Abstract

High risk forms of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) promote cancerous lesions and are implicated in almost all cervical cancer. Of particular relevance to cancer progression is regulation of the early promoter that controls gene expression in the initial phases of infection and can eventually lead to precancer progression. Our goal was to develop a stochastic model to investigate the control mechanisms that regulate gene expression from the HPV early promoter. Our model integrates modules that account for transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational and post-translational regulation of E1 and E2 early genes to form a functioning gene regulatory network. Each module consists of a set of biochemical steps whose stochastic evolution is governed by a chemical Master Equation and can be simulated using the Gillespie algorithm. To investigate the role of noise in gene expression, we compared our stochastic simulations with solutions to ordinary differential equations for the mean behavior of the system that are valid under the conditions of large molecular abundances and quasi-equilibrium for fast reactions.

The model produced results consistent with known HPV biology. Our simulation results suggest that stochasticity plays a pivotal role in determining the dynamics of HPV gene expression. In particular, the combination of positive and negative feedback regulation generates stochastic bursts of gene expression. Analysis of the model reveals that regulation at the promoter affects burst amplitude and frequency, whereas splicing is more specialized to regulate burst frequency. Our results also suggest that splicing enhancers are a significant source of stochasticity in pre-mRNA abundance and that the number of viruses infecting the host cell represents a third important source of stochasticity in gene expression.

Keywords: Feedback regulation, stochastic bursting, RNA splicing

1. Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small double stranded DNA viruses of the Papillomaviridae family. They infect epithelial cells and cause a variety of lesions ranging from common warts to cervical neoplasia and cancer. To date, more than 150 human papillomavirus types have been completely sequenced [1]. The most well studied HPV strains are the mucosal Alpha types involved in the development of precancerous and cancerous lesions, especially HPV-16, −18, −31.

HPVs are primarily epithelial specific viruses [2] and their life cycle is strictly linked to the infected keratinocytes differentiation program. HPV is characterized by a circular DNA genome of approximately 8 kb in size, containing three promoters, that can be divided into three major regions, as shown in Fig 1A. The first region consists of a noncoding upstream regulatory region and is referred to as the long control region (LCR). It contains the early core promoter regulating DNA replication and the transcription of the HPV early genes [3] in the initial phase of the infection. The LCR also contains the binding sites for cellular transcription factors able to exogenously enhance or silence transcriptional activity. The second region encodes proteins necessary for viral DNA replication, cell-cycle regulation and oncogenesis transformation, labeled as E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7 and E8 in Fig. 1A. In particular, E1 and E2 represent the regulatory core of the early promoter and are the first genes to be transcribed by the early promoter at the beginning of the infection [4]. E1 is the main regulator of viral DNA replication, while E2 acts in cooperation with E1 in initializing viral replication. E2 is also the main transcriptional regulator of the early promoter [5]. In particular, E2 binds as a dimer to the early promoter. At low concentrations E2 has a positive effect on gene expression, whereas at high concentrations it represses transcription [2], [6], [7]. Recently it was also discovered that a direct E1 and E2 protein-protein interaction can stabilize E2, besides increasing E2 transcriptional promoter activity [8]. The third region (including L1 and L2 late genes) encodes viral structural proteins [1], [3].

Fig 1. HPV molecular biology.

(A) HPV genome structure. The HPV genome is shown as a black circle with the early (PE), late (PL) and E8 (PE8) promoters marked by arrows. The six early ORFs (in red), namely the regulatory genes E1, E2, E4, E5 are expressed from either PE or PL, the oncogenes E6 and E7 are expressed only by PE and E8 is expressed only by PE8, depending of the stage of the viral lifecycle. The late ORFs L1 and L2 (in orange) are expressed from PL. All the viral genes are encoded on one strand of the double-stranded circular DNA genome. (B) The early promoter. This promoter accounts for positive and negative transcriptional regulation and is modeled with two binding sites where DE2 dimer and E1E2 heterodimer can bind and modulate transcription. (C) Splicing regulation. E1 and E2 transcript levels are spliced at the splicing sites SA742 and SA2709, respectively, while the remaining early genes are spliced at SA3358, regulated by the splicing factor SRSF1. E1 and E2 are produced in the absence of splicing factor SRSF1, hence they are indirectly regulated by this latter. (D) The SRSF1 promoter. This promoter is modeled as a two-state system with E2 transactivation. This constitutes a negative feedback loop for E1 and E2 expression. The formation of the heterodimer between SRSF1 protein and transcript, mSRSF1/SRSF1, is a negative regulator of SRSF1 activity.

The early promoter is policystronic, hence producing a pre-mRNA that is subject to splicing to yield single transcripts. Important and well-studied splicing sites that post-transcriptionally regulate the expression of early genes are the splicing site SA2709, SA742 and the major 3’ splicing site SA3358, controlling the splicing of E2, E1 and the remaining early genes, respectively [5], [9]. Splicing at the site SA3358 is enhanced by the splicing factor SRSF1 [5].

To better understand the mechanisms that regulate gene expression during the first stages of infection in the basal layer, we developed a stochastic model of the HPV early promoter that builds on our preliminary deterministic model of the system [10]. Mathematical models describing viral regulation of gene expression exist with a notable example being HIV. For the case of HIV both deterministic as well as stochastic models [11], [12] have been developed. These investigations have revealed that stochastic effects are essential for understanding viral latency [12] and mechanisms that regulate gene expression [11]. There also exist deterministic models of, for example, Epstein-Barr virus [13], and lambda bacteriophages [14]. With regard to HPV, there exist an epidemiological model [15], a spatial model of the infected epithelium [16], a deterministic model of the early promoter [10], a recent work related to a deterministic model of late promoter regulation [17] and a recent model describing the role of E8 promoter as a co-regulator of the early promoter [18]. To the best of our knowledge, our model is the first stochastic model of HPV gene regulation that takes into account gene regulation by the early promoter, post-transcriptional regulation through splicing and translational and post-translational regulation. The model allowed us to predict the dynamical behavior of the early promoter under different biological conditions. It also revealed complex dynamical behaviors that arise through the interconnection of basic regulatory modules [19] and showed the importance of modelling the splicing regulation to properly describe the HPV molecular biology as well as the intrinsic stochasticity in gene expression. Moreover, the number of infecting viruses turned out to be another important source of intrinsic stochasticity, showing a decrease in the gene expression noise as the number of active viral particle increases.

2. Results

In this section we present the main features of our model for gene regulation during the early phases of HPV infection. We develop a deterministic variant of the model, which describes the systems mean behavior, and a stochastic variant, which captures intrinsic fluctuations due the inherent randomness of biochemical reactions. We demonstrate the model’s consistency with known HPV biology. We then use both versions of the model to predict patterns of viral gene expression under various conditions. In particular, our stochastic simulations reveal complex stochastic patterns of gene expression that arise from the interconnection of basic regulatory modules that control gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level.

2.1. Model Description

The HPV “regulatory core” (Fig 1B–D), consists of three different basic modules. These are: 1) regulation at the early promoter (designed similarly as done in [20]), 2) post-transcriptional regulation by gene splicing and 3) transcriptional regulation of the SRSF1 splicing factor and its post-translational modification. The model applies to HPV-16, −18 and −31 high risk variants, which share basic properties [9]. Each regulatory module was designed to keep its structure as simple as possible. The modules were then coupled in a biologically consistent fashion.

2.1.1. Modeling early promoter regulation

Our model assumes that the early promoter consists of two binding sites that can bind either homodimers of E2 (DE2) or E1 and E2 multimeric complexes (E1E2). The interaction between E1 and E2 that controls HPV DNA replication is quite complex and results in formation of a E1E2 ternary complex and ultimately an E1 double-hexamer at the origin of replication [21], which regulates HPV DNA replication. However, the dynamic progression of this process is not well understood. Because our goal was to model HPV transcriptional regulation and not DNA replication, our model only considers formation of the E1-E2 heterodimer. There are five chemical states of the promoter denoted by PE,i, i = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 (Fig 2). The state PE,0 (no molecules bound to the promoter) accounts for basal transcription, the state PE,1 (a single DE2 molecule bound) accounts for positive feedback, the state PE,3 (a single E1E2 heterodimer bound) accounts for a strong positive feedback and states PE,2 (two DE2 dimers bound) and PE,4 (E1E2 and DE2 bound) account for negative feedback. The rate constants, ki’s, were mostly inferred from the literature (Supplementary Information). We assume that the basal level of expression of the primary transcript is controlled by endogenous regulation that is not explicitly considered in the model, as similarly done in other viral models [22].

Fig 2. State diagram for the early promoter (PE).

The promoter PE,i is regulated by the binding of DE2 and E1E2. State PE,0 (empty promoter) accounts for basal transcription, state PE,1 (single bound DE2) accounts for positive feedback, state PE,3 accounts for strong positive feedback and states PE,2 (two bound DE2) and PE,4 (E1E2 and DE2 bound) account for negative feedback. ki, i ϵ {2,4,6,8} are dissociation rate constants while the ki, i ϵ {1,3,5,7} are association rate constants.

The early promoter regulates the synthesis of the early primary transcript pM

| (1) |

where the pM synthesis rate SPM(PE,i) depends on the state of the promoter in the following way:

| (2) |

with the constraints spM,3 > spM,1 > spM,0 > spM,4 > spM,2 to account for positive feedback (spM,1 > spM,0 and spM,3 > spM,1) and negative feedback (spM,0 > spM,4 and spM,4 > spM,2). Expression from the PE,3 state is assumed repressed, but not to the level of the PE,4 state.

2.1.2. Modeling splicing regulation

The model assumes three splicing sites (Fig 1C): SA742, SA2709 and SA3358 that control the splicing of E1, E2 and the early genes (E4, E5, E6, E7), respectively. The early gene E8 is primarily controlled by other splicing sites that are not considered in our model [23]. The two splicing sites SA3358 and SA2709 are mutually exclusive [5], [9], which means they are not active at the same time. The model also assumes that the splicing enhancer factor SRSF1 enhances splicing of the remaining early genes and therefore diminishes creation of E1 and E2 transcripts. Thus, pre-mRNA molecules can be in four different states (Fig. 3): (i) the state pM which represents the pre-mRNA produced by the EP which is not undergoing splicing, or it is undergoing splicing through splicing sites we do not account for in this model; (ii) pM1 the state in which the splicing factors, bound to the pre-mRNA, favors splicing at SA742 with the consequent conversion to E1 transcript; (iii) pM2 the state in which the splicing factors, bound to the pre-mRNA, favors splicing at SA2709 with the consequent conversion to E2 transcript; (iv) pM3 the state in which the splicing factor SRSF1 is bound to the pre-mRNA enhancing splicing at SA3358 with the consequent conversion to the remaining early transcripts (i.e., mE4, mE5, mE6 and mE7). Splicing factors regulating the splicing at SA742 and SA2709 are currently not known and, therefore, not explicitly modeled. However, their dynamics is indirectly related to the SRSF1 dynamics as shown in (Fig. 3)

Fig 3. State diagram for the pM splicing.

pM is the pre-mRNA which is not undergoing splicing or it is undergoing splicing through splicing sites not accounted for in the model; pM1 is the pre-mRNA which is in a state where splicing occurs at SA742 site with the consequent conversion to E1 mRNA; pM2 is the pre-mRNA which is in a state where splicing occurs at SA2709 site with the consequent conversion to E2 mRNA; pM3 is the pre-mRNA which is in a state where splicing occurs at SA3358 site with the consequent conversion to the remaining early transcripts. The binding of SRSF1 splicing factor to the pM enhances the pM3 state occurrence. ki, i ϵ {10,12,14} are dissociation rate constants while the ki, i ϵ {9,11,13} are association rate constants.

The primary transcripts pM1 and pM2 are converted into E1 and E2 transcripts, respectively, according to the following reactions

| (3) |

| (4) |

where mE1 and mE2 are the E1 and E2 transcripts, respectively, and kmE1 and kmE2 are the corresponding rate constants.

pM3 can be converted into the remaining early transcripts mEi, i ∈ {4,5,6,7}

| (5) |

where a molecule of SRSF1 is released once a molecule of pM3 undergoes splicing. mEi are not explicitly modeled, because we are interested in the dynamics of E1 and E2.

Further equations for the protein translation and the multimolecular complexes formation are reported in the “Additional reactions” section of Materials and Methods.

2.1.3. Modeling SRSF1 promoter regulation

SRSF1 is present in very high abundances inside the cell (~ 106 - 107 [24]), presumably due to its multiple roles inside the nucleus and the cytoplasm. SRSF1 is involved in various forms of transcriptional regulation inside the nucleus and the cytoplasm, including mRNA synthesis, degradation, splicing enhancement and nuclear export and translation [25]. Moreover, it was shown to be an important oncoprotein and is over-expressed in different cancers [26].

While E2 is known to enhance expression of SRSF1, the specific details of this regulation are currently unknown. Therefore, to model SRSF1 regulation, we assumed a simple two-state promoter (PSR) structure (Fig 1D). The states are denoted by PSR,i, with i = 0,1. Positive regulation is exerted through E2 transactivation of an unknown transcription factor (TF) [27]. The biochemical reactions for the PSR promoter are given in Eq 6. State PSR,0 (TF not bound) accounts for basal transcription and state PSR,1 (TF bound) accounts for a positive regulation by E2.

| (6) |

The activation rate constant kSR,1(E2) is modeled using the following functional form:

| (7) |

where λ denotes the E2 concentration at which kSR,1(E2) is half its maximum value kSR,max. The Hill coefficient, n, determines the sharpness of the transition. Thus, the higher the concentration of E2, the higher the probability the promoter is in state PSR,1, in which the rate of SRSF1 transcription is increased. kSR,min is the minimum value assumed by kSR,1(E2) when E2 is zero copy number.

The biochemical reaction for the synthesis of SRSF1 transcript is

| (8) |

where mSRSF1 denotes the SRSF1 transcript and SmSRSF1(PSR,i) is the mSRSF1 synthesis rate dependent on the promoter state as follows:

| (9) |

That is, when E2 is bound to the promoter (PSR,1 state) mSRSF1 is produced at a rate sSR,1, otherwise mSRSF1 is produced with a rate sSR,0, where sSR,1 > sSR,0 accounts for the positive regulation induced by E2.

As found in [28], [25], the SRSF1 transcript and its cognate protein bind together forming a heterodimer. The degradation rate of this heterodimer is assumed to be greater than that of the SRSF1 transcript, thereby generating a negative feedback loop in terms of SRSF1 translational efficiency [25]. Such a negative feedback for SRSF1 expression is actually a positive feedback for E1 and E2 expression. Details of the reactions that govern protein translation and dimer formation are reported in the “Additional reactions” section of Materials and Methods.

2.1.4. Modeling multiple viruses in the cell

To model the presence of multiple copies of the infecting viruses, we have separately considered the stochastic contribution of each viral promoter and the corresponding mRNA synthesis reactions. We then assumed that the remaining biochemical equations occur in a common pool of transcripts and proteins. The range of the viral population number per cell, N, varies with the HPV strain and the lesion location. It was shown to be approximately 20–50 copies per cell for some HPV strains [29], such as HPV31 [30], while for other HPV strains it can range between 10–100 copies per cell [29] [31]. For most of the simulations, we assumed N = 10. Our choice of this number was driven by two considerations. First, we expect stochastic effects to be more significant at lower values of N, and, second, it is quite possible that not all viral particles are active at one time in a given cell. Finally, we note that we did not consider the control of N by E1 and E2, but explore the system behavior under different, but constant, values of N.

2.1.5. Parameter values

Table S1 (Supplementary Information) contains the model parameters for HPV-16. Most of the promoter binding rates were inferred from literature. pM synthesis rates were tuned to satisfy known biological constraints and to produce pM and mRNA copy numbers in ranges reported in the literature. Protein degradation rates were inferred from the literature or tuned to satisfy biological constraints. pM kinetics was fixed to stay in a range known from the literature and mRNA degradation rates were taken to be larger (5 to 10 fold increase as reported in Table S1, Supplemenatry information) than those for their corresponding proteins, reflecting the fact that RNA tends to be less stable than proteins [32], [33]. Splicing rates, as well as dimer and heterodimer formation/dissociation rates are unknown. For this reason, we explored the model’s response for different values of such parameters.

Further details for the calibration of key parameters are reported in the Supplementary Information. All model predictions reported in the following sections are obtained using the values listed in Table S1, unless otherwise specified.

2.2. Model behavior

2.2.1. Deterministic Behavior

To gain insight into the behavior of the model, we first computed the steady-state probabilities for the early promoter master equation (details in the Supplementary Information) as a function of the total abundance of E1 and E2 (TE = E1 + E2 + DE2 + E1E2). For a given amount of TE, the relative amounts of monomers and dimers were numerically computed by assuming these species were in equilibrium. Model predictions for the steady-state probabilities of the five states of the early promoter as a function of TE are shown in Fig 4. During early stages of the infection (low TE) the empty promoter (PE0 – blue curve) is the most probable state, leading to basal transcription. The probability of this state decreases rapidly as TE levels increase. At low abundance of TE, the positive feedback state (PE,1 – red curve) becomes the most probable promoter state, followed by the second positive feedback state (PE,3 – cyan). Which one of the two positive feedback states predominates depends on the relative values of the rate constants k1 and k5, which correspond to binding of the homodimer DE2 or heterodimer E1E2, respectively (Fig. 2). As the abundance of TE increases, the negative feedback states (PE,2 - green, and PE,4 - magenta) have the highest probability.

Fig 4. Steady-state probabilities for the early promoter.

Model predictions of the early promoter states as a function of the total copy number [CN] TE.

Our analysis shows that at the beginning of the infection the promoter undergoes basal transcription, followed by a positive feedback regime that increases E1 and E2, likely ensuring an infection reservoir with a viral DNA copy number between 10 and 100 copies. Finally, with the progression of the infection the negative feedback regime predominates likely stabilizing the viral copy number and the DNA replication efficiency.

We next used the equilibrium probabilities for the early promoter and similar approximations for the SRSF1 promoter and splicing regulation [34] to derive a set of ordinary differential equations that govern the time evolution of the mean concentrations of proteins and transcripts (Materials and Methods). We used the deterministic model to investigate the behavior of the initial phase of infection to gain insights into the mean response of the system and help undertand its stochastic behavior. Unless specified otherwise, we consider a total of 10 viral particles. We take the initial concentrations of viral proteins and transcripts to be zero. With these initial conditions, the early promoter is in the state PE,0 (i.e. basal transcription). SRSF1 protein and transcript concentrations start from non-zero initial conditions, because the splicing factor is present inside the cell prior to infection. The initial condition for SRSF1 was assumed to be a copy number of ~107 [24] and the SRSF1 promoter is in the state PSR,0.

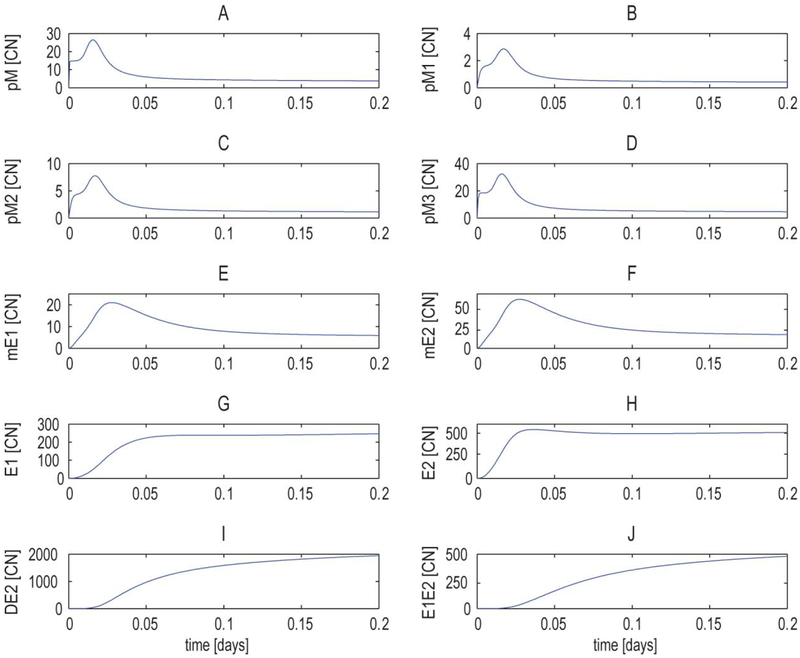

Most of the parameter sets we investigated produced qualitatively similar behavior (Fig. 5). Initial synthesis of the primary transcript pM occured rapidly with the concentration transiently reaching a level consistent with the synthesis rate of the empty promoter (i.e. the basal rate of transcription). As the primary transcript was spliced and the resulting mRNA translated into protein, the positive feedback states of the promoter became occupied, causing a larger increase in the concentration of pM. This increase eventually led to the negative feedback states of the promoter being favored, and a subsequent drop in the pM concentration. Interestingly, these dynamic changes in transcript levels were masked at the protein level, because the protein’s longer half life did not allow it to track changes in transcription levels (Fig. 5). The proteins E1 and E2 are delayed compared to the related transcripts, and homodimer, DE2, and heterodimer, E1E2, formation is delayed relative to the production of monomers.

Fig 5. Deterministic model behavior under nominal parameters.

Time series copy number (CN) for (A) pM primary transcript, (B) pM1 primary transcript, (C) pM2 primary transcript, (D) pM3 primary transcript, (E) mE1 transcript, (F) mE2 transcript, (G) E1 protein, (H) E2 protein, (I) DE2 homodimer, (J) E1E2 heterodimer.

Globally, the copy numbers of the chemical species are consistent with those found in the literature [35]. The initial peak shown in the pM, pMis (i = 1,2,3) and in the transcripts mE1 and mE2 might be connected with a need to guarantee a reservoir of E1 and E2 at the beginning of the infection. The initial peak and the steady state values of pM are modulated by the relative strength between positive and negative feedback loops (i.e., the ratio of the synthesis rates in the states of positive and negative feedback) as shown in Supplementary Information.

As specified in the “parameter values” section, several important parameters were fixed or inferred from the literature. However, the splicing parameters and the parameters regulating the dynamics of the DE2 dimer and E1E2 heterodimer are unknown. For this reason, we explored how these parameters, influence the system’s behavior. In particular, we investigated how crucial features (i.e., peak amplitude, steady state copy number, peak time and peak width) of the pMis are controlled as these parameters are varied.

An increase of k9 (the transition rate from pM to pM1) leads to an increase of pM1, pM2 and pM3 peak amplitudes and steady state levels (Fig. 6 A,B,E,F,I,J). This occurs because an increase of k9 leads to an increase of E1 and consequently of E1E2, which exerts a strong positive feedback on the promoter. k9 also acts as a threshold parameter of both pM2 peak amplitudes and steady states (Fig. 6 E,F). This is in line with known biology, because E1 and E2 are both required to efficiently control the DNA replication [7]. Interestingly, an increase of k9 leads to an increase of pM3 peak amplitudes and steady states, too, if k13 is high enough (Fig. 6 I,J).

Fig 6. Features of the model response for pM1, pM2 and pM3 primary transcripts under different parameter values of the splicing control.

Features of the model response are investigated for different values of k9 and k13 parameters, which are the transition rates between pM and pM1 and pM and pM3, respectively. k14, the transition rate between pM3 and pM, is also vaired being connected to k13 through the constraint k14 = k13*kD,SRSF1, where kD,SRSF1 is the SRSF1 dissociation constant (see Table S1, Supplementary Information). k13 axis, in all the subplots, is intended to be scaled by an order of magnitude of 10−7. (A) pM1 peak amplitude copy number [CN], (B) pM1 steady state [CN], (C) pM1 peak width [min], (D) pM1 peak time [min], (E) pM2 peak amplitude [CN], (F) pM2 steady state [CN], (G) pM2 peak width [min], (H) pM2 peak time [min], (I) pM3 peak amplitude [CN], (J) pM3 steady state [CN], (K) pM3 peak width [min], (L) pM3 peak time [min].

On the other hand, an increase of k13 (the transition rate from pM to pM3) leads to an increase of pM3 and a decrease of both pM1 and pM2 peak amplitudes and steady states (Fig. 6 A,B,E,F,I,J). This is due to mutual exclusive splicing between SA3358 splicing site, which produces pM3, and the other two SA2709 and SA742 splicing sites controlling mE2 and mE1, respectively.

The peak width of pM1, pM2 and pM3 predominantly depends on k13 for low values of k9 and it increases as k13 increases. This suggests that the splicing enhancer SRSF1 can modulate the peak width. The time of the pMi (i = 1,2,3) peaks increases with the increase of both k9 and k13.

Low values of k10 (the transition rate from pM1 to pM) and k11 (the transition rate from pM to pM2) guarantee higher level of both pM1 and pM3 but low levels of pM2 (Fig. 7 A,B,C) steady states. In particular, for low enough (10 fold decrease than the nominal value in Table S1, Supplementary Information) values of k11 (the transition rate from pM to pM2) the model predicts high abundance of pM and pM3, high abundance of pM1 and low levels of pM2 (Fig. 7D–G). This is because E2 is produced at a low level and consequently DE2 abundance is very low (Fig. 7 K,L). Hence the early promoter can work at a basal transcription regimen or under the only positive feedback induced by DE2 and E1E2, with the consequence that the peak in the pMis doesn’t appear anymore (Fig. 7 D,E,F,G). However, in this case E1E2 reaches a very high abundance and experiences a long delay (Fig. 7M). For these reasons the early promoter is subject to the strong positive feedback induced by the heterodimer E1E2 and consequently the steady state of pM1, pM3 and pM is strongly enhanced. This behavior could be related to the beginning of the genome amplification phase where the oncogenes are overexpressed at expense of E2 but at the same time the DNA replication, controlled by E1 and E2 produced by both the early and the late promoter, is enhanced [5].

Fig 7. Features of the model response for pM1, pM2 and pM3 primary transcripts under different parameter values of the splicing control and correspondent deterministic behavior.

Features of the model response are investigated for different values of k10 and k11 parameters, which are the transition rates between pM1 and pM and pM and pM2, respectively. (A) pM1 steady state copy number [CN], (B) pM2 steady state [CN], (C) pM3 steady state [CN]. Time series [CN] under a 10 fold decrease k11 parameter for (D) pM primary transcript, (E) pM1 primary transcript, (F) pM2 primary transcript, (G) pM3 primary transcript, (H) mE1 transcript, (I) mE2 transcript, (J) E1 protein, (K) E2 protein, (L) DE2 homodimer, (M) E1E2 heterodimer.

Model behavior as a function of other parameters (i.e., parameters related to dimer/heterodimer formation/dissociation and SRSF1 promoter control by E2) is straightforward to interpret, and hence presented in the Supplementary Information.

2.2.3. Stochastic effects in gene expression

While estimates for many of the model parameters appear in the literature, information on the splicing rates and SRSF1 promoter rates are not available. Promoter rate constants were inferred from literature but it is known that promoter activity changes with the HPV strain [36]. For these reasons, we chose to explore the effects of varying rate constants associated with the promoters and splicing regulation on stochasticity in gene expression. The parameter values used in the in silico experiments are reported in Table S1 (Supplementary Information), with the exception of the parameter being varied.

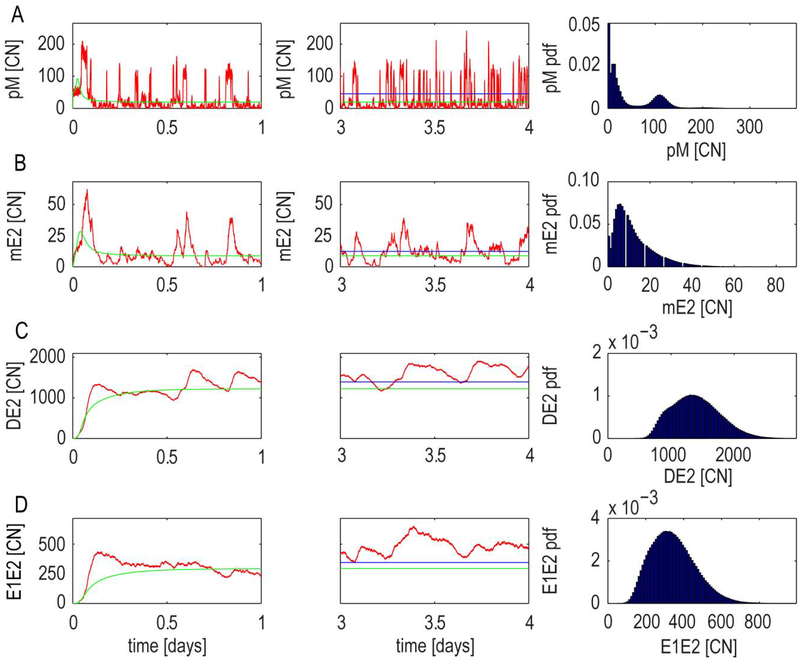

Our stochastic simulations revealed large fluctuations in the abundances of pMis, transcripts, proteins and dimers (Figs. 8, 9 show some crucial state variables with the remaining ones shown in the Supplementary Information).

Fig. 8. Stochastic model behavior for slow promoter and splicing fluctuations regime.

Promoter and splicing binding rates were decreased of 10 fold compared to the nominal values. Time series of copy number, [CN], and steady-state distributions for: (A) pM primary transcript, (B) mE2 transcript, (C) DE2 homodimer, (D) E1E2 heterodimer. The comparisons between the stochastic behavior (red) and the quasi-equilibrium approximation (green) are shown during the transient response (left panels) and steady state (middle panels). Numerical steady state mean (blue) is also shown during the steady state. The right panels show the steady state distributions. Mean and distributions were derived from 100 stochastic realizations run for a time length of 4 days.

Fig. 9. Stochastic model behavior for decreased SRSF1 promoter fluctuations.

SRSF1 promoter binding rates were decreased of 100 fold than the nominal value and the ratio between the SRSF1 synthesis rates between active and inactive promoter increased of 10 fold. Time series of copy number, [CN], and steady-state distributions for: (A) pM primary transcript, (B) mE2 transcript, (C) DE2 homodimer, (D) E1E2 heterodimer. The comparisons between the stochastic behavior (red) and the quasi-equilibrium approximation (green) are shown during the transient response (left panels) and steady state (middle panesl). Numerical steady state mean (blue) is also shown during the steady state. The right panels show the steady state distributions. Mean and distributions were derived from 100 stochastic realizations run for a time length of 4 days.

In the slow (10 fold decrease in the nominal values in Table S1, Supplemenatry Information) promoter and splicing fluctuation regimes, the pM shows fast and large fluctuations with a trimodal distribution (Fig. 8A). Fluctuations in the abundance of pMis (Fig. 8A and Supplementary Information) and transcripts mE2 (Fig. 8B) and mE1 (Supplementary Information) show bursts of high expression compared to the mean (Fig. 8 and Supplemenatry Information blue line middle panel) and the quasi-equilibrium differs from the steady state mean of pM (Fig. 8A middle panel). Dimer DE2 and heterodimer E1E2 strongly deviate from the quasi equilibrium and from the mean (Fig. 8 C,D left and middle panel), hence they strongly affect the interplay between positive and negative feedbacks at the promoter level. This allows the production of bursts in the pMis and transcripts expression in the case where the positive feedback is sufficiently strong. In particular, the trimodal distribution in the pM expression is due to slow fluctuations at the early promoter. The early promoter is modelled as a five state markov chain, and hence potentially capable of a multimodal distribution with peaks corresponding to each of the five states. The slower dynamics of DE2 homodimers and E1E2 heterodimers allows a stochastic interplay between positive and negative feedbacks that drive transistions between these states.

Under slower SRSF1 promoter fluctuations (100 fold decrease from the nominal values in Table S1, Supplementary Information) and a 10 fold increase in the ratio of SRSF1 synthesis rates (sSR,0 and sSR,1, eq. 9) in the active and inactive promoter states, we do not observe clear bursts in the transcripts anymore (since the early promoter fluctuations are faster under the nominal promoter rates in Table S1, Supplementary Information). However, the system reveals a strong stochasticity characterized by strong excursions of the pre-mRNAs, transcripts and dimers. In this case, the quasi-equilibrium approximation and the means computed from the simulations approach each other (Fig. 9 B,C,D). This suggests that the time scale of the early promoter dynamics is quite fast and the quasi-equilbrium approximation is valid.

It is also noteworthy that, under this parameter set, it is straightforward to show how SRSF1 is capable of modulating the amplitude of pre-mRNAs (Fig. 10). In particular, the pM3 abundance reflects the SRSF1 pattern, while pM, pM1 and pM2 are opposite being silenced by SRSF1 (Fig. 10). It is noteworthy that the SRSF1 splicing factor strongly affects even the dimer DE2 and heterodimer E1E2, hence indirectly the feedback transcriptional regulation (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. SRSF1 amplitude modulation.

Time series of copy number, [CN], and quasi-equilibrium for SRSF1 promoter fluctuations decreased of 100 fold than the nominal value and the ratio between the SRSF1 synthesis rates between active and inactive promoter increased of 10 fold. (A) pM primary transcript, (B) pM1 primary transcript, (C) pM2 primary transcript, (D) pM3 primary transcript, (E) DE2 homodimer, (F) SRSF1 protein. The stochastic behavior is shown in red and the quasi-equilibrium approximation is shown in blue.

Promoter and splicing regulation can also affect the intrinsic noise. We quantified its steady state strength in terms of the coefficient of variation CV (see Materials and Methods). Our analysis shows that an increase of the early promoter binding rates magnitude fEP (scale factor for the promoter binding rates, defined as , where ki is a nominal rate constant of the early promoter markov chain in Fig. 2 and is its rescaled version) (i.e., increase of promoter fluctuations) lead to a decrease of the noise strength for most of the chemical species such as mE2 and mE1 (Fig. 11 C and Supplementary Information), as expected. However, unexpectedly, the noise strength of the pMis increases with fEP (Fig. 11 A,B,C,D).

Fig. 11. Noise strength.

Coefficient of variation (CV) of some interesting chemical species under variation of the magnitude of the promoter binding rates (proportional to fEP), splicing rates (proportional to fSS) and SRSF1 synthesis rates (proportional to fSRSF1). CV as a function of fEP for: (A) pM1 primary transcript, (B) pM2 primary transcript, (C) mE1 transcript, (D) mE2 transcript. CV as a function of fSS for: (E) pM primary transcript, (F) pM1 primary transcript, (G) pM2 primary transcript, (H) pM3 primary transcript. CV as a function of fSRSF1 for: (I) pM primary transcript, (J) pM1 primary transcript, (K) pM2 primary transcript, (L) pM3 primary transcript.

An increase of the splicing binding rates magnitude fSS (scale factor for the splicing rates, defined as , where ki is a nominal rate constant of the splicing markov chain in Fig. 3 and is its rescaled version) (i.e., increase of splicing fluctuations) leads to a decrease of the noise for most of the chemical species (Fig. 11 F,G and Supplementary Information) but, also leads to an increase of the noise of pM and pM3 (Fig. 11 E,H). Interestingly, an increase of the SRSF1 synthesis rate (proportional to fSRSF1 (scale factor for the SRSF1 synthesis rates, defined as , where sSR,i is a nominal rate constant of the SRSF1 synthesis rate defined in eq. (9) and is its rescaled version)) selectively decreases pM3 noise (being pM3 induced by SRSF1) (Fig. 11 H) and increases all the other pMis and chemical species (Fig. 11 I,J,K,L and Supplementary Information), with the exception to SRSF1 and mSRSF1/SRSF1 (Supplementary Information). This suggests that the splicing regulation is capable of selectively modulating the intrinsic noise of the chemical species that are alternatively spliced.

In conclusion, our results (Fig. 8–11) demonstrate the importance of stochastic effects in HPV gene expression that are not captured by purely deterministic models. We have shown how through the interplay of positive and negative regulation at the promoter, gene expression can show bursting behavior and deviate from both the quasi-equilibrium and the steady state mean. This analysis also reveals that splicing regulation represents another important source of stochasticity in gene regulation. Moreover, the interconnection of different regulatory modules lead to interesting and unexpected results in terms of noise filtering/amplification, besides showing complex behaviors that are not permissible by modeling just the transcriptional regulation, consistent with [19].

2.2.4. The role of promoter and splicing regulation on bursting

The combination of positive and negative feedback at the early promoter and splicing regulation generates stochastic bursts of gene expression. To characterize the role of early promoter regulation and splicing on bursting, we used slow promoter fluctuations (the nominal values were reduced by a factor of 0.01) that generate well defined bursts. We next identified bursts in mE2 abundances (see Materials and Methods for details) and computed the mean values for the frequency, duration and amplitude of the bursts as a function of fEP, fSS,, R (ratio between positive and negative feedback synthesis rates defined in eq. (2)), fSRSF1 and N (number of viruses in the cell). All results were obtained by averaging over 100 realizations of the process run for a length of time equal to 7 days.

Our results show that as the promoter binding rates were increased (i.e., larger fEP) the burst frequency increased, whereas the burst duration and amplitude decreased (Fig. 12 A,B,C). This is because faster promoter fluctuations generate higher molecular abundances, and consequently, stronger negative feedback, acting on the early promoter. Our results also show that the burst frequency and amplitude increase as fSS is increased, while the duration of the bursts decreases (Fig. 12 G,H,I). Moreover, increasing the SRSF1 synthesis rate (i.e., larger fSRSF1) decreases the bursts frequency and amplitude and increases burst duration (Fig. 12 J,K,L). Finally, increasing the relative strength, R, between opposing feedback loops, increases the burst amplitude, but has non-monotonic effects on the burst frequency and duration (Fig. 12 D,E,F). The burst frequency increases and the burst duration decreases until around R = 10 at which point these trends are reversed.

Fig 12. Promoter and splicing control of bursts amplitude and frequency.

Bursts features (frequency, duration and amplitude) of mE2 transcript are shown for different magnitudes of promoter binding rates (proportional to fEP), splicing rates (proportional to fSS), SRSF1 synthesis rates (proportional to fSRSF1) and different ratios (R) between positive and negative feedback strengths. Bursts frequency (left panels), bursts duration (middle panels) and bursts amplitude (right panels). Bursts features as function of (A,B,C) fEP, (D,E,F) R, (G,H,I) fSS, (J,K,L) fSRSF1,.

In conclusion, our model reveals that the burst amplitude is primarily regulated at early promoter with splicing playing less of a role. The promoter also controls the global frequency and duration of the transcripts, as shown in Fig. 12 A,B. On the other hand, changes in the parameters related to splicing can either increase or decreas the burst amplitude and frequency (as shown in Fig. 12 G,I). Interestingly, the burst frequency and duration are affected by the synthesis rate of the SRSF1 splicing factor (as shown in Fig. 12 J,K).

2.2.5. Fluctuations in virus copy number contribute to variability in gene expression

We next investigated how the number of viral particles, N, infecting a cell contributes to variability in gene expression. As expected increasing N produced a decrease in the coefficient of variation for pM2 pre-mRNA and mE2 transcripts (Fig. 13A and B). Including multiple viruses in a sinle cell still generated bursts of gene expression. Interestingly, in these regimes, larger N increased the burst frequency and amplitude (Fig. 13 C and E) but lowered the burst duration (Fig. 13 D).

Fig 13. Noise and bursts features controlled by the number of viruses N.

Coefficient of variation of (A) pM2 primary transcript and (B) mE2 transcript as function of N. (C-E) Burst frequency, duration and amplitude of mE2 transcript as a function of N.

3. Discussion

We developed a stochastic model for gene regulation at the HPV early promoter to investigate the sources and consequences of fluctuation in gene expression. The starting point for our model was our previously published deterministic model [10]. We extended this latter to include a more detailed model of early promoter regulation and more details for splicing by the SRSF1 splicing factor. We then recast the biochemical reactions that comprise the system as stochastic processes. A novel feature of our model is that it accounts for stochastic effects from RNA splicing. Our model captures several coupled regulatory mechanisms that act at multiple levels (e.g., transcription, translation, splicing) to form a network capable of generating complex patterns of gene expression. We first characterized the individual regulatory modules in the network, and then coupled them to form a functioning network. Of particular note, our investigations revealed that post-transcriptional regulation trough splicing allows the system to perform stochastic amplitude modulation of the pre-mRNAs and, in turn, of the transcripts, proteins and homodimers/heterodimers.

We were able to infer values for many model parameters from measurements in the literature, while others were calibrated, so that the model produced results consistent with known biology. Moreover, the model qualitatively predicted biological features reported in the literature, including initial peaks in E1 and E2 transcript copy number. The initial peaks suggest that high level in E1 and E2 at the beginning of the infection facilitate DNA amplification after infection [37].

The model generated molecular abundances for transcripts and unspliced transcripts and proteins that are within the ranges and constraints reported/inferred in the literature [36], [35], [38], [39], [40]. In particular E1 and E2 mRNAs were set to a level similar to those found in undifferentiated cells and cells at the beginning of differentiation [40].

While estimates for many of the model parameters could be found or calibrated from the literature, information on the splicing rates, as well as the association and dissociation rates of homodimers and heterodimers, are not available. Promoter rate constants were inferred from literature but it is known that promoter activity can change with HPV strain [36]. For these reasons, we chose to explore the effects of varying parameters associated with promoter and splicing regulation to investigate their effect on the HPV gene expression.

Our results demonstrated that both promoter regulation and splicing can strongly affect stochasticity of HPV gene expression. Transcript levels showed fast and large stochastic excursions, while the protein monomers and complexes showed slower stochastic fluctuations. Interestingly, for many parameter sets tested, the mean behavior of the system computed from averaging stochastic simulations differed from the solutions of rate equations derived under the quasi-equilibrium approximation. Moreover, the combination of negative and positive feedback loops, in combination with splicing fluctuations, generated bursts of transcription, similar to the behavior found in excitable systems. The relative strengths of the early promoter positive and negative feedback loops are the key determinant of the burst amplitude, while both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by splicing affect the bursts frequency and duration. The rates that govern how the promoter, splicing factor and mRNA interact strongly affect the burst frequency. The difference between mean and the deterministic behavior is in line with other recent findings [41], in which it was shown that an increase burst size generates larger differences between the stochastic and deterministic means.

Previously, it was shown that the HIV promoter controls burst size [42] but no effect on burst frequency was found. In our model, we showed that the bursts frequency can be modulated by regulation at the promoter. However, promoter regulation has a larger effect on burst amplitude. On the other hand, splicing regulation can affect burst frequency and duration through the the SRSF1 splicing factor. These observations are noteworthy given frequency modulation in gene regulation has received considerable attention in recent years [43], [44]. Frequency and amplitude control by splicing may have important biological implications for the HPV life cycle. It was recently demonstrated that E8 co-regulation of the early promoter provides a mechanism to regulate DNA replication by diminishing the total noise of E1 and E2 [23], [18]. However, bursty gene expression could provide another mechanism for regulating E1 and E2 through a frequency modulation in a way similarly shown in [43]. Alternatively, a transcriptional bursting regime could also be interpreted as generating high variability in early gene expression, which may influence the viral-fate decision between active replication and latent behavior, as similarly found for HIV [42].

Also noteworthy is the ability of the SRSF1 splicing factor to perform stochastic amplitude modulation (Fig. 11), (similar to what is known in telecommunication [45]), of the un-spliced transcripts and consequently of all the other chemical species. Moreover, SRSF1 can also modulate the burst frequency of the transcripts (Fig. 12), hence adjusting the priority to produce mE1 and mE2. Therefore, our results show the importance of modeling post-transcriptional regulation as another source of intrinsic stochasticity in gene networks. In particular, complex and important regulatory patterns can be achieved [19] when considering splicing regulation by splicing enhancers (e.g. SRSF1) and silencers [5].

At the beginning of the infection the number, N, of HPVs inside a single cell are modulated by E1 and E2 and are kept between 20 and 50 per cell in some lesions and HPV strains [29], such as HPV31 [30], and between 10 and 100 per cell for other strains [31]. Interestingly, increasing the number of viruses in the cell increases burst frequency and amplitude, while lowering stochastic noise. This shows how the number of viruses infecting a cell, is a third important source of stochasticity and might bias stochastic decision making and influence the outcome of the infection, as found for lambda phages [46].

The development of any model is an iterative process requiring additional experimental data to validate the model and to indicate where and how to refine it. Future development of our model will follow two lines of investigation. First, we plan to extend the model to include the whole HPV genome and to importantly expand the complex and still elusive splicing regulation to a more complete state. This will allow us to address oncogene expression and late promoter regulation and their effects on the cell differentiation program. Recently, the importance of considering control of DNA replication as an additional source of stochasticity in gene expression was shown [47]. We demonstrated the importance of the number of infecting viral particles, N, in modulating stochasticity and for this reason we are planning to upgrade the model by also considering the E1 and E2 modulation of the DNA replication, by the early and late promoters. We expect our expanded model will provide insights into how oncogenes influence the proliferation/differentiation decision [5] and progression through the pre-cancerous stages (CIN-I,-II,-III) [1]. Second, we plan to validate the model through a direct comparison with experimental data for the abundances of viral proteins, transcripts and splicing factors, during the HPV life cycle.

Our ultimate goal is to upgrade the model with the novel framework of physiologically based pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics models [48], [49], to investigate antiviral pharmacokinetics and, in particular, pharmacodynamics at a cellular level and potentially design novel antiviral therapies. Several proposed antiviral therapies exist in literature and range from targeting E1 and E2 [2], to interfering with viral replication, to down-regulating oncogenes or stopping the production of the viral capsid proteins [50]. However, the development of an efficient working antiviral therapy still represents an important open challenge. Given the complex regulatory structure of the network that controls HPV gene expression, an interesting approach might be to simultaneously target different control levels, including key splicing factors, such as SRSF1, as suggested in recent works [5], [51]. Throughout the development process a model that reliably predicts patterns of gene expression would be of great value.

3.1. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study represents a first attempt to stochastically model early gene regulation by HPV. Our model reproduced known biological features and showed the importance of including intrinsic stochasticity to properly understand HPV gene expression. The interplay between positive and negative feedback regulation affects HPV gene expression by triggering a bursty response, which could influence viral decision making and play an important role in the outcome of the infection. In particular, bursts in gene expression could affect DNA replication and switch the viral behavior between active replication and viral latency. We also demonstrated the importance including splicing regulation as another source of stochasticity, and highlighted its role in modulating burst amplitude and frequency. We finally showed the importance to consider the number of viral particles as a third source of stochasticity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Additional reactions

Additional biochemical reactions describe translation, homodimer and heterodimer formation and dissociation and degradation of chemical species.

The transcripts are translated into proteins

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

where E1, E2 and SRSF1 are the proteins translated from the transcripts mE1, mE2 and mSRSF1, respectively. The translation rates for proteins are proportional to their transcripts through the constants kE1, kE2 and kSRSF1, respectively.

E1 and E2 form the heterodimer E1E2 and E2 forms the homodimer DE2. Moreover, mSRSF1 and SRSF1 form a heterodimer mSRSF1/SRSF1 to account for the negative feedback on SRSF1 in terms of translational efficiency:

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

where kDE2.f, kDE2,r are the forward and reverse rate constants for the formation of the dimer DE2. kE1E2,f and kE1E2,r are the forward and reverse rate constants for the formation of the heterodimer E1E2. kfms and krms are the association and dissociation rate constants for the heterodimer mSRSF1/SRSF1, respectively.

Each chemical species undergo degradation

| (16) |

where X is the generic chemical species.

In general, unless differently specified, the degradations of the transcripts were assumed faster than their proteins counterparts [32], [33]. The constraint δmSRSF1/SRSF1 > δmSRSF1 were assumed to account for the negative feedback of SRSF1 in terms of translational efficiency. To account for the stabilization effect mediated by E1 on E2, we considered the constraint δE1E2 < δE2 [8].

The rate δpM accounts for both the degradation of the unspliced pM, as well as the pM conversion into transcripts through splicing mechanisms that weren’t considered in the current model.

4.2. Stochastic Simulations

The Master Equation of the whole system is complex and cannot be solved analytically. The simulations shown in the Results section were performed using the Gillespie algorithm. Simplified Master Equations for the early promoter and SRSF1 promoter were also considered to predict the probabilities for the promoters as functions of the chemical species that affect these states (details in Supplementary Information).

4.3. Quasi-Equilibrium approximation

A set of ordinary differential equations for the mean abundances of the chemical species can be derived in terms of quasi-equilibrium approximations assuming fast fluctuations for the promoters and large numbers for the chemical species. Details of the derivation are given in the Supplementary Information.

4.4. Bursts analysis

We investigated the role of key parameters of the splicing and promoters regulation modules on bursting behavior. For each condition we evaluated 4 different values of the parameter of interest and for each of these values we generated a set of 100 in silico realizations. Bursts were identified by thresholding the stochastic time series. For each set, an optimal threshold was estimated by minimizing an error cost function defined as the sum of false positives and false negatives. Once the bursts were identified, metrics such as the average inter-burst interval, burst duration and burst amplitude were computed.

4.5. Noise strength

In this work we measure the steady state noise strength of the general chemical species, X, in terms of the coefficient of variation (CV) [52], defined as , where <X> and σ(X) are the mean and standard deviation of the X [CN], respectively. The higher the CV, the higher the stochastic noise affecting the gene expression of X [52].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Feedback regulation at the promoter controls amplitude and frequency of transcriptional bursting.

RNA splicing regulates transcriptional burst frequency.

Integrated feedback regulation and splicing reveals complex stochastic patterns of gene expression.

Splicing and virus copy number are sources of stochasticity in gene expression.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH Grant R35GM127145.

References

- 1.Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG, Stoler M, Broker TR, et al. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl.5):F55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard H-U. Gene expression of genital human papillomaviruses and considerations on potential antiviral approaches. Antivir Ther. 2002. December 1;7(4):219–37. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobo F Human Papillomavirus Infections from the laboratory to clinical practice. 1st ed Woodhead Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozbun MA. Human papillomavirus type 31b infection of human keratinocytes and the onset of early transcription. J Virol. 2002;76(22):11291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson C, Schwartz S. Regulation of human papillomavirus gene expression by splicing and polyadenylation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013. March 11;11(4):239–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller M, Demeret C. The HPV E2-Host Protein-Protein Interactions: A Complex Hijacking of the Cellular Network. Open Virol J. 2012. December 28;6(1):173–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard H-U. Regulatory elements in the viral genome. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King LE, Dornan ES, Donaldson MM, Morgan IM. Human papillomavirus 16 E2 stability and transcriptional activation is enhanced by E1 via a direct protein-protein interaction. Virology. 2011;414(1):26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz S Papillomavirus transcripts and posttranscriptional regulation. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giaretta A, Di Camillo B, Barzon L, Toffolo GM. Modeling HPV Early Promoter Regulation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:6493–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razooky BS, Weinberger LS. Mapping the architecture of the HIV-1 Tat circuit: A decision-making circuit that lacks bistability and exploits stochastic noise. Methods. 2011;53(1):68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberger LS, Burnett JC, Toettcher JE, Arkin AP, Schaffer DV. Stochastic gene expression in a lentiviral positive-feedback loop: HIV-1 Tat fluctuations drive phenotypic diversity. Cell. 2005;122(2):169–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner M, Ernberg I, Zou J, Almqvist J, Aurell E. Epstein-Barr virus latency switch in human B-cells: a physico-chemical model. BMC Syst Biol. 2007;31;1:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santillán M, Mackey MC. Why the Lysogenic State of Phage λ Is so Stable: A Mathematical Modeling Approach. Biophys J. 2004;86(1 I):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SL, Tameru AM. A Mathematical Model of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in the United States and its Impact on Cervical Cancer. J Cancer. 2012. January;3:262–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orlando PA, Brown JS, Gatenby RA, Guliano AR. The ecology of human papillomavirus-induced epithelial lesions and the role of somatic evolution in their progression. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(3):394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giaretta A, Toffolo GM. Modeling HPV Late Promoter Regulation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2018;2386–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giaretta A Stochastic Modeling of the Co-Regulation between Early and E8 Promoters in Human Papillomavirus. ConfProc IEEE Eng MEd Biol Soc. 2018;8:5026–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jr Szekely T, Burrage K. Stochastic simulation in systems biology. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2014;12(20–21):14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guido NJ, Wang X, Adalsteinsson D, Mcmillen D, Hasty J, Cantor CR, Elston TC, Collins JJ. A bottom-up approach to gene regulation. Nature. 2006. February 16;439(7078):856–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koegel LK, Vernon T, Koegel RL, Koegel BL, Paullin AW. NIH Public Access. 2014;14(4):220–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner M, Ernberg I, Zou J, Almqvist J, Aurell E. Epstein-Barr virus latency switch in human B-cells: a physico-chemical model. BMC Syst Biol. 31;1:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreer M, van de Poel S, Stubenrauch F. Control of viral replication and transcription by the papillomavirus E8Ê2 protein. Virus Res. 2017;231:96–102. Available from: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanamura A, Caceres J, Mayeda A, Franza BJ, Krainer AR. Regulated tissue-specific expression of antagonistic pre-mRNA splicing factors. RNA. 1998;4(4):430–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun S, Zhang Z, Sinha R, Karni R, Krainer AR. SF2 / ASF autoregulation involves multiple layers of post-transcriptional and translational control. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(3):306–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonçalves V, Jordan P. Posttranscriptional Regulation of Splicing Factor SRSF1 and Its Role in Cancer Cell Biology. 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mole S, Milligan SG, Graham SV. Human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein transcriptionally activates the promoter of a key cellular splicing factor, SF2/ASF. J Virol. 2009;83(1):357–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanford JR, Coutinho P, Hackett JA, Wang X, Ranahan W, Caceres JF. Identification of nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNA targets for the shuttling protein SF2/ASF. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan IM, Dinardo LJ, Windle B. Integration of human papillomavirus genomes in head and neck cancer: Is it time to consider a paradigm shift. Viruses. 2017;9(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubert WG, Laimins LA. Human Papillomavirus Type 31 Replication Modes during the Early Phases of the Viral Life Cycle Depend on Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation of E1 and E2 Expression. 2002;76(5):2263–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straub E, Fertey J, Dreer M, Iftner T, Stubenrauch F. Characterization of the Human Papillomavirus 16 E8 Promoter. J Virol. 2015;89(14):7304–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25948744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein JA, Khodursky AB, Lin P, Lin-chao S, Cohen SN. Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays. 2002; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cambridge SB, Gnad F, Nguyen C, Bermejo JL, Kr M, Mann M. Systems-wide Proteomic Analysis in Mammalian Cells Reveals Conserved, Functional Protein Turnover. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(12):5275–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kepler TB, Elston TC. Stochasticity in transcriptional regulation: origins, consequences, and mathematical representations. Biophys J. 2001;81(6):3116–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt M, Pawlita M. The HPV transcriptome in HPV16 positive cell lines. Mol Cell Probes [Internet]. 2011;25(2–3):108–13. Available from: 10.1016/j.mcp.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou SY, Wu S, Chiang C. Transcriptional Activity among High and Low Risk Human Papillomavirus E2 Proteins Correlates with E2 DNA Binding *. 2002;277(47):45619–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurg R The Role of E2 Proteins in Papillomavirus DNA Replication. In: DNA Replication-Current Advances. intechopen; 2011. p. 613–38. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang-Johanning F, Lu DW, Wang Y, Johnson MR, Johanning GL. Quantitation of human papillomavirus 16 E6 and E7 DNA and RNA in residual material from thinprep papanicolaou tests using real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis. Cancer. 2002;94(8):2199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin BY, Makhov AM, Griffith JD, Broker TR, Chow LT. Chaperone proteins abrogate inhibition of the human papillomavirus (HPV) E1 replicative helicase by the HPV E2 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(18):6592–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozbun MA, Meyers C. Human Papillomavirus Type 31b E1 and E2 Transcript Expression Correlates with Vegetative Viral Genome Amplification. Virology. 1998;248(2):218–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramaswamy R, González-Segredo N, Sbalzarini IF, Grima R. Discreteness-induced concentration inversion in mesoscopic chemical systems. Nat Commun. 2012;3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skupsky R, Burnett JC, Foley JE, Schaffer DV., Arkin AP. HIV promoter integration site primarily modulates transcriptional burst size rather than frequency. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai L, Dalal CK, Elowitz MB. Frequency-modulated nuclear localization bursts coordinate gene regulation. Nature. 2008;455(7212):485–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dalal CK, Cai L, Lin Y, Rahbar K, Elowitz MB. Pulsatile Dynamics in the Yeast Proteome. Curr Biol. 2014;24(18):2189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benvenuto N, Zorzi M. Principles of Communications Networks and Systems. John Wiley; Benvenuto N, Zorzi M, editors. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balázsi G, Van Oudenaarden A, Collins JJ. Cellular decision making and biological noise: From microbes to mammals. Cell. 2011;144(6):910–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson JR, Cole JA, Fei J, Ha T, Luthey-Schulten ZA. Effects of DNA replication on mRNA noise. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(52):15886–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones HM, Chen Y, Gibson C, Heimbach T, Parrott N, Peters SA, et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling in drug discovery and development: a pharmaceutical industry perspective. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(3):247–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giaretta A, Rocca B, Di Camillo B, Toffolo GM, Patrono C. In Silico Modeling of the Antiplatelet Pharmacodynamics of Low-dose Aspirin in Health and Disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fradet-Turcotte A, Archambault J. Recent advances in the search for antiviral agents against human papillomaviruses. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(4):431–451. Review. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hernandez-Lopez H, Graham S. Alternative splicing in tumour viruses: a therapeutic target? Biochem J. 2012;445(2):145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh A, Soltani M. Quantifying intrinsic and extrinsic variability in stochastic gene expression models. PLoS One. 2013;8(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.