Abstract

Introduction

In Israel, 12% of adolescents have mental health conditions. Approximately 600 adolescents with mental health conditions are hospitalised each year and about 40% of them return to the hospital and are thus cut-off from their daily lives and peers in the community. In contrast to adults, adolescents with mental health conditions in Israel are not eligible by law for rehabilitation services. Thus, the overarching goal of this qualitative study is to identify best practices for the implementation of community-based psychosocial rehabilitation programme for this population, by examining the first such programme in Israel. Amitim for Youth, which was established in 2018 by the Israel Association of Community Centers in cooperation with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and the Special Projects Fund of the National Insurance Institute.

Methods and analysis

Qualitative data will be collected through in depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups. To identify themes and patterns in the data, a six-stage reflexive thematic analysis approach will be used. A triangulation procedure will be conducted to strengthen the validity of the findings collected by different methods and from various stakeholders in the programme: the programme’s decision-makers, programme team members, the intended beneficiaries and referring mental health professionals. To insure the trustworthiness of the findings, three strategies will be employed: memo writing, reflexive journaling and member checking.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research in the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences at the University of Haifa (#455–18) and by the Chief Scientist in the Ministry of Education (#10566). All participants will sign an informed consent form and will be guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Data collection will be conducted in the next 2 years (2019 to 2020). After data analysis, the findings will be disseminated via publications.

Keywords: adolescents, youth, psychiatric rehabilitation, mental illness, mental health, recovery, community

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a pioneering study that will examine a community-based psychosocial rehabilitation programme for adolescents with mental health conditions in Israel.

The findings will inform best practices to meet the needs of all stakeholders by addressing potential barriers and facilitators for programme implementation.

The findings may contribute to policy recommendations and legislation relating to adolescent psychiatric rehabilitation.

Recruiting adolescents with mental health conditions may be challenging due to their psychiatric condition.

Introduction

Adolescents with mental health conditions

Adolescence is characterised by physiological, psychological and social changes that are known to be associated with many challenges.1 2 According to Erikson's psychosocial developmental theory,3 adolescents are in the ‘identity versus role confusion’ stage, where they search for personal identity and strive for independence through the exploration of social roles, personal values, beliefs and goals while distancing themselves from their parents. For adolescents with mentalhealth conditions (MHC) (ie, who have a psychiatric diagnosis), this developmental task is even more complex and may lead to a lack of identity formation or a negative identity.2 Adolescents with MHC may also have to deal with maladaptive thoughts, dysregulated emotions and behaviours which may impact their interaction with peers and family members, academic performance and in severe cases may involve loss of contact with reality.4 Therefore, it is important to differentiate between the needs of adolescents who face age-appropriate challenges and adolescents who have MHC.

Another challenge that adolescents with MHC may face is coping with stigma. The mental health literature distinguishes between public stigma and self-stigma.5 Public stigma refers to negative labelling (stereotype, prejudice and discrimination) of a group of people to distance them from society, whereas self-stigma (also termed internalised stigma) refers to the internalisation of those negative labels in a way that changes people’s self-perception.5 While there is ample evidence that adolescents with MHC experience public stigma,6 7 self-stigma is under-investigated and insufficiently understood for adolescents with MHC.8–10 In some studies adolescents' self-stigma has been associated with reduced self-esteem,11 limited social interactions, secrecy, shame12 and less adaptive coping strategies.13 Recent qualitative findings suggest that adolescents’ decisions to disclose their MHC is highly influenced by fear of stigma.14 15 A worldwide meta-analysis study reported that 13% of all adolescents have MHC.16 In Israel, from 1993 to 2016, there was an increase of 130% in the number of children and adolescents who were admitted to psychiatric hospitals. In 2016, 767 adolescents aged 12 to 17 were admitted to Israeli hospitals.17

A legislative bill entitled ‘Rights and Services for Children and Adolescents with Mental Difficulties’ was submitted to the Israeli Knesset for the first time in 2014.18 The purpose of the bill was to:

… ensure the rights of children and adolescents with mental disabilities to rehabilitation and care in the community, in such a way as to provide an appropriate response to their special needs and enable them to integrate into the community as their peers do, while utilising their abilities to the fullest.

The bill stressed that children and adolescents must be provided with services in the community, including leisure activities, care and guidance by counsellors from the field of mental health, and include the provision of information, practical and emotional support and assistance in imparting life and social skills.18 However, this bill has not been passed and adolescents with MHC in Israel thus remain without legislated, State supported rehabilitative psychosocial services in the community.

Aligned with the recovery approach described below, the widely used umbrella term ‘mental health conditions’ (rather than mental illness or psychiatric disorders or disability) was adopted, which is consistent with the United Nations General Assembly 2017 report on Mental Health and Human Rights.19

Services for adolescents with MHC in Israel

Services for adolescents with MHC are different than those for adults, given their needs and because the ‘Rehabilitation in the Community of Persons with Mental Disabilities Law of 2000’ applies only to adults aged 18 and over.20 In Israel, there are three main ministries that provide services to children and adolescents with MHC. The Ministry of Health is responsible for the medical treatment provided by mental health clinics and in psychiatric hospitals. The Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs and Social Services is responsible for out-of-home care (post-hospitalisation boarding schools). The Ministry of Education is responsible for educational services within the school system (providing personalised educational and psychological services), home-schooling and in out-of-home settings. However, the division of responsibility across the ministries is unclear and coordination is poor. Particularly problematic is that there is no centralised database with data on service consumers across the three ministries in Israel that provide services for adolescents with MHC. This may lead to inconsistent continuity of care, in terms of how mental health consumers perceive and experience their care services as connected and coherent, for example between hospital and community services.21

The recovery approach

For many years, the medical approach in the Westernised mental health system has been dominant. It views people with MHC as ‘patients’ who should be hospitalised for prolonged periods to reduce their symptoms.22 By contrast, in recent decades, the rehabilitation policy of mental health systems has been influenced by the Personal Recovery Approach which is based on the ‘person-centred’ principle.23 This approach focuses on integration into the community, improving quality of life, restoring a sense of control, autonomy, choice, meaning, independence as well as responsibility and hope despite the person's symptoms.22 23 Accordingly, personal recovery is not measured in terms of a reduction in symptoms or by a return to the state prior to the mental crisis, but rather by the ability to rebuild a personal identity and live a meaningful life with satisfying social roles and a sense of inclusion in the community.24 25

In Israel, the transition from the medical approach to the recovery approach has been reflected in several significant changes in the attitude of the State and society towards people with MHC. One of the main changes involved the enactment of the ‘Rehabilitation in the Community of Persons with Mental Disabilities Law of 2000’ that provides a package of rehabilitation services to adults with MHC with a significant dysfunction in their life and who are eligible for these services according to criteria determined by law.26 This law has contributed to increased integration of these individuals in the community which also has reduced prolonged hospitalisation and residence in institutions.26 Changes in the attitude of the State and society to people with MHC has led to initiatives to establish a variety of programme for community-based rehabilitation. One of these programmes is the Amitim program for adults. The programme was established at 2001, to comply with the abovementioned law for the inclusion of adults (aged 18+) with at least a 40% mental health disability as determined by the National Insurance Institute (NII) in Israel. The NII determines the disability level (from 0% to 100%) under the provisions of clauses 33 or 34 of the appendix to the NII Regulations for Determining the Level of Disability. For instance, a 40% mental health disability refers to a person in a post-psychotic condition with significant signs of impairment, limitation of work capacity and significant disruption of behavioural, mental and social functioning. (See: https://www.health.gov.il/English/Topics/Mental_Health/rehabilitation/Pages/sal.aspx). The Amitim program is the outcome of cooperation between the Ministry of Health and the Israel Association of Community Centers and operates currently in 77 community centres across the country. It currently serves approximately 3000 adults with MHC.

The literature on the recovery approach highlights the importance for services to consider adolescents’ developmental needs for independence, self-determination and self-efficacy when implementing a recovery-oriented adolescent-centred approach.27–29 This approach, which encourages them to express their needs and opinions about the services and engage actively in their rehabilitation process,27 28 30–33 was adopted by the Amitim for Youth programme.

Amitim for youth

In January 2018, a pioneering Amitim for Youth programme was launched by the Israel Association of Community Centers in cooperation with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and the Special Projects Fund of the National Insurance Institute. An inter-ministerial steering committee that consisted of representatives from each of these stakeholders was involved in the founding of the programme and its initial implementation. The programme provides a response to the absence of community-based psychosocial rehabilitation services for adolescents’ after-school leisure time. The programme consumers are adolescents (aged 12 to 18) who have a psychiatric diagnosis and are identified in the education system as those with ‘code 57’. The programme pilot was gradually implemented in six geographical districts near psychiatric hospitals which have a child and adolescent department (Haifa and Be'er Sheva), and near special education schools for children with MHC (Rehovot, Netanya, Petah Tikva and Karmiel). In each district, there is a coordinator who provides services to approximately 20 adolescents in the local community centres. Each adolescent in the programme is provided with a stipend (1200 Israeli shekels per year) for participation in leisure and arts activities in the community. The goals of Amitim for Youth relate to three dimensions: adolescents, their family and the wider community. For adolescents, the goals are to foster socialisation and a sense of belonging to the community, the ability to cope with self-stigma, prevention of repeated hospitalisations and shorter hospitalisation duration, return to age-appropriate functioning according to personal goals and finding a meaningful activity that will lead to satisfaction and self-actualisation. Another goal of the programme is to provide support to the adolescents’ family members (particularly parents), which is facilitated by the programme’s coordinator in each district. Finally, the goal for members of the community at large is to change attitudes towards adolescents with MHC by raising awareness.

The overarching goal of this study is to identify best practices for the implementation of a community-based psychosocial rehabilitation programme for adolescents with MHC. More specifically, the study will: (1) identify barriers and facilitators for the implementation of adolescents psychosocial rehabilitation in the community; (2) characterise the continuity of care, or lack thereof, between the referring mental health professionals (MHP) and the programme; (3) identify the needs of adolescents and their parents, programme team and referring MHP; (4) assess the satisfaction of adolescents and their parents with the overall programme and its components; (5) characterise the services in the programme and their value according to adolescents.

Research questions

The following research questions will be explored. They relate to infrastructure, implementation and continuity of care.

Programme infrastructure

(1) What characterises the referral procedure for the Amitim for Youth programme, and what are the barriers and facilitators factors? (2) What are the characteristics of the adolescents who participate in the programme? (3) What is the demand for the various components offered by the programme (including the arts)? What services are offered to the participants and how do they perceive them? What services are missing from the participants’ perspective?

Programme implementation

(4) How is the programme implementation experienced by the stakeholders? (5) What are the barriers and facilitators factors for programme implementation according to the adolescents themselves (participants and those who withdrew), parents, programme team members and referring MHP? (6) What best practices emerge from the perspectives of all involved?

Continuity of care

(7) What characterises the relationship between the referring MHP and the programme team in the community? (8) What best practices can be identified from the interface between referring MHP and community-based services according to the actors involved?

Methods and analysis

This qualitative study is situated between the pragmatic and constructivist paradigms.34 The pragmatic paradigm ‘focuses primarily on data that are found to be useful for stakeholders’.34 It has been defined as a real-world practice-oriented framework that focuses on useful applications (‘what works’) and practical solutions to problems, to gather information and insights on what is relevant to the stakeholders.35 36 The constructivist paradigm ‘focuses primarily on identifying multiple values and perspectives’.34 Accordingly, a close interaction with the stakeholders will be established to better understand their experiences, by taking the multiple perceptions of the different stakeholders of the programme into consideration.34 35 The two paradigms complement one another, given that their boundaries are permeable.34

Participants

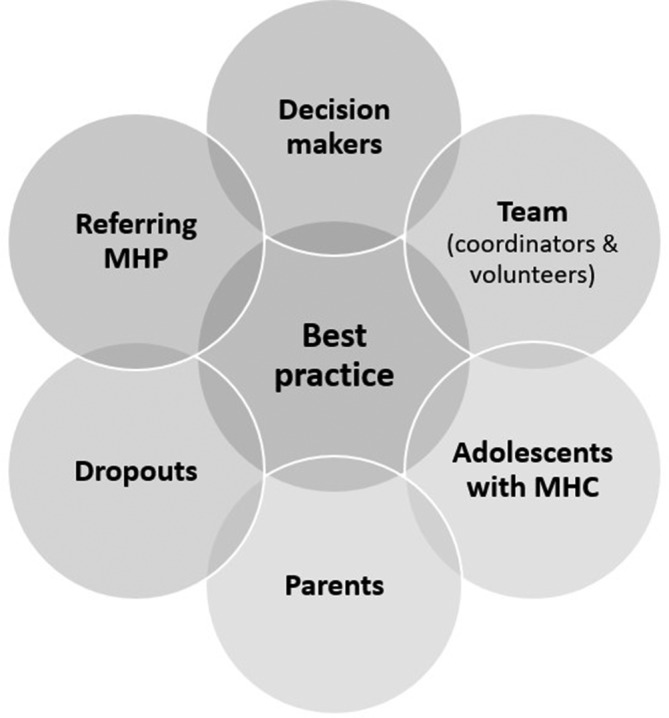

As can be seen in figure 1, the participants in this study will be composed of the following six groups of stakeholders: (1) the programme decision-makers, who include the programme commissioners and funders from different ministries, who are members of the programme’s inter-ministerial steering committee; (2) the programme team members, which includes coordinators and volunteers; (3) the intended beneficiaries of the programme; namely, adolescents enrolled in the Amitim for Youth programme for at least 3 months; (4) parents of these adolescents; (5) adolescents who withdrew from the programme and (6) referring MHP from clinics, hospitals and schools. Each of the six groups will have approximately 6 to 12 participants which is an acceptable number in qualitative research.

Figure 1.

The six groups of participants. MHC, mentalhealth conditions; MHP, mental health professionals.

Procedure

The study will use a maximum variation sampling approach of purposefully selecting a wide range of cases to document diversity and common patterns on dimensions of interest.35 The research team will contact the programme decision-makers and programme team members by phone to invite them to participate in the study. The programme coordinators will contact the parents and referring MHP via a formal letter explaining the study and including an informed consent form. Only those who provide their written informed consent will be contacted by the research team to schedule an interview. The MHP will be interviewed at their workplace or via the phone, at a convenient time for them. The parents and adolescents will be interviewed at their community centre or homes, at a time of their convenience. The researchers will also attend the meetings of the programme’s interministerial steering committee (participants in group 1 above) to document their perspectives and interactions.

Data collection

Semi-structured in depth interviews

Adolescents and their parents will be invited to participate in individual interviews, to better understand their subjective experiences.37 Examples of questions for the adolescents in the programme and their parents include: What do you want to get from the programme? What should be maintained or strengthened in the programme? What do you think should change in the programme? What benefits have you received from the programme? Examples of questions for the adolescents who withdrew from the programme are: How did you experience the programme? What relationship would you have liked to have with the coordinator of the programme? What made you leave the programme, what could have helped you stay?

The referring MHP will be interviewed to describe and evaluate recruitment processes and contacts with the programme team in terms of continuity of care. For example: What are the characteristics of the adolescents you refer to the programme? Describe the process of referring adolescents to the programme: How is it conducted, what factors help you decide, what can be improved? Are you updated by the programme team about the adolescents you referred to the programme? And if so, how does this take place and for what length of time?

Members of the steering committee will be interviewed to assess the development and implementation of the programme, for example: What difficulties, challenges and dilemmas did you encounter during the setting up and implementation of the programme? What can be improved and how? What is missing from the programme? The interviews will be conducted by the first author (HT) or a trained research assistant and will last approximately 60 to 90 min.

Focus groups

Each of the programme teams (ie, coordinators and volunteers) will be invited to attend focus groups, to discuss their impressions of the training, the programme implementation, as well as their relationship with the participants (adolescents and their parents) and with the referring MHP. The advantages of focus groups are that each participant can express his/her opinion in a collaborative forum that enables an exchange of different points of view, diverse interpretations, personal and collective experiences, in an honest and open discussion, without fear of criticism or censorship.38 Examples of questions for the coordinators and volunteers are: What preparation and training did you receive to work/volunteer in the programme? What difficulties, challenges and dilemmas have you encountered in the programme? Describe your role. Is your role clear to you? How would you describe your relationship with the adolescents and their parents (nature, frequency, content)? To minimise social desirability, individual interviews will also be conducted that may provide a deeper understanding of each coordinator’s personal experience. Focus groups will be conducted by the first author (HT) and will last 90 min.

Sociodemographic questionnaire

Adolescents will answer sociodemographic questions on their age, gender, country of birth, religion, length of time participating in the programme and number of days a week participating in the programme. The sociodemographic questionnaire for parents will include questions about socioeconomic status, marital status, their child’s medical history and whether their child takes psychiatric medication.

Data analysis

The qualitative data collected from the interviews and focus groups will be recorded and transcribed. The primary emphasis of this study is on identifying themes, commonalities, differences and patterns across the participants. Meaning and experience will be examined at both the semantic and latent levels, and best practices will be identified from the perspectives of the different stakeholders in the programme.35 36 To this end, a six-stage reflexive thematic analysis approach will be used, which is comprised of familiarisation with and immersion in the data, coding of the data, constructing initial themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and writing up the report with illustrative data extracts.39 This reflexive thematic analysis procedure will be used within the pragmatic and constructive frameworks. The checklist for good reflexive thematic analysis will be used as a guide to ensure an analysis that is rigorous and robust.40 The data analysis procedure will be conducted by the first author (HT) and assessed by second author (HO); disagreements will be resolved by discussion. A qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti) will be used for data management and to assist data analysis.

To strengthen the validity of the findings, a triangulation procedure will be conducted with the qualitative data that will be collected by different methods (individual interviews and focus groups) and from different types of stakeholders in the programme: the programme’s decision-makers, team, intended beneficiaries and referring MHP.36 41

Study trustworthiness

To strengthen the trustworthiness of the findings in addition to the triangulation, three strategies will be employed, as suggested in the qualitative research literature.41 Memo writing will be used to record decision-making, the process of meaning extraction from the data and subsequent conceptual development, as well as to facilitate continuous communication within the research team.42 A reflexivity journal will be used to gain and maintain self-awareness of the researcher’s perspective and its potential impact on the research process and interpretation of the findings.41 To increase the credibility of the research, member checking will be held (also known as participation validation). In this procedure, the findings will be presented to the participants who will be asked to respond whether they reflect their experience, meanings and perspectives.41 43 Finally, to enhance the rigour of the study the 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (see online supplementary file 1) will be used.44

bmjopen-2019-032809supp001.pdf (80.7KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public are not involved in the project.

Discussion

Recovery-oriented adolescent-centred services in the community are crucial in the critical developmental period of adolescence, which might be even more complex for adolescents with MHC and might lead to difficulties in identity formation.2 To date, adolescents with MHC in Israel are not eligible for community-based psychosocial rehabilitation services by law, despite the rising need. There is no centralised database with data on service consumers that is accessible by the three ministries that provide services for adolescents with MHC in Israel, which may result in inconsistent continuity of care. Coordination between different services is crucial for adolescents with MHC who go through multiple service transitions and are therefore more vulnerable to the risks of discontinuity.16 30 32 33 45 46

No study has examined a similar community-based psychosocial rehabilitation programme for adolescents with MHC in Israel. This study of the Amitim for Youth programme will enable a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators related to the infrastructure, implementation and continuity of care of these services in Israel. The implementation of this type of programme can be challenging because of its pioneering nature and its target population: adolescents who do not only face age-related challenges but also have MHC. Thus, recruiting adolescents with MHC to participate in this research might be challenging given their psychiatric condition. Some adolescents might be reluctant to participate out of self-stigma or low motivation whereas others might be eager to participate to share their experiences and express their voice. The findings will provide best practices recommendations to optimise the operation and implementation by service providers, enhance the service contribution to the consumers (adolescents and their parents) while meeting their needs and goals and inform policymakers. Specific attention will be paid to addressing the potential barriers and facilitators for effective programme implementation. The findings may ultimately serve as a basis for currently underdeveloped policy recommendations and legislation in the field of adolescent psychiatric rehabilitation.

Ethics and dissemination

Informed consent will be obtained from all participants and they will be guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Consent for the adolescents’ participation will be also obtained from their parents or guardians via written consent. Data collection will be conducted in the next 2 years (2019 to 2020). A report in Hebrew will be submitted to the National Insurance Institute. The results will be disseminated in articles that will be written in English as part of a doctoral dissertation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to the conceptualisation and design of the study. HT (MA, PhD candidate, cognitive behavioral drama therapist, female) conducted the literature review that was examined and approved by HO (PhD, researcher, male). Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study is funded by the Israeli National Insurance Institute (grant# 16343).

Disclaimer: The funding body will have no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation or publications.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study in its current design was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research in the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences at the University of Haifa (#455–18), and by the Chief Scientist in the Ministry of Education (#10566).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Orkibi H, Ronen T. A Dual-Pathway model linking self-control skills to aggression in adolescents: happiness and time perspective as mediators. J Happiness Stud 2019;20:729–42. 10.1007/s10902-018-9967-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steinberg LD. Adolescence. 11th edn New York, NY: McGraw-Hil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Erikson EH. Identity: youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dwivedi K, Harper P. Promoting emotional well-being of children and adolescents and preventing their mental ill health a handbook. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self‐stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martínez-Hidalgo Mª Nieves, Lorenzo-Sánchez E, López García JJ, et al. Social contact as a strategy for self-stigma reduction in young adults and adolescents with mental health problems. Psychiatry Res 2018;260:443–50. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mulfinger N, Müller S, Böge I, et al. Honest, open, proud for adolescents with mental illness: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 2018;59:684–91. 10.1111/jcpp.12853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaushik A, Kostaki E, Kyriakopoulos M. The stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2016;243:469–94. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rose AL, Atkey SK, Goldberg JO. Self-stigma in youth: Prevention, intervention, and the relevance for schools : Leschied AW, Saklofske DH, Flett GL, Handbook of school-based mental health promotion: an evidence-informed framework for implementation. Cham. Switzerland: Springer, 2018: 213–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leschied AW, Saklofske DH, Flett GL. Handbook of school-based mental health promotion: an evidence-informed framework for implementation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hartman LI, Michel NM, Winter A, et al. Self-stigma of mental illness in high school youth. Can J Sch Psychol 2013;28:28–42. 10.1177/0829573512468846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kranke D, Floersch J, Townsend L, et al. Stigma experience among adolescents taking psychiatric medication. Child Youth Serv Rev 2010;32:496–505. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moses T. Coping strategies and self-stigma among adolescents discharged from psychiatric hospitalization: a 6-month follow-up study. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2015;61:188–97. 10.1177/0020764014540146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mulfinger N, Rüsch N, Bayha P, et al. Secrecy versus disclosure of mental illness among adolescents: I. The perspective of adolescents with mental illness. J Ment Health 2019;28:296–303. 10.1080/09638237.2018.1487535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mulfinger N, Rüsch N, Bayha P, et al. Secrecy versus disclosure of mental illness among adolescents: II. The perspective of relevant stakeholders. J Ment Health 2019;28:304–11. 10.1080/09638237.2018.1487537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, et al. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015;56:345–65. 10.1111/jcpp.12381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Israel National Council for the Child Israel national council for the child, statistical abstract "children in Israel 2017" 2017 [Data Collection]. Available: https://www.children.org.il/

- 18. The Knesset Proposed Rights and Services for Children and Youth with Mental Disorders Law, 5766 - 2016. (P / 2783/20), 2019. Available: http://fs.knesset.gov.il//20/law/20_lst_323138.docx

- 19. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Mental health and human rights: report of the United nations high commissioner for human rights, 2017. Available: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/861008

- 20. Rabinowitz M. Children in Israel: selected issues regarding rights, needs and services. Israel: The Committee on the Rights of the Child, 20th Knesset, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joyce AS, Wild TC, Adair CE, et al. Continuity of care in mental health services: toward Clarifying the construct. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:539–50. 10.1177/070674370404900805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychiatr Rehabil J 1993;16:11–23. 10.1037/h0095655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davidson L. The recovery movement: implications for mental health care and enabling people to participate fully in life. Health Aff 2016;35:1091–7. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schrank B, Slade M. Recovery in psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin 2007;31:321–5. 10.1192/pb.bp.106.013425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Slade M. Personal recovery and mental illness: a guide for mental health professionals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aviram U, Ginath Y, Roe D. Mental health reforms in Europe: Israel's rehabilitation in the community of persons with mental disabilities law: challenges and opportunities. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:110–2. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes F, Hebel L, Badcock P, et al. Ten guiding principles for youth mental health services. Early Interv Psychiatry 2018;12:513–9. 10.1111/eip.12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McMahon J, Ryan F, Cannon M, et al. Where next for youth mental health services in Ireland? Ir J Psychol Med 2018:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rickwood D, Paraskakis M, Quin D, et al. Australia's innovation in youth mental health care: the headspace centre model. Early Interv Psychiatry 2019;13:159–66. 10.1111/eip.12740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, et al. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007;369:1302–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kohrt B, Asher L, Bhardwaj A, et al. The role of communities in mental health care in low- and middle-income countries: a Meta-Review of components and competencies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1279–31. 10.3390/ijerph15061279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malla A, Iyer S, Shah J, et al. Canadian response to need for transformation of youth mental health services: access open minds (Esprits ouverts). Early Interv Psychia 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cleverley K, Rowland E, Bennett K, et al. Identifying core components and indicators of successful transitions from child to adult mental health services: a scoping review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;202:1–15. 10.1007/s00787-018-1213-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mertens DM, Wilson AT. Program evaluation theory and practice. 2nd edn New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. 4th edn Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3th edn Los angeles, CA: Sage, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bloor M. Focus groups in social research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, et al. Thematic analysis : Liamputtong P, Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2019: 843–60. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, et al. Thematic analysis : Willig C, Rogers WS, The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research in psychology. London, UK: SAGE, 2017: 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. EFI 2004;22:63–75. 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Nurs Educ 2008;13:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Foster A. A nonlinear model of information-seeking behavior. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 2004;55:228–37. 10.1002/asi.10359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tobon JI, Reid GJ, Brown JB. Continuity of care in children’s mental health: parent, youth and provider perspectives. Community Ment Health J 2015;51:921–30. 10.1007/s10597-015-9873-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Paul M, Street C, Wheeler N, et al. Transition to adult services for young people with mental health needs: a systematic review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015;20:436–57. 10.1177/1359104514526603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032809supp001.pdf (80.7KB, pdf)