Abstract

Purpose:

This study examines practitioner participation over 12 years in National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) studies and practitioner meetings, average length of participation, and association between practitioner- and practice-level characteristics and participation. Little information exists about practitioners’ long-term participation in PBRNs.

Methods:

The network conducted a retrospective analysis of practitioner participation in three main network activities during 2005–2017. Practitioners who completed an enrollment questionnaire, practiced in the U.S., and either attended a network meeting or received an invitation to complete a questionnaire or clinical study were included in the analysis. 3,669 practitioners met inclusion criteria. The network implemented 38 studies (28 clinical and 10 questionnaire), 23 of which (15 clinical and 8 questionnaire) met the criteria for the current analysis.

Results:

Overall, 86% (N=3,148) participated in at least one network activity during 2005–2017. Questionnaire studies had the highest rate with 81% (N=2,963) completing at least one, 21% (N=762) completed at least 1 clinical study and 19% (N=700) attended at least one network meeting. Among 1,578 practitioners enrolled in the first five years of the Network launch, 20% (N=320) participated in multiple network activities over 5–9 years, and 14% (N= 238) for 10–12 years. Practitioner characteristics associated with participation varied depending on the activity assessed.

Conclusion:

The network engaged practitioners in its research activities with relatively high participation rates over a 12-year period. Strategies employed by the network to engage practitioners may serve as a model for PBRN networks for other allied health professions.

Keywords: Allied Health Personnel, Health Occupations, Retrospective Studies, Surveys and Questionnaires

Introduction

Although medical practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States began in the 1970s, to our knowledge no dental PBRN existed in the United States before 20021,2. To catalyze the development of dental PBRNs, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), part of the National Institutes of Health, funded three regional dental PBRNs in 2005 for a seven-year period. By the end of their funding period in 2012, the regional PBRNs had conducted numerous studies with thousands of patients and hundreds of practitioners. Studies investigated numerous topics using a broad range of study designs; demonstrated rigor and impact on clinical practice; and demonstrated that dental practitioners could effectively contribute to every step of the research process1,3–5. Owing to the success of the regional PBRNs, NIDCR funded the PBRN initiative for an additional seven-year period, as a single, unified national network6called the “National Dental PBRN.” Six regional administrative sites facilitate the National Dental PBRN’s ability to conduct studies with practitioners in all 50 states, with almost 7,000 members currently enrolled nationwide.

The Network’s mission is “to improve oral health by conducting dental practice-based research and by serving dental professionals through education and collegiality6”. It accomplishes this mission by including practitioners in various steps of the study process. These include study idea generation, development of study design and data collection forms, study piloting and implementation, data interpretation, presentation, and publication of study results. All activities occur with an eye toward answering questions of daily clinical relevance that have the potential to improve clinical practice and positively impact patients’ oral health. To increase the generalizability of network studies in the dental field, most studies include participation from both general dentists and specialists from a variety of practice types (i.e., private, community, academic).

As the network grew, studies evolved from simple short-term questionnaire studies to more complex long-term clinical observational and randomized studies. Successful implementation of these studies required the participation of a diverse spectrum of dental practitioners and specialists, which reflected the practitioner population at large. Annual meetings of practitioners in each region are another major participation activity available to network practitioners. These meetings provide face-to-face opportunities to interact with colleagues, hear the latest results from network studies, help design future studies, and obtain Continuing Education credit7. Meetings allow for professional networking, which is desired by PBRN participants, but has been described as difficult to achieve8.

In both medical and dental PBRNs, strong member participation is essential, even though practitioners may face increasing time pressures and decreasing autonomy. The participatory engagement of clinicians in research has been a hallmark of PBRNs, leading to high levels of member investment and better translation of research into practice9,10. The strength of PBRN research lies in its ability to conduct clinician-led “bottom-up” studies, in which the study ideas of network members are developed and implemented with the support of PBRN leaders and staff.

Although there are many benefits to a national network, there are also challenges and limitations encountered from conducting multi-site research studies11. Past literature from medical PBRNs has highlighted the facilitators, barriers and solutions to initial participation in PBRNs12–16. Previously cited barriers to PBRN study participation include lack of time and competing demands, inadequate training and insufficient compensation and institutional regulatory requirements11–17. However, little information exists about practitioners’ participation in multiple studies, long-term retention and participation in national PBRN networks.

The purpose of this study was to describe: (1) overall National Dental PBRN practitioner participation across three main network activities (questionnaire studies, clinical studies and network meetings); (2) length of practitioner enrollment; and (3) the association of practitioner demographic and practice-related variables with practitioner participation in each activity assessed and length of time in the network.

Long-term PBRN participation data are necessary to demonstrate the value of this research context to the practitioners it aspires to affect, and in turn to show that this type of research is sustainable and worthy of future funding.

Methods

The network conducted a retrospective analysis of practitioner participation in network studies and attendance at annual meetings from 2005 −2017. We included the 3,669 practitioners who: (1) completed a network enrollment questionnaire; (2) practiced in the U.S.; (3) were dentists; and (4) who met one or more of these three criteria: (a) were eligible (invited) to complete a questionnaire study, (b) participated in a clinical study or (3) attended a network meeting. All network members are eligible to attend their region’s respective meeting. Non-members that attended regional meetings are not included in the present analysis. The only specified eligibility criterion for attending network meetings was network membership in the region hosting the meeting. As the focus of this paper is on participation, and network meeting attendance is a distinct way of participating, meeting attendance is included as both an eligibility criterion and participation measure.

Table 1provides a descriptive list of studies that the network has conducted and those included in the present analysis according to the phase of the network in which the study was conducted. The network had 2 phases. Phase 1 was during 2005–2012 and covered Minnesota (included Health Partners of Minnesota), Permanente Dental Associates (PDA) in Oregon, and the South Central and South Atlantic regions of the United States. Phase 2 is from 2012–2017, and covers the entire United States. In addition, as the network grew in Phase 2, it tracked different information not tracked in Phase 1, specifically invitations to participate in each study, allowing for calculations of participation rates among those invited.

Table 1.

Summary of 38 network studies1 to date

| Study # | Study title | Study design (Qx: Questionnaire) |

# of practitioners |

# of patients/ other entities |

Study type(s) |

Classify as… |

Included in present report |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 studies (2007–2012, network not nationwide) | |||||||||||||

| Included in present report | - | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Assessment of caries diagnosis and treatment | Paper Qx to dentists | 494 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 4 | Reasons for placing the first restoration on permanent tooth surfaces | Cross-sectional; consecutive patients | 192 | 4,844 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 5 | Reasons for replacement or repair of dental restorations | Cross-sectional; consecutive patients | 157 | 6,092 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 6 | CONDOR case-control study of ONJ | Case-control study | 81 | 764 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 8 | Longitudinal study of dental restorations placed on previously un-restored surfaces | Prospective cohort study | 192 | 4,844 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes as FU | ||||||

| 9 | Longitudinal study of repaired or replaced dental restorations | Prospective cohort study | 157 | 6,092 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes as FU | ||||||

| 10 | Development of a patient-based provider intervention for early caries management | Cross-sectional; clinical data collection and Qx | 10 | 336 patients | Qx and Clinical | Clinical | Clinical only | ||||||

| 12 | Prevalence of questionable occlusal caries lesions | Cross-sectional | 58 | 4,478 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 13 | Longitudinal study of questionable occlusal caries lesions | Prospective cohort study | 58 | 4,478 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes as FU | ||||||

| 15 | Blood glucose testing in dental practice | Cross-sectional | 23 | 387 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 16a | Assessing the impact of participation in PBRNs on patient care | Paper Qx with dentists and dental hygienists | 613 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 16b | Assessing the impact of participation in PBRNs on patient care - repeated 2 years | Paper Qx with dentists and dental hygienists | 556 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 17 | Peri-operative pain and root canal therapy | 1-week prospective cohort study | 55 | 655 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 20 | Primary care management of TMJD | Electronic Qx with dentists | 434 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 21 | Infrastructure update survey | Electronic Qx with dentists | 649 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| Excluded from present report | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Dental tobacco control RCT | Randomized clinical trial | 190 | 11,898 patients | Qx and Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 2 | Practice-based root canal treatment effectiveness | Retrospective cohort study | 13 | 84 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 7 | Retrospective cohort study of ONJ | Retrospective cohort study using electronic data | -- | 572,606 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 11 | Patient satisfaction with dental restorations | Cross-sectional | 159 | 4,680 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 14 | Hygienists’ internet tobacco cessation RCT | Randomized clinical trial | 100 | 1,814 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 18 | Persistent pain and root canal therapy | Prospective cohort study | 55 | 655 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 19 | Diagnoses for persistent dentoalveolar pain following root canal therapy | Nested case series study | 63 | 354 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| Phase 2 studies (2013–2017, network was nationwide) | |||||||||||||

| Included in present report | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| 22 | Isolation techniques used when performing root canal treatment | Electronic and paper Qx with dentists | 1,491 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 23 | Management of suspicious occlusal caries lesions | Randomized clinical trial | 125 | 3,093 patients | Qx; Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 24 | Management of dentin hypersensitivity (2 parts) | #1: electronic Qx with dentists | 200 | 1,876 patients | Qx; Clinical | Clinical | Clinical only | ||||||

| #2: prospective cohort study | |||||||||||||

| 25 | Reducing prescription opioid misuse | Electronic Qx with dentists | 822 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 28 | Factors for Successful Crowns Stage 1 | Electronic Qx with dentists | 1,852 | -- | Qx | Qx | Yes | ||||||

| 29 | Factors for Successful Crowns Stage 2 | Prospective cohort study | 207 | 3,847 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Yes | ||||||

| 32 | Cracked tooth registry study | Prospective cohort study | 236 | 3,017 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Baseline only | ||||||

| 34 | Anterior open-bite treatment | Prospective cohort study | 96 | 358 patients | Clinical | Clinical | Baseline only | ||||||

| Excluded from present report | |||||||||||||

| 26 | Understanding dental information networks | Electronic Qx with dentists | 1,860 | -- | Qx | Qx | No | ||||||

| 27 | Quit Advisor DDS smoking cessation study | Feasibility non-randomized controlled clinical trial | 30 | 248 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 30 | Leveraging EDR data for clinical research | EDR extraction of patients who received root canal treatment and select restorations | 99 | 1207155 procedures | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 31 | Common practices of head & neck examinations in U.S. dental offices | Electronic and paper Qx with dentists | 1,126 | -- | Qx | Qx | No | ||||||

| 33 | Risk for oral cancer/HPV study | Prospective cohort study | 37 | 1,025 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 35 | Predicting root canal treatment outcomes | Prospective cohort study | 172 | 1,883 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 36 | TMD treatment methods | Prospective cohort study | 198 | 1,576 patients | Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 37 | Multi-risk assessment in the dental office | 3 parts planned, Qx, cohort, then telephone interviews with insurance executives | Planned | 810 patients; 20 dental insurance executives | Qx, Clinical | Clinical | No | ||||||

| 38 | Prophylactic use of antibiotics in dental office | Electronic and paper Qx with dentists | 2,500 (planned) | -- | Qx | Qx | No | ||||||

Study number refers to order in which study was implemented

Detailed study information can be accessed at http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/studies.php

Study inclusion criteria:

A questionnaire study (practitioner respondents only) or a clinical study ( enrolled patients or collected patient data).

Baseline data collection completed as of December 31, 2017.

Network membership and completion of the enrollment questionnaire were requirements for the study.

To be eligible for follow-up analysis, clinic visits a year after the baseline visit must be required.

Twenty-three (15 clinical and 8 questionnaire) of 38 (28 clinical and 10 questionnaire) network studies were included. Of the 15 clinical studies included, 10 were in phase 1, of which 3 (studies 8, 9, and 13) were included only in analyses assessing retention of patients for yearly follow-up visits (they were not counted as separate studies in this report); 5 clinical studies were from phase 2. Of the 8 questionnaire studies, 5 were from phase 1 and were from phase 2. The network administered questionnaire study 16 twice in phase 1, two years apart; they are counted as separate studies in this report.

Study exclusion criteria:

Did not require network membership to participate: Studies 1 and 14 (Study 1 was part of network development, started in 2001, and study 14 involved primarily hygienists rather than dentists).

Required participation in another study: Study 11 was not included because it was among participants in study 5 and did not entail clinic visits (apart from those in study 5 already included in the present analysis). Similarly, study 18 was not included because it was a short-term follow-up of study 17, not requiring patient return visits (only telephone follow-up).

Required dental record abstractions only: Studies 2, 7, and 19.

Baseline data collection not complete as of December 31, 2017: This includes 9 studies, numbers 26 through 38.

Questionnaire study completion, clinical study participation and network meeting attendance were obtained from practitioner databases and study databases. The practitioner database provided information on study invitations (questionnaires and clinical studies) for studies conducted after 2012 in phase 2. Among practitioners who participated in a follow-up study, i.e., those who recalled at least one patient in a one-year follow-up visit, we report the proportion of patients followed for at least one year. Network databases also provided the following variables: date of first and last patient enrollment in a clinical study and number of patients enrolled per study. A network enrollment questionnaire (required for network membership) provided practitioner characteristics (gender, race, year graduated dental school, type of study practice and region). Network clinical studies typically record demographic characteristics of the patients enrolled, including the postal ZIP code of residence, thereby allowing for geographical mapping.

Analysis.

The numbers of practitioners who participated in a clinical study, in a questionnaire study, and who had attended a network meeting were all calculated. The participation rates for questionnaire studies and clinical studies, namely, the proportion of invited practitioners who completed a questionnaire study or enrolled a patient, respectively, were calculated for studies conducted after 2012. For practitioners who participated in a clinical study, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation [SD]) for number of patients enrolled and length of time (number of days) spent enrolling them were calculated. The associations among the number of clinical studies participated in, the number of questionnaire studies completed, and the number of meetings attended were assessed using Spearman rank correlations. For time in the network, median and interquartile [IQR] range were calculated due to skewed data.

The practitioner characteristics listed above are described. There were four outcome variables of interest: 1) participation in a clinical study, 2) participation in a questionnaire study, 3) attendance at a network meeting, or network membership for ten or more years. For each outcome of interest, the frequency of practitioner characteristics was obtained and chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used as appropriate to assess the significance of the differences. To identify independent associations, logistic regression was used with an entry criterion of p<0.10 and a retention criterion of p<0.05. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from the models. Some categories were collapsed based on bivariate analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS v9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

Results:

Overall activities

Overall, 3,669 practitioners met inclusion criteria, of whom 86% (N=3,148) participated in at least one network activity (clinical study, questionnaire study or network meeting). Questionnaire studies had the highest participation rate among practitioners with 81% (N=2,963) completing at least one; 21% (N=762) completed at least one clinical study and 19% (N=700) attended at least one network meeting. In phase 1, 833 practitioners participated in questionnaire studies and 306 in clinical studies. In phase 2, 2,453 participated in questionnaire studies and 544 in clinical studies. These results are not mutually exclusive, as some practitioners participated in specified activities in both. The larger number of participants for both types of studies in phase 2 as compared to phase 1 reflects the growth of the network, which became national in phase 2 and expanded to include practitioners from the Northeast and Southwest US.

Participation rates

The average participation rate for questionnaire studies (percent of invited who completed) was 75% (ranged from 58% to 87%), and the average participation rate for clinical studies (percent of invited who enrolled a patient) was 86% (ranged from 74% to 97%).

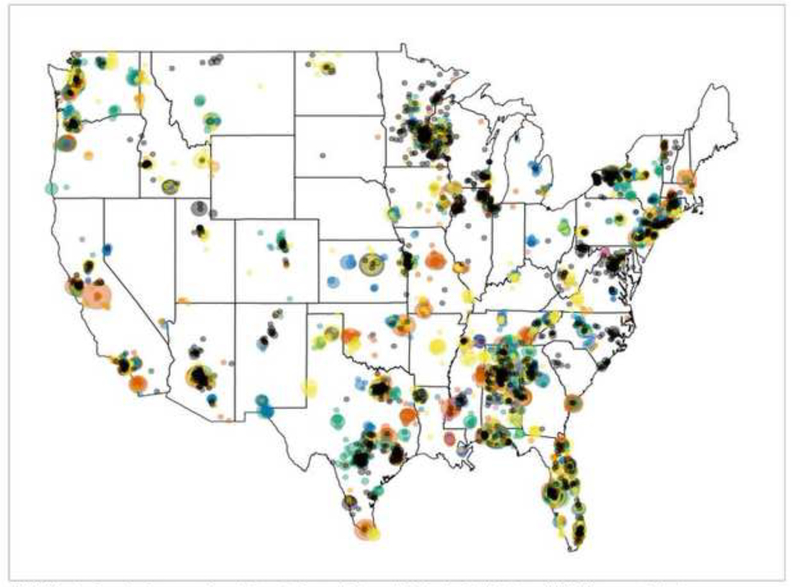

Practitioners who participated in one or more of eight recent clinical studies successfully enrolled patients from a broad geographic coverage (Figure 1). Protocol training was conducted by network Regional Coordinators using either in-office training or via remote means (webinar, conference call), thereby allowing for enrollment of practices at distances far from the network’s regional administrative sites.

Figure 1.

Distribution of 15,462 patients enrolled in 8 Network studies

1(AOB) Anterior Open-Bite Treatment; (Crown) Factors for Successful Crowns; (CTR) Cracked Tooth Registry; (MDH) Management of Dentin Hypersenstivity; (Predict) Predicting Outcomes of Root Canal Treatment; (QADDS) Quit Advisor DDS Smoking Cessation; (SOCL) Decision Aids for Suspicious Occlusal Caries Lesions; (TMD) Management of Painful Temporomandibular Disorder

215 AOB patients in Puerto Rico, 10 CTR patients in Alaska

Clinical studies

Among the 762 practitioners who participated in at least one clinical study, the mean (SD) number of patients enrolled per study was 17 (10), with a range from 4 to 38; for phase 1 (n=255), the mean (SD) was 26 (11) and for phase 2 (n=544), the mean (SD) was 13 (7). The mean (SD) number of days spent enrolling patients per study was 94 (68), with a range from 36 to 140 days; for phase 1 the mean (SD) was 82 (46) and for phase 2 the mean (SD) was 85 (71) days. In studies where there was a yearly follow-up component, the proportion of practitioners with 1-year follow-up ranged from 31% to 80%. All studies with follow-up were in phase 1. For study 4, 153 (80%) of 192 practitioners recalled at least one patient for follow-up, and the mean (SD) number of patients enrolled was 27 (10), with a mean (SD) of 15 (7) retained at 1-year; Study 5, 91 (58%) of 157 had follow-up, mean (SD) number of patients enrolled was 38 (12) with a mean (SD) of 28 (10) retained at 1-year; Study 12, 18 (31%) of 58 had follow-up, the mean (SD) number of patients enrolled was 20 (12) with mean (SD) of 17 (10) retained at 1-year.

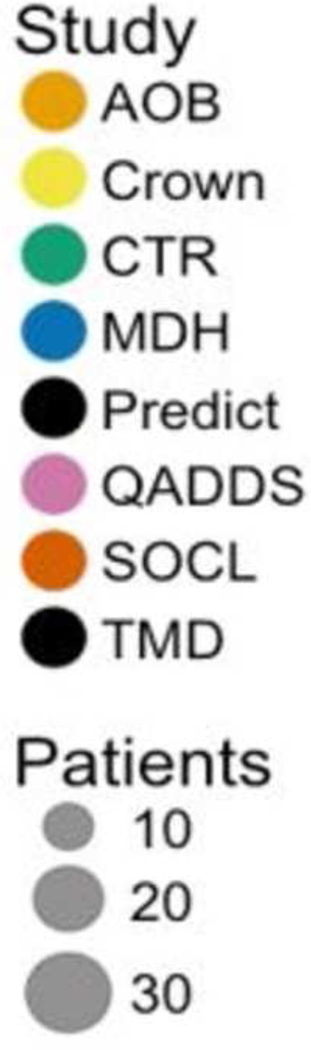

Among the 3,148 practitioners who participated in at least one network activity, 71% participated in one, 18% in two and 11% in all three types of activities. Number of each type of activity participated in was as follows: among the 762 who participated in at least one clinical study, 61% participated in one, 20% in two, 12% in three, and 8% in more than three; among the 2,963 who completed at least one questionnaire study, 40% completed one, 34% two, 12% three, and 14% more than three; and among the 700 who attended a network meeting, 46% attended one, 21% two, 13% three and 20% more than three (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of participants according to the number of types activities, and number of each type of activity, they participated in among those who participated in any.

There were weak to moderate Spearman’s rank correlations among the number of each activity completed, participated, or attended: number of clinical studies participated in and number of questionnaire studies completed, r=0.17, P<0.001; number of questionnaire studies completed and number of meetings attended, r=0.22, P<0.001; and number of clinical studies participated in and number of meetings attended, r=0.44, P<0.001.

Time in network

Time in the network was estimated for 3,444 (94%) members; 225 who enrolled used paper forms and had the enrollment date missing. The mean years in the network (SD) was 5.1 (2.4), with median (IQR) of 4.0 (4–5), and range of 1–12 years. Among the 3,148 members who participated in at least one of the activities assessed in this analysis, time in the network was estimated for 2,958 (94%). The mean years in the network for these practitioners (SD) was 5.6 (2.5), with median (IQR) of 4.0 (4–6), and range of 1–12 years.

Practitioner characteristics

Overall, 73% (N=2,466) were male, the majority (80%) were non-Hispanic white, and were in private practice (80%). Of note, 317 (9%) were in more than one type of practice during their time in the network. The median (IQR) year graduated from dental school was 1988 (1980–2000), with a range from 1954 to 2014. As shown in Figure 1, practitioners were located across a broad national geographic range, as judged by the residence locations of the patients whom they enrolled in clinical studies.

Practitioner characteristics and network activity

Several practitioner characteristics were associated with network activity, but not in a consistent manner (Table 2).

Table 2.

Practitioner characteristics overall and according to whether they participated in activities assessed.

| All | Any clinical study |

Any questionnaire study |

Any meeting |

In network 10+ years |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 (n=3,669) |

% (col2%) |

N1

(n=762) |

% (row3%) |

N1

(n=2,963) |

% (row3%) |

N1

(n=700) |

% (row3%) |

N1

(n=297) |

% (row3%) |

|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 2,466 | 73% | 490 | 20% | 2,040 | 83% | 501 | 20% | 235 | 10% |

| Female | 891 | 27% | 192 | 22% | 710 | 80% | 183 | 21% | 60 | 7% |

| p4 = 0.3 | p = 0.04 | p = 0.9 | p = 0.01 | |||||||

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | 2,740 | 80% | 540 | 20% | 2,284 | 83% | 499 | 18% | 254 | 9% |

| Black | 146 | 4% | 34 | 23% | 121 | 83% | 44 | 30% | 16 | 11% |

| Asian | 323 | 9% | 78 | 24% | 255 | 79% | 83 | 26% | 14 | 4% |

| Hispanic | 191 | 6% | 31 | 16% | 141 | 74% | 46 | 24% | 5 | 3% |

| Other/multi5 | 34 | 1% | 14 | 41% | 30 | 88% | 12 | 35% | 6 | 18% |

| p = 0.004 | p = 0.005 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Year graduated dental school | ||||||||||

| Before 1980 | 793 | 23% | 139 | 18% | 673 | 85% | 163 | 21% | 77 | 10% |

| 1980–89 | 1,057 | 31% | 237 | 22% | 888 | 84% | 233 | 22% | 103 | 10% |

| 1990–99 | 717 | 21% | 143 | 20% | 556 | 78% | 154 | 21% | 80 | 11% |

| 2000+ | 891 | 26% | 181 | 20% | 731 | 82% | 136 | 15% | 36 | 4% |

| p = 0.08 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Practice type | ||||||||||

| Private | 2,741 | 80% | 491 | 18% | 2,236 | 82% | 441 | 16% | 165 | 6% |

| HP/PDA6 | 120 | 3% | 21 | 18% | 114 | 95% | 28 | 23% | 2 | 2% |

| Public | 128 | 4% | 9 | 7% | 113 | 88% | 22 | 17% | 0 | 0% |

| Academic | 131 | 4% | 13 | 10% | 79 | 60% | 39 | 30% | 1 | 1% |

| Other/changed | 317 | 9% | 157 | 50% | 287 | 91% | 150 | 47% | 129 | 41% |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Region | ||||||||||

| Western | 469 | 13% | 157 | 33% | 381 | 81% | 137 | 29% | 34 | 7% |

| Midwest | 343 | 10% | 111 | 32% | 272 | 79% | 115 | 34% | 36 | 10% |

| Southwest | 616 | 18% | 117 | 19% | 475 | 77% | 73 | 12% | 0 | 0% |

| South Central | 884 | 25% | 156 | 18% | 785 | 89% | 176 | 20% | 176 | 20% |

| South Atlantic | 533 | 15% | 97 | 18% | 464 | 87% | 99 | 19% | 51 | 10% |

| Northeast | 636 | 18% | 67 | 11% | 488 | 77% | 89 | 14% | 0 | 0% |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||

Numbers not summing to total N in column heading due to missing data.

Column (overall) percent. Excludes missing; column percents not summing to 100 within each practitioner/practice characteristic is due to rounding.

Percent of row characteristic that has column characteristic, e.g., percent of male practitioners who participated in a clinical study.

P-value from chi-square test or Fisher exact test for difference in proportions.

Of the 34 Other/multi-race: 14 multi, 9 American Indian/Alaskan, 7 Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 4 different race each cycle.

Practices in the Health Partners Dental Group (Minnesota) or the Permanente Dental Associates (Oregon).

Clinical studies:

Practitioners who graduated prior to 1980 (most experienced) participated in clinical studies less frequently than those who graduated 1980 or later (18% vs. 21%, p=0.03). These associations remained independently significant in a logistic regression model (multi-other race: OR=2.6, 95% CI: 1.2–5.3, p=0.01; changed practice type: OR=4.8, 95% CI: 3.8–6.1, p<0.001; graduated before 1980: OR=0.8, 95% CI: 0.6–1.0, p=0.05). Gender was not associated with participating in a clinical study. The 1% of practitioners who were multi-racial, or of American Indian or Hawaiian/Pacific Islander race, participated in clinical studies at a much higher rate than any other race/ethnic group (41% vs. 20%, p=0.002).

Questionnaire studies:

Male dentists (83% vs. 80%, p=0.04) and those who graduated dental school before 1990 (84% vs. 80%, p<0.001) completed questionnaire studies at higher rates than their counterparts, while those who practiced in an academic setting completed questionnaire studies at lower rates than those practicing in other settings (60% vs. 83%, p<0.001). Completion rates differed by race of practitioners (highest for multi-other race [88%], and lowest for Hispanics [74%] and Asians [79%], and intermediate for whites and African-Americans [both 83%]; p=0.005). Only graduating dental school before 1990 (OR=1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5, p=0.01) and practicing in academic settings (OR=0.3, 95% CI: 0.2–0.4, p<0.001) were independently associated with completing a survey.

Meeting attendance:

Non-Hispanic whites (18% vs. 27%, p<0.001) and those who graduated dental school 2000 or later (15% vs. 21%, p<0.001) were less likely to attend network practitioner meetings. These associations remained independently significant in a logistic regression model (non-Hispanic white race: OR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.4–0.7, p<0.001; changed practice type: OR=4.4, 95% CI: 3.5–5.6, p<0.001; graduated 2000 or later: OR=0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.7, p<0.001).

Network membership >10 years:

Male dentists (10% vs. 7%, p=0.01) were more likely to be in the network for 10 or more years than their counterparts, while those who graduated from dental school 2000 or later were less likely to (4% vs. 10%, p<0.001). Long-term participation differed by race, and was highest for multi-other race [18%], lowest for Hispanics [3%] and Asians [4%], and intermediate for Whites [9%] and African-Americans [11%]. (p<0.001). All but the gender association remained independently associated with long-term network activity (changed practice: OR=15.8, 95% CI: 11.7–1.2, p<0.001; graduated 2000 or later: OR=0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.5, p<0.001; race-ethnicity: p<0.001).

In summary, only two practitioner characteristics were consistently associated with network participation, and both of these groups only comprised a small number of practitioners. A higher proportion of the 1% (N=34) of practitioners who were either multi-racial or of Hawaiian or American Indian race participated in each of the activities assessed than did any other race. Similarly, higher proportions of practitioners who had changed their practice setting type (e.g., from private to academic) participated in clinical studies, attended network meetings and were in the network for 10 or more years than did their counterparts.

Discussion

Although there are over 183 active PBRNs in the United States18, to our knowledge this is one of the first examinations of practitioner participation rates, average duration of participation and characteristics associated with long-term participation in a national network. Our results indicate that the National Dental PBRN has been successful at engaging and retaining member practitioners in clinical and non-clinical research activities over a period of 12 years, with 86% participating in at least one network activity (study or meeting) after enrollment in the network. The National Dental PBRN utilized best practices and team-based research described by primary care PBRNs to develop regional infrastructure, and support systems that may promote increased practitioner participation by reducing administrative and logistical burdens19–23.

The network has employed and adapted strategies that other PBRNs have found effective at engaging and retaining practitioners including: selecting feasible studies, minimizing overlap of study participation, providing training materials adapted to clinical practice and having the research team available for practitioner queries throughout participation11.

The network also provides both in-person and remote support for practitioners participating in studies, allowing for geographically diverse participation and real-time assistance. When implementing clinical studies, care is taken in the design not to impede office flow, and typically to enroll over a short time interval, namely, 2–4 months. Practitioners in this analysis enrolled an average of 17 patients per study during a mean enrollment period of 94 days. The network launches studies regularly, allowing practitioners to choose opportunities that best suit their clinical interests, patient population and current workload.

The National Dental PBRN has taken steps to address the previously cited participation barriers of competing demands for time, inadequate training and insufficient compensation by utilizing strategies frequently employed by primary care PBRNs11,15,17,22. Study protocol trainings typically take less than one hour and one-page quick reference guides are provided to practitioners before their training sessions. Case report forms take less than 10 minutes to complete on average and practitioners are encouraged to have at least one staff member trained on the study protocol in order to assist with administrative tasks. Recent National Dental PBRN studies utilize electronic data capture on tablets, thereby reducing the amount of administrative time needed to conduct the study. The network offers Continuing Education credit to practitioners and hygienists for completing a Human Subjects Protection Training and the study protocol training, increasing the incentive to participate.

Team science research is critically important to addressing complex research questions and is necessary to accelerate adoption, implementation, and sustainability of clinical practice improvement21. A key operating principle for the network, one aimed at encouraging long-term participation, is that most study topics originate from clinical questions that practitioners themselves contribute, and that the resulting answers have the potential to immediately improve clinical practice1. Additionally, no study is done in the network unless it receives approval from the network’s Executive Committee, the majority voting authority is comprised of practitioners in private or community clinical practice. Gibson et al. found that members of a physician PBRN cited the opportunity to enact quality improvement, contribute to clinical knowledge and attain intellectual stimulation as the most positive aspects of PBRN participation13. Keeping these aspects in mind, the National Dental PBRN has prioritized participation of practitioners throughout study design, implementation and dissemination. The network disseminates study results to practitioners as soon as they are available, and makes a point of providing opportunities for practitioners to serve on protocol development groups, to discuss results with colleagues at network meetings, and to present results at local study clubs or organizations as well as national and international venues25. Practitioners participating in National Dental PBRN studies cite an increase in their practice’s visibility, professional stimulation, networking, and stature among patients as benefits to participating in the network6.

Although most of the approaches used by the network are not novel, they reflect best practices adopted from other PBRN’s, representing their application to a new professional field and their potential application to other health fields. Although over 180 PBRNs exist, few have operated on a national scale for over 10 years and little data exist to demonstrate long-term participation and network longevity. Studies implemented in the dental network that involve the participation of medical practitioners or study topics that have wide applicability to medicine (e.g., blood glucose testing, screening for human papilloma virus, opioid prescribing practices and smoking cessation) exemplify an overlap between dental and medical assessments.

This analysis does have limitations. First, several studies are still in active data collection and were not included. Inclusion of these studies would likely increase practitioner participation rates as they include network members who had not previously participated in other activities. Second, although network members are encouraged and reminded to electronically update their enrollment questionnaire if their practice characteristics change, some information the network has may not be current. However, the data available provide a representative assessment of practitioner participation in the National Dental PRBN from 2005–2017. Third, we used attendance at a network meeting as a measure of both eligibility and participation. We acknowledge that limits inferences about the proportion of network members participating in specific activities. We describe participation over two distinct phases of the dental network; 2005–2011 and 2012–2017. The latter reflects when the network covered the entire United States. This growth has enabled the network to conduct studies with more practitioners, and fewer patients per practitioner, which lessens impact on the practice due to participating in a study.

PBRNs often have to explain whether results from their studies are generalizable to practices at large. National Dental PBRN members are not recruited randomly, so unmeasured factors that are presumably associated with network membership, such as interest in clinical research, may make network clinicians unrepresentative of clinicians at large. However, analyses have demonstrated that network practitioners have much in common with the profession at large, albeit with some differences in characteristics while also providing substantial diversity in these characteristics1,26. This assertion is warranted because substantial percentages of network dentists are represented in the various response categories of the characteristics in the Enrollment Questionnaire; findings from several network studies document that network dentists report patterns of diagnosis and treatment that are similar to patterns determined from non-network dentists26–32; and the similarity of network dentists to non-network dentists using the ADA Survey of Dental Practice33.

Conclusion:

Practice-based research is a promising venue for advancing clinical practice by incorporating practitioners in the research process, engaging them in collegial activities and studying relevant questions and obtaining large amounts of patient data in a relatively short period of time. However, engaging community practitioners in research studies can be challenging due to competing demands for time and lack of research training and experience. The National Dental PBRN has developed an infrastructure to support practitioners nationwide in dental research. Results indicate that the National Dental PBRN has achieved high rates of sustained participation among enrolled members and provides a venue to obtain data from diverse populations. The network’s infrastructure may serve as a model to other PBRNs looking to increase participation rates and expand their reach from a regional level to a national level.

Acknowledgements:

We are very grateful to the practitioners who have participated in the network and the Regional Coordinators who have coordinated studies and created successful member relations.

Funding Statement:This work was supported by NIH grant U19-DE-22516. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health. An Internet site devoted to details about the nation’s network is located at http://NationalDentalPBRN.org.

Footnotes

Conflicting and Competing Interests:The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin P, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ. Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from “The Dental PBRN”. Gen Dent.2009;57(3):270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearce KA, Love MM, Barron MA, Matheny SC, Mahfoud Z. How and why to study the practice content of a practice-based research network. Ann Fam Med.2004;2(5):425–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, et al. The creation and development of the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc.2008;139(1):74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert GH, Richman JS, Gordan VV, et al. Lessons learned during the conduct of clinical studies in the dental PBRN. J Dent Educ.2011;75(4):453–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rindal DB, Flottemesch TJ, Durand EU, et al. Practice change toward better adherence to evidence-based treatment of early dental decay in the National Dental PBRN. Implement Sci.2014;9:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent.2013;41(11):1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert GH, Richman JS, Qvist V, et al. Change in stated clinical practice associated with participation in the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent.2010;58(6):520–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel P, Hemmeger H, Kozak MA, Gernant SA, Snyder ME. Community pharmacist participation in a practice-based research network: a report from the Medication Safety Research Network of Indiana (Rx-SafeNet). J Am Pharm Assoc.2015;55(6):649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werner JJ. Measuring the impact of practice-based research networks (PBRNs). J Am Board Fam Med.2012;25(5):557–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas P, Griffiths F, Kai J, O’dwyer A. Networks for research in primary health care. BMJ.2001;322(7286):588–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham DG, Spano MS, Stewart TV, Staton EW, Meers A, Pace WD. Strategies for planning and launching PBRN research studies: a project of the Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network (AAFP NRN). J Am Board Fam Med.2007;20(2):220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagnan LJ, Handley MA, Rollins N, Mold J. Voices from left of the dial: reflections of practice-based researchers. J Am Board Fam Med.2010;23(4):442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson K, Szilagyi P, Swanger CM, et al. Physician perspectives on incentives to participate in practice-based research: a greater rochester practice-based research network (GR-PBRN) study. J Am Board Fam Med.2010;23(4):452–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinclair-Lian N, Rhyne RL, Alexander SH, Williams RL. Practice-based research network membership is associated with retention of clinicians in underserved communities: a Research Involving Outpatient Settings Network (RIOS Net) study. J Am Board Fam Med.2008;21(4):353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yawn BP, Pace W, Dietrich A, et al. Practice benefit from participating in a practice-based research network study of postpartum depression: a national research network (NRN) report. J Am Board Fam Med.2010;23(4):455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curro FA, Thompson VP, Grill A, et al. An assessment of the perceived benefits and challenges of participating in a practice-based research network. Prim Dent J.2012;1(1):50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakken S, Lantigua RA, Busacca LV, Bigger JT. Barriers, enablers, and incentives for research participation: a report from the Ambulatory Care Research Network (ACRN). J Am Board Fam Med.2009;22(4):436–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PBRN Registry. https://pbrn.ahrq.gov/pbrn-registry.Accessed June 1, 2018.

- 19.Dolor RJ, Campbell-Voytal K, Daly J, et al. Practice-based research network research good oractices (PRGPs): summary of recommendations. Clin Transl Sci.2015;8(6):638–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: a review of the literature. Fam Med.2005;37(8):581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell-Voytal K, Daly JM, Nagykaldi ZJ, practice-based research networks: a case study. Clin Transl Sci.2015;8(6):632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yawn BP, Dietrich A, Graham D, et al. Preventing the voltage drop: keeping practice-based research network (PBRN) practices engaged in studies. J Am Board Fam Med.2014;27(1):123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spears W, Tsoh JY, Potter MB, et al. Use of community engagement strategies to increase research participation in practice-based research networks (PBRNs). J Am Board Fam Med.2014;27(6):763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mungia R, Buchberg M, Hayes H, et al. Connecting and collaborating: developing National Dental PBRN study concepts through POD engagement. Health Promot Pract.2016;17(2):278–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, et al. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. BMC Oral Health.2009;9:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heaven TJ, Gordan VV, Litaker MS, et al. Concordance between responses to questionnaire scenarios and actual treatment to repair or replace dental restorations in the National Dental PBRN. J Dent.2015;43(11):1379–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert GH, Gordan VV, Korelitz JJ, et al. Provision of specific dental procedures by general dentists in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network: questionnaire findings. BMC Oral Health.2015;15:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rindal DB, Gordan VV, Fellows JL, et al. Differences between reported and actual restored caries lesion depths: results from The Dental PBRN. J Dent.2012;40(3):248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Heft MW, et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries based on radiographic images: findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent.2009;57(6):654–663; quiz 664–656, 595, 680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Richman JS, et al. How dentists diagnose and treat defective restorations: evidence from the dental practice-based research network. Oper Dent.2009;34(6):664–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norton WE, Funkhouser E, Makhija SK, et al. Concordance between clinical practice and published evidence: findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc.2014;145(1):22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert GH, Riley JL, Eleazer PD, Benjamin PL, Funkhouser E, Group NDPC. Discordance between presumed standard of care and actual clinical practice: the example of rubber dam use during root canal treatment in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. BMJ Open.2015;5(12):e009779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Dental Association Survey Center: The 2010 Survey of Dental Practice. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]