Abstract

Conducting clinical trials in critical care is integral to improving patient care. Unique practical and ethical considerations exist in this patient population that make patient recruitment challenging, including narrow recruitment timeframes and obtaining patient consent often in time-critical situations. Units currently vary significantly in their ability to recruit according to infrastructure and level of research activity.

Aim

To identify variability in the research infrastructure of UK intensive care units and their ability to conduct research and recruit patients into clinical trials.

Design

We evaluated factors related to intensive care patient enrolment into clinical trials in the UK. This consisted of a qualitative synthesis carried out with two datasets of in-depth interviews (distinct participants across the two datasets) conducted with 27 intensive care consultants (n=9), research nurses (n=17) and trial coordinators (n=1) from 27 units across the UK. Primary and secondary analyses of two datasets (one dataset had been analysed previously) were undertaken in the thematic analysis.

Findings

The synthesis yielded an overarching core theme of normalising research, characterised by motivations for promoting research and fostering research-active cultures within resource constraints, with six themes under this to explain the factors influencing critical care research capacity: organisational, human, study, practical resources, clinician and patient/family factors. There was a strong sense of integrating research in routine clinical practice, and recommendations are outlined.

Conclusions

The central and transferable tenet of normalising research advocates the importance of developing a culture where research is inclusive alongside clinical practice in routine patient care and is a requisite for all healthcare individuals from organisational to direct patient contact level.

Keywords: qualitative synthesis, critical care trials, barriers, facilitators, normalising research, access to research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This qualitative synthesis uniquely draws together two datasets exploring the factors that enable or hinder critical care research and presents an overarching theme of normalising research, outlining factors necessary to achieve this.

The dataset and purposive sample encompasses 14 out of 16 of the National Institute for Health’s Clinical Research Networks across England and Wales, reflecting a broad range of research experiences in critical care units.

The synthesis builds on previous research and highlights how integration and normalisation of research in clinical practice requires several interrelated factors including training, cultural receptivity, adequate funding, flexible study designs, good communication and interdisciplinary working at all levels, and a flexible staffing approach.

While we noted some similar challenges to study outside the UK, this study used two datasets solely from the UK which has a robust critical care research infrastructure and may differ from other challenges across the world.

This study focused on samples from both research-active and non-research-active units, however the qualitative purposive sampling, and small sample size (n=27) may have led to a sampling bias, meaning that the issues raised do not reflect all the issues encountered in practice.

Background

Clinical trials in critical care are integral to improving patient care, although unique practical and ethical challenges exist including the time-sensitive nature of treatment and enrolling patients who lack capacity.1 Data exploring barriers to conducting clinical trials in this setting are scarce, but include managing changing clinical courses, communication breakdowns and requests for more time for consent.2 Our previous study, focusing on research-active centres,3 described enhanced patient recruitment in centres valuing research with equal importance to clinical care. The most commonly cited barriers were: insufficient human and financial resource, inadequate personnel funding and limited career opportunities, impeding staff retention.3 Several additional factors may also preclude recruitment, such as lack of clinician equipoise and competing clinical commitments.

Implications for the National Institute for Health and Research

The UK National Institute for Health and Research (NIHR) is the government-funded research arm of the National Health Service (NHS), responsible for driving bench-to-bedside research with tangible patient benefit.4 Unique infrastructure, including the national coordinated Clinical Research Network (CRN) and specialty groups with oversight for specific clinical areas such as critical care, enhance the UK’s national and international position to deliver high-quality clinical trials. Research teams invest significantly in recruitment to critical care trials with emphasis on mitigating modifiable factors. In particular, understanding the barriers and facilitators in institutions which are less research-active, such as non-university-affiliated hospitals, is crucial to enhance trial recruitment across the NIHR CRN.

Our objective was therefore to identify examples of these potential barriers and facilitators to patient enrolment in order to inform strategies to enhance future critical care trial recruitment, and identify how research staff could be supported in these organisations.

Methods

Design

A qualitative synthesis was conducted,5 involving two datasets comprising in-depth interviews (n=27) with critical care consultants (n=9), research nurses (n=17) and trial coordinators (n=1) across England and Wales (26 hospitals; 27 units). Dataset 1 included 10 participants and is reported in detail elsewhere.3 For that dataset, a sampling frame across the CRNs was used to represent a mix of smaller and larger intensive care units (ICUs), from teaching hospitals and district general type hospital ICUs, including one person within each CRN to ensure region-wide representation. Dataset 2, a follow-on study, included a further 17 participants from different backgrounds/units, with the aim of specifically exploring issues in less research-active critical care units. Service evaluation and quality improvement methods underpinned the projects.6 Therefore, this synthesis involved both primary and secondary data analyses. Qualitative synthesis is a well-established method that draws together findings to reach overarching themes.,5 ensuring similar research can be reliably compared.7–9

Patient public involvement

Patient/public were not involved in the design of this study since the focus is on research infrastructure.

Data collection

Individual telephone, digitally audio-recorded, interviews were conducted with participants, using a predetermined semistructured interview schedule agreed by team consensus. The aim of the second set of interviews was to understand how to engage and promote research activity and increase trial recruitment in critical care units that find it challenging to recruit to trials. Interview questions included: What can you tell me about how the unit decides whether to participate in a research project? Tell me about the infrastructure in your critical care unit to support research. See online supplementary file 1 for interview questions. Written and verbal information about the project was provided and confidentiality was assured. Transcripts were anonymised prior to analysis. Team review of both the interview structure, which was refined as interviews progressed in both datasets (including more targeted questions to elicit nuances such as local capacity to conduct research) and also informed refinement of the framework analysis,10 enhanced dependability in research findings and qualitative rigour through developing credibility and transferability.11

bmjopen-2019-030815supp001.pdf (99.6KB, pdf)

Ethical considerations

The study was supported and facilitated by the NIHR Critical Care Specialty Group (NIHR CCSG). No ethical approval or written consent, as per the UK Health Research Authority, was required since only anonymised data with staff were used. No local institutional research and development approval was deemed necessary, since this was a project to represent views on behalf of the NIHR CCSG and recruitment did not take place via institutions. Demographic data about each critical care unit’s research activity and staffing were also collected. Participation was voluntary and verbal consent was obtained both before and after the interview, to allow interviewees the opportunity to withdraw/withhold any data discussed.

Settings

Two purposive samples were recruited, with the aim of representing different regions and professional grades (critical care nurses, trainees, trial co-ordinators and consultants) across the UK. The purposive sampling technique involved maximum variation sampling,12 using UK trial accrual and activity data from the NIHR. The aim was to include clinicians representing critical care units across the 16 CRNs (15 in England, one in Wales). Specifically, the second dataset focused on units with limited trial recruitment, or engaged in few trials. We did not ascribe a set value to define ‘less research active’, but focused on unit-level activity in terms of participants recruited and active studies, according to NIHR yearly summary data. The NIHR centralises this information in a ‘portfolio’, and all sites are required to submit this information. Invites were circulated via the NIHR network using established mailing lists, and targeted recruitment to ensure unbiased representation. Using the principles of theoretical sampling (as used most commonly in Grounded Theory),13 14 a sample size of 20–30 interviews was deemed sufficient to reach data saturation and build up a comprehensive picture of the UK landscape in relation to factors that influence critical care research provision.

Analysis

Themes were explored at an overall and ICU-specific level. Potential barriers/facilitators within individual critical care units, hospitals, locally and nationally were identified. In both datasets, analysis was conducted using thematic analysis, a technique congruent with different types of qualitative research,15 aided by principles of framework analysis,10 where categories were refined as analysis progressed. Data from verbatim transcripts were coded at a line level, with subthemes derived from those codes applied to a framework, with constant comparison. Datasets were compared and contrasted, and a new framework was devised, and all data were reanalysed according to this. An independent researcher verified the analysis on anonymised data to enhance dependability and we coded to reach consensus in the case of coding differences. The framework provided a further degree of dependability with regard to analysis,11 and allowed for contextual differences to emerge. The matrix provided detail of within case and cross-case analysis14 which was developed into themes.

Findings

In dataset 1 (collected in 2015), 10 interviews were conducted across nine CRN regions across England (n=8) and Wales (n=1). Dataset 2 (collected 2016/17) included 17 interviews conducted across 12 English CRNs. Two CRNs were not represented due to lack of response. Interviews ranged from 29 to 81 min (mean length was 45.2 min). The framework analysis for each studies yielded six main themes. Demographics are supplied in online supplementary file 2.

bmjopen-2019-030815supp002.pdf (165.2KB, pdf)

Overarching findings from synthesis

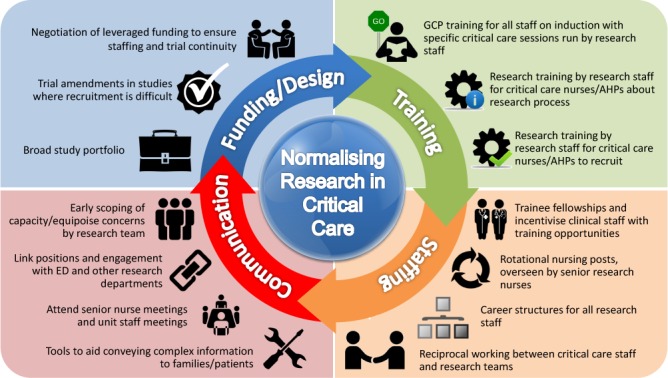

There was an overarching theme of normalising research, describing the notion that critical care research should be entrenched in routine practice. Six sub-themes existed around this central tenet: organisational, human and unit resources, study, clinician and patient/family factors. Resource issues permeated each theme to a different extent and were evident throughout the organisational, unit, study or trial level, and at a human, individual level. Resources could be managed and influenced at an individual level, for instance. In centres, units and teams where research activity was regarded with equal importance as clinical activity, research was considered routine practice. In turn, teams and individuals with a strong sense of integrating research in routine practice acted as the motivating driving force fostering a research culture, whether in primary, translational biomedical or applied health services streams. A broader cultural influence from organisations was also evident, where research was seen as critical to organisational values, up to executive level, which in turn contributed to enhanced research activity. Barriers and enablers to trial recruitment and conduct are outlined in each theme below. A summary of these factors is outlined in online supplementary file 3 and represented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Normalising research. AHP, Allied Health Professional; ED, emergency department; GCP, Good Clinical Practice.

bmjopen-2019-030815supp003.pdf (68.7KB, pdf)

Organisational factors

This theme related to the organisational system in which units were situated, and incorporated Trust or Board level factors; perceived priority of research; infrastructure; trial planning; funding and external links, such as academia. Research-active and less research-active institutions contrasted with regard to prioritisation of research activity by senior management, with the latter placing lower profile on the support and conduct of research. This was particularly marked at challenging times, for example, during care failure reports, or financial or bed crises, even though these could be opportune periods for potential trial enrolment.

Research and development is not high profile. At an organisational level it is service driven, research is seen as an aside and there is no support for it. (Research nurse 2, study 2)

Despite income-generating research activity, such as involvement in commercial studies, increased demand on resources posed a limitation to engagement. Some critical care research leads had to seek executive and/or Research and Development Department (R&D) approval prior to confirming participation, while others could make these decisions unilaterally. Centre factors also determined how trials were embedded through initiatives that increased engagement such as simulated trial runs. Embedding research into routine, or what was perceived as ‘normal’, care required a conceptual shift.

No, research is not a priority. New [intensive care unit] ICU consultants very keen, as are research [specialist registrars] SpRs. The resistance mainly comes from nurses. It is about perceived additional work or disagreement with the protocol…it’s not part of routine care (Research nurse 4, study 1)

Research should be part of everyone’s job. If prescribed it should be given, regardless of it is [part of] research or not. (Research nurse 3, study 2)

The Trust don’t adequately prioritise research; the management don’t ‘get it’ and [the] financial position takes precedence. (Consultant intensivist 13, study 2)

The nature of funding for research nurses, primarily funded via the CRNs and dependent on trial activity levels, created significant challenges to research conduct, given the lack of continuity. Some units ensured varied funding sources beyond the NIHR, to include commercial and higher education, and internally managed their own research budgets. This successfully allowed flexibility in deciding which trials to undertake, and managing staffing and out-of-hours support. Planning for future trials was evidently problematic on occasion. During periods with fewer critical care trials, many research teams broadened activity to cover emergency department (ED) and anaesthetic trials. While this maintained research activity overall, it also resulted in research teams being stretched across many studies and it was hard to focus on critical care trials when activity in this area resumed. For university or university-affiliated hospitals, additional support for research overall could be obtained through links with academia.

We have a historical arrangement with the University that they will fund a unit-based research fellow for a year. (Consultant intensivist 11, study 2)

Human and unit resources

These sub-themes are reported together since they were closely aligned, and incorporated staffing, reciprocity within research and ICU teams, models of provision, management, research opportunities and career structures (nurses/trainees). Staffing was a factor affecting research delivery. Varied models existed for staffing research teams, from rotational and secondments out of critical care, cross-hospital site and cross-specialty working, to research staffing being managed via the CRN. Most research staff had a clinical critical care background which facilitated fluid working arrangements and carryover of research skills to non-research staff.

We instigated rotation of 3 months from ICU into the research team for 3 months, introducing fresh people and it invigorated the team. (Research nurse 15, study 2).

Many participants commented that while critical care research staff could cover other specialties, reciprocal cover for critical care was less successful given the unique patient population and the time-limited nature of recruitment, and this was often poorly appreciated by hospital R&D and regional CRN level. Research staff with a clinical background in critical care found communication easier and were able to support clinical staff, thus developing a mutually beneficial working relationship and helping with the normalisation of research. Grading of research nurse positions and lack of career development was identified as problematic; line management (direct management of the individual) was at times with the regional CRN offices, rather than the local critical care unit. Some research-active centres created attractive positions that afforded career progression and mitigated against job insecurity, a common feature of research nurse roles that are primarily funded on a yearly contract basis via the CRNs.

The career ladder is limited for them and so they move to management or work in R&D roles, and the use of temporary contracts is demoralising and a disincentive. (Consultant intensivist 1, study 1)

Few consultants received programmed activity sessions specifically for research, especially within non-university affiliated hospitals. Many clinicians relied on financial support and time from their organisations to undertake research activity.

They do it effectively out of interest, there is nothing in their job plan apart from a reference to research, but no time to actually do it…it is voluntary and many don’t do it (Research nurse 4, study 2)

This lack of support overlaps with the organisational theme; allocated time and finances to support research activity was rare, occurring only in centres where research was viewed as core activity. Few medical trainees had the opportunity for research involvement, and again primarily only in research-active centres with novel initiatives designed to engage those interested in research, for example, year-long fellowships where research activity contributed to their training programme. Limited time was also a factor: “we have had less [trainees] over the years, enthusiasm fades and other things take over” (Consultant intensivist 9, study 2). However, short clinical placements precluded meaningful trainee participation in primary research.

They mainly don’t get involved and when [they do], they don’t do their own research (Research nurse 15, study 2)

Designated trial coordinators were rare in smaller non-university-affiliated hospitals with less opportunity to enrol patients. Unit, staffing and centre factors were closely associated in the two datasets. Unit factors pertained to strategies to enhance engagement, provision, recruitment and delivery of critical care research. These varied from simulated runs of screening, recruitment and intervention, to teaching programmes and incentive schemes. Having a physical presence on the unit was seen as a crucial element for ensuring clinical credibility.

You need to be there, being present, going on ward rounds and to handovers… (Research nurse 14, study 2).

Driven individuals were critical to success in recruitment and study conduct, with both research nurses and consultants assuming principal investigator roles.

Study/trial factors

This sub-theme was characterised by study practicalities and how studies could be actualised within internal and external constraints. There were process and infrastructure issues associated with studies that affected the team’s ability to conduct the trial.

Trial complexity appeared a considerable factor contributing to trial success, in terms of acceptance by local staff and potential ability to achieve recruitment targets.

The complexity of the study and study information is a problem, for staff as well as families… It’s easier to explain CTIMPS [Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal Products] vs devices and it’s easier to gain consent in a complex study with a family who can understand. (Consultant intensivist 2, study 1).

Feasibility and capacity assessment moderated concerns about delivering to time and target, a national metric captured by the NIHR CRN. Studies requiring significant pharmacy support, such as Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal Products (CTIMPS) had variable success with implementation and recruitment. Some units reported pressure from the regional CRN and local R&D departments to undertake high-recruiting studies that yielded maximum income generation, rather than complex studies perceived as interesting but with low recruitment targets that might yield less or insufficient income to cover costs. Demonstrating quick, tangible ‘wins’ for an organisation and staff, through health service research, helped engagement.

Complex studies were considered problematic for balancing effort against outcomes achieved, in particular around training requirements for staff to implement detailed interventions, and strict eligibility criteria with narrow recruitment windows leading to few, if any, patients enrolled. Studies requiring significant preparation, including co-enrolment agreements, time-scheduling, competing population assessment and importantly, ensuring unit staff were committed and had clinical equipoise, could be particularly challenging:

they say they have equipoise, but when it comes down to it, they don't, you get surreptitious opposition and stark persuasion is used in those situations. (Consultant intensivist 1, study 1)

Time associated with daily screening was also a factor influencing success of complex trials, as often this could not be performed remotely and required extensive clinical data review. In keeping with study set-up, funding was rarely allocated for this activity, or for follow-up. In units where research was considered part of routine practice, clinical staff also helped with identification of potential participants.

There needs to be appropriate costing of studies including NHS support costs, for drugs for example…long-term follow-up needs to be considered as well. (Consultant intensivist 6, study 2)

Strategies to facilitate complex trials included engagement with local clinical staff on the relevant unit to integrate the trial procedures with standard care, thereby enabling all staff to contribute to patient screening and enrolment, including out-of-hours. Units could achieve this through training and cross-team working.

Clinician factors

This theme focused on how unit clinicians, nurses, trainees and intensivists, were perceived as engaged in research; this did not appear linked to how research-active an organisation was. Where research staff originated from the unit this was a facilitator, often resulting in good team working from both clinical and research team perspectives.

We try to pick out staff nurses with initiative and encourage them to apply [for research posts]. We’ve had some on the team who’ve worked in ICU, which helps, although where there is history it can create problems. (Research nurse 3, study 2)

We are line managed by critical care staff, which is good, rather than by R&D and we both then have influence in critical care. (Research nurse 5, study 2)

Where research was viewed as additional activity, rather than integral to patient care, research staff reported cases of open hostility, particularly early on in their roles, until unit staff developed an appreciation for research.

I’ve tried working on the unit and taking patients and doing shifts to build relationships (Research nurse 7, study 2)

Research resources were factored by unit staff where there was good inter-boundary working. For instance, research staff attended senior nurse meetings to identify local issues that might adversely affect recruitment. Equally, unit staff could help identify barriers to recruitment to certain studies. Creating link roles supported nurse-level engagement and enhanced out-of-hours opportunities for recruitment when research nurses were not present. Very limited funding for out-of-hours cover enforced the need for research nurse flexibility.

Equipoise featured again in this theme; clinicians could undermine research activity by appearing supportive in meetings, but not in practice. Permission to recruit patients had to be negotiated at an individual clinician level, which could compromise unit objectivity toward the study.

The consultants are all GCP [Good Clinical Practice] trained but there is mixed interest and support, ranging from active obstruction…, to more neutral through to full support. (Consultant intensivist 9, study 2).

People believe they have equipoise but on the day people change what they do. (Research nurse 5, study 2).

Investment for trainee engagement arose as an important issue, particularly in those less research-active organisations. Ensuring the next generation of critical care consultants prioritised research activity with clinical practice was recognised as imperative. Many trainees were taught to obtain patient consent. At the time of the study, regional trainee research networks were emerging across the UK. However, according to these participants, in larger portfolio NIHR trials trainee engagement was noted to be minimal, and unit pressures contributed to lack of engagement. Trainee fellowship roles successfully addressed this in two units, with staff continuing research in their careers as consultants, with an emphasis on personal motivation.

we actively encourage fellows not to go onto the [unit] rota so that their role is protected for research. (Consultant intensivist 11, study 2)

Personal commitment was a key factor; research activity often required working beyond allocated hours or sessions, or flexible working out-of-hours. This demonstrated how research teams worked to emphasise the sense that research should be considered the norm, with efforts devoted to successful implementation comparable with efforts in clinical practice. Skills of research nurses was a factor common to both datasets, with the ability (and R&D permission) to consent improving recruitment. Extended skills also meant that a number of research nursing staff were supported to undertake further study, including at doctoral level, fostering motivation, willingness to work flexibly and promoting emergence of independent researchers. Portfolio studies requiring a nurse principal investigator particularly motivated nurses. For consultants, feelings were mixed: studies with no personal interest fostered less engagement, unless it was likely to be income-generating.

Patient/family factors

This sub-theme encompassed issues such as participant burden, support available, communication and anticipating declines to participate. Difficulties communicating information about trial procedures to patients and their families was reported by participants. A positive but realistic attitude was deemed essential. The volume of paperwork was identified as problematic. Ensuring that patients or families fully understood complex research interventions, without overburdening them at a sensitive time, was seen as a central issue.

We've got savvier about taking consent and have learnt lessons; you don't gain it by giving more paper. (Consultant intensivist 1, study 1)

Managing clinical uncertainty in the context of clinical trials was difficult. While it did not seem to hinder recruitment, managing the process was challenging for research staff. Many families agreed to assent for patients for altruistic reasons, understanding there may be no benefit to the patient. An important issue emerged in relation to addressing cultural perspectives. Different attitudes were perceived towards research, centring on trust in healthcare. Immediate dismissal by family members, on behalf of patients, was not uncommon. However, sometimes families were keen, but patients were not.

The patient, who was not intubated [breathing tube for mechanical ventilation], had capacity and her family were keen for her to take part, but she wasn’t (Research Nurse 9, study 1).

Conversely, some reported a paternalistic medical attitude still prevailing. Despite efforts to address this, provide more information and demonstrate equipoise, families and patients were reluctant and preferred to defer to doctors’ opinions regarding enrolment.

I work in a deprived area with a lower level of education compared to the UK average, because of that the cultural norms mean they tend to trust what the doctors say: ‘whatever you think doctor’ (Research nurse 11, study 2).

Neither of these opposing views about consent were regarded by participants as hindering recruitment. Units serving a disproportionately elderly or rural population reported difficulties gaining access to relatives for assent, particularly where time-sensitive consent was required. Research teams estimated a third of families were likely to decline participation when calculating recruitment targets and reasons for non-participation appeared to be complex and poorly understood. Where approaches to families were prefaced by an explanation that research was part of normal clinical practice in that particular unit, there was increased receptivity to recruitment. Reported preference for treatment arms was rare, and usually managed through explanation. Facilitating understanding was viewed as crucial when approaching families and patients for consent, with issues related to ongoing assessment of mental capacity also highlighted as difficult.

Discussion

This synthesis outlines six inter-related themes under a new overarching theme of normalising research. Research activity was regarded as equally important as clinical work by these participants, although this was acknowledged as not a representative view across all organisations or units. Where research was embedded into routine care and considered as the norm, undertaking screening and recruitment were easier. Emphasising the need for normalcy of research at a unit, as well as organisational level, means cohesive units evolve with the unified aim of improvements in patient care as the driving force. However, there are prerequisites for normalcy, including communication towards a shared understanding16 in this case, that research is an integral part of everyday patient care. Furthermore, this communication needs to take place at a systems level.16 Specific issues in the synthesis related to variation in funded time and resources, clinician engagement, individual roles and perceived gains from research (which proved noteworthy). Each issue acted as a barrier or facilitator to clinical trial recruitment. Bruce et al1 outlined how navigating rapidly changing clinical courses and communication breakdown adversely affected recruitment.1 That these factors did not emerge in this synthesis may reflect different healthcare systems, funding and the larger number of hospitals. Similarities emerged related to the challenges of recruitment within a narrow timeframe. Good communication between clinical and research teams was important for successful trial implementation.

Inclusion of data from less research-active organisations strengthens this study providing richer data, more transferable across the NHS and to healthcare systems in other jurisdictions. Our findings will resonate with other international settings where, despite variability in national infrastructure, similar challenges are faced by researchers. The tenet of normalising research transcends unit, institutional and country boundaries. Approaches to improve recruitment included simple incentive schemes to reward clinical staff, broadening the range of clinicians who could take consent. The latter is particularly pertinent to CTIMPs where time-limited recruitment was more relevant.1 2 Previous work has suggested lack of equipoise as a barrier to enrolment.17 18 An area for further exploration relates to consent waivers, already explored in some recent research,1 17 19 20 although with less known of patient and family perspectives. ‘Overburdening’ has been described previously21 as concern regarding making initial approaches to families during particularly sensitive times19–23 but again the patient/family voice in these studies is largely absent.19–21 This would be an important area for future practice and research.

In keeping with existing literature, competition between trials requiring similar patient cohorts and the number of eligible patients were further barriers to trial recruitment.1 24 Another factor related to lack of clear professional development opportunities and structured career paths. Recent strategy published by the NIHR offers novel career options for research staff25–27 such as consultant research nurse models.25 The emergence of medical trainee networks across the UK have also helped create a case for formalised processes.28 29 NIHR initiatives to engender a culture of research in healthcare, with every patient being offered the opportunity to participate in research aimed at improving care30 are also reflected in these individual participants’ motivations to improve care through research. Systematic review and large-scale survey evidence highlight key areas to improve trial recruitment as training site staff, communication with patients and incentives, although some suggestions are not applicable to an ICU setting, such as telephone calls to non-respondents and opt-out procedures.31 32 There have been significant advances over the past 5 years in critical care research recruitment.33 In a current climate of significant fiscal pressures in the UK healthcare system with £22 billion of NHS efficiency savings to be achieved by 2020,34 there was still a universal desire to undertake critical care research. This was driven by key motivated individuals who viewed research as integral to best practice and normal care provision, as well as deriving evidence to drive and support best use of resources.

This qualitative synthesis draws together two sets of original research findings. While data were not collected simultaneously, both studies complemented each other. The second study built on the first by focusing specifically on a target participant cohort not initially represented in order to generate novel data to further understand the question at hand. Limitations include the timeframe between acquisition of each dataset which although short (12 months), might have resulted in practice changes occurring between the two data collection points. Potential sampling bias from recruiting primarily research-active units in the first dataset, was mitigated by employing purposive recruitment in the second dataset from less research-active units. Research-active and less research-active units were defined both on subjective reports from individuals, and standardised objective metrics, however this subjective/objective mix and lack of clarity could have introduced further sampling bias. We also only achieved interviews with 14 out of 16 CRNs, potentially missing important information from the other two CRNs. We also acknowledge the possible introduction of bias through refining the interview schedule as we proceeded through the interviews. Qualitative research is often criticised for lack of generalisability, due to sample size limitations, but notions of transferability can be considered8 11 and what Payne and Williams term ‘moderatum generalisations’.35 This is where core conceptual principles from the research, which would make sense across setting can be applied. Figure 1 outlines a summary of the main points and four key areas for learning. The core concept of normalising research can feasibly be applied beyond critical care trials recruitment, across the full spectrum of clinical specialties represented within the NIHR, as well as internationally.

Conclusion

This qualitative synthesis integrating two original datasets has yielded recommendations for improving trials recruitment in the unique clinical specialty of critical care. Several suggestions are made from the six themes that emerged: organisational, human, study, practical resources, clinician and patient/family factors, under the overarching theme of normalising research, that relate to enhanced staffing, training, trial design and communication. Fostering a culture where research is considered part of routine patient care must be the ultimate goal for those working at all levels, from organisational to bedside.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the NIHR National Specialty Group for Critical Care, on whose behalf we conducted this project. We would also like to thank Carys Jones for her support in this project and all the participants who gave up their time to contribute.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drnatpat, @bronwenconnolly

Contributors: NP conceived the project and was the lead, undertaking primary data collection and analysis of the two datasets, and the overall synthesis. GOG independently verified the first dataset and contributed to data analysis of the second dataset. NA contributed to the design, data collection and manuscript write-up. PD, PH and TW contributed to the design. SH and BC contributed to data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors have reviewed and contributed to the manuscript. NP is the custodian of the intellectual integrity and property arising from this project.

Funding: This project was supported with infrastructure from the National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Research Network in Critical Care (NIHR Theme Hub C King’s College London).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Bruce CR, Liang C, Blumenthal-Barby JS, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to initiating and completing time-limited trials in critical care. Crit Care Med 2015;43:2535–43. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaur G, Smyth RL, Williamson P. Developing a survey of barriers and facilitators to recruitment in randomized controlled trials. Trials 2012;13:218 10.1186/1745-6215-13-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pattison N, Arulkumaran N, Humphreys S, et al. . Exploring obstacles to critical care trials in the UK: a qualitative investigation. J Intensive Care Soc 2017;18:36–46. 10.1177/1751143716663749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) , 2016. Available: http://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us [Accessed 21 Jan 2017].

- 5. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Health Research Authority Defining research. Available: http://www.hra.nhs.uk/documents/2016/06/defining-research.pdf [Accessed 24 May 2017].

- 7. Heyvaert M, Maes B, Onghena P. Mixed methods research synthesis: definition, framework, and potential. Qual Quant 2013;47:659–76. 10.1007/s11135-011-9538-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finfgeld-Connett D. Generalizability and transferability of meta-synthesis research findings. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:246–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eaves YD. A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. J Adv Nurs 2001;35:654–63. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research : Bryman A, Burgess R, Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge, 1994: 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. 198 Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suri H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual Res J 2011;11:63–75. 10.3316/QRJ1102063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of Grounded theory. strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded Sourcebook. 2nd Edn Thousand Oaks, California, US: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Habermas J. The theory of communicative action, volume 2: Lifeworld and system: a critique of functionalist reason. Beacon Press Boston MA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morgenweck CJ. Innovation to research: some transitional obstacles in critical care units. Crit Care Med 2003;31:S172–7. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000054898.32355.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Donovan JL, de Salis I, Toerien M, et al. . The intellectual challenges and emotional consequences of equipoise contributed to the fragility of recruitment in six randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:912–20. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bigatello LM, George E, Hurford WE. Ethical considerations for research in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2003;31:S178–81. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000064518.50241.fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim DAFN, Chan M, Childs C. Surrogate consent for critical care research: exploratory study on public perception and influences on recruitment. Crit Care 2013;15 10.1186/cc11927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehta S, Pelletier FQ, Brown M, et al. . Why substitute decision makers provide or decline consent for ICU research studies: a questionnaire study. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:47–54. 10.1007/s00134-011-2411-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dear RF, Barratt AL, Tattersall MHN. Barriers to recruitment in cancer trials: no longer medical oncologists’ attitudes. Med J Aust 2012;196:112–3. 10.5694/mja11.10895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. . Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker*. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2281–6. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182533317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dickson S, Logan J, Hagen S, et al. . Reflecting on the methodological challenges of recruiting to a United Kingdom-wide, multi-centre, randomised controlled trial in gynaecology outpatient settings. Trials 2013;14:389 10.1186/1745-6215-14-389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Currey J, Considine J, Khaw D. Clinical nurse research consultant: a clinical and academic role to advance practice and the discipline of nursing. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:2275–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05687.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Institute for Health Research NIHR clinical research network: developing our clinical research nursing strategy 2017-2020, 2017. Available: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/our-faculty/clinical-research-staff/clinical-research-nurses/Clinical%20Research%20Nurse%20Strategy%202017_2020FINAL.pdf [Accessed 1 Sep 2018].

- 27. National Institute for Health Research NIHR clinical research network: NIHR CRN allied health professionals strategy 2018-2020, 2018. Available: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/our-faculty/clinical-research-staff/Allied%20Health%20Professionals/Allied%20Health%20Professionals%20Strategy%202018_20.pdf [Accessed 1 Sep 2018].

- 28. Shaw M, Harris B, Bonner S. The research needs of an ICM trainee: the raft national survey results and initiatives to improve trainee research opportunities. J Intensive Care Soc 2017;18:98–105. 10.1177/1751143716689276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moore JN, McDiarmid AJ, Johnston PW, et al. . Identifying and exploring factors influencing career choice, recruitment and retention of anaesthesia trainees in the UK. Postgrad Med J 2017;93:61-66 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown H, Hewison A, Gale N, et al. . Every patient a research patient. evaluating the state of research in the NHS. A report commissioned by CRUK: University of Birmingham, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bower P, Brueton V, Gamble C, et al. . Interventions to improve recruitment and retention in clinical trials: a survey and workshop to assess current practice and future priorities. Trials 2014;15:399 10.1186/1745-6215-15-399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Treweek S, Mitchell E, Pitkethly M, et al. . Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;1 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walsh T, Brett SJ. What are the priorities for future success in critical care research in the UK? report from a national stakeholder meeting. J Intensive Care Soc 2015;16:287–93. 10.1177/1751143715588101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dunn P, McKenna H, Murray R. Deficits in the NHS 2016. The kings fund. Available: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/deficits-nhs-2016 [Accessed 1 Sep 2018].

- 35. Payne G, Williams M. Generalization in qualitative research sociology 2005; 2005: 295–314.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030815supp001.pdf (99.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030815supp002.pdf (165.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030815supp003.pdf (68.7KB, pdf)