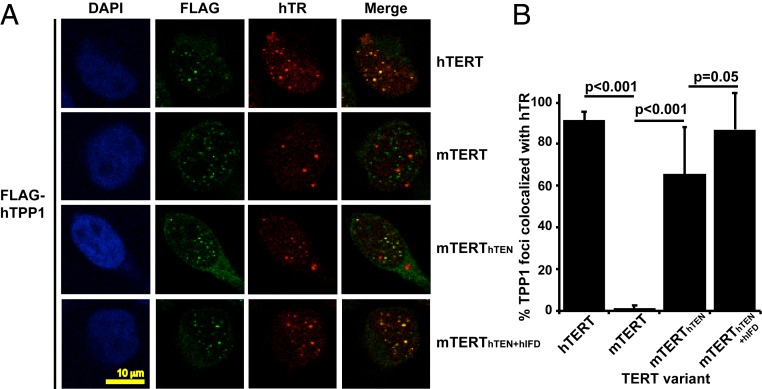

We next determined the ability of human–mouse hybrid TERTs to localize to telomeres in human cells. For this, we employed a robust immunofluorescence (IF) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay that has been performed routinely to examine telomerase recruitment to telomeres (9, 11, 18, 33–35). IF and FISH were performed to detect FLAG-TPP1 and hTR, respectively, that were coexpressed along with untagged TERT variants in a HeLa-EM2-11ht–derived cell line stably expressing FLAG-hTPP1 (9). Telomerase reconstituted with hTERT + hTR colocalizes efficiently with FLAG-hTPP1, while telomerase reconstituted with mTERT + hTR does not (Fig. 2). The loss of mTERT function is not a result of poor folding or RNP assembly, as telomerase reconstituted with this protein can be recruited to the mouse TPP1 OB domain in a HeLa-EM2-11ht–derived cell line stably expressing a variant of hTPP1 in which the mOB domain was instated in place of the human equivalent (FLAG-hTPP1mOB) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Recruitment of mTERT-containing telomerase to FLAG-hTPP1 was rescued with the introduction of the human TEN domain (construct mTERThTEN) (Fig. 2 A and B). The addition of hIFD-TRAP to hTEN in the mTERT backbone led to a further improvement in telomerase recruitment to hTPP1 that was comparable with that observed with hTERT-reconstituted telomerase (Fig. 2 A and B). Together, our primer extension and IF-FISH experiments with human/mouse hybrid TERT constructs support a role for both the TEN and IFD-TRAP regions of hTERT in binding hTPP1.

Fig. 2.

hTEN and hIFD-TRAP regions allow telomerase reconstituted from mTERT to be recruited to human telomeres. (A) IF-FISH assay for telomerase recruitment to telomeres. A HeLa-EM2-11ht–derived cell line stably expressing FLAG-hTPP1 was transiently transfected to express hTR and the indicated untagged TERT variants. DAPI shows the stained nuclei. FLAG denotes IF signal that corresponds to FLAG-TPP1 at telomeres (green). hTR indicates TR detected by FISH (red). Merge shows the extent of colocalization of recombinant telomerase with FLAG-TPP1 (yellow). (B) Quantitative analysis of telomerase recruitment data, of which the cells in A are representative. % of TPP1 foci that colocalized with TR puncta was plotted. The data represent the mean and SD of over 200 TPP1 foci evaluated by Student’s t test for significance. Twenty nuclei were examined for each experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Homology-Assisted Site-Directed Mutagenesis of hTERT to Map Its Interaction Surface with TPP1.

Our domain swap experiments identified the TEN domain (∼200 amino acids) and the IFD-TRAP (∼80 amino acids) as 2 TERT regions important for the human/mouse species specificity between telomerase and TPP1. We therefore conducted a site-directed mutagenesis screen focused on the TEN domain and IFD regions to identify hTPP1-binding residues in hTERT. We mutated residues to alanine (or in some instances, to the mTERT equivalent) that were conserved and predicted to be solvent exposed based on 1) the crystal structure of the Tetrahymena TEN domain (17% sequence identity with the human TEN domain) (24), 2) the 9-Å cryo-EM structure of Tetrahymena telomerase (as this study initiated prior to publication of the 4.8-Å structure) (29), and 3) a computational homology model for human TEN and IFD-TRAP–bound to the OB domain of hTPP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). Sixteen mutations were engineered in the TEN domain (3 double and 13 single mutants) and 11 mutations in the IFD (8 double and 3 single mutants). The previously identified hTPP1-binding mutant hTERT K78E served as a control (18). The screen was designed to identify hTERT mutations that reduced telomerase recruitment to telomeres, stimulation of telomerase by hTPP1 in vitro, and telomere elongation in cells. Defective mutations were further assessed to ensure that they did not grossly perturb TERT assembly with hTR (as verified by normal basal catalytic activity in vitro and proper TERT-TR colocalization when expressed in cells) or interactions within hTERT (screening strategy is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). The mutations that satisfied all these criteria were then mapped onto a homology model to reveal the hTERT surface involved in binding hTPP1 at telomeres.

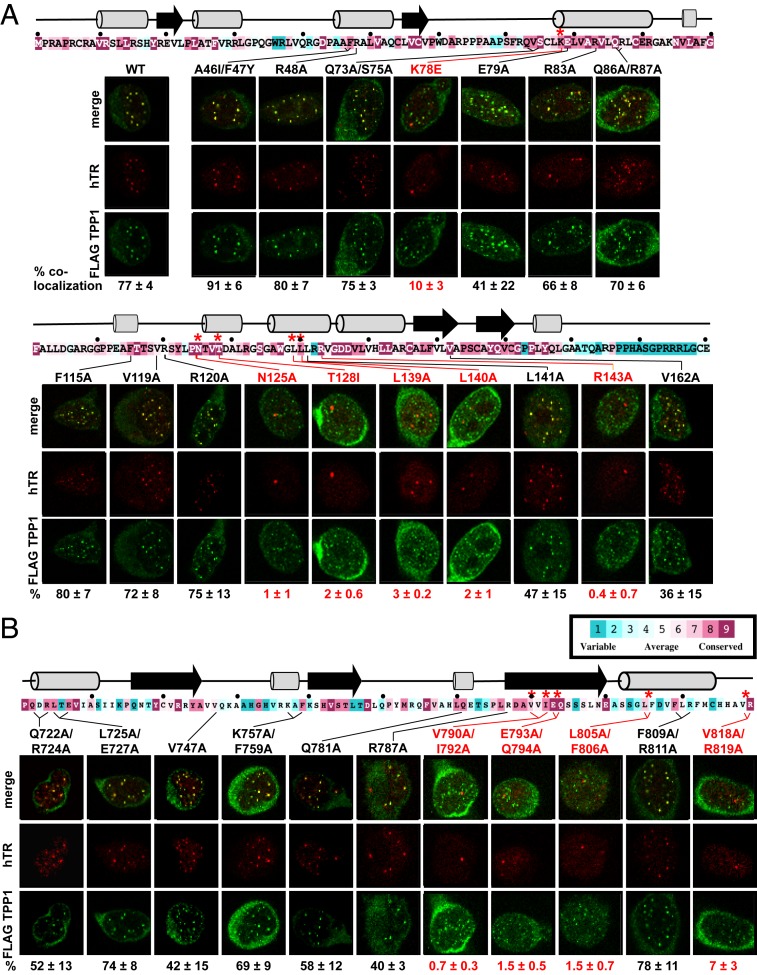

Identification of Mutations in the TEN and IFD-TRAP Regions That Disrupt Telomerase Recruitment to Telomeres.

Our first screen of the hTERT mutants for defective hTPP1 binding involved examining whether the associated reconstituted telomerase was properly recruited to telomeres coated with hTPP1. We transiently transfected untagged wild-type (WT) or mutant hTERT along with hTR in our HeLa-based stable cell line expressing FLAG-hTPP1 and performed IF (to detect FLAG-hTPP1) and FISH (to detect the TR component hTR). To measure how mutations in hTERT affected the ability of telomerase to colocalize with FLAG-hTPP1 at telomeres, we quantitated the colocalization of FLAG-hTPP1 foci with hTR. For this, we calculated the percentage of FLAG-hTPP1 foci that also contain TR (numbers at the bottom of panel series in Fig. 3; shown graphically in SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E and F). Given that this metric would overestimate telomerase recruitment defects in cells where fewer/weaker TR foci are observed (e.g., due to reduced TR expression and/or telomerase stability), we also calculated the percentage of observed TR foci that contain FLAG-hTPP1 associated with them (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 G and H). Eighteen hTERT mutants, including 11 in the TEN domain (Fig. 3A) and 7 in the IFD (Fig. 3B), showed TR-TPP1 colocalization levels similar to WT hTERT (“WT like”: A46I/F47Y, R48A, Q73A/S75A, Q86A/R87A, F115A, V119A, R120A, L725A/E727A, K757A/F759A, F809A/R811A) or ∼50% of WT hTERT (“moderately defective”: E79A, R83A, L141A, V162A, Q722A/R724A, V747A, Q781A, R787A). Both quantitation methods revealed that 5 mutants in the TEN domain (N125A, T128I, L139A, L140A, and R143A) and 4 mutants in the IFD (V790A/I792A, E793A/Q794A, L805A/F806A, and V818A/R819A) showed colocalization defects that were as or more severe than those observed with our control mutant K78E (“severely defective”) (Fig. 3, mutations and quantitation in red and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E–H). Only the group of severely defective mutants was selected for further analysis, keeping in line with the mutagenesis screen strategy employed for the discovery of the TEL patch (9). In summary, our telomerase recruitment analysis identified several mutants in the TEN and IFD regions of hTERT that are defective in colocalization with hTPP1 in human cells.

Fig. 3.

Mutations in the TEN domain and IFD-TRAP disrupt telomerase recruitment to telomeres. IF-FISH assay results for hTERT mutations in the TEN domain (A) and IFD (B) are shown in the context of their primary sequence, degree of conservation, and predicted secondary structure. ConSurf analysis (42) is shown with variable and conserved residues indicated by color (blue to pink as indicated in boxed key). Black dots denote every 10th residue, and red asterisks indicate residues with mutation that severely affects telomerase colocalization with hTPP1; for deleterious double mutants, both residues are highlighted with an asterisk. Predicted β-strands and α-helices are shown as arrows and cylinders, respectively, as predicted by SWISS-MODEL (43) except that we modeled 780-LQE-782 as an α-helix based on the sequence conservation of human L780 and Q781 with positionally related 712-DQILQE-717 helix in Tetrahymena. Above each representative image series is the corresponding mutation made in full-length hTERT and its location in the primary sequence denoted in black or red (telomere recruitment close to WT or defective, respectively). Stable HeLa-EM2-11ht clones overexpressing FLAG-hTPP1 and transiently transfected with hTR and the indicated hTERT mutant were analyzed for telomerase recruitment to telomeres using IF-FISH. FLAG-hTPP1 foci (green) were detected by IF. TR (red) was detected by FISH. Yellow/orange coloration in the merge panels signifies recruitment of hTR foci to telomeres. Below each series, the percentage of colocalization reflects the quantitation of telomerase recruitment data of which panels are representative. The mean percentage of hTPP1 foci containing hTR foci was calculated and plotted along with the SD for triplicate measurements (>100 hTPP1 foci scored in total). Data are represented in graphical form in SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E and F.

TERT Colocalizes with hTR in a Majority of the Telomere Recruitment-Deficient Mutants.

For hTERT variants that were not recruited to telomeres, the hTR staining pattern was indicative of its accumulation in Cajal bodies, an effect that is also observed in the absence of exogenous hTERT expression (36). We therefore used a second round of IF-FISH to assess proper RNP assembly by determining the ability of FLAG-tagged variants of the hTERT mutants (detected by IF) to colocalize with hTR (detected by FISH). Both WT hTERT (punctate at multiple foci consistent with telomeres [9, 11]) and hTPP1-binding defective hTERT K78E (punctate in only a few large foci [9, 11]) showed a high degree of colocalization with hTR (91 and 84%, respectively), consistent with these enzymes being efficiently assembled (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Similarly, 7 of the 9 hTERT mutants defective in hTPP1 colocalization (N125A, T128I, L139A, L140A, V790A/I792A, E793A/Q794A, and L805A/F806A) showed between 56 and 85% TERT-TR colocalization, which suggests that they do not have gross defects in RNP assembly (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In contrast, the remaining 2 variants showed severe defects: V818A/R819A showed 36% TERT-TR colocalization, and R143A gave no TERT signal. We propose that both of these mutants affect telomerase folding/assembly, fully consistent with V818 and R819 residing in 1 of the 2 bracing helices C-terminal to the IFD-TRAP and R143A showing weak basal activity in prior assays (18). Overall, these experiments reveal that 7 of the 9 telomerase recruitment-defective TERT mutants do not grossly perturb TERT-TR colocalization.

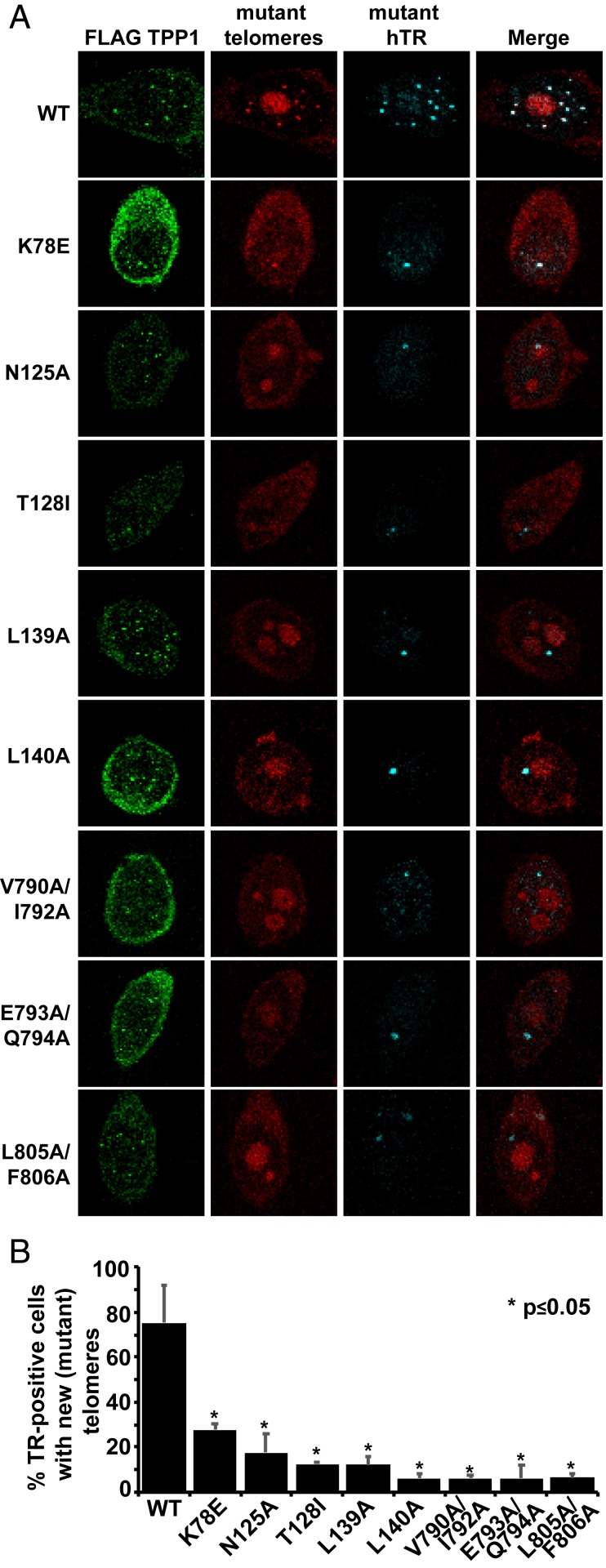

Impaired Function of Telomerase Mutants in Telomere Extension in Cells and TPP1-Dependent Processive Primer Extension In Vitro.

The hTERT mutations that disrupted proper colocalization with hTPP1 but did not appear to affect hTERT expression and colocalization with hTR were further assessed for their ability to disrupt telomere elongation in living cells. We transiently transfected our FLAG-hTPP1 HeLa-based stable cell line with WT or mutant hTERT and an hTR construct that contains mutations in its template (3′-GCCAAC-5′ instead of 3′-CCAAUC-5′) using a previously published protocol (37). The addition of new telomere repeats in vivo was visualized by FISH with a Cy3-labeled DNA probe that specifically hybridizes to mutant 5′-CGGTTG-3′ repeats instead of the canonical 5′-GGTTAG-3′ repeats. The experiment was performed under restricted time conditions (fixing cells 24 h posttransfection) (Methods) to detect newly synthesized telomeres before end deprotection (owing to the inability of POT1-TPP1 or other shelterin proteins to bind the mutant telomeric repeats) occurred. We only scored cells that showed FLAG-hTPP1 foci (detected by IF) and were properly transfected (as identified by FISH signal for the mutant hTR). Although the Cy3-labeled DNA probe designed to recognize the mutant telomeric repeat also nonspecifically hybridized to nucleolar RNA (large red foci in Fig. 4A), we did not treat the cells with RNase as per the original protocol (37) because it would have prevented our detection of mutant hTR. However, as telomeric puncta were spatially separated from nucleolar staining, the nonspecific staining did not interfere with our analysis. Punctate foci indicative of newly synthesized mutant telomeres were observable at telomeres in ∼75% of cells transfected with WT hTERT and template-mutant hTR (Fig. 4A; quantitation is in Fig. 4B). For hTERT K78E, only 28% of cells showed evidence for synthesis of newly synthesized telomeric repeats. Strikingly, an even smaller fraction of cells contained foci indicative of newly synthesized telomeres for each of the 7 telomerase recruitment-defective TERT mutants (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 4.

TEN and IFD-TRAP mutants show defects in telomere extension in cells. (A) HeLa-EM2-11ht cells stably expressing FLAG-hTPP1 were transiently transfected with TR (hTR) plasmid that contains a nontelomeric 3'-GCCAAC-5' (WT: 3'-CCAAUC-5') template sequence and indicated hTERT constructs. IF-FISH was used to visualize telomere extension by telomerase. FLAG TPP1 denotes IF signal that corresponds to hTPP1 at telomeres (green). Mutant hTR was visualized using the hTR probe already described for telomerase recruitment experiments. Mutant telomeres refer to signal from a Cy3-labeled peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe against the mutant telomere sequence (red) that was synthesized by telomerase containing the mutant RNA template. (B) Quantitation of in vivo telomere extension data of which A is representative. For each experiment, >50 cells were counted, and the mean percentage of cells with foci containing both hTR and mutant telomere signal was plotted for triplicate measurements. P values were calculated using a 2-tailed Student’s t test comparing each mutant with the WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

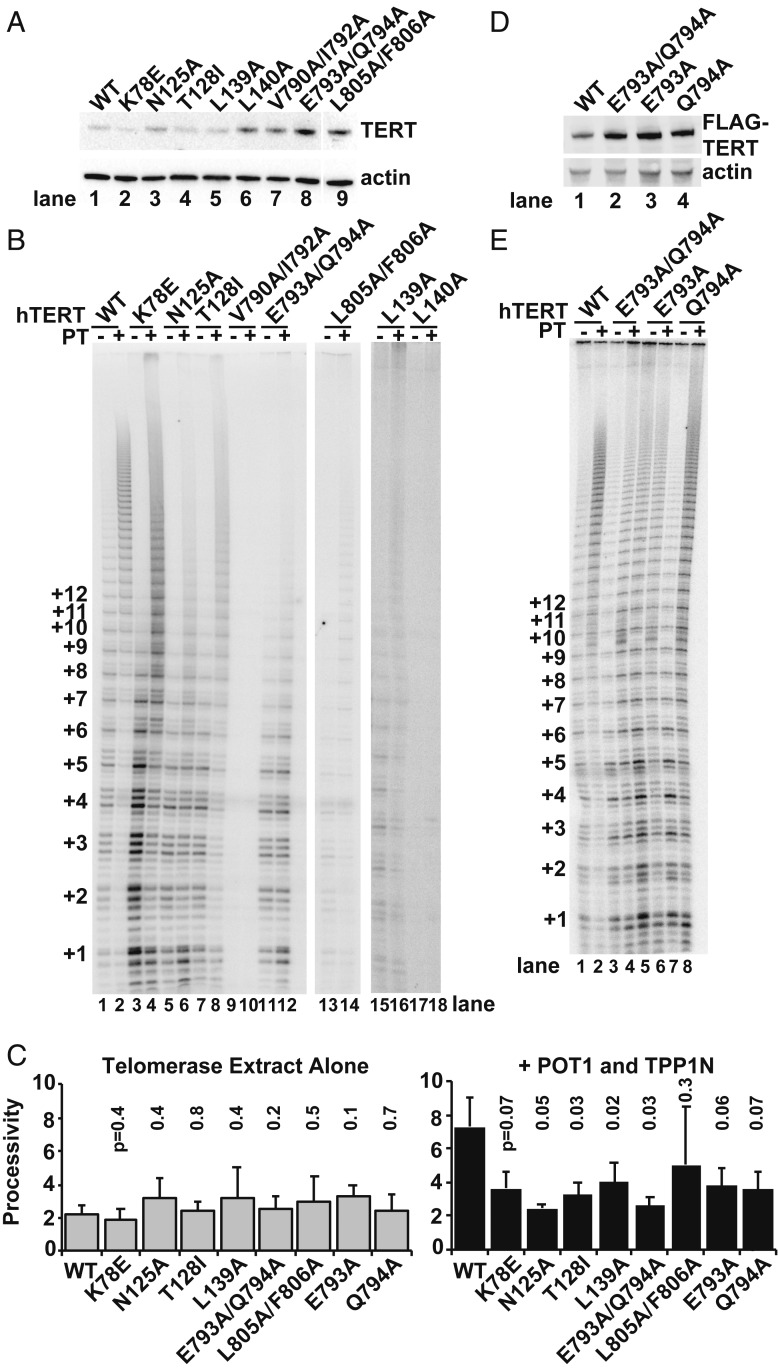

Binding of TPP1 to telomerase is central to how POT1-TPP1 stimulates its processivity, as TPP1 TEL patch and NOB mutants are unable to stimulate telomerase. hTERT with mutations at K78 in the TEN domain or V791 in the IFD-TRAP assembles into active enzymes that are moderately desensitized to added/coexpressed POT1-TPP1 (18, 21). These results suggest that TERT mutants that assemble into the RNP properly but fail to bind hTPP1 would be expected to retain catalytic activity but lose the ability to be stimulated by POT1-TPP1. We performed primer extension analysis on telomerase reconstituted from our identified set of 7 hTERT variants (Fig. 5 A–C). As reported previously, POT1-TPP1 stimulated processivity in telomerase assembled with WT hTERT compared with reactions lacking added POT1-TPP1 (compare lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 5B; quantitation is in Fig. 5C). Three mutants showed robust basal activity but were impaired in processivity stimulation by POT1-TPP1: N125A and T128I, both in the TEN domain, and E793A/Q794A in the IFD-TRAP region (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 to 8, 11, and 12; quantitation is in Fig. 5C). We further examined whether one or both of the IFD-TRAP residues E793 and Q794 contribute to the hTPP1-mediated effects. Both E793A and Q794A in FLAG-hTERT (Fig. 5D) were moderately defective, although neither was as impaired as the double mutant (Fig. 5 C and E; alternative quantitation is in SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Severe activity defects were seen for hTERT mutants V790A/I792A, L805A/F806A, and L140A, making it difficult to separate their contribution to hTPP1 binding (if any) from their likely role in hTERT folding (Fig. 5B, lanes 9, 10, 13, 14, 17, and 18). In contrast, L139A showed a milder defect in basal activity and was examined in further experiments given the fact that it clearly showed a reduced hTPP1 stimulation effect (Fig. 5B, lanes 15 and 16; quantitation is in Fig. 5C). In summary, 4 hTERT mutants surpassed our hTPP1 colocalization, hTR colocalization, telomere extension, and hTPP1-dependent processivity stimulation criteria: N125A, T128I, L139A, and E793A/Q794A.

Fig. 5.

Identifying TEN and IFD-TRAP mutants that retain catalytic potential but show defects in POT1-TPP1–mediated enhanced processivity in vitro. (A) Immunoblot of hTERT variants examined in B. The blot was probed for hTERT and actin. (B) Direct primer extension assay of lysates from HEK 293T cells transiently expressing FLAG-tagged hTERT harboring indicated TEN domain and IFD-TRAP mutants in the presence or absence of 500 nM POT1-TPP1N (abbreviated as “PT”). (C) Quantitation of telomerase processivity for data of which B and E are representative. Processivity was determined as described previously (44); n = 3, and mean processivity values are shown. P values were calculated using a 2-tailed Student’s t test. (D) Immunoblot of hTERT variants examined in E. The blot was probed for FLAG (hTERT) and actin. (E) Direct primer extension assay for lysates analyzed in D as described for B (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Assigning Mutational Defects to the TERT–TPP1 vs. the TEN–IFD Interfaces.

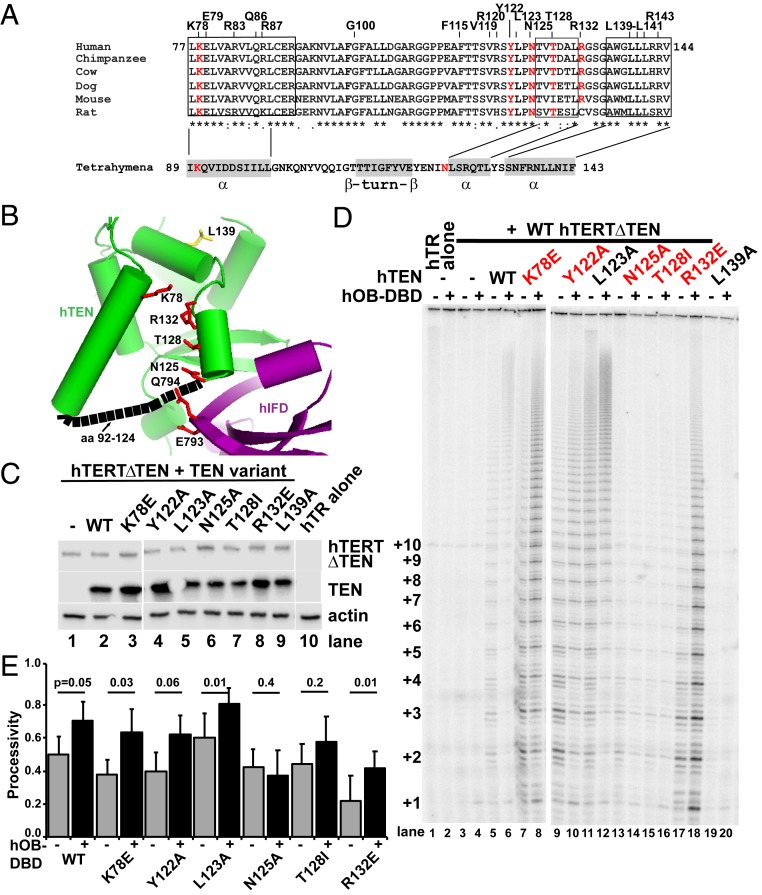

Based on the TEN domain and IFD-TRAP being associated in the Tetrahymena telomerase cryo-EM structure and our species specificity data that support their coordinated effects, we wished to exclude the possibility that our identified mutations were perturbing the TEN–(IFD-TRAP) interface or other aspects of hTERT folding dictated by the TEN domain. We took advantage of the observation that the impaired repeat addition processivity of the catalytically active core of TERT that lacks the TEN domain (TERTΔTEN) can by rescued by adding the TEN domain in trans (38, 39). Defects in TEN domain folding or its binding to the remainder of TERT should interfere with the ability of the TEN domain to stimulate processivity when added in trans to hTERTΔTEN. In contrast, mutations that solely disrupt the TERT–TPP1 interface should only show defects in presence of TPP1. We overexpressed FLAG-hTERTΔTEN along with FLAG-hTEN constructs (with mutations of residues highlighted in Fig. 6 A and B) and hTR in HEK 293T cells and prepared extracts (Fig. 6C) for primer extension analysis. As expected, hTERTΔTEN showed low processivity, which was rescued by coexpression with WT FLAG-hTEN (Fig. 6D, lanes 3 and 5). The observed bands in the presence or absence of the TEN domain resulted from the transfected hTERT (and hTR) constructs and not endogenous hTERT, as telomerase activity was barely detectible when hTR was expressed in the absence of any TERT construct (Fig. 6D, lanes 1 and 2). The characteristic POT1-TPP1–induced increased processivity was observed on addition of hOB-DBD to hTERTΔTEN trans complemented with hTEN but not in hTERTΔTEN alone (Fig. 6D, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 5 and 6), further highlighting the role of the TEN domain in binding TPP1 (Figs. 1 D–F and 2).

Fig. 6.

TEN domain trans complementation assay validates residues that mediate the telomerase–TPP1 interaction. (A) Sequence conservation of the TEN domain region spanning residues that mediate TPP1 processivity and telomerase recruitment (hTERT amino acids 77 to 144). Residues examined in this study are labeled above the aligned mammalian sequences, with red denoting amino acids with mutation that impairs TPP1-mediated processivity but does not inhibit the reconstitution of an active and processive enzyme in the TEN domain trans complementation assay shown in D. The corresponding Tetrahymena sequence and secondary structure is shown below. (B) The 3D homology model of TEN (green) and IFD (purple) regions of hTERT is based on a SWISS-MODEL–generated homology model that was modified to remove sequences lacking conservation with known structures (amino acids 92 to 124; shown in black dashed lines for connectivity). In the IFD-TRAP, the β-strands were modeled based on the Tetrahymena structure; additionally, the α-helix predicted to span 780-LQE-782, as described in Fig. 3, was modeled using the Tetrahymena Cα chain trace for its corresponding α-helix (712-DQILQK-717) as well as its connectivity to the penultimate β-strand. The side chains of TEN domain residues highlighted in red in A as well as IFD-TRAP residues E793 and Q794 are represented as red sticks with their orientation that was selected by the homology model. L139 is shown in yellow. (C) Immunoblot of extracts from HEK 293T cells cotransfected for expression of hTR alone (lane 10) or with FLAG-hTERTΔTEN (lanes 1 to 9) and the indicated FLAG-TEN variants (lanes 2 to 9). The blot was probed for FLAG and actin. (D) Direct primer extension assay of extracts analyzed in C. A representative experiment from 4 independent replicates is shown; an additional replicate is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A. Samples contain hTR alone (lanes 1 and 2) or include FLAG-hTERTΔTEN (lanes 3 to 20) and either no TEN domain (lanes 1 to 4) or the indicated FLAG-hTEN variant (lanes 5 to 20). Extension reactions were performed with 1 μM a5 primer for 1 h at 30 °C, and even-numbered lanes include 500 nM hOB-DBD, while odd-numbered lanes include a protein buffer control. (E) Quantitation of relative processivity for TEN domain trans complementation data of which D is representative. Only replicates with measurable signal to noise were used in the quantitation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Next, we examined mutants in the TEN and IFD-TRAP regions using the trans complementation assay. TEN domain mutants were examined in the context of FLAG-hTEN, while the IFD-TRAP E793/Q794 mutant was introduced in the FLAG-hTERTΔTEN backbone. The TEN domain mutants examined included mutants identified in our screen (N125A, T128I, and L139A) alongside 2 previously characterized mutations (K78E and R132E) (18, 35). We also engineered 2 additional alanine mutations of conserved residues (Y122 and L123) that are immediately upstream of residue N125—the most N-terminal TEN domain residue identified in our screen (Fig. 6 A and B). Cellular lysates were analyzed by immunoblot analysis to confirm uniform protein expression (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B), and primer extension analysis was performed to evaluate telomerase processivity under unstimulated and hTPP1-stimulated conditions (Fig. 6D; quantitation is shown in Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). All of the mutants except L139A (see below) were able to reconstitute telomerase activity on trans complementation in the absence of added hOB-DBD, eliminating the likelihood of structural defects in a majority of the tested mutants. The most striking defects for hTPP1-mediated processivity were observed for mutations at residues N125, T128, R132, and E793/Q794 (lanes 13 to 18 in Fig. 6D; quantitation is shown in Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Y122A showed a moderate hTPP1-mediated processivity defect that resembled that observed for the hTPP1-binding mutant K78E (compare lanes 8 to 10 in Fig. 6D; quantitation is shown in Fig. 6E, and replicate is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). It is unclear why the trans activation by TEN L123A is enhanced for basal and hTPP1-activated processivity when compared with WT TEN; it is possible that this mutation enhances the assembly/stability of the telomerase RNP and/or helps neighboring residues Y122 and N125 to better engage hTPP1. L139A, which showed reduced basal activity in full-length TERT primer extension experiments (Fig. 5B), showed undetectable activity in the trans complementation experiment (Fig. 6D). Along this line, we also noted that total activity was weaker and more variable across different samples and replicates in this experiment than in primer extension involving full-length hTERT. We attribute this to the lower signal to noise in the trans complementation assays and variable expression (i.e., stoichiometry) of the hTEN and hTERTΔTEN constructs across different transfections in the trans complementation experiment. In summary, we found that mutation of K78, Y122, N125, T128, R132, and E793/Q794 interfered with hTPP1-mediated processivity in the TEN domain trans complementation assay. Our experiments corroborate (K78 and R132) and expand on (Y122, N125, and T128) the collection of specific residues in the TEN domain that are critical for interacting with hTPP1 but not for hTERT folding and/or telomerase RNP assembly. We mapped these TEN domain residues along with IFD-TRAP residues E793 and Q794 on a structural homology model to reveal the nature of the hTERT–hTPP1 interface (Discussion and Fig. 7).

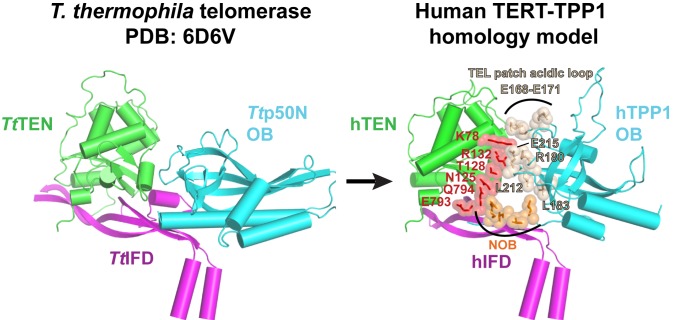

Fig. 7.

Functionally validated structural model for hTERT–TPP1. Homology model of human TEN–(IFD-TRAP) bound to hTPP1-OB constructed using the TEN and IFD-TRAP regions of Tetrahymena telomerase holoenzyme structure as template with SWISS-MODEL. The modeling assumed that hTPP1-OB is a structural homolog of the N-terminal OB domain of p50. The hTPP1-OB was placed in the model by superimposing the crystal structure of hTPP1-OB (Protein Data Bank ID code 2I46) on that of the p50 OB domain in the Tetrahymena holoenzyme structure using the DALI pairwise alignment tool (45). The resulting structure of the hTERT–hTPP1 complex was not refined postsuperimposition. The hTERT–hTPP1 interaction residues described in our functional studies are highlighted.

Discussion

The importance of the TEN and IFD-TRAP regions of hTERT in telomerase processivity and recruitment and their close juxtaposition with p50 in the Tetrahymena telomerase cryo-EM structure suggest that these domains bind hTPP1 to engage human telomerase with telomeres. Our mouse–human hybrid TERT studies confirm the importance of the hTEN domain and the hIFD-TRAP in binding hTPP1. Through a homology-directed mutagenesis screen, we identified mutants in hTEN and hIFD-TRAP that are specifically defective in telomerase recruitment and stimulation by hTPP1. Our analysis was designed to rule out residues essential for TERT-TR assembly, basal catalytic activity, or TEN–(IFD-TRAP) interaction. Mapping the hTEN and hIFD-TRAP residues identified in the mutagenesis screen to our homology model reveals that these residues lie adjacent to previously found hTPP1 contacts K78 and R132, forming an extensive surface for binding the TEL patch and NOB regions of hTPP1 (Fig. 7).

Structurally Conserved Mode of Binding for TPP1 and Telomerase.

Our homology-directed screen identified TEN domain mutants hTERT N125A and T128I as well as IFD-TRAP mutant hTERT E793A/Q794A as being impaired in telomerase recruitment to telomeres and telomeric DNA addition. Remarkably, despite the large separation of TEN domain residues N125 and T128 from IFD-TRAP residues E793 and Q794 in the primary structure, these residues map close to each other in our 3-dimensional (3D) homology model (Fig. 7). Although all of these residues are predicted to be at the junction of the TEN and IFD-TRAP, it does not appear that they are essential for formation of the TEN–(IFD-TRAP) interface per se given their robust basal activity when mutated in full-length hTERT. While we attributed part of the variations in trans complementation activities across the panel of hTERT mutants to the low signal to noise of the assay and the variable ratio of TEN and hTERTΔTEN across transfections, it is possible that the lower basal activity consistently observed for mutants, such as N125A, T128I, and E793A/Q794A (relative to the WT) (Fig. 6D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), results from their inability to associate with endogenous POT1-TPP1 in the lysate. We propose that N125, T128, E793, and Q794 form part of the core of the hTPP1-binding surface of hTERT. Furthermore, these residues cluster in the homology model of human TEN–(IFD-TRAP)-TPP1 together with previously identified hTPP1-binding basic residues K78 and R132. hTERT K78 and hTPP1 E215 form an ion pair, consistent with their proximity in our homology model (Fig. 7) (18). Finally, 2 of the hTERT amino acids we identified appear to be strictly conserved between human and Tetrahymena: hTERT K78 (K90 in Tetrahymena) and hTERT N125 (in the TEN domain, also residue N125 in Tetrahymena), further highlighting the structural conservation and importance of this TERT-TPP1–p50 interface. We further propose that Y122 (not modeled in Fig. 7), which was assayed given its conservation and proximity to N125, regulates hTPP1-mediated processivity based on its performance in our trans complementation assay.

Structural Integrity of the TEN–(IFD-TRAP) Region of Human Telomerase.

The Tetrahymena telomerase structure shows that the TEN domain and IFD-TRAP are intimately associated through an extended β-sheet that spans both domains, with the interface in the IFD-TRAP spanning residues I730 and I732, which correspond to V790 and I792 in hTERT (23). We observed that, although V790A/I792A was defective in colocalization with hTPP1 in cells, recombinant enzyme made with this TERT variant showed no basal telomerase activity in vitro. We therefore propose that the telomere recruitment defects of telomerase variant hTERT V790A/I792A are a result of disrupting the TEN–(IFD-TRAP) interface that appears to help lock the template pseudoknot region of TR onto the TERT catalytic core (23). We similarly propose that mutations of TEN domain residues L139 and L140, which reside on a helix that is partially buried in the (predicted) core of hTEN (L139 shown in Fig. 6 A and B), impair basal activity through destabilization of the TEN domain.

Convergence on a Model for Recruitment of Human Telomerase to Telomeres.

The Tetrahymena telomerase structure demonstrates how the IFD-TRAP region interacts intricately with the TEN domain to provide a contiguous surface for binding p50. Indeed, all hTERT residues implicated in binding hTPP1 (K78, Y122, N125, T128, R132, E793, and Q794) line up close to each other in our homology model (Fig. 7). Although the telomerase contacting regions of TPP1, namely the NOB and TEL patch of the OB domain, are spatially separated in the unbound crystal structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), perhaps these regions also coalesce to form a single surface for contacting hTERT. These and other insights into the interactions between hTERT and hTPP1 will have to await a high-resolution structure of the human telomerase–TPP1 interface. Given that telomerase recruitment to telomeres provides a direct target for blocking telomerase action in cancer cells, such a structure could potentially hold important implications for anticancer drug development.

Methods

Data Availability Statement.

Please contact the corresponding author for request of reagents generated in this study. There are no new datasets (e.g., large-scale sequencing, structure, code/script) generated by this study.

Molecular Cloning and Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Parental constructs that were used in this study are described elsewhere: pFBHTb-Smt3star-hPOT1 for High Five insect cell expression and purification of human POT1 (14); pET-Smt3-TPP1N for bacterial expression and purification of hTPP1N (amino acids 90 to 334) (6, 14); pET-Smt3-hOB for bacterial expression and purification of hTPP1 OB domain (amino acids 90 to 334) (6); pET-Smt3-hOB-hDBD and pET-Smt3-mOB-hDBD for bacterial expression and purification of hTPP1-OB domain (amino acids 88 to 250) or mouse TPP1-OB domain (amino acids 1 to 162), respectively, linked to human POT1 DBD (amino acids 2 to 303) (12); p3X-FLAG-TERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC or p3X-FLAG-mTERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC and phTR-BluescriptIISK(+) for overexpression of human or mouse telomerase from N-terminally 3x-FLAG–tagged TERT and hTR in HEK 293T cells, respectively (9, 12); pTERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC for expression of untagged hTERT and its variants with hTR in HeLa-derived stable cell lines (9); and p3x-FLAG-TPP1-BI4 parental vector for cloning p3x-FLAG-TPP1mOB-BI4 for Tet-inducible stable cell line generation with pd1gfpPtetmiR vector and Flp recombinase (MTA with Tet System Holdings GmbH & Co KG) (9). All experiments involving hTPP1 in human cells involved the hTPP1-S isoform (amino acids 87 to 544), which is the predominant hTPP1 isoform in somatic cells and is sufficient for all functions of TPP1, including telomerase recruitment and activation (40).

For High Five insect cell expression and purification of human POT1 DBD (amino acids 1 to 299), the pFBHTb-Smt3star-DBD plasmid was constructed using restriction-based cloning as described previously for pFBHTb-Smt3star-hPOT1 (14). For TEN domain trans complementation analysis, the human TEN domain was expressed from pCDNA3-3X-FLAG-hTEN. This construct was engineered by amplifying the sequence encoding the 3X-FLAG TEN domain (amino acids 2 to 197) from p3X-FLAG-TERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC with primers that also introduced a Kozak sequence and stop codon as well as flanking restriction enzyme sites for BamHI and EcoRI for cloning into these sites in pCDNA3. FLAG-tagged hTERT lacking the TEN domain was expressed from p3X-FLAG-hTERTΔTEN (amino acids 201 to 1,132). The construct was engineered with the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) using p3X-FLAG-TERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC as a template and complementary primers that accommodate deletion of amino acids 1 to 200 of hTERT.

The 3X-FLAG-hTPP1mOB was cloned into the pTet-IRES-eGFP-BI4 vector and subsequently subcloned into the pd1gfpPtetmiR vector as described previously (9, 12). Briefly, the TPP1mOB chimera was first cloned into pCDNA3-3X-FLAG-TPP1 by Gibson assembly to express the mouse TPP1-OB domain swapped for the equivalent sequence in hTPP1. The final construct encodes amino acids 3 to 162 from mouse and amino acids 251 to 544 from hTPP1. Sequence encoding 3X-FLAG-hTPP1mOB was subcloned by excision with NotI and XhoI and cloning into these sites in pTet-IRES-eGFP-BI4. The 3X-FLAG-hTPP1mOB-F3 was then created by digesting the BI4 vector with HpaI and BglIII and cloning into these sites of pd1gfpPtetmiR.

Single and double site-directed mutations in hTERT were introduced into p3X-FLAG-TERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC, pTERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC, pCDNA3-3X-FLAG-hTEN, and p3X-FLAG-TERTΔTENcDNA6/myc-HisC using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) and complementary mutagenic primers (Integrated DNA Technologies). The resulting plasmids were sequenced to confirm both the presence of the intended mutation and the absence of unwanted errors introduced during PCR amplification/cloning.

Chimeras of hTERT and mTERT were created by Gibson assembly with their respective p3X-FLAG-TERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC parental constructs. The resulting constructs encode the following TERT chimeras: p3X-FLAG mTERThTEN (human amino acids 2 to 198 and mouse amino acids 200 to 1,122); p3X-FLAG mTERThIFD (mouse amino acids 3 to 720, human amino acids 730 to 803, and mouse amino acids 795 to 1,122); and p3X-FLAG mTERThTEN+hIFD (human amino acids 2 to 198, mouse amino acids 200 to 720, human amino acids 730 to 803, and mouse amino acids 795 to 1,122).

For synthesis of untagged versions of mTERT, mTERThTEN and mTERThTEN+hIFD used in the IF-FISH FLAG-TPP1/hTR colocalization analysis in HeLa cells, pairs of phosphorylated oligonucleotides were designed for amplifying the entire parental FLAG-tagged vector (e.g., p3X-FLAG-mTERT-cDNA6/myc-HisC for mTERT) with the exception of the FLAG-encoding sequence. The resulting PCR products were self-ligated, and correct clones were confirmed by Sanger DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture and Stable Cell Line Engineering.

IF-FISH experiments were performed in the parental HeLa-EM2-11ht cell line or derived strains for doxycycline-inducible expression of FLAG-hTPP1 or FLAG-hTPP1mOB. The FLAG-hTPP1mOB clonal cell lines were obtained using the same procedure reported for FLAG-hTPP1 expressing stable cell lines (9). SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods has details.

Immunoblots.

Immunoblotting was performed using standard protocols. A list of antibodies, dilutions used, and analysis of immunoblots are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

IF-FISH to Monitor Telomerase Recruitment to Telomeres and Telomerase Assembly.

IF-FISH experiments for telomerase recruitment were performed exactly as described previously (16). For monitoring TERT-TR colocalization as a proxy for telomerase RNP assembly, we detected TERT by IF against the FLAG tag and TR by FISH as described in more detail in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Protein Expression and Purification.

hTPP1-N, OB-DBD, OB, DBD, and POT1 proteins were prepared as described previously using Ni-agarose affinity chromatography followed by tag cleavage and further chromatographic separation (12, 14, 16, 41). SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods has more details.

Preparation of Telomerase Extracts.

Telomerase extracts were prepared as published previously from HEK 293T cells transiently transfected with TERT- and TR-encoding plasmids (31). SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods has more details.

Direct Telomerase Activity Assays.

Telomerase assays were performed as described previously (9, 12, 16). Super telomerase extracts from HEK 293T cells were prepared as described above and examined by immunoblot analysis with an anti-FLAG antibody to ensure equal TERT expression in the extracts. The total amount of HEK 293T cell extract was standardized and typically 4 to 6 µL per reaction. Further details regarding reaction conditions and analysis of data are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Detection of In Vivo Telomere Synthesis Using Mutant TR IF-coFISH.

To monitor the synthesis of mutant telomeric DNA in HeLa-EM2-11ht–derived FLAG-hTPP1 stable cell lines, we adapted a previously published protocol (37) essentially as we described recently (40). SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods has details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Biology of Aging Training Grant T32AG000114 (to the University of Michigan Geriatrics Center from the National Institute on Aging; fellowship to E.M.S.), NIH Grants R01GM120094 (to J.N.) and R01AG050509 (to J.N.), and American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-17-037-01-DMC (to J.N.). We thank Sherilyn Grill for assistance with confocal microscopy and critical feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1911912116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Greider C. W., Blackburn E. H., Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell 43, 405–413 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greider C. W., Blackburn E. H., A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337, 331–337 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lingner J., et al. , Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science 276, 561–567 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyerson M., et al. , hEST2, the putative human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, is up-regulated in tumor cells and during immortalization. Cell 90, 785–795 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim N. W., et al. , Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 266, 2011–2015 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F., et al. , The POT1-TPP1 telomere complex is a telomerase processivity factor. Nature 445, 506–510 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xin H., et al. , TPP1 is a homologue of ciliate TEBP-beta and interacts with POT1 to recruit telomerase. Nature 445, 559–562 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palm W., de Lange T., How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 301–334 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandakumar J., et al. , The TEL patch of telomere protein TPP1 mediates telomerase recruitment and processivity. Nature 492, 285–289 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sexton A. N., Youmans D. T., Collins K., Specificity requirements for human telomere protein interaction with telomerase holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 34455–34464 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong F. L., et al. , TPP1 OB-fold domain controls telomere maintenance by recruiting telomerase to chromosome ends. Cell 150, 481–494 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grill S., Tesmer V. M., Nandakumar J., The N terminus of the OB domain of telomere protein TPP1 is critical for telomerase action. Cell Rep. 22, 1132–1140 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaug A. J., Podell E. R., Nandakumar J., Cech T. R., Functional interaction between telomere protein TPP1 and telomerase. Genes Dev. 24, 613–622 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocak H., et al. ; NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory; NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group , Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome caused by a germline mutation in the TEL patch of the telomere protein TPP1. Genes Dev. 28, 2090–2102 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y., et al. , Inherited bone marrow failure associated with germline mutation of ACD, the gene encoding telomere protein TPP1. Blood 124, 2767–2774 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisht K., Smith E. M., Tesmer V. M., Nandakumar J., Structural and functional consequences of a disease mutation in the telomere protein TPP1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 13021–13026 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tummala H., et al. , Homozygous OB-fold variants in telomere protein TPP1 are associated with dyskeratosis congenita-like phenotypes. Blood 132, 1349–1353 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt J. C., Dalby A. B., Cech T. R., Identification of human TERT elements necessary for telomerase recruitment to telomeres. eLife 3, e03563 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lue N. F., Lin Y. C., Mian I. S., A conserved telomerase motif within the catalytic domain of telomerase reverse transcriptase is specifically required for repeat addition processivity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8440–8449 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu T. W., MacNeil D. E., Autexier C., Multiple mechanisms contribute to the cell growth defects imparted by human telomerase insertion in fingers domain mutations associated with premature aging diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 8374–8386 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu T. W., D’Souza Y., Autexier C., The insertion in fingers domain in human telomerase can mediate enzyme processivity and telomerase recruitment to telomeres in a TPP1-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36, 210–222 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman H., Rice C., Skordalakes E., Structural analysis reveals the deleterious effects of telomerase mutations in bone marrow failure syndromes. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 4593–4601 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang J., et al. , Structure of telomerase with telomeric DNA. Cell 173, 1179–1190.e13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs S. A., Podell E. R., Cech T. R., Crystal structure of the essential N-terminal domain of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 218–225 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen W. F., Chico L., Lei M., Lue N. F., Telomerase regulatory subunit Est3 in two Candida species physically interacts with the TEN domain of TERT and telomeric DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20370–20375 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armbruster B. N., Banik S. S., Guo C., Smith A. C., Counter C. M., N-terminal domains of the human telomerase catalytic subunit required for enzyme activity in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7775–7786 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alder J. K., et al. , Ancestral mutation in telomerase causes defects in repeat addition processivity and manifests as familial pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001352 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen T. H. D., et al. , Cryo-EM structure of substrate-bound human telomerase holoenzyme. Nature 557, 190–195 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang J., et al. , Structure of Tetrahymena telomerase reveals previously unknown subunits, functions, and interactions. Science 350, aab4070 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillis A. J., Schuller A. P., Skordalakes E., Structure of the Tribolium castaneum telomerase catalytic subunit TERT. Nature 455, 633–637 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cristofari G., Lingner J., Telomere length homeostasis requires that telomerase levels are limiting. EMBO J. 25, 565–574 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J. L., Greider C. W., Determinants in mammalian telomerase RNA that mediate enzyme processivity and cross-species incompatibility. EMBO J. 22, 304–314 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abreu E., et al. , TIN2-tethered TPP1 recruits human telomerase to telomeres in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 2971–2982 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank A. K., et al. , The shelterin TIN2 subunit mediates recruitment of telomerase to telomeres. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005410 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stern J. L., Zyner K. G., Pickett H. A., Cohen S. B., Bryan T. M., Telomerase recruitment requires both TCAB1 and Cajal bodies independently. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2384–2395 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venteicher A. S., et al. , A human telomerase holoenzyme protein required for Cajal body localization and telomere synthesis. Science 323, 644–648 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diolaiti M. E., Cimini B. A., Kageyama R., Charles F. A., Stohr B. A., In situ visualization of telomere elongation patterns in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e176 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robart A. R., Collins K., Human telomerase domain interactions capture DNA for TEN domain-dependent processive elongation. Mol. Cell 42, 308–318 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eckert B., Collins K., Roles of telomerase reverse transcriptase N-terminal domain in assembly and activity of Tetrahymena telomerase holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 12805–12814 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grill S., et al. , Two separation-of-function isoforms of human TPP1 dictate telomerase regulation in somatic and germ cells. Cell Rep. 27, 3511–3521.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nandakumar J., Podell E. R., Cech T. R., How telomeric protein POT1 avoids RNA to achieve specificity for single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 651–656 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashkenazy H., Erez E., Martz E., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N., ConSurf 2010: Calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W529–W533 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waterhouse A., et al. , SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latrick C. M., Cech T. R., POT1-TPP1 enhances telomerase processivity by slowing primer dissociation and aiding translocation. EMBO J. 29, 924–933 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holm L., Laakso L. M., Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W351–W355 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for request of reagents generated in this study. There are no new datasets (e.g., large-scale sequencing, structure, code/script) generated by this study.