Abstract

Herein, we present a case of a 64-year-old male presenting with diplopia that was found to have a left orbital Masson’s tumor. It is necessary to differentiate it from malignant angiosarcoma as complete excision is often curative. The following case emphasizes the modalities that can be used for diagnosis as well as the appropriate treatments.

Keywords: masson's tumor, ipeh, intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia, ophthalmology, oculoplastics, oncology, oncological surgery

Introduction

Masson’s tumor, also known as intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH), is a rare benign neoplasm that affects the head, neck, and upper extremities. There are few (less than 20) periorbital cases that have been reported in ophthalmologic literature [1-4]. Masson’s tumor can often be difficult to distinguish between other entities including malignant angiosarcoma; its prompt diagnosis is important to begin optimal treatment as soon as possible.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old Caucasian male with past medical history of diabetes mellitus and past ocular history of bilateral cataract extraction with intraocular lens (CEIOL) presented to an outside vitreoretinal specialist one-month post-CEIOL due to diplopia and possible retinal detachment. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was measured as 20/25 OU, pupils were reactive without afferent pupillary defect (APD) OU, and intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured as 21 and 18 mmHg, respectively. Optical coherence tomography of both eyes revealed a flat and attached macula OU. Fundus photos revealed irregular appearance of nasal retina OS. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with nasal choroidal effusion and was given cyclopentolate, prednisolone, and oral dexamethasone.

The patient returned for follow-up one week later with no resolution of symptoms and new complaint of an inferior “knot” OS with pain and pressure. BCVA and pupillary examination were unchanged. IOP was measured as 16 and 18 mmHg, respectively. Dilated fundoscopic examination was performed, and treatment was discontinued as the choroidal effusion had resolved.

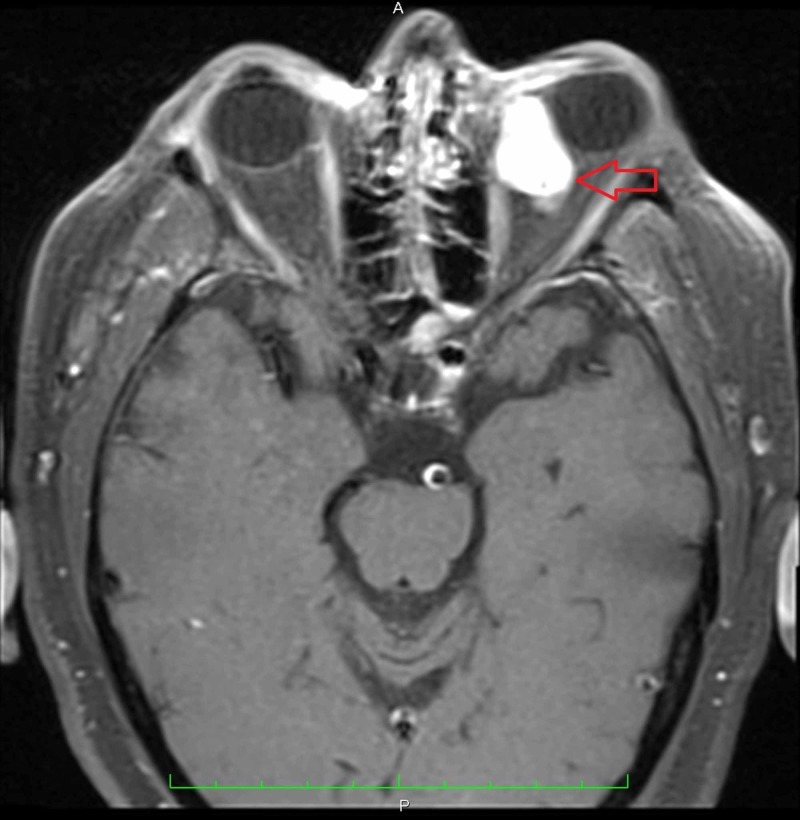

Further follow-up three weeks later revealed no change in subjective pain and pressure symptoms OS. The patient described his diplopia as horizontal and binocular. Further questioning revealed that his symptoms began two months ago after CEIOL. BCVA, pupillary examination, and IOP were unchanged. Dilated fundoscopic examination was notable for a return of his choroidal effusion. MRI of the orbits with and without contrast ordered which revealed an enhancing 2.5 x 1.6 x 3.2 cm left orbital lesion involving both the intraconal and extraconal compartments and contributing to the left-sided proptosis (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1. Transverse MRI of the orbits without contrast revealed a mass in the left orbit contributing to proptosis.

Figure 3. Coronal MRI of the orbits with contrast gives another view of the enhancing lesion within the left orbit.

Figure 2. Transverse MRI of the orbits with contrast revealed an enhancing lesion in the left orbit involving both the intraconal and extraconal compartments measuring 2.5 x 1.6 x 3.2 cm.

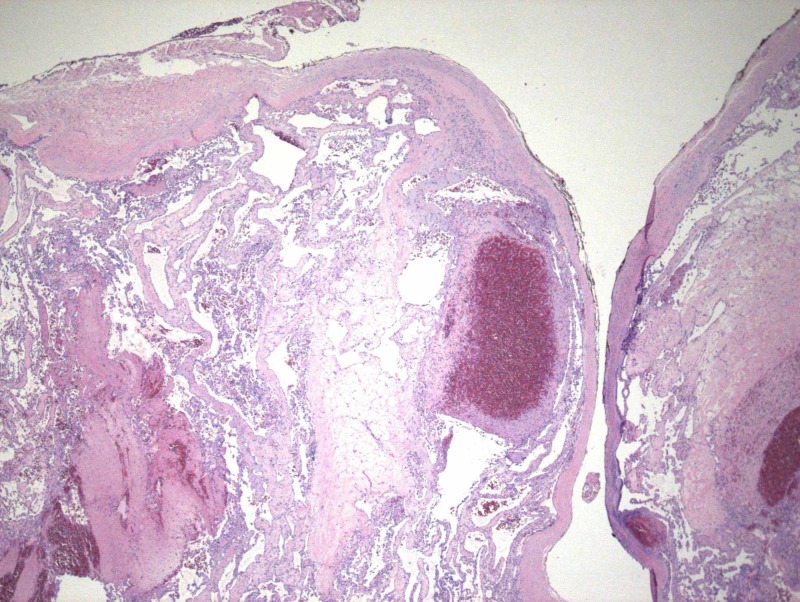

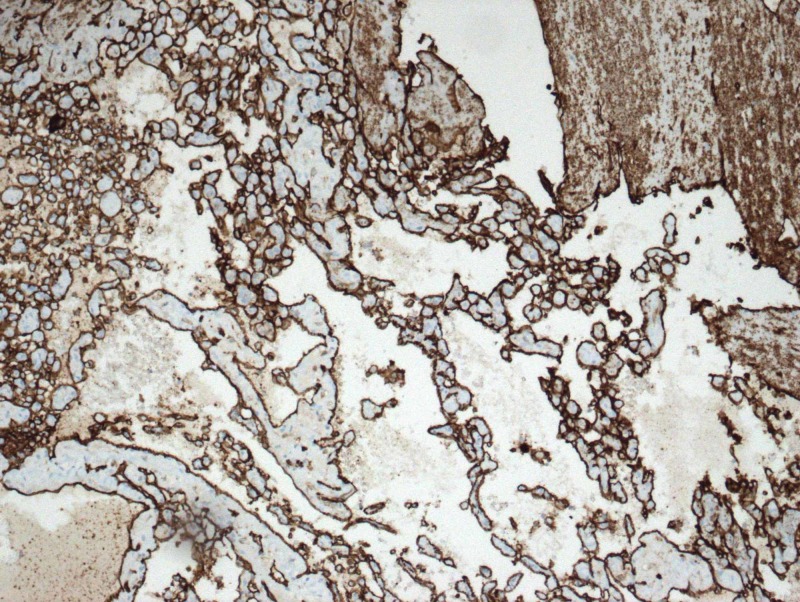

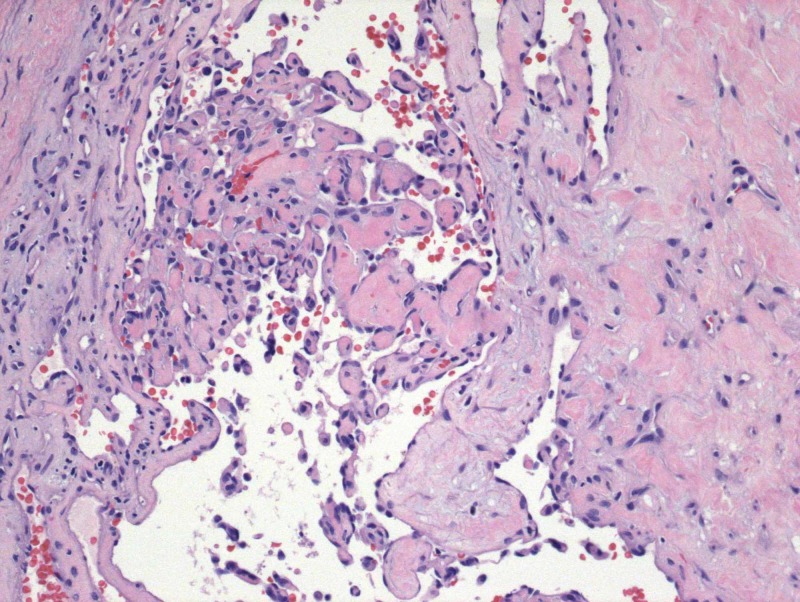

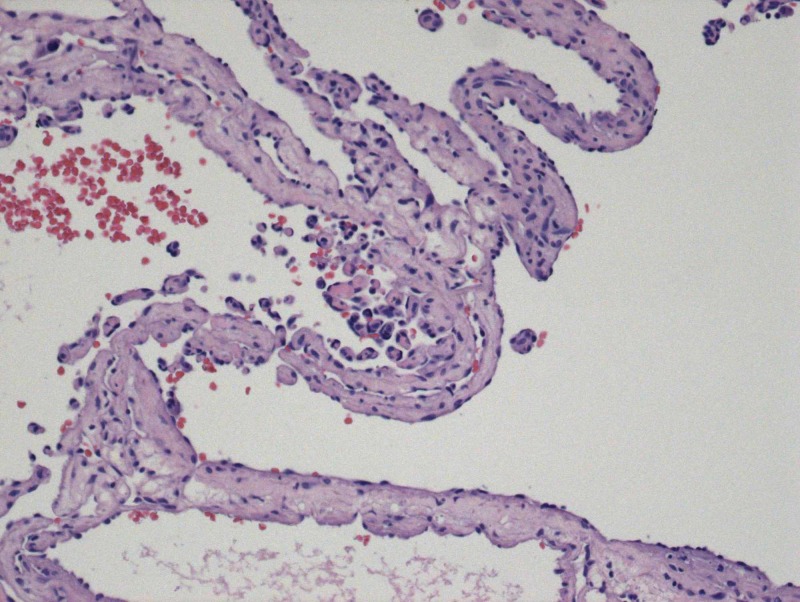

At this time, the patient was referred to oculoplastics for further evaluation. Nineteen days after the MRI, the patient reported continued diplopia, pain, and proptosis OS. His ocular examination was as follows: BCVA of 20/25 OU, pupils reactive with no APD OU, IOP of 21 and 27 mmHg, respectively. His extraocular movements were full OD and -1 in all gazes OS. His MRI was reviewed, and the patient was scheduled for a biopsy of the orbital mass. An approximately 2.1 x 0.5 cm mass submitted for routine sectioning revealed papillary formations and arborizing channels contained within a fibromuscular wall compatible with a dilated vascular space. Variably sized vascular channels intersect the interior of the mass, and these channels contain erythrocytes and serum. Papillae are characterized by a hyalinized fibrovascular core lined by plump mononuclear cells that occasionally form syncytia. CD31 immunohistochemical marker for endothelial cells richly outlines the furcating vascular network (Figures 4-7).

Figure 4. The absence of tissue necrosis, noninfiltrative intraluminal location of the lesion, and the association between proliferating tuft structures with thrombotic material differentiate IPEH from angiosarcoma.

Figure 7. CD31 immunohistochemical marker.

Figure 5. Papillary formations and arborizing channels.

Figure 6. Vascular channels containing erythrocytes and serum.

The final diagnosis was IPEH, also known as Masson’s tumor.

The patient subsequently underwent orbitotomy with excision with removal of approximately 80% of the tumor. The other 20% was inaccessible as it was circumferential to the optic nerve. The patient had improvement of pain, diplopia, and proptosis post-surgery, and a follow-up CT was scheduled three months later.

Discussion

IPEH was first described by Masson in 1923 as “vegetate intravascular hemangioendothelioma”[5]. It is characterized by a reactive hyperplastic proliferation of the vascular endothelium [1]. It has been speculated that the primary process is endothelial proliferation followed by thrombus formation; however, others conjecture that endothelial papillary proliferation is a response to thrombus formation [1-3]. There is no age, race, or sex predilection for the generalized IPEH; however, in their case series, Wagh et al found that the average age for periorbital IPEH was 41.2 years with a male to female ratio of 2:1 [1,2].

IPEH has a predisposition for the head, neck, and upper extremities, and it may present in both the orbit and eyelid. It often presents as a firm, cystic, freely mobile, reddish/purple swelling that may increase in size [3,4]. The differential diagnosis of IPEH includes vascular lesions such as angiosarcoma, angiolymphatic hyperplasia with eosinophilia (Kimura disease), and other primary or secondary tumors [1,2,6]. The histopathologic absence of tissue necrosis, noninfiltrative intraluminal location of the lesion, and the association between proliferating tuft structures with thrombotic material help to differentiate IPEH from angiosarcoma [1,7]. It needs to be differentiated from malignant angiosarcoma as complete excision is often curative [8].

There are three forms of IPEH. Primary IPEH forms within a dilated vascular space with a preference for extremities. Secondary or reactive IPEH is the most common and is predominately found in the musculature. It originates within pre-existing vascular malformations such as varix, lymphangioma, or cavernous hemangioma. Tertiary IPEH is the rarest, forms within hematomas, and is extravascular.

Evidence of unilateral proptosis in an elderly patient should prompt imaging to rule out mass effect. MRI is the preferred imaging technique for identifying IPEH. Lesions appear isointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging with homogenous enhancement following contrast administration [1]. Management depends on the clinical features and progression of the lesion. Surgical excision is the preferred method of treatment; however, the lesion may recur with incomplete excision. There may be a role for adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for recurrent or concerning lesions [1-3].

Conclusions

Recognizing IPEH and differentiating from malignant lesions such as angiosarcoma is important to prevent morbidity related to unnecessary chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. This case emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and a strong referral base for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Even in cases where surgical correction is not entirely curative, a significant improvement of symptoms can be obtained post-surgery. This patient received appropriate care and surgical correction to remove 80% of the tumor, and he subsequently had significant quality-of-life improvements.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Periorbital masson’s tumor: a case series. Wagh VB, Kyprianou I, Burns J, Brown LJR, Vaidhyanath R, Sampath R. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;27:55–57. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181e978f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia: collection of four cases and a review of the literature. Werner MS, Hornblass A, Harrison W, Reifler DM, Dresner SC. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;13:48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compressive effects of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Aggarwal E, Madge SN, Selva D, Rodgers N. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:122–124. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b8e0e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyelid varix with phlebolith formation, thrombus recanalization, and early intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Zakka FR, Jakobiec FA, Thakker MM. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:8–11. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181d8e13c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemangioendotheliome vegetant intravasculare. Masson MP. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&volume=93&publication_year=1923&pages=517-523&journal=Bull+Soc+Anat+%28Paris%29&author=Masson%2C+P.&title=H%C3%A9mangioendoth%C3%A9liome+v%C3%A9g%C3%A9tant+intravasculaire Bull Soc Anat. 1923;93:517. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia with presumed orbital varices. Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC Jr, Diniz W. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/412312. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1247–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Clearkin KP, Enzinger FM. https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/947306. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;100:441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Intravascular angiomatosis: development and distinction from angiosarcoma. Salyer WR, Salyer DC. Cancer. 1975;36:995–1001. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197509)36:3<995::aid-cncr2820360323>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]