Abstract

A number of neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by deposition of abnormally phosphorylated tau or TDP-43 in disease-affected neurons. These diseases include Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. No disease-modifying therapeutics is available to treat these disorders, and we have a limited understanding of the cellular and molecular factors integral to disease initiation or progression. Phosphorylated tau and TDP-43 are important markers of pathology in dementia disorders and directly contribute to tau- and TDP- 43-related neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Here, we review the scope of tau and TDP-43 phosphorylation in neurodegenerative disease and discuss recent work demonstrating the kinases TTBK1 and TTBK2 phosphorylate both tau and TDP-43, promoting neurodegeneration.

Keywords: ALS, Alzheimer’s disease, CBD, FTLD, phosphorylation, Pick’s disease, PSP, tau, tauopathy, TDP-43, TTBK1, TTBK2

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases characterized by accumulation of protein aggregates are termed proteinopathies. In this review, we focus on two aggregating proteins, tau and TDP-43, and their role in neurodegenerative proteinopathies including AD, FTLD, and ALS. Work is ongoing to describe the molecular basis of these diseases; however, we discuss common themes relating pathological tau and TDP-43 in disease as well as new understandings of these proteins from research with model organisms. In particular, we focus on the role that phosphorylation of tau and TDP-43 has in promoting neurotoxicity, with emphasis on the kinases TTBK1 and TTBK2. TTBK 1 and TTBK2 may be targets for therapeutic intervention because they can phosphorylate both tau and TDP-43. This review describes what is known about the biology of these proteins, as well as where knowledge gaps exist, and how TTBK1/2 contribute to disease.

The role of tau in AD and FTLD-tau

Tau protein binds and stabilizes microtubules, regulating tubulin assembly [1,2]. Tau protein is particularly abundant in axons [3] and is important for cargo trafficking along the microtubule network within axons [4]. Phosphorylation of tau decreases its microtubulebinding affinity [5], resulting in destabilization of microtubules. A balance of tau-targeted kinase and phosphatase activity is crucial for microtubule homeostasis and axonal stability. During aging and disease, the balance of tau phosphorylation is disrupted, leading to accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau that no longer promotes microtubule stabilization. Unbound tau can then associate with other tau species and form soluble oligomers, which may spread between cells resulting in the propagation of aggregation-prone tau conformations. The abnormal assembly of tau into aggregates leads to a cascade of tau fibrillization and neuronal toxicity [6]. Neurodegenerative diseases characterized by the presence of abnormal tau-containing aggregates are termed tauopathies. These disorders include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD-tau), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Pick’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

AD is the most common tauopathy and the fourth leading cause of death in industrialized nations [7]. The symptoms of AD include memory loss and cognitive impairment presenting with decreased language ability and impaired abstract thinking and judgment. These symptoms are likely the consequence of significant synaptic reduction and neuronal loss, originating in the hippocampus and extending out to the cortices [8,9]. Depletion of synapses in AD can begin 20–40 years prior to diagnosis [10], indicating early stages of pathology may progress slowly. The neuropathological hallmarks of AD are the presence of both neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Neuritic plaques form by self-aggregation of amyloid-beta (Aβ), the cytotoxic product of amyloid precursor protein cleavage by the protease BACE-1 [11]. The presence of Aβ peptide precedes and may initiate subsequent tau pathology [12]. Neurofibrillary tangles form from either polymerization of tau monomers into fibrils and hyperphosphorylated tau oligomers or seeding by low level aggregates [13,14]. In AD, soluble tau oligomers can contain both 3R and 4R tau isoforms [15], and are thought to be an important toxic species in AD [16]. Nonetheless, the burden and distribution of pathological filamentous tau is strongly correlated with the severity of cognitive impairment [17,18]. Studies in mouse models of AD show tau reduction in vivo can ameliorate Aβ toxicity, demonstrating tau’s involvement in mediating amyloid- related changes [19–21]. To date, clinical trials to treat AD have all failed to arrest the course of disease or improve cognition in affected individuals [22]. In particular, numerous clinical trials that specifically target Aβ production or accumulation have been halted because the drugs successfully reduced Ab burden but were ineffective at treating cognitive impairment [23–25]. While efforts to target Aβ in disease are ongoing, the combined results from previous therapeutic drug trials, our understanding of human disease, and the biology of AD learned using model organisms all support the idea that Aβ alone does not account for cognitive decline. Taken together, data demonstrate an important role for tau in AD pathogenesis.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration, the second most prevalent form of presenile dementia after AD, affects 10–30 per 100 000 individuals between the ages of 45–65 years [26]. FTLD clinically presents with personality and behavioral changes and language dysfunction [27], driven by the deterioration of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain [26]. Roughly 40% of FTLD cases exhibit tau tangles as their primary neuropathology (FTLD-tau, Fig. 1). In FTLD-tau, tau- positive inclusions are found in both neurons and glial cells [28], which differs from the primarily neuronal tau inclusions present in AD [26]. Mutations in MAPT, the gene encoding the tau protein, cause FTDP-17, an inherited form of the disease [29,30], and account for roughly 10% of cases [26]. PSP and CBD are two aging-associated dementia syndromes with Parkinsonian features that are characterized by the presence of abnormal 4R-only tau inclusions in neurons and glia. PSP has a prevalence of 1 in 100 000 [26] and is diagnosed on the basis of supranuclear gaze palsy, Parkinson’s-like movement defects, speech deficits, progressive dementia, and posture instability [26,31–34]. However, roughly three quarters of pathologically confirmed PSP cases do not present with typical clinical indicators of PSP [35], which emphasizes the difficulties in clinical diagnosis. CBD is diagnosed on the basis of focal cortical deficits, such as limb apraxia, aphasia, and sensory loss, and progressive asymmetrical movement disorder, with a prevalence of 3 in 100 000 [26]. Though both PSP and CBD accumulate 4R tau in neurons and glia, the morphology of inclusions is distinct in each disease [36]. CBD manifests filamentous tau-positive inclusions in the hippocampus, basal ganglia, brainstem, and cerebellum. PSP accumulates both filamentous and tangle-like tau deposits in the cortex, basal ganglia, and subthalamic nucleus, as well as tufted astrocytes containing tau inclusions [37]. As in AD, there is evidence for tau oligomers driving neurodegeneration in PSP [38,39]. Furthermore, the burden of tau pathology is positively associated with the degree of cognitive impairment in PSP cases [40]. Pick’s disease is a rare form of dementia originally characterized by Arnold Pick in the late 1800s. Pick’s disease is defined by the presence of eponymous neuronal inclusions (Pick bodies) that are morphologically distinct from neurofibrillary tangles present in the cortex and dentate gyrus [41] and are composed of 3R-only tau [42]. Pick bodies positively label for both ubiquitin and paired helical filamentous tau [43]. Another distinctive pathological feature of Pick’s disease is neuronal swelling [44]. Clinically, Pick’s disease has an earlier onset than AD and has a more variable duration (from 2 to 17 years) [45]. Despite differences in clinical and pathological characteristics of PSP, CBD, and Pick’s disease, modified tau inclusions are a prominent feature of these diseases. This suggests that even if the initiating causes of these diseases differ, the mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration converge on the generation and accumulation of pathological tau.

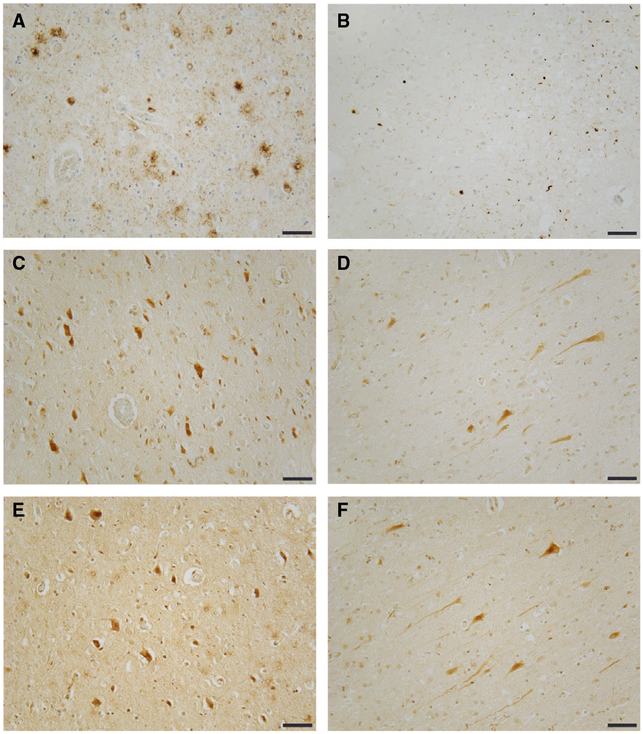

Fig. 1.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration-tau and FTLD-TDP-43 exhibit increased TTBK1 and TTBK2. (A) tau neuropathology stained with AT8 (tau pS02/pS205) from frontal cortex of an FTLD case. (B) TDP-43 neuropathology stained with pS409/pS410 TDP-43 antibody from frontal cortex of an FTLD-TDP case. (C, D) TTBK1 kinase domain-specific staining in frontal cortex of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP cases respectively. (E, F) TTBK2 kinase domain-specific staining in frontal cortex of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP cases respectively. Scale bar = 100 μM.

The molecular features of pathological tau

Although studies are ongoing, current evidence points toward hyper phosphorylated oligomeric and fibrillar tau as important toxic species in tauopathies [16,38,39]. The longest isoform of 4R tau contains 85 potential phosphorylation sites [46], many of which are phosphorylated in disease [47]. Hyperphosphorylated tau can be toxic to cells through several mechanisms. The decreased affinity of phosphorylated tau for microtubules may disrupt cargo trafficking through decreased microtubule stability, leading to axonal impairment and disruption of synapses. Hyperphosphorylation of tau also changes the ability of tau to interact with other proteins that are involved in its native function [48–50]. Furthermore, phosphorylated tau is resistant to turnover, which increases the amount of intracellular tau [51,52]. Lastly, hyperphosphorylation can promote tau aggregation.

Many kinases have been identified as tau modifiers, including glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3β) [53,54], cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) [55,56], members of the microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK), cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) families that target serine/threonine phosphorylation sites, and tyrosine kinases such as the SRC and ABL families [46]. More recently, the tau tubulin kinases 1 and 2 (TTBK1/2) were identified as kinases able to phosphorylate tau at residues Thr181, Ser202, Ser208, Ser210, Thr231, Ser396, and Ser404 [57–60]. Increased TTBK1/2 activity exacerbates tau toxicity [60,61], suggesting a role for these kinases in disease initiation or progression.

The role of TDP-43 in ALS and FTLD-TDP

Trans-activating response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43) is an RNA-binding protein with essential roles in RNA transcription, processing, and export from the nucleus, as well as mRNA transport and translation [62,63]. In normal physiological conditions, TDP-43 is located in the nucleus, but under conditions of stress or neuronal injury, it can be sequestered into cytoplasmic stress granules that potentially act as seeds for the pathological aggregation of TDP-43 observed in disease [64,65]. The TDP-43 protein contains nuclear localization and nuclear export signals, two RNA recognition motifs, and a C-terminal glycine-rich domain. Mutations in TARDBP, which encodes TDP- 43, can cause rare inherited forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS) [66–69]. These fALS mutations cluster in the C terminus of the protein. TDP-43 is the primary protein aggregate found in most cases of ALS, including both sporadic and familial-inherited forms, and is also the major protein aggregate in roughly half of all FTLD cases (FTLD-TDP, Fig. 1) [70]. In addition to ALS and FTLD-TDP, TDP-43 inclusions are a secondary pathology seen in a subset of tauopathy cases including some cases of AD, PSP, CBD, argyrophilic grain disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, as well as in other dementia disorders such as dementia with Lewy bodies [71–76].

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the most common adult onset motor neuron disorder, affects 1–2 per 100 000 individuals worldwide [77]. Symptoms include the progressive loss of motor function, leading to muscle atrophy and death. ALS-causing mutations have been identified most frequently in C9ORF72, SOD1, TARDBP, and FUS, although SOD1 and FUS mutations are not associated with TDP-43 pathology [78]. However, only a small subset of cases have a pattern of familial inheritance (10%); the majority of ALS cases (90%) are sporadic and primarily display TDP-43 neuropathology. Despite a large number of clinical trials in the past decade, only two drugs are available for the treatment of ALS. Daily administration of the FDA-approved drug Riluzole prolongs median survival by several months [79]. Another drug, Edaravone, an antioxidant developed to treat ischemic stroke, modestly slows the rate of ALS progression in a subset of patients also being treated with Riluzole. Edaravone was most effective among patients that had a definite or probable diagnosis of ALS and were symptomatic for less than 2 years [80]. There remains no significant disease-modifying treatment for ALS.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration-TDP has an age of onset of roughly 60 years and a mean duration of 8 years [28]. About 25–30% of FTLD-TDP cases are familial, and are most often associated with mutations in C9ORF72 and GRN [78]. Clinically, FTLD-TDP may present with behavioral abnormalities, progressive nonfluent aphasia, or semantic dementia [28]. FTLD-TDP is characterized by accumulation of TDP-43-positive lesions in the frontal and temporal lobes leading to reactive gliosis, widespread neuronal loss, and brain atrophy.

Pure ALS and FTLD-TDP appear to exist on opposite ends of a disease spectrum. Both ALS and FTLD- TDP share clinical, neuropathological, and genetic features that regularly occur concurrently [63,81]. In roughly half of ALS cases, there is evidence of cognitive impairment and ultimately 15% of ALS patients also get diagnosed with FTLD [82]. Similarly, about 40% of FTLD cases display motor dysfunction and 15% result in a diagnosis of motor neuron disease [83]. Both ALS and FTLD accumulate aggregated, phosphorylated TDP-43 in disease-affected neurons. Finally, ALS and FTLD-TDP are linked genetically. Expansions of an intronic hexanucleotide repeat (GGGGCC) in C9ORF72 are the most common genetic cause of ALS and FTLD-TDP [84,85]. Within C9ORF72 families, affected members can present with ALS, FTLD, or a mixed disease course with both motor and cognitive dysfunction. C9ORF72 mutation carriers accumulate TDP-43-positive inclusions as well as repeat-expansion specific features including RNA foci and dipeptide repeat inclusions. The mechanisms of disease initiation and progression in both sporadic and familial ALS and FTLD-TDP remain poorly understood. However, the common underlying pathology is the aggregation of TDP-43, and elucidating the causes and consequences of dysfunctional TDP-43 remains an important goal.

The molecular features of pathological TDP-43

Much work has been done to elucidate the mechanisms of TDP-43 toxicity. TDP-43 is an essential protein [86–88], and loss of TDP-43 function or toxic gain-of-function are both possible avenues to neurodegeneration [89]. Abundance of TDP-43 protein correlates with its neurotoxicity [90], and higher amounts of TDP-43 pathology are associated with more rapid cognitive decline [91]. TDP-43 protein is aberrantly post-translationally modified in disease states. These modifications include ubiquitination, acetylation, SUMOylation, and phosphorylation [92–95]. Of these modifications, abnormal phosphorylation of TDP-43 most consistently marks lesions in TDP-43 proteinopathies, and is used diagnostically to identify TDP-43-positive protein inclusions in brain and spinal cord [70]. TDP-43 has 64 potential sites of phosphorylation (including serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues). Only five sites have evidence for phosphorylation in disease: serines 409 and 410 (S409/410) are consistently phosphorylated in cases of TDP-43 proteinopathy, while serines 379, 403, and 404 are phosphorylated in a subset of cases [70,94–96]. Notably, all five phosphorylation sites reside in the TDP-43 C terminus. Phosphorylation at S409/410 potentiates a number of toxic disruptions in normal TDP-43 metabolism, including decreased TDP-43 protein turnover, increased TDP-43 stabilization, cellular mislocalization of TDP-43, protein aggregation, and neurodegeneration [96–101]. Four kinases have been shown to phosphorylate TDP-43: CK1, CDC7, TTBK1, and TTBK2 [96,97,102]. We do not yet know the relative contribution of each of these kinases to TDP-43 phosphorylation in disease. However, TTBK1 and TTBK2 are both upregulated in TDP-43 proteinopathy (Fig. 1) [60,102].

The tau tubulin kinase family

Tau tubulin kinase 1 and tau tubulin kinase 2 (TTBK1/2) belong to the casein kinase superfamily along with CK1. TTBK1/2 were originally characterized as kinases that phosphorylate microtubule-bound tau and are upregulated in AD cases [56,58]. In Drosophila melanogaster, the TTBK1/2 homolog Asator is an essential gene that localizes to the mitotic spindle during mitosis and directly interacts with the interchromosomal protein Magator [103]. TTBK1/2 play an important role in a variety of tauopathy disorders [57,60,104–107]. In addition to their tau-targeted activities, TTBK1/2 can directly phosphorylate TDP-43 in vitro and promote TDP-43 phosphorylation in vivo [102]. Furthermore, a reduction in TTBK1/2 levels protects against TDP-43 phosphorylation in simple models of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Finally, TTBK1/2 colocalize with phosphorylated TDP-43 in ALS and FTLD cases [102]. Taken together, these data suggest that TTBK1/2 have the potential to initiate or contribute to both tau and TDP-43 proteinopathy disorders (Figs 1–3).

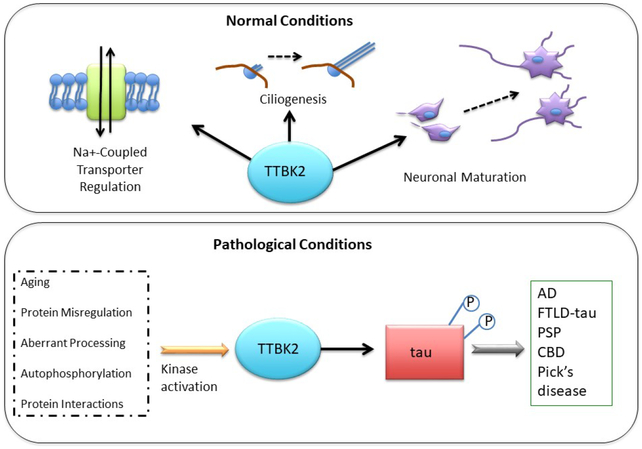

Fig. 3.

Tau tubulin kinase 2 phosphorylates tau but not TDP-43 in disease-state neurons. In healthy neurons (top), TTBK2 regulates Na+ -coupled transporters, ciliogenesis, and neuronal maturation. Dysregulated TTBK2 kinase activities (bottom) can promote pathological phosphorylation of tau and subsequent disease.

TTBK1/2 have a highly conserved homologous kinase domain (88% identity, 96% similarity between human TTBK1 and TTBK2), which is present in C. elegans, D. melanogaster, and mammalian species. The TTBK1/2 kinase domain contains dual-kinase properties enabling it to phosphorylate serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues. However, TTBK1 and TTBK2 possess mostly distinct regulatory domain sequences [107]. However, TTBK1 and TTBK2 do share one region of homology in the C terminus of the regulatory region, spanning amino acids 1053–1117 in TTBK1 and 942–1006 in TTBK2 with 43% identity and 58% similarity [107]. The N-terminal kinase domain structure for TTBK1 has been solved [108,109], and predictive modeling of TTBK2 suggests its kinase domain is functionally identical to that of TTBK1 [110]. A basic local alignment search (BLAST) targeted against the TTBK2 regulatory domains produced no significant similarities to other known proteins, pointing toward a unique regulatory mechanism for TTBK2 that is distinct from TTBK1 regulation [110]. The complete protein structures for TTBK1/2 have yet to be solved. Both TTBK1/2 undergo proteolytic processing into numerous small fragments ranging in size from 25 to 100 kDa [106] suggesting a complex native protein regulation mechanism may exist. However, the nature of TTBK1/2 regulation remains largely unexplored.

Tau tubulin kinase 1

The TTBK1 gene on chromosome 6p21.1 encodes a 1321 amino acid protein localized to the cytoplasm of the cell [57]. TTBK1 mRNA is expressed as multiple alternatively spliced isoforms predominantly in the neurons of the central nervous system and at low levels in testes [107]. TTBK1 protein includes an N-terminal kinase domain, accounting for the first 297 amino acids of the protein sequence, and a regulatory region with a unique 39-amino acid polyglutamate stretch (Fig. 4A) [107]. No other protein has been identified with a polyglutamate region this extensive, and the role it plays in TTBK1 regulation and activity remains unknown. Likewise, the function of TTBK1 is largely unknown, although recent evidence suggests a role in synaptic vesicle formation through phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) (Fig. 2) [111]. The biological function, binding partners, and overall regulation of TTBK1 activity remain mostly unknown.

Fig. 4.

Protein domains of TTBK1 and TTBK2. (A) The longest isoform of TTBK1 protein has an N-terminal kinase domain and two regulatory domains (Domain A and Domain B) separated by 39 amino acid polyglutamine stretch. (B) The longest isoform of TTBK2 has an N-terminal kinase domain and a C terminus with no homology to known protein domains. The sites of familial-inherited SCA11-causing frameshift mutations are labeled.

Fig. 2.

Tau tubulin kinase 1 phosphorylates tau and TDP-43 in disease-state neurons. In healthy neurons (top), TTBK1 promotes the formation of synapses and neuronal development. TTBK1 likely has additional unknown roles in the central nervous system. Dysregulated TTBK1 kinase activities (bottom) can promote pathological phosphorylation of tau or TDP-43 and subsequent disease.

TTBK1 is upregulated in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain [106] and colocalizes to phospho-tau in pretangles [112]. Two independent GWAS studies in Han Chinese and Spanish populations identified single nucleotide polymorphisms of TTBK1 associated with reduced risk of AD [113,114]. Another study identified a de novo variant of TTBK1 as a potential cause of childhood onset schizophrenia [115]. These findings suggest that TTBK1 plays an important role in the brain both during development and postdevelopmental aging. Transgenic mouse lines expressing full-length human TTBK1 display age-dependent cognitive and molecular changes similar to those seen in AD mouse models. These transgenic mice have learning impairments, neurofilament aggregation, microgliosis, altered CDK5/p35 activity, and decreased expression of NMDA receptors [106]. A double-transgenic mouse model expressing both mutant FTLD-causing tau and human TTBK1 had increased accumulation of oligomeric tau, enhanced motor deficits, and loss of spinal cord motor neurons [104]. Interestingly, these changes are associated with increased neuroinflammation through TTBK1-dependent activation of mononuclear phagocytes, indicating TTBK1 may promote tau toxicity through both direct phosphorylation and pro-inflammatory pathways [116]. In concert, these data suggest a key role of TTBK1 in accelerating tau-related neurodegeneration.

Tau tubulin kinase 2

The TTBK2 gene located on chromosome 15q15.2 encodes multiple alternatively spliced mRNAs that translate into a protein up to 1244 amino acids in length. TTBK2 exhibits widespread tissue distribution including expression in liver, skeletal muscle, pancreas, heart, and brain, with the highest expression levels occurring in the testes [58,107]. TTBK2 was first isolated from bovine and mouse brain samples and characterized as a kinase phosphorylating tau residues Ser208 and Ser210 [58,59]. Recent publications have demonstrated roles for TTBK2 in the initiation of ciliogenesis through the regulation of microtubule dynamics, as well as in controlling cilia length, ciliary trafficking, and stability (Fig. 3) [117,118]. TTBK2 is known to interact with EB1, EB3, and Cep164 during cilia formation [119,120]. Specifically, TTBK2 phosphorylates Cep164 when it is recruited to the basal body of a nascent cilium and regulates the removal of CP110, a suppressor of ciliogenesis [119,121]. Additionally, TTBK2 has been implicated in sodium-coupled transporter regulation [122,123]. However, characterization of TTBK2 function in neurons remains incomplete.

Mutations in TTBK2 cause an autosomal dominant form of spinocerebellar ataxia, type 11 (SCA11), a very rare progressive degenerative disease characterized by changes in gait, speech, and eye movements. The SCA11 causative TTBK2 mutations result in premature termination of the TTBK2 mRNA and depleted TTBK2 levels (Fig. 4B) [105,124,125]. TTBK2 depletion in SCA11 significantly reduces kinase activity levels and stimulates localization of TTBK2 to the nucleus, acting as a dominant negative allele that interferes with normal function of full-length TTBK2 [118,126]. Homozygous transgenic mice carrying the SCA11 mutation in TTBK2 exhibit neurodevelopmental abnormalities and are embryonic lethal [126]. These data suggest that TTBK2 is essential for proper neuronal development and may have a role in neuronal maturation. The symptoms of SCA11 are distinct from more typical symptoms of primary ciliopathies, which range from retinal degeneration and renal complications to cerebral malformation [127]. SCA11 patients accumulate phosphorylated tau inclusions in disease-affected neurons, similar to what is seen in AD [105]. This may be due to upregulation of TTBK1 that compensates for the loss of TTBK2 activity. Altered TTBK2 expression has also been associated with cancer [128], highlighting other possible functions for TTBK2 beyond cilia formation.

The therapeutic potential of the TTBKs

As described above, many age-related neurodegenerative diseases including AD, FTLD, and ALS are characterized by the presence of either phospho-tau or phospho-TDP-43. While these phosphorylated protein aggregates are diagnostic hallmarks of disease, their contributions as toxic species in disease remain a topic of debate in the field. Both tau and TDP-43 are capable of propagating disease-associated protein conformations between neurons in a prion-like manner [129]; however, the contribution of phosphorylation to this process is unknown. Similarly, whether TTBK1/2 phosphorylation of tau and TDP-43 occurs as a primary or secondary event in the initiation of proteinopathy is unknown. However, a body of literature strongly supports targeting tau or TDP-43 phosphorylation as a neuroprotective strategy [16,101,130,131].

Despite numerous clinical trials aimed at treating AD and ALS, therapies remain elusive. Targeting neurotoxicity directly through an upstream molecular pathway, which drives neurodegeneration, is a favored strategy. However, target selection is critical. Ideally, the drug target should have limited off-pathway roles. An ideal drug target would therefore be one that is expressed only in disease-relevant tissues and has no other essential cellular functions. Because TTBK1/2 phosphorylate both tau and TDP-43, they make attractive candidates for inhibition since targeting them could potentially ameliorate both tauopathies and TDP-43 proteinopathies. TTBK1 in particular is a good candidate for targeted therapeutics since its expression is largely limited to the central nervous system. TTBK2 has less favorable drug target characteristics since it is expressed in more tissue types, is essential for viability in mice, and haploinsufficiency is directly linked to disease. Additionally, TTBK1 phosphorylates both tau and TDP-43 in model systems, unlike TTBK2, which has a strong specificity for only tau [60]. This supports the idea that TTBK1 could be a viable therapeutic for both tau and TDP-43 proteinopathies, which would be particularly impactful for pathologically uncharacterized FTLD patients. While it remains an open question whether TTBK1 depletion will have neurological consequences, developing selective inhibitors of TTBK1 may be a viable approach for TTBK-focused therapeutics. However, utilizing either TTBK1 or TTBK2 as a therapeutic target will first require a better understanding of TTBK1/2 activities, regulation, and functions within the nervous system.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs [Merit Review Grant #I01BX002619 to B.K., Career Development Award 2 #I01BX007080 and Merit Review Grant #I01BX004044 to N.L.] National Institutes of Health [R01NS064131 to B.K]. LT was supported by NIA training grant (T32AG000057, P. Rabinovitch PI).

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Amyloid-beta

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CBD

Corticobasal degeneration

- fALS

Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- FTLD

frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- PSP

progressive supranuclear palsy

- SCA11

Spinocerebellar ataxia 11

- TDP-43

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 kilodaltons

- TTBK1

Tau tubulin kinase 1

- TTBK2

Tau tubulin kinase 2

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY & Kirschner MW (1975) A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72, 1858–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drubin DG & Kirschner MW (1986) Tau protein function in living cells. J Cell Biol 103, 2739–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binder LI, Frankfurter A & Rebhun LI (1985) The distribution of tau in the mammalian central nervous system. J Cell Biol 101, 1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harada A, Oguchi K, Okabe S, Kuno J, Terada S, Ohshima T, Sato-Yoshitake R, Takei Y, Noda T & Hirokawa N (1994) Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein. Nature 369, 488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drewes G, Trinczek B, Illenberger S, Biernat J, Schmitt-Ulms G, Meyer HE, Mandelkow EM & Mandelkow E (1995) Microtubule-associated protein/microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (p110mark). A novel protein kinase that regulates tau-microtubule interactions and dynamic instability by phosphorylation at the Alzheimer-specific site serine 262. J Biol Chem 270, 7679–7688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gendron TF & Petrucelli L (2009) The role of tau in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener 4, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Querfurth HW & LaFerla FM (2010) Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 362, 329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braak H & Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82, 239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR & Barnes CL (1984) Alzheimer’s disease: cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science 225, 1168–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khachaturian ZS (2000) Aging: a cause or a risk for AD? J Alzheimers Dis 2, 115–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klyubin I, Betts V, Welzel AT, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Wallin A, Lemere CA, Cullen WK, Peng Y, Wisniewski T et al. (2008) Amyloid beta protein dimer-containing human CSF disrupts synaptic plasticity: prevention by systemic passive immunization. J Neurosci 28, 4231–4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selkoe DJ (2011) Resolving controversies on the path to Alzheimer’s therapeutics. Nat Med 17, 1060–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso AC, Grundke-Iqbal I & Iqbal K (1996) Alzheimer’s disease hyperphosphorylated tau sequesters normal tau into tangles of filaments and disassembles microtubules. Nat Med 2, 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM & Binder LI (1986) Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83, 4913–4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D & Crowther RA (1989) Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 3, 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopeikina KJ, Hyman BT & Spires-Jones TL (2012) Soluble forms of tau are toxic in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Neurosci 3, 223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bussière T, Bouras C, Kӧvari E, Perl DP, Morrison JH, Gold G & Hof PR(2003) Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 60, 1495–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET & Hyman BT (1992) Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 42, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vossel KA, Zhang K, Brodbeck J, Daub AC, Sharma P, Finkbeiner S, Cui B & Mucke L (2010) Tau reduction prevents Abeta-induced defects in axonal transport. Science 330, 198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ & Mucke L (2007) Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science 316, 750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, Wolfing H, Chieng BC, Christie MJ, Napier IA et al. (2010) Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell 142, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings J (2018) Lessons learned from Alzheimer disease: clinical trials with negative outcomes. Clin Transl Sci 11, 147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkes N (2017) Merck ends trial of potential Alzheimer’s drug verubecestat. BMJ 356, j845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, Kieburtz K, He F, Sun X, Thomas RG et al. , Committee A. s. D. C. S. S. & Group, S. S. (2013) A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 369, 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung SY & Fu WM (2017) Drug candidates in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. J Biomed Sci 24, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieben A, Van Langenhove T, Engelborghs S, Martin JJ, Boon P, Cras P, De Deyn PP, Santens P, Van Broeckhoven C & Cruts M (2012) The genetics and neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 124, 353–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M et al. (1998) Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51, 1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Lee VM, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, Schneider JA, Grinberg LT, Halliday G et al. (2007) Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 114, 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A et al. (1998) Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393, 702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark LN, Poorkaj P, Wszolek Z, Geschwind DH, Nasreddine ZS, Miller B, Li D, Payami H, Awert F, Markopoulou K et al. (1998) Pathogenic implications of mutations in the tau gene in pallido-ponto-nigral degeneration and related neurodegenerative disorders linked to chromosome 17. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 13103–13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Spychalla AJ, Lowe VJ et al. (2014) The evolution of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain 137, 2783–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steele JC, Richardson JC & Olszewski J (1964) Progressive supranuclear palsy. A heterogeneous degeneration involving the brain stem, basal ganglia and cerebellum with vertical gaze and pseudobulbar palsy, nuchal dystonia and dementia. Arch Neurol 10, 333–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, Goetz CG, Golbe LI, Grafman J, Growdon JH et al. (1996) Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (SteeleRichardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology 47, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hӧglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, Mollenhauer B, Müller U,Nilsson C, Whitwell JL et al. (2017) Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 32, 853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Ferguson LW, Rajput A, Chiu WZ, van Swieten JC, Troakes C, Al Sarraj S, Gelpi E et al. (2014) The phenotypic spectrum of progressive supranuclear palsy: a retrospective multicenter study of 100 definite cases. Mov Disord 29, 1758–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Josephs KA (2015) Key emerging issues in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol 262, 783–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickson D, Hauw J-J, Agid Y & Litvan I (2011) Progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration In Neurodegeneration (Weller D. D. a. R., ed), pp. 135–155. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clavaguera F, Akatsu H, Fraser G, Crowther RA, Frank S, Hench J, Probst A, Winkler DT, Reichwald J, Staufenbiel M et al. (2013) Brain homogenates from human tauopathies induce tau inclusions in mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 9535–9540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerson JE, Sengupta U, Lasagna-Reeves CA, Guerrero-Muñoz MJ, Troncoso J & Kayed R (2014) Characterization of tau oligomeric seeds in progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koga S, Parks A, Kasanuki K, Sanchez-Contreras M, Baker MC, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Uitti RJ, Graff-Radford N, van Gerpen JA et al. (2017) Cognitive impairment in progressive supranuclear palsy is associated with tau burden. Mov Disord 32, 1772–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pick A (1892) Über die Bejiehungen der senilen Hir natrophie zur Aphasie in, p. pp. 165–167 Prager. Med W ochenschr. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ, Disease WG & Disease, W. G. o. F. D. a. P. s. (2001) Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick’s Disease. Arch Neurol 58, 1803–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dickson DW (1998) Pick’s disease: a modern approach. Brain Pathol 8, 339–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark AW, Manz HJ, White CL, Lehmann J, Miller D & Coyle JT (1986) Cortical degeneration with swollen chromatolytic neurons: its relationship to Pick’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 45, 268–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heston LL & Mastri AR (1982) Age at onset of Pick’s and Alzheimer’s dementia: implications for diagnosis and research. J Gerontol 37, 422–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y & Mandelkow E (2016) Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ittner A, Ke YD, van Eersel J, Gladbach A, Gӧtz J & Ittner LM (2011) Brief update on different roles of tau in neurodegeneration. IUBMB Life 63, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ittner LM, Ke YD & Gotz J (2009) Phosphorylated Tau interacts with c-Jun N-terminal kinase-interacting protein 1 (JIP1) in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 284, 20909–20916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reynolds CH, Garwood CJ, Wray S, Price C, Kellie S, Perera T, Zvelebil M, Yang A, Sheppard PW, Varndell IM et al. (2008) Phosphorylation regulates tau interactions with Src homology 3 domains of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cgamma1, Grb2, and Src family kinases. J Biol Chem 283, 18177–18186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhaskar K, Yen SH & Lee G (2005) Disease-related modifications in tau affect the interaction between Fyn and Tau. J Biol Chem 280, 35119–35125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Cahill ME, Cryns VL, Reynolds MR, Berry RW & Binder LI (2006) Pseudophosphorylation of tau at serine 422 inhibits caspase cleavage: in vitro evidence and implications for tangle formation in vivo. J Neurochem 97, 1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickey CA, Kamal A, Lundgren K, Klosak N, Bailey RM, Dunmore J, Ash P, Shoraka S, Zlatkovic J, Eckman CB et al. (2007) The high-affinity HSP90-CHIP complex recognizes and selectively degrades phosphorylated tau client proteins. J Clin Invest 117, 648–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishiguro K, Omori A, Sato K, Tomizawa K, Imahori K & Uchida T (1991) A serine/threonine proline kinase activity is included in the tau protein kinase fraction forming a paired helical filament epitope. Neurosci Lett 128, 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishiguro K, Omori A, Takamatsu M, Sato K, Arioka M, Uchida T & Imahori K (1992) Phosphorylation sites on tau by tau protein kinase I, a bovine derived kinase generating an epitope of paired helical filaments. Neurosci Lett 148, 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arioka M, Tsukamoto M, Ishiguro K, Kato R, Sato K, Imahori K & Uchida T (1993) Tau protein kinase II is involved in the regulation of the normal phosphorylation state of tau protein. J Neurochem 60, 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takashima A, Noguchi K, Sato K, Hoshino T & Imahori K (1993) Tau protein kinase I is essential for amyloid beta-protein-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90, 7789–7793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato S, Cerny RL, Buescher JL & Ikezu T (2006) Tau- tubulin kinase 1 (TTBK1), a neuron-specific tau kinase candidate, is involved in tau phosphorylation and aggregation. J Neurochem 98, 1573–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi M, Tomizawa K, Sato K, Ohtake A & Omori A (1995) A novel tau-tubulin kinase from bovine brain. FEBS Lett 372, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomizawa K, Omori A, Ohtake A, Sato K & Takahashi M (2001) Tau-tubulin kinase phosphorylates tau at Ser-208 and Ser-210, sites found in paired helical filament-tau. FEBS Lett 492, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor LM, McMillan PJ, Liachko NF, Strovas TJ, Ghetti B, Bird TD, Dirk Keene C & Kraemer BC (2018) Pathological phosphorylation of tau and TDP-43 by TTBK1 and TTBK2 drives neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener 13, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernius J, Starkenberg A, Pokrzywa M & Thor S (2017) Human TTBK1, TTBK2 and MARK1 kinase toxicity in. Biol Open 6, 1013–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buratti E & Baralle FE (2008) Multiple roles of TDP-43 in gene expression, splicing regulation, and human disease. Front Biosci 13, 867–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bennion Callister J & Pickering-Brown SM (2014) Pathogenesis/genetics of frontotemporal dementia and how it relates to ALS. Exp Neurol 262 Pt B84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moisse K, Mepham J, Volkening K, Welch I, Hill T & Strong MJ (2009) Cytosolic TDP-43 expression following axotomy is associated with caspase 3 activation in NFL−/− mice: support for a role for TDP-43 in the physiological response to neuronal injury. Brain Res 1296, 176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu-Yesucevitz L, Bilgutay A, Zhang YJ, Vanderweyde T, Vanderwyde T, Citro A, Mehta T, Zaarur N, McKee A, Bowser R et al. (2010) Tar DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) associates with stress granules: analysis of cultured cells and pathological brain tissue. PLoS ONE 5, e13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rutherford NJ, Zhang YJ, Baker M, Gass JM, Finch NA, Xu YF, Stewart H, Kelley BJ, Kuntz K, Crook RJ et al. (2008) Novel mutations in TARDBP (TDP-43) in patients with familial amyotrophic lateralsclerosis. PLoS Genet 4, e1000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F et al. (2008) TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet 40, 572–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Deerlin VM, Leverenz JB, Bekris LM, Bird TD, Yuan W, Elman LB, Clay D, Wood EM, Chen-Plotkin AS, Martinez-Lage M et al. (2008) TARDBP mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with TDP-43 neuropathology: a genetic and histopathological analysis. Lancet Neurol 7, 409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zou ZY, Zhou ZR, Che CH, Liu CY, He RL & Huang HP (2017) Genetic epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88, 540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neumann M, Kwong LK, Lee EB, Kremmer E, Flatley A, Xu Y, Forman MS, Troost D, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ et al. (2009) Phosphorylation of S409/410 of TDP-43 is a consistent feature in all sporadic and familial forms of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Acta Neuropathol 117, 137–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McKee AC, Gavett BE, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, Kowall NW, Perl DP, Hedley-Whyte ET, Price B, Sullivan C et al. (2010) TDP-43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69, 918–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakashima-Yasuda H, Uryu K, Robinson J, Xie SX, Hurtig H, Duda JE, Arnold SE, Siderowf A, Grossman M, Leverenz JB et al. (2007) Co-morbidity of TDP-43 proteinopathy in Lewy body related diseases. Acta Neuropathol 114, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Higashi S, Iseki E, Yamamoto R, Minegishi M, Hino H, Fujisawa K, Togo T, Katsuse O, Uchikado H, Furukawa Y et al. (2007) Concurrence of TDP-43, tau and alpha-synuclein pathology in brains of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res 1184, 284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, Personett D, Davies P, Duara R, Graff-Radford NR, Hutton ML & Dickson DW (2007) TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 61, 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Uryu K, Nakashima-Yasuda H, Forman MS, Kwong LK, Clark CM, Grossman M, Miller BL, Kretzschmar HA, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ et al. (2008) Concomitant TAR-DNA-binding protein 43 pathology is present in Alzheimer disease and corticobasal degeneration but not in other tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 67, 555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fujishiro H, Uchikado H, Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, Yokota O, Tsuchiya K, Togo T, Iseki E & Hirayasu Y (2009) Accumulation of phosphorylated TDP-43 in brains of patients with argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 117, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zarei S, Carr K, Reiley L, Diaz K, Guerra O, Altamirano PF, Pagani W, Lodin D, Orozco G & Chinea A (2015) A comprehensive review of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Surg Neurol Int 6, 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan RH, Ke YD, Ittner LM & Halliday GM (2017) ALS/FTLD: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol 133, 177–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miller RG, Mitchell JD & Moore DH (2012) Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mora JS (2017) Edaravone for treatment of early-stage ALS. Lancet Neurol 16, 772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Strong MJ (2008) The syndromes of frontotemporal dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 9, 323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ringholz GM, Appel SH, Bradshaw M, Cooke NA, Mosnik DM & Schulz PE (2005) Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurology 65, 586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burrell JR, Kiernan MC, Vucic S & Hodges JR (2011) Motor neuron dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134, 2582–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J et al. (2011) Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simόn-Sánchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L et al. (2011) A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kraemer BC, Schuck T, Wheeler JM, Robinson LC, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM & Schellenberg GD (2010) Loss of murine TDP-43 disrupts motor function and plays an essential role in embryogenesis. Acta Neuropathol 119, 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sephton CF, Good SK, Atkin S, Dewey CM, Mayer P 3rd, Herz J & Yu G (2010) TDP-43 is a developmentally regulated protein essential for early embryonic development. J Biol Chem 285, 6826–6834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu LS, Cheng WC, Hou SC, Yan YT, Jiang ST & Shen CK (2010) TDP-43, a neuro-pathosignature factor, is essential for early mouse embryogenesis. Genesis 48, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee EB, Lee VM & Trojanowski JQ (2011) Gains or losses: molecular mechanisms of TDP43-mediated neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 38–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barmada SJ, Serio A, Arjun A, Bilican B, Daub A, Ando DM, Tsvetkov A, Pleiss M, Li X, Peisach D et al. (2014) Autophagy induction enhances TDP43 turnover and survival in neuronal ALS models. Nat Chem Biol 10, 677–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA & Schneider JA (2013) TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurol 70, 1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cohen TJ, Hwang AW, Restrepo CR, Yuan CX, Trojanowski JQ & Lee VM (2015) An acetylation switch controls TDP-43 function and aggregation propensity. Nat Commun 6, 5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seyfried NT, Gozal YM, Dammer EB, Xia Q, Duong DM, Cheng D, Lah JJ, Levey AI & Peng J (2010) Multiplex SILAC analysis of a cellular TDP-43 proteinopathy model reveals protein inclusions associated with SUMOylation and diverse polyubiquitin chains. Mol Cell Proteomics 9, 705–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM et al. (2006) Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, Ikeda K, Nonaka T, Mori H, Mann D, Tsuchiya K, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y et al. (2006) TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 351, 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hasegawa M, Arai T, Nonaka T, Kametani F, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Beach TG, Buratti E, Baralle F, Morita M et al. (2008) Phosphorylated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 64, 60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liachko NF, McMillan PJ, Guthrie CR, Bird TD, Leverenz JB & Kraemer BC (2013) CDC7 inhibition blocks pathological TDP-43 phosphorylation and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol 74, 39–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ayala YM, Zago P, D’Ambrogio A, Xu YF, Petrucelli L, Buratti E & Baralle FE (2008) Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J Cell Sci 121, 3778–3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang YJ, Gendron TF, Xu YF, Ko LW, Yen SH & Petrucelli L (2010) Phosphorylation regulates proteasomal-mediated degradation and solubility of TAR DNA binding protein-43 C-terminal fragments. Mol Neurodegener 5, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brady OA, Meng P, Zheng Y, Mao Y & Hu F (2011) Regulation of TDP-43 aggregation by phosphorylation and p62/SQSTM1. J Neurochem 116, 248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liachko NF, Guthrie CR & Kraemer BC (2010) Phosphorylation promotes neurotoxicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. J Neurosci 30, 16208–16219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liachko NF, McMillan PJ, Strovas TJ, Loomis E, Greenup L, Murrell JR, Ghetti B, Raskind MA, Montine TJ, Bird TD et al. (2014) The tau tubulin kinases TTBK1/2 promote accumulation of pathological TDP-43. PLoS Genet 10, e1004803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qi H, Yao C, Cai W, Girton J, Johansen KM & Johansen J (2009) Asator, a tau-tubulin kinase homolog in Drosophila localizes to the mitotic spindle. Dev Dyn 238, 3248–3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu J, Sato S, Okuyama S, Swan RJ, Jacobsen MT, Strunk E & Ikezu T (2010) Tau-tubulin kinase 1 enhances prefibrillar tau aggregation and motor neuron degeneration in P301L FTDP-17 tau-mutant mice. FASEB J 24, 2904–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Houlden H, Johnson J, Gardner-Thorpe C, Lashley T, Hernandez D, Worth P, Singleton AB, Hilton DA, Holton J, Revesz T et al. (2007) Mutations in TTBK2, encoding a kinase implicated in tau phosphorylation, segregate with spinocerebellar ataxia type 11. Nat Genet 39, 1434–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sato S, Xu J, Okuyama S, Martinez LB, Walsh SM, Jacobsen MT, Swan RJ, Schlautman JD, Ciborowski P & Ikezu T (2008) Spatial learning impairment, enhanced CDK5/p35 activity, and downregulation of NMDA receptor expression in transgenic mice expressing tau-tubulin kinase 1. J Neurosci 28, 14511–14521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ikezu S & Ikezu T (2014) Tau-tubulin kinase. Front Mol Neurosci 7, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xue Y, Wan PT, Hillertz P, Schweikart F, Zhao Y, Wissler L & Dekker N (2013) X-ray structural analysis of tau-tubulin kinase 1 and its interactions with small molecular inhibitors. ChemMedChem 8, 1846–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kiefer SE, Chang CJ, Kimura SR, Gao M, Xie D, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Gill MB, Mastalerz H, Thompson LA et al. (2014) The structure of human tau-tubulin kinase 1 both in the apo form and in complex with an inhibitor. Acta Cryst Sect F Struct Biol Communicat 70, 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liao JC, Yang TT, Weng RR, Kuo CT & Chang CW (2015) TTBK2: a tau protein kinase beyond tau phosphorylation. Biomed Res Int 2015, 575170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang N, Gordon SL, Fritsch MJ, Esoof N, Campbell DG, Gourlay R, Velupillai S, Macartney T, Peggie M, van Aalten DM et al. (2015) Phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle protein 2A at Thr84 by casein kinase 1 family kinases controls the specific retrieval of synaptotagmin-1. J Neurosci 35, 2492–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lund H, Cowburn RF, Gustafsson E, Strömberg K, Svensson A, Dahllund L, Malinowsky D & Sunnemark D (2013) Tau-tubulin kinase 1 expression, phosphorylation and co-localization with phosphoSer422 tau in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain Pathol 23, 378–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yu NN, Yu JT, Xiao JT, Zhang HW, Lu RC, Jiang H, Xing ZH & Tan L (2011) Tau-tubulin kinase-1 gene variants are associated with Alzheimer’s disease in Han Chinese. Neurosci Lett 491, 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vázquez-Higuera JL, Martínez-García A, S anchez-Juan P, Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, Mateo I, Pozueta A, Frank A, Valdivieso F, Berciano J, Bullido MJ et al. (2011) Genetic variations in tau-tubulin kinase-1 are linked to Alzheimer’s disease in a Spanish case-control cohort. Neurobiol Aging 32, 550.e5–550.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ambalavanan A, Girard SL, Ahn K, Zhou S, Dionne-Laporte A, Spiegelman D, Bourassa CV, Gauthier J, Hamdan FF, Xiong L et al. (2016) De novo variants in sporadic cases of childhood onset schizophrenia. Eur J Hum Genet 24, 944–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Asai H, Ikezu S, Woodbury ME, Yonemoto GM, Cui L & Ikezu T (2014) Accelerated neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in transgenic mice expressing P301L tau mutant and tau-tubulin kinase 1. Am J Pathol 184, 808–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Goetz SC, Liem KF & Anderson KV (2012) The spinocerebellar ataxia-associated gene Tau tubulin kinase 2 controls the initiation of ciliogenesis. Cell 151, 847–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bowie E, Norris R, Anderson KV & Goetz SC (2018) Spinocerebellar ataxia type 11-associated alleles of Ttbk2 dominantly interfere with ciliogenesis and cilium stability. PLoS Genet 14, e1007844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Oda T, Chiba S, Nagai T & Mizuno K (2014) Binding to Cep164, but not EB1, is essential for centriolar localization of TTBK2 and its function in ciliogenesis. Genes Cells 19, 927–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Watanabe T, Kakeno M, Matsui T, Sugiyama I, Arimura N, Matsuzawa K, Shirahige A, Ishidate F, Nishioka T, Taya S et al. (2015) TTBK2 with EB1/3 regulates microtubule dynamics in migrating cells through KIF2A phosphorylation. J Cell Biol 210, 737–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Čajánek L & Nigg EA (2014) Cep164 triggers ciliogenesis by recruiting Tau tubulin kinase 2 to the mother centriole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, E2841–E2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alesutan I, Sopjani M, Dermaku-Sopjani M, Munoz C, Voelkl J & Lang F (2012) Upregulation of Na-coupled glucose transporter SGLT1 by Tau tubulin kinase 2. Cell Physiol Biochem 30, 458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Almilaji A, Munoz C, Hosseinzadeh Z & Lang F (2013) Upregulation of Na+, Cl(−)-coupled betaine/γ- amino-butyric acid transporter BGT1 by Tau tubulin kinase 2. Cell Physiol Biochem 32, 334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bauer P, Stevanin G, Beetz C, Synofzik M, Schmitz-Hubsch T, Wullner U, Berthier E, Ollagnon-Roman E, Riess O, Forlani S et al. (2010) Spinocerebellar ataxia type 11 (SCA11) is an uncommon cause of dominant ataxia among French and German kindreds. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81, 1229–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lindquist SG, Moller LB, Dali CI, Marner L, Kamsteeg EJ, Nielsen JE & Hjermind LE (2017) A novel TTBK2 de novo mutation in a Danish family with early-onset spinocerebellar ataxia. Cerebellum 16, 268–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bouskila M, Esoof N, Gay L, Fang EH, Deak M, Begley MJ, Cantley LC, Prescott A, Storey KG & Alessi DR (2011) TTBK2 kinase substrate specificity and the impact of spinocerebellar-ataxia-causing mutations on expression, activity, localization and development. Biochem J 437, 157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Waters AM & Beales PL (2011) Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatr Nephrol 26, 1039–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bender C & Ullrich A (2012) PRKX, TTBK2 and RSK4 expression causes Sunitinib resistance in kidney carcinoma- and melanoma-cell lines. Int J Cancer 131, E45–E55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hasegawa M, Nonaka T & Masuda-Suzukake M (2017) Prion-like mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets in neurodegenerative disorders. Pharmacol Ther 172, 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cowan CM & Mudher A (2013) Are tau aggregates toxic or protective in tauopathies? Front Neurol 4, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Choksi DK, Roy B, Chatterjee S, Yusuff T, Bakhoum MF, Sengupta U, Ambegaokar S, Kayed R & Jackson GR (2014) TDP-43 Phosphorylation by casein kinase Ie promotes oligomerization and enhances toxicity in vivo. Hum Mol Genet 23, 1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]