Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is one of the main complications in stage IV gastric cancer patients. This condition is usually managed by gastrojejunostomy (GJ). However, gastric partitioning (GP) has been described as an alternative to overcoming possible drawbacks of GJ, such as delayed gastric emptying and tumor bleeding.

AIM

To compare the outcomes of patients who underwent GP and GJ for malignant GOO.

METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed 60 patients who underwent palliative gastric bypass for unresectable distal gastric cancer with GOO from 2009 to 2018. Baseline clinicopathological characteristics including age, nutritional status, body mass index, and performance status were evaluated. Obstructive symptoms were graded according to GOO score (GOOS). Surgical outcomes evaluated included duration of the procedure, surgical complications, mortality, and length of hospital stay. Acceptance of oral diet after the procedure, weight gain, and overall survival were the long-term outcomes evaluated.

RESULTS

GP was performed in 30 patients and conventional GJ in the other 30 patients. The mean follow-up was 9.2 mo. Forty-nine (81.6%) patients died during that period. All variables were similar between groups, with the exception of worse performance status in GP patients. The mean operative time was higher in the GP group (161.2 vs 85.2 min, P < 0.001). There were no differences in postoperative complications and surgical mortality between groups. The median overall survival was 7 and 8.4 mo for the GP and GJ groups, respectively (P = 0.610). The oral acceptance of soft solids (GOOS 2) and low residue or full diet (GOOS 3) were reached by 28 (93.3%) GP patients and 22 (75.9%) GJ patients (P = 0.080). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that GOOS 2 and GOOS 3 were the main prognostic factors for survival (hazard ratio: 8.90, 95% confidence interval: 3.38-23.43, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION

GP is a safe and effective procedure to treat GOO. Compared to GJ, it provides similar surgical outcomes with a trend to better solid diet acceptance by patients.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Gastric outlet obstruction, Palliative surgery, Gastrojejunostomy, Gastric cancer

Core tip: Gastric partitioning associated with gastrojejunostomy has been employed for the treatment of malignant obstruction. The partitioning creates two separated gastric chambers that may improve gastric emptying, decrease tumor bleeding, and improve survival. We analyzed retrospective data from our center and found that partitioning was as safe and effective as traditional gastrojejunostomy. Postoperative complications and survival were similar between the groups. Acceptance of soft and full diet after the procedure was the most important prognostic variable and was more common after gastric partitioning. A prospective randomized trial is ongoing to further analyze this issue.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. Surgical resection of the tumor with D2 lymphadenectomy is the indicated standard curative treatment[2]. Unfortunately, many patients initially present with advanced disease at the time of diagnosis without the possibility of curative resection. The frequency of patients with clinical stage IV varies according to each country and may reach up to 40% of cases[3-5].

Despite the dismal prognosis, many stage IV GC patients develop complications during the course of disease that require palliative procedures. Among these complications, the following stand out: Tumor bleeding, refractory ascites, intestinal obstruction, and gastric outlet obstruction (GOO).

The incidence of GOO ranges between 5% and 14.9% in patients with distal GC. Palliative resection of the tumor is the procedure of choice in cases of resectable lesions and limited metastatic disease, and in patients with favorable clinical conditions[6].

However, many of these tumors are considered unresectable due to local invasion of adjacent structures or due to patients’ unfavorable clinical conditions. Surgical bypass or endoscopic stents are options to restore the gastrointestinal continuity. Endoscopic stents are less invasive and can be deployed out of the operating room. However, concerns regarding its long-term effectiveness still grants an important role for surgery[7,8].

The most traditional surgery performed is gastrojejunostomy (GJ). The procedure is simple and can be accomplished by laparoscopy with low morbidity. However, delayed gastric emptying (DGE) is one of the main postoperative complications, with an incidence that varies between 10% and 26%[9].

In this context, gastric partitioning (GP) associated with GJ, also known as GP, has been considered an option for the treatment of malignant GOO. Initially, it was described in 1925 for complex gastroduodenal ulcers[10]. Currently, is considered a palliative surgery for GOO by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association guidelines[2].

Our institution has used GP for the past 10 years in such cases. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of patients who underwent GP and GJ for malignant GOO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A retrospective review of all gastric adenocarcinoma patients who underwent any palliative surgical bypass from 2009 to 2018 was performed from a prospectively collected database.

Inclusion criteria were: Irresectable distal gastric tumor; the presence of obstructive symptoms; and life expectancy superior to 2 mo. Patients with proximal gastric tumors, tumors amenable to palliative resection and associated with small bowel obstruction were excluded.

Clinicopathological characteristics were evaluated as well as laboratory tests to assess nutritional status. Karnofsky performance score (KPS) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale were used to assign performance status. Tumor spread was evaluated by the presence of distant metastasis and carcinomatosis. Obstructive symptoms were graded according to the GOO score (GOOS) as follows: 0 = no oral intake, 1 = liquids only, 2 = soft solids, 3 = low residue or full diet[11]. Patient’s weight in kilograms and body mass index (BMI) were measured prior to surgery and after 30 and 90 d. Maximum weight after surgery and last weight recorded before death were also evaluated.

Postoperative complications were graded according to Clavien-Dindo’s classification[12]. Major complications were considered Clavien III-IV-V. Surgical mortality was defined as death within 30 d after surgery or during hospital stay. Survival was evaluated after 30 and 90 d and during follow-up.

Due to limited life expectancy and fragility of the patients, there was no standard postoperative follow-up schedule. An absence in consultations for more than 12 mo was considered loss of follow-up.

Surgical technique

Briefly, GP was performed as follows. Upon confirmation that the tumor was unresectable, the lesser sac was accessed, and the posterior gastric wall was inspected to confirm that there was a tumor-free area for anastomosis. For GP, a point located at least 5 cm proximal to the tumor along the gastric curvatures was chosen. Faucher’s tube (32Fr) was positioned along the lesser curvature to ensure a small conduit between the two gastric chambers created by partitioning. It enabled subsequent endoscopic observation of the bypassed tumor. The stomach was partitioned through mechanical linear stapler from the greater curvature towards the Faucher’s tube along the lesser curvature. A side to side GJ, 30 cm from the ligament of Treitz, was performed in the proximal part of the stomach (Figure 1). In some cases, Roux-en-Y reconstruction was also performed. Conventional GJ was performed along the posterior gastric curvature hand-sewn or with stapler device, via an antecolic or retrocolic route. Deciding which procedure should be performed was not controlled and defined by the surgeon responsible for each case.

Figure 1.

GP and GJ for malignant gastric cancer. A: Mechanical GP along the gastric curvatures; B: GJ performed at the proximal part of the stomach chamber (Image credits: Marcos Retzer/ Department of Gastroenterology, Universidade de São Paulo). GJ: Gastrojejunostomy; GP: Gastric partitioning.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included frequencies by percent for nominal variables and means with standard deviation for continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used for categorical data to evaluate the differences between variables, and the t-test was used for continuous data. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in survival were examined using the log-rank test. The survival period was calculated from the date of surgery until the date of death. Living patients were censored at the date of last personal contact. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

A total of 60 GC patients underwent gastric bypass due to irresectable distal GC. GP was performed in 30 patients and conventional GJ in the other 30 patients. Initial nutritional variables including hemoglobin, albumin, weight and BMI did not differ between groups (Table 1). KPS and ECOG were worse in GP patients. The presence of distant and peritoneal metastasis was also similar between groups. The complete impossibility of oral ingestion or ingestion of only liquids (GOOS 0-1) were present in 60% of patients in both groups.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of all patients

| Variables | GP, n = 30 | GJ, n = 30 | P value |

| Gender | 0.405 | ||

| Female | 8 (26.7) | 11 (36.7) | |

| Male | 22 (73.3) | 19 (63.3) | |

| Age in yr | 0.343 | ||

| mean (SD) | 67.5 (13.4) | 64.3 (12.7) | |

| Hemoglobin in g/dL | 0.782 | ||

| mean (SD) | 9.7 (2.1) | 9.9 (1.8) | |

| Albumin in g/dL | 0.087 | ||

| mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.3 (0.6) | |

| Karnofsky performance status | 0.001 | ||

| 60-70 | 20 (66.7) | 7 (23.3) | |

| 80-90 | 10 (33.3) | 23 (76.7) | |

| ECOG | 0.020 | ||

| 0-1 | 11 (36.7) | 20 (66.7) | |

| 2-3 | 19 (67.9) | 10 (33.3) | |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 0.055 | ||

| P0 | 17 (60.7) | 9 (34.6) | |

| P1 | 11 (39.3) | 17 (65.4) | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.192 | ||

| M0 | 16 (57.1) | 12 (40) | |

| M1 | 12 (42.9) | 18 (60) | |

| Weight in Kg | 0.598 | ||

| mean (SD) | 56.5 (12.1) | 54.9 (11.3) | |

| BMI in Kg/m² | 0.362 | ||

| mean (SD) | 21.8 (5.1) | 20.7 (3.9) | |

| Initial GOOS | 1.0 | ||

| 0-1 | 18 (60) | 18 (60) | |

| 2-3 | 12 (40) | 12 (40) | |

Total population n = 60. Data presented as n (%). BMI: Body mass index; ECOG: Eastern cooperative oncology group; GJ: Gastrojejunostomy; GOOS: Gastric outlet obstruction score; GP: Gastric partitioning.

Operative outcomes are demonstrated in Table 2. The mean operative time was higher in the partitioning group (161.2 vs 85.2 min, P < 0.001). Roux-en-Y reconstruction was performed in 16 patients (57.1%) in the GP group and in none of the GJ group. Manual anastomosis was more common in the partitioning group (42.9% vs 6.7%, P = 0.001). There were no differences regarding postoperative complications and surgical mortality between groups. The mean time in days for ingestion of liquids (GOOS 1), soft diet (GOOS 2), and length of hospital stay was similar between groups. GOOS 2 and 3 were reached by 28 GP patients (93.3%) and 22 GJ patients (75.9%) (P = 0.080).

Table 2.

Surgical outcomes

| Variables | Partitioning, n = 30 | GJ, n = 30 | P value |

| Operative time in min | < 0.001 | ||

| mean (SD) | 161.2 (76.4) | 85.2 (37.7) | |

| Roux-en-Y reconstruction | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 12 (42.9) | 30 (100) | |

| Yes | 16 (57.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Anastomosis | 0.001 | ||

| Manual | 12 (42.9) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Stapler | 16 (57.1) | 28 (93.3) | |

| Postoperative complication | 0.254 | ||

| No/minor | 28 (93.3) | 24 (80) | |

| Major | 2 (6.7) | 6 (20) | |

| Surgical mortality | 1.0 | ||

| No | 28 (93.3) | 27 (90) | |

| Yes | 2 (96.7) | 3 (10) | |

| Days for GOOS ≥ 1 | 0.375 | ||

| mean (SD) | 3.3 (3.2) | 2.6 (1.9) | |

| Days for GOOS ≥ 2 | 0.371 | ||

| mean (SD) | 4.7 (3.7) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Length of hospital stay in d | 0.201 | ||

| mean (SD) | 8.6 (5.2) | 11.1 (9.2) | |

| Final GOOS | 0.080 | ||

| 0-1 | 2 (6.7) | 7 (24.1) | |

| 2-3 | 28 (93.3) | 22 (75.9) | |

Data presented as n (%). SD: Standard deviation; GJ: Gastrojejunostomy; GOOS: Gastric outlet obstruction score.

The evolutionary control of weight gain after the procedure evidenced that, after 30 and 90 d, there was no difference between groups (Table 3). Maximum mean weight recorded after surgery was similar between GP and GJ groups (56.6 vs 56.8 Kg, P = 0.966). A second additional procedure was necessary in four patients in each group to establish nutritional enteral access, which included an enteral feeding tube.

Table 3.

Control of weight after the procedure

| Variables | Partitioning, n = 30 | GJ, n = 30 | P value |

| Weight-30 d1 | 0.391 | ||

| mean (SD) | 57.7 (13.4) | 54.9 (11.3) | |

| Weight 90 d1 | 0.132 | ||

| mean (SD) | 59.9 (12,7) | 54.6 (10.2) | |

| Weight-maximum | 0.966 | ||

| mean (SD) | 56.6 (11.8) | 56.8 (10.0) | |

| Weight-final1 | 0.343 | ||

| mean (SD) | 51.9 (12.5) | 53.9 (12.7) | |

| Weight variation initial-30 d | 0.343 | ||

| mean (SD) | 1,92 | - 1.2 | |

| Weight variation initial - 90 d | 0.287 | ||

| mean (SD) | - 0.28 | - 0.21 | |

| Weight variation 30 - 90 d | 0.140 | ||

| mean (SD) | - 1.52 | 0.5 | |

| Weight variation initial - Final | 0.383 | ||

| mean (SD) | - 4.9 | - 2.4 | |

| Second procedure | 1.0 | ||

| No | 26 (86.7) | 26 (86.7) | |

| Yes | 4 (13.3) | 4 (13.3) | |

Data not available in some cases. Data presented as n (%). GJ: Gastrojejunostomy;

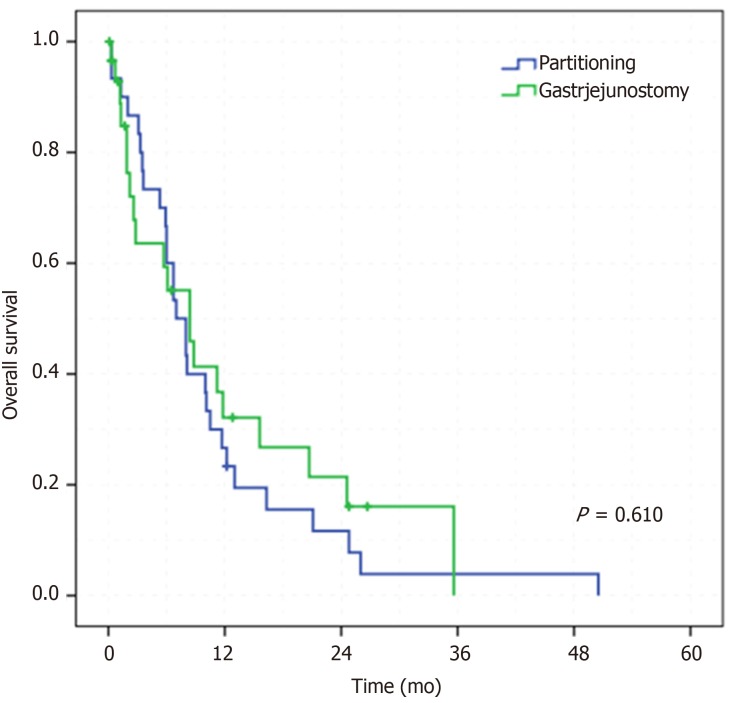

The mean follow-up was 9.2 mo (median of 6.6 mo, standard deviation [SD] ± 9.7) Forty-nine (81.6%) patients died during that period. The median OS of the entire sample was 8 mo (range 0.1–50.5). Regarding the type of surgery, there was no difference in survival between the groups. The median OS was 7 and 8.4 mo for the GP and GJ groups, respectively (P = 0.610) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall survival for GP and GJ (P = 0.610). GJ: Gastrojejunostomy; GP: Gastric partitioning.

The multivariate analysis of clinicopathological characteristics and operative outcomes associated with OS demonstrated that only GOOS 2-3 after surgery were statistically significant in improving survival (hazard ratio [HR]: 8.90; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.38-23.43, P < 0.001) (Table 4). The type of surgery (GJ vs GP) was not associated with improvement in OS (HR: 1.16, 95%CI: 0.65-2.07, P = 0.612).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for survival - Cox regression

| Variables1 |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

P value | |||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | ||

| Age 0-64 vs > 65 yr | 1.05 | 0.59-1.87 | 0.866 | - | - | - |

| Female vs Male | 0.77 | 0.42-1.40 | 0.391 | - | - | - |

| BMI ≥ 24.4 vs < 24.4 | 1.07 | 0.60-1.91 | 0.819 | - | - | - |

| Initial GOOS 2-3 vs 0-1 | 1.31 | 0.73-2.34 | 0.363 | - | - | - |

| Final GOOS 2-3 vs 0-1 | 9.42 | 3.67-24.20 | < 0.001 | 8.90 | 3.38 - 23.43 | < 0.001 |

| GJ vs Partitioning | 1.16 | 0.65-207 | 0.612 | - | - | - |

| Major POC vs Minor/non POC | 1.51 | 1.07-5.90 | 0.035 | 1.68 | 0.65 - 4.36 | 0.287 |

The first variable represents the reference category. HR: Hazard ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; BMI: Body mass index; GOOS: Gastric outlet obstruction score; POC: Postoperative complication.

DISCUSSION

GP proved to be as effective as GJ for the treatment of GOO. Both procedures had similar results regarding postoperative complications and no difference in survival was found. Nevertheless, there was a trend for GP in promoting better acceptance of soft solids, low residue, and full diets (GOOS 2-3) by the patients (P = 0.08). These results reinforce GP as a valid option to be added to GJ in the treatment of GOO.

Recently, endoscopic stents have gained popularity to treat such a condition[13]. It is less invasive and can be performed outside the operating room. The return of oral intake is faster with a shorter length of hospital stay. As a disadvantage, the method presents an acute risk of bleeding, perforation, and stent migration. In the long-term, tumor growth may lead to stent obstruction with the necessity of reinterventions[14]. According to the multicenter randomized trial SUSTENT, endoscopic stents are mostly indicated for patients with poor status performance, high surgical risk, and life expectancy less than 2 mo[8]. Patients with better clinical conditions and with the possibility of receiving palliative chemotherapy have a potential benefit of definitive surgical gastric derivation[15].

The first report of GP was made by Devine et al[10] in 1925, in a patient with obstruction caused by a complex duodenal ulcer. Maingot et al[16] in 1936 first reported its use in gastric cancer. In both cases, partitioning of the stomach was complete. This fact led to closed loop syndrome of the distal gastric stump with the risk of a blowout as a consequence of inadequate drainage of the gastric fluids from the excluded stomach. Yet, bleeding from the tumor may occur.

After those initial reports, there were no further publications regarding that method. Nevertheless, its employment gained prominence after Kaminishi’s report in 1997. In that original series, 31 unresectable GC patients with GOO underwent either GP or GJ. The rates of acceptance of a regular meal at 2 wk after the operation were 88% in the partitioning group and 31% in the GJ group (P < 0.05). Still, the mean survival times for GP and GJ were 13.4 and 5.8 mo, respectively (P < 0.05)[17]. The authors presented a modification in the technique, maintaining a small communication between the two gastric chambers created after the partitioning. This communication avoids closed loop syndrome and the risk of a blowout. It also allows the endoscopic access to the tumor and the biliary tree in case of the necessity of biliary drainage. Still, gastric acid entry into the antrum is also maintained, decreasing the stimulation of gastrin and consequent risk of ulcer formation[18]. Regarding GE, the proximal gastric chamber created by partitioning has smaller dimensions in relation to the entire stomach, which is also dilated in many cases. The reduction in organ dimensions decreases the formation of recesses distal to the anastomosis and in the proximal body and gastric fundus. Thus, it may decrease the recirculation of the ingested food inside the stomach, facilitating its flow to the anastomosis and decreasing the GE time.

Advantages attributed to partitioning include improving GE and reducing tumor bleeding due to less contact of ingested food. Still, it reduces the necessity of blood transfusion. Besides that, improving food intake and reducing bleeding help patients to better tolerate the effects of palliative chemotherapy, which may improve survival[19-21]. Another interesting aspect of such a procedure is the fact that the tumor is isolated in the distal gastric chamber. Subsequently, the possibility of obstruction of the GJ by tumor growth is minimized. In addition, this technique has also been applied for tumors of the biliopancreatoduodenal confluence[9,18].

As a disadvantage, the addition of a stapling line creates new potential sites for postoperative fistula. The operative time may also increase, as shown in the present study. However, the persistent attempt to accomplish tumor resection and the greater proportion of cases with Roux-en-Y reconstruction may have influenced this result. Thus, we believe that after the technique becomes routine, this increment in operative time due to the addition of the partitioning is minimal. There is no consensus regarding the need for Roux-en-Y reconstruction. The presence of biliary flow to the stomach due to the GJ is something that theoretically can impair GE. Moreover, reflux alkaline gastritis and afferent loop syndrome may impair acceptance of diet. The use of a Roux-en-Y reconstruction or the addition of Braun enteroenterostomy may prevent these complications[22]. However, as patients have limited life expectancy, the alleged short and long-term complications of biliary reflux were not observed in our study. Thus, Roux-en-Y reconstruction may not be justified.

Both procedures can be safely performed by laparoscopy[23-25]. They may also be performed during a staging laparoscopy with palliative intent or even to improve nutritional status in a patient with neoadjuvant or conversion therapy indication[26].

When comparing the techniques, the outcomes analyzed vary in literature. Regarding early postoperative results, DGE is widely used but the way of classifying is not standardized and is somewhat subjective. The International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definition has been employed[27]. It conceptually defines DGE when a nasogastric tube is required for 8 d or limited oral intake cannot be tolerated by postoperative day 14. This criterion may be too strict, causing lack of documentation of cases with mild DGE. Ernberg et al[9] reported a significantly lower incidence of DGE in GP patients (0%) compared with the GJ (42.9%, P = 0.024). Additionally, oral nutrition alone was recorded more often at follow-up in the partitioning group (9/9, 100%) than in the GJ group (4/13, 30.8%) (P = 0.002). Thus, in the present study, we decided to evaluate the time to reach GOOS scores 2 and 3. Both groups took the same average of days for diet acceptance and progression. However, the partitioning group had a trend to present higher final values of GOOS. The length of hospital stay is another early outcome commonly used. It indirectly reflects the ability of oral ingestion acceptance. In addition, it is influenced by other factors of interest such as postoperative complications.

Kumagai et al[28] published a meta-analysis comparing GP with GJ. Seven studies containing 207 patients were included. GP had a significantly lower risk of DGE (relative risk: 0.32; 95%CI 0.17 to 0.60; P < 0.001) and shorter postoperative hospital stay (mean of 6.1 d; P < 0.001). Conversely, no significant differences were observed in operative time, blood loss, postoperative complications and anastomotic leak[28].

The main long-term goals of GP are the maintenance of oral intake capacity and survival. What can be verified is that once the GOO is successfully solved, either with GP or GJ, patients maintain the capacity to eat until near death. Only 13.3% of patients did require additional procedures to maintain the alimentary route. When that happened, it was doubtful whether the failure was exclusively due to the initial procedure causing GOO recurrence or due to disease progression. The weight regain was also similar between the two groups, confirming the equal long-term effectiveness of both procedures to maintain oral intake.

Improved OS has been reported with GP[19-21]. The fact that the tumor is excluded in the distal gastric chamber leads to a lower occurrence of tumoral bleeding. Less bleeding associated with improvement in oral intake allows better use of palliative chemotherapy with a beneficial effect on OS. However, we did not verify this result in our study (P = 0.08). It could be speculated that, with more patients in the analysis, perhaps some differences among the two techniques would appear. Yet, the GP group had lower values of KPS and ECOG. The selection bias of patients with worse performance and consequently worse OS may have influenced this result. Lastly, multivariate analysis showed that the main prognostic factor in patients with GOO was the ability to eat better after the procedure regardless of the technique used (HR: 8.90, 95%CI: 3.38-23.43, P < 0.001).

Retrospective studies have limitations inherent to their design. The selection of patients for both techniques was not done in an equivalent manner. In the past 10 years, GP has been the procedure of choice for GOO cases in our institution. The decision to perform conventional GJ still takes place as an option, especially in urgent cases or when the surgeon is not familiar with the partitioning technique. This situation allowed us to create a control group. Fortunately, exactly 30 patients were included in the control group in the same period. In order to increase group sampling, it was thoughtful to include patients from previous periods when partitioning was not performed. However, this would bring the disadvantage of not including recent advances in palliative treatment in GC, which would have an impact on survival. Surprisingly, clinicopathological characteristics of patients in both groups were almost similar, with the exception of KPS and ECOG scores, not making the comparison so unequal.

To overcome these limitations, a prospective randomized study comparing GP with GJ was initiated at our institution. Thus, currently, no patient is submitted to any procedure for the treatment of GOO outside the prospective protocol. The study is ongoing recruiting patients and is expected to be completed within the next year (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02064803).

In summary, GP proved to be a safe and effective procedure for the treatment of GOO. Compared to conventional GJ, GP has similar early and late outcomes with a trend to better solid diet acceptance by the patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is a common complication during gastric cancer treatment. Different treatment modalities have been employed including endoscopic stent placement, surgical resection, and surgical bypass procedures. Surgical bypass may have better results when life expectancy is larger than 2 mo. It may be performed with a simple gastrojejunostomy (GJ) or with the addition of partial gastric partitioning (GP).

Research motivation

GJ has been traditionally performed as bypass procedure for GOO. However, delayed gastric emptying with impaired food ingestion may occur in up to 26% of cases. To overcome this setback, GP has been employed. The partitioning creates two separated gastric chambers that may improve gastric emptying, decrease tumor bleeding, and improve survival.

Research objectives

We compared the surgical results of GJ and GP for the treatment of GOO in patients with unresectable distal gastric cancer.

Research methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of 60 patients submitted to GJ and GP between 2009 and 2018. Clinicopathological characteristics and surgical outcomes were compared.

Research results

GP was performed in 30 patients and conventional GJ in the other 30 patients. Baseline clinicopathological characteristics were similar between groups, with the exception of worse performance status in GP patients. Surgical results related to postoperative complications and surgical mortality did not differ between groups. The median OS was 7 and 8.4 mo for GP and GJ groups, respectively (P = 0.610). The oral acceptance of soft solids (GOOS 2) and low residue or full diet (GOOS 3) were reached by 28 (93.3%) GP patients and 22 (75.9%) GJ patients (P = 0.080). After multivariate analysis, acceptance of soft solids and low residue or full diet was the main prognostic factors for survival despite the surgical procedure performed (HR: 8.90, 95%CI: 3.38-23.43, P < 0.001).

Research conclusions

GP is a safe and effective procedure to treat GOO. Compared to GJ, it provides similar early and late outcomes with a trend to better solid diet acceptance by the patients.

Research perspectives

After this initial experience using GP, a prospective trial was initiated and currently no patient has been submitted to any procedure for the treatment of GOO outside the protocol. The study is ongoing, recruiting patients, and is expected to be completed within the next year (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02064803).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank other members of the service involved in gastric cancer treatment: Andre R Dias, Claudio JC Bresciani, Marcelo Mester, Osmar K Yagi, Amir Z Charruf, and Fabio P Lopasso.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study is part of the database project approved by the hospital ethics committee (NP771/15) and registered online (www.plataformabrasil.com; CAAE:43453515.6.0000.0065).

Informed consent statement: Due to the retrospective, non-interventional, and data analysis-based design of the study, informed consent was waived.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 26, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Article in press: October 3, 2019

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chiu CC, Lin JM, Jeong KY S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Marcus Fernando Kodama Pertille Ramos, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil. marcus.kodama@hc.fm.usp.br.

Leandro Cardoso Barchi, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Rodrigo Jose de Oliveira, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Marina Alessandra Pereira, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Donato Roberto Mucerino, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Ulysses Ribeiro Jr, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Bruno Zilberstein, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Ivan Cecconello, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo 01249000, Brazil.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4) Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos MFKP, Pereira MA, Yagi OK, Dias AR, Charruf AZ, Oliveira RJ, Zaidan EP, Zilberstein B, Ribeiro-Júnior U, Cecconello I. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: a 10-year experience in a high-volume university hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2018;73:e543s. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2018/e543s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JP, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Yu HJ, Yang HK. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors in 10 783 patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s101200050006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dassen AE, Lemmens VE, van de Poll-Franse LV, Creemers GJ, Brenninkmeijer SJ, Lips DJ, Vd Wurff AA, Bosscha K, Coebergh JW. Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of gastric adenocarcinoma between 1990 and 2007: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartgrink HH, Putter H, Klein Kranenbarg E, Bonenkamp JJ, van de Velde CJ Dutch Gastric Cancer Group. Value of palliative resection in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1438–1443. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moura EG, Ferreira FC, Cheng S, Moura DT, Sakai P, Zilberstain B. Duodenal stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:938–943. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i9.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, van Eijck CH, Schwartz MP, Vleggaar FP, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD Dutch SUSTENT Study Group. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:490–499. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernberg A, Kumagai K, Analatos A, Rouvelas I, Swahn F, Lindblad M, Lundell L, Nilsson M, Tsai JA. The Added Value of Partial Stomach-partitioning to a Conventional Gastrojejunostomy in the Treatment of Gastric Outlet Obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1029–1035. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2781-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devine H. Basic Principles and Supreme Difficulties in Gastric Surgery. Surg Gynec and Obst. 1925;40:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minata MK, Bernardo WM, Rocha RS, Morita FH, Aquino JC, Cheng S, Zilberstein B, Sakai P, de Moura EG. Stents and surgical interventions in the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E1158–E1170. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-115935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, Vleggaar FP, van Eijck CH, van Hooft JE, Schwartz MP, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD Dutch SUSTENT Study Group. Predictors of survival in patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a patient-oriented decision approach for palliative treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Moreno MC, Martí-Obiol R, López F, Ortega J. Modified Devine Exclusion for Unresectable Distal Gastric Cancer in Symptomatic Patients. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;11:9–16. doi: 10.1159/000452759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maingot R. The surgical treatment of irremovable cancer of the pyloric segment of the stomach. Ann Surg. 1936;104:161–166. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193608000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminishi M, Yamaguchi H, Shimizu N, Nomura S, Yoshikawa A, Hashimoto M, Sakai S, Oohara T. Stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy for unresectable gastric carcinoma. Arch Surg. 1997;132:184–187. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430260082018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrangoiz R, Papavasiliou P, Singla S, Siripurapu V, Li T, Watson JC, Hoffman JP, Farma JM. Partial stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy and the success of this procedure in terms of palliation. Am J Surg. 2013;206:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon SJ, Lee HG. Gastric partitioning gastrojejunostomy in unresectable distal gastric cancer patients. World J Surg. 2004;28:365–368. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota K, Kuroda J, Origuchi N, Kaminishi M, Isayama H, Kawabe T, Omata M, Mafune K. Stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy for gastroduodenal outlet obstruction. Arch Surg. 2007;142:607–11; discussion 611. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.7.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oida T, Mimatsu K, Kawasaki A, Kano H, Kuboi Y, Amano S. Modified Devine exclusion with vertical stomach reconstruction for gastric outlet obstruction: a novel technique. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1226–1232. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0874-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Ishigami S, Yanagita S, Okubo K, Uchikado Y, Kita Y, Mori S, Kurahara H, Maemura K, Natsugoe S. Clinical Impact of Stomach-partitioning Gastrojejunostomy with Braun Enteroenterostomy for Patients with Gastric Outlet Obstruction Caused by Unresectable Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:5431–5436. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kushibiki T, Ebihara Y, Hontani K, Tanaka K, Nakanishi Y, Asano T, Noji T, Kurashima Y, Murakami S, Nakamura T, Tsuchikawa T, Okamura K, Shichinohe T, Hirano S. The Surgical Outcomes of Totally Laparoscopic Stomach-partitioning Gastrojejunostomy for Gastric Outlet Obstruction: A Retrospective, Cohort Study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2018;28:e49–e53. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barchi LC, Jacob CE, Bresciani CJ, Yagi OK, Mucerino DR, Lopasso FP, Mester M, Ribeiro-Júnior U, Dias AR, Ramos MF, Cecconello I, Zilberstein B. MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY FOR GASTRIC CANCER: TIME TO CHANGE THE PARADIGM. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2016;29:117–120. doi: 10.1590/0102-6720201600020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramagem CA, Linhares M, Lacerda CF, Bertulucci PA, Wonrath D, de Oliveira AT. Comparison of laparoscopic total gastrectomy and laparotomic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28:65–69. doi: 10.1590/S0102-67202015000100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka T, Suda K, Satoh S, Kawamura Y, Inaba K, Ishida Y, Uyama I. Effectiveness of laparoscopic stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy for patients with gastric outlet obstruction caused by advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2007;142:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumagai K, Rouvelas I, Ernberg A, Persson S, Analatos A, Mariosa D, Lindblad M, Nilsson M, Ye W, Lundell L, Tsai JA. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing partial stomach partitioning gastrojejunostomy versus conventional gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:777–785. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1470-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.