Abstract

Objective

Sexuality is an important aspect of human identity and contributes significantly to the quality of life in women as well as in men. Impairment in sexual health after vaginal delivery is a major concern for many women. We aimed to examine the association between degree of perineal tear and sexual function 12 months postpartum.

Design

A prospective cohort study

Setting

Four Danish hospitals between July 2015 and January 2019

Participants

A total of 554 primiparous women: 191 with no/labia/first-degree tears, 189 with second-degree tears and 174 with third-degree/fourth-degree tears. Baseline data were obtained 2 weeks postpartum by a questionnaire and a clinical examination. Sexual function was evaluated 12 months postpartum by an electronic questionnaire (Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ-12)) and a clinical examination.

Primary outcome measures

Total PISQ-12 score and dyspareunia

Results

Episiotomy was performed in 54 cases and 95 women had an operative vaginal delivery. The proportion of women with dyspareunia was 25%, 38% and 53% of women with no/labia/first-degree, second-degree or third-degree/fourth-degree tears, respectively.

Compared with women with no/labia/first-degree tears, women with second-degree or third-degree/fourth-degree tears had a higher risk of dyspareunia (adjusted relative risk (aRR) 2.05; 95% CI 1.51 to 2.78 and aRR 2.09; 95% CI 1.55 to 2.81, respectively). Women with third-degree/fourth-degree tears had a higher mean PISQ-12 score (12.2) than women with no/labia/first-degree tears (10.4).

Conclusions

Impairment of sexual health is common among primiparous women after vaginal delivery. At 12 months postpartum, more than half of the women with a third-degree/fourth-degree tear experienced dyspareunia. Women delivering with no/labia/first-degree tears reported the best outcomes overall. Thus, it is important to minimise the extent of perineal trauma and to counsel about sexuality during and after pregnancy.

Keywords: epidemiology, urogynaecology, maternal medicine, sexual medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study had a high follow-up rate for both the web-based questionnaire and clinical examination.

The study included both subjective and objective outcome measurements.

All the clinical examinations were performed by the same examiner raising a possible risk of intraobserver bias.

There was a risk of recall bias as information about pre-pregnancy sexual function was obtained postpartum.

Introduction

Sexuality is an important aspect of human identity and contributes significantly to the quality of life in women as well as in men.1 Sexual function postpartum is affected by the changes in hormonal milieu, anatomy and family structure following childbirth. Dyspareunia and other sexual problems, such as loss of sex drive, in the postpartum period is a well-known problem and frequencies of sexual health problems as high as 30%–60% three months postpartum and 17%–31% six months postpartum have been reported.2–7 A large cohort study from Sweden found vaginal or perineal tears, regardless of degree, to be associated with a delay in women’s resumption of sexual intercourse defined as more than 3 months after giving birth,8 while about 10% of primiparous women had not yet resumed sexual intercourse 6 months postpartum.3 The causes of sexual health problems are multifactorial and the mechanisms are still not fully understood.3–5 9 Thus, sexual health problems remains an unsolved problem for many women. Among other things, anatomical changes caused by vaginal or perineal tears may contribute to dyspareunia and have important effects on both the timing and quality of the resumption of sexual relations during the initial postpartum months.10 The association between obstetrical risk factors and postpartum sexual function is not yet well-described or understood, and thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the association between degree of perineal tear, sexual function and dyspareunia 12 months postpartum.

Methods

Study setting

This study is part of a larger prospective cohort study conducted at two universities and two tertiary hospital units in Denmark, Odense (OUH), Aarhus, Esbjerg and Kolding, between July 2015 and January 2019. The inclusion procedure and sample size calculation is described thoroughly elsewhere.11

Study population

The study involved three groups of women (i) 203 women with no/labia/first-degree perineal tears, (ii) 200 women with second-degree perineal tears and (iii) 200 women with third-degree/fourth-degree perineal tears.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design and conduct of this study.

Inclusion and follow-up procedure

Women delivering vaginally, at least 18 years old, and able to read and speak Danish were eligible. After the delivery, they were informed about the study. Further information was sent by email and the women were invited by phone to participate in a face-to-face interview including baseline questionnaires and a clinical examination comprising a perineal inspection at 16±5 days postpartum. Written informed consent was obtained at baseline.11 At 12 months postpartum, all participants received the same questionnaires electronically and were invited to a gynaecological examination. All examinations took place at the hospital and participants could bring their baby. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at OUH.12

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome was sexual function. We used the Danish version of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ-12).13 The PISQ-12 is a self-administered, objective and validated questionnaire with scores based on 12 questions to evaluate sexual function. The score of each item ranges from 0=never to 4=always (reverse scoring for questions 1, 2, 3 and 4). Missing responses are handled by multiplying the mean of answered items and the score is valid with up to two missing answers.13 The questionnaire has previously been used to evaluate sexual function after vaginal delivery.14 15 We used the total score (range 0–48) with lower scores indicating better sexual function, and the individual score for question 5, ‘Do you feel pain during sexual intercourse?’. The total score was used as a continuous variable presented as mean and SD, and the single score for question 5 was dichotomised as dyspareunia when answering ‘sometimes’, ‘usually’ or ‘always’ and no dyspareunia when answering ‘seldom’ or ‘never’.

Exposure variables and covariates

Degrees of perineal tears

The degree of perineal tear was defined according to the Green-top Guideline No. 29.16 First-degree tears were defined as injury to perineal skin and/or vaginal mucosa. Second-degree tears were defined as injury to perineum involving perineal muscles but not the anal sphincter. Third-degree and fourth-degree tears were defined as injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex. Episiotomies were lateral or mediolateral. Episiotomies equivalent to a second-degree tear were analysed independently, while episiotomies extending to the anal sphincter muscles were classified as a third-degree/fourth-degree tear.

Baseline information

At baseline, 16±5 days postpartum, a questionnaire was completed providing information about age (years), height (cm), smoking status (yes/no) and pregestational body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2). Information about pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period was obtained from the obstetric journal and included diabetes mellitus (yes/no), length of active birth and length of the second stage of labour (min), operative delivery (yes/no), birth weight (g) and head circumference (cm). The PISQ-12 was likewise completed at baseline providing information about pre-pregnancy sexual function. Question 5 was used and dichotomised as the postpartum score described in section Outcome measurements.

Clinical examination 12 months postpartum

Perineal length was evaluated by a gynaecological examination. All procedures were done by the first author (DG), with the women in the dorsal lithotomy position without bowel preparation. At the gynaecological examination, perineal body length was measured in centimetres, from the hymen to the middle of the anus during Valsalva manoeuvre as done in the Pelvic Organ Quantification system,17 and used as a dichotomous variable (≤2/>2 cm).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics according to degree of tear were described as frequencies for categorical variables. To investigate the association between the degree of perineal tear and dyspareunia or perineal body length, a relative risk (RR) regression by use of a generalised linear model with log link function and binomial distribution as statistical family was performed with estimates reported as RRs with 95% CIs. To investigate the association between the degree of perineal tear and sexual health problems measured as the total PISQ-12 score, a linear regression was performed, and results presented as regression coefficients (β) with 95% CIs. In the adjusted analysis, we controlled for pre-pregnancy dyspareunia, smoking, diabetes and operative delivery as categorical variables and age, BMI, duration of the second stage of labour, duration of active birth and birth weight as continuous variables. These potential confounders were chosen a priori based on directed acyclic graphs generated for the outcome variable using DAGitty V.2.3 as a graphical tool for analysing the causal diagrams.18 The analyses were carried out using Stata statistical software V.15.0.

Results

Participants

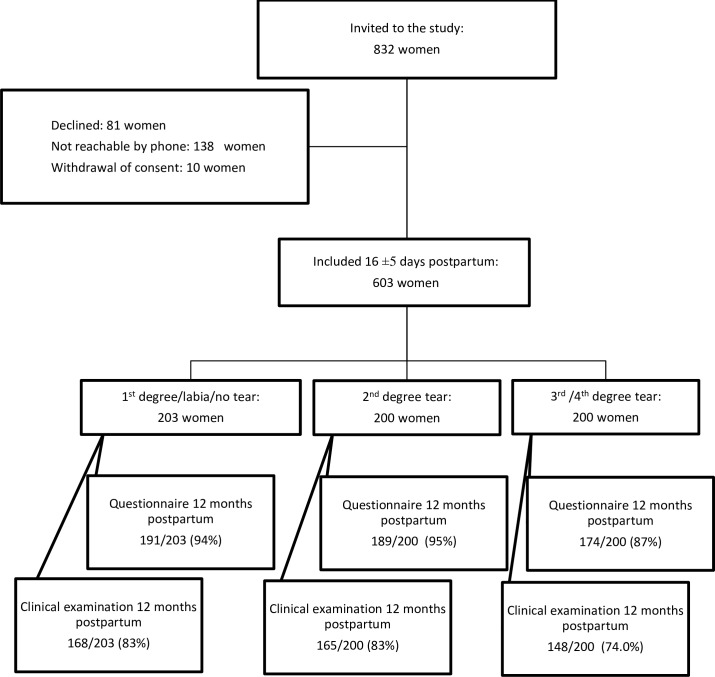

Initially, a total of 832 women were invited to participate in the study (figure 1). Of these, 81 declined and 138 could not be reached. This left 613 women completing a written consent and a baseline questionnaire who were booked for a clinical examination 16±5 days postpartum. A total of 10 women withdrew their consent. Thus, the study population comprised of 603 women. At the 1 year follow-up, 554 of the 603 women answered the web-based questionnaire corresponding to 92%, and 481 women had the clinical examination performed corresponding to 80%. Due to more than two missing answers, 13 women were excluded from analyses of total PISQ-12 score.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion and follow-up. Reasons for not participating in the clinical examination: withdrawal of consent/lost to follow-up: 111 women, moved away: 5 women, gave birth again: 5 women and dead: 1 woman.

Characteristics according to degree of tear

Women sustaining third-degree/fourth-degree tears were on average 0.5 years older than women sustaining second-degree tears and 1.2 years older than women sustaining no/labia/first-degree tears (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics according to degree of tear among primiparous women (n=554)

| Total (n=554) |

Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| (No/labia/first degree) (n=191) |

(Second degree) (n=189) |

(Third/fourth degree) (n=174) |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| BMI, pre-pregnancy (kg/m2)* | ||||

| <25 | 357 (64.6) | 128 (67.0) | 116 (61.7) | 113 (64.9) |

| 25–29.9 | 126 (22.8) | 41 (21.5) | 46 (24.5) | 39 (22.4) |

| ≥29.9 | 70 (12.7) | 22 (11.5) | 26 (13.8) | 22 (12.6) |

| Age at inclusion (years) | ||||

| ≤25 | 141 (25.5) | 63 (33.0) | 50 (26.5) | 28 (16.1) |

| 26–30 | 278 (50.2) | 91 (47.6) | 89 (47.1) | 98 (56.3) |

| >30 | 135 (24.4) | 37 (19.4) | 50 (26.5) | 48 (27.6) |

| Active birth duration (min) | ||||

| <220 | 140 (25.3) | 69 (36.1) | 46 (24.3) | 25 (14.4) |

| 221–340 | 141 (25.5) | 45 (23.6) | 53 (28.0) | 43 (24.7) |

| 341–570 | 143 (25.8) | 50 (26.2) | 49 (25.9) | 44 (25.3) |

| >570 | 130 (23.5) | 27 (14.1) | 41 (21.7) | 62 (35.6) |

| Second stage duration (min) | ||||

| <16 | 109 (19.7) | 40 (20.9) | 47 (24.9) | 22 (12.6) |

| 16–30 | 187 (33.8) | 80 (41.9) | 60 (31.8) | 47 (27.0) |

| 31–45 | 89 (16.1) | 31 (16.2) | 27 (14.3) | 31 (17.8) |

| >45 | 169 (30.5) | 40 (20.9) | 55 (29.1) | 74 (42.5) |

| Birth weight (g) | ||||

| <2999 | 76 (13.7) | 39 (20.4) | 23 (12.2) | 14 (8.1) |

| 3000–3499 | 193 (34.8) | 69 (36.1) | 81 (42.9) | 43 (24.7) |

| 3500–3999 | 210 (37.9) | 64 (33.5) | 65 (34.4) | 81 (46.6) |

| ≥4000 | 75 (13.5) | 19 (10.0) | 20 (10.6) | 36 (20.7) |

| Head circumference (cm)† | ||||

| <34 | 141 (25.5) | 58 (30.5) | 52 (27.7) | 31 (17.8) |

| 34 | 119 (21.6) | 45 (23.7) | 37 (19.7) | 37 (21.3) |

| 35 | 131 (23.7) | 35 (18.4) | 53 (28.2) | 43 (24.7) |

| >35 | 161 (29.2) | 52 (27.4) | 46 (24.5) | 63 (36.2) |

| Pre-pregnancy dyspareunia (yes) | 107 (19.3) | 26 (13.6) | 39 (20.6) | 42 (24.1) |

| Operative delivery (yes) | 95 (17.2) | 6 (3.1) | 29 (15.3) | 60 (34.5) |

| Episiotomies (yes) | 54 (9.8) | – | 32 (16.9) | 22 (12.6) |

| Smoker at inclusion (yes)* | 21 (3.8) | 8 (4.2) | 8 (4.2) | 5 (2.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes) | 19 (3.4) | 5 (2.6) | 7 (3.7) | 7 (4.0) |

*One missing value, n=553.

†Two missing values, n=552.

BMI, body mass index.

Moreover, a higher degree of tear was seen with higher birth weight, longer second stage of labour and longer duration of active birth. Instrumental delivery was more frequent among women with second-degree (15%) and third-degree/fourth-degree tears (34%) compared with women with no/labia/first-degree tears (3%).

Risk of sexual health problems and dyspareunia

The proportion of pre-pregnancy dyspareunia was 14%, 21% and 24% in the no/labia/first-degree, second-degree and third-degree/fourth-degree tear groups, respectively (table 1). At 12 months postpartum, the proportion in all three groups was higher than pre-pregnancy, 25%, 38% and 53%, respectively.

The risks for dyspareunia at 12 months postpartum are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Relative risks (RRs) for dyspareunia 12 months postpartum among primiparous women in Denmark (n=554)

| Total n=554 |

Dyspareunia | Crude | |||||

| Yes n=211 |

No n=343 |

RR | (95% CI) | Adjusted* RR |

(95% CI) | ||

| n | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Degree of tear | |||||||

| No/labia/first | 191 | 47 (24.6) | 144 (75.4) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| Second (spontanous) | 157 | 59 (37.8) | 97 (62.2) | 1.53 | (1.11 to 2.10) | 2.05 | (1.51 to 2.78) |

| Second (mediolateral episiotomy) | 32 | 13 (40.6) | 19 (59.4) | 1.65 | (1.01 to 2.69) | 1.62 | (0.99 to 2.67) |

| Third or fourth | 174 | 92 (52.9) | 82 (47.1) | 2.15 | (1.62 to 2.86) | 2.09 | (1.55 to 2.81) |

| BMI, pre-pregnancy (kg/m2)†, mean (SD) | |||||||

| <25 | 357 | 140 (39.2) | 217 (60.8) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| 25–29.9 | 126 | 50 (39.7) | 76 (60.3) | 1.01 | (0.79 to 1.30) | 1.05 | (0.82 to 1.36) |

| >29.9 | 70 | 21 (30.0) | 49 (70.0) | 0.77 | (0.52 to 1.12) | 0.82 | (0.56 to 1.19) |

| Age at inclusion (years), mean (SD) | |||||||

| ≤25 | 141 | 52 (36.9) | 89 (63.1) | 0.94 | (0.72 to 1.22) | 0.94 | (0.72 to 1.22) |

| 26–30 | 278 | 109 (39.2) | 169 (60.8) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| >30 | 135 | 50 (37.0) | 85 (63.0) | 0.94 | (0.73 to 1.23) | 0.91 | (0.70 to 1.19) |

| Active birth duration (min), mean (SD) | |||||||

| <220 | 140 | 49 (35.0) | 91 (65.0) | 0.97 | (0.71 to 1.33) | 0.90 | (0.66 to 1.24) |

| 221–340 | 141 | 51 (36.2) | 90 (63.8) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| 341–570 | 143 | 52 (36.4) | 91 (63.6) | 1.00 | (0.74 to 1.37) | 1.00 | (0.74 to 1.37) |

| >570 | 130 | 59 (45.4) | 71 (54.6) | 1.26 | (0.94 to 1.68) | 1.26 | (0.92 to 1.70) |

| Second stage duration (min), mean (SD) | |||||||

| <16 | 109 | 34 (31.2) | 75 (68.8) | 0.82 | (0.59 to 1.15) | 0.80 | (0.57 to 1.12) |

| 16–30 | 187 | 71 (38.0) | 116 (62.0) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| 31–45 | 89 | 29 (32.6) | 60 (67.4) | 0.86 | (0.60 to 1.22) | 0.86 | (0.61 to 1.23) |

| >45 | 169 | 77 (45.6) | 92 (54.4) | 1.20 | (0.94 to 1.54) | 1.15 | (0.88 to 1.52) |

| Birth weight (g), mean (SD) | |||||||

| <2999 | 76 | 31 (40.8) | 45 (59.2) | 1.05 | (0.76 to 1.45) | 1.09 | (0.79 to 1.51) |

| 3000–3499 | 193 | 75 (38.9) | 118 (61.1) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| 3500–3999 | 210 | 82 (39.1) | 128 (60.9) | 1.01 | (0.79 to 1.28) | 0.96 | (0.75 to 1.22) |

| ≥4000 | 75 | 23 (30.7) | 52 (69.3) | 0.79 | (0.54 to 1.16) | 0.74 | (0.50 to 1.10) |

| Pre-pregnancy dyspareunia (yes) | 107 | 66 (31.3) | 41 (12.0) | 1.90 | (1.56 to 2.32) | 1.79 | (1.45 to 2.21) |

| Operative delivery (yes) | 65 | 45 (47.4) | 50 (52.6) | 1.31 | (1.03 to 1.67) | 1.18 | (0.90 to 1.54) |

| Smoker at inclusion (yes)† | 21 | 10 (47.6) | 11 (52.4) | 1.27 | (0.80 to 2.01) | 1.31 | (0.82 to 2.10) |

| Diabetes (yes) | 19 | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | 0.97 | (0.53 to 1.76) | 1.02 | (0.56 to 1.88) |

*One missing value (n=553).

†Adjusted for age, BMI, birth weight, second stage duration, active birth duration, smoking, diabetes, operative delivery and pre-pregnancy dyspareunia (second stage duration and active birth duration are not mutually adjusted for each other).

BMI, body mass index.

Compared with women with no/labia/first-degree tears, women with third-degree/fourth-degree tears had a higher risk of dyspareunia (adjusted RR (aRR) 2.09; 95% CI 1.55 to 2.81), as did women with spontaneous second-degree tears (aRR 2.05; 95% CI 1.51 to 2.78). Further, we found pre-pregnancy dyspareunia to be associated with postpartum dyspareunia (aRR 1.79; 95% CI 1.45 to 2.21).

At 12 months postpartum, the mean PISQ-12 score was higher among women with third-degree/fourth-degree tears (12.2) than among women with no/labia/first-degree tears (10.4) (table 3).

Table 3.

Risk for sexual health problems 12 months postpartum among primiparous women in Denmark (n=541)

| PISQ-12 score* | ||||||

| Total | Crude | Adjusted† | ||||

| n=541 | Coef. | (95% CI) | Coef. | (95% CI) | ||

| n | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Degree of tear | ||||||

| No/labia/first | 188 | 10.4 (4.2) | 0 | reference | 0 | reference |

| Second (spontaneous) | 153 | 10.7 (5.1) | 0.37 | (−0.65 to 1.38) | 0.21 | (−0.81 to 1.22) |

| Second (mediolateral episiotomy) | 31 | 11.2 (4.2) | 0.81 | (−0.95 to 2.56) | 0.67 | (−1.13 to 2.46) |

| Third or fourth | 169 | 12.1 (5.0) | 1.80 | (0.81 to 2.78) | 1.69 | (0.61 to 2.76) |

| BMI (kg/m2)‡, mean (SD) | ||||||

| <25 | 349 | 11.2 (4.7) | 0 | reference | 0 | reference |

| 25–29.9 | 121 | 10.8 (4.8) | −0.44 | (−1.43 to 0.56) | −0.23 | (−1.22 to 0.76) |

| >29.9 | 70 | 10.6 (5.4) | −0.60 | (−1.83 to 0.64) | −0.51 | (−1.74 to 0.72) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | ||||||

| ≤25 | 137 | 11.2 (5.1) | 0.45 | (−0.53 to 1.44) | 0.49 | (−0.49 to 1.47) |

| 26–30 | 270 | 10.8 (4.7) | 0 | reference | 0 | reference |

| >30 | 134 | 11.5 (4.6) | 0.67 | (−0.32 to 1.67) | 0.61 | (−0.37 to 1.59) |

| Active birth duration (min), mean (SD) | ||||||

| <220 | 137 | 10.9 (4.5) | −0.22 | (−1.35 to 0.91) | −0.24 | (−1.27 to 0.79) |

| 221–340 | 139 | 11.1 (5.5) | 0 | reference | 0 | reference |

| 341–570 | 140 | 10.7 (4.4) | −0.46 | (−1.58 to 0.67) | 0.55 | (−0.57 to 0.47) |

| >570 | 125 | 11.6 (4.7) | 0.51 | (−0.65 to 1.67) | 0.09 | (−1.01 to 1.19) |

| Second stage duration (min), mean (SD) | ||||||

| <16 | 109 | 10.9 (5.0) | −0.22 | (−1.36 to 0.92) | 0.30 | (−1.44 to 0.84) |

| 16–30 | 181 | 11.1 (4.9) | 0 | reference | 0 | reference |

| 31–45 | 87 | 10.5 (4.4) | −0.60 | (−1.83 to 0.62) | −0.76 | (−1.98 to 0.46) |

| >45 | 164 | 11.5 (4.8) | 0.37 | (−0.64 to 1.39) | 0.05 | (−1.00 to 1.11) |

| Birth weight (g), mean (SD) | ||||||

| <2999 | 75 | 12.3 (4.9) | 1.13 | (−0.14 to 2.41) | 0.99 | (−0.27 to 2.27) |

| 3000–3499 | 191 | 11.2 (4.6) | 0 | reference | 0 | reference |

| 3500–3999 | 205 | 10.5 (4.8) | −0.66 | (−1.60 to 0.28) | −0.73 | (−1.68 to 0.21) |

| ≥4000 | 70 | 11.2 (5.1) | 0.08 | (−1.23 to 1.38) | 0.20 | (−1.10 to 1.51) |

| Pre-pregnancy dyspareunia (yes) | 104 | 13.0 (4.6) | 2.44 | (1.43 to 3.44) | 2.45 | (1.44 to 3.46) |

| Operative delivery (yes) | 92 | 11.7 (4.7) | 0.69 | (−0.38 to 1.76) | 0.46 | (−0.72 to 1.63) |

| Smoker at inclusion (yes)‡ | 21 | 13.8 (4.9) | 2.78 | (0.70 to 4.86) | 2.99 | (0.93 to 5.06) |

| Diabetes (yes) | 19 | 11.1 (4.9) | 0.00 | (−2.19 to 2.20) | −0.09 | (−2.27 to 2.09) |

*PISQ-12 score, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire, ranges 0–48, a higher score indicating a higher degree of sexual health problems; n=13 not included in analyses because of >2 missing answers in the questionnaire.

†Adjusted for age, BMI, birth weight, duration of the second stage of labour, duration of active birth, pre-pregnancy dyspareunia, smoking, diabetes and operative delivery (second stage duration and active birth duration are not mutually adjusted for each other).

‡One missing value (n=540).

BMI, body mass index; Coef., coefficient.

After adjustment, women with anal sphincter tears had 1.69 points higher score (95% CI 0.61 to 2.76) compared with women with no/labia/first-degree tears. Women reporting pre-pregnancy dyspareunia had an average 2.45-point higher score (95% CI 1.44 to 3.46) compared with women without pre-pregnancy dyspareunia. Further, we found smoking women to have a higher PISQ-12 score compared with non-smoking women (adjusted β 2.99; 95% CI 0.93 to 5.06).

The RRs for dyspareunia postpartum according to perineal body length are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Risk for dyspareunia according to perineal body length 12 months postpartum among primiparous women in Denmark (n=481)

| Total n=481 |

Dyspareunia | Crude | Adjusted* | ||||

| Yes | No | ||||||

| n=182 | n=285 | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | ||

| n | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Perineal body length (cm) | |||||||

| >2 | 468 | 182 (38.9) | 286 (61.1) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| ≤2 | 13 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.58 | (1.02 to 2.47) | 1.72 | (1.10 to 2.71) |

*Adjusted for age, BMI, birth weight, second stage duration, active birth duration, smoking, diabetes, operative delivery, pre-pregnancy dyspareunia and degree of tear.

BMI, body mass index; RR, relative risk.

We found women with a perineal body length ≤2 cm to be at a higher risk of dyspareunia compared with women with a perineal body length >2 cm (aRR 1.72; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.71).

Discussion

Main findings

At 12 months postpartum, more than half of the women who sustained anal sphincter tears had dyspareunia compared with one-fourth in women with no/labia/first-degree tears. Women with anal sphincter tears had a higher degree of sexual health problems in general. In addition, we found women with perineal body length ≤2 cm to be at a higher risk of dyspareunia.

Interpretation (in light of other evidence)

The literature on sexual function measured more than 6 months postpartum is in general sparse which makes it difficult to compare our results to those from other studies. Our study showed that primiparous women, regardless of degree of tear, experienced high levels of sexual health problems postpartum in accordance with the findings from another large cohort study.3 In line with other studies,3 5 19 we found more women with second-degree tears to have dyspareunia compared with women with no or minor tears. The same studies found pre-pregnancy dyspareunia to be associated with postpartum dyspareunia.3 5 19 We observed the same association, but the association between degree of perineal tear and postpartum dyspareunia did not seem to be affected by the presence of dyspareunia before pregnancy.

Our study showed smoking women to have a higher PISQ-12 score than the non-smoking women. Studies addressing the association between smoking and female sexual health are few and results are inconsistent.20–23 However, smoking has an anti-oestrogenic effect,24 and low oestrogen levels are related to a higher prevalence of sexual health problems among women.25

There is limited knowledge on dyspareunia postpartum and the role of the pelvic floor muscles.26 To the best of our knowledge, only one study including 177 women has investigated the relationship between the perineal muscles and dyspareunia and found no association.26 We found the perineal length to be associated with the risk of dyspareunia. Thus, more women with a short perineum had dyspareunia.

Strengths and limitations

The study had a high follow-up rate for both the web-based questionnaire and clinical examination.

A major strength of this study is the inclusion of only primiparous women. Hereby, we were able to assess the possible association between the degree of tear and the risk of sexual health problems without the influence of previous deliveries and tears. Further, the inclusion of a control group without perineal muscle tears made it possible to assess the effect of a vaginal delivery itself without tears to the perineal muscles. In addition, all women had a clinical examination 2 weeks postpartum, and thereby, the risk of misclassification according to exposure group was minimised.

A limitation of the present study is the fact that all clinical examinations were performed by the same examiner (DG). To limit differential misclassification, the examiner was blinded of the sexual function status of each participant and aimed to stay blinded to the degree of tear the women in question had sustained.

In the present study, we used the standardised and validated PISQ-12 questionnaire. However, the PISQ-12 questionnaire is developed and validated in populations of heterogeneous couples. The questions addressing partner erection and premature ejaculation are only relevant to women with a male partner. As the total PISQ-12 score depended on at least 10 answered questions, some women were excluded from these analyses based on their partner relationship. Thus, some of our results may only be relevant to heterosexual couples. The PISQ-12 score has a biophysical focus in general and lacks the relational and psychological issues that may have an impact on postpartum sexual health. Thus, this study does not address these issues, which are highly relevant in the context of sexual health in a vulnerable period of life.

Other studies have found an association between sexual health problems and breastfeeding, as breastfeeding might fulfil parts of a woman’s need for proximity and lead to decreased oestrogen levels causing vaginal dryness.27–29 We did not have information on breastfeeding. Yet, we have no reason to believe that breastfeeding should be unevenly distributed across degrees of perineal tears. In accordance with the results from a large Irish cohort study, we did not find episiotomies to be associated with sexual health problems 12 months postpartum.19 In our primary-adjusted analyses, we included episiotomy to adjust for any potential confounding effect. Excluding episiotomy from the analyses only changed the adjusted estimates marginally, and thus, episiotomy did not seem to be a confounder in this study.

We found 19.3% to report pre-pregnancy dyspareunia. However, pre-pregnancy information was obtained 2 weeks postpartum, which might have affected the precision of the recall. Ideally, sexual function should have been established before pregnancy but this would require another study design.

Clinical implications

Although sexual problems are common 1 year after childbirth, especially among women sustaining tears of second-degree, third-degree or fourth-degree, the proportion of women who ask for help or discuss their problems is low.5 30 Thus, it is important to give words to the sexual well-being in the postpartum assessment of women and to put a particular focus on the women at high risk of developing sexual health problems. Further, pregnancy is a time in women’s life when they are in contact with health services. This provides an opportunity to identify and counsel women with dyspareunia as they are at risk of persistent sexual health problems 12 months postpartum.

If dyspareunia seems to be caused by vaginal dryness, local vaginal oestrogen or lubricants should be provided. If tender scar tissue is identified, perineal massage or use of lignocaine gel may be helpful,31 and thus, new mothers should be given these advices.

Conclusion

The findings from this cohort study of primiparous women demonstrate that impairment of sexual health is common among primiparous women after vaginal delivery. Women delivering with no tears, tears isolated to the labia or small tears of first-degree reported the best outcomes overall, while more than half of the women with anal sphincter tears were experiencing dyspareunia. It is, therefore, important to minimise the extent of perineal trauma and to thoroughly counsel women and their partners about sexuality before, during and after pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the design of this study. DG performed the data collection and conducted the analyses. DG, VR, EN and NQ contributed to the interpretation of data. DG drafted the manuscript and all the authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the version to be published.

Funding: The study was funded by the Odense University Hospital Research Foundation; the Region of Southern Denmark; the University of Southern Denmark; the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Odense University Hospital; the A.P. Moeller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science (grant no.13-93) and the Danish Association of Midwives.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee for the Region of Southern Denmark (S-20120213, 14 May 2013) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (ID-2008-58-0035, 14 January 2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bossini L, Fortini V, Casolaro I, et al. [Sexual dysfunctions, psychiatric diseases and quality of life: a review]. Psychiatr Pol 2014;48:715–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lagaert L, Weyers S, Van Kerrebroeck H, et al. Postpartum dyspareunia and sexual functioning: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2017;22:200–6. 10.1080/13625187.2017.1315938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, et al. Postpartum sexual functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: a retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:881–90. discussion 88-90 10.1067/mob.2001.113855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buhling KJ, Schmidt S, Robinson JN, et al. Rate of dyspareunia after delivery in primiparae according to mode of delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;124:42–6. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, et al. Women's sexual health after childbirth. BJOG 2000;107:186–95. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Connolly A, Thorp J, Pahel L. Effects of pregnancy and childbirth on postpartum sexual function: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Urogynecol J 2005;16:263–7. 10.1007/s00192-005-1293-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Serati M, Salvatore S, Siesto G, et al. Female sexual function during pregnancy and after childbirth. J Sex Med 2010;7:2782–90. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rådestad I, Olsson A, Nissen E, et al. Tears in the vagina, perineum, sphincter ani, and rectum and first sexual intercourse after childbirth: a nationwide follow-up. Birth 2008;35:98–106. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDonald EA, Gartland D, Small R, et al. Dyspareunia and childbirth: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2015;122:672–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leeman L, Rogers R, Borders N, et al. The effect of perineal lacerations on pelvic floor function and anatomy at 6 months postpartum in a prospective cohort of nulliparous women. Birth 2016;43:293–302. 10.1111/birt.12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gommesen D, Nohr EA, Drue HC, et al. Obstetric perineal tears: risk factors, wound infection and dehiscence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;300:67–77. 10.1007/s00404-019-05165-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, et al. A short form of the pelvic organ Prolapse/Urinary incontinence sexual questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2003;14:164–8. discussion 68 10.1007/s00192-003-1063-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ducarme G, Hamel J-F, Brun S, et al. Sexual function and postpartum depression 6 months after attempted operative vaginal delivery according to fetal head station: a prospective population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178915 10.1371/journal.pone.0178915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brubaker L, Handa VL, Bradley CS, et al. Sexual function 6 months after first delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:1040–4. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318169cdee [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fernando RJS AH, Freeman RM, Williams AA, et al. The management of third- and Fourth-Degree perineal tears. RCOG Green-top guideline no 29. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:10–17. 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Textor J, Hardt J, Knuppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011;22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Malley D, Higgins A, Begley C, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with sexual health issues in primiparous women at 6 and 12 months postpartum; a longitudinal prospective cohort study (the MAMMI study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:196 10.1186/s12884-018-1838-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi J, Shin DW, Lee S, et al. Dose-Response relationship between cigarette smoking and female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2015;58:302–8. 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.4.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Çayan S, Akbay E, Bozlu M, et al. The prevalence of female sexual dysfunction and potential risk factors that may impair sexual function in Turkish women. Urol Int 2004;72:52–7. 10.1159/000075273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oksuz E, Malhan S. Prevalence and risk factors for female sexual dysfunction in Turkish women. J Urol 2006;175:654–8. discussion 58 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00149-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sidi H, Puteh SEW, Abdullah N, et al. Original RESEARCH—EPIDEMIOLOGY: the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and potential risk factors that may impair sexual function in Malaysian women. J Sex Med 2007;4:311–21. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tziomalos K, Charsoulis F. Endocrine effects of tobacco smoking. Clin Endocrinol 2004;61:664–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dennerstein L, Randolph J, Taffe J, et al. Hormones, mood, sexuality, and the menopausal transition. Fertil Steril 2002;77:42–8. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03001-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tennfjord MK, Hilde G, Stær-Jensen J, et al. Dyspareunia and pelvic floor muscle function before and during pregnancy and after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:1227–35. 10.1007/s00192-014-2373-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. LaMarre AK, Paterson LQ, Gorzalka BB. Breastfeeding and postpartum maternal sexual functioning: a review. Can J Human Sex 2003;12:151. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matthies LM, Wallwiener M, Sohn C, et al. The influence of partnership quality and breastfeeding on postpartum female sexual function. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;299:69–77. 10.1007/s00404-018-4925-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Byrd JE, Hyde JS, DeLamater JD, et al. Sexuality during pregnancy and the year postpartum. J Fam Pract 1998;47:305–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glazener CMA. Sexual function after childbirth: women's experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. BJOG 1997;104:330–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sultan A, Thakar R, Fenner D. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. London, UK: Springer, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.