Abstract

Objectives

The 20 m shuttle run test (20mSRT) is used to estimate cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) through the prediction of peak oxygen uptake (), but its validity as a measure of CRF during childhood and adolescence is questionable. This study examined the validity of the 20mSRT to predict peak .

Methods

Peak was measured during treadmill running. Log-linear regression was used to correct peak for body mass and sum of skinfolds plus age. Boys completed the 20mSRT under standardised conditions. Maximum speed (km/h) was used with age to predict peak using the equation developed by Léger et al. Validity was examined from linear regression methods and limits of agreement (LoA). Relationships between 20mSRT performance and allometrically adjusted peak , and predicted per cent fat were examined.

Results

The sample comprised 76 boys aged 11–14 years. Predicted and measured mass-related peak (mL/kg/min) shared common variance of 32%. LoA revealed that measured peak ranged from 15% below to 25% above predicted peak . There were no significant relationships (p>0.05) between predicted peak and measured peak adjusted for mass, age and skinfold thicknesses. Adjusted for body mass and age, peak was not significantly related (p>0.05) to 20mSRT final speed but a weak, statistically significant (r=0.24, p<0.05) relationship was found with peak adjusted for mass and fatness. Predicted per cent fat was negatively correlated with 20mSRT speed (r=−0.61, p<0.001).

Conclusions

The 20mSRT reflects fatness rather than CRF and has poor validity grounded in its flawed estimation and interpretation of peak in mL/kg/min.

Keywords: children, exercise testing, fitness testing

What are the findings?

The 20 m shuttle run test (20mSRT) is not a valid test of cardiorespiratory fitness in boys aged 11–14 years.

The prediction and use of mass-related peak oxygen uptake from 20mSRT performance to interpret cardiorespiratory fitness in young people is flawed.

20mSRT performance reflects relative fatness rather than cardiorespiratory fitness.

How might they impact on clinical practice in the future?

The 20mSRT is inappropriate for assessing young people’s cardiorespiratory fitness.

Assigning individual children or adolescents as having poor cardiovascular health profiles based on 20mSRT predicted peak oxygen uptake is physiologically and statistically unjustified.

Introduction

Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) reflects the body’s integrated ability to deliver oxygen from the atmosphere to the skeletal muscles and to consume it to provide energy to support muscular activity during exercise. The health-related benefits of CRF are widely recognised,1 cardiorespiratory exercise tests are an established component of paediatric exercise medicine2 and the clinical assessment of peak is a routine element of disease evaluation3 and intervention monitoring.4 According to a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association, CRF can be considered ‘a reflection of total body health’ (Ross, p. e654).5 However, the use of CRF in clinical practice and health-related recommendations with children and adolescents must be founded on its rigorous assessment and interpretation.

Laboratory determined peak oxygen uptake () is the ‘gold standard’ measure of young people’s CRF and its assessment, interpretation and development are extensively documented.6–8 However, rigorous determination of the peak of large samples of young people requires technical expertise, interpersonal skills, sophisticated apparatus and significant laboratory resources. These extensive requirements appear to have stimulated a resurgence of interest in estimating/predicting young people’s peak from performance on the 20 m shuttle run test (20mSRT).9

Over 30 years ago, we investigated the 20mSRT10 as a potential means for assessing CRF. On finding a common variance (r2) of 29% between 20mSRT performance and laboratory-determined peak in pre-adolescent and early adolescent boys, we concluded that the 20mSRT was not a valid surrogate for rigorously measured peak .11 We assumed that with the development of new technologies the use of performance tests in scientific and medical research would gradually disappear. On the contrary, judging by the plethora of publications in the last few years the 20mSRT appears to have become the method of choice in determining youth CRF in scientific, medical and health-related research.12–14

Prominent advocates of the 20mSRT15 recommend the equation developed by Léger et al 16 for those aged 8–19 years as the basis for predicting CRF. Using this equation, Léger et al 16 reported predicted peak to have a correlation of r=0.71 with peak predicted from retro-extrapolation to measured at the end of the test. Reported SE of the estimate (SEE) was 5.9 mL/kg/min or 12.1%. Thus, although the equation developed by Léger e t al was not originally tested against directly measured peak , it has been used to predict peak from 20mSRT performance scores which have been used to construct international CRF ‘norms’,13 examine intercountry comparisons12 and to generate temporal trends in CRF.14 The protocol has even been modified to develop ‘reference standards’ for children as young as 2 years of age.17 Moreover, 20mSRT performance has been recommended to evaluate physical activity interventions,18 to survey and monitor international health and fitness,19 to determine metabolic and cardiovascular risk20 and to identify individuals who warrant intervention to improve their current and future health.21

Proponents of the 20mSRT claim that there has been, ‘a substantial decline in CRF since 1981, which is suggestive of a meaningful decline in population health’ (Tomkinson, p. 4).14 As well-documented22 and resolved in the IOC Consensus Statement on health and fitness of young people,23 there is no compelling evidence to suggest that youth CRF has declined over this period. In explanation of the alleged decline in CRF, 20mSRT advocates have asserted that, ‘direct analysis of the causal fitness-fatness connection indicates that increases in fatness explain 35%–70% of the declines in CRF’ (Tomkinson, p. 5).14 But fat is largely metabolically inert and there is no ‘causal fitness-fatness connection’.24 Being fat is not the same as being unfit. These contrasting findings do, however, clearly illustrate the difference between true CRF and the willingness and capability of individuals to carry their body mass between two lines 20 m apart and maintain the required running speed. Fat mass does not influence CRF,24 but carrying fat as ‘deadweight’ does increase the work performed in each 20 m shuttle and adversely affect 20mSRT performance.

This misinterpretation of data is compounded further by 20mSRT equations predicting peak expressed in simple ratio with body mass, that is, as mL/kg/min. This is a fundamental methodological flaw which was elegantly explained by Tanner25 70 years ago and confirmed by ourselves in children in 1992.26 Given these concerns, the present paper aimed to i) empirically investigate 20mSRT predicted peak as a valid estimate of laboratory-determined peak expressed as a simple per body mass ratio and appropriately adjusted for age, body size and fatness and ii) examine the influence of body fatness on shuttle run performance expressed as maximal speed.

Methods

We have re-visited our raw data, calculated predictions of peak from 20mSRT performance using currently recommended equations and methodology and investigated 20mSRT estimations of peak in relation to treadmill-determined peak and a range of appropriately scaled morphological covariates.

Participants

Seventy-six boys aged 11–14 years from a local state school volunteered to participate in a project investigating CRF and cardiovascular health. All boys and their guardians provided written informed consent. Participants were habituated to the laboratory environment, personnel and experimental procedures prior to data collection.

Experimental procedures

Anthropometry

Maturity status was visually assessed by a medical doctor and recorded by a nurse based on indices for pubic hair development.27 Anthropometric measures were taken as described by the International Biological Programme.28 Stature was measured with a Harpenden Stadiometer and body mass determined using Avery balance scales (Avery, Birmingham, UK). Skinfold thicknesses at triceps and subscapular sites were measured by the same experienced investigator using Holtain skinfold callipers (Holtain, Crosswell, UK). Per cent fat was predicted from maturity status, body mass and skinfold thicknesses using sex-specific equations.29

Peak oxygen uptake

Peak was determined on a motorised treadmill (Woodway, Cranlea Medical, Birmingham, UK) using a discontinuous, incremental protocol. Tests began with a 5 min warm-up at a belt speed of 8 km.h-1 (2.22 m.s-1). The belt speed was increased to 10 km.h-1 (2.78 m.s-1) and the treadmill gradient was raised by 2.0% every 3 min interspersed with 1 min rest. Boys continued running until voluntary exhaustion. Heart rate and expired respiratory gases were monitored continuously using an electrocardiograph (Cardionics, Stockholm, Sweden) and an online respiratory gas-analysis system (Covox, Exeter, UK), which was calibrated against reference gases and an appropriate range of flow rates using a Hans Rudolph calibration syringe (Cranlea, Birmingham, UK) before each test. The highest 30 s was accepted as a maximal value if signs of intense exertion (eg, hyperpnea, facial flushing unsteady gait, profuse sweating) were demonstrated and supported by a heart rate which was levelling-off over the final stages of the test at a value within 5% of previously measured mean maximal heart rates of boys aged 11–14 years.

20 m shuttle run

The 20mSRT was performed in a school gymnasium. The boys ran in small groups back and forth between two lines at a measured distance of 20 m apart. Following a brief warm-up, the test started at a speed of 8.5 km.h-1 and increased by 0.5 km.h-1 every minute in accordance with audio signals emitted at set intervals from a prerecorded tape. Each boy continued until he could no longer maintain the pace. The final speed was noted and, with age, converted into predicted peak using the equation developed by Léger et al 16:

where Y is peak (mL/kg/min); X 1 is maximal shuttle running speed (km.h-1) and X 2 is age (years).

Data analyses

Data were analysed using SPSS V.24 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Descriptive data (means and SD) were computed for the boys’ physical characteristics, maximal performance in the 20mSRT and for absolute (L.min-1) and mass-related (mL/kg/min) treadmill-determined peak . Significance was accepted as p≤0.05.

Validity of 20mSRT using recommended per body mass comparisons

The strength of the linear relationship between predicted and measured peak , expressed in mL/kg/min, was investigated using Pearson’s correlation. Subsequently, Bland and Altman30 limits of agreement (LoA) between predicted peak and treadmill determined peak , expressed in mL/kg/min, were computed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Allometric relationships between treadmill peak and anthropometric measures were investigated using log-linear regression.31 Initially, body mass was included as a sole covariate. In subsequent analyses, age was added with body mass and, finally, sum of two skinfold thicknesses. The log-linear regression equations obtained were used to calculate loge peak adjusted for these covariates as appropriate. The antilog of these values provided adjusted peak expressed in L.min-1. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed between 20mSRT performance (predicted peak (mL/kg/min) and maximum speed attained (km.h-1)) versus peak allometrically adjusted for body mass, age and sum of skinfolds. The relationship between predicted fat per cent29 and 20mSRT performance (maximal speed) was examined using Pearson’s correlation.

Results

Descriptive data for the boys’ physical characteristics are presented in table 1. Table 2 summarises the 20mSRT results expressed in maximum speed attained (km.h-1) and predicted mass-related peak (mL/kg/min) and contains a comparative value for treadmill determined mass-related peak .

Table 1.

Physical characteristics

| Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 12.7 | 1.0 |

| Stature (m) | 1.54 | 0.09 |

| Body mass (kg) | 43.4 | 9.1 |

| Sum of triceps and subscapular skinfolds (mm) | 18.5 | 7.3 |

| Predicted fat* (%) | 16.1 | 6.1 |

*Predicted from the equations of Slaughter et al.29

Table 2.

20 m shuttle run and treadmill-determined exercise data

| Mean | SD | |

| 20 m shuttle run data | ||

| Maximum 20 m shuttle run speed (km.h-1) | 10.9 | 0.9 |

| Predicted peak oxygen uptake* (mL/kg/min) | 47 | 5 |

| Treadmill-determined data | ||

| Peak oxygen uptake (L.min-1) | 2.10 | 0.47 |

| Peak oxygen uptake (mL/kg/min) | 48 | 6 |

| Peak oxygen uptake adjusted† for body mass (L.min-1) | 2.08 | 0.39 |

| Peak oxygen uptake adjusted† for body mass and age (L.min-1) | 2.09 | 0.40 |

| Peak oxygen uptake adjusted† for body mass and skinfolds (L.min-1) | 2.08 | 0.43 |

| Peak heart rate (beats.min-1) | 201 | 8 |

*Predicted using the equation developed by Léger et al.16

†Values adjusted for the specified covariates in log-linear regression analyses.

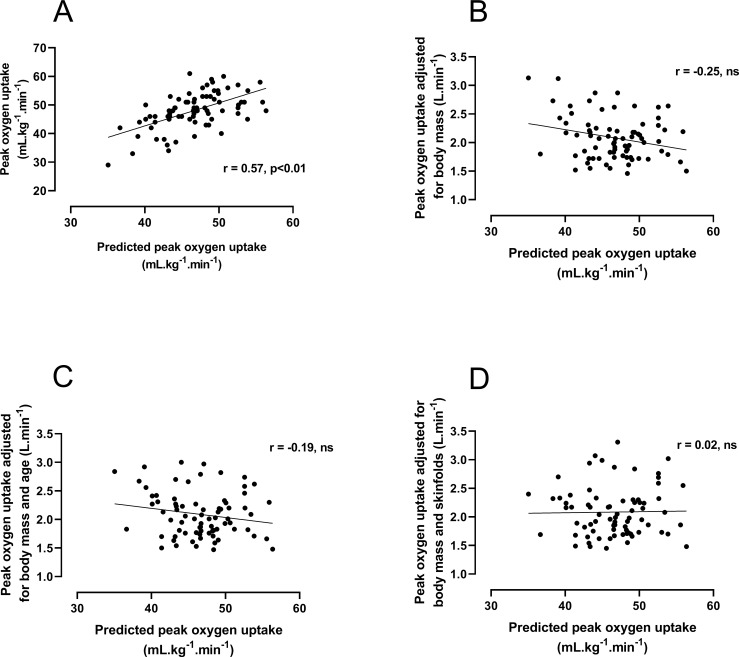

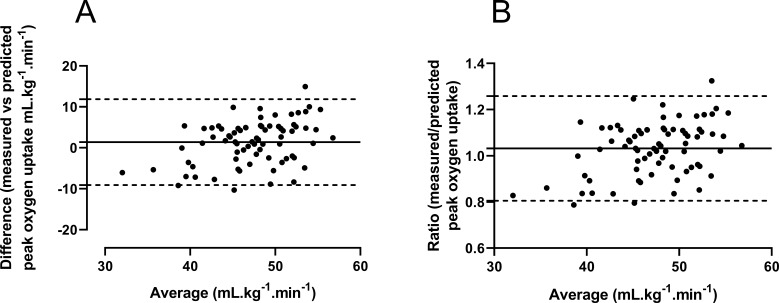

Figure 1A illustrates the linear relationship between 20mSRT predicted and treadmill-determined values of mass-related peak . The Pearson’s correlation analysis demonstrated a shared variance (r2) of 32%. Initial graphical analysis (figure 2A) of the differences between predicted and measured peak versus their average yielded a bias of 1.4 mL/kg/min with 95% LoA of −9.1 to +11.9 mL/kg/min. The differences were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test, p>0.05), but the size of the difference was significantly related to the average of the two peak measurements (Spearman’s rank correlation r=0.34, p<0.01). Therefore, the data were expressed as the ratio between the two scores versus the average score30 (figure 2B). This analysis revealed minimal bias (mean ratio 1.03) but measured peak ranged from 15% below (ratio 0.85) to 25% above (ratio 1.25) 20mSRT predicted peak .

Figure 1.

20 m shuttle run test predicted peak oxygen uptake (mL/kg/min) vs (A) laboratory measured peak oxygen uptake (mL/kg/min), (B) following allometric adjustment for body mass, (C) body mass and age and (D) body mass and sum of triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plots of predicted (Léger et al 16) vs (A) treadmill-determined peak oxygen uptake expressed in mL/kg/min) and (B) expressed as the ratio of predicted/measured peak oxygen uptake vs average.

Investigating the log-linear relationships between peak and body mass, age and sum of skinfolds yielded the following results: with loge body mass as the sole covariate: constant: −2.61; mass exponent: 0.89 (SE 0.08); for loge body mass and age: constant: −2.74; mass exponent: 0.74 (SE, 0.09), coefficient for age: 0.05 (SE, 0.02); with loge sum of skinfolds added as a covariate, the age term became redundant (p>0.05): constant: −2.55; mass exponent: 1.10 (SE 0.08); skinfolds exponent: −0.298 (SE, 0.05). Values for peak adjusted according to these three equations and expressed in L.min-1 (ie, the antilog of the predicted values) are presented in table 2. Relationships between allometrically adjusted peak and 20mSRT predicted peak are shown in figure 1B–D. These graphs show that once CRF was appropriately adjusted there was no significant (p>0.05) residual correlation between actual and 20mSRT predicted peak .

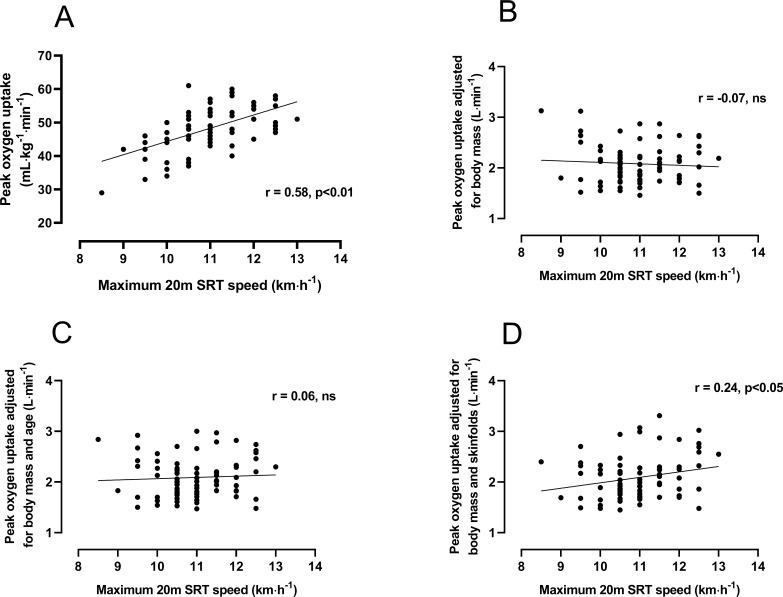

Relationships between mass-related and allometrically adjusted peak and 20mSRT maximum speed are illustrated graphically in figure 3. Peak in mL/kg/min was significantly (p<0.01) related to maximum 20mSRT speed with a common variance of 34%, but once scaled for body mass or body mass plus age, this relationship was non-significant (p>0.05). With peak adjusted for body mass and skinfolds, a weak, significant (p<0.05) relationship with 20mSRT speed was observed. Further investigation of this revealed an SEE of 0.42 L.min-1 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.50 (L.min-1) representing a coefficient of variation of 21.5%).

Figure 3.

Relationships between maximal 20 m shuttle run test (20mSRT) speed and (A) peak oxygen uptake expressed in mL/kg/min and (B) after allometric adjustment for body mass, (C) body mass and age and (D) body mass and sum of two skinfolds.

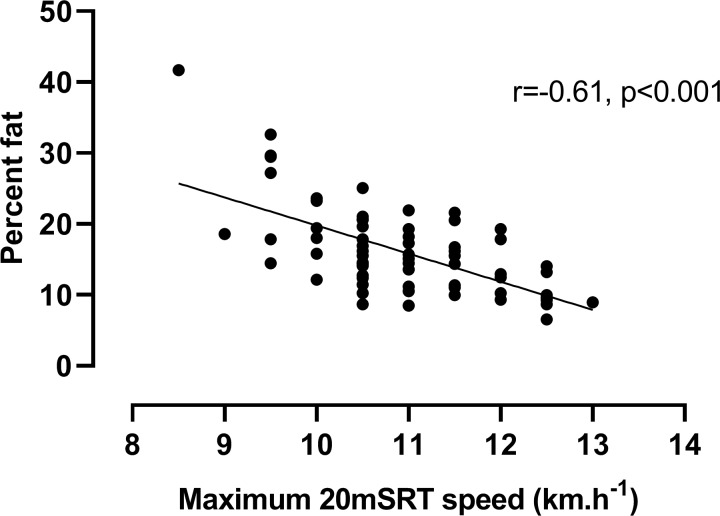

Finally, the statistically significant, negative (p<0.001) relationship between predicted per cent fat and 20mSRT performance (maximum running speed) is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Relationship between predicted per cent body fat and 20 m shuttle run test (20mSRT) maximum running speed.

Discussion

Predicted versus measured peak : correlation and linear regression

This study examined the validity of the 20mSRT to predict laboratory-determined peak in boys aged 11–14 years. When, for comparative purposes only, data were analysed as recommended by proponents of the test, that is, as predicted versus laboratory measured peak expressed in ratio with body mass, the moderate correlation coefficient obtained indicated a common variance of 32%. More appropriate statistics30 investigating agreement between the two scores, yielded LoA demonstrating that 95% of the time, directly measured peak ranged from 15% below to 25% above 20mSRT predicted peak .

Most studies assess validity based on Pearson’s correlation. This is well-recognised as a poor indicator of agreement between two measurement methods being based on linear association and sensitive to sample heterogeneity.32 Data from the present study are, however, in line with a meta-analysis of 20mSRT validity,33 which noted that over half of published validity studies with children report a common variance of <50% between predicted and measured peak . Some studies with children and adolescents have reported validity based on SEE of the linear regression between predicted and measured peak . These studies were recently summarised by Tomkinson et al 15 into an average SEE of 4.9 mL/kg/min. These authors also reported the ‘95% likely range for a true peak predicted from the 20mSRT to be around 10 mL/kg/min or 24%’ (Tomkinson, p. 154).15 However, these analyses are similarly based on linear association and so are subject to the same limitations as for correlational analyses.

Predicted versus measured peak : limits of agreement

Only one previous study appears to have examined agreement between measured and predicted peak using LoA: Matsuzuka et al 34 compared measurements from a sample of participants aged 8–17 years. Based on the equation developed by Léger e t al, LoA of −9.8 to +6.4 mL/kg/min were reported, a range representing ∼32% of measured peak . In the present sample of boys, our LoA are slightly larger, approximating 40% of measured peak . Neither study presents convincing evidence for the validity of the 20mSRT to either reflect young peoples’ peak or assign individuals into high, medium or low CRF groups. This is particularly important given current trends towards classifying individuals by single 20mSRT-predicted peak ‘cut-off’ points as warranting targeted interventions for cardiovascular prevention.21 Moreover, the use of a single value peak ‘cut-off’ point, typically 42 mL/kg/min for boys aged 8–18 years, has no scientific basis as CRF increases with age-driven and maturity status-driven concurrent changes in anthropometric and physiological variables with the timing and tempo of these changes specific to individuals.35–37

Validity of peak expressed as per body mass ratios

Concerns over the validity of the 20mSRT to predict CRF should also focus on its overriding weakness: its reliance on equations that only predict peak expressed in ratio with body mass. There is now unequivocal evidence to refute this contention including the data from the present study which, once differences in age were controlled for, reported a mass exponent of 0.74 (SE 0.09)—a value significantly different from the exponent of 1.0 assumed by ratio scaling.

We have recently reanalysed treadmill peak from 20 published cross-sectional data sets collected, using rigorous and consistent methodology, in our laboratory over a period of 30 years.38 In none of these cross-sectional data sets, based on males and females aged 9–18 years, was simple ratio scaling adequate to normalise data. Similarly, longitudinal data based on over 1000 individual treadmill-determined peak tests35 confirmed that i) if peak is allometrically scaled with body mass as the sole covariate, the value of the mass exponent is significantly lower than 1.0, ii) that ratio scaling with body mass is too simplistic to describe peak from prepuberty through to postpuberty and iii) that age-driven and maturity status-driven changes in fat-free mass (reflected here by body mass and skinfold thicknesses) underpin adolescent growth in peak . Thus, based on our own recently analysed data comprising over 2000 laboratory determinations of peak plus data from systematic reviews,35–39 we believe that there is overwhelming evidence to refute the validity of any CRF test based on ratio scaling. Moreover, specific verification of this in the present data can be seen in figure 1B–1D, which graphically and statistically confirm that no significant relationship existed between measured and predicted 20mSRT CRF once the laboratory data were appropriately scaled for age and anthropometric covariates.

Relationships between allometrically scaled peak and 20mSRT maximum speed

Although the vast majority of published studies of 20mSRT performance compute and report mass-related peak , good practice recommendations from advocates of the test include reporting the number of stages or maximal speed attained, with the latter suggested as the only ‘unequivocal metric’.15 Having shown 20mSRT predicted peak to lack validity as well as being grounded in inappropriate normalisation for body size, we explored relationships between allometrically scaled peak and 20mSRT maximum speed. For illustrative purposes, figure 3A reveals a significant relationship between mass-related peak and maximum speed: a spurious correlation reflecting inappropriate per body mass scaling.25 26 38 However, once adjusted for body mass using allometric methods (figure 3B) or mass and age (figure 3C), this relationship became non-significant. Interestingly, when adjusted for body mass and skinfolds, as demonstrated to best reflect adolescent changes in CRF,35 36 a weak but significant correlation was observed. However, a common variance of 6% and a coefficient of variation of 21.5% does not represent convincing support for the use of 20mSRT maximal speed to reflect CRF in boys aged 11–14 years.

Influence of overweight and 20mSRT performance

Where CRF is expressed in mL/kg/min, it is unsurprising that children and adolescents who are overweight or have obesity score poorly on the 20mSRT as they are doubly penalised: first through increased individual workload from carrying excess fat mass during shuttle running and second via the use of this low score to predict mass-related CRF. Here, they are penalised a second time as the denominator includes both fat-free mass (which contributes to CRF) and fat mass (which does not). As we noted earlier, there is no causal relationship between fatness and CRF.24 Indeed, in our recent longitudinal analysis of CRF in boys aged 10–18 years, we demonstrated empirically that once body mass and skinfold thicknesses were appropriately accounted for in a log-linear multilevel model, the difference in CRF between boys considered overweight and boys in the normal weight range for their age and stature was removed.35

Data from the present study were used to provide explicit insights into the effect of excess body fat on 20mSRT performance: despite this being a sample of normal, healthy teenage boys with only five (6%) classified as overweight according to international cut-off points,40 figure 4 clearly illustrates the decline in 20mSRT maximal speed with increased fatness—a relationship which is likely to be strengthened in groups of individuals with higher levels of adiposity. Using 20mSRT performance as a measure of CRF in overweight young people may therefore lead to spurious relationships with indicators of health where associations with, for example, cardiovascular risk factors are more likely to reflect overweight or obese status than true CRF.41–43

Conclusions

In this study, we have presented empirical evidence to show that the 20mSRT is not a valid predictor of CRF in boys aged 11–14 years. International recommendations for its use are therefore unjustified, misleading and potentially undermining a generation of research into current and future CRF and health. We encourage researchers and medical practitioners involved with health promotion in young people to abandon its use, whenever possible, and to turn to more rigorous, scientific assessments of CRF.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the commitment of the participants and the technical assistance of the Children’s Health and Exercise Research Centre team.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Jo Welsman

Contributors: JW and NA jointly conceived and designed the research, led the research team and analysed the data. Both authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, both authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by Northcott Devon Medical Foundation and the Darlington Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: Patient involvement in this study was not appropriate.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was received from the Exeter and District Health Authority Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Contact: n.armstrong@exeter.ac.uk

References

- 1. Armstrong N, van Mechelen W, Oxford textbook of children’s sport and exercise medicine. 3rd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rowland TW. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in children and adolescents. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2018: 1–262. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guimarães GV, d'Avila VM, Camargo PR, et al. Prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in children with heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in a non-β-blocker therapy setting. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:560–5. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Radtke T, Nevitt SJ, Hebestreit H, et al. Physical exercise training for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;49 10.1002/14651858.CD002768.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, et al. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;134:e653–99. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armstrong N, McManus AM. Aerobic fitness : Armstrong N, van Mechelen W, Oxford textbook of children’s sport and exercise medicine. 3rd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: 161–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Falk B, Dotan R. Measurement and interpretation of maximal aerobic power in children. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2019;31:144–51. 10.1123/pes.2018-0191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McManus AM, Armstrong N. Maximal oxygen uptake : Rowland TW, Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in children and adolescents. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2018: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Welsman J, Armstrong N. Children’s fitness and health: an epic scandal of poor methodology, inappropriate statistics, questionable editorial practices and a generation of misinformation. Bmj Ebm 2019. 10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Léger LA, Lambert J. Maximal.multistage 20-m Shuttle Run Test to Predict VO2 max. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1982;49:1–12. 10.1007/bf00428958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Armstrong N, Williams J, Ringham D. Peak oxygen uptake and progressive shuttle run performance in boys aged 11-14 years. Br J Phys Educ 1988;19:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lang JJ, Tremblay MS, Léger L, et al. International variability in 20 m shuttle run performance in children and youth: who are the fittest from a 50-country comparison? A systematic literature review with pooling of aggregate results. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:276 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay MS, et al. International normative 20 m shuttle run values from 1 142 026 children and youth representing 50 countries. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1545–54. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-095987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay M. Temporal trends in the cardiorespiratory fitness of children and adolescents representing 19 high-income and upper middle-income countries between 1981 and 2014. Br J Sports Med 2017;0:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Blanchard J, et al. The 20-m shuttle run: assessment and interpretation of data in relation to youth aerobic fitness and health. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2019;31:152–63. 10.1123/pes.2018-0179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Léger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C, et al. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci 1988;6:93–101. 10.1080/02640418808729800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cadenas-Sanchez C, Intemann T, Labayen I, et al. Physical fitness reference standards for preschool children: the PREFIT project. J Sci Med Sport 2019;22:430–7. 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.09.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lang JJ, Wolfe Phillips E, Orpana HM, et al. Field-based measurement of cardiorespiratory fitness to evaluate physical activity interventions. Bull World Health Organ 2018;96:794–6. 10.2471/BLT.18.213728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lang JJ, Tomkinson GR, Janssen I, et al. Making a case for cardiorespiratory fitness surveillance among children and youth. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2018;46:66–75. 10.1249/JES.0000000000000138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lang JJ, Belanger K, Poitras V, et al. Systematic review of the relationship between 20 M shuttle run performance and health indicators among children and youth. J Sci Med Sport 2018;21:383–97. 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ruiz JR, Cavero-Redondo I, Ortega FB, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness cut points to avoid cardiovascular disease risk in children and adolescents; what level of fitness should raise a red flag? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1451–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Armstrong N, Tomkinson G, Ekelund U. Aerobic fitness and its relationship to sport, exercise training and habitual physical activity during youth. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:849–58. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mountjoy M, Andersen LB, Armstrong N, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on the health and fitness of young people through physical activity and sport. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:839–48. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goran M, Fields DA, Hunter GR, et al. Total body fat does not influence maximal aerobic capacity. Int J Obes 2000;24:841–8. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tanner JM. Fallacy of per-weight and per-surface area Standards, and their relation to spurious correlation. J Appl Physiol 1949;2:1–15. 10.1152/jappl.1949.2.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams JR, Armstrong N, Winter EM. Changes in peak oxygen uptake with age and sexual maturation in boys: physiological fact or statistical anomaly? : Coudert J J, Van Praagh E, Pediatric work physiology. Paris: Masson, 1992: 35–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence. 2nd edn Oxford: Blackwell, 1962: 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiner JS, Lourie JA. Practical human biology. London: Academic Press, 1981: 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Slaughter MH, Lohman TG, Boileau RA, et al. Skinfold equations for estimation of body fatness in children and youth. Hum Biol 1988;60:709–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res 1999;8:135–60. 10.1177/096228029900800204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nevill AM, Holder RL. Scaling, normalizing, and per ratio standards: an allometric modeling approach. J Appl Physiol 1995;79:1027–31. 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.3.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med 2000;30:1–15. 10.2165/00007256-200030010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mayorga-Vega D, Aguilar-Soto P, Viciana J. Criterion-related validity of the 20-m shuttle run test for estimating cardiorespiratory fitness: a meta-analysis. J Sports Sci Med 2015;14:536–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Matsuzaka A, Takahashi Y, Yamazoe M, et al. Validity of the multistage 20-m shuttle-run test for Japanese children, adolescents, and adults. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2004;16:113–25. 10.1123/pes.16.2.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Armstrong N, Welsman J. Sex-specific longitudinal modelling of youth aerobic fitness. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2019;31:204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Armstrong N, Welsman J. Development of peak oxygen uptake from 11-16 years determined using both treadmill and cycle ergometry. Eur J Appl Physiol 2019;85:546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Armstrong N, Welsman J. Multilevel allometric modelling of maximal stroke volume and peak oxygen uptake in 11–13-year-olds. Eur J Appl Physiol 2019;119:2629–39. 10.1007/s00421-019-04241-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Welsman J, Armstrong N. Interpreting aerobic fitness in youth: the fallacy of ratio scaling. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2019;31:184–90. 10.1123/pes.2018-0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lolli L, Batterham AM, Weston KL, et al. Size exponents for scaling maximal oxygen uptake in over 6500 humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2017;47:1405–19. 10.1007/s40279-016-0655-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loftin M, Sothern M, Abe T, et al. Expression of VO2peak in children and youth, with special reference to allometric scaling. Sports Med 2016;46:1451–60. 10.1007/s40279-016-0536-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mintjens S, Menting MD, Daams JG, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood and adolescence affects future cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Sports Med 2018;48:2577–605. 10.1007/s40279-018-0974-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Armstrong N, Welsman J. Youth cardiorespiratory fitness: evidence, myths and misconceptions. Bull World Health Org 2019;97:777–82. 10.2471/BLT.18.227546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]