Abstract

Plasmonic biosensing has emerged as the most sensitive label-free technique to detect various molecular species in solutions and has already proved crucial in drug discovery, food safety and studies of bio-reactions. This technique relies on surface plasmon resonances in ~50 nm metallic films and the possibility to functionalize the surface of the metal in order to achieve selectivity. At the same time, most metals corrode in bio-solutions, which reduces the quality factor and darkness of plasmonic resonances and thus the sensitivity. Furthermore, functionalization itself might have a detrimental effect on the quality of the surface, also reducing sensitivity. Here we demonstrate that the use of graphene and other layered materials for passivation and functionalization broadens the range of metals which can be used for plasmonic biosensing and increases the sensitivity by 3-4 orders of magnitude, as it guarantees stability of a metal in liquid and preserves the plasmonic resonances under biofunctionalization. We use this approach to detect low molecular weight HT-2 toxins (crucial for food safety), achieving phase sensitivity~0.5 fg/mL, three orders of magnitude higher than previously reported. This proves that layered materials provide a new platform for surface plasmon resonance biosensing, paving the way for compact biosensors for point of care testing.

Subject terms: Optical properties and devices, Imaging and sensing

Introduction

The unique properties of graphene and related layered materials (GRMs) are promising for applications in many areas1–3. In biology and healthcare, their chemical, electronic and optical properties offer exciting opportunities. GRMs have the ultimate surface to volume ratio, leading to strong interactions with biological systems. In addition, graphene’s conductivity is strongly influenced by interaction with ad-atoms yielding electrical single atom detection4. Several groups reported graphene applications in biosensing4–7. However, the use of graphene electronic devices for bio-detection is not straightforward, due to the complex graphene surface chemistry and electronic noise6.

An alternative approach is based on hybrid technologies where a layered material (LM) serves as a bio-functional surface, while detection is performed using conventional label-free optical transducers6–9. References 10,11 reported that a combination of graphene with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technology can provide such a hybrid. Being impenetrable to most atoms and ions1, GRMs can protect reactive metals (Cu, Ag, etc.) for a long (around a year) time in both air and water environments11. Thus, graphene protected Cu can undergo functionalization and various nanofabrication procedure without degradation of its properties11. SPR chips based on graphene protected cu show dark plasmon resonances (~0.01% reflection at resonance minimum) of high quality factors (>10), with 3 orders of magnitude better phase sensitivity than that of conventional Au films, due to better morphology of the deposited Cu11. Generally, LMs allow protection of the metal surface from the environment as well enabling the functionalization required to achieve selectivity. By bringing the functional sensing groups very close to the sensing metal surface, GRM monolayers offer very good protection against corrosion11, removing the need to functionalize the metal surface (which might damage the plasmonic properties of the metal) by being themselves bio-functionalized. This broadens the possible avenues for bio-functionalization and opens new opportunities for SPR biosensing, which, at present, lacks the sensitivity required to detect small (~1 fg/mL) concentrations of drugs, vitamins, antigens and viruses, as these can be deadly or pathogenic even in this ultra-low quantities.

Here, we present a layered material platform for SPR biosensing. We address three critical steps: i) robust protocols for metal protection using various LMs, ii) functionalization protocols for LMs on metallic surfaces, iii) bio-detection protocols which can be used with graphene protected metal. We note that ref. 11 introduced the use of graphene protection of the plasmonic properties of metals. However, steps ii) and iii) were not previously systematically discussed in literature and are generic to any type of hybrid biosensing. As a demonstration, we fabricate ultrasensitive SPR sensor functionalized with an anti-HT-2 toxin Fab fragment (HT2-10) and detected HT-2 toxin (~424 Da) with an amplitude detection limit ~1 pg/mL, 3 orders of magnitude better than currently available methods12,13 and a phase sensitivity limit ~0.5 fg/mL, which is comparable with label techniques. This paves the way to LM-based label-free SPR biosensing of small bio-objects at ultra-low concentrations. It is important to stress that enhancement of SPR sensitivity observed in our work comes from using phase sensitive methods instead of conventional amplitude detection14. However, a very high level of sensitivity enhancement (several orders of magnitude) comes from extreme resonance darkness, which can be achieved and conserved in water environment only in LM protected metal films. In addition, LM functionalization (in contrast to conventional Au functionalization) provides new avenues in achieving selectivity of bio-detection.

Results

Graphene-protected SPR biosensor

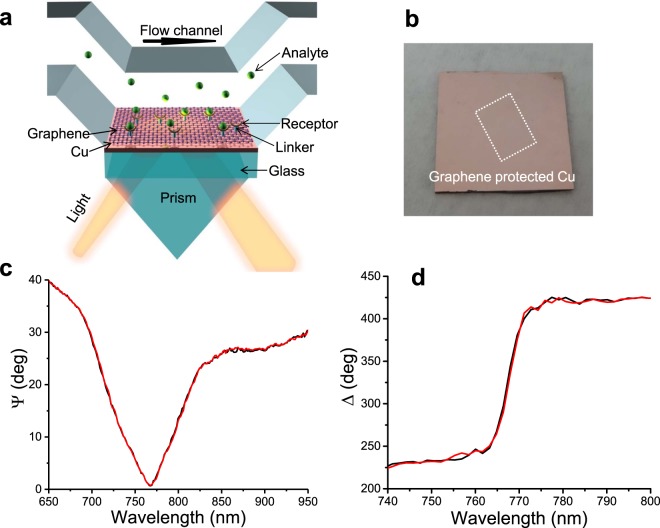

SPR biosensing15 exploits the excitation of surface plasmon polaritons in thin (~50 nm) metal films. The reaction between bio-receptors and bio-analytes modifies the surface plasmon polariton propagation and the optical reflection from a SPR chip changes significantly15. State-of-the-art SPR sensors provide selectivity, strong light confinement, and allow one to study bio-processes dynamics16. However, they lack sensitivity to measure small (<1000 Da) molecules and bio-objects, and cannot compete with label based technologies and be accessible for general use. LM protected SPR biosensors could solve this problem by providing unprecedented phase sensitivity to binding events17,18. Figure 1a is a schematic diagram of a flow cell for SPR biosensing. Graphene protected metal thin films (Cu is taken as an example, more combinations of layered LMs oxides and metals are described in Supplementary Materials) in which high (<1 fg/mL) sensitivity is achieved due to high quality plasmon resonances (see Methods). The surface plasmon polaritons in the metal film are excited in attenuated total reflection (ATR) geometry19–21. In the biosensing experiments, the analyte solutions are pumped into the flow cell. The binding of analyte to receptor on the sensor surface changes the local refractive index. These changes are monitored by the Cu SPR response, by measuring the ellipsometric amplitude ψ and phase Δ, see Methods.

Figure 1.

Graphene-protected Cu SPR biosensor. (a) Schematic diagram of flow cell for SLG-protected Cu SPR biosensing. (b) Image of a typical graphene-protected Cu SPR sensor chip. (c,d) Stability of the SPR in buffer solution: The change of Cu SPR ellipsometric parameters (amplitude ψ and phase Δ) of the sensor chip after pumping buffer solution for 15 minutes (the black and red curves). The sensor chip is pre-functionalized with receptor. The buffer solution is 1 mM NaP buffer (pH 7.3).

Figure 1b shows a typical graphene protected Cu SPR sensor chip. The dotted rectangular frame indicates the edge of the transferred single layer graphene (SLG). Unlike SLG-protected Cu, unprotected Cu oxidizes after exposure to water after ~30 minutes. Typical SPR curves for SLG procted Cu samples in NaP buffer solution are shown in Fig. 1c,d. They confirm excellent SPR repeatability in graphene protected Cu after continuous buffer pumping, suggesting full protection of Cu by SLG. In these experiments, the SLG on the sensor chip is pre-functionalized with receptors before being fixed in the flow cell. This indicates that neither specific nor non-specific binding happen at a detectable level on the chip surface in presence of buffer.

The low values of reflection ~0.01% observed at the SPR minimum (the darkness of SPR resonances) are necessary to achieve high values of phase sensitivity18. These values cannot be achieved for standard Au SPR chips designed for biosensing due to intrinsic roughness of evaporated and sputtered Au films16. At the same time, extremely dark SPR resonances can be observed in fresh Cu and Ag films. However, they deteriorate fast in water (and even air) environment11. Only combination of graphene (or other GRMs) with suitably chosen metal films11 can unlock (in principle unlimited) phase SPR sensitivity of bio-detection.

Protection of plasmonic properties of metals using layered materials

Effect of graphene transfer protocols on SPR quality

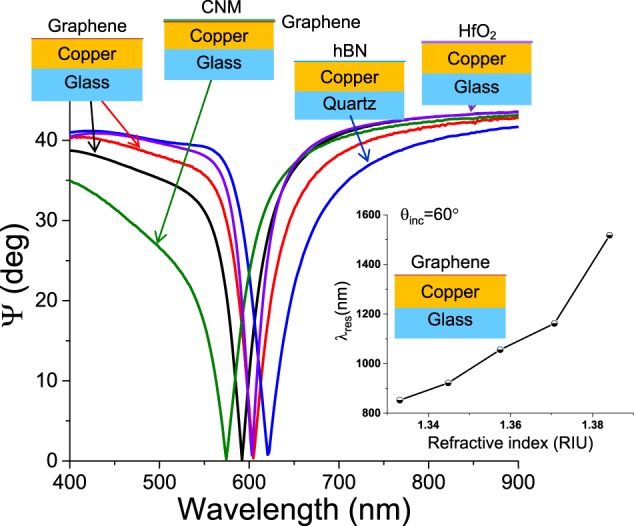

Generic transfer protocols for SLG protection of metals were described in ref. 11. We first check the effect of different protocols on the graphene protected Cu plasmonic properties. To this end, we fabricate SPR chips based on SLG protected Cu using wet transfer of chemical vapour deposition (CVD) graphene as described in Supplementary Information, Protocol 1, P1. The corresponding SPR spectrum of SLG protected Cu in air is shown in Fig. 2 (red curve), where it is compared to the SPR spectrum from the samples obtained using a different wet transfer protocol, Protocol 2, P2, as described in Supplementary (black curve). For both protocols, we observe very deep (~0.01% reflection at resonance minimum) and high quality factor (>10) durable (for a period of a year) resonances, suggesting that the procedure is robust and peculiarities of graphene transfer do not affect the possibility of using graphene protected Cu in point-of-care testing. We stress that this is not a given, since transfer protocols can have massive influence on the final SLG properties, as discussed in ref. 22. The right inset of Fig. 2 shows the dependence of resonance wavelength on refractive index of a water-glycerol mixture for SPR based on SLG protected Cu. The response is ~104 nm/RIU, where RIU is refractive index unit. This is in line with the sensitivity of standard Au SPR chips16. At the same time, the darkness of the resonances (i.e, the reflection value at the resonance minimum) in SLG protected Cu chips is two orders of magnitude better than Au, yielding enhanced phase sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Protection of plasmonic properties of metals using various materials. SPR curves measured in Cu protected by SLG. Red and black curves correspond to P1, P1; blue, hBN, purple 10 nm HfO2, green SLG and Carbon Nanomembrane (see Methods). All curves are measured in the attenuated total reflection geometry in air. The Cu thickness for all samples is 43.5 nm. The inset plots the spectral position of the SPR minimum as a function of the refractive index of the medium contacting the SLG protected Cu structure.

Refinement of graphene-based protection with the help of an additional protection

While the transfer protocol does not affect the SPR graphene protected Cu resonances quality, the durability of samples depends strongly on the SLG quality, as the life-time of SPR graphene protected Cu chips made from SLG with large amount of defects and pinholes decreases from months to weeks in water. The life-time can be improved significantly by depositing an additional ultrathin (~10 nm) layer of oxide (e.g., HfO2, Al2O3, etc.) before SLG transfer, or by transfer of a Carbon Nanomembrane (CNM) on SLG. A CNM is a ~1 nm thick material prepared by low energy electron induced crosslinking of aromatic self-assembled monolayers23. Due to its dielectric nature, CNMs can preserve SLG electronic properties via encapsulation24, as detailed in Supplementary Information. One could also make use of multiple SLGs to improve durability11. Figure 2 plots SPR resonances for Cu SPR samples protected by 10 nm HfO2 oxide with SLG on top, as well as CNM encapsulating SLG protected Cu with life-time >1 year (blue and green curves, respectively). Supplementary information reports measurements of SPR sensitivity for Ag samples protected by oxides and SLG, reaching ~2·104 nm/RIU. Note that there are no known protocols for HfO2 bio-functionalization, while CNM does not always show good adhesion to metals.

Protection of plasmonic properties of metals by other layered materials

Protection of metals by other LMs can yield additional benefits. E.g., being similar to SLG in crystalline structure, hBN could be a viable alternative to SLG for metal protection. At the same time, the hBN dielectric nature does not suppress the metal SPR. Figure 2 shows a deep and high quality SPR curve measured with SPR chips made from Cu and hBN, as detailed in Supplementary Information. The durability of Cu protection offered by hBN is 10 times lower than SLG, probably due to different adhesion and hydrophobic properties of the two materials.

Direct growth of graphene for plasmonic protection

SLG can be directly grown on Cu25. CNMs can also be directly prepared on metal substrates by vapor deposition of aromatic molecules and subsequent electron irradiation in vacuum26. Hence, one could avoid transfer and grow SLG and CNMs directly on the SPR Cu chip. We thus fabricate SPR Cu substrates using electron beam deposition with excellent plasmonic resonances11, and then grow SLG and CNMs, as detailed in Supplementary Information. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows that the quality of the plasmonic resonances after growth is poor. This is probably due to the change of Cu morphology during growth, which is performed at 1000 °C, close to the Cu melting point ~1085 °C25.

Thus, wet transfer of CVD SLG on SPR structures results in robust SPR chips with excellent plasmonic resonances (darkness of 0.01%) with long (~year) life-time in air and water. An additional thin (~10 nm) layer of oxide deposited on the metal prior to transfer allows one to tune the resonance spectral position and add further protection. Alternatively, CNMs encapsulating SLG enhance the life-time and allows the use of a different bio-functionalized strategy based on amino groups24.

Functionalization of graphene

The success of Au based SPR biosensors15 is also due to the progress in Au surface functionalization27–30, often based on well-developed self-assembly and chemistry of thiol alkane layers29. While phase SLG protected Cu SPR biosensors have 6 orders of magnitude higher sensitivity than amplitude Au based SPR (~0.2 fg/mm2 measured using phase detection with SLG hydrogenation11 versus ~1 pg/mm2 measured in amplitude detection15), there is a question whether functionalization of GRMs compatible with SPR biosensing is possible.

The SLG surface can be functionalized by either covalent or non-covalent bonding31–35. The first step consists in introducing COOH or NH2 endgroups for the attachment of bio-receptors. When both bio-receptor and bio-analyte are small (<1000 Da) molecules, this can be achieved during a biosensing protocol, as detailed below for HT-2 toxin detection. For larger molecules (fragments of DNA, aptamers, etc.), COOH or NH2 terminal groups should be attached to SLG, with a density that would stop the binding events from overlapping (grafting36,37). Since both Cu and SLG are good conductors, the covalent functionalization of graphene protected Cu can be performed using electrochemistry38. The protocol and outcome of functionalization are described in Supplementary Information. The grafting density is controlled by the Faraday law, and hence can be manipulated by changing the time of grafting. Functionalized GRMs can be activated, modified through chemical reactions to other ending, while preserving excellent SPR characteristics.

Detection of HT-2 toxin by graphene-protected Cu SPR biosensor

We consider the detection of small (<1000 Da) molecules where conventional Au SPR lacks sensitivity16. To demonstrate the potential of LM protected SPR chips, we detect the HT-2 toxin with functionalized SLG protected Cu. Direct comparison to the state-of-the-art SPR detection based on Au is reported in Supplementary Information.

HT-2 is a fungal metabolite belonging to a family of mycotoxins, referred to as the trichothecenes, with a molecular weight ~424 Da, see ref. 12,13. It is the main metabolite of T-2 mycotoxin12. Both toxins are produced by moulds that grows on improperly stored grains12. HT-2 can cause acute or chronic intoxication of humans and animals39,40. The ability to detect low quantities of HT-2 is therefore of great interest for food safety and it can be performed by conventional SPR techniques based on Au with limited sensitivity (~ng/mL) as reported in ref. 14.

The protocol for SLG functionalization for HT-2 detection with graphene protected Cu SPR is shown in the top inset of Fig. 3. This method was previously studied and characterized in detail41 and it has earlier been used for successful Fab fragment immobilization on graphene42,43. It yields the areal number density of active biorecognition sites at the level of ~3·1011 1/cm2. A sensor chip is pre-functionalized with linker and receptor (see Fig. 3 and Methods for details). The linker (1-Pyrenebuturic acid N-hydroxy-succinimide ester) has a phenyl ring in the chemical structure that binds to SLG by π–π stacking. An amide group on each receptor (HT2-10 Fab fragment) binds to the NHS ester on the linker. Ethanolamine is used to block linkers not reacted with receptors to prevent non-specific binding. After rinsing in de-ionized water, the sensor chip is fixed on the flow channel and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with and without HT-2 is alternately pumped into the flow cell. When toxins bind to the surface within the range of the electric surface plasmon polariton field they modify the local refractive index near the surface of the metal and thereby change the SPR properties (resonance wavelength and light phase) directly monitored by ellipsometry.

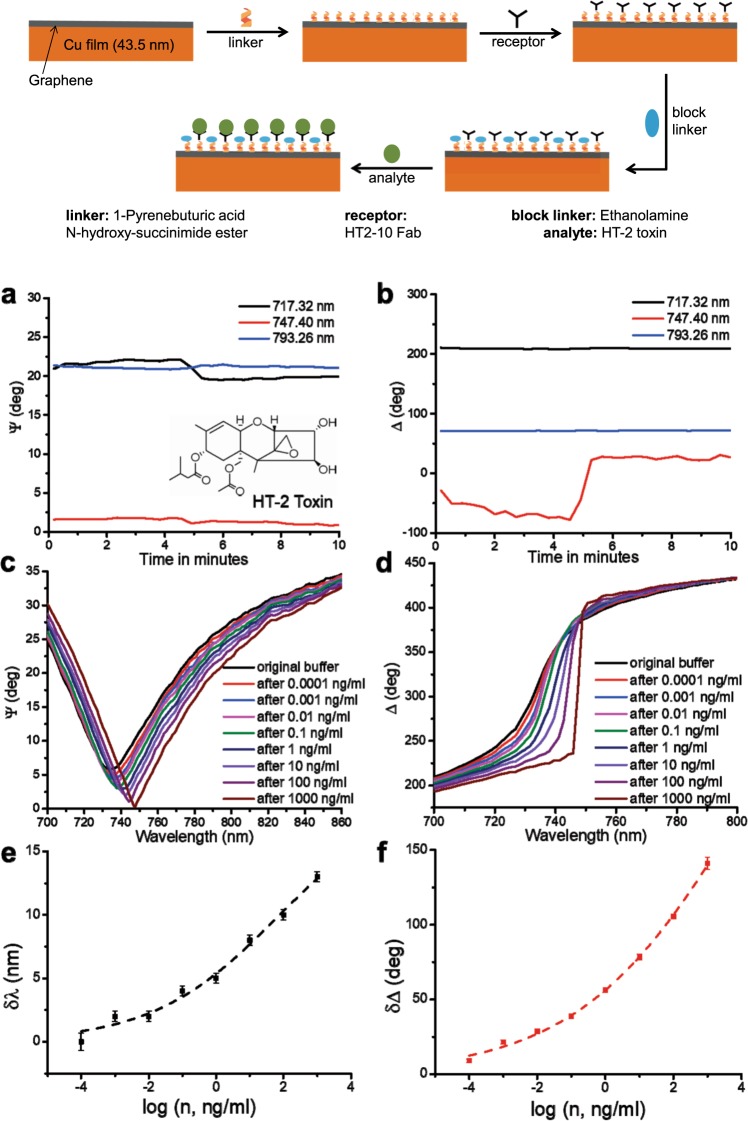

Figure 3.

Graphene protected Cu SPR biosensing of HT-2. (a,b) Ellipsometric parameters ψ (amplitude) and Δ (phase) of the SPR curve of functionalized SLG protected Cu chips at 717.32, 747.40 and 793.26 nm, as a function of time when the sensor chip reacts with HT-2. The pumping time of PBS is~4.5 mins. The inset in (a) shows the molecular structure of HT-2. (c,d) SPR spectral curves after reacting with different concentrations of HT-2 in PBS. (e,f) The shift of resonant wavelength (δλ) for ψ and the change of phase (δΔ) as a function of logarithm of concentration, n, of HT-2. The dark dashed line shows the sigmoidal fit of δλ as a function of log(n), and the red dashed line is the same for δΔ, giving nH = 0.2 ± 0.01 and KH > 1 µg/mL. The top inset schematically describes the protocol of SLG functionalization for HT-2 bio-sensing.

Figure 3a,b plot the change of the ellipsometric parameters (ψ and Δ) at 717.32, 747.40, and 793.26 nm, as a function of time in PBS containing~1 pg/mL HT-2. For SLG protected Cu film functionalized with HT2-10 Fab fragment the resonance maximum is at 747 nm at an incident angle of 590. Therefore, the greatest phase sensitivity occurs at 747.40 nm, while the phase at the other wavelengths remains approximately constant. After pumping ~1 pg/mL of HT-2 solution into the flow channel there is no substantial change in amplitude (ψ) at all wavelengths. The phase has >100 degrees jump at 747.40 nm during the first 4.5 minutes, while there is almost no change at the other two wavelengths. The large phase change at 747.40 nm shows that phase measurements can provide higher sensitivity than amplitude measurements. Figure 3e,f show the evolution of resonant wavelength and light phase, due to the change of refractive index induced by adding different concentrations of HT-2 superimposed with sigmoidal modelling of the curves (the dashed lines).

Discussion

The change of resonant wavelength shift and phase change with increasing toxin concentration is described well by a sigmoidal function44. This fit has its physical origins in the Langmuir isotherm model45,46 and its derivatives (such as the Hill equation47) which describe the adsorption of molecules on to a surface. Originally, the Hill equation provided a description of the binding of ligand to receptors sites on proteins at equilibrium, as a function of ligand concentration, c47. It can be written as , where f is the fraction of sites occupied by ligands, kH is the ligand concentration at which half of the available receptor sites are occupied, and nH is the Hill coefficient, describing cooperativity of ligand binding47. Positive cooperativity, nH > 1, implies that the binding of a ligand increases the binding affinity of the neighboring sites47. Negative cooperativity, nH < 1, occurs when the binding of a ligand decreases the binding affinity of the neighboring sites47. In first approximation, we can consider the shift of resonance wavelength and light phase at resonance to be proportional to the site occupancy number f(c), taken in the sigmoidal form. The sigmoidal fits provide very good approximation to the measured data, see Fig. 3e,f, where the fits are plotted as dotted lines. Figures 3 and 4 indicate that the detection limit of amplitude measurements is ~1 pg/mL, 3 orders of magnitude higher than in refs. 12,13. Figure 3d plots changes in phase due to binding with increasing HT-2 concentration. Near the resonant wavelength we observe a big phase jump (~200 degrees). The relations between phase (δΔ) and HT-2 concentration are shown in Fig. 3f. The phase change (~8.9 degrees) after testing on 1 pg/mL HT-2 reveals an ultrasensitive detection limit ~0.5 fg/mL for an experimental ellipsometer phase resolution ~0.05 degrees. (The improvement over conventional amplitude sensitivity comes about from the darkness of SLG protected Cu resonances and enhanced stability of phase measurements48,49). This limit could be pushed down to ~0.1 fg/mL in a dedicated phase setup capable of a phase resolution of 0.01 degrees50, 1000 times more sensitive than amplitude measurements. The sensitivity of commercial Au SPR for HT-2 is >1 ng/mL12,14,51. To check this, we performed measurements of HT-2 with Au Biacore chips on a Biacore T-200, using the same protocol and achieved sensitivity~1 ng/mL, as detailed in Supplementary Information.

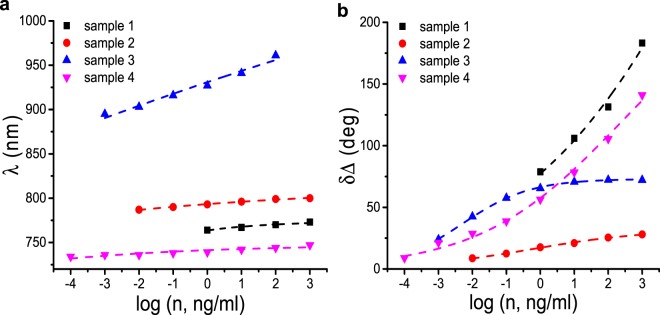

Figure 4.

Sensitivity detection of SLG-protected Cu SPR biosensors. (a) change of spectral position Ψmin(λ) as a function of concentration (n) of HT-2. (b) corresponding change (jump) of phase (δΔ) as a function of n. Dashed lines are sigmoidal fits of λmin and δΔ.

We note that the SPR properties of SLG protected metals in water significantly depend on metal thickness16, presence of hydrocarbons under SLG52, etc. Figure 4 shows the detection of HT-2 with 4 SLG protected Cu samples which differ in geometry and provide resonances from 700 to 1000 nm. The amplitude sensitivity increases with resonance wavelength, while the phase sensitivity depends on the resonance darkness and varies from ~0.1 pg/mL to ~0.4 fg/mL. The sigmoidal fits for resonant wavelength (λ) and phase change (δΔ) as a function of concentration are shown by dotted lines in Fig. 4a,b. These yield a universal value of cooperativity nH ~ 0.2 and variable KH. The negative cooperativity is most probably connected to the two dimensional nature of toxin-receptor interaction.

Non-specific binding on the surface of the sensor chip can also affect the results. A negative control study using neosolaniol12 was conducted on a SLG-protected Cu SPR biosensor (see Methods and Supplementary Information for details) to confirm selectivity. Each increase in neosolaniol concentration results in a resonant wavelength shift <1 nm, close to the limit of our ellipsometer’s spectral resolution. The very small shift of the resonant wavelength indicates non-specific binding does not affect the results. Our functionalization procedure and methods can be used for the detection of HT-2 in a commercial beer, as shown in Fig. S13.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated a viable layered material platform for hybrid SPR biosensing. Graphene and hBN are excellent protectors of plasmonic properties or reactive metals with strong potential for biosensing functionalization. The life-time can be significantly enhanced by use of an additional thin layer of oxide deposited on the metal prior to SLG transfer or a transferred CNM encapsulating SLG. We realised extremely sensitive graphene protected copper SPR biosensors for HT-2 detection. We achieved a phase graphene protected copper SPR detection limit~0.5 fg/mL, 6 orders of magnitude lower than amplitude Au SPR. The layered material platform SPR biosensing could be used to further enhance specificity of molecular recognition elements. Our approach paves the way to realize novel biosensors with high sensitivity for point of care testing.

Methods

Film depositions

Cu is deposited on a cleaned glass substrate (size: 25 mm × 25 mm, thickness: 1 mm) by electron-beam evaporation at a base pressure ~10−7 mbar and growth rate ~0.3 nm/s. As an electron-beam target, we use 99.99% Cu from Sigma-Aldrich. A 1.5 nm Cr adhesion layer is evaporated onto the substrate before Cu.

Metal protection by layered materials

SLG transfer

CVD SLG-on-Cu is covered by poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) using spin coating. Then the PMMA film SLG attached is isolated by 25 g/L of ammonium persulfate solution that chemically etches Cu. The resulting PMMA-SLG is cleaned by deionized (DI) water and then transferred onto the target Cu. Next, the SLG covered Cu substrate is further annealed at 150 °C for 3 hours to enhance the adsorption. Finally, the PMMA layer is removed in acetone and the SLG surface left to dry in air for 6 hours.

h-BN transfer

CVD monolayer-h-BN is grown on Pt using ammonia borane as a precursor. The Pt foil is loaded into the center of a vacuum quartz tube placed in a furnace, and ammonia borane placed in a sub-chamber. The furnace is heated to 1100 °C under H2 gas (10 sccm). The sub-chamber is heated to 150 °C for the decomposition of ammonia borane. The growth of monolayer-h-BN on Pt is initiated by opening a valve of the sub-chamber. During growth for 30 min, the pressure is maintained at 0.13 Torr. After growth, the furnace is cooled down to room temperature under H2. Monolayer-h-BN is then transferred onto the target Cu substrate using electrochemical delamination method.

Carbon Nanomembranes are prepared from 4’-Nitro-1,1’-biphenyl-4-thiol (NBPT) (Taros, 95%, sublimated before use), as described in refs. 23,53. Electron beam irradiation is used to crosslink the molecules into a stable 1 nm film. Crosslinking is performed in high vacuum (<5 × 10−8 mbar) with an electron floodgun (Specs FG20) at 100 eV and a dose of 50 mC/cm2. The nitro group is reduced to an amino group, later used for bio-functionalization. CNMs are then transferred with a supporting PMMA film onto a SLG/Cu substrate. PMMA is then removed using acetone. The direct deposition of CNMs on a SPR chip is described in Supplementary Information.

Graphene grafting

The protocol for graphene grafting with COOH terminal groups by electrochemical method comprises the following steps: First, a solution of 0.052 mmol of 4-NH2-3,5-F2PhCOOH with 60 mg of 85% H3PO4 and 25 ml of Milli-Q water. 12.8 mmol of imidazole is prepared. Second, an electrochemical cell is set up in a glass beaker using a Cu tape to fix the substrate, and to serve as electrode, a piece of Pt foil with surface area equal or larger than the conductive substrate area as the counter electrode, and a standard aqueous Ag/AgCl as reference electrode. All these electrodes are connected to a potentiostat. The chronoamperometry for the potentiostat is set to −0.4 V for 60 seconds. Third, 0.5 ml of a 0.1 M aqueous solution of NaNO2 are added to the previously prepared solution and shaken for 3 minutes. The freshly prepared solution is transferred to the cell (to cover the sample) and the electrochemical grafting is performed for~60 seconds. Finally, after disconnecting the electrodes, the substrate is washed with excess water and dried at room temperature under ambient conditions. If non-grafted by-products are present, an additional washing step is performed. E.g., for COOH containing impurities, the grafted sample is dipped into 1% NaOH, rinsed with water, then dipped into 1% acid (e.g. HCl or phosphoric), rinsed with an excess of water and dried.

HT-2 biosensing protocol

To detect HT-2 selectively, a SLG-protected Cu SPR sensor chip needs to be functionalized by using 1-Pyrenebuturic acid N-hydroxy-succinimide ester as a linker and anti-HT-2 toxin Fab fragment as a receptor12,13. First, 1-Pyrenebuturic acid N-hydroxy-succinimide ester linker solution (2 mg/mL) in 100% MeOH is prepared. After sonication, the linker solution is incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, without shaking, to ensure solution saturation. Then we filter the saturated solution with a disposable filter unit attached to a syringe, and then put the sensor chip into the filtered solution. Filtering removes the undissolved linker and the resulting filtered solution is clear. After one-hour incubation, the chip is washed by pure 100% MeOH and 1 × PBS (pH 7.3). Then, the chip is transferred to 50 µg/ml of HT2-10 Fab solution in 1 × PBS (pH 5), and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Next, the chip is moved from the antibody solution to 100 mM Ethanolamine solution (1 M Ethanolamine stock solution (pH 8.5) diluted 1:10 in distilled water), and incubated for 10 min. The Ethanolamine solution is used to block the linker without binding with receptor. Finally, the chip is washed with distilled water and stored in distilled water before SPR measurements.

For positive tests, 8 concentrations of HT-2 in 0.1 × PBS (pH 7.3) are prepared at 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng/ml. For negative tests, same concentrations of neosolaniol (1 mg/mL in 100% DMSO) in 0.1 × PBS (pH 7.3) are prepared.

Ellipsometry measurements of SPR

The data are acquired using a focused beam M-2000F spectroscopic ellipsometer (J. A. Woollam, Inc.) with a beam size ~30 × 60 μm (for an angle of incidence of 590). We record Ψ and Δ from 250 to 1700 nm with a 1 nm wavelength step. The amplitude ratio (tan Ψ) and phase difference (Δ) represent the change of outgoing polarization for p- and s-light so that , where rp and rs are the complex reflection coefficients for the p- and s-polarized light respectively54. The absence of air bubbles in the flow channel is checked with a CCD camera placed directly above the channel. The quality factor of a SPR curve is defined as the ratio of the resonance wavelength over the full width of the resonance at half maximum. Fresnel calculations for SLG protected Cu chips (used in bio-experiments) were performed in ref. 11. This showed a good agreement with measured data.

In the case of selective HT-2 detection, we deal with a surface chemistry described by the Hill equation which is non-linear in nature due to the dynamics of binding ligands to receptors. Hence, direct conversion of rp to the refractive index changes is impossible in this case. Only for non-specific binding (with neosolaniol), as discussed in Supplementary Information, we observe a linear change of resonance wavelength shift with concentration.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the EU Graphene Flagship, the China Scholarship Council, the North-West Nanoscience Doctoral Training Centre, EPSRC Grant EP/G03737X/1, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grants TU149/5-1, TU149/8-2, INST 275/257-1 FUGG, ERC Grant Hetero2D, EPSRC Grants EP/K01711X/1, EP/K017144/1, EP/N010345/1, and EP/L016087/1. We thank Oleksandr Ivasenko and Steven de Feyter of University of Leuven for the graphene bio-functionalized samples used in this work.

Author contributions

A.N.G. and K.S.N. conceived the idea, F.W., P.A.T. and V.G.K. fabricated samples and performed optical and biological measurements. A.C.F., I.G., D.D.F., G.K., M.K., H.S.S. and D.V.A., developed graphene and hBN transfer and growth procedures for SPR chips. C.N., M.K. and A.T. developed CNMs for protection of SPR metal. H.O.A., M.S. and K.I. developed protocols for graphene based biosensing. All authors contributed to discussion and paper writing.

Data and code availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information Files. Additional data and codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-56105-7.

References

- 1.Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater. 2007;6:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novoselov KS, et al. A roadmap for graphene. Nature. 2012;490:192–200. doi: 10.1038/nature11458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari AC, et al. Science and technology roadmap for graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems. Nanoscale. 2015;7:4598–4810. doi: 10.1039/C4NR01600A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schedin F, et al. Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on graphene. Nat Mater. 2007;6:652–655. doi: 10.1038/nmat1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu CH, Yang HH, Zhu CL, Chen X, Chen GN. A graphene platform for sensing biomolecules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:4785–4787. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pumera M. Graphene in biosensing. Materials Today. 2011;14:308–315. doi: 10.1016/s1369-7021(11)70160-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Justino CIL, Gomes AR, Freitas AC, Duarte AC, Rocha-Santos TAP. Graphene based sensors and biosensors. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2017;91:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2017.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grigorenko AN, Polini M, Novoselov KS. Graphene plasmonics. Nature Photonics. 2012;6:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2012.262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigo D., Limaj O., Janner D., Etezadi D., Garcia de Abajo F. J., Pruneri V., Altug H. Mid-infrared plasmonic biosensing with graphene. Science. 2015;349(6244):165–168. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salihoglu O, Balci S, Kocabas C. Plasmon-polaritons on graphene-metal surface and their use in biosensors. Applied Physics Letters. 2012;100:213110. doi: 10.1063/1.4721453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kravets VG, et al. Graphene-protected copper and silver plasmonics. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5517. doi: 10.1038/srep05517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arola HO, et al. Specific Noncompetitive Immunoassay for HT-2 Mycotoxin Detection. Anal Chem. 2016;88:2446–2452. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arola Henri, Tullila Antti, Nathanail Alexis, Nevanen Tarja. A Simple and Specific Noncompetitive ELISA Method for HT-2 Toxin Detection. Toxins. 2017;9(4):145. doi: 10.3390/toxins9040145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meneely JP, Sulyok M, Baumgartner S, Krska R, Elliott CT. A rapid optical immunoassay for the screening of T-2 and HT-2 toxin in cereals and maize-based baby food. Talanta. 2010;81:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liedberg B, Nylander C, Lundström I. Biosensing with surface plasmon resonance ‐ how it all started. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 1995;10:i–ix. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(95)96965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homola JYS, Gauglitz G. Surface plasmon resonance sensors: review. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 1999;54:3–15. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(98)00321-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grigorenko AN, Nikitin PI, Kabashin AV. Phase jumps and interferometric surface plasmon resonance imaging. Applied Physics Letters. 1999;75:3917–3919. doi: 10.1063/1.125493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kravets VG, et al. Singular phase nano-optics in plasmonic metamaterials for label-free single-molecule detection. Nat Mater. 2013;12:304–309. doi: 10.1038/nmat3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turbadar T. Complete absorption of light by thin metal films. Proceedings of the Physical Society of London. 1959;73:40–44. doi: 10.1088/0370-1328/73/1/307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kretschmann E, Raether H. Radiative Decay of Non Radiative Surface Plasmons Excited by Light. zna. 1968;23:2135. doi: 10.1515/zna-1968-1247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kretschmann E. Decay of non-radiative surface plasmons into light on rough silver films. Comparison of Experimental and Theoretical Results. Optics Communications. 1972;6:185–187. doi: 10.1016/0030-4018(72)90224-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purdie DG, et al. Cleaning interfaces in layered materials heterostructures. Nature Communications. 2018;9:5387. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07558-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turchanin A, Gölzhäuser A. Carbon Nanomembranes. Advanced Materials. 2016;28:6075–6103. doi: 10.1002/adma.201506058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woszczyna M, et al. All-Carbon Vertical van der Waals Heterostructures: Non-destructive Functionalization of Graphene for Electronic Applications. Advanced Materials. 2014;26:4831–4837. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, et al. Large-Area Synthesis of High-Quality and Uniform Graphene Films on Copper Foils. Science. 2009;324:1312. doi: 10.1126/science.1171245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matei DG, et al. Functional Single-Layer Graphene Sheets from Aromatic Monolayers. Advanced Materials. 2013;25:4146–4151. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen HH, Park J, Kang S, Kim M. Surface plasmon resonance: a versatile technique for biosensor applications. Sensors (Basel) 2015;15:10481–10510. doi: 10.3390/s150510481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosicke F, et al. Electrochemical functionalization of Au by aminobenzene and 2-aminotoluene. J Phys Condens Matter. 2016;28:094004. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/28/9/094004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bain CD, George JE, Whitesides M. Formation of monolayers by the coadsorption of thiols on gold: variation in the head group, tail group, and solvent. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:7155–7164. doi: 10.1021/ja00200a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bo Johnsson SL. Gabrielle Lindquist. Immobilization of proteins to a carboxymethyldextran-modified gold surface for biospecific interaction analysis in surface plasmon resonance sensors. Anal Biochem. 1991;198:268–277. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90424-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottari G, et al. Chemical functionalization and characterization of graphene-based materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:4464–4500. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00229g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsnelson DWBaMI. Chemical functionalization of graphene. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2009;21:344205. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/34/344205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Englert JM, et al. Covalent bulk functionalization of graphene. Nat Chem. 2011;3:279–286. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Georgakilas V, et al. Functionalization of graphene: covalent and non-covalent approaches, derivatives and applications. Chem Rev. 2012;112:6156–6214. doi: 10.1021/cr3000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong X, Liu G, Li Y, Yu DYW, Teoh WY. Functionalized-Graphene Composites: Fabrication and Applications in Sustainable Energy and Environment. Chemistry of Materials. 2016;28:8082–8118. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elena Bekyarova MEI, et al. Chemical Modification of Epitaxial Graphene: Spontaneous Grafting of Aryl Groups. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1336–1337. doi: 10.1021/ja8057327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.John Greenwood THP, et al. Covalent Modification of Graphene and Graphite Using Diazonium Chemistry: Tunable Grafting and Nanomanipulation. ACS Nano. 2015;9:5520–5535. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delamar M, Hitmi R, Pinson J, Saveant JM. Covalent modification of carbon surfaces by grafting of functionalized aryl radicals produced from electrochemical reduction of diazonium salts. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:5883–5884. doi: 10.1021/ja00040a074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocha O, Ansari K, Doohan FM. Effects of trichothecene mycotoxins on eukaryotic cells: a review. Food Addit Contam. 2005;22:369–378. doi: 10.1080/02652030500058403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oplatowska-Stachowiak Michalina, Kleintjens Tim, Sajic Nermin, Haasnoot Willem, Campbell Katrina, Elliott Christopher, Salden Martin. T-2 Toxin/HT-2 Toxin and Ochratoxin A ELISAs Development and In-House Validation in Food in Accordance with Commission Regulation (EU) No 519/2014. Toxins. 2017;9(12):388. doi: 10.3390/toxins9120388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hinnemo M, et al. On Monolayer Formation of Pyrenebutyric Acid on Graphene. Langmuir. 2017;33:3588–3593. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b04237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andoy NM, Filipiak MS, Vetter D, Gutiérrez-Sanz Ó, Tarasov A. Graphene-Based Electronic Immunosensor with Femtomolar Detection Limit in Whole Serum. Advanced Materials Technologies. 2018;3:1800186. doi: 10.1002/admt.201800186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okamoto S, Ohno Y, Maehashi K, Inoue K, Matsumoto K. Immunosensors Based on Graphene Field-Effect Transistors Fabricated Using Antigen-Binding Fragment. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 2012;51:06FD08. doi: 10.1143/jjap.51.06fd08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goutelle S, et al. The Hill equation: a review of its capabilities in pharmacological modelling. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 2008;22:633–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langmuir I. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surfaces of Glass, Mica and Platinum. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1918;40:1361–1403. doi: 10.1021/ja02242a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuck P. Use of Surface Plasmon Resonance to Probe the Equilibrium and Dynamic Aspects of Interactions Between Biological Macromolecules. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 1997;26:541–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill AV. The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of haemoglobin on its dissociation curves. J Physiol (Lond) 1910;40:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabashin AV, Patskovsky S, Grigorenko AN. Phase and amplitude sensitivities in surface plasmon resonance bio and chemical sensing. Opt. Express. 2009;17:21191–21204. doi: 10.1364/OE.17.021191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabashin AV, et al. Phase-Responsive Fourier Nanotransducers for Probing 2D Materials and Functional Interfaces. Advanced Functional Materials. 2019;0:1902692. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201902692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Junfeng L, Xiang D, Xinglong Y, Dongsheng W. Data analysis of surface plasmon resonance biosensor based on phase detection. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2005;108:778–783. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2004.12.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin Xialu, Guo Xiong. Advances in Biosensors, Chemosensors and Assays for the Determination of Fusarium Mycotoxins. Toxins. 2016;8(6):161. doi: 10.3390/toxins8060161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kravets VG, et al. Spectroscopic ellipsometry of graphene and an exciton-shifted van Hove peak in absorption. Physical Review B. 2010;81:155413. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.155413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turchanin A, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Electron-Induced Cross-Linking in Aromatic SAMs. Langmuir. 2009;25:7342–7352. doi: 10.1021/la803538z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azzam, R. M. A. & Bashara, N. M. Ellipsometry and polarized light. (North-Holland Pub. Co., 1977).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information Files. Additional data and codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.