Abstract

Objectives

To (1) provide an up-to-date overview of shared decision making (SDM)-models, (2) give insight in the prominence of components present in SDM-models, (3) describe who is identified as responsible within the components (patient, healthcare professional, both, none), (4) show the occurrence of SDM-components over time, and (5) present an SDM-map to identify SDM-components seen as key, per healthcare setting.

Design

Systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed articles in English presenting a new or adapted model of SDM.

Information sources

Academic Search Premier, Cochrane, Embase, Emcare, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science were systematically searched for articles published up to and including September 2, 2019.

Results

Forty articles were included, each describing a unique SDM-model. Twelve models were generic, the others were specific to a healthcare setting. Fourteen were based on empirical data, 26 primarily on analytical thinking. Fifty-three different elements were identified and clustered into 24 components. Overall, Describe treatment options was the most prominent component across models. Components present in >50% of models were: Make the decision (75%), Patient preferences (65%), Tailor information (65%), Deliberate (58%), Create choice awareness (55%), and Learn about the patient (53%). In the majority of the models (27/40), both healthcare professional and patient were identified as actors. Over time, Describe treatment options and Make the decision are the two components which are present in most models in any time period. Create choice awareness stood out for being present in a markedly larger proportion of models over time.

Conclusions

This review provides an up-to-date overview of SDM-models, showing that SDM-models quite consistently share some components but that a unified view on what SDM is, is still lacking. Clarity about what SDM constitutes is essential though for implementation, assessment, and research purposes. A map is offered to identify SDM-components seen as key.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration CRD42015019740

Keywords: shared decision making, model, definition, concept, patient, healthcare professional, time trends, decision process

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Seven major databases were systematically searched

Selection of all articles and extraction of all the data was done in duplicate and in consensus

Articles that did not provide evidence of presenting a shared decision making (SDM)-model in the title or abstract may have falsely been excluded

It was sometimes difficult to distinguish what authors of SDM-models saw as contextual vs integral to the SDM-process

Extraction of the SDM-models therefore may have been too inclusive or too strict

Introduction

Shared decision making (SDM) between patients and healthcare professionals is gradually becoming the norm across Western societies as the model for making patient-centred healthcare decisions1 2 and achieving value-based care.3 4 SDM is based on the thought that healthcare professionals are the experts on the medical evidence and patients are the experts on what matters most to them.3 Systematic reviews of published SDM-models date back to 2006 and 2007.5 6 Makoul and Clayman concluded that there is no unified SDM-model, and proposed a set of essential elements to form an integrative model of SDM (eg, Define and/or explain the problem, Discuss pros/cons, Patient values/preferences, Make or explicitly defer decision).5 From their perspective, elements can be initiated either by patients or healthcare professionals, and they purposively abstained from identifying actors in their model so as not to place sole responsibility on either. Soon after, a second systematic review concluded that the focus of SDM-models is placed on information exchange and on the involvement of both patient and healthcare professional in making the decision.6 Since then, SDM has gained attention exponentially, with new SDM-models emerging, and with what SDM specifically entails remaining under debate.3 7 8 Moreover, in a systematic review of measures to assess SDM we noted that developers of SDM measures often only vaguely define the SDM construct or do not define it at all.9 Meanwhile, there are calls to extend the conceptualization of SDM, such as by focusing on the person facing the decision rather than on a consultation,10 or by shifting the focus of SDM to relationship-centred care11 or to humanistic communication.12

Clarity about what SDM constitutes in a specific situation is essential for training, implementation, policy, and research purposes. This systematic review aims to (1) provide an up-to-date overview of SDM-models, (2) give insight in the prominence of components present in SDM-models, (3) describe who is identified as responsible within the components (ie, patient, healthcare professional, both or none), (4) show the occurrence of SDM-components over time, and (5) present an SDM-map to identify SDM-components seen as key, per healthcare setting.

Methods

In the following we use the term model for both models and definitions, for sake of readability. These terms may have a slightly different meaning but are often used interchangeably. No ethical approval was required. We registered this systematic review at PROSPERO: CRD42015019740.

Search strategy

Seven electronic databases (Academic Search Premier, Cochrane, Embase, Emcare, PsycINFO PubMed, and Web of Science) were systematically searched for articles published from inception up to and including September 2, 2019. The search terms “shared decision” and related terms such as “shared medical decision”, “shared treatment decision” and “shared clinical decision”, and their plural forms, as well as the broadly used abbreviation SDM were used to search in title and keywords. The search was restricted to peer-reviewed scientific articles; to publications in English for pragmatic reasons; and to publications about humans. See online supplementy appendix A for our complete search strategy.

bmjopen-2019-031763supp001.pdf (58.7KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

During the screening of titles and abstracts we determined whether the term model or definition was used, and if not, whether it could be expected that the authors would provide a new or adapted SDM-model. Full-text articles were excluded if they were not externally peer-reviewed or not written in English. Full-text articles were included if the authors explicitly described a new model of the SDM-process between a patient and one or more healthcare professionals, or if the authors had adapted an existing model based on own insights or research outcomes, and if the model was described comprehensibly, that is, in enough detail to explain the process. We therefore excluded articles in which the authors only referred to a model described elsewhere, only mentioned the concept of SDM, or explained it briefly only. Also, the focus was on models that assumed a competent patient, that is, a patient that was able to participate in the decision making process.

Selection process

Three researchers (AP, HB-R, FG) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of the first 100 records and discussed inconsistencies until consensus was obtained. Then, in pairs, the researchers independently screened titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved. In case of disagreement, consensus on which articles to screen full-text was reached by discussion. If necessary, the third researcher was consulted to make the final decision. Next, two researchers (AP, HB-R) independently screened full-text articles for inclusion. Again, in case of disagreement, consensus was reached on inclusion or exclusion by discussion and if necessary, the third researcher (FG) was consulted.

Data extraction

We extracted the description of each SDM-model (ie, the verbatim text describing the model) as well as the following general characteristics: first author, year of publication, healthcare setting, and development process (ie, informed by existing literature or by data collected with the purpose to inform the model; for the latter, we extracted methods and respondents). Using a standardised extraction form, one researcher (AP or HB-R) extracted the data, the other researcher verified it, and inconsistencies were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data analysis

We separated each SDM-model description into text fragments, that is, the smallest piece of text conveying a single constituent of the model, often delineated by conjunctions or punctuation. We then first classified all text fragments using elements, starting out with the list of 32 elements that Makoul and Clayman reported.5 We refined or split elements, or added new elements if necessary. Elements may describe specific behaviours (eg, List options) but need not (eg, Patient values). Second, we determined the actor for each classified text fragment. An actor was defined as the person identified to be responsible for the occurrence of the behaviour or result described in the text fragment (ie, no actor identified, patient and healthcare professional, only patient, or only healthcare professional). To illustrate, for Patient values it may be stated in the text fragment that healthcare professionals need to ask about patients’ values, or that patients need to express their values. In the first case, the actor would be the healthcare professional; in the second, the patient. Note that the actor identified for the same element that is present in different SDM-models may differ between models, depending on the actor identified by the authors of the respective models. Third, we clustered elements representing a shared theme into overarching components taking into account the underlying text fragments, and formulated a name for each component, for example, Provide neutral information, or Advocate patient views. Clustering of elements into components was based on the content of the elements and regardless of actor. For the ensuing components, we now again determined the actor(s), based on the actors identified for the constituting elements. For each analysis step, one researcher (HB-R or AP) performed the analysis, the other verified it, and inconsistencies were discussed until consensus was reached. To depict a possible trend in the occurrence of components in SDM-models over time, we grouped the SDM-models by publication date into four different time periods (ie, until 2010, 2010–2014, 2015–2017, since 2018), each containing approximately the same number of models. We calculated in how many of the models during a particular time period each component was present, as a percentage.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document.

Results

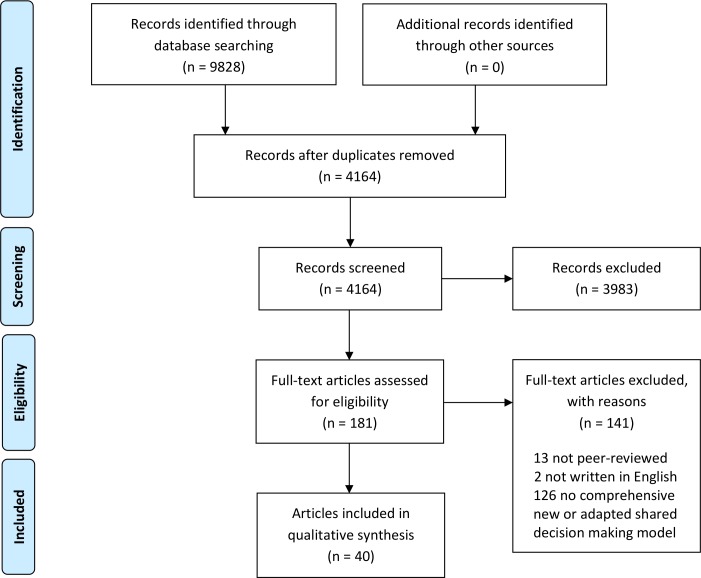

The search yielded 4164 unique records. Forty articles were included in this review, from 34 different first authors, each describing a unique model (figure 1). The articles were published from 1997 up to and including September 2, 2019. See online supplementy appendix B for the model descriptions.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection process.

bmjopen-2019-031763supp002.pdf (198.6KB, pdf)

General characteristics of the models

Healthcare settings

Twelve SDM-models were generic (ie, specified as such or no healthcare setting specified).5 13–23 The other 28 SDM-models had been developed for a particular healthcare setting or patient group, namely primary care,24–29 screening,30 31 the inpatient setting,32 paediatrics,33–35 mental healthcare,36–38 emergency care,39 40 oncology care,41 42 chronic care,43 44 nursing care,45 physical therapy,46 older patients,47 48 serious illness,49 50 or diabetes.51

Decision types

Thirteen models were focused more or less explicitly on treatment decision making,14 17 28 34 36 38 41–43 46 48 49 51 two on screening,30 31 one on test and treatment decision making,50 one on disease prioritisation and treatment,44 one on goals and actions,27 and one on decisions regarding diagnostic testing, treatment, or follow-up.19 For the other 21 models, the authors did not explicitly state the type of decision.5 13 15 16 18 20–26 29 32 33 35 37 39 40 45 47

Development processes

All authors referred to the broader SDM literature including SDM-models, although existing SDM-models may not have explicitly formed the origin of their own model. Twenty-one SDM-models were explicitly based on one or more of the SDM-models included in this review.5 15 17 18 20 22 23 25–29 31 32 38 39 43 45–47 51 Online supplementy appendix B shows that especially the models of Charles,17 49 Towle,16 Elwyn,14 29 and Makoul5 informed other SDM-models. Two-thirds of the models (26/40) were further or solely based on analytical thinking of the authors (ie, no data were collected in patients and/or healthcare professionals with the purpose to inform the model); of note, empirical data collected for other purposes may have informed these models.5 14 15 17 19 21 22 24 28 30–35 38–41 43–46 48–50 The development of the other models (14/40) was informed by empirical data gathered with the purpose to inform the model.13 16 18 20 23 25–27 29 36 37 42 47 51 These empirical data were collected in individual and/or focus group interviews with patients (4/14),13 36 37 51 healthcare professionals (1/14),29 patients and healthcare professionals (1/14),16 patients, members of the general population, healthcare professionals, and researchers (1/14),42 or in patient representatives, healthcare professionals, managers, and others from unnamed professions (1/14).26 Between four and 54 patients and between six and 49 healthcare professionals participated in the individual or focus group interviews (not all patient numbers reported for one qualitative study). Further, data were collected in a Delphi study with patients, healthcare professionals and academics (1/14),47 in research work groups with patients and healthcare professionals (1/14),18 in a consensus study involving healthcare professionals, an anthropologist and a community health specialist (1/14),25 and in a three-round consultation of academics, patients and healthcare professionals (1/14).20 Finally, 76 consultations (one consultation of 26 pre-dialysis patients and two consultations of 25 breast cancer patients) were audiotaped and analysed (1/14),23 and eight consultations were audiotaped and analysed, and patients, healthcare professionals and experts were interviewed (1/14).27

Components within the models

We identified 53 different elements in the descriptions of the SDM-models and clustered these in 24 overarching components (table 1). Figure 2 visualises the components; the surface of a particular circle indicates in how many of the 40 SDM-models the component was mentioned. Describe treatment options was the component most frequently present in any of the SDM-models; it was included in 35/40 models (88%). Other components present in more than half of the models were: Make the decision (75%), Patient preferences (68%), Tailor information (65%), Deliberate (58%), Create choice awareness (55%), and Learn about the patient (55%). The component Reach mutual agreement was present in 35% of the models. For a majority (9/14, 64%) of these models the patient and the healthcare professional had to agree on the final decision, but not in all. Components identified in 10% of the models at most were: Healthcare professional expertise (10%) and Patient expertise (8%).

Table 1.

Components, their constituting elements, and how often they are part of the 40 shared decision making models.

| Components | Elements | Frequency |

| Advocate patient views |

Patient advocacy | 12 (30%) |

| Patient opinion is important | ||

| Create choice awareness |

Equipoise | 22 (55%) |

| Make need for decision explicit | ||

| Deliberate |

Deliberation* | 23 (58%) |

| Negotiation* | ||

| Describe treatment options |

Benefits/risks (pros/cons)† | 35 (88%) |

| Feasibility of option(s) | ||

| List options‡ | ||

| Present evidence† | ||

| Determine roles in decision making process |

All parties have a legitimate interest in the decision† | 14 (35%) |

| Formulation of equality of partners | ||

| Involves at least two people† | ||

| Patient's decisional role preference‡ | ||

| Process determination or evaluation | ||

| Determine next step |

Arrange follow-up† | 19 (48%) |

| Implementation | ||

| Foster partnership |

Mutual respect† | 12 (30%) |

| Partnership† | ||

| Gather support and information |

Patient accesses information | 8 (20%) |

| Support with decision | ||

| Healthcare professional expertise | Doctor knowledge* | 4 (10%) |

| Healthcare professional preferences |

Healthcare professional preferences | 7 (18%) |

| Healthcare professional values | ||

| Learn about the patient |

Check/clarify understanding healthcare professional‡ | 21 (53%) |

| Learn about the patient | ||

| Make the decision |

Document (discussion about) decision | 30 (75%) |

| Make or explicitly defer decision† | ||

| Patient retains ultimate authority over decision | ||

| Revisiting decision | ||

| Offer time | Offer time | 8 (20%) |

| Patient expertise | Patient expertise | 3 (8%) |

| Patient preferences |

Patient concerns | 26 (65%) |

| Patient goals of care | ||

| Patient preferences* | ||

| Patient values* | ||

| Patient questions | Patient questions | 8 (20%) |

| Prepare | Prepare (prior to consultation) | 6 (15%) |

| Provide information |

Information exchange† | 17 (43%) |

| Medical information | ||

| Patient information | ||

| Provide neutral information | Unbiased information† | 8 (20%) |

| Provide recommendation | Doctor recommendation* | 10 (25%) |

| Reach mutual agreement | Mutual agreement† | 14 (35%) |

| Set agenda |

Decide on agenda for the consultation | 9 (23%) |

| Define/explain problem† | ||

| Support decision making process |

Assess what patient needs to make decision | 11 (28%) |

| Doctor guidance in decision making process | ||

| Identify and address emotions | ||

| Tailor information |

Ascertain preferred (format for) information† | 26 (65%) |

| Check/clarify understanding patient‡ | ||

| Flexibility/individualised approach† | ||

| Use clear language |

Figure 2.

Components of shared decision making models, and actors identified within components.

Actors

Within models

Thirty-seven of the 40 models identified one or more actors, in two models actors were not mentioned at all,15 20 and the authors of one model stated that they purposively did not define actors.5 In 21/37 models both patient and healthcare professional were identified as actors;13 16–19 22 27 28 31 34 36 42–51 in four of these, patients’ role was implicit,27 31 34 47 and in one both patients’ and healthcare professionals’ role were implicit.22 Three models identified the patient and several healthcare professionals as actors,25 26 30 three models identified the underaged patient, the parent, and the healthcare professional as actors.33 35 38 Ten models identified solely the healthcare professional as actor.14 21 23 24 29 32 37 39–41

Within components

The colour of the line around the components in figure 2 shows how often a particular actor or actors were mentioned for the elements constituting that component. The healthcare professional was often identified as the sole actor within components. In other cases, either the patient, both the patient and the healthcare professional, or no actor was identified for elements constituting a component. The following actor or actors were identified in more than half of the models in which these components were present: the healthcare professional in Support decision making process (92%), Advocate patient views (69%), Prepare (67%), Learn about the patient (64%), Describe treatment options (63%), Offer time (63%), Provide neutral information (63%), Provide recommendation (60%), Healthcare professional preferences (57%), Create choice awareness (55%), and Tailor information (54%); both healthcare professional and patient in Reach mutual agreement (57%); no actor in Healthcare professional expertise (100%), Patient expertise (67%), and Gather support and information (56%).

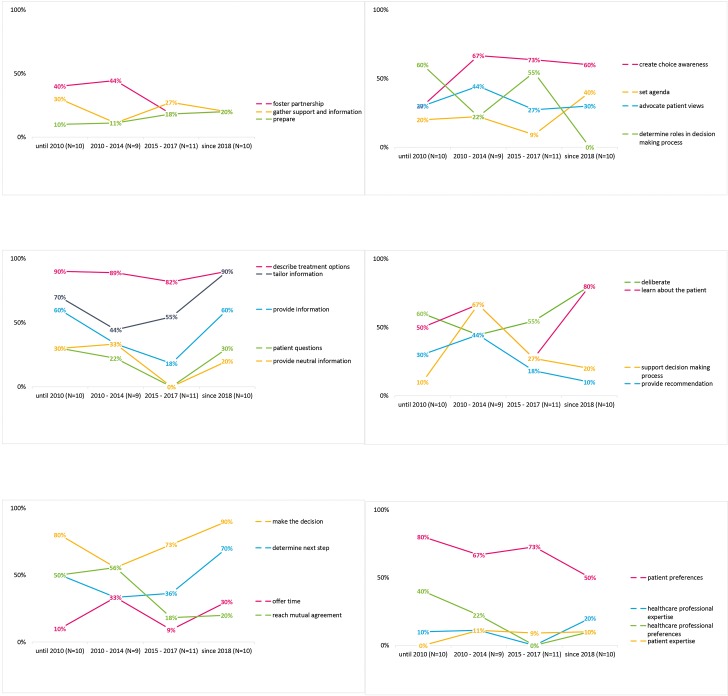

Time trends

Four models of SDM were published up to 2001.16 17 29 49 No new models were published between 2001 and 2006, and then another four models in 2006.5 15 28 43 From then on, numbers increased rapidly from 2015 onwards, and half of the models were published since then. Figure 3 shows how often components appeared in models by time period: until 2010 (n=10 models), 2010 until 2015 (n=9 models), 2015 until 2018 (n=11 models), 2018 up to and including September 2 2019 (n=10 models). There is some variation in which components were present in SDM-models over time. Describe treatment options and Make the decision were present in more than half of the SDM-models in any time period, while Patient expertise, Healthcare professional expertise, and Prepare were present in relatively few models only in any time period, although the latter shows a steady increase over time. Create choice awareness was present in markedly more models from 2010 onwards than before. The presence of several components in models showed a more or less marked decrease over time, including Healthcare professional preferences since 2010, Support decision making process, Provide recommendation, and Reach mutual agreement since 2015, and Determine roles in decision making process since 2018. The extent to which the other components were present in models fluctuates over time, without a clear pattern. The most prominent components in the most recent models in order of occurrence include Describe treatment options, Make the decision, Tailor information, Deliberate, Learn about the patient, and Determine next step.

Figure 3.

Appearance of components in shared decision making models over time.

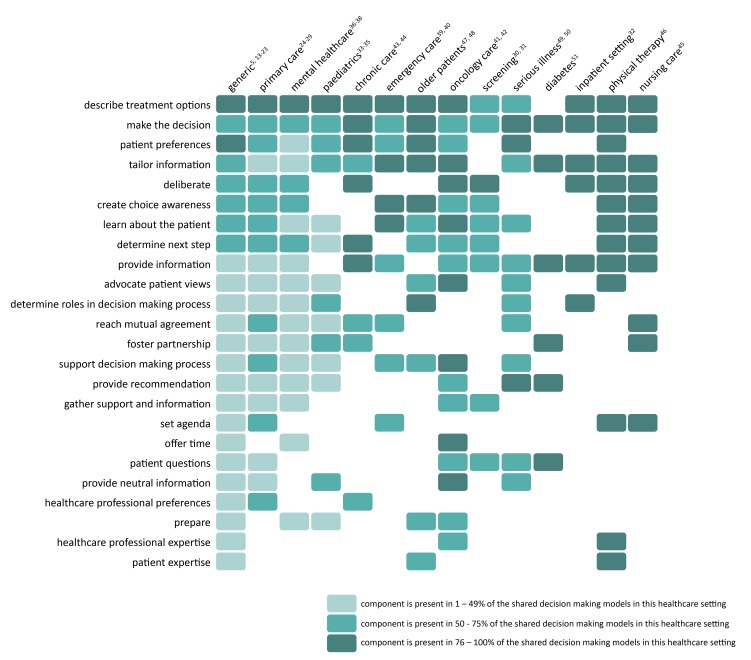

Shared decision making map

We present a map to depict which components seem most relevant to SDM, by healthcare setting (figure 4). On the Y-axis, the components are shown in order of frequency from top to bottom, across SDM-models. On the X-axis, the healthcare settings are shown in order of number of existing SDM-models from left to right. How often a particular component was present in SDM-models within a healthcare setting is colour-coded. The SDM-map thus helps identify (1) what components make up SDM-models, (2) how often components are present in SDM-models overall, (3) how often components are present in SDM-models within a particular healthcare setting. The SDM-map shows some components to be part of SDM-models in almost any healthcare setting (eg, Describe treatment options, Make the decision, Patient preferences), and how the inclusion of other components differs between settings (eg, Create choice awareness, Provide recommendation, Offer time). The SDM-map may help users to critically reflect on the rightful presence or absence of components in particular healthcare settings.

Figure 4.

Map of shared decision making components by healthcare setting and frequency of occurrence.

Discussion

Our review provides an inventory of the 40 SDM-models currently available. Many models defining SDM are of relatively recent date: half of the models included were published in 2015 or later. Similarities between models exist but significant heterogeneity still remains, as others have noted before.5 This may not be surprising considering the fact that almost half of the models have been developed for a variety of decisions relating to screening, diagnostic testing or treatment decisions, and that 28 of the non-generic models have been developed for 13 different healthcare settings.

Over a decade ago, Makoul and Clayman noted the low frequency with which authors defining SDM recognised and cited previous work in the field; they found one-third of articles with a conceptual model failed to cite any other model.5 Our review shows that authors at least referred to existing literature about SDM, also when they did not base their own model on an earlier SDM-model. Moreover, especially the relatively older models that Charles,17 49 Towle,16 Elwyn,14 29 and Makoul5 and their colleagues have developed have each informed at least six other SDM-models. These authors therefore have had a significant impact on thinking about what constitutes an SDM-process. They and others have further published adapted versions of their own models. Components specific to these models are therefore prominently present in our SDM-map. Further and remarkably, views of patients and/or healthcare professionals, the ones who enact SDM in clinical practice, were only assessed to inform fourteen of the 40 models. This may have resulted in underrepresentation of components that patients and healthcare professionals consider to be indispensable in current thinking about what constitutes SDM.

As may be expected, the component Describe treatment options was present in the vast majority of models. The transfer of information about treatment options is clearly key to SDM, and patients need this information to be able to participate in SDM. However, conveying treatment information to patients in itself does not safeguard that patients are actually able to participate.52 53 For the component Reach mutual agreement, two ways of framing appeared: mutual agreement about the final decision is a requisite in part of the models, while in others this requirement is not formulated explicitly, or specifically relates to the process required to reach a decision rather than to the final decision itself. It may be of minor importance who makes the final call or whether all parties involved fully agree that the option chosen is the best possible option for this patient in this situation, as long as the process is shared.42 Patient expertise and Healthcare professional expertise were rarely present in SDM-models. Since the first is often mentioned as the rationale for SDM,17 54 it may not be surprising that it is not part of the definition of SDM. The authors’ focus may be more on how to uncover this expertise (eg, Learn about the patient) when describing the SDM process than on the expertise itself.

Creating choice awareness clearly caught attention since 2010. Choice awareness has been defined as “acknowledging that the patient’s situation is mutable and that there is more than one sensible way to address or change this situation”,55 and been put forward as pivotal in achieving SDM for some time.2 However, despite the inclusion of this behaviour in models, it is seldom seen in clinical practice.55–57 Both Provide a recommendation and Healthcare professional preferences are less and less present in SDM-models, suggesting that authors ideally see that healthcare professionals’ preferences influence patients as little as possible. One may question if this is ideal from patients’ perspective, as patients may consider receiving a treatment recommendation part of SDM.13 42 58 Importantly, providing a recommendation that integrates informed patient preferences may indeed help patients in deciding what option they would prefer, and perfectly fits with SDM. Our results further show that the calls that were recently made to extend the conceptualization of SDM, such as by focusing on the person facing the decision rather than on a consultation,10 or by explicitly including time outside of consultations42 would indeed add new aspects to the conceptualizations of SDM so far. Offer time and Gather support and information for example, are part of relatively few models and typically convey attention to time outside of consultations and to the involvement of other stakeholders in the process, such as informal caregivers.18 42 Future SDM-models may use a triadic approach towards SDM, in which the role of the caregiver is made explicit.59

It is noteworthy that in one-fourth of the models overall, only the healthcare professional is identified as the actor in SDM, that is, is seen as responsible for the occurrence of an SDM-process. This does not align with the formal acknowledgement in 2011 of patients’ role in making SDM happen in the Salzburg statement on SDM.60 It bears the question whether it is justified to put the onus of achieving SDM on healthcare professionals only, and how patients can truly participate in an SDM-process if they are not recognised as active participants. It is especially important to acknowledge patients’ role in SDM-models since patients formulate their own responsibilities in SDM, in qualitative studies asking about SDM.13 18 42 Authors of SDM-models should therefore carefully consider patients’ role in SDM. Also, we recommend that authors who develop an SDM-model clarify each actor’s role. Doing so will help elucidate whose behaviour(s) should be targeted when aiming to improve SDM-levels, or measured when aiming to evaluate SDM-levels. This will facilitate the development of appropriate interventions and of valid measurement instruments. Also, authors of future SDM-models may want to involve patients and healthcare professionals in the development process of their models, to ensure that these reflect the views of those who enact SDM in practice.

This study provides a systematic overview of SDM-models published so far. A first potential limitation of the review is that we excluded articles based on title/abstract screening that did not provide evidence of presenting an SDM-model. We may therefore have missed models. Second, the first criterion in the assessment of full-text articles was if they had gone through external peer-review. This criterion was difficult to apply at times, as information was lacking in this respect. We therefore chose an inclusive strategy and may have included articles that have not gone through external peer-review. Third, for some models it was difficult to distinguish what the authors saw as context and what as integral to the SDM-process. Also, it was sometimes difficult to determine from the description what the authors considered to be essential to the SDM-process and what was for example, an example of possible behaviour in the context of SDM.

The existence of SDM-models that vary in emphasis does not seem problematic to us per se. What an SDM-process exactly entails may differ by healthcare setting, and it may thus be helpful to have different models and choose the one that fits one’s purposes best. Striving for one unified model may even be unrealistic and counterproductive. Also, existing models may be adapted or extended if this proves useful. However, striving for consensus on the core of what SDM is, is desirable to align research, training, and implementation efforts. The pursuit of consensus begs the question as to whom should ideally be involved in deciding on the essence of SDM. Until consensus is reached, we call authors to report the model they use, whichever it is. Being explicit about the SDM-model used is necessary to develop SDM measures, understand results on the occurrence of SDM and its effects, to develop and implement interventions, and for training and policy purposes. When developing an intervention, it is also important to report whether the intervention targets one or more components of the SDM-process. For healthcare professionals who aim to share decisions with their patients, it is good to realise that there is no consensus in the field, only that certain components seem more key to SDM than others. Our SDM-map is a practical visual tool to easily identify the components seen as most relevant when enacting SDM in clinical practice, what components may be of more or less relevance to a particular healthcare setting, and provides a basis for what should be included in training and decision support interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Schoones (Walaeus Library, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands) for his assistance in performing the search, Nanny van Duijn-Bakker (Department of Biomedical Data Sciences, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands) for her contribution to the retrieval of full text articles, Sascha Keij, MSc (Department of Biomedical Data Sciences, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands) for her contribution to the preparation of Figures 1 and 3, and Bertus Bomhof, MSc for his contribution to the design of Figures 2 and 4.

Footnotes

Twitter: @AMStiggelbout, @ArwenPieterse

Contributors: AP, AMS and HB-R designed the study. AP, FG and HB-R performed title and abstract screening. AP and HB-R performed full-text screening, conducted the data extraction, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in interpreting the results. All authors have read the manuscript, made improvements of the content and wording, and have agreed to the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society, grant number UL2013-6108. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Härter M, Moumjid N, Cornuz J, et al. Shared decision making in 2017: international accomplishments in policy, research and implementation. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2017;123-124:1–5. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stiggelbout AM, Weijden TVd, Wit MPTD, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ 2012;344:e256 10.1136/bmj.e256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spatz ES, Krumholz HM, Moulton BW. Prime time for shared decision making. JAMA 2017;317:1309–10. 10.1001/jama.2017.0616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spatz ES, Elwyn G, Moulton BW, et al. Shared decision making as part of value based care: new U.S. policies challenge our readiness. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2017;123-124:104–8. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2006;60:301–12. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, et al. Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Med Decis Making 2007;27:539–46. 10.1177/0272989X07306779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beach MC, Callon W, Boss E. Patient-Centered decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1–2. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pieterse AH, Bomhof-Roordink H, Stiggelbout AM. On how to define and measure SDM. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:1307–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gärtner FR, Bomhof-Roordink H, Smith IP, et al. The quality of instruments to assess the process of shared decision making: a systematic review. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191747 10.1371/journal.pone.0191747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clayman ML, Gulbrandsen P, Morris MA. A patient in the clinic; a person in the world. Why shared decision making needs to center on the person rather than the medical encounter. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:600–4. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomlinson JP. Shifting the focus of shared decision making to human relationships. BMJ 2018;360 10.1136/bmj.k53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kunneman M, Gionfriddo MR, Toloza FJK, et al. Humanistic communication in the evaluation of shared decision making: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:452–66. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:295–301. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1361–7. 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simon D, Schorr G, Wirtz M, et al. Development and first validation of the shared decision-making questionnaire (SDM-Q). Patient Educ Couns 2006;63:319–27. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ 1999;319:766–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-Making in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:651–61. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00145-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lown BA, Clark WD, Hanson JL. Mutual influence in shared decision making: a collaborative study of patients and physicians. Health Expect 2009;12:160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JCJM. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1172–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ 2017;359 10.1136/bmj.j4891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rusiecki J, Schell J, Rothenberger S, et al. An innovative shared decision-making curriculum for internal medicine residents: findings from the University of Pittsburgh medical center. Acad Med 2018;93:937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elwyn G, Tsulukidze M, Edwards A, et al. Using a ‘talk’ model of shared decision making to propose an observation-based measure: Observer OPTION5 Item. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:265–71. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joseph-Williams N, Williams D, Wood F, et al. A descriptive model of shared decision making derived from routine implementation in clinical practice (‘Implement-SDM’): Qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1774–85. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Volk RJ, Shokar NK, Leal VB, et al. Development and pilot testing of an online case-based approach to shared decision making skills training for clinicians. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:95 10.1186/1472-6947-14-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Légaré F, Stacey D, Pouliot S, et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. J Interprof Care 2011;25:18–25. 10.3109/13561820.2010.490502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:554–64. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01515.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lenzen SA, Daniëls R, van Bokhoven MA, et al. Development of a conversation approach for practice nurses aimed at making shared decisions on goals and action plans with primary care patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:891 10.1186/s12913-018-3734-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murray E, Charles C, Gafni A, et al. Shared decision-making in primary care: tailoring the Charles et al. model to fit the context of general practice. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:205–11. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:892–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dobler CC, Midthun DE, Montori VM. Quality of shared decision making in lung cancer screening: the right process, with the right partners, at the right time and place. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2017;92:1612–6. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chor J, Stulberg DB, Tillman S. Shared decision-making framework for pelvic examinations in asymptomatic, nonpregnant patients. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:810–4. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rennke S, Yuan P, Monash B, et al. The SDM 3 circle model: a literature synthesis and adaptation for shared decision making in the hospital. J Hosp Med 2017;12:1001–8. 10.12788/jhm.2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Park ES, Cho IY. Shared decision-making in the paediatric field: a literature review and concept analysis. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:478–89. 10.1111/scs.12496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karkazis K, Tamar-Mattis A, Kon AA. Genital surgery for disorders of sex development: implementing a shared decision-making approach. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2010;23:789–805. 10.1515/jpem.2010.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saidinejad M. The patient-centered emergency department. Adv Pediatr 2018;65:105–20. 10.1016/j.yapd.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eliacin J, Salyers MP, Kukla M, et al. Patients’ Understanding of Shared Decision Making in a Mental Health Setting. Qual Health Res 2015;25:668–78. 10.1177/1049732314551060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grim K, Rosenberg D, Svedberg P, et al. Shared decision-making in mental health care—A user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2016;11:30563 10.3402/qhw.v11.30563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langer DA, Jensen-Doss A. Shared decision-making in youth mental health care: using the evidence to plan treatments collaboratively. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2018;47:821–31. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1247358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Probst MA, Noseworthy PA, Brito JP, et al. Shared decision-making as the future of emergency cardiology. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:117–24. 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Schoenfeld EM, et al. Shared Decisionmaking in the emergency department: a guiding framework for clinicians. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:688–95. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kane HL, Halpern MT, Squiers LB, et al. Implementing and evaluating shared decision making in oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:377–88. 10.3322/caac.21245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bomhof-Roordink H, Fischer MJ, van Duijn-Bakker N, et al. Shared decision making in oncology: a model based on patients', health care professionals', and researchers' views. Psychooncology 2019;28:139–46. 10.1002/pon.4923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect 2006;9:25–36. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00359.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ng CJ, Lee YK, Abdullah A, et al. Shared decision making: a dual-layer model to tackling multimorbidity in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract 2019. 10.1111/jep.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Truglio-Londrigan M, Slyer JT. Shared decision-making for nursing practice: an integrative review. Open Nurs J 2018;12:1–14. 10.2174/1874434601812010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moore CL, Kaplan SL. A framework and resources for shared decision making: opportunities for improved physical therapy outcomes. Phys Ther 2018;98:1022–36. 10.1093/ptj/pzy095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van de Pol MHJ, Fluit CRMG, Lagro J, et al. Expert and patient consensus on a dynamic model for shared decision-making in frail older patients. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1069–77. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jansen J, Naganathan V, Carter SM, et al. Too much medicine in older people? deprescribing through shared decision making. BMJ 2016;353 10.1136/bmj.i2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 1997;44:681–92. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gillick MR. Re-Engineering shared decision-making. J Med Ethics 2015;41:785–8. 10.1136/medethics-2014-102618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Peek ME, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, et al. How is shared decision-making defined among African-Americans with diabetes? Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:450–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. BMJ 2014;348:g3178 10.1136/bmj.g3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:291–309. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Institute of medicine (US) Committee on quality of health care in America. crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kunneman M, Branda ME, Hargraves I, et al. Fostering choice awareness for shared decision making: a secondary analysis of Video-Recorded clinical encounters. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2018;2:60–8. 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kunneman M, Engelhardt EG, ten Hove FLL, et al. Deciding about (neo-)adjuvant rectal and breast cancer treatment: Missed opportunities for shared decision making. Acta Oncol 2016;55:134–9. 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1068447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Couët N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, et al. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the option instrument. Health Expect 2015;18:542–61. 10.1111/hex.12054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tamirisa NP, Goodwin JS, Kandalam A, et al. Patient and physician views of shared decision making in cancer. Health Expect 2017;20:1248–53. 10.1111/hex.12564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hamann J, Heres S. Why and how family caregivers should participate in shared decision making in mental health. Psychiatric Serv 2019;70:418–21. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Salzburg Global Seminar Salzburg statement on shared decision making. BMJ 2011;342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031763supp001.pdf (58.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-031763supp002.pdf (198.6KB, pdf)