Abstract

Cholesterol activates the master growth regulator, mTORC1 kinase, by promoting its recruitment to the surface of lysosomes via the Rag guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). The mechanisms that regulate lysosomal cholesterol content to enable mTORC1 signaling are unknown. We show that Oxysterol Binding Protein (OSBP) and its anchors at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), VAPA/B, deliver cholesterol across ER-lysosome contacts to activate mTORC1. In cells lacking OSBP, but not other VAP-interacting cholesterol carriers, mTORC1 recruitment by the Rag GTPases is inhibited due to impaired cholesterol transport to lysosomes. Conversely, OSBP-mediated cholesterol trafficking drives constitutive mTORC1 activation in a disease model caused by loss of the lysosomal cholesterol transporter, Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1). Chemical and genetic inactivation of OSBP suppresses aberrant mTORC1 signaling and restores autophagic function in cellular models of NPC. Thus, ER-lysosome contacts are signaling hubs that enable cholesterol sensing by mTORC1, and targeting their sterol-transfer activity could be beneficial in NPC.

The exchange of contents and signals between organelles is key to the execution of cellular programs for growth and homeostasis, and failure of this communication can drive disease. A form of organelle communication involves exchange of cholesterol and other lipids by specialized carriers located at physical contacts between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and other membranes 1–3. Recently, cholesterol was identified as an essential activator for the master growth regulator, mTORC1 kinase. Cholesterol promotes mTORC1 recruitment from the cytosol to the lysosomal membrane, where mTORC1 triggers downstream programs for biomass production and suppression of catabolism 4–7. However, the mechanisms that deliver cholesterol to the lysosomal membrane to enable mTORC1 activation are unknown. More generally, whether and how inter-organelle contacts govern cell-wide programs for growth and quality control is not understood.

Under low cholesterol, mTORC1 cannot interact with its lysosomal scaffold, the Rag GTPases, and remains inactive in the cytosol. Conversely, stimulating cells with cholesterol triggers rapid, Rag GTPase-dependent translocation of mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and activation of its kinase function 7. Experiments in cells and reconstituted systems suggest that the Rag GTPases specifically sense the cholesterol content of the lysosomal limiting membrane 7. This cholesterol pool regulates the Rags, at least in part, via SLC38A9, a multi-pass amino acid permease also required for mTORC1 activation by amino acids 7–10

The cellular origins of the cholesterol pool that activates mTORC1 are unclear. Exogenous cholesterol carried by low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is trafficked to the lysosomal lumen, and from there it is exported to acceptor membranes via a mechanism that requires the putative cholesterol carrier, Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) 11–13. Genetic inactivation of NPC1 in humans leads to massive accumulation of cholesterol within the lysosome, compromising its functionality and triggering Niemann-Pick type C (NPC), a fatal metabolic and neurodegenerative disease 14. LDL stimulates Rag- and SLC38A9-dependent activation of mTORC1 7 and, in cells lacking NPC1, mTORC1 is hyper-active and cannot be switched off by cholesterol depletion, although the mechanistic basis for this constitutive activation remain unclear.

Following its NPC1-dependent export from the lysosome, cholesterol can be detected in several acceptor compartments including ER, Golgi and plasma membrane, but whether these compartments represent separate routes or rather stations in a common export pathway is unclear 1, 3, 15, 16. Cholesterol can also be back-transferred from the ER to several acceptor organelles, including the lysosome, via specialized carriers that reside at membrane contacts 1, 3, 15, 16. At which points along these routes cholesterol is made available for mTORC1 activation is unclear 7.

An important class of cholesterol carriers are the oxysterol binding protein (OSBP)-related proteins (ORPs) 1–3. ORPs contain at their C-terminus large, hydrophobic cavities that shield cholesterol molecules from the polar cytosolic environment and can also accommodate phospholipids 17, 18. The founding member of this family, OSBP, localizes at contacts between the ER and trans Golgi, where it is thought to transfer ER-derived cholesterol to the Golgi in exchange for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) 19–21.

OSBP was recently proposed to function at contacts between the ER and endo-lysosomes 22, 23. In concert with its binding partners on the ER, VAPA/B, OSBP regulates the PI4P content of endo-lysosomes, which in turn affects their actin-dependent motility 22. Whether OSBP also controls cholesterol levels on the lysosomal limiting membrane, and how its transport activity across ER-lysosome contacts impacts mTORC1 activation is unknown.

Here we find that, unique among several sterol carriers associated with the lysosome, OSBP establishes a lysosomal cholesterol pool that is essential for Rag GTPase-dependent mTORC1 activation. In cells lacking NPC1, unopposed ER-to-lysosome transport by OSBP drives aberrant buildup of cholesterol on the lysosomal limiting membrane. Genetic and chemical inhibition of OSBP reverses cholesterol accumulation on the limiting membrane of NPC1-null lysosomes, suppresses aberrant mTORC1 signaling and restores defective autophagy, a major driver in the pathogenesis of NPC. Thus, ER-lysosome contacts emerge as signaling nodes that coordinately regulate mTORC1 signaling and autophagy, and their manipulation via OSBP inhibitors could be beneficial in NPC and mTORC1-driven diseases.

Results

OSBP mediates cholesterol buildup on the limiting membrane of NPC1-null lysosomes

In cells lacking NPC1, mTORC1 is constitutively active and refractory to inhibition by cholesterol-depleting agents 7. This result appears paradoxical, because in the absence of NPC1 cholesterol should be trapped within the lysosomal interior and unable to reach its limiting membrane 11–13, where mTORC1 activation occurs 7. A possible resolution of this paradox is that, in NPC1-null lysosomes, not only the interior but also the limiting membrane could be cholesterol-enriched, a possibility consistent with the altered trafficking pattern of NPC1-null lysosomes 24–26. However, due to limitations of current biochemical fractionation and cholesterol-imaging approaches, it has not been possible to univocally determine the cholesterol status of the limiting membrane of NPC1-null lysosomes. To this aim, we employed a recently established cholesterol biosensor, mCherry-tagged D4H* (derived from the Clostridium Perfringens theta-toxin), which binds to membranes where cholesterol exceeds 10% molar content 27 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Recombinant D4H*-mCherry was delivered to semi-permeabilized cells using a liquid nitrogen pulse that breached the plasma membrane but left the lysosomal membrane intact (Fig. 1a), as shown by retention of LysoSensor staining (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

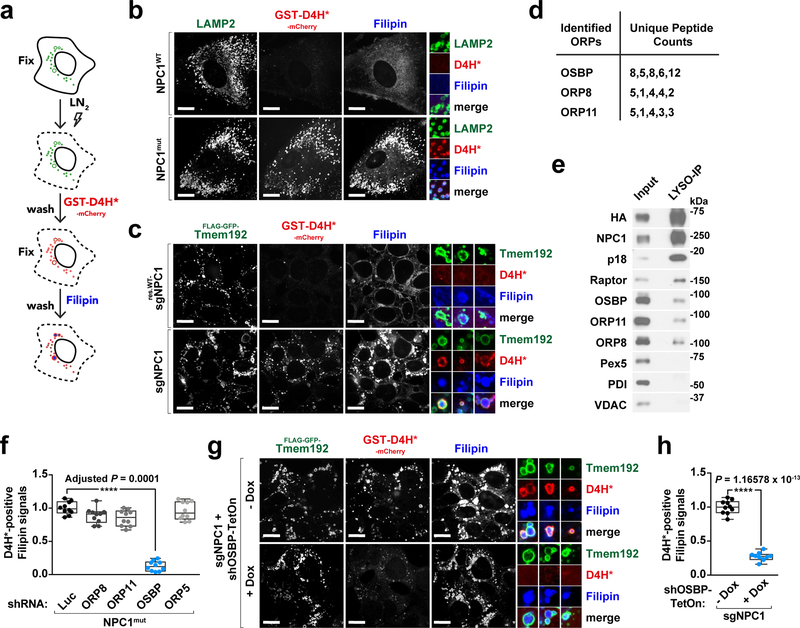

Fig. 1 |. Cholesterol accumulates at the limiting membrane of NPC1-deficient lysosomes in an OSBP-dependent manner.

a, In situ labeling assay for detecting lysosomal membrane cholesterol. b, Cholesterol is deposited at the lysosomal membrane in human NPC1 patient-derived fibroblasts. Control (NPC1WT) and NPC1 (NPC1mut) fibroblasts were fixed, breached with LN2 pulse, subjected to cholesterol labeling by GST-D4H*-mCherry and filipin, and stained for LAMP2. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, NPC1 deletion via CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in cells results in cholesterol accumulation at the lysosomal membrane. NPC1-deleted HEK-293T cells expressing FLAG-GFP-Tmem192, either naïve or reconstituted with FLAG-tagged NPC1, were processed for cholesterol labeling. Scale bar, 10 μm. Insets show three examples per genotype. d, Proteomic analysis of affinity-purified lysosomes. Lysosomes were immunopurified by anti-FLAG M2 beads (or anti-HA magnetic beads) from HEK-293T cells expressing LAMP1-mRFP-2xFLAG or Tmem192-mRFP-3xHA and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Unique peptide counts for identified ORPs shown here (n = 2 independent experiments, 5 biologically independent samples in total). See Supplementary Table 1. e, Pull-down of lysosomes revealing the lysosomal association of ORPs. Lysosomes were purified by anti-HA beads and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. f, Quantitation of co-localization of D4H*-mCherry with filipin-labeled cholesterol deposits in NPC1-null cells depleted of ORPs (box plots showing the min, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and max, 10 fields of view per genotype; n represents cell number: shLuc (n = 13), shOR8 (n = 12), shORP11 (n = 12), shOSBP (n = 11), shORP5 (n = 10), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 vs. NPC1mut-shLuc). See Supplementary Fig. 1g. g and h, Concomitant depletion of OSBP in NPC1-null cells reduces lysosomal membrane cholesterol levels. Cells were depleted of OSBP via doxycycline-induced shRNA and processed for cholesterol labeling. Scale bar, 10 μm. Insets show three examples per genotype. Quantitation in (g) (box plots as in (f), 10 fields of view per group; n represents cell number: – Dox (n = 64), + Dox (n = 72), two-tailed, unpaired t-test. ****P = 1.16578 × 10−13 vs. – Dox group). Experiments in b, c performed three times and in e, g two times.

In non-permeabilized HEK-293T cells, D4H*-mCherry solely bound to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, consistent with its inability to cross membrane bilayers (Supplementary Fig. 1c, top). In semi-permeabilized cells with intact NPC1 function, including human fibroblasts (HFs), mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and HEK-293T cells, D4H*-mCherry did not bind to the cytoplasmic leaflet of lysosomes or other endomembranes, indicating that their cholesterol content is below 10% (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1c and 1d). In contrast, D4H*-mCherry showed strong lysosomal accumulation in fibroblasts from human patients carrying a pathogenic NPC1 mutation (NPC1mut) (Fig. 1b), in Npc1−/− mouse-derived MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 1d) 28, 29, in HEK-293T cells deleted for NPC1 using CRISPR/Cas9 7 (Fig. 1c) and in control HFs treated with the chemical NPC1 inhibitor, U18666A 30 (Supplementary Fig. 1e and 1f). Thus, not only the lumen but also the limiting membranes of NPC1-null lysosomes show massive cholesterol accumulation.

Because LDL-derived cholesterol cannot escape the lumen of NPC1-null lysosomes 11–13, we hypothesized that the peripheral cholesterol buildup revealed by D4H*-mCherry might be transferred across inter-organelle contacts. To identify carriers that could mediate cholesterol transfer to lysosomes, we carried out proteomics-based analysis of immunopurified lysosomes 7, 31, 32. This analysis revealed several peptides from three ORP-family carriers: OSBP, ORP8 and ORP11 2 (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1). We confirmed lysosomal association of endogenous OSBP, ORP11 and ORP8 via immunoblotting of the immunopurified lysosomal samples (Fig. 1e).

Strikingly, knock down of OSBP, but not ORP11, ORP8 or ORP5 (which did not score as lysosome-associated) largely reversed D4H*-mCherry accumulation on the lysosomal surface of NPC1-null HFs and HEK-293T cells (Fig. 1f–1h and Supplementary Fig. 1g). In contrast, OSBP depletion did not correct luminal cholesterol accumulation of NPC1-null lysosomes, as shown by unchanged filipin staining (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 1g). We confirmed this result using the natural product OSW-1, which inhibits OSBP (along with closely related OSBP2) with nanomolar potency 20, 33. Treatment with OSW-1 caused the D4H*-mCherry signal, but not the filipin signal, to disappear from lysosomes of NPC1-null HFs, MEFs and HEK-293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a–2f).

Thus, unique among the ORPs, OSBP appears to be responsible for accumulation of cholesterol on the limiting membrane but not within the lumen of NPC1-null lysosomes.

OSBP localizes to ER-lysosome contacts and controls lysosomal cholesterol levels in wild-type cells

OSBP was shown to mainly reside at ER-TGN contacts 19, 34, 35. However, in HEK-293A cells we also detected stably expressed GFP-OSBP around LAMP2-positive lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 3a). GFP-OSBP also co-localized with endogenous mTOR and with the p18 subunit of the Ragulator/Lamtor complex, which anchors the Rag GTPases and mTORC1 to the lysosomal membrane 5, 36 (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Association of OSBP with LAMP2-, mTOR- or p18-positive vesicles was abolished by deletion of its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, which anchors OSBP to the Golgi or endolysosomal membrane by binding to PI4P 22, 37–39 (Supplementary Fig. 3a and 3b). As OSBP transfers PI4P from Golgi and endolysosomes toward the ER, it is thought to weaken its own association with these organelles 19, 20. Consistently, a transport-defective OSBP mutant (ΔELSK) 40 was more strongly clustered on LAMP2-positive structures than wild-type OSBP (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Similarly, inhibiting OSBP with OSW-1 resulted in strong clustering of GFP-OSBP to lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Staining HEK-293A cells with an antibody that recognizes endogenous OSBP showed partial co-localization with LAMP2 that was enhanced by shRNA-mediated depletion of VAPA/B, as previously shown 22 (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

Next, we asked whether OSBP regulates limiting membrane cholesterol of not only NPC1-null but also wild-type lysosomes. Because mCherry-D4H* did not bind to lysosomes with intact NPC1 function, we carried out lipidomic analysis of immunopurified lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Inhibiting OSBP prior to immunopurification caused a 30% reduction in cholesterol content, suggesting that a significant fraction of the lysosomal cholesterol pool is ER-derived and transferred by OSBP (Fig. 2a). Whole-cell lipidomics showed that, although the total cholesterol content of OSBP-depleted cells was unchanged, a larger fraction was esterified to oleic acid than in control cells 20, 38 (Supplementary Fig. 4b and 4c). Moreover, filipin staining showed strong accumulation of cholesterol in the ER of cells treated with OSBP-targeting shRNA or with the OSBP inhibitor OSW-1 (Supplementary Fig. 4d and 4e).

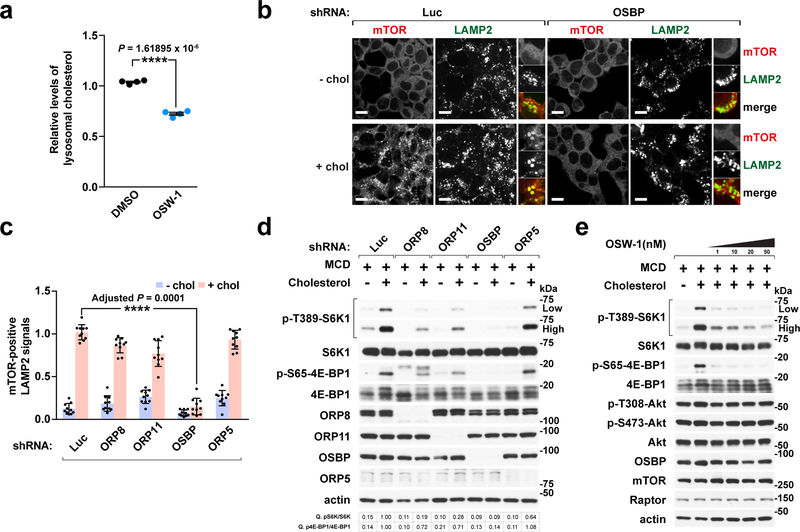

Fig. 2 |. OSBP is required for cholesterol-dependent lysosomal recruitment and activation of mTORC1.

a, OSBP inhibition by OSW-1 treatment reduces the lysosomal cholesterol content. HEK-293T cells expressing Tmem192-mRFP-3xHA were treated with DMSO or 20 nM OSW-1 for 8h. Lysosomes were purified and analyzed by mass spectrometry (mean ± s.d., n = 4 biologically independent samples per treatment, two-tailed, unpaired t-test. ****P = 1.61895 × 10−6 vs. DMSO). See immunoblots in Supplementary Fig. 4a. b, OSBP is specifically required for lysosomal recruitment of mTORC1 by cholesterol. Cells depleted of OSBP were subjected to cholesterol depletion and restimulation, where indicated, followed by immunofluorescence for endogenous mTOR and LAMP2. Representative images are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, Quantitation of co-localization of mTOR with LAMP2-positive lysosomes in cells expressing the indicated shRNAs (mean ± s.d., 10 fields of view per genotype/condition; n represents cell number: shLuc – chol (n = 182), shLuc + chol (n = 181), shORP8 – chol (n = 104), shORP8 + chol (n = 91), shORP11 – chol (n = 157), shORP11 + chol (n = 156), shOSBP – chol (n = 176), shOSBP + chol (n = 182), shORP5 – chol (n = 160), shORP5 + chol (n = 166), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 vs. shLuc + chol). See representative images in Supplementary Fig. 6a. d, ORPs affect mTORC1 activation by cholesterol. Cells were sterol-depleted using methyl-beta cyclodextrin (MCD, 0.5% w/v) for 2h and restimulated for 2h with 50 μM cholesterol complexed with 0.1% MCD (MCD:cholesterol). Cell lysates were analyzed for the levels of indicated proteins and for phosphorylation status of S6K1 (T389), 4E-BP1 (S65). Fold changes of protein phosphorylation are indicated. e, OSW-1 inhibits sterol-induced mTORC1 signaling in a dose-dependent manner. Cells were subjected to cholesterol starvation and restimulation in the presence of DMSO or OSW-1 at the indicated concentrations and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. Experiments in b, d performed three times and in a, e two times. See unprocessed blots in Supplementary Figure 9. Statistics source data are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

To independently visualize OSBP-dependent sterol transport to the lysosomal limiting membrane, we pulse-chased cells with a fluorescent cholesterol analog, TopFluor-cholesterol. In DMSO-treated cells, TopFluor-cholesterol initially appeared at the plasma membrane, and began accumulating in lysosomes by 30 minutes (Supplementary Fig. 5a and 5b). In contrast, OSW-1 treatment delayed TopFluor-cholesterol clearance from the plasma membrane and caused it to acquire an ER-like distribution, never building up in lysosomes to a noticeable degree (Supplementary Fig. 5a and 5b). Although off-target inhibition of other ORPs cannot be entirely ruled out, the most likely explanation for this result is that OSBP mediates a key step in a pathway that moves cholesterol from the plasma membrane to the lysosomal limiting membrane via the ER.

OSBP is essential for mTORC1 activation by cholesterol

Because lysosomal membrane cholesterol drives mTORC1 activation 7, we tested the requirement for OSBP in mTORC1 lysosomal recruitment and kinase activation. In HEK-293T cells, OSBP was absolutely required for cholesterol-induced translocation of mTOR to LAMP2-positive structures, whereas ORP8, ORP11 or ORP5 were completely dispensable (Fig. 2b, 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Consistent with the loss of lysosomal localization, depleting OSBP strongly blunted cholesterol-dependent mTORC1 activation, as shown by loss of phosphorylation of canonical substrates S6-kinase 1 (S6K1) and 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1). In contrast, knocking down ORP8, ORP11 and ORP5 had smaller or no effect on mTORC1 kinase activity (Fig. 2d).

Inhibiting OSBP activity with OSW-1 also suppressed cholesterol-induced mTORC1 lysosomal recruitment and activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 6b and 6c). Even under complete media conditions, OSBP ablation strongly reduced lysosomal mTORC1 recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 6d and 6e) and signaling (Supplementary Fig. 6f). In contrast, OSBP depletion affected acute mTORC1 activation by amino acids only modestly, suggesting that OSBP is not directly involved in amino acid sensing (Supplementary Fig. 6g).

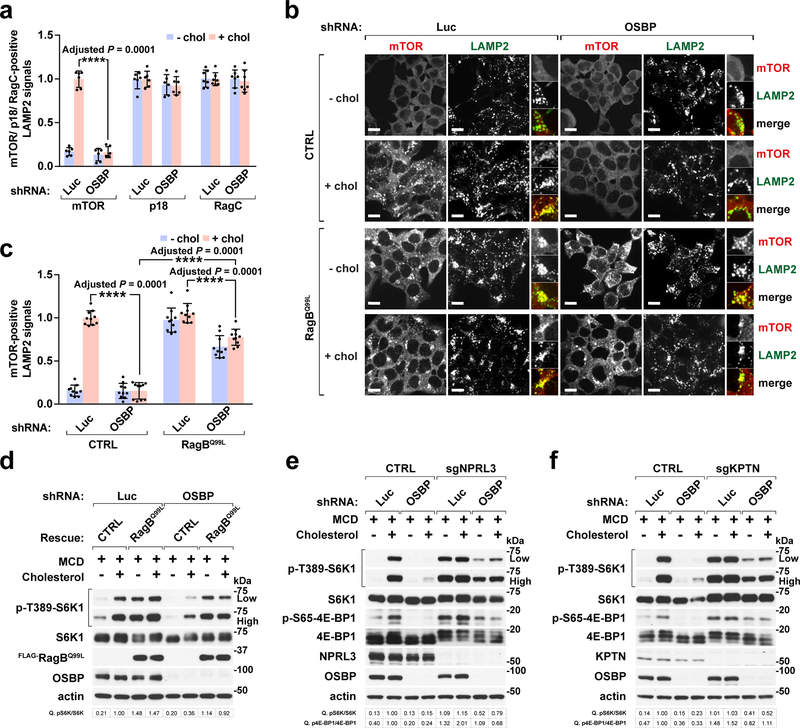

OSBP depletion had no effect on the lysosomal localization of RagC and p18/Lamtor1 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 6h). Thus, OSBP loss impairs the ability of the Ragulator-Rag complex to recruit mTORC1, but not its integrity. Consistent with this interpretation, stable expression of GTP-locked RagBQ99L mutant, which bypasses mTORC1 inactivation by both amino acid and cholesterol depletion 4, 6, 7, largely rescued the effect of OSBP depletion on lysosomal mTORC1 recruitment (Fig. 3b and 3c) and signaling (Fig. 3d). Similarly, mTORC1 signaling was resistant to OSBP depletion in cells lacking the NPRL3 component of the GATOR1 complex or the KPTN subunit of the KICSTOR complex, which inactivate the Rag GTPases under low nutrients 41–43 (Fig. 3e and 3f).

Fig. 3 |. OSBP regulates mTORC1 upstream of the Rag GTPases.

a, OSBP depletion abolishes sterol-dependent mTORC1 recruitment to lysosomes without compromising the integrity of mTORC1 scaffolding complex. Quantitation of co-localization of mTOR, p18, and RagC with LAMP2-positive lysosomes (mean ± s.d., 6 fields of view per genotype/condition; n represents cell number: mTOR for shLuc – chol (n = 126), shLuc + chol (n = 91), shOSBP – chol (n = 115), shOSBP + chol (n = 106); p18 for shLuc – chol (n = 105), shLuc + chol (n = 101), shOSBP – chol (n = 92), shOSBP + chol (n = 89); RagC for shLuc – chol (n = 88), shLuc + chol (n = 90), shOSBP – chol (n = 77), shOSBP + chol (n = 79), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 vs. shLuc + chol). See Supplementary Fig. 6h. b, OSBP mediates mTORC1 lysosomal recruitment upstream of the Rag GTPases. Control HEK-293T and cells expressing the constitutively active RagBQ99L were depleted of OSBP and evaluated for sterol-dependent lysosomal localization of mTORC1. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, Quantitation of co-localization of mTOR with LAMP2-positive lysosomes (mean ± s.d., 10 fields of view per each genotype/condition; n represents cell number: CTRL-shLuc – chol (n = 185), CTRL-shLuc + chol (n = 146), CTRL-shOSBP – chol (n = 154), CTRL-shOSBP + chol (n = 164); RagBQ99L-shLuc – chol (n = 142), RagBQ99L-shLuc + chol (n = 148), RagBQ99L-shOSBP – chol (n = 128), RagBQ99L-shOSBP + chol (n = 143), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 as indicated). d, OSBP activates mTORC1 signaling via the Rag GTPases. Cells were starved of cholesterol, refed where indicated, and analyzed for mTORC1 signaling. e and f, Loss of GATOR1 or KICSTOR largely rescues the effects of OSBP depletion on mTORC1 signaling. NPRL3-deleted (e) or KPTN-deleted (f) HEK-293T cells were analyzed for sterol-induced mTORC1 signaling. Fold changes of protein phosphorylation are shown in d, e and f. Experiments in d, e and f repeated independently two times. See unprocessed blots in Supplementary Figure 9. Statistics source data are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Taken together, these data indicate that OSBP enables mTORC1 activation by cholesterol via a pathway that converges on the Rag GTPases.

OSBP mediates ER-to-lysosome cholesterol transfer that enables mTORC1 activation

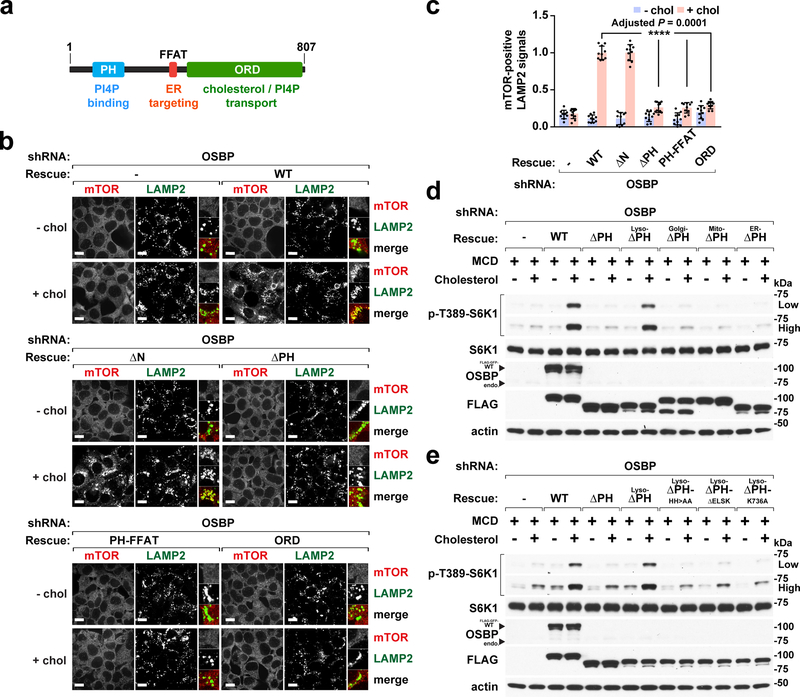

To determine whether and how the cholesterol transport function of OSBP participates in mTORC1 regulation, we reconstituted OSBP-depleted cells with isoforms lacking key functions (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Disabling OSBP attachment to the lysosome (by deleting or mutating the PH domain) or to the ER (by mutating the Phenylalanines in Acidic Tract (FFAT) motif that mediates OSBP interaction with VAPA/B) or both (by expressing the ORD alone) 38, resulted in failure to rescue mTORC1 lysosomal recruitment (Fig. 4a–4c and Supplementary Fig. 7a) and activation by cholesterol (Supplementary Fig. 7b and 7c). Disabling the OSBP transport cycle by deleting or mutating critical residues in the ORD 17, 40 also abolished cholesterol-dependent mTORC1 activation (Supplementary Fig. 7b and 7c). Thus, mTORC1 activity requires both the membrane-anchoring and lipid-transporting functions of OSBP.

Fig. 4 |. Both the lipid-transporting and lysosome-targeting functions of OSBP are required for mTORC1 activation by cholesterol.

a, Domain organization of OSBP and related functions. b, The membrane tethering and lipid transfer functions of OSBP are required for lysosomal recruitment of mTORC1. OSBP-depleted cells and cells that were re-engineered as indicated were subjected to cholesterol starvation and restimulation, followed by immunofluorescence for endogenous mTOR and LAMP2. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, Quantitation of co-localization of mTOR with LAMP2-positive lysosomes in cells reconstituted with different truncations as indicated (mean ± s.d., 10 fields of view per each genotype/condition; n represents cell number: shOSBP – chol (n = 173), shOSBP + chol (n = 170), rescued WT – chol (n = 185), rescued WT + chol (n = 154), rescued ΔN – chol (n = 179), rescued ΔN + chol (n = 131), rescued ΔPH – chol (n = 169), rescued ΔPH + chol (n = 168), rescued PH-FFAT – chol (n = 188), rescued PH-FFAT + chol (n = 179), rescued ORD – chol (n = 185), rescued ORD + chol (n = 168), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 vs. rescued WT + chol). d, Linking OSBP to the lysosome but not to other organelles restores mTORC1 activation by cholesterol. Cells were depleted of OSBP and reconstituted with PH domain-deleted isoforms that carry organelle-targeting sequences, subjected to cholesterol starvation and restimulation. Cell lysates were analyzed for the indicated proteins and phospho-proteins. e, The lipid transfer activity of lysosome-targeted OSBP is essential for mTORC1 activation. Cells were depleted of OSBP and reconstituted with the indicated lyso-OSBP constructs, subjected to cholesterol starvation and restimulation. Cell lysates were analyzed for the indicated proteins and phospho-proteins. Experiments in d and e repeated independently two times. See unprocessed blots in Supplementary Figure 9. Statistics source data are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Because OSBP resides at both ER-lysosome and ER-Golgi contacts, we rigorously tested whether OSBP regulates mTORC1 through lipid transport from ER to lysosomes and not elsewhere. We reconstituted OSBP-depleted cells with OSBP isoforms in which the PH domain is replaced with organelle-specific targeting signals, while retaining attachment to the ER via VAP (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Only OSBP fused to a lysosomal targeting sequence (the 39 N-terminal amino acids of p18) 5, 44 rescued mTORC1 activation by cholesterol, whereas OSBP isoforms targeted to mitochondria, ER and, most crucially, Golgi failed to do so (Fig. 4d). Rescue of mTORC1 signaling by lysosome-targeted OSBP required its lipid-transport activity, as it was abolished by mutations in the ORD that disrupt either cholesterol or PI4P binding (Fig. 4e).

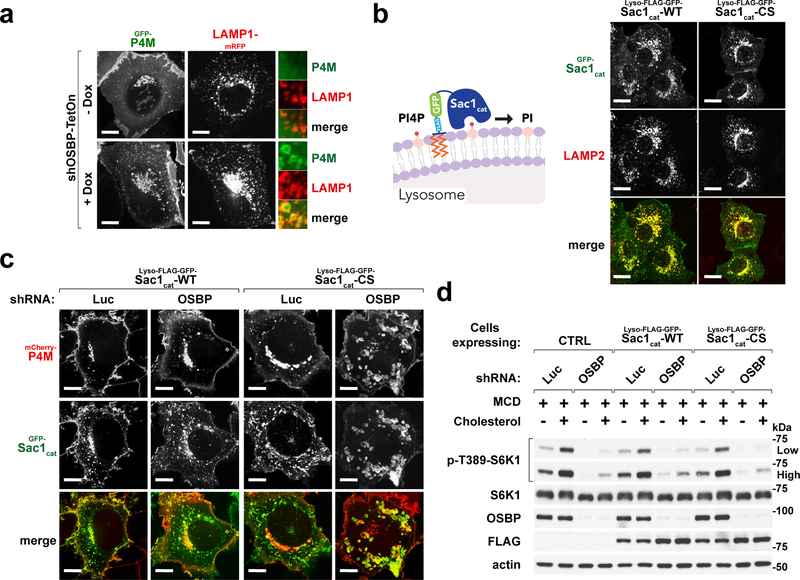

The OSBP transport cycle involves exchange of cholesterol with PI4P 20, 38. Consistently, OSBP depletion caused strong accumulation of PI4P on lysosomes, as shown with a genetically encoded PI4P probe, GFP-P4M 37 (Fig. 5a). To rule out a role for lysosomal PI4P buildup in mTORC1 inhibition, we fused the catalytic domain of Sac1 phosphatase, which hydrolyzes PI4P to phosphatidylinositol, to the lysosome-anchoring sequence of p18 (lyso-Sac1) (Fig. 5b) 5, 37, 44. In OSBP-depleted cells, lyso-Sac1 completely reversed lysosomal buildup of PI4P caused by OSBP inactivation, whereas a catalytically inactive lyso-Sac1 mutant (C389S) failed to do so (Fig. 5c). However, neither the catalytically active nor the inactive lyso-Sac1 restored mTORC1 activation in OSBP-depleted cells (Fig. 5d). Thus, lysosomal PI4P accumulation is unlikely to contribute to mTORC1 inhibition triggered by OSBP inactivation.

Fig. 5 |. Excess lysosomal PI4P upon OSBP inhibition does not cause mTORC1 inhibition.

a, Depletion of OSBP results in accumulation of PI4P at the lysosomes. HEK-293A cells stably expressing the PI4P-specific probe, GFP-P4M, along with LAMP1-mRFP were depleted of OSBP via doxycycline-induced shRNA. Cells were plated on glass-bottom dishes, allowed to attach overnight and imaged live on a spinning disk confocal microscope. Representative microscopic images are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. b, Confirmation of lysosomal localization of the lysosome-targeted Sac1 catalytic domain truncations in HEK-293A cells. (left) Schematic diagram showing Sac1 catalytic domain is targeted to the lysosome to hydrolyze its target PI4P. (right) Representative microscopic images are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, Ectopic expression of a lysosome-targeted Sac1 catalytic domain eliminates excess lysosomal PI4P in OSBP-depleted cells. HEK-293T cells co-expressing mCherry-P4M and either catalytically active (WT) or inactive (CS) forms of lyso-Sac1 were depleted of OSBP and subjected to live-cell imaging. Representative confocal microscopic images are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. d, Lysosomal PI4P buildup caused by OSBP depletion is not responsible for mTORC1 inhibition. Control cells and cells expressing catalytically active and inactive lyso-Sac1 were depleted of OSBP, followed by cholesterol starvation/restimulation, lysis and immunoblotting for the indicated proteins and phospho-proteins. See unprocessed blots in Supplementary Figure 9. Experiments in a–d repeated independently two times.

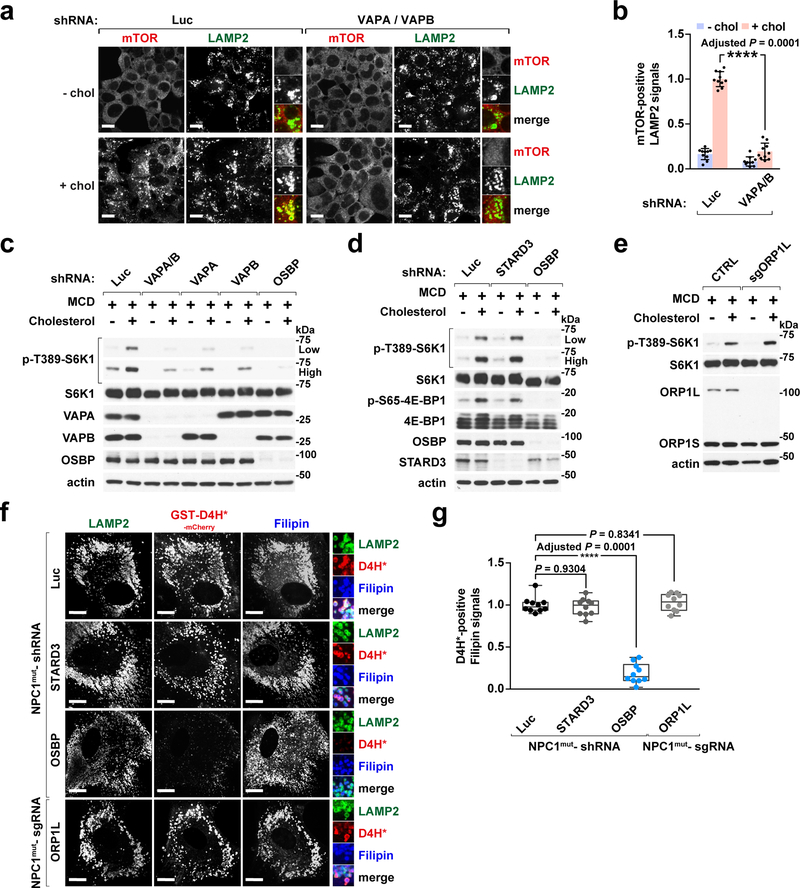

Finally, consistent with OSBP functioning at ER-lysosome contacts, shRNA-mediated depletion of VAPA/B suppressed lysosomal mTORC1 localization (Fig. 6a and 6b) and signaling (Fig. 6c). While other FFAT-containing proteins including STARD3 and ORP1L 16, 45 also transfer cholesterol across ER-lysosome contacts, they were completely dispensable for cholesterol-dependent mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 6d and 6e). Moreover, depletion of STARD3 or ORP1L did not reverse lysosomal surface cholesterol accumulation in NPC1-null cells, as shown by unchanged D4H*-mCherry staining (Fig. 6f and 6g). Thus, OSBP and VAPs form a cholesterol-transporting system at ER-lysosome contacts that is uniquely involved in mTORC1 activation by cholesterol.

Fig. 6 |. VAPA and VAPB, the ER anchors for OSBP, are essential for cholesterol-dependent mTORC1 activation.

a, VAPA/B depletion abolishes the lysosomal recruitment of mTORC1 by cholesterol. HEK-293T cells were depleted for VAPA and VAPB via shRNA and evaluated for mTOR lysosomal localization. Scale bar, 10 μm. b, Quantitation of co-localization between mTOR and LAMP2-positive lysosomes in control cells and cells depleted of VAPA and B (mean ± s.d., 10 fields of view per genotype/condition; n represents cell number: shLuc – chol (n = 124), shLuc + chol (n = 74), shVAPA/VAPB – chol (n = 178), shVAPA/VAPB + chol (n = 163), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****P = 0.0001 vs. shLuc + chol). c, VAPA and VAPB are necessary for cholesterol-dependent mTORC1 activation. HEK-293T cells were depleted of VAPA and VAPB, either alone or in combination, and evaluated for sterol-induced mTORC1 signaling via immunoblotting. d and e, STARD3 and ORP1L are not required for cholesterol-dependent mTORC1 signaling. Cells depleted of STARD3 or OSBP via shRNA (d) and ORP1L knockout cells (e) were assayed for sterol-induced mTORC1 activation via immunoblotting. f, Depletion of STARD3 or ORP1L has no effects on both peripheral and internal pools of lysosomal cholesterol in NPC1-deficient cells. Human NPC1 patient-derived fibroblasts depleted of STARD3 or OSBP via shRNA or deleted of ORP1L via CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing were subjected to cholesterol labeling by GST-D4H*-mCherry and filipin, and stained for endogenous LAMP2. Scale bar, 10 μm. g, Quantitation of co-localization of D4H*-mCherry with filipin-labeled cholesterol deposits in NPC1-null cells that were silenced of STARD3, OSBP, and ORP1L, respectively (box plots showing the min, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and max, 10 fields of view per genotype; n represents cell number: shLuc (n = 12), shSTARD3 (n = 10), shOSBP (n = 10), sgORP1L (n = 11), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 vs. NPC1mut-shLuc). Experiments in c–e performed independently two times with similar results. See unprocessed blots in Supplementary Figure 9. Statistics source data are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

NPC1 regulates the number of ER-lysosome contacts and their sterol-transporting activity

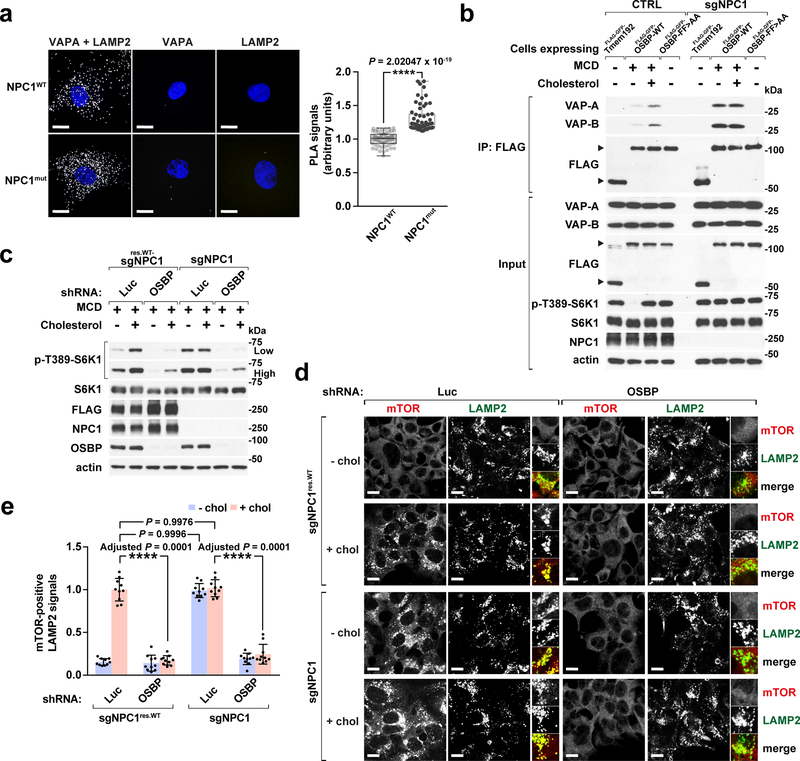

Our D4H*-mCherry results strongly suggest that ER-to-lysosome cholesterol transport is elevated in NPC1-null cells. Consistently, ER-lysosome contacts appeared enlarged in NPC1-null cells. In control human fibroblasts co-expressing the lysosomal and ER markers GFP-Tmem192 and mCherry-Sec61b, respectively, physical contacts between lysosomes and ER could be readily visualized 23, 46 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In NPC1mut fibroblasts, the ER domains in direct contact with lysosomes appeared significantly enlarged and were more persistent than those in control cells (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Further investigation using electron microscopy (EM) showed numerous ER tubules closely apposed to the characteristically enlarged NPC1-null lysosomes, recognizable by the accumulation of undigested membranes and electron-dense material within their lumen14 (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Because membrane contacts cannot be univocally identified by EM, we bolstered these observations with proximity ligation assay (PLA) for VAPA and LAMP2, which yields a fluorescent signal when the two membrane markers come within 10–30 nm from each other. VAP-LAMP2 PLA confirmed that ER-lysosome contacts are significantly increased in NPC1-null versus wild-type cells (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7 |. OSBP inhibition abrogates aberrant mTORC1 signaling in NPC1-deficient cells.

a, (left) Increased ER-lysosome contacts in NPC1 fibroblasts. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, labelled with VAPA or LAMP2 antibodies, or in combination as indicated, and subjected to proximity ligation assay (PLA). Scale bar, 10 μm. (right) Quantitation of PLA signals (box plots showing the min, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and max, 60 fields of view per group; n represents cell number: NPC1WT (n = 60), NPC1mut (n = 60), two-tailed, unpaired t-test. ****P = 2.02047 × 10−19 vs. NPC1WT). b, Cholesterol regulates OSBP-VAP interaction in an NPC1-dependent manner. Control and NPC1-null cells expressing the FLAG-GFP-Tmem192, FLAG-GFP-OSBP-WT, and FLAG-GFP-OSBP-FF>AA, respectively, were starved and refed with cholesterol, lysed and processed for FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP). Both IP and input samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. Experiments repeated two times with similar results. c, Depletion of OSBP abolishes constitutive mTORC1 signaling in NPC1-null cells. NPC1-deleted HEK-293T cells, either naïve or reconstituted with stably expressed FLAG-tagged NPC1, were depleted of OSBP and analyzed for sterol-induced mTORC1 signaling via immunoblotting. Experiments repeated two times. d and e, OSBP depletion abrogates constitutive mTORC1 lysosomal localization in NPC1-null cells. NPC1-deleted HEK-293T cells, either naïve or reconstituted with stably expressed FLAG-tagged NPC1, were depleted of OSBP and evaluated for sterol-dependent mTORC1 lysosomal localization. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantitation in (e) (mean ± s.d., 10 fields of view per each genotype/condition; n represents cell number: sgNPC1res.WT-shLuc – chol (n = 166), sgNPC1res.WT-shLuc + chol (n = 110), sgNPC1res.WT-shOSBP – chol (n = 181), sgNPC1res.WT-shOSBP + chol (n = 132), sgNPC1-shLuc – chol (n = 127), sgNPC1-shLuc + chol (n = 142), sgNPC1-shOSBP – chol (n = 147), sgNPC1-shOSBP + chol (n = 131), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 as indicated). See unprocessed blots in Supplementary Figure 9. Statistics source data are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

To determine the mechanistic basis for enhanced ER-to-lysosome cholesterol transport, we carried out OSBP-VAP co-immunoprecipitation experiments, and found that the OSBP-VAP interaction is stronger in NPC1-null than in wild-type cells. Interestingly, in wild-type cells the OSBP-VAP interaction is promoted by cholesterol, whereas it is constitutively high in NPC1-deleted cells (Fig. 7b). Thus, cholesterol may promote its own transport to the lysosome by increasing OSBP-VAP complex formation, whereas NPC1 inhibits this process, leading to OSBP-dependent cholesterol accumulation on the limiting membranes of NPC1-null lysosomes.

OSBP inactivation corrects aberrant mTORC1 signaling and defective autophagy in NPC1-null cells

We previously observed that, in NPC1-null cells, mTORC1 signaling is elevated and resistant to cholesterol-depleting agents7. Based on the D4H*-mCherry data and the increased formation of OSBP-VAP complexes (Supplementary Fig. 8a–8b, Fig. 7a and 7b), we hypothesized that constitutive mTORC1 activation may be driven by OSBP-dependent accumulation of cholesterol on the limiting membrane of NPC1-null lysosomes.

Consistent with this model, knocking down OSBP resulted in complete inactivation of mTORC1, irrespective of NPC1 status (Fig. 7c). Moreover, OSBP depletion suppressed constitutive lysosomal mTORC1 localization in NPC1-deleted cells (Fig. 7d and 7e).

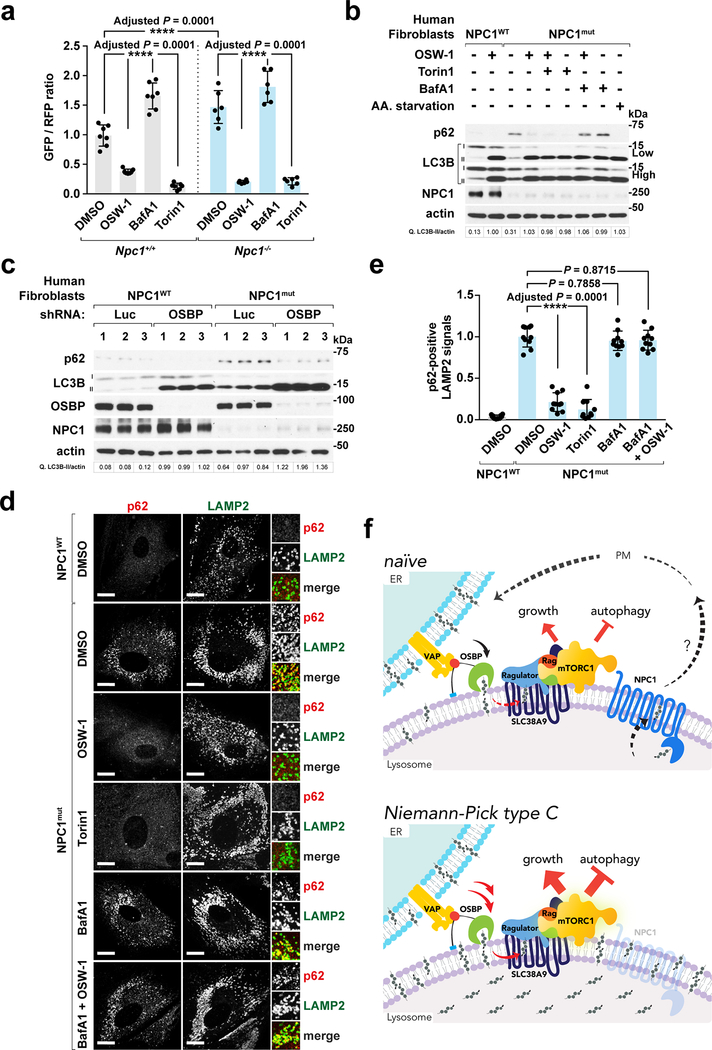

A major downstream consequence of aberrant mTORC1 activation is suppression of autophagy. Indeed, as in other neurodegenerative disorders, autophagic flux is decreased in NPC and it may drive the defective cellular quality control that contributes to this disease 29, 47, 48. Using a cleavable, dual-color LC3 reporter 49 we verified that autophagic flux is reduced in Npc1−/− compared to wild-type MEFs (Fig. 8a). Notably, OSBP inhibition using OSW-1 increased autophagic flux both in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− cells with potency similar to the catalytic mTOR inhibitor, Torin1 (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8 |. OSBP inhibition restores autophagic function in NPC1-deficient cells.

a, OSW-1 increases autophagic flux in both Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs expressing the GFP-LC3-RFP-LC3ΔG reporter. Normalized GFP/RFP fluorescence ratio expressed as fold change over DMSO-treated Npc1+/+ cells (mean ± s.d., n represents number of biologically independent samples: Npc1+/+ DMSO (n = 7), Npc1+/+ OSW-1 (n = 7), Npc1+/+ BafA1 (n = 7), Npc1+/+ Torin1 (n = 7), Npc1−/− DMSO (n = 6), Npc1−/− OSW-1 (n = 6), Npc1−/− BafA1 (n = 6), Npc1−/− Torin1 (n = 6), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 as indicated). b, OSW-1 treatment abolishes p62/SQSTM1 accumulation in NPC1 fibroblasts. Cells were subjected to the indicted treatments and immunoblotted for p62 and LC3B. Experiments repeated two times. c, OSBP depletion reduces p62 accumulation in human NPC1 patient-derived cells. Cells were depleted of OSBP and analyzed by immunoblotting (n = 3 biologically independent samples per genotype). Fold changes of LC3B-II to actin in b and c are indicated. Experiment performed once. d and e, p62 clearance by OSW-1 in NPC1 fibroblasts. Cells were subjected to treatments for 8h, and stained for p62 and LAMP2. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantitation in (e) (mean ± s.d., 10 fields of view per each genotype/treatment; n represents cell number: NPC1WT DMSO (n = 14), NPC1mut DMSO (n = 10), NPC1mut OSW-1 (n = 11), NPC1mut Torin1 (n = 11), NPC1mut BafA1 (n = 11), NPC1mut BafA1 + OSW-1 (n = 12), ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****Adjusted P = 0.0001 vs. DMSO-treated NPC1mut cells). Statistics source data are provided in Supplementary Table 2. f, Across ER-lysosome contacts, OSBP-VAP generates a peripheral pool of lysosomal cholesterol that recruits and activates mTORC1 via the Rag GTPases. Conversely, NPC1 suppresses mTORC1 by limiting the levels of peripheral cholesterol. Thus, the steady-state levels of mTORC1 activation are balanced by the opposite transport route of cholesterol. In cells lacking NPC1, cholesterol accumulates both in the lysosomal lumen and, via unopposed ER-to-lysosome transport by OSBP, on the lysosomal membrane. In turn, excess lysosomal membrane cholesterol drives constitutively elevated mTORC1 signaling and inhibits autophagy.

NPC1-defective MEFs and human patient fibroblasts showed pronounced accumulation of the autophagic adaptor p62/SQSTM1, indicating disrupted autophagic degradation 50. OSW-1 resolved p62/SQSTM1 accumulation in a dose-dependent manner, decreasing its levels to those of control cells (Supplementary Fig. 8c and 8d), as did shRNA-mediated OSBP knock down (Fig. 8c). OSW1-induced clearance of p62/SQSTM1 was prevented by the vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor, bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) (Fig. 8b and Supplementary Fig. 8e). Importantly, mTORC1 inhibition via Torin1 was as effective as OSW-1 in clearing p62/SQSTM1, and their combined treatment provided no additional benefit, suggesting that both compounds act via a mechanism converging on mTORC1 (Fig. 8b and Supplementary Fig. 8f).

Immunofluorescence for p62 in human patient fibroblasts showed massive accumulation of intracellular aggregates in NPC1mut cells that partially overlapped with LAMP2-positive lysosomes (Fig. 8d and 8e). Consistent with the immunoblotting results, intracellular p62/SQSTM1 aggregates were largely cleared by treatment with OSW-1 and Torin1, and this effect was reversed by BafA1 (Fig. 8d and 8e). Together, these data demonstrate that inhibiting aberrant, OSBP-driven mTORC1 signaling in NPC cells is sufficient to restore delivery of autophagic cargo to the lysosome and its subsequent degradation.

Discussion

This work identifies OSBP as the key component of a transport circuit that coordinately regulates cholesterol levels and mTORC1 activation at the lysosomal membrane (Fig. 8f). In concert with its ER membrane anchor, VAPA/B, OSBP delivers cholesterol in the ER-to-lysosome direction in exchange for PI4P 22, 38. Cholesterol deposited on the lysosome by OSBP may directly interact with the mTORC1 scaffolding machinery that includes SLC38A9, Ragulator and vacuolar H+-ATPase, leading to Rag GTPase activation and mTORC1 recruitment 5, 7, 10, 31 (Fig. 8f). Notably, OSBP was unique among VAP-interacting proteins in directly controlling mTORC1 activation. The partial decrease in mTORC1 signaling caused by depleting ORP8 and ORP11 likely occurs via indirect mechanisms not connected to lysosomal cholesterol trafficking 16, 45, 51–53

In yeast, intracellular transport of ergosterol has been implicated in TORC1 regulation by nitrogen, as well as its inactivation under stress 54, 55. Through the transport action of OSBP-VAP, ER-lysosome contacts in metazoan cells emerge as signaling nodes where information about cholesterol availability is integrated and translated into mTORC1-driven growth programs. Because the majority of endo-lysosomes contact the ER over time scales of several minutes, the regulatory action of these junctions on mTORC1 signaling is expected to be pervasive and to couple the pace of cell growth to the levels of intracellular cholesterol 2, 3

Our results shed light on how NPC1 regulates lysosomal cholesterol levels, a problem with significant implications for metabolic and neurodegeneration research 14, 56. Upon accepting luminal cholesterol from NPC2, NPC1 may facilitate its insertion into the lysosomal limiting membrane for subsequent export, or directly hand it over to acceptors that remain unidentified 11–13, 57. How does cholesterol handling by NPC1 lead to mTORC1 inhibition? Recent evidence indicates that LDL-derived cholesterol is rapidly removed from the lysosome and transported to the plasma membrane in an NPC1-dependent manner 58. Rapid, NPC1-dependent export may prevent cholesterol liberated from LDL from accumulating at the lysosomal surface and interacting with the mTORC1 scaffolding complex 7. Subsequently, OSBP-VAP may return cholesterol to the lysosomal surface across ER-lysosome contacts in a controlled manner. Consistent with this model, exogenously delivered TopFluor-cholesterol requires OSBP to exit the ER and reach the lysosomal limiting membrane.

Alternatively, NPC1 may promote the lateral segregation of lysosomal membrane cholesterol into domains analogous to the ones reported on the yeast vacuole, and which may not be accessible to the mTORC1 scaffolding complex 59, 60. Ultimately, mTORC1 activity results from the balance between the sterol-transport activities of OSBP-VAP and NPC1. While we could not detect a direct interaction between OSBP and NPC1 in co-IP studies, we did find that NPC1 status affects the interaction between OSBP and VAPA/B. Thus, NPC1 may exert feedback regulation on OSBP, possibly via its cholesterol transport activity. Further studies are required to shed light on the mechanistic basis for this regulation. More broadly, these data support the idea that ER-lysosome contacts are bona fide signaling structures, that can modulate the rate of cholesterol transport in response to physiological stimuli. Moreover, given that neither NPC1 nor OSBP are required for acute mTORC1 response to amino acids7 (Supplementary Fig. 6g), ER-lysosome contacts are likely dedicated to mTORC1 regulation by cholesterol inputs.

By modulating the cholesterol content of the lysosomal limiting membrane, OSBP has a profound influence on the initiation and execution of autophagy. This was especially evident in cellular models of Niemann-Pick type C, where OSBP inhibition was sufficient to restore autophagic flux, leading to clearance of the canonical autophagic substrate, p62. Previous studies in patient-derived cells have uncovered defects in both autophagosome-lysosome fusion and in the subsequent breakdown of autophagic substrates 29, 47, 48, 61. These defects can be explained, at least in part, by the observed accumulation of cholesterol on the lysosomal limiting membrane (Fig. 1b and 1c), which could lead to mis-trafficking of lysosomes and compromise their ability to fuse with other organelles 24, 62, 63. In the context of NPC, OSBP inhibition restores autophagic function likely by reducing cholesterol buildup at the lysosomal membrane, which has the dual effect of enhancing autophagy initiation (via mTORC1 inhibition) and, potentially, restoring lysosomal trafficking and fusion with autophagosomes.

The availability of nanomolar OSBP inhibitors, such as OSW-1 33, suggests that chemical modulation of OSBP could be a promising strategy to correct lysosomal function and to restore proteostasis in Niemann-Pick type C, as well as in diseases driven by excess mTORC1 signaling.

Methods

Antibodies and Chemicals

Antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. LDL (J65039) from Alfa Aesar. Amino acids, lysozyme (62970), cholesterol (C3045), filipin (F9765) and methyl-beta-cyclodextrin ((MCD), C4555), bafilomycin A1 (B1793), U18666A (U3633) from Sigma-Aldrich. TopFluor-cholesterol (810255P) from Avanti Polar Lipids. Torin1 (4247) from Tocris Bioscience. Pierce Protease Inhibitor Tablets (A32965) from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Glutathione Sepharose 4B (17–0756-05) from Pierce. LysoSensor Green DND-189 (L7535) and DMEM (11965) from Life Technologies. Amino acid-free RPMI (R9010–01) from US Biologicals. OSW-1 was a generous gift from Matthew D Shair (Harvard University).

Mammalian cell culture

Human HEK-293A, HEK-293T, HEK-293T NPC1-null, HEK-293T NPRL3-null, HEK-293T KPTN-null, MEFs Npc1+/+, and MEFs Npc1−/− cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and 2 mM L-glutamine. Human NPC1WT (GM23151) and NPC1mut fibroblasts (GM03123) were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories in full compliance with the Office for Human Research Protections, Department of Health and Human Services (“DHHS”) regulations. The statement of research intent and the signed MTA were submitted and approved by the Coriell Institutional Review Board for use of patient cells in this study. Human fibroblasts were grown in DMEM with 15% fetal bovine serum. All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. They were free of mycoplasma contamination, and routinely checked using MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, LT07–318) and Hoechst staining.

Plasmids, viruses and stable cell lines

The pLKO.1 lentiviral vector (TRC, Broad institute) was used to express the shRNA against the proteins of interest: OSBP, TRCN0000155752 | ORP8, TRCN0000147289 | ORP11, TRCN0000161454 | ORP5, TRCN0000180915 | VAPA, TRCN0000029130 | VAPB, TRCN0000151599 | STARD3, TRCN0000150515 | LUCIFERASE as non-targeting control, TRCN0000072243. In cases where indicated, a doxycycline-inducible shRNA system via Tet-pLKO-puro (Addgene #21915) was used to silence OSBP using doxycycline.

For protein expression, cDNA encoding proteins were cloned into the pLJM1 lentiviral vector carrying a FLAG tag or a FLAG tag followed by a GFP marker accordingly. OSBP cDNA was codon optimized and its variants (R108L, F359A/F360A, H522A/H523A, ΔELSK: deletion of 430–433 aa, K736A) were generated via Agilent QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis. As for organelle-targeted OSBP truncations, the coding sequence of p18 N-terminal 1–39 aa was inserted to the N terminus of OSBP ΔPH cDNA to generate Lyso-ΔPH-OSBP; Golgi-ΔPH was generated by fusing the coding sequence of Giantin C-terminal 3131–3259 aa to the C terminus of ΔPH; Mito-ΔPH was made by inserting the coding sequence of TOM20 1–145 aa to the N terminus of ΔPH; ER-ΔPH was generated by inserting the coding sequence of ORP8 C-terminal transmembrane region 860–887 aa to the C terminus of ΔPH.

GFP-P4M and mCherry-P4M cDNAs were obtained from Gerry Hammond and cloned into pLJM1 vectors. The scSac1 catalytic domain cDNAs (WT and C389S, catalytically inactive) were obtained from Sergio Grinstein, subjected to human codon optimization, and fused into the C terminus of Lyso-FLAG-GFP in pLJM1 background. As for pGEX-KG-D4H*-mCherry, D4H-mCherry cDNA was obtained from Gregory D. Fairn and inserted into the pGEX-KG vector. The construct was renamed to D4H*-mCherry as two mutations including Y415A and A463W were introduced to improve the sensitivity of cholesterol binding, in addition to the D434S of the original D4H cDNA. The autophagic flux reporter pMRX-IP-GFP-LC3-RFP-LC3ΔG was from Addgene, #84572.

All proteins were either acutely knockdown or stably expressed through lentiviral infection. Lentiviruses were produced by co-transfecting HEK293T cells with lentiviral expression/shRNA cassette and packaging plasmids (pMD2.5G, Addgene #12259 and psPAX2, Addgene #12260) using the calcium phosphate transfection method. Viral supernatant was collected 24 hours after transfection, centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 minutes and filtered with 0.45 μm filter. The viruses were further concentrated using Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech, 631231) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Target cells were plated in 6-well plates with 8 μg/ml polybrene (Millipore, TR-1003-G) and incubated with virus containing media for 24 hours. After removal of viruses, cells were supplemented with fresh media containing 2 μg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem, 540411). Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting and fluorescence microscopy.

For generation of ORP1L knockout cells, guide RNA sequence targeting human OSBPL1A exon 2 (AATCACTTCATTCCTCGCCA) was cloned into lentiCRISPRv2 vector (Addgene # #52961). HEK-293T cells were infected with viral supernatants generated from lentiCRISPRv2 and selected with puromycin for 2 days. Clonal lines were subsequently performed by limiting dilution and validated by immunoblot analysis of ORP1L expression.

Cholesterol starvation/stimulation

HEK-293T cells in culture dishes were rinsed with serum-free media and incubated in 0.5% methyl-beta cyclodextrin (MCD) supplemented with 0.5% lipid-depleted serum (LDS) for 2 hours and, where indicated, stimulated with DMEM supplemented with 0.1% MCD and 0.5% LDS, and 50 μM cholesterol for 2 hours 7. LDS was prepared as described 64

Cell lysis and immunoprecipitation

Cells were rinsed with cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 4 mM EDTA, 40 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, and 1 tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitors per 50 ml). Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 17,000 g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Cell lysate samples were prepared by addition of 5X sample buffer, heated at 70 °C for 10 minutes, resolved by either 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels, and analyzed by immunoblotting.

For FLAG immunoprecipitations, 25 μL of a well-mixed 50% slurry of anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma, A2220) was added to each lysate (1 mg/ml) and incubated at 4 °C in a shaker for 2 hours. Immunoprecipitates were washed five times, twice with lysis buffer and thrice with lysis buffer with 500 mM NaCl. Immunoprecipitated proteins were denatured by addition of 50 μL of 2X urea sample buffer and heating to 37 °C for 15 minutes, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence

HEK-293T or HEK-293A cells were seeded on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips in 6-well plates (35 mm diameter/well), at 300,000–500,000 cells/well and allowed to attach overnight. On the following day, cells were subjected to sterol depletion and restimulation, where indicated, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes at room temperature. The coverslips were rinsed twice with PBS and cells were permeabilized with 0.1% (w/v) saponin in PBS for 10 minutes. After rinsing twice with PBS, the slides were incubated with primary antibodies in 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 017–000-121) for 1 hour at room temperature, rinsed four times with PBS, and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies derived from goat or donkey (Life Technologies, diluted 1:400 in 5% normal donkey serum, PBS) for 45 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After washing four times with PBS and one time with deionized water, the coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, 0100–01) and imaged on a spinning disk confocal system built upon a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with Andor Zyla-4.5 sCMOS camera.

Live-cell imaging of PI4P distribution

Cells expressing PI4P fluorescent reporter (either GFP-P4M or mCherry-P4M) were seeded on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTeK, P35GC-1.5–14-C), allowed to attach overnight, and imaged on a spinning disk microscope. Prior to imaging, cells were transferred to imaging buffer containing 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, and 5 mM D-glucose with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH.

Co-localization analysis

For quantification of cells with the phenotype of interest, 20 to 25 non-overlapping whole-field images were randomly acquired throughout the slide of each sample. All the RAW images were exported from the Andor iQ3 Imaging Software version 3.3.1 (Andor Technology, Oxford Instruments). The Fiji Software version 1.51j (ImageJ, NIH) was used to quantify the fluorescence intensity (https://fiji.sc). To determine the co-localization of mTOR, OSBP, or p62 with LAMP2-positive lysosomes, or co-labeling of D4H*-labeled vesicles with the intracellular filipin deposits, individual channels were segmented to identify bona fide vesicles using a binary mask via an intensity thresholding function. Co-localization between the respective channels (mTOR / LAMP2, OSBP / LAMP2, p62 / LAMP2, or D4H* / filipin) was measured using the AND function and plotted as the fraction of LAMP2-positive (or filipin-positive) vesicles that are also positive for mTOR (or OSBP, p62, D4H*). In cases where indicated, co-localization data was normalized to the reference group for multiple comparisons. In general, ten fields of view per condition except otherwise stated were subjected to thresholding for quantification. The number of cells included for analysis per condition and the number of independent experiments were indicated in the figure legends accordingly.

Lysosome immunoprecipitation

Lysosomes carrying Tmem192-mRFP-3xHA were purified as described previously 7, 32. Confluent HEK293T cells stably expressing Tmem192-mRFP-3xHA in a 15-cm culture dish were scraped in chilled PBS and collected by centrifugation at 300 g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Cells were re-suspended, lysed using a 23G syringe in KPBS buffer (136 mM KCl, 10 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.25), and spun at 700 g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The post nuclear supernatant (PNS) was then incubated with 50 μL of anti-HA magnetic beads, washed in KPBS buffer, for 5 minutes at 4 °C. Lysosome-bound beads were then washed three times in KPBS buffer, re-suspended in 2X urea sample buffer for immunoblotting, or extracted of lipids with methanol and ethyl acetate for lysosomal cholesterol measurement.

Lysosomal cholesterol measurement using mass spectrometry

The lysosomal samples were extracted from anti-HA magnetic beads with methanol and ethyl acetate with d7-cholesterol (2 μg per sample), and further derivatized with nicotinic acid to improve the mass spectrometric detection sensitivity of cholesterol. Measurement of cholesterol was performed with a Shimadzu 10A HPLC system and a Shimadzu SIL-20AC HT auto-sampler coupled to a Thermo Scientific TSQ Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Data processing was conducted with Xcalibur™ Software version 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A quality control (QC) sample was prepared by pooling the aliquots of the study samples and was used to monitor the instrument stability. The QC was injected six times in the beginning to stabilize the instrument and was injected every four study samples to monitor the instrument performance. The data was accepted if the coefficient variance (CV) of cholesterol in QC sample was < 15%. The data was reported as the peak area ratio of cholesterol to d7-cholesterol.

Whole-cell lipidome analysis

HEK-293T cells cultured in 6-well plates were depleted of OSBP by doxycycline-induced shRNA, washed twice with PBS, harvested by scraping, and collected by bench-top centrifugation at 1000 g at 4 °C, and cell pellets were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C until metabolome extractions. Lipid metabolites were extracted in 4 mL of a 2:1:1 mixture of chloroform/methanol/Tris buffer with inclusion of internal standards C12:0 dodecylglycerol (10 nmol) and pentadecanoic acid (10 nmol). Organic and aqueous layers were separated by centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 minutes, and the organic layer was collected. The aqueous layer was acidified (for metabolites such as LPA) by adding 0.1% formic acid, followed by the addition of 2 mL of chloroform. The mixture was vortexed, and the organic layers were combined, dried down under liquid nitrogen, and dissolved in 120 μL of chloroform, of which 10 μL was analyzed by both single-reaction monitoring (SRM)-based LC-MS/MS or untargeted LC-MS. LC separation was achieved with a Luna reverse-phase C5 column (50 mm × 4.6 mm with 5 μm diameter particles, Phenomenex). Mobile phase A was composed of a 95:5 ratio of water/methanol, and mobile phase B consisted of 2-propanol, methanol, and water in a 60:35:5 ratio. Solvent modifiers 0.1% formic acid with 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% ammonium hydroxide were used to assist ion formation as well as to improve the LC resolution in both positive and negative ionization modes, respectively. The flow rate for each run started at 0.1 mL/min for 5 minutes, to alleviate backpressure associated with injection of chloroform. The gradient started at 0% B and increased linearly to 100% B over the course of 45 minutes with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, followed by an isocratic gradient of 100% B for 17 minutes at 0.5 mL/min before equilibrating for 8 minutes at 0% B with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

Mass spectrometry analysis was performed with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source on an Agilent 6430 QQQ LC-MS/MS. The capillary voltage was set to 3.0 kV, and the fragmentor voltage was set to 100 V. The drying gas temperature was 350 °C, the drying gas flow rate was 10 L/ min, and the nebulizer pressure was 35 psi. Representative metabolites were quantified by SRM of the transition from precursor to product ions at associated collision energies. Data were normalized to the internal standards, and also external standard curves of metabolite classes against the internal standards and levels were expressed as relative metabolite levels compared to controls. For absolute quantification of cellular cholesterol levels as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4b, serial dilution of free cholesterol, cholesteryl oleate and cholesteryl ester, ranging from 1 mM to 1 nM, was prepared, subjected to 2:1 chloroform:methanol extraction along with appropriate internal standards, and ran through the LC-MS. The ratios of the integrations for cholesterol/C12MAGE, cholesteryl oleate/C12MAGE, choleseteryl ester/C12MAGE were determined respectively and plotted in inverse. A polynomial trend line was fit to the data and the resulting equation was used to calculate the amounts of the lipids at 1 million cells per cell pellet.

Purification of recombinant GST-D4H*-mCherry

GST-fusion D4H*-mCherry was expressed in BL21 Escherichia coli and induced for protein production with 0.4 mM IPTG for 20 hours at 18 °C when the OD600 of bacteria growth reached ~ 0.6. Bacteria pellets were suspended in Buffer A (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT) containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Pierce) and incubated with 0.35 mg/ml lysozyme on ice for 30 minutes. The bacterial lysate was sonicated on ice using an ultrasonic processor Q700 (QSONICA Sonicators) with 12 cycles of a 10-second pulse followed by a 10-second break at 50% amplitude output for 4 minutes. The lysate was treated with 0.5% Triton-X-100 and rocked at 4 °C for 15 minutes. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 17,000 g at 4 °C for 30 minutes. The pre-equilibrated glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) in Buffer A with 0.1% Triton-X-100 were incubated with clear supernatant for 2 hour at 4 °C. GST-fusion D4H*-mCherry proteins were eluted from beads with 25 mM L-glutathione solution in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.8 and 200 mM NaCl. The fractions of the eluate were pooled and filtered using 3K and 30K centrifugal filter units (Amicon Ultra, Millipore) to remove glutathione and concentrate the protein in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 5 mM DTT. The protein solution was then supplemented with 20% sucrose and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The qualities of the recombinant protein of different batches were validated by Coomassie blue staining.

Labeling of cholesterol with GST-D4H*-mCherry and filipin

In situ labeling of cholesterol was performed by adopting a protocol as previously described 16. Cells were plated on fibronectin-coated coverslips, subjected to treatment as indicated, fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes at the room temperature, and permeabilized in a liquid nitrogen bath for 30 seconds. After blocking with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour, the cells were incubated with recombinant GST-D4H*-mCherry (1:100 dilution, 1% BSA in PBS) for 2 hours. The samples were rinsed twice with PBS, re-fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes, incubated with filipin solution (0.5 mg/ml in PBS) for 2 hours, immunostained with LAMP2 or LAMP1, where indicated, and washed four times with PBS. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Fluoromount-G and imaged on a spinning disk confocal microscope.

TopFluor-Cholesterol trafficking

HEK-293T cells stably expressing Tmem192-mRFP-3xHA were incubated with DMEM containing 1.5% LDS, treated with DMSO or 20 nM OSW-1 for 2 hours. A total of 20 nmol/ml TopFluor-cholesterol complexed with 0.1 % MCD in DMEM containing 1.5% LDS was loaded to the cells for 10 min on ice. After rinsing with PBS, cells were incubated at 37 °C, chased at the indicated times, fixed with 4% PFA, and imaged on a spinning disk confocal microscope.

Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) for in situ detection of ER-lysosome contacts

Human NPC1WT and NPC1mut fibroblasts were seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips, fixed with 4% PFA, and subjected to proximity ligation assay according to manufacturer’s protocol (SigmaAldrich, Duolink® In Situ Detection Reagents FarRed, DUO92013). Briefly, after permeabilization with 0.1% saponin, the cells were subjected to blocking, incubation with VAPA and LAMP2 antibodies, either alone or in combination as indicated for 1 hour at room temperature, hybridization with PLA probes, ligation, amplification, and finally Hoechst staining. The number of PLA puncta, indicative of a close apposition between VAPA (ER) and LAMP2 (lysosome), were quantified accordingly as mentioned in the section of co-localization analysis.

Autophagic flux reporter assay

Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEF cells expressing GFP-LC3-RFP-LC3ΔG reporter 49 were generated by retrovirus-mediated transduction. After puromycin selection, cells were seeded in fibronectin-coated 96-well plate at 25,000 cells/well and grown overnight. The cells were then treated with either 20 nM OSW-1, 100 nM Bafilomyin A1, or 250 nM Torin1 for 24 hours, respectively, and fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 15 minutes. The fluorescence intensity of GFP and RFP per well was measured using a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3, Molecular Devices) with excitation/emission at 488/509 nm and 584/607 nm, respectively.

Statistics and Reproducibility

Data were expressed as mean ± s.d. where indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for group comparisons, where indicated, using the GraphPad Prism version 7.0a (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For box plots, the upper and lower edges of the box indicate the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles) of the data, and the middle line indicates the median, and the whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum. The levels of statistical significance were presented as asterisks and the exact P values were indicated in each figure legend along with the statistical tests, respectively. Experiments in Fig. 8c, Supplementary Fig. 4c and 6h were performed once. All other experiments reported here were performed at least two to three times independently and all attempts at replication were successful with similar results.

Data availability

Mass spectrometry data that support the findings of this study are presented in Supplementary Table 1 and have been deposited in ProteomeXchange with the primary accession code [PXD014733]. Statistics source data for Figs. 1–4, 6–8 and Supplementary Figs. 1–6 are provided in Supplementary Table 2. All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Zoncu Lab for helpful insights; Rushika Perera and Michael Rape for critical reading of the manuscript; Matthew D Shair (Harvard University) for providing us with the OSW-1 compound; Greg Fairn (University of Toronto) for the D4H cholesterol probe cDNA; Gerald Hammond (University of Pittsburgh) and Sergio Grinstein (Hospital for Sick Children) for the P4M reporter and the scSac1 catalytic domain cDNAs; Hiroyuki Arai and Nozomu Kono (University of Tokyo) for the OSBP rabbit polyclonal antibody. C-Y.L. is a recipient of the American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (18POST34070059). This work was supported by the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (1DP2CA195761–01), the Pew-Stewart Scholarship for Cancer Research, the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award, the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation Grant and the Packer Wentz Endowment to R.Z., a National Institutes of Health R01 HL067773 to D.O.

Footnotes

Competing Interests. R.Z. is a co-founder, consultant and stockholder of Frontier Medicines Corporation. D.K.N. is a co-founder, stock-holder, and scientific adviser for Artris Therapeutics and Frontier Medicines Corporation.

References

- 1.Gatta AT & Levine TP Piecing Together the Patchwork of Contact Sites. Trends in cell biology 27, 214–229 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips MJ & Voeltz GK Structure and function of ER membrane contact sites with other organelles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17, 69–82 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thelen AM & Zoncu R Emerging Roles for the Lysosome in Lipid Metabolism. Trends in cell biology 27, 833–850 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP & Guan KL Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nature cell biology 10, 935–945 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sancak Y et al. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell 141, 290–303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sancak Y et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science 320, 1496–1501 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellano BM et al. Lysosomal cholesterol activates mTORC1 via an SLC38A9-Niemann-Pick C1 signaling complex. Science 355, 1306–1311 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung J, Genau HM & Behrends C Amino Acid-Dependent mTORC1 Regulation by the Lysosomal Membrane Protein SLC38A9. Molecular and cellular biology 35, 2479–2494 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebsamen M et al. SLC38A9 is a component of the lysosomal amino acid sensing machinery that controls mTORC1. Nature 519, 477–481 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S et al. Metabolism. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 347, 188–194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong X et al. Structural Insights into the Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)-Mediated Cholesterol Transfer and Ebola Infection. Cell 165, 1467–1478 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon HJ et al. Structure of N-terminal domain of NPC1 reveals distinct subdomains for binding and transfer of cholesterol. Cell 137, 1213–1224 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Saha P, Li J, Blobel G & Pfeffer SR Clues to the mechanism of cholesterol transfer from the structure of NPC1 middle lumenal domain bound to NPC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 10079–10084 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maxfield FR Role of endosomes and lysosomes in human disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 6, a016931 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radhakrishnan A, Goldstein JL, McDonald JG & Brown MS Switch-like control of SREBP-2 transport triggered by small changes in ER cholesterol: a delicate balance. Cell Metab 8, 512–521 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilhelm LP et al. STARD3 mediates endoplasmic reticulum-to-endosome cholesterol transport at membrane contact sites. Embo J 36, 1412–1433 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Im YJ, Raychaudhuri S, Prinz WA & Hurley JH Structural mechanism for sterol sensing and transport by OSBP-related proteins. Nature 437, 154–158 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong J, Yang H, Yang H, Eom SH & Im YJ Structure of Osh3 reveals a conserved mode of phosphoinositide binding in oxysterol-binding proteins. Structure 21, 1203–1213 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesmin B, Antonny B & Drin G Insights into the mechanisms of sterol transport between organelles. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 70, 3405–3421 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesmin B et al. Sterol transfer, PI4P consumption, and control of membrane lipid order by endogenous OSBP. Embo J 36, 3156–3174 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goto A, Charman M & Ridgway ND Oxysterol-binding Protein Activation at Endoplasmic Reticulum-Golgi Contact Sites Reorganizes Phosphatidylinositol 4-Phosphate Pools. J Biol Chem 291, 1336–1347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong R et al. Endosome-ER Contacts Control Actin Nucleation and Retromer Function through VAP-Dependent Regulation of PI4P. Cell 166, 408–423 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland AA, Chitwood PJ, Phillips MJ & Voeltz GK ER contact sites define the position and timing of endosome fission. Cell 159, 1027–1041 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha N et al. Cholesterol sensor ORP1L contacts the ER protein VAP to control Rab7-RILP-p150 Glued and late endosome positioning. J Cell Biol 185, 1209–1225 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willett R et al. TFEB regulates lysosomal positioning by modulating TMEM55B expression and JIP4 recruitment to lysosomes. Nature communications 8, 1580 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebrand C et al. Late endosome motility depends on lipids via the small GTPase Rab7. Embo J 21, 1289–1300 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maekawa M & Fairn GD Complementary probes reveal that phosphatidylserine is required for the proper transbilayer distribution of cholesterol. Journal of cell science 128, 1422–1433 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loftus SK et al. Murine model of Niemann-Pick C disease: mutation in a cholesterol homeostasis gene. Science 277, 232–235 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar S et al. Impaired autophagy in the lipid-storage disorder Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Cell reports 5, 1302–1315 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu F et al. Identification of NPC1 as the target of U18666A, an inhibitor of lysosomal cholesterol export and Ebola infection. Elife 4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zoncu R et al. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science 334, 678–683 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu-Remaileh M et al. Lysosomal metabolomics reveals V-ATPase- and mTOR-dependent regulation of amino acid efflux from lysosomes. Science 358, 807–813 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgett AW et al. Natural products reveal cancer cell dependence on oxysterol-binding proteins. Nat Chem Biol 7, 639–647 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine TP & Munro S The pleckstrin homology domain of oxysterol-binding protein recognises a determinant specific to Golgi membranes. Current biology : CB 8, 729–739 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridgway ND, Dawson PA, Ho YK, Brown MS & Goldstein JL Translocation of oxysterol binding protein to Golgi apparatus triggered by ligand binding. J Cell Biol 116, 307–319 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su MY et al. Hybrid Structure of the RagA/C-Ragulator mTORC1 Activation Complex. Mol Cell 68, 835–846 e833 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levin R et al. Multiphasic dynamics of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate during phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 28, 128–140 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mesmin B et al. A four-step cycle driven by PI(4)P hydrolysis directs sterol/PI(4)P exchange by the ER-Golgi tether OSBP. Cell 155, 830–843 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammond GR, Machner MP & Balla T A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J Cell Biol 205, 113–126 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perry RJ & Ridgway ND Oxysterol-binding protein and vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein are required for sterol-dependent activation of the ceramide transport protein. Mol Biol Cell 17, 2604–2616 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bar-Peled L et al. A Tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the Rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 340, 1100–1106 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panchaud N, Peli-Gulli MP & De Virgilio C Amino acid deprivation inhibits TORC1 through a GTPase-activating protein complex for the Rag family GTPase Gtr1. Science signaling 6, ra42 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfson RL et al. KICSTOR recruits GATOR1 to the lysosome and is necessary for nutrients to regulate mTORC1. Nature 543, 438–442 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menon S et al. Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell 156, 771–785 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao K & Ridgway ND Oxysterol-Binding Protein-Related Protein 1L Regulates Cholesterol Egress from the Endo-Lysosomal System. Cell reports 19, 1807–1818 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoyer MJ et al. A Novel Class of ER Membrane Proteins Regulates ER-Associated Endosome Fission. Cell 175, 254–265 e214 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ordonez MP et al. Disruption and therapeutic rescue of autophagy in a human neuronal model of Niemann Pick type C1. Hum Mol Genet 21, 2651–2662 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pacheco CD, Kunkel R & Lieberman AP Autophagy in Niemann-Pick C disease is dependent upon Beclin-1 and responsive to lipid trafficking defects. Hum Mol Genet 16, 1495–1503 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaizuka T et al. An Autophagic Flux Probe that Releases an Internal Control. Mol Cell 64, 835–849 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bjorkoy G et al. Monitoring autophagic degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods in enzymology 452, 181–197 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung J et al. INTRACELLULAR TRANSPORT. PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5- and ORP8-mediated ER-plasma membrane contacts. Science 349, 428–432 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du X et al. A role for oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 5 in endosomal cholesterol trafficking. J Cell Biol 192, 121–135 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Du X et al. Oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 5 (ORP5) promotes cell proliferation by activation of mTORC1 signaling. J Biol Chem 293, 3806–3818 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mousley CJ et al. A sterol-binding protein integrates endosomal lipid metabolism with TOR signaling and nitrogen sensing. Cell 148, 702–715 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murley A et al. Sterol transporters at membrane contact sites regulate TORC1 and TORC2 signaling. J Cell Biol 216, 2679–2689 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballabio A & Gieselmann V Lysosomal disorders: from storage to cellular damage. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793, 684–696 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Infante RE et al. NPC2 facilitates bidirectional transfer of cholesterol between NPC1 and lipid bilayers, a step in cholesterol egress from lysosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 15287–15292 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Infante RE & Radhakrishnan A Continuous transport of a small fraction of plasma membrane cholesterol to endoplasmic reticulum regulates total cellular cholesterol. Elife 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toulmay A & Prinz WA Direct imaging reveals stable, micrometer-scale lipid domains that segregate proteins in live cells. J Cell Biol 202, 35–44 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsuji T et al. Niemann-Pick type C proteins promote microautophagy by expanding raft-like membrane domains in the yeast vacuole. Elife 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]