This Phase 1B study showed that a single tablet of 300 mg of posaconazole, given once daily as prophylaxis to 210 patients at risk for invasive fungal disease, was as safe as that reported for posaconazole oral suspension and achieved steady-state >500 ng/mL for all but one patient.

Abstract

Background

Antifungal prophylaxis with a new oral tablet formulation of posaconazole may be beneficial to patients at high risk for invasive fungal disease. A two-part (Phase 1B/3) study evaluated posaconazole tablet pharmacokinetics (PK) and safety.

Methods

Patients with neutropenia following chemotherapy for haematological malignancy or recipients of allogeneic HSCT receiving prophylaxis or treatment for graft-versus-host disease received 300 mg posaconazole (as tablets) once daily (twice daily on day 1) for up to 28 days without regard to food intake. Weekly trough PK sampling was performed during therapy, and a subset of patients had sampling on days 1 and 8. Cmin-evaluable subjects received ≥6 days of dosing, and were compliant with specified sampling timepoints. Steady-state PK parameters, safety, clinical failure and survival to day 65 were assessed. ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01777763; EU Clinical Trials Register, EUDRA-CT 2008-006684-36.

Results

Two hundred and ten patients received 300 mg posaconazole (as tablets) once daily. Among Cmin-evaluable subjects (n = 186), steady-state mean Cmin was 1720 ng/mL (range = 210–9140). Steady-state Cmin was ≥700 ng/mL in 90% of subjects with 5% (10 of 186) <500 ng/mL and 5% (10 of 186) 500–700 ng/mL. Six (3%) patients had steady-state Cmin ≥3750 ng/mL. One patient (<1%) had an invasive fungal infection. The most common treatment-related adverse events were nausea (11%) and diarrhoea (8%). There was no increase in adverse event frequency with higher posaconazole exposure.

Conclusions

In patients at high risk for invasive fungal disease, 300 mg posaconazole (as tablets) once daily was well tolerated and demonstrated a safety profile similar to that reported for posaconazole oral suspension: most patients (99%) achieved steady-state pCavg exposures >500 ng/mL and only one patient (<1%) had a pCavg <500 ng/mL.

Introduction

Posaconazole oral suspension is an extended-spectrum triazole that has demonstrated efficacy, a survival benefit and safety in prospective controlled clinical trials when given for the prophylaxis and treatment of invasive fungal disease (IFD).1–5 Studies in healthy adults have shown that the bioavailability of posaconazole oral suspension is 2.6 times greater when given with any food and 4 times greater with a high-fat meal.6,7 Another strategy to increase exposure with posaconazole suspension is dividing the total daily dose of posaconazole and administering it multiple times a day (i.e. 200 mg three times a day for prophylaxis or 200 mg four times a day for treatment).3 However, it is still necessary for patients to take posaconazole oral suspension with a high-fat meal or a nutritional supplement to enhance absorption. This poses a potential limitation because patients at risk for IFD may experience mucositis or neutropenic enterocolitis, limiting absorption, and they may be unable to eat because of nausea.8–10

To optimize bioavailability and improve compliance, a posaconazole tablet formulation has been developed that is taken once daily (after twice-daily dosing on day 1) and that can be administered with minimal impact of food.11

The new posaconazole tablet consists of posaconazole combined with a pH-dependent polymer (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate) to generate a solid dispersion material that prevents the dissolution of posaconazole at a low pH in the stomach until the drug reaches an elevated pH environment in the small intestine.12 In pharmacokinetic (PK) and safety studies in healthy volunteers,11,12 this posaconazole tablet formulation has shown improved exposure with less variability than posaconazole oral suspension in fasting patients.11,13 With the posaconazole tablet formulation exposure was also not impacted by the concomitant administration of medications that alter gastric pH.11,14 The posaconazole tablet formulation may, therefore, be beneficial in the prevention or treatment of IFD in high-risk patients with poor oral intake after chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation.

A two-part registration study (Phase 1B/3) evaluated the PK and safety of the posaconazole tablet formulation as antifungal prophylaxis in patients at high risk for IFD.

PK findings in a smaller cohort of patients, the Phase 1B dose-ranging portion of this study, have identified 300 mg once daily, following a twice-daily loading dose on day 1, as the preferred dose.15 Based on these findings, the 300 mg once-daily dose was selected for further evaluation in the Phase 3 portion of the study; herein we report the results.

Methods

Study design, patients and treatment

This was a global, sequential, open-label, multicentre, Phase 1B/3 PK and safety study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01777763; EU Clinical Trials Register, EUDRA-CT 2008-006684-36) conducted in 15 countries at 42 sites experienced in the care and treatment of patients at high risk for IFD and capable of performing serial PK sampling. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The protocol was reviewed and approved by Independent Ethics Committees at all participating study centres.

Patients at high risk for IFD were eligible for inclusion in this study, including patients undergoing chemotherapy for AML or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) who had neutropenia at baseline or who were likely to develop prolonged neutropenia within 3–5 days. Neutropenia was defined as absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3. HSCT recipients were eligible if receiving immunosuppressive therapy for the prevention or treatment of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Patients with either acute or chronic GVHD or with the potential to develop GVHD were eligible for inclusion. Patients were 18 years of age or older, weighed >34 kg and were able to tolerate the administration of oral tablet medication. Women of childbearing potential agreed to use a medically accepted form of contraception throughout the study. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding and had known or suspected IFD, history of type 1 hypersensitivity or idiosyncratic reactions to azoles, moderate or severe liver dysfunction (defined as AST or ALT levels >3× the upper limit of normal and total bilirubin level >2× the upper limit of normal) or prolonged QTc interval (>500 ms). Patients must not have taken posaconazole within 10 days or systemic antifungal therapy within 30 days of enrolment for reasons other than antifungal prophylaxis. Patients could not have taken investigational drugs within 30 days, medications known to interact with azoles and possibly leading to life-threatening effects within 24 h (except astemizole, which could not have been taken within 10 days) or β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzyme 3A4 within 24 h of the start of the study. Concomitant medications were monitored throughout the study.

After a twice-daily loading dose on day 1, patients received 300 mg posaconazole (three 100 mg tablets) once daily taken without regard to food intake. Food consumption or the timing of food relative to dosing was not recorded. The results from a subset of the study (Phase 1B dose-ranging portion) have been previously reported15 and that earlier report included 34 of the 210 total subjects treated with the 300 mg dose in the study. This report now summarizes the findings of all subjects treated with the 300 mg dose selected for product registration.

Posaconazole PK evaluations and procedure for blood collection

The primary PK parameter evaluated was the steady-state-predicted average posaconazole concentration (pCavg). The pCavg was a calculated parameter, derived using observed posaconazole trough concentrations (Cmin) values. In all patients, blood samples were collected before dosing for the PK analysis of Cmin on days 1, 2, 3, 8, 14, 21 and 28 or end of treatment. Blood samples on days 8, 14, 21 and 28 could be taken ±1 day. A subset of patients was included in the serial PK analysis, which also assessed the following parameters: area under concentration–time curve from time 0 to the last measurable concentration (AUCtf); maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) on days 1 and 8; time to Cmax (Tmax) on days 1 and 8; trough concentrations (Cmin); and apparent total body clearance (CL/F).

Blood samples for the subset of patients in the serial PK sampling were taken on day 1 and on day 8 [steady-state at 0 h (pre-dose) and at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h post-dose]. Two laboratories were used for the analysis of posaconazole concentrations (Merck & Co., Inc., and PPD Laboratories). Posaconazole concentrations in human plasma were assessed using a validated liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay with a nominal quantification range of 5–5000 ng/mL as previously described.16 Briefly, 4 mL of whole blood was collected into dipotassium EDTA-containing tubes and samples were centrifuged within 30 min of collection at 1500 g for 15 min at 4°C and then stored at −20°C until assayed.

A cross-validation was conducted using both assays to analyse quality-control samples of 15, 150, 400 and 4000 ng/mL. Acceptance criteria for this cross-validation were for two-thirds of the quality-control samples to have individual accuracy within ±15% of the nominal concentration, and mean accuracy to be within ±15% of nominal. Cross-validation was demonstrated.

Two PK populations were defined and analysed, i.e. a serial PK-evaluable population and a Cmin PK-evaluable population. Patients compliant with study drug dosing, full serial PK sampling and baseline posaconazole concentration <25 ng/mL were included in the serial PK-evaluable population. Patients who were compliant with study drug dosing, had baseline posaconazole concentration <25 ng/mL and had Cmin blood samples taken after the attainment of steady-state (day 6 or later) and within the specified period of 18–30 h from the previous dose of study drug were included in the Cmin PK-evaluable population.

Safety

Safety analyses were descriptive in nature and were performed on the treated population who received ≥1 dose of study drug. Adverse event (AE) reports, vital signs, clinical laboratory tests, gastrointestinal tolerance and electrocardiography results were recorded. Safety was assessed throughout the study at all visits until follow-up 7–10 days after the last posaconazole dose. Severity of AEs was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0, and a medically qualified investigator assessed causality between the AE and the use of study drug. To determine whether there was a potential association between reported AEs and exposure to posaconazole, the incidence of AEs by quartile of exposure was evaluated using all patients whose steady-state concentrations had been determined, and Cmin PK-evaluable populations for both the 200 and the 300 mg dose groups were combined. Patients were included by calculated pCavg, and the incidence of reported treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) was evaluated by quartile of exposure.

Efficacy

Clinical failure was determined by the incidence of breakthrough IFD. Each investigator determined the efficacy of therapy using a descriptive assessment of the clinical signs and symptoms for evaluation of possible, probable or proven IFD according to the EORTC/MSG criteria.17 There was no adjudication of fungal diagnosis. A survival assessment performed on day 65 (±5 days) was recorded for each patient.

Statistical analysis

No formal statistical data analysis was conducted. Target sample size was based on empirical factors to have sufficient numbers of patients for safety and PK evaluation of the 300 mg dose. All patients with PK data who met the predefined eligibility criteria were included in the PK analysis, whereas safety and efficacy analyses included all patients who received ≥1 dose of the posaconazole tablet formulation.

Results

Overall, 210 patients received 300 mg posaconazole once daily during the study, including 34 patients in Phase 1B and 176 patients in Phase 3 (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 51 years; most were male (62%) and white (93%). One hundred and thirteen (54%) of the patients had AML, 91 (43%) were HSCT recipients and six (3%) had MDS. Thirty-two of the 91 HSCT recipients had acute GVHD, including 11 with grade 2 GVHD and three with grade 3 GVHD. Six patients with acute GVHD had intestinal involvement. Another 11 patients had chronic GVHD (limited in seven, extensive in four).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (all treated patients)

| Demographics and characteristics | 300 mg posaconazole once daily, N = 210 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| mean (SD) | 51.0 (14.1) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 35 (17) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| male | 131 (62) |

| female | 79 (38) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| white | 196 (93) |

| Asian | 2 (1) |

| black/African American | 2 (1) |

| multiracial | 6 (3) |

| native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 4 (2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| not Hispanic/Latino | 181 (86) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 (12) |

| missing data | 4 (2) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 77.1 (18.1) |

| Primary diagnosis at study entry, n (%) | |

| AML (new diagnosis) | 97 (46) |

| AML (first relapse) | 16 (8) |

| MDS | 6 (3) |

| HSCT | 91 (43) |

PK analysis

Serial PK-evaluable analysis

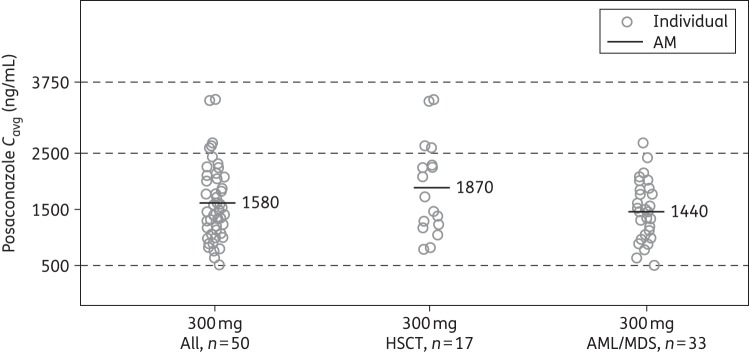

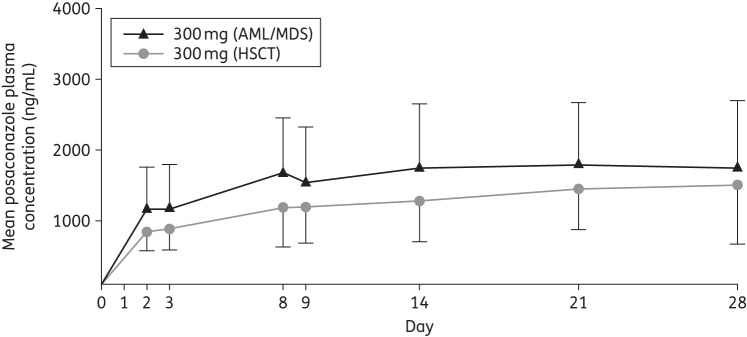

In total, 50 patients were included in the serial PK-evaluable population in either the Phase 1B or the Phase 3 portion of the study. Among these patients who received multiple-dose administration of posaconazole tablets at 300 mg once daily (following twice daily on day 1), the peak plasma concentration of posaconazole was achieved at a median Tmax of 4 h on day 8 and the mean Cavg was 1580 ng/mL (Table 2). Exposure was slightly higher in the HSCT group than in the AML/MDS group (mean Cavg, 1870 versus 1440 ng/mL, respectively; Figure 1), which was consistent across the concentration–time profiles of the entire study period (Figure 2). The predefined exposure target range was achieved, with 90% of patients having attained a Cavg between 500 and 2500 ng/mL and 10% having attained a Cavg between 2500 and 3750 ng/mL. In the serial PK-evaluable patient population, no patient had a steady-state Cavg below 500 ng/mL, four patients (8%) had Cavg between 500 and 700 ng/mL and no patient had Cavg exceeding 3750 ng/mL. There was also no clear effect of weight, AML/MDS and HSCT status, mucositis AEs and diarrhoea AEs on the Cmin concentrations (Figures S1 to S3, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Table 2.

Arithmetic mean (%CV) steady-state (day 8) PK parameters following multiple dosing of a 300 mg posaconazole tablet formulation once daily (serial PK-evaluable population)

| Disease state | n | C max (ng/mL) | T max (h), median (range) | AUCtf (h·ng/mL) | C avg (ng/mL) | C min (ng/mL) | CL/F (L/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 50 | 2090 (38) | 4 (1.3–8.3) | 37 900 (42) | 1580 (42) | 1310 (50) | 9.39 (45) |

| HSCT | 17 | 2390 (43) | 4.1 (2.0–8.3) | 44 800 (45) | 1870 (45) | 1540 (49) | 8.11 (46) |

| AML/MDS | 33 | 1930 (32) | 2.2 (1.3–8.1) | 34 300 (36) | 1440 (36) | 1190 (47) | 10.1 (43) |

AUCtf, area under concentration–time curve from time 0 to the time of the final quantifiable sample; Cavg, predicted Cavg based on Cmin; CL/F, apparent total body clearance; Cmax, maximum observed concentration; Cmin, posaconazole trough level immediately before dose of posaconazole on the day specified in the protocol; CV, coefficient of variation; Tmax, time of observed maximum plasma concentration.

Figure 1.

Individual observed posaconazole Cavg following multiple dosing of a posaconazole tablet formulation at 300 mg once daily (serial PK-evaluable population). AM, arithmetic mean; Cavg, average concentration at steady-state.

Figure 2.

Mean (SD) of posaconazole plasma concentration–time profiles by disease state (day 1 and day 8) following multiple dosing of a 300 mg posaconazole tablet formulation once daily (serial PK-evaluable population).

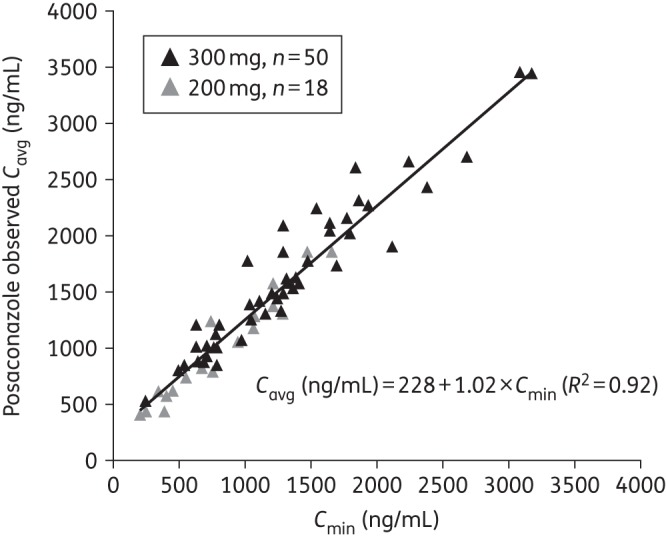

In the serial PK-evaluable population, a strong correlation was found between the observed Cavg and Cmin values (R2 = 0.92; Figure 3). The linear regression model was developed from observed Cmin and Cavg on day 8. The formula was then used to predict steady-state Cavg (pCavg) for patients with only trough samples by using average Cmin values (an average of Cmin values taken on or after day 7): pCavg = 228 + 1.02 × average Cmin. Using this linear regression model, the pCavg values were derived from observed average steady-state Cmin values.

Figure 3.

Individual plot of observed Cavg versus Cmin values on day 8 following multiple dosing of a posaconazole tablet formulation at 300 or 200 mga once daily (n = 68; serial PK-evaluable population). aEighteen patients receiving 200 mg posaconazole were from part 1 of the study; they are included in the regression analysis, but are not further discussed in this paper (results for these patients have been previously presented14).

C min PK-evaluable analysis

Overall, 186 patients were included in the Cmin PK-evaluable population (Table 3). Of the 24 patients who were excluded from the Cmin PK-evaluable population, 15 did not receive 8 days of dosing; 7 did not adhere to their dosing schedule or received incorrect dosing during the first 8 days of treatment; and 2 had baseline posaconazole concentration >25 ng/mL.

Table 3.

Arithmetic mean (%CV) of average Cmin and predicted Cavg following multiple dosing of a 300 mg posaconazole tablet formulation once daily (Cmin PK-evaluable population)

| Disease state | n | Average Cmin (ng/mL) |

pCavg (ng/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM (%CV) | range | AM (%CV) | range | ||

| All patients | 186 | 1720 (64) | 210–9140 | 1970 (56) | 442–9520 |

| AML/MDS | 107 | 1430 (48) | 210–3680 | 1680 (41) | 442–3970 |

| HSCT | 79 | 2110 (66) | 445–9140 | 2370 (60) | 680–9520 |

AM, arithmetic mean; pCavg, predicted Cavg based on Cmin; average Cmin, average of the posaconazole trough levels taken immediately before dose of posaconazole; CV, coefficient of variation.

Steady-state Cmin evaluation

In the Cmin-evaluable population, the majority of patients (n = 141, 76%) had Cmin values ≥700 ng/mL and <2500 ng/mL (Table 4); 20 patients (10%) had Cmin values <700 ng/mL and 25 (13%) had Cmin values ≥2500 ng/mL. Few patients had Cmin values <500 ng/mL (n = 10, 5%) or ≥3750 ng/mL, and no patient had Cmin <200 ng/mL. Overall, 95% (176 of 186) of subjects had Cmin values ≥500 ng/mL and 89% (166 of 186) had Cmin values ≥700 ng/mL (Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency distribution of observed Cmin following multiple 300 mg dose administration of a posaconazole tablet formulation in patients at high risk for invasive fungal infection

| C min a (ng/mL) | C min evaluable | Serial PK evaluable |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| all patients, N = 186 | AML/MDS + HSCT, n = 50 | AML/MDS, n = 33 | HSCT, n = 17 | |

| ≥200 and <500 | 10 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 0 |

| ≥500 and <700 | 10 (5%) | 5 (10%) | 4 (12%) | 1 (6%) |

| ≥700 and <1250 | 44 (24%) | 16 (32%) | 10 (30%) | 6 (35%) |

| ≥1250 and <2500 | 97 (52%) | 23 (46%) | 15 (45%) | 8 (47%) |

| ≥2500 and <3750 | 19 (10%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (12%) |

| ≥3750 | 6 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

C min, posaconazole trough level immediately before a subject received the dose of posaconazole on the day specified in the protocol; n, number of subjects.

No subject with Cmin value >3650 and <3750 ng/mL in the serial PK-evaluable group.

aObserved Cmin on day 8.

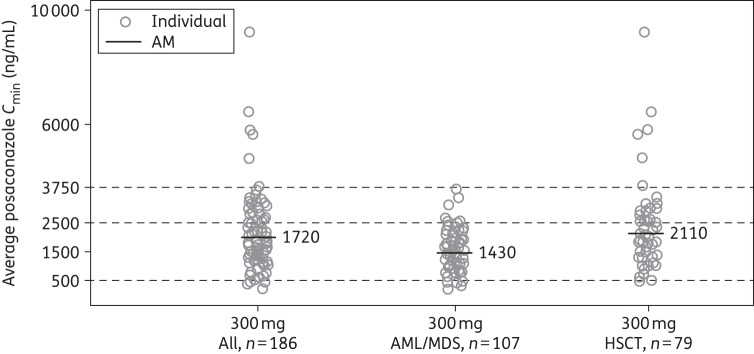

Among the Cmin PK-evaluable patients, pCavg levels of 300 mg posaconazole were comparable or somewhat higher than the observed Cavg values on day 8 in the serial PK-evaluable population (mean values, 1970 versus 1580 ng/mL). Average Cmin values were higher for the HSCT Cmin PK-evaluable subpopulation than for the AML/MDS Cmin PK-evaluable subpopulation (2110 versus 1430 ng/mL) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Individual steady-state posaconazole average Cmin following multiple dosing of a posaconazole tablet formulation at 300 mg once daily (Cmin PK-evaluable cohort). AM, arithmetic mean; Cmin, trough concentration.

Steady-state Cavg evaluation

Most (80%) patients achieved a target exposure range of pCavg between 500 and 2500 ng/mL, and 16% achieved a target exposure range between 2500 and 3750 ng/mL (Table 5). Seven patients (4%) had Cavg <700 ng/mL but only one (0.5%) patient's pCavg fell below 500 ng/mL (pCavg 442 ng/mL); in seven (4%) patients Cavg exceeded 3750 ng/mL. Overall, 179 of 186 (96%) evaluable patients treated with the 300 mg dose achieved pCavg ≥700 ng/mL.

Table 5.

Frequency distribution of predicted steady-state Cavg following multiple dosing of a 300 mg posaconazole tablet formulation once daily, overall and by underlying disease (Cmin PK-evaluable population)

| pCavga (ng/mL) | C min evaluable | Serial PK evaluableb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| all patients, N = 186 | AML/MDS + HSCT, n = 50 | AML/MDS, n = 33 | HSCT, n = 17 | |

| ≥200 and <500 | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| ≥500 and <700 | 6 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| ≥700 and <1250 | 33 (18%) | 15 (30%) | 10 (30%) | 5 (29%) |

| ≥1250 and <2500 | 110 (59%) | 28 (56%) | 20 (61%) | 8 (47%) |

| ≥2500 and <3750 | 29 (16%) | 5 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (24%) |

| ≥3750 | 7 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

n, number of subjects.

apCavg (predicted Cavg) was derived from a linear regression model using observed Cmin on day 8 from P05615 Part 1 and 2 (pCavg = 228 + 1.02 × average Cmin).

bObserved Cavg on day 8.

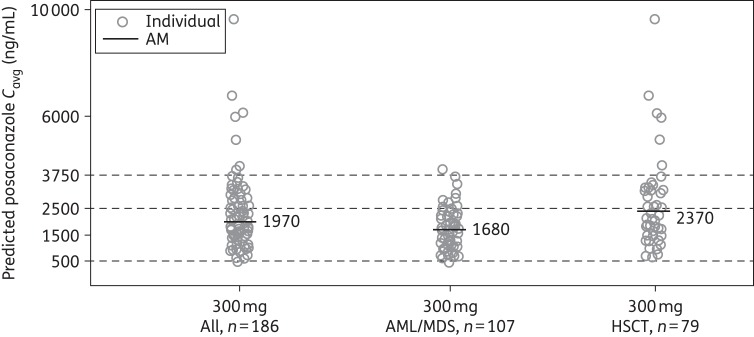

Average pCavg values were higher for the HSCT Cmin PK-evaluable subpopulation than for the AML/MDS Cmin PK-evaluable subpopulation (2370 versus 1680 ng/mL) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Individual predicted posaconazole Cavg following multiple dosing of a posaconazole tablet formulation at 300 mg once daily (Cmin PK-evaluable population). AM, arithmetic mean; Cavg, average concentration at steady-state.

Safety

The posaconazole tablet formulation was well tolerated and had a safety profile similar to that previously noted for posaconazole oral suspension when taken by patients at high risk for IFD.1,2 Almost all patients (99%) experienced ≥1 TEAE; 40% experienced treatment-related TEAEs, and 18% experienced AEs leading to early study discontinuation (Table 6). Eleven (5%) patients discontinued posaconazole because of treatment-related AEs. Most commonly reported treatment-related AEs were nausea (11%) and diarrhoea (8%) (Table 5). However, discontinuations due to nausea and diarrhoea occurred in only 2% and 1% of all patients, respectively. Serious AEs were reported in 33% of patients. Most commonly reported serious AEs were febrile neutropenia (5%), sepsis (2%) and diarrhoea (2%).

Table 6.

Summary of treatment-related TEAEs with an incidence ≥2% and all-cause TEAEs in patients treated with a 300 mg posaconazole tablet formulation

| Most common AEs | 300 mg posaconazole once daily, N = 210 |

|

|---|---|---|

| treatment-related TEAEs, n (%) | all-cause TEAEs, n (%)a | |

| Treatment-related TEAEs | 84 (40) | 207 (99) |

| nausea | 23 (11) | 56 (27) |

| diarrhoea | 16 (8) | 61 (29) |

| abdominal pain | 9 (4) | 23 (11) |

| ALT increased | 9 (4) | 15 (7) |

| vomiting | 9 (4) | 28 (13) |

| AST increased | 8 (4) | 12 (6) |

| hypokalaemia | 6 (3) | 46 (22) |

| upper abdominal pain | 5 (2) | 14 (7) |

| dyspepsia | 5 (2) | 13 (6) |

| hypophosphataemia | 5 (2) | 17 (8) |

| liver function test abnormal | 5 (2) | — |

| rash | 5 (2) | 34 (16) |

| flatulence | 4 (2) | — |

| Serious AEs | 69 (33) | |

| Deathsb | 20 (10) | |

| Severe/life-threatening TEAEs | 111 (53) | |

| Study drug discontinuation due to an AE | 38 (18) | |

aWith an incidence ≥5%.

bTwo deaths occurred after day 65.

A quartile analysis (n = 205 patients in the 200 and the 300 mg dose groups) found no discernible correlation between posaconazole plasma exposures and safety in terms of TEAE or treatment-related TEAE incidence, including no correlation between higher posaconazole exposure and an increase in hepatic or cardiac AEs. Specifically, the incidence of treatment-related TEAEs was lower for the fourth highest quartile of exposure when compared with the first lowest quartile of exposure (38% versus 57%), and a similar incidence of related TEAEs was reported for the second and third quartiles, which had similar incidences (37% and 31% respectively) (Table 7). In the analysis of a possible relationship between gastrointestinal AEs and posaconazole plasma concentrations, no correlation was noted between posaconazole exposure (Cavg) and the occurrence of mucositis or diarrhoea (Supplementary Data). The effect of posaconazole treatment on electrocardiographic and laboratory parameters is reported in the Supplementary data and was similar to that previously reported for posaconazole oral suspension. Among patients receiving the 300 mg daily dose, survival at day 65 was high (91%), and the most common causes of death were infections, reported in 8 subjects, including sepsis and septic shock. Two subjects had renal failure reported as an AE leading to death. No deaths were considered related to study drug.

Table 7.

Summary of treatment-related TEAEs by quartile of pCavg values, all Cmin PK-evaluable patients: posaconazole 200 mg and 300 mg dose groups combined

| Quartile | Posaconazole pCavg mean (ng/mL) | pCavg range (ng/mL) | Number of subjects | Subjects reporting any treatment-related TEAEs, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 860 | 442–1223 | 51 | 29 (57) |

| 2 | 1481 | 1240–1710 | 51 | 19 (37) |

| 3 | 1979 | 1719–2291 | 51 | 16 (31) |

| 4 | 3194 | 2304–9523 | 52 | 20 (38) |

pCavg, predicted average concentration from Cmin.

AEs occurring in >5% of subjects in each quartile were as follows: quartile 1—diarrhoea 12%, nausea 10%, rash 10%, abdominal pain 8%, hypokalaemia 6%, hypophosphatemia 6%, vomiting 6%; quartile 2—diarrhoea 6%, nausea 10%, abdominal pain 6%, vomiting 6%; quartile 3—diarrhoea 12%, nausea 6%, hypokalaemia 6%, increased ALT 8%, dyspepsia 6%, increased AST 6%; quartile 4—nausea 13%, vomiting 8%.

Efficacy

One patient (<1%) who received the 300 mg dose had a reported breakthrough proven or probable IFD. The patient had AML/MDS, was diagnosed with a proven Candida glabrata infection involving the pleural space on day 7 and was discontinued from the study drug on day 10 with the infection considered ongoing. The patient's posaconazole concentration was 2530 ng/mL on day 8 and 2930 ng/mL on day 11 (1 day after the last dose). At day 65 survival visit, the patient was alive.

Discussion

This pivotal trial supporting registration of posaconazole tablet formulation characterized the PK and confirmed the safety of posaconazole tablet formulation in a representative patient population. The new posaconazole tablet formulation may have enhanced benefits compared with the oral suspension, fulfilling an unmet medical need in patients who require antifungal prophylaxis. Although posaconazole oral suspension is effective and generally well tolerated as antifungal prophylaxis, the need for multiple dosing per day and the requirement for it to be taken with food to enhance absorption are potential limitations.18,19 This study demonstrated that posaconazole tablet formulation can be administered just once a day without any food requirement to patients at high risk for IFD, such as those undergoing chemotherapy for AML or MDS and HSCT recipients with GVHD.

Although a threshold plasma level for the prevention of breakthrough IFD has not been defined for posaconazole,20,21 plasma level may be important in maintaining the efficacy of posaconazole as prophylaxis for IFD.22 In the current study, the lower target exposure of Cavg ≥500 ng/mL was based on the exposure response from a previous analysis that showed a positive association between posaconazole exposure and response in a non-randomized trial of posaconazole salvage treatment for invasive aspergillosis.4 Furthermore, breakthrough IFD developed in only 0.5% of patients, which is lower than the 2%–5.3% rate of proven or probable IFD observed in large trials in which posaconazole solution was used.1,2 The maximum desired exposure target of 3750 ng/mL was derived from safety observations from prior clinical and preclinical studies and sought to maintain exposures within the upper limit of exposures achieved with previous formulations. Among 186 Cmin PK-evaluable patients treated with the 300 mg dose of posaconazole (as tablets), the mean Cavg at steady-state was 1970 ng/mL. Most (99%) patients achieved steady-state pCavg exposures ≥500 ng/mL, and only 1 (<1%) had a pCavg <500 ng/mL.

The target patient population enrolled in this study was representative of patients who are at high risk for serious and life-threatening IFDs that require antifungal prophylaxis and was similar to the populations for whom posaconazole is approved for the prevention of IFD.23,24 It is noteworthy that posaconazole tablets consistently achieved the pre-specified exposure targets in almost all patients and thus this formulation represents an important therapeutic alternative for patients with limited options for antifungal prophylaxis, such as those with mucositis or neutropenic enterocolitis. The lack of requirement for food with this formulation also represents an important therapeutic advantage in these critically ill patients. Consistent with other posaconazole formulations, a loading dose involving twice-daily administration on day 1 is utilized to ensure rapid attainment of target serum drug levels and mitigate concerns regarding unsatisfactory drug absorption in this critically ill patient group. Overall, the PK profile seen in this study extends to patients with both AML/MDS and to patients following HSCT, although serum drug levels appeared to be slightly higher in the latter group. In general, HSCT patients treated with 300 mg once daily of the posaconazole tablet formulation attained somewhat higher concentrations than patients with AML/MDS with pCavg values of 2370 and 1680 ng/mL, respectively. The reason for these differences is unknown and the limited sample size in the present study precludes further exploratory analyses or any strong conclusions.

The PK profile of the posaconazole tablet formulation in the present study is generally similar to PK data reported from previous studies. In the Phase 1B portion of this study (reported previously), 34 patients received the 300 mg posaconazole tablet formulation once daily.15 Overall, 97% of patients receiving the 300 mg dose achieved the target daily exposure of ≥500 and ≤2500 ng/mL. In an earlier study of posaconazole tablets in healthy volunteers (200 and 400 mg/day once daily with no initial loading dose), accumulation ratios were 3–5 over the first 8 days of dosing, with a day 14 Cavg of 2360 ng/mL with the 400 mg dose and 1310 ng/mL with the 200 mg dose.12 By contrast, in the Phase 3 studies of 200 mg posaconazole oral suspension (three times daily), mean plasma concentrations of posaconazole were 583 ng/mL in patients with neutropenia, 1470 ng/mL in patients with chronic GVHD and 958 ng/mL in patients with acute GVHD.1,2

Overall, the posaconazole tablet formulation taken (300 mg once daily) had an acceptable safety profile within the range of exposures studied in patients at risk for IFD. In general, the safety profile was similar to that previously reported for posaconazole oral suspension, with gastrointestinal AEs the most frequently reported type of AE.1,2 A quartile analysis found no correlation between posaconazole plasma exposures and safety, which is consistent with previous analyses that have reported no significant relationships between Cavg and posaconazole-related AEs.22 Even in the highest quartile of exposure (range = 2304–9523 ng/mL), no association with an increased incidence of AEs was observed.

In summary, this new tablet formulation of posaconazole was well tolerated and was associated with a low incidence of IFD when given to a representative patient population of AML, MDS or HSCT patients. In such patients at high risk for IFD, the posaconazole tablet formulation taken at a daily dose of 300 mg (following twice-daily dosing on day 1) achieved predicted steady-state concentrations of 1970 ng/mL (range = 442–9520). The posaconazole tablet formulation consistently achieved exposures considered efficacious in addressing an important medical need for patients at risk for IFD.

Funding

This work was supported by Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA. Medical writing and editorial assistance was funded by Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA.

Transparency declarations

O. A. C. has received consulting fees or honoraria and travel fees from Merck, and his institution has received grant funds from Merck. He also has received consulting fees from Astellas, Basilea, F2G, Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, grants from Astellas, Basilea, Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, lecture fees from Astellas, Basilea, F2G, Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, and payment for the development of educational presentations from Basilea and MSD. R. F. D. has received travel support, lecture fees and advisory board fees from Merck. S. H. has received advisory board fees from Merck. P. C. has received grants from Merck. D. H. has received a grant from Merck. J. L. J. has received clinical trial expenses from Merck. A. C. has nothing to declare. I. R. has received grants and personal fees from Pfizer. M. L. has received honoraria, grants and consulting fees from Astellas, Merck and Pfizer. A. L. has received financial support for the present study. N. K., N. C. and H. W. are/were employees of Merck and own stock or stock options in Merck. M. V. I. is an ex-employee of Merck.

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by David Gibson, PhD, CMPP and Tim Ibbotson, PhD, of ApotheCom (San Francisco, CA, USA and Auckland, New Zealand).

Author contributions

H. W. and N. K. contributed to study conception and design. O. A. C., R. F. D., S. H., P. C., D. H., A. L., M. L., H. W. and I. R. were involved with data acquisition. H. W., N. C., S. H., N. K., A. L., J. L. J., I. R. and M. V. I. conducted the data analysis. H. W., A. C., O. A. C., R. F. D., S. H., N. K., M. L., J. L. J., I. R. and M. V. I. interpreted the data. A. C., P. C., O. A. C., R. F. D., S. H., A. L. and I. R. provided study materials/patients. O. A. C. and I. R. wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed substantially to revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, and all approved the final version before submission. O. A. C. and R. F. D. attest that they had full access to all the data, and they take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Some data presented in this manuscript were first presented at the Twenty-third European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Berlin, Germany, 2013 (Poster LB2966).

In addition to the cited authors, we thank all the investigators involved in this trial.

References

- 1. Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ et al. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 348–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ullmann AJ, Lipton JH, Vesole DH et al. Posaconazole or fluconazole for prophylaxis in severe graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 335–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keating GM. Posaconazole. Drugs 2005; 65: 1553–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walsh TJ, Raad I, Patterson TF et al. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of conventional therapy: an externally controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raad II, Hachem RY, Herbrecht R et al. Posaconazole as salvage treatment of invasive fusariosis in patients with underlying hematologic malignancy and other conditions. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: 1398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Courtney R, Wexler D, Radwanski E et al. Effect of food on the relative bioavailability of two oral formulations of posaconazole in healthy adults. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 57: 218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krishna G, Moton A, Ma L et al. The pharmacokinetics and absorption of posaconazole oral suspension under various gastric conditions in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 958–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pille S, Bohmer D. Options for artificial nutrition of cancer patients. Strahlenther Onkol 1998; 174: 52–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sansone-Parsons A, Krishna G, Calzetta A et al. Effect of a nutritional supplement on posaconazole pharmacokinetics following oral administration to healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50: 1881–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vehreschild MJ, Meissner AM, Cornely OA et al. Clinically defined chemotherapy-associated bowel syndrome predicts severe complications and death in cancer patients. Haematologica 2011; 96: 1855–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krishna G, Ma L, Martinho M, O'Mara E. A single dose phase I study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of posaconazole new tablet and capsule formulations relative to oral suspension. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 4196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krishna G, Ma L, Martinho M et al. A new solid oral tablet formulation of posaconazole: a randomized clinical trial to investigate rising single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and safety in healthy volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 2725–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dogterom P, Xu J, Waskin H et al. The effect of food on the posaconazole pharmacokinetics investigated during the development of a new tablet formulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013; 95Suppl 1: S17–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kraft WK, Chang P, van Iersel ML et al. Posaconazole tablet pharmacokinetics: lack of effect of concomitant medications altering gastric pH and gastric motility in healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4020–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duarte RF, López-Jiménez J, Cornely OA et al. Phase 1b study of new posaconazole tablet for the prevention of invasive fungal infections in high-risk patients with neutropenia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 5758–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shen JX, Krishna G, Hayes RN. A sensitive liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry method for the determination of posaconazole in human plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2007; 43: 228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46: 1813–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krishna G, Tarif MA, Xuan F et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral posaconazole in neutropenic patients receiving chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 2008; 28: 1223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cornely OA, Helfgott D, Langston A et al. Pharmacokinetics of different dosing strategies of oral posaconazole in patients with compromised gastrointestinal function and who are at high risk for invasive fungal infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2652–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krishna G, Martinho M, Chandrasekar P et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral posaconazole in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with graft-versus-host disease. Pharmacotherapy 2007; 27: 1627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cornely OA, Ullmann AJ. Lack of evidence for exposure-response relationship of posaconazole used for prophylaxis against invasive fungal infections. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 89: 351–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jang SH, Colangelo PM, Gobburu JV. Exposure-response of posaconazole used for prophylaxis against invasive fungal infections: evaluating the need to adjust doses based on drug concentrations in plasma. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010; 88: 115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noxafil® (Posaconazole) Oral Suspension. Hertfordshire, UK: Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noxafil® (Posaconazole) Oral Suspension. Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: Merck & Co. Inc., 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.