Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to estimate the time of recurrent ischaemic stroke events among the first 3 years of follow-up after hospitalisation discharge.

Study design

A prospective cohort study.

Setting

The research was conducted in the Department of Neurology at a tertiary hospital, Chengdu of China, from January 2010 to June 2016.

Outcome measures

We estimated the restricted mean survival time (RMST) of ischaemic stroke recurrence for the first 3 years after discharge. Basic sociodemographic characteristics and major potential risk factors for recurrence were collected using a semistructured questionnaire. Regression analysis of RMST was used to identify risk factors of recurrent stroke.

Participants

Patients hospitalised with first-ever ischaemic stroke were eligible for this study. Patients with severe cognitive impairment were excluded.

Results

We included 641 surviving patients who were followed up for 3 years. Stroke recurrence occurred in 115 patients, including 16 patients who died of stroke recurrence. The cumulative risk of stroke recurrence rate was 11.51% (9.20%–14.35%) at 1 year, 16.76% (13.96%–20.05%) at 2 years and 20.07% (17.00%–23.61%) at 3 years. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score ≥3 thus resulted in the recurrence time loss, which was 0.22 months (p=0.008) at 6 months, 0.61 months (p=0.004) at 1 year, 1.49 months (p=0.007) at 2 years and 2.46 months (p=0.008) at 3 years. It is similar with the effects of drug adherence after stroke. The recurrence time of patients ≥75 years at 3 years was 2.02 months (p=0.220) less than that of those aged <55 years.

Conclusion

In China, the time of first recurrence varies among different patients with ischaemic stroke. The mRS and the level of drug adherence after stroke are important risk factors of stroke recurrence.

Keywords: stroke medicine, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of this study was the introduction of restricted mean survival time, which is a useful measure, especially in the case that the proportional hazards assumption is not met.

Limitations are that follow-up for outcome variables was performed by telephone interviews rather than by face-to-face contact.

In addition, the possibility that the stroke recurrence information was biased could not be excluded. The recurrence of stroke was gathered from interviews with patients or their proxies, rather than from examinations and reviews of the medical records done by all of us.

Due to the limitation of the reality, it may be inaccurate for using Modified Rankin Scale instead of National Institute of Health Stroke Scale to evaluate the severity of stroke.

Introduction

Stroke is the second most common cause of death,1 the third most common cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide in 2010,2 and the most heavy burden in low-income and middle-income countries.3 4 Ischaemic stroke, mainly secondary to arterial occlusion, accounts for above 85% of all strokes.5 6 In China, the annual stroke mortality rate, approximately 157 per 100 000, has exceeded heart disease to become the leading cause of death and adult disability.7 Stroke survivors are often at significantly increased risk of stroke recurrence,8 even in spite of appropriate treatment, which in turn further increase the risk of disability and death.9 In Chinese population, the recurrent rate (11.2%) remains high.7 With ageing of the population, China is under great pressure to meet further increased demands on the healthcare system due to stroke in the future.10 Secondary stroke prevention remains a top priority in treating patients after the first stroke.11–15

Statements on the risk of stroke recurrence are invariably based on the hazard ratio (HR), which rely on the proportional hazards (PHs) assumption to estimate the treatment effect and implicitly. However, formal verification of this assumption is rarely. Some studies16–18 argued that when the PH assumption is invalid, it is misleading to report the treatment effect through the estimated HR, since it depends on study-specific follow-up time.

Even when PH holds, we are dissatisfied with the HR as a universal summary measure.17 Without appropriate background information about the absolute hazard, the summary ratio fails to convey a more transparent clinical value of a treatment, such as the prolonged survival time.16 Moreover, the precision of the HR estimator depends primarily on the observed number of events, resulting in that confidence intervals (CIs) for the HR estimate can be quite large when the event rates are low for both groups, which ostensibly suggesting that the information is not enough to properly assess the between-group difference.

The mean survival time is another parameter of great interest, which gives the expected time until some events occur. However, the mean survival time is often ill determined beyond a certain range because of the right censored data. The restricted mean survival time (RMST) can be understood as the average survival time over a period of time and can quantify the difference between the survival time caused by different factors, which is less sensitive to right censoring. Moreover, from a practical point of view, one is often interested in the effect of the risk factors. Differences between patients’ RMST of different risk factor can be interpreted as the number of months lost due to the risk factor.16

Therefore, we aimed to conduct a prospective hospital-based study by a cohort of patients of first-ever ischaemic stroke to estimate the time of recurrent ischaemic stroke events among the first 3 years of follow-up after discharge, and introduce a regression analysis of RMST based on pseudo-observation to determine the risk factors, namely assessing the gain or loss in the event-free recurrence time owing to given risk factors.

Materials and methods

Patient and public involvement

The patients and the public were not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Study population

This was a prospective study conducted in the Department of Neurology in No 1 West China Hospital of Sichuan University, the largest tertiary hospital in Sichuan, China. Patients who were diagnosed with first-ever ischaemic stroke by a neurologist according to WHO criteria19 and CT or MRI were eligible for this study. Patients with severe cognitive impairment were excluded. Consecutive enrolment started in January 2010 and ended in June 2016. All participants provided written informed consents.

Study design

Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews at the hospital to collect data at baseline. Basic sociodemographic characteristics and some potential predictors of stroke recurrence were recoded using a standardised and semistructured questionnaire and supplemented by medical records review. Follow-up questionnaires were completed via telephone interviews every 3 months after discharge. We administered the semistructured questionnaires by expert consultation based on the pilot study, and experts of Neurology have reviewed their availability. Previous studies have shown that both the Chinese version of the 3-level EuroQol five dimensions (EQ-5D-3L) and the 12-items Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) Questionnaires are valid measurements for assessing quality of life in Chinese population.20–23 Although this study does not cover the content of quality of life, the reliability and validity of this part of the questionnaire can also reflect the availability of the overall questionnaire to a certain extent. The questionnaires collected information on death, self-dependency (Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score) and stroke recurrence. For subjects who had cognitive or language impairment, proxies were interviewed. The start point of follow-up was the incident date of first-ever stroke, and the endpoint event was the first recurrence or die of recurrence after first-ever stroke. Patients who die of other causes or without stroke recurrent were censored at either the date of death or their last follow-up interview.

Variable definition

After the initial stroke, a subsequent claim with any type of ischaemic stroke diagnosis at readmission was identified as a recurrence. Time between the initial event and recurrent event was calculated in months. If a patient did not have any recurrent stroke within the 3-year study period, he or she was censored and 36 months was used as censored time. As potential predictors of stroke recurrence, the following variables were selected. Demographic factors included age (categorised as <55 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, ≥75 years), gender, marital status, degree of education, occupation and annual household income. We also documented family stroke history, the history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, cardiac vascular disease (CVD) and peripheral vascular disease (PVD), drug adherence after ischaemic stroke, drinking status, smoking status and weekly exercise time before ischaemic stroke.

Poststroke functional status was assessed using the mRS, with a score >2 as meeting the criteria for disability.24 The initial stroke preventive drug prescribed after stroke was considered the index drug. Drug adherence was estimated using the proportion of days covered (PDC), which was calculated by dividing the number of days of index drug supplied by the number of days of observation.25 A PDC ≥80% was considered optimal.26 We made notes of those who added another drug as doctor said and kept them in the adherence cohort. Switching to another drug or discontinued the drug without medical advice was classified as non-adherence. We estimated the drug adherence at their every follow-up interval, categorised it as always (optimal adherence at every interval), never (no optimal adherence happened) and sometimes over their entire study period. The body mass index (BMI) at hospital admission was calculated as the ratio of body weight and squared height, given as kilogram per squared metre in all patients with available weight and height assessment.

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate. In non-normally distributed data, Mann-Whitney U tests were used. Unadjusted statistical analyses were performed using χ2 analysis for dichotomous results. To identify predictors associated with recurrence time within 3-year follow-up, generalised linear regression analysis of RMST based on pseudo-observation was performed. All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was determined at α level of 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA 13 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA).

The method is based on the pseudo-values from a jackknife statistics constructed from integrated Kaplan-Meier estimators for the probability in question.27 These pseudo-values are used as outcome variables in a generalised estimating equation to obtain estimates of model parameters. And in cases where this estimator is adequate, regression analysis based on pseudo-observations turned out to work well.28 We can interpret the RMST difference as the mean event-free survival time up to a prespecified, clinically important point16 29 and robustness of the estimator to the PHs assumption.17

Results

Out of 764 patients with ischaemic stroke who met the study inclusion criteria at baseline, 641 surviving patients were all followed up to 3 years.

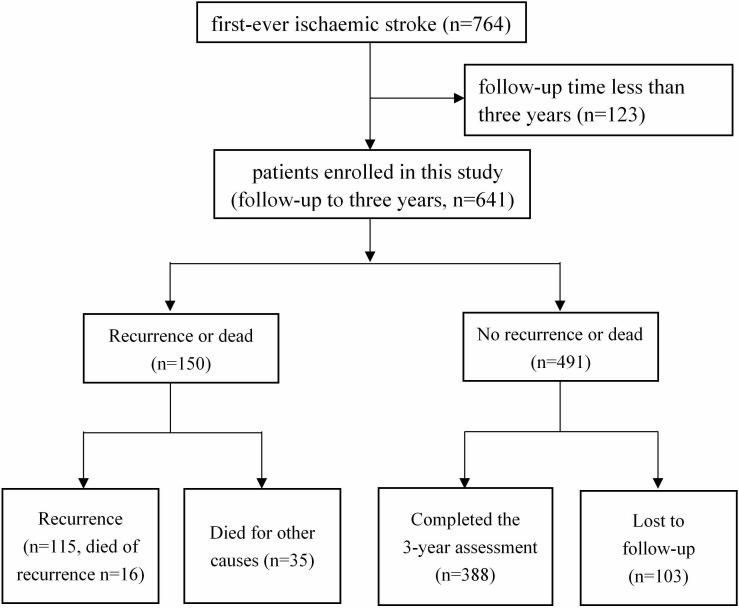

Within 3 years after discharge, 115 recurrent strokes were documented including 16 patients died of stroke recurrence. Four hundred and ninety-one patients were not recurrent or dead within 3 years, of whom 278 patients completed the 3-year assessment, 110 patients did not complete it but we could acquire the recurrence information from later follow-up, and we did not obtain 103 patients any information at all, namely that they were lost to follow-up. Figure 1 shows how we obtained our cohort.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the recruitment.

As summarised in table 1, the study population was primarily male (59.91%), Han (97.04%), married/cohabited (87.36%), retired (42.90%), BMI <25 (65.05%) and most commonly had hypertension (63.34%). The mean±SD age of the cohort was 61.8±12.6 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without stroke recurrence

| Stroke recurrence (n=115) |

No recurrence (n=526) |

P value* | |

| Demographics (%) | |||

| Age, median (IQR), year | 65 (57–75) | 62 (52–71) | 0.002 |

| Age group | 0.007 | ||

| <55 years | 20 (17.5) | 146 (28.4) | |

| 55–64 years | 35 (30.7) | 148 (28.7) | |

| 65–74 years | 29 (25.4) | 146 (28.4) | |

| ≥75 years | 30 (26.3) | 75 (14.6) | |

| Male | 63 (54.8) | 321 (61.0) | 0.248 |

| Han nationality | 113 (98.3) | 509 (96.8) | 0.550 |

| Married/cohabited | 101 (87.8) | 459 (87.3) | 0.869 |

| Occupation | 0.068 | ||

| Farmer | 28 (24.4) | 134 (25.5) | |

| No-farmer worker | 19 (16.5) | 143 (27.2) | |

| Unemployed | 8 (7.0) | 34 (6.5) | |

| Retired | 60 (52.2) | 215 (40.9) | |

| Education | 0.393 | ||

| Primary school and below | 47 (40.9) | 194 (37.2) | |

| Middle school | 24 (20.9) | 141 (27.0) | |

| High school and above | 44 (38.3) | 187 (35.8) | |

| Annual family income (RMB) | 0.608 | ||

| <20 000 | 46 (40.4) | 187 (36.2) | |

| 20000–40 000 | 40 (35.1) | 181 (35.1) | |

| >40 000 | 28 (24.6) | 148 (28.7) | |

| BMI, mean±SD | 23.6±3.8 | 23.6±3.7 | |

| BMI | 0.965 | ||

| <25 | 73 (66.4) | 344 (66.7) | |

| 25–30 | 31 (28.2) | 147 (28.5) | |

| ≥30 | 6 (5.4) | 25 (4.8) | |

| Risk factors and medical history (%) | |||

| Stroke family history | 22 (19.1) | 106 (20.2) | 0.804 |

| Hypertension | 73 (63.5) | 333 (63.3) | 0.973 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (27.8) | 143 (27.2) | 0.889 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 42 (36.5) | 199 (37.8) | 0.770 |

| CVD | 36 (31.3) | 120 (22.8) | 0.055 |

| PVD | 3 (2.6) | 14 (2.7) | 0.974 |

| mRS at 3 months | 0.015 | ||

| 0–2 | 63 (54.8) | 351 (66.7) | |

| 3–5 | 52 (45.2) | 175 (33.3) | |

| Drug adherence after stroke | <0.001 | ||

| Always | 36 (31.3) | 301 (57.2) | |

| Never | 21 (18.3) | 59 (11.2) | |

| Sometimes | 58 (50.4) | 166 (31.6) | |

| Smoking status | 0.086 | ||

| Non-smoker | 80 (69.6) | 310 (58.9) | |

| Current-smoker | 23 (20.0) | 155 (29.5) | |

| Ex-smoker | 12 (10.4) | 61 (11.6) | |

| Drink | 32 (27.8) | 190 (36.1) | 0.090 |

| Exercise | 56 (48.7) | 217 (41.3) | 0.144 |

The total numbers of missing values by risk factors are the following: age 12, education 4, annual family income 11, BMI 15 and hyperlipidaemia 2.

*Comparison of proportions with versus without recurrence using χ2 test.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiac vascular disease; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Recurrence rates of stroke

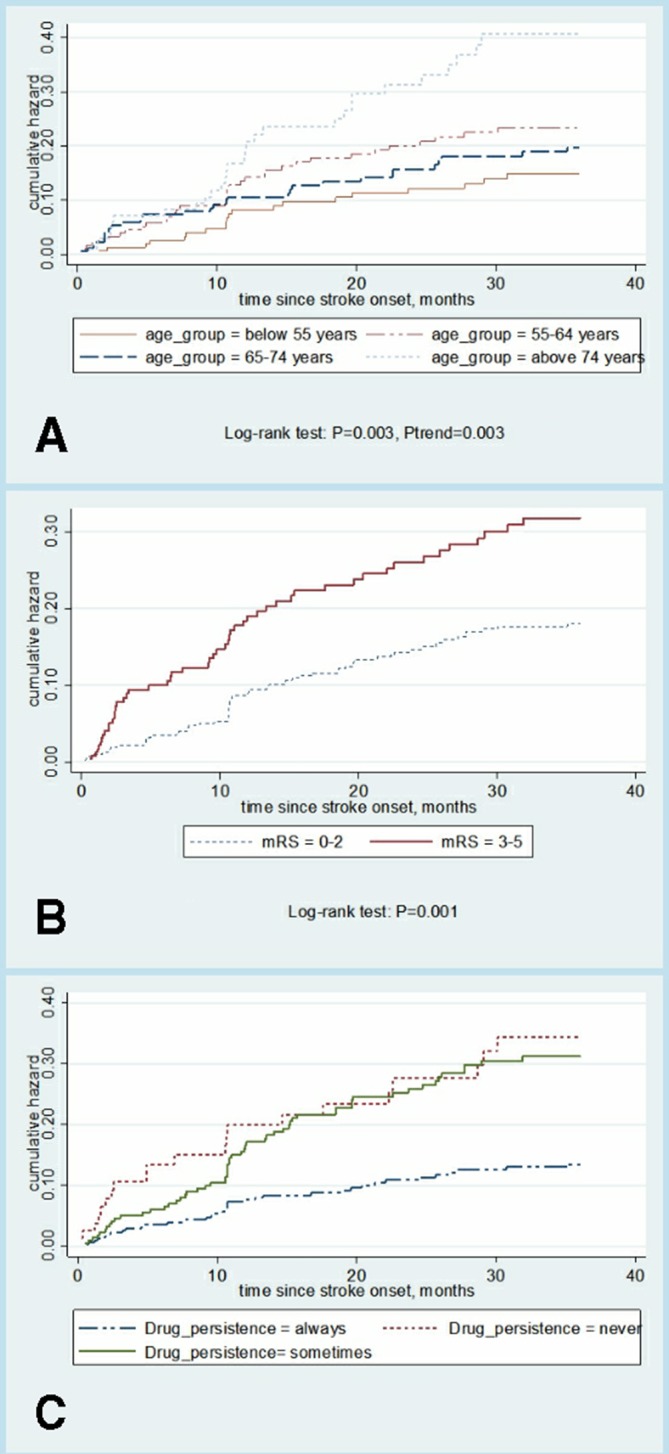

Within 3 years, 115 recurrent strokes after the first-ever ischaemic stroke were documented. The cumulative risk of stroke recurrence was 11.51% (9.20%–14.35%) at 1 year, 16.76% (13.96%–20.05%) at 2 years and 20.07% (17.00%–23.61%) at 3 years. The 3-year cumulative hazard for recurrence by different levels of three risk factors were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analysis (figure 2A–C).

Figure 2.

(A–C) Cumulative risk of stroke recurrence. mRS, Modified Rankin Scale.

Recurrence predictors

mRS and drug adherence after stroke remained significantly associated with time of stroke recurrence in a regression analysis of RMST based on pseudo-observation. Table 2 shows the adjusted coefficient for relevant risk factors of stroke recurrence. RMST differences between different characteristics of patients with other risk factors in control can be interpreted as the number of months lost due to this characteristic. mRS ≥3 thus resulted in the stroke recurrence time loss, which was 0.22 months (p=0.008) at 6 months, 0.61 months (p=0.004) at 1 year, 1.49 months (p=0.007) at 2 years and 2.46 months (p=0.008) at 3 years. With the observation time increased, the RMST difference increased. Compared with the patients who always adhere to medication prescription, those never had RMST decline of 2.14 months and those sometimes had 1.73 months over the next 2 years. The never and sometimes adherence over the next 3 years pushes recurrence time point earlier to 4.21 months and 4.15 months relatively. The recurrence time of patients aged ≥75 years at 3 years was 2.02 months (p=0.220) less than that of those aged <55 years. With CVD, the recurrence time was 2.03 months less than those without, though even not reached a significant difference (p=0.070).

Table 2.

Influence of various predictors on recurrence time of first-ever stroke

| 6-month recurrence | 1-year recurrence | 2-year recurrence | 3-year recurrence | |||||

| β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age group | ||||||||

| <55 years | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| 55–64 years | −0.14 (−0.33 to 0.05) | 0.146 | −0.36 (−0.86 to 0.14) | 0.155 | −0.81 (−2.19 to 0.56) | 0.247 | −1.48 (−3.81 to 0.84) | 0.212 |

| 65–74 years | −0.15 (−0.37 to 0.07) | 0.193 | −0.28 (−0.85 to 0.30) | 0.346 | 0.01 (−1.53 to 1.54) | 0.995 | 0.17 (−2.44 to 2.78) | 0.899 |

| ≥75 years | −0.10 (−0.39 to 0.18) | 0.475 | −0.23 (−0.94 to 0.48) | 0.519 | −0.67 (−2.54 to 1.21) | 0.484 | −2.02 (−5.24 to 1.20) | 0.220 |

| CVD | ||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | −0.18 (−0.39 to 0.03) | 0.083 | −0.47 (−0.99 to 0.05) | 0.075 | −1.29 (-2.58 to 0.01) | 0.052 | −2.03 (-4.23 to 0.17) | 0.070 |

| mRS at 3 months | ||||||||

| 0–2 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| ≥3 | −0.22 (−0.38 to 0.06) | 0.008* | −0.61 (−1.03 to–0.19) | 0.004* | −1.49 (−2.57 to 0.41) | 0.007* | −2.46 (−4.28 to 0.65) | 0.008* |

| Drug adherence after stroke | ||||||||

| Always | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Never | −0.17 (−0.38 to 0.04) | 0.119 | −0.55 (−1.18 to 0.07) | 0.083 | −2.14 (−3.93 to 0.36) | 0.019* | −4.21 (−7.18 to 1.26) | 0.005* |

| Sometimes | −0.13 (−0.36 to 0.09) | 0.245 | −0.20 (−0.60 to 0.20) | 0.337 | − 1.73 (−2.84 to 0.62) | 0.002* | − 4.15 (−6.07 to 2.23) | <0.001* |

Adjusted for sex, BMI, occupation, annual family income, smoking status, drinking, exercise, PVD.

*Bold values with "*" indicate the significant risk factors.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiac vascular disease; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Discussion

In this study, the RMST difference for stroke recurrence up to 3 years after initial ischaemic stroke was estimated. The results showed that in a 3-year follow-up period, 17.94% of the patients had suffered from an ischaemic stroke recurrence; moreover, 0.16% of patients died as a consequence of the recurrence. MRS and drug adherence after stroke were found to have significant roles in predicting stroke recurrence up to 3 years.

This study found that the cumulative risk of recurrence was 11.51% (9.20%–14.35%) at 1 year, 16.76% (13.96%–20.05%) at 2 years and 20.07% (17.00%–23.61%) at 3 years. At 1 year, the annual risk of stroke recurrence reported in many studies is widely ranging from 4% in Perth, Western Australia,30 8.0% in South Carolina,31 to 17.7% in China.32 Our result 11.51% is within the range described above. Studies differ in the study population. Yilong Wang et al enrolled patients with consecutive stroke (≥18 years) in South Carolina within 14 days after stroke onset. In our study, we excluded patients with severe cognitive impairment at baseline, in which population the stroke recurrence rate was higher.33 By 3 years, the risk of stroke recurrence reported in other studies lies between 14.1% in South London Stroke Register34 and 20.80% in control community of Beijing, China,35 close to 20.07% in this study. Whereas more than 90% of residents in the Beijing intervention communities were influenced by the health education and promotion implemented, thus leading to a reduction of stroke recurrence rate of nearly 12%.35

RMST is a useful measure, especially in the case that the PHs assumption is not met, but it is still rarely used in neurology. Comparison of covariates is more clearly interpreted as a quantity of months gained or lost with the RMST than as a survival probability or HR. Taking the RMST of the patients into account allows us to discuss various ways of presenting the results.

Omori et al33 followed up to 1087 first-time ischaemic stroke survivors and found that the higher mRS score of discharge (the more severe the condition) patients had, the higher risk of recurrence patients would have. The data agreed and extended previous studies by reporting an inverse relation between mRS, recurrence rate and time difference at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years and 3 years. We have tried to evaluate patients’ disability level in hospital, for the time span of evaluation is very large and mRS at the time of discharge correlated with the disability level after discharge,33 so we just examined the effect of mRS at 3 months after discharge on stroke recurrence. A small difference in 3-month disability leads to important differences in long-term recurrence. Patients with ischaemic stroke with mRS at 3 months ≥3 may be told that their stroke recurrence time over the next 6 months will be shorten by 0.22 months, over the next 1 year shorten by 0.61 months, over the next 2 years shorten by 1.49 months, over the next 3 years shorten by 2.46 months, compared with those patients with mRS at 3 months <3. These results suggested that the impact of mRS may be more obvious over a longer period of time. Researches of Kawajiri et al36–38 indicate that physical activity (PA) which is assessed by maximum walking speed at discharge may predict future vascular events in mild ischaemic stroke (MIS), and PA-related factors measured during hospitalisation are likely to predict stroke or cardiovascular events after MIS. Because of the disability, those patients with mRS at 3 months ≥3 may show longer time of lying in bed, sitting, lack of exercise, thus lead to lower PA. This may promote the occurrence of cardiovascular events after stroke. As mRS was a predictive indicator for stroke recurrence, persistent long-term care for patients poststroke, especially for patients with low functional level or severe disability, comes to be more important.33

Low adherence to initial stroke preventive medication taken after the first-ever ischaemic stroke is a significant risk factor for recurrence time. When drug adherence was never or sometimes, the survival curve crossed and always adherence had the lowest recurrence rate. Also, for this reason, we choose the RMST difference to explore the related factors associated with time of stroke recurrence. This study measured adherence to specific pill prescription, including antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants. For the reason that the RMST difference could be proposed to explain the association between high adherence and lengthened recurrence time, we may consider great antithrombotic effects and also that patients with high adherence to antithrombotic therapy are more likely to adhere to other recommended treatments, such as antidiabetic agents. Unfortunately, we failed to adjust all those covariates because of lacking data, in the next future, we can analyse these medications’ effect separately and mutually.

One of the strengths of this study was the introduction of RMST, which is comparable to PH in detecting differences between arms when hazards are proportional, but better when hazards are not proportional.17 Based on pseudo-observations, taking the RMST difference into account allows us to discuss various ways of presenting the results and it is easy to interpret for clinicians. Nonetheless, the results of this study must be discussed while bearing in mind the following limitations. First, follow-up for outcome variables was performed by telephone interviews rather than by face-to-face contact. To minimise the impact of this factor on our results, the follow-up was managed centrally and performed by specially trained interviewers using a structured interview protocol. It has been demonstrated previously, thus the use of structured interviews can improve the validity of the results39 and a centrally managed interviewing procedure may reduce bias and inter-rater variability.40 Moreover, studies on the reliability of structured telephone interviews have confirmed a high agreement with face-to-face assessments.41 Next, the possibility that the stroke recurrence information was biased could not be excluded. The recurrence of stroke was gathered from interviews with patients or their proxies, rather than from examinations and reviews of the medical records done by all of us. Patients who reported that they had a stroke recurrence usually went to the hospital for medical diagnosis after the onset of symptoms. Hence, this part of information is considered to be correct, to a certain extent, and it is still applicable.

After the first-ever stroke occurrence, the stroke recurrence rate is expected to rise with the proportion of elderly population increasing. Various factors were assumed to affect the recurrence of stroke, in which the disability level of patients discharged after 3 months evaluated by mRS and drug adherence throughout the course of treatment appear to be important predictors of recurrence. Providing estimates based on months gained or lost of expected RMST may improve the accuracy of the stroke recurrence estimates that influences clinical decisions and advice given to patients. Therefore, adequate disease control and risk factor management from early stroke onset are required to prevent the recurrence of stroke. Further research is needed to evaluate whether RMST improves patients’ understanding and influences treatment decision.42

Conclusions

Though difficult to predict with absolute certainty when stroke will recur, estimating based on months gained or lost of RMST may improve the understanding of the prognostic estimates which may influence clinical decisions and advice given to patients. In China, the time of first recurrence varies among different patients with ischaemic stroke. The mRS and the level of drug adherence after stroke are important risk factors of stroke recurrence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CZ and MZ conceived and designed the study and supervised the process of data analysis and preparation of the manuscript. PZ, BL, JW and ML helped to data entry, data cleaning, prepared the statistical analysis plan and interpret the results and the discussion of the manuscript. QZ, YL and LZ helped to collect data and prepare the materials and methods of the manuscript. JZ, QY and KY were involved in all aspects of data acquisition, management analysis and manuscript preparation.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 81673273 and 30600511).

Competing interests: There are no financial or other interests to declare, and all authors agree to the publication of the manuscript.

Patient and public involvement statement: The patients and the public were not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethical committees of School of Public Health, Huaxi Medical College, Sichuan University China (2009A50).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

References

- 1. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet 2014;383:245–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61953-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee M, Wu Y-L, Ovbiagele B. Trends in incident and recurrent rates of first-ever ischemic stroke in Taiwan between 2000 and 2011. J Stroke 2016;18:60–5. 10.5853/jos.2015.01326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:e28–92. 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warlow C, Sudlow C, Dennis M, et al. Stroke. Lancet 2003;362:1211–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14544-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu L, Wang D, Wong KSL, et al. Stroke and stroke care in China: huge burden, significant workload, and a national priority. Stroke 2011;42:3651–4. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boysen G, Truelsen T. Prevention of recurrent stroke. Neurol Sci 2000;21:67–72. 10.1007/s100720070098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Putaala J, Haapaniemi E, Metso AJ, et al. Recurrent ischemic events in young adults after first-ever ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol 2010;68:661–71. 10.1002/ana.22091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sundberg G, Bagust A, Terént A. A model for costs of stroke services. Health Policy 2003;63:81–94. 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00055-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shih C-C, Liao C-C, Sun M-F, et al. A retrospective cohort study comparing stroke recurrence rate in ischemic stroke patients with and without acupuncture treatment. Medicine 2015;94:e1572 10.1097/MD.0000000000001572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldstein LB, Rothwell PM. Advances in prevention and health services delivery 2010-2011. Stroke 2012;43:298–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.642678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hong K-S, Yegiaian S, Lee M, et al. Declining stroke and vascular event recurrence rates in secondary prevention trials over the past 50 years and consequences for current trial design. Circulation 2011;123:2111–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abbott AL. Medical (nonsurgical) intervention alone is now best for prevention of stroke associated with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis: results of a systematic review and analysis. Stroke 2009;40:e573–83. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McArthur KS, Quinn TJ, Higgins P, et al. Post-Acute care and secondary prevention after ischaemic stroke. BMJ 2011;342:d2083 10.1136/bmj.d2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uno H, Claggett B, Tian L, et al. Moving beyond the hazard ratio in quantifying the between-group difference in survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2380–5. 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Royston P, Parmar MKB. Restricted mean survival time: an alternative to the hazard ratio for the design and analysis of randomized trials with a time-to-event outcome. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:152 10.1186/1471-2288-13-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Royston P, Parmar MKB. The use of restricted mean survival time to estimate the treatment effect in randomized clinical trials when the proportional hazards assumption is in doubt. Stat Med 2011;30:2409–21. 10.1002/sim.4274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kunitz SC, Gross CR, Heyman A, et al. The pilot stroke data bank: definition, design, and data. Stroke 1984;15:740–6. 10.1161/01.STR.15.4.740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lam CLK, Tse EYY, Gandek B. Is the standard SF-12 health survey valid and equivalent for a Chinese population? Qual Life Res 2005;14:539–47. 10.1007/s11136-004-0704-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo X, George ML, Kakouras I, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the short form 12-Item survey (SF-12) in patients with back pain. Spine 2003;28:1739–45. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083169.58671.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ran MD, Liu BQ, Chen LM, et al. [Assessing quality of life of patients with stroke using EQ-5D and SF-12]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2015;46:94–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Du X-D, Zhu P, Li M-E, et al. [Health utility of patient with Stoke measured by EQ-5D and SF-6D]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2018;49:252–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uyttenboogaart M, Stewart RE, Vroomen PCAJ, et al. Optimizing cutoff scores for the Barthel index and the modified Rankin scale for defining outcome in acute stroke trials. Stroke 2005;36:1984–7. 10.1161/01.STR.0000177872.87960.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evans C, Marrie RA, Zhu F, et al. Adherence and persistence to drug therapies for multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;8:78–85. 10.1016/j.msard.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, et al. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2303–10. 10.1185/03007990903126833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andersen PK, Klein JP. Regression analysis for multistate models based on a Pseudo-value approach, with applications to bone marrow transplantation studies. Scand J Stat 2007;34:3–16. 10.1111/j.1467-9469.2006.00526.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersen PK, Hansen MG, Klein JP. Regression analysis of restricted mean survival time based on pseudo-observations. Lifetime Data Anal 2004;10:335–50. 10.1007/s10985-004-4771-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uno H, Wittes J, Fu H, et al. Alternatives to hazard ratios for comparing the efficacy or safety of therapies in Noninferiority studies. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:127–34. 10.7326/M14-1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hardie K, Hankey GJ, Jamrozik K, et al. Ten-Year risk of first recurrent stroke and disability after first-ever stroke in the Perth community stroke study. Stroke 2004;35:731–5. 10.1161/01.STR.0000116183.50167.D9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Feng W, Hendry RM, Adams RJ. Risk of recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, or death in hospitalized stroke patients. Neurology 2010;74:588–93. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cff776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Xu J, Zhao X, et al. Association of hypertension with stroke recurrence depends on ischemic stroke subtype. Stroke 2013;44:1232–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Omori T, Kawagoe M, Moriyama M, et al. Multifactorial analysis of factors affecting recurrence of stroke in Japan. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:NP333–40. 10.1177/1010539512441821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hillen T, Coshall C, Tilling K, et al. Cause of stroke recurrence is multifactorial: patterns, risk factors, and outcomes of stroke recurrence in the South London stroke register. Stroke 2003;34:1457–63. 10.1161/01.STR.0000072985.24967.7F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang B, Wang WZ, Wu SP, et al. Effects of urban community intervention on 3-year survival and recurrence after first-ever stroke. Stroke 2004;35:1242–7. 10.1161/01.STR.0000128417.88694.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kawajiri H, Mishina H, Asano S, et al. Maximum walking speed at discharge could be a prognostic factor for vascular events in patients with mild stroke: a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:230–8. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kono Y, Kawajiri H, Kamisaka K, et al. Predictive impact of daily physical activity on new vascular events in patients with mild ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke 2015;10:219–23. 10.1111/ijs.12392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–236. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Newcommon NJ, Green TL, Haley E, et al. Improving the assessment of outcomes in stroke: use of a structured interview to assign grades on the modified Rankin scale. Stroke 2003;34:377–8. 10.1161/01.STR.0000055766.99908.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Merino José G., Lattimore SU, Warach S. Telephone assessment of stroke outcome is reliable. Stroke 2005;36:232–3. 10.1161/01.STR.0000153055.43138.2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Janssen PM, Visser NA, Dorhout Mees SM, et al. Comparison of telephone and face-to-face assessment of the modified Rankin scale. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;29:137–9. 10.1159/000262309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim DH, Uno H, Wei L-J. Restricted mean survival time as a measure to interpret clinical trial results. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:1179–80. 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.