Abstract

Background

Nusinersen has been used to treat spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1) in the UK since 2017. While initial trials showed neuromuscular benefit from treating SMA1, there is little information on the respiratory effects of nusinersen. We aimed to look at the respiratory care, hospital utilisation and associated costs in newly treated SMA1.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of all children within the West Midlands with SMA1 treated with nusinersen at Royal Stoke University Hospital. Baseline demographics and hospital admission data were collected including: the reason for admission, total hospital days, days of critical care, days intubated, discharge diagnosis, doses of nusinersen and treatment complications.

Results

11 children (six girls) received nusinersen between May 2017 and April 2019. Their median (range) age was 29 (7–97) months. The median (range) number of nusinersen doses per child was 6 (4–8). All children were receiving long-term ventilatory support; this was mask ventilation in nine and tracheostomy ventilation in two. The total number of hospital days since diagnosis was 1101 with a median (range) of 118 (7–235) days per child. This included general paediatric ward days 0 (0–63), High Dependency Unit 79 (7–173) days and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit 13 (0–109) days per child. This equated to a median (range) of 20 (2–72) % of their life in hospital. The estimated cost of this care was £2.2M.

Conclusion

Patients with SMA1 treated with nusinersen initially spend a considerable proportion of their early life in hospital. Parents should be counselled accordingly. These data suggest that for every 10 children started on nusinersen an extra HDU bed is required. This has a significant cost implication.

Keywords: respiratory, neuromuscular, neurodisability, costing

What is already known on this topic?

Nusinersen improves prognosis and life expectancy in children with spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1).

Infants are now surviving with considerable dependency on healthcare services.

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence agreed to fund this new treatment in May 2019.

What this study adds?

Children with SMA1 who receive nusinersen have significant ongoing medical costs in addition to the cost of the drugs received.

On average this currently is more than £100 000 per patient per year in the first two years of follow-up.

Associated healthcare costs reduce as time progresses and are less in the second year of life.

Background

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disorder characterised by progressive muscular atrophy and weakness.1 It has an incidence of one in 11 000 live births.2 There are various subgroups of SMA classified clinically, with SMA type 1 (SMA1) accounting for approximately 60% of cases, and carrying the worst prognosis.3 Until recently, SMA1 was the most common genetic disease resulting in death in infancy.4 Affected children usually present with symptoms before 6 months of age and historically died from respiratory failure by the age of 2 years.5

SMA1 is caused by the homozygous deletion or mutation of the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. This results in reduced expression of the SMN protein, which is essential for the survival of motor neurones in the spinal cord and brain stem.6 Inadequate expression of SMN protein causes degeneration of the motor neuron which in turn causes the associated muscles to atrophy. Humans have a variable number of copies of a second gene, SMN2 which also encodes for SMN protein.6 However, SMN2 transcription in 80%–90% of instances leads to production of a truncated, unstable form of the protein which is non-functional. Approximately 80% of infants with SMA1 have only one or two copies of SMN2 and are therefore unable to produce enough functional SMN protein to support normal muscle development.

Nusinersen is an antisense oligonucleotide which works by binding to the SMN2 mRNA and in order to be effective it must be delivered into the cerebrospinal fluid. This binding modifies splicing of the SMN2 gene to promote increased production of functional SMN protein.7 Treatment with nusinersen has the potential to transform prognosis for these children offering hope of treatment for the first time. The drug has been used in the UK since early 2017. The drug costs £450 000 in the first year and £225 000 per annum subsequently. For patients beginning this before November 2018, the manufacturer provided it free through an Expanded Access Programme.8 The National Health Service in England (NHSE) commissions an administration cost, but not the other aspects of care for these patients. While randomised controlled trials showed nusinersen improved motor function and development,7 it is unclear whether the respiratory consequences produce similar benefits and thus the demands of treatment for families and health economies is yet to be established.

Royal Stoke University Hospital (RSUH) is the regional centre for nusinersen administration in the West Midlands which has a population of approximately 6 million. In March 2019 RSUH had the second largest cohort of SMA1 patients in the UK. Before agreeing to act as a regional centre for nusinersen delivery, we carefully considered the potential effects on children, their families and other healthcare services. However, data were lacking making counselling of families and planning of service provision difficult. We have carefully monitored healthcare utilisation of SMA1 children treated with nusinersen. The aim of this article is to report the data on service utilisation for these children to assist families and healthcare professionals.

Methods

Patients treated with intrathecal nusinersen at RSUH were identified from a local database. The paper notes and electronic clinical records were reviewed to collect relevant data from RSUH and the child’s referring hospital. This included baseline demographics, age at diagnosis, details of ventilatory support, feeding support, number of nusinersen doses, complications following administration and details of all hospital admissions. Hospital admission data included: duration of admission, number of High Dependency Unit (HDU) days, Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) days and intubated days. Nusinersen usually necessitated admission for one night for the first dose only. All children received care in accordance with the published international guidelines for the care of children with SMA.9 10 Intrathecal nusinersen was administered by appropriately trained paediatricians in the PICU treatment room. In babies this was performed using local anaesthetic and in toddlers using low dose opiate analgesia and/or sedation. No child has required a general anaesthetic or interventional radiology.

Results

We identified eleven children (six girls) who received nusinersen through the Expanded Access Program at RSUH between May 2017 and April 2019. Parents of a twelfth child declined nusinersen and the child died at 3 months of age. The median (range) number of nusinersen doses was 6.4–8 Nine children received mask ventilation and two children were ventilated via tracheostomy (TIV). Six children had been commenced on ventilation prior to their first dose of nusinersen. Both patients receiving TIV had the tracheostomy inserted before nusinersen was commenced. Two patients (including one on tracheostomy ventilation) have died suddenly at home from presumed mucous plugs at 12 and 16 months of age, while one other patient had a cardiorespiratory arrest and has suffered hypoxic brain injury.

Duration and location of admissions

In 24 months, the 11 children had spent a total of 1101 days in hospital. Details of the hospitalisation are summarised in table 1. Three children were responsible for all admissions to the general paediatric ward which occurred at their local hospital. During these admissions, the respiratory team at RSUH liaised closely with local providers to guide acute management and arranged transfer when necessary. Three children had not been admitted to PICU. Of the eight children that had, six had been intubated for a total of 38 days. The median (range) proportion of life spent in hospital was 20% (2%–72%). This was variable with four children spending ≤10%, four 10%–35% and three >35%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort

| Median | Range | |

| Age at diagnosis (months) | 6.5 | 3.5–21 |

| Age of first dose nusinersen (months) | 8.1 | 0–85.7 |

| Age at initiation of Long Term Ventilation (months) | 8.1 | 2.3–36.5 |

| Age at initiation of advanced care pathway (n=4) (months) | 21.3 | 7.1–70.8 |

| Number of admissions per child* | 11 | 1–25 |

| Number of emergency admissions per child* | 3 | 0–21 |

| Number of elective admissions per child* | 4 | 0–9 |

| Hospital days per child* | 84 | 7–235 |

| General paediatric hospital days per child* | 0 | 0–63 |

| HDU days per child* | 79 | 7–173 |

| PICU days per child* | 13 | 0–109 |

*Over 24 months.

Reason for admission

The median age (range) for initiation of nusinersen was 8.1 (0 - 85.7) months. Since initiation of nusinersen the 11 children had a total of 107 hospital admissions with a median (range) per child of 11 (1–25). The most common reason for admission was lower respiratory tract infection (n=42), followed by elective administration of intrathecal nusinersen (n=38). There were seven admissions for gastrointestinal issues, six for an elective sleep study, five for aspiration pneumonia, four for increased secretions or airway issues and three for optimisation of ventilatory support. At each admission for nusinersen the patient and family were reviewed by the paediatric palliative care team who administered intrathecal treatment and assessed palliative needs. Children also received physiotherapy while inpatients. The physiotherapy adjuncts used by patients are listed in table 2. Four children had advanced care pathways in place. Between hospital admissions all the children were reviewed regularly in the outpatient clinic by the multi-disciplinary members of the Paediatric Respiratory Service.

Table 2.

Physiotherapy adjuncts that SMA1 children required

| Physiotherapy adjunct | Number (percentage) of children requiring adjunct |

| Saline nebulisers | 8 (72%) |

| Suction | 11 (100%) |

| Percussion | 9 (82%) |

| Cough assist machine | 5 (45%) |

| High frequency chest wall oscillation vest | 1 (9%) |

SMA1, spinal muscular atrophy type 1.

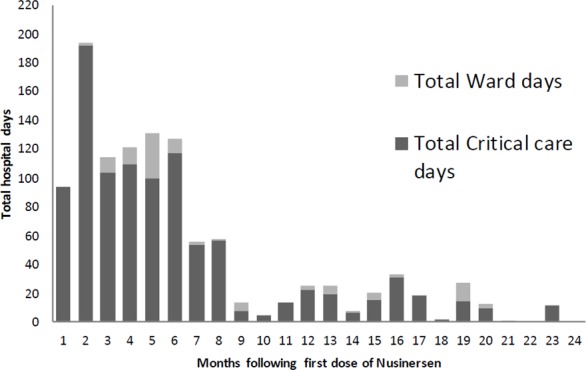

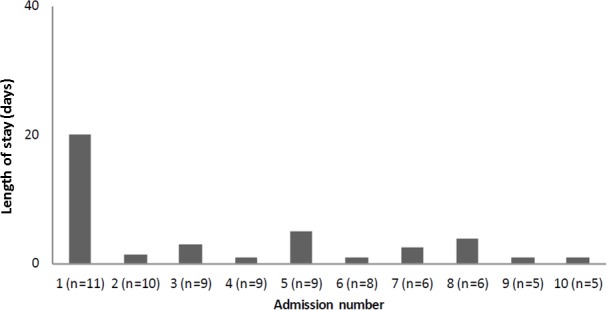

Trends in admissions

Children in our cohort had the greatest requirement for hospital admission in the first 6 months following nusinersen initiation (see figure 1). Much of this effect is driven by a tendency for children to have a long first admission (see figure 2). Subsequent admissions tend to be shorter. The total number of hospital days for the children’s first admission was 426 days with a median (range) of 20 (1–235) days per child.

Figure 1.

Total hospital days per month spent by children following commencement on nusinersen.

Figure 2.

Median length of hospital stay per admission for all children.

Cost implications and impact on local services

A total of 762 HDU days and 248 PICU days were required by the 11 children in our cohort over 2 years. This equates to 2.8 days in HDU and 0.93 days in PICU per child each month. RSUH has six HDU (four acute HDU beds and two long term ventilation) and eight PICU beds. The children therefore occupied 17% of the total HDU capacity and 4.2% of the PICU capacity over the study period. Based on current estimates of £1626 per day for an HDU bed and £1785 to £3784 for a PICU bed (depending on the level of care), the additional cost of these HDU/PICU days is £2.2M.11 This is separate to the cost of the nusinersen and its administration.

In addition to the costs associated with inpatient care, these children frequently require care packages which incur additional community costs. These costs are likely to continue throughout the child’s life. In this small cohort, we found families highly motivated to provide care for their children and no child experienced a prolonged hospital admission as a result of awaiting funding for the provision of a care package. Four children had care packages implemented: one child had 16 hours of care a week and three of the children had over 85 hours care per week. These three children received care seven nights a week between 9–10 hours and 3 days a week between 5 and 8 hours. One with a large care package had tracheostomy ventilation, but the parents of the other child with tracheostomy declined a care package.

Discussion

This is the first study which reports the inpatient healthcare utilisation of a cohort of children treated with nusinersen. This information is vital for those planning hospital healthcare services. In the first 2 years after diagnosis, these children spend, on average, one fifth of their early life in hospital although there is considerable inter-individual variation. This places a significant burden on parents and families and they should be counselled accordingly. There is a considerable impact on hospital services, particularly on high dependency and PICU. However, not all children required PICU admission and not all children admitted to PICU required endotracheal intubation. This involves a substantial extra resource, in addition to the direct cost of the nusinersen. Reassuringly, the number of hospital days has reduced as the child grows older. In our cohort, the 11 children required 762 HDU days over 24 months. This equates to the need for an additional HDU bed for every 10 children commenced on nusinersen.

NHSE has decided to fund nusinersen for the next 5 years so the numbers of SMA1 patients surviving and treated with nusinersen will increase, along with the demand on critical care and community services. Currently there is no ring-fenced funding for the health needs of SMA1 patients receiving nusinersen and this is something that must be explored to provide optimal care for these patients without affecting that of other children requiring critical care or general paediatric services. Only a small proportion of admissions was managed wholly at the children’s local hospital where expertise in NIV is being slowly developed.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. It includes only eleven patients treated at one centre, although this is the second largest in the UK. The retrospective nature of the study may have introduced bias and we did not adjust for potential confounding factors such as socioeconomic status and comorbidities. Given the small numbers of children in this cohort we have elected not to report a detailed phenotype and correlation to healthcare utilisation as any observed correlations may be spurious and open to misinterpretation. Instead, we have chosen to consider the cohort as a group as this allows funders, clinicians and those planning healthcare services to make better informed decisions. Estimates of the financial burden have concentrated on inpatient rather than community costs and will therefore be an underestimate. We could not undertake an accurate review of healthcare costs in our region for children with SMA1 prior to the introduction of nusinersen as most children did not receive active treatment and died in their local hospital. A recent German study estimated the total direct cost of illness for children with SMA1 to be €99 664 per year.12

As the children grow older, there is a fall in the number of days spent in hospital. This is in part due to a prolonged first admission, during which the child was stabilised and the family were trained and counselled. It may also be explained by: (1) a true improvement in the respiratory muscle strength of these children over time, or (2) a gradual improvement in the medical care provided, or (3) an improved ability of these families to cope with their medical conditions at home and in their own community or (4) deaths within our cohort. While an important consideration, mortality alone seems unlikely to be the sole driver of this effect as only two children within the cohort have died. It may be a function of all of these and we hope that the first three factors will continue to operate.

Conclusion

While the improved prognosis and life expectancy associated with nusinersen treatment is exciting for children with SMA1 and their families, we remain unsure that the respiratory benefits are as great as that shown for the neurological improvement in the preliminary trials. This study has highlighted that such children will spend a significant amount of their life in hospital, particularly in the first months after diagnosis. This places a significant burden on families and on the National Health Service in general. The long-term outcome for these children is still unknown but the trend for a reduction in hospital days as the child grows older may be reassuring. Further prospective studies with larger patient numbers are required to more accurately quantify the longer term healthcare utilisation by these children and the associated financial burden.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @will.carroll@nhs.net

Contributors: MS and JA originated the design of the study. IA collected the data and drafted the manuscript. FJG and MS supervised the writing. IA, FJG, WDC, MS, JA, SC, TW and RK revised each draft for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MS had primary responsibility for the final content and is the guarantor. The corresponding author (MS) attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures. The results of this study will be shared with commissioners and patient groups such as SMA UK and MD UK.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The HRA decision tool (http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research) confirmed this project was audit not research and so ethical approval was not sought. The audit was approved by the departmental governance lead.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Pearn J. Incidence, prevalence, and gene frequency studies of chronic childhood spinal muscular atrophy. J Med Genet 1978;15:409–13. 10.1136/jmg.15.6.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kolb SJ, Kissel JT, Atrophy SM. Spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin 2015;33:831–46. 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verhaart IEC, Robertson A, Wilson IJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q–linked spinal muscular atrophy – a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:124 10.1186/s13023-017-0671-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wirth B. An update of the mutation spectrum of the survival motor neuron gene (SMN1) in autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Hum Mutat 2000;15:228–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park HB, Lee SM, Lee JS, et al. Survival analysis of spinal muscular atrophy type I. Korean J Pediatr 2010;53:965–70. 10.3345/kjp.2010.53.11.965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burghes AHM, Beattie CE. Spinal muscular atrophy: why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:597–609. 10.1038/nrn2670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finkel RS, Chiriboga CA, Vajsar J, et al. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: a phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. The Lancet 2016;388:3017–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31408-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. NICE project team Nusinersen for treating spinal muscular atrophy [Internet]. NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE, 2018. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ta10281/documents/appraisal-consultation-document [Accessed cited 2019 Nov 1].

- 9. Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscular Disorders 2018;28:197–207. 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscular Disorders 2018;28:103–15. 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NHS improvement National cost collection guidance 2019 [Internet]. NHS, 2019. Available: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/4883/National_cost_collections_19.pdf [Accessed cited 2019 Apr 2].

- 12. Klug C, Schreiber-Katz O, Thiele S, et al. Disease burden of spinal muscular atrophy in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:58 10.1186/s13023-016-0424-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.