Abstract

Background:

Oklahoma’s Advance Directive completion rate is less than 10%. We compared the implementation performance of 2 advance directive forms to determine which form could be more successfully disseminated.

Methods:

The implementation of the Oklahoma Advance Directive (OKAD) and the Five Wishes form were compared in an 8-month pair-matched cluster randomized study in 6 primary care practices. The outcomes measured during the 22-week implementation included form offering rate, acceptance/completion rate by patients, and documentation in the chart. Twenty semistructured interviews with patients and clinicians were conducted to assess intervention experience.

Results:

A total of 2748 patient encounters were evaluated. OKAD was offered in 33% of eligible patient visits (493/1494) and accepted 54% of the time (266/493). Five Wishes was offered in 36% of eligible patient visits (450/1254) and accepted 82% of the time (369/450). Unadjusted analyses found no significant difference in offering of advance directive forms between groups. However, the odds of accepting Five Wishes were 3.89 times that of OKAD (95% CI, 2.88 to 5.24; P < .0001). Logistic regression models controlling for several confounders indicated that the acceptance of Five Wishes was favored significantly over OKAD (OR = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.81; P < .0001). Qualitative analyses indicated a clear clinician and patient preference for Five Wishes.

Conclusions:

Results suggest that Five Wishes was more readable, understandable, appealing, and usable. It seemed to capture patient preferences for end-of-life care more effectively and it more readily facilitated patient-clinician conversations.

Keywords: Advance Directives, End of Life Care, Living Wills, Oklahoma, Patient Preference, Patient-Centered Care, Primary Health Care, Quality of Life

In 2014, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a report about the current state of medical care for persons with serious/terminal illnesses in the United States.1 The resulting report noted that the process of dying in the United States has dramatically changed as a result of fragmentation of medical care and barriers to access. In addition to these challenges, people are living longer and are frailer overall. This report identified several opportunities to improve on these issues including increasing clinician-patient communication and advance care planning (ACP).

An important part of ACP is the completion of an Advance Directive (AD). ADs specifically address one’s ability to legally express one’s desires regarding end-of-life (EOL) care.2 In Oklahoma, ADs are frequently unutilized until the patient’s terminal care period, if then. Pilot data from our medical center inpatient palliative care consult team indicate an AD completion rate of 5% to 12%.3 A recent informal survey of the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) members indicated AD completion rates between 0% to 12%, averaging 5% to 7% in primary care.4 These completion rates clearly demonstrate the need for improved AD implementation strategies.

ACP conversations occur infrequently and if they occur, they generally take place when someone is gravely ill. This adds to the burden on the individual and family, decreasing the likelihood of decisions that are best aligned with the individual’s goals for EOL care. As a result, many people die in a medical setting such as an intensive care unit. In contrast, most people report that ideally, their death would occur at home, surrounded by friends and family, free of pain.5 Without a completed AD there is a high probability that a person will die in the hospital, particularly the intensive care unit.2 In previous studies, the lack of user-friendly features has been identified as a barrier to successful AD adoption6 and given the fact that over a third of US adults have low health literacy, there is room for improvement in strategies for better AD implementation.7

Feedback from practitioners and our preliminary research indicate that a widely used alternative, the Five Wishes document,8 may be more useful and appropriate for most patients than the current Oklahoma Advance Directive for Health Care (OKAD) form.9 The OKAD is a 4-page document written at a 15.5-grade reading level. There is a 20-page explanatory booklet available to assist with understanding for potential completers. It is available in 3 languages, containing highly technical and legal language and using complicated and sometimes poorly-defined medical terminology. In contrast, Five Wishes has an eighth-grade reading level,9 has been translated into 28 languages, and is legally accepted in 42 states, including Oklahoma. There are various options for people (web instructions, videos) to assist people with understanding the options presented by the form. The implementation and clinical performance of Five Wishes has not yet been compared with any state-sponsored form. This is particularly important when we consider that the average readability level of state-sponsored AD forms is grade 11.9, whereas the average reading level of adults in Oklahoma is far below this.7

This article describes a pilot study comparing the uptake of OKAD to that of Five Wishes. Our goal is to identify which form would be more acceptable to Oklahomans and to discover factors that influence AD implementation in general. This information will be used to develop a future larger randomized controlled trial to improve the implementation and dissemination of ADs in Oklahoma.

Methods

Six primary care practices were recruited via the OKPRN listserv (n = 246), enrolled, and pair-matched based on practice size, type, patient mix, and geographical location to minimize differences in known covariates based on methodological standards for cluster-randomized trials.10 Practices were randomly allocated to the 2 study groups (1:1 OKAD vs Five Wishes; see Table 1). The study took place over a 22-week period from January 2017 through May 2017. Participants were blinded to the 2-arm assignment to minimize allocation awareness bias.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Pair-Matched Practices, Based on Clinician Survey Responses

| Pair Match | Practice Type | 2013 Locale Population | Panel Size | Pts/Day | % Medicare | Reg Use of AD Form | % Discuss AD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FQHC | 17,140 | >2000 | 12 | 25 to 49 | N | 0 |

| 1 | Independent | 6,027 | >3000 | >40 | 50 to 74 | N | 1 to 24 |

| 2 | Residency/Corporate | 610,613 | >3000 | 30 to 39 | 25 to 49 | N × 2, Y × 1 | 1 to 24 |

| 2 | Residency | 610,613 | >3000 | 40 | 25 to 74 | Y × 1, N × 4 | 1 to 24 |

| 3 | Independent | 23,400 | >3000 | 10 to 19 | 25 to 49 | N | 0 |

| 3 | Independent | 17,140 | >3000 | 20 to 29 | 50 to 74 | N | 1 to 24 |

2013 Locale Population, based on 2013 data; % Discuss AD: Estimated percent of patients with whom the clinician believes they discuss ADs at baseline; FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center; pts/day, estimated average number of patients seen per day; % Medicare, estimated percent Medicare-insured patients; Reg Use of AD Form, Does the clinician use an AD form on a regular basis? (Y, yes; N, no, ×# indicates how many clinicians gave this answer).

AD, Advance Directive.

Patients 65 years or older with decision-making capacity presenting for nonemergent office visits were eligible for the study and those who accepted a form were considered patient participants. Retrospective chart abstractions examined a 5-year baseline period in a representative, randomly selected sample of medical records from these participants (n = 100). This list was weighted based on the number of patient participants in each practice. Progress notes, reports, and attachments were examined to establish the existence of an AD completed within a 5-year time window. The date and the type of AD (if available) were recorded, along with the age and gender for each patient participant. This subset of 100 charts were reviewed at the end of the study for the number and type of active chronic conditions of patients to calculate a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).11

Sample size estimates indicated that 60 patients in 6 practice clusters (n = 360), based on an inter-class correlation coefficient of 0.0212,13 would provide sufficient power (80%) to detect realistic and clinically meaningful differences in AD adoption rates between the 2 study groups (13% to 17%).

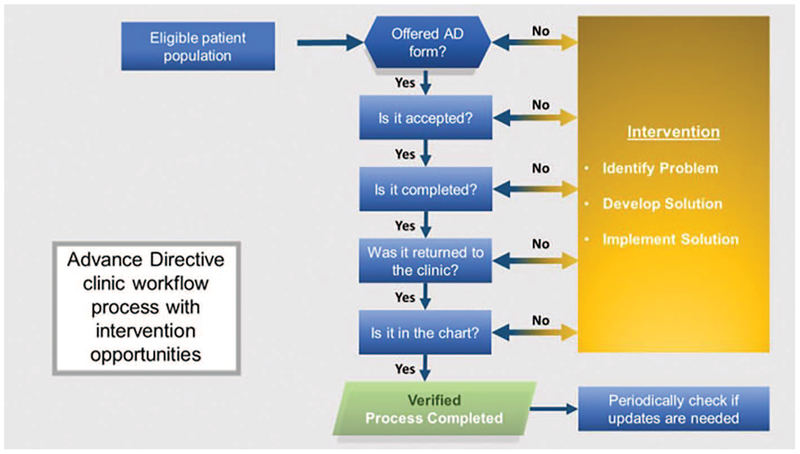

Each participating clinic was instructed to offer their assigned AD form to eligible patients in Spanish, English, or Vietnamese. We asked the clinician’s medical staff to introduce the AD form as they were rooming the patient using a standardized 30-second script, available in all 3 languages. To track the offering and acceptance of the AD forms, medical staff were also asked to keep a log tailored to fit the preferred workflow for each clinic. Two unique identifiers were recorded for each patient as well as information pertaining to 1) offering the AD (or why it was not offered); 2) acceptance of the AD (or why it was not accepted); and 3) comments for each patient, as appropriate. Logs were collected regularly by a practice facilitator (PF) and compared with the daily schedule to identify a daily list of the proportion of eligible patients captured on the log. Practice level participation data were recorded in a Microsoft SharePoint database, Redmond, WA and reviewed by the research team on a weekly basis. Individual-level outcomes were recorded in a REDCap database, Nashville, TN.14 PFs worked with practices to ensure sufficient implementation without deliberately maximizing implementation rates. As necessary, they helped the practices investigate strategies to improve the rate of offering the AD forms. At weekly meetings, the team discussed the challenges each practice faced as well as strategies they used to ensure sufficient implementation in each practice. We documented particularly helpful, high-performing processes for improving implementation for use in a subsequent “best practices” study. We illustrate the details of the workflow process in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow process for the distribution of advance directives in the clinics.

To ensure the accuracy of the denominator, we compared documented patient schedules tracked by the practices to the numbers derived from the 2 databases. We compared proportions of AD offering and acceptance rates between OKAD and Five Wishes groups using χ2 statistics and performed subsequent analyses using logistic regression to model offering and acceptance of AD forms across study groups, controlling for patient age, gender, and CCI. A logistic regression model was fit to compare the odds of acceptance between the OKAD and Five Wishes arms. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs), with adjustment for the small number of practices in the study, were used to account for the impact of practice-level clustering.15,16 Quantitative data analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Qualitative analyses of individual semistructured interviews with participating clinicians and patients were conducted using a directive content analysis method.17 The same subset of 100 charts for the retrospective chart analysis and the CCI calculation served as the preliminary invitee list for the interviews. Patients were eliminated from the list if they did not speak English, did not return our calls after 3 attempts, or reported no recall of the AD form. The remaining patients were asked to participate in 30-minute telephone interviews conducted between 2 weeks and 4 months after the intervention visit to ensure reasonable recall. The patients who agreed to participate in phone interviews were verbally consented before the start of the interview and then consented in writing via a mailed consent form along with the gift card paperwork after the interview, while the clinician participants provided written consent before starting the interview. The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, then coded using NVivo v11 software (QSR International, Burlington, MA) by 2 independent researchers with qualitative analysis experience (EW and MG). Interviews were analyzed and coded iteratively based on a preliminary coding scheme developed previously with areas of disagreement argued to consensus. Our qualitative inquiry was intended to clarify the facilitators and barriers of specific AD implementation and thus, our overarching themes were anticipated by our interview guide. However, we were intentionally open to the emergence of unanticipated findings as well. Patients received a $35 gift card for participation. Clinicians were interviewed at the end of the data collection period and participating practices received a $1000 remuneration. Results were triangulated to meaningfully supplement the quantitative analyses with patient and clinician feedback and practice-based observations from PF field notes.

Results

Quantitative Outcomes

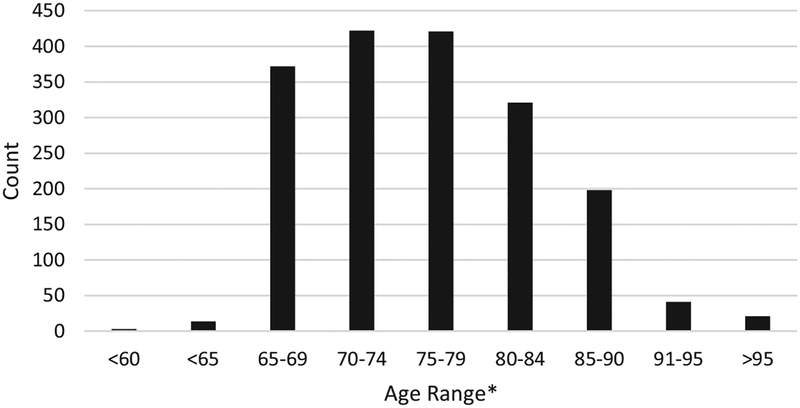

Practice and patient participant characteristics are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The median age of patients was 76 years (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Participating Patient Demographics

| Category | Characteristic | Count | Percentage, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 232 | 35 |

| Female | 440 | 65 | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 337 | 73 |

| Black | 54 | 12 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 31 | 7 | |

| Native American/Alaskan | 7 | 2 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 32 | 7 |

Count is limited to the number of patient participants for whom this information was recorded by the clinical staff.

Figure 2.

Age distribution pf participating patients in the study.

Across 6 practices, 2748 patient encounters were eligible for inclusion in the study during a 22-week implementation period. Of all eligible encounters, AD forms were offered to 34% of patients (n = 943) and accepted 67% of the time when offered (n = 635).

OKAD was offered in 33% of eligible visits (493/1494), while Five Wishes was offered in 36% of eligible visits (450/1254). The acceptance rate of OKAD was 54% (266/493), while the acceptance rate of Five Wishes was 82% (369/450). (Tables 3 and 4). Unadjusted analyses indicated no significant difference in offering rates between study groups (OR = 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.33; P = .11). However, the odds of accepting Five Wishes was 3.89 times greater than that of the OKAD (95% CI 2.88 to 5.24; P < .0001).

Table 3.

Cumulative Utilization Statistics for the Two Forms: OKAD Versus Five Wishes

| Form | Eligible | Offered | Offered/Eligible, % | Accepted | Accepted/Offered, % | Accepted/Eligible, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OKAD | 1494 | 493 | 33 | 266 | 54 | 18 |

| Five Wishes | 1254 | 450 | 36 | 369 | 82 | 29 |

OKAD, Oklahoma Advance Directive.

Table 4.

AD Form Utilization Distribution by Practices

| Form | Practice | Weeks in Study | Eligible | Offered | O/E | Accepted | A/O | A/E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OKAD | 1 | 17 | 816 | 288 | 35% | 147 | 51% | 18% |

| 3* | 17 | 134 | 68 | 51% | 39 | 57% | 29% | |

| 6* | 14 | 544 | 137 | 25% | 80 | 58% | 15% | |

| Five Wishes | 2* | 22 | 413 | 163 | 39% | 93 | 57% | 23% |

| 4 | 15 | 733 | 254 | 35% | 252 | 99% | 34% | |

| 5 | 16 | 108 | 33 | 31% | 24 | 73% | 22% | |

| Total | 2748 | 943 | 34% | 635 | 67% | 23% |

Practices going through electronic health record transition during this study.

A, accepted; AD, Advance Directive; E, eligible; O, offered, OKAD, Oklahoma Advance Directive.

Logistic regression analyses controlling for age, gender, and CCI found no significant difference across study groups for offering AD forms (OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.61 to 1.27; P = .506). However, in a similar model, the acceptance of Five Wishes was favored significantly over OKAD (OR = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.81; P < .0001).

Logistic regression analyses that modeled offering of any AD form as a function of CCI while controlling for patient age and gender indicated that each unit score increase in CCI was associated with a 78% increase in the likelihood of offering an AD form (95% CI, 1.14 to 2.76; P = .04). We found a similar effect when modeling AD form acceptance as the function of CCI (OR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.56; P = .04), indicating that an increase in CCI was associated with a higher likelihood of accepting an AD form.

After adjusting for the correlation among patients within a practice using GEEs, although the odds of acceptance were higher with Five Wishes, the increase was not statistically significant. Among participants who were offered an AD form the odds of accepting Five Wishes were 3.26 times the odds of accepting OKAD (OR = 3.26, 95% CI, 0.13 to 80.56, P = .47).

Qualitative Outcomes

Of the weighted list of 100 study patients, 12 agreed to participate in interviews (5, OKAD; 7, Five Wishes). All clinicians were interviewed (3, Five Wishes; 5, OKAD). Five overarching themes were identified in clinician/patient interviews 1) Capturing Wishes; 2) Reading Level, Language, and Form Design; 3) Family and Cultural Context; 4) Implementation Success/Completing the AD; and 5) Facilitating EOL Discussions. There were 2 additional clinician-specific themes: 1) Care Process Factors; and 2) The Time Factor (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Representative Quotes from Qualitative Interviews with Patients and Clinicians

| Qualitative Themes for Patients and Clinicians | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative Quotes | |||

| Theme | Subtheme | OKAD | Five Wishes |

| Capturing wishes | Clinicians |

|

|

| Patients |

|

|

|

| Reading level, language, and form design | Clinicians |

|

|

| Regarding form design: | |||

| |||

| Regarding form design: | Asked about length: | ||

|

|

||

| Patients |

|

|

|

| Family and cultural context | Clinicians |

|

|

| Patients |

|

|

|

| Patients |

|

||

| Implementation success | Clinicians |

|

|

| Patients |

|

|

|

| Facilitating EOL discussions | Clinicians |

|

|

| Patients |

|

|

|

AD, Advance Directive; EOL, end of life; HCP, healthcare Proxy; OKAD, Oklahoma Advance Directive; RN, registered nurse.

Themes Shared between Patients and Clinicians

Capturing Wishes

Clinicians in the OKAD arm found the form to be generally acceptable with varying opinions about the form’s performance, most of which were neutral. In comparison, Five Wishes received more uniformly positive comments from clinicians regarding its ability to represent the wishes of patients.

OKAD patient responses expressed limited enthusiasm with several patients unable to remember the form specifically and thus were not able to comment about it. Patients receiving Five Wishes stated that the form captured their wishes “quite well” or “very well” and that it gave them the flexibility to express their priorities. They also remembered and mentioned specific parts of the forms they liked, such as Wish Number Five (What I Want My Loved Ones to Know).

Reading Level, Language, and Form Design

OKAD clinician responses in this category were generally tepid with concerns of readability due to the use of medical and legal jargon. As a result, they were worried about whether patients really understood what they were signing, particularly in light of known patient literacy limitations. Clinicians were more positive about Five Wishes’ readability and design.

Most patients initially stated that the OKAD was “easy to read,” but their subsequent responses demonstrated incongruence with this statement. In fact, they expressed considerable difficulty with reading and understanding the OKAD form. This was predominantly related to the form’s complicated and legalistic language. Many patients expressed confusion about the statements they were signing and often needed assistance with the form.

In contrast, no Five Wishes patients demonstrated confusion about the purpose of the form’s sections. They reported that it used simple language and was easy to follow.

Although Five Wishes was much longer than the OKAD (11 pages vs 4 pages), neither clinicians nor patients complained about the length of the form, even when asked directly.

Family and Cultural Context

OKAD clinicians reported concerns with patients choosing health care proxies. This is similar to what was found in the Five Wishes in that several patients wanted more than 1 person to be equally responsible for this section. The OKAD does not clearly indicate the need for prioritization, however, whereas the Five Wishes does. Generally, clinicians felt that Five Wishes had cross-cultural acceptance and allowed differences to be discussed respectfully and sensitively. A clinician commented that Five Wishes was easier for patients to read in Spanish than the OKAD and he felt it translated well. Five Wishes clinicians felt that the conversational nature of the form made it easier for patients to discuss in the office and at home.

Patients expressed the desire for more than 1 person to share proxy decision-making responsibilities and the challenge this presents in families. This was expressed in both arms of the study. Patients in the Five Wishes arm volunteered they would discuss the form at home with their families more than the OKAD form.

Implementation Success

Clinicians in both study arms expressed similar challenges regarding AD implementation success. The OKAD clinicians expressed that the process of this study assisted with the distribution of the forms. The Five Wishes clinicians also expressed this but commented that the form itself was more accessible to patients and better accepted by patients when offered. Both patient groups commented that any clinician conversations about the forms were helpful, although these comments were more frequent in the Five Wishes group. The OKAD seemed more difficult than the Five Wishes for people to complete, based on the clinician observations and the patient statements about the form.

Facilitating EOL Care Discussions

Several clinicians were already comfortable with the introduction of EOL care conversations and felt that the increased focus on AD implementation allowed them to explore this topic. One of the clinicians felt that Five Wishes helped his patients understand their personal responsibility to make EOL decisions.

Patients in both arms of the study noted conversations with medical staff/clinicians were helpful, even though interactions were time limited. Different life events affected patients’ perceptions of the need for an AD, such as their current health status, watching loved ones suffer, and EOL court cases (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Barriers and Facilitators Identified by Clinicians During Qualitative Interviews

| Qualitative Themes for Clinicians | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Common barriers to implementation for both forms |

| Time |

|

| Barriers and facilitators identified |

|

EHR, electronic health record; EOL, end-of-life.

Clinician-Specific Themes

Care Process Factors

General challenges to implementation included no standardized implementation process, forgetting to offer the form, the lack of sustainable reminders in place, the novelty of the AD process, time pressures, patients forgetting to complete/return forms, staff anxiety about conversation initiation, and patient worry about something being wrong with them for the clinician to ask about ADs. Switching electronic health records added its own barrier, which often superseded any other facilitation mechanism in place. If a clinic switched to a new EHR, virtually all office efficiency and orientation ground to a halt.

Implementation facilitating factors included systematic planning, effective teamwork, securing buy-in from clinic staff before implementation, and professional experience addressing EOL conversations. PF assistance with bringing attention to new process details was also helpful.

The Time Factor

Time was a concern raised across all groups and settings. Form introduction generally took less than 5 minutes, but 1 clinician routinely spent between 5 to 20 minutes in these conversations. Most physicians did not mind finding the time for the conversations because they felt it was important. They were also appreciative that the time required for these conversations is now reimbursable.

Discussion

Our mixed-methods study found that Five Wishes was better accepted by clinicians and patients alike. We identified 3 major rate-limiting factors for AD implementation: 1) an understandable AD form that reliably captures patient wishes; 2) an effective process for offering AD forms in primary care settings; and 3) ensuring that AD forms are completed and documented in the chart in a timely manner (“closing the loop”). Based on the findings of this study we have found that successful AD implementation will require the systematic application of these factors.

The most important finding of the qualitative analyses was the positive feedback about the usability and utility of Five Wishes. Patient acceptance and initiation of EOL care discussions was also easier with Five Wishes, which may make the closing of the EOL care gaps faster. A lower reading level made the form more understandable. It also helped with addressing needs such as literacy issues, greater patient frailty, chronic conditions, and diverse cultural contexts. The number of personal and social issues addressed and increased free text space were seen as improvements over OKAD. Patients and clinicians repeatedly stated that Five Wishes made it easier to discuss the importance of EOL in a more person-centered manner.

Patients in the Five Wishes group could more readily initiate a discussion about important EOL care choices with doctors and loved ones. Comments from patients about communication with their clinician’s office were more enthusiastic in the Five Wishes group. Five Wishes made the conversations easier and more memorable, leading to more positive comments.

Several clinicians discussed the problem of capturing more than 1 health care proxy in a prioritized manner. OKAD is ambiguous about how to document multiple proxies (eg, 1 or more per line) or how to clearly indicate priorities regarding multiple proxies. Five Wishes was better designed and included more specific instructions including space to list the designees’ names, addresses, and phone numbers.

One key recommendation of the IOM study is to improve “Professional Education and Development.”1 In our study, several clinicians stated that being in the study improved their skills of reviewing the AD forms with patients, including clinicians who felt they were already attuned to this before the study. Clinicians also expressed that the study helped them improve their EOL conversations.

Our study indicated that the reliable provision of AD forms was challenging in all practice sites. In 2016, PerryUndem, a national public opinion communications and research firm, conducted a telephonic survey of 736 physicians who saw people over 65 years (primary care, oncology, pulmonology, and cardiology) regarding ACP and EOL care conversations.18 Ninety-nine percent of the participants said ACP conversations were very important for good patient care, yet only 17% of patients reported talking about EOL issues or ACP with their physicians.19 Solberg’s practice change model20 states that priority of change is a key factor, yet both studies demonstrate that prioritization of this conversation requires more than just desire to make it different. With most guideline implementation efforts, practices need to adopt multi-pronged, system-level process improvements to provide evidence-based services with high fidelity. Identifying practice-level barriers to AD implementation as well as actions to overcome these barriers (eg, through best practices research) will help clinicians achieve better results. PerryUndem found that clinicians who more frequently discuss ACP issues were more likely to work in a hospital setting, have had formal EOL training, and have formal structures in place in their practices to assess patients’ EOL wishes.18 Primary care has other major barriers as well; the scope of practice is wide, while time is insufficient. Thus, all solutions must be streamlined and aligned with other competing priorities for success. This requires careful tailoring of new implementations to the environment and needs of end-users, which can be accomplished through practice facilitation.21–22 Streamlining is especially important for AD implementation, since it addresses a highly sensitive and more complex topic, often requiring human touch and deeper personal interaction.

Our results clearly indicate that clinician and patient participants responded more positively when the AD form was introduced by medical staff and then discussed briefly with the clinician. This structured teamwork approach helped address several fundamental problems, including waiting to see who would bring up the subject first; struggling for the right words to say; and knowing when it is the right time for the conversation.

Initiating discussions about ADs is a multi-faceted challenge that has emotional and personal components. Directly addressing general reluctance to EOL conversation initiation with clinic staff, observing behavior, and providing targeted advice/resources are appropriate strategies to alleviate this problem. Clinic staff engagement in the process of implementing AD forms and education have been pivotal to identifying and addressing barriers.

The EHR was repeatedly cited as a barrier to documenting the offering of the AD, or the “closing of the loop.” In the PerryUndem study 59% of physicians with access to an EHR where ACPs are easily located were more likely to talk with patients about their ACPs. However, being able to see that there is an ACP in the chart is different from being able to see the contents of the ACP. Of those who could locate the ACP in the EHR, only 31% could actually see the document contents. These systemic barriers need to be addressed to improve the rate of implementation. Asking physicians to engage in AD conversations without giving them tools to appropriately document and view the results is counterproductive.

Patients come to clinical visits with their personal notions, fears, literacy limitations, culture, community relations, and family dynamics. These factors may have far-reaching implications including whether they return a completed AD form to the practice. It is important to recognize and compassionately address these limitations as they arise to improve their comfort with AD completion.

Limitations

While we were able to improve the less than 10% baseline rate of offering ADs during this study, our overall offering rate was only 34%. A number of challenges need to be addressed for widespread utilization of AD forms in the broader population. These include time pressure, staff buy-in for the project, discomfort with the subject, fear that patients will think clinicians are foretelling dire diagnoses, etc. These can be addressed through systemic implementation which can ensure: consistent AD offering patterns, training of clinic staff/clinicians to initiate/participate in meaningful conversations, and provision of visual cues to remind patients and clinical staff to talk about ACP. Our study was limited by a shortened implementation period as well as the low number of study sites which affected our ability to measure AD completion rates and it widened confidence intervals in our models, particularly the models that account for patient clustering. We anticipate that larger numbers of practice clusters in future studies will address this issue.

Some of our Five Wishes patients and clinicians were exposed to the prevalent OKAD form before the study. However, this slight contamination effect strengthens our findings, since it occurred in the better-performing group.

Conclusion

Our study underscores the importance of addressing AD implementation barriers through a multi-faceted approach. A comprehensive approach may include the utilization of a well-performing AD form and the initiation of AD conversations during routine patient intake process. Implementing ADs through teamwork involving clinicians and staff is pivotal to help formulate consistent and more effective messages across the practice.

Funding:

Funding for this project provided by National Institutes of Health grant U5GM104938 distributed through the Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources (OSCTR) Grant C1092004 with matching funding from the Stephenson Cancer Center. Partial support provided by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant 1 U54GM104938, PI James) and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grant 1R25MD011564, PI Stoner/Houchen).

Footnotes

This article was externally peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to Aging with Dignity for graciously supplying a portion of the Five Wishes forms used in this study, Dr. Sara Vesely for her assistance in the statistical modeling for the study design, and Dr. Julie Stoner for her statistical assistance with the Generalized Estimating Equation analysis.

To see this article online, please go to: http://jabfm.org/content/32/2/168.full.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine; Committee on Approaching Death. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson WF, Aldrich N. Advance Care Planning: Ensuring Your Wishes Are Known and Honored If You Are Unable to Speak for Yourself. CDC Healthy Aging Program [pdf]. 2012. Critical Issues Brief. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/advanced-care-planning-critical-issue-brief.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2018.

- 3.Wickersham E. Email Survey of OKPRN members regarding percentage of completed Advance Directives on file in office. Internal Data OUHSC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer S, Min SJ, Cervantes L, Kutner J. Where do you want to spend your last days of life? Low concordance between preferred and actual site of death among hospitalized adults. J Hosp Med 2013;8:178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: A randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns 2007;69(1–3):165–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office OLR. Adult literacy in Oklahoma. 2015. Available from: https://libraries.ok.gov/literacy/facts-statistics/. Accessed on November 20, 2017.

- 7.Dignity AW. Five wishes document. 2017. Available from: https://agingwithdignity.org/five-wishes. Accessed on November 20, 2017.

- 8.Mueller LA, Reid KI, Mueller PS. Readability of state-sponsored advance directive forms in the United States: A cross sectional study. BMC Med Ethics 2010;11:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imai K, K G, and Nall C. The essential role of pair matching in cluster-randomized experiments, with application to the Mexican Universal Health Insurance Evaluation. Stat Sci 2009;24:29–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baskerville NB, Hogg W, Lemelin J. The effect of cluster randomization on sample size in prevention research. J Fam Pract 2001;50:W241–W246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell MJ. Cluster randomized trials in general (family) practice research. Stat Methods Med Res 2000;9:81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed JF 3rd. Adjusted chi-square statistics: Application to clustered binary data in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:201–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mancl LA, DeRouen TA. A covariance estimator for GEE with improved small-sample properties. Biometrics 2001;57:126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PerryUndem Research/Communication. Physicians’ views toward advance care planning and end-of-life care conversations: Findings from a national survey among physicians who regularly treat patients 65 and older. April 2016. Available from: https://www.cambiahealthfoundation.org/assets/files/Advance_Care_Report_F_Embargo.pdf.

- 18.Palosky C. Public strongly favors end-of-life conversations between doctors and patients, with about eight in 10 saying medicare and other insurers should cover these visits. 2015. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/press-release/public-strongly-favors-end-of-life-conversations-between-doctors-and-patients-with-about-eight-in-10-saying-medicare-and-other-insurers-should-cover-these-visits/. Accessed on June 4, 2018.

- 19.Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: A conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: A review of the literature. Fam Med 2005;37: 581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med 2006;19: 506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liddy C, Laferriere D, Baskerville B, Dahrouge S, Knox L, Hogg W. An overview of practice facilitation programs in Canada: Current perspectives and future directions. Healthc Policy 2013;8: 58–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]