Abstract

Objectives

Although depressed patients may have a comorbid eating disorder (ED), to date, no study has focused on healthcare utilisation among this population. This study was designed to investigate the characteristics of healthcare service utilisation among depressed patients with ED.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

This population-based study used claims data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research database between 2001 and 2012.

Participants

The study involved 1270 participants. These included 254 depressed individuals with ED and 1016 propensity score-matched depressed individuals without ED.

Outcome measures

We tracked each patient for a 1 year period to evaluate their healthcare service utilisation, including outpatient visits, inpatient days, and costs for psychiatry and non-psychiatry services. We performed a Mann-Whitney U test to compare outcome variables in healthcare service utilisation between the two groups.

Results

Patients with both depression and ED had significantly more outpatient visits (32.2 vs 28.9, p=0.023), outpatient costs (US$1089 vs US$877, p<0.001) and total costs (US$1356 vs US$1296, p<0.001) than comparison patients. For psychiatric services, patients with depression and ED had more outpatient visits (11.0 vs 6.8, p<0.001), outpatient costs (US$584 vs US$320, p<0.001) and total costs (US$657 vs US$568, p<0.001) than those without ED. For non-psychiatric services, there was no significant difference for all utilisation. This indicates that the total costs were about 1.0-fold greater for depression patient with ED than those without ED.

Conclusion

Depression patients with ED had more outpatient visits, outpatient costs and total costs of healthcare services than those without ED.

Keywords: healthcare, utilization, eating disorder, depression, health services utilization

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first Asian study to investigate the characteristics of the healthcare utilisation and costs of depressed patients with eating disorder.

This study was a cross-sectional study using a large population-based dataset with extensive health welfare coverage from Taiwan.

The advantage of this study was the use of data from a single-payer system national health insurance programme.

This study did not estimate indirect costs or intangible costs, such as societal costs (eg, productivity losses and informal caregiving).

As the dataset used in this study lacked figures for out-of-pocket fees, this study might underestimate hospital treatment costs.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are psychiatric disorders characterised by both physical and psychological disturbances. The core symptoms of eating disorder (ED) include abnormal eating patterns and weight control behaviour. These illnesses affect not only psychological, social, occupational, and quality of life factors, but also increase mortality rates.1 2 EDs include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). The majority of ED occur among women, and they have high rates of comorbidity with mental illness, especially depressive disorders.3–8 Specifically, depression is one of the most common mental illnesses in the world and is expected to become the second-largest cause of global disease burden worldwide by 2020.9 Studies have also reported on its economic burden.10–12 The cost of depression is high, and it is associated with suicidal risk.13 Previous studies suggest that the use of healthcare services by depressed patients exceeds that of similar non-depressed patients by 50%–100%.14 In Taiwan, the cost of depression increased continuously between 2000 and 2002,15 and the use of three kinds of psychotropic drugs also increased greatly from 1977 to 2004.16 Nevertheless, depression is the most common comorbid diagnosis among patients with ED17 18 and the development of the two overlaps. The lifetime comorbidity of depression has been reported as 40% among patients with AN and 50% among patients with BN.19 Comorbid depressive symptoms have been found to have negative impacts on patients with ED.20 Despite the above-mentioned findings, the relationship between ED and depression is still unclear.

Many studies have indicated that depression occurs before ED diagnosis.21–24 Our previous work also found that the risk of suicide was 1.8 times higher among patients with ED with pre-existing comorbid depression.5 However, few studies have investigated healthcare utilisation preceding ED diagnosis.25–27 One study reported that the healthcare costs of ED are similar to those of depression.25 However, there is little knowledge about the use and cost of services after diagnosis.28 29 Another review article stated that early (1982–2002) studies of health service use and costs for ED employed limited evidence and underestimated the costs; the review speculated that the economic burden is likely to be substantial.30

According to our review of the relevant literature, no study thus far has focused on the healthcare utilisation of depressed patients with ED in Western or Asian countries. Our previous work showed that patients with both depression and ED warrant special care as they might respond poorly to the usual treatments and be at a higher risk of suicidality. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate healthcare utilisation and expenditures among depressed patients with and without ED in Taiwan. We further compared psychiatric and non-psychiatric healthcare utilisation between depressed patients with and without ED. We hypothesise that there have been increases in healthcare utilisation in depression patients accompanied by ED, even after other comorbidities have been matched.

Methods

Database

This study used the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID 2005), derived from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which contains the data of over 99% of the people (around 23 million residents) in Taiwan. This is a single-payer National Health Insurance Program begun on 1 March 1995. The LHID 2005 contains all original claims data from 25.68 million beneficiaries randomly sampled in the year 2005 from the NHIRD. There was no significant difference in the gender or age distributions of the patients in the LHID 2005 and the original NHIRD. Disease diagnosis was performed using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes.

Study participants and design

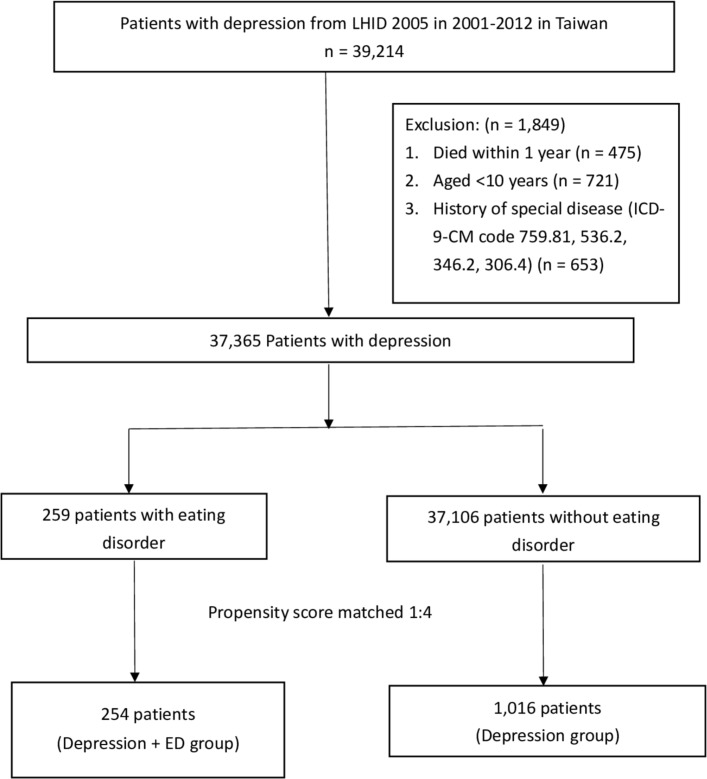

In total, 39 214 patients included in the study had a major depressive disorder and neurotic depression (ICD‐9‐CM codes 296.20 to 296.26, 296.30 to 296.36, 296.82 and 300.4) between 2001 and 2012. The patients with three or more outpatient visits or at least one hospitalisation were identified as depression cases. We excluded 475 subjects who died within 1 year, 721 children aged <10 years and 653 subjects with histories of special diseases (ICD‐9‐CM codes 759.81, 536.2, 346.2 and 306.4). After that, 37 365 patients remained, who were divided into participant groups with or without ED diagnoses (ICD‐9‐CM codes 307.1, 307.5, 307.51–4 and 307.59). ED was defined as an ED diagnosis made after depression diagnosis and three or more outpatient visits or at least one hospitalisation. Then, in order to eliminate potential effects due to baseline comorbidities between the two groups, we used 1:4 propensity score-matched controls from among the patients with depression who were randomly matched with the cases. Propensity score matching (Mahalanobis Metric Matching) was used to balance underlying demographics including sex, age, comorbidities and year of the depression index date, which might be unequally distributed between cases and controls at baseline (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selection of study subjects. ED, eating disorder; ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, NinthRevision, Clinical Modification; LHID, Longitudinal Health Insurance Database.

In this study, all sampled patients were tracked for a 1-year study period starting at the index date to evaluate their healthcare service utilisation and expenditures. The healthcare expenditure included ambulatory care costs by visit and inpatient costs by admission per person per year. As the NHIRD includes payment amounts, we treat the value of the costs as presented in US dollars at a fixed rate of 30 New Taiwan dollars (NT$) to US$1.0. Variables of healthcare resource utilisation in this study were defined as follows: (1) mean numbers of outpatient visits, (2) mean costs of outpatient services, (3) mean numbers of inpatient days and (4) mean costs of inpatient services during the 1 year follow-up period. Additionally, we divided healthcare resource utilisations into psychiatric services and non-psychiatric services.

Potential confounders

We defined baseline comorbidities, including major physical and mental disease, as potential confounders in this study because they are potentially associated factors for depression and ED. These included diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), hyperlipidaemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), cardiovascular disease (ICD-9-CM codes 390–398, 410–414 and 420–429), cerebral vascular accident (ICD-9-CM codes 430–438), anxiety disorder (ICD-9-CM code 300 except 300.4), bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 296.0, 296.1, 296.4, 296.5, 296.6, 296.7, 296.80, 296.81, 296.89 and 296.90), schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code 295), substance use disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 291, 292, 303, 304 and 305) and personality disorder (ICD-9-CM code 301).

Statistical analysis

A χ2 test and an independent t-test were used to compare the demographic characteristics among the groups. Means and SD and frequency (%) were used to report the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Due to the distributions of outcome variables (mean outpatient visits, costs, inpatient days and so on) being skewed, we thus used the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test to analyse the differences in variables of healthcare service utilisation between the two group. All analyses were carried out with SAS V.9.4. A two-sided p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or public were not involved in the research, including development of the research question, outcome measures, study design, recruitment and conduct of the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

The population-based study involved a total of 1270 participants. These included 254 depressed individuals with ED (depression+ED group) and 1016 depressed individuals without ED (depression group). The mean participant age was 29.3 years. About 94% of the patients were women, and 52.7% of the patients lived in urbanised areas. More than half (54%) had comorbid anxiety. Overall, the matched procedure was not significant between groups with regard to the distributions of age, sex, urbanisation level, income and comorbidities. The demographic characteristics are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Variable | Depression +ED group (N=254) |

Depression group (N=1016) |

P value | ||

| Total no. | Percent (%) | Total no. | Percent (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.616 | ||||

| Female | 239 | 94.1 | 964 | 94.9 | |

| Male | 15 | 5.9 | 52 | 5.1 | |

| Age, mean (SD) y† | 29.3±10.0 | 29.3±9.8 | 0.997 | ||

| Urbanisation level* | 0.986 | ||||

| 1 (most urbanised) | 74 | 29.1 | 287 | 28.3 | |

| 2 | 60 | 23.6 | 249 | 24.5 | |

| 3 | 41 | 16.1 | 175 | 17.2 | |

| 4 | 22 | 8.7 | 83 | 8.2 | |

| 5 (least urbanised) | 57 | 22.4 | 222 | 21.9 | |

| Monthly income | 0.996 | ||||

| US$0–600 | 96 | 37.8 | 386 | 38.0 | |

| US$601–1199 | 123 | 48.4 | 492 | 48.4 | |

| ≥US$1200 | 35 | 13.8 | 138 | 13.6 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 21 | 8.3 | 66 | 6.5 | 0.317 |

| Hypertension | 21 | 8.3 | 85 | 8.4 | 0.960 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 49 | 19.3 | 170 | 16.7 | 0.334 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 47 | 18.5 | 165 | 16.2 | 0.387 |

| Cerebral vascular accident | 10 | 3.9 | 38 | 3.7 | 0.883 |

| Bipolar disorder | 34 | 13.4 | 121 | 11.9 | 0.520 |

| Anxiety | 139 | 54.7 | 545 | 53.6 | 0.757 |

| Schizophrenia | 9 | 3.5 | 32 | 3.2 | 0.751 |

| Substance use disorders | 24 | 9.5 | 78 | 7.7 | 0.353 |

| Personality disorder | 19 | 7.5 | 79 | 7.8 | 0.875 |

χ2 test.

*Urbanisation level was categorised by the population density of the residential area into five levels, with level 1 as the most urbanised and level 5 as the least urbanised.

†t-test compared the demographic characteristics among groups.

ED, eating disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Healthcare utilisation and costs

Table 2 shows healthcare service utilisation in the 1-year period following the index date of depressed patients with and without ED. The depression+ED group had significantly more outpatient visits (32.2 vs 28.9, p=0.023), outpatient costs (US$1089 vs US$877, p<0.001) and total costs (US$1356 vs US$1296, p<0.001) than the depression group. However, healthcare utilisation did not significantly differ in terms of inpatient days (1.6 vs 4.4, p=0.301) and costs (US$267 vs US$418, p=0.214) between the two groups. This indicates that total costs were about one-fold greater for depression patients with ED than those without ED.

Table 2.

Healthcare utilisation and costs of the study population

| Variable | Depression+ED group (N=254) |

Depression group (N=1016) |

P value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| All health services | |||||

| Outpatient visits (n) | 32.3 | 22.8 | 28.9 | 20.1 | 0.023 |

| Outpatient costs (US$)* | 1089 | 1516 | 877 | 1300 | <0.001 |

| Inpatient days (n) | 1.6 | 6.4 | 4.4 | 49.4 | 0.301 |

| Inpatient costs (US$)* | 267 | 1040 | 418 | 3946 | 0.214 |

| Total costs (US$)* | 1356 | 1915 | 1296 | 4339 | <0.001 |

*US$ (1.0 US dollar=30 New Taiwan dollars).

ED, eating disorder; SD, standard deviation.

We categorised patients into two levels of depression severity according to the median number of depression outpatient visits (median depression outpatient visits=11), as shown in the online supplementary table 1. Severe depression with patients with ED had significantly higher outpatient costs (US$1291 vs US$1153, p=0.021) and total costs (US$1552 vs US$1,488, p=0.018) than patients with only severe depression. Similarly, we categorised depression patients according to the severity of ED, as shown in the online supplementary table 2. The results indicate that patients with severe ED had significantly more outpatient visits, greater outpatient costs and total costs than mild or no ED with depression patients. We considered all costs to be adjusted for inflation, as shown in the online supplementary table 3. In addition, we used the bootstrapping method to compare the mean cost differences between the two groups, as shown in the online supplementary table 4.

bmjopen-2019-032108supp001.pdf (101.2KB, pdf)

Psychiatric and non-psychiatric service utilisation

We further analysed the service utilisation of medical resources in psychiatry and non-psychiatry departments, as shown in table 3. Regarding psychiatric medical resource utilisation analysis, we found that the depression+ED group had significantly more outpatient visits (11.0 vs 6.8, p<0.001), outpatient care costs (US$584 vs US$320, p<0.001) and overall total costs (US$657 vs US$568, p<0.001) than the depression group. However, the depression+ED group had fewer hospital stays (0.8 vs 3.4, p=0.711) and lower hospitalisation costs (US$73 vs US$249, p=0.565) than the depression group, though the difference was not significant. We also found that psychiatric total costs were about 1.2 times greater for depression patients with ED than those without ED.

Table 3.

Psychiatric and non-psychiatric service utilisation of the study population

| Variable | Depression+ED group (N=254) |

Depression group (N=1016) |

P value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Psychiatry services | |||||

| Outpatient visits (n) | 11.0 | 11.7 | 6.8 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

| Outpatient costs (US$)* | 584 | 1293 | 320 | 458 | <0.001 |

| Inpatient days | 0.8 | 5.2 | 3.4 | 48.5 | 0.711 |

| Inpatient costs (US$)* | 73 | 456 | 249 | 3772 | 0.565 |

| Total costs (US$)* | 657 | 1369 | 568 | 3829 | <0.001 |

| Non-psychiatry services | |||||

| Outpatient visits (n) | 21.3 | 17.7 | 22.1 | 18.7 | 0.660 |

| Outpatient costs (US$)* | 505 | 491 | 558 | 1217 | 0.555 |

| Inpatient days | 0.7 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 9.1 | 0.138 |

| Inpatient costs (US$)* | 194 | 918 | 170 | 1169 | 0.073 |

| Total costs (US$)* | 699 | 1207 | 727 | 2080 | 0.488 |

*US$ (1.00 US dollar=30 New Taiwan dollars).

ED, eating disorder; SD, standard deviation.

In the non-psychiatric medical resource utilisation analysis, we found that there were no significant differences in outpatient or hospitalisation visits, outpatient or hospitalisation care costs, or overall total costs between the two groups. However, the depression+ED group visited non-psychiatric clinics more often than psychiatric clinics (21.3 vs 11.0), even though the expense of a non-psychiatric outpatient clinic was lower than a psychiatric clinic (US$505 vs US$584). On the other hand, the cost of hospitalisation in a non-psychiatric ward (US$194 vs US$73) was higher than that of psychiatric admission among the depression+ED group, though there was no difference in the days of admission between non-psychiatric and psychiatric hospitalisation (0.7 vs 0.8). Additionally, we found that both groups had more total costs for non-psychiatric care than psychiatric care (depression+ED group: US$699 vs US$657; depression group: US$727 vs US$568). Therefore, this highlights that the utilisation of outpatient services is noteworthy.

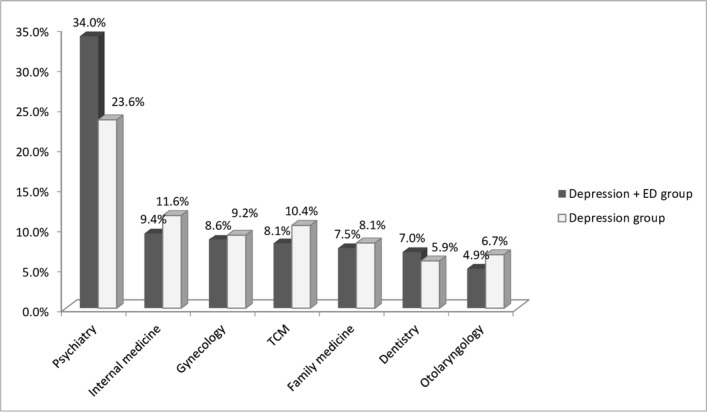

In both groups, further analysis found that the subjects most often visited the psychiatric department (34% vs 23.6%), followed by internal medicine (9.4% vs 11.6%), obstetrics and gynaecology (8.6% vs 9.2%), traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (8.1% vs 10.4%), family medicine (7.5% vs 8.1%), dentistry (7% vs 5.9%) and otolaryngology (4.9% vs 6.7%), as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Visit division of the study population. ED, eating disorder; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to analyse the healthcare utilisation of depressed patients with and without ED using a health insurance database. We report several notable findings. First, the depressed patients with ED utilised healthcare more in terms of outpatient visits, outpatient costs and 1.0-fold higher total costs than patients without ED, though their inpatient days and costs were lower. These findings corroborate previous reports that patients with both ED and depression used more outpatient than inpatient treatment, regardless of gender or type of ED.28 It has also been found that these results are similar to previous findings on healthcare utilisation of patients with ED.25 27 28 For instance, one study examined a large healthcare organisation in the USA and demonstrated that psychiatric comorbidity and healthcare service use were significantly elevated among women both before and after ED diagnosis.27 It was found that female patients with anorexia nervosa had more outpatient visits and outpatient expenditures than the controls.31 Additionally, the emotional symptoms associated with depressive disorders might lead to increased use of general medical services or emergency departments.32 On the other hand, somatic symptoms such as pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep, gastrointestinal disturbances and unexplained somatic symptoms have been reported as leading causes of outpatient visits for patients with depression.33 34 Considering the development of the combination of ED and depressive symptoms, a number of theoretical models have suggested frameworks that propose shared and specific risk factors, including biological/genetic,35 cognitive,36 emotional regulation37 and feminist models.38 Therefore, it is not surprising that depressed patients with ED had greater healthcare utilisation of outpatient services than those without ED. Another possible explanation is that most patients in our study were urban residents, which improves the convenience of general medical treatment. In our study found that those patients are associated with markedly higher healthcare utilisation, even after controlling for other psychiatric and physical comorbidities.

Second, the present study findings indicated that depressed patients with ED used psychiatric outpatient services more often than those without ED. Notably, they also made more non-psychiatric outpatient visits than psychiatric visits. Earlier studies indicated that during the 5 years preceding ED diagnosis, these patients consulted general medical doctors significantly more frequently than those without ED.26 Previous literature showed that patients with ED visited general medical doctors for emotional problems and/or for weight loss, and fewer patients sought treatment specifically for ED by a psychiatrist.19 39 Van Son et al indicated that patients with BN tended to seek general medical help for somatic problems rather than for mental health issues, whereas patients with AN are thought to be prone to somatic complications due to malnourishment.40 We speculate that these patients might feel ashamed to seek help for eating problems41 or that physicians fail to assess for42 or recognise ED symptoms.43 Another possibility is that they did not feel that the somatic problems were related to the ED by themselves. The present study confirmed that patients with ED often seek help from medical departments other than psychiatry. This perhaps reflects that early ED symptoms are not easily detected and are undertreated, leading to underestimating the incidence of ED.

Third, the results suggest that patients with depression and ED prefer to seek treatment across different departments. Our analysis further showed that in addition to seeking psychiatric help, they also frequently visited internal medicine, gynaecology, TCM and family medicine departments. Early studies found that most individuals with depression typically presented with psychological, gastrointestinal or gynaecological complaints, which might be prompted by symptoms of an ED.26 44 Patients with ED frequently have gastric emptying abnormalities, which cause bloating, postprandial fullness and vomiting.45 The gynaecological complaints were mostly of amenorrhoea or irregular periods.46 Therefore, we believed that these features might be potential risk factors for increased healthcare utilisation among depressed patients with ED. It is suggested that clinicians pay attention to possible signs and symptoms of ED in patients with depression. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that TCM has been used to treat depression-like symptoms.47–49 In Taiwan, younger people with depression were more likely to use TCM than older populations.48 Some studies have shown that depressed patients may use TCM mainly for treating sleep problems,50 respiratory conditions51 or painful physical symptoms.52 Therefore, the utilisation of TCM services could have a substantial impact on the healthcare costs of patients with depression.

An advantage of the present study is the use of data from a single-payer national health insurance programme, as well as a population-based dataset with extensive health welfare coverage. The database includes the complete utilisation of information and medical costs for almost all people in Taiwan. Thus, this study completely avoids the potential risk of recall bias. Nevertheless, there are several limitations to this study. First, we did not classify the subtypes of depression or an ED, duration of illness, date of onset of depression, family history of depression or comorbidity of depression, such as alcohol or substance use. The lack of a classification of the subtypes of depression or ED may limit the generalisation of our findings. In addition, the comorbidity of physical or psychiatric disorders might confound the relationship between disease and health utilisation. Second, there were no laboratory data included in this analysis. Thus, there may be missing information on the physical conditions related to ED, such as electrolyte imbalance, endocrine abnormality, and liver or renal abnormality, which may complicate the treatment course of patients and interfere with our analysis of health utilisation. Third, we did not include the evaluation of impaired functions, which may be associated with indirect costs of illness. Other than health utilisation, the indirect costs may reflect the functionally impaired rather than the severity of the physical or psychiatric symptoms of the disease itself. It usually remained subtle, but significantly reduced the welfare of not only the patients but even their family and coworkers. Fourth, because the dataset lacked records of out-of-pocket expenses, this study might underestimate hospital treatment costs. Finally, we could not further analyse the healthcare utilisation of ED subtypes. Future research is warranted to investigate the impact of societal burdens among these patients, especially in terms of their lost productivity due to the inability to work or premature death.

Conclusions

Depressed patients with ED showed higher healthcare utilisation than those without ED, especially outpatient visits, outpatient costs and total costs. Additionally, these patients often visited psychiatric clinics, followed by internal medicine, gynaecology, TCM and family medicine. Clinicians should pay attention to possible signs and symptoms of ED in patients with depression, and early appropriate treatment for ED should be considered. Nevertheless, a future study may further explore the factors potentially leading to increased healthcare expenditures by depressed patients with ED.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks for grants MOST105-2314-B-016-016-MY3, TSGH-C108-160, TSGH-C108-149. The authors thank all the research associates for their contributions to this work and feedback. The database used in this study derives from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Our explanations and conclusions do not represent the views of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan.

Footnotes

Contributors: CLY: study methodology, literature review, data analysis, and manuscript writing. LTK: data collection, statistical analysis, and interpretation of the results. MKY: manuscript revision and administrative support. WCC: study methodology and administrative support. CBY: planning of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was exempt from full review by the Tri-Service General Hospital Institutional Review Board (TSGHIRB No. 1-104-05-048). Our study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The informed consent of patients was not required for this study, as they were not asked to follow rules of behavior. All personal patient data were coded and patient anonymity was guaranteed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. . Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:724–31. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Field AE, Sonneville KR, Micali N, et al. . Prospective association of common eating disorders and adverse outcomes. Pediatrics 2012;130:e289–95. 10.1542/peds.2011-3663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bühren K, Schwarte R, Fluck F, et al. . Comorbid psychiatric disorders in female adolescents with first-onset anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disorders Rev 2014;22:39–44. 10.1002/erv.2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braun DL, Sunday SR, Halmi KA. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with eating disorders. Psychol Med 1994;24:859–67. 10.1017/S0033291700028956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yan C-L, Chang J-C, Weng S-C, et al. . The pre-existing depressive disorders, substance use disorders predicted the suicidal death of the patients with eating disorders – a preliminary result of national health insurance research databases in a Chinese population. Neuropsychiatry 2018;08:1622–9. 10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gadalla T, Piran N. Psychiatric comorbidity in women with disordered eating behavior: a national study. Women Health 2008;48:467–84. 10.1080/03630240802575104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu C-Y, Tseng M-CM, Chang C-H, et al. . Comorbid psychiatric diagnosis and psychological correlates of eating disorders in dance students. J Formos Med Assoc 2016;115:113–20. 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salbach-Andrae H, Lenz K, Simmendinger N, et al. . Psychiatric comorbidities among female adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2008;39:261–72. 10.1007/s10578-007-0086-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown P. Effective treatments for mental illness not being used, who says. BMJ 2001;323:769 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sobocki P, Ekman M, Ågren H, et al. . Resource use and costs associated with patients treated for depression in primary care. Eur J Health Econ 2007;8:67–76. 10.1007/s10198-006-0008-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sobocki P, Lekander I, Borgström F, et al. . The economic burden of depression in Sweden from 1997 to 2005. Eur Psychiatry 2007;22:146–52. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomas CM, Morris S. Cost of depression among adults in England in 2000. Br J Psychiatry 2003;183:514–9. 10.1192/00-000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coentre R, Talina MC, Góis C, et al. . Depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior after first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2017;253:240–8. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. . Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:352–7. 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chan ALF, Yang TC, Chen J-X, et al. . Cost of depression of adults in Taiwan. Int J Psychiatry Med 2006;36:131–5. 10.2190/6KN8-F4LV-7YV9-FM8G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chien I-C, Bih S-H, Chou Y-J, et al. . Trends in the use of psychotropic drugs in Taiwan: a population-based National health insurance study, 1997–2004. PS 2007;58:554–7. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herzog DB, Keller MB, Sacks NR, et al. . Psychiatric comorbidity in treatment-seeking anorexics and bulimics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31:810–8. 10.1097/00004583-199209000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silberg JL, Bulik CM. The developmental association between eating disorders symptoms and symptoms of depression and anxiety in juvenile twin girls. J Child Psychol & Psychiat 2005;46:1317–26. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, et al. . The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007;61:348–58. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Franko DL, Keel PK. Suicidality in eating disorders: occurrence, correlates, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:769–82. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deep AL, Nagy LM, Weltzin TE, et al. . Premorbid onset of psychopathology in long-term recovered anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1995;17:291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ivarsson T, Råstam M, Wentz E, et al. . Depressive disorders in teenage-onset anorexia nervosa: a controlled longitudinal, partly community-based study. Compr Psychiatry 2000;41:398–403. 10.1053/comp.2000.9001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perez M, Joiner TE, Lewinsohn PM. Is major depressive disorder or dysthymia more strongly associated with Bulimia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord 2004;36:55–61. 10.1002/eat.20020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stice E, Hayward C, Cameron RP, et al. . Body-Image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol 2000;109:438–44. 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mitchell JE, Myers T, Crosby R, et al. . Health care utilization in patients with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2009;42:571–4. 10.1002/eat.20651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogg EC, Millar HR, Pusztai EE, et al. . General practice consultation patterns preceding diagnosis of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1997;22:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Striegel-Moore RH, DeBar L, Wilson GT, et al. . Health services use in eating disorders. Psychol Med 2008;38:1465–74. 10.1017/S0033291707001833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Striegel-Moore RH, Leslie D, Petrill SA, et al. . One-Year use and cost of inpatient and outpatient services among female and male patients with an eating disorder: evidence from a national database of health insurance claims. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000;27:381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Watson HJ, Jangmo A, Smith T, et al. . A register-based case-control study of health care utilization and costs in binge-eating disorder. J Psychosom Res 2018;108:47–53. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simon J, Schmidt U, Pilling S. The health service use and cost of eating disorders. Psychol Med 2005;35:1543–51. 10.1017/S0033291705004708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hung Y-N, Kuo C-J, Yang S-Y, et al. . Patterns of medical utilization before the first hospitalization for women with anorexia nervosa in Taiwan. J Psychosom Res 2017;102:1–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992;267:1478–83. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480110054033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kapfhammer H-P. Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2006;8:227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric co-morbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2003;12:34–43. 10.1002/mpr.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaye W. Neurobiology of anorexia and Bulimia nervosa. Physiol Behav 2008;94:121–35. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cooper MJ. Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and Bulimia nervosa: progress, development and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev 2005;25:511–31. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:217–37. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tiggemann M, Kuring JK. The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. Br J Clin Psychol 2004;43:299–311. 10.1348/0144665031752925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, et al. . Health service utilization for eating disorders: findings from a community-based study. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:399–408. 10.1002/eat.20382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Son GE, Hoek HW, Van Hoeken D, et al. . Eating disorders in the general practice: a case-control study on the utilization of primary care. Eur Eat Disorders Rev 2012;20:410–3. 10.1002/erv.2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hepworth N, Paxton SJ. Pathways to help-seeking in Bulimia nervosa and binge eating problems: a concept mapping approach. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:493–504. 10.1002/eat.20402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Levine AS, et al. . A survey of binge eating and obesity treatment practices among primary care providers. Int J Eat Disord 2004;35:348–53. 10.1002/eat.10266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with Bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med 2001;31:1455–66. 10.1017/S0033291701004640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kimmel MC, Ferguson EH, Zerwas S, et al. . Obstetric and gynecologic problems associated with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2016;49:260–75. 10.1002/eat.22483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McClain CJ, Humphries LL, Hill KK, et al. . Gastrointestinal and nutritional aspects of eating disorders. J Am Coll Nutr 1993;12:466–74. 10.1080/07315724.1993.10718337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stewart DE, Erlick Robinson G, Goldbloom DS, et al. . Infertility and eating disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1196–9. 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90688-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu H, He Y, Wang J, et al. . Epidemiology of depression at traditional Chinese medicine hospital in Shanghai, China. Compr Psychiatry 2016;65:1–8. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pan Y-J, Cheng I-C, Yeh L-L, et al. . Utilization of traditional Chinese medicine in patients treated for depression: a population-based study in Taiwan. Complement Ther Med 2013;21:215–23. 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhou L, Chen W-kai, Mei X-yun. [Study on the characteristics of population distribution of TCM syndromes and its related factors in patients of depression]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2006;26:106–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. PL Y, Tsai CH, Chen YC, et al. . Gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor mediates suanzaorentang, a traditional Chinese herb remedy, -induced sleep alteration. J Biomed Sci 2007;14:285–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jiang L, Li K, Wu T, et al. . Chinese medicinal herbs for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD004560 10.1002/14651858.CD004560.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Madsen MV, Gotzsche PC, Hrobjartsson A. Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and NO acupuncture groups. BMJ 2009;338:a3115 10.1136/bmj.a3115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032108supp001.pdf (101.2KB, pdf)