Abstract

A growing number of effective cancer therapies is associated with cardiovascular (CV) toxicities including myocardial injury or dysfunction, leading to reduced ventricular function, and increased risk of heart failure. As the timing of administration of cancer treatment is known, the potential for risk stratification pre-treatment, and appropriate surveillance and monitoring during treatment, and intervention with cardio-protective treatment strategies in patients exhibiting early evidence of CV toxicity is an appealing clinical strategy. The field of cardio-oncology has developed, and the application of monitoring strategies using CV biomarkers and CV imaging has been to focus of many studies and is now implemented in dedicated cardio-oncology services supporting oncology centres. In this article, we review the background and rationale for monitoring, the different options and their strengths, weaknesses and where they are helpful in specific cardiotoxic cancer therapies, and the impact in cardio-oncology care.

Keywords: Heart failure, Cancer, Cardio-oncology, Monitoring

Introduction

In recent years, cancer treatment is becoming more effective with the advent of novel agents targeting new pathways, receptors and activating the immune system to target the cancer cells. These advances have improved the rates of successful treatment and survival from cancer. However, the rate of complications related to these therapies has also increased.1 Cardiovascular (CV) complications are a common and important side effect which not only has the potential to affect the quality of life and longevity in cancer survivors but also leads to interruption of effective anticancer treatments leading to worse cancer outcomes.2 Cardiovascular diseases are frequently the leading cause of non-cancer-related mortality. For example, survivors of cancers diagnosed in childhood,3–6 patients with breast cancer7 and many other cancers, the risk of developing CV complications persists for years after treatment with anthracycline chemotherapy (AC) or radiotherapy to the chest.8 During cancer therapy, patients who have pre-existing CV disease and even CV risk factors, display a higher risk of cardiotoxicity from AC and other cardiotoxic-targeted cancer therapies [e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (VEGFi), BCr-ABl inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors (PIs), Raf-MEK inhibitors, and Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor agonists]. Cancer treatment pathways are scheduled which allows a unique opportunity for a baseline pre-treatment risk assessment and monitoring of CV toxicity allowing pre-emptive treatment.9 This approach requires an understanding of the short- and long-term CV complications encountered with each specific oncology treatment, paired with appropriate cardiology knowledge, allowing for pathway design, diagnosis, and management of cardiac complications resulting as a consequences of cancer treatment on the CV system, or as a result of the direct involvement of the cancer in the heart, in the new subspecialty of cardio-oncology.10 Establishing and developing such a specialized field requires close collaboration between cardio-oncologists, oncologists, and haemato-oncologists. This multidisciplinary approach has been shown to yield better prognostic outcomes in patients suffering from numerous different types of cancer.11,12 The purpose of this subspecialty is to prevent the development and minimize the progression of CV complications by guiding treatment therapies and interventions tailored to the patient.

Cancer drug therapies can affect many structures in the heart, including myocardium [causing inflammatory or non-inflammatory left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure (HF)], conduction system (heart block), electrophysiology (tachy- or bradyarrhythmias and QT-prolongation), pericardium, coronary arteries (raising issues like myocardial infarction, vasospasm, or accelerated atherosclerosis), valves (especially after high-dose radiotherapy to the valve tissue), the pulmonary circulation causing pulmonary hypertension, and the systemic arterial and venous circulation leading to arterial hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and venous thromboembolism. Chest-directed radiotherapy can increase coronary artery disease or cause fibrotic changes predominantly to the valves; pericardium or myocardium and, therefore, monitoring in survivors who have received high-dose radiation to the heart should consider these multiple CV diseases. Cancer patients should also have serial assessment of modifiable CV risk factors (cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, and body mass index) and the risks addressed according to the CV prevention guidelines for high-risk patients.13

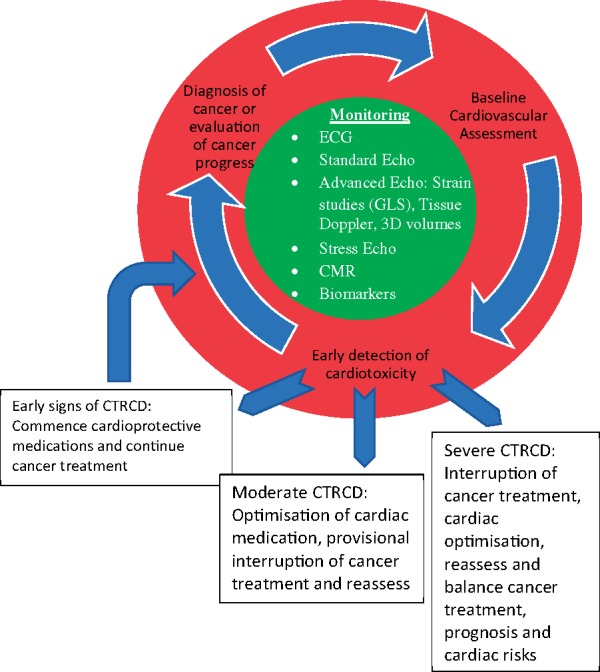

Monitoring for CV disease during and after cancer therapy will be discussed in two sections (See Figure 1). In the first part, the general considerations are provided for all cancer patients. In the second section, cancer treatments with specific CV side effect profiles, requiring targeted CV screening, and follow-up with individualized surveillance programme are discussed. The complexity of this field for each cancer therapy with a CV toxicity profile and how pathways of care for low-, moderate-, and high-risk patients is beyond the scope of this article, and we refer the reader to the forthcoming series of position statements from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology which will present Baseline risk stratification proformas, detailed biomarker and imaging surveillance pathways and treatment strategies for a range of effective cancer therapies with potential cardiotoxicity.

Figure 1.

Summary of monitoring the heart receiving cancer treatment.

Baseline cardiovascular risk assessment and cardio-oncology follow-up

A baseline risk assessment is advised for patients scheduled to receive a cancer therapy with potential CV toxicity. This should be provided by the oncology and haemato-oncology services in co-ordination with their local cardiology or cardio-oncology service.

Assessment of baseline CV risk before cancer therapies which are potentially cardiotoxic is advisable. Baseline risk is based on several patient-related factors, treatment-related factors, and cancer-related factors. Young children or individuals older than 65 years, pre-existing conventional CV risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and smoker), and antecedent heart disease (like left ventricular dysfunction or coronary artery disease) increases the risk of CV complications. Additionally, type of treatment used, cumulative dose (AC and trastuzumab), combination therapy (such as AC and HER2 receptors or dual immunotherapy agents use), or intensive or accelerated regimens put the patient at higher risk of cardiac complications. The type and location of the cancer are important. For instance, mediastinal tumours requiring radiotherapy increases the cardiac side effects if the heart is in the radiation field.14

Pathways should ensure high-risk patients are referred and reviewed promptly by the cardiology or cardio-oncology service and guidance on monitoring during the planned cancer therapy is provided with a schedule personalized to the patient, their CV risk factors and pre-existing CV disease, the proposed cancer treatment and the context (metastatic vs. curative intent, prognosis with and without cancer treatment, alternative non-cardiotoxic cancer therapies). Cardiac symptom review before and during cancer treatment are important in addition to monitoring cardiac function and injury directly via biomarkers and imaging.12

Imaging assessment

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is a first-line cardiac imaging technique with advantages including its availability, assessment of multiple elements of cardiac function beyond left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), relatively cheap cost, and it is radiation-free allowing multiple scans safely. Echocardiographic assessment of cardiotoxicity allows detection during and in the 12 months after treatment, and in high-risk patients may be used for intermittent surveillance for life. Most focus has been on monitoring LVEF is important in monitoring the cancer patients during or after the treatment, and a pre-treatment echocardiography in the high-risk patients provide a baseline for further comparison.12

Cancer therapeutics-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) has a range of definitions, from oncology trials to cardiology studies and registries, which has added confusion to the field. The joint EACVI-ACC imaging position statement proposed one definition, the LVEF is reduced by more than 10% from the baseline or it decreased to the value <53%, and this should be confirmed in two consecutive echocardiography assessments with 2–3 weeks apart.15 However, there are several limitations of this type of definition. Left ventricular (LV) volumes and LVEF are ideally measured by Simpson’s biplane method. However, LVEF is both load- and heart rate-dependent in many patients. Intravascular volume in the cancer patients is quite variable, as they sometimes receive large amount of intravenous fluids at the time of chemotherapy, or are dehydrated due to vomiting or diarrhoea. Sympathetic tone varies and may be elevated due to stress, anxiety, and/or pain. These changes all affect LVEF and introduce variability and potential error. Cancer patients may have suboptimal acoustic windows form prior chest surgery or radiotherapy. Contrast-enhanced echocardiography is useful in more accurate assessment of LVEF; however, the LV volume whilst using contrast may be overestimated and contrast obscure other detailed measurements. Three-dimensional ejection fraction may help to improve accuracy of measurements but cannot always be acquired due to image quality. When three-dimensional echocardiography is performed, it is critical to recognize that the normal references for the cardiac chambers and LVEF is different from two-dimensional measurements. Three-dimensional imaging is highly based on the two-dimensional image quality and it is not helpful in the patients with difficult acoustic windows.

Another technically challenging issue is that LVEF assessment cannot identify early cardiotoxicity in treatments like anthracyclines16 and when depressed LVEF is diagnosed, significant myocardial injury has already occurred is more likely to be irreversible.17

Tissue Doppler assessment and diastolic function, including septal and lateral E’, S’, and mitral annulus plane systolic excursion M-mode (MAPSE) as well as mitral inflow E waves measurements have all been studied in different trials and can add incremental value in monitoring the heart in cancer patients, and at times it has helped to identify the cardiotoxicity in earlier stages. Although there is no definite cut-off point to determine normality for these measurements in cancer patients, serial assessment may identify early cardiotoxicity. The transmitral E/A ratio may be an independent predictor of cardiotoxicity in some studies although this has not been reproduced in other studies.18

Speckle tracking, especially to measure left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) may be helpful in detecting subclinical LV dysfunction, and the values should be compared against the baseline and more studies are in process to elucidate the details. Impairment in GLS <8% probably does not have clinical consequences. However, worsening of >15% has been proposed as a clinically significant, but in the opinion of the authors, this is only relevant if it also falls into the abnormal GLS range. In addition, it is critical that serial monitoring is performed with echocardiography machines from the same vendor so the scale remains the same.15 Emerging data suggest that GLS reduction may be relevant in specific cancer populations including those receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and paediatric cancer survivors during long-term follow-up.19,20 In some cancer populations, a reduction in GLS appears to predict future fall in LVEF, but as a more sensitive imaging technique it must be applied cautiously (e.g. effective oncology treatments must not be stopped based on a reduction of LV GLS alone). More studies are required to prove impairment in GLS can change outcomes and this will be addressed in one cancer population in the SUCCOUR trial.

Monitoring valvular disease in cancer survivors who have been exposed to high doses of cardiac radiation may be appropriate. Prospective studies are absent, partly due to the long latency between treatment exposure and clinically significant valve disease. Five yearly echocardiographic surveillance from 5 years post-treatment may be considered, with more frequent assessment if abnormalities of valvular function are detected. During and after treatment, if infective endocarditis is suspected, transoesophageal echocardiography may be appropriate. Mitral regurgitation may be primary due to radiation-related damage, or secondary to LV dysfunction. A similar principle is also relevant for tricuspid regurgitation as primary or secondary to right ventricular (RV) dilatation. Radiotherapy in younger patients causes direct valvular injury with fibrotic changes in intracardiac valves causing stenosis or regurgitation and monitoring valvular disease is important in these patients. In older patients with pre-existing valve disease, lower radiation doses may accelerate the underlying disease. When valvular dysfunction is diagnosed, more frequent monitoring with serial echocardiography is recommended.

Pericardial diseases are also more common in cancer patients after radiation therapy to the heart, and echocardiography provides opportunity to assess pericardial effusion or consequences like tamponade or constrictive physiology with preload challenge if equivocal results at rest are detected.

Stress echocardiography may be applied for several indications. First is in the assessment for flow-limiting coronary disease in patients at moderate or high risk before major cancer surgery or cancer treatments which may potentially cause myocardial ischaemia, including fluorpyrimidines (5-fluorouracil and capecitabine) or VEGFi.21 Serial assessment of contractile reserve has been studied but is not validated for routine clinical practice although it may be helpful in early detection of subclinical cardiac dysfunction. Stress echocardiography is not only valuable in CV prognosis but provocatively it may also helpful in estimation of non-cardiac cancer death.22

Endomyocardial biopsy

In the past considered as the most specific modality for diagnosis of cancer therapeutics-related cardiotoxicity. However, owing to its invasive nature and inherent risks, it is considered generally as a last line of investigation, especially with the advent of other modalities for monitoring the heart like advanced echocardiography and biomarkers. However, it is becoming increasingly important for the diagnosis or exclusion of ICI-related myocarditis in borderline cases with discordant biomarker and imaging findings to guide future ICI treatment.

Cardiac magnetic resonance

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) provides detailed assessment of LV and RV function and is the best imaging modality to evaluate presence or absence of fibrosis, infarction, myocarditis, and amyloidosis, as well as pericardial anatomy and inflammation, and assessment of intracardiac masses. However, CMR has several important limitations, including cost, accessibility, acquisition time, contraindications in the patients with implanted metal works, quality in patients with fast heart rates, AF or frequent ectopy, and difficulties in the patients suffering from claustrophobia or advanced anxiety.

MUGA

Multiple-gated acquisition scan (MUGA) was initially the standard modality for early assessment of serial LVEF and detection of subclinical left ventricular dysfunction prior to the clinical HF. It has the advantage of being reproducible and useful in the patients with difficult acoustic windows which makes the transthoracic echocardiography difficult and is widely available with costs comparable with other modalities. However, MUGA has drawbacks, particularly, the cumulative dose of radiation, and inability to provide information about other cardiac elements like LV diastolic function, right ventricle, PA pressure, valvular function, or left atrium dimensions.23

Cardiac biomarkers

Cardiac biomarkers are readily and widely available with high precision, accuracy, and clear cut-off points for a range of cardiac diseases, e.g. acute coronary syndromes. Cardiac biomarkers including cardiac troponin (cTn) and natriuretic peptides [brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal portion of proBNP (NT-proBNP)] have been studied for early detection of cardiac dysfunction.24 Cardiac troponin’s are markers of cardiac injury, and in many studies showing the patients receiving AC with elevated troponin levels are at higher risk of cardiac events and developing cardiotoxicity, and the magnitude and duration of this elevation are important in cardiac prognosis after completing AC.25 The value of cTn in newer cancer drugs like trastuzumab in treatment of breast cancer has also been explored, although many of these patients have also received AC.26 Brain natriuretic peptide is more sensitive than cTn during trastuzumab, VEGFi, and PI at detecting early LV dysfunction and predicting function clinical cardiac adverse events. Emerging data suggest BNP or NT-proBNP may also be helpful in detecting ICI-medicated cardiotoxicity. In an unselected population of all CV toxicity from ICI, only 46% of the patients had positive troponin levels but all (100%) had elevated BNP. However, this may reflect different clinical practice regarding biomarker measurement and more detailed studies are required. In high-risk patients scheduled to receive potentially cardiotoxic cancer treatments known to cause HF regular monitoring of cardiac biomarkers including cTn and natriuretic peptides (NPs) should be considered for early detection of cardiac dysfunction.

Anthracycline chemotherapy

Anthracycline chemotherapy, including doxorubicin, epirubicin, daunorubicin, idarubicin, and anthracenediones (mitoxantrone and pixantrone) cause cumulative dose-dependent cardiotoxicity and dysfunction, AC’s cause cardiomyocyte damage via increased reactive oxygen species and topoisomerase-IIβ inhibition.27 At the cellular level, it causes vacuolar deformation before myofibrillar dysfunction and cellular apoptosis.28 If left late this leads to irreversible damage and hence early measurement of cTn is helpful to detect early myocardial injury before irreversible left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) and HF develops.29,30

HER2-targeted therapy

Trastuzumab, pertuzumab, T-DM1, lapatinib, and neratinib are the HER2-targeted therapies with inhibit the HER2 receptor and improve prognosis in HER2+ early invasive and/or metastatic HER+ breast cancer. Heart disease initiated cardiac HER2 expression in a mechanism for cardioprotection and stabilization, and hence HER2 inhibitors cause LV and/or RV dysfunction. In most cases, HER2-targeted therapy-mediated cardiac dysfunction is reversible by interruption of the therapy and administration of cardioprotective medications. However, interruption of HER2 targeted therapies may lead to worse cancer outcomes, particularly in metastatic HER2+ breast cancer and so preventing interruptions through monitoring is an appealing strategy. Regular monitoring with echocardiography for early detection is recommended and recent studies suggest two new approaches. The first is to use baseline cTn pre-treatment and serial surveillance of both GLS and NPs during treatment as a sensitive strategy. The second is to continue trastuzumab in patients where the LVEF falls to 40–49% providing the patient is clinically stable and with implementation of appropriate cardioprotective medication.31

Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors

Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (VEGFi) have a relatively higher rate of CV side effects, particularly, the more non-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. Sunitinib and Sorafenib). The most common complications include arterial hypertension, ischaemic events, arrhythmias due to QT-prolongation, and cardiac dysfunction, which may be multifactorial, including both hypertensive HF and direct cardiotoxicity, particularly, in patients with pre-existing LV dysfunction or hypertrophy. Therefore, a baseline risk assessment in all cancer patients scheduled to receive a VEGFi is recommended, with regular cardiac monitoring in moderate and high-risk patients using echocardiography and NPs. Regular blood pressure monitoring with home blood pressure diaries, and electrocardiograms (ECG’s) in clinic to measure QTc intervals, are recommended.

BCr-ABl TKI’s

BCr-Abl TKIs are predominantly used in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia with Imatinib being the characteristic agent in this group, which has minimal cardiac side effects. However, second-generation therapies such as Dasatinib and Nilotinib, and the third-generation BCr-Abl TKI Ponatinib have significant CV toxicities.

Nilotinib accelerates the atherosclerotic process and causes accentuation in baseline CV risk factors, to the extent that peripheral arterial disease leading to limb amputation has been reported. It also causes QTc-interval prolongation. Monitoring requires regular assessment of standard CV risk factors, including cholesterol, HbA1c, blood pressure, and ECGs to measure QTc. Dasatinib may cause pulmonary hypertension and/or HF and serial echocardiography to address both LV function and PA pressure is recommended in moderate- and high-risk cases (baseline PA elevation and baseline LV dysfunction). Dasatinib cause pleural effusion in up to 28% of cases with an unknown mechanism but it does not appear to be cardiac. Bosutinib has lower rates of CV complications, all of which in the studies could be managed medically without the need for discontinuation of Bosutinib. Ponatinib, which also being used in the trials for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, has a relatively high risk of CV toxicity. This includes an increased risk of occlusive arterial and venous occlusive events. Ponatinib also causes HF in a dose-dependent effect and myocardial infarction. Cardiac and CV risk factor monitoring should be performed to address these potential side effects and optimize CV risk factor control.32

RAF/MEK TKI’s

RAF and MEK inhibitors are pro-survival pathways in various cancers including melanoma and thyroid cancers. In combination, they have improved survival in Raf-mutant melanoma and other Raf-mutant cancers. Recent data have clarified that HF or LVSD is caused by combination Raf- and MEK inhibitors in 5–10% of patients.33 Regular monitoring for early detection of cardiac dysfunction with serial echocardiography, biomarkers, and ECG’s may be considered in the patients receiving these agents but more research is required.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors ICIs are increasingly used to treat a variety of neoplasms with important benefits. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-mediated cardiotoxicity occurring most commonly in the first few cycles, with inflammatory CV toxicities including myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis. LV dysfunction including cardiogenic shock, and malignant ventricular arrhythmias may occur in patients with myocarditis with high mortality rates of 25–50%.34–36 The optimal monitoring strategy has not been identified, but ECG and biomarker (cTn and NP) monitoring in the first few cycles may be helpful. Cardiac complications are more prevalent in combination immunotherapy settings, for example, the combination of Nivolumab and Ipilimumab, or an ICI plus a VEGFi. The effects of ICI’s are variable in different individuals. They have the potential to cause heart block, tachyarrhythmias, cardiac dysfunction, pericarditis, acute coronary syndrome, or vasculitis. Monitoring may consist of regular ECG’s, cardiac biomarkers, and echocardiography. In case of LV dysfunction, CMR is very important in diagnosing the underlying aetiology and distinguishing the inflammatory from non-inflammatory dysfunction, which has different treatment options and implications in cancer therapy.

Ibrutinib

Ibrutinib is a first-generation Bruton Tyrosine Kinase inhibitor used in B-cell cancers, demonstrating cardiotoxicity including a high risk of new atrial fibrillation and a small increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.37 Monitoring for new AF with serial ECGs, or other technologies for cardiac rhythm monitoring, may be considered.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular monitoring of selected cancer patients receiving cardiotoxic cancer treatments, who are at higher risk, is a logical clinical strategy for the early detection of cardiac dysfunction if this leads to implementation of cardioprotective strategies to allow effective cancer therapies to continue safely. More trials are required to identify the optimal monitoring strategy for each cancer treatment, including which modalities (imaging, biomarkers, and combination) and frequency, with the goal of improving both cancer and CV outcomes. Expert consensus and position papers from the HFA will address these challenges and provide clinical pathways in the near future based on the experience and limited evidence available.

Conflict of interest: Dr A.R.L. received speaker, advisory board or consultancy fees and/or research grants from Pfizer, Novartis, Servier, Amgen, Takeda, Roche, Janssens-Cilag Ltd, Clinigen Group, Eli Lily, Eisai, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim. M.H. has no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JWW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F.. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1374–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Munoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, Habib G, Lenihan DJ, Lip GYH, Lyon AR, Lopez-Fernandez T, Mohty D, Piepoli MF, Tamargo J, Torbicki A, Suter TM; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: the Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:9–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Stiller CA, Jenney ME, Skinner R, Stevens MC, Hawkins MM; British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Steering Group. Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 2010;304:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Marina N, Hobbie W, Kadan-Lottick NS, Schwartz CL, Leisenring W, Robison LL.. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, Wasilewski K, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Yasui Y.. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1368–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LCM, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJH, Heinen RC, Jaspers MWM, Koning CCE, Oldenburger F, Langeveld NE, Hart AAM, Bakker PJM, Caron HN, van Leeuwen FE.. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 2007;297:2705–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patnaik JL, Byers T, DiGuiseppi C, Dabelea D, Denberg TD.. Cardiovascular disease competes with breast cancer as the leading cause of death for older females diagnosed with breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res 2011;13:64.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fidler MM, Reulen RC, Henson K, Kelly J, Cutter D, Levitt GA, Frobisher C, Winter DL, Hawkins MM.. Population-based long-term cardiac-specific mortality among 34 489 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain. Circulation 2017;135:951–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, Kawashima T, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, Stovall M, Chow EJ, Sklar CA, Mulrooney DA, Mertens AC, Border W, Durand J-B, Robison LL, Meacham LR.. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3673–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong RA, Iimura T, Sumida KN, Eager RM.. Cardio-oncology/onco-cardiology. Clin Cardiol 2010;33:733–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lancellotti P, Suter TM, Lopez-Fernandez T, Galderisi M, Lyon AR, Van der Meer P, Cohen Solal A, Zamorano JL, Jerusalem G, Moonen M, Aboyans V, Bax JJ, Asteggiano R.. Cardio-oncology services: rationale, organization, and implementation: a report from the ESC Cardio-Oncology council. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1756–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pareek N, Cevallos J, Moliner P, Shah M, Tan LL, Chambers V, Baksi AJ, Khattar RS, Sharma R, Rosen SD, Lyon AR.. Activity and outcomes of a cardio-oncology service in the United Kingdom-a five-year experience. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1721–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FDR, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WMM, Binno S; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suter TM, Ewer MS.. Cancer drugs and the heart: importance and management. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1102–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, Ewer MS, Ky B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Ganame J, Sebag IA, Agler DA, Badano LP, Banchs J, Cardinale D, Carver J, Cerqueira M, DeCara JM, Edvardsen T, Flamm SD, Force T, Griffin BP, Jerusalem G, Liu JE, Magalhães A, Marwick T, Sanchez LY, Sicari R, Villarraga HR, Lancellotti P.. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014;27:911–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ewer MS, Ali MK, Mackay B, Wallace S, Valdivieso M, Legha SS, Benjamin RS, Haynie TP.. A comparison of cardiac biopsy grades and ejection fraction estimations in patients receiving Adriamycin. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jensen BV, Skovsgaard T, Nielsen SL.. Functional monitoring of anthracycline cardiotoxicity: a prospective, blinded, long-term observational study of outcome in 120 patients. Ann Oncol 2002;13:699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bountioukos M, Doorduijn JK, Roelandt JR, Vourvouri EC, Bax JJ, Schinkel AF, Kertai MD, Sonneveld P, Poldermans D.. Repetitive dobutamine stress echocardiography for the prediction of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Eur J Echocardiogr 2003;4:300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Armstrong GT, Joshi VM, Ness KK, Marwick TH, Zhang N, Srivastava D, Griffin BP, Grimm RA, Thomas J, Phelan D, Collier P, Krull KR, Mulrooney DA, Green DM, Hudson MM, Robison LL, Plana JC.. Comprehensive echocardiographic detection of treatment-related cardiac dysfunction in adult survivors of childhood cancer: results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2511–2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Portugal G, Moura Branco L, Galrinho A, Mota Carmo M, Timoteo AT, Feliciano J, Abreu J, Duarte Oliveira S, Batarda L, Cruz Ferreira R.. Global and regional patterns of longitudinal strain in screening for chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Rev Port Cardiol 2017;36:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeh ET, Bickford CL.. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:2231–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carpeggiani C, Landi P, Michelassi C, Andreassi MG, Sicari R, Picano E.. Stress echocardiography positivity predicts cancer death. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e007104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gottdiener JS, Mathisen DJ, Borer JS, Bonow RO, Myers CE, Barr LH, Schwartz DE, Bacharach SL, Green MV, Rosenberg SA.. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: assessment of late left ventricular dysfunction by radionuclide cineangiography. Ann Intern Med 1981;94:430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cardinale D, Sandri MT.. Role of biomarkers in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2010;53:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Colombo A, Colombo N, Boeri M, Lamantia G, Civelli M, Peccatori F, Martinelli G, Fiorentini C, Cipolla CM.. Prognostic value of troponin I in cardiac risk stratification of cancer patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy. Circulation 2004;109:2749–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cardinale D, Colombo A, Torrisi R, Sandri MT, Civelli M, Salvatici M, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Cortinovis S, Dessanai MA, Nolè F, Veglia F, Cipolla CM.. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: clinical and prognostic implications of troponin I evaluation. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3910–3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, Lu L-S, Lyu YL, Liu LF, Yeh ETH.. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med 2012;18:1639–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Friedman MA, Bozdech MJ, Billingham ME, Rider AK.. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Serial endomyocardial biopsies and systolic time intervals. JAMA 1978;240:1603–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Felker GM, Thompson RE, Hare JM, Hruban RH, Clemetson DE, Howard DL, Baughman KL, Kasper EK.. Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1077–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ewer MS, Lippman SM.. Type II chemotherapy-related cardiac dysfunction: time to recognize a new entity. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2900–2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lynce F, Barac A, Geng X, Dang C, Yu AF, Smith KL, Gallagher C, Pohlmann PR, Nunes R, Herbolsheimer P, Warren R, Srichai MB, Hofmeyer M, Cunningham A, Timothee P, Asch FM, Shajahan-Haq A, Tan MT, Isaacs C, Swain SM.. Prospective evaluation of the cardiac safety of HER2-targeted therapies in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and compromised heart function: the SAFE-HEaRt study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;175:595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aghel N, Delgado DH, Lipton JH. Cardiovascular toxicities of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia: preventive strategies and cardiovascular surveillance. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2017;13:293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mincu RI, Mahabadi AA, Michel L, Mrotzek SM, Schadendorf D, Rassaf T, Totzeck M.. Cardiovascular adverse events associated with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e198890.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias S, Gorham J, Xu Y, Hicks M, Puzanov I, Alexander MR, Bloomer TL, Becker JR, Slosky DA, Phillips EJ, Pilkinton MA, Craig-Owens L, Kola N, Plautz G, Reshef DS, Deutsch JS, Deering RP, Olenchock BA, Lichtman AH, Roden DM, Seidman CE, Koralnik IJ, Seidman JG, Hoffman RD, Taube JM, Diaz LA, Anders RA, Sosman JA, Moslehi JJ.. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1749–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moslehi JJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA.. Myocarditis with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2017;376:292.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lyon AR, Yousaf N, Battisti NML, Moslehi J, Larkin J.. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and cardiovascular toxicity. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e447–e458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, Zhao W, Booth AM, Ding W, Bartlett NL, Brander DM, Barr PM, Rogers KA, Parikh SA, Coutre S, Hurria A, Brown JR, Lozanski G, Blachly JS, Ozer HG, Major-Elechi B, Fruth B, Nattam S, Larson RA, Erba H, Litzow M, Owen C, Kuzma C, Abramson JS, Little RF, Smith SE, Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Byrd JC.. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2517–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]