Abstract

Objective:

To compare the Short Test of Mental Status (STMS) to the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for predicting and detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods:

Participants from the community-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) (November 24, 2010 through May 19, 2012) and an academic referral Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) (March 16, 2015 through September 5, 2018) were analyzed. All participants were evaluated using a standardized neuropsychological battery and a multidisciplinary consensus diagnosis was assigned. The MCSA sample included 313 stable cognitively normal (CN) participants, 72 participants with normal cognition at baseline who developed incident MCI or dementia, 114 participants with prevalent MCI, and 25 participants with dementia. The ADRC included 106 stable CN participants, 8 incident MCI/dementia, 96 prevalent MCI, and 132 dementia.

Results:

There was no significant difference between the two tests in 6 of 7 diagnostic comparisons across academic referral and community populations. The STMS had a better AUC [0.898, 95% CI: (0.865, 0.932)] for differentiating prevalent MCI from CN participants in the MCSA cohort compared to the MoCA [0.848, 95% CI: (0.808, 0.889)], P=.01. Additionally, 53% of our stable cognitively normal participants scored < 26 on the MoCA, with a specificity of 47% for diagnosing prevalent MCI.

Conclusions:

We provide evidence that the STMS performs similarly to the MoCA in a variety of settings and neurodegenerative syndromes. Our results suggest that the current recommended MoCA cutoff may be overly sensitive, consistent with previous studies. We also provide a conversion table for comparing the two cognitive tests.

Background:

Bedside cognitive tests performed by primary care and neurology providers are an important screening tool for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. MCI represents an intermediate clinical stage between stable normal aging and dementia.1 Cognitive tests that incorporate brevity and high sensitivity/specificity are required in primary care clinical practice. Early and accurate detection of cognitive changes are essential for appropriate referral for more detailed neurocognitive testing and specialist evaluation. Early diagnosis and support helps families plan strategies to minimize the impact and burden of dementia,2 and will be of increasing importance as disease modifying therapies become a reality. However, specialist referral systems, as well as participants, can be overburdened if screening tests are overly sensitive or lack specificity for detecting neurodegenerative diseases.

A number of tests are being used in clinics across the world, but few have been validated in community settings.3 Most of the existing tools are biased towards detection of amnestic predominant cognitive impairment, with less emphasis on other cognitive domains frequently involved in frontotemporal lobar degeneration or Lewy body disease.4 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is widely used and can be administered relatively quickly, but MMSE scores are not useful for diagnosing MCI,5,6 and its licensing fee has made this measure less attractive for clinical use.7,8 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was created specifically to improve the diagnosis of MCI and has shown improved sensitivity in head to head studies with the MMSE in a variety of cognitive impairment settings.5,9–11 The proposed cutoff of 26 has been considered too sensitive in some studies, limiting the specificity of an abnormal score.12,13

The Short Test of Mental Status (STMS) was developed and validated as a bedside tool that emphasizes brevity and reasonable sensitivity/specificity.14,15 Our group previously showed STMS was more sensitive and specific in detecting early cognitive deficits than the MMSE.6 In this current study, we aimed to compare the MoCA and the STMS for detection of MCI, AD, and other forms of dementia in both a community and an academic referral center setting. Due to subtest differences we predicted that the MoCA would have better sensitivity/specificity for non-amnestic MCI, DLB, and FTLD compared to the STMS. We also aimed to explore potential sensitivity issues with the currently proposed MoCA cutoff score. Our final objective was to establish a conversion table for the two tests.

Methods:

Study Population

These projects are approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board. Participants for this study were recruited prospectively through the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) and the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) using a standardized protocol.16,17 With the help of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, MCSA participants are randomly selected from a community population of Olmsted County, Minnesota.18–20 Participants from the Mayo Clinic ADRC represent a non-random sample that is geographically and clinically diverse. Each participant was evaluated by an experienced clinician who obtained a history and performed a neurologic examination, which included the STMS (see Tang-Wai, 2003 for detailed breakdown table of the STMS).6 Corroborating information was obtained through family members by a nurse or study coordinator and a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale was documented. Participants completed a MoCA and a comprehensive neuropsychological battery as part of the Uniform Data Set (UDS) designed by the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC).21

Consensus Process:

A consensus meeting was held weekly between study coordinators, physicians, and neuropsychologists to assign a consensus diagnosis of normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (amnestic or non-amnestic), or dementia (along with the suspected cause of dementia). A mild cognitive impairment diagnosis was made if the patient endorsed a cognitive complaint, maintained essentially normal activities of daily living, but had objectively abnormal scores (generally <1.5 standard deviations below the mean) in one or more domains of cognitive testing. An Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia diagnosis was based on previous NIAA criteria.22 Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and frontotemporal lobar dementia (FTLD) diagnoses were based on the most recent consensus criteria.23,24 STMS test scores were factored into the clinician’s diagnostic impression, but these were balanced in our consensus meeting by incorporating information provided by family members, as well as standard neuropsychologic test performance.

Statistical Analysis:

The analysis of the data consisted of three main parts: tables of descriptive statistics, logistic regression models, and equipercentile equating. The tables of descriptive statistics are summarized by diagnosis and computed separately for the MCSA and ADRC samples. Statistics presented are n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables. Logistic regression models were run separately for the MCSA and ADRC samples using the STMS and MoCA to predict diagnosis (i.e. CN vs. MCI). Where a sufficient number of events were present, the models were also adjusted for age, sex, and education. To compare the performance of the STMS and MoCA in differentiating diagnoses, the area under the curve (AUC) for the models was used. The AUCs were compared using jackknife resampling. The traditional P≤.05 was considered as statistically significant. The performance of the MoCA in discriminating diagnoses was further explored by graphically examining the sensitivity and specificity of proposed MoCA cutoffs. A histogram showing MoCA scores of cognitively unimpaired participants was used to explore the potential over sensitivity of the MoCA cutoff of < 26. Finally, to create conversion tables between the STMS and MoCA, equipercentile equating was used. This method allows for conversion of a given percentile score from one test to the score related to the same percentile for the other test. Statistical analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 3.4.1.

RESULTS:

There were 524 community MCSA participants followed for an average of 3.3 years (range=06.7 years) grouped by diagnosis (Table 1). There were 72 participants categorized as incident MCI who were cognitively normal at baseline but converted to MCI at follow-up (1 patient converted from CN to dementia). An additional 342 participants were incorporated from an ADRC setting (Table 1). The ADRC participants were younger (68.9 vs. 83.1 years, P<.001) and had higher education (16.0 vs. 13.0 years, P<.001) than the MCSA participants. Within the stable CN and prevalent MCI subgroups, those in the ADRC had higher baseline STMS and MoCA scores than those in the MCSA (P<.001 for all comparisons). There were no significant differences found between baseline cognitive test scores in the incident MCI or dementia subgroups where there was low statistical power.

Table 1:

MCSA and ADRC Demographics

| MCSA Participants |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable CN n = 313 | Incident MCI n = 72 | Prevalent MCI n = 114 | Dementia n = 25 | |

| Women, n (%) | 159 (51%) | 36 (50%) | 57 (50%) | 13 (52%) |

| Age baseline (y), mean (SD) |

81.7 (5.0) | 84.1 (4.8) | 84.0 (5.2) | 87.1 (4.9) |

| Education (y), mean (SD) |

14.2 (2.9) | 14.2 (2.7) | 13.8 (3.1) | 13.9 (3.0) |

| Baseline STMS, mean (SD) |

34.7 (2.3) | 33.1 (2.5) | 29.8 (3.4) | 23.3 (6.8) |

| Baseline MoCA, mean (SD) |

24.5 (2.5) | 23.0 (2.8) | 20.5 (2.9) | 14.5 (5.6) |

| CDR SUM, mean (SD) |

0.05 (0.2) | 0.19 (0.4) | 1.16 (1.3) | 5.8 (4.0) |

| ADRC Participants | ||||

| Stable CN n = 106 | Incident MCI n = 8 | Prevalent MCI n = 96 | Dementia n = 132 | |

| Women, n (%) | 50 (47%) | 3 (38%) | 24 (25%) | 60 (46%) |

| Age baseline (y), mean (SD) |

63.1 (12.9) | 71.1 (8.5) | 70.3 (8.5) | 69.3 (11.0) |

| Education (y), mean (SD)a |

15.9 (2.4) | 14.1 (1.7) | 16.3 (3.0) | 15.3 (2.8) |

| Baseline STMS, mean (SD) |

36.8 (1.4) | 34.1 (2.9) | 33.3 (3.2) | 24.2 (7.7) |

| Baseline MoCA, mean (SD) |

27.1 (2.1) | 24.5 (3.2) | 22.6 (3.3) | 14.0 (5.9) |

| CDR SUMb, mean (SD)a |

0.04 (0.2) | 0.13 (0.4) | 1.40 (1.1) | 5.0 (2.9) |

Four observations are missing for CDR SUM in the MCSA and three observations are missing for Education in the ADRC.

CDR SUM = Clinical Dementia Rating - Sum of boxes.

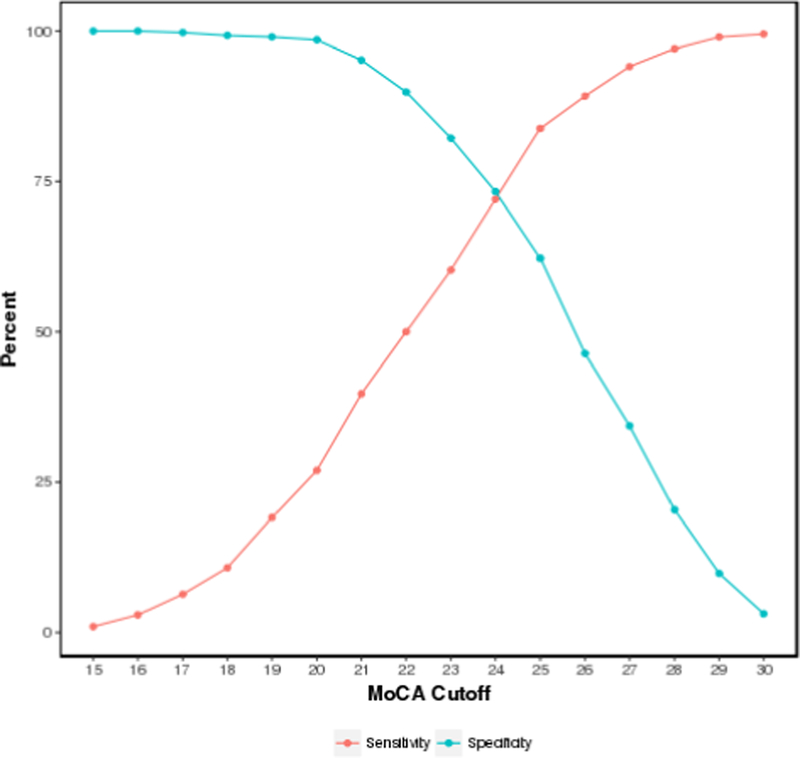

Table 2 summarizes performance between the MoCA and STMS across both populations and patient subgroups. There were no statistically significant differences between the diagnostic accuracy of the MoCA and the STMS on 6 of 7 contrasts. In the MCSA community population, the STMS was better than the MoCA at differentiating prevalent MCI from CN, AUC 0.90 [95% CI: (0.87, 0.93)] and 0.85 [95% CI: (0.81, 0.89)], respectively (P=.01, not corrected for multiple comparisons) (Figure 1). When comparing CN to the incident MCI group within the MCSA, both the STMS and the MoCA performed well with ROC curves providing AUC values of 0.71 [95% CI: (0.65, 0.77)] and 0.70 [95% CI: (0.64, 0.77)], respectively.

Table 2:

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for STMS and MoCA Across Diagnostic Groups

| AUC STMS (95% CI) | AUC MoCA (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCSA CN vs. Prevalent MCI | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) | 0.85 (0.83–0.89) | .01 |

| MCSA CN vs. Incident MCI | 0.71 (0.65–0.77) | 0.70 (0.64–0.77) | .83 |

| MCSA CN vs. Dementiaa | 0.97 (0.94–1.0) | 0.97 (0.94–1.0) | .52 |

| MCSA MCI vs. Dementiaa | 0.81 (0.70–0.91) | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | .74 |

| ADRC CN vs. Prevalent MCI | 0.87 (0.83–0.92) | 0.90 (0.85–0.94) | .29 |

| ADRC CN vs. Dementia | 0.99 (0.98–1.0) | 0.99 (0.99–1.0) | .10 |

| ADRC MCI vs. Dementia | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) | .11 |

Due to minimal event frequency MCSA CN vs. Dementia and MCSA MCI vs. Dementia comparison models were not adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for differentiating prevalent mild cognitive impairment from cognitively normal participants of STMS vs. MoCA in the community cohort MCSA. AUC was 0.90 [95% CI: (0.87, 0.93)] vs. 0.85 [95% CI: (0.81, 0.89)], respectively (P=.01, not corrected for multiple comparisons).

AUC = area under curve; MCSA = Mayo Clinic Study of Aging; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; STMS = Short Test of Mental Status.

Additional subgroups were analyzed to investigate if subtype of MCI or dementia syndrome performed better with either cognitive test. In the MCSA sample, 114 participants in the prevalent MCI group were further classified into amnestic MCI (n = 89) or non-amnestic MCI (n = 25) described in Supplemental Table 1. Within the ADRC dementia group, there were 92 participants with AD, 26 with DLB, and 14 with FTLD, further described in Supplemental Table 2. In the MCSA cohort, the STMS provided better discrimination between amnestic MCI and CN when compared to the MoCA (AUCs 0.90 [95% CI: (0.86, 0.94)] and 0.85 [95% CI: (0.81, 0.90)] respectively, P=.04). When comparing non-amnestic MCI to CN, the AUC for the STMS was 0.91 [95% CI: (0.87, 0.95)] compared to 0.84 [95% CI: (0.75, 0.92)] for the MoCA (P=.07). There was no statistical significance between the two cognitive tests in differentiating CN from FTLD and DLB in the ADRC subgroups, likely due to low statistical power in the FTLD and DLB subgroups. Of note, the MoCA had a statistically significant AUC compared to the STMS when comparing CN to AD, but lacks clinical significance (AUC 1.0 [95% CI: (0.99, 1.0)] vs. 0.99 [95% CI: (0.98, 1.0)], P=.05) shown in Supplemental Table 3.

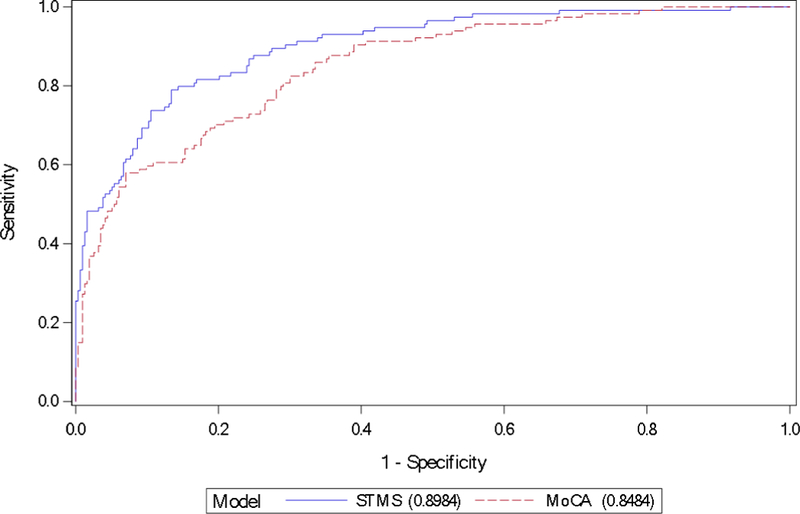

We further analyzed sensitivity and specificity cutoffs for each test by combining both patient populations (n = 866), which provided a wider range of scores. When combining both patient cohorts, a cutoff of < 26 for the MoCA provided a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 47% for diagnosing prevalent MCI. Figure 2 shows a cutoff score of < 24 (STMS equivalent < 35) provided a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 74%. Out of the 419 stable cognitively normal participants in our cohorts, there were 53% who scored below the currently used normal cutoff of < 26 (Supplemental Figure 1A). In the MCSA cohort, a cutoff of < 26 for the MoCA provided a sensitivity of 96% but specificity of 36%, and a cutoff score of 23 (STMS equivalent <34) provided a sensitivity of 69% and a specificity of 78% (Supplemental Figure 1B). Additionally, a MoCA cutoff score < 20 (STMS equivalent < 30) provided a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 72% for differentiating prevalent MCI and all cause dementia across both cohorts (Supplemental Figure 1C).

Figure 2.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment sensitivity/specificity plot for detecting prevalent MCI. A cutoff score of 24 provides a sensitivity of 72% and a specificity of 74% in detecting prevalent MCI.

MCI = mild cognitive impairment

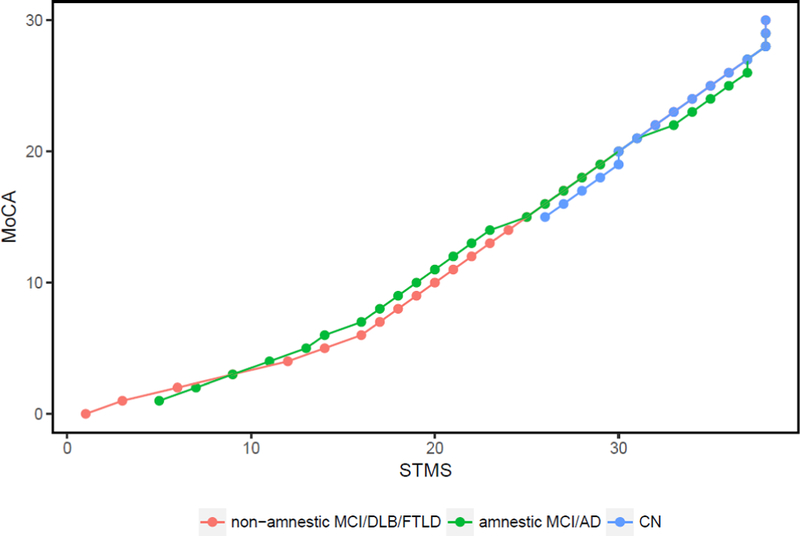

We performed equipercentile equating conversions between the STMS and MoCA in the combined population samples (Table 3). To analyze if the subtype of cognitive syndrome influenced the reliability of conversion between the two cognitive tests, we combined nonamnestic subgroups (non-amnestic MCI, DLB, FTLD) and plotted them against amnestic subgroups (amnestic MCI, AD). Figure 3 shows good correlation between the subgroups across the range of scores.

Table 3:

Test Conversions Using Equipercentile Equatinga

| Converting STMS to MoCA | Converting MoCA to STMS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STMS | MoCA | MoCA | STMS |

| 38 | 29 | 30 | 38 |

| 37 | 27 | 29 | 38 |

| 36 | 26 | 28 | 38 |

| 35 | 24 | 27 | 37 |

| 34 | 23 | 26 | 36 |

| 33 | 22 | 25 | 36 |

| 32 | 22 | 24 | 35 |

| 31 | 21 | 23 | 34 |

| 30 | 20 | 22 | 33 |

| 29 | 19 | 21 | 31 |

| 28 | 18 | 20 | 30 |

| 27 | 17 | 19 | 29 |

| 26 | 16 | 18 | 28 |

| 25 | 16 | 17 | 27 |

| 24 | 15 | 16 | 26 |

| 23 | 14 | 15 | 24 |

| 22 | 13 | 14 | 23 |

| 21 | 12 | 13 | 22 |

| 20 | 11 | 12 | 21 |

Combined MCSA and ADRC cohort, n = 866

Figure 3.

Equipercentile equating plot converting STMS to MoCA scores compared across cognitive subgroups: non-amnestic (non-amnestic MCI, DLB, FTLD) in red, amnestic (amnestic MCI and AD) in green, and CN in blue.

AD = Alzheimer’s disease; CN = cognitively normal; DLB = dementia with Lewy Bodies; FTLD = frontotemporal lobar dementia; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; STMS = Short Test of Mental Status

Discussion:

The MoCA has shown superiority over the MMSE in detecting MCI in numerous studies.5,9–11 The present study is the first to directly compare the MoCA to the STMS. In both patient populations, the STMS and MoCA performed well in detecting MCI and the three most common clinical dementia phenotypes. Both tests were able to predict conversion of CN to MCI with AUCs of 0.71 [95% CI: (0.65, 0.77)] for STMS and 0.70 [95% CI: (0.64, 0.77)] for MoCA.

The recommended abnormal cutoff of <26 for the MoCA has proven to be very sensitive for diagnosing MCI participants.5 This cutoff has been criticized in subsequent studies because of the low specificity of an abnormal value, particularly for community-based populations.13,25–29 Most community-based studies have suggested a lower abnormal cutoff range of 20–24 to maintain adequate sensitivity, but also yield better specificity. Of the stable cognitively normal participants across our cohorts, 53% scored lower than the current recommended cutoff of 26. This offers further evidence that the recommended cutoff is too sensitive.

Over-diagnosis can burden patients and families with diagnostic anxiety while simultaneously burdening referral specialists with cognitively normal patients. A MoCA score of < 24 gave a better balance of sensitivity/specificity amongst the combined patient cohorts in this study. A comparative cutoff score for the STMS was determined to be < 35 based on equipercentile equating. Detailed neuropsychological tests utilize norms that are adjusted for patient demographics and one cutoff score may not be applicable for all situations. To better adjust the MoCA for education, it has been suggested that 1 point be added for a patient with <12 years of education. Our population had a mean education of 14.7 years and this point addition would not apply to the majority of our participants. Additional z-scores that are both age- and education-corrected may help interpret patient scores to assist in determining level of concern for prompting a specialty referral.

A previous study suggested that the MoCA trended toward improved accuracy in dysexecutive subgroups (DLB, FTLD, vascular subtypes) compared to the MMSE.30 The MoCA also incorporates more items for assessing aspects of executive function than the STMS, and we expected the MoCA would have better sensitivity/specificity for non-amnestic MCI, DLB, and FTLD compared to the STMS. Each subgroup had small numbers individually, but combining the non-amnestic subgroups (n = 83) and amnestic subgroups (n =259) did not favor the MoCA statistically.

There are limitations to the generalizability of our study as participants from both cohorts were native English speakers, were well-educated and largely European-American, and so our findings may not apply to less educated or populations of diverse race and native language.29 A potential circularity bias exists in that neurologists had access to STMS and MoCA scores at the time of determining the baseline diagnosis. This bias was partially mitigated by not relying on one factor for diagnosis amongst the consensus committee. The stable CN group and the incident MCI group were isolated from this baseline diagnosis bias as their follow up visit diagnoses were used for classification independent of the baseline scores.

Conclusion:

Primary care physicians need sensitive bedside tests to detect MCI, but the cutoff scores utilized must also be specific enough to not overburden patients and a specialist system with cognitively normal patients. Our data suggests that the current MoCA cutoff may be overly sensitive. We also provided evidence that the STMS performs as well as the MoCA in a variety of settings and neurodegenerative syndromes, and was better at differentiating CN from MCI in a community-based setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support and conflict of interest disclosure: This work was supported by NIH grants P50 AG16574, U01 AG06786 and by the Abigail van Buren Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program. Sponsors did not have any role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. Walter Kremers receives research funding from the NIH, DOD, AstraZeneca, Biogen and Roche. David Knopman serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for the DIAN study; is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Biogen, Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the University of Southern California; and receives research support from the NIH. Julie Fields receives funding from the NIH. Brad Boeve has served as an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by GE Healthcare and Axovant. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology Of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009, 2017). He serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Tau Consortium. He receives research support from NIH, the Mayo Clinic Dorothy and Harry T. Mangurian Jr. Lewy Body Dementia Program and the Little Family Foundation.

Abbreviations and acronyms:

- STMS

(short test of mental status)

- MoCA

(Montreal Cognitive Assessment)

- MMSE

(Mini-Mental Status Exam)

- MCI

(mild cognitive impairment)

- AD

(Alzheimer’s disease)

- ADRC

(Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center)

- FTLD

(Frontotemporal Lobar Dementia)

- DLB

(Lewy Body Dementia)

- CN

(cognitively normal)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gauthier S et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 367, 1262–1270, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunn F et al. Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Med 9, e1001331, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001331 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, Coen RF & Lawlor BA A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78, 790–799, doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.095414 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royall D The “Alzheimerization” of dementia research. J Am Geriatr Soc 51, 277–278 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasreddine ZS et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53, 695–699, doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang-Wai DF et al. Comparison of the short test of mental status and the mini-mental state examination in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 60, 1777–1781, doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1777 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin R & O’Neill D Taxing your memory. Lancet 373, 2009–2010, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60349-4 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman JC & Feldman R Copyright and open access at the bedside. N Engl J Med 365, 2447–2449, doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110652 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markwick A, Zamboni G & de Jager CA Profiles of cognitive subtest impairment in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a research cohort with normal Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 34, 750–757, doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.672966 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Y et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of vascular cognitive impairment after acute stroke. J Neurol Sci 299, 15–18, doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.051 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoops S et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 73, 1738–1745, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34b47 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larner AJ Screening utility of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): in place of--or as well as--the MMSE? Int Psychogeriatr 24, 391–396, doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001839 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldron-Perrine B & Axelrod BN Determining an appropriate cutting score for indication of impairment on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 27, 1189–1194, doi: 10.1002/gps.3768 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokmen E, Naessens JM & Offord KP A short test of mental status: description and preliminary results. Mayo Clin Proc 62, 281–288 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokmen E, Smith GE, Petersen RC, Tangalos E & Ivnik RC The short test of mental status. Correlations with standardized psychometric testing. Arch Neurol 48, 725–728 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen RC, Kokmen E, Tangalos E, Ivnik RJ & Kurland LT Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Registry. Aging (Milano) 2, 408–415 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen RC, Smith G, Kokmen E, Ivnik RJ & Tangalos EG Memory function in normal aging. Neurology 42, 396–401 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts RO et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology 30, 58–69, doi: 10.1159/000115751 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St Sauver JL et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. International journal of epidemiology 41, 1614–1624 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, Sauver JLS, Grossardt BR & Melton LJ in Mayo Clinic proceedings 1202–1213 (Elsevier; ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monsell SE et al. Results From the NACC Uniform Data Set Neuropsychological Battery Crosswalk Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 30, 134–139, doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000111 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKhann GM et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269, doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKeith IG et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 89, 88–100, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rascovsky K et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134, 2456–2477, doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malek-Ahmadi M et al. Age- and education-adjusted normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in older adults age 70–99. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 22, 755–761, doi: 10.1080/13825585.2015.1041449 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damian AM et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the mini-mental state examination as screening instruments for cognitive impairment: item analyses and threshold scores. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 31, 126–131, doi: 10.1159/000323867 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freitas S, Simoes MR, Alves L & Santana I Montreal cognitive assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 27, 37–43, doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bfe (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luis CA, Keegan AP & Mullan M Cross validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in community dwelling older adults residing in the Southeastern US. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24, 197–201, doi: 10.1002/gps.2101 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Cullum CM & Weiner MF Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology 77, 1272–1275, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230208a (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergeron D et al. Multicenter Validation of an MMSE-MoCA Conversion Table. J Am Geriatr Soc 65, 1067–1072, doi: 10.1111/jgs.14779 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.